| You might be using an unsupported or outdated browser. To get the best possible experience please use the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Microsoft Edge to view this website. |

What Is the Efficient Market Hypothesis?

Updated: May 11, 2022, 1:05pm

The efficient market hypothesis argues that current stock prices reflect all existing available information, making them fairly valued as they are presently. Given these assumptions, outperforming the market by stock picking or market timing is highly unlikely, unless you are an outlier who is either very lucky or very unlucky.

Understanding the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The most important assumption underlying the efficient market hypothesis is that all information relevant to stock prices is freely available and shared with all market participants.

Given the vast numbers of buyers and sellers in the market, information and data is incorporated quickly, and price movements reflect this. As a result, the theory argues that stocks always trade at their fair market value.

Followers of the efficient market hypothesis believe that if stocks always trade at their fair market value, then no level of analysis or market timing strategy will yield opportunities for outperformance.

In other words, an investor following the efficient market hypothesis shouldn’t buy undervalued stocks at bargain basement prices expecting to see large gains in the future, nor would they benefit from selling overvalued stocks.

The efficient market hypothesis begins with Eugene Fama, a University of Chicago professor and Nobel Prize winner who is regarded as the father of modern finance. In 1970, Fama published “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work,” which outlined his vision of the theory.

Three Variations Of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Investors who strongly believe in the efficient market hypothesis choose passive investment strategies that mirror benchmark performance, but they may do so to varying degrees. There are three main variations on the theory:

1. The Weak Form of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Although investors abiding by the efficient market hypothesis believe that security prices reflect all available public market information, those following the weak form of the hypothesis assume that prices might not reflect new information that hasn’t yet been made available to the public.

It also assumes that past prices do not influence future prices, which will instead be informed by new information. If this is the case, then technical analysis is a fruitless endeavor.

The weak form of the efficient market hypothesis leaves room for a talented fundamental analyst to pick stocks that outperform in the short-term, based on their ability to predict what new information might influence prices.

2. The Semi-Strong Form of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

This form takes the same assertions of weak form, and includes the assumption that all new public information is instantly priced into the market. In this way, neither fundamental nor technical analysis can be used to generate excess returns.

3. The Strong Form of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Strong form efficient market hypothesis followers believe that all information, both public and private, is incorporated into a security’s current price. In this way, not even insider information can give investors an opportunity for excess returns.

Arguments For and Against the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Investors who follow the efficient market hypothesis tend to stick with passive investing options, like index funds and exchange-traded funds ( ETFs ) that track benchmark indexes, for the reasons listed above.

Given the variety of investing strategies people deploy, it’s clear that not everyone believes the efficient market hypothesis to be a solid blueprint for smart investing. In fact, the investment market is teeming with mutual funds and other funds that employ active management with the goal of outperforming a benchmark index.

The Case for Active Investing

Active portfolio managers believe that they can leverage their individual skill and experience—often augmented by a team of skilled equity analysts—to exploit market inefficiencies and to generate a return that exceeds the benchmark return.

There is evidence to support both sides of the argument. The Morningstar Active vs Passive Barometer is a twice-yearly report that measures the performance of active managers against their passive peers. Nearly 3,500 funds were included in the 2020 analysis, which found that only 49% of actively managed funds outperformed their passive counterparts for the year.

On the other hand, looking at the 10-year period ending December 31, 2020 shows a different picture, since the percentage of active managers who outperformed comparable passive strategies dropped to 23%.

Are Some Markets Less Efficient than Others?

A deeper look into the Morningstar report shows that the success of active or passive management varies considerably according to the type of fund.

For example, active managers of U.S. real estate funds outperformed passively managed vehicles 62.5% of the time, but the figure drops to 25% when fees are considered.

Other areas where active management tends to outperform passive—before fees—include high yield bond funds at 59.5% and diversified emerging market funds at 58.3%. The addition of fees for portfolios that are actively managed tends to drag on their overall performance in most cases.

In other asset classes, passive managers significantly outperformed active managers. U.S. large-cap blend saw active managers outperform passive only 17.2% of the time, with the percentage dropping to 4.1% after fees.

These results seem to suggest that some markets are less efficient than others. Liquidity in emerging markets can be limited, for example, as can transparency. Political and economic uncertainty are more prevalent, and legal complexities and lack of investor protections can also cause problems.

These factors combine to create considerable inefficiencies, which a knowledgeable portfolio manager can exploit.

On the other hand, U.S. markets for large-cap or mid-cap stocks are heavily traded, and information is rapidly incorporated into stock prices. Efficiency is high and, as demonstrated by the Morningstar results, active managers have much less of an edge.

How Star Managers Handle Their Portfolios

Popular investment manager Warren Buffet is one successful example of an active investor. Buffet is a disciple of Benjamin Graham, the father of fundamental analysis, and has been a value investor throughout his career. Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate that holds his investments, has earned an annual return of 20% over the past 52 years, often outperforming the S&P 500 .

Another successful public investor, Peter Lynch, managed Fidelity’s Magellan Fund from 1977 to 1990. With his active investment ideology at the helm, the fund returned an average 29% annually and, over the 13-year period, Lynch outperformed the S&P 500 eleven times.

By contrast, another legendary name that stands out in the investment world is Vanguard’s Jack Bogle, the father of indexing. He believed that over the long term, investment managers could not outperform the broad market average, and high fees make such an objective even more difficult to achieve. This belief led him to create the first passively managed index fund for Vanguard in 1976.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Other Investment Strategies

Strong belief in the efficient market hypothesis calls into question the strategies pursued by active investors. If markets are truly efficient, investment companies are spending foolishly by richly compensating top fund managers.

The explosive growth in assets under management in index and ETF funds suggests that there are many investors who do believe in some form of the theory.

However, legions of day traders depend on technical analysis. Value managers use fundamental analysis to identify undervalued securities and there are hundreds of value funds in the U.S. alone.

These are only two examples of investors who believe that it is possible to outperform the market. With so many professional investors on each side of the efficient market hypothesis, it’s up to individual investors to weigh the evidence on both sides and to reach a conclusion about the efficiency of the financial markets that best matches their investing beliefs.

- Best Investment Apps

- Best Robo-Advisors

- Best Crypto Exchanges

- Best Crypto Staking Platforms

- Best Online Brokers

- Best Money Market Mutual Funds

- Best Investment Portfolio Management Apps

- Best Low-Risk Investments

- Best Fixed Income Investments

- What Is Investing?

- What Is A Brokerage Account?

- What Is A Bond?

- What Is the P/E Ratio?

- What Is Leverage?

- What Is Cryptocurrency?

- What Is Inflation & How Does It Work?

- What Is a Recession?

- What Is Forex Trading?

- How To Buy Stocks

- How To Invest In Stocks

- How To Buy Apple (AAPL) Stock

- How To Buy Tesla (TSLA) Stock

- How to Buy Bonds

- How To Invest In Real Estate

- How To Invest In Mutual Funds

- How To Calculate Dividend Yield

- How To Find a Financial Advisor Near You

- How To Choose A Financial Advisor

- How To Buy Gold

- Gold Price Today

- Silver Price Today

- Investment Calculator

- ROI Calculator

- Retirement Calculator

- Business Loan Calculator

- Cryptocurrency Tax Calculator

- Empower Review

- Acorns Review

- Betterment Review

- SoFi Automated Investing Review

- Wealthfront Review

- Masterworks Review

- Webull Review

- TD Ameritrade Review

- Robinhood Review

- Fidelity Review

Recession Fears—What To Do With Your Money During A Stock Market Slump

10 Most Expensive Stocks

7 Best Value Stocks Of August 2024

Best Wind Power Stocks Of August 2024

Top 10 Warren Buffett Stocks Of August 2024

What Happened To FAANG Stocks? They Became MAMAA Stocks

Rebecca Baldridge, CFA, is an investment professional and financial writer with over 20 years' experience in the financial services industry. In addition to a decade in banking and brokerage in Moscow, she has worked for Franklin Templeton Asset Management, The Bank of New York, JPMorgan Asset Management and Merrill Lynch Asset Management. She is a founding partner in Quartet Communications, a financial communications and content creation firm.

What is Efficient Market Hypothesis? | EMH Theory Explained

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) can help explain why many investors opt for passive investing strategies, such as buying index funds or exchange-traded funds ( ETFs ), which generate consistent returns over an extended period. However, the EMH theory remains controversial and has found as many opponents as proponents. This guide will explain the efficient market hypothesis, how it works, and why it is so contradictory.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

Invest in 70+ cryptocurrencies and 3,000+ other assets including stocks and precious metals.

0% commission on stocks - buy in bulk or just a fraction from as little as $10. Other fees apply. For more information, visit etoro.com/trading/fees.

Copy top-performing traders in real time, automatically.

eToro USA is registered with FINRA for securities trading.

What is the efficient market hypothesis?

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) claims that all assets are always fairly and accurately priced and trade at their fair market value on exchanges. If this theory is true, nothing can give you an edge to outperform the market using different investing strategies and make excess profits compared to those who follow market indexes.

Efficient market definition

An efficient market is where all asset prices listed on exchanges fully reflect their true and only value, thus making it impossible for investors to “beat the market” and profit from price discrepancies between the market price and the stock’s intrinsic value. The EMH claims the stock’s fair value, also called intrinsic value , is much the same as its market value , and finding undervalued or overvalued assets is non-viable.

Intrinsic value refers to an asset’s true, actual value, which is calculated using fundamental and technical analysis, whereas the market price is the currently listed price at which stock is bought and sold. When markets are efficient, the two values should be the same, but when they differ, it poses opportunities for investors to make an excess profit.

For markets to be completely efficient, all information should already be accounted for in stock prices and are trading on exchanges at their fair market value, which is practically impossible.

Hypothesis definition

A hypothesis is merely an assumption, an idea, or an argument that can be tested and reasoned not to be true. Something that isn’t fully supported by full facts or doesn’t match applied research.

For example, if sugar causes cavities, people who eat a lot of sweets are prone to cavities. And if the same applies here – if all information is reflected in a stock’s price, then its fair value should be the same as its market value and can not differ or be impacted by any other factors.

Beginners’ corner:

- What is Investing? Putting Money to Work ;

- 17 Common Investing Mistakes to Avoid ;

- 15 Top-Rated Investment Books of All Time ;

- How to Buy Stocks? Complete Beginner’s Guide ;

- 10 Best Stock Trading Books for Beginners ;

- 15 Highest-Rated Crypto Books for Beginners ;

- 6 Basic Rules of Investing ;

- Dividend Investing for Beginners ;

- Top 6 Real Estate Investing Books for Beginners ;

- 5 Passive Income Investment Ideas .

Fundamental and technical analysis in an efficient market

According to the EMH, stock prices are already accurately priced and consider all possible information. If markets are fully efficient, then no fundamental or technical analysis can help investors find anomalies and make an extra profit.

Fundamental analysis is a method to calculate a stock’s fair or intrinsic value by looking beyond the current market price by examining additional external factors like financial statements, the overall state of the economy, and competition, which can help define whether the stock is undervalued.

Also relevant is technical analysis , a method of forecasting the value of stocks by analyzing the historical price data, mainly looking at price and volume fluctuations occurring daily, weekly, or any other constant period, usually displayed on a chart.

The efficient market theory directly contradicts the possibility of outperforming the market using these two strategies; however, there are three different versions of EMH, and each slightly differs from the other.

Three forms of market efficiency

The efficient market hypothesis can take three different forms , depending on how efficient the markets are and which information is considered in theory:

1. Strong form efficiency

Strong form efficiency is the EMH’s purest form, and it is an assumption that all current and historical, both public and private, information that could affect the asset’s price is already considered in a stock’s price and reflects its actual value. According to this theory, stock prices listed on exchanges are entirely accurate.

Investors who support this theory trust that even inside information can’t give a trader an advantage, meaning that no matter how much extra information they have access to or how much analysis and research they do, they can not exceed standard returns.

Burton G. Malkiel, a leading proponent of the strong-form market efficiency hypothesis, doesn’t believe any analysis can help identify price discrepancies. Instead, he firmly believes in buy-and-hold investing, trusting it is the best way to maximize profits. However, factual research doesn’t support the possibility of a strong form of efficiency in any market.

2. Semi-strong form efficiency

The semi-strong version of the EMH suggests that only current and historical public (and not private) information is considered in the stock’s listed share prices. It is the most appropriate form of the efficient market hypothesis, and factual evidence supports that most capital markets in developed countries are generally semi-strong efficient.

This form of efficiency relies on the fact that public news about a particular stock or security has an immediate effect on the stock prices in the market and also suggests that technical and fundamental analysis can’t be used to make excess profits.

A semi-strong form of market efficiency theory accepts that investors can gain an advantage in trading only when they have access to any unknown private information unknown to the rest of the market.

3. Weak form efficiency

Weak market efficiency, also called a random walk theory, implies that investors can’t predict prices by analyzing past events, they are entirely random, and technical analysis cannot be used to beat the market.

Random walk theory proclaims stock prices always take a randomized path and are unpredictable, that investors can’t use past price changes and historical data trends to predict future prices, and that stock prices already reflect all current information.

For example, advocates of this form see no or limited benefit to technical analysis to discover investment opportunities. Instead, they would maintain a passive investment portfolio by buying index funds that track the overall market performance.

For example, the momentum investing method analyzes past price movements of stocks to predict future prices – it goes directly against the weak form efficiency, where all the current and past information is already reflected in their market prices.

A brief history of the efficient market hypothesis

The concept of the efficient market hypothesis is based on a Ph.D. dissertation by Eugene Fama , an American economist, and it assumes all prices of stocks or other financial instruments in the market are entirely accurate.

In 1970, Fama published this theory in “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work,” which outlines his vision where he describes the efficient market as: “A market in which prices always “fully reflect” available information is called “efficient.”

Another theory based on the EMH, the random walk theory by Burton G. Malkiel , states that prices are completely random and not dependent on any factor. Not even past information, and that outperforming the market is a matter of chance and luck and not a point of skill.

Fama has acknowledged that the term can be misleading and that markets can’t be efficient 100% of the time, as there is no accurate way of measuring it. The EMH accepts that random and unexpected events can affect prices but claims they will always be leveled out and revert to their fair market value.

What is an inefficient market?

The efficient market hypothesis is a theory, and in reality, most markets always display some inefficiencies to a certain extent. It means that market prices don’t always reflect their true value and sometimes fail to incorporate all available information to be priced accurately.

In extreme cases, an inefficient market may even lead to a market failure and can occur for several reasons.

An inefficient market can happen due to:

- A lack of buyers and sellers;

- Absence of information;

- Delayed price reaction to the news;

- Transaction costs;

- Human emotion;

- Market psychology.

The EMH claims that in an efficiently operating market, all asset prices are always correct and consider all information; however, in an inefficient market, all available information isn’t reflected in the price, making bargain opportunities possible.

Moreover, the fact that there are inefficient markets in the world directly contradicts the efficient market theory, proving that some assets can be overvalued or undervalued, creating investment opportunities for excess gains.

Validity of the efficient market hypothesis

With several arguments and real-life proof that assets can become under- or overvalued, the efficient market hypothesis has some inconsistencies, and its validity has repeatedly been questioned.

While supporters argue that searching for undervalued stock opportunities using technical and fundamental analysis to predict trends is pointless, opponents have proven otherwise. Although academics have proof supporting the EMH, there’s also evidence that overturns it.

The EMH implies there are no chances for investors to beat the market, but for example, investing strategies like arbitrage trading or value investing rely on minor discrepancies between the listed prices and the actual value of the assets.

A prime example is Warren Buffet, one of the world’s wealthiest and most successful investors, who has consistently beaten the market over more extended periods through value investing approach, which by definition of EMH is unfeasible.

Another example is the stock market crash in 1987, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) fell over 20% on the same day, which shows that asset prices can significantly deviate from their values.

Moreover, the fact that active traders and active investing techniques exist also displays some evidence of inconsistencies and that a completely efficient market is, in reality, impossible.

Contrasting beliefs about the efficient market hypothesis

Although the EMH has been largely accepted as the cornerstone of modern financial theory, it is also controversial. The proponents of the EMH argue that those who outperform the market and generate an excess profit have managed to do so purely out of luck, that there is no skill involved, and that stocks can still, without a real cause or reason, outperform, whereas others underperform.

Moreover, it is necessary to consider that even new information takes time to take effect in prices, and in actual efficiency, prices should adjust immediately. If the EMH allows for these inefficiencies, it is a question of whether an absolute market efficiency, strong form efficiency, is at all possible. But as this theory implies, there is little room for beating the market, and believers can rely on returns from a passive index investing strategy.

Even though possible, proponents assume neither technical nor fundamental analysis can help predict trends and produce excess profits consistently, and theoretically, only inside information could result in outsized returns.

Moreover, several anomalies contradict the market efficiency, including the January anomaly, size anomaly, and winners-losers anomaly, but as usual, factual evidence both contradicts and supports these anomalies.

Parting opinions about the different versions of the EMH reflect in investors’ investing strategies. For example, supporters of the strong form efficiency might opt for passive investing strategies like buying index funds. In contrast, practitioners of the weak form of efficiency might leverage arbitrage trading to generate profits.

Marketing strategies in an efficient and inefficient market

On the one side, some academics and investors support Fama’s theory and most likely opt for passive investing strategies. On the other, some investors believe assets can become undervalued and try to use skill and analysis to outperform the market via active trading.

Passive investing

Passive investing is a buy-and-hold strategy where investors seek to generate stable gains over a more extended period as fewer complexities are involved, such as less time and tax spent compared to an actively managed portfolio.

People who believe in the efficient market hypothesis use passive investing techniques to create lower yet stable gains and use strategies with optimal gains through maximizing returns and minimizing risk.

Proponents of the EMH would use passive investing, for example:

- Invest in Index Funds;

- Invest in Exchange-traded Funds (ETFs).

However, it is important to note that other mutual funds also use active portfolio management intending to outperform indices, and passive investing strategies aren’t only for those who believe in the EMH.

Active investing

Active portfolio managers use research, analysis, skill, and experience to discover market inefficiencies to generate a higher profit over a shorter period and exceed the benchmark returns.

Generally, passive investing strategies generate returns in the long run, whereas active investing can generate higher returns in the short term.

Opponents of the EMH might use active investing techniques, for example:

- Arbitrage and speculation;

- Momentum investing ;

- Value investing .

The fact that these active trading strategies exist and have proven to generate above-market returns shows that prices don’t always reflect their market value.

For instance, if a technology company launches a new innovative product, it might not be immediately reflected in its stock price and have a delayed reaction in the market.

Suppose a trader has access to unpublished and private inside information. In that case, it will allow them to purchase stocks at a much lower value and sell for a profit after the announcement goes public, capitalizing on the speculated price movements.

Passive and active portfolio managers are often compared in terms of performance, e.g., investment returns, and research hasn’t fully concluded which one outperforms the other,

Efficient market examples

Investors and academics have divided opinions about the efficient market hypothesis, and there have been cases where this theory has been overturned and proven inaccurate, especially with strong form efficiency. However, proof from the real world has shown how financial information directly affects the prices of assets and securities, making the market more efficient.

For example, when the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in the United States, which required more financial transparency through quarterly reporting from publicly traded businesses, came into effect in 2002, it affected stock price volatility. Every time a company released its quarterly numbers, stock market prices were deemed more credible, reliable, and accurate, making markets more efficient.

Example of a semi-strong form efficient market hypothesis

Let’s assume that ‘stock X’ is trading at $40 per share and is about to release its quarterly financial results. In addition, there was some unofficial and unconfirmed information that the company has achieved impressive growth, which increased the stock price to $50 per share.

After the release of the actual results, the stock price decreased to $30 per share instead. So whereas the general talk before the official announcement made the stock price jump, the official news launch dropped it.

Only investors who had inside private information would have known to short-sell the stock , and the ones who followed the publicly available information would have bought it at a high price and incurred a loss.

What can make markets more efficient?

There are a few ways markets can become more efficient, and even though it is easy to prove the EMH has no solid base, there is some evidence its relevance is growing.

First , markets become more efficient when more people participate, buy and sell and engage, and bring more information to be incorporated into the stock prices. Moreover, as markets become more liquid, it brings arbitrage opportunities; arbitrageurs exploiting these inefficiencies will, in turn, contribute to a more efficient market.

Secondly , given the faster speed and availability of information and its quality, markets can become more efficient, thus reducing above-market return opportunities. A thoroughly efficient market, strong efficiency, is characterized by the complete and instant transmission of information.

To make this possible, there should be:

- Complete absence of human emotion in investing decisions;

- Universal access to high-speed pricing analysis systems;

- Universally accepted system for pricing stocks;

- All investors accept identical returns and losses.

The bottom line

At its core, market efficiency is the ability to incorporate all information in stock prices and provide the most accurate opportunities for investors; however, it isn’t easy to imagine a fully efficient market.

Research has shown that most developed capital markets fall into the semi-strong efficient category. However, whether or not stock markets can be fully efficient conclusively and to what degree continues to be a heated debate among academics and investors.

Disclaimer: The content on this site should not be considered investment advice. Investing is speculative. When investing, your capital is at risk.

FAQs on the efficient market hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) claims that prices of assets such as stocks are trading at accurate market prices, leaving no opportunities to generate outsized returns. As a result, nothing could give investors an edge to outperform the market, and assets can’t become under- or overvalued.

What are three forms of the efficient market hypothesis?

The efficient market hypothesis takes three forms: first, the purest form is strong form efficiency, which considers current and past information. The second form is semi-strong efficiency, which includes only current and past public, and not private, information. Finally, the third version is weak form efficiency, which claims stock prices always take a randomized path.

What contradicts the efficient market hypothesis?

The efficient market hypothesis directly contradicts the existence of investment strategies, and cases that have proved to generate excess gains are possible, for example, via approaches like value or momentum investing.

When more investors engage in the market by buying and selling, they also bring more information that can be incorporated into the stock prices and make them more accurate. Moreover, the faster movement of information and news nowadays increases accuracy and data quality, thus making markets more efficient.

Weekly Finance Digest

By subscribing you agree with Finbold T&C’s & Privacy Policy

Related guides

How to Buy Uber Stock [2024] | Invest in UBER

Leading Tactics for Building a Crypto Marketing Strategy for High Engagement

How to Buy Joby Aviation stock [2024] | Invest in JOBY

How much money does Ronaldo make a second?

Introducing price alerts.

Create price alerts for stocks & crypto. Get started Get started

Disclaimer: The information on this website is for general informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, tax, or investment advice. This site does not make any financial promotions, and all content is strictly informational. By using this site, you agree to our full disclaimer and terms of use. For more information, please read our complete Global Disclaimer .

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Geography & Travel

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Introduction

Three forms of efficient-market hypothesis

What the efficient-market hypothesis means for investors, criticisms and limitations, validation on a large scale, the bottom line.

Are markets efficient? How Eugene Fama kicked off a controversy

One of the most controversial topics in finance is the efficient-market hypothesis, developed by Eugene Fama in 1965. In a nutshell, the theory says that the financial markets are efficient, so no one can gain an edge in them.

Fama’s paper “The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices,” which was published in the Journal of Business , doesn’t use the term efficient-market hypothesis. Rather, it says that “… a situation where successive price changes are independent is consistent with the existence of an ‘efficient’ market for securities , that is, a market where, given the available information, actual prices at every point in time represent very good estimates of intrinsic values.”

- The efficient-market hypothesis claims that stock prices contain all information, so there are no benefits to financial analysis.

- The theory has been proven mostly correct, although anomalies exist.

- Index investing, which is justified by the efficient-market hypothesis, has supported the theory.

That line set off a theoretical explosion in university economics departments. At first, Wall Street ignored the idea of market efficiency because it contradicted the work of most analysts and brokers. But the evidence became too strong to ignore, and the efficient-market hypothesis is now generally accepted despite its weaknesses, including the inability at times to determine why the price of an asset has risen or fallen.

But just what is the efficient-market hypothesis? What are its key principles and its implications for investors?

The efficient-market hypothesis says that financial markets are effective in processing and reflecting all available information with little or no waste, making it impossible for investors to consistently outperform the market based on information already known to the public. One area of debate is how strong the efficient-market hypothesis is. In 1970, Fama wrote another paper that explored the idea of market efficiency in more depth, noting that it seemed to take three forms:

- Weak-form efficiency: In this form, market prices reflect all past trading information, such as historical prices and trading volumes. According to weak-form efficiency, technical analysis (the study of past price and volume data) cannot consistently generate excess returns because this information is already reflected in stock prices .

- Semi-strong-form efficiency: This idea says that all publicly available information, including news and past trading data , is fully reflected in stock prices. As a result, neither technical analysis nor fundamental analysis (the study of financial statements and economic factors) can consistently beat the market, because all available information is already incorporated into prices.

- Strong-form efficiency: The most robust version of the efficient-market hypothesis contends that all information, public and private, is fully reflected in stock prices. In other words, no individual or group of investors possesses information that can consistently yield superior returns. This form of efficiency suggests that insider trading is futile in the long run, as insider information is also reflected in stock prices.

The biggest implication of the efficient-market hypothesis is that index funds and other passive investing strategies offer better risk-adjusted returns after fees than active investment. At an extreme, it suggests that doing research and analysis is no better than picking stocks at random.

Study the art of stock picking.

Want to choose stocks that are right for you and become a better investor? Learn about the benefits of diversification .

One assumption in the efficient-market hypothesis is that information is distributed immediately throughout the market. In 1965, that seemed ridiculous and formed one critique of the model, but financial services companies soon realized that speed pays off. The sooner someone could find an anomaly and act on it, the faster they could lock in a profit. Today, brokerages and market makers tie their servers directly to securities exchanges to shave milliseconds from execution times.

Despite its significance, the efficient-market hypothesis is not without criticisms and limitations. Some critics argue that several factors prevent markets from being perfectly efficient, including:

- Behavioral biases —errors in judgment, decision-making, and thinking when evaluating information.

- Information asymmetry —where one person has more or better information than someone else.

- Market frictions —anything that interferes with market transactions, including transaction costs, taxes, regulation, and information glitches.

Naysayers point to market bubbles , crashes , and persistent anomalies as evidence against strong market efficiency. An entire field of finance, behavioral economics , has developed to explore how market participants are inefficient.

Another criticism of the efficient-market hypothesis is that certain valuation anomalies persist, even though the hypothesis says they shouldn’t. One is that small companies tend to outperform larger ones; another is that value stocks tend to outperform those with higher price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios . In 1992, Fama and Kenneth French published a paper showing that those anomalies were real and should be incorporated into financial valuation models.

The efficient-market hypothesis remains a cornerstone of financial theory and has had a profound influence on investment strategies, portfolio management, and the understanding of financial markets. Although its three forms provide an accepted framework for thinking about market efficiency, the debate about its validity continues.

Investors and researchers alike grapple with the ever-evolving nature of financial markets, where the balance between efficiency and inefficiency remains a subject of ongoing study and discussion. Regardless of your stance on the efficient-market hypothesis, it has undeniably shaped how we approach investing and market analysis today.

In 2013, Fama received the Nobel Prize for his work. The market has accepted the efficient-market hypothesis, and index investing has revolutionized the financial industry. One of Fama’s students, David Booth, started an investment company specializing in index investing for institutional clients (such as pension funds and insurance companies). Booth was so successful—and so grateful—that he donated $300 million to the University of Chicago in 2008. In exchange, the university named its business school after him. Talk about a legacy .

- The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices | jstor.org

- Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work | jstor.org

- Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds | sciencedirect.com

- Eugene F. Fama – Facts | nobelprize.org

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

Written by True Tamplin, BSc, CEPF®

Reviewed by subject matter experts.

Updated on July 12, 2023

Are You Retirement Ready?

Table of contents, efficient market hypothesis (emh) overview.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a theory that suggests financial markets are efficient and incorporate all available information into asset prices.

According to the EMH, it is impossible to consistently outperform the market by employing strategies such as technical analysis or fundamental analysis.

The hypothesis argues that since all relevant information is already reflected in stock prices, it is not possible to gain an advantage and generate abnormal returns through stock picking or market timing.

The EMH comes in three forms: weak, semi-strong, and strong, each representing different levels of market efficiency.

While the EMH has faced criticisms and challenges, it remains a prominent theory in finance that has significant implications for investors and market participants.

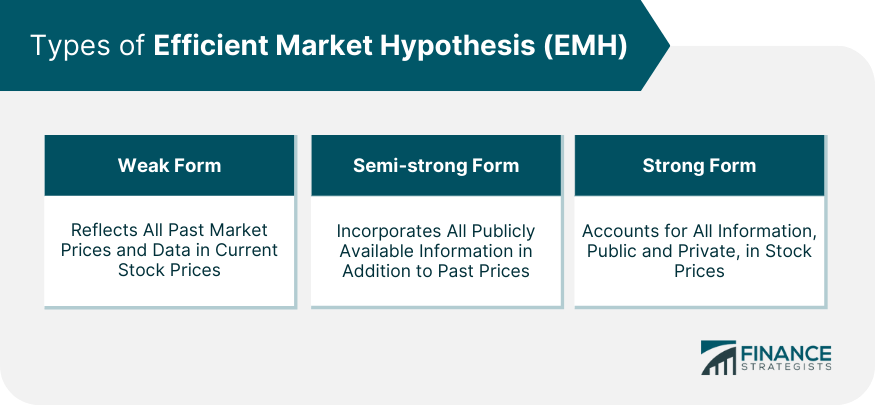

Types of Efficient Market Hypothesis

The Efficient Market Hypothesis can be categorized into the following:

Weak Form EMH

The weak form of EMH posits that all past market prices and data are fully reflected in current stock prices.

Therefore, technical analysis methods, which rely on historical data, are deemed useless as they cannot provide investors with a competitive edge. However, this form doesn't deny the potential value of fundamental analysis.

Semi-strong Form EMH

The semi-strong form of EMH extends beyond historical prices and suggests that all publicly available information is instantly priced into the market.

This includes financial statements, news releases, economic indicators, and other public disclosures. Therefore, neither technical analysis nor fundamental analysis can yield superior returns consistently.

Strong Form EMH

The most extreme version of EMH, the strong form, asserts that all information, both public and private, is fully reflected in stock prices.

Even insiders with privileged information cannot consistently achieve higher-than-average market returns. This form, however, is widely criticized as it conflicts with securities regulations that prohibit insider trading .

Assumptions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Three fundamental assumptions underpin the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

All Investors Have Access to All Publicly Available Information

This assumption holds that the dissemination of information is perfect and instantaneous. All market participants receive all relevant news and data about a security or market simultaneously, and no investor has privileged access to information.

All Investors Have a Rational Expectation

In EMH, it is assumed that investors collectively have a rational expectation about future market movements. This means that they will act in a way that maximizes their profits based on available information, and their collective actions will cause securities' prices to adjust appropriately.

Investors React Instantly to New Information

In an efficient market, investors instantaneously incorporate new information into their investment decisions. This immediate response to news and data leads to swift adjustments in securities' prices, rendering it impossible to "beat the market."

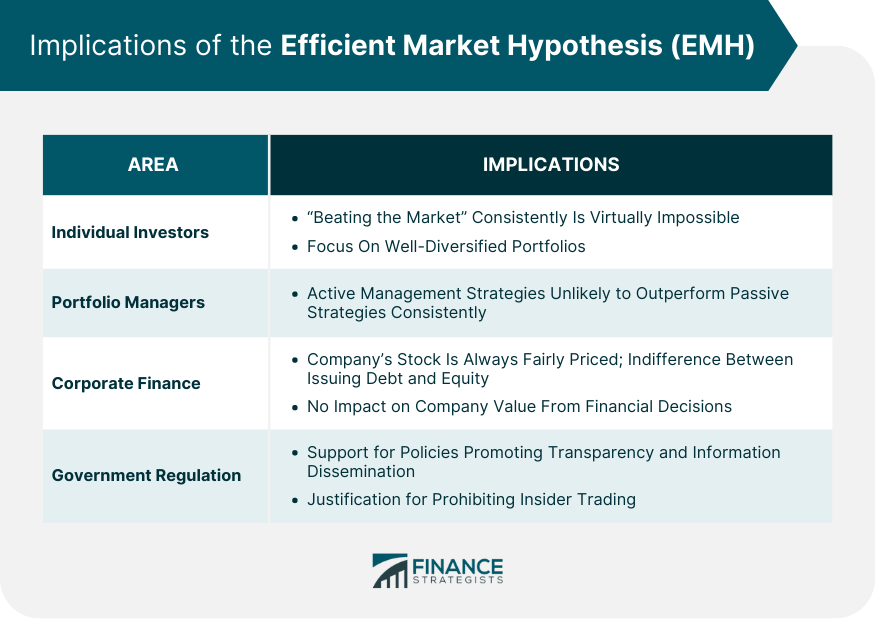

Implications of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The EMH has several implications across different areas of finance.

Implications for Individual Investors

For individual investors, EMH suggests that "beating the market" consistently is virtually impossible. Instead, investors are advised to invest in a well-diversified portfolio that mirrors the market, such as index funds.

Implications for Portfolio Managers

For portfolio managers , EMH implies that active management strategies are unlikely to outperform passive strategies consistently. It discourages the pursuit of " undervalued " stocks or timing the market.

Implications for Corporate Finance

In corporate finance, EMH implies that a company's stock is always fairly priced, meaning it should be indifferent between issuing debt and equity . It also suggests that stock splits , dividends , and other financial decisions have no impact on a company's value.

Implications for Government Regulation

For regulators , EMH supports policies that promote transparency and information dissemination. It also justifies the prohibition of insider trading.

Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Despite its widespread acceptance, the EMH has attracted significant criticism and controversy.

Behavioral Finance and the Challenge to EMH

Behavioral finance argues against the notion of investor rationality assumed by EMH. It suggests that cognitive biases often lead to irrational decisions, resulting in mispriced securities.

Examples include overconfidence, anchoring, loss aversion, and herd mentality, all of which can lead to market anomalies.

Market Anomalies and Inefficiencies

EMH struggles to explain various market anomalies and inefficiencies. For instance, the "January effect," where stocks tend to perform better in January, contradicts the EMH.

Similarly, the "momentum effect" suggests that stocks that have performed well recently tend to continue performing well, which also challenges EMH.

Financial Crises and the Question of Market Efficiency

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 raised serious questions about market efficiency. The catastrophic market failure suggested that markets might not always price securities accurately, casting doubt on the validity of EMH.

Empirical Evidence of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Empirical evidence on the EMH is mixed, with some studies supporting the hypothesis and others refuting it.

Evidence Supporting EMH

Several studies have found that professional fund managers, on average, do not outperform the market after accounting for fees and expenses.

This finding supports the semi-strong form of EMH. Similarly, numerous studies have shown that stock prices tend to follow a random walk, supporting the weak form of EMH.

Evidence Against EMH

Conversely, other studies have documented persistent market anomalies that contradict EMH.

The previously mentioned January and momentum effects are examples of such anomalies. Moreover, the occurrence of financial bubbles and crashes provides strong evidence against the strong form of EMH.

Efficient Market Hypothesis in Modern Finance

Despite criticisms, the EMH continues to shape modern finance in profound ways.

EMH and the Rise of Passive Investing

The EMH has been a driving force behind the rise of passive investing. If markets are efficient and all information is already priced into securities, then active management cannot consistently outperform the market.

As a result, many investors have turned to passive strategies, such as index funds and ETFs .

Impact of Technology on Market Efficiency

Advances in technology have significantly improved the speed and efficiency of information dissemination, arguably making markets more efficient. High-frequency trading and algorithmic trading are now commonplace, further reducing the possibility of beating the market.

Future of EMH in Light of Evolving Financial Markets

While the debate over market efficiency continues, the growing influence of machine learning and artificial intelligence in finance could further challenge the EMH.

These technologies have the potential to identify and exploit subtle patterns and relationships that human investors might miss, potentially leading to market inefficiencies.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis is a crucial financial theory positing that all available information is reflected in market prices, making it impossible to consistently outperform the market. It manifests in three forms, each with distinct implications.

The weak form asserts that all historical market information is accounted for in current prices, suggesting technical analysis is futile.

The semi-strong form extends this to all publicly available information, rendering both technical and fundamental analysis ineffective.

The strongest form includes even insider information, making all efforts to beat the market futile. EMH's implications are profound, affecting individual investors, portfolio managers, corporate finance decisions, and government regulations.

Despite criticisms and evidence of market inefficiencies, EMH remains a cornerstone of modern finance, shaping investment strategies and financial policies.

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) FAQs

What is the efficient market hypothesis (emh), and why is it important.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is a theory suggesting that financial markets are perfectly efficient, meaning that all securities are fairly priced as their prices reflect all available public information. It's important because it forms the basis for many investment strategies and regulatory policies.

What are the three forms of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)?

The three forms of the EMH are the weak form, semi-strong form, and strong form. The weak form suggests that all past market prices are reflected in current prices. The semi-strong form posits that all publicly available information is instantly priced into the market. The strong form asserts that all information, both public and private, is fully reflected in stock prices.

How does the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) impact individual investors and portfolio managers?

According to the EMH, consistently outperforming the market is virtually impossible because all available information is already factored into the prices of securities. Therefore, it suggests that individual investors and portfolio managers should focus on creating well-diversified portfolios that mirror the market rather than trying to beat the market.

What are some criticisms of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)?

Criticisms of the EMH often come from behavioral finance, which argues that cognitive biases can lead investors to make irrational decisions, resulting in mispriced securities. Additionally, the EMH has difficulty explaining certain market anomalies, such as the "January effect" or the "momentum effect." The occurrence of financial crises also raises questions about the validity of EMH.

How does the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) influence modern finance and its future?

Despite criticisms, the EMH has profoundly shaped modern finance. It has driven the rise of passive investing and influenced the development of many financial regulations. With advances in technology, the speed and efficiency of information dissemination have increased, arguably making markets more efficient. Looking forward, the growing influence of artificial intelligence and machine learning could further challenge the EMH.

About the Author

True Tamplin, BSc, CEPF®

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide , a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University , where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon , Nasdaq and Forbes .

Related Topics

- AML Regulations for Cryptocurrencies

- Active vs Passive Investment Management

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Cryptocurrencies

- Aggressive Investing

- Asset Management vs Investment Management

- Becoming a Millionaire With Cryptocurrency

- Burning Cryptocurrency

- Cheapest Cryptocurrencies With High Returns

- Complete List of Cryptocurrencies & Their Market Capitalization

- Countries Using Cryptocurrency

- Countries Where Bitcoin Is Illegal

- Crypto Investor’s Guide to Form 1099-B

- Cryptocurrency Airdrop

- Cryptocurrency Alerting

- Cryptocurrency Analysis Tool

- Cryptocurrency Cloud Mining

- Cryptocurrency Risks

- Cryptocurrency Taxes

- Depth of Market

- Digital Currency vs Cryptocurrency

- Fiat vs Cryptocurrency

- Fundamental Analysis in Cryptocurrencies

- Global Macro Hedge Fund

- Gold-Backed Cryptocurrency

- How to Buy a House With Cryptocurrencies

- How to Cash Out Your Cryptocurrency

- Inventory Turnover Rate (ITR)

- Largest Cryptocurrencies by Market Cap

- Types of Fixed Income Investments

Ask a Financial Professional Any Question

Discover wealth management solutions near you, our recommended advisors.

Claudia Valladares

WHY WE RECOMMEND:

Fee-Only Financial Advisor Show explanation

Bilingual in english / spanish, founder of wisedollarmom.com, quoted in gobanking rates, yahoo finance & forbes.

IDEAL CLIENTS:

Retirees, Immigrants & Sudden Wealth / Inheritance

Retirement Planning, Personal finance, Goals-based Planning & Community Impact

Taylor Kovar, CFP®

Certified financial planner™, 3x investopedia top 100 advisor, author of the 5 money personalities & keynote speaker.

Business Owners, Executives & Medical Professionals

Strategic Planning, Alternative Investments, Stock Options & Wealth Preservation

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

Fact Checked

At Finance Strategists, we partner with financial experts to ensure the accuracy of our financial content.

Our team of reviewers are established professionals with decades of experience in areas of personal finance and hold many advanced degrees and certifications.

They regularly contribute to top tier financial publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, U.S. News & World Report, Reuters, Morning Star, Yahoo Finance, Bloomberg, Marketwatch, Investopedia, TheStreet.com, Motley Fool, CNBC, and many others.

This team of experts helps Finance Strategists maintain the highest level of accuracy and professionalism possible.

Why You Can Trust Finance Strategists

Finance Strategists is a leading financial education organization that connects people with financial professionals, priding itself on providing accurate and reliable financial information to millions of readers each year.

We follow strict ethical journalism practices, which includes presenting unbiased information and citing reliable, attributed resources.

Our goal is to deliver the most understandable and comprehensive explanations of financial topics using simple writing complemented by helpful graphics and animation videos.

Our writing and editorial staff are a team of experts holding advanced financial designations and have written for most major financial media publications. Our work has been directly cited by organizations including Entrepreneur, Business Insider, Investopedia, Forbes, CNBC, and many others.

Our mission is to empower readers with the most factual and reliable financial information possible to help them make informed decisions for their individual needs.

How It Works

Step 1 of 3, ask any financial question.

Ask a question about your financial situation providing as much detail as possible. Your information is kept secure and not shared unless you specify.

Step 2 of 3

Our team will connect you with a vetted, trusted professional.

Someone on our team will connect you with a financial professional in our network holding the correct designation and expertise.

Step 3 of 3

Get your questions answered and book a free call if necessary.

A financial professional will offer guidance based on the information provided and offer a no-obligation call to better understand your situation.

Where Should We Send Your Answer?

Just a Few More Details

We need just a bit more info from you to direct your question to the right person.

Tell Us More About Yourself

Is there any other context you can provide.

Pro tip: Professionals are more likely to answer questions when background and context is given. The more details you provide, the faster and more thorough reply you'll receive.

What is your age?

Are you married, do you own your home.

- Owned outright

- Owned with a mortgage

Do you have any children under 18?

- Yes, 3 or more

What is the approximate value of your cash savings and other investments?

- $50k - $250k

- $250k - $1m

Pro tip: A portfolio often becomes more complicated when it has more investable assets. Please answer this question to help us connect you with the right professional.

Would you prefer to work with a financial professional remotely or in-person?

- I would prefer remote (video call, etc.)

- I would prefer in-person

- I don't mind, either are fine

What's your zip code?

- I'm not in the U.S.

Submit to get your question answered.

A financial professional will be in touch to help you shortly.

Part 1: Tell Us More About Yourself

Do you own a business, which activity is most important to you during retirement.

- Giving back / charity

- Spending time with family and friends

- Pursuing hobbies

Part 2: Your Current Nest Egg

Part 3: confidence going into retirement, how comfortable are you with investing.

- Very comfortable

- Somewhat comfortable

- Not comfortable at all

How confident are you in your long term financial plan?

- Very confident

- Somewhat confident

- Not confident / I don't have a plan

What is your risk tolerance?

How much are you saving for retirement each month.

- None currently

- Minimal: $50 - $200

- Steady Saver: $200 - $500

- Serious Planner: $500 - $1,000

- Aggressive Saver: $1,000+

How much will you need each month during retirement?

- Bare Necessities: $1,500 - $2,500

- Moderate Comfort: $2,500 - $3,500

- Comfortable Lifestyle: $3,500 - $5,500

- Affluent Living: $5,500 - $8,000

- Luxury Lifestyle: $8,000+

Part 4: Getting Your Retirement Ready

What is your current financial priority.

- Getting out of debt

- Growing my wealth

- Protecting my wealth

Do you already work with a financial advisor?

Which of these is most important for your financial advisor to have.

- Tax planning expertise

- Investment management expertise

- Estate planning expertise

- None of the above

Where should we send your answer?

Submit to get your retirement-readiness report., get in touch with, great the financial professional will get back to you soon., where should we send the downloadable file, great hit “submit” and an advisor will send you the guide shortly., create a free account and ask any financial question, learn at your own pace with our free courses.

Take self-paced courses to master the fundamentals of finance and connect with like-minded individuals.

Get Started

To ensure one vote per person, please include the following info, great thank you for voting., get in touch, submit your info below and someone will get back to you shortly..

- All Self-Study Programs

- Premium Package

- Basic Package

- Private Equity Masterclass

- VC Term Sheets & Cap Tables

- Sell-Side Equity Research (ERC © )

- Buy-Side Financial Modeling

- Real Estate Financial Modeling

- REIT Modeling

- FP&A Modeling (CFPAM ™ )

- Project Finance Modeling

- Bank & FIG Modeling

- Oil & Gas Modeling

- Biotech Sum of the Parts Valuation

- The Impact of Tax Reform on Financial Modeling

- Corporate Restructuring

- The 13-Week Cash Flow Model

- Accounting Crash Course

- Advanced Accounting

- Crash Course in Bonds

- Analyzing Financial Reports

- Interpreting Non-GAAP Reports

- Fixed Income Markets (FIMC © )

- Equities Markets Certification (EMC © )

- ESG Investing

- Excel Crash Course

- PowerPoint Crash Course

- Ultimate Excel VBA Course

- Investment Banking "Soft Skills"

- Networking & Behavioral Interview

- 1000 Investment Banking Interview Questions

- Virtual Boot Camps

- 1:1 Coaching

- Corporate Training

- University Training

- Free Content

- Support/Contact Us

- About Wall Street Prep

- Investment Analysis

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

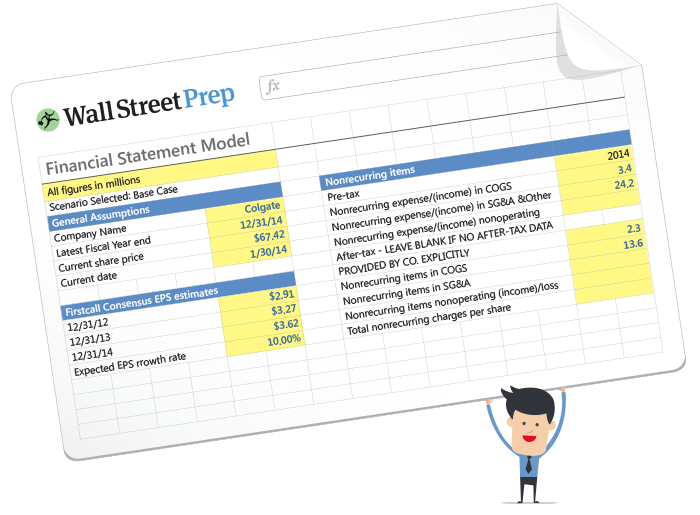

Step-by-Step Guide to Understanding the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

Learn Online Now

What is the Efficient Market Hypothesis?

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) theory – introduced by economist Eugene Fama – states that the prevailing asset prices in the market fully reflect all available information.

Table of Contents

What is the Definition of Efficient Market Hypothesis?

Eugene fama quote: stock market theory, what are the 3 forms of efficient market hypothesis, emh and passive investing, efficient market hypothesis vs. active management, random walk theory vs. efficient market hypothesis (emh), efficient market hypothesis conclusion.

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) theorizes about the relationship between the:

- Information Availability in the Market

- Current Market Trading Prices (i.e. Share Prices of Public Equities)

Under the efficient market hypothesis, following the release of new information/data to the public markets, the prices will adjust instantaneously to reflect the market-determined, “accurate” price.

EMH claims that all available information is already “priced in” – meaning that the assets are priced at their fair value . Therefore, if we assume EMH is true, the implication is that it is practically impossible to outperform the market consistently.

“The proposition is that prices reflect all available information, which in simple terms means since prices reflect all available information, there’s no way to beat the market.” – Eugene Fama

Weak Form, Semi-Strong, and Strong Form Market Efficiency

Eugene Fama classified market efficiency into three distinct forms:

- Weak Form EMH: All past information like historical trading prices and volume data is reflected in the market prices.

- Semi-Strong EMH: All publicly available information is reflected in the current market prices.

- Strong Form EMH: All public and private information, inclusive of insider information, is reflected in market prices.

The Wharton Online & Wall Street Prep Buy-Side Investing Certificate Program

Fast track your career as a hedge fund or equity research professional. Enrollment is open for the Sep. 9 - Nov. 10 cohort.

Broadly put, there are two approaches to investing:

- Active Management: Reliance on the personal judgment, analytical research, and financial models of investment professionals to manage a portfolio of securities (e.g. hedge funds).

- Passive Investing: “Hands-off,” buy-and-hold portfolio investment strategy with long-term holding periods, with minimal portfolio adjustments.

As EMH has grown in widespread acceptance, passive investing has become more common, especially for retail investors (i.e. non-institutions).

Index investing is perhaps the most common form of passive investing, whereby investors seek to replicate and hold a security that tracks market indices.

In recent times, some of the main beneficiaries of the shift from active management to passive investing have been index funds such as:

- Mutual Funds

- Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

The widely held belief among passive investors is that it’s very difficult to beat the market, and attempting to do so would be futile.

Plus, passive investing is more convenient for the everyday investor to participate in the markets – with the added benefit of being able to avoid high fees charged by active managers.

Long story short, hedge fund professionals struggle to “beat the market” despite spending the entirety of their time researching these stocks with more data access than most retail investors.

With that said, it seems like the odds are stacked against retail investors, who invest with fewer resources, information (e.g. reports), and time.

One could make the argument that hedge funds are not actually intended to outperform the market (i.e. generate alpha ), but to generate stable, low returns regardless of market conditions – as implied by the term “hedge” in the name.

However, considering the long-term horizon of passive investing, the urgency of receiving high returns on behalf of limited partners (LPs) is not a relevant factor for passive investors.

Typically, passive investors invest in market indices tracking products with the understanding that the market could crash, but patience pays off over time (or the investor can also purchase more – i.e. a practice known as “dollar-cost averaging”, or DCA).

1. Random Walk Theory

The “ random walk theory ” arrives at the conclusion that attempting to predict and profit from share price movements is futile.

According to the random walk theory , share price movements are driven by random, unpredictable events – which nobody, regardless of their credentials, can accurately predict.

For the most part, the accuracy of predictions and past successes are more so due to chance as opposed to actual skill.

2. Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

By contrast, EMH theorizes that asset prices, to some extent, accurately reflect all the information available in the market.

Under EMH, a company’s share price can neither be undervalued nor overvalued, as the shares are trading precisely where they should be given the “efficient” market structure (i.e. are priced at their fair value on exchanges).

In particular, if the EMH is strong-form efficient, there is essentially no point in active management, especially considering the mounting fees.

Since EMH contends that the current market prices reflect all information, attempts to outperform the market by finding mispriced securities or accurately timing the performance of a certain asset class come down to “luck” as opposed to skill.

One important distinction is that EMH refers specifically to long-term performance – therefore, if a fund achieves “above-market” returns – that does NOT invalidate the EMH theory.

In fact, most EMH proponents agree that outperforming the market is certainly plausible, but these occurrences are infrequent over the long term and not worth the short-term effort (and active management fees).

Thereby, EMH supports the notion that it is NOT feasible to consistently generate returns in excess of the market over the long term.

- Google+

- 100+ Excel Financial Modeling Shortcuts You Need to Know

- The Ultimate Guide to Financial Modeling Best Practices and Conventions

- What is Investment Banking?

- Essential Reading for your Investment Banking Interview

We're sending the requested files to your email now. If you don't receive the email, be sure to check your spam folder before requesting the files again.

The Wall Street Prep Quicklesson Series

7 Free Financial Modeling Lessons

Get instant access to video lessons taught by experienced investment bankers. Learn financial statement modeling, DCF, M&A, LBO, Comps and Excel shortcuts.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Assets & Markets

- Mutual Funds

Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH)

EMH Definition and Forms

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ScreenShot2020-03-23at2.04.43PM-59de96b153e540c498f1f1da8ce5c965.png)

What Is Efficient Market Hypothesis?

What are the types of emh, emh and investing strategies, the bottom line, frequently asked questions (faqs).

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is one of the main reasons some investors may choose a passive investing strategy. It helps to explain the valid rationale of buying these passive mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) essentially says that all known information about investment securities, such as stocks, is already factored into the prices of those securities. If that is true, no amount of analysis can give you an edge over "the market."

EMH does not require that investors be rational; it says that individual investors will act randomly. But as a whole, the market is always "right." In simple terms, "efficient" implies "normal."

For example, an unusual reaction to unusual information is normal. If a crowd suddenly starts running in one direction, it's normal for you to run that way as well, even if there isn't a rational reason for doing so.

There are three forms of EMH: weak, semi-strong, and strong. Here's what each says about the market.

- Weak Form EMH: Weak form EMH suggests that all past information is priced into securities. Fundamental analysis of securities can provide you with information to produce returns above market averages in the short term. But no "patterns" exist. Therefore, fundamental analysis does not provide a long-term advantage, and technical analysis will not work.

- Semi-Strong Form EMH: Semi-strong form EMH implies that neither fundamental analysis nor technical analysis can provide you with an advantage. It also suggests that new information is instantly priced into securities.

- Strong Form EMH: Strong form EMH says that all information, both public and private, is priced into stocks; therefore, no investor can gain advantage over the market as a whole. Strong form EMH does not say it's impossible to get an abnormally high return. That's because there are always outliers included in the averages.

EMH does not say that you can never outperform the market . It says that there are outliers who can beat the market averages. But there are also outliers who lose big to the market. The majority is closer to the median. Those who "win" are lucky; those who "lose" are unlucky.

Proponents of EMH, even in its weak form, often invest in index funds or certain ETFs. That is because those funds are passively managed and simply attempt to match, not beat, overall market returns.

Index investors might say they are going along with this common saying: "If you can't beat 'em, join 'em." Instead of trying to beat the market, they will buy an index fund that invests in the same securities as the benchmark index.

Some investors will still try to beat the market, believing that the movement of stock prices can be predicted, at least to some degree. For that reason, EMH does not align with a day trading strategy. Traders study short-term trends and patterns. Then, they attempt to figure out when to buy and sell based on these patterns. Day traders would reject the strong form of EMH.

For more on EMH, including arguments against it, check out the EMH paper from economist Burton G. Malkiel. Malkiel is also the author of the investing book "A Random Walk Down Main Street." The random walk theory says that movements in stock prices are random.

If you believe that you can't predict the stock market, you would most often support the EMH. But a short-term trader might reject the ideas put forth by EMH, because they believe that they are able to predict changes in stock prices.

For most investors, a passive, buy-and-hold , long-term strategy is useful. Capital markets are mostly unpredictable with random up and down movements in price.

When did the Efficient Market Hypothesis first emerge?

At the core of EMH is the theory that, in general, even professional traders are unable to beat the market in the long term with fundamental or technical analysis . That idea has roots in the 19th century and the "random walk" stock theory. EMH as a specific title is sometimes attributed to Eugene Fama's 1970 paper "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work."

How is the Efficient Market Hypothesis used in the real world?

Investors who utilize EMH in their real-world portfolios are likely to make fewer decisions than investors who use fundamental or technical analysis. They are more likely to simply invest in broad market products, such as S&P 500 and total market funds.

Corporate Finance Institute. " Efficient Markets Hypothesis ."

IG.com. " Random Walk Theory Definition ."

Quickonomics

Efficient Market Hypothesis

Definition of efficient market hypothesis.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is an investment theory that states that it is impossible to “beat the market” because stock market efficiency causes existing share prices to always incorporate and reflect all relevant information. That means stock prices always reflect all available information, and it is impossible to consistently outperform the market by using any information that is already available.

Note that different versions of the EMH exist, depending on the types of information included and their effects on market efficiency. For more information, check out our post on the three versions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis .

To illustrate this, let’s look at a hypothetical investor called John. John is an experienced trader who has been trading stocks for many years. He has access to the same information as everyone else, such as company financials, analyst reports, and news articles. He also has a good understanding of the stock market and is able to make informed decisions.

However, despite all his knowledge and experience, John can still not outperform the market consistently. This is because the stock prices already reflect all the available information (i.e., everyone else knows it too). Thus, even though John may be able to make a few successful trades, he will not be able to beat the market in the long run consistently.

Why Efficient Market Hypothesis Matters

The Efficient Market Hypothesis is an important concept for investors to understand. It helps them to understand why it is so difficult to outperform the market consistently. It also explains why it is essential to diversify investments and why it is vital to have a long-term investment strategy. Finally, it also serves as a reminder that no one has the edge over the market, and that it is impossible to predict the future.

To provide the best experiences, we and our partners use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us and our partners to process personal data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site and show (non-) personalized ads. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Click below to consent to the above or make granular choices. Your choices will be applied to this site only. You can change your settings at any time, including withdrawing your consent, by using the toggles on the Cookie Policy, or by clicking on the manage consent button at the bottom of the screen.

Efficient Market Hypothesis

Efficient market hypothesis or EMH is an investment theory which suggests that the prices of financial instruments reflect all available market information. Hence, investors cannot have an edge over each other by analysing the stocks and adopting different market timing strategies. According to this theory developed by Eugene Fama, investors can only earn high returns by taking more significant risks in the market.

Assumptions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Also referred to as an efficient market theory, EMH is based on the following assumptions –

- Stocks are traded on exchanges at their fair market values.

- This theory assumes that the market value of stocks represents all the relevant information.

- It also assumes that investors are not capable of outperforming the market since they have to make decisions based on the same available information.

Types of Efficient Market Hypothesis

EMH has three variations which constitute different market efficiency levels. They are discussed below –

- Weak form efficient market hypothesis

This is based on the assumption that the market prices of all financial instruments represent all public information related to the market. It does not reflect any information that is not yet disclosed publicly. Moreover, the efficient market hypothesis assumes that historical data like price and returns have no relation with the future price of a financial instrument.

This variation EMH also suggests that different strategies implemented by traders cannot fetch consistent returns. This is owing to the assumption that historical price points cannot predict future market value. Although this form of EMH dismisses the concept of technical analysis, it provides the opportunity for fundamental analysis. This helps all market participants to find out more information and earn an above-average return on investment.

- Semi strong form efficient market hypothesis

This version of EMH elaborates on the assumptions of the weak form and accepts that the market prices make quick adjustments in response to any new public information that is disclosed. Hence, there is no scope for both technical and fundamental analysis.

- Strong form efficient market hypothesis

This form of EMH states that the market prices of securities represent both historical and current information. This includes insider information as well as publicly disclosed information. It also suggests that the price reflects information available only to board members or the CEO of a company.

Impact of Efficient Market Hypothesis

EMH is gradually gathering popularity among traders. Market participants who advocate this theory usually tend to invest in index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) which are more passive in nature. This is one of the main advantages of the efficient market hypothesis.

These traders are reluctant to pay the high charges imposed by the experienced fund managers as they don’t even rely on the experts to outperform the market. However, recent data suggests that there are a few fund managers who have been consistent in beating the market.

Limitations of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Since its first implementation in the 1960s, many limitations of EMH have gradually emerged. They are discussed in detail below –

- Market crashes and speculative bubbles

Speculative bubbles tend to arise when the price of a financial instrument rises above its fair market value and reaches a point where market corrections take place. During this situation, prices begin to fall rapidly, which leads to a market crash.

But EMA suggests that both financial crashes and market bubbles should not arise. As a matter of fact, this theory completely dismisses their existence.

- Market anomalies