Bipolar Awareness: Understanding and Supporting Individuals with Bipolar Disorder

Amidst the vibrant spectrum of human emotions, bipolar disorder paints a complex and often misunderstood portrait of mental health, challenging society to look beyond the surface and embrace empathy, awareness, and support. This mental health condition, characterized by extreme mood swings ranging from manic highs to depressive lows, affects millions of individuals worldwide, impacting their daily lives, relationships, and overall well-being.

Bipolar disorder, formerly known as manic depression, is a chronic mental health condition that affects approximately 2.8% of the adult population in the United States alone. The disorder is characterized by alternating episodes of mania or hypomania (periods of elevated mood and increased energy) and depression (periods of low mood and decreased energy). These episodes can last for days, weeks, or even months, significantly impacting an individual’s ability to function in their personal and professional lives.

The prevalence of bipolar disorder underscores the critical importance of raising awareness about this condition. By fostering a deeper understanding of bipolar disorder, we can create a more compassionate and supportive environment for those affected by it. Increased awareness can lead to earlier diagnosis, improved access to treatment, and reduced stigma surrounding mental health issues.

National Bipolar Day: A Day to Educate and Advocate

National Bipolar Day, observed annually on March 30th, serves as a powerful platform to educate the public about bipolar disorder and advocate for those affected by it. This day was established to coincide with the birthday of Vincent van Gogh, the renowned Dutch post-impressionist painter who is believed to have suffered from bipolar disorder.

The significance of National Bipolar Day lies in its ability to bring together individuals, organizations, and communities to raise awareness about bipolar disorder. It provides an opportunity to share accurate information, dispel myths, and promote understanding of the challenges faced by those living with the condition.

On National Bipolar Day, various activities and events are organized to engage the public and promote awareness. These may include:

1. Educational seminars and workshops 2. Support group meetings and discussions 3. Art exhibitions showcasing works by individuals with bipolar disorder 4. Social media campaigns using hashtags like #NationalBipolarDay 5. Fundraising events for bipolar disorder research and support programs

These initiatives play a crucial role in promoting understanding and empathy through awareness campaigns. By sharing personal stories, providing factual information, and encouraging open dialogue, National Bipolar Day helps to break down barriers and foster a more inclusive society for individuals with bipolar disorder.

World Bipolar Day 2018: Spreading Awareness Globally

World Bipolar Day, celebrated annually on March 30th, is a global initiative aimed at raising awareness about bipolar disorder on an international scale. The day was initiated by the Asian Network of Bipolar Disorder (ANBD), the International Bipolar Foundation (IBPF), and the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) to bring world attention to bipolar disorder and eliminate social stigma.

In 2018, World Bipolar Day focused on the theme “Bipolar Disorder: Know Your Triggers.” This theme emphasized the importance of understanding personal triggers that can lead to manic or depressive episodes, empowering individuals with bipolar disorder to better manage their condition.

Throughout the day, various events and initiatives were undertaken worldwide to spread awareness and educate the public about bipolar disorder. These included:

1. Online webinars featuring mental health professionals and individuals living with bipolar disorder 2. Social media campaigns encouraging people to share their experiences using #WorldBipolarDay 3. Community outreach programs in schools and workplaces 4. Lighting up landmarks in green, the color associated with bipolar awareness

One of the most powerful aspects of World Bipolar Day 2018 was the sharing of personal stories by individuals living with bipolar disorder. These narratives provided invaluable insights into the daily challenges and triumphs of managing the condition, helping to unscramble bipolar disorder for those unfamiliar with its complexities.

For instance, Sarah, a 32-year-old graphic designer, shared her journey of living with bipolar disorder: “Some days, I feel like I can conquer the world, brimming with creative energy and ideas. Other days, it’s a struggle just to get out of bed. Learning to recognize my triggers and developing coping strategies has been crucial in managing my bipolar disorder and leading a fulfilling life.”

World Bipolar Day 2016: Highlighting Advocacy and Support

World Bipolar Day 2016 marked another significant milestone in the ongoing efforts to raise awareness about bipolar disorder. The theme for that year was “More Than A Diagnosis,” emphasizing the importance of seeing individuals with bipolar disorder as whole persons, not just their diagnosis.

The day saw numerous collaborations and partnerships between mental health organizations, healthcare providers, and advocacy groups. These collaborations aimed to provide comprehensive education about bipolar disorder, its symptoms, treatment options, and the importance of early intervention.

Key initiatives during World Bipolar Day 2016 included:

1. Launch of online resources and toolkits for individuals, families, and healthcare providers 2. Partnerships with celebrities and public figures to share their experiences with bipolar disorder 3. Community-based screening programs to promote early detection and intervention 4. Workplace seminars to educate employers about supporting employees with bipolar disorder

A crucial focus of World Bipolar Day 2016 was the importance of reducing stigma and promoting acceptance. Stigma remains one of the biggest barriers to seeking help and receiving proper treatment for bipolar disorder. By encouraging open conversations and challenging misconceptions, the day aimed to create a more supportive environment for individuals living with bipolar disorder.

Bipolar Disorder Day: Recognizing the Challenges and Offering Support

While not an officially recognized day, the concept of a “Bipolar Disorder Day” emphasizes the ongoing need for awareness and support throughout the year. This concept encourages continuous efforts to educate the public about bipolar disorder, its symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Understanding bipolar disorder is crucial for early detection and effective management. The condition is characterized by distinct episodes of mania or hypomania and depression. Manic episodes may include symptoms such as:

– Increased energy and activity – Decreased need for sleep – Racing thoughts and rapid speech – Impulsive or risky behavior

Depressive episodes, on the other hand, may involve:

– Persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness – Loss of interest in activities once enjoyed – Changes in appetite and sleep patterns – Difficulty concentrating and making decisions

It’s important to note that bipolar symptoms in men may present differently than in women, highlighting the need for gender-specific awareness and understanding.

Diagnosis of bipolar disorder typically involves a comprehensive evaluation by a mental health professional, including a detailed medical history, physical exam, and psychological assessment. Treatment often includes a combination of medication (such as mood stabilizers and antipsychotics) and psychotherapy (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or interpersonal therapy).

Support and resources available for individuals with bipolar disorder are crucial for managing the condition effectively. These may include:

1. Support groups (both in-person and online) 2. Educational programs for individuals and families 3. Occupational therapy to help maintain employment 4. Crisis hotlines for immediate support during difficult times

Bipolar bracelets have also gained popularity as a visible symbol of support and awareness, serving as a reminder of the wearer’s journey or as a conversation starter to educate others about the condition.

World Bipolar Day 2022: Looking to the Future

As we look ahead to World Bipolar Day 2022, the focus continues to be on raising awareness, promoting understanding, and improving the lives of individuals with bipolar disorder. The theme for 2022 is expected to build upon previous years’ efforts, emphasizing the importance of holistic care and support for those living with bipolar disorder.

Anticipated activities for World Bipolar Day 2022 include:

1. Virtual conferences and webinars featuring leading researchers and clinicians 2. Global social media campaigns to share information and personal stories 3. Launch of new resources and support tools for individuals and families 4. Collaborative research initiatives to advance understanding and treatment of bipolar disorder

Recent advancements in research, treatment, and support for bipolar disorder offer hope for improved outcomes. These include:

– Development of new medications with fewer side effects – Increased understanding of the genetic factors contributing to bipolar disorder – Innovative psychotherapy approaches tailored for bipolar disorder – Integration of digital health technologies for mood monitoring and early intervention

The role of advocacy and community support remains crucial in improving the lives of individuals with bipolar disorder. Grassroots organizations, online communities, and bipolar quotes shared on social media platforms continue to play a vital role in providing support, sharing information, and reducing stigma.

As we continue to raise awareness about bipolar disorder, it’s important to remember that understanding and support are ongoing processes. The journey towards better mental health care and reduced stigma requires consistent effort and dedication from individuals, communities, and society as a whole.

Bipolar Day , whether observed nationally or globally, serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of mental health awareness. It challenges us to look beyond stereotypes and misconceptions, encouraging empathy and understanding for those living with bipolar disorder.

The ongoing efforts to raise awareness about bipolar disorder are crucial in creating a more inclusive and supportive society. By continuing to educate ourselves and others, we can help reduce the stigma associated with mental health conditions and promote a culture of acceptance and support.

As we move forward, let us remember that every day is an opportunity to learn, understand, and support individuals with bipolar disorder. Whether it’s through sharing information, offering a listening ear, or advocating for better mental health policies, each of us has a role to play in creating a world where individuals with bipolar disorder can thrive.

In the words of Kay Redfield Jamison, a clinical psychologist and author who has written extensively about her own experiences with bipolar disorder, “We all build internal sea walls to keep at bay the sadnesses of life and the often overwhelming forces within our minds. In whatever way we do this—through love, work, family, faith, friends, denial, alcohol, drugs, or medication—we build these walls, stone by stone, over a lifetime.”

Let us continue to build bridges of understanding and support, ensuring that no one faces the challenges of bipolar disorder alone. Through awareness, education, and compassion, we can create a world where the bipolar flag flies high, symbolizing hope, resilience, and unity in the face of mental health challenges.

References:

1. National Institute of Mental Health. (2021). Bipolar Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder

2. International Bipolar Foundation. (n.d.). World Bipolar Day. Retrieved from https://ibpf.org/learn/programs/world-bipolar-day/

3. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance. (n.d.). Bipolar Disorder Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.dbsalliance.org/education/bipolar-disorder/bipolar-disorder-statistics/

4. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

5. Jamison, K. R. (1995). An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York: Vintage Books.

6. World Health Organization. (2019). Mental disorders. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

7. National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Bipolar Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Mental-Health-Conditions/Bipolar-Disorder

8. Goodwin, F. K., & Jamison, K. R. (2007). Manic-Depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Similar Posts

Bipolar Fatigue: Understanding and Overcoming the Challenges

Exhaustion creeps in like an unwelcome shadow, draining the vibrant colors from life’s palette—welcome to the world of bipolar fatigue, a relentless adversary that countless individuals battle daily. This pervasive symptom of bipolar disorder can be overwhelming, affecting every aspect of a person’s life. However, understanding its nature and learning effective management strategies can help…

Understanding Postpartum Depression Disability Leave in California

Postpartum depression is a serious mental health condition that affects many new mothers, often requiring time off work to recover and care for their newborn. In California, understanding the intricacies of disability leave for postpartum depression is crucial for both employees and employers. This article delves into the details of postpartum depression disability leave in…

Divorcing a Narcissist: A Comprehensive Guide for Dealing with a Bipolar Narcissist

Shattered mirrors and emotional minefields await those brave souls who dare to untangle the Gordian knot of divorcing a bipolar narcissist. The journey ahead is fraught with challenges, but armed with knowledge and determination, it is possible to navigate this treacherous terrain and emerge stronger on the other side. Divorcing a narcissist is already a…

Newly Coined Synonyms for Depression: Expanding the Vocabulary of Mental Health Awareness

Language plays a crucial role in shaping our perception of mental health, influencing how we understand, discuss, and address various conditions. As our understanding of mental health evolves, so too must the vocabulary we use to describe these complex experiences. This is particularly true when it comes to depression, a condition that affects millions of…

Living with Someone with Bipolar: Understanding, Supporting, and Communicating

Navigating the unpredictable waves of bipolar disorder can be a challenging journey for both the individual affected and their loved ones, but with understanding, support, and effective communication, it’s possible to create a harmonious and loving relationship. The complexities of bipolar disorder often leave partners, family members, and friends feeling overwhelmed and uncertain about how…

Can Anxiety Disorder Cause Death: Understanding the Link between Anxiety and Mortality

Your heart races, your palms sweat, and your mind spirals—but could these familiar symptoms of anxiety be silently shortening your life? Anxiety disorders are more than just fleeting moments of worry or stress; they are persistent, often debilitating conditions that can have far-reaching effects on both mental and physical health. As we delve into the…

- Bipolar Disorder

Manic Depression

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic depression , is a chronically recurring condition involving moods that swing between the highs of mania and the lows of depression. Depression is by far the most pervasive feature of the illness. The manic phase usually involves a mix of irritability, anger , and depression, with or without euphoria. When euphoria is present, it may manifest as unusual energy and overconfidence, playing out in bouts of overspending or promiscuity, among other behaviors.

The disorder most often starts in young adulthood, but can also occur in children and adolescents. Misdiagnosis is common; the condition is often confused with attention -deficit/hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, or borderline personality disorder . Biological factors probably create vulnerability to the disorder within certain individuals, and experiences such as sleep deprivation can kick off manic episodes .

There are two primary types of bipolar disorder: Bipolar I and Bipolar II. A major depressive episode may or may not accompany bipolar I, but does accompany bipolar II. People with bipolar I have had at least one manic episode, which may be very severe and require hospital care. People with bipolar II normally have a major depressive episode that lasts at least two weeks along with hypomania , a mania that is mild to moderate and does not normally require hospital care.

- Signs of Bipolar Disorder

- Causes of Bipolar Disorder

- Treatment for Bipolar Disorder

- Living with Bipolar Disorder

The defining feature of bipolar disorder is mania. It can be the triggering episode of the disorder, followed by a depressive episode, or it can first manifest after years of depressive episodes. The switch between mania and depression can be abrupt, and moods can oscillate rapidly. But while an episode of mania is what distinguishes bipolar disorder from depression, a person may spend far more time in a depressed state than in a manic or hypomanic one.

Hypomania can be deceptive; it is often experienced as a surge in energy that can feel good and even enhance productivity and creativity . As a result, a person experiencing it may deny that anything is wrong. There is great variability in manic symptoms, but features may include increased energy, activity, and restlessness; euphoric mood and extreme optimism ; extreme irritability; racing thoughts, unusually fast speech, or thoughts that jump from one idea to another; distractibility and lack of concentration ; decreased need for sleep; an unrealistic belief in one's abilities and ideas; poor judgment; reckless behavior including spending sprees and dangerous driving, or risky and increased sexual drive; provocative, intrusive, or aggressive behavior; and denial that anything is wrong.

The duration of elevated moods and the frequency with which they alternate with depressive moods can vary enormously from person to person. Frequent fluctuation, known as rapid cycling, is not uncommon and is defined as at least four episodes per year.

Just as there is considerable variability in manic symptoms, there is great variability in the degree and duration of depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder. Features generally include lasting sad, anxious, or empty mood; feelings of hopelessness or pessimism ; feelings of guilt , worthlessness, or helplessness; a loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed, including sex; decreased energy and feelings of fatigue or of being "slowed down"; difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions; restlessness or irritability; oversleeping or an inability to sleep or stay asleep; change in appetite and/or unintended weight loss or gain; chronic pain or other persistent physical symptoms not accounted for by illness or injury; and thoughts of death or suicide, or suicide attempts.

The symptoms of mania and depression often occur together in "mixed" episodes. Symptoms of a mixed state can include agitation, trouble sleeping , significant change in appetite, psychosis , and suicidal thinking. At these times, a person can feel sad yet highly energized.

About 2.8 percent of American adults have had bipolar disorder in the past year, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, and 4.4 percent experience bipolar disorder at some time in their lives. These rates are similar among men and women. Worldwide, the disorder affects about 45 million people, according to the World Health Organization.

Most people with bipolar disorder develop the condition in their late teens or early twenties, although symptoms can appear in children as young as six years old. The average age of a first episode of mania, hypomania, or depression is 18 years old for bipolar I and mid-20s for bipolar II, according to the DSM-5 .

Symptoms in children and teens are similar to those in adults and include the condition's hallmark mood swings. Children with bipolar disorder undergo extreme changes in mood and behavior, feeling unusually happy and energetic during manic episodes and becoming very sad and less active during depressive episodes. Manic episodes may involve increased energy, distractibility, grandiosity, and inability to sleep while depressive episodes may involve self-harm or suicidal thoughts and gestures, which should be taken seriously.

One key factor: bipolar is episodic while other disorders are pervasive. For example, bipolar symptoms come and go in mood swings, while disorders like ADHD tend to be more consistent if left untreated.

People often struggle with unidentified and untreated bipolar disorder for years. In fact, about two-thirds of people with bipolar disorder are misdiagnosed before bipolar is discovered.

Most of these individuals are misdiagnosed with depression. When thinking about the difference between the two, patients and clinicians can consider family history due to the genetic roots of the disorder, and personal history of unexplained excitability and euphoria or rage , self-harm, and suicidality . Antidepressants can trigger mania in some cases; it’s critical to monitor if a patient feels more agitated, irritable, aggressive, or hyperactive after beginning medication .

In the case of schizophrenia, manic episodes can include or resemble psychosis, while depressive episodes resemble the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. (Such patients may receive a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.)

Both genetic and environmental factors can create vulnerability to bipolar disorder. As a result, the causes vary from person to person. While the disorder can run in families, no one has definitively identified specific genes that create a risk for developing the condition. There is some evidence that advanced paternal age at conception can increase the possibility of new genetic mutations that underlie vulnerability. Imaging studies have suggested that there may be differences in the structure and function of certain brain areas, but no differences have been consistently found.

Life events including various types of childhood trauma are thought to play a role in spurring bipolar disorder in those who are already vulnerable to developing the condition. Researchers do know that once bipolar disorder occurs, life events can precipitate its recurrence. Incidents of interpersonal difficulty and abuse are most commonly associated with triggering the disorder.

“Family history is the strongest and most consistent factor for bipolar disorder,” states the DSM-5. The risk is 10 times greater for those who have a relative with bipolar I or bipolar II. Genes that are passed down in a family with bipolar appear to influence how the brain handles mood regulation.

When attempting to explore a bipolar diagnosis, it’s vital to understand the family history of mental health to know whether an individual may be predisposed. For example, it’s worth considering if anyone in the family, particularly one’s closest relatives, has experienced severe mood swings, intensely erratic behavior, or high irritability followed by deep sadness.

Some people with traumatic brain injuries (TBI)—due to a car accident or a sports injury, for example—experience heightened levels of anxiety , depression, and mood swings. Individuals with a TBI are four times more likely to develop a mental illness, according to a Danish study of more than 100,000 people with head injuries. People with a TBI are 28 percent more likely to develop bipolar disorder, 59 percent more likely to develop depression, and 65 percent more likely to develop schizophrenia.

Bipolar disorder has biological roots, but life experiences may trigger or exacerbate it. Many patients cite a specific psychosocial trigger for their first episode of bipolar disorder, such as a breakup, family trauma, substance use, or period of stress. Being aware of these factors is important for both identifying and treating bipolar .

Because bipolar disorder is a recurrent illness, long-term treatment is necessary. Mood stabilizer drugs are typically prescribed to prevent mood swings. Lithium is perhaps the best-known mood stabilizer, but newer drugs such as lamotrigine have been shown to cause fewer side effects while frequently obviating the need for antidepressant medication. Used alone, antidepressants can precipitate mania and may accelerate mood cycling. Getting the full range of symptoms under control may require other drugs as well, either short-term or long-term.

Nutritional approaches have also been found to have therapeutic value. Studies show that omega-3 fatty acids may help lower the number or dosage of medications needed. Omega-3 fatty acids play a role in the functioning of all brain cells and are incorporated into the structure of brain cell membranes.

Work and relationship problems can be both a cause and effect of bipolar episodes, making psychotherapeutic treatment important. Studies show that such treatment reduces the number of mood episodes patients experience. Psychotherapy is also valuable in teaching self-management skills, which help keep one's everyday ups and downs from triggering full-blown episodes.

In addition to medication management, therapy is an important component of treating bipolar disorder. Evidence-based therapies include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy—which helps patients reframe harmful or irrational thoughts to change mood and behavior—as well as Interpersonal Therapy, Family-Focused Therapy, and psychoeducational approaches. Family-Focused therapy may be particularly helpful for children and teens with bipolar disorder.

Therapy helps treat bipolar disorder through many different pathways. Therapy offers psychoeducation to improve medication compliance, skills to cope with the challenges of living with the condition, lifestyle remedies, connection to loved ones for greater support, and immediate help for crises that might trigger a manic or depressive episode. Patients come to treatment with different goals, so a therapist should encourage patients to share those goals and work collaboratively to find the right approach.

People with bipolar disorder typically need medication, but choosing the right drug or drug combination often requires some trial and error. To determine the right treatment, the psychiatrist may start with a low dose and gradually increase it based on the patient’s response and tolerance. They will seek feedback from the patient, and prescribe one medication at a time to find the best fit.

Patients may experience difficult side effects, such as fatigue, weight gain, and nausea. Lifestyle changes can help manage those symptoms —patients can exercise, maintain a healthy diet , keep a regular sleep schedule, and seek social support.

Sharing concerns about medication in therapy is important so that patients and clinicians can determine the best path forward. If one medication has not worked well, there may be other options to explore. If there are concerns around the stigma of psychiatric medication or fears of maintaining one’s sense of self, a therapist can provide clarity and support.

Bipolar disorder can wreak havoc on a person's goals and relationships. But in conjunction with proper medical care, sufferers can learn coping skills and strategies to keep their lives on track. Bipolar disorder, like many mental illnesses, is sometimes a controversial diagnosis. While most sufferers consider the disorder to be a hardship, some appreciate its role in their lives, and others even link it to greater creative output.

While the depression of bipolar disorder is hard to treat, mood swings and recurrences can often be delayed or prevented with a mood stabilizer, on its own or combined with other drugs. Psychotherapy is an important adjunct to pharmacotherapy, especially for dealing with work and relationship problems that typically accompany the disorder. Clinicians are well aware that there is no one-size-fits-all cure: An individual with a first-time manic episode will not be the same as an individual who has lived with bipolar for a decade.

The fear of losing one’s creativity, productivity, and sense of identity can prevent people from seeking help. But neglecting treatment to preserve manic energy often leads to a crash that can threaten every aspect of the person’s well-being.

A therapist can allay these concerns and redefine creativity. The intense rise of manic energy is sometimes confused for creativity rather than disorganized and reckless output; mania can delude the person into believing their skills are greater than they truly are. A therapist can help a patient with bipolar to steadily harness their creative abilities following mood stabilization and develop an organized strategy and timeline to achieve their goals.

Many individuals with bipolar disorder experience hyper-religiosity during mania. Fifteen to 22 percent of those with bipolar mania in the U.S. experience religious delusions, such as thinking that demons are watching them or that they are Christ reborn.

The complex phenomenon of spirituality involves networks of multiple brain regions. Parts of the parietal lobe are associated with feelings of spiritual transcendence, parts of the temporal and frontal cortices are involved in the storage and retrieval of religious beliefs in memory , and still other parts of the frontal lobe and limbic structures are responsible for rational and emotional aspects of religious beliefs. Dopamine levels in those with bipolar disorder may play a role in elevating religious and spiritual experiences.

The experience of bipolar disorder can differ between people. While not discounting the tremendous toll the disorder takes on many lives, some people with bipolar disorder believe the condition confers certain advantages , such as creativity, motivation , and leadership . Famous figures are often cited to illustrate the connection between genius and mental illness, such as Vincent van Gogh, Winston Churchill, and more recently, Kanye West.

One common misconception about bipolar disorder is that mania is always “good” because it’s better than being depressed. But people in a manic episode often do ignorant or foolish things, make mistakes, and hurt other people. Another misunderstanding is that actions during manic periods are fully voluntary, but the person doesn’t have complete control over their faculties.

Another misunderstanding is that treatment ends when a person is stable. Bipolar disorder is chronic, so maintaining stability, incorporating lifestyle changes, and being aware of triggers is an ongoing process.

Do you dance to the beat of your own drum, but fear that others don't hear the music?

Your mental health is unlikely to be diagnosed by #Relatable online.

A Personal Perspective: Societal pressure to be happy all the time sets us up for failure. Here’s how to overcome that trap.

Anxiety often travels with company, and many things masquerade as anxiety.

Inexplicable behavior at work deserves more than outrage. It can be a sign of mental health struggles.

Personal Perspective: The term "behavioral health" was cultivated to reduce the stigma of mental health and psychiatric services. Has it done more harm than good?

The "prodromal" phase, the early rumbles in individuals at high risk of psychosis, may present an opportunity for improved response to interventions.

A Personal Perspective: Let go of preconceived ideas about wellness tools and allow yourself the freedom to find what works for you, no matter how uncommon it seems.

New research is revealing that inherited mental illnesses are promoted by alterations in DNA that were caused by viral infection of our ancestors over a million years ago.

A Personal Perspective: It’s possible to plan a future despite the uncertainties of mental illness.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

Bipolar Disorder

- Download PDF

- Order a free hardcopy

Do you have periods of time when you feel unusually “up” (happy and outgoing, or irritable), but other periods when you feel “down” (unusually sad or anxious)? During the “up” periods, do you have increased energy or activity and feel a decreased need for sleep, while during the “down” times you have low energy, hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal thoughts? Do these symptoms of fluctuating mood and energy levels cause you distress or affect your daily functioning? Some people with these symptoms have a lifelong but treatable mental illness called bipolar disorder.

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness that can be chronic (persistent or constantly reoccurring) or episodic (occurring occasionally and at irregular intervals). People sometimes refer to bipolar disorder with the older terms “manic-depressive disorder” or “manic depression.”

Everyone experiences normal ups and downs, but with bipolar disorder, the range of mood changes can be extreme. People with the disorder have manic episodes, or unusually elevated moods in which the individual might feel very happy, irritable, or “up,” with a marked increase in activity level. They might also have depressive episodes, in which they feel sad, indifferent, or hopeless, combined with a very low activity level. Some people have hypomanic episodes, which are like manic episodes, but not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization.

Most of the time, bipolar disorder symptoms start during late adolescence or early adulthood. Occasionally, children may experience bipolar disorder symptoms. Although symptoms may come and go, bipolar disorder usually requires lifelong treatment and does not go away on its own. Bipolar disorder can be an important factor in suicide, job loss, ability to function, and family discord. However, proper treatment can lead to better functioning and improved quality of life.

What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can vary. An individual with the disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that last a week or two, or sometimes longer. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Feelings are intense and happen with changes in behavior, energy levels, or activity levels that are noticeable to others. In between episodes, mood usually returns to a healthy baseline. But in many cases, without adequate treatment, episodes occur more frequently as time goes on.

| Feeling very up, high, elated, or extremely irritable or touchy | Feeling very down or sad, or anxious |

| Feeling jumpy or wired, more active than usual | Feeling slowed down or restless |

| Racing thoughts | Trouble concentrating or making decisions |

| Decreased need for sleep | Trouble falling asleep, waking up too early, or sleeping too much |

| Talking fast about a lot of different things (“flight of ideas”) | Talking very slowly, feeling unable to find anything to say, or forgetting a lot |

| Excessive appetite for food, drinking, sex, or other pleasurable activities | Lack of interest in almost all activities |

| Feeling able to do many things at once without getting tired | Unable to do even simple things |

| Feeling unusually important, talented, or powerful | Feeling hopeless or worthless, or thinking about death or suicide |

Some people with bipolar disorder may have milder symptoms than others. For example, hypomanic episodes may make an individual feel very good and productive; they may not feel like anything is wrong. However, family and friends may notice the mood swings and changes in activity levels as unusual behavior, and depressive episodes may follow hypomanic episodes.

Types of Bipolar Disorder

People are diagnosed with three basic types of bipolar disorder that involve clear changes in mood, energy, and activity levels. These moods range from manic episodes to depressive episodes.

- Bipolar I disorder is defined by manic episodes that last at least 7 days (most of the day, nearly every day) or when manic symptoms are so severe that hospital care is needed. Usually, separate depressive episodes occur as well, typically lasting at least 2 weeks. Episodes of mood disturbance with mixed features are also possible. The experience of four or more episodes of mania or depression within a year is termed “rapid cycling.”

- Bipolar II disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive and hypomanic episodes, but the episodes are less severe than the manic episodes in bipolar I disorder.

- Cyclothymic disorder (also called cyclothymia) is defined by recurrent hypomanic and depressive symptoms that are not intense enough or do not last long enough to qualify as hypomanic or depressive episodes.

“Other specified and unspecified bipolar and related disorders” is a diagnosis that refers to bipolar disorder symptoms that do not match the three major types of bipolar disorder outlined above.

What causes bipolar disorder?

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is unknown. However, research suggests that a combination of factors may contribute to the illness.

Bipolar disorder often runs in families, and research suggests this is mostly explained by heredity—people with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than others. Many genes are involved, and no one gene can cause the disorder.

But genes are not the only factor. Studies of identical twins have shown that one twin can develop bipolar disorder while the other does not. Though people with a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop it, most people with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop it.

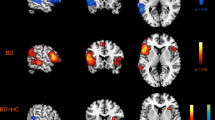

Brain Structure and Function

Research shows that the brain structure and function of people with bipolar disorder may differ from those of people who do not have bipolar disorder or other mental disorders. Learning about the nature of these brain changes helps researchers better understand bipolar disorder and, in the future, may help predict which types of treatment will work best for a person with bipolar disorder.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

To diagnose bipolar disorder, a health care provider may complete a physical exam, order medical testing to rule out other illnesses, and refer the person for an evaluation by a mental health professional. Bipolar disorder is diagnosed based on the severity, length, and frequency of an individual’s symptoms and experiences over their lifetime.

Some people have bipolar disorder for years before it’s diagnosed for several reasons. People with bipolar II disorder may seek help only for depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes may go unnoticed. Misdiagnosis may happen because some bipolar disorder symptoms are like those of other illnesses. For example, people with bipolar disorder who also have psychotic symptoms can be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Some health conditions, such as thyroid disease, can cause symptoms like those of bipolar disorder. The effects of recreational and illicit drugs can sometimes mimic or worsen mood symptoms.

Conditions That Can Co-Occur With Bipolar Disorder

Many people with bipolar disorder also have other mental disorders or conditions such as anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), misuse of drugs or alcohol, or eating disorders. Sometimes people who have severe manic or depressive episodes also have symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations or delusions. The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

Looking at symptoms over the course of the illness and the person’s family history can help determine whether a person has bipolar disorder along with another disorder.

How is bipolar disorder treated?

Treatment helps many people, even those with the most severe forms of bipolar disorder. Mental health professionals treat bipolar disorder with medications, psychotherapy, or a combination of treatments.

Medications

Certain medications can help control the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Some people may need to try several different medications before finding the ones that work best. The most common types of medications that doctors prescribe include mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics. Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. While bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well, as an antidepressant alone can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder. Medications that target sleep or anxiety are sometimes added to mood stabilizers as part of a treatment plan.

Talk with your health care provider to understand the risks and benefits of each medication. Report any concerns about side effects to your health care provider right away. Avoid stopping medication without talking to your health care provider first. Read the latest medication warnings, patient medication guides, and information on newly approved medications on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website .

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (sometimes called “talk therapy”) is a term for various treatment techniques that aim to help a person identify and change troubling emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. Psychotherapy can offer support, education, skills, and strategies to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Some types of psychotherapy can be effective treatments for bipolar disorder when used with medications, including interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, which aims to understand and work with an individual’s biological and social rhythms. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an important treatment for depression, and CBT adapted for the treatment of insomnia can be especially helpful as a component of the treatment of bipolar depression. Learn more on NIMH’s psychotherapies webpage .

Other Treatments

Some people may find other treatments helpful in managing their bipolar disorder symptoms.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a brain stimulation procedure that can help relieve severe symptoms of bipolar disorder. ECT is usually only considered if an individual’s illness has not improved after other treatments such as medication or psychotherapy, or in cases that require rapid response, such as with suicide risk or catatonia (a state of unresponsiveness).

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a type of brain stimulation that uses magnetic waves, rather than the electrical stimulus of ECT, to relieve depression over a series of treatment sessions. Although not as powerful as ECT, TMS does not require general anesthesia and presents little risk of memory or adverse cognitive effects.

- Light Therapy is the best evidence-based treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and many people with bipolar disorder experience seasonal worsening of depression in the winter, in some cases to the point of SAD. Light therapy could also be considered for lesser forms of seasonal worsening of bipolar depression.

Complementary Health Approaches

Unlike specific psychotherapy and medication treatments that are scientifically proven to improve bipolar disorder symptoms, complementary health approaches for bipolar disorder, such as natural products, are not based on current knowledge or evidence. For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website .

Coping With Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be challenging, but there are ways to help yourself, as well as your friends and loved ones.

- Get treatment and stick with it. Treatment is the best way to start feeling better.

- Keep medical and therapy appointments and talk with your health care provider about treatment options.

- Take medication as directed.

- Structure activities. Keep a routine for eating, sleeping, and exercising.

- Try regular, vigorous exercise like jogging, swimming, or bicycling, which can help with depression and anxiety, promote better sleep, and is healthy for your heart and brain.

- Keep a life chart to help recognize your mood swings.

- Ask for help when trying to stick with your treatment.

- Be patient. Improvement takes time. Social support helps.

Remember, bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness, but long-term, ongoing treatment can help manage symptoms and enable you to live a healthy life.

Are there clinical trials studying bipolar disorder?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions—including bipolar disorder. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge to help others in the future. Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit the NIMH clinical trials webpage .

Finding Help

Behavioral health treatment services locator.

This online resource, provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), can help you locate mental health treatment facilities and programs. Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator . For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage .

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org. You can also contact the Crisis Text Line ( text HELLO to 741741 ). For medical emergencies, call 911.

Talking to a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

Communicating well with a health care provider can improve your care and help you both make good choices about your health. Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit . For additional resources, including questions to ask a provider, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website .

The information in this publication is in the public domain and may be reused or copied without permission. However, you may not reuse or copy images. Please cite the National Institute of Mental Health as the source. Read our copyright policy to learn more about our guidelines for reusing NIMH content.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) ( en español )

ClinicalTrials.gov ( en español )

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 22-MH-8088 Revised 2022

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a serious mental illness in which common emotions become intensely and often unpredictably magnified. Individuals with bipolar disorder can quickly swing from extremes of happiness, energy, and clarity to sadness, fatigue, and confusion. These shifts can be so devastating that individuals may consider suicide.

All people with bipolar disorder have manic episodes—abnormally elevated or irritable moods that last at least a week and impair functioning. But not all become depressed.

Adapted from the Encyclopedia of Psychology

Resources from APA

Treatment and recovery from serious mental illness

Kim Mueser, PhD, talks about the progress psychology has made in treating serious mental illness

How to live with bipolar disorder

David Miklowitz, PhD, and Terri Cheney talk about diagnosis and treatments of bipolar disorder

Diagnosing and treating bipolar disorders

Patients with bipolar disorder cycle between two or more mood states, such as mania, hypomania, or depression.

Treating bipolar disorder in kids and teens

New research is helping practitioners better understand the symptoms of pediatric bipolar disorder

More resources about bipolar disorder

APA publications

Psychological Assessment of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

Essay Service Examples Health Bipolar Disorder

Informative Speech about Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder

- Proper editing and formatting

- Free revision, title page, and bibliography

- Flexible prices and money-back guarantee

Biological Factors

- People with bipolar disorder generally have problems with their moods, experiencing extreme highs and lows known as mania or hypomania, respectively.

- An individual with bipolar disorder may also develop problems with perception and thinking such as psychosis.

- They think of things that are not true otherwise known as delusions and hear or see things that are not physically present (hallucinations).

Getting help

Our writers will provide you with an essay sample written from scratch: any topic, any deadline, any instructions.

Cite this paper

Related essay topics.

Get your paper done in as fast as 3 hours, 24/7.

Related articles

Most popular essays

- Bipolar Disorder

- Helping Others

- Mental Illness

The biological model of psychology focuses on treating the underlying physical issues that might...

“No excellent soul is exempt from a mixture of madness.” Aristotle. The link between creativity...

- Human Brain

Approximately 1 in 5 people in the U.S. struggles with a mental illness every year, Hollywood is...

The memoir written by Dr. Kay Jamison, An Unquiet Mind, provides an in-depth look at an...

The research by Caldieraro et al. was designed to study the impact of psychosis on patients with...

The track I chose for this project was track two Psychological Influences of Abnormal Behavior....

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a condition that has several diagnoses. These are, Bipolar Ⅰ, Bipolar Ⅱ,...

Bipolar disorder is a debilitating mental illness that causes extreme fluctuation in mood. One...

- Human Behavior

Bipolar disorder, today, can be defined as a brain disorder that causes changes in a person’s mood...

Join our 150k of happy users

- Get original paper written according to your instructions

- Save time for what matters most

Fair Use Policy

EduBirdie considers academic integrity to be the essential part of the learning process and does not support any violation of the academic standards. Should you have any questions regarding our Fair Use Policy or become aware of any violations, please do not hesitate to contact us via [email protected].

We are here 24/7 to write your paper in as fast as 3 hours.

Provide your email, and we'll send you this sample!

By providing your email, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy .

Say goodbye to copy-pasting!

Get custom-crafted papers for you.

Enter your email, and we'll promptly send you the full essay. No need to copy piece by piece. It's in your inbox!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2019

Thought and language disturbance in bipolar disorder quantified via process-oriented verbal fluency measures

- Luisa Weiner 1 , 2 ,

- Nadège Doignon-Camus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0295-2801 1 ,

- Gilles Bertschy 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Anne Giersch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8577-6021 1

Scientific Reports volume 9 , Article number: 14282 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

22 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by speech abnormalities, reflected by symptoms such as pressure of speech in mania and poverty of speech in depression. Here we aimed at investigating speech abnormalities in different episodes of BD, including mixed episodes, via process-oriented measures of verbal fluency performance – i.e., word and error count, semantic and phonological clustering measures, and number of switches–, and their relation to neurocognitive mechanisms and clinical symptoms. 93 patients with BD – i.e., 25 manic, 12 mixed manic, 19 mixed depression, 17 depressed, and 20 euthymic–and 31 healthy controls were administered three verbal fluency tasks – free, letter, semantic–and a clinical and neuropsychological assessment. Compared to depression and euthymia, switching and clustering abnormalities were found in manic and mixed states, mimicking symptoms like flight of ideas. Moreover, the neuropsychological results, as well as the fact that error count did not increase whereas phonological associations did, showed that impaired inhibition abilities and distractibility could not account for the results in patients with manic symptoms. Rather, semantic overactivation in patients with manic symptoms, including mixed depression, may compensate for trait-like deficient semantic retrieval/access found in euthymia.

“For those who are manic, or those who have a history of mania, words move about in all directions possible, in a three-dimensional ‘soup’, making retrieval more fluid, less predictable.” Kay Redfield Jamison (2017, p. 279).

Similar content being viewed by others

Syntactic complexity and diversity of spontaneous speech production in schizophrenia spectrum and major depressive disorders

Altered language network lateralization in euthymic bipolar patients: a pilot study

Natural Language Processing markers in first episode psychosis and people at clinical high-risk

Introduction.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is characterized by acute episodes of mania and depression, mixed episodes wherein depressive and manic symptoms co-occur, and periods of partial or full remission, also called ‘euthymic states’. Language disturbances such as speech pressure or poverty are among the main symptoms of acute episodes in BD 1 , and may prevail during periods of remission 2 . While early studies focused on associational fluency as a measure of creativity and thinking style in mania 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , more recent studies have favored the use of verbal fluency tasks (VFT) with more restrained instructions (e.g., starting with a given letter or category) to tackle executive and language impairments mostly in euthymia, i.e., during periods of mood stabilization 8 . Here we investigated language disturbances, by means of both free and restrained VFT across different mood episodes of BD, to determine the contribution of clinical symptoms and executive functioning to word production in BD.

Different kinds of language disturbances have been described during mood episodes of BD. Pressure of speech, with increased rapidity of speech and racing thoughts, is a common symptom of mania, second only to elevated mood 9 . Manic speech has also been characterized as extremely combinatory, shifting quickly from one discourse structure to another, which authors have linked to distractibility and overactivation 10 . Other linguistic features frequently reported during manic episodes include increased verbosity 11 , and clang associations, i.e., associations based on sound rather than on the meaning of words 12 . In contrast, poverty of speech and increased pause times are common in depression, and have been hypothesized to be associated with psychomotor retardation and rumination 11 . In mixed episodes, linguistic features have been understudied, but phenomenological accounts suggest that patients may experience ‘disorganized flight of ideas’ 13 , distractibility and ‘crowded thoughts’ 14 , pressure and poverty of speech 15 . However, few empirical investigations have specifically addressed these thought and language abnormalities, whether in manic, depressed or mixed states. In particular, from a neurocognitive perspective, it is unclear whether manic speech is related to mechanisms such as semantic overactivation and deficient cognitive control.

VFT are widely used neuropsychological methods for studying language disorders 16 . In these tasks, subjects are instructed to generate words according to specified rules based on phonemic or semantic criteria (‘letter’ and ‘semantic’ fluency, respectively), or in the absence of a specified criterion (free word generation). Although traditionally only the total number of words produced within the allotted time period is considered, VFT are multi-faceted 17 , 18 . Indeed, it has been long known that semantically related words occur together as part of a burst of responding in recall protocols 19 . Qualitative process-oriented methods evolved based on findings relative to the dynamics of word retrieval in fluency and semantic memory tasks. Word output requires the integrity of both the storage and organization of concepts in lexico-semantic memory, and the ability to retrieve words from memory, thought to rely on executive functioning 17 . These processes underlie two aspects of word output that are responsible for optimal performance: the ability to produce words within semantic or phonological clusters, and the ability to shift to a new category, i.e., clustering and switching respectively 17 .

According to Troyer et al . 17 , clustering is defined by the production of words within semantic subcategories in the semantic fluency task (e.g., bird subcategory if the category is “animals”), and phonemic subcategories in the letter fluency task (e.g., words that rhyme). The clustering measure of interest is the cluster size, i.e. the number of words within each cluster. In their processing-oriented scoring procedure, Troyer et al . 17 considered task-consistent clustering, i.e., semantic relatedness in semantic fluency and phonemic relatedness in letter fluency. Switching was operationalized as the ability to shift from a subcategory to another. More recent qualitative scoring procedures have integrated ‘task-discrepant’ clustering, consisting of phonemic relatedness in semantic fluency or semantic relatedness in letter fluency 20 . ‘Task-discrepant’ means that when instructed to retrieve words from a given category (e.g. animals), retrieval might include phonologically-related successive words (e.g., cat and bat). Recent scoring procedures have also integrated a measure of cluster ratio (i.e., the number of clusters/number of words), arguing that mean cluster size is an ambiguous measure, as it reflects both the total number of words and the organization of the verbal output 21 . Hence the combined use of the mean cluster size and the cluster ratio is considered a better index of clustering, as it addresses respectively the integrity of lexico-semantic memory as well as retrieval organization throughout the task 22 , 23 .

In BD however, only the total word count has been considered. In a recent meta-analysis of VFT in BD, Raucher-Chéné et al . 8 found that performance in letter and semantic VFT was equally reduced in patients with BD. Most studies were conducted during euthymia (30 out of 39 studies), and only one study 24 included a group of patients in a mixed episode. Importantly, Raucher-Chéné et al . 8 found greater impairment in the semantic (but not letter) VFT in euthymic compared to manic patients. The authors argued that semantic memory dysfunction – i.e., storage and/or functional organization – could explain these results. Moreover, akin to formal thought disorder in schizophrenia, they speculated that the relative “manic advantage” in the semantic VFT was related to an over-activation of the semantic network, which supposedly underlies thought and language disturbances in mania 8 . That is, during manic episodes, the oral production of a given word might lead to faster than usual spreading of activation, hence facilitating the retrieval of more remotely associated words. If such is the case, cluster ratio should be reduced, and switches should be increased in manic and mixed groups compared to controls and euthymic and depressed bipolar groups.

Here we applied a comprehensive process-oriented method in patients with BD in five different mood episodes – i.e., mania, mixed mania, mixed depression, depression, and euthymia. To do so, total word count, but also measures of clustering and switching were calculated in three conditions of VFT – i.e., letter, semantic, and free condition: we calculated semantic and phonological cluster ratios (i.e., number of clusters/number of words), mean cluster sizes, and the raw number of switches. Consistent with earlier studies using associational paradigms 3 , 4 , we expected word production to be decreased in depressed patients and enhanced in patients with manic symptoms. The idiosyncratic combinatory and associational patterns (e.g., clanging) observed in mania 3 , 10 were expected to result in enhanced switches, and, possibly, diminished semantic clustering measures, and increased phonological clustering measures compared to healthy controls, euthymia and depression groups. We were particularly interested in the results of the mixed groups, given that distractibility is also a distinctive feature of mixed states 25 . Since linguistic abnormalities in BD were reported either in free speech or in associational fluency tasks, it was unclear, however, if they would still be observed in restricted conditions of VFT (letter or category). Because subjects have to follow specific retrieval rules, these tasks are considered more effortful 26 . Hence executive impairments and clinical symptoms such as distractibility and/or flight of ideas may result in the production of irrelevant words, i.e., errors. In contrast, if it is overactivation in patients with manic symptoms that subtends the peculiarities of manic speech instead of being the consequence of distractibility and overall executive dysfunction, then more switches should be observed while the production of irrelevant words remains stable in tasks with retrieval rules 27 .

Descriptive statistics

With the exception of working memory, performance in executive tasks was diminished in mania, mixed mania and depression compared to healthy controls. See Table 1 for detailed results on the neuropsychological tasks and the self-report questionnaires assessing clinical symptoms, i.e., racing thoughts and rumination, and the p significance level for the group effect.

Number of words

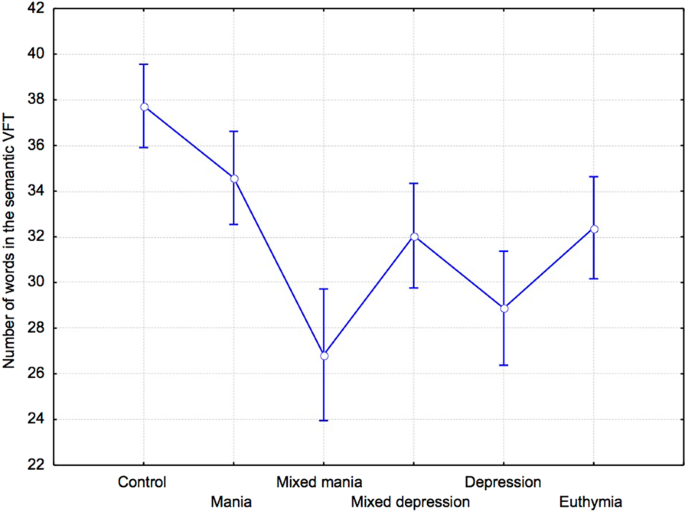

In the free condition and the letter condition, no significant difference was found in the number of words produced between groups, F(5,118) = 0.45, p = 0.81, η2 = 0.02, and F(5,118) = 0.72, p = 0.60, η2 = 0.04, respectively. In the semantic condition, the number of words produced among groups tended to differ, F(5,118) = 2.14, p = 0.07, η2 = 0.08 (Fig. 1 ). Planned comparisons revealed that the control and the manic groups tended to produce more animal words than the depressed group, F(1,118) = 4.13, p = 0.08, η2 = 0.1, and F(1,118) = 2.85, p = 0.09, η2 = 0.09, respectively. Number of errors did not differ between groups in the letter and semantic conditions, F(5,117) = 1.37, p = 0.25, η2 = 0.06, and F(5,117) = 0.80, p = 0.55, η2 = 0.03, respectively.

Number of words (mean and standard error) in the semantic VFT.

Cluster analyses

Semantic cluster size.

Average semantic cluster size did not differ between groups in the free, F(5,118) = 1.4, p = 0.23, η2 = 0.06, the semantic, F(5,118) = 1.4, p = 0.23, η2 = 0.06, and the letter conditions, F(5,117) = 1.56, p = 0.17, η2 = 0.06.

Ratio of semantic clusters

The ratio of semantic clusters did not differ between groups in the free, F(5,118) = 1.52, p = 0.19, η2 = 0.06, the letter, F(5,118) = 1.12, p = 0.36, η2 = 0.05, and the semantic conditions, F(5,118) = 0.97 p = 0.44, η2 = 0.42. Nevertheless, in the free condition, planned comparisons revealed that manic groups had significantly smaller cluster ratios than healthy controls, F(1,118) = 4.76, p = 0.03, η2 = 0.09, but not compared to the depressed group, F(1,118) = 0.78, p = 0.77, η2 = 0.02.

Phonological cluster size

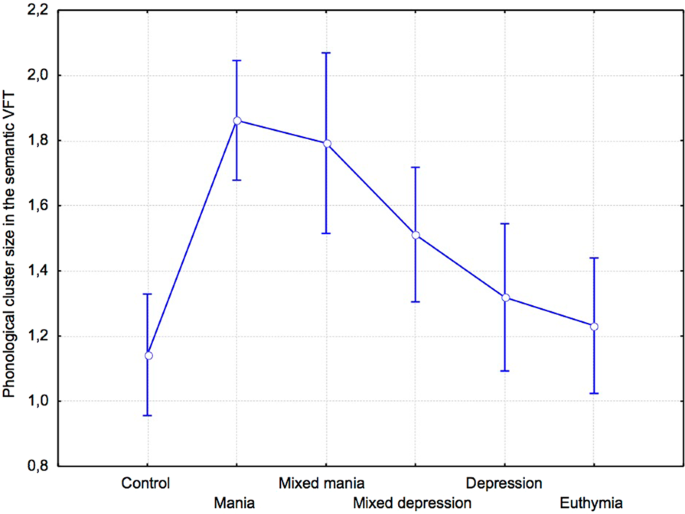

Average phonological cluster size did not differ between groups in the free, F(5,118) = 0.94, p = 0.45, η2 = 0.04, and in the letter condition, F(5,117) = 0.35, p = 0.89, η2 = 0.01. In the semantic condition, phonological cluster size tended to differ between groups, F(5,118) = 2.11, p = 0.07, η2 = 0.09 (Fig. 2 ). As expected, planned comparisons revealed that average phonological cluster size in the semantic condition was significantly increased in the manic compared to the control, F(1,118) = 6.2, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.1, and euthymic groups, F(1,118) = 5.29,p = 0.02, η2 = 0.1. Compared to depressed patients, the difference was only tendential, F(1,118) = 3.86, p = 0.07, η2 = 0.09.

Phonological cluster size (mean and standard error) in the semantic VFT.

Ratio of phonological clusters

The ratio of phonological clusters tended to differ in the free, F(5,118) = 1.91, p = 0.09, η2 = 0.08, and the letter conditions, F(5,117) = 2.3, p = 0.06, η2 = 0.09. In the semantic condition, the ratio of phonological clusters did not differ between groups, F(5,117) = 0.89, p = 0.49, η2 = 0.04.

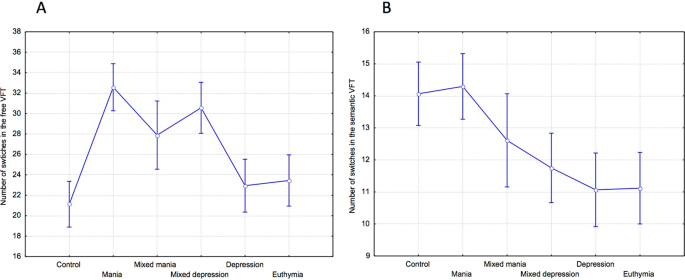

In the free condition, the number of switches differed significantly between groups, F(5,118) = 3.7, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.14 (Fig. 3A ). Planned comparisons showed that the number of switches was significantly increased in the manic group compared to the control, F(1,118) = 11.42, p < 0.0001, η2 = 0.26, the depressed groups, F(1,118) = 7.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.2, and the euthymic group, F(1,118) = 7.35, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.17. Compared to the depression group, switches were increased in the mixed depression group, F(1,118) = 4.65, p = 0.04, η2 = 0.11. In the letter and semantic conditions, there was no significant difference in the number of switches found among groups, F(5,117) = 0.48, p = 0.79, η2 = 0.02, and F(5,117) = 1.77, p = 0.12, η2 = 0.08, respectively (Fig. 3B ). In the semantic condition however, planned comparisons showed that the number of switches was significantly higher in the manic group compared to the depressed and euthymic groups, F(1,117) = 4.37, p = 0.04, η2 = 0.13, and F(1,117) = 4.5, p = 0.04, η2 = 0.13, respectively, but not the control group, F(1,117) = 0.004, p = 0.95, η2 < 0.001.

( A ) Number of switches (mean and standard error) in the free and ( B ) the semantic VFT.

Correlation and regression analyses

Correlation analyses were performed within the whole patient group (cf. Table 2 ). Increased working memory, executive functioning, and processing speed scores were related to greater verbal output in all verbal fluency tasks, whereas increased vocabulary score was only involved in semantic and letter fluency performance. Of note, similar patterns of correlations were found when the sample of patients with manic symptoms (n = 53)–i.e., mania, mixed mania and mixed depression–was considered alone (see Table 4 in supplementary information for detailed results). In addition, to investigate the relationship between process-oriented measures and word output in patients, we performed multiple regression analyses on the number of words produced in the three VFT. For the free condition, predictors accounted for 49% of the variance, with significant contributions from (i) semantic cluster size (β = 0.67, p < 0.001), (ii) ratio of semantic clusters (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), and (iii) number of switches (β = 0.37, p < 0.001). For the semantic condition, the predictors accounted for 50% of the variance, with significant effects of (i) semantic cluster size (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and (ii) number of switches (β = 0.58, p < 0.001). Regarding the letter condition, the predictors accounted for 76% of the variance, with significant contributions from (i) ratio of phonological clusters (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), and (ii) number of switches (β = 0.89, p < 0.001).

Racing thoughts, assessed via the RCTQ, were associated with decreased cluster ratios and fewer words in the letter and semantic conditions. Specifically, ‘thought overexcitability’, i.e., distractibility, was linked to decreased verbal output in these task conditions. Higher brooding rumination scores, assessed via the RRS, were associated with fewer words in the free and the semantic VFT. Phonological and semantic cluster sizes were larger when response times in the Hayling task were longer. In the free VFT, switches decreased when word suppression in the Hayling task was impaired, and they increased with faster processing speed.

Word and error count in VFT could not clearly distinguish between mood episodes in BD. Indeed, only the depression group tended to produce fewer words compared to healthy controls and manic patients in the semantic VFT. These results are consistent with those reported by Raucher-Chéne et al . 8 , suggesting greater impairment in the semantic VFT in subgroups of patients with BD. By contrast, the process-oriented measures proved to better capture the combinatory, tangential, and sound-based speech found in mania 10 . As a matter of fact, in the free condition, manic patients switched more often between semantic subcategories than the healthy and depression groups, and their semantic cluster ratio was also reduced. However, these results were not observed when the tasks had retrieval rules, i.e. letter and semantic conditions. In the semantic condition, switches were increased in the manic group compared only to the depression and euthymic groups, but not the healthy one. Interestingly, we found larger task-discrepant phonological cluster sizes in manic patients compared to controls. Despite this, the error count was similar between groups. In the mixed depression group, the number of switches in the free VFT was also higher than those found in non-mixed depression, suggesting that subthreshold manic symptoms led to discrete structural speech anomalies.

Consistent with a previous study by Fossati et al . 28 in unipolar depression, our results show reduced verbal output and switches in depressed patients, especially in the semantic VFT. Since this result was found in the semantic, but not the letter condition, this could be due either to a deterioration of the semantic system or to aberrant activation/inhibition processes within the semantic network 8 . Our results provide evidence against the storage deficit hypothesis, owing to the calculation of semantic cluster sizes which indexes semantic memory integrity. This index was not significantly different between groups, and vocabulary scores were equivalent between depression and healthy controls. Instead, in the semantic and free conditions, switching was decreased in the euthymic and the depression groups compared to the manic and healthy control groups, suggesting the existence of functional anomalies in the retrieval/access within the semantic system. Since results were similar in depression and euthymic groups, we argue that a trait-like impairment might be compensated for in the presence of manic symptoms 8 , 29 , 30 .

Interestingly, our results are the first to pinpoint switching abilities as affecting semantic fluency performance, and differently so among different types of mood episodes in BD. Like Fossati et al.’s findings 28 , switching was specifically correlated to measures of executive functions and psychomotor speed. Slower processing speed resulted in decreased switches in the semantic task, which might explain the results in depression and euthymia. As a whole, our results in bipolar depression are thus similar to those reported in unipolar depression 28 .

In contrast to depression, switches were increased in mania but also, to a lesser extent, in mixed depression. This was mainly observed in the free condition of VFT: subjects with mixed depression and mania, compared to depressed and euthymic patients, shifted from one discourse unit to the other at a faster rate, mimicking the flight of ideas characteristic of these states 10 . It is noteworthy however that increased switches did not amount to a greater number of words produced in the free VFT, despite the fact that cluster ratios and number of switches predicted the number of word output in all VFT. The stability of word output suggests that switches were increased at the expense of reduced semantic organization, as reflected by reduced cluster ratios in mania. All these results support the hypothesis of an abnormal access/retrieval within the semantic system might be involved in these results.

Indeed, a plausible explanation is that, in mania, there is a semantic overactivation during word retrieval. Clustering performance depends on the spread of semantic activation primed by each word generated 31 . Raucher-Chéné et al . 8 had already put forward the possibility of a faster than usual spread of semantic activation to explain the ‘manic advantage’ in VFT. This hypothesis is consistent with our results in the free task. In addition, the results in VFT with retrieval rules are also supportive of this hypothesis rather than overall inhibition deficits. Deficient inhibition of unrelated words should have led to a greater amount of errors, smaller cluster ratios and increased switches in constrained VFT, but this was not the case in patients with manic symptoms relative to healthy controls. Correlation analyses did not support a straightforward role of inhibition deficits either, as clustering measures increased and switches decreased when inhibition was impaired in the Hayling task 32 (see Supplementary Information).

The contrast between the results found in the free and the constrained VFT is striking, and the difference between these task conditions may be crucial to understand the mechanisms at play. In patients with manic symptoms, the unrestrictive nature of the free VFT may have enhanced diffuse semantic activation and favored the retrieval of more remotely associated words within the semantic network, which were not required to be inhibited in this task 26 . Hence, in the free condition, semantic overactivation was not detrimental to performance since subjects did not have to inhibit words unrelated to the task’s rules. A critical question is the role of distractibility. In the free task, it might have favored conceptual shifts, promoting the production of single words instead of clusters (i.e., reduced cluster ratio and increased switches) in patients with manic symptoms. However, distractibility might be detrimental to performance in tasks with retrieval rules, as suggested by the correlation between elevated racing thoughts, and its distractibility feature in particular (i.e., thought overexcitability), and decreased word output in restricted VFT. Yet again, this did not affect total word output in patients with manic symptoms. This, along with a similar error count, shows that patients with manic symptoms followed the tasks’ rules; that is, distractibility did not lead to irrelevant word production. Instead, the increased phonological cluster sizes in the semantic condition of VFT suggest that they are spontaneously more flexible. More specifically, when they had to produce animal names, manic subjects did so while rhyming and using other sound-based associations, akin to clanging, more than any other group. This is surprising given that phonological clustering is laborious and relies on executive functions 20 , 33 . However, enhanced executive functions in mania seems unlikely to explain our results, as executive performance was generally impaired in our manic group. Unrelated representations might rather be spontaneously activated through semantic spreading and subtend sound-based associations 34 , 35 . As emphasized above, semantic overactivation in mania might compensate for trait-like deficient word access/retrieval based on semantic cues.