10 Survey Tools for Academic Research in 2024

- Important Features

Survey Panels

- Additional Tools

1. SurveyKing

2. alchemer, 3. surveymonkey, 4. qualtrics, 5. questionpro, 6. sawtooth, 7. conjointly, 8. typeform, 10. google forms.

- Employee Feedback

- Creating the Survey

- Identity Protection

- Research Tools

Need a research survey tool? Features include MaxDiff, conjoint, and more!

These ten survey tools are perfect for academic research because they offer unique question types, solid reporting options, and support staff to help make your project a success. This article includes a detailed review of each of these nine survey tools. In addition to these survey tools, we include information about other research tools and survey panels.

Below is a quick summary of these nine survey tools. We list the lowest price to upgrade, which usually has the featured s needed for research projects. We also include a summary of the unique features of each tool. Most survey software has a monthly subscription; we denote when a tool requires annual pricing is required.

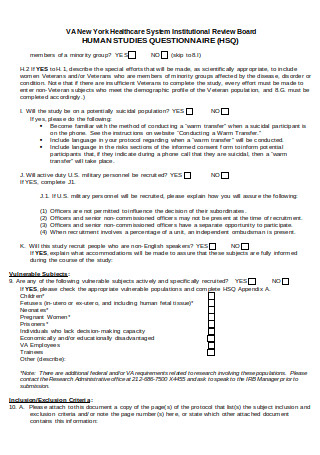

| Tool | Upgrade Price | Important Features |

|---|---|---|

| SurveyKing | $19/mo | MaxDiff, conjoint, semantic differential, mobile ready Likert scale, various rankings, panel respondents, anonymous link |

| Alchemer | $249/mo (for research questions) | MaxDiff, conjoint, image heat map, text highlighter, continuous sum, semantic differential, panel respondents, advanced reporting, data cleaning |

| SurveyMonkey | $99/mo | Image heatmap, matrix of dropdowns, panel respondents, significant difference, data cleaning |

| Qualtircs | $120/mo (billed annually – for research projects) | MaxDiff, conjoint, card sort/group, continuous sum, image heat map, text highlighter, drill down, panel respondents |

| QuestionPro | Research questions require a custom quote. | MaxDiff, conjoint, continuous sum, image heat map, text highlighter, panel respondents |

| Sawtooth | $4,500 – $11,990 annually. | Specializes in MaxDiff and conjoint. Bandit MaxDiff and Menu based conjoint. |

| Conjointly | $1,795 annually | MaxDiff, conjoint, claims testing |

| Typeform | $29/mo | Beautiful UI, integrations, calculator feature, flow charts for skip logic. |

| Hubspot | Starts at $15/user/mo | Automations, custom properties |

| Google Forms | Free | Simple and elegant UI, trusted brand name |

Important Features of Research Survey Software

Academic research surveys often require advanced question types to capture the necessary data. Many of the tools we mention in this article include these questions. However, some projects also require specialized features or the ability to purchase a panel. To help guide your decision in choosing the best piece of software for your project, we’ll summarize some of the most critical aspects.

Research Questions

Standard multiple-choice questions can only get you so far. Here are some question types you should be aware of:

- MaxDiff – measure the relative importance of an attribute. It goes beyond a standard ranking or rating by forcing respondents to pick the least and most valued items from a list. Rankings and other types only can you what is liked, not what is disliked. A statistical model will give you the probability of a user selecting an item as the most important. Latent class analysis can help you identify groups of respondents who value different attributes.

- Conjoint – Similar to MaxDiff in terms of finding importance, respondents evaluate a complete product (multiple attributes combined). This simulates real word purchasing decisions. A statistical model is also used to compute the importance of each item.

- Van Westendorp – Asks respondents to evaluate four price points. This shapes price curves and gives you a range of acceptable prices.

- Gabor Granger – Asks users whether or not they would purchase an item at specific price points. Price points are shown in random order to simulate real-world buying conditions. The results include a demand curve, giving you the revenue-maximizing price.

- Likert Scale – Measure attitudes and opinions related to a topic. It’s essential to use a mobile-ready Likert scale tool to increase response rates; many tools use a matrix for Likert scales, which could be more user-friendly.

- Semantic differential scale – a multirow rating scale that contains grammatically opposite adjectives at each end. It is used similarly to a Likert scale but is much easier for respondents to evaluate.

- Image heat map – Respondents click on places they like on an image. The results include a heat map showing the density of clicks. This is useful for product packaging.

- Net Promoter Score – Respondents choose a rating from 0-10. Many companies use this industry-standard question to benchmark their brand perception. This question type is necessary if your academic project measures brand reputation.

Anonymous Survey Links

Many academic surveys can deal with sensitive subjects or target sensitive groups. For this reason, assuring anonymity for respondents is crucial. Choosing a platform with an anonymous link is essential to increase trust with respondents and increase your response rates.

Data Segmentation

Comparing two groups within your survey data is essential for many research projects. This is called cross tabulation . For example, consider a survey where you ask for gender along with product satisfaction. You may notice that males are not satisfied with the product while females are.

You can take this further and compute the statistical significance between the groups. In other words, make the differences that exist between two data sets due to random chance or not. Your comparison is statistically significant if it’s not due to random chance.

Some lower-end survey tools may not offer any segmentation features. If this is the case, you need to download your survey data into a spreadsheet and create pivots of set-up custom formulas.

Skip Logic and Piping

If your academic project has questions that only a specific subset of respondents need to answer, then some logic will help streamline your survey.

Skip logic will take you to a new page based on answers to previous questions. Display logic will show a question to a user based on previous questions; perfect for follow-up.

Answer piping will allow you to carry forward answers from one question into another. So, for example, ask someone which brand names they have heard of, then pipe those answers into a ranking question.

Data Cleaning

Making sure your responses are high quality is a big part of any survey research project. For example, if people speed through the survey or mark all the first answers for questions, those would be low-quality responses and should be removed from your data set. Some tools highlight these low-quality responses, which can be a helpful feature.

For platforms that do not offer a data cleaning feature, it’s generally possible to export the data to Excel, create formulas for time spent, answer straight-lining, then remove the needed data. You can also include a trap question to help filter out low-quality responses.

Great Support

Many academic projects require statistical analysis or additional options for the survey. Using a tool with a support staff that can explain a statistical model’s intricacies, help build custom models, or adds features on request will ensure your project is a success. With SurveyKing, custom-built features are billed at $50 per hour, making custom projects feasible for small budgets.

Asking classmates to take your survey, posting it on social media, or distributing QR code surveys around campus is a great way to collect responses for your project. But if you need more responses with those methods, purchasing additional answers might be required.

A panel provider will enable you to target a specific demographic, job role, or hobby type. When setting up a survey with a penal provider, you always want to include screening questions (on the first page) to ensure they meet your criteria, as panel filters may not be 100% accurate. Generally, panel responses start around $2.50 per completed response. Cint is one of the largest panel providers and works well with any survey platform.

Additional Research Tools

Before deep diving into the survey software list, here are some additional tools and resources that might assist in your project. These can help shape your survey by conducting preliminary research or using it as a substitute if conducting a study is not feasible.

- Hotjar – They offer simple surveys and many tools to help capture feedback and data points from a website. A feedback widget customized for websites in addition to a heat map tool to show where users click the most or to identify rage clicks. A tool like this could be helpful if your academic projects revolve around launching or optimizing a website.

- Think with Google – Used to help marketers understand their audience. The site contains links to Google Trends to search for the popularity of key terms over time. They also have a tool that helps you identify your audience based on popular YouTube channels. Finally, they have a “Grow My Store Tool” that recommends tips for improving an online store.

- Google Scholar – A specific search engine used for scholarly literature. This can help locate research papers related to the survey you are creating.

- MIT Theses – Contains over 58,000 theses and dissertations from all MIT departments. The database is organized by department and lets you search for keywords.

SurveyKing is the best tool for academic research surveys because of a wide variety of question types like MaxDiff, excellent reporting features, a solid support staff, and a low cost of $19 per month.

The survey builder is straightforward to use. Question types include MaxDiff, conjoint, Gabor Granger, Van Westendorp, a mobile optimized Likert scale, and semantic differential.

The MaxDiff question also includes anchored MaxDiff and collecting open-ended feedback for the feature most valued by a respondent. In addition, cluster analysis is available to help similar group data together; some respondents might value specific attributes, while other groups value others.

The reporting section is also a standout feature. It is easy to create filters and segment reports. In addition, the Excel export is well formatted easily for question types like ranking and Likert Scale, making it easy to upload into SPSS. The reporting section also gives the probability for MaxDiff, one of the few tools to offer that.

The anonymous link on SurveyKing is a valuable feature. A snippet at the top of each anonymous survey is where users can click to understand whether their identities are protected.

The software also offers a Net Promoter Score module which can come in handy for projects that deep dive into brand reputation.

Some downsides to SurveyKing include no answer piping, no image heat maps, no continuous sum question, and no premade data cleaning feature.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | Yes | Only lacks an image heat map. |

| Anonymous survey link | Yes | |

| Data segmentation | Yes | No significant difference calculations, no advanced criteria. |

| Survey logic | Yes | No answer piping. |

| Survey panels | Yes | Support generally will setup the backend for you and perform quality checks. |

| Data cleaning | In development | Excel export can be downloaded to calculate time spent and straight-lining answers. |

As a platform with lots of advanced question types and a reasonable cost, Alchemer is an excellent tool for academic research. Question types include MaxDiff, conjoint, semantic differential, image heat map, text highlighter, continuous sum, cascading dropdowns, rankings, and card grouping.

Reporting on Alchemer is a standout feature. Not only can you create filters and segment reports, but you can also create those filters and segments using advanced criteria. So if you ask a question about gender and hobby, you can make advanced criteria that match a specific gender and hobby.

In addition, their reporting section also can do chi-square tests to calculate the significant difference between the two groups. Finally, they also have a section where you can create and run your R scripts. This can be useful for various academic research projects as you can create custom statistical models in the software without needing to export your data.

Alchemer is less user-friendly than some other tools. The platform is a little clunky; things like MaxDiff require respondents to hit the submit button to get to the next set. Radio buttons need respondents to click inside of them instead of the area around them.

The pricing is reasonable for a student; $249 a month for access to the research questions. However, if you can organize your project quickly, you may only need one month of access.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | Yes | MaxDiff does give probability or share of preference. |

| Anonymous survey link | No | They do have a setting for anonymous responses to turn off geo tracking, but no specific link telling users the survey is anonymous. |

| Data segmentation | Yes | Includes the ability to create advanced criteria (e.g. combing multiple questions into one rule). |

| Survey logic | Yes | Display and skip logic, along with answer piping. |

| Survey panels | Yes | |

| Data cleaning | Yes | You can quarantine bad responses using their tool in the reporting section. |

As the most recognized brand for online surveys, SurveyMonkey is a reliable option for academic research. While the platform does not have any research questions, it offers all the standard question types and a clean user interface to build your surveys.

One advanced question type they do have is the image heat map. Their parent company Momentive does offer things like MaxDiff and conjoint studies, but you would need to contact sales to get a quote, meaning this could be out of budget for students.

The reporting on SurveyMonkey is good. You can easily create filters and segments. You can also save that criterion to create a view. The views enable you to toggle between rules quickly.

One of the main downsides to SurveyMonkey is the cost. For the image heat map and to create advanced branching rules, you need to upgrade to their Premier plan, which costs $1,428 annually. To get statistical significance, you would need their Primer plan, which is $468 annually.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | No | Image heat map is offered under the most expensive plan; other research tools are available under their parent company platform. |

| Anonymous survey link | No | They do have a setting for anonymous responses to turn off tracking, but no specific link telling users the survey is anonymous. |

| Data segmentation | Yes | Statistical significance is only available on an annual plan. |

| Survey logic | Yes | No display logic. Advanced branching rules are available on the Premier plan. |

| Survey panels | Yes | |

| Data cleaning | Yes | There is an option to identify low-quality responses, but it’s only available on the Premier plan. |

As the survey tool known for experience management, Qualtrics has some nice features for research projects. For example, they offer both MaxDiff and conjoint in addition to tools like drill-down, continuous sun, image heat map, and a text highlighter.

Reporting on the tool offers the ability to create filters and segments. For segments, it’s called a report breakout, and it appears there is no ability to create a breakout with advanced criteria. However, filers do allow you for advanced criteria.

There is a custom report builder option to create custom PDF reports. You can add as many elements as needed and customize the information displayed, whether a chart type or a data table.

Overall, Qualtrics could be more user-friendly and may require training. The survey builder and reporting screens could be more cohesive. For example, to add more answer options, you need to click the “plus” symbol on the left-hand side of the question instead of just hitting enter or clicking a button right below the current answer choice. In addition, the reporting section will display things like mean and standard deviation for simple multiple-choice questions before showing simple response counts.

One drawback to Qualtrics is the pricing. For example, you would need to pay $1,440 for an annual plan to use the research questions. But many universities have a licensing agreement with Qualtrics so students can use the platform. When you sign up for a new account, you can select academic use, enter your Edu email, and they will check if your university has a license agreement.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | No | Only available on the $1,440 annual plan. |

| Anonymous survey link | Yes | Even with the , you still need to go into options to “anonymize” the survey. Once the option is enabled, there is still no message to respondents that the survey is anonymous. |

| Data segmentation | Yes | No advanced segments, simple report breakouts. The significant difference is only available using a “Dashboard widget”. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Skip and display logic along with answer piping. |

| Survey panels | Yes | |

| Data cleaning | Yes | More advanced data cleaning methods are available under the custom DesignXM package. |

A survey platform with all the needed research questions, including Gabor Granger and Van Westendorp, QuestionPro is a quality research tool.

The reporting on QuestionPro is comprehensive. They offer segment reports with statistical significance using a t-test. In addition, they offer TURF analysis to show answer combinations with the highest reach.

For conjoint, offer a market simulation tool that can forecast new product market share based on your data. That tool can also calculate how much premium consumers will pay for a brand name.

QuestionPro is a little easier to use than Qualtrics. The UI is cleaner but still clumsy. You must navigate to a different section in the builder for things like quotas instead of just having it near skip logic rules. The distribution page has the link at the top but an email body below. The reporting has a lot of different pages to click through for each option. Small things like this mean there is a learning curve to use the platform efficiently.

The biggest downside of QuestionPro is the price. All of their research questions, even Net Promoter Score, would require a custom quote under the research plan. There another plan with upgraded feature types is $1,188 annually.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | Yes | Requires a custom quote. |

| Anonymous survey link | No | You can enable a no-tracking option for email invitations. |

| Data segmentation | Yes | Includes t-tests for statistical significance. Can make segments with multiple criteria. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Skip and display logic along with answer piping. |

| Survey panels | Yes | |

| Data cleaning | Yes | Requires a custom quote. |

When it comes to advanced research projects, Sawtooth is a great resource. While their survey builder is a little limited in question types, they offer different forms of MaxDiff and conjoint. They also provide consulting services, which could help if your academic project is highly specialized.

For MaxDiff, they offer a bandit version, which can be used for MaxDiff studies with over 50 attributes. Each set of detailed attributes that are most relevant to the user. This can save panel costs because you can build a suitable statistical model with 300 bandit responses compared with 500 or 1000 standard MaxDiff responses.

Their MaxDiff feature also comes with a TURF analysis option that can show you the possible market research of various attributes.

For conjoint, they offer adaptive choice-based conjoint and menu-based conjoint. Adaptive choice tailors the product cards toward each respondent based on early responses or screening questions. Menu-based conjoint is for more complex projects, allowing respondents to build their products based on various attributes and prices.

Sawtooth has a high price point and may be out of the research for many academic projects. The lowest plan is $4,500 annually. If you need advanced tools like bandit MaxDiff or adaptive conjoint, you must pay $11,990 annually. They do have a package just for MaxDiff starting at $2,420.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | Yes | Starts at $4,500 annually. |

| Anonymous survey link | No | |

| Data segmentation | No | No statistical significance |

| Survey logic | Yes | Skip logic. No display logic, as each question is one at a time. Answer piping requires a custom script. |

| Survey panels | No | |

| Data cleaning | Yes | Available in their Lighthouse Studio for $11,990 per year. |

Conjointly is a platform geared towards research projects, namely market research. Not only do they have the standard research questions, but they also have a bunch of unique ones: claims testing, Kano Model testing, and monadic testing. There are also question types like feature placement matrix, which combines MaxDiff and Gabor Granger into a single question.

You can either use your respondents or select from a survey panel. The survey panel option comes with predefined audiences, which makes scouring respondents a breeze.

One unique feature is that they monitor in real-time speeders and other criteria for low-quality respondents. If a respondent is speeding through the survey, a warning message is displayed asking them to repeat questions before being disqualified. If a question has a lot of information to digest, the system automatically pauses, forcing the respondent to thoroughly read the question before answering.

The pricing is a little steep at $1,795 annually. Response panels for USA residents appear to start around $4 per completed response. The survey builder and reporting section could be cleaner, with different options in many places. It may take time to get up to speed.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | Yes | Cost is $1,795 annually for all question types. |

| Anonymous survey link | No | |

| Data segmentation | No | No statistical significance. But excellent layouts to compare things like MaxDiff importance between groups. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Display logic only since each page only contains one question. |

| Survey panels | Yes | Many predefined audience types make selecting criteria a breeze. |

| Data cleaning | Yes | Automatic monitoring as respondents are taking the survey. doesn’t appear to be any built-in logic for straight-lining answers. |

While Typeform doesn’t have any research questions, it is a very well-designed and easy-to-use tool that can assist with your academic survey. For example, it could gather preliminary data for a MaxDiff study.

Typeform offers a lot of integrations with other applications. For example, if your project requires exporting data to a spreadsheet, then Google Sheets or Excel integration might be helpful. Likewise, if your research project is part of a class project, then the Slack or Microsoft Teams integration might help to notify other team members when you get responses.

One unique feature of Typeform is the calculator feature. Add, subtract, and multiply numbers to the @score or @price variable. These variables can be recalled to show scores or used in a payment form.

The reporting in Typeform is basic. There is no option to create a filter or a segment report. Any data analysis would need to be done in Google Sheets or Excel.

For $29 a month, you can get 100 responses, or $59 a month, you can collect 1,000 responses each month.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | No | |

| Anonymous survey link | No | |

| Data segmentation | No | All data analysis would need to be done with the export. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Includes a flow chart to help keep track of logic jumps. |

| Survey panels | No | |

| Data cleaning | No |

HubSpot’s form builder doesn’t include advanced research questions, but it is customizable and easy to use. You can pick between multiple form types, like standalone, embedded, and pop-up forms. There are also numerous templates including lead generation, support, or eBook download forms.

One of the form builder’s main advantages is that it offers native integrations with Salesforce and HubSpot CRM tools. In addition, you can add custom properties to the form from the CRM fields. You can then send the surveys in bulk to your audience using their email features.

If you’re a large academic organization. HubSpot would be ideal to organize and manage a large distribution list. If you need advanced questions, you can still use HubSpot for an initial screener survey or incorporate other surveys into HubSpot using skip logic.

As for the downsides, scalability can be challenging. Although you can use the form builder for free, you’ll have to subscribe to one of HubSpot’s Marketing Hub paid plans to access more advanced functionalities, like unlimited automation workflows and code customization. There are steep pricing differences between paid packages.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | No | |

| Anonymous survey link | No | You can select not to collect email addresses in the survey builder. |

| Data segmentation | No | No statistical significance, but can segment form data based on numerous filters. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Skip and display logic via progressive and dependent form fields. No answer piping. |

| Survey panels | No | You can send forms to custom audiences via the platform’s CRM and email marketing tools |

| Data cleaning | No |

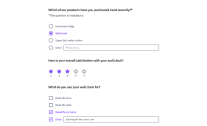

One of the widely used survey tools, Google Forms , is a decent platform for an academic research survey. Unfortunately, the software doesn’t offer any research questions. Still, the few questions it has, like multiple choice, rantings, and open-ended feedback, are enough to collect essential feedback for simple projects or preliminary data for more complex studies.

Skip logic is straightforward to set up on Google Forms. For example, you can select what section to skip based on question answers or choose what to skip once a section is complete. Of course, you can’t create complex rules, but these simple rules can cover many bases.

Overall the user interface is elegant and straightforward. The form design is also elegant, meaning the respondent experience is excellent. Unlike other survey tools, which can have a clunky interface, there is no worry about that with Google Forms; respondents can quickly navigate your form and submit answers.

The spreadsheet export is very well formatted and can be easily imported into SPSS for advanced analysis. However, the export has the submission date and time but has yet to have the time started, so calculating speeders is impossible.

| Feature | Offered | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Research questions | No | |

| Anonymous survey link | No | You can choose not to collect email addresses under settings. |

| Data segmentation | No | All data analysis would need to be done with the export. |

| Survey logic | Yes | Simple skip logic based on question answers or sections. |

| Survey panels | No | |

| Data cleaning | No |

ABOUT THE AUTOR

Allen is the founder of SurveyKing. A former CPA and government auditor, he understands how important quality data is in decision making. He continues to help SurveyKing accomplish their main goal: providing organizations around the world with low-cost high-quality feedback tools.

Ready To Start?

Create your own survey now. Get started for free and collect actionable data.

10 Great SurveyMonkey Alternatives to Use in 2024

Discover alternatives to the most popular online survey tool, SurveyMonkey. Gain an understanding of where SurveyMonkey lacks in features and get intr...

8 Best Strategies of Survey Promotion to Increase Response Rates

Survey promotion is the process of spreading surveys through different channels to encourage more responses and participation. It involves placing the...

Business Process Improvement Consulting: Expert Solutions

Definition: A business process improvement consultant will help design and implement strategies to increase the efficiency of workflows across your o...

8 Excel Consulting Services to Use in 2024 + VBA Support

These 6 Excel consulting firms offer support, training, and VBA development to help you automate tasks and increase efficiency when using Microsoft Ex...

7 Great Qualtrics Alternatives to Use in 2024

These seven alternatives to Qualtrics offer either more features, a lower cost, or a cleaner user interface. These alternative platforms also include ...

Union Negotiation Consulting: Planning Labor Agreements

A labor union negotiation consulting engagement involves quantifying member needs, proposing contract language, and developing communication strategie...

Creating a Transactional Survey: Examples + Template

Definition: A transactional survey captures customer feedback after a specific interaction, referred to as a touchpoint. This survey type provides dir...

Hire an Excel Expert: Automation + VBA Development

An Excel expert will help you to complete your projects within Microsoft Excel. A good Excel expert should be proficient in advanced formulas such as ...

Creating an Anonymous Employee Survey + Template, Sample Questions

Definition: An anonymous employee survey is a convenient way to collect honest feedback in the workplace. The survey can either measure employee satis...

Improving Fleet Performance Through Driver Feedback Surveys

In the US, the trucking industry generated $875.5 billion in gross freight revenues, accounting for 80.8% of the country’s freight invoice in 20...

13 College Study Tips to Use in 2023

These 15 college study tips will help you succeed in your academic career.

Maximizing the Value of Skills Assessment Tools Using Surveys

When you apply for a job, it’s only natural that you’ll aim to present the best possible version of yourself. You’ll focus on your best skills a...

Creating UX Surveys: 6 Tips and Examples

UX surveys are used to help create a great user experience. A good UX survey will incorporate a variety of question types to help understand what user...

5 Web Consultants to Use in 2023: Design + Development

Definition: A web consultant can update an existing website design, create a custom website, help increase traffic, recommend layout changes, and even...

Creating a Targeted Survey: Panels to Reach Your Audience

Definition: A targeted survey is used to research a specific audience, frequently utilizing a survey panel provider. A paneling service generally has ...

8 Typeform Alternatives to Use in 2023

These seven alternatives to Typeform offer a lower cost or additional features. In addition, these alternative platforms include question types that T...

7 Ecommerce Skills For Professionals + Students

Ecommerce has occupied its leading niche in the world, allowing us to draw certain conclusions. For example, it is not surprising that more specialize...

Ecommerce Analytics Explained + Tools to Use

Definition: Ecommerce analytics is the practice of continuously monitoring your business performance by gathering and examining data that affects your...

Planning a Survey: 6 Step Guide + Best Practices

Planning a survey involves six steps: Set objectives, define the target audience, select the distribution method, organize external data, draft the su...

4 Survey Consulting Services to Use in 2023

Definition: These 4 survey consulting services offer planning, design, development, and support to help complete your survey project. Whether it’s f...

Excel Automation Explained: VBA Code + Sample Workbooks

Definition: Excel automation will streamline repetitive tasks such as updating data, formatting cells, sending emails, and even uploading files to Sha...

Hire a Financial Modeling Consultant: Forecasts + Valuations

Definition: A financial modeling consultant will provide expertise in planning budgets, generating forecasts, creating valuations, and providing equit...

Excel Programming Services: Development, Macros, VBA

Definition: An excel programmer can be hired to organize workbooks, create custom formulas, automate repetitive tasks using VBA, and can consult on h...

Market Research Surveys: Sample Questions + Template

Definition: Market research surveys are a tool used to collect information about a target market. These surveys allow businesses to understand market ...

What do Americans Value Most in the Coming Election? A Comprehensive and Interactive 2020 Voter Poll

SurveyKing set out on a mission in the fall of 2020, to poll American's and help identify, with quantifiable data, what issues american are most focus...

Get Started Now

We have you covered on anything from customer surveys, employee surveys, to market research. Get started and create your first survey for free.

- Utility Menu

Harvard University Program on Survey Research

- Questionnaire Design Tip Sheet

This PSR Tip Sheet provides some basic tips about how to write good survey questions and design a good survey questionnaire.

| 40 KB |

PSR Resources

- Managing and Manipulating Survey Data: A Beginners Guide

- Finding and Hiring Survey Contractors

- How to Frame and Explain the Survey Data Used in a Thesis

- Overview of Cognitive Testing and Questionnaire Evaluation

- Sampling, Coverage, and Nonresponse Tip Sheet

- Introduction to Surveys for Honors Thesis Writers

- PSR Introduction to the Survey Process

- Related Centers/Programs at Harvard

- General Survey Reference

- Institutional Review Boards

- Select Funding Opportunities

- Survey Analysis Software

- Professional Standards

- Professional Organizations

- Major Public Polls

- Survey Data Collections

- Major Longitudinal Surveys

- Other Links

Academic survey questions, examples, and a step-by-step guide

Use SurveyPlanet for your academic research and gather real data that supports your thesis.

If you want to deepen your knowledge about a particular subject by testing theories, then academic surveys are invaluable. Coming up with a hypothesis is hard enough and a well-designed survey—with carefully constructed questions—will help you test how viable your hypothesis actually is.

The best survey tool for academic research

SurveyPlanet is a great tool for creating academic surveys that will let you put theoretical knowledge into practice and learn by doing. With dozens of templates that include pre-written questions, you will learn right away what a great academic survey should look like.

You’ll also find powerful features like question branching, survey-length estimation, four chart types to display results, and many more when you sign up for a SurveyPlanet account to create an academic survey. Our user-friendly designs will make both creating and filling out surveys a simple yet exciting experience for both you and your respondents.

A step-by-step guide to creating a successful academic survey

- First, gather your thoughts by putting them on paper in order to create a strategy for a successful academic survey.

- Set one ultimate goal, then divide this into smaller, actionable steps that will lead to achieving it.

- Consider your hypothesis and figure out how an academic survey will help you confirm it.

- Before creating questions, decide or learn who will be your target group.

- After you know your target group, think about how big your sample should be to produce statistically significant data. You can do that with our free survey sample size calculator.

- Whether you need one hundred or one thousand responses, think about where your target sample hangs out and how you’ll distribute the survey. Share a survey link with different communities on social media and reach out to friends and acquaintances. Maybe they aren’t your target group, but a friend of a friend is. Don’t get discouraged, people love to help with academic research.

- Books are one thing, real-life data is another. Think about implementing what you already know in your academic survey and how that knowledge can serve a higher purpose.

- When writing questions make sure to use different types, such as multiple choice, Likert scale, open-ended, image choice, and ranking questions. This will make your survey more engaging and fewer people will drop out because they didn't make it through to the end.

- Be brief and concise, both with questions and the survey itself. Think about whether some questions are really necessary. Write questions with straightforward language.

- Make sure your survey isn’t too long. That will put respondents off. With a survey length estimate , you don’t have to manually estimate the length, since SurveyPlanet can do that for you.

- Creating an academic survey and gathering data is great, but you also need to analyze the results. Figure out which method you’ll use before distributing the survey and analyze the quantitative data first (because it’s more straightforward).

While we can't promise that, with the help of our survey tools, you will attain academic excellence in no time, we are sure that our tools will provide a valuable service in your research endeavors. In fact, our mission is to facilitate all the stages of conducting research , from ideation to analysis. That is why we made guidelines covering every step of the process, from creating a survey to survey data analysis for better insights.

Creating your academic survey online is one of the least expensive—but effective—ways to gather all the data you need. People are more eager to respond to an online survey in their free time, from the comfort of their homes. With SurveyPlanet as your partner, you will garner a high response rate and much useful data.

Academic surveys questions and examples

The quality of questions directly influences the quality of data. At the end of the day, it’s the quality of results that matter. Because of that, we pay special attention to creating academic survey questions that are useful for both students and respondents. Academic surveys usually require some demographic questions , including:

- Please select your age range:

- 18 or younger

- Please select your gender:

- What’s your marital status?

- What’s the highest level of education you’ve completed?

- Less than high school

- High school

- Bachelor degree

- Masters degree

- Which category best describes your employment status?

- Employed full-time (40 hours a week or more)

- Employed part-time (less than 40 hours a week)

- Which category best fits the yearly household income of every member combined?

- $20,000-$59,999

- $60,000-$99,999

- $100,000-$149,999

- $150,000 or more

Academic surveys can explore and research many different topics. It just depends on what your area of interest is. Here are some academic survey examples to give you a better idea:

Healthcare surveys

With healthcare surveys, you can research patient demographics, figure out how accessible healthcare is, some common issues people encounter, and ways to improve performance.

Read more about healthcare surveys

Education surveys

Student satisfaction is a topic for which there is always more to ask and say. Using education surveys, you can explore students’ habits, assess the quality of their education, and research teachers’ working conditions.

Read more about education surveys

From employee satisfaction to work-life balance, HR surveys are an inexhaustible source for researching and studying workplace issues.

Read more about HR surveys

Brand surveys

Research consumer demographics and how they perceive different brands to draw conclusions based on the data you collect.

Read more about brand surveys

Depending on the theme that is being addressed, this type of questionnaire can be labeled as a:

- postgraduate taught experience survey

- academic performance survey

- academic research survey

Specific questions depend on the subject you’re studying and researching and we have dozens of academic survey templates to choose from.

SurveyPlanet can help you with your academic research. Use our survey tools, which can help you gather valuable data and insights in no time while providing the best experience to your examinees. Just sign up for a SurveyPlanet account and create an academic survey that will be ready for responses.

Sign up now

Free unlimited surveys, questions and responses.

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

As a staple in data collection, questionnaires help uncover robust and reliable findings that can transform industries, shape policies, and revolutionize understanding. Whether you are exploring societal trends or delving into scientific phenomena, the effectiveness of your research questionnaire can make or break your findings.

In this article, we aim to understand the core purpose of questionnaires, exploring how they serve as essential tools for gathering systematic data, both qualitative and quantitative, from diverse respondents. Read on as we explore the key elements that make up a winning questionnaire, the art of framing questions which are both compelling and rigorous, and the careful balance between simplicity and depth.

Table of Contents

The Role of Questionnaires in Research

So, what is a questionnaire? A questionnaire is a structured set of questions designed to collect information, opinions, attitudes, or behaviors from respondents. It is one of the most commonly used data collection methods in research. Moreover, questionnaires can be used in various research fields, including social sciences, market research, healthcare, education, and psychology. Their adaptability makes them suitable for investigating diverse research questions.

Questionnaire and survey are two terms often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings in the context of research. A survey refers to the broader process of data collection that may involve various methods. A survey can encompass different data collection techniques, such as interviews , focus groups, observations, and yes, questionnaires.

Pros and Cons of Using Questionnaires in Research:

While questionnaires offer numerous advantages in research, they also come with some disadvantages that researchers must be aware of and address appropriately. Careful questionnaire design, validation, and consideration of potential biases can help mitigate these disadvantages and enhance the effectiveness of using questionnaires as a data collection method.

Structured vs Unstructured Questionnaires

Structured questionnaire:.

A structured questionnaire consists of questions with predefined response options. Respondents are presented with a fixed set of choices and are required to select from those options. The questions in a structured questionnaire are designed to elicit specific and quantifiable responses. Structured questionnaires are particularly useful for collecting quantitative data and are often employed in surveys and studies where standardized and comparable data are necessary.

Advantages of Structured Questionnaires:

- Easy to analyze and interpret: The fixed response options facilitate straightforward data analysis and comparison across respondents.

- Efficient for large-scale data collection: Structured questionnaires are time-efficient, allowing researchers to collect data from a large number of respondents.

- Reduces response bias: The predefined response options minimize potential response bias and maintain consistency in data collection.

Limitations of Structured Questionnaires:

- Lack of depth: Structured questionnaires may not capture in-depth insights or nuances as respondents are limited to pre-defined response choices. Hence, they may not reveal the reasons behind respondents’ choices, limiting the understanding of their perspectives.

- Limited flexibility: The fixed response options may not cover all potential responses, therefore, potentially restricting respondents’ answers.

Unstructured Questionnaire:

An unstructured questionnaire consists of questions that allow respondents to provide detailed and unrestricted responses. Unlike structured questionnaires, there are no predefined response options, giving respondents the freedom to express their thoughts in their own words. Furthermore, unstructured questionnaires are valuable for collecting qualitative data and obtaining in-depth insights into respondents’ experiences, opinions, or feelings.

Advantages of Unstructured Questionnaires:

- Rich qualitative data: Unstructured questionnaires yield detailed and comprehensive qualitative data, providing valuable and novel insights into respondents’ perspectives.

- Flexibility in responses: Respondents have the freedom to express themselves in their own words. Hence, allowing for a wide range of responses.

Limitations of Unstructured Questionnaires:

- Time-consuming analysis: Analyzing open-ended responses can be time-consuming, since, each response requires careful reading and interpretation.

- Subjectivity in interpretation: The analysis of open-ended responses may be subjective, as researchers interpret and categorize responses based on their judgment.

- May require smaller sample size: Due to the depth of responses, researchers may need a smaller sample size for comprehensive analysis, making generalizations more challenging.

Types of Questions in a Questionnaire

In a questionnaire, researchers typically use the following most common types of questions to gather a variety of information from respondents:

1. Open-Ended Questions:

These questions allow respondents to provide detailed and unrestricted responses in their own words. Open-ended questions are valuable for gathering qualitative data and in-depth insights.

Example: What suggestions do you have for improving our product?

2. Multiple-Choice Questions

Respondents choose one answer from a list of provided options. This type of question is suitable for gathering categorical data or preferences.

Example: Which of the following social media/academic networking platforms do you use to promote your research?

- ResearchGate

- Academia.edu

3. Dichotomous Questions

Respondents choose between two options, typically “yes” or “no”, “true” or “false”, or “agree” or “disagree”.

Example: Have you ever published in open access journals before?

4. Scaling Questions

These questions, also known as rating scale questions, use a predefined scale that allows respondents to rate or rank their level of agreement, satisfaction, importance, or other subjective assessments. These scales help researchers quantify subjective data and make comparisons across respondents.

There are several types of scaling techniques used in scaling questions:

i. Likert Scale:

The Likert scale is one of the most common scaling techniques. It presents respondents with a series of statements and asks them to rate their level of agreement or disagreement using a range of options, typically from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.For example: Please indicate your level of agreement with the statement: “The content presented in the webinar was relevant and aligned with the advertised topic.”

- Strongly Agree

- Strongly Disagree

ii. Semantic Differential Scale:

The semantic differential scale measures respondents’ perceptions or attitudes towards an item using opposite adjectives or bipolar words. Respondents rate the item on a scale between the two opposites. For example:

- Easy —— Difficult

- Satisfied —— Unsatisfied

- Very likely —— Very unlikely

iii. Numerical Rating Scale:

This scale requires respondents to provide a numerical rating on a predefined scale. It can be a simple 1 to 5 or 1 to 10 scale, where higher numbers indicate higher agreement, satisfaction, or importance.

iv. Ranking Questions:

Respondents rank items in order of preference or importance. Ranking questions help identify preferences or priorities.

Example: Please rank the following features of our app in order of importance (1 = Most Important, 5 = Least Important):

- User Interface

- Functionality

- Customer Support

By using a mix of question types, researchers can gather both quantitative and qualitative data, providing a comprehensive understanding of the research topic and enabling meaningful analysis and interpretation of the results. The choice of question types depends on the research objectives , the desired depth of information, and the data analysis requirements.

Methods of Administering Questionnaires

There are several methods for administering questionnaires, and the choice of method depends on factors such as the target population, research objectives , convenience, and resources available. Here are some common methods of administering questionnaires:

Each method has its advantages and limitations. Online surveys offer convenience and a large reach, but they may be limited to individuals with internet access. Face-to-face interviews allow for in-depth responses but can be time-consuming and costly. Telephone surveys have broad reach but may be limited by declining response rates. Researchers should choose the method that best suits their research objectives, target population, and available resources to ensure successful data collection.

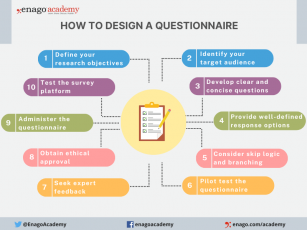

How to Design a Questionnaire

Designing a good questionnaire is crucial for gathering accurate and meaningful data that aligns with your research objectives. Here are essential steps and tips to create a well-designed questionnaire:

1. Define Your Research Objectives : Clearly outline the purpose and specific information you aim to gather through the questionnaire.

2. Identify Your Target Audience : Understand respondents’ characteristics and tailor the questionnaire accordingly.

3. Develop the Questions :

- Write Clear and Concise Questions

- Avoid Leading or Biasing Questions

- Sequence Questions Logically

- Group Related Questions

- Include Demographic Questions

4. Provide Well-defined Response Options : Offer exhaustive response choices for closed-ended questions.

5. Consider Skip Logic and Branching : Customize the questionnaire based on previous answers.

6. Pilot Test the Questionnaire : Identify and address issues through a pilot study .

7. Seek Expert Feedback : Validate the questionnaire with subject matter experts.

8. Obtain Ethical Approval : Comply with ethical guidelines , obtain consent, and ensure confidentiality before administering the questionnaire.

9. Administer the Questionnaire : Choose the right mode and provide clear instructions.

10. Test the Survey Platform : Ensure compatibility and usability for online surveys.

By following these steps and paying attention to questionnaire design principles, you can create a well-structured and effective questionnaire that gathers reliable data and helps you achieve your research objectives.

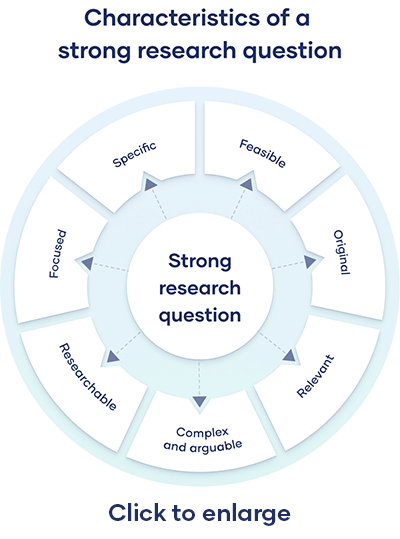

Characteristics of a Good Questionnaire

A good questionnaire possesses several essential elements that contribute to its effectiveness. Furthermore, these characteristics ensure that the questionnaire is well-designed, easy to understand, and capable of providing valuable insights. Here are some key characteristics of a good questionnaire:

1. Clarity and Simplicity : Questions should be clear, concise, and unambiguous. Avoid using complex language or technical terms that may confuse respondents. Simple and straightforward questions ensure that respondents interpret them consistently.

2. Relevance and Focus : Each question should directly relate to the research objectives and contribute to answering the research questions. Consequently, avoid including extraneous or irrelevant questions that could lead to data clutter.

3. Mix of Question Types : Utilize a mix of question types, including open-ended, Likert scale, and multiple-choice questions. This variety allows for both qualitative and quantitative data collections .

4. Validity and Reliability : Ensure the questionnaire measures what it intends to measure (validity) and produces consistent results upon repeated administration (reliability). Validation should be conducted through expert review and previous research.

5. Appropriate Length : Keep the questionnaire’s length appropriate and manageable to avoid respondent fatigue or dropouts. Long questionnaires may result in incomplete or rushed responses.

6. Clear Instructions : Include clear instructions at the beginning of the questionnaire to guide respondents on how to complete it. Explain any technical terms, formats, or concepts if necessary.

7. User-Friendly Format : Design the questionnaire to be visually appealing and user-friendly. Use consistent formatting, adequate spacing, and a logical page layout.

8. Data Validation and Cleaning : Incorporate validation checks to ensure data accuracy and reliability. Consider mechanisms to detect and correct inconsistent or missing responses during data cleaning.

By incorporating these characteristics, researchers can create a questionnaire that maximizes data quality, minimizes response bias, and provides valuable insights for their research.

In the pursuit of advancing research and gaining meaningful insights, investing time and effort into designing effective questionnaires is a crucial step. A well-designed questionnaire is more than a mere set of questions; it is a masterpiece of precision and ingenuity. Each question plays a vital role in shaping the narrative of our research, guiding us through the labyrinth of data to meaningful conclusions. Indeed, a well-designed questionnaire serves as a powerful tool for unlocking valuable insights and generating robust findings that impact society positively.

Have you ever designed a research questionnaire? Reflect on your experience and share your insights with researchers globally through Enago Academy’s Open Blogging Platform . Join our diverse community of 1000K+ researchers and authors to exchange ideas, strategies, and best practices, and together, let’s shape the future of data collection and maximize the impact of questionnaires in the ever-evolving landscape of research.

Frequently Asked Questions

A research questionnaire is a structured tool used to gather data from participants in a systematic manner. It consists of a series of carefully crafted questions designed to collect specific information related to a research study.

Questionnaires play a pivotal role in both quantitative and qualitative research, enabling researchers to collect insights, opinions, attitudes, or behaviors from respondents. This aids in hypothesis testing, understanding, and informed decision-making, ensuring consistency, efficiency, and facilitating comparisons.

Questionnaires are a versatile tool employed in various research designs to gather data efficiently and comprehensively. They find extensive use in both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, making them a fundamental component of research across disciplines. Some research designs that commonly utilize questionnaires include: a) Cross-Sectional Studies b) Longitudinal Studies c) Descriptive Research d) Correlational Studies e) Causal-Comparative Studies f) Experimental Research g) Survey Research h) Case Studies i) Exploratory Research

A survey is a comprehensive data collection method that can include various techniques like interviews and observations. A questionnaire is a specific set of structured questions within a survey designed to gather standardized responses. While a survey is a broader approach, a questionnaire is a focused tool for collecting specific data.

The choice of questionnaire type depends on the research objectives, the type of data required, and the preferences of respondents. Some common types include: • Structured Questionnaires: These questionnaires consist of predefined, closed-ended questions with fixed response options. They are easy to analyze and suitable for quantitative research. • Semi-Structured Questionnaires: These questionnaires combine closed-ended questions with open-ended ones. They offer more flexibility for respondents to provide detailed explanations. • Unstructured Questionnaires: These questionnaires contain open-ended questions only, allowing respondents to express their thoughts and opinions freely. They are commonly used in qualitative research.

Following these steps ensures effective questionnaire administration for reliable data collection: • Choose a Method: Decide on online, face-to-face, mail, or phone administration. • Online Surveys: Use platforms like SurveyMonkey • Pilot Test: Test on a small group before full deployment • Clear Instructions: Provide concise guidelines • Follow-Up: Send reminders if needed

Thank you, Riya. This is quite helpful. As discussed, response bias is one of the disadvantages in the use of questionnaires. One way to help limit this can be to use scenario based questions. These type of questions may help the respondents to be more reflective and active in the process.

Thank you, Dear Riya. This is quite helpful.

Great insights there Doc

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![academic research questionnaire What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What would be most effective in reducing research misconduct?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.6(2); Mar-Apr 2015

Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research

A variety of methodologic approaches exist for individuals interested in conducting research. Selection of a research approach depends on a number of factors, including the purpose of the research, the type of research questions to be answered, and the availability of resources. The purpose of this article is to describe survey research as one approach to the conduct of research so that the reader can critically evaluate the appropriateness of the conclusions from studies employing survey research.

SURVEY RESEARCH

Survey research is defined as "the collection of information from a sample of individuals through their responses to questions" ( Check & Schutt, 2012, p. 160 ). This type of research allows for a variety of methods to recruit participants, collect data, and utilize various methods of instrumentation. Survey research can use quantitative research strategies (e.g., using questionnaires with numerically rated items), qualitative research strategies (e.g., using open-ended questions), or both strategies (i.e., mixed methods). As it is often used to describe and explore human behavior, surveys are therefore frequently used in social and psychological research ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ).

Information has been obtained from individuals and groups through the use of survey research for decades. It can range from asking a few targeted questions of individuals on a street corner to obtain information related to behaviors and preferences, to a more rigorous study using multiple valid and reliable instruments. Common examples of less rigorous surveys include marketing or political surveys of consumer patterns and public opinion polls.

Survey research has historically included large population-based data collection. The primary purpose of this type of survey research was to obtain information describing characteristics of a large sample of individuals of interest relatively quickly. Large census surveys obtaining information reflecting demographic and personal characteristics and consumer feedback surveys are prime examples. These surveys were often provided through the mail and were intended to describe demographic characteristics of individuals or obtain opinions on which to base programs or products for a population or group.

More recently, survey research has developed into a rigorous approach to research, with scientifically tested strategies detailing who to include (representative sample), what and how to distribute (survey method), and when to initiate the survey and follow up with nonresponders (reducing nonresponse error), in order to ensure a high-quality research process and outcome. Currently, the term "survey" can reflect a range of research aims, sampling and recruitment strategies, data collection instruments, and methods of survey administration.

Given this range of options in the conduct of survey research, it is imperative for the consumer/reader of survey research to understand the potential for bias in survey research as well as the tested techniques for reducing bias, in order to draw appropriate conclusions about the information reported in this manner. Common types of error in research, along with the sources of error and strategies for reducing error as described throughout this article, are summarized in the Table .

Sources of Error in Survey Research and Strategies to Reduce Error

The goal of sampling strategies in survey research is to obtain a sufficient sample that is representative of the population of interest. It is often not feasible to collect data from an entire population of interest (e.g., all individuals with lung cancer); therefore, a subset of the population or sample is used to estimate the population responses (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment). A large random sample increases the likelihood that the responses from the sample will accurately reflect the entire population. In order to accurately draw conclusions about the population, the sample must include individuals with characteristics similar to the population.

It is therefore necessary to correctly identify the population of interest (e.g., individuals with lung cancer currently receiving treatment vs. all individuals with lung cancer). The sample will ideally include individuals who reflect the intended population in terms of all characteristics of the population (e.g., sex, socioeconomic characteristics, symptom experience) and contain a similar distribution of individuals with those characteristics. As discussed by Mady Stovall beginning on page 162, Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ), for example, were interested in the population of oncologists. The authors obtained a sample of oncologists from two hospitals in Japan. These participants may or may not have similar characteristics to all oncologists in Japan.

Participant recruitment strategies can affect the adequacy and representativeness of the sample obtained. Using diverse recruitment strategies can help improve the size of the sample and help ensure adequate coverage of the intended population. For example, if a survey researcher intends to obtain a sample of individuals with breast cancer representative of all individuals with breast cancer in the United States, the researcher would want to use recruitment strategies that would recruit both women and men, individuals from rural and urban settings, individuals receiving and not receiving active treatment, and so on. Because of the difficulty in obtaining samples representative of a large population, researchers may focus the population of interest to a subset of individuals (e.g., women with stage III or IV breast cancer). Large census surveys require extremely large samples to adequately represent the characteristics of the population because they are intended to represent the entire population.

DATA COLLECTION METHODS

Survey research may use a variety of data collection methods with the most common being questionnaires and interviews. Questionnaires may be self-administered or administered by a professional, may be administered individually or in a group, and typically include a series of items reflecting the research aims. Questionnaires may include demographic questions in addition to valid and reliable research instruments ( Costanzo, Stawski, Ryff, Coe, & Almeida, 2012 ; DuBenske et al., 2014 ; Ponto, Ellington, Mellon, & Beck, 2010 ). It is helpful to the reader when authors describe the contents of the survey questionnaire so that the reader can interpret and evaluate the potential for errors of validity (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure what they are intended to measure) and reliability (e.g., items or instruments that do not measure a construct consistently). Helpful examples of articles that describe the survey instruments exist in the literature ( Buerhaus et al., 2012 ).

Questionnaires may be in paper form and mailed to participants, delivered in an electronic format via email or an Internet-based program such as SurveyMonkey, or a combination of both, giving the participant the option to choose which method is preferred ( Ponto et al., 2010 ). Using a combination of methods of survey administration can help to ensure better sample coverage (i.e., all individuals in the population having a chance of inclusion in the sample) therefore reducing coverage error ( Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, if a researcher were to only use an Internet-delivered questionnaire, individuals without access to a computer would be excluded from participation. Self-administered mailed, group, or Internet-based questionnaires are relatively low cost and practical for a large sample ( Check & Schutt, 2012 ).

Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) have described and tested a tailored design method for survey research. Improving the visual appeal and graphics of surveys by using a font size appropriate for the respondents, ordering items logically without creating unintended response bias, and arranging items clearly on each page can increase the response rate to electronic questionnaires. Attending to these and other issues in electronic questionnaires can help reduce measurement error (i.e., lack of validity or reliability) and help ensure a better response rate.

Conducting interviews is another approach to data collection used in survey research. Interviews may be conducted by phone, computer, or in person and have the benefit of visually identifying the nonverbal response(s) of the interviewee and subsequently being able to clarify the intended question. An interviewer can use probing comments to obtain more information about a question or topic and can request clarification of an unclear response ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Interviews can be costly and time intensive, and therefore are relatively impractical for large samples.

Some authors advocate for using mixed methods for survey research when no one method is adequate to address the planned research aims, to reduce the potential for measurement and non-response error, and to better tailor the study methods to the intended sample ( Dillman et al., 2014 ; Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). For example, a mixed methods survey research approach may begin with distributing a questionnaire and following up with telephone interviews to clarify unclear survey responses ( Singleton & Straits, 2009 ). Mixed methods might also be used when visual or auditory deficits preclude an individual from completing a questionnaire or participating in an interview.

FUJIMORI ET AL.: SURVEY RESEARCH

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) described the use of survey research in a study of the effect of communication skills training for oncologists on oncologist and patient outcomes (e.g., oncologist’s performance and confidence and patient’s distress, satisfaction, and trust). A sample of 30 oncologists from two hospitals was obtained and though the authors provided a power analysis concluding an adequate number of oncologist participants to detect differences between baseline and follow-up scores, the conclusions of the study may not be generalizable to a broader population of oncologists. Oncologists were randomized to either an intervention group (i.e., communication skills training) or a control group (i.e., no training).

Fujimori et al. ( 2014 ) chose a quantitative approach to collect data from oncologist and patient participants regarding the study outcome variables. Self-report numeric ratings were used to measure oncologist confidence and patient distress, satisfaction, and trust. Oncologist confidence was measured using two instruments each using 10-point Likert rating scales. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure patient distress and has demonstrated validity and reliability in a number of populations including individuals with cancer ( Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, 2002 ). Patient satisfaction and trust were measured using 0 to 10 numeric rating scales. Numeric observer ratings were used to measure oncologist performance of communication skills based on a videotaped interaction with a standardized patient. Participants completed the same questionnaires at baseline and follow-up.

The authors clearly describe what data were collected from all participants. Providing additional information about the manner in which questionnaires were distributed (i.e., electronic, mail), the setting in which data were collected (e.g., home, clinic), and the design of the survey instruments (e.g., visual appeal, format, content, arrangement of items) would assist the reader in drawing conclusions about the potential for measurement and nonresponse error. The authors describe conducting a follow-up phone call or mail inquiry for nonresponders, using the Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) tailored design for survey research follow-up may have reduced nonresponse error.

CONCLUSIONS

Survey research is a useful and legitimate approach to research that has clear benefits in helping to describe and explore variables and constructs of interest. Survey research, like all research, has the potential for a variety of sources of error, but several strategies exist to reduce the potential for error. Advanced practitioners aware of the potential sources of error and strategies to improve survey research can better determine how and whether the conclusions from a survey research study apply to practice.

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Help Center

- اَلْعَرَبِيَّةُ

- Deutsch (Schweiz)

- Español (Mexico)

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- Português (Brasil)

- Tiếng việt

Academic surveys

using expertly-crafted questionnaires and forms to gather reliable data that informs critical decisions for success and growth. Get valuable insights from stakeholders and achieve your objectives while advancing your mission with our powerful academic survey tools.

Unlimited answers

80+ languages, 28+ question types, academic surveys templates.

Student evaluation form template

Course evaluation template

School survey template

Course evaluation form template

Course feedback template

Library registration form template

Student satisfaction survey template

How to create effective academic surveys, tpl_module_accordion_title, 1. define your research question.

Define your research question and objectives before creating the survey questions.

2. MUse clear and concise language

Use clear and concise language, avoiding technical jargon or complicated vocabulary.

3. Make sure the survey questions

Make sure the survey questions are relevant and important to the academic context and the research question.

4. Use different types of questions

Use different types of questions (e.g. multiple choice, Likert scale, open-ended) to gather different types of data.

5. Test the survey with a small sample group

Test the survey with a small sample group before distributing it widely to ensure clarity and effectiveness.

6. Consider the length of the survey

Consider the length of the survey and make sure it is not too long, as this can reduce response rates and increase the likelihood of incomplete responses.

7. Use branching logic to tailor questions

Use branching logic to tailor questions to the respondent's previous answers and ensure that all respondents receive relevant questions.

8. Include demographic questions

Include demographic questions at the end of the survey to gather useful data about the respondents.

9. Use a variety of distribution methods

Use a variety of distribution methods (e.g. email, social media, online forums) to reach a wide audience.

10. Consider offering incentives

Consider offering incentives (e.g. gift cards, free access to research results) to increase response rates and improve the quality of responses.

Academic Survey Builder

Create effective academic surveys easily and efficiently with LimeSurvey's Academic Survey Builder, the user-friendly creator and generator that allows you to gather reliable data and make informed decisions for your academic institution.

- Custom number of responses/year

- Custom upload storage

- Corporate support

- Custom number of alias domains

- Dedicated server

- So much more…

Related templates

Event feedback form template

RSVP form template

Event planning questionnaire template

Conference registration form template

School climate survey template

Similar categories, best academic surveys questionnaires and feedback forms.

Student feedback form template

Parent survey template

Limesurvey is trusted by the world's most curious minds:.

Open Source

Just one more step to your free trial.

.surveysparrow.com

Already using SurveySparrow? Login

By clicking on "Get Started", I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Enterprise Survey Software

Enterprise Survey Software to thrive in your business ecosystem

NPS® Software

Turn customers into promoters

Offline Survey

Real-time data collection, on the move. Go internet-independent.

360 Assessment

Conduct omnidirectional employee assessments. Increase productivity, grow together.

Reputation Management

Turn your existing customers into raving promoters by monitoring online reviews.

Ticket Management

Build loyalty and advocacy by delivering personalized support experiences that matter.

Chatbot for Website

Collect feedback smartly from your website visitors with the engaging Chatbot for website.

Swift, easy, secure. Scalable for your organization.

Executive Dashboard