Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis)

Mia Belle Frothingham

Author, Researcher, Science Communicator

BA with minors in Psychology and Biology, MRes University of Edinburgh

Mia Belle Frothingham is a Harvard University graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Sciences with minors in biology and psychology

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

There are about seven thousand languages heard around the world – they all have different sounds, vocabularies, and structures. As you know, language plays a significant role in our lives.

But one intriguing question is – can it actually affect how we think?

It is widely thought that reality and how one perceives the world is expressed in spoken words and are precisely the same as reality.

That is, perception and expression are understood to be synonymous, and it is assumed that speech is based on thoughts. This idea believes that what one says depends on how the world is encoded and decoded in the mind.

However, many believe the opposite.

In that, what one perceives is dependent on the spoken word. Basically, that thought depends on language, not the other way around.

What Is The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis?

Twentieth-century linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf are known for this very principle and its popularization. Their joint theory, known as the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis or, more commonly, the Theory of Linguistic Relativity, holds great significance in all scopes of communication theories.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that the grammatical and verbal structure of a person’s language influences how they perceive the world. It emphasizes that language either determines or influences one’s thoughts.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis states that people experience the world based on the structure of their language, and that linguistic categories shape and limit cognitive processes. It proposes that differences in language affect thought, perception, and behavior, so speakers of different languages think and act differently.

For example, different words mean various things in other languages. Not every word in all languages has an exact one-to-one translation in a foreign language.

Because of these small but crucial differences, using the wrong word within a particular language can have significant consequences.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is sometimes called “linguistic relativity” or the “principle of linguistic relativity.” So while they have slightly different names, they refer to the same basic proposal about the relationship between language and thought.

How Language Influences Culture

Culture is defined by the values, norms, and beliefs of a society. Our culture can be considered a lens through which we undergo the world and develop a shared meaning of what occurs around us.

The language that we create and use is in response to the cultural and societal needs that arose. In other words, there is an apparent relationship between how we talk and how we perceive the world.

One crucial question that many intellectuals have asked is how our society’s language influences its culture.

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir and his then-student Benjamin Whorf were interested in answering this question.

Together, they created the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which states that our thought processes predominantly determine how we look at the world.

Our language restricts our thought processes – our language shapes our reality. Simply, the language that we use shapes the way we think and how we see the world.

Since the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis theorizes that our language use shapes our perspective of the world, people who speak different languages have different views of the world.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a Yale University graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir, who was considered the father of American linguistic anthropology.

Sapir was responsible for documenting and recording the cultures and languages of many Native American tribes disappearing at an alarming rate. He and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between language and culture.

Anthropologists like Sapir need to learn the language of the culture they are studying to understand the worldview of its speakers truly. Whorf believed that the opposite is also true, that language affects culture by influencing how its speakers think.

His hypothesis proposed that the words and structures of a language influence how its speaker behaves and feels about the world and, ultimately, the culture itself.

Simply put, Whorf believed that you see the world differently from another person who speaks another language due to the specific language you speak.

Human beings do not live in the matter-of-fact world alone, nor solitary in the world of social action as traditionally understood, but are very much at the pardon of the certain language which has become the medium of communication and expression for their society.

To a large extent, the real world is unconsciously built on habits in regard to the language of the group. We hear and see and otherwise experience broadly as we do because the language habits of our community predispose choices of interpretation.

Studies & Examples

The lexicon, or vocabulary, is the inventory of the articles a culture speaks about and has classified to understand the world around them and deal with it effectively.

For example, our modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some vehicle – cars, buses, trucks, SUVs, trains, etc. We, therefore, have thousands of words to talk about and mention, including types of models, vehicles, parts, or brands.

The most influential aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the dictionary of its language. Among the societies living on the islands in the Pacific, fish have significant economic and cultural importance.

Therefore, this is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival.

For example, there are over 1,000 fish species in Palau, and Palauan fishers knew, even long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns, and habitat of most of them – far more than modern biologists know today.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with many Native American languages, including Hopi. He discovered that the Hopi language is quite different from English in many ways, especially regarding time.

Western cultures and languages view times as a flowing river that carries us continuously through the present, away from the past, and to the future.

Our grammar and system of verbs reflect this concept with particular tenses for past, present, and future.

We perceive this concept of time as universal in that all humans see it in the same way.

Although a speaker of Hopi has very different ideas, their language’s structure both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. Seemingly, the Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense; instead, they divide the world into manifested and unmanifest domains.

The manifested domain consists of the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past, and the future; the unmanifest domain consists of the remote past and the future and the world of dreams, thoughts, desires, and life forces.

Also, there are no words for minutes, minutes, or days of the week. Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English-speaking world when it came to being on time for their job or other affairs.

It is due to the simple fact that this was not how they had been conditioned to behave concerning time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun.

Today, it is widely believed that some aspects of perception are affected by language.

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis derives from the idea that if a person’s language has no word for a specific concept, then that person would not understand that concept.

Honestly, the idea that a mother tongue can restrict one’s understanding has been largely unaccepted. For example, in German, there is a term that means to take pleasure in another person’s unhappiness.

While there is no translatable equivalent in English, it just would not be accurate to say that English speakers have never experienced or would not be able to comprehend this emotion.

Just because there is no word for this in the English language does not mean English speakers are less equipped to feel or experience the meaning of the word.

Not to mention a “chicken and egg” problem with the theory.

Of course, languages are human creations, very much tools we invented and honed to suit our needs. Merely showing that speakers of diverse languages think differently does not tell us whether it is the language that shapes belief or the other way around.

Supporting Evidence

On the other hand, there is hard evidence that the language-associated habits we acquire play a role in how we view the world. And indeed, this is especially true for languages that attach genders to inanimate objects.

There was a study done that looked at how German and Spanish speakers view different things based on their given gender association in each respective language.

The results demonstrated that in describing things that are referred to as masculine in Spanish, speakers of the language marked them as having more male characteristics like “strong” and “long.” Similarly, these same items, which use feminine phrasings in German, were noted by German speakers as effeminate, like “beautiful” and “elegant.”

The findings imply that speakers of each language have developed preconceived notions of something being feminine or masculine, not due to the objects” characteristics or appearances but because of how they are categorized in their native language.

It is important to remember that the Theory of Linguistic Relativity (Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) also successfully achieves openness. The theory is shown as a window where we view the cognitive process, not as an absolute.

It is set forth to look at a phenomenon differently than one usually would. Furthermore, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis is very simple and logically sound. Understandably, one’s atmosphere and culture will affect decoding.

Likewise, in studies done by the authors of the theory, many Native American tribes do not have a word for particular things because they do not exist in their lives. The logical simplism of this idea of relativism provides parsimony.

Truly, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis makes sense. It can be utilized in describing great numerous misunderstandings in everyday life. When a Pennsylvanian says “yuns,” it does not make any sense to a Californian, but when examined, it is just another word for “you all.”

The Linguistic Relativity Theory addresses this and suggests that it is all relative. This concept of relativity passes outside dialect boundaries and delves into the world of language – from different countries and, consequently, from mind to mind.

Is language reality honestly because of thought, or is it thought which occurs because of language? The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis very transparently presents a view of reality being expressed in language and thus forming in thought.

The principles rehashed in it show a reasonable and even simple idea of how one perceives the world, but the question is still arguable: thought then language or language then thought?

Modern Relevance

Regardless of its age, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, or the Linguistic Relativity Theory, has continued to force itself into linguistic conversations, even including pop culture.

The idea was just recently revisited in the movie “Arrival,” – a science fiction film that engagingly explores the ways in which an alien language can affect and alter human thinking.

And even if some of the most drastic claims of the theory have been debunked or argued against, the idea has continued its relevance, and that does say something about its importance.

Hypotheses, thoughts, and intellectual musings do not need to be totally accurate to remain in the public eye as long as they make us think and question the world – and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis does precisely that.

The theory does not only make us question linguistic theory and our own language but also our very existence and how our perceptions might shape what exists in this world.

There are generalities that we can expect every person to encounter in their day-to-day life – in relationships, love, work, sadness, and so on. But thinking about the more granular disparities experienced by those in diverse circumstances, linguistic or otherwise, helps us realize that there is more to the story than ours.

And beautifully, at the same time, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis reiterates the fact that we are more alike than we are different, regardless of the language we speak.

Isn’t it just amazing that linguistic diversity just reveals to us how ingenious and flexible the human mind is – human minds have invented not one cognitive universe but, indeed, seven thousand!

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What is the Sapir‐Whorf hypothesis?. American anthropologist, 86(1), 65-79.

Whorf, B. L. (1952). Language, mind, and reality. ETC: A review of general semantics, 167-188.

Whorf, B. L. (1997). The relation of habitual thought and behavior to language. In Sociolinguistics (pp. 443-463). Palgrave, London.

Whorf, B. L. (2012). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT press.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

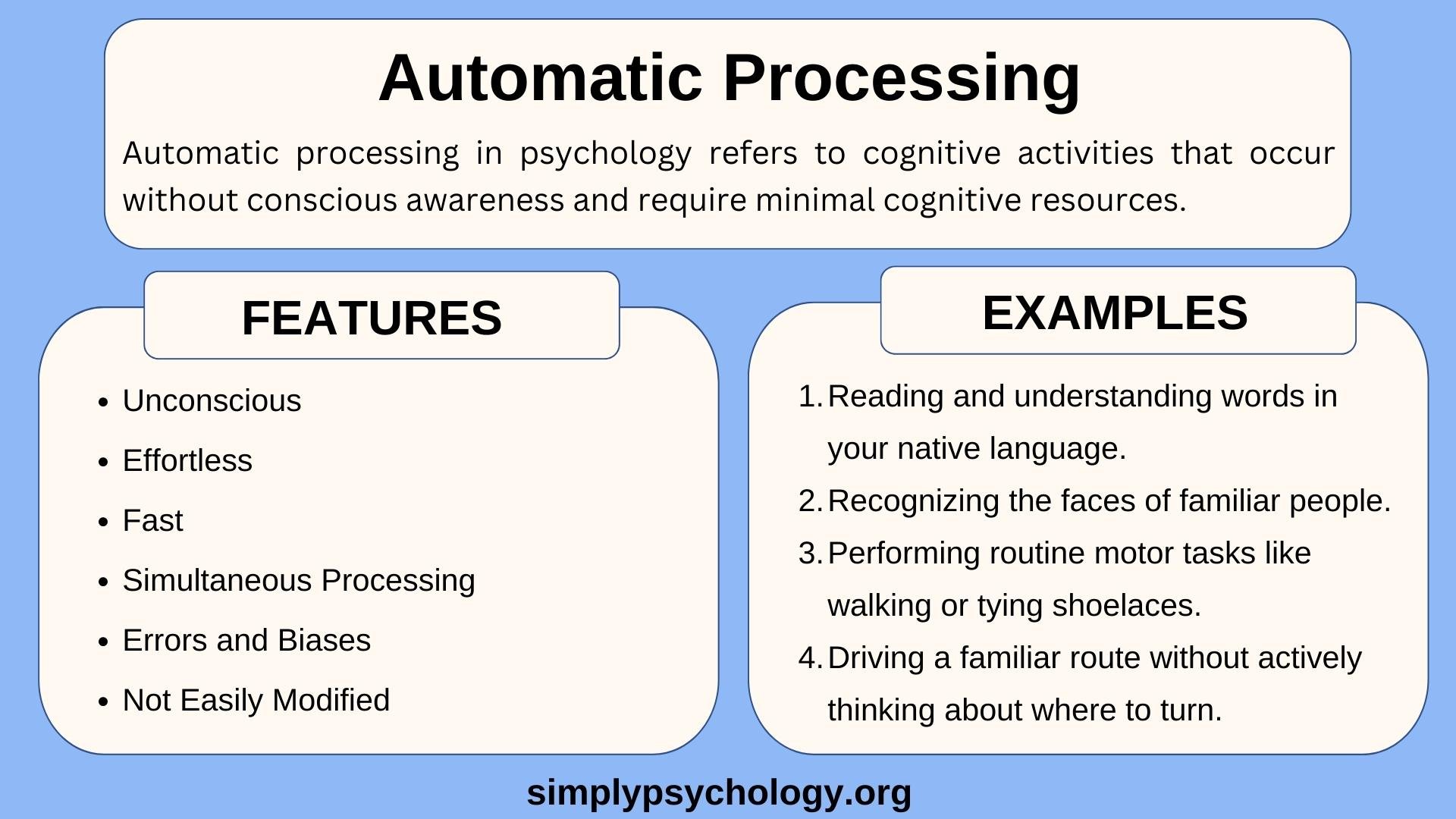

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

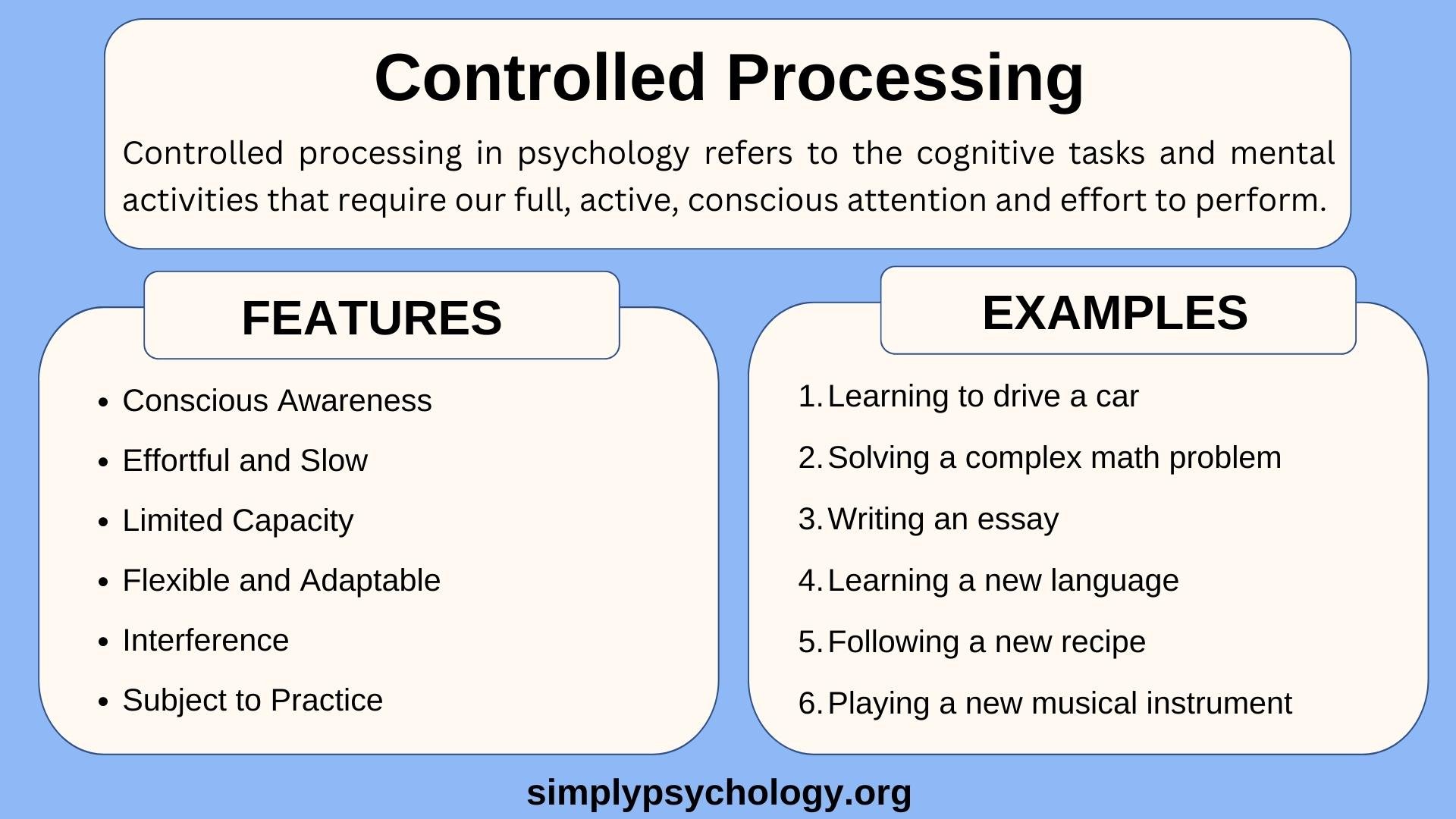

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: How Language Influences How We Express Ourselves

Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/RachaelGreenProfilePicture1-a3b8368ef3bb47ccbac92c5cc088e24d.jpg)

Thomas Barwick / Getty Images

What to Know About the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Real-world examples of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativity in psychology.

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, also known as linguistic relativity, refers to the idea that the language a person speaks can influence their worldview, thought, and even how they experience and understand the world.

While more extreme versions of the hypothesis have largely been discredited, a growing body of research has demonstrated that language can meaningfully shape how we understand the world around us and even ourselves.

Keep reading to learn more about linguistic relativity, including some real-world examples of how it shapes thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

The hypothesis is named after anthropologist and linguist Edward Sapir and his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. While the hypothesis is named after them both, the two never actually formally co-authored a coherent hypothesis together.

This Hypothesis Aims to Figure Out How Language and Culture Are Connected

Sapir was interested in charting the difference in language and cultural worldviews, including how language and culture influence each other. Whorf took this work on how language and culture shape each other a step further to explore how different languages might shape thought and behavior.

Since then, the concept has evolved into multiple variations, some more credible than others.

Linguistic Determinism Is an Extreme Version of the Hypothesis

Linguistic determinism, for example, is a more extreme version suggesting that a person’s perception and thought are limited to the language they speak. An early example of linguistic determinism comes from Whorf himself who argued that the Hopi people in Arizona don’t conjugate verbs into past, present, and future tenses as English speakers do and that their words for units of time (like “day” or “hour”) were verbs rather than nouns.

From this, he concluded that the Hopi don’t view time as a physical object that can be counted out in minutes and hours the way English speakers do. Instead, Whorf argued, the Hopi view time as a formless process.

This was then taken by others to mean that the Hopi don’t have any concept of time—an extreme view that has since been repeatedly disproven.

There is some evidence for a more nuanced version of linguistic relativity, which suggests that the structure and vocabulary of the language you speak can influence how you understand the world around you. To understand this better, it helps to look at real-world examples of the effects language can have on thought and behavior.

Different Languages Express Colors Differently

Color is one of the most common examples of linguistic relativity. Most known languages have somewhere between two and twelve color terms, and the way colors are categorized varies widely. In English, for example, there are distinct categories for blue and green .

Blue and Green

But in Korean, there is one word that encompasses both. This doesn’t mean Korean speakers can’t see blue, it just means blue is understood as a variant of green rather than a distinct color category all its own.

In Russian, meanwhile, the colors that English speakers would lump under the umbrella term of “blue” are further subdivided into two distinct color categories, “siniy” and “goluboy.” They roughly correspond to light blue and dark blue in English. But to Russian speakers, they are as distinct as orange and brown .

In one study comparing English and Russian speakers, participants were shown a color square and then asked to choose which of the two color squares below it was the closest in shade to the first square.

The test specifically focused on varying shades of blue ranging from “siniy” to “goluboy.” Russian speakers were not only faster at selecting the matching color square but were more accurate in their selections.

The Way Location Is Expressed Varies Across Languages

This same variation occurs in other areas of language. For example, in Guugu Ymithirr, a language spoken by Aboriginal Australians, spatial orientation is always described in absolute terms of cardinal directions. While an English speaker would say the laptop is “in front of” you, a Guugu Ymithirr speaker would say it was north, south, west, or east of you.

As a result, Aboriginal Australians have to be constantly attuned to cardinal directions because their language requires it (just as Russian speakers develop a more instinctive ability to discern between shades of what English speakers call blue because their language requires it).

So when you ask a Guugu Ymithirr speaker to tell you which way south is, they can point in the right direction without a moment’s hesitation. Meanwhile, most English speakers would struggle to accurately identify South without the help of a compass or taking a moment to recall grade school lessons about how to find it.

The concept of these cardinal directions exists in English, but English speakers aren’t required to think about or use them on a daily basis so it’s not as intuitive or ingrained in how they orient themselves in space.

Just as with other aspects of thought and perception, the vocabulary and grammatical structure we have for thinking about or talking about what we feel doesn’t create our feelings, but it does shape how we understand them and, to an extent, how we experience them.

Words Help Us Put a Name to Our Emotions

For example, the ability to detect displeasure from a person’s face is universal. But in a language that has the words “angry” and “sad,” you can further distinguish what kind of displeasure you observe in their facial expression. This doesn’t mean humans never experienced anger or sadness before words for them emerged. But they may have struggled to understand or explain the subtle differences between different dimensions of displeasure.

In one study of English speakers, toddlers were shown a picture of a person with an angry facial expression. Then, they were given a set of pictures of people displaying different expressions including happy, sad, surprised, scared, disgusted, or angry. Researchers asked them to put all the pictures that matched the first angry face picture into a box.

The two-year-olds in the experiment tended to place all faces except happy faces into the box. But four-year-olds were more selective, often leaving out sad or fearful faces as well as happy faces. This suggests that as our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

But some research suggests the influence is not limited to just developing a wider vocabulary for categorizing emotions. Language may “also help constitute emotion by cohering sensations into specific perceptions of ‘anger,’ ‘disgust,’ ‘fear,’ etc.,” said Dr. Harold Hong, a board-certified psychiatrist at New Waters Recovery in North Carolina.

As our vocabulary for talking about emotions expands, so does our ability to understand and distinguish those emotions.

Words for emotions, like words for colors, are an attempt to categorize a spectrum of sensations into a handful of distinct categories. And, like color, there’s no objective or hard rule on where the boundaries between emotions should be which can lead to variation across languages in how emotions are categorized.

Emotions Are Categorized Differently in Different Languages

Just as different languages categorize color a little differently, researchers have also found differences in how emotions are categorized. In German, for example, there’s an emotion called “gemütlichkeit.”

While it’s usually translated as “cozy” or “ friendly ” in English, there really isn’t a direct translation. It refers to a particular kind of peace and sense of belonging that a person feels when surrounded by the people they love or feel connected to in a place they feel comfortable and free to be who they are.

Harold Hong, MD, Psychiatrist

The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion.

You may have felt gemütlichkeit when staying up with your friends to joke and play games at a sleepover. You may feel it when you visit home for the holidays and spend your time eating, laughing, and reminiscing with your family in the house you grew up in.

In Japanese, the word “amae” is just as difficult to translate into English. Usually, it’s translated as "spoiled child" or "presumed indulgence," as in making a request and assuming it will be indulged. But both of those have strong negative connotations in English and amae is a positive emotion .

Instead of being spoiled or coddled, it’s referring to that particular kind of trust and assurance that comes with being nurtured by someone and knowing that you can ask for what you want without worrying whether the other person might feel resentful or burdened by your request.

You might have felt amae when your car broke down and you immediately called your mom to pick you up, without having to worry for even a second whether or not she would drop everything to help you.

Regardless of which languages you speak, though, you’re capable of feeling both of these emotions. “The lack of a word for an emotion in a language does not mean that its speakers don't experience that emotion,” Dr. Hong explained.

What This Means For You

“While having the words to describe emotions can help us better understand and regulate them, it is possible to experience and express those emotions without specific labels for them.” Without the words for these feelings, you can still feel them but you just might not be able to identify them as readily or clearly as someone who does have those words.

Rhee S. Lexicalization patterns in color naming in Korean . In: Raffaelli I, Katunar D, Kerovec B, eds. Studies in Functional and Structural Linguistics. Vol 78. John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2019:109-128. Doi:10.1075/sfsl.78.06rhe

Winawer J, Witthoft N, Frank MC, Wu L, Wade AR, Boroditsky L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(19):7780-7785. 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lindquist KA, MacCormack JK, Shablack H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism . Front Psychol. 2015;6. Doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00444

By Rachael Green Rachael is a New York-based writer and freelance writer for Verywell Mind, where she leverages her decades of personal experience with and research on mental illness—particularly ADHD and depression—to help readers better understand how their mind works and how to manage their mental health.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Science Struck

Understanding Linguistic Relativity Hypothesis with Examples

Linguistic relativity, also known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, holds that the structure of the language natively spoken by people defines the way they view the world and interact with it. This post helps you understand this concept with the help of examples.

Like it? Share it!

“The diversity of languages is not a diversity of signs and sounds but a diversity of views of the world.” – Wilhelm von Humboldt

The linguistic relativity hypothesis posits that languages mold our cognitive faculties and determine the way we behave and interact in society. This hypothesis is also called the Sapir-Wharf hypothesis, which is actually a misnomer since Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf never co-authored the theory. Rather, the theory was derived from the academic writings of Whorf, under the mentorship of Sapir. Hence the hypothesis is referred to as the principle of linguistic relativity. This nomenclature also acknowledges the fact that Sapir and Whorf were not the only ones to describe a link between thought and language, and also implies the existence of other chain of thoughts regarding this concept.

This theory has been widely mentioned in various diverse branches of social and behavioral sciences such as anthropology, linguistics, psychology, etc, but despite this, the validity of the theory is being disputed till date. Some scholars claim it to be trivially true, while others believe it to be refuted. To determine the validity and the logic behind the theory, one must therefore place the hypothesis within its historical context, find supporting empirical research finding, and finally examine the theoretical explanations and examples used to explain the relation between language and thought.

Linguistic Relativity: Hypothesis

The hypothesis presents two versions of the main principle – a strong version and a weak version. These versions arise from the way Sapir and Wharf have phrased and presented their ideas with the use of strong and weak words. The two versions of the hypothesis are as follows.

Strong Version – Language determines thought and controls the cognitive processes (linguistic determinism).

Weak version – Structure and usage of language influences thought and behavior (linguistic relativity).

The strong version of the hypothesis has largely been refuted, but the weaker versions are still being researched and debated as they often tend to produce positive empirical results.

Linguistic Relativity: Historical Context

♦ The possibility of thought being influenced by the language one spoke has sparked many a debates in various classical civilizations. In the Indian linguistic scholars, Bhartrihari (600 A.D.) was a major proponent on the relativistic nature of language. This same theory was also highly debated in ancient Greece between Plato and sophist thinkers such as Gorgias of Leontini. Plato believed that the world consisted of a pre-given set of ideas that were merely translated by language, whereas Gorgias held the belief that ones experience of the physical worlds was a direct function of language usage.

♦ The first clear idea of linguistic relativism was given in the early 19 th century by the German romantic philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt. He proposed that language was the fabric of thought, and that one’s thoughts were produced as a result of an internal dialog of a person in their native language. He also proposed that Indo-European languages such as German and English, that had the same basic syntax and structure were perfect languages, and that the speakers of such languages had a natural dominance over the speakers of other not-so-perfect languages.

♦ With this ideology in view, the American linguist William Dwight Whitney, in the 20 th century tried to eradicate the Native American languages by claiming that their speakers were savages and would be greatly benefited if they accepted English as the choice of language and chose a civilized way of life.

♦ Franz Boas was the first linguist to challenge this school of thought. He advocated equality between all cultures and languages. He did not believe in some languages being superior than others, but that all languages were equally capable of expressing any content but the way and means of expression differed. His student, Edward Sapir, believed in Humboldt’s idea that languages were the key to identify and understand the different ways in which different people viewed the world, and he improved on the idea and proposed that no two languages were ever similar enough to be perfectly translated, and that speakers of different languages would perceive reality differently. Despite this belief he strongly rejected the idea of linguistic determinism, claiming that it would be naive to believe that his experience of the world is solely dependent on the pattern and type of language he spoke.

♦ His vague notion of linguistic relativity was taken up and studied further by his student, Benjamin Lee Whorf. He studied Native American languages, to prove that differences in grammatical systems of a language and its usage had a major effect on the way the speakers perceived the world. He also explained how scientific accounts of event differed from religious accounts of the same events. He explained his theories in the form of examples rather than in an argumentative form, to showcase the differences observed in behavior on use of different languages. He also claimed that certain exotic words referred to exotic meanings that were rather untranslatable.

♦ Roger Brown and Eric Lenneberg widely criticized Whorf’s ideas and attempted to test them. They formulated his inferences into a testable hypothesis, which they named the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

Linguistic Relativity: Empirical Research

Structure-centered Research – It involves the study of structural peculiarities in a language and the possible consequences it has on the thought process and behavior of the speaker. For example, the Hopi language expresses and describes time in a manner different from that of English, and hence the Hopi people perceive time differently than others.

Domain-centered Research – This involves choosing a semantic domain and comparing it across a wide range of different languages, to determine its relation to behavior. A common example of this type is, research on color terminologies or spatial categories in different languages.

Behavior-centered Research – This deals with studying various types of behavior among diverse linguistic groups and attempting to establish a viable cause for the development of that behavior.

Linguistic Relativity: Languages

Some philosophers have hypothesized that if our perceptions are influenced by language, it may be possible to influence thought by conscious manipulation of language. This has eventually led to the development of neurolinguistic programming, which is a therapeutic approach towards the use of language to seek and influence cognitive patterns and processes.

Artificial Languages

The same philosophy has given rise to the possibility of generating a new and better language that could enable newer and better ways of thinking. One such language is Loglan, created by James Cooke Brown in an attempt to test this possibility. The speakers of Loglan claim that the language increases their logical thinking skill.

Another such language was created by Suzette Haden Elgin, and it was called Láadan. It was designed to easily express a feminist world view. The language Ithkuil, designed and created by John Quijada, tries to use multiple cognitive categories at a single time, while simultaneously keeping its speakers aware of this.

Programming Languages

Kenneth E. Iverson, the originator of the APL programming language, proposes that the use of powerful notations in a programming language, enhances one’s ability to think about computer algorithms. Also a blub paradox comes into play in connection with linguistic relativity and use of programming languages. It states that any programmer using a particular programming language will be aware of the languages that are inferior to the one he is using, but will be oblivious of the languages that are superior to the language being used by him. The reasoning behind this paradox is that while a programmer is programming in a language, he starts thinking in that language as well, and is satisfied with it, as the language in turn dictates their opinion of the programs being produced.

Linguistic Relativity: Criticism

♦ Linguistic philosophers like Eric Lenneberg, Noam Chomsky, and Steven Pinker have criticized the Whorfian hypothesis and do not accept most of the inferences about language and behavior put forth by Whorf. They claim that his conclusions are speculative since they are based on anecdotal evidence and not on results of empirical studies.

♦ Another criticism that this hypothesis faces is the problem of translatability. According to his theories, every language is unique in its description of reality. This would make translation of one language into another practically impossible. However, languages are regularly translated into each other every day, and hence challenges Whorf’s inference.

Linguistic Relativity: Examples

♦ Whorf observed two rooms at an gasoline plant. One room contained filled gasoline drums, while the other contained empty gasoline drums. The workers had a more relaxed and casual attitude toward the room housing the empty drums, and were seen to indulge in smoking in that room. The word “empty” may have suggested that the situation poses no harm, when in fact, smoking near the empty drums is also perilous, as they still contain leftover flammable vapors of gasoline.

♦ At a factory, metal containers were coated on the outside with spun limestone. Since the word “stone” was associated, the workers did not keep them away from heat or fire. Since spun limestone is a flammable substance, the workers were taken by surprise when the containers that were lined with “stone” caught fire.

♦ The Hopi language has one word to describe three different things. The same word implies an insect, an aviator, and an airplane. Hence, if a Hopi speaker witnesses an insect flying near an aviator, while looking at an airplane, she would claim to have seen the same thing (word) thrice, whereas an English speaker would describe it as seeing three different things.

With the current trend of people learning and excelling at languages that are not natively spoken by them, the concept of bilinguism has emerged. Since bilinguists can perceive and express experiences in native and foreign languages, the possibility of a unique perspective emerges and is interesting to study from a cognitive point of view.

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Privacy overview.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: Examples, Definition, Criticisms

Gregory Paul C. (MA)

Gregory Paul C. is a licensed social studies educator, and has been teaching the social sciences in some capacity for 13 years. He currently works at university in an international liberal arts department teaching cross-cultural studies in the Chuugoku Region of Japan. Additionally, he manages semester study abroad programs for Japanese students, and prepares them for the challenges they may face living in various countries short term.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Developed in 1929 by Edward Sapir, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity ) states that a person’s perception of the world around them and how they experience the world is both determined and influenced by the language that they speak.

The theory proposes that differences in grammatical and verbal structures, and the nuanced distinctions in the meanings that are assigned to words, create a unique reality for the speaker. We also call this idea the linguistic determinism theory .

Spair-Whorf Hypothesis Definition and Overview

Cibelli et al. (2016) reiterate the tenets of the hypothesis by stating:

“…our thoughts are shaped by our native language, and that speakers of different languages therefore think differently”(para. 1).

Kay & Kempton (1984) explain it a bit more succinctly. They explain that the hypothesis itself is based on the:

“…evolutionary view prevalent in 19 th century anthropology based in both linguistic relativity and determinism” (pp. 66, 79).

Linguist Edward Sapir, an American linguist who was interested in anthropology , studied at Yale University with Benjamin Whorf in the 1920’s.

Sapir & Whorf began to consider lexical and grammatical patterns and how these factored into the construction of different culture’s views of the world around them.

For example, they compared how thoughts and behavior differed between English speakers and Hopi language speakers in regard to the concept of time, arguing that in the Hopi language, the absence of the future tense has significant relevance (Kay & Kempton, 1984, p. 78-79).

Whorf (2021), in his own words, asserts:

“Every language is a vast pattern-system, different from others, in which are culturally ordained the forms and categories by which the personality not only communicates, but also analyzes nature, notices or neglects types of relationship and phenomena, channels his reasoning, and builds the house of his consciousness” (p. 252).

10 Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Examples

- Constructions of food in language: A language may ascribe many words to explain the same concept, item, or food type. This shows that they perceive it as extremely important in their society, in comparison to a culture whose language only has one word for that same concept, item, or food.

- Descriptions of color in language: Different cultures may visually perceive colors in different ways according to how the colors are described by the words in their language.

- Constructions of gender in language: Many languages are “gendered”, creating word associations that pertain to the roles of men or women in society.

- Perceptions of time in language: Depending upon how the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time.

- Categorization in language: The ways concepts and items in a given culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

- Politeness is encoded in language: Levels of politeness in a language and the pronoun combinations to express these levels differ between languages. How languages express politeness with words can dictate how they perceive the world around them.

- Indigenous words for snow: A popular example used to justify this hypothesis is the Inuit people, who have a multitude of ways to express the word snow. If you follow the reasoning of Sapir, it would suggest that the Inuits have a profoundly deeper understanding of snow than other cultures.

- Use of idioms in language: An expression or well-known saying in one culture has an acute meaning implicitly understood by those that speak the particular language but is not understandable when expressed in another language.

- Values are engrained in language: Each country and culture have beliefs and values as a direct result of the language it uses.

- Slang in language: The slang used by younger people evolves from generation to generation in all languages. Generational slang carries with it perceptions and ideas about the world that members of that generation share.

See Other Hypothesis Examples Here

Two Ways Language Shapes Perception

1. perception of categories and categorization.

How concepts and items in a culture are categorized (and what words are assigned to them) can affect the speaker’s perception of the world around them.

Although the examples of this phenomenon are too numerous to cite, a clear example is the extremely contextual, nuanced, and hyper-categorized Japanese language.

In the English language, the concept of “you” and “I” is narrowed to these two forms. However, Japanese has numerous ways to express you and I, each having various levels of politeness and appropriateness in relation to age, gender, and stature in society.

While in common conversation, the pronoun is often left out of the conversation – reliant on context, misuse or omission of the proper pronoun can be perceived as rude or ill-mannered.

In other ways, the complexity of the categorical lexicons can often leave English speakers puzzled. This could come in the form of classifications of different shaped bowls and plates that serve different functions; it could be traces of the ancient Japanese calendar from the 7 th Century, that possessed 72 micro-seasons during a year, or any number of sub-divided word listings that may be considered as one blanket term in another language.

Masuda et al. (2017) gives a clear example:

“ People conceptualize objects along the lines drawn between existing categories in their native language. That is, if two concepts fall into the same linguistic category, the perception of similarity between these objects would be stronger than if the two concepts fall into different linguistic categories.”

They then go on to give the example of how Japanese vs English speakers might categorize an everyday object – the bell:

“For example, in Japanese, the kind of bell found in a bell tower generally corresponds to the word kane—a large bell—which is categorically different from a small bell, suzu. However, in English, these two objects are considered to belong within the same linguistic category, “bell.” Therefore, we might expect English speakers to perceive these two objects as being more similar than would Japanese speakers (para 5).

2. Perception of the Concept of Time

According to a way the tenses are structured in a language, it may dictate how the people that speak that language perceive the concept of time

One of Sapir’s most famous applications of his theory is to the language of the Arizona Native American Hopi tribe.

He claimed, although refuted vehemently by linguistic scholars since, that they have no general notion of time – that they cannot decipher between the past, present, or future because of the grammatical structures that are used within their language.

As Engle (2016) asserts, Sapir believed that the Hopi language “encodes on ordinal value, rather than a passage of time”.

He concluded that, “a day followed by a night is not so much a new day, but a return to daylight” (p. 96).

However, it is not only Hopi culture that has different perception of time imbedded in the language; Thai culture has a non-linear concept of time, and the Malagasy people of Madagascar believe that time in motion around human beings, not that human beings are passing through time (Engle, 2016, p. 99).

Criticism of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

1. language as context-dependent.

Iwamoto (2005) expresses that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis fails to recognize that language is used within context. Its purely decontextualized textual analysis of language is too one-dimensional and doesn’t consider how we actually use language:

“Whorf’s “neat and simplistic” linguistic relativism presupposes the idea that an entire language or entire societies or cultures are categorizable or typable in a straightforward, discrete, and total manner, ignoring other variables such as contextual and semantic factors .” (Iwamoto, 2005, p. 95)

2. Not universally applicable

Another criticism of the hypothesis is that Sapir & Whorf’s hypothesis cannot be transferred or applied to all languages.

It is difficult to cite empirical studies that confirm that other cultures do not also have similarities in the way concepts are perceived through their language – even if they don’t possess a similar word/expression for a particular concept that is expressed.

3. thoughts can be independent of language

Stephen Pinker, one of Sapir & Whorf’s most emphatic critics, would argue that language is not of our thoughts, and is not a cultural invention that creates perceptions; it is in his opinion, a part of human biology (Meier & Pinker, 1995, pp. 611-612).

He suggests that the acquisition and development of sign language show that languages are instinctual, therefore biological; he even goes so far as to say that “all speech is an illusion”(p. 613).

Cibelli, E., Xu, Y., Austerweil, J. L., Griffiths, T. L., & Regier, T. (2016). The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and Probabilistic Inference: Evidence from the Domain of Color. PLOS ONE , 11 (7), e0158725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158725

Engle, J. S. (2016). Of Hopis and Heptapods: The Return of Sapir-Whorf. ETC.: A Review of General Semantics , 73 (1), 95. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-544562276/of-hopis-and-heptapods-the-return-of-sapir-whorf

Iwamoto, N. (2005). The Role of Language in Advancing Nationalism. Bulletin of the Institute of Humanities , 38 , 91–113.

Meier, R. P., & Pinker, S. (1995). The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Language , 71 (3), 610. https://doi.org/10.2307/416234

Masuda, T., Ishii, K., Miwa, K., Rashid, M., Lee, H., & Mahdi, R. (2017). One Label or Two? Linguistic Influences on the Similarity Judgment of Objects between English and Japanese Speakers. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01637

Kay, P., & Kempton, W. (1984). What Is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis? American Anthropologist , 86 (1), 65–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/679389

Whorf, B. L. (2021). Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf . Hassell Street Press.

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Social Penetration Theory: Examples, Phases, Criticism

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Upper Middle-Class Lifestyles: 10 Defining Features

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Arousal Theory of Motivation: Definition & Examples

- Gregory Paul C. (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Theory of Mind: Examples and Definition

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Linguistic Relativity

Introduction, edited collections.

- Reference Resources

- Foundational Works

- Theoretical Perspectives

- Object-Substance

- Object-Substance and Acquisition

- Kinds and Categories

- Grammatical Number

- Tight-Fit, Loose-Fit

- Path-Manner

- Frames of Reference

- Reorientation

- Theory of Mind

- Grammatical Gender

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Contrastive Analysis in Linguistics

- Critical Applied Linguistics

- Cross-Cultural Pragmatics

- Educational Linguistics

- Edward Sapir

- Generative Syntax

- Georg von der Gabelentz

- Languages of the World

- Linguistic Complexity

- Positive Discourse Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Synesthesia and Language

- Translation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Sentence Comprehension

- Text Comprehension

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Linguistic Relativity by Peggy Li , David Barner LAST REVIEWED: 28 October 2011 LAST MODIFIED: 28 October 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0026

Linguistic relativity, sometimes called the Whorfian hypothesis, posits that properties of language affect the structure and content of thought and thus the way humans perceive reality. A distinction is often made between strong Whorfian views, according to which the categories of thought are determined by language, and weak views, which argue that language influences thought without entirely determining its structure. Each view presupposes that for language to affect thought, the two must in some way be separable. The modern investigation of linguistic relativity began with the contributions of Benjamin Lee Whorf and his mentor, Edward Sapir. Until recently, much experimental work has focused on determining whether any reliable Whorfian effects exist and whether effects truly reflect differences in thought caused by linguistic variation. Many such studies compare speakers of different languages or test subjects at different stages of language acquisition. Other studies explore how language affects cognition by testing prelinguistic infants or nonhuman animals and comparing these groups to children or adults. Significant progress has been made in several domains, including studies of color, number, objects, and space. In many areas, the status of findings is hotly debated.

Often, leading researchers in the field summarize their newest findings and views in edited collections. These volumes are good places to begin research into the topic of linguistic relativity. The listed volumes arose from papers presented at conferences, symposia, and workshops devoted to the topic. Gumperz and Levinson 1996 arose from a symposium that revived interest in the linguistic relativity hypothesis, leading to a wave of new research on the topic. Highlights of this work are reported in Bowerman and Levinson 2001 , Gentner and Goldin-Meadow 2003 , and Malt and Wolff 2010 .

Bowerman, Melissa, and Stephen C. Levinson, eds. 2001. Language acquisition and conceptual development . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511620669

This volume brings together research on language acquisition and conceptual development and asks about the relation between them in early childhood.

Gentner, Dedre, and Susan Goldin-Meadow, eds. 2003. Language in mind: Advances in the study of language and thought . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

The volume starts with a collection of perspective papers and then showcases papers that bring data to bear to test claims of linguistic relativity. The papers are delineated on the basis of the types of language effects on thought: language as a tool kit, language as a lens, and language as a category maker.

Gumperz, John J., and Stephen C. Levinson, eds. 1996. Rethinking linguistic relativity . Papers presented at the Werner-Gren Symposium 112, held in Ocho Rios, Jamaica, in May 1991. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

A collection of papers arising from the “Rethinking Linguistic Relativity” Wenner-Gren Symposium in 1991 that brought about renewed interest in the topic.

Malt, Barbara C., and Phillip M. Wolff. 2010. Words and the mind: How words capture human experience . Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Researchers across disciplines (linguists, psychologists, and anthropologists) contributed to this collection of papers documenting new advances in language-thought research in various domains (space, emotions, body parts, causation, etc.).

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Linguistics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Acceptability Judgments

- Accessibility Theory in Linguistics

- Acquisition, Second Language, and Bilingualism, Psycholin...

- Adpositions

- African Linguistics

- Afroasiatic Languages

- Algonquian Linguistics

- Altaic Languages

- Ambiguity, Lexical

- Analogy in Language and Linguistics

- Animal Communication

- Applicatives

- Applied Linguistics, Critical

- Arawak Languages

- Argument Structure

- Artificial Languages

- Australian Languages

- Austronesian Linguistics

- Auxiliaries

- Balkans, The Languages of the

- Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan

- Berber Languages and Linguistics

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- Biology of Language

- Borrowing, Structural

- Caddoan Languages

- Caucasian Languages

- Celtic Languages

- Celtic Mutations

- Chomsky, Noam

- Chumashan Languages

- Classifiers

- Clauses, Relative

- Clinical Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Colonial Place Names

- Comparative Reconstruction in Linguistics

- Comparative-Historical Linguistics

- Complementation

- Complexity, Linguistic

- Compositionality

- Compounding

- Computational Linguistics

- Conditionals

- Conjunctions

- Connectionism

- Consonant Epenthesis

- Constructions, Verb-Particle

- Conversation Analysis

- Conversation, Maxims of

- Conversational Implicature

- Cooperative Principle

- Coordination

- Creoles, Grammatical Categories in

- Critical Periods

- Cross-Language Speech Perception and Production

- Cyberpragmatics

- Default Semantics

- Definiteness

- Dementia and Language

- Dene (Athabaskan) Languages

- Dené-Yeniseian Hypothesis, The

- Dependencies

- Dependencies, Long Distance

- Derivational Morphology

- Determiners

- Dialectology

- Distinctive Features

- Dravidian Languages

- Endangered Languages

- English as a Lingua Franca

- English, Early Modern

- English, Old

- Eskimo-Aleut

- Euphemisms and Dysphemisms

- Evidentials

- Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics

- Existential

- Existential Wh-Constructions

- Experimental Linguistics

- Fieldwork, Sociolinguistic

- Finite State Languages

- First Language Attrition

- Formulaic Language

- Francoprovençal

- French Grammars

- Gabelentz, Georg von der

- Genealogical Classification

- Genetics and Language

- Grammar, Categorial

- Grammar, Cognitive

- Grammar, Construction

- Grammar, Descriptive

- Grammar, Functional Discourse

- Grammars, Phrase Structure

- Grammaticalization

- Harris, Zellig

- Heritage Languages

- History of Linguistics

- History of the English Language

- Hmong-Mien Languages

- Hokan Languages

- Humor in Language

- Hungarian Vowel Harmony

- Idiom and Phraseology

- Imperatives

- Indefiniteness

- Indo-European Etymology

- Inflected Infinitives

- Information Structure

- Interface Between Phonology and Phonetics

- Interjections

- Iroquoian Languages

- Isolates, Language

- Jakobson, Roman

- Japanese Word Accent

- Jones, Daniel

- Juncture and Boundary

- Khoisan Languages

- Kiowa-Tanoan Languages

- Kra-Dai Languages

- Labov, William

- Language Acquisition

- Language and Law

- Language Contact

- Language Documentation

- Language, Embodiment and

- Language for Specific Purposes/Specialized Communication

- Language, Gender, and Sexuality

- Language Geography

- Language Ideologies and Language Attitudes

- Language in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Language Nests

- Language Revitalization

- Language Shift

- Language Standardization

- Language, Synesthesia and

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of the Americas, Indigenous

- Learnability

- Lexical Access, Cognitive Mechanisms for

- Lexical Semantics

- Lexical-Functional Grammar

- Lexicography

- Lexicography, Bilingual

- Linguistic Accommodation

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Areas

- Linguistic Landscapes

- Linguistic Prescriptivism

- Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Educational

- Listening, Second Language

- Literature and Linguistics

- Machine Translation

- Maintenance, Language

- Mande Languages

- Mass-Count Distinction

- Mathematical Linguistics

- Mayan Languages

- Mental Health Disorders, Language in

- Mental Lexicon, The

- Mesoamerican Languages

- Minority Languages

- Mixed Languages

- Mixe-Zoquean Languages

- Modification

- Mon-Khmer Languages

- Morphological Change

- Morphology, Blending in

- Morphology, Subtractive

- Munda Languages

- Muskogean Languages

- Nasals and Nasalization

- Niger-Congo Languages

- Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages

- Northeast Caucasian Languages

- Oceanic Languages

- Papuan Languages

- Penutian Languages

- Philosophy of Language

- Phonetics, Acoustic

- Phonetics, Articulatory

- Phonological Research, Psycholinguistic Methodology in

- Phonology, Computational

- Phonology, Early Child

- Policy and Planning, Language

- Politeness in Language

- Possessives, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Cognitive

- Pragmatics, Computational

- Pragmatics, Cross-Cultural

- Pragmatics, Developmental

- Pragmatics, Experimental

- Pragmatics, Game Theory in

- Pragmatics, Historical

- Pragmatics, Institutional

- Pragmatics, Second Language

- Pragmatics, Teaching

- Prague Linguistic Circle, The

- Presupposition

- Quechuan and Aymaran Languages

- Reading, Second-Language

- Reciprocals

- Reduplication

- Reflexives and Reflexivity

- Register and Register Variation

- Relevance Theory

- Representation and Processing of Multi-Word Expressions in...

- Salish Languages

- Sapir, Edward

- Saussure, Ferdinand de

- Second Language Acquisition, Anaphora Resolution in

- Semantic Maps

- Semantic Roles

- Semantic-Pragmatic Change

- Semantics, Cognitive

- Sentence Processing in Monolingual and Bilingual Speakers

- Sign Language Linguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociolinguistics, Variationist

- Sociopragmatics

- Sound Change

- South American Indian Languages

- Specific Language Impairment

- Speech, Deceptive

- Speech Perception

- Speech Production

- Speech Synthesis

- Switch-Reference

- Syntactic Change

- Syntactic Knowledge, Children’s Acquisition of

- Tense, Aspect, and Mood

- Text Mining

- Tone Sandhi

- Transcription

- Transitivity and Voice

- Translanguaging

- Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

- Tucanoan Languages

- Tupian Languages

- Usage-Based Linguistics

- Uto-Aztecan Languages

- Valency Theory

- Verbs, Serial

- Vocabulary, Second Language

- Voice and Voice Quality

- Vowel Harmony

- Whitney, William Dwight

- Word Classes

- Word Formation in Japanese

- Word Recognition, Spoken

- Word Recognition, Visual

- Word Stress

- Writing, Second Language

- Writing Systems

- Zapotecan Languages

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Linguistic Theory

DrAfter123/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is the linguistic theory that the semantic structure of a language shapes or limits the ways in which a speaker forms conceptions of the world. It came about in 1929. The theory is named after the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir (1884–1939) and his student Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941). It is also known as the theory of linguistic relativity, linguistic relativism, linguistic determinism, Whorfian hypothesis , and Whorfianism .

History of the Theory

The idea that a person's native language determines how he or she thinks was popular among behaviorists of the 1930s and on until cognitive psychology theories came about, beginning in the 1950s and increasing in influence in the 1960s. (Behaviorism taught that behavior is a result of external conditioning and doesn't take feelings, emotions, and thoughts into account as affecting behavior. Cognitive psychology studies mental processes such as creative thinking, problem-solving, and attention.)

Author Lera Boroditsky gave some background on ideas about the connections between languages and thought:

"The question of whether languages shape the way we think goes back centuries; Charlemagne proclaimed that 'to have a second language is to have a second soul.' But the idea went out of favor with scientists when Noam Chomsky 's theories of language gained popularity in the 1960s and '70s. Dr. Chomsky proposed that there is a universal grammar for all human languages—essentially, that languages don't really differ from one another in significant ways...." ("Lost in Translation." "The Wall Street Journal," July 30, 2010)

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was taught in courses through the early 1970s and had become widely accepted as truth, but then it fell out of favor. By the 1990s, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was left for dead, author Steven Pinker wrote. "The cognitive revolution in psychology, which made the study of pure thought possible, and a number of studies showing meager effects of language on concepts, appeared to kill the concept in the 1990s... But recently it has been resurrected, and 'neo-Whorfianism' is now an active research topic in psycholinguistics ." ("The Stuff of Thought. "Viking, 2007)

Neo-Whorfianism is essentially a weaker version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis and says that language influences a speaker's view of the world but does not inescapably determine it.

The Theory's Flaws

One big problem with the original Sapir-Whorf hypothesis stems from the idea that if a person's language has no word for a particular concept, then that person would not be able to understand that concept, which is untrue. Language doesn't necessarily control humans' ability to reason or have an emotional response to something or some idea. For example, take the German word sturmfrei , which essentially is the feeling when you have the whole house to yourself because your parents or roommates are away. Just because English doesn't have a single word for the idea doesn't mean that Americans can't understand the concept.

There's also the "chicken and egg" problem with the theory. "Languages, of course, are human creations, tools we invent and hone to suit our needs," Boroditsky continued. "Simply showing that speakers of different languages think differently doesn't tell us whether it's language that shapes thought or the other way around."

- Definition and Discussion of Chomskyan Linguistics

- Cognitive Grammar

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Universal Grammar (UG)

- Transformational Grammar (TG) Definition and Examples

- Linguistic Performance

- What Is a Natural Language?

- Linguistic Competence: Definition and Examples

- The Theory of Poverty of the Stimulus in Language Development

- 24 Words Worth Borrowing From Other Languages

- What Is Linguistic Functionalism?

- The Definition and Usage of Optimality Theory

- Definition and Examples of Case Grammar

- An Introduction to Semantics

- What Is Relevance Theory in Terms of Communication?

- Construction Grammar

Group 6: Potpourri

Linguistic relativity: the whorf hypothesis.

In the 1920s, Benjamin Whorf was a graduate student studying with linguist Edward Sapir at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Sapir, considered the father of American linguistic anthropology, was responsible for documenting and recording the languages and cultures of many Native American tribes, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. This was due primarily to the deliberate efforts of the United States government to force Native Americans to assimilate into the Euro-American culture.

Sapir and his predecessors were well aware of the close relationship between culture and language because each culture is reflected in and influences its language. Anthropologists need to learn the language of the culture they are studying in order to understand the world view of its speakers. Whorf believed that the reverse is also true, that a language affects culture as well, by actually influencing how its speakers think. His hypothesis proposes that the words and the structures of a language influence how its speakers think about the world, how they behave, and ultimately the culture itself. Simply stated, Whorf believed that human beings see the world the way they do because the specific languages they speak influence them to do so. He developed this idea through both his work with Sapir and his work as a chemical engineer for the Hartford Insurance Company investigating the causes of fires.

One of his cases while working for the insurance company was a fire at a business where there were a number of gasoline drums. Those that contained gasoline were surrounded by signs warning employees to be cautious around them and to avoid smoking near them. The workers were always careful around those drums. On the other hand, empty gasoline drums were stored in another area, but employees were more careless there. Someone tossed a cigarette or lighted match into one of the “empty” drums, it went up in flames, and started a fire that burned the business to the ground. Whorf theorized that the meaning of the word empty implied to the worker that “nothing” was there to be cautious about so the worker behaved accordingly. Unfortunately, an “empty” gasoline drum may still contain fumes, which are more flammable than the liquid itself.

Whorf’s studies at Yale involved working with Native American languages, including Hopi. The Hopi language is quite different from English, in many ways. For example, let’s look at how the Hopi language deals with time. Western languages (and cultures) view time as a flowing river in which we are being carried continuously away from a past, through the present, and into a future. Our verb systems reflect that concept with specific tenses for past, present, and future. We think of this concept of time as universal, that all humans see it the same way. A Hopi speaker has very different ideas and the structure of their language both reflects and shapes the way they think about time. The Hopi language has no present, past, or future tense. Instead, it divides the world into what Whorf called the manifested and unmanifest domains. The manifested domain deals with the physical universe, including the present, the immediate past and future; the verb system uses the same basic structure for all of them. The unmanifest domain involves the remote past and the future, as well as the world of desires, thought, and life forces. The set of verb forms dealing with this domain are consistent for all of these areas, and are different from the manifested ones. Also, there are no words for hours, minutes, or days of the week.

Native Hopi speakers often had great difficulty adapting to life in the English speaking world when it came to being “on time” for work or other events. It is simply not how they had been conditioned to behave with respect to time in their Hopi world, which followed the phases of the moon and the movements of the sun. In a book about the Abenaki who lived in Vermont in the mid-1800s, Trudy Ann Parker described their concept of time, which very much resembled that of the Hopi and many of the other Native American tribes. “They called one full day a sleep, and a year was called a winter. Each month was referred to as a moon and always began with a new moon. An Indian day wasn’t divided into minutes or hours. It had four time periods—sunrise, noon, sunset, and midnight. Each season was determined by the budding or leafing of plants, the spawning of fish or the rutting time for animals. Most Indians thought the white race had been running around like scared rabbits ever since the invention of the clock.” [1]

The lexicon, or vocabulary, of a language is an inventory of the items a culture talks about and has categorized in order to make sense of the world and deal with it effectively. For example, modern life is dictated for many by the need to travel by some kind of vehicle—cars, trucks, SUVs, trains, buses, etc. We therefore have thousands of words to talk about them, including types of vehicles, models, brands, or parts.

The most important aspects of each culture are similarly reflected in the lexicon of its language. Among the societies living in the islands of Oceania in the Pacific, fish have great economic and cultural importance. This is reflected in the rich vocabulary that describes all aspects of the fish and the environments that islanders depend on for survival. For example, in Palau there are about 1,000 fish species and Palauan fishermen knew, long before biologists existed, details about the anatomy, behavior, growth patterns and habitat of most of them—in many cases far more than modern biologists know even today. Much of fish behavior is related to the tides and the phases of the moon. Throughout Oceania, the names given to certain days of the lunar months reflect the likelihood of successful fishing. For example, in the Caroline Islands, the name for the night before the new moon is otolol , which means “to swarm.” The name indicates that the best fishing days cluster around the new moon. In Hawai`i and Tahiti two sets of days have names containing the particle `ole or `ore ; one occurs in the first quarter of the moon and the other in the third quarter. The same name is given to the prevailing wind during those phases. The words mean “nothing,” because those days were considered bad for fishing as well as planting.

Parts of Whorf’s hypothesis, known as linguistic relativity were controversial from the beginning, and still are among some linguists. Yet Whorf’s ideas now form the basis for an entire sub-field of cultural anthropology: cognitive or psychological anthropology. A number of studies have been done that support Whorf’s ideas. Linguist George Lakoff’s work looks at the pervasive existence of metaphors in everyday speech that can be said to predispose a speaker’s world view and attitudes on a variety of human experiences. [2]

A metaphor is an expression in which one kind of thing is understood and experienced in terms of another entirely unrelated thing; the metaphors in a language can reveal aspects of the culture of its speakers. Take, for example, the concept of an argument. In logic and philosophy, an argument is a discussion involving differing points of view, or a debate. But the conceptual metaphor in American culture can be stated as ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in many expressions of the everyday language of American speakers: I won the argument. He shot down every point I made. They attacked every argument we made. Your point is right on target. I had a fight with my boyfriend last night. In other words, we use words appropriate for discussing war when we talk about arguments, which are certainly not real war. But we actually think of arguments as a verbal battle that often involve anger, and even violence, which then structures how we argue.

To illustrate that this concept of argument is not universal, Lakoff suggests imagining a culture where an argument is not something to be won or lost, with no strategies for attacking or defending, but rather as a dance where the dancers’ goal is to perform in an artful, pleasing way. No anger or violence would occur or even be relevant to speakers of this language, because the metaphor for that culture would be ARGUMENT IS DANCE.

[1] Trudy Ann Parker, Aunt Sarah, Woman of the Dawnland (Lancaster, NH, Dawnland Publications 1994), 56.

[2] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), 4-5.

- Linguistic Relativity: The Whorf Hypothesis, in the Language Variation: Sociolinguistics section of Chapter 4, Language. Authored by : Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de Gonzalez. Provided by : The Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC). Located at : https://perspectives.pressbooks.com/chapter/language/#chapter-66-section-3 . Project : Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- image of Hopi dwelling. Authored by : Eric Simon. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/montezuma-castle-national-monument-436735/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of empty barrels. Authored by : Hafis Fox. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/illustrations/barrel-environment-game-oil-2557164/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of earth, sun, moon, and tree, showing day and night. Authored by : Dirk Rabe. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/illustrations/day-and-night-little-planet-694840/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of children fishing. Authored by : Sasin Tipchai. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/children-fishing-teamwork-together-1807511/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved