Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Research Guides

Multiple Case Studies

Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu

Description

The case study approach is popular across disciplines in education, anthropology, sociology, psychology, medicine, law, and political science (Creswell, 2013). It is both a research method and a strategy (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2017). In this type of research design, a case can be an individual, an event, or an entity, as determined by the research questions. There are two variants of the case study: the single-case study and the multiple-case study. The former design can be used to study and understand an unusual case, a critical case, a longitudinal case, or a revelatory case. On the other hand, a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003; Yin, 2017). …a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena

The difference between the single- and multiple-case study is the research design; however, they are within the same methodological framework (Yin, 2017). Multiple cases are selected so that “individual case studies either (a) predict similar results (a literal replication) or (b) predict contrasting results but for anticipatable reasons (a theoretical replication)” (p. 55). When the purpose of the study is to compare and replicate the findings, the multiple-case study produces more compelling evidence so that the study is considered more robust than the single-case study (Yin, 2017).

To write a multiple-case study, a summary of individual cases should be reported, and researchers need to draw cross-case conclusions and form a cross-case report (Yin, 2017). With evidence from multiple cases, researchers may have generalizable findings and develop theories (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003).

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2003). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Key Research Books and Articles on Multiple Case Study Methodology

Yin discusses how to decide if a case study should be used in research. Novice researchers can learn about research design, data collection, and data analysis of different types of case studies, as well as writing a case study report.

Chapter 2 introduces four major types of research design in case studies: holistic single-case design, embedded single-case design, holistic multiple-case design, and embedded multiple-case design. Novice researchers will learn about the definitions and characteristics of different designs. This chapter also teaches researchers how to examine and discuss the reliability and validity of the designs.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

This book compares five different qualitative research designs: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study. It compares the characteristics, data collection, data analysis and representation, validity, and writing-up procedures among five inquiry approaches using texts with tables. For each approach, the author introduced the definition, features, types, and procedures and contextualized these components in a study, which was conducted through the same method. Each chapter ends with a list of relevant readings of each inquiry approach.

This book invites readers to compare these five qualitative methods and see the value of each approach. Readers can consider which approach would serve for their research contexts and questions, as well as how to design their research and conduct the data analysis based on their choice of research method.

Günes, E., & Bahçivan, E. (2016). A multiple case study of preservice science teachers’ TPACK: Embedded in a comprehensive belief system. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11 (15), 8040-8054.

In this article, the researchers showed the importance of using technological opportunities in improving the education process and how they enhanced the students’ learning in science education. The study examined the connection between “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (TPACK) and belief system in a science teaching context. The researchers used the multiple-case study to explore the effect of TPACK on the preservice science teachers’ (PST) beliefs on their TPACK level. The participants were three teachers with the low, medium, and high level of TPACK confidence. Content analysis was utilized to analyze the data, which were collected by individual semi-structured interviews with the participants about their lesson plans. The study first discussed each case, then compared features and relations across cases. The researchers found that there was a positive relationship between PST’s TPACK confidence and TPACK level; when PST had higher TPACK confidence, the participant had a higher competent TPACK level and vice versa.

Recent Dissertations Using Multiple Case Study Methodology

Milholland, E. S. (2015). A multiple case study of instructors utilizing Classroom Response Systems (CRS) to achieve pedagogical goals . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3706380)

The researcher of this study critiques the use of Classroom Responses Systems by five instructors who employed this program five years ago in their classrooms. The researcher conducted the multiple-case study methodology and categorized themes. He interviewed each instructor with questions about their initial pedagogical goals, the changes in pedagogy during teaching, and the teaching techniques individuals used while practicing the CRS. The researcher used the multiple-case study with five instructors. He found that all instructors changed their goals during employing CRS; they decided to reduce the time of lecturing and to spend more time engaging students in interactive activities. This study also demonstrated that CRS was useful for the instructors to achieve multiple learning goals; all the instructors provided examples of the positive aspect of implementing CRS in their classrooms.

Li, C. L. (2010). The emergence of fairy tale literacy: A multiple case study on promoting critical literacy of children through a juxtaposed reading of classic fairy tales and their contemporary disruptive variants . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3572104)

To explore how children’s development of critical literacy can be impacted by their reactions to fairy tales, the author conducted a multiple-case study with 4 cases, in which each child was a unit of analysis. Two Chinese immigrant children (a boy and a girl) and two American children (a boy and a girl) at the second or third grade were recruited in the study. The data were collected through interviews, discussions on fairy tales, and drawing pictures. The analysis was conducted within both individual cases and cross cases. Across four cases, the researcher found that the young children’s’ knowledge of traditional fairy tales was built upon mass-media based adaptations. The children believed that the representations on mass-media were the original stories, even though fairy tales are included in the elementary school curriculum. The author also found that introducing classic versions of fairy tales increased children’s knowledge in the genre’s origin, which would benefit their understanding of the genre. She argued that introducing fairy tales can be the first step to promote children’s development of critical literacy.

Asher, K. C. (2014). Mediating occupational socialization and occupational individuation in teacher education: A multiple case study of five elementary pre-service student teachers . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3671989)

This study portrayed five pre-service teachers’ teaching experience in their student teaching phase and explored how pre-service teachers mediate their occupational socialization with occupational individuation. The study used the multiple-case study design and recruited five pre-service teachers from a Midwestern university as five cases. Qualitative data were collected through interviews, classroom observations, and field notes. The author implemented the case study analysis and found five strategies that the participants used to mediate occupational socialization with occupational individuation. These strategies were: 1) hindering from practicing their beliefs, 2) mimicking the styles of supervising teachers, 3) teaching in the ways in alignment with school’s existing practice, 4) enacting their own ideas, and 5) integrating and balancing occupational socialization and occupational individuation. The study also provided recommendations and implications to policymakers and educators in teacher education so that pre-service teachers can be better supported.

Multiple Case Studies Copyright © 2019 by Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Case study research: opening up research opportunities

RAUSP Management Journal

ISSN : 2531-0488

Article publication date: 30 December 2019

Issue publication date: 3 March 2020

The case study approach has been widely used in management studies and the social sciences more generally. However, there are still doubts about when and how case studies should be used. This paper aims to discuss this approach, its various uses and applications, in light of epistemological principles, as well as the criteria for rigor and validity.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper discusses the various concepts of case and case studies in the methods literature and addresses the different uses of cases in relation to epistemological principles and criteria for rigor and validity.

The use of this research approach can be based on several epistemologies, provided the researcher attends to the internal coherence between method and epistemology, or what the authors call “alignment.”

Originality/value

This study offers a number of implications for the practice of management research, as it shows how the case study approach does not commit the researcher to particular data collection or interpretation methods. Furthermore, the use of cases can be justified according to multiple epistemological orientations.

- Epistemology

Takahashi, A.R.W. and Araujo, L. (2020), "Case study research: opening up research opportunities", RAUSP Management Journal , Vol. 55 No. 1, pp. 100-111. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-05-2019-0109

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Adriana Roseli Wünsch Takahashi and Luis Araujo.

Published in RAUSP Management Journal . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The case study as a research method or strategy brings us to question the very term “case”: after all, what is a case? A case-based approach places accords the case a central role in the research process ( Ragin, 1992 ). However, doubts still remain about the status of cases according to different epistemologies and types of research designs.

Despite these doubts, the case study is ever present in the management literature and represents the main method of management research in Brazil ( Coraiola, Sander, Maccali, & Bulgacov, 2013 ). Between 2001 and 2010, 2,407 articles (83.14 per cent of qualitative research) were published in conferences and management journals as case studies (Takahashi & Semprebom, 2013 ). A search on Spell.org.br for the term “case study” under title, abstract or keywords, for the period ranging from January 2010 to July 2019, yielded 3,040 articles published in the management field. Doing research using case studies, allows the researcher to immerse him/herself in the context and gain intensive knowledge of a phenomenon, which in turn demands suitable methodological principles ( Freitas et al. , 2017 ).

Our objective in this paper is to discuss notions of what constitutes a case and its various applications, considering epistemological positions as well as criteria for rigor and validity. The alignment between these dimensions is put forward as a principle advocating coherence among all phases of the research process.

This article makes two contributions. First, we suggest that there are several epistemological justifications for using case studies. Second, we show that the quality and rigor of academic research with case studies are directly related to the alignment between epistemology and research design rather than to choices of specific forms of data collection or analysis. The article is structured as follows: the following four sections discuss concepts of what is a case, its uses, epistemological grounding as well as rigor and quality criteria. The brief conclusions summarize the debate and invite the reader to delve into the literature on the case study method as a way of furthering our understanding of contemporary management phenomena.

2. What is a case study?

The debate over what constitutes a case in social science is a long-standing one. In 1988, Howard Becker and Charles Ragin organized a workshop to discuss the status of the case as a social science method. As the discussion was inconclusive, they posed the question “What is a case?” to a select group of eight social scientists in 1989, and later to participants in a symposium on the subject. Participants were unable to come up with a consensual answer. Since then, we have witnessed that further debates and different answers have emerged. The original question led to an even broader issue: “How do we, as social scientists, produce results and seem to know what we know?” ( Ragin, 1992 , p. 16).

An important step that may help us start a reflection on what is a case is to consider the phenomena we are looking at. To do that, we must know something about what we want to understand and how we might study it. The answer may be a causal explanation, a description of what was observed or a narrative of what has been experienced. In any case, there will always be a story to be told, as the choice of the case study method demands an answer to what the case is about.

A case may be defined ex ante , prior to the start of the research process, as in Yin’s (2015) classical definition. But, there is no compelling reason as to why cases must be defined ex ante . Ragin (1992 , p. 217) proposed the notion of “casing,” to indicate that what the case is emerges from the research process:

Rather than attempt to delineate the many different meanings of the term “case” in a formal taxonomy, in this essay I offer instead a view of cases that follows from the idea implicit in many of the contributions – that concocting cases is a varied but routine social scientific activity. […] The approach of this essay is that this activity, which I call “casing”, should be viewed in practical terms as a research tactic. It is selectively invoked at many different junctures in the research process, usually to resolve difficult issues in linking ideas and evidence.

In other words, “casing” is tied to the researcher’s practice, to the way he/she delimits or declares a case as a significant outcome of a process. In 2013, Ragin revisited the 1992 concept of “casing” and explored its multiple possibilities of use, paying particular attention to “negative cases.”

According to Ragin (1992) , a case can be centered on a phenomenon or a population. In the first scenario, cases are representative of a phenomenon, and are selected based on what can be empirically observed. The process highlights different aspects of cases and obscures others according to the research design, and allows for the complexity, specificity and context of the phenomenon to be explored. In the alternative, population-focused scenario, the selection of cases precedes the research. Both positive and negative cases are considered in exploring a phenomenon, with the definition of the set of cases dependent on theory and the central objective to build generalizations. As a passing note, it is worth mentioning here that a study of multiple cases requires a definition of the unit of analysis a priori . Otherwise, it will not be possible to make cross-case comparisons.

These two approaches entail differences that go beyond the mere opposition of quantitative and qualitative data, as a case often includes both types of data. Thus, the confusion about how to conceive cases is associated with Ragin’s (1992) notion of “small vs large N,” or McKeown’s (1999) “statistical worldview” – the notion that relevant findings are only those that can be made about a population based on the analysis of representative samples. In the same vein, Byrne (2013) argues that we cannot generate nomothetic laws that apply in all circumstances, periods and locations, and that no social science method can claim to generate invariant laws. According to the same author, case studies can help us understand that there is more than one ideographic variety and help make social science useful. Generalizations still matter, but they should be understood as part of defining the research scope, and that scope points to the limitations of knowledge produced and consumed in concrete time and space.

Thus, what defines the orientation and the use of cases is not the mere choice of type of data, whether quantitative or qualitative, but the orientation of the study. A statistical worldview sees cases as data units ( Byrne, 2013 ). Put differently, there is a clear distinction between statistical and qualitative worldviews; the use of quantitative data does not by itself means that the research is (quasi) statistical, or uses a deductive logic:

Case-based methods are useful, and represent, among other things, a way of moving beyond a useless and destructive tradition in the social sciences that have set quantitative and qualitative modes of exploration, interpretation, and explanation against each other ( Byrne, 2013 , p. 9).

Other authors advocate different understandings of what a case study is. To some, it is a research method, to others it is a research strategy ( Creswell, 1998 ). Sharan Merrian and Robert Yin, among others, began to write about case study research as a methodology in the 1980s (Merrian, 2009), while authors such as Eisenhardt (1989) called it a research strategy. Stake (2003) sees the case study not as a method, but as a choice of what to be studied, the unit of study. Regardless of their differences, these authors agree that case studies should be restricted to a particular context as they aim to provide an in-depth knowledge of a given phenomenon: “A case study is an in-depth description and analysis of a bounded system” (Merrian, 2009, p. 40). According to Merrian, a qualitative case study can be defined by the process through which the research is carried out, by the unit of analysis or the final product, as the choice ultimately depends on what the researcher wants to know. As a product of research, it involves the analysis of a given entity, phenomenon or social unit.

Thus, whether it is an organization, an individual, a context or a phenomenon, single or multiple, one must delimit it, and also choose between possible types and configurations (Merrian, 2009; Yin, 2015 ). A case study may be descriptive, exploratory, explanatory, single or multiple ( Yin, 2015 ); intrinsic, instrumental or collective ( Stake, 2003 ); and confirm or build theory ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ).

both went through the same process of implementing computer labs intended for the use of information and communication technologies in 2007;

both took part in the same regional program (Paraná Digital); and

they shared similar characteristics regarding location (operation in the same neighborhood of a city), number of students, number of teachers and technicians and laboratory sizes.

However, the two institutions differed in the number of hours of program use, with one of them displaying a significant number of hours/use while the other showed a modest number, according to secondary data for the period 2007-2013. Despite the context being similar and the procedures for implementing the technology being the same, the mechanisms of social integration – an idiosyncratic factor of each institution – were different in each case. This explained differences in their use of resource, processes of organizational learning and capacity to absorb new knowledge.

On the other hand, multiple case studies seek evidence in different contexts and do not necessarily require direct comparisons ( Stake, 2003 ). Rather, there is a search for patterns of convergence and divergence that permeate all the cases, as the same issues are explored in every case. Cases can be added progressively until theoretical saturation is achieved. An example is of a study that investigated how entrepreneurial opportunity and management skills were developed through entrepreneurial learning ( Zampier & Takahashi, 2014 ). The authors conducted nine case studies, based on primary and secondary data, with each one analyzed separately, so a search for patterns could be undertaken. The convergence aspects found were: the predominant way of transforming experience into knowledge was exploitation; managerial skills were developed through by taking advantages of opportunities; and career orientation encompassed more than one style. As for divergence patterns: the experience of success and failure influenced entrepreneurs differently; the prevailing rationality logic of influence was different; and the combination of styles in career orientation was diverse.

A full discussion of choice of case study design is outside the scope of this article. For the sake of illustration, we make a brief mention to other selection criteria such as the purpose of the research, the state of the art of the research theme, the time and resources involved and the preferred epistemological position of the researcher. In the next section, we look at the possibilities of carrying out case studies in line with various epistemological traditions, as the answers to the “what is a case?” question reveal varied methodological commitments as well as diverse epistemological and ontological positions ( Ragin, 2013 ).

3. Epistemological positioning of case study research

Ontology and epistemology are like skin, not a garment to be occasionally worn ( Marsh & Furlong, 2002 ). According to these authors, ontology and epistemology guide the choice of theory and method because they cannot or should not be worn as a garment. Hence, one must practice philosophical “self-knowledge” to recognize one’s vision of what the world is and of how knowledge of that world is accessed and validated. Ontological and epistemological positions are relevant in that they involve the positioning of the researcher in social science and the phenomena he or she chooses to study. These positions do not tend to vary from one project to another although they can certainly change over time for a single researcher.

Ontology is the starting point from which the epistemological and methodological positions of the research arise ( Grix, 2002 ). Ontology expresses a view of the world, what constitutes reality, nature and the image one has of social reality; it is a theory of being ( Marsh & Furlong, 2002 ). The central question is the nature of the world out there regardless of our ability to access it. An essentialist or foundationalist ontology acknowledges that there are differences that persist over time and these differences are what underpin the construction of social life. An opposing, anti-foundationalist position presumes that the differences found are socially constructed and may vary – i.e. they are not essential but specific to a given culture at a given time ( Marsh & Furlong, 2002 ).

Epistemology is centered around a theory of knowledge, focusing on the process of acquiring and validating knowledge ( Grix, 2002 ). Positivists look at social phenomena as a world of causal relations where there is a single truth to be accessed and confirmed. In this tradition, case studies test hypotheses and rely on deductive approaches and quantitative data collection and analysis techniques. Scholars in the field of anthropology and observation-based qualitative studies proposed alternative epistemologies based on notions of the social world as a set of manifold and ever-changing processes. In management studies since the 1970s, the gradual acceptance of qualitative research has generated a diverse range of research methods and conceptions of the individual and society ( Godoy, 1995 ).

The interpretative tradition, in direct opposition to positivism, argues that there is no single objective truth to be discovered about the social world. The social world and our knowledge of it are the product of social constructions. Thus, the social world is constituted by interactions, and our knowledge is hermeneutic as the world does not exist independent of our knowledge ( Marsh & Furlong, 2002 ). The implication is that it is not possible to access social phenomena through objective, detached methods. Instead, the interaction mechanisms and relationships that make up social constructions have to be studied. Deductive approaches, hypothesis testing and quantitative methods are not relevant here. Hermeneutics, on the other hand, is highly relevant as it allows the analysis of the individual’s interpretation, of sayings, texts and actions, even though interpretation is always the “truth” of a subject. Methods such as ethnographic case studies, interviews and observations as data collection techniques should feed research designs according to interpretivism. It is worth pointing out that we are to a large extent, caricaturing polar opposites rather characterizing a range of epistemological alternatives, such as realism, conventionalism and symbolic interactionism.

If diverse ontologies and epistemologies serve as a guide to research approaches, including data collection and analysis methods, and if they should be regarded as skin rather than clothing, how does one make choices regarding case studies? What are case studies, what type of knowledge they provide and so on? The views of case study authors are not always explicit on this point, so we must delve into their texts to glean what their positions might be.

Two of the cited authors in case study research are Robert Yin and Kathleen Eisenhardt. Eisenhardt (1989) argues that a case study can serve to provide a description, test or generate a theory, the latter being the most relevant in contributing to the advancement of knowledge in a given area. She uses terms such as populations and samples, control variables, hypotheses and generalization of findings and even suggests an ideal number of case studies to allow for theory construction through replication. Although Eisenhardt includes observation and interview among her recommended data collection techniques, the approach is firmly anchored in a positivist epistemology:

Third, particularly in comparison with Strauss (1987) and Van Maanen (1988), the process described here adopts a positivist view of research. That is, the process is directed toward the development of testable hypotheses and theory which are generalizable across settings. In contrast, authors like Strauss and Van Maanen are more concerned that a rich, complex description of the specific cases under study evolve and they appear less concerned with development of generalizable theory ( Eisenhardt, 1989 , p. 546).

This position attracted a fair amount of criticism. Dyer & Wilkins (1991) in a critique of Eisenhardt’s (1989) article focused on the following aspects: there is no relevant justification for the number of cases recommended; it is the depth and not the number of cases that provides an actual contribution to theory; and the researcher’s purpose should be to get closer to the setting and interpret it. According to the same authors, discrepancies from prior expectations are also important as they lead researchers to reflect on existing theories. Eisenhardt & Graebner (2007 , p. 25) revisit the argument for the construction of a theory from multiple cases:

A major reason for the popularity and relevance of theory building from case studies is that it is one of the best (if not the best) of the bridges from rich qualitative evidence to mainstream deductive research.

Although they recognize the importance of single-case research to explore phenomena under unique or rare circumstances, they reaffirm the strength of multiple case designs as it is through them that better accuracy and generalization can be reached.

Likewise, Robert Yin emphasizes the importance of variables, triangulation in the search for “truth” and generalizable theoretical propositions. Yin (2015 , p. 18) suggests that the case study method may be appropriate for different epistemological orientations, although much of his work seems to invoke a realist epistemology. Authors such as Merrian (2009) and Stake (2003) suggest an interpretative version of case studies. Stake (2003) looks at cases as a qualitative option, where the most relevant criterion of case selection should be the opportunity to learn and understand a phenomenon. A case is not just a research method or strategy; it is a researcher’s choice about what will be studied:

Even if my definition of case study was agreed upon, and it is not, the term case and study defy full specification (Kemmis, 1980). A case study is both a process of inquiry about the case and the product of that inquiry ( Stake, 2003 , p. 136).

Later, Stake (2003 , p. 156) argues that:

[…] the purpose of a case report is not to represent the world, but to represent the case. […] The utility of case research to practitioners and policy makers is in its extension of experience.

Still according to Stake (2003 , pp. 140-141), to do justice to complex views of social phenomena, it is necessary to analyze the context and relate it to the case, to look for what is peculiar rather than common in cases to delimit their boundaries, to plan the data collection looking for what is common and unusual about facts, what could be valuable whether it is unique or common:

Reflecting upon the pertinent literature, I find case study methodology written largely by people who presume that the research should contribute to scientific generalization. The bulk of case study work, however, is done by individuals who have intrinsic interest in the case and little interest in the advance of science. Their designs aim the inquiry toward understanding of what is important about that case within its own world, which is seldom the same as the worlds of researchers and theorists. Those designs develop what is perceived to be the case’s own issues, contexts, and interpretations, its thick descriptions . In contrast, the methods of instrumental case study draw the researcher toward illustrating how the concerns of researchers and theorists are manifest in the case. Because the critical issues are more likely to be know in advance and following disciplinary expectations, such a design can take greater advantage of already developed instruments and preconceived coding schemes.

The aforementioned authors were listed to illustrate differences and sometimes opposing positions on case research. These differences are not restricted to a choice between positivism and interpretivism. It is worth noting that Ragin’s (2013 , p. 523) approach to “casing” is compatible with the realistic research perspective:

In essence, to posit cases is to engage in ontological speculation regarding what is obdurately real but only partially and indirectly accessible through social science. Bringing a realist perspective to the case question deepens and enriches the dialogue, clarifying some key issues while sweeping others aside.

cases are actual entities, reflecting their operations of real causal mechanism and process patterns;

case studies are interactive processes and are open to revisions and refinements; and

social phenomena are complex, contingent and context-specific.

Ragin (2013 , p. 532) concludes:

Lurking behind my discussion of negative case, populations, and possibility analysis is the implication that treating cases as members of given (and fixed) populations and seeking to infer the properties of populations may be a largely illusory exercise. While demographers have made good use of the concept of population, and continue to do so, it is not clear how much the utility of the concept extends beyond their domain. In case-oriented work, the notion of fixed populations of cases (observations) has much less analytic utility than simply “the set of relevant cases,” a grouping that must be specified or constructed by the researcher. The demarcation of this set, as the work of case-oriented researchers illustrates, is always tentative, fluid, and open to debate. It is only by casing social phenomena that social scientists perceive the homogeneity that allows analysis to proceed.

In summary, case studies are relevant and potentially compatible with a range of different epistemologies. Researchers’ ontological and epistemological positions will guide their choice of theory, methodologies and research techniques, as well as their research practices. The same applies to the choice of authors describing the research method and this choice should be coherent. We call this research alignment , an attribute that must be judged on the internal coherence of the author of a study, and not necessarily its evaluator. The following figure illustrates the interrelationship between the elements of a study necessary for an alignment ( Figure 1 ).

In addition to this broader aspect of the research as a whole, other factors should be part of the researcher’s concern, such as the rigor and quality of case studies. We will look into these in the next section taking into account their relevance to the different epistemologies.

4. Rigor and quality in case studies

Traditionally, at least in positivist studies, validity and reliability are the relevant quality criteria to judge research. Validity can be understood as external, internal and construct. External validity means identifying whether the findings of a study are generalizable to other studies using the logic of replication in multiple case studies. Internal validity may be established through the theoretical underpinning of existing relationships and it involves the use of protocols for the development and execution of case studies. Construct validity implies defining the operational measurement criteria to establish a chain of evidence, such as the use of multiple sources of evidence ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ; Yin, 2015 ). Reliability implies conducting other case studies, instead of just replicating results, to minimize the errors and bias of a study through case study protocols and the development of a case database ( Yin, 2015 ).

Several criticisms have been directed toward case studies, such as lack of rigor, lack of generalization potential, external validity and researcher bias. Case studies are often deemed to be unreliable because of a lack of rigor ( Seuring, 2008 ). Flyvbjerg (2006 , p. 219) addresses five misunderstandings about case-study research, and concludes that:

[…] a scientific discipline without a large number of thoroughly executed case studies is a discipline without systematic production of exemplars, and a discipline without exemplars is an ineffective one.

theoretical knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical knowledge;

the case study cannot contribute to scientific development because it is not possible to generalize on the basis of an individual case;

the case study is more useful for generating rather than testing hypotheses;

the case study contains a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions; and

it is difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories based on case studies.

These criticisms question the validity of the case study as a scientific method and should be corrected.

The critique of case studies is often framed from the standpoint of what Ragin (2000) labeled large-N research. The logic of small-N research, to which case studies belong, is different. Cases benefit from depth rather than breadth as they: provide theoretical and empirical knowledge; contribute to theory through propositions; serve not only to confirm knowledge, but also to challenge and overturn preconceived notions; and the difficulty in summarizing their conclusions is because of the complexity of the phenomena studies and not an intrinsic limitation of the method.

Thus, case studies do not seek large-scale generalizations as that is not their purpose. And yet, this is a limitation from a positivist perspective as there is an external reality to be “apprehended” and valid conclusions to be extracted for an entire population. If positivism is the epistemology of choice, the rigor of a case study can be demonstrated by detailing the criteria used for internal and external validity, construct validity and reliability ( Gibbert & Ruigrok, 2010 ; Gibbert, Ruigrok, & Wicki, 2008 ). An example can be seen in case studies in the area of information systems, where there is a predominant orientation of positivist approaches to this method ( Pozzebon & Freitas, 1998 ). In this area, rigor also involves the definition of a unit of analysis, type of research, number of cases, selection of sites, definition of data collection and analysis procedures, definition of the research protocol and writing a final report. Creswell (1998) presents a checklist for researchers to assess whether the study was well written, if it has reliability and validity and if it followed methodological protocols.

In case studies with a non-positivist orientation, rigor can be achieved through careful alignment (coherence among ontology, epistemology, theory and method). Moreover, the concepts of validity can be understood as concern and care in formulating research, research development and research results ( Ollaik & Ziller, 2012 ), and to achieve internal coherence ( Gibbert et al. , 2008 ). The consistency between data collection and interpretation, and the observed reality also help these studies meet coherence and rigor criteria. Siggelkow (2007) argues that a case study should be persuasive and that even a single case study may be a powerful example to contest a widely held view. To him, the value of a single case study or studies with few cases can be attained by their potential to provide conceptual insights and coherence to the internal logic of conceptual arguments: “[…] a paper should allow a reader to see the world, and not just the literature, in a new way” ( Siggelkow, 2007 , p. 23).

Interpretative studies should not be justified by criteria derived from positivism as they are based on a different ontology and epistemology ( Sandberg, 2005 ). The rejection of an interpretive epistemology leads to the rejection of an objective reality: “As Bengtsson points out, the life-world is the subjects’ experience of reality, at the same time as it is objective in the sense that it is an intersubjective world” ( Sandberg, 2005 , p. 47). In this event, how can one demonstrate what positivists call validity and reliability? What would be the criteria to justify knowledge as truth, produced by research in this epistemology? Sandberg (2005 , p. 62) suggests an answer based on phenomenology:

This was demonstrated first by explicating life-world and intentionality as the basic assumptions underlying the interpretative research tradition. Second, based on those assumptions, truth as intentional fulfillment, consisting of perceived fulfillment, fulfillment in practice, and indeterminate fulfillment, was proposed. Third, based on the proposed truth constellation, communicative, pragmatic, and transgressive validity and reliability as interpretative awareness were presented as the most appropriate criteria for justifying knowledge produced within interpretative approach. Finally, the phenomenological epoché was suggested as a strategy for achieving these criteria.

From this standpoint, the research site must be chosen according to its uniqueness so that one can obtain relevant insights that no other site could provide ( Siggelkow, 2007 ). Furthermore, the view of what is being studied is at the center of the researcher’s attention to understand its “truth,” inserted in a given context.

The case researcher is someone who can reduce the probability of misinterpretations by analyzing multiple perceptions, searches for data triangulation to check for the reliability of interpretations ( Stake, 2003 ). It is worth pointing out that this is not an option for studies that specifically seek the individual’s experience in relation to organizational phenomena.

In short, there are different ways of seeking rigor and quality in case studies, depending on the researcher’s worldview. These different forms pervade everything from the research design, the choice of research questions, the theory or theories to look at a phenomenon, research methods, the data collection and analysis techniques, to the type and style of research report produced. Validity can also take on different forms. While positivism is concerned with validity of the research question and results, interpretivism emphasizes research processes without neglecting the importance of the articulation of pertinent research questions and the sound interpretation of results ( Ollaik & Ziller, 2012 ). The means to achieve this can be diverse, such as triangulation (of multiple theories, multiple methods, multiple data sources or multiple investigators), pre-tests of data collection instrument, pilot case, study protocol, detailed description of procedures such as field diary in observations, researcher positioning (reflexivity), theoretical-empirical consistency, thick description and transferability.

5. Conclusions

The central objective of this article was to discuss concepts of case study research, their potential and various uses, taking into account different epistemologies as well as criteria of rigor and validity. Although the literature on methodology in general and on case studies in particular, is voluminous, it is not easy to relate this approach to epistemology. In addition, method manuals often focus on the details of various case study approaches which confuse things further.

Faced with this scenario, we have tried to address some central points in this debate and present various ways of using case studies according to the preferred epistemology of the researcher. We emphasize that this understanding depends on how a case is defined and the particular epistemological orientation that underpins that conceptualization. We have argued that whatever the epistemological orientation is, it is possible to meet appropriate criteria of research rigor and quality provided there is an alignment among the different elements of the research process. Furthermore, multiple data collection techniques can be used in in single or multiple case study designs. Data collection techniques or the type of data collected do not define the method or whether cases should be used for theory-building or theory-testing.

Finally, we encourage researchers to consider case study research as one way to foster immersion in phenomena and their contexts, stressing that the approach does not imply a commitment to a particular epistemology or type of research, such as qualitative or quantitative. Case study research allows for numerous possibilities, and should be celebrated for that diversity rather than pigeon-holed as a monolithic research method.

The interrelationship between the building blocks of research

Byrne , D. ( 2013 ). Case-based methods: Why We need them; what they are; how to do them . Byrne D. In D Byrne. and C.C Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbooks of Case-Based methods , pp. 1 – 10 . London : SAGE Publications Inc .

Creswell , J. W. ( 1998 ). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions , London : Sage Publications .

Coraiola , D. M. , Sander , J. A. , Maccali , N. & Bulgacov , S. ( 2013 ). Estudo de caso . In A. R. W. Takahashi , (Ed.), Pesquisa qualitativa em administração: Fundamentos, métodos e usos no Brasil , pp. 307 – 341 . São Paulo : Atlas .

Dyer , W. G. , & Wilkins , A. L. ( 1991 ). Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: a rejoinder to Eisenhardt . The Academy of Management Review , 16 , 613 – 627 .

Eisenhardt , K. ( 1989 ). Building theory from case study research . Academy of Management Review , 14 , 532 – 550 .

Eisenhardt , K. M. , & Graebner , M. E. ( 2007 ). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges . Academy of Management Journal , 50 , 25 – 32 .

Flyvbjerg , B. ( 2006 ). Five misunderstandings about case-study research . Qualitative Inquiry , 12 , 219 – 245 .

Freitas , J. S. , Ferreira , J. C. A. , Campos , A. A. R. , Melo , J. C. F. , Cheng , L. C. , & Gonçalves , C. A. ( 2017 ). Methodological roadmapping: a study of centering resonance analysis . RAUSP Management Journal , 53 , 459 – 475 .

Gibbert , M. , Ruigrok , W. , & Wicki , B. ( 2008 ). What passes as a rigorous case study? . Strategic Management Journal , 29 , 1465 – 1474 .

Gibbert , M. , & Ruigrok , W. ( 2010 ). The “what” and “how” of case study rigor: Three strategies based on published work . Organizational Research Methods , 13 , 710 – 737 .

Godoy , A. S. ( 1995 ). Introdução à pesquisa qualitativa e suas possibilidades . Revista de Administração de Empresas , 35 , 57 – 63 .

Grix , J. ( 2002 ). Introducing students to the generic terminology of social research . Politics , 22 , 175 – 186 .

Marsh , D. , & Furlong , P. ( 2002 ). A skin, not a sweater: ontology and epistemology in political science . In D Marsh. , & G Stoker , (Eds.), Theory and Methods in Political Science , New York, NY : Palgrave McMillan , pp. 17 – 41 .

McKeown , T. J. ( 1999 ). Case studies and the statistical worldview: Review of King, Keohane, and Verba’s designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research . International Organization , 53 , 161 – 190 .

Merriam , S. B. ( 2009 ). Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation .

Ollaik , L. G. , & Ziller , H. ( 2012 ). Distintas concepções de validade em pesquisas qualitativas . Educação e Pesquisa , 38 , 229 – 241 .

Picoli , F. R. , & Takahashi , A. R. W. ( 2016 ). Capacidade de absorção, aprendizagem organizacional e mecanismos de integração social . Revista de Administração Contemporânea , 20 , 1 – 20 .

Pozzebon , M. , & Freitas , H. M. R. ( 1998 ). Pela aplicabilidade: com um maior rigor científico – dos estudos de caso em sistemas de informação . Revista de Administração Contemporânea , 2 , 143 – 170 .

Sandberg , J. ( 2005 ). How do we justify knowledge produced within interpretive approaches? . Organizational Research Methods , 8 , 41 – 68 .

Seuring , S. A. ( 2008 ). Assessing the rigor of case study research in supply chain management. Supply chain management . Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , 13 , 128 – 137 .

Siggelkow , N. ( 2007 ). Persuasion with case studies . Academy of Management Journal , 50 , 20 – 24 .

Stake , R. E. ( 2003 ). Case studies . In N. K. , Denzin , & Y. S. , Lincoln (Eds.). Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry , London : Sage Publications . pp. 134 – 164 .

Takahashi , A. R. W. , & Semprebom , E. ( 2013 ). Resultados gerais e desafios . In A. R. W. , Takahashi (Ed.), Pesquisa qualitativa em administração: Fundamentos, métodos e usos no brasil , pp. 343 – 354 . São Paulo : Atlas .

Ragin , C. C. ( 1992 ). Introduction: Cases of “what is a case? . In H. S. , Becker , & C. C. Ragin and (Eds). What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry , pp. 1 – 18 .

Ragin , C. C. ( 2013 ). Reflections on casing and Case-Oriented research . In D , Byrne. , & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbooks of Case-Based methods , London : SAGE Publications , pp. 522 – 534 .

Yin , R. K. ( 2015 ). Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos , Porto Alegre : Bookman .

Zampier , M. A. , & Takahashi , A. R. W. ( 2014 ). Aprendizagem e competências empreendedoras: Estudo de casos de micro e pequenas empresas do setor educacional . RGO Revista Gestão Organizacional , 6 , 1 – 18 .

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: Both authors contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Short and sweet: multiple mini case studies as a form of rigorous case study research

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sebastian Käss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0640-3500 1 ,

- Christoph Brosig ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7809-0796 1 ,

- Markus Westner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6623-880X 2 &

- Susanne Strahringer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9465-9679 1

387 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Case study research is one of the most widely used research methods in Information Systems (IS). In recent years, an increasing number of publications have used case studies with few sources of evidence, such as single interviews per case. While there is much methodological guidance on rigorously conducting multiple case studies, it remains unclear how researchers can achieve an acceptable level of rigour for this emerging type of multiple case study with few sources of evidence, i.e., multiple mini case studies. In this context, we synthesise methodological guidance for multiple case study research from a cross-disciplinary perspective to develop an analytical framework. Furthermore, we calibrate this analytical framework to multiple mini case studies by reviewing previous IS publications that use multiple mini case studies to provide guidelines to conduct multiple mini case studies rigorously. We also offer a conceptual definition of multiple mini case studies, distinguish them from other research approaches, and position multiple mini case studies as a pragmatic and rigorous approach to research emerging and innovative phenomena in IS.

Similar content being viewed by others

The theory contribution of case study research designs

Case Study Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Case study research has become a widely used research method in Information Systems (IS) research (Palvia et al. 2015 ) that allows for a comprehensive analysis of a contemporary phenomenon in its real-world context (Dubé and Paré, 2003 ). This research method is particularly useful due to its flexibility in covering complex phenomena with multiple contextual variables, different types of evidence, and a wide range of analytical options (Voss et al. 2002 ; Yin 2018 ). Although case study research is particularly useful for studying contemporary phenomena, some researchers feel that it lacks rigour, particularly in terms of the validity of findings (Lee and Hubona 2009 ). In response to these criticisms, Yin ( 2018 ) provides comprehensive methodological steps to conduct case studies rigorously. In addition, many other publications with a partly discipline-specific view on case study research, offer guidelines for achieving rigour in case study research, e.g., Benbasat et al. ( 1987 ), Dubé and Paré ( 2003 ), Pan and Tan ( 2011 ), or Voss et al. ( 2002 ). Most publications on case study methodology converge on four criteria for ensuring rigour in case study research: (1) construct validity, (2) internal validity, (3) external validity, and (4) reliability (Gibbert et al. 2008 ; Voss et al. 2002 ; Yin 2018 ).

A key element of rigour in case study research is to look at the unit of analysis of a case from multiple perspectives in order to draw informed conclusions (Dubois and Gadde 2002 ). Case study researchers refer to this as triangulation, for example, by using multiple sources of evidence per case to support findings (Benbasat et al. 1987 ; Yin 2018 ). However, in our own research experience, we have come across numerous IS publications with a limited number of sources of evidence per case, such as a single interview per case. Some researchers refer to these studies as mini case studies (e.g., McBride 2009 ; Weill and Olson 1989 ), while others refer to them as multiple mini cases (e.g., Eisenhardt 1989 ). We were unable to find a definition or conceptualisation of this type of case study. Therefore, we will refer to this type of case study as a multiple mini case study (MMCS). Interestingly, many researchers use these MMCSs to study emerging and innovative phenomena.

From a methodological perspective, multiple case study publications with limited sources of evidence, also known as MMCSs, may face criticism for their lack of rigour (Dubé and Paré 2003 ). Alternatively, they may be referred to as “marginal case studies” (Piekkari et al. 2009 , p. 575) if they fail to establish a connection between theory and empirical evidence, provide only limited context, or merely offer illustrative aspects (Piekkari et al. 2009 ). IS scholars advocate conducting case study research in a mindful manner by balancing methodological blueprints and justified design choices (Keutel et al. 2014 ). Consequently, we propose MMCSs as a mindful approach with the potential for rigour, distinguishing them from marginal case studies. The following research question guides our study:

RQ: How can researchers rigorously conduct MMCSs in the IS discipline?

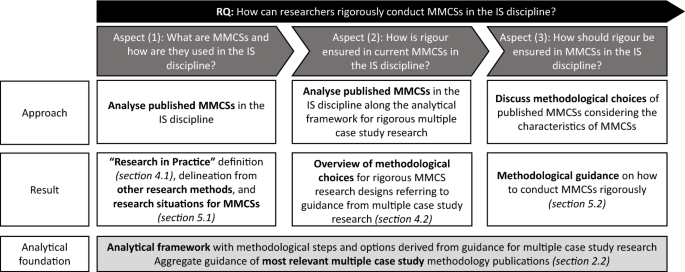

As shown in Fig. 1 , we develop an analytical framework by synthesising methodological guidance on how to rigorously conduct multiple case study research. We then address three aspects of our research question: For aspect (1), we analyse published MMCSs in the IS discipline to derive a "Research in Practice" definition of MMCSs and research situations for MMCSs. For aspect (2), we use the analytical framework to analyse how researchers in the IS discipline ensure that existing MMCSs follow a rigorous methodology. For aspect (3), we discuss the methodological findings about rigorous MMCSs in order to derive methodological guidelines for MMCSs that researchers in the IS discipline can follow.

Overview of the research approach

We approach these aspects by introducing the conceptual foundation for case study research in Sect. 2 . We define commonly accepted criteria for ensuring validity in case study research, introduce the concept of MMCSs, and distinguish them from other types of case studies. Furthermore, as a basis for analysis, we present an analytical framework of methodological steps and options for the rigorous conduct of multiple case study research. Section 3 presents our methodological approach to identifying published MMCSs in the IS discipline. In Sect. 4 , we first define MMCSs from a research in practice perspective (Sect. 4.1 ). Second, we present an overview of methodological options for rigorous MMCSs based on our analytical framework (Sect. 4.2 ). In Sect. 5 , we differentiate MMCSs from other research approaches, identify research situations of MMCSs (i.e., to study emerging and innovative phenomena), and provide guidance on how to ensure rigour in MMCSs. In our conclusion, we clarify the limitations of our study and provide an outlook for future research with MMCSs.

2 Conceptual foundation

2.1 case study research.

Case study research is about understanding phenomena by studying one or multiple cases in their context. Creswell and Poth ( 2016 ) define it as an “approach in which the investigator explores a bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection” (p. 73). Therefore, it is suitable for complex topics with little available knowledge, needing an in-depth investigation, or where the research subject is inseparable from its context (Paré 2004 ). Additionally, Yin ( 2018 ) states that case study research is useful if the research focuses on contemporary events where no control of behavioural events is required. Typically, this type of research is most suitable for how and why research questions (Yin 2018 ). Eventually, the inferences from case study research are based on analytic or logical generalisation (Yin 2018 ). Instead of drawing conclusions from a representative statistical sample towards the population, case study research builds on analytical findings from the observed cases (Dubois and Gadde 2002 ; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). Case studies can be descriptive, exploratory, or explanatory (Dubé and Paré 2003 ).

The contribution of research to theory can be divided into the steps of theory building , development and testing , which is a continuum (Ridder 2017 ; Welch et al. 2011 ), and case studies are useful at all stages (Ridder 2017 ). In theory building, there is no theory to explain a phenomenon, and the researcher identifies new concepts, constructs, and relationships based on the data (Ridder 2017 ). In theory development, a tentative theory already exists that is extended or refined (e.g., by adding new antecedents, moderators, mediators, and outcomes) (Ridder 2017 ). In theory testing, an existing theory is challenged through empirical investigation (Ridder 2017 ).

In case study research, there are different paradigms for obtaining research results, either positivist or interpretivist (Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Orlikowski and Baroudi 1991 ). The positivist paradigm assumes that a set of variables and relationships can be objectively identified by the researcher (Orlikowski and Baroudi 1991 ). In contrast, the interpretivist paradigm assumes that the results are inherently rooted in the researcher’s worldview (Orlikowski and Baroudi 1991 ). Nowadays, researchers find that there are similar numbers of positivist and interpretivist case studies in the IS discipline compared to almost 20 years ago when positivist research was perceived as dominant (Keutel et al. 2014 ; Klein and Myers 1999 ). As we aim to understand how to conduct MMCSs rigorously, we focus on methodological guidance for positivist case study research.

The literature proposes a four-phased approach to conducting a case study: (1) the definition of the research design, (2) the data collection, (3) the data analysis, and (4) the composition (Yin 2018 ). Table 1 provides an overview and explanation of the four phases.

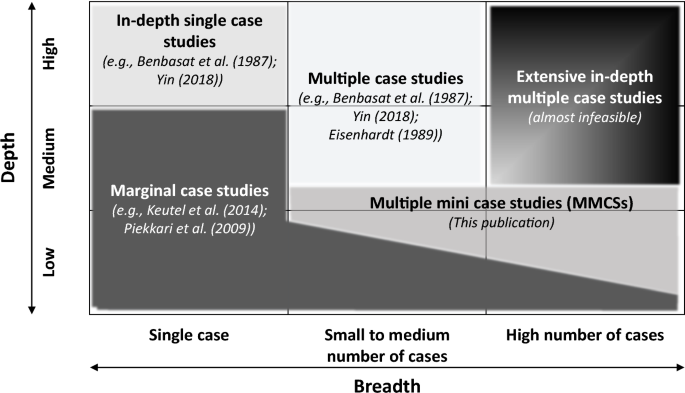

Case studies can be classified based on their depth and breadth, as shown in Fig. 2 . We can distinguish five types of case studies: in-depth single case studies , marginal case studies , multiple case studies , MMCSs , and extensive in-depth multiple case studies . Each type has distinct characteristics, yet the boundaries between the different types of case studies is blurred. Except for the marginal case studies, the italic references in Fig. 2 are well-established publications that define the respective type and provide methodological guidance. The shading is to visualise the different types of case studies. The italic references in Fig. 2 for marginal case studies refer to publications that conceptualise them.

Simplistic conceptualisation of MMCS

In-depth single case studies focus on a single bounded system as a case (Creswell and Poth 2016 ; Paré 2004 ; Yin 2018 ). According to the literature, a single case study should only be used if a case meets one or more of the following five characteristics: it is a critical, unusual, common, revelatory, or longitudinal case (Benbasat et al. 1987 ; Yin 2018 ). Single case studies are more often used for descriptive research (Dubé and Paré 2003 ).

A second type of case studies are marginal case studies , which generally have low depth (Keutel et al. 2014 ; Piekkari et al. 2009 ). Marginal case studies lack a clear link between theory and empirical evidence, a clear contextualisation of the case, and are often used for illustration purposes (Keutel et al. 2014 ; Piekkari et al. 2009 ). Therefore, marginal case studies provide only marginal insights with a lack of generalisability.

In contrast, multiple case studies employ multiple cases to obtain a broader picture of the researched phenomenon from different perspectives (Creswell and Poth 2016 ; Paré 2004 ; Yin 2018 ). These multiple case studies are often considered to provide more robust results due to the multiplicity of their insights (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). However, often discussed criticisms of multiple case studies are high costs, difficult access to multiple sources of evidence for each case, and long duration (Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Meredith 1998 ; Voss et al. 2002 ). Eisenhardt ( 1989 ) considers four to ten in-depth cases as a suitable number of cases for multiple case study research. With fewer than four cases, the empirical grounding is less convincing, and with more than ten cases, researchers quickly get overwhelmed by the complexity and volume of data (Eisenhardt 1989 ). Therefore, methodological literature views extensive in-depth multiple case studies as almost infeasible due to their high complexity and resource demands, which can easily overwhelm the research team and the readers (Stake 2013 ). Hence, we could not find a methodological publication outlining the approach for this case study type.

To solve the complexity and resource issues for multiple case studies, a new phenomenon has emerged: MMCS . An MMCS is a special type of multiple case study that focuses on an investigation's breadth by using a relatively high number of cases while having a somewhat limited depth per case. We characterise breadth not only by the number of cases but also by the variety of the cases. Even though there is no formal conceptualisation of the term, we understand MMCSs as a type of multiple case study research with few sources of evidence per case. Due to the limited depth per case, one can overcome the resource and complexity issues of classical multiple case studies. However, having only some sources of evidence per case may be considered a threat to rigour. Therefore, in this publication, we provide suggestions on how to address these threats.

2.2 Rigour in case study research

Rigour is essential for case study research (Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Yin 2018 ) and, in the early 2000s, researchers criticised case study research for inadequate rigour (e.g., Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Gibbert et al. 2008 ). Based on this, various methodological publications provide guidance for rigorous case study research (e.g., Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Gibbert et al. 2008 ).

Methodological literature proposes four criteria to ensure rigour in case study research: Construct validity , internal validity , external validity , and reliability (Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Gibbert et al. 2008 ; Yin 2018 ). Table 2 outlines these criteria and states in which research phase they should be addressed (Yin 2018 ). Methodological literature agrees that all four criteria must be met for rigorous case study research (Dubé and Paré 2003 ).

The methodological literature discusses multiple options for achieving rigour in case study research (e.g., Benbasat et al. 1987 ; Dubé and Paré 2003 ; Eisenhardt 1989 ; Yin 2018 ). We aggregated guidance from multiple sources by conducting a cross-disciplinary literature review to build our analytical foundation (cf. Fig. 1 ). This literature review aims to identify the most relevant multiple case study methodology publications from a cross-disciplinary and IS-specific perspective. We focus on the most cited methodology publications, while being aware that this may over-represent disciplines with a higher number of case study publications. However, this approach helps to capture an implicit consensus among case study researchers on how to conduct multiple case studies rigorously. The literature review produced an analytical framework of methodological steps and options for conducting multiple case studies rigorously. Appendix A Footnote 1 provides a detailed documentation of the literature review process. The analytical framework derived from the set of methodological publications is presented in Table 3 . We identified required and optional steps for each research stage. The analytical framework is the basis for the further analysis of MMCS and an explanation of all methodological steps is provided in Appendix B. Footnote 2

3 Research methodology

For our research, we analysed published MMCSs in the IS discipline with the goal of understanding how these publications ensured rigour. This section outlines the methodology of how we identified our MMCS publications.

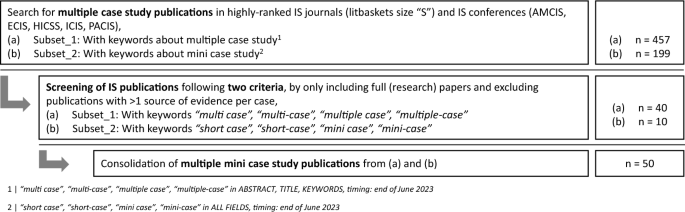

First, we searched bibliographic databases and citation indexing services (Vom Brocke et al. 2009 ; Vom Brocke et al. 2015 ) to retrieve IS-specific MMCSs (Hanelt et al. 2015 ). As shown in Fig. 3 , we used two sets of keywords, the first set focusing on multiple case studies and the second set explicitly on mini case studies. We decided to follow this approach as many MMCSs are positioned as multiple case studies, avoiding the connotation “mini” or “short”. We restricted our search to completed research publications written in English from litbaskets.io size “S”, a set of 29 highly ranked IS journals (Boell and Wang 2019 ) Footnote 3 and leading IS conference proceedings from AMCIS, ECIS, HICSS, ICIS, and PACIS (published until end of June 2023). We focused on these outlets, as they can be taken as a representative sample of high quality IS research (Gogan et al. 2014 ; Sørensen and Landau 2015 ).

The search process for published MMCSs in the IS discipline

Second, we screened the obtained set of IS publications to identify MMCSs. We only included publications with positivist multiple cases where the majority of cases was captured with only one primary source of evidence. Further, we excluded all publications which were interview studies rather than case studies (i.e., they do not have a clearly defined case). In some cases, it was unclear from the full text whether a publication fulfils this requirement. Therefore, we contacted the authors and clarified the research methodology with them. Eventually, our final set contained 50 publications using MMCSs.

For qualitative data analysis, we employed axial coding (Recker 2012 ) based on the pre-defined analytical framework shown in Table 3 . For the coding, we followed the explanations of the authors in the manuscripts. The coding was conducted and reviewed by two of the authors. We coded the first five publications of the set of IS MMCS publications together and discussed our decisions. After the initial coding was completed, we checked the reliability and validity by re-coding a sample of the other author’s set. In this sample, we achieved inter-coder reliability of 91% as a percent agreement in the decisions made (Nili et al. 2020 ). Hence, we consider our coding as highly consistent.

In the results section, we illustrate the chosen methodological steps for each MMCS type (descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory). For this purpose, we selected three publications based on two criteria: only journal publications, as they have more details about their methodological steps and publications which applied most of the analytical framework’s methodology steps. This led to three exemplary IS MMCS publications: (1) McBride ( 2009 ) for descriptive MMCSs, (2) Baker and Niederman ( 2014 ) for exploratory MMCSs, and (3) van de Weerd et al. ( 2016 ) for explanatory MMCSs.

4.1 MMCS from a “Research in Practice" perspective

In this section, we explain MMCSs from a "Research in Practice" perspective and identify different types based on our sample of 50 MMCS publications. As outlined in Sect. 2.1 , an MMCS is a special type of a multiple case study, which focuses on an investigation’s breadth by using a relatively high number of cases while having a limited depth per case. In the most extreme scenario, an MMCS only has one source of evidence per case. Moreover, breadth is not only characterised by the number of cases, but also by the variety of the cases. MMCSs have been used widely but hardly labelled as such, i.e., only 10 of our analysed 50 MMCS publications explicitly use the terms mini or short case in the manuscript . Multiple case study research distinguishes between descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory case studies (Dubé and Paré 2003 ). The MMCSs in our sample follow the same classification with three descriptive, 40 exploratory, and seven explanatory MMCSs. Descriptive and exploratory MMCSs are used in the early stages of research , and exploratory and explanatory MMCSs are used to corroborate findings .

Descriptive MMCSs provide little information on the methodological steps for the design, data collection, analysis, and presentation of results. They are used to illustrate novel phenomena and create research questions, not solutions, and can be useful for developing research agendas (e.g., McBride 2009 ; Weill and Olson 1989 ). The descriptive MMCS publications analysed contained between four to six cases, with an average of 4.6 cases per publication. Of the descriptive MMCSs analysed, one did not state research questions, one answered a how question and the third answered how and what questions. Descriptive MMCSs are illustrative and have a low depth per case, resulting in the highest risk of being considered a marginal case study.

Exploratory MMCSs are used to explore new phenomena quickly, generate first research results, and corroborate findings. Most of the analysed exploratory MMCSs answer what and how questions or combinations. However, six publications do not explicitly state a research question, and some MMCSs use why, which, or whether research questions. The analysed exploratory MMCSs have three to 27 cases, with an average of 10.2 cases per publication. An example of an exploratory MMCS is the study by Baker and Niederman ( 2014 ), who explore the impacts of strategic alignment during merger and acquisition (M&A) processes. They argue that previous research with multiple case studies (mostly with three cases) shows some commonalities, but much remains unclear due to the low number of cases. Moreover, they justify the limited depth of their research with the “proprietary and sensitive nature of the questions” (Baker and Niederman 2014 , p. 123).

Explanatory MMCSs use an a priori framework with a relatively high number of cases to find groups of cases that share similar characteristics. Most explanatory MMCSs answer how questions, yet some publications answer what, why, or combinations of the three questions. The analysed explanatory MMCSs have three to 18 cases, with an average of 7.2 cases per publication. An example of an explanatory MMCS publication is van de Weerd et al. ( 2016 ), who researched the influence of organisational factors on the adoption of Software as a Service (SaaS) in Indonesia.

4.2 Applied MMCS methodology in IS publications

4.2.1 overarching.

In the following sections, we present the results of our analysis. For this purpose, we mapped our 50 IS MMCS publications to the methodological options (Table 3 ) and present one example per MMCS type. We extended some methodological steps with options from methodology-in-use. A full coding table can be found in Appendix D Footnote 4 . Tables 4 , 5 , 6 and 7 summarise the absolute and percentual occurrences of each methodological option in descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory IS MMCS publications. All tables are structured in the same way and show the number of absolute and, in parentheses, the percentual occurrences of each methodological option. The percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. The bold numbers show the most common methodological option for each MMCS type and step. Most publications were classified in previously identified options. Some IS MMCS publications lacked detail on methodological steps, so we classified them as "step not evident". Only 16% (8 out of 50) explained how they addressed validity and reliability threats.

4.2.2 Research design phase

There are six methodological steps in the research design phase, as shown in Table 4 . Descriptive MMCSs usually define the research question (2 out of 3, 67%), clarify the unit of analysis (2 out of 3, 67%), bound the case (2 out of 3, 67%), or specify an a priori theoretical framework (2 out of 3, 67%). The case replication logic is mostly not evident (2 out of 3, 67%). Descriptive MMCS use a criterion-based selection (1 out of 3, 33%), a maximum variation selection (1 out of 3, 33%), or do not specify the selection logic (1 out of 3, 33%). Descriptive MMCSs have a high risk of becoming a marginal case study due to their illustrative nature–our chosen example is not different. McBride ( 2009 ) does not define the research question, does not have a priori theoretical framework, nor does he justify the case replication and the case selection logic. However, he clarifies the unit of analysis and extensively bounds each case with significant context about the case organisation and its setup.

The majority of exploratory MMCSs define the research question (34 out of 40, 85%) clarify the unit of analysis (35 out of 40, 88%), and specify an a priori theoretical framework (33 out of 40, 83%). However, only a minority (6 out of 40, 15%) follow the instructions of bounding the case or justify the case replication logic (13 out of 40, 33%). The most used case selection logic is the criterion-based selection (23 out of 40, 58%), followed by step not evident (5 out of 40, 13%), other selection approaches (3 of 40, 13%), maximum variation selection (3 out of 40, 13%), a combination of approaches (2 out of 40, 5%), snowball selection (2 out of 40, 5%), typical case selection (1 out of 40, 3%), and convenience-based selection (1 out of 40, 3%). Baker and Niederman ( 2014 ) build their exploratory MMCS on previous multiple case studies with three cases that showed ambiguous results. Hence, Baker and Niederman ( 2014 ) formulate three research objectives instead of defining a research question. They clearly define the unit of analysis (i.e., the integration of the IS function after M&A) but lack the bounding of the case. The authors use a rather complex a priori framework, leading to a high number of required cases. This a priori framework is also used for the “theoretical replication logic [to choose] conforming and disconfirming cases” (Baker and Niederman 2014 , p. 116). A combination of maximum variation and snowball selection is used to select the cases (Baker and Niederman 2014 ). The maximum variation is chosen to get evidence for all elements of their rather complex a priori framework (i.e., the breadth), and the snowball sampling is chosen to get more details for each framework element.

All explanatory MMCS s define the research question, clarify the unit of analysis, and specify an a priori theoretical framework. However, only one (14%) bounds the case. The case replication logic is mostly a mixture of theoretical and literal replication (3 out of 7, 43%) and one (14%) MMCS does a literal replication. For 43% (3 out of 7) of the publications, the step is not evident. Most explanatory MMCSs use criterion-based selection (4 out of 7, 57%), followed by maximum variation selection (2 out of 7, 29%) and snowball selection (1 out of 7, 14%). In their publication, van de Weerd et al. ( 2016 ) define the research question and clarify the unit of analysis (i.e., the influence of organisational factors on SaaS adoption in Indonesian SMEs). Further, they specify an a priori framework (i.e., based on organisational size, organisational readiness, and top management support) to target the research (van de Weerd et al. 2016 ). A combination of theoretical (between the groups of cases) and literal (within the groups of cases) replication was used. To strengthen the findings, van de Weerd et al. ( 2016 ) find at least one other literally replicated case for each theoretically replicated case.

To summarize this phase, we see that in all three types of MMCSs, the majority of publications define the research question, clarify the unit of analysis, and specify an a priori theoretical framework. Moreover, descriptive MMCSs are more likely to bound the case than exploratory and explanatory MMCSs. However, only a minority across all MMCSs justify the case replication logic, whereas the majority does not. Most MMCSs justify the case selection logic, with criterion-based case selection being the most often applied methodological option.

4.2.3 Data collection phase

In the data collection phase, there are four methodological steps, as summarised in Table 5 .