Americans coped with pandemic using problem solving, emotional support

Alessandro Biascioli / iStock

A survey of 1,000 Americans assessing positive and negative coping skills during the pandemic shows that people fared better when focused on problem solving and planning during times of uncertainty.

As part of the study, published yesterday in PLOS One , participants engaged in an online survey to assess how they dealt with stressful life events (SLEs), coping strategies, and the physical and psychological health domains of quality of life (QOL) during COVID-19. The 25- to 30-minute survey was conducted in August 2021 on Prolific, a web-based survey recruitment platform.

Survey respondents were mostly White (73%), equally divided among men and women, with a mean age of 44. Half were married or cohabitating.

More stressors led to more avoidance behaviors

Using 16 questions, the authors identified three patterns for coping with SLEs: problem-focused coping, emotional-focused coping, and avoidant coping.

Problem-focused coping included four items relating to the use of informational support. Emotion-focused coping included six items using emotional support, humor, and religion. And avoidant coping had six items relating to self-distraction, substance use, and behavioral disengagement.

Respondents answered the coping questions using a 5-point Likert scale, noting how they had coped with particular stressors over the last year.

The mean number of SLEs reported by respondents was 1.6, with a range of 0 to 18. The three most common SLEs reported in the sample were a decrease in financial status, followed by personal injury or illness, and a change in living conditions.

Problem- and emotional-focused coping helped

For all respondents, problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping were significantly related to higher levels of QOL, whereas avoidant coping was associated with lower QOL, the authors said. More life stressors correlated to using more avoidant coping skills.

As the pandemic instigated or exacerbated a wide range of unexpected and unpredictable stressors, such as personal illness, illness and deaths of loved ones, and unemployment, we posit that the use of emotion-focused coping was likely helpful in navigating these situations.

"Previous research, most of which was conducted pre-pandemic, has demonstrated inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between emotion-focused coping and QOL, with many studies pointing to a negative association between these two constructs," the authors said. They hypothesize that emotional coping served people well during the pandemic because it helped them handle uncertainty.

"As the pandemic instigated or exacerbated a wide range of unexpected and unpredictable stressors, such as personal illness, illness and deaths of loved ones, and unemployment, we posit that the use of emotion-focused coping was likely helpful in navigating these situations," the authors said.

Related news

Three studies spotlight long-term burden of covid in us adults.

Bernie Sanders calls for $1 billion for long-COVID moonshot

Study identifies inflammation and symptom patterns in long COVID

Blood donor study finds 21% incidence of long-term symptoms attributed to COVID-19

Rural COVID-19 patients have higher death rates following hospital stays, data reveal

No need to avoid exercise with long-COVID diagnosis, researchers say

US drugs with noted supply-chain risks 5 times more likely to go into shortage in early COVID

Among fully vaccinated, study shows Paxlovid does not shorten symptoms

This week's top reads

Tests confirm avian flu on new mexico dairy farm; probe finds cats positive.

The virus was also confirmed on five more Texas farms, as investigators find more clues from animal samples and genetic sequences.

CDC sequencing of H5N1 avian flu samples from patient yields new clinical clues

The nasopharyngeal swab didn't suggest upper respiratory involvement, and virus sequencing of the eye sample showed one change that isn't linked to transmission.

The antiviral drug likely has a gradient of benefit, with those at highest risk most likely to see the greatest benefit, experts say in an editorial.

Officials warn of H5N1 avian flu reassortant circulating in parts of Asia

The virus is a reassortant between the older H5N1 clade (2.3.2.1c), still circulating in parts of Asia, and a newer H5N1 clade (2.3.4.4b) that began circulating globally in 2021.

Avian flu infects person exposed to sick cows in Texas

The patient's only symptom is conjunctivitis, which has been seen before in avian flu infections.

Wastewater testing near homeless camps shows COVID-19 viral mutations

Analysis of viral sequences uncovered 3 novel viral spike protein mutations.

Vietnam reports its first human infection from H9 avian flu virus

The patient lived adjacent to a poultry market, but there were no reports of bird illnesses or deaths.

Study links air quality improvements to fewer school COVID cases

The study took place at a school that serves vulnerable students in a setting where air quality improvements were made and then monitored.

Participants with long COVID had a 21% lower peak volume of oxygen consumption at baseline.

Among blood donors with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, 23.6% reported long-term neurologic symptoms.

Our underwriters

Unrestricted financial support provided by.

- Antimicrobial Resistance

- Chronic Wasting Disease

- All Topics A-Z

- Resilient Drug Supply

- Influenza Vaccines Roadmap

- CIDRAP Leadership Forum

- Roadmap Development

- Coronavirus Vaccines Roadmap

- Antimicrobial Stewardship

- Osterholm Update

- Newsletters

- About CIDRAP

- CIDRAP in the News

- Our Director

- Osterholm in the Press

- Shop Merchandise

- COVID-19 and your mental health

Worries and anxiety about COVID-19 can be overwhelming. Learn ways to cope as COVID-19 spreads.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, life for many people changed very quickly. Worry and concern were natural partners of all that change — getting used to new routines, loneliness and financial pressure, among other issues. Information overload, rumor and misinformation didn't help.

Worldwide surveys done in 2020 and 2021 found higher than typical levels of stress, insomnia, anxiety and depression. By 2022, levels had lowered but were still higher than before 2020.

Though feelings of distress about COVID-19 may come and go, they are still an issue for many people. You aren't alone if you feel distress due to COVID-19. And you're not alone if you've coped with the stress in less than healthy ways, such as substance use.

But healthier self-care choices can help you cope with COVID-19 or any other challenge you may face.

And knowing when to get help can be the most essential self-care action of all.

Recognize what's typical and what's not

Stress and worry are common during a crisis. But something like the COVID-19 pandemic can push people beyond their ability to cope.

In surveys, the most common symptoms reported were trouble sleeping and feeling anxiety or nervous. The number of people noting those symptoms went up and down in surveys given over time. Depression and loneliness were less common than nervousness or sleep problems, but more consistent across surveys given over time. Among adults, use of drugs, alcohol and other intoxicating substances has increased over time as well.

The first step is to notice how often you feel helpless, sad, angry, irritable, hopeless, anxious or afraid. Some people may feel numb.

Keep track of how often you have trouble focusing on daily tasks or doing routine chores. Are there things that you used to enjoy doing that you stopped doing because of how you feel? Note any big changes in appetite, any substance use, body aches and pains, and problems with sleep.

These feelings may come and go over time. But if these feelings don't go away or make it hard to do your daily tasks, it's time to ask for help.

Get help when you need it

If you're feeling suicidal or thinking of hurting yourself, seek help.

- Contact your healthcare professional or a mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline. In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, contact your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Some may be able to see you in person or talk over the phone or online.

You also can reach out to a friend or loved one. Someone in your faith community also could help.

And you may be able to get counseling or a mental health appointment through an employer's employee assistance program.

Another option is information and treatment options from groups such as:

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Self-care tips

Some people may use unhealthy ways to cope with anxiety around COVID-19. These unhealthy choices may include things such as misuse of medicines or legal drugs and use of illegal drugs. Unhealthy coping choices also can be things such as sleeping too much or too little, or overeating. It also can include avoiding other people and focusing on only one soothing thing, such as work, television or gaming.

Unhealthy coping methods can worsen mental and physical health. And that is particularly true if you're trying to manage or recover from COVID-19.

Self-care actions can help you restore a healthy balance in your life. They can lessen everyday stress or significant anxiety linked to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-care actions give your body and mind a chance to heal from the problems long-term stress can cause.

Take care of your body

Healthy self-care tips start with the basics. Give your body what it needs and avoid what it doesn't need. Some tips are:

- Get the right amount of sleep for you. A regular sleep schedule, when you go to bed and get up at similar times each day, can help avoid sleep problems.

- Move your body. Regular physical activity and exercise can help reduce anxiety and improve mood. Any activity you can do regularly is a good choice. That may be a scheduled workout, a walk or even dancing to your favorite music.

- Choose healthy food and drinks. Foods that are high in nutrients, such as protein, vitamins and minerals are healthy choices. Avoid food or drink with added sugar, fat or salt.

- Avoid tobacco, alcohol and drugs. If you smoke tobacco or if you vape, you're already at higher risk of lung disease. Because COVID-19 affects the lungs, your risk increases even more. Using alcohol to manage how you feel can make matters worse and reduce your coping skills. Avoid taking illegal drugs or misusing prescriptions to manage your feelings.

Take care of your mind

Healthy coping actions for your brain start with deciding how much news and social media is right for you. Staying informed, especially during a pandemic, helps you make the best choices but do it carefully.

Set aside a specific amount of time to find information in the news or on social media, stay limited to that time, and choose reliable sources. For example, give yourself up to 20 or 30 minutes a day of news and social media. That amount keeps people informed but not overwhelmed.

For COVID-19, consider reliable health sources. Examples are the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Other healthy self-care tips are:

- Relax and recharge. Many people benefit from relaxation exercises such as mindfulness, deep breathing, meditation and yoga. Find an activity that helps you relax and try to do it every day at least for a short time. Fitting time in for hobbies or activities you enjoy can help manage feelings of stress too.

- Stick to your health routine. If you see a healthcare professional for mental health services, keep up with your appointments. And stay up to date with all your wellness tests and screenings.

- Stay in touch and connect with others. Family, friends and your community are part of a healthy mental outlook. Together, you form a healthy support network for concerns or challenges. Social interactions, over time, are linked to a healthier and longer life.

Avoid stigma and discrimination

Stigma can make people feel isolated and even abandoned. They may feel sad, hurt and angry when people in their community avoid them for fear of getting COVID-19. People who have experienced stigma related to COVID-19 include people of Asian descent, health care workers and people with COVID-19.

Treating people differently because of their medical condition, called medical discrimination, isn't new to the COVID-19 pandemic. Stigma has long been a problem for people with various conditions such as Hansen's disease (leprosy), HIV, diabetes and many mental illnesses.

People who experience stigma may be left out or shunned, treated differently, or denied job and school options. They also may be targets of verbal, emotional and physical abuse.

Communication can help end stigma or discrimination. You can address stigma when you:

- Get to know people as more than just an illness. Using respectful language can go a long way toward making people comfortable talking about a health issue.

- Get the facts about COVID-19 or other medical issues from reputable sources such as the CDC and WHO.

- Speak up if you hear or see myths about an illness or people with an illness.

COVID-19 and health

The virus that causes COVID-19 is still a concern for many people. By recognizing when to get help and taking time for your health, life challenges such as COVID-19 can be managed.

- Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Institutes of Health. https://covid19.nih.gov/covid-19-topics/mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic's impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Mental health and the pandemic: What U.S. surveys have found. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/02/mental-health-and-the-pandemic-what-u-s-surveys-have-found/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Taking care of your emotional health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://emergency.cdc.gov/coping/selfcare.asp. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- #HealthyAtHome—Mental health. World Health Organization. www.who.int/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---mental-health. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Coping with stress. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/stress-coping/cope-with-stress/. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- Manage stress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- COVID-19 and substance abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/covid-19-substance-use#health-outcomes. Accessed March 12, 2024.

- COVID-19 resource and information guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/NAMI-HelpLine/COVID-19-Information-and-Resources/COVID-19-Resource-and-Information-Guide. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Negative coping and PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/gethelp/negative_coping.asp. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Health effects of cigarette smoking. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm#respiratory. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- People with certain medical conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Your healthiest self: Emotional wellness toolkit. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/health-information/emotional-wellness-toolkit. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- World leprosy day: Bust the myths, learn the facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/world-leprosy-day/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- HIV stigma and discrimination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-stigma/. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Diabetes stigma: Learn about it, recognize it, reduce it. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/features/diabetes_stigma.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Phelan SM, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on stigma in integrated behavioral health: Barriers and recommendations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1370/afm.2924.

- Stigma reduction. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/case-studies/stigma-reduction.html. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Nyblade L, et al. Stigma in health facilities: Why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Medicine. 2019; doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1256-2.

- Combating bias and stigma related to COVID-19. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19-bias. Accessed March 15, 2024.

- Yashadhana A, et al. Pandemic-related racial discrimination and its health impact among non-Indigenous racially minoritized peoples in high-income contexts: A systematic review. Health Promotion International. 2021; doi:10.1093/heapro/daab144.

- Sawchuk CN (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. March 25, 2024.

Products and Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Future Care

- Antibiotics: Are you misusing them?

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Convalescent plasma therapy

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- COVID-19: How can I protect myself?

- Herd immunity and coronavirus

- COVID-19 and pets

- COVID-19 antibody testing

- COVID-19, cold, allergies and the flu

- COVID-19 drugs: Are there any that work?

- Long-term effects of COVID-19

- COVID-19 tests

- COVID-19 in babies and children

- Coronavirus infection by race

- COVID-19 travel advice

- COVID-19 vaccine: Should I reschedule my mammogram?

- COVID-19 vaccines for kids: What you need to know

- COVID-19 vaccines

- COVID-19 variant

- COVID-19 vs. flu: Similarities and differences

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Debunking coronavirus myths

- Different COVID-19 vaccines

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

- Fever: First aid

- Fever treatment: Quick guide to treating a fever

- Fight coronavirus (COVID-19) transmission at home

- Honey: An effective cough remedy?

- How do COVID-19 antibody tests differ from diagnostic tests?

- How to take your pulse

- How to measure your respiratory rate

- How to take your temperature

- How well do face masks protect against COVID-19?

- Is hydroxychloroquine a treatment for COVID-19?

- Loss of smell

- Mayo Clinic Minute: You're washing your hands all wrong

- Mayo Clinic Minute: How dirty are common surfaces?

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pregnancy and COVID-19

- Safe outdoor activities during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Safety tips for attending school during COVID-19

- Sex and COVID-19

- Shortness of breath

- Thermometers: Understand the options

- Treating COVID-19 at home

- Unusual symptoms of coronavirus

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Watery eyes

Related information

- Mental health: What's normal, what's not - Related information Mental health: What's normal, what's not

- Mental illness - Related information Mental illness

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Solving both the short- and long-term COVID-19 crises

Subscribe to global connection, mahmoud mohieldin and mahmoud mohieldin professor, department of economics - cairo university, egypt, executive director - international monetary fund, special envoy on financing the 2030 agenda for sustainable development - united nations michael kelleher michael kelleher director of external affairs - 2blades foundation, former advisor - world bank group, former special assistant to president barack obama - united states government.

April 14, 2020

The global COVID-19 health and economic crisis compels us to act in the short-term—in the here and now. We can’t look away from the human health consequences without giving our best efforts to lessen the suffering of those infected.

On the economic side, there is also great pain that must be assuaged. Some people are even using the “ D-Word ” to describe our unique predicament, with no widely agreed-upon solutions, and central bankers feeling the need to reassure markets that they are not running low on ammunition .

Multilateral organizations such as the World Bank and IMF have abruptly retooled and turned their focus completely toward this new global challenge, making sweeping changes in their agenda, engineering relief from debt service , and making substantial new investments in disaster response . The IMF estimates the total fiscal crisis relief is now at $8 trillion . The United Nations is also urging debt relief , while organizing a coordinated response and sending technical and material assistance to dozens of countries . The EU is stepping up with a large stimulus bill . Even a divided U.S. Congress agreed to spend $2 trillion for its crisis response.

However, poor nations, including those not yet experiencing high infection rates, will find it much more difficult to find the resources to climb out of this predicament. Low- and middle-income nations will benefit from multilateral assistance, but as infection rates rise, these nations may be disproportionately affected since 93 percent of the world’s informal employment is in emerging and developing countries . Helping these workers may require novel approaches, such as cash transfers , which have been used with success in other crisis situations, while some nations are offering tax relief to spur business activity, and others recommend wage subsidies and adjustments to credit guarantees and loan terms.

Of course, we have no choice but to act. Yet what happens when the crisis is over? There will likely be another Cassandra-like report which foreshadows the next crisis, begging our future selves to act in our own self-interest and to invest in solutions to problems that will confront us soon enough. Yet we rarely act to forestall or lessen the next crisis.

It’s not like we haven’t seen (a milder version of) this movie before: 15 years ago after SARS; and five years ago after the Ebola outbreak. Both times we diverted our attention just long enough to deal with the immediate needs, and then ignored the careful high-level post-mortem reports that laid out key decisionmaking and investments that would help us respond to future, perhaps much bigger challenges in the future like COVID-19.

Yet, buried in those not quite dusty post-mortem reports is a guidebook that shows us the way to serve both our short-term and long-term needs: to invest in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The 17 SDGs provide a pathway for us to “ build back better ” after the COVID-19 crisis, according to U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres. These global goals urge us to address challenges in poverty, health, inequality, and many other areas, while vowing to leave no one behind, with a deadline of 2030.

Many of the SDGs both address the current crisis as well as longer-term needs, including:

- Good health and well-being (SDG3). Right now the World Health Organization and other partners are supporting government COVID-19 responses , including testing, isolating, and caring for confirmed cases, while also tracing and quarantining people who have come in close contact with the infected. Over the long term, each country needs a health system that can deliver quality, essential health care and preventative services to everyone . They also need the capacity to perform future disease surveillance and diagnosis to rapidly identify, treat, and contain outbreaks, so that the human and economic costs are lessened.

- Water and sanitation (SDG6). To slow down the transmission of COVID-19 people need to wash or sanitize their hands . Yet today 3 billion people do not have access to even basic handwashing facilities at home , largely because they lack access to clean water, which increases their vulnerability to disease and ill health. Longer term, we must achieve universal access to safe and affordable drinking water and adequate sanitation for all in order to slow down the spread of infection and improve the health of all people.

- Ending hunger (SDG2). In many parts of the developing world, school closures mean the loss of children’s meals. In addition, global supply chains and trade have been disrupted , not just for food, but for agriculture inputs that support food production, exacerbated by the substantial number of workers idled due to COVID-19. Now is the time to act for long-term food security by making investments in technology that can improve agriculture productivity and the incomes of small-scale farmers.

- Decent work and economic growth (SDG8). According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the COVID-19 crisis is expected to wipe out 6.7 percent of working hours globally in the second quarter of 2020— equivalent to 195 million full-time workers . The ILO and others are urging that countries offer at least a basic level of social protection to as many people as possible, as soon as possible. Longer term, countries need to make investments to sustain per capita economic growth, productivity, and entrepreneurship, to support formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services.

- Quality education (SDG4). According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), COVID-19 has forced an estimated 1.5 billion learners to stay at home . UNESCO is supporting governments for distance learning, scientific cooperation, and information support. Longer-term support means that we need to make sure all children—especially girls—are in school and reaching literacy and numeracy targets, and are given greater access to secondary and tertiary education, as well as vocational training, while all should be served by well-trained teachers.

These are just a handful of examples of a comprehensive and applicable framework to enable us to achieve these goals while fighting poverty in an inclusive and sustainable way. Yet these COVID-related SDGs require adequate financing to respond to the crisis and also to make investments that can help us to become resilient to the ever-present threats.

This crisis has shown us the enormous economic and human costs of ignoring our own best advice to stave off the next crisis. This time, let’s do the right thing and deliver.

Related Content

Christopher J. Thomas

April 13, 2020

Homi Kharas

Addisu Lashitew

April 9, 2020

Related Books

Barry Eichgreen, et al., Richard Portes

October 1, 1995

Michael S. Barr

April 13, 2012

Ivo H. Daalder, Nicole Gnesotto, Philip H. Gordon

January 10, 2006

Emerging Markets & Developing Economies

Global Economy and Development

Homi Kharas, Charlotte Rivard

April 2, 2024

Surjit S. Bhalla, Karan Bhasin

March 1, 2024

Esther Lee Rosen, Robin Brooks

February 26, 2024

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Day

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

Students use active learning to solve COVID-19 problems

By dave winterstein.

The pervasive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic can leave us all feeling powerless at times. Students in the course Engineering Processes for Environmental Sustainability (BEE 2510) took back some power during the fall semester by addressing critical problems related to pandemic.

Instructors Jillian Goldfarb , assistant professor of biological and environmental engineering in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS), and Alex Maag, postdoctoral associate with Cornell’s Active Learning Initiative , assigned students to solve problems related to COVID-19, from the logistics of vaccine storage and transportation, to the disinfection of public spaces, and the sanitation and reuse of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Using the pandemic as the context for a student project was not without challenges, and the instructors hesitated to ask students to focus on an issue that might be a source of pain or uncertainty for some.

“We were nervous about assigning a COVID-19-related project,” Goldfarb said, “but the way we approached it empowered students to feel like there were solutions to these problems.”

Their approach hinged on the critical step of building a sense of community, Maag added.

First Goldfarb and Maag had the class work on group problem-solving by assigning various smaller tasks during class discussions. As students became comfortable working with each other in teams, they eventually were ready to work in groups on the final project.

The community-building exercises paid off. The students produced technical reports that proposed creative, efficient and technically sound solutions to PPE shortages and vaccine distribution.

Both instructors were impressed with the degree to which the class of primarily second-year students applied a broad range of concepts covered in the course.

“Students did a lot of outside-the-box thinking on the projects,” Maag said. “As a gateway course, the class is very broad in scope so we can’t go very deep into any one topic, but they took nearly all the concepts from class and connected them in their reports.”

“We were nervous about assigning a COVID-19-related project, but the way we approached it empowered students to feel like there were solutions to these problems.” Jillian Goldfarb

One group used geomapping to optimize vaccine distribution across the country. Another contacted their hometown hospitals to ask about PPE shortages as they developed requirements for designing sanitizing equipment.

Goldfarb also noted that the project inspired students’ passion for thinking about possible solutions and applying what they learned in class to areas about which many of them knew very little.

“The students were surprised by how much the introductory engineering knowledge they gained in this class could be so widely used to solve these problems,” she said, “and that will give them confidence as they go forward.”

Goldfarb and Maag developed their assignment with support from a 2019 grant from the Active Learning Initiative, through which the Department of Biological and Environmental Engineering is helping undergraduates apply their knowledge to complex current issues.

The project was funded by CALS and a gift from Alex ’87 and Laura Hanson ’87. The Active Learning Initiative, developed within the College of Arts and Sciences with help from the Hansons, is supported by Cornell’s Office of the Vice Provost for Academic Innovation and the Center for Teaching Innovation (CTI).

For more information on the initiative, contact CTI .

Dave Winterstein is a communication specialist in the Center for Teaching Innovation.

Media Contact

Abby butler.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

What COVID-19 taught 10 startups about pivoting, problem solving and tackling the unknown

Image: Photo by Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Tooba Durraze

Olivia zeydler.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- The COVID-19 crisis forced startups to rethink everything from their management to their business models.

- Pivoting taught these 10 startups key lessons on leveraging capabilities, moving quickly, and maximizing teams.

COVID has transformed how businesses run and how leaders lead. The World Economic Forum’s Global Innovators Community, a group of innovative start-ups and scale-ups, explained recently how they used their technologies and expertise to fight the pandemic – and what they learned in the process that they’ll apply to future crises.

The Innovator Communities are an invitation-only group of the world’s most promising start-ups and scale-ups that are at the forefront of technological and business model innovation.

Companies who are invited to become Innovators will engage with one or more of the Forum’s Centres , as relevant, to help define the global agenda on key issues.

Think your company would be a great fit? Please get in touch and tells us a bit more about your organization using this form .

1. Move fast and fix things MachineMetrics , an industrial IoT platform for machines, doubled down on remote technology monitoring during COVID-19 to help manufacturers monitor their factory productivity and supply chains from afar. Additionally, the company developed a program to provide free access to its technology to any manufacturer involved in the production of COVID-19-related manufacturing, such as ventilator components or testing and protective equipment or any COVID-19 related manufacturing.

Pivoting meant developing educational programs and delivery mechanisms for its new programs in about one week. The experience helped the company lean on strengths such agility and organizational trust, which were essential to both the company and its manufacturing customers’ success. Through this experience MachineMetrics learned how to balance the needs of the company with the needs of the industry its serves. When these needs are in alignment, you can move quickly to achieve remarkable things, said Graham Immerman, the Vice President of Marketing.

Have you read?

17 ways technology could change the world by 2025, 10 technology trends to watch in the covid-19 pandemic.

2. Learn first, act later KONUX , a technology company that uses artificial intelligence to support predictive maintenance of industrial plants, didn’t pretend to know what to do next or how the company should react. In the moment of great flux, Founder and CEO Andreas Kunze asked himself: “What is really the core of what we do? And in a scenario where our market collapsed, what assumptions would I still not challenge?” Such questions helped him focus on his core beliefs and the company’s strengths and values.

Said Kunze, in times of great change, “The role of the CEO needs to transform to Chief Learning Officer.” He said, “We need to learn about the market, customer, product, and people impact as fast and as much as we can. That is where innovation truly happens.”

3. Find new problems to solve Orbs , a public blockchain stack that helps businesses and governments develop blockchain applications, saw an opportunity to adapt its technology to the new challenges that COVID introduced to daily lives. A key challenge? How countries could safely open up their borders to both residents and visitors, and how individuals could prove authenticity of their health condition while maximizing privacy. “From the very first days of the COVID outbreak, we set our minds to figuring out how blockchain can be the technological foundation for current challenges,” said Netta Korin, co-founder at Orbs.

As a result, the company designed a blockchain-based health passport in which test results can be signed cryptographically. This allows holders to prove when, where and by whom they were tested for COVID or potentially any other diseases. Based on this data, countries can determine the terms under which an individual may or may not enter. Furthermore, it allows authentication of results wherever travellers go in order to track and monitor people’s paths in case of an outbreak, all the while minimizing privacy infringement. This experience taught Orbs that the real challenge is identifying the opportunity within a crisis. Thanks to these efforts, the company is currently in discussion with a government looking to adopt Orbs’ solution as part of the country’s public health platform.

4. Know your “why” Avellino shifted its business model during the crisis, pivoting from genetic data and diagnostics, to filling a gap in the testing market for the COVID-19 crisis. The change came about after just 3 weeks of brainstorming sessions. The company credits its agility to the team’s alignment on purpose and priorities, said Eric Bernabei, the Chief Sales and Marketing Officer.

There was "never a debate" about whether or not Avellino should make the pivot, explained Bernabei. The only discussion was about how to do it successfully, identifying potential risks and collaborating to ensure that it could identify trigger points for decisions and actions.

5. Find ways to foster community The pandemic brought unprecedented challenges with no established roadmaps or best practices for guidance. In that space, many companies saw the power and support networks that could provide. For instance, agtech company Mooofarm realized the value of community among its members. The company supports marginalized dairy farmers in underserved markets around the world and the pandemic underscored how the farmers that used its platform shared and learned from each other regarding cattle health and nutrition management, government schemes, subsidies and cattle trading. Progressive farmers shared dos and don'ts with each other and responded to queries about dairy farm management. To support this effort, the company is currently in the process of developing an online community to help this community better interact and strengthen its existing bonds.

6. Rethink business as usual Early in the crisis, 3D printing company 3YOURMIND Inc. , saw a way its technology could help generate PPE and respirator connectors. In only a few days, it leveraged its software technology to create a virtual factory of more than 40 professional 3D Printing suppliers and a digital inventory of more than 60 validated designs. This made it possible to deliver thousands of pieces of printed equipment, on-demand, with the highest degree of IP and data security.

The move has helped the company future-proof its business, as it saw the need for digitizing stocks and relocating production for key products and components. “Over the next 10 years, more than 8% of stock units will be virtualized and produced with on-demand 3D printing,” said Aleksander Ciszek, Chief Executive Officer at 3YOURMIND Inc. As a result, the company is helping firms to collect and assess parts data and create their own digital warehouses. “This is a tremendous task ahead of us,” said Ciszek.

7. Strengthen relationships Thanks to lockdowns and the need to communicate virtually, financial services and blockchain company Diginex went remote. It switched from running in-person consultations to a new approach that accommodated remote technology implementation. This meant standardizing its product offering to enable rapid scale-up of its technology solutions. This approach allowed Diginex to focus on its strength, the technology infrastructure, while engaging local partners to handle effective implementations. Said Miles Pelham, Diginex Chairman, the company has always valued its long-term partnerships, but this period has shown the importance of those relationships in helping the company adapt and scale.

8. Get creative The pandemic provided a special opportunity to contribute for Livinguard , a maker of innovative face masks and other PPE. Still, when work went remote, it needed to scale up while ensuring staff could work safely and transport goods after COVID halted air travel and other transport.

While most staff worked from home, the company found a locality not in full lockdown where it could run some key operations and where flights were still available. “We had to really switch gears and stretch our limbs,” said Livinguard’s EVP of Business Development Jonathan Pantanowitz.

9. Leverage your capabilities AI-powered insights company Contextere found the current pandemic created a transformational opportunity to advance productivity initiatives it couldn’t have imagined before the pandemic. The company, one that uses machine learning and industrial data to help employees execute their jobs more efficiently, saw the opportunity to apply its technology to its own company. This approach helped the team eliminate rework at Contextere and even identify new opportunities to contribute to the COVID-19 fight. Subsequent COVID-19 AI research the company conducted for its own staff led to the deployment of AI to support frontline workers, eliminating productivity barriers to overburdened workers during a critical time.

In times of great change, the role of the CEO needs to transform to Chief Learning Officer.

10. Embrace new challenges and new opportunities COVID exposed existing weaknesses and vulnerabilities – and made them more complex. Venture debt, for instance has become increasingly constrained due to regulatory restriction and conventional lending practices by financiers that demand physical collateral. For partner banks and VCs, “It is an even tougher environment, then it used to be, in relation to financing,” said Mohamed Wefati, the Founder and CEO of MIZA , a fintech company that helps support small and medium enterprises in the MENA region. “Access to finance is an issue for small enterprises.”

However, there are multiple initiatives launched by central banks and banks across the MENA region, for example, to stimulate credit for SMEs. MIZA’s main learning was that with the inevitable digital adoption sparked by COVID, small enterprises stand to benefit from increased access to finance due to their increased digital footprint. This new paradigm opens up increased opportunities for driving financial inclusion across the MENA region.

Last year, the World Economic Forum launched Strategic Intelligence , its flagship digital product to help individuals and organizations see the big picture on the global issues facing the world. It provides a tremendous resource for exploring the interconnections between over 250 different topics and keeping up to date on everything that could potentially be an opportunity or a risk to you or your organization. Strategic Intelligence enables organizations, like the Global Innovators, to keep abreast of risks, opportunities and trends, enabling them to take more of a data-driven approach to managing their business.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on COVID-19 .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Winding down COVAX – lessons learnt from delivering 2 billion COVID-19 vaccinations to lower-income countries

Charlotte Edmond

January 8, 2024

Here’s what to know about the new COVID-19 Pirola variant

October 11, 2023

How the cost of living crisis affects young people around the world

Douglas Broom

August 8, 2023

From smallpox to COVID: the medical inventions that have seen off infectious diseases over the past century

Andrea Willige

May 11, 2023

COVID-19 is no longer a global health emergency. Here's what it means

Simon Nicholas Williams

May 9, 2023

New research shows the significant health harms of the pandemic

Philip Clarke, Jack Pollard and Mara Violato

April 17, 2023

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impact of attitude toward peer interaction on middle school students' problem-solving self-efficacy during the covid-19 pandemic.

- 1 School of Educational Technology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2 Department of Industrial Education, Institute for Research Excellence in Learning Science, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

The outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic has promoted the popularity of online learning, but has also exposed some problems, such as a lack of interaction, resulting in loneliness. Against this background, students' attitudes toward peer interaction may have become even more important. In order to explore the impact of attitude toward peer interaction on students' mindset including online learning motivation and critical thinking practice that could affect their problem-solving self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic, we developed and administered a questionnaire, receiving 1,596 valid responses. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were re-tested, and structural equation modeling was applied. It was found that attitude toward peer interaction could positively predict middle school students' online learning motivation and critical thinking. Learning motivation and critical thinking also positively supported problem-solving self-efficacy. It is expected that the results of this study can be a reference for teachers to adopt student-centered online learning in problem solving courses.

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has led to the widespread practice of online learning in schools ( Zhao et al., 2021 ). Teachers and students in middle schools continue to integrate online learning into classrooms, which is further promoting the process of online and offline blended learning development ( Lee et al., 2021 ). A conceptual ecology of learning is necessary to embrace a series of learning environment “across boundaries traditionally separating institutions of education, popular culture, home, and community” ( Kumpulainen and Mikkola, 2014 , p. 51). However, the coevolution of people and their environments is an ongoing process ( Hilty and Aebischer, 2015 ). That is, online learning is intertwined with sociocultural environments ( Allen et al., 2015 ), and when people are not able to meet physically during the COVID-19 pandemic, they need more social interactions ( Kalmar et al., 2022 ). Peer interaction has been proved to benefit learning progression and contribute to deep learning ( Chadha, 2019 ). Online peer interaction embedded in learning design is useful for promoting students' learning outcomes, but previous research has mainly focused on the higher education group ( Lin et al., 2017 ; Martin et al., 2020 ). While online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic could have been a new experience for middle school students to interact with peers and their teachers ( Clark et al., 2021 ), attention to K-12 education in the literature is rare, and online learning had hardly been adopted by Chinese middle schools before the COVID-19 pandemic. As the pandemic came suddenly, most teachers in Chinese K-12 schools only conducted online one-way live-streamed lectures, and did not pay attention to interactive activities, leading to surface learning and polarization of students ( Yu and Wang, 2020 ). Thus, the present study aimed to explore the role of peer interaction in online learning based on Chinese K-12 students.

In fact, the pandemic promoted the universalization and ubiquity of online learning; thus, there is a need for more and deeper attention to online learning outcomes ( Ngo and Ngadiman, 2021 ). Learning outcomes consist of affective outcomes, cognitive outcomes, and skill-based outcomes ( Kraiger et al., 1993 ), of which motivation (as an affective outcome), critical thinking (as a cognitive outcome) and problem solving (as a skill-based outcome) have been the factors of most concern in the online learning research ( Zhou et al., 2021 ). These learning outcomes are important for not only higher education students, but also K-12 students. To explore the role of peer interaction in online learning for K-12 students during the pandemic, it is necessary to study the relationship among peer interaction, motivation, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Attitude is defined as a favorable or unfavorable evaluative reaction toward something or someone, exhibited in one's beliefs, motivation, or intended behavior ( Ajzen, 2005 ). Attitudes provide meaningful approaches to seek some degree of order, clarity, and stability in our personal motivation of reference ( Harmon-Jones and Harmon-Jones, 2021 ). As the measurement of the real interactive behavior is difficult, students' attitude toward peer interaction is used to explore the role of peer interaction in online learning. Attitudes include affective and cognitive components to predict motivation and behavior ( Ajzen, 2005 ). In contrast, mindsets consist of a collection of attitude judgments and cognitive processes and procedures to facilitate problem solving and completion of a particular task ( Gollwitzer et al., 1990 ). Moreover, mindsets drive cognitive processing, and capture the critical thinking that is an important behavioral outcome judgement ( Nolder and Kadous, 2018 ). Students' attitude toward peer interaction could have an impact on their mindsets ( Zulkifli et al., 2020 ; Thanasi-Boce, 2021 ), leading to different learning performance ( Kwon et al., 2019 ). To date, few researchers have investigated online learner profiles based on the mindset shared among students ( Zamecnik et al., 2022 ). Online learning profiles, problem solving, critical thinking, teamwork, and motivation are different in different areas and backgrounds ( Lawter and Garnjost, 2021 ). In particular, the profiles of middle school students who were born and grew up in the digital age, and so are known as “digital natives” ( Becker and Birdi, 2018 ) have not been studied. In line with this, the correlates between middle school students' attitude toward peer interaction, motivation, critical thinking, and problem solving were explored in this study.

Theoretical background

Attitude toward peer interaction in online learning.

Peer interaction is usually considered to be at the heart of the development of constructivist learning theory research ( Tenenbaum et al., 2020 ). In peer interaction, students can question others as free and active participants in social discourse, argument, and learning ( Castellaro and Roselli, 2015 ). The comparison of perspective will produce social cognitive conflict, and then generate consensus through interaction ( Tenenbaum et al., 2020 ). It has been shown that peer interaction can benefit learning progression and make students learn more deeply ( Chadha, 2019 ). Learner-learner interaction refers to the two-way communication among learners, such as exchanging ideas with classmates, discussing with each other, and getting feedback from other learners ( Wang et al., 2022 ). Moreover, middle school students had hardly ever experienced complete online learning before the COVID-19 pandemic. When the pandemic suddenly broke out, some students could have had difficulty adapting to online learning, leading to learning anxiety, loneliness, and even depression ( An et al., 2020 ; Perkins et al., 2021 ; Ying et al., 2021 ). Peer interaction might be the key to solving these affective and psychological problems ( Yao and Zheng, 2017 ; An et al., 2020 ). Especially, social and peer influence is of great importance for adolescents ( Tsai et al., 2015 ), so peer interaction could be an extremely important factor for middle school students' online learning. In brief, peer interaction is beneficial for students' development of knowledge and ability ( Chadha, 2019 ), and could also help improve students' attitudes toward online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Ala et al., 2021 ; Chu et al., 2021 ; Ngo and Ngadiman, 2021 ). However, it is difficult to measure the real peer interactive behaviors of students, as the peer interactions occur naturally in social media, but are not limited to a specific learning platform. Students' attitude could show their preference for a certain behavior ( Ajzen, 2005 ). Thus, students' attitude toward peer interaction in middle high school was explored in this study.

Motivation as emotional mindset

The concept of mindsets is based on Dweck (1999) framework in which it was proposed that mindsets determine one's goals, motivation, and beliefs about effort. As a result, mindsets can organize associated constructs into a coherent motivational framework or “meaning system” ( Yu and McLellan, 2020 ). An important motivational factor that might influence individuals' willingness to engage with a task is their emotional mindset ( Wols et al., 2020 ). Students' motivation plays a fundamental role in academic achievement. In fact, Yu and McLellan (2020) applied person-centered motivation to study some key elements of the mindset-based meaning system. Although there are different ways to induce students' growth mindset, most of the studies endorsed that the growth mindset can indeed modify the learning processes ( Kania et al., 2017 ). Learning motivation is an important factor leading to success in online learning, especially for K-12 students ( Zuo et al., 2021 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about great changes to students' learning, such as the disruption of social networks and teachers being less focused on the individual. Students in middle school have lost their traditional learning motivation sources, but have attained new motivation sources ( Uka and Uka, 2020 ). Learning motivation can improve academic outcomes by catering to learners' needs in online learning platforms ( Baker et al., 2016 ). Although it has been studied in much of the online learning research ( Zhou et al., 2021 ), little research has covered learning motivation in emotional mindset under the threat of COVID-19; thus, in this research, learning motivation was studied as an emotional mindset of online learning.

Critical thinking as cognitive mindset

Critical thinking is a kind of ability acquisition of online learning ( Zhou et al., 2021 ), which usually refers to skills of reasoning, evaluation, analysis, judgment, conceptualization, understanding, and reflection ( Guiller et al., 2008 ; van Laar et al., 2017 ). Individuals with a deliberative mindset are also more likely than those with an implemental cognitive mindset to take longer to reach a judgment ( Henderson et al., 2008 ), indicating their openness to information and suspension of judgment. The deliberative mindset captures the mechanics behind a “questioning mind,” a “critical evaluation of evidence,” and the responsibility to “be alert” to evidence ( Nolder and Kadous, 2018 ). In this research, critical thinking was studied as a mindset to question and to be alert for knowledge acquisition during online learning.

The Internet provides a good way for students to develop their critical thinking, as students could gain much information to help them think critically. Critical thinking is thought to be one of the most important outcomes of online learning, and previous researchers have tried to design online courses and tools to promote students' development of their critical thinking ( Goodsett, 2020 ; Varenina et al., 2021 ). This study focused on self-reporting by middle school students to evaluate their cognitive mindset related to online learning.

Problem-solving self-efficacy

Problem solving is an important ability acquisition of online learning ( Zhou et al., 2021 ), and refers to the skills of using information and communication technology to cognitively process and understand a problem situation in combination with the active use of knowledge to find a solution to a problem ( van Laar et al., 2017 ). Problem solving involves different skills, such as finding the nature of the problem, choosing problem-solving steps and strategies, selecting appropriate information, allocating appropriate sources, and monitoring the problem-solving process ( Sternberg, 1988 ). Problem solving is a key competency in online learning ( Aslan, 2021 ), and the Internet provides convenient support for learners to solve problems ( Jordan and McDaniel, 2014 ). For learners, problem solving is the key to learning success in a future-oriented society ( OECD, 2017 ). As little research has considered how students' peer interaction supports their problem solving, the present study would explore the relationship between peer interaction and problem solving.

In studies using self-reported scales, self-efficacy of performance or ability has been used widely in problem solving ( Calaguas and Consunji, 2022 ). Self-Efficacy refers to individuals' beliefs about their abilities to perform expected behaviors ( Bandura, 1994 ). According to Bandura (1997) , the problem-solving self-efficacy could be defined as the students' perceptions of their problem-solving success. In previous researches, problem-solving self-efficacy (PSSE) have been used widely to represented learners' perceptions of their problem-solving abilities ( Bandura, 2006 ; Kyung-hee, 2016 ; Salazar and Hayward, 2018 ). In this research, student' PSSE would be measured to reflect the perception of problem-solving process.

Previous studies found that online learning is useful for students, particularly in terms of learning outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Jung and An, 2021 ; Choi-Sung, 2022 ). On the contrary, Hong et al. (2021a , 2022) found learning ineffectiveness through online learning, particularly in practical skill development ( Hong et al., 2021b ). Koehler et al. (2022) found that while students collaboratively interacted in the problem-solving process, individuals with a strong problem-solving presence valued peer interaction as an important part of the learning process, were willing to invest time engaging in the discussion, and maintained a consistent presence. Peer interaction could help to improve the motivation of students in online learning. For example, Yang and Chang (2012) found that peer interaction via blogs could improve students' learning motivation. Researchers found that for students in higher education, online peer interaction could improve their level of motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Thanasi-Boce, 2021 ; Kang and Zhang, 2022 ), but there has been a lack of focus on K-12. From this, we could speculate that for middle school students, the attitude toward online peer interaction during the epidemic could positively affect their online learning motivation. Hence, the following hypothesis was formulated in this study:

H1: The attitude toward online peer interaction could positively predict the online learning motivation of middle school students.

The mindset reflects the idea that individuals' cognitive processing determines both the content and strength of their resulting attitudes ( Yu and McLellan, 2020 ). Critical thinking was thought to need a cognitive process, referring to the exchange and discussion of ideas with peers involved in the collaborative process of knowledge construction ( Kuhn, 1991 ). Therefore, we could speculate that peer interaction could positively help to develop students' critical thinking. In fact, this has been proved for primary school students ( Chou et al., 2015 ) and for undergraduate students ( Oh et al., 2018 ; Zulkifli et al., 2020 ). What is more, previous researchers found that online peer discussion helped to develop university students' critical thinking better than face-to face discussion, as they would provide more well thought-out and reasonable evidence ( Guiller et al., 2008 ). We could speculate that this might also be applicable to junior middle school students. Hence, the hypothesis formulated in this study was as follows:

H2: Attitude toward online peer interaction could positively predict the critical thinking of middle school students.

Students collaborate in groups to solve a problem, and analyze the formation of the problem to identify facts about the problem situation so that they can establish their representation of the problem and have a deeper understanding of the causes of problems. Then, they propose possible solutions, where they evaluate the gap between the current state and the desired state and address the solutions to the problem ( Wu and Nian, 2021 ). These processes sometimes provide both an autonomy-controlling and an autonomy-supportive need to learn knowledge that may be maintained and enhanced by students' motivation ( Wu et al., 2020 ). Moreover, individuals with a fixed emotion mindset believe that emotions are not changeable and cannot be controlled. Individuals with a growth emotion mindset believe that emotions are malleable and can be changed with effort and experience ( Wols et al., 2020 ). For example, learning motivation is one of the major predictors of problem solving that is key in the nursing training field ( Yardimci et al., 2017 ). To understand the correlates between middle school students' learning motivation and PSSE in online learning, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H3: Learning motivation could positively predict the PSSE of middle school students.

A problem is generally viewed as a discrepancy between desired goals and an existing state ( Chi and Glaser, 1985 ), and problem solving is the process of taking actions to resolve this discrepancy ( Shermerhorn, 2013 ). Researchers have suggested specific frameworks to capture effective problem solving; together, all frameworks provide insight into the critical reasoning processes learners engage in as they resolve ill-structured problems ( Tawfik et al., 2020 ). While variation exists across focus and articulated problem-solving in online learning phases, these frameworks involve two main areas: problem finding with critical thinking (e.g., articulating a problem, constraints, clarifying diverse perspectives) and generating solutions with critical thinking (e.g., suggesting and evaluating solutions addressing identified problems) ( Koehler et al., 2022 ). Researchers found that critical thinking had positive effects on problem solving ( Kanbay and Okanli, 2017 ). Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H4: Critical thinking could positively predict the PSSE of middle school students.

Peer interaction has an influence on problem solving because students rely on supportive social responses to enact most of their strategies to solve problems ( Jordan and McDaniel, 2014 ). Students need to clarify or reorganize their views and plans when solving problems in peer groups, so it could be considered that the social interaction in groups is an important aspect of production power ( Jordan and McDaniel, 2014 ). In online learning, peer interaction is also important for problem solving, but the outcome depends on the peers' competency levels and their motivation ( Kwon et al., 2019 ). Cheng and Chau (2016) revealed that peer interaction in online learning was not at the desired level, and there was a need for studies to promote attitude toward peer interaction in online learning to enhance problem solving. However, peer interaction is one of the limitations of distance education which is widely used throughout the pandemic ( Aslan, 2021 ). To understand how attitude toward peer interaction is related to online problem solving, in this research, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H5: For middle school students, attitude toward online peer interaction could positively predict PSSE mediated by learning motivation and critical thinking.

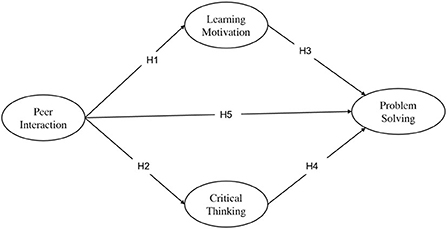

The current study adopted a person-centered approach to examine the ways in which mindsets and associated attitude toward peer interaction constructs cohered with emotional motivation and functioned together with critical thinking as a meaningful system related to PSSE. Specifically, drawing on attitude theory and mindset theory, this study addressed the research model as explained in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . The hypothesis model.

Participants

From July 15 to July 21, 2020, questionnaires were distributed to students in eight middle schools for the prior study, and a total of 352 sample data were collected for the EFA of the scale. The prior study samples were mainly from Beijing, Liaoning, Shandong, and Henan provinces. Invalid samples were deleted according to polygraph items, and a total of 301 valid samples were retained of which 155 (51.5%) were from boys and 146 (48.5%) from girls. There were 90 (29.9%) seventh graders, 164 (54.5%) eighth graders, and 47 (15.6%) ninth graders.

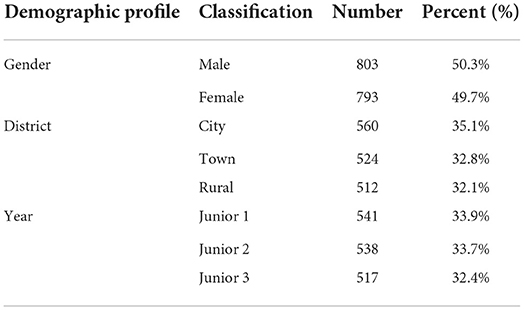

From October 20 to November 1, 2020, questionnaires were randomly distributed to junior high school students in 34 provinces or districts of China. A total of 61,419 responses were received, of which 25,805 were retained after polygraph screening. We randomly selected a similar number of different types of people in the large sample to approximate stratified sampling. A total of 1,596 valid samples were randomly selected. The demographic information of the samples is shown in Table 1 . There were 803 (50.3%) boys and 793 (49.7%) girls. The proportion of students from different districts was similar, as well as that of different grades.

Table 1 . Demographic information of participants ( N = 1,596).

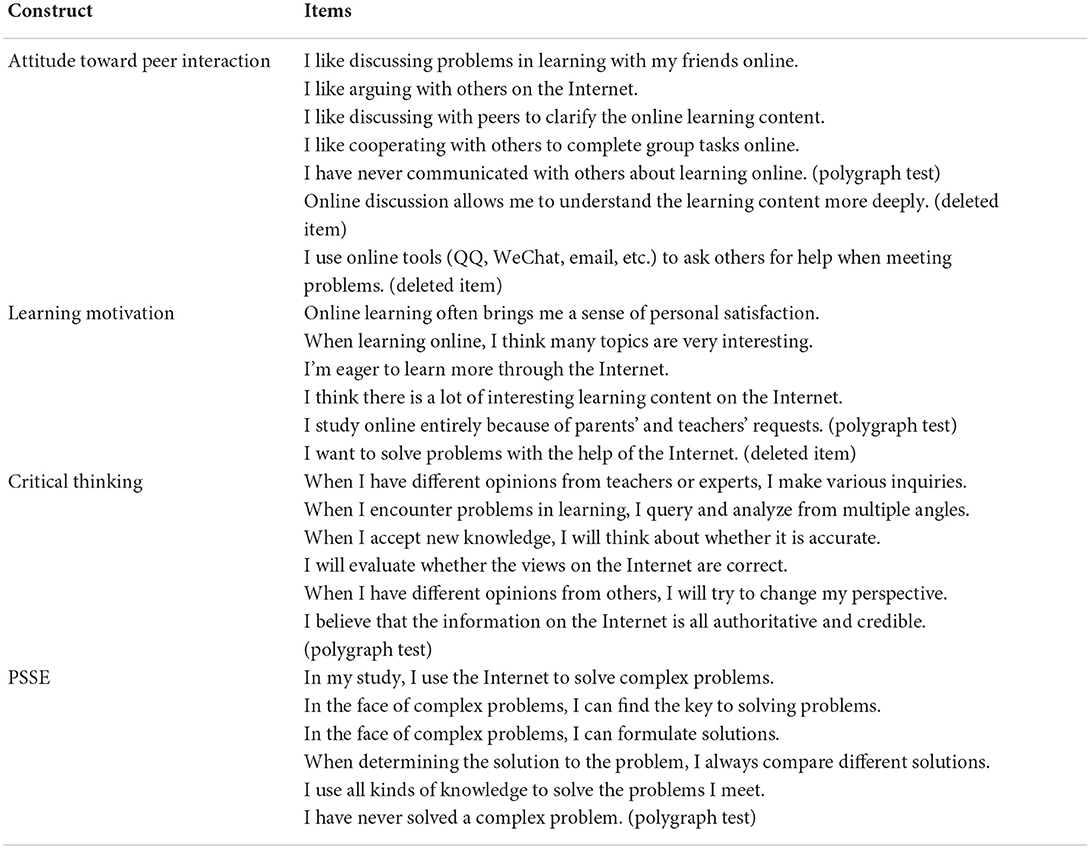

In this study, the questionnaire items were adapted from the relevant literature. The original measurement of peer interaction was adapted from six items of Active and Collaborative Learning in the National Survey of Student Engagement ( Kuh, 2001 ), the measurement of learning motivation was adapted from five items of Deep Motivation in R-SPQ-2F of Biggs et al. (2001) , the measurement of critical thinking was adapted from five items of the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory ( Facione, 1990 ), and the measurement of PSSE was adapted from five items of Han (2020) combined with Bandura (2006) Self-Efficacy scale.

Content validity was then examined by two educational technology experts and three middle school students. Some items with unclear meaning were revised. The questionnaire used a 5-point Likert scale, with options “ strongly disagree ,” “ disagree ,” “ neutral ,” “ agree ,” and “ strongly agree .” The higher the score, the higher the degree of agreement. After data collection, we tested the reliability and validity of the questionnaire items and constructs for subsequent structural equation modeling. The remaining items are listed in the Appendix .

Data analysis

To further test the content validity of the scale, nine experts were invited to judge and score the relevance between each item of the scale and the construct it belongs to. A 5-point scale was used in this study, with options “ uncorrelated ,” “ weakly correlated ,” “ moderately correlated ,” “ strongly correlated ,” and “ very correlated .” For each item, the proportion of experts who agreed that this item was strongly related to the construct (score 4 or 5) to the total number is called the Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI); it needs to reach 0.78 ( Lynn, 1986 ).

Before data analyses were performed, normality was tested. All the measured items had appropriate skewness (ranging from −0.893 to −0.295) and kurtosis (ranging from −0.216 to 0.954), smaller than the requisite maximum values of |1| and |2|, respectively, indicating that the data of all items were close to the normal distribution ( Noar, 2003 ).

Data analysis consisted of four stages: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), reliability analysis, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). EFA and reliability analysis of the scale were conducted with SPSS20.0, and CFA and SEM were conducted with Mplus 8.3. In the prior study, 301 samples were used for EFA and reliability analysis to test the scale. In the formal study, a randomly selected subsample 1 ( n = 799) was used for EFA, and subsample 2 ( n = 797) was used for CFA and SEM. In the reliability analysis, all 1,596 samples were used. Bootstrapping was used 1,000 times in the indirect effect test in SEM.

In EFA, principal component analysis and the maximum variance rotation method were used to extract the factors, and components were extracted with eigenvalues > 1. If the explained variance of the first factor before rotation is <50%, it can be considered that there is no serious significant common method bias ( Hair et al., 2014 ). Items with cross factor loadings or low loadings (<0.5) were deleted ( Deng et al., 2017 ).

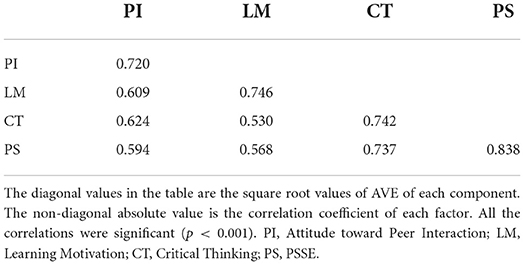

In CFA and SEM, the standards recommended by Hair et al. (2014) were adopted. Accordingly, indices of χ 2 / df (<5), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (<0.10), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (< 0.05), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (>0.90), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (>0.90) were used to check the model fit degree. Then Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (>0.5) and Construct Reliability (CR) (>0.7) were calculated using factor loadings (λ) to check the convergent validity of the scale. The square root values of AVEs of components were compared with the correlations between components to check the discriminant validity of the scale. The correlations between all factors were tested for significance before SEM.

In the reliability analysis of the scale, the internal consistency coefficients' Cronbach's α values were calculated, where the whole scale and all constructs needed to be higher than 0.7 ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ).

Measurement model

In the content validity test stage, according to the nine experts' evaluation, four items were deleted as their I-CVI did not reach 0.78. A total of 21 items with good content validity were saved in the scale.

In the prior study, we conducted EFA using the 301 valid samples to explore the structural validity of the scale. Three items were deleted in three rounds of principal component analysis, as they have cross factor loadings (FL > 0.5 on two factors). The deleted items and retained items are shown in the Appendix . After that, the EFA result showed good validity. The internal consistency coefficient test showed good reliability of the scale. The Cronbach's α of the whole scale was 0.954, and the values of the subscales were between 0.850 and 0.945. All the construct reliabilities were higher than 0.7, indicating good reliability of the scale in the prior study.

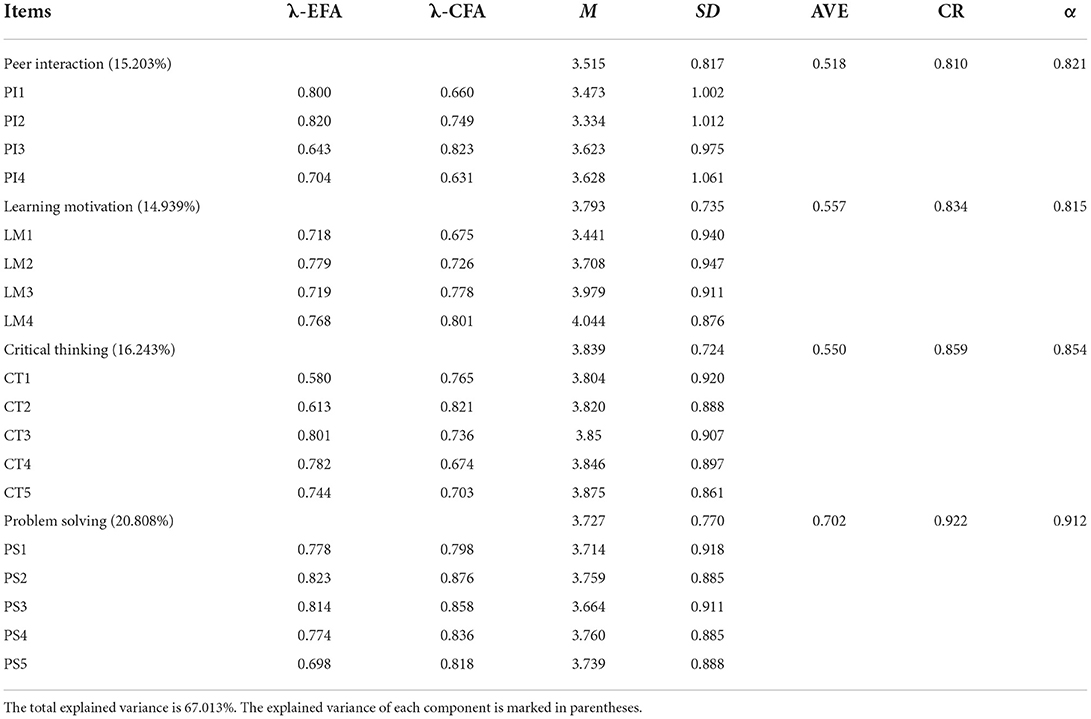

In the formal study stage, the EFA results showed good validity of the scale. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure value was 0.917 ( p < 0.001), indicating that it was suitable for factor analysis. The explained variance of the first factor before rotation was 43.520%, indicating no serious significant common method bias. A total of four main factors were obtained, and the total explained variance was 67.013%. The loadings of each item on the factor were between 0.580 and 0.823 (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Means, standard deviations, factor loadings (λ), AVEs, and construct reliability.

In the formal study stage, CFA was carried out to verify the structural validity of the scale. The model fit index of χ 2 was 608.769, df was 129, χ 2 / df was 4.719 (<5), RMSEA was 0.068 (<0.08), CFI was 0.942 (>0.90), TLI was 0.931 (>0.90), and SRMR was 0.041(< 0.05), indicating that the fit for the items of the scale was acceptable. All standardized factor loadings were in a good range of 0.631–0.876. The values of AVE were all higher than 0.5, and CR was higher than 0.7, indicating good convergent validity. All the square root values of AVE of each component were higher than the correlations between it and other components (see Table 3 ), indicating good discriminant validity. All the correlations between every two factors were significant.

Table 3 . Correlations between components and AVE of the components.

In the formal study stage, the internal consistency coefficient test showed good reliability of the scale. The Cronbach's α of the whole scale was 0.920, and the values of the subscales are shown in Table 2 . All the construct reliabilities were higher than 0.7, indicating good reliability. Means of components were all above the midpoint 3, as shown in Table 2 .

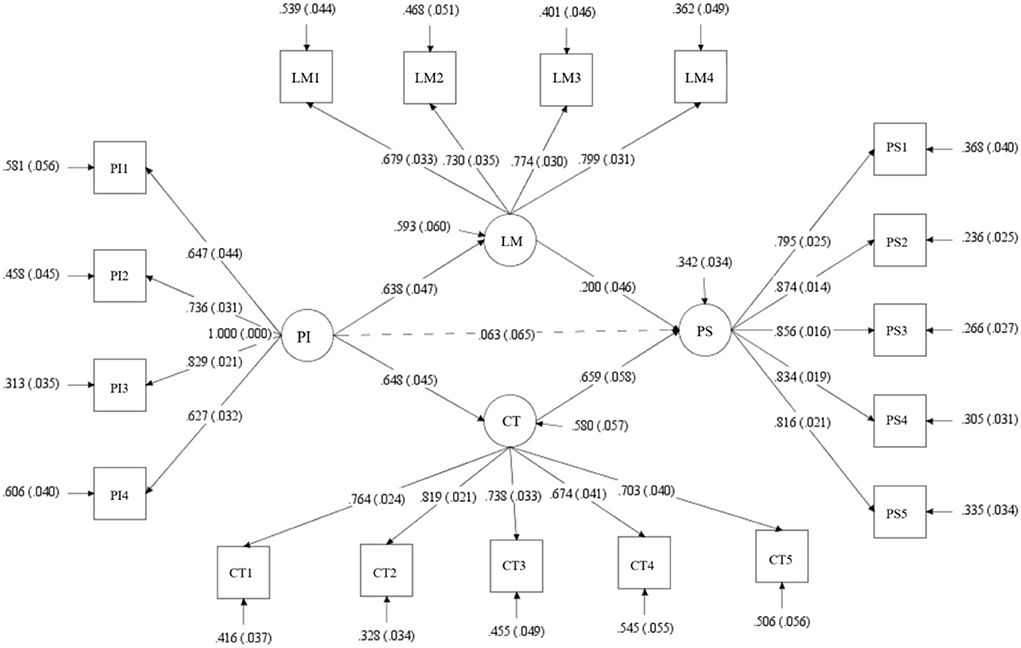

Structural model

The model fit indices of the structural equation model (SEM) were good using the 797 samples for verification. The value of χ 2 was 632.437, df was 130, χ 2 / df was 4.865 (<5), RMSEA was 0.070 (<0.08), CFI was 0.939 (>0.90), TLI was 0.929 (>0.90), and SRMR was 0.048 (< 0.05), indicating a good fit of the structural equation model. The verification of the research model is shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2 . The verification of the structural model. The figure shows the SEM results of bootstrap 1,000 times. PI, Attitude toward Peer Interaction; LM, Learning Motivation; CT, Critical Thinking; PS, PSSE.

For middle school students, the attitude toward peer interaction could significantly positively predict their online learning motivation, of which the effect was 0.638 ( p < 0.001), indicating that H1 was supported. Attitude toward peer interaction could significantly positively predict critical thinking, of which the effect was 0.648 ( p < 0.001), indicating that H2 was supported. Learning motivation could positively predict PSSE, of which the effect was 0.200 ( p < 0.001), indicating that H3 was supported. Critical thinking could positively predict PSSE, of which the effect was 0.659 ( p < 0.001), indicating that H4 was supported.

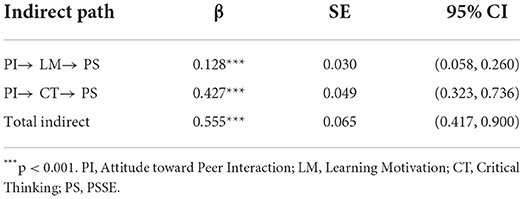

In the path analysis, the attitude toward peer interaction did not have a significant direct effect on PSSE, of which the path effect was 0.063 ( p = 0.331). To test the indirect effect, the bootstrap method was used. The 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was used to test whether there was an indirect effect. If the 95% CI does not include 0, an indirect effect exists ( Guo et al., 2018 ). As shown in Table 4 , the indirect effect from the attitude toward peer interaction to PSSE through learning motivation was 0.128 ( p < 0.001), and the 95% CI did not include 0. The indirect effect from attitude toward peer interaction to PSSE through critical thinking was 0.427 ( p < 0.001), and the 95% CI did not include 0. This indicated that attitude toward peer interaction could indirectly predict PSSE through learning motivation and critical thinking, respectively. This suggested that learning motivation and critical thinking played a full mediating role in how attitude toward peer interaction predicted PSSE. H5 was supported.

Table 4 . Indirect effect between peer interaction and PSSE.

The values of explanatory power (R 2 ) of learning motivation, critical thinking, and PSSE were, respectively, 0.407, 0.420, and 0.658. This showed that the variables of each facet had effective explanatory power of the model, as they were above the threshold of 0.3 ( Cohen, 1977 ).