Malthus on Population

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- pp 4751–4760

- Cite this reference work entry

- Joseph R Burger 3 , 4

249 Accesses

An Essay on the Principle of Population ; Exponential growth ; Malthusian growth

An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Robert Malthus ( 1798 ) is a book widely viewed as having profound impact on the biological and social sciences by recognizing basic biophysical, demographic, and economic principles that can lead to population growth and possible collapse.

Introduction

Be fruitful and multiply. Fill the earth and govern it. Reign over the fish in the sea, the birds in the sky, and all the animals that scurry along the ground. – Genesis 1:28

The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence. – Malthus 1798

An Essay on the Principle of Population by the Reverend, Political Economist, and Demographer, Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834), is perhaps the most important document ever published on population, yet its central thesis continues to be highly controversial between natural and social scientists today....

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barlow, N. (1958). The autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his grand-daughter Nora Barlow . http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1497&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

Bashford, A., & Chaplin, J. E. (2016). The new worlds of thomas robert malthus: Rereading the principle of population princeton . Princeton University Press.

Google Scholar

Boserup, E. (1965). The conditions of agricultural growth: The economics of agrarian change under population pressure . London: Allen & Unwin.

Bricker, D., & Ibbitson, J. (2019). Empty planet: The shock of global population decline . New York: Crown.

Brown, J. H., Hall, C. A. S., & Sibly, R. M. (2018). Equal fitness paradigm explained by a trade-off between generation time and energy production rate. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 2 (2), 262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0430-1 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Burger, J. R. (2018). Modeling humanity’s predicament. Nature Sustainability, 1 , 15–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-017-0010-z .

Article Google Scholar

Burger, J. R. (2019). Fueling fertility is emptying the planet’s resources. Bioscience, 69 (9), 757–758. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz084 .

Burger, J. R., Allen, C. A., Brown, J. H., Burnside, W. R., Davidson, A. D., Fristoe, T. S., Hamilton, M. J., Mercado-Silva, N., Nekola, J. C., Okie, J. G., & Zuo, W. (2012). The macroecology of sustainability. PLoS Biology, 10 , e1001345. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001345 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Burger, J. R., Weinberger, V. P., & Marquet, P. A. (2017). Extra-metabolic energy use and the rise in human hyper-density. Scientific Reports, 7 . https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43869 .

Burger, J. R., Hou, C., & Brown, J. H. (2019a). Toward a metabolic theory of life history. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1907702116 .

Burger, J. R., Brown, J. H., Day, J. W., Jr., Flanagan, T. P., & Roy, E. (2019b). The central role of energy in the urban transition: Challenges for global sustainability. BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality, 4 (5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41247-019-0053-z .

DeLong, J. P., Burger, O., & Hamilton, M. J. (2010). Current demographics suggest future energy supplies will be inadequate to slow human population growth. PLoS One, 5 (10), e13206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013206 .

Diamond, J. M. (2005). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or succeed . New York: Viking.

Ehrlich, P. R. (1968). The population bomb . Rivercity: River City Press.

Franklin, B. (1751). Observations concerning the increase of mankind, peopling of countries, etc. Online version: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0080 . Accessed 24 Sep 2019.

Ginzburg, L. R. (1986). The theory of population dynamics: I. Back to first principles. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 122 (4), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5193(86)80180-1 .

Hodgson. (2016). Book review: The new worlds of Thomas Robert Malthus: Rereading the principle of population by Alison Bashford and Joyce E. Chaplin. Population and Development Review, 42 (4), 717–721.

Jevons, W. S. (1865). The coal question: An inquiry concerning the progress of the nation, and the probable exhaustion of our coal mines . London: Macmillan & Co.

King, C. W. (2015). The rising cost of resources and global indicators of change. American Scientist, 103 (6), 410–417.

Malthus, T.R. (1798). An essay on the principle of population, as it affects the future improvement of society with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other writers. London. Online version: http://www.esp.org/books/malthus/population/malthus.pdf

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behren, W. W. (1972). The limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind . New York: Universe Books.

Moses, M. E., & Brown, J. H. (2003). Allometry of human fertility and energy use. Ecology Letters, 6 , 295–300.

Nekola, J. C., Allen, C. A., Brown, J. H., Burger, J. R., Davidson, A. D., Fristoe, T. S., Hamilton, M. J., Hammond, S. T., Kodrik-Brown, A., Mercado-Silva, N., & Okie, J. G. (2013). The Malthusian-Darwinian dynamic and the trajectory of civilization. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 28 (3), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.12.001 .

Sabin, P. (2013). The bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon, and our gamble over Earth’s future . New haven; London: Yale University Press.

Schramski, J. R., Woodson, C. B., Steck, G., Munn, D., & Brown, J. H. (2019). Declining country-level food self-sufficiency suggests future food insecurities. Biophysical Economics and Resource Quality, 4 (12). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41247-019-0060-0 .

Shermer, M. (2016). Doomsday catch: Why Malthus makes for bad science policy. Scientific American, 314 (5), 72. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0516-72 .

Simon, J. L. (1980). Resources, population, environment: An oversupply of false bad news. Science, 208 , 1431–1437.

Simon, J. L. (1981). The ultimate resource . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Strumsky, D., Lobo, J., & Tainter, J. A. (2010). Complexity and the productivity of innovation. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 27 , 496–509.

Tainter, J. (2011). Energy, complexity, and sustainability: A historical perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1 (1), 89e95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2010.12.001 .

Turchin, P. (2003). Complex population dynamics: A theoretical/empirical synthesis . Peter Turchin. Monographs in Population Biology 35, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 536.

Van Valen, L. (1973). A new evolutionary law. Evolutionary Theory, 1 , 1–30.

Wallace, A. R. (1905). My life, a record of events and opinions , 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall.

Weinberger, V. P., Quiñinao, C., & Marquet, P. A. (2017). Innovation and the growth of human population. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, B 372 , 20160415. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0415 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Duke University Population Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA

Joseph R Burger

Institute of the Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joseph R Burger .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Todd K Shackelford

Viviana A Weekes-Shackelford

Section Editor information

Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Farid Pazhoohi

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Burger, J.R. (2021). Malthus on Population. In: Shackelford, T.K., Weekes-Shackelford, V.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1267

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_1267

Published : 22 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19649-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19650-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

An Essay on the Principle of Population by T. R. Malthus

Read now or download (free!)

| Choose how to read this book | Url | Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.html.images | 352 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.epub3.images | 168 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.epub.noimages | 173 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.kf8.images | 365 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.kindle.images | 354 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4239.txt.utf-8 | 336 kB | |||||

| https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4239/pg4239-h.zip | 166 kB | |||||

| There may be related to this item. | ||||||

Similar Books

About this ebook.

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Title | An Essay on the Principle of Population |

| Credits | Produced by Charles Aldarondo. HTML version by Al Haines. |

| Language | English |

| LoC Class | |

| Subject | |

| Category | Text |

| EBook-No. | 4239 |

| Release Date | Jul 1, 2003 |

| Most Recently Updated | Dec 27, 2020 |

| Copyright Status | Public domain in the USA. |

| Downloads | 243 downloads in the last 30 days. |

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

An Essay on the Principle of Population [1798, 1st ed.]

- Thomas Robert Malthus (author)

This is the first edition of Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population. In this work Malthus argues that there is a disparity between the rate of growth of population (which increases geometrically) and the rate of growth of agriculture (which increases only arithmetically). He then explores how populations have historically been kept in check.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- ePub ePub standard file for your iPad or any e-reader compatible with that format

- Kindle This is an E-book formatted for Amazon Kindle devices.

An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers (London: J. Johnson 1798). 1st edition.

The text is in the public domain.

- Economic theory. Demography

Related Collections:

- Malthus: For and Against

Related People

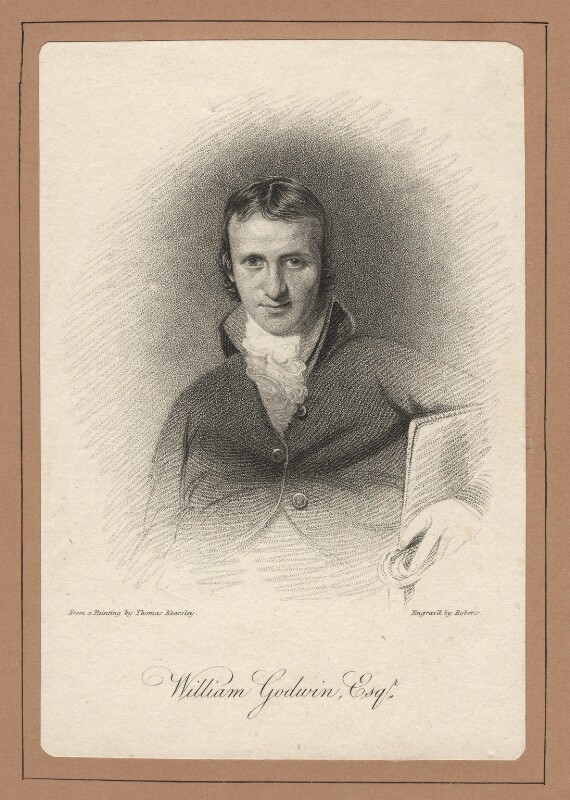

William Godwin (1757-1836) was an English radical political philosopher and novelist. He wrote an important critique of Malthus' theory on population.

David Ricardo followed in the footsteps of Adam Smith. Known for the concept of comparative advantage, he was able to demonstrate the weaknesses of Malthus' theory of population.

With Malthus, Say was also a member of the second phase of the classical political economists. The classical school developed free market economics into a consistent, scientific body of knowledge which quickly became the economic orthodoxy in the first half of the 19th century. Its members were very influential in reforming British government policy especially in the areas of free trade and economic deregulation.

Another member of the second wave of classical economists.

Critical Responses

William Godwin

A lengthy and belated reply to Malthus by the radical individualist Godwin. Whereas Malthus took a pessimistic view of the pressures of population growth, Godwin was more optimistic about the capacity of people to limit the growth of their families.

Connected Readings

Econlib Article

Morgan Rose

Thomas Robert Malthus is arguably the most maligned economist in history. For over two hundred years, since the first publication of his book An Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus’ work has been misunderstood and misrepresented, and severe, alarming predictions have been attached to his…

Malthus had no objection to the idea that wealth derived from manufacturing production could, subject to certain hindrances, be exchanged to increase the amount of food available. He seems only to have misjudged the degree to which those hindrances would be reduced over time. He did not recognize…

What to read next.

Ross Emmett

While many liberty-loving economists are happy to correct the criticisms of Smith, many are equally happy to criticize Malthus for the Malthusian trap, not realizing that the usual portrayal of Malthus is equally false. Malthus shares far more with Smith than most expect. He is, in many ways, as…

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Image & Use Policy

- Translations

UC MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Understanding Evolution

Your one-stop source for information on evolution

The History of Evolutionary Thought

The ecology of human populations: thomas malthus.

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) has a hallowed place in the history of biology, despite the fact that he and his contemporaries thought of him not as a biologist but as a political economist. Malthus grew up during a time of revolutions and new philosophies about human nature. He chose a conservative path, taking holy orders in 1797, and began to write essays attacking the notion that humans and society could be improved without limits.

Population growth vs. the food supply

Malthus’ most famous work, which he published in 1798, was An Essay on the Principle of Population as it affects the Future Improvement of Society . In it, Malthus raised doubts about whether a nation could ever reach a point where laws would no longer be required, and in which everyone lived prosperously and harmoniously. There was, he argued, a built-in agony to human existence, in that the growth of a population will always outrun its ability to feed itself. If every couple raised four children, the population could easily double in twenty-five years, and from then on, it would keep doubling. It would rise not arithmetically—by factors of three, four, five, and so on—but geometrically—by factors of four, eight, and sixteen.

If a country’s population did explode this way, Malthus warned that there was no hope that the world’s food supply could keep up. Clearing new land for farming or improving the yields of crops might produce a bigger harvest, but it could only increase arithmetically, not geometrically. Unchecked population growth inevitably brought famine and misery. The only reason that humanity wasn’t already in perpetual famine was because its growth was continually checked by forces such as plagues, infanticide, and simply putting off marriage until middle age. Malthus argued that population growth doomed any efforts to improve the lot of the poor. Extra money would allow the poor to have more children, only hastening the nation’s appointment with famine.

A new view of humans

Malthus made his groundbreaking economic arguments by treating human beings in a groundbreaking way. Rather than focusing on the individual, he looked at humans as groups of individuals, all of whom were subject to the same basic laws of behavior. He used the same principles that an ecologist would use studying a population of animals or plants. And indeed, Malthus pointed out that the same forces of fertility and starvation that shaped the human race were also at work on animals and plants. If flies went unchecked in their maggot-making, the world would soon be knee-deep in them. Most flies (and most members of any species you choose) must die without having any offspring. And thus when Darwin adapted Malthus’ ideas to his theory of evolution, it was clear to him that humans must evolve like any other animal.

Old Earth, Ancient Life: Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Subscribe to our newsletter

- Teaching resource database

- Correcting misconceptions

- Conceptual framework and NGSS alignment

- Image and use policy

- Evo in the News

- The Tree Room

- Browse learning resources

An Essay on the Principle of Population

50 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-2

Chapters 3-5

Chapters 6-9

Chapters 10-15

Chapters 16-19

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus was first published anonymously in 1798. Its core argument, that human population will inevitably outgrow its capacity to produce food, widely influenced the field of early 19th century economics and social science. Immediately after its first printing, Malthus’s essay garnered significant attention from his contemporaries, and he soon felt the need to reveal his identity. Although it was highly controversial, An Essay on the Principle of Population nevertheless left its impression on foundational 19th century theorists, such as naturalist Charles Darwin and economists Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx. Modern economists have largely dismissed the Malthusian perspective . Principally, they argue Malthus underappreciated the exponential growth brought about by the advent of the Industrial Revolution; by the discovery of new energy sources, such as coal and electricity; and later by further technological innovations. These modern criticisms are easily defended with historical retrospective.

Malthus’s essay has been revised several times since its publication. This summary focuses on the contents of the first edition. In 1806, Malthus revamped his work into four books to further discuss points of contention in the first edition and address many of the criticisms it received. Three more editions followed (published in 1807, 1817, and 1826 respectively), each modifying or clarifying points made in the second version.

Although Malthus’s basic stance on the unsustainable growth of population to food production remains the same throughout all versions, the most dramatic change in format and content is found between the first and second editions. The first edition is notable for its long and detailed critique of the works of William Godwin, Marquis de Condorcet, and Richard Price on the perfectibility of humankind. Its lack of “hard data” and its unpracticed opinions on sex and reproduction were heavily criticized by his contemporaries. The 1806 publication, written at a later point in Malthus’s life, attempts to address these issues by focusing less on critiquing the works of other theorists and offering better data on the fluctuation of population growth throughout various European countries and colonies (Malthus, Thomas Robert. An Essay on the Principle of Population: the 1803 edition . Yale University Press. 2018).

An Essay on the Principle of Population begins with a preface and is subsequently separated into eleven chapters. The preface reveals that a conversation with a friend on the future improvement of society was what sparked Malthus’s inspiration for this work. Chapter 1 further credits the works of David Hume, Alfred Russel, Adam Smith, and many others for inspiring his own writing. He postulates that population grows exponentially, whereas food production only increases in a linear fashion. This disparity in power will inevitably lead to overpopulation and an inadequate amount of food for subsistence.

Chapter 2 further details the above premise. Malthus imagines a world of abundance. In such a society of ease and leisure, no one would be anxious about providing for their families, which incentivizes them to marry early, causing birth rates to explode. When there are too many people and too little an increase in food to support them, the lower classes will be plunged into a state of misery. Thus, Malthus concludes that population growth only happens when there is an increase in subsistence, and misery and vice keep the world from overpopulation.

In chapters 3, 4, and 5, Malthus applies his theory to different stages of society. He argues that “savage” and shepherding societies never grow as fast as their “civilized” counterparts because various miseries keep their numbers in check. Among “savage” societies, a lack of food and a general disrespect of personal liberties prevent their numbers from increasing rapidly. Shepherding communities, meanwhile, often wage war over territories and suffer a high mortality rate. Civilized societies grew rapidly after adopting the practice of tilling, but due to exhausting most fertile land, their numbers no longer increase at the same rate as before.

The following two chapters are notable because they are the only ones that contain hard data. Malthus cites philosopher Richard Price for his analysis of population in America and references demographer Johann Peter Süssmilch for his work on Prussia. Malthus uses both these examples to prove that population fluctuates in accordance with the quantity of food produced. Chapters 8 and 9 are dedicated to critiquing mathematician Marquis de Condorcet’s work while chapters 10 to 15 do the same for political philosopher William Godwin. Malthus rejects the idea of mankind as infinitely perfectible and dismisses charity as a method to relieve poverty.

Chapters 16 and 17 propose the increase of food production as the only solution to reduce extreme poverty and misery among the lower class. Malthus maintains that donating funds is but a temporary relief to aid the most unfortunate; only a permanent increase in agricultural yield can grow the lower class’s purchasing power. Nevertheless, the final two chapters remind readers that misery and happiness must coexist. The law of nature, the way of living intended by God and demonstrated by Malthus’s population theory, requires both wealth and poverty to function.

Featured Collections

Business & Economics

View Collection

European History

Philosophy, Logic, & Ethics

Poverty & Homelessness

Science & Nature

Malthusian Theory of Population: Explained with its Criticism

The most well-known theory of population is the Malthusian theory. Thomas Robert Malthus wrote his essay on “Principle of Population” in 1798 and modified some of his conclusions in the next edition in 1803.

The rapidly increasing population of England encouraged by a misguided Poor Law distressed him very deeply.

He feared that England was heading for a disaster, and he considered it his solemn duty to warn his country-men of impending disaster. He deplored “the strange contrast between over-care in breeding animals and carelessness in breeding men.”

His theory is very simple. To use his own words: “By nature human food increases in a slow arithmetical ratio; man himself increases in a quick geometrical ratio unless want and vice stop him.The increase in numbers is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence Population invariably increases when the means of subsistence increase, unless prevented by powerful and obvious checks.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Malthus based his reasoning on the biological fact that every living organism tends to multiply to an unimaginable extent. A single pair of thrushes would multiply into 19,500,000 after the life of the first pair and 20 years later to 1,200,000,000,000,000,000,000 and if they stood shoulder to shoulder about one m every 150,000 would be able to find a perching space on the whole surface of the globe! According to Huxley’s estimate, the descendants of a single greenfly, if all survived and multiplied, would, at the end of one summer, weigh down the population of China! Human beings are supposed to double every 25 years and a coup/e can increase to the size of the present population in 1,750 years!

Such is the prolific nature of every specie. The power of procreation is inherent and insistent, and must find expression. Cantillon says, “Men multiply like mice in a barn.” Production of food, on the other hand, is subject to the law of diminishing returns. On the basis of these two premises, Malthus concluded that population tended to outstrip the food supply. If preventive checks, like avoidance of marriage, later marriage or less children per marriage, are not exercised, then positive checks, like war, famine and disease, will operate.

The theory propounded by Malthus can be summed up in the following propositions:

(1) Food is necessary to the life of man and, therefore, exercises a strong check on population. In other words, population is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence (i.e., food).

(2) Population increases faster than food production. Whereas population increases in geometric progression, food production increases in arithmetic progression.

(3) Population always increases when the means of subsistence increase, unless prevented by some powerful checks.

(4) There are two types of checks which can keep population on a level with the means of subsistence. They are the preventive and a positive check.

The first proposition is that the population of a country is limited by the means of subsistence. In other words, the size of population is determined by the availability of food. The greater the food production, the greater the size of the population which can be sustained. The check of deaths caused by want of food and poverty would limit the maximum possible population.

The second proposition states that the growth of population will out-run the increase in food production. Malthus thought that man’s sexual urge to bear offspring knows no bounds. He seemed to think that there was no limit to the fertility of man. But the power of land to produce food is limited. Malthus thought that the law of diminishing returns operated in the field of agriculture and that the operation of this law prevented food production from increasing in proportion to labour and capital invested in land.

In fact, Malthus observed that population would tend to increase at a geometric rate (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, etc.), but food supply would tend to increase at an arithmetic rate (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12). Thus, at the end of two hundred years “population would be to the means of subsistence as 259 to 9; in three centuries as 4,096 to 13, and in two thousand years the difference would be incalculable.” Therefore, Malthus asserted that population would ultimately outstrip food supply.

According to the third proposition, as the food supply in a country increases, the people will produce more children and would have larger families. This would increase the demand for food and food per person will again diminish. Therefore, according to Malthus, the standard of living of the people cannot rise permanently. As regards the fourth proposition, Malthus pointed out that there were two possible checks which could limit’ the growth of population: (a) Preventive checks, and (b) Positive checks.

Preventive Checks:

Preventive checks exercise their influence on the growth of population by bringing down the birth rate. Preventive checks are those checks which are applied by man. Preventive checks arise from man’s fore-sight which enables him to see distant consequences He sees the distress which frequently visits those who have large families.

He thinks that with a large number of children, the standard of living of the family is bound to be lowered. He may think that if he has to support a large family, he will have to subject himself to greater hardships and more strenuous labour than that in his present state. He may not be able to give proper education to his children if they are more in number.

Further, he may not like exposing his children to poverty or charity by his inability to provide for them. These considerations may force man to limit his family. Late marriage and self-restraint during married life are the examples of preventive checks applied by man to limit the family.

Positive Checks:

Positive checks exercise their influence on the growth of population by increasing the death rate. They are applied by nature. The positive checks to population are various and include every cause, whether arising from vice or misery, which in any degree contributes to shorten the natural duration of human life.

The unwholesome occupations, hard labour, exposure to the seasons, extreme poverty, bad nursing of children, common diseases, wars, plagues and famines ire some of the examples of positive checks. They all shorten human life and increase the death rate.

Malthus recommended the use of preventive checks if mankind was to escape from the impending misery. If preventive checks were not effectively used, positive checks like diseases, wars and famines would come into operation. As a result, the population would be reduced to the level which can be sustained by the available quantity of food supply.

Criticism of Malthusian Theory:

The Malthusian theory of population has been a subject of keen controversy.

The following are some of the grounds on which it has been criticized:

(i) It is pointed out that Malthus’s pessimistic conclusions have not been borne out by the history of Western European countries. Gloomy forecast made by Malthus about the economic conditions of future generations of mankind has been falsified in the Western world. Population has not increased as rapidly as predicted by Malthus; on the other hand, production has increased tremendously because of the rapid advances in technology. As a result, living standards of the people have risen instead of falling as was predicted by Malthus.

(ii) Malthus asserted that food production would not keep pace with population growth owing to the operation of the law of diminishing returns in agriculture. But by making rapid advances in technology and accumulating capital in larger quantity, advanced countries have been able to postpone the stage of diminishing returns. By making use of fertilizers, pesticide better seeds, tractors and other agricultural machinery, they have been able to increase their production greatly.

In fact, in most of the advanced countries the rate of increase of food production has been much greater than the rate of population growth. Even in India now, thanks to the Green Revolution, the increase in food production is greater than the increase in population. Thus, inventions and improvements in the methods of production have belied the gloomy forecast of Malthus by holding the law of diminishing returns in check almost indefinitely.

(iii) Malthus compared the population growth with the increase in food production alone. Malthus held that because land was available in limited quantity, food production could not rise faster than population. But he should have considered all types of production in considering the question of optimum size of population. England did feel the shortage of land and food.

If England had been forced to support her population entirely from her own soil, there can be little doubt that England would have experienced a series of famines by which her growth of population would have been checked.But England did not experience such a disaster. It is because England industrialized itself by developing her natural resources other than land like coal and iron, and accumulating man-made capital equipment like factories, tools, machinery, mines, ships and railways, this enabled her to produce plenty of industrial and manufacturing goods which she then exported in exchange for food-stuffs from foreign countries.

There is no food problem in Great Britain. Therefore, Malthus made a mistake in taking agricultural land and food production alone into account when discussing the population question. As already said, he should have rather considered all types of production.

(iv) Malthus held that the increase in the means of subsistence or food supplies would cause population to grow rapidly so that ultimately means of subsistence or food supply would be in level with population, and everyone would get only bare minimum subsistence. In other words, according to Malthus, living standards of the people cannot rise in the long run above the level of minimum subsistence. But, as already pointed out, living standards of the people in the Western world have risen greatly and stand much above the minimum subsistence level.

There is no evidence of birth-rate rising with the increases in the standard of living. Instead, there is evidence that birth-rates fall as the economy grows. In Western countries, attitude towards children changed as they developed economically. Parents began to feel that it was their duty to do as much as they could for each child.

Therefore, they preferred not to have more children than they could attend to properly. People now began to care more for maintaining a higher standard of living rather than for bearing more children. The wide use of contraceptives in the Western world brought down the birth rates. This change in the attitude towards children and the wide use of contraceptives in the Western world has falsified Malthusian doctrine.

(v) Malthus gave no proof of his assertion that population increased exactly in geometric progression and food production increased exactly in arithmetic progression. It has been rightly pointed out that population and food supply do not change in accordance with these mathematical series. Growth of population and food supply cannot be expected to show the precision or accuracy of such series.

However, Malthus, in later editions of his book, did not insist on these mathematical terms and only held that there was an inherent tendency in population to outrun the means of subsistence. We have seen above that even this is far from true.

There is no doubt that the civilized world has kept the population in check. It is, however, to be regretted that population has been increasing at the wrong end. The poor people, who can ill-afford to bring up and educate children, are multiplying, whereas the rich are applying breaks on the increase of the size of their families.

Is Malthusian Theory Valid Today?

We must, however, add that though the gloomy conclusions of Malthus have not turned out to be true due to several factors which have made their appearance only in recent times, yet the essentials of the theory have not been demolished. He said that unless preventive checks were exercised, positive checks would operate. This is true even today. The Malthusian theory fully applies in India.

We are at present in that unenviable position which Malthus feared. We have the highest birth-rate and the highest death-rate in the world. Grinding poverty, ever-recurring epidemics, famine and communal quarrels are the order of the day. We are deficient in food supply.

Our standard of living is incredibly low. Who can say that Malthus was not a true prophet, if not for his country, at any rate for the Asiatic countries like India, Pakistan and China? No wonder that intense family planning drive is on in India at present.

Related Articles:

- The Malthusian Theory of Population (Criticism)

- Malthusian Theory of Population (With Diagram)

- Malthusian Theory of Population (With Criticisms) | Economics

- Malthusian Theory and the Optimum Theory | Population

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Biological factors affecting human fertility

- Contraception

- Sterilization

- The epidemiologic transition

- Infant mortality

- Infanticide

- Mortality among the elderly

- Early human migrations

- Modern mass migrations

- Forced migrations

- Internal migrations

- Population growth

- Population “momentum”

- Age distribution

- Ethnic or racial composition

- Geographical distribution and urbanization

- Population theories in antiquity

- Mercantilism and the idea of progress

- Physiocrats and the origins of demography

- Utopian views

Malthus and his successors

- Marx, Lenin, and their followers

The Darwinian tradition

Theory of the demographic transition.

- The developing countries since 1950

- The industrialized countries since 1950

- Population projections

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Who and What Is a “Population”? Historical Debates, Current Controversies, and Implications for Understanding “Population Health” and Rectifying Health Inequities

- Pressbooks - Introduction to Human Geography - Population

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Plum pomaces as a potential source of dietary fibre: composition and antioxidant properties

- Nature - Scitable - Introduction to Population Demographics

- University of West Florida Pressbooks - Introduction to Environmental Sciences and Sustainability - Population

- NSCC Libraries Pressbooks - Demography and Population

- Biology LibreTexts - Population Demography

- population - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- population - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

In 1798 Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers . This hastily written pamphlet had as its principal object the refutation of the views of the utopians. In Malthus’ view, the perfection of a human society free of coercive restraints was a mirage, because the capacity for the threat of population growth would always be present. In this, Malthus echoed the much earlier arguments of Robert Wallace in his Various Prospects of Mankind, Nature, and Providence (1761), which posited that the perfection of society carried with it the seeds of its own destruction, in the stimulation of population growth such that “the earth would at last be overstocked, and become unable to support its numerous inhabitants.”

Not many copies of Malthus’ essay, his first, were published, but it nonetheless became the subject of discussion and attack. The essay was cryptic and poorly supported by empirical evidence . Malthus’ arguments were easy to misrepresent, and his critics did so routinely.

The criticism had the salutary effect of stimulating Malthus to pursue the data and other evidence lacking in his first essay. He collected information on one country that had plentiful land (the United States) and estimated that its population was doubling in less than 25 years. He attributed the far lower rates of European population growth to “preventive checks,” giving special emphasis to the characteristic late marriage pattern of western Europe, which he called “moral restraint.” The other preventive checks to which he alluded were birth control , abortion, adultery, and homosexuality, all of which as an Anglican minister he considered immoral.

In one sense, Malthus reversed the arguments of the mercantilists that the number of people determined the nation’s resources, adopting the contrary argument of the Physiocrats that the resource base determined the numbers of people. From this he derived an entire theory of society and human history, leading inevitably to a set of provocative prescriptions for public policy. Those societies that ignored the imperative for moral restraint—delayed marriage and celibacy for adults until they were economically able to support their children—would suffer the deplorable “positive checks” of war, famine , and epidemic , the avoidance of which should be every society’s goal. From this humane concern about the sufferings from positive checks arose Malthus’ admonition that poor laws (i.e., legal measures that provided relief to the poor) and charity must not cause their beneficiaries to relax their moral restraint or increase their fertility , lest such humanitarian gestures become perversely counterproductive.

Having stated his position, Malthus was denounced as a reactionary, although he favoured free medical assistance for the poor, universal education at a time that this was a radical idea, and democratic institutions at a time of elitist alarums about the French Revolution . Malthus was accused of blasphemy by the conventionally religious. The strongest denunciations of all came from Marx and his followers (see below). Meanwhile, the ideas of Malthus had important effects upon public policy (such as reforms in the English Poor Laws) and upon the ideas of the classical and neoclassical economists, demographers, and evolutionary biologists, led by Charles Darwin . Moreover, the evidence and analyses produced by Malthus dominated scientific discussion of population during his lifetime; indeed, he was the invited author of the article “Population” for the supplement (1824) to the fourth, fifth, and sixth editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica . Though many of Malthus’ gloomy predictions have proved to be misdirected, that article introduced analytical methods that clearly anticipated demographic techniques developed more than 100 years later.

The latter-day followers of Malthusian analysis deviated significantly from the prescriptions offered by Malthus. While these “neo-Malthusians” accepted Malthus’ core propositions regarding the links between unrestrained fertility and poverty, they rejected his advocacy of delayed marriage and his opposition to birth control. Moreover, leading neo-Malthusians such as Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant could hardly be described as reactionary defenders of the established church and social order. To the contrary, they were political and religious radicals who saw the extension of knowledge of birth control to the lower classes as an important instrument favouring social equality. Their efforts were opposed by the full force of the establishment, and both spent considerable time on trial and in jail for their efforts to publish materials—condemned as obscene—about contraception.

Marx , Lenin, and their followers

While both Karl Marx and Malthus accepted many of the views of the classical economists, Marx was harshly and implacably critical of Malthus and his ideas. The vehemence of the assault was remarkable. Marx reviled Malthus as a “miserable parson” guilty of spreading a “vile and infamous doctrine, this repulsive blasphemy against man and nature.” For Marx, only under capitalism does Malthus’ dilemma of resource limits arise. Though differing in many respects from the utopians who had provoked Malthus’ rejoinder, Marx shared with them the view that any number of people could be supported by a properly organized society. Under the socialism favoured by Marx, the surplus product of labour, previously appropriated by the capitalists, would be returned to its rightful owners, the workers, thereby eliminating the cause of poverty. Thus Malthus and Marx shared a strong concern about the plight of the poor, but they differed sharply as to how it should be improved. For Malthus the solution was individual responsibility as to marriage and childbearing; for Marx the solution was a revolutionary assault upon the organization of society, leading to a collective structure called socialism .

The strident nature of Marx’s attack upon Malthus’ ideas may have arisen from his realization that they constituted a potentially fatal critique of his own analysis. “If [Malthus’] theory of population is correct,” Marx wrote in 1875 in his Critique of the Gotha Programme (published by Engels in 1891), “then I can not abolish this [iron law of wages] even if I abolish wage-labor a hundred times, because this law is not only paramount over the system of wage-labor but also over every social system.”

The anti-Malthusian views of Marx were continued and extended by Marxians who followed him. For example, although in 1920 Lenin legalized abortion in the revolutionary Soviet Union as the right of every woman “to control her own body,” he opposed the practice of contraception or abortion for purposes of regulating population growth. Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin , adopted a pronatalist argument verging on the mercantilist, in which population growth was seen as a stimulant to economic progress. As the threat of war intensified in Europe in the 1930s, Stalin promulgated coercive measures to increase Soviet population growth, including the banning of abortion despite its status as a woman’s basic right. Although contraception is now accepted and practiced widely in most Marxist-Leninist states, some traditional ideologists continue to characterize its encouragement in Third-World countries as shabby Malthusianism.

Charles Darwin, whose scientific insights revolutionized 19th-century biology, acknowledged an important intellectual debt to Malthus in the development of his theory of natural selection . Darwin himself was not much involved in debates about human populations, but many who followed in his name as “ social Darwinists ” and “ eugenicists ” expressed a passionate if narrowly defined interest in the subject.

In Darwinian theory the engine of evolution is differential reproduction of different genetic stocks. The concern of many social Darwinists and eugenicists was that fertility among those they considered the superior human stocks was far lower than among the poorer—and, in their view, biologically inferior—groups, resulting in a gradual but inexorable decline in the quality of the overall population. While some attributed this lower fertility to deliberate efforts of people who needed to be informed of the dysgenic effects of their behaviour, others saw the fertility decline itself as evidence of biological deterioration of the superior stocks. Such simplistic biological explanations attracted attention to the socioeconomic and cultural factors that might explain the phenomenon and contributed to the development of the theory of the demographic transition.

The classic explanation of European fertility declines arose in the period following World War I and came to be known as demographic transition theory . (Formally, transition theory is a historical generalization and not truly a scientific theory offering predictive and testable hypotheses.) The theory arose in part as a reaction to crude biological explanations of fertility declines; it rationalized them in solely socioeconomic terms, as consequences of widespread desire for fewer children caused by industrialization , urbanization , increased literacy, and declining infant mortality .

The factory system and urbanization led to a diminution in the role of the family in industrial production and a reduction of the economic value of children. Meanwhile, the costs of raising children rose, especially in urban settings, and universal primary education postponed their entry into the work force . Finally, the lessening of infant mortality reduced the number of births needed to achieve a given family size. In some versions of transition theory, a fertility decline is triggered when one or more of these socioeconomic factors reach certain threshold values.

Until the 1970s transition theory was widely accepted as an explanation of European fertility declines, although conclusions based on it had never been tested empirically. More recently careful research on the European historical experience has forced reappraisal and refinement of demographic transition theory. In particular, distinctions based upon cultural attributes such as language and religion, coupled with the spread of ideas such as those of the nuclear family and the social acceptability of deliberate fertility control, appear to have played more important roles than were recognized by transition theorists.

Trends in world population

Before considering modern population trends separately for developing and industrialized countries, it is useful to present an overview of older trends. It is generally agreed that only 5,000,000–10,000,000 humans (i.e., one one-thousandth of the present world population) were supportable before the agricultural revolution of about 10,000 years ago. By the beginning of the Christian era, 8,000 years later, the human population approximated 300,000,000, and there was apparently little increase in the ensuing millennium up to the year 1000 ce . Subsequent population growth was slow and fitful, especially given the plague epidemics and other catastrophes of the Middle Ages. By 1750, conventionally the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, world population may have been as high as 800,000,000. This means that in the 750 years from 1000 to 1750, the annual population growth rate averaged only about one-tenth of 1 percent.

The reasons for such slow growth are well known. In the absence of what is now considered basic knowledge of sanitation and health (the role of bacteria in disease, for example, was unknown until the 19th century), mortality rates were very high, especially for infants and children. Only about half of newborn babies survived to the age of five years. Fertility was also very high, as it had to be to sustain the existence of any population under such conditions of mortality. Modest population growth might occur for a time in these circumstances, but recurring famines, epidemics, and wars kept long-term growth close to zero.

From 1750 onward population growth accelerated. In some measure this was a consequence of rising standards of living, coupled with improved transport and communication, which mitigated the effects of localized crop failures that previously would have resulted in catastrophic mortality. Occasional famines did occur, however, and it was not until the 19th century that a sustained decline in mortality took place, stimulated by the improving economic conditions of the Industrial Revolution and the growing understanding of the need for sanitation and public health measures.

The world population, which did not reach its first 1,000,000,000 until about 1800, added another 1,000,000,000 persons by 1930. (To anticipate further discussion below, the third was added by 1960, the fourth by 1974, and the fifth before 1990.) The most rapid growth in the 19th century occurred in Europe and North America , which experienced gradual but eventually dramatic declines in mortality . Meanwhile, mortality and fertility remained high in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Beginning in the 1930s and accelerating rapidly after World War II , mortality went into decline in much of Asia and Latin America , giving rise to a new spurt of population growth that reached rates far higher than any previously experienced in Europe. The rapidity of this growth, which some described as the “population explosion,” was due to the sharpness in the falls in mortality that in turn were the result of improvements in public health, sanitation, and nutrition that were mostly imported from the developed countries. The external origins and the speed of the declines in mortality meant that there was little chance that they would be accompanied by the onset of a decline in fertility. In addition, the marriage patterns of Asia and Latin America were (and continue to be) quite different from those in Europe; marriage in Asia and Latin America is early and nearly universal , while that in Europe is usually late and significant percentages of people never marry.

These high growth rates occurred in populations already of very large size, meaning that global population growth became very rapid both in absolute and in relative terms. The peak rate of increase was reached in the early 1960s, when each year the world population grew by about 2 percent, or about 68,000,000 people. Since that time both mortality and fertility rates have decreased, and the annual growth rate has fallen moderately, to about 1.7 percent. But even this lower rate, because it applies to a larger population base, means that the number of people added each year has risen from about 68,000,000 to 80,000,000.

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB Articles

Sep 16 2002

In Defense of Malthus

By morgan rose.

By Morgan Rose, Sep 16 2002

Some Background

For brief biographies of Malthus (1766-1834), see the CEE and other biographical material.

Before delving into what Malthus wrote and how critics misconstrued his views, it is helpful to give an idea of the controversy that surround Malthus’ Essay. The first edition, published in 1798, was a fairly short volume that laid out Malthus’ essential points, discussed below. It inspired an onslaught of criticism and denunciation of the work and the author, who was variously described as foolish, heartless, blasphemous, and any combination of the three.

If you want to get a sense of how extensive Malthus’ expansion of his Essay was, compare the Table of Contents of the first edition with that of the sixth edition.

The uproar inspired Malthus to thoroughly revise his work for the second edition, published in 1803. The two margins on which he expanded the Essay were (1) laying out his arguments more clearly and in more explicit detail and (2) including vast amounts of empirical information in support of his theory of population. His pursuit of data took him on trips through Germany, Russia, and Scandinavia, making him one of the first economists to perform extensive field-work to gather cross-country data. Other than the inclusion of additional arguments and information that he gradually accumulated, the sixth edition, published in 1826, is largely the same as the second edition. (Except where noted, all of the passages quoted below from the Essay come from the sixth edition.)

Malthus most likely believed that the revisions he made would dispel a large amount of the heat he received after his book’s initial publication. He was wrong. If anything, attacks against him increased in number and rancor. One detractor, whose criticism of Malthus will be examined below, went so far as to write that “I willingly plead guilty to the charge of regarding his doctrines with inexpressible abhorrence,” and “Mr. Malthus’ [creed] is not the religion of the Bible. On the contrary it is in diametrical opposition to it.” 1

Although attackers with that much venom do not appear anymore, the fundamental lack of understanding of Malthus’ work continues to this day, to the point that what is “popularly known” about Malthus is the false picture, not the true one found in the Essay. Recently, a nationally syndicated columnist referred to “the 18th century economist Thomas Malthus, who claimed the world would starve because food production could never keep up with human population growth,” 2 showing how inaccurate characterizations of Malthus’ ideas from almost two hundred years ago have persisted to this day.

What Malthus Actually Wrote

The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics contains an entry on Population that describes the concerns classical and present-day economists have had over population growth, and how those concerns changed over time.

Malthus’ main concerns were the determinants of population growth, the relationship between population and production, and how the bases of that relationship were the rational choices of foresighted individuals. The main tenets of his theory were laid out in Chapter 1, Book 1 of Essay. His starting point was the axiomatic notion that “population is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence,” meaning that there cannot be more people walking around than everyone’s total production, particularly food production, can support.

From there, he described the potential rates of growth for both population and production. Starting with population, he stated in the absence of any impediments, or checks, to population growth, the size of a given population would rise at an ever-increasing rate. To see how this works, imagine a population of 1,000 people whose birth and death rates are such that the population doubles in size with each successive generation. As the generations go by, that population would expand increasingly quickly, from 1,000 to 2,000 to 4,000 to 8,000 and so on.

In paragraph 9, Malthus wrote that “in no state that we have yet known, has the power of population been left to exert itself with perfect freedom,” and so he could not determine how quickly a population with no checks on its advance would grow. As a matter of convenience, he still wanted some sort of benchmark to use in his analysis. For this, he looked toward the fledgling United States, where he believed the checks to population growth were lower than anywhere else and so population growth was highest. In paragraph 11, he notes that according to reports available at the time, “the population [in the northern states of America] has been found to double itself, for above a century and a half successively, in less than twenty-five years.” Because a doubling every twenty-five years was the fastest actual population growth about which Malthus knew, he adopted it as a lower-bound estimate of population growth in the absence of any checks, writing in paragraph 16 that “It may safely be pronounced, therefore, that population, when unchecked, goes on doubling itself every twenty-five years, or increases in a geometrical ratio.”

Readers familiar with the increases in food production and in overall production over the last few centuries are no doubt chafing at Malthus’ assertion that food production can increase no faster than arithmetically. Such readers are asked to be patient, as this subject will be addressed in an upcoming column.

Turning to the potential rate of growth of production of the means of subsistence, specifically food, Malthus this time sought an upper-bound estimate so he could compare the most liberal estimate of food production growth with the most conservative estimate of population growth. He laid out his assumptions about food production growth in paragraphs 21, 24, and 25:

If it be allowed that by the best possible policy, and great encouragements to agriculture, the average produce of [Britain] could be doubled in the first twenty five years, it will be allowing, probably, a greater increase than could with reason be expected.

If this supposition be applied to the whole earth, and if it be allowed that the subsistence for man which the earth affords might be increased every twenty-five years by a quantity equal to what it at present produces, this will be supposing a rate of increase much greater than we can imagine that any possible exertions of mankind could make it.

It may be fairly pronounced, therefore, that, considering the present average state of the earth, the means of subsistence, under circumstances the most favourable to human industry, could not possibly be made to increase faster than in an arithmetical ratio.

Paul A. Samuelson’s textbook Economics (1980, first pub. 1951) includes this poem on page 15 entitled “Song of Malthus: A Ballad on Diminishing Returns”:

To get land’s fruit in quantity Takes jolts of labour ever more, Hence food will grow like one, two, three…. While numbers grow like one, two, four….

Taking these two ratios together, then, and arbitrarily setting the initial level of both population and production at one, then according to paragraph 27, “the human species would increase as the numbers, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and subsistence as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. In two centuries the population would be to the means of subsistence as 256 to 9; in three centuries as 4096 to 13, and in two thousand years the difference would be almost incalculable.”

These geometric and arithmetic ratios are what most people who have heard of Malthus know about his work. Had Malthus stopped here, then it would be hard to dispute the popular misconception about his work—the numbers show population growing so much faster than production that starvation on a massive scale seems to be the inevitable conclusion.

But Malthus did not stop there. Recall that the geometric ratio pertained to population growth in the absence of any checks. It is a discussion of the possible checks, in theory and in practice, that comprises the bulk of Malthus’ Essay. He discusses two types of checks, positive and preventive.

Positive checks are defined in Book I, Chapter 2, paragraph 9 as including “every cause, whether arising from vice or misery, which in any degree contributes to shorten the natural duration of human life.” He listed several examples: “Under this head, therefore, may be enumerated all unwholesome occupations, severe labour and exposure to the seasons, extreme poverty, bad nursing of children, great towns, excesses of all kinds, the whole train of common diseases and epidemics, wars, plague, and famine.” Positive checks of one sort or another work against the growth of all living things, plants and animals alike.

Preventive checks, on the other hand, are unique to humans because only humans possess the self-awareness, reason and foresight to look down the road and consciously decide whether or not to procreate. A person, as Malthus wrote in Book I, Chapter 2, paragraph 4,

cannot contemplate his present possessions or earnings, which he now nearly consumes himself… without feeling a doubt whether, if he follow the bent of his inclinations, he may be able to support the offspring which he will probably bring into the world…. Will he not lower his rank in life, and be obliged to give up in great measure his former habits? Will he not be unable to transmit to his children the same advantages of education and improvement that he had himself possessed? Does he even feel secure that, should he have a large family, his utmost exertions can save them from rags and squalid poverty, and their consequent degradation in the community?

“These considerations,” he continues in the next paragraph, “are calculated to prevent, and certainly do prevent, a great number of persons in all civilized nations from pursuing the dictate of nature in an early attachment to one woman.”

Malthus’ study of preventive checks, which covered regions around the globe and in various stages in mankind’s history, was a study of human agents making conscious, rational decisions calculated to maximize their own self-interest and the interest of their potential offspring. It was the examination of how individuals check their own behavior for their own benefit that elevated Malthus’ Essay beyond a simple mathematical description of population growth, and into a work of economic theory and practice that was remarkably innovative for its day and well-respected by contemporary economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo. However, this aspect of the Essay was ignored, misunderstood, or derided in much of the rest of society.

It is the interplay of both positive and preventive checks that, according to Malthus, keep human population from actually growing at a geometric rate. Although at some times and places when the means of subsistence suddenly expands greatly, as was the case when North American settlers were spreading across a continent of largely uncultivated land, populations could grow unimpeded by significant checks, eventually that growth would be met by a limitation on the amount of food that the land could produce. The impending food scarcity would, without a preventive check, generate positive checks in the form of food shortages, hunger, and poverty. However, thanks to mankind’s cognitive abilities, people would see these dire consequences and, before they arose, impose on themselves a preventive check in the form of having fewer children. In this way, population would usually hover close to, but not go beyond, the means of subsistence.

This is not to say that famines, when the amount of food available in a certain location is simply not enough for everyone there to survive, could not occur. He was not blind to the fact that famines were a recurrent fact of life in his day. He wrote in Book II, Chapter 13, paragraph 18, that “though the principle of population cannot absolutely produce a famine, it prepares the way for one; and by frequently obliging the lower classes of people to subsist nearly on the smallest quantity of food that will support life, turns even a slight deficiency from the failure of the seasons into a severe dearth.” According to Malthus, famines happen, and population pressures are a key factor in them. However, nothing in his theory of population growth necessitates the massive, widespread famine that many past and current writers claim was his main prediction.

Early Misconceptions about Malthus’ Theory

Soon after Malthus’ Essay was first published, many responses appeared to attack his work. One of the most vociferous critics was William Godwin, the English philosopher and writer whose discourse on population in his book, On Population (1793), first prompted Malthus to write his Essay. In 1820, Godwin published Of Population, subtitled Being an Answer to Mr. Malthus’s Essay on That Subject, which was the source of the earlier quotes about “inexpressible abhorrence” and Malthus’ creed being diametrically opposed to the Bible. In his On Population, Godwin founded his objections to Malthus’ theory on two connected points.

First, Godwin claimed that Malthus’ position was that people everywhere do in fact have enough babies such that if they all survived to adulthood, population would double in size every twenty-five years. Godwin then estimated how many births per marriage would be necessary for this doubling to occur, taking into account the number of babies that do not survive and the number of people who never marry. On page 29 of his On Population, he concluded that “When Mr. Malthus therefore requires us to believe in the geometrical ratio, or that the human species has a natural tendency to double itself every twenty-five years, he does nothing less in other words, than require us to believe that every marriage among human creatures produces on average… eight children.” He then chastised Malthus for not examining the registers of marriages and births of different countries and realizing that so many children are not really born.

The French economist Frederic Bastiat defended Malthus from Godwin and other critics in Chapter 16 of Economic Harmonies (1996, first pub. 1850). On this question of the geometric ratio, Bastiat wrote in paragraph 52 that “Malthus never advanced the fatuous premise that ‘mankind, in actual fact, multiplies in geometrical ratio.’ He says, on the contrary, that this is not in fact the case, since he is investigating the obstacles that prevent it from being so, and he offers this ratio merely as a formula to show the physiological potential of reproduction.” That Godwin and others did not see this, particularly after Malthus’ clarifications in the second edition, betrays at least a case of willful blindness.

Godwin’s second point began with his noting that in most European countries, population was more or less stable. He then claimed that Malthus’ theory could not be true unless huge numbers of all of those children being born in the light of Godwin’s first assertion were dying before they reached maturity, a fact not borne out by birth and death registers. Further, Godwin states that Malthus himself argues implicitly that population is not checked by fewer children being born, but by early deaths. On page 32, Godwin wrote that:

Mr. Malthus has added in his subsequent editions, to the two checks upon population, viz. vice and misery, as they stood in the first, a third which he calls moral restraint. But then he expressly qualifies this by saying, “the principle of moral restraint has undoubtedly in past ages operated with very inconsiderable force;” subjoining at the same time his protest against “any opinion respecting the probable improvement of society, in which we are not borne out by the experience of the past.”

It is clearly therefore Mr. Malthus’s doctrine, that population is kept down in the Old World, not by a smaller number of children being born among us, but by the excessive number of children that perish in their nonage through the instrumentality of vice and misery.

According to Godwin’s indictment of Malthus, then, Malthus believed that moral restraint, or to use the terminology introduced in a previous section, the use of preventive checks, was insignificant in past ages. Further, Godwin maintained that Malthus believed that experience provides no reason to believe that society has improved in this regard since that time. Therefore, Godwin claimed, Malthus must not believe that moral restraint, or preventive checks, were of any significance during the men’s own time.

Let’s take a closer look at Godwin’s argument, and see where it goes wrong. First, with his phrase “subjoining at the same time,” Godwin gives the impression that the two quotes from Malthus are connected. However, an examination of Godwin’s footnotes reveals that these quotes appear nearly four hundred pages apart, the first quote being on page 384 of the second edition of Essay, while the second quote is found in paragraph 8 of the Preface to the second edition. 3 Therefore, Malthus can hardly be thought to have intended the two quotes to be part of a continuous argument.

Godwin did something even sneakier. Godwin claimed that Malthus protested against “any opinion respecting the probable improvement of society, in which we are not borne out by the experience of the past,” (my italics). If we check this against what Malthus actually wrote, we find that Godwin cropped a phrase out of the Preface and subtly altered the words, creating a crucial difference in meaning. A fuller and more accurate quote from Malthus is “I hope that I have not violated the principles of just reasoning; nor expressed any opinion respecting the probable improvement of society, in which I am not borne out by the experience of the past,” (again, my italics). Malthus was not protesting against the idea that society may have improved, as Godwin portrayed by changing Malthus’ use of the first person to the third person. Instead, Malthus was claiming that any assertion he actually did make about society’s improvement was based on the experience of the past. Malthus did not deny that society had improved in terms of moral restraint, he believed that it did and that the evidence confirmed it!

On Malthus’ part, the “past ages” to which he referred in the second edition of Essay could be interpreted as meaning any time from the centuries immediately prior to his writing to the furthest reaches of human history. This phrase, taken alone, leaves open ambiguity about whether Malthus thought that moral restraint, or the preventive check, was active in his day. Unfortunately for Godwin, Malthus made unambiguous remarks about his belief in the presence of a preventive check working to cause fewer births. In paragraph 9 of Chapter 4 of the first edition, he wrote that “The preventive check appears to operate in some degree through all the ranks of society in England.” In the first paragraph of Book II, Chapter 8 of the sixth edition, Malthus is even more forceful: “The most cursory view of society in this country must convince us, that throughout all ranks the preventive check to population prevails in a considerable degree.” It strains credulity that one could read with good faith even Malthus’ earliest edition and not recognize that he thought a preventive check was at work.

Improvement in the Human Condition

A final subject in which Malthus’ views have been misunderstood is his thoughts concerning whether poverty could be reduced and the human condition, especially of the poor, might be improved. He is characterized as having been utterly pessimistic on this front, believing that a gloomy, miserable existence was all that is in store for us.

Godwin wrote dramatically on this theme. On pages 111-112 of On Population, he wrote that “The great tendency and effect of Mr. Malthus’s book were to warn us against making mankind happy. Such an event must necessarily lead, according to him, to the most pernicious consequences. A due portion of vice and misery was held out to us as the indispensible preservative of society.” More disheartening, on page 144 he described Malthus as “fully convinced that he has shewn in ‘the laws of nature and the passions of mankind’ an evil, for which all remedies are feeble, and before which courage must sink into despair.”

Even Bastiat, who as we have seen defended Malthus on other fronts, believed that the end result of Malthus’ thinking was perpetual poverty. In Chapter 16, paragraph 90 of Economic Harmonies, he opined that “Malthus… was consequently led to pessimistic conclusions, and these in turn have aroused public opinion against him…. Hence, it was his belief that the repressive (or, as he called it, the positive) check would be the decisive one; in other words, vice, poverty, war, crime, etc.” Bastiat continued this thought in paragraph 98:

He declares that, taking into consideration absolute fertility, on the one hand, and, on the other, the means of limiting it in the form of either repression or prevention, we find that the result is nonetheless a tendency for population to increase faster than the means of subsistence…. If it were true, as Malthus says, that for each increase in the means of existence there is a corresponding and greater increase in population, the poverty of our race would necessarily be constantly on the increase, and civilization would stand at the beginning of time, and barbarism at the end.

Malthus did persistently discuss how population grows until it is limited by the means of subsistence, and from that, critics and supporters alike came away from his Essay with the impression that Malthus saw no betterment in humanity’s future. However, there are several instances in which Malthus blatantly and unmistakably expressed hope for improvement, albeit perhaps slow, in the condition of the poor and humanity in general.

In paragraph 12 of Book IV, Chapter 3, he wrote that

We are not however to relax our efforts in increasing the quantity of provisions, but to combine another effort with it; that of keeping the population, when once it has been overtaken, at such a distance behind, as to effect the relative proportion which we desire; and thus unite the two grind [sic] desiderata, a great actual population, and a state of society, in which abject poverty and dependence are comparatively but little known; two objects which are far from being incompatible.

More concretely, in paragraph 2 of Book IV, Chapter 4, he predicted that “I can easily conceive that this country, with a proper direction of the national industry, might, in the course of some centuries, contain two or three times its present population, and yet every man in the kingdom be much better fed and clothed than he is at present.”

Finally, paragraph 14 of Book IV, Chapter 14, Malthus’ concluding paragraph, should have dispelled any notion that he saw no progress in store for humanity: