Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 14: The Research Proposal

14.3 Components of a Research Proposal

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections – Introductions, Background and significance, Literature Review; Research design and methods, Preliminary suppositions and implications; and Conclusion present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- understand what it is you want to do;

- have a sense of your passion for the topic; and

- be excited about the study’s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal, it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important? Whom are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5 to 7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. Since key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature review

This key component of the research proposal is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter 5 describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research.

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as you collect and/or analyze the data; in this case, it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of this textbook’s authors’ research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally, if not more, important to consider what methods have not been but could be employed. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section:

Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

Specify the research operations you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually implement the methods (i.e., coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research, and describe how you will address these barriers.

Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary suppositions and implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, theoretical understanding, or method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what might benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic or environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.

The conclusion reiterates the importance and significance of your research proposal, and provides a brief summary of the entire proposed study. Essentially, this section should only be one or two paragraphs in length. Here is a potential outline for your conclusion:

Discuss why the study should be done. Specifically discuss how you expect your study will advance existing knowledge and how your study is unique.

Explain the specific purpose of the study and the research questions that the study will answer.

Explain why the research design and methods chosen for this study are appropriate, and why other designs and methods were not chosen.

State the potential implications you expect to emerge from your proposed study,

Provide a sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship currently in existence, related to the research problem.

Citations and references

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your research proposal. In a research proposal, this can take two forms: a reference list or a bibliography. A reference list lists the literature you referenced in the body of your research proposal. All references in the reference list must appear in the body of the research proposal. Remember, it is not acceptable to say “as cited in …” As a researcher you must always go to the original source and check it for yourself. Many errors are made in referencing, even by top researchers, and so it is important not to perpetuate an error made by someone else. While this can be time consuming, it is the proper way to undertake a literature review.

In contrast, a bibliography , is a list of everything you used or cited in your research proposal, with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem. In other words, sources cited in your bibliography may not necessarily appear in the body of your research proposal. Make sure you check with your instructor to see which of the two you are expected to produce.

Overall, your list of citations should be a testament to the fact that you have done a sufficient level of preliminary research to ensure that your project will complement, but not duplicate, previous research efforts. For social sciences, the reference list or bibliography should be prepared in American Psychological Association (APA) referencing format. Usually, the reference list (or bibliography) is not included in the word count of the research proposal. Again, make sure you check with your instructor to confirm.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

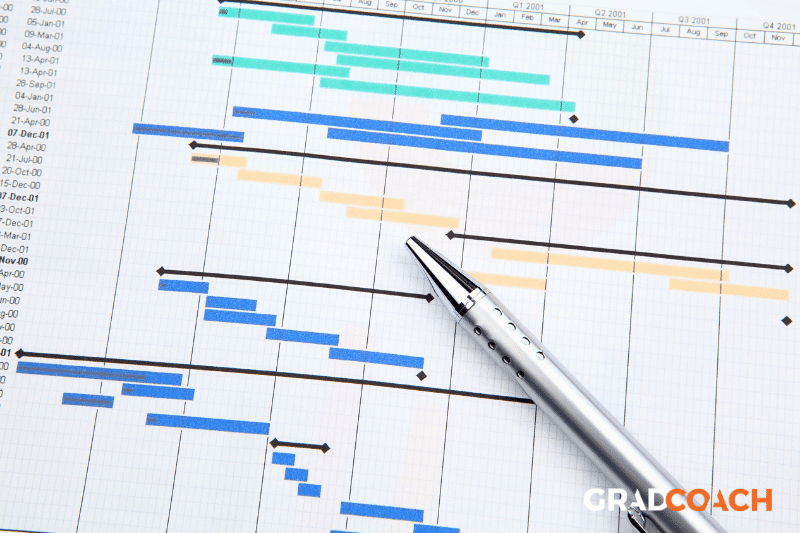

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Thank you very much, this is very insightful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Write a Research Proposal

Structure and content, introduction (to topic and problem), research question (or hypothesis, thesis statement, aim), proposed methodology, anticipated findings, contributions - impact and significance, tables and figures (if applicable).

- Questions for Editing and Revisions

Ask Us: Chat, email, visit or call

Video: Cite Your Sources: APA in-text citation

Get assistance

The library offers a range of helpful services. All of our appointments are free of charge and confidential.

- Book an appointment

The structure and content of a research proposal can vary depending upon the discipline, purpose, and target audience. For example, a graduate thesis proposal and a Tri-Council grant proposal will have different guidelines for length and required sections.

Before you begin writing, be sure to talk with your supervisor to gain a clear understanding of their specific expectations, and continually check in with them throughout the writing process.

- Organizing your Research Proposal - Template This 6-page fillable pdf handout provides writers with a template to begin outlining sections of their own research proposal.

This template can be used in conjunction with the sections below.

What are some keywords for your research?

- Should give a clear indication of your proposed research approach or key question

- Should be concise and descriptive

Writing Tip: When constructing your title, think about the search terms you would use to find this research online.

Important: Write this section last, after you have completed drafting the proposal. Or if you are required to draft a preliminary abstract, then remember to rewrite the abstract after you have completed drafting the entire proposal because some information may need to be revised.

The abstract should provide a brief overview of the entire proposal. Briefly state the research question (or hypothesis, thesis statement, aim), the problem and rationale, the proposed methods, and the proposed analyses or expected results.

The purpose of the introduction is to communicate the information that is essential for the reader to understand the overall area of concern. Be explicit. Outline why this research must be conducted and try to do so without unnecessary jargon or overwhelming detail.

Start with a short statement that establishes the overall area of concern. Avoid too much detail. Get to the point. Communicate only information essential for the reader’s comprehension. Avoid unnecessary technical language and jargon. Answer the question, "What is this study about?"

Questions to consider:

- What is your topic area, and what is the problem within that topic?

- What does the relevant literature say about the problem? – Be selective and focused.

- What are the critical, theoretical, or methodological issues directly related to the problem to be investigated?

- What are the reasons for undertaking the research? – This is the answer to the "so what?" question.

The following sections - listed as part of the introduction - are intended as a guide for drafting a research proposal. Most introductions include these following components. However, be sure to clarify with your advisor or carefully review the grant guidelines to be sure to comply with the proposal genre expectations of your specific discipline.

Broad topic and focus of study

- Briefly describe the broad topic of your research area, and then clearly explain the narrowed focus of your specific study.

Importance of topic/field of study

- Position your project in a current important research area.

- Address the “So what?” question directly, and as soon as possible.

- Provide context for the reader to understand the problem you are about to pose or research question you are asking.

Problem within field of study

- Identify the problem that you are investigating in your study.

Gap(s) in knowledge

- Identify something missing from the literature.

- What is unknown in this specific research area? This is what your study will explore and where you will attempt to provide new insights.

- Is there a reason this gap exists? Where does the current literature agree and where does it disagree? How you fill this gap (at least partially) with your research?

- Convince your reader that the problem has been appropriately defined and that the study is worth doing. Be explicit and detailed.

- Develop your argument logically and provide evidence.

- Explain why you are the person to do this project. Summarize any previous work or studies you may have undertaken in this field or research area.

Research question or hypothesis

- Foreshadow outcomes of your research. What is the question you are hoping to answer? What are the specific hypotheses to be tested and/or issues to be explored?

- Use questions when research is exploratory.

- Use declarative statements when existing knowledge enables predictions.

- List any secondary or subsidiary questions if applicable.

Purpose statement

- State the purpose of your research. Be succinct and simple.

- Why do you want to do this study?

- What is your research trying to find out?

Goals for proposed research

- Write a brief, broad statement of what you hope to accomplish and why (e.g., Improve something… Understand something… ). Are there specific measurable outcomes that you will accomplish in your study?

- You will have a chance to go into greater detail in the research question and methodology sections.

Background or context (or literature review)

- What does the existing research on this topic say?

- Briefly state what you already know and introduce literature most relevant to your research.

- Indicate main research findings, methodologies, and interpretations from previous related studies.

- Discuss how your question or hypothesis relates to what is already known.

- Position your research within the field’s developing body of knowledge.

- Explain and support your choice of methodology or theoretical framework.

The research question is the question you are hoping to answer in your research project. It is important to know how you should write your research question into your proposal. Some proposals include

- a research question, written as a question

- or, a hypothesis as a potential response to the research question

- or, a thesis statement as an argument that answers the research question

- or, aims and objects as accomplishment or operational statements

Foreshadow the outcomes of your research. Are you trying to improve something? Understand something? Advocate for a social responsibility?

Research question

What is the question you are hoping to answer?

Subsidiary questions (if applicable)

- Does your major research question hinge on a few smaller questions? Which will you address first?

Your hypothesis should provide one (of many) possible answers to your research question.

- What are the specific hypotheses to be tested and/or issues to be explored?

- What results do you anticipate for this experiment?

Usually a hypothesis is written to show the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Your hypothesis must be

- An expected relationship between variables

- Falsifiable

- Consistent with the existing body of knowledge

Thesis statement

Your thesis statement is a clear, concise statement of what you are arguing and why it is important. For more support on writing thesis statements, check out these following resources:

- 5 Types of Thesis Statements - Learn about five different types of thesis statements to help you choose the best type for your research.

- Templates for Writing Thesis Statements - This template provides a two-step guide for writing thesis statements.

- 5 Questions to Strengthen Your Thesis Statement - Follow these five steps to strengthen your thesis statements.

Aims and objectives

Aims are typically broader statements of what you are trying to accomplish and may or may not be measurable. Objectives are operational statements indicating specifically how you will accomplish the aims of your project.

- What are you trying to accomplish?

- How are you going to address the research question?

Be specific and make sure your aims or objectives are realistic. You want to convey that it is feasible to answer this question with the objectives you have proposed.

Make it clear that you know what you are going to do, how you are going to do it, and why it will work by relating your methodology to previous research. If there isn’t much literature on the topic, you can relate your methodology to your own preliminary research or point out how your methodology tackles something that may have been overlooked in previous studies.

Explain how you will conduct this research. Specify scope and parameters (e.g., geographic locations, demographics). Limit your inclusion of literature to only essential articles and studies.

- How will these methods produce an answer to your research question?

- How do the methods relate to the introduction and literature review?

- Have you done any previous work (or read any literature) that would inform your choices about methodology?

- Are your methods feasible and adequate? How do you know?

- What obstacles might you encounter in conducting the research, and how will you overcome them?

This section should include the following components that are relevant to your study and research methodologies:

Object(s) of study / participants / population

Provide detail about your objects of study (e.g., literary texts, swine, government policies, children, health care systems).

- Who/what are they?

- How will you find, select, or collect them?

- How feasible is it to find/select them?

- Are there any limitations to sample/data collection?

- Do you need to travel to collect samples or visit archives, etc.?

- Do you need to obtain Research Ethics Board (REB) approval to include human participants?

Theoretical frame or critical methodology

- Explain the theories or disciplinary methodologies that your research draws from or builds upon.

Materials and apparatus

- What are your survey or interview methods? (You may include a copy of questionnaires, etc.)

- Do you require any special equipment?

- How do you plan to purchase or construct or obtain this equipment?

Procedure and design

What exactly will you do? Include variables selected or manipulated, randomization, controls, the definition of coding categories, etc.

- Is it a questionnaire? Laboratory experiment? Series of interviews? Systematic review? Interpretative analysis?

- How will subjects be assigned to experimental conditions?

- What precautions will be used to control possible confounding variables?

- How long do you expect to spend on each step, and do you have a backup plan?

Data analysis and statistical procedures

- How do you plan to statistically analyze your data?

- What analyses will you conduct?

- How will the analyses contribute to the objectives?

What are the expected outcomes from your methods? Describe your expected results in relation to your hypothesis. Support these results using existing literature.

- What results would prove or disprove your hypotheses and validate your methodology, and why?

- What obstacles might you encounter in obtaining your results, and how will you deal with those obstacles?

- How will you analyze and interpret your results?

This section may be the most important part of your proposal. Make sure to emphasize how this research is significant to the related field, and how it will impact the broader community, now and in the future.

Convince your reader why this project should be funded above the other potential projects. Why is this research useful and relevant? Why is it useful to others? Answer the question “so what?”

Specific contributions

- How will your anticipated results specifically contribute to fulfilling the aims, objectives, or goals of your research?

- Will these be direct or indirect contributions? – theoretical or applied?

- How will your research contribute to the larger topic area or research discipline?

Impact and significance

- How will your research contribute to the research field of study?

- How will your research contribute to the larger topic addressed in your introduction?

- How will this research extend other work that you have done?

- How will this contribution/significance convince the reader that this research will be useful and relevant?

- Who else might find your research useful and relevant? (e.g., other research streams, policy makers, professional fields, etc.)

Provide a list of some of the most important sources that you will need to use for the introduction and background sections, plus your literature review and theoretical framework.

What are some of the most important sources that you will need to use for the intro/background/lit review/theoretical framework?

- Find out what style guide you are required to follow (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

- Follow the guidelines in our Cite Your Sources Libguide to format citations and create a reference list or bibliography.

Attach this list to your proposal as a separate page unless otherwise specified.

This section should include only visuals that help illustrate the preliminary results, methods, or expected results.

- What visuals will you use to help illustrate the methods or expected results?

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Questions for Editing and Revisions >>

- Last Updated: Jun 19, 2023 11:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/ResearchProposal

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Writing a Research Proposal

Parts of a research proposal, prosana model, introduction, research question, methodology.

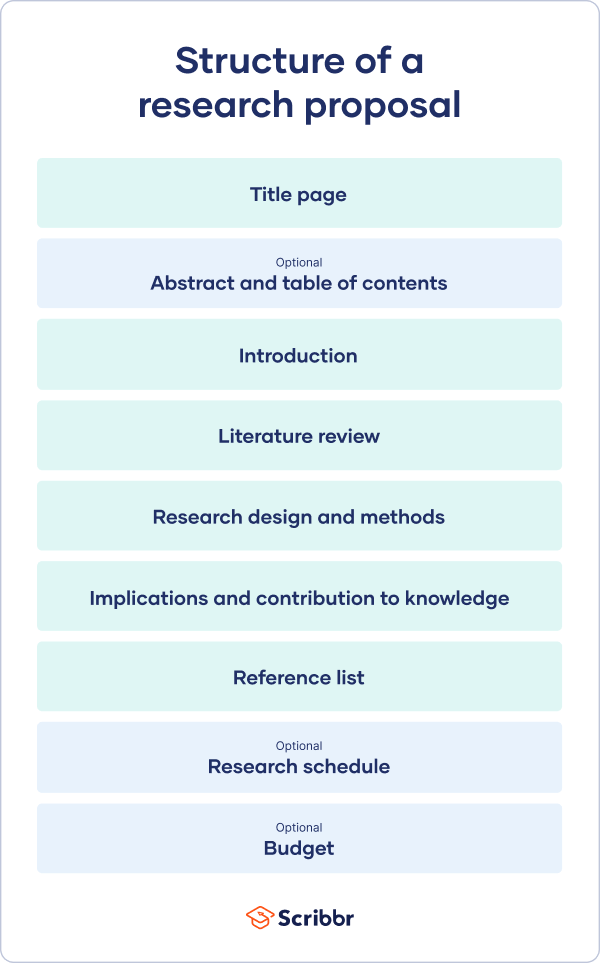

- Structure of a Research Proposal

- Common Proposal Writing Mistakes

- Proposal Writing Resources

A research proposal's purpose is to capture the evaluator's attention, demonstrate the study's potential benefits, and prove that it is a logical and consistent approach (Van Ekelenburg, 2010). To ensure that your research proposal contains these elements, there are several aspects to include in your proposal (Al-Riyami, 2008):

- Objective(s)

- Variables (independent and dependent)

- Research Question and/or hypothesis

Details about what to include in each element are included in the boxes below. Depending on the topic of your study, some parts may not apply to your proposal. You can also watch the video below for a brief overview about writing a successful research proposal.

Van Ekelenburg (2010) uses the PROSANA Model to guide researchers in developing rationale and justification for their research projects. It is an acronym that connects the problem, solution, and benefits of a particular research project. It is an easy way to remember the critical parts of a research proposal and how they relate to one another. It includes the following letters (Van Ekelenburg, 2010):

- Problem: Describing the main problem that the researcher is trying to solve.

- Root causes: Describing what is causing the problem. Why is the topic an issue?

- fOcus: Narrowing down one of the underlying causes on which the researcher will focus for their research project.

- Solutions: Listing potential solutions or approaches to fix to the problem. There could be more than one.

- Approach: Selecting the solution that the researcher will want to focus on.

- Novelty: Describing how the solution will address or solve the problem.

- Arguments: Explaining how the proposed solution will benefit the problem.

Research proposal titles should be concise and to the point, but informative. The title of your proposal may be different from the title of your final research project, but that is completely normal! Your findings may help you come up with a title that is more fitting for the final project. Characteristics of good proposal titles are (Al-Riyami, 2008):

- Catchy: It catches the reader's attention by peaking their interest.

- Positive: It spins your project in a positive way towards the reader.

- Transparent: It identifies the independent and dependent variables.

It is also common for proposal titles to be very similar to your research question, hypothesis, or thesis statement (Locke et al., 2007).

An abstract is a brief summary (about 300 words) of the study you are proposing. It includes the following elements (Al-Riyami, 2008):

- Your primary research question(s).

- Hypothesis or main argument.

- Method you will use to complete the study. This may include the design, sample population, or measuring instruments that you plan to use.

Our guide on writing summaries may help you with this step.

- Writing a Summary by Luann Edwards Last Updated May 22, 2023 1119 views this year

The purpose of the introduction is to give readers background information about your topic. it gives the readers a basic understanding of your topic so that they can further understand the significance of your proposal. A good introduction will explain (Al-Riyami, 2008):

- How it relates to other research done on the topic

- Why your research is significant to the field

- The relevance of your study

Your research objectives are the desired outcomes that you will achieve from the research project. Depending on your research design, these may be generic or very specific. You may also have more than one objective (Al-Riyami, 2008).

- General objectives are what the research project will accomplish

- Specific objectives relate to the research questions that the researcher aims to answer through the study.

Be careful not to have too many objectives in your proposal, as having too many can make your project lose focus. Plus, it may not be possible to achieve several objectives in one study.

This section describes the different types of variables that you plan to have in your study and how you will measure them. According to Al-Riyami (2008), there are four types of research variables:

- Independent: The person, object, or idea that is manipulated by the researcher.

- Dependent: The person, object, or idea whose changes are dependent upon the independent variable. Typically, it is the item that the researcher is measuring for the study.

- Confounding/Intervening: Factors that may influence the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. These include physical and mental barriers. Not every study will have intervening variables, but they should be studied if applicable.

- Background: Factors that are relevant to the study's data and how it can be generalized. Examples include demographic information such as age, sex, and ethnicity.

Your research proposal should describe each of your variables and how they relate to one another. Depending on your study, you may not have all four types of variables present. However, there will always be an independent and dependent variable.

A research question is the main piece of your research project because it explains what your study will discover to the reader. It is the question that fuels the study, so it is important for it to be precise and unique. You do not want it to be too broad, and it should identify a relationship between two variables (an independent and a dependent) (Al-Riyami, 2008). There are six types of research questions (Academic Writer, n.d.):

- Example: "Do people get nervous before speaking in front of an audience?"

- Example: "What are the study habits of college freshmen at Tiffin University?"

- Example: "What primary traits create a successful romantic relationship?"

- Example: "Is there a relationship between a child's performance in school and their parents' socioeconomic status?"

- Example: "Are high school seniors more motivated than high school freshmen?"

- Example: "Do news media outlets impact a person's political opinions?"

For more information on the different types of research questions, you can view the "Research Questions and Hypotheses" tutorial on Academic Writer, located below. If you are unfamiliar with Academic Writer, we also have a tutorial on using the database located below.

Compose papers in pre-formatted APA templates. Manage references in forms that help craft APA citations. Learn the rules of APA style through tutorials and practice quizzes.

Academic Writer will continue to use the 6th edition guidelines until August 2020. A preview of the 7th edition is available in the footer of the resource's site. Previously known as APA Style Central.

- Academic Writer Tutorial by Pfeiffer Library Last Updated May 22, 2023 15600 views this year