- DOCTORAL PROGRAMS

- Business Case for Emotional Intelligence

- Do Emotional Intelligence Programs Work?

- Emotional Competence Framework

- Emotional Intelligence: What it is and Why it Matters

- Executives' Emotional Intelligence (mis) Perceptions

- Guidelines for Best Practice

- Guidelines for Securing Organizational Support For EI

- Johnson & Johnson Leadership Study

- Ontario Principals’ Council Leadership Study

- Technical Report on Developing Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional Capital Report (ECR)

- Emotional Intelligence Quotient (EQ-i)

- Emotional & Social Competence Inventory 360 (ESCI)

- Emotional & Social Competence Inventory-University (ESCI-U)

- Geneva Emotional Competence Test

- Genos Emotional Intelligence Inventory (Genos EI)

- Team Emotional Intelligence (TEI)

- Mayer Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT)

- Profile of Emotional Competence (PEC)

- Schutte Self-Report Inventory (SSRI)

- Six Seconds Emotional Intelligence Assessment (SEI)

- Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue)

- Wong's Emotional Intelligence Scale

- Work Group Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP)

- Book Chapters

- Dissertations

- Achievement Motivation Training

- Care Giver Support Program

- Competency-Based Selection

- Emotional Competence Training - Financial Advisors

- Executive Coaching

- Human Relations Training

- Interaction Management

- Interpersonal Conflict Management - Law Enforcement

- Interpersonal Effectiveness Training - Medical Students

- JOBS Program

- Self-Management Training to Increase Job Attendance

- Stress Management Training

- Weatherhead MBA Program

- Williams' Lifeskills Program

- Article Reprints

NEW PODCAST SERIES - Working with Emotional Intelligence

Check out our new EVENTS section to find out about the latest conferences and training opportunities involving members of the EI Consortium.

NEW Doctoral Program in Organizational Psychology

Rutgers University - Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology (GSAPP) is now offering a doctoral program in Organizational Psychology and is accepting applications for students. The Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations is headquartered within Rutgers, providing students the opportunity to conduct research and collaborate with leading experts in the field of emotional intelligence. Click here for additional information.

NEW Research Fellowship

think2perform Research Institute’s Research Fellowship program invites proposals from doctoral candidates, post-docs and junior faculty pursuing self-defined research focused on moral intelligence, purpose, and/or emotional intelligence. Click here for more information.

Listen to Consortium member Chuck Wolfe interview some of the thought leaders in emotional intelligence.

Harvard Alumni Panel - Why is interest in Emotional Intelligence Soaring?

Consortium member Chuck Wolfe hosts a panel of world class leaders in the field of emotional intelligence (EI) to talk about why interest in EI is soaring. Panel members include EI Consortium members Dr. Richard Boyatzis , Dr. Cary Cherniss and Dr. Helen Riess . Click here to view the panel discussion.

Interview with Dr. Cary Cherniss and Dr. Cornelia Roche

Host, Chuck Wolfe interviews Drs. Cary Cherniss and Cornelia Roche about their new book Leading with Feeling: Nine Strategies of Emotionally Intelligent Leadership . The authors share powerful stories of cases involving outstanding leaders using strategies that can be learned that demonstrate effective use of emotional intelligence. Click here to see the interview.

Interview with Dr. Rick Aberman

See Chuck Wolfe interview Consortium member and sports psychologist Dr. Rick Aberman on peak performance and dealing with the pandemic. The interview is filled with insights, humorous anecdotes, and strategies for achieving peak performance in athletics and in life. Click here to see the interview.

Interview with Dr. David Caruso

Chuck Wolfe interviews Consortium member David Caruso talking about their work together, the ability model of emotional intelligence, and insights into how to use emotional intelligence to address staying emotionally and mentally healthy during times of crisis and uncertainty. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Richard Boyazis

How can you help someone to change? Richard Boyatzis is an expert in multiple areas including emotional intelligence. Richard and his coauthors, Melvin Smith, and Ellen Van Oosten , have discovered that helping people connect to their positive vision of themselves or an inspiring dream or goal they've long held is key to creating changes that last. In their book Helping People Change the authors share real stories and research that shows choosing a compassionate over a compliance coaching approach is a far more engaging and successful way to Helping People Change. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Marc Brackett

Marc Brackett , Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, has written a wonderful book about feelings. I worked with Marc when he was first crafting his world class social and emotional learning program, RULER. Our interview highlights how Marc has achieved his own and his Uncle's vision for encouraging each of us to understand and manage our feelings. My conversation with Marc is inspiring, humorous, and engaging at times. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Helen Riess

Helen Riess is a world class expert on empathy. She is an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Empathy and Relational Science Program at Mass General Hospital. Helen discusses her new book and shares insights, learnings and techniques such as the powerful seven-step process for understanding and increasing empathy. She relates information and cases whereby she uses empathy to make a meaningful difference in areas such as parenting and leading. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Maurice Elias

The show is about the Joys and Oys of Parenting , a book written by a respected colleague, Dr. Maurice Elias, an expert in parenting and emotional and social intelligence. Dr. Elias wrote a book tying Judaism and emotional intelligence together to help parents with the challenging, compelling task of raising emotionally healthy children. And while there are fascinating links to Judaism the book is really for everybody. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Geetu Bharwaney

Challenges abound and life is stressful for many. So how do we cope? Chuck Wolfe interviews Geetu Bharwaney about her book, Emotional Resilience . Geetu offers research, insights, and most importantly practical tips for helping people bounce back from adversity. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Daniel Goleman

Listen to an interview by with Dr. Goleman on his new book Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence . In the book Dan helps readers to understand the importance and power of the ability to focus one's attention, will power, and cognitive control in creating life success. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. John Mayer

How Personal Intelligence Shapes Our Lives: A Conversation with John D. Mayer. From picking a life partner, to choosing a career, Jack explains how personal intelligence has a major impact on our ability to make successful decisions. Click here to listen to the interview.

Interview with Dr. Cary Cherniss

Click HERE to listen to an interview with Dr. Cary Cherniss co-chair of the EI Consortium. Dr. Cherniss discusses the issue of emotional intelligence and workplace burnout.

Click HERE to listen to an interview with Dr. Marc Brackett , the newly appointed leader of the Center of Emotional Intelligence which will begin operation at Yale University in April, 2013. In this interview Dr. Brackett shares his vision for the new center.

EI Consortium Copyright Policy

Any written material on this web site can be copied and used in other sources as long as the user acknowledges the author of the material (if indicated on the web site) and indicates that the source of the material was the web site for the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations (www.eiconsortium.org).

Interact with CREIO

- CREIO on Facebook

- Subscribe to EI Newsletter

- Download Reports

- Model Programs

EI Assessments

- Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i)

- Emotional & Social Competence Inventory

- Emotional & Social Competence Inventory - University Edition

- Genos Emotional Intelligence Inventory

- Mayer-Salovey-Caruso EI Test (MSCEIT)

- Schutte Self Report EI Test

- Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire

- Work Group Emotional Intelligence Profile

© 2022 Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations Webmaster: Dr. Robert Emmerling Twitter: @RobEmmerling

Emotional Intelligence

3 takeaways from the latest emotional intelligence study, a new review paper shows the secrets to success of having a high eq..

Posted May 9, 2023 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- High emotional intelligence, or EQ, is considered an asset.

- A new review suggests that EQ is a skill that people can acquire to help promote career success.

- By developing adaptability and self-efficacy, we can gain the success that comes naturally to high-EQ people.

You’ve undoubtedly heard of the concept of “ emotional intelligence ,” or “EQ.” It took hold in the 1990s and has only continued to attract the attention of both everyday people and academic psychology. Claims about its contribution to success in life, announced even before its heyday, still remain somewhat controversial, however. In part, this is because the concept has become so blurry and all-encompassing that some of the original subtleties in its definition have since become long lost.

To understand whether EQ really matters for life success, it’s necessary to dig down deep into its original meaning and then take a clear-headed look at the available research. Fortunately, this is now possible due to the publication (in press) of a new major review article that does just that.

What Is Emotional Intelligence?

According to this new paper headed up by UCLouvain’s Thomas Pirsoul and colleagues (2023), this blurring of definitional lines is a major problem in evaluating EQ’s role in promoting life success. In their words, the “plethora of definitions and conceptualizations” can be categorized into two main areas: EQ as a trait-like quality or ability (personal resources approach) and EQ as a behavioral disposition that helps people feel better about their ability to navigate emotional situations ( self-efficacy approach).

From the standpoint of EQ’s role in promoting life success, the Belgian authors narrowed their search through the vast literature to studies specifically focused on career . If EQ helps promote career success, it would do so by “developing awareness of one’s emotions” (p. 3). Defined as a general form of adaptive functioning, EQ allows people to “identify, understand, express, regulate, and use one’s own and others’ emotions” (p. 2).

Think now about people you would consider high in EQ. Perhaps you know someone at work, or who works with someone you’re close to, whom you regard as not just friendly but also sensitive, kind, and willing to listen. You trust this individual to show consideration to you but also to make good choices in their own life. They seem confident but not conceited, and you’ve seen them progress through their career in ways that you admire. Importantly, they are liked both by coworkers and supervisors, meaning that their progress up their career ladder seems that it should be easier for them than is true for most people.

EQ and Job Success

The route from high EQ to career ladder progression, as the UCLouvain authors propose, is charted through the intermediary step of adaptability. As you no doubt know from your own life experiences, being adaptable means that you can anticipate problems and then cope with them once they arise. If you are high in EQ, you can use your emotions to guide yourself through these difficulties.

High self-efficacy can build upon the strengths gained through career adaptability by helping individuals feel more confident about their ability to navigate work-related decisions. If you can, as high EQ implies, listen to your “gut,” you’ll feel that you have a more accurate career compass.

Self-efficacy can also contribute to an individual’s confidence in their so-called “entrepreneurial” skills. The belief that you can sell yourself, which is part of this skill, can help you be a more effective communicator of your own personal strengths. You might also be better able to read people, making you a better negotiator. Finally, you could be better able to launch new ventures based on EQ’s role in helping you manage the stress associated with striking out on your own.

The ability to manage stress becomes its own contributor to occupational success for those high in EQ. There are many situations in work settings, from job interviews to performance evaluations, in which people have to exert effort as they try to keep their stress down to manageable levels.

In evaluating the contribution of all of these factors to career success, the authors contrasted two theoretical models. In the trait or resource model, EQ alone would be enough to predict the objective favorable career-related outcome of salary and the subjective outcomes of feelings of job and career satisfaction. If career adaptability and self-efficacy serve as the intermediary influences on these outcomes, then this would support a model in which factors involving these two components are statistically better predictors than EQ is on its own.

After extracting data from more than 150 samples representing nearly 51,000 participants, Pirsoul and his collaborators concluded that the behavioral, rather than the trait or resource model, proved to have the strongest relationship to measures of objective and subjective career success. Supporting what they call the “career self- management model,” these findings show that people high in EQ do well because they are higher in self-efficacy. Supporting the “career construction model,” the findings also showed that people high in EQ do well because they can adapt to their circumstances, and they can also make better career decisions.

One set of findings also provided intriguing support for the notion that people high in EQ are lower in career turnover intentions, meaning that they are less likely to decide to quit their jobs or abandon their careers. Their greater self-understanding means that they choose a pathway that will be consistent with their needs and interests. Their better emotional self-regulation could also make them less likely to have problems with their coworkers and supervisors, going back to the idea that people high in EQ are just nice to have around.

Supporting the idea that EQ can continue to grow in adulthood, as is evident from prior research, the effect sizes for EQ and career outcomes were stronger for older samples included in the meta-analysis. It is possible that as people gain greater self-understanding, their EQ growth is reflected in these career adaptability and self-efficacy dimensions.

3 Ways to Get EQ to Work for You

These three takeaways from this study suggest that EQ is more than just a popular idea without academic merit:

- People high in EQ do well in their careers, not just because they possess an overall higher level of knowledge about themselves but also because they know how to make good decisions and can approach work-related challenges with expectations that they can succeed. They also have greater internal self-awareness, allowing them to have a better idea of what they want out of their work lives. They can also negotiate with others more effectively, meaning that they are both better collaborators and also better strategists.

- The UCLouvain study focused on work and, therefore, wouldn’t have direct applicability to relationships or other areas of adult life. However, given the importance of satisfaction with and success in one’s work role, it would make sense that the EQ findings would have favorable implications for well-being in general. There is extensive evidence throughout the career–family literature showing that satisfaction at work is related positively to satisfaction with one’s home life.

- The final important conclusion of this study was the view that EQ isn’t a “thing” that you have or don’t have. Although high EQ may help improve an individual’s adaptability and self-efficacy, these latter two components of the Belgian model are behavioral in nature and, therefore, can be acquired.

To sum up, if you’re not naturally high in EQ, the Pirsoul et al. findings suggest that by using the skills that high-EQ individuals seem to have cultivated, you can find fulfilling outcomes in your most important life pursuits.

Pirsoul, T., Parmentier, M., Sovet, L., & Nils, F. (2023). Emotional intelligence and career-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Human Resource Management Review . doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2023.100967

Susan Krauss Whitbourne, Ph.D. , is a Professor Emerita of Psychological and Brain Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her latest book is The Search for Fulfillment.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Emotional Intelligence: What the Research Says

Measuring emotional intelligence, predictive value, what can schools do, choosing approaches, how might the ability curriculum work, emotional intelligence in schools.

Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 75 , 989–1015.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Schriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Epstein, S. (1998). Constructive thinking: The key to emotional intelligence . Westport, CT: Praeger.

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgement: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117 (1), 39–66.

Gibbs, N. (1995, October 2). The EQ factor. Time, 146 (14), 60–68.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence . New York: Bantam.

Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional intelligence: A new vision for educators [Videotape]. Port Chester, NY: National Professional Resources.

Goleman, D. (1998, November/ December). What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 76 , 93–102.

Joachim, K. (1996). The politics of self-esteem. American Educational Research Journal, 33 , 3–22.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets standards for a traditional intelligence. Intelligence, 27 , 267–298.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., Salovey, P., Formica, S., & Woolery, A. (2000). Unpublished raw data.

Mayer, J. D., & Cobb, C. D. (2000). Educational policy on emotional intelligence: Does it make sense? Educational Psychology Review, 12 (2), 163–183.

Mayer, J. D., DiPaolo, M. T., & Salovey, P. (1990). Perceiving affective content in ambiguous visual stimuli: A component of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54 , 772–781.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1993). The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence, 17 (4), 433–442.

Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). New York: BasicBooks.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 396–420). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newmann, F. M. (1987). Higher order thinking in the teaching of social studies: Connections between theory and practice . Madison, WI: National Center on Effective Secondary Schools. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 332 880)

Rhode Island Emotional Competency Partnership. (1998). Update on emotional competency . Providence, RI: Rhode Island Partners.

Rubin, M. M. (1999). Emotional intelligence and its role in mitigating aggression: A correlational study of the relationship between emotional intelligence and aggression in urban adolescents . Unpublished manuscript, Immaculata College, Immaculata, PA.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, & Personality, 9 (3), 185–211.

Trinidad, D. R., & Johnson, A. (2000). The association between emotional intelligence and early adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Unpublished manuscript, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Casey D. Cobb has contributed to Educational Leadership magazine.

John D. Mayer has contributed to Educational Leadership magazine.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., from our issue.

To process a transaction with a Purchase Order please send to [email protected]

- Side Hustles

- Power Players

- Young Success

- Save and Invest

- Become Debt-Free

- Land the Job

- Closing the Gap

- Science of Success

- Pop Culture and Media

- Psychology and Relationships

- Health and Wellness

- Real Estate

- Most Popular

Related Stories

- Psychology and Relationships Here's the No. 1 phrase I've seen 'destroy' relationships, says Harvard psychologist of 20 years

- Psychology and Relationships If you have a friend who uses any of these 8 toxic phrases, it may be time to 'move on': Psychologist

- Health and Wellness Harvard psychologist: If you can say 'yes' to these 9 questions, you're 'more emotionally secure than most'

- Raising Successful Kids I've studied over 200 kids—here are 6 things kids with high emotional intelligence do every day

- Leadership The No. 1 trait bosses look for when promoting employees: ex-CEO, Harvard expert

Harvard researcher says the most emotionally intelligent people have these 12 traits. Which do you have?

What makes someone great at their job? Having knowledge, smarts and vision, to be sure. But what really distinguishes the world's most successful leaders is emotional intelligence — or the ability to identify and monitor emotions (of their own and of others).

Companies today are increasingly looking through the lens of emotional intelligence when hiring, promoting and developing their employees. Years of studies show that the more emotional intelligence someone has, the better their performance.

What most people fail to realize, though, is that mastering emotional intelligence doesn't come naturally. Tom, for example, considers himself an emotionally intelligent person. He's a well-liked manager who is kind, respectful, nice to be around and sensitive to the needs of others.

And yet, he often wonders, I have all the qualities of emotional intelligence, so why do I still feel stuck in my career?

This is a common trap: Tom is defining emotional intelligence too narrowly. By focusing on his sociability and likability, he loses sight of all other essential emotional intelligence traits he may be lacking — ones that can make him a stronger, more effective leader.

After spending 25 years writing books and fostering research on this topic , I've found that emotional intelligence is comprised of four domains. And nested within these domains are 12 core competencies.

(Click here to enlarge chart)

Don't shortchange your development by assuming that emotional intelligence is all about being sweet and chipper. By reviewing the competencies below and doing an honest assessment of your strengths and weaknesses, you can better identify where there's room to grow.

1. Self-awareness

Self-awareness is the capacity to tune into your own emotions. It allows you to know what you are feeling and why, as well as how those feelings help or hurt what you're trying to do.

Do you have the core competency of self-awareness ?

- Emotional self-awareness : You understand your own strengths and limitations; you operate from competence and know when to rely on someone else on the team. You also have clarity on your values and sense of purpose, which allows you to be more decisive when setting a course of action.

Developing the skills:

Every moment is an opportunity to practice self-awareness. One of the biggest keys is to acknowledge your weaknesses. If you're struggling with something at work, for example, be honest about the skills you need to work on in order to succeed.

Be conscious of the situations and events in your life, too. During times of frustration, pinpoint the root and cause of your frustration. Think about any signals that accompany how you feel in that moment.

2. Self-management

Self-management is the ability to keep disruptive emotions and impulses under control. This is a powerful skill for leaders, especially during a crisis — because will people look to them for reassurance, and if their leader is calm, they can be, too.

What core competencies of self-management do you have?

- Emotional self-control : You stay calm under pressure and recover quickly from upsets. You know how to balance your feelings for the good of yourself and others, or for the good of a given task, mission or vision.

- Adaptability : This shows up as agility in the face of change and uncertainty. You're able to find new ways of dealing with fast-morphing challenges and can balance multiple demands at once.

- Achievement orientation : You strive to meet or exceed a standard of excellence. You genuinely appreciate feedback on your performance, and are constantly seeking ways to do things better.

- Positive outlook : You see the good in people, situations and events. This is an incredibly valuable competency, as it can build resilience and set the stage for innovation and opportunity.

During moments of distress, do not brood or panic. Take a deep breath and check in with your emotions. Instead of blowing up at people, let them know what's wrong and offer some solutions.

Accept that there will always be sudden changes and challenges in life. Try to understand the context of the given situation and adjust your strategy or priorities based on what is most important at the time.

3. Social awareness

Social awareness indicates accuracy in reading and interpreting other people's emotions, often through non-verbal cues. Socially aware leaders are able to relate to many different types of people, listen attentively and communicate effectively.

What core competencies of social awareness do you have?

- Empathy : You pay full attention to the other person and take time to understand what they are saying and how they are feeling. You always try to put yourself in other people's shoes in a meaningful way.

- Organizational awareness : You can easily read the emotional currents and dynamics within a group or organization. You can sometimes even predict how someone on your team or leaders of a company you do business with might react to certain situations, allowing you to approach situations strategically.

First and foremost, social awareness requires good listening skills. Do not talk over someone else or try to hijack the agenda. Ask questions and invite others to do the same.

Challenging your prejudices and discovering commonalities is also key. Practice putting yourself in other people's shoes. When we do this, we are often more sensitive to what that person is experiencing and are less likely to tease, judge or bully them.

4. Relationship management

Relationship management is an interpersonal skill set that allows one to act in ways that motivate, inspire and harmonize with others, while also maintaining important relationships.

Which core competencies of relationship management do you have?

- Influence : You're a natural leader who can gather support from others with relative ease, creating a group that is engaged, mobilized and ready to execute the tasks at hand.

- Coach and mentor : You foster the long-term learning by giving feedback and support. You put your points into persuasive and clear ways so that people are motivated as well as clear about expectations.

- Conflict management : You're comfortable dealing with disagreements between multiple sides and can bring simmering disputes into the open and find win-win solutions.

- Teamwork : You interact well as a group member and can work with others. You participate actively, share responsibility and rewards, and contribute to the capability of your team as a whole.

- Inspirational leadership : You inspire and guide others towards the overall vision. You always get the job done and bring out your team's best qualities along the way.

If you're a constantly negative person, you'll have a very difficult time managing long-term relationships. Instead of focusing on "the worst that can happen," try to see yourself as an agent of positive change.

Don't be afraid to go against the grain of conventional norms or take risks, either. These kinds of people ultimately leave the people they work with feeling inspired, motivated and connected.

Daniel Goleman is a psychologist and best-selling author of "Emotional Intelligence" and "Social Intelligence." His latest book is "What Makes a Leader: Why Emotional Intelligence Matters." Daniel received his PhD in psychology and personality development from Harvard University. His work has appeared in The New York Times and Harvard Business Review. Follow him on Twitter @DanielGolemanEI .

Don't miss:

- A psychologist shares the 7 biggest parenting mistakes that destroy kids' confidence and self-esteem

- 7 things mentally strong people always say, according to a psychotherapist

- Stop asking 'how are you?' Harvard researchers say this is what successful people do when making small talk

Check out: The best credit cards of 2020 1 could earn you over $1,000 in 5 years

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Emotional Intelligence: How We Perceive, Evaluate, Express, and Control Emotions

Is EQ more important than IQ?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Shereen Lehman, MS, is a healthcare journalist and fact checker. She has co-authored two books for the popular Dummies Series (as Shereen Jegtvig).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Shereen-Lehman-MS-1000-b8eb65ee2fd1437094f29996bd4f8baa.jpg)

Hinterhaus Productions / Getty Images

- How Do I Know If I'm Emotionally Intelligent?

- How It's Measured

Why Is Emotional Intelligence Useful?

- Ways to Practice

- Tips for Improving

Emotional intelligence (AKA EI or EQ for "emotional quotient") is the ability to perceive, interpret, demonstrate, control, evaluate, and use emotions to communicate with and relate to others effectively and constructively. This ability to express and control emotions is essential, but so is the ability to understand, interpret, and respond to the emotions of others. Some experts suggest that emotional intelligence is more important than IQ for success in life.

While being book-smart might help you pass tests, emotional intelligence prepares you for the real world by being aware of the feelings of others as well as your own feelings.

How Do I Know If I'm Emotionally Intelligent?

Some key signs and examples of emotional intelligence include:

- An ability to identify and describe what people are feeling

- An awareness of personal strengths and limitations

- Self-confidence and self-acceptance

- The ability to let go of mistakes

- An ability to accept and embrace change

- A strong sense of curiosity, particularly about other people

- Feelings of empathy and concern for others

- Showing sensitivity to the feelings of other people

- Accepting responsibility for mistakes

- The ability to manage emotions in difficult situations

How Is Emotional Intelligence Measured?

A number of different assessments have emerged to measure levels of emotional intelligence. Such tests generally fall into one of two types: self-report tests and ability tests.

Self-report tests are the most common because they are the easiest to administer and score. On such tests, respondents respond to questions or statements by rating their own behaviors. For example, on a statement such as "I often feel that I understand how others are feeling," a test-taker might describe the statement as disagree, somewhat disagree, agree, or strongly agree.

Ability tests, on the other hand, involve having people respond to situations and then assessing their skills. Such tests often require people to demonstrate their abilities, which are then rated by a third party.

If you are taking an emotional intelligence test administered by a mental health professional, here are two measures that might be used:

- Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) is an ability-based test that measures the four branches of Mayer and Salovey's EI model. Test-takers perform tasks designed to assess their ability to perceive, identify, understand, and manage emotions.

- Emotional and Social Competence Inventory (ESCI) is based on an older instrument known as the Self-Assessment Questionnaire and involves having people who know the individual offer ratings of that person’s abilities in several different emotional competencies. The test is designed to evaluate the social and emotional abilities that help distinguish people as strong leaders.

There are also plenty of more informal online resources, many of them free, to investigate your emotional intelligence.

What Are the 4 Components of Emotional Intelligence?

Researchers suggest that there are four different levels of emotional intelligence including emotional perception, the ability to reason using emotions, the ability to understand emotions, and the ability to manage emotions.

- Perceiving emotions : The first step in understanding emotions is to perceive them accurately. In many cases, this might involve understanding nonverbal signals such as body language and facial expressions.

- Reasoning with emotions : The next step involves using emotions to promote thinking and cognitive activity. Emotions help prioritize what we pay attention and react to; we respond emotionally to things that garner our attention.

- Understanding emotions : The emotions that we perceive can carry a wide variety of meanings. If someone is expressing angry emotions, the observer must interpret the cause of the person's anger and what it could mean. For example, if your boss is acting angry, it might mean that they are dissatisfied with your work, or it could be because they got a speeding ticket on their way to work that morning or that they've been fighting with their partner.

- Managing emotions : The ability to manage emotions effectively is a crucial part of emotional intelligence and the highest level. Regulating emotions and responding appropriately as well as responding to the emotions of others are all important aspects of emotional management.

Recognizing emotions - yours and theirs - can help you understand where others are coming from, the decisions they make, and how your own feelings can affect other people.

The four branches of this model are arranged by complexity with the more basic processes at the lower levels and the more advanced processes at the higher levels. For example, the lowest levels involve perceiving and expressing emotion, while higher levels require greater conscious involvement and involve regulating emotions.

Interest in teaching and learning social and emotional intelligence has grown in recent years. Social and emotional learning (SEL) programs have become a standard part of the curriculum for many schools.

The goal of these initiatives is not only to improve health and well-being but also to help students succeed academically and prevent bullying. There are many examples of how emotional intelligence can play a role in daily life.

Thinking Before Reacting

Emotionally intelligent people know that emotions can be powerful, but also temporary. When a highly charged emotional event happens, such as becoming angry with a co-worker, the emotionally intelligent response would be to take some time before responding.

This allows everyone to calm their emotions and think more rationally about all the factors surrounding the argument.

Greater Self-Awareness

Emotionally intelligent people are not only good at thinking about how other people might feel but they are also adept at understanding their own feelings. Self-awareness allows people to consider the many different factors that contribute to their emotions.

Empathy for Others

A large part of emotional intelligence is being able to think about and empathize with how other people are feeling. This often involves considering how you would respond if you were in the same situation.

People who have strong emotional intelligence are able to consider the perspectives, experiences, and emotions of other people and use this information to explain why people behave the way that they do.

How You Can Practice Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence can be used in many different ways in your daily life. Some different ways to practice emotional intelligence include:

- Being able to accept criticism and responsibility

- Being able to move on after making a mistake

- Being able to say no when you need to

- Being able to share your feelings with others

- Being able to solve problems in ways that work for everyone

- Having empathy for other people

- Having great listening skills

- Knowing why you do the things you do

- Not being judgemental of others

Emotional intelligence is essential for good interpersonal communication. Some experts believe that this ability is more important in determining life success than IQ alone. Fortunately, there are things that you can do to strengthen your own social and emotional intelligence.

Understanding emotions can be the key to better relationships, improved well-being, and stronger communication skills.

Press Play for Advice On How to Be Less Judgmental

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , shares how you can learn to be less judgmental. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Are There Downsides to Emotional Intelligence?

Having lower emotional intelligence skills can lead to a number of potential pitfalls that can affect multiple areas of life including work and relationships. People who have fewer emotional skills tend to get in more arguments, have lower quality relationships, and have poor emotional coping skills.

Being low on emotional intelligence can have a number of drawbacks, but having a very high level of emotional skills can also come with challenges. For example:

- Research suggests that people with high emotional intelligence may actually be less creative and innovative.

- Highly emotionally intelligent people may have a hard time delivering negative feedback for fear of hurting other people's feelings.

- Research has found that high EQ can sometimes be used for manipulative and deceptive purposes.

Can I Boost My Emotional Intelligence?

While some people might come by their emotional skills naturally, some evidence suggests that this is an ability you can develop and improve. For example, a 2019 randomized controlled trial found that emotional intelligence training could improve emotional abilities in workplace settings.

Being emotionally intelligent is important, but what steps can you take to improve your own social and emotional skills? Here are some tips.

If you want to understand what other people are feeling, the first step is to pay attention. Take the time to listen to what people are trying to tell you, both verbally and non-verbally. Body language can carry a great deal of meaning. When you sense that someone is feeling a certain way, consider the different factors that might be contributing to that emotion.

Picking up on emotions is critical, but we also need to be able to put ourselves into someone else's shoes in order to truly understand their point of view. Practice empathizing with other people. Imagine how you would feel in their situation. Such activities can help us build an emotional understanding of a specific situation as well as develop stronger emotional skills in the long-term.

The ability to reason with emotions is an important part of emotional intelligence. Consider how your own emotions influence your decisions and behaviors. When you are thinking about how other people respond, assess the role that their emotions play.

Why is this person feeling this way? Are there any unseen factors that might be contributing to these feelings? How to your emotions differ from theirs? As you explore such questions, you may find that it becomes easier to understand the role that emotions play in how people think and behave.

Drigas AS, Papoutsi C. A new layered model on emotional intelligence . Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(5):45. doi:10.3390/bs8050045

Salovey P, Mayer J. Emotional Intelligence . Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 1990;9(3):185-211.

Feist GJ. A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity . Pers Soc Psychol Rev . 1998;2(4):290-309. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0204_5

Côté S, Decelles KA, Mccarthy JM, Van kleef GA, Hideg I. The Jekyll and Hyde of emotional intelligence: emotion-regulation knowledge facilitates both prosocial and interpersonally deviant behavior . Psychol Sci . 2011;22(8):1073-80. doi:10.1177/0956797611416251

Gilar-Corbi R, Pozo-Rico T, Sánchez B, Castejón JL. Can emotional intelligence be improved? A randomized experimental study of a business-oriented EI training program for senior managers . PLoS One . 2019;14(10):e0224254. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224254

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Please enter a keyword and click the arrow to search the site

Or explore one of the areas below

- Executive MBA

- Executive Education

- Masters Degrees

- Faculty and Research

- Academic research

Emotional intelligence, moral reasoning and transformational leadership

Leadership and Organization Development Journal

Organisational Behaviour

Publishing details

Leadership and Organization Development Journal 2002:23 p 198-204

Authors / Editors

Sivanathan N;Fekken G C

Biographies

Niro Sivanathan

Publication Year

Available on ECCH

Select up to 4 programmes to compare

Sign up to receive our latest news and business thinking direct to your inbox

Sign up to receive our latest course information and business thinking

Leave your details above if you would like to receive emails containing the latest thought leadership, invitations to events and news about courses that could enhance your career. If you would prefer not to receive our emails, you can still access the case study by clicking the button below. You can opt-out of receiving our emails at any time by visiting: https://london.edu/my-profile-preferences or by unsubscribing through the link provided in our emails. View our Privacy Policy for more information on your rights.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Can emotional intelligence be improved? A randomized experimental study of a business-oriented EI training program for senior managers

Raquel gilar-corbi.

Developmental and Educational Psychology Department, University of Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante, Spain

Teresa Pozo-Rico

Bárbara sánchez, juan-luís castejón, associated data.

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Purpose: This article presents the results of a training program in emotional intelligence. Design/methodology/approach: Emotional Intelligence (EI) involves two important competencies: (1) the ability to recognize feelings and emotions in oneself and others, and (2) the ability to use that information to resolve conflicts and problems to improve interactions with others. We provided a 30-hour Training Course on Emotional Intelligence (TCEI) for 54 senior managers of a private company. A pretest-posttest design with a control group was adopted. Findings: EI assessed using mixed and ability-based measures can be improved after training. Originality/value: The study’s results revealed that EI can be improved within business environments. Results and implications of including EI training in professional development plans for private organizations are discussed.

Introduction

This research study focused on EI training in business environments. Accordingly, the aim of the study was to examine the effectiveness of an original EI training program in improving the EI of senior managers. In this article, we delineate the principles and methodology of an EI training program that was conducted to improve the EI of senior managers of a private company The article begins with a brief introduction to the main models of EI that are embedded with the existing scientific literature. This is followed by a description of the EI training program that was conducted in the present study and presentation of results about its effectiveness in improving EI. Finally, the present findings are discussed in relation to the existing empirical literature, and the limitations and conclusions of the present study are articulated.

Defining EI

Various models of emotional intelligence (EI) have been proposed. The existing scientific literature offers three main models of EI: mixed, ability, and trait models. First, mixed models conceptualize EI as a combination of emotional skills and personality dimensions such as assertiveness and optimism [ 1 , 2 ]. Thus, according to the Bar-On model [ 3 ], emotional-social intelligence (ESI) is a multifactorial set of competencies, skills, and facilitators that determine how people express and understand themselves, understand and relate to others, and respond to daily situations The construct of ESI consists of 10 key components (i.e., self-regard, interpersonal relationships, impulse control, problem solving, emotional self-awareness, flexibility, reality-testing, stress tolerance, assertiveness, and empathy) and five facilitators (optimism, self-actualization, happiness, independence, and social responsibility). Emotionally and socially intelligent people accept and understand their emotions; they are also capable of expressing themselves assertively, being empathetic, cooperating with and relating to others in an appropriate manner, managing stressful situations and changes successfully, solving personal and interpersonal problems effectively, and having an optimistic perspective toward life. Second, ability models of EI focus on the processing of information and related abilities [ 3 ]. Accordingly, Mayer and Salovey [ 4 ] have conceptualized EI as a type of social intelligence that entails the ability to manage and understand one’s own and others’ emotions. Indeed, this implies that EI also entails the ability to use emotional information to manage thoughts and actions in an adaptive manner [ 5 ]. Third, the trait EI approach understands EI as emotion-related information [ 6 ]. According to trait models, EI refers to self-perceptions and dispositions that can be incorporated into fundamental taxonomies of personality. Therefore, according to Petrides and Furnham [ 7 ], trait EI is partially determined by several dimensions of personality and can be situated within the lower levels of personality hierarchies. However, it is a distinct construct that can be differentiated from other personality constructs. In addition, the construct of trait EI includes various personality dispositions as well as the self-perceived aspects of social intelligence, personal intelligence, and ability EI. The following facets are subsumed by the construct of trait EI: adaptability, assertiveness, emotion perception (self and others), emotion expression, management (others), and regulation, impulsiveness (low), relationships, self-esteem, self-motivation, social awareness, stress management, trait empathy, happiness, and optimism [ 7 ]. Finally, as Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] have indicated, most existing definitions of EI permit us to draw the conclusion that EI is a measurable individual characteristic that refers to a way of experiencing and processing emotions and emotional information. It is noteworthy that these models are not mutually exclusive [ 7 ].

Effects of EI on different outcomes

EI has been found to be related to workplace performance in highly demanding work environments (see e.g. [ 9 ]). Consequently, companies, entities, and organizations tend to recognize the importance of EI, promote it on a daily basis to facilitate career growth, and recruit those who possess this ability. [ 10 ].

With regard to research that has examined the EI-performance link, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran [ 11 ] conducted a metanalytic study to examine the predictive power of EI in the workplace. They found that approximately 5% of the variance in workplace performance was explained by EI, and this percentage is adequately significant to increase savings and promote improvements within organizations. In addition, the authors concluded that further in-depth investigations are needed to comprehensively understand the construct of EI.

However, the EI-performance link must be interpreted with caution. Specifically, Joseph and Newman [ 12 ] examined emotional competence in the workplace and found that EI predicts performance among those with high emotional labor jobs but not their counterparts with low emotional labor jobs. In addition, they indicated that further research is required to delineate the relationship between EI and actual job performance, gender and race differences in EI, and the utility of different types of EI measures that are based on ability or mixed models in training and selection. Accordingly, Pérez-González and Qualter [ 13 ] have underscored the need for emotional education. Further, Brasseur et al. [ 14 ] found that better job performance is related to EI, especially among those with jobs for which interpersonal contact is very important.

It is noteworthy that EI is positively related to job satisfaction. Accordingly, Chiva and Alegre [ 15 ] found that there was an indirect positive relationship between self-reported EI (i.e., as per mixed models) and job satisfaction. A total of 157 workers from several companies participated in this study. These findings suggest that people with higher levels of EI are more satisfied with their jobs and demonstrate a greater capacity for learning than their counterparts with lower levels of EI.

Similarly, Sener, Demirel, and Sarlak [ 16 ] adopted a mixed model of EI and examine its effect on job satisfaction. They found that individuals with strong emotional and social competencies demonstrated greater self-control. A total of 80 workers participated in this study. They were able to manage and understand their own and others’ emotions in an intelligent and adaptive manner in their personal and professional lives.

In addition, EI (i.e., as per mixed models) predicts job success because it influences one’s ability to deal with environmental demands and pressures [ 17 ]. Therefore, it has been contended that several components of EI (i.e., as per mixed models) contribute to success and productivity in the workplace [ 18 ]; future research studies should extend this line of inquiry. Several studies have shown that people with high levels of ability EI communicate in an interesting and assertive manner, which in turn makes others feel more comfortable in the workplace [ 19 ]. In addition, it has been contended that EI (i.e., as per mixed models) plays a valuable role in group development because effective teamwork occurs when team members possess knowledge about the strengths and weaknesses of others and the ability to use these strengths when necessary [ 15 , 20 ]. It is especially important for senior managers to demonstrate high levels of EI because they play a predominant role in team management, leadership, and organizational development.

Finally, studies that have examined the relationship between EI and wellbeing have found that ability EI is a predictor of professional success, wellbeing, and socially relevant outcomes [ 21 – 23 ]. Extending this line of inquiry, Slaski and Cartwright [ 24 ] investigated the relationship between EI and the quality of working life among middle managers and found that higher levels of EI is related to better performance, health, and wellbeing.

EI and leadership

The actions of organizational leaders play a crucial role in modulating the emotional experiences of employees [ 25 ]. Accordingly, Thiel, Connelly, and Griffith [ 26 ] found that, within the workplace, emotions affect critical cognitive tasks including information processing and decision making. In addition, the authors have contended that leadership plays a key role in helping subordinates manage their emotions. In another study, Batool [ 27 ] found that the EI of leaders have a positive impact on the stress management, motivation, and productivity of employees.

Gardner and Stough [ 28 ] further investigated the relationship between leadership and EI among senior managers and found that leaders’ management of positive and negative emotions had a beneficial impact on motivation, optimism, innovation, and problem resolution in the workplace. Therefore, the EI of directors and managers is expected to be positively correlated with employees’ work motivation and achievement.

Additionally, EI competencies are involved in the following activities: choosing organizational objectives, planning and organizing work activities, maintaining cooperative interpersonal relationships, and receiving the support that is necessary to achieve organizational goals [ 29 ]. In this regard, some authors have provided compelling theoretical arguments in favor of the existence of a relationship between EI and leadership [ 30 – 34 ]. In this way, several researches [ 30 – 34 ] show that EI is a core and key variable positively related to effective and transformational leadership and this is important for positive effects on job performance and attitudes that are desirable in the organization.

Further, people with high levels of EI are more capable of regulating their emotions to reduce work stress [ 35 ]; thus, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of EI in order to meet the workplace challenges of the 21st century.

In conclusion, EI competencies are considered to be key qualities that individuals who occupy management positions must possess [ 36 ]. Further, EI transcends managerial hierarchies when an organization flourishes [ 37 ]. Finally, emotionally intelligent managers tend to create a positive work environment that improves the job satisfaction of employees [ 38 ].

EI trainings

Past studies have shown that training improves the EI of students [ 22 , 39 , 40 – 44 ], employees [ 45 – 47 ], and managers [ 48 – 52 ]. More specifically, within the academic context, Nelis et al. [ 22 ] found that group-based EI training significantly improved emotion identification and management skills. In another study, Nelis et al. [ 39 ] found that EI training significantly improved emotion regulation and comprehension and general emotional skills. It also had a positive impact on psychological wellbeing, subjective perceptions of health, quality of social relations, and employability. Similarly, several studies that have been conducted within the workplace have shown that EI can be improved through training [ 45 – 52 ] and have underscored the key role that it plays in effective performance [ 53 , 54 ].

In addition, two relevant metanalyses [ 8 , 55 ] concluded that there has been an increase in research interest in EI, recognition of its influence on various aspects of people’s lives, and the number of interventions that aim to improve EI. Relatedly, Kotsou et al. [ 55 ] and Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] reviewed the findings of past studies that have examined the effects of EI training to explore whether such training programs do indeed improve EI.

First, Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] concluded that EI training has a moderate effect on EI and that interventions that are based on ability models of EI have the largest effects. In addition, the improvements that had resulted from these interventions were found to have been temporally sustained.

Second, the conclusions of Kotsou et al.’s [ 55 ] systematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of EI training make it evident that more rigorous and controlled studies are needed to permit one to draw concrete conclusions about whether training improves ability EI. Studies that had adopted mixed models of EI tended to more consistently find that training improves EI. Accordingly, the results of Kotsou et al.’s [ 55 ] metanalytic study revealed that EI training enhances teamwork, conflict management, employability, job satisfaction, and work performance.

Finally, it is necessary to identify and address the limitations of past interventions in future studies to improve their quality and effectiveness.

Purpose of the study

In the systematic review conducted by Kotsou et al. [ 55 ] regarding research published on interventions to improve EI in adults, one out of five studies with managers, was performed on a sample of middle managers, without randomization, with an inactive control group, no immediate measures after the training, and only one evaluation was performed six months after the training. In the other four studies collected in Kotsou et al.’s systematic review [ 55 ], only one study utilized a control group (inactive control group), one employed randomizations, and two studies performed follow-up measures six months after the intervention.

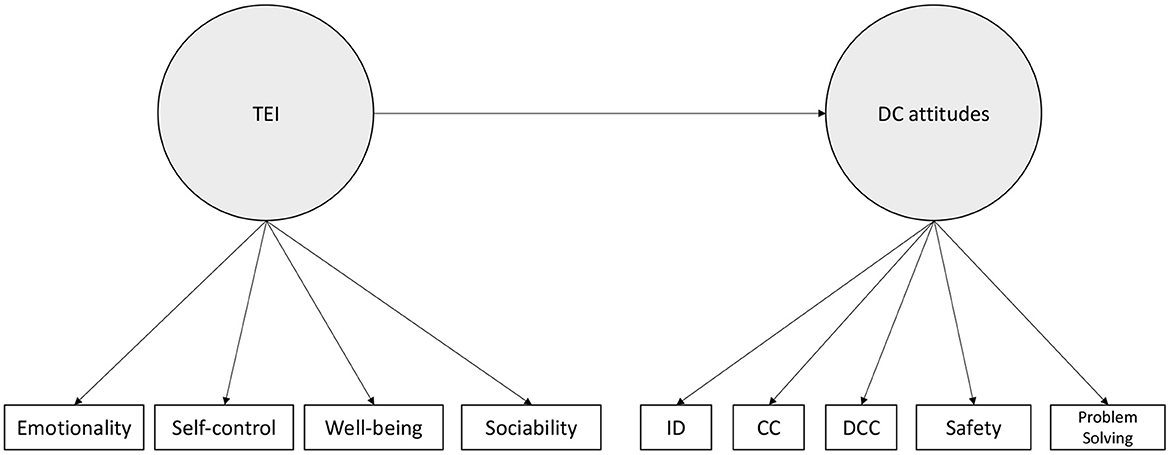

The two metanalyses confirmed and identified some problems or gaps we have tried to overcome in the present study. For this reason, in our study, we propose to deepen the assessment of EI training for senior managers, aiming to overcome most of the limitations mentioned in the studies of Kotsou et al. [ 55 ] and Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] by implementing the following: 1) Include a control group (waiting list group); 2) Conduct follow-up measurements (12 months later); 3) Employ an experimental design; 3) Include a workshop approach with group discussions and interactive participation; 4) Identify specific individual differences (i.e., age, gender) that might determine the effects of interventions; and 5) Use self-report and ability measures. For these reasons, two different ways of evaluating EI have been selected in this study to assess the emotional competencies applied within the labor and business world to solve practical problems: the EQ-i questionnaire [ 2 ], based on mixed models to provide a self-perceived index of EI, and the Situational Test of Emotional Management (STEM) and the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) [ 56 ] based on the ability model. Thus, including two different EI measure we aim at obtaining a more reliable validation of the intervention used.

Therefore, the objective of our study was to investigate whether EI can be improved among employees who occupy senior management positions in a private company. Thus, the research hypothesis was that participation in the designed program would improve EI among senior managers.

EI training development

The Course on Emotional Intelligence (TCEI) was created to provide senior managers with emotional knowledge and practical emotional skills so that they can apply and transfer their new understanding to teamwork and find solutions to real company problems and challenges. In this way, TCEI prepares workers to use the emotional learning resources appropriate to each work situation. In addition, TCEI combines face-to-face work sessions with a cross-sectional training through an e-learning platform. For more details, see S1 Appendix 1.

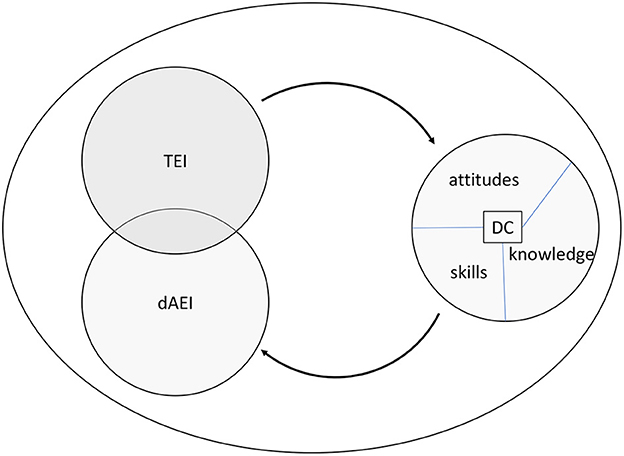

According to Mikolajczak [ 57 ], three interrelated levels of emotional intelligence can be differentiated: a) conceptual-declarative emotion knowledge, b) emotion-related abilities, and c) emotion-related dispositions. The TCEI aims at developing emotional skills, which are included on the second level of Mikolajczak’s model. Moreover, the present study uses the mixed model and the ability model measures to assess the level of EI. In using these measures, it is possible to assess the second level of Mikolajczak’s model. Pérez-González and Qualter [ 13 ] also suggest that activities related to ability EI should be included in emotional education programs.

Thus, this EI program was designed to allow senior managers to make use of their understanding and management of emotions as a strategy to assist them in facing the challenges within their work environment and managing their workgroups. Following the recommendation of Pérez-Gonzáles and Qualter, the training intervention methodology is founded in DAPHnE key practices [ 13 ]. It is important to emphasize that this training is grounded in practicality since it works based on the resolution of real cases, utilizing participative teaching-learning techniques and cooperative learning, while promoting the transfer of all aspects of EI and applied to various situations that can occur in the workplace. The e-learning system in the Moodle platform also provides an added value since it allows the creation of an environment providing exposure to professional experiences and continuous training. This type of pedagogical approach based on skills training and mediated through e-learning is a methodology that emerged in the 1990s when business organizations sought to create environments better suited to improving the management of large groups of employees. After its success, it began to be used in other contexts, including higher education and organizational development [ 58 – 60 ].

Finally, in order to justify the chosen training, it is important to note that the following official competencies for senior managers have been designated by the company:

- Supervise the staff and guarantee optimum employee performance by fostering a motivational working environment where employees receive the appropriate support and respect and their initiatives are given the consideration they deserve.

- Make decisions and promote clear goals, efficient leadership, competitive compensation, and acknowledgment of the employees’ achievements.

- Justify their decisions to executives and directors, explaining how they have ensured training by creating opportunities for appropriate professional development for all employees and how they have facilitated conditions for a better balance in achieving the company’s objectives.

In conclusion, considering the above-mentioned professional competencies required, senior managers were selected as participants in this study since they need to possess and apply aspects related to EI in order to accomplish their leadership and staff management responsibilities.

Participants

The company participating in this study was an international company with almost 175 years of history that occupies a select position in a branch of industry in the natural gas value chain, from the source of supply to market, including supply, liquefaction, shipping, regasification, and distribution. The company is present in over 30 countries around the world.

This study was conducted involving a sample of 54 senior managers selected from a company in a European country. The sample was extracted from the entire population of senior managers within this company following a stratified random sampling procedure, taking into account the gender of the population in order to select 50% of each gender.

The mean age of participants was 37.61 years (standard deviation = 8.55) and the percentage of female senior managers was 50%. For evaluation purposes, these employees were randomly divided into two groups: the experimental group ( n = 26; mean age = 35.57 (7.54); 50% women) and the control group ( n = 28; mean age = 39.50 (9.11); 50% women). The control group received EI training after the last data collection.

Initially, a group of senior managers from the company was selected to participate in the study, as they are employees who need a special domain of EI due to the competencies assigned to their professional category. In all cases, informed consent was requested for their participation in the study.

Assignment of participants to each condition, experimental or control, was performed using a random-number program. In addition, to avoid the Hawthorne effect, participants were not told if they were assigned to the experimental or control group; only their consent to participate in research on the development of EI was asked. Participants from the control group completed the same evaluations as the training group but were not exposed to the training.

The scales were administered during the pretest phase (Time 1) on an online platform for the experimental and control groups. On average, approximately 90 minutes were needed to complete the tests.

After the data were collected in the pre-test phase, only the experimental group participated in the TCEI over seven weeks, and they received a diploma.

Later, the scales were administered during the posttest phase (Time 2). Similarly, we collected the same data one year later (Time 3). A lapse of one year was allowed to pass because all training programs carried out in this company are re-evaluated one year later to determine whether improvements in employees’ skills were maintained over time. In fact, this demonstrates a clear commitment to monitoring the results achieved. Other studies have also used reevaluations of their results. For example, according to Nelis et al. [ 22 ] and Nelis et al. [ 39 ], the purpose of their studies was to evaluate whether trait EI could be improved and if these changes remained. To accomplish this, the authors performed three assessments: prior to the intervention, at the end of the intervention, and six months later. Therefore, as recommended by Kirkpatrick [ 61 ], research on the effectiveness of training should also include a long-term assessment of skills transfer.

Finally, is important to remark that all participants were properly informed of the investigation, and their written consent was obtained. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and the study was approved by University of Alicante Ethics Committee (UA-2015-07-06) and carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

As mentioned before, two different ways of defining and evaluating EI were selected for this study: (1) EQ-i, based on mixed models, and (2) the STEM/STEU questionnaires, based on the ability model of EI.

- 1 The Emotional Quotient Inventory [ 2 ]

To measure EI based on the mixed models, the short version of the EQ-i was used, which comprises 51 self-referencing statements and requires subjects to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). An example item is the following; “In handling situations that arise, I try to think of as many approaches as I can.” The EQ-i comprises five factors: Intrapersonal EI and Self-Perception, Interpersonal EI, Adaptability and Decision Making, General Mood and Self-Expression, Stress Management, and a Total EQ-i score, which serves as a global EI measure. The author of this instrument reports a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .69 to .86 for the 5 subscales [ 2 , 62 ] and the Cronbach’s alpha of the Emotional Quotient Inventory was .80 for the present sample of senior manager.

- 2 Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) and Situational Test of Emotion Management (STEM) [ 63 ]

Two tests were used to measure EI based on the ability model. Emotion understanding was evaluated by the short version of the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) [ 63 ]. This test is composed of 25 items that present an emotional situation (decontextualized, workplace-related, or private-life-related). For each item, participants have to choose which emotion will most likely elicit the described situation. Cronbach’s alpha of STEU is .83 [ 63 ] and the Cronbach’s alpha of the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding was .86 for the present sample of senior manager. An example item is the following: “An unwanted situation becomes less likely or stops altogether. The person involved is most likely to feel: (a) regret, (b) hope, (c) joy, (d) sadness, (e) relief” (in this case, the correct answer is “relief”).

On the other hand, emotion management was evaluated by the short version of the Situational Test of Emotion Management (STEM) [ 63 ]. This test is composed of a 20-item situational judgment test (SJT) that uses hypothetical behavioral scenarios followed by a set of possible responses to the situation. Respondents must choose which option they would most likely select in a “real” situation. Cronbach’s alpha of STEM is .68 [ 63 ] and the Cronbach’s alpha of the Situational Test of Emotion Management was .84 for the present sample of senior manager. An example item is the following: “Pete has specific skills that his workmates do not, and he feels that his workload is higher because of it. What action would be the most effective for Pete? (a) Speak to his boss about this; (b) Start looking for a new job; (c) Be very proud of his unique skills; (d) Speak to his workmates about this.”

TCEI content and organization

The program schedule spanned seven weeks with a face-to-face session of 95 minutes each week, which was delivered by one of the researchers specifically trained for this purpose. All the experimental group participants were taught together in these sessions. The content of each session was the following:

1st Session : Introduction. The objectives and methodology of the training were explained to participants.

2nd Session : Intrapersonal EI and self-perception. Trainees learned to identify their own emotions.

3rd Session : Interpersonal EI. Participants learned to identify others’ emotions.

4th Session : Adaptability and decision making. The objective was to improve trainees’ ability to identify and understand the impact that their own feelings can have on thoughts, decisions, behavior, and work performance resulting in better decisions and workplace adaptability.

5th Session : General mood and self-expression. Trainees worked on expressing their emotions and improving their skills to effectively control their mood.

6th Session : Stress management. Participants learned EI skills to manage stress effectively.

7th Session : Emotional understanding and emotion management. Trainees learned skills to effectively manage their emotions as well as skills that influence the moods and emotions of others.

In addition, access to the virtual environment (Moodle platform) was required after each face-to-face session. The time spent in the platform was registered, with a minimum of five hours required per week.

The virtual environment allowed the researcher to review all the content completed in each face-to-face session.

All of the EI abilities included in the virtual part of the training have been previously used in the face-to-face part; thus, virtual training is simply a method used to consolidate EI knowledge. In fact, the virtual environment has the same function as completing a workbook about the information presented during the face-to-face session. However, the added advantage of working in an e-learning environment is that all of the trainers are connected and can share their tasks and progress with others. At times, in addition to reviewing the contents of the previous session, the e-learning environment also introduces some important terms for the next session utilizing the principles of the well-known flipped classroom methodology. In short, the following activities were carried out through the Moodle platform to consolidate the participants’ knowledge:

1st Session: Participants were informed that e-learning would be part of the training in order to consolidate EI knowledge.

2nd Session: Participants explored the skills of Intrapersonal EI and self-perception in the virtual environment through discussion forums.

3rd Session: Participants learned the skills of identifying others’ emotions and utilizing this emotional information for decision-making. This information was summarized in the virtual environment through discussion forums.

4th Session: Participants sharpened their skills of adaptability and decision-making through the production of innovative ideas and the utilization of critical thinking skills in assessing the impact that their own feelings can have on others’ work performance. Trainees learned how to express their own emotions, as well as the skill of effectively controlling their mood, through the resolution of practical cases in the virtual environment; in these cases, innovative ideas and critical thinking skills were required in order to make better decisions during emotionally impactful; situations. In addition, trainees utilized the forum to reflect on why their own emotional regulation is important for ensuring long-term workplace adaptability.

5th Session: Verbal quiz, discussion, and forum contribution. Trainees participated in an online debate about key emotional skills in order to understand how to apply them in a real work environment. In particular, the debate focused on regulating the self-expression skill and equilibrating the general mood when there are difficult situations within the company. In this way, the participants identified the skills required to effectively manage the stress experienced in order to maintain a positive mood A discussion about common stressful situations at work was carried out in the virtual environment, and strategies for regulating the mood during critical work situations were shared.

6th Session: Discussion of ideas related to EI. Trainees participated in an online debate about key emotional skills in order to understand how to apply stress management skills to the real work environment. It was necessary to share previous work experiences where stress was a significant challenge and reevaluate the emotionally intelligent way to deter stress and maintain a balanced senior manager life.

7th Session: Participants concluded the training on target strategies to effectively manage their emotions as well as skills that influence the moods and emotions of others. This session, therefore, was a period for feedback where brief answers to specific doubts were provided. In addition, the outcomes of the training were established by the participants. Finally, senior managers were encouraged to stay connected through the Moodle platform in order to resolve future challenges together using the EI skills learned and internalized during the training period.

Data analysis