- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > College of Education > Teaching and Learning > Theses and Dissertations

Teaching and Learning Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2024 2024.

Beliefs of Male Elementary School Special Education and General Education Teachers Regarding Full Inclusion for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Saudi Arabia , Sultan Alanazi

The Integration of Assistive Technology by Female In-Service Teachers of Students with Learning Disabilities in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Interview Study , Badriah Alotaiby

Theses/Dissertations from 2023 2023

Saudi Parents as Advocates for Their Young Children with Disabilities: Reflections on The Journey , Sadeem A. Alolayan

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Students with Disabilities in Higher Education , Yanlys De La Caridad Palacios

High School Teachers’ Perceptions of Promoting Student Motivation and Creativity through Career Education , Kyeonghyeon Park

The Specifics of Specific Learning Disability: An Analysis of State-Level Eligibility Criteria and Response to Intervention Practices , Lora M. Williams

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Saudi Early Childhood Educators' Perceptions of Gender Roles in Children's Dramatic Play , Dalal Alanazi

Barriers to Reducing the Assistive Technology use for Students with Autism as Perceived by Special Education Teachers in Saudi Arabia , Othman Ahmed Alasmari

Saudi Teachers’ Perspectives on Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Specifically Designed for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder , Ahmad Saad Alghamdi

Perceptions of Preservice Teachers of Students with Intellectual Disabilities About their Preparation for Inclusive Education , Abdullah Aljudaya

Experiences of Saudi Arabian Mothers of Young Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Study , Samirah Bahkali

Persistence Like a Mother: Nursing the Narrative toward Doctoral Completion in English Education—A Poetic Autoethnography , Krista S. Mallo

Warming Up and Cooling Down: Perceptions and Behaviors Associated with Aerobic Exercise , Balea J. Schumacher

A Multimodal Literacy Exploration: Lived Experiences of Haitian Immigrant Adolescent Girls in The Bahamas , Natasha Swann

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

Perceptions of Preservice Teachers of Students with Autism and Intellectual Disabilities in their Teacher Preparation Programs in Saudi Arabia , Salman Almughyiri

Mapping Narrative Transactions: A Method/Framework for Exploring Multimodal Documents as Social Semiotic Sites for Ethnographic Study , Anne W. Anderson

The Effects of Augmented Reality (AR)-infused Idiom Material on Iranian Students’ Idiom Achievements, Motivation, and Perceptions , Babak Khoshnevisan

An Examination of Changes in Muscle Thickness, Isometric Strength, and Body Water Throughout the Menstrual Cycle , Tayla E. Kuehne

How the Use of Learner-Generated Images and Authentic Materials Affects the Comprehension and Production of Vivid Phrasal Idioms in L2 English Learners , Melissa Larsen-Walker

Explore L2 Chinese Learners' Motivation through L2MSS: Selves, Mental Imagery, and Pedagogical Implications , Yao Liu

Exploring Adult Indigenous Latinxs’ English Language Identity Expressions and Agency: A MALP®-informed Photovoice Study , Andrea Enikő Lypka

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

The Use of Assistive Technology with Students with Severe Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities in Saudi Arabia: Teachers’ Perspectives , Khalid Mohammed Abu Alghayth

Saudi Special Education Preservice Teachers’ Perspective towards Inclusion , Sarah Binmahfooz

The Teacher Evaluation Conundrum: Examining the Perceptions of Special Education Teachers , Gordon Brobbey

Illuminating Changes in Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions about Teaching Elementary Mathematicsin an Introductory Methods Course , Elaine Cerrato

International Teaching Assistants’ Perceptions of English and Spanish Language Use at the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez , Edward G. Contreras Santiago

Psychological Responses to High-Intensity Interval Training Exercise: A Comparison of Ungraded Running and Graded Walking , Abby Fleming

The Effects and Students’ Views of Teachers' Coded Written Corrective Feedback: A Multiple-Case Study of Online Multiple-draft Chinese Writing , Jining Han

Autism and Inclusion in England’s Multi Academy Trust: A Case Study of a Senior Leadership Team , Danielle Lane

Promoting L2 Idiomatic Competence among Chinese College Students via WeChat , Zhengjie Li

EFL Student Collaborative Writing in Google Docs: A Multiple Case Study , Quang Nam Pham

Threats to Teaching: An Investigation Into the Constructs of Compassion Fatigue in the Classroom , April M. Steen

A New Literacy Coach and Two English Language Arts Teachers Learn Together: A Narrative Inquiry , Christiana C. Succar

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

General Education Teachers’ Perceptions of Response to Intervention Implementation: A Qualitative Interview Study , Adhwaa Alahmari

A Study of Ghanaian Kindergarten Teachers' Use of Bilingual and Translanguaging Practices , Joyce Esi Bronteng

Deaf Lesbian Identity , Noël E. Cherasaro

Beyond Replicative Technology: The Digital Practices of Students with Literacy-Related Learning Difficulties Engaged in Productive Technologies , Aimee Frier

Once Upon a Genre: Distant Reading, the Newbery Medal, and the Affordances of Interdisciplinary Paradigms for Understanding Children’s Literature , Melanie Griffin

Learning in the Margins: The Educational Experiences of an African American Male with Disabilities , Aisha Holmes

Including children with learning differences: Experiences of independent school teachers , Lisa M. Lockhart

The Effects of Music Choice on Perceptual and Physiological Responses to Treadmill Exercise , Taylor A. Shimshock

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Perceptions of Arab American Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Exploratory Study , Haifa Alsayyari

It’s Not All Sunflowers and Roses at Home: A Narrative Inquiry of At-Risk Girls and Their Perceptions of Their Educational Experiences , Jessica Aggeles Curtis

Exploring Mathematics Teacher Education Fieldwork Experiences through Storytelling , Melody Jeane Elrod

Improving Reading Comprehension of Children with ASD: Implication of Anaphoric Reference Support with Computer Programming , Seda Karayazi Ozsayin

A Qualitative Content Analysis of Early Algebra Education iOS Apps for Primary Children , Lissa S. Ledbetter

Cultivating Peace via Language Teaching: Pre-Service Teachers' Beliefs and Emotions in an EFL Argentine Practicum , María Matilde Olivero

Collaboration with Families: Perceptions of Special Education Preservice Teachers and Teacher Preparation , Mehmet Emin Ozturk

Perspectives of AP U.S. History Teachers in Title I Schools , Mark Lance Rowland

What Does It Mean to Be a Service-Learning Teacher? - An Autoethnography , Kristy Causey Verdi

Early Childhood Mathematics Through a Social Justice Lens: An Autoethnography , Jennifer Ward

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

Urban English Language Arts Teachers’ Stories of Technology Use: A Narrative Inquiry , Bridget Abbas

Teachers’ Third Eye: Using Video Elicitation Interviews To Facilitate Kuwaiti Early Childhood Preservice Teachers’ Reflections , Hessa Alsuhail

Foreign Language College Achievement and the Infusion of Three Selected Web 2.0 Technologies: A Mixed Method Case Study , Eulises Avellaneda

Emotional Self-Regulation: Voices and Perspectives of Teachers within Diverse Socio-Cultural Contexts , Anna Paula Peixoto Da Silva

The Effect of Exercise Order on Body Fat Loss During Concurrent Training , Tonya Lee Davis-Miller

Subtext of Decisions: Literacy Practices in the Context of Coding , Julia Hagge

The Role of Prep Schools in the Middle to High School Transition of Students in Southeastern Turkey , Mucahit Kocak

“It’s Not Pixie Dust”: An Exploratory Qualitative Case Study of a School-Based Multimodal Tablet Initiative , Erin Elizabeth Margarella

Influence of Language Arts Instructional Practices on Early Adolescents’ Motivation to Read: Measuring Student and Teacher Perceptions , Sarah E. Pennington

Educators' Oral Histories of Tampa Bay Area Writing Project Involvement , Margaret Hoffman Saturley

Anti-Fat Attitudes and Weight Bias Internalization: An Investigation of How BMI Impacts Perceptions, Opinions and Attitudes , Laurie Schrider

Use of a Game-Based App as a Learning Tool for Students with Mathematics Learning Disabilities to Increase Fraction Knowledge/Skill , Orhan Simsek

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Examining Experiences of Early Intervention Providers Serving Culturally Diverse Families: A Multiple Case Study Analysis , Wendy Lea Bradshaw

"I want to be the Sun": Tableau as an Embodied Representation of Main Ideas in Science Information Texts , Margaret Branscombe

A Case Study of Teachers' in Professional Learning Communities in a Campus Preschool , Victoria Jacqueline Damjanovic

Student-teacher Interaction Through Online Reflective Journals in a High School Science Classroom: What Have We Learned? , Megan Elizabeth Ehlers

Novice Teachers' Stories of Solving Problems of Practice , Yvonne Franco

Facilitating Motivation in a Virtual World Within a Second Language Acquisition Classroom , Andrew Warren Gump

IWitness and Student Empathy: Perspectives from USC Shoah Foundation Master Teachers , Brandon Jerome Haas

Precalculus Students' Achievement When Learning Functions: Influences of Opportunity to Learn and Technology from a University of Chicago School Mathematics Project Study , Laura A. Hauser

The Role of the Interruption in Young Adult Epistolary Novels , Betty J. Herzhauser

A Conceptual Analysis of Perspective Taking in Support of Socioscientific Reasoning , Sami Kahn

Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors as Strengths, not Weaknesses: Evaluating the Use of Social Stories that Embed Restricted Interests on the Social Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder , Maya Nasr

Job Satisfaction of Adjunct Faculty Who Teach Standardized Online Courses , Claudia A. Ruiz

Relationships between the Algebraic Performance of Students in Subject-Specific and Integrated Course Pathways , Derrick Saddler

The Common Core State Standards: Its Reported Effects on the Instructional Decision Making of Middle School Social Studies Teachers , Tracy Tilotta

The Influence of Types of Homework on Opportunity to Learn and Students' Mathematics Achievement: Examples from the University of Chicago School Mathematics Project , Yiting Yu

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Picturing the Reader: English Education Pre-service Teachers' Beliefs About Reading Using Photovoice , Michael Dicicco

The Effect of Music Cadence on Step Frequency in the Recreational Runner , Micaela A. Galosky

Balanced Artistry: Describing and Explaining Expert Teacher Practice as Adaptive Expertise , Nina Graham

The Fight Within: Experiences of School District Employees Who Advocate for the Rights of Their Own Children with Disabilities Inside the Districts Where They Work, a Heuristic Case Study , Keri Haley

A Phenomenological Study of the Experiences of Higher Education Students with Disabilities , Allen J. Heindel

Constructing an "Appropriate" Education in Florida Special Education Due Process Final Orders , Michelle Henry

The Effect of Teachers' Epistemological Beliefs on Practice , Milton David Huling

Perceptions, Beliefs and Practices about Technology among Teachers in a Jamaican Infant School , Suzette Anissia Kelly

"Choosing My Words Carefully": Observing, Debriefing, and Coaching Four Literacy Teachers' Through Their Lessons , Iveta Maska

Presentation of Civic Identity in Online High School Social Studies Discussion Forums , Holly Mcbride

In Our Image: The Attempted Reshaping of the Cuban Education System by the United States Government, 1898-1912 , Mario John Minichino

The Hypertrophic Effects of Practical Vascular Blood Flow Restriction Training , John Francis O'halloran

Science Teachers' Understandings of Science Practices before and after the Participation in an Environmental Engineering Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) Program , Dilek Özalp

The Effects of Emotive Reasoning on Secondary School Students' Decision-Making in the Context of Socioscientific Issues , Wardell Anthony Powell

Interagency Collaboration for the Provision of Services to Migrant Children with Disabilities: An Exploratory Study , Georgina Rivera-Singletary

Reflections in the Classroom: Perspectives on Teaching for Social Justice from Secondary Social Studies Educators , Gregory Lee Samuels

A Case Study of the Roles and Perceptions of Writing Coaches , Amy June Schechter

Genres of Children's Websites: A Comprehensive Methodology for Analyzing Digital Texts , James L. Welsh

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

Attitude Toward Digital and Print-Based Reading: A Survey for Elementary Students , Diedre D. Allen

Playing in Trelis Weyr: Investigating Collaborative Practices in a Dragons of Pern Role-Play-Game Forum , Kathleen Marie Alley

Curriculum Gatekeeping in Global Education: Global Educators' Perspectives , Robert Wayne Bailey

Reading Assessment Practices of Elementary General Education Teachers: A Descriptive Study , Sarah Mirlenbrink Bombly

Advanced Search

- Email Notifications and RSS

- All Collections

- USF Faculty Publications

- Open Access Journals

- Conferences and Events

- Theses and Dissertations

- Textbooks Collection

Useful Links

- Rights Information

- SelectedWorks

- Submit Research

Home | About | Help | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Language and Diversity Statements

Privacy Copyright

Advertisement

Approaches to teaching in higher education: the perspective of network analysis using the revised approaches to teaching inventory

- Open access

- Published: 22 September 2021

- Volume 84 , pages 255–277, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Velibor Mladenovici 1 na1 ,

- Marian D. Ilie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4807-5258 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Laurențiu P. Maricuțoiu 1 , 3 na1 &

- Daniel E. Iancu 1

13k Accesses

13 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Over time, the academics’ approaches to teaching (i.e., content- or learning-focused approach) were intensively studied. Traditionally, studies estimated the shared variance between the items that describe a behavioral pattern (i.e., the psychometric approach), defined as a learning- or content-focused approach to teaching. In this study, we used a different perspective (i.e., network analysis) to investigate academics’ approaches to teaching. We aimed to bring in new insights regarding the interactions between the elements that define academics’ approaches to teaching. We used the Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory to collect responses from 705 academics (63.97% female) from six Romanian universities. The main results indicated that academics’ conceptions about the subject matter are central to their preferences concerning the adoption of a content-focused or a learning-focused approach to teaching. The estimated network is stable across different sub-samples defined by the academic disciplines, class size, academics’ gender, and teaching experience. We highlighted the implications of these findings for research and teaching practice in higher education. Also, several recommendations for developing pedagogical training programs for academics were suggested. In particular, this study brings valuable insights for addressing academics’ conception about the subject matter and suggests that this could be a new topic for pedagogical training programs dedicated to university teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Know-who linking faculty’s networks to stages of instructional development.

Teaching and learning high-school mathematics via WhatsApp: teachers’ perspectives

Promoting educational innovations and change through networks between higher education teachers

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the main challenges of higher education institutions is to ensure that academics’ approaches to teaching influence effective students’ approaches to learning (e.g., a deep approach to learning). A deep learning approach involves meaningful engagement in the learning process and understanding of the subject matter (Asikainen & Gijbels, 2017 ). On the contrary, the surface learning approach is undesirable because it involves unreflective studying practices (i.e., memorization and focus on reproducing the learning material) (Asikainen & Gijbels, 2017 ).

Empirical evidence showed that academics’ approaches to teaching can influence the way students approach their learning (Entwistle, 2009 ; Kember & Gow, 1994 ; Trigwell et al., 1999 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ). When academics use a learning-focused approach to teaching, students are more likely to adopt deeper learning approaches, as compared with the cases when academics use content-focused approaches (e.g., Ho et al., 2001 ; Trigwell et al., 1999 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ). In other words, teachers’ behavior is important because it facilitates students’ learning through a student-centered approach. Therefore, academics should have advanced knowledge regarding the initiation and the guidance of students’ learning processes. However, research has shown that the academics’ choice of a particular approach to teaching could be explained based on their conceptions of teaching or based on their understanding of the subject matter (e.g., Kember, 1997 ; Prosser et al., 2008 ). For this reason, it becomes imperative for academics to be aware of how they understand the subject matter taught, about their teaching approach, and how these variables influence students’ learning process. Thus, research on these subjects could provide relevant information for stimulating academics towards adopting a student-centered approach, which represents one of the most important aims of the pedagogical training programs dedicated to academics (Hicks et al., 2010 ).

Research evidence emphasized the importance of pedagogical training programs in helping academics increase their pedagogical awareness (e.g., Postareff et al., 2008a ). Studies have shown that these programs have a positive impact on the academics’ conception of teaching (e.g., Ginns et al., 2008 ; Ho et al., 2001 ; Kember, 1997 ), can help academics to make the transition from a content-centered approach towards a more learning-centered approach to teaching (Gibbs & Coffey, 2004 ; Postareff et al., 2007 ; Stes et al., 2010a ; Stewart, 2014 ; Trautwein, 2018 ; Vilppu et al., 2019 ), and can improve academics’ reflection skills and habits (Karm, 2010 ; Nevgi & Löfström, 2015 ) as well as academics’ self-efficacy (Noben et al., 2021 ). However, a recent meta-analysis on pedagogical programs for academics showed that the current practices have only a small effect on academics’ outcomes ( d = 0.315, Ilie et al., 2020 ). Thus, even if approaches to teaching have been extensively investigated, more research is needed on this topic to highlight relevant training subjects and ensure a more effective practice for academic development.

Traditionally, the investigation of human behavior is dominated by the latent factor perspective (Sava, 2004 ). Based on this perspective, researchers assumed that teachers’ behaviors could be explained by latent variables that capture their shared variance. For example, the academic approaches to teaching have been investigated in relation to the factorial structure of different versions of Approaches to Teaching Inventory (Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a ; Trigwell & Prosser, 2004 ; Trigwell et al., 2005a ). Using this perspective, researchers can identify the teaching approach adopted by their respondents (i.e., content- or learning-focused). The network analysis perspective is a new alternative approach that can be used to explain the shared variance between teaching behaviors. Unlike the traditional assumption of the latent factor perspective, network analysis assumes that observed correlations between the behaviors that describe the phenomenon (i.e., approaches to teaching) are due to mutual influences between each other (Fonseca-Pedrero, 2017 ). By changing our perspective on the teaching behaviors (i.e., focus on the relationships between the various intentions and strategies interdependently and not interchangeably like in the latent variables approach), we could bring new insights for the understanding of academics’ teaching approaches. Thus, we can identify strategies or intentions that are most weighty (i.e., are central in the network) in shaping (or adopting) a specific approach to teaching in higher education. The information offered by the network perspective could advance relevant topics for pedagogical training programs dedicated to academics.

This study aimed to identify the central elements of the network that may activate or deactivate the complex network of academics’ intentions and conceptions that constitute their approaches to teaching. To achieve this aim, we used the network analysis perspective on responses to the Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory (R-ATI, Trigwell et al., 2005b ). We began by presenting current information about teaching approaches in higher education and the network psychometric approach. Then, we presented the design, the procedures, and the results of our study. Further, we discussed our findings and advanced several recommendations for academic development practice and future research in the field. Additionally, we presented details on the translation and adaptation of the R-ATI (Trigwell et al., 2005a ) in the Romanian context.

Teaching approaches in higher education

The teaching approach is defined as “a combination between one’s intention of teaching and teaching strategy” (Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a , p. 78). Because teaching approaches and conceptions of teaching have been found to correlate (Eley, 2006 ; Kember & Kwan-Por, 2000 ), conceptions of teaching are considered to represent the basis for teaching practices (Gow & Kember, 1993 ). In this vein, academics with a particular conception of teaching are inclined to have specific intentions, which lead to corresponding teaching strategies (Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a ; Kember & Kwan-Por, 2000 ). The investigation of academics’ teaching intentions and strategies is of particular importance for increasing the quality of higher education. Research has shown that those correlate with the student learning approach (Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ; Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2008 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ).

Teaching intentions were found to range from one in which the teacher wants to transmit the content of the subject to the student to one in which the teacher aims to help students’ change their conceptions of the content (Trigwell et al., 1994 ). Consequently, teaching approaches in higher education could be classified into two broad categories: learning-focused or content-focused approaches to teaching (Kember & Kwan-Por, 2000 ). Previous studies have used various terminology when defining the two main teaching approaches. For example, some studies used “student-focused” and “teacher-focused” (Prosser & Trigwell, 1999 ; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996b ) or “student-centered” and “teacher-centered” (Jacobs et al., 2020 ) while other studies utilized the “content-focused” and “learning-focused” terminology (Kember & Kwan-Por, 2000 ; Samuelowicz & Bain, 1992 ; Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2008 ). The present study uses the terminology learning-focused , student-centered , and learning-centered , as well as content-focused , content-centered , and teacher-centered approaches as interchangeable throughout the paper.

Teachers that use a content-focused approach to teaching consider teaching as a process of knowledge transmission. Thus, one of the main teaching strategies used by the academics in a content-focused approach is the presentation of their own knowledge of the subject matter (Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ). Such a teaching approach is undesirable because it is correlated with the students’ adoption of a surface approach to learning (Trigwell et al., 1999 ; Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ). On the other hand, academics who adopt a learning-focused approach to teaching intend to help students change and build their own conception of the subject matter (Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ). Therefore, academics employ teaching strategies that help students develop new ways of thinking through addressing their individual needs, through engagement in the learning process, and interaction (Postareff & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2008 ; Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ). The academics’ adoption of a learning-focused approach to teaching is desirable due to the existing correlation between such an approach to teaching and students’ adoption of a deep approach to learning (Prosser & Trigwell, 2014 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ).

Academics do not always employ a single approach to teaching and use elements from both approaches; this may be resulting in a dissonant teaching approach (Postareff et al., 2008b ; Stes & Van Petegem, 2014 ; Uiboleht et al., 2018 ). In this vein, previous studies also suggested that a dissonant teaching approach could be an intermediary step into the development process of teaching approach from a content-focused approach to a learning-focused approach (Postareff et al., 2008b ; Stes & Van Petegem, 2014 ). However, the relationship between an academics’ dissonant approach to teaching and students’ approaches to learning is not consistently supported by previous research. Initially, evidence suggested that when academics use a dissonant approach, students tend to adopt a surface approach to learning, and learning outcomes are slightly lower (Prosser et al., 2003 ). More recent evidence provided by Uiboleht et al. ( 2018 ) showed that using a dissonant approach to teaching does not always result in lower quality of student approaches and their learning outcomes.

The academics’ decision to adopt one or another from the abovementioned approaches to teaching could vary depending on different variables such as class size, study year (Lindblom-Ylänne et al., 2006 ), discipline (Nevgi et al., 2004 ), or teachers’ characteristics (e.g., gender, nationality, status, and experience; Prosser et al., 2003 ). For example, academics are more prone to adopt a content-focused approach as the class size and class level increase (Singer, 1996 ). Also, some studies (Lindblom-Ylänne et al., 2006 ; Lueddeke, 2003 ) came across the conclusion that teachers’ belonging to a “soft discipline” (Becher, 1989 ) (e.g., linguistics) or an “applied soft” (e.g., education) are more learning-centered in their teaching approach than teachers belonging to a “pure hard” discipline (e.g., mathematics) or to an “applied hard” discipline (e.g., medicine). There is also some effect of gender on teaching approaches, with men scoring significantly higher on the teacher-focused approach (Nevgi et al., 2004 ). In a study by Prosser et al. ( 2003 ), students who perceived the learning environment as of a higher quality reported a deep approach to learning, but there was also a significant difference between senior teachers and junior teachers’ approaches to teaching. These results were not confirmed by Stes et al. ( 2008 ), who reported insignificant differences regarding the learning-focused scale between classes with different sizes or between different study years. Moreover, these authors found no relationship between teachers’ characteristics (i.e., gender, teaching experience, age, academic status) and the teachers’ learning-focused approach. Consequently, more research is needed to conclude regarding the factors that may influence the variability of the approaches to teaching across different contexts. In this study, by using the network analysis perspective, we can investigate if the emergence of academics’ preference for an approach to teaching involves similar emerging processes regardless of the teachers’ or context-specific characteristics. Thus, given the results of previous studies, we investigated the stability of our network on subsamples based on academic’ gender, teaching experience, class size, and taught discipline.

The network psychometric approach

All research studies presented above used the latent variable models to investigate the teaching approaches. Latent variable models are traditionally used in research for the measurement of psychological attributes (Sava, 2004 ). These models are used to estimate the shared variance of the items that describe a particular behavioral pattern. For example, in the case of approaches to teaching, researchers developed items that described content- and learning-focused approaches and investigated how these items group in two- or four-factor solutions that explained the shared variance of the items. Recent approaches in the study of the complex psychological attributes both used and recommended “Network analysis” as being potentially better in terms of efficiency (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013 ; De Schryver et al., 2015 ). In educational research, the network analysis was used recently by Smarandache et al. ( 2021 ) to investigate the students’ approaches to learning.

Network psychometrics offers new perspectives regarding the shared variance of the item responses, which are viewed as interdependent variables that interact and reinforce each other. According to Constantini and Perugini ( 2017 ), there are three main ways in which the network analysis brings new perspectives on the phenomenon. We will describe in the case of teaching approaches. Firstly, the network perspective assumes that a particular teaching approach results from the interactions between the behaviors that describe it. Therefore, the covariance of the components (or the behaviors) of a particular teaching approach is understood as evidence of interactions between these components. Secondly, components have different roles in the emergence (or activation) of the entire network of complex behaviors. Finally, the network perspective assumes that some elements are more important (i.e., are more central) for the emergence of teaching approaches, while other elements are peripheral. This means that opting for a particular teaching approach can be understood as a result of some particular behaviors that define that approach, while other behaviors are less important.

In the case of academics’ approaches to teaching, the network analysis approach will focus on the relationship between the various intentions and strategies (i.e., inter-dependency) and will not treat them as interchangeable (i.e., like in the latent variables approach). By using network analysis and implicitly by comparing the intentions and strategies that describe the preference for a particular teaching approach, the role of variables within the network can be observed more precisely. More exactly, the network approach provides evidence on the weakest and the strongest relations between the elements that constitute a preference for a particular teaching approach. In our case, the network analysis could compare the relations between the intentions and strategies of adopting a content−/teacher-focused approach with intentions and strategies of adopting a learning−/student-focused approach to teaching. Therefore, using a network perspective, we could check if there are any central activators (e.g., either only content-focused intentions or strategies, either learning-focused intentions or strategies, either from all) for the entire network.

The present study

In the present study, we used the network psychometric approach to analyze academics’ approaches to teaching. Our main objective was to identify the central elements of the network that may activate or deactivate the complex network of intentions and conceptions that constitute the academics’ approaches to teaching. Also, we investigated the stability of this network considering four variables: the specific of the discipline, the class size, the influence of the teachers’ gender, and the teaching experience.

Over time, several quantitative instruments were developed for the assessment of teachers’ conceptions and approaches to teaching. These scales include the 22-item Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a ); the 16-item ATI (Trigwell & Prosser, 2004 ); the 22-item Revised-ATI (Trigwell et al., 2005a ); the Instruction Preference Questionnaire (IPQ, Hativa & Birenbaum, 2000 ); and the Teacher Beliefs Survey (TBS, Woolley et al., 2004 ). Of all these tools, the ATI (Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a ) is the most cited tool and had been extensively used, being adapted and validated on many different populations (Harshman & Stains, 2017 ). Anyway, like any other instruments, ATI has been criticized by some authors for its conceptual underpinnings and development (Eley, 2006 ; Harshman & Stains, 2017 ). Over time, to improve it, ATI’s authors developed several versions of the inventory (e.g., Trigwell & Prosser, 1996a , 2004 ; Trigwell et al., 2005b ). These versions of ATI were effectively used in many studies (e.g., Postareff et al., 2007 , 2008a ; Stes et al., 2010a ), and almost all the validation studies have shown good reliability results (e.g., China (Zhang, 2001 ); Dutch (Stes et al., 2010b )).

Considering the most recent finding, there is greater evidence for better psychometric properties (i.e., internally consistent and fit statistics) for the R-ATI with 22 items than the 16-item ATI (Harshman & Stains, 2017 ). For this reason, in the present study, we use the R-ATI version with 22 items (Trigwell et al., 2005a ).

Participants

The Center of Academic Development (CAD) of the West University of Timişoara (WUT) offers yearly pedagogical training programs for academics from within the WUT and other Romanian university partners. The impact of each CAD activity is assessed, and this involves the participation of CAD beneficiaries (i.e., academics) and their students. Participation in the activities as well as in the impact assessment process is voluntary. Therefore, between September 2017 and March 2020, at the beginning of each training activity, all the academics that attended the CAD programs were asked to complete the paper-and-pencil form of the Romanian version of R-ATI (Trigwell et al., 2005b ). Before completing the questionnaire, one research team member read to the participants one standard procedure to fill out the questionnaire (i.e., informed consent, data anonymity, etc.). It was mentioned that the academics must refer to their teaching approaches adopted at one specific discipline (i.e., one of the disciplines they teach at the moment). Following the World Medical Association Helsinki declaration and the minimal risk nature of the study, no ethical board approval was required.

Our sample, as presented in Table 1 , was a convenience sample and consisted of a total of 705 in-service academics (63.97% female, mean age = 40.4) from six Romanian universities. Regarding teachers’ specializations, we used Becher’s classification and we grouped them as follows: “pure hard” (i.e., Chemistry, Biology, Geography, Mathematics, and Informatics); “applied hard” (i.e., Medicine); “pure soft” (i.e., Linguistics, History, and Theology); and “applied soft” (i.e., Law, Administrative Sciences, Economy and Business Administration, Physical Education and Sports, Social Sciences, Philosophy, and Communication Sciences) (Becher, 1989 ).

We used R-ATI (Trigwell et al., 2005b ) to investigate the teaching approach. The R-ATI contains two main scales (i.e., “conceptual change/student-focused” (CCSF) and “information transmission/teacher-focused” (ITTF)) and two subscales (i.e., intentions and strategies) into each of it. The CCSF scale describes teaching intentions and strategies that focus on the student intended to enhance their understanding of the subject matter. The ITTF scale describes a teacher−/knowledge-focused approach in which teachers are concentrated on what they do in teaching and on the content to be taught. The R-ATI has 22 items and respondents must assess each item using a 5-point Likert scale (from never/only rarely true of me to always/almost always true of me ). Details regarding the adaptation of R-ATI are presented in the First Supplemental Material .

Data analysis

The main data analysis involved the use of several R packages to analyze our dataset. We followed the recommendations provided by Constantini and Perugini ( 2017 ) for conducting network analysis. Therefore, we had four steps: network estimation (i.e., estimation of the Graphical Gaussian Model), node centrality (i.e., estimation of the importance of each R-ATI item), network stability (i.e., we bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for all edges and all centrality indices), and network replication (i.e., we compared the networks of subsets of participants). This procedure is similar to the approaches followed by Fried et al. ( 2018 ) and Smarandache et al. ( 2021 ).

Because R-ATI responses are on an ordinal scale, we estimated the network using the Graphical Gaussian Model available in the qgraph package (Epskamp et al., 2012 ). Graphical representations of the estimated networks display partial correlations between any pair of R-ATI items, while controlling for the variance of all other items. In the graphical representations, thicker lines represent stronger partial correlations, while the direction of the relationship was represented by colors (i.e., red lines for negative relations). Because most partial correlations have very small values, we simplified the interpretation of our network using the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) (Friedman et al., 2008 ), with the extended Bayesian Information Criterion model (EBIC) selection (Foygel & Drton, 2010 ). This approach replaces the small correlation values with the value zero, while allowing for an optimal ratio between false-positive decisions (i.e., correlations that should be removed) and true-positive decisions (i.e., correlations that should not be removed). Next, we used the qgraph (Epskamp et al., 2012 ) to compute and to plot the centrality indices for all nodes. In the third stage, we estimated the stability of our network using the bootstrapping procedures implemented by bootnet R package (Epskamp et al., 2018a ). Finally, we compared the networks of subsets of participants using the NetworkComparisonTest R package (van Borkulo et al., 2017 ).

Network estimation

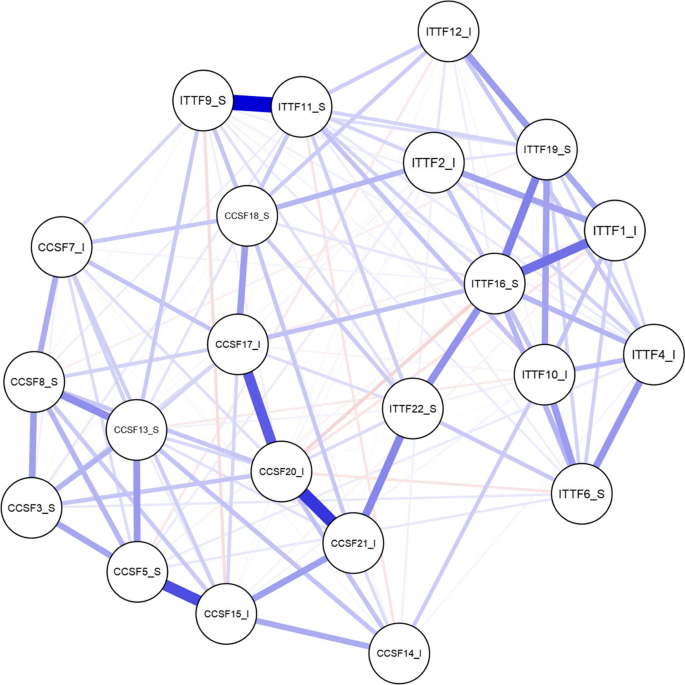

The descriptive statistic of the variables of the R-ATI is presented in Table 2 . The network based on the partial correlations between all R-ATI items is presented in Fig. 1 . We found that the teacher-focused approach involved strong relationships between two teacher-focused strategies which have a formal assessment as the main goal (i.e., items ITTF9 and ITTF11) and strong associations between teacher strategies regarding the efficient transmission of information (i.e., items ITTF1, ITTF16, and ITTF19). Regarding the student-focused approach, the strongest relationships were found in the case of teacher intentions regarding helping students to build their understanding of the discipline (i.e., items CCSF17, CCSF20, and CCSF21), and in the case of teachers’ intentions regarding development of students’ ideas (i.e., items CCSF5 and CCSF15).

Network of approaches to teaching. Note: Network representation using the EBICgLasso algorithm

Node centrality indices

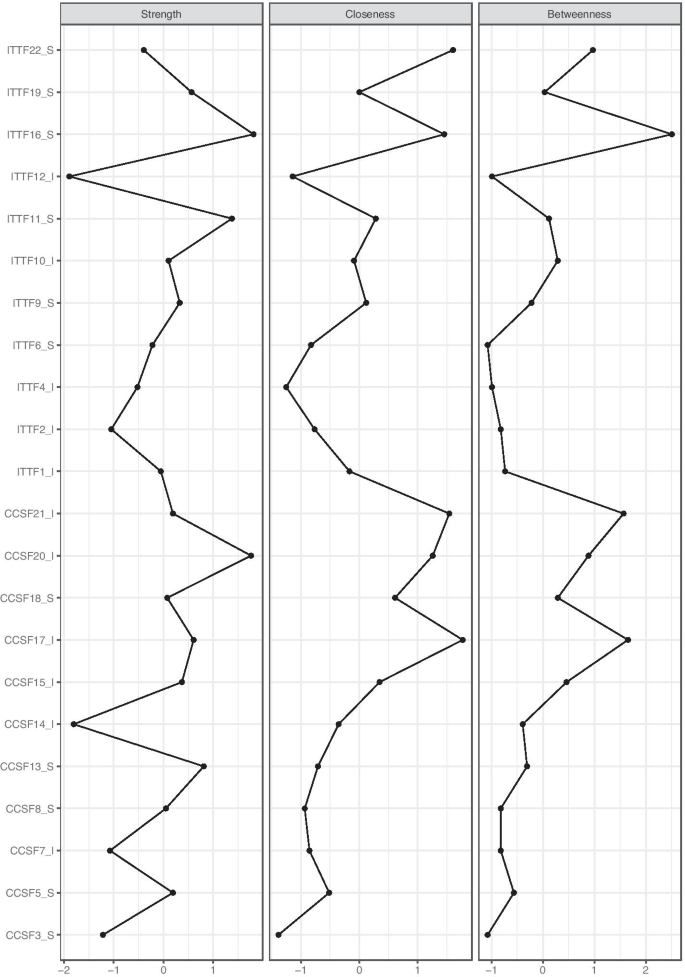

Because the items are grouped based on their content (i.e., teacher-focused and student-focused), the items that bridge these two hemispheres are most important. In this case, the analysis focused on the investigation of the centrality indices of each item. We calculated three centrality measures (i.e., strength, closeness, and betweenness) for each item (or network node), and their standardized values are presented in Fig. 2 . The most central node is a teacher-focused item (i.e., item ITTF16— In this subject, my teaching focuses on the good presentation of information to students ), which had the highest values on two of the centrality indices (i.e., strength and betweenness). The second node in terms of centrality importance is an item that describes an intention of student-focused teaching (i.e., item CCSF20— Teaching in this subject should help students question their own understanding of the subject matter ). Another student-focused teaching central to this network is item CCSF17 ( I see teaching as helping students develop new ways of thinking in this subject ). The third node in terms of centrality importance is a strategy focused on content (i.e., item ITTF11— In this subject, I provide the students with the information they will need to pass the formal assessments ). Altogether, centrality indices of the present study underline the importance of the focus on presenting good information , facilitation of student self-reflection and providing students with the information they need to pass the formal assessments as key elements in understanding the teaching approaches network.

Standardized centrality indices for the EBIC graphical LASSO network, for all items of the R-ATI

Network stability

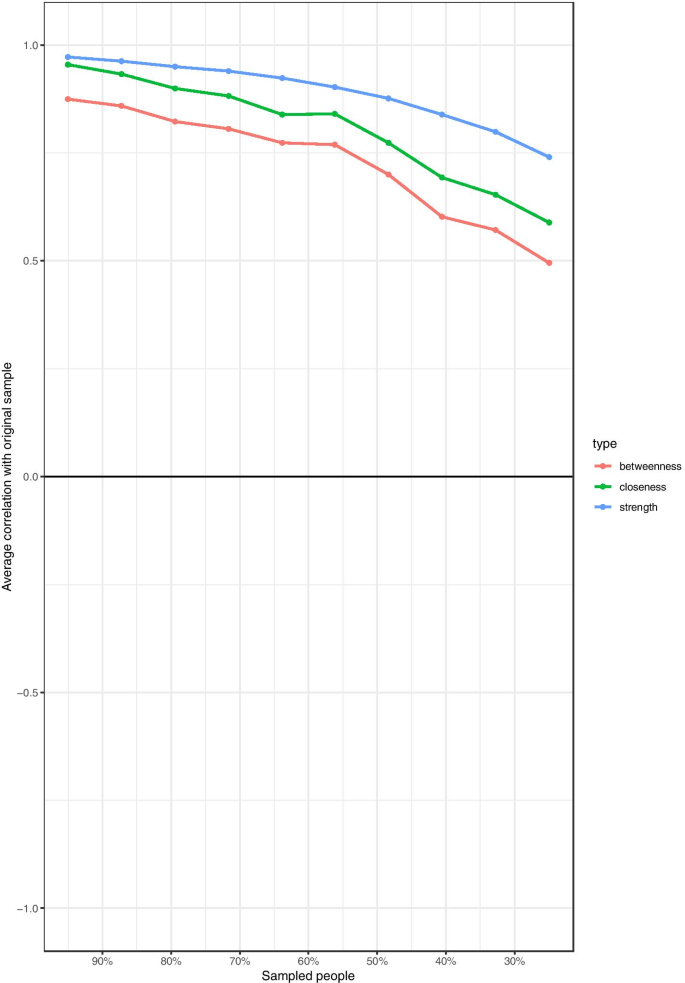

We used bootstrapping procedures to estimate the stability of our previous findings (Hevey, 2018 ). Using the R bootnet package (Epskamp et al., 2018b ), we estimated the accuracy of all partial correlations (i.e., for each partial correlation, we computed the 95% confidence interval). The partial correlation estimates and the associated 95% confidence interval plotted in Fig. 3 indicated that all partial correlation values are close to the estimated bootstrap mean.

Bootstrapped confidence intervals of estimated edge weights. Note: The black line indicates the bootstrapped mean values of the confidence interval, the red line indicates the sample values, and the gray area the 95% confidence intervals

Next, we examined the stability of the centrality indices using the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2018 ). In this case, we used a case-dropping bootstrap that estimates the centrality indices on subsamples of the original dataset and correlated these new values with the original (or full-sample) value. Our analyses re-estimated these indices on 100 subsamples with diminished sizes of up to 75% (i.e., subsamples that included only 25% of the original responses). Results indicated that our centrality indices are stable: all three centrality indices of the subsamples (i.e., betweenness, closeness, and strength) will still correlate at r = .70 with the initial values, even if we drop 51.6% of our sample. This value is within the range suggested by Epskamp and Fried et al. ( 2018 ), who concluded that drop percentages above 50% indicate good stability of the centrality indices. The most precisely estimated centrality index is Strength which even if we drop 67.2% of our sample, will still correlate at r = .70 (Fig. 4 ).

Centrality stability of the network

Network replicability

Because previous research suggested that teaching approaches are related to various demographics (e.g., teachers’ gender, teaching experience) or context-related variables (e.g., class size, academic discipline), we investigated whether our network is replicable in different contexts. Using the NetworkComparisonTest package (van Borkulo et al., 2017 ), we estimated different networks for each subsample (e.g., male and female academics). The NetworkComparisonTest package (van Borkulo et al., 2017 ) provides three indices of network replicability: the correlation between the edges of the two networks, the number of statistically different edges from one network to another, and the correlation between the stability indices of each item (i.e., estimated in each network).

Firstly, we investigated whether the network estimated on a male subsample ( N = 201) is similar to the network estimated on a female subsample ( N = 451). We found that the values of the edges in these two networks are correlated (ρ = .44), with no edges being significantly different from one network to another. The centrality indices of the two networks are also correlated (ρ = .45). Thus, we can conclude that the network is similar in both gender-based subsamples.

Secondly, we grouped our respondents into two groups based on their teaching experience (i.e., more and less than five years). The edges of the two networks were correlated (ρ = .55), with no edges being significantly different from one network to another. The centrality indices of the two networks are also correlated (ρ = .68). As in the case of gender sub-samples, in the case of teaching experience sub-samples, we can conclude that the network is similar.

Thirdly, we investigated whether the network is replicable across the class size (< 30 students and > 30 students). We also found similar network solutions in both groups (i.e., the values of the edges in these two networks are correlated at ρ = .50, the centrality indices are also correlated at ρ = .51, and none of the edges were significantly different from one network to another).

Finally, we grouped our respondents into four groups based on the taught discipline (i.e., pure hard, applied hard, pure soft, and applied soft specializations) (Becher, 1989 ). We estimated different networks for each category, and we conducted pairwise comparisons. Our results suggested that the four networks are similar in terms of centrality indices (i.e., the correlation values of their centrality indices are ρ > .65) and in terms of edge strengths (i.e., 95% of the edges were not statistically different).

Recent theoretical and methodological developments in psychology put forward a new paradigm that assumes that the covariances between human behaviors can be interpreted using a network perspective (Epskamp et al., 2018a ; Constantini & Perugini, 2017 ). Thus, we used network analysis and examined the relationships between academics’ teaching intentions and strategies by estimating a graphical LASSO network of R-ATI items (Trigwell et al., 2005a ). We investigated how the teacher-focused or student-focused teaching approaches are connected and identified two central nodes (i.e., ITTF16 and CCSF20) that are negatively associated, one for each teaching approach. A commonality of the two items seems to be the subject matter. On the one hand, the academics emphasize the need for “good presentation of information” regarding the subject matter. On the other hand, endorsements of this statement are associated with the rejection of the idea that students should “question their own understanding of the subject matter.” This central place of the subject matter is not surprising. Previous studies (Prosser et al., 2008 ; Trigwell & Prosser, 2020 ) showed a moderately strong relationship between teachers’ understanding of the subject matter and their teaching approaches. For example, teachers who are more focused on overall conceptual understanding and development (i.e., have a holistic understanding of the subject matter) are more likely to adopt a learning-centered approach to teaching than teachers focused on individual isolated problems (i.e., on the parts of the subject matter) (Prosser et al., 2008 ).

We found that focusing on the good transmission of information is negatively associated with the idea that students should question their understanding of the subject matter. The negative correlation between these two teaching strategies indicated that most of our sample academics prefer only one of these strategies. According to the network perspective, teachers’ preferences for only one of these two strategies will activate the network of behaviors specific to that teaching approach and will deactivate the network of behaviors specific to the other teaching approach. Consequently, the entire network will be activated, and we will observe a preference for a content-centered approach to teaching (in the case of Transmitting knowledge teaching conceptions ) or a preference for a learning-centered approach (in the case of Changing students’ understanding ) . Therefore, it is possible that academics that display a dissonant teaching approach do not see these two strategies as mutually exclusive: one can be effective in transmitting information to students and simultaneously encourage them to question their understanding of the subject matter. In previous studies, there is a broad agreement regarding dissonant teaching approaches as intermediary teaching profiles between content-focused approach and learning-focused approach (Postareff et al., 2008a ; Stes & Van Petegem, 2014 ). Thus, our finding is particularly important because it indicates which could be the first instructional suggestion (i.e., encourage students to address questions) to stimulate a dissonate teaching approach as an intermediary step towards the desirable learning-centered approach to teaching. Trigwell and Prosser ( 1996a ) advanced a similar idea highlighting that academics with a more learning-centered conception of teaching saw questions as an important part of their teaching approach. On the opposite side, academics who adopt more content-centered conceptions of teaching saw questions as an irrelevant instructional strategy.

From a network perspective (Constantini & Perugini, 2017 ), the academics’ conceptions towards the subject matter activate the central nodes, and will activate other nodes directly, which will activate other nodes. Regarding the nodes that have the strongest relations with the central nodes, there are two different shades. In the context of the content-centered approach, the items continue to reflect the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter (i.e., ITTF1—student should focus their study on what the teacher provides them —and ITTF19—the teachers’ teaching focuses on delivering what he/she knows to the students ). On the other hand, the nodes for the learning-centered approach show teachers’ intentions to help students to learn (i.e., CCSF21 —teaching should include helping students find their own learning resources —and CCSF17— teaching should be seen as a way of helping the student develop new ways of thinking ), suggesting teaching strategies based on teacher–student interaction. This could indicate that content- or learning-centered approaches to teaching might result from a content-to-interaction ratio: if the subject matter is viewed as something that must be memorized and/or retained, then teachers are more likely to adopt a content-centered approach to teaching, while if they understand the subject matter as a means to contribute to students’ intellectual development/conceptual change, then they are more likely to interact with students and, consequently, adopt a learning-centered approach to teaching. To some extent, these results are consistent with the previous findings (e.g., Kember, 1997 ; Stes & Van Petegem, 2014 ; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996b ), which highlighted the role of interaction in adopting specific teaching approach. For example, Stes and Van Petegem ( 2014 ) concluded that even if content- and learning-centered approaches are distinct types of approaches to teaching, “they can also be seen as poles of a continuum as well” (Stes & Van Petegem, 2014 , p. 655). In this continuum, the intermediary phases are presented as dissonant approaches to teaching. Moreover, along this continuum, the progress from a content-centered approach to a learning-centered approach is sustained by more interaction between teacher and students, and students to students. Our results can neither confirm nor infirm the existence of a continuum of the teaching approaches but showed a possible role of the academics’ disposition to interact with their students for adopting a learning-centered approach to teaching. Moreover, our study completed previous research results by showing that the academics’ disposition to interact with their students is based on their own conception about the subject matter.

In our comparative analyses, we grouped our respondents using demographic characteristics or context-related characteristics and we obtained similar networks. Our results suggested that the emergence of academics’ preference for an approach to teaching involves similar emerging processes, regardless of the academic disciplines, class size, academics’ gender, and teaching experience. Therefore, any potential differences between these academic categories cannot be attributed to different emerging processes but to different situational clues that may activate or deactivate the network. Previous studies (Nevgi et al., 2004 ; Lueddeke, 2003 ; Prosser et al., 2003 ; Singer, 1996 ) mentioned that teaching approaches vary depending on context variables such as class size, academics’ gender, teaching experience, and specific of the discipline. On the other hand, other research studies reported opposite findings (e.g., Stes et al., 2008 ). Our study could complete this picture highlighting that regardless of their or contextual characteristics (e.g., class size, academics’ gender, teaching experience), academics decide to adopt a specific teaching approach (content or learning-centered) using a decision-making process based on a content-to-interaction ratio.

Implications for academic development practice

The main objective of university teachers’ pedagogical development programs is to stimulate academics towards adopting a consonant student-centered approach to teaching (Hicks et al., 2010 ). To achieve this aim, several previous studies highlighted that the focus of these professional development programs should be on changing university teachers’ conception of teaching (e.g., Postareff et al., 2008a ; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996b ), since changes in their instructional strategies are more likely after such conceptual changes (Ho et al., 2001 ; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996b ). Our results suggested that changing academics’ conception of the subject matter could be the first step to change academics’ conception of teaching. Thus, changing academics’ conception of the subject matter should be an important objective of pedagogical trainings dedicated to academics. Although Trigwell et al. ( 2005b ) advanced a similar call more than 15 years ago, a recent meta-analysis on studies investigating the effectiveness of pedagogical training for academics identified several initiatives that aimed to change academics’ conception of teaching, but none addressed changes in academics’ conception of subject matter (Ilie et al., 2020 ).

Previous research showed that academics’ conceptions of teaching change slowly, even if this process varies depending on academics’ teaching experience (e.g., Postareff et al., 2007 ; Postareff & Nevgi, 2015 ; Vilppu et al., 2019 ). Consequently, if aimed to change conceptions, pedagogical programs must be specifically designed for this cause. Thus, we advanced some suggestions to design programs aimed to change academics’ conceptions of subject matter. First, before developing such programs, one must clarify what it means to change academics’ conceptions of subject matter . In this vein, different theoretical frameworks (e.g., Prosser et al., 2005 , 2008 ; Trigwell et al., 2005b ; Visser-Wijnveen et al., 2009 ) could be chosen as referential. For example, Prosser et al. ( 2005 , 2008 ) proposed a five-point continuum for the experience of understanding the subject matter, ranging between focusing on the parts of the subject matter and focusing on the subject matter as a whole . The authors also reported moderately strong relations between academics’ understanding of subject matter and their teaching approach (Prosser et al., 2008 ).

Second, one could use lessons from previous pedagogical training to change academics’ conception of teaching (e.g., Ginns et al., 2008 ; Ho et al., 2001 ; Kember, 1997 ) to develop instructional models for changing academics’ conception about the subject matter. For example, Ho et al. ( 2001 ) used four theories of conceptual change and developed an instructional model for conceptual change programs with four main elements (i.e., self-awareness , confrontation , alternative conception , and commitment building ). After implementing one program based on this instructional model, Ho et al. ( 2001 ) reported positive results on changing academics’ teaching concepts.

Third, reflection seems to be a key instructional approach to change teachers’ conceptions (e.g., Ho et al., 2001 ). However, using reflection as an instructional approach in an effective way is not always as easy as it could seem (Chan & Lee, 2021 ; McAlpine et al., 2006 ). For such an approach, one should carefully organize the instruction task, respecting several conditions for the reflection process (Karm, 2010 ) to stimulate the process beyond an intuitive approach towards an in-depth reflection process.

Finally, previous studies (e.g., Prosser et al., 2005 , 2008 ; Trigwell et al., 2005a ; Visser-Wijnveen et al., 2009 ) highlighted a statistically significant correlation between teachers’ understanding of the subject matter, teaching, and research. In this vein, one could use action research, evidence-based teaching, or research–teaching nexus (e.g., Kaasila et al., 2021 ) as frameworks for their instructional approaches to stimulate changes in academics’ conception about the subject matter.

Limitations and implications for future research

There are some limitations that should be considered. Firstly, our analyses are based on a limited pool of items (i.e., R-ATI; Trigwell et al., 2005b ). Future studies should also include items from other similar scales such as the Instruction Preference Questionnaire (Hativa & Birenbaum, 2000 ) or any other relevant inventory specially constructed to assess the teaching conceptions like the Questionnaire of Conceptions about Teaching (QCAT; Perez-Villalobos et al., 2019 ) or the Conceptions on Learning and Teaching of Teachers Questionnaire (COLT; Jacobs et al., 2020 ). A similar analysis on a larger pool of items could provide additional insights regarding academics’ conceptions or their preferences for teaching approaches.

Secondly, we used cross-sectional data. Therefore, our results should not be interpreted in a causal key. Future longitudinal research studies could evaluate the temporal order of these nodes, using statistical apparatus that is available (Epskamp et al., 2018b ). Moreover, controlled trials could investigate whether the preference for a learning-centered approach to teaching can be enhanced by programs aimed at changing academics’ conceptions about the subject matter. If such interventions will report positive results, they will provide causal evidence regarding teachers’ conceptions of the subject matter in determining the preference for a learning-centered approach of teaching.

Thirdly, future studies should investigate the network replicability considering variables such as the quality of the teaching and learning environment, main teaching method of the course, academics’ self-efficacy beliefs, academics’ conceptions, or self-regulation skills.

Fourthly, our results allow us to advance a call for more in-deep studies investigating the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter. For example, using the phenomenographic approach to explore this subject could advance our knowledge about the latent variables that define the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter. For such studies, Prosser’s works could be a useful starting point (Prosser et al., 2005 , 2008 ). In addition, the result of the phenomenographic investigation could represent the basis for the development of specific quantitative scales that measure the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter. Such instruments would be helpful for stimulating the discussion among groups of academics to raise awareness of the variation in qualitatively different ways of understanding and approaching the subject matter and the implications of these aspects on students’ learning. Also, instruments that will investigate the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter quantitatively could be used for monitoring the impact of pedagogical training for academics as those proposed above in the Implications for academic development practice section.

Finally, there is an interesting debate about how academics’ approaches and conceptions of teaching are related in the literature. While most of the studies concluded that changes in academic’ instructional strategies are more likely after a change in academics’ conceptions (Ho et al., 2001 ; Trigwell & Prosser, 1996b ; Gibbs & Coffey, 2004 ), other studies (i.e., Guskey, 2002 ; Pedrosa-de-Jesus & Silva Lopes, 2011 ) concluded that changes in teaching practices preceded changes in teaching conceptions. This latter conclusion is also partially supported by a recent study published by Cassidy and Ahmad ( 2019 ). Our results seem contrary to that advanced by Cassidy and Ahmad ( 2019 ) by concluding that academics’ conception (about the subject matter) could be the first variable that impacts the academics’ adoption of one particular approach to teaching. The network analysis perspective could be helpful to advance our knowledge on this debate. For example, Tang et al. ( 2020 ) applied network analyses (i.e., co-occurrence analysis and correlation-based analysis) to investigate the relationship and difference between curiosity and interest.

This study is one of the first studies in educational research that used the network analysis. We found that academics’ conceptions about the subject matter could be the first variable responsible for how academics develop their teaching approach preferences. Furthermore, we found that these relationships are stable across different contextual variables (i.e., the academic disciplines, class size, academics’ gender, and teaching experience). Additionally, we provided further evidence for the adaptation of the R-ATI (Trigwell et al., 2005b ) on the Romanian context. Consequently, we called for more studies that investigate the academics’ conceptions about the subject matter and their implication on teaching in higher education and, complementary, for pedagogical training programs that address these topics.

According to our results, academic developers should help teachers raise their awareness about their teaching by properly addressing their conceptions of the subject matter. It is our hope that a better understanding of the academics’ conceptions of the subject matter taught will bring valuable insights not only for the academics’ mastery of learning-focused approaches to teaching but also for meaningful student learning approaches. Also, following the example of Smarandache et al. ( 2021 ), the present study invites researchers to use the network psychometrics perspective in educational research (e.g., to investigate teachers’ conceptions, approaches to teaching, and students’ approaches to learning in higher education). We argue that the network psychometrics analysis could be useful to bring valuable insights on ongoing debates presented in the literature at this moment (e.g., the co-occurrence of approaches and conceptions of teaching), and could enhance our understanding of these phenomena.

Asikainen, H., & Gijbels, D. (2017). Do students develop towards more deep approaches to learning during studies? A systematic review on the development of students’ deep and surface approaches to learning in higher education. Educational Psychology Review, 29 (2), 205–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9406-6

Article Google Scholar

Becher, T. (1989). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines. Bristol, PA., USA: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University press.

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9 (1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Cassidy, R., & Ahmad, A. (2019). Evidence for conceptual change in approaches to teaching. Teaching in higher education , 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1680537 .

Chan, C. K. Y., & Lee, K. K. W. (2021). Reflection literacy: A multilevel perspective on the challenges of using reflections in higher education through a comprehensive literature review. Educational Research Review , 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100376

Constantini, G., & Perugini, M. (2017). Network analysis for psychological situations. In D. Funder, J. F. Rauthmann, & R. Sherman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of psychological situations . Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190263348.013.16

Chapter Google Scholar

Costantini, G., Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., Perugini, M., Mõttus, R., Waldorp, L. J., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2015). State of the art personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. Journal of Research in Personality, 54 , 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.003

De Schryver, M., Vindevogel, S., Rasmussen, A. E., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2015). Unpacking constructs: A network approach for studying war exposure, daily stressors and post-traumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 , 1896. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01896

Eley, M. G. (2006). Teachers’ conceptions of teaching, and the making of specific decisions in planning to teach. Higher Education, 51 (2), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6382-9

Entwistle, N. (2009). Teaching for understanding at university . Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of statistical software, 48 (4), 1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04 .

Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23 (4), 617. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018a). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavioral Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

Epskamp, S., van Borkulo, C. D., van der Veen, D. C., Servaas, M. N., Isvoranu, A.-M., Riese, H., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2018b). Personalized network modeling in psychopathology: The importance of contemporaneous and temporal connections. Clinical Psychological Science, 6 (3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617744325

Foygel, R., & Drton, M. (2010). Extended bayesian information criteria for gaussian graphical models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 23 , 604–612.

Google Scholar

Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2017). Network analysis: A new way of understanding psychopathology? Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition), 10 (4), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2017.10.005

Fried, E. I., Eidhof, M. B., Palic, S., Costantini, G., Huisman-van Dijk, H. M., Bockting, C. L., & Karstoft, K. L. (2018). Replicability and generalizability of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) networks: A cross-cultural multisite study of PTSD symptoms in four trauma patient samples. Clinical Psychological Science, 6 , 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617745092

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2008). Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics, 9 (3), 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045

Gibbs, G., & Coffey, M. (2004). The impact of training of university teachers on their teaching skills, their approach to teaching and the approach to learning of their students. Active learning in higher education , 5 (1), 87-100. 10.1177%2F1469787404040463.

Ginns, P., Kitay, J., & Prosser, M. (2008). Developing conceptions of teaching and the scholarship of teaching through a graduate certificate in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development, 13 (3), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440802242382

Gow, L., & Kember, D. (1993). Conceptions of teaching and their relationship to student learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63 (1), 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01039.x

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and teaching, 8 (3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

Harshman, J., & Stains, M. (2017). A review and evaluation of the internal structure and consistency of the approaches to teaching inventory. International Journal of Science Education, 39 (7), 918–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2017.1310411

Hativa, N., & Birenbaum, M. (2000). Who prefers what? Disciplinary differences in students’ preferred approaches to teaching and learning styles. Research in Higher Education, 41 (2), 209–236. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007095205308

Hicks, M., Smigiel, H., Wilson, G., & Luzeckyj, A. (2010). Preparing academics to teach in higher education. Final report . Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6 (1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2018.1521283

Ho, A., Watkins, D., & Kelly, M. (2001). The conceptual change approach to improving teaching and learning: An evaluation of a Hong Kong staff development programme. Higher Education, 42 (2), 143–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017546216800

Ilie, M. D., Maricuțoiu, L. P., Iancu, D. E., Smarandache, I. G., Mladenovici, V., Stoia, D. C. M., & Toth, S. A. (2020). Reviewing the research on instructional development programs for academics. Trying to tell a different story: a meta-analysis. Educational Research Review , 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100331

Jacobs, J. C., Wilschut, J., van der Vleuten, C., Scheele, F., Croiset, G., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2020). An international study on teachers’ conceptions of learning and teaching and corresponding teacher profiles. Medical Teacher, 42 (9), 1000–1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1772465

Kaasila, R., Lutovac, S., Komulainen, J., & Maikkola, M. (2021). From fragmented toward relational academic teacher identity: The role of research-teaching nexus. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00670-8

Karm. (2010). Refection tasks in pedagogical training courses. International Journal for Academic Development, 15 (3), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2010.497681

Kember, D. (1997). A reconceptualisation of the research into university academics’ conceptions of teaching. Learning and Instruction, 7 , 255–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00028-X

Kember, D., & Gow, L. (1994). Orientations to teaching and their effect on the quality of student learning. The Journal of Higher Education, 65 (1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1994.11778474

Kember, D., & Kwan-Por, K. (2000). Lecturers’ approaches to teaching and their relationship to conceptions of good teaching. Instructional Science, 28 , 469–290. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026569608656

Lindblom-Ylänne, S., Trigwell, K., Nevgi, A., & Ashwin, P. (2006). How approaches to teaching are affected by discipline and teaching context. Studies in Higher Education, 31 (3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680539

Lueddeke, G. R. (2003). Professionalising teaching practice in higher education: A study of disciplinary variation and teaching-scholarship. Studies in Higher Education, 28 (2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507032000058082

McAlpine, L., Weston, C., Timmermans, J., Berthiaume, D., & Fairbank-Roch, G. (2006). Zones: Reconceptualizing teacher thinking in relation to action. Studies in Higher Education, 31 (5), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600923426

Nevgi, A., & Löfström, E. (2015). The development of academics’ teacher identity: Enhancing reflection and task perception through a university teacher development programme. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46 , 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.01.003

Nevgi, A., Postareff, L., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2004). The effect of discipline on motivational and self-efficacy beliefs and on approaches to teaching of Finnish and English university teachers. Study presented at SIG higher education conference , June 18-21, 2004.

Noben, I., Deinum, J. F., Douwes-van Ark, I. M., & Hofman, W. A. (2021). How is a professional development programme related to the development of university teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and teaching conceptions? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 68 , 100966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100966

Pedrosa-de-Jesus, M. H., & Silva Lopes, B. (2011). The relationship between teaching and learning conceptions, preferred teaching approaches and questioning practices. Research Papers in Education, 26 (2), 23–243.

Perez-Villalobos, C. E., Bastias-Vega, N., Vaccarezza-Garrido, G. K., Glaria-Lopez, R., Aguilar-Aguilar, C., & Lagos-Rebolledo, P. (2019). Questionnaire on conceptions about teaching: Factorial structure and reliability in academics of health careers in Chile. Questionnaire on conceptions about teaching. J Pak Med Assoc, 69 , 355–360.

Postareff, L., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2008). Variation in teachers' descriptions of teaching: Broadening the understanding of teaching in higher education. Learning and Instruction, 18 (2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.008

Postareff, L., Katajavuori, N., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Trigwell, K. (2008a). Consonance and dissonance in descriptions of teaching of university teachers. Studies in Higher Education, 33 (1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701794809

Postareff, L., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Nevgi, A. (2007). The effect of pedagogical training on teaching in higher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23 (5), 557–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.013

Postareff, L., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Nevgi, A. (2008b). A follow-up study of the effect of pedagogical training on teaching in higher education. Higher Education, 56 (1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9087-z

Postareff, L., & Nevgi, A. (2015). Development paths of university teachers during a pedagogical development course. Educar, 51 (1), 37–52.

Prosser, M., Martin, E., Trigwell, K., Ramsden, P., & Lueckenhausen, G. (2005). Academics’ experiences of understanding of their subject matter and the relationship of this to their experiences of teaching and learning. Instructional Science, 33 , 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-004-7687-x

Prosser, M., Martin, E., Trigwell, K., Ramsden, P., & Middleton, H. (2008). University academics’ experience of research and its relationship to their experience of teaching. Instructional Science, 36 , 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-007-9019-4

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (2014). Qualitative variation in approaches to university teaching and learning in large first-year classes. Higher Education, 67 (6), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9690-0

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1999). Relational perspectives on higher education teaching and learning in the sciences. Studies in Science Education, 33 (1), 3–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057269908560135

Prosser, M., Ramsden, P., Trigwell, K., & Martin, E. (2003). Dissonance in experience of teaching and its relation to the quality of student learning. Studies in Higher Education, 28 (1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070309299

Samuelowicz, K., & Bain, J. D. (1992). Conceptions of teaching held by academic teachers. Higher Education, 24 (1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138620

Sava, F. A. (2004). Analiza datelor în cercetarea psihologică: Metode statistice complementare [data analysis in psychological research: Complementary statistical methods] . Romanian Cognitive Sciences Association.

Singer, E. R. (1996). Espoused teaching paradigms of college faculty. Research in Higher Education, 37 (6), 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01792951

Smarandache, I. G., Maricuțoiu, L. P., Ilie, M. D., Iancu, D. E., & Mladenovici, V. (2021). Students’ approach to learning: Evidence regarding the importance of the interest-to-effort ratio. Higher Education Research and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1865283

Stes, A., Coertjens, L., & Van Petegem, P. (2010a). Instructional development for teachers in higher education: Impact on teaching approach. Higher Education, 60 , 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9294-x

Stes, A., & Van Petegem, P. (2014). Profiling approaches to teaching in higher education: A cluster-analytic study. Studies in Higher Education, 39 (4), 644–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.729032

Stes, A., Gijbels, D., & Van Petegem, P. (2008). Student-focused approaches to teaching in relation to context and teacher characteristics. Higher Education, 55 (3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9053-9

Stes, A., De Maeyer, S., & Van Petegem, P. (2010b). Approaches to teaching in higher education: Validation of a Dutch version of the approaches to teaching inventory. Learning Environments Research, 13 (1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-009-9066-7

Stewart, M. (2014). Making sense of a teaching programme for university academics: Exploring the longer-term effects. Teaching and Teacher Education, 38 , 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.006

Tang, X., Renninger, K. A., Hidi, S. E., Murayama, K., Lavonen, J., Salmela-Aro, K. (2020). The differences and similarities between curiosity and interest: Meta-analysis and network analyses. 10.31234/osf.io/wfprn.

Trautwein, C. (2018). Academics’ identity development as teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 23 (8), 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1449739

Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (2020). Exploring university teaching and learning. Experience and context . Palgrave Macmillan.

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., Martin, E., & Ramsden, P. (2005a). University teachers’ experiences of change in their understanding of the subject matter they have taught. Teaching in Higher Education, 10 (2), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251042000337981