Cultural India

A Brief History of the British East India Company

Between early 1600s and the mid-19th century, the British East India Company lead the establishment and expansion of international trade to Asia and subsequently leading to economic and political domination of the entire Indian subcontinent. It all started when the East India Company, or the “ Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies ”, as it was originally named, obtained a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I, granting it “monopoly at the trade with the East”. A joint stock company, shares owned primarily by British merchants and aristocrats, the East India Company had no direct link to the British government.

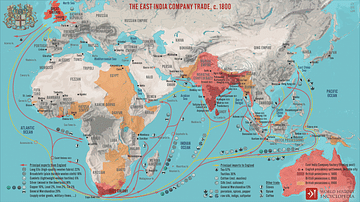

Through the mid-1700s and early 1800s, the company came to account for half of the world’s trade. They traded mainly in commodities exotic to Europe and Britain like cotton, indigo, salt, silk, saltpetre, opium and tea. Although initial interest of the company was aimed simply at reaping profits, their single minded focus on establishing a trading monopoly throughout Asia pacific, made them the heralding agents of British Colonial Imperialism. For the first 150 years the East India Company’s presence was largely confined to the coastal areas. It soon began to transform from a trading company to a ruling endeavor following their victory in the Battle of Plassey against the ruler of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daullah in the year 1757. Warren Hastings, the first governor-general, laid down the administrative foundations for the subsequent British consolidation. The revenues from Bengal were used for economic and military enrichment of the Company. Under directives from Governor Generals, Wellesly and Hastings, expansion of British territory by invasion or alliances was initiated, with the Company eventually acquiring major parts of present day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. In 1857, the Indians raised their voice against the Company and its oppressive rule by breaking out into an armed rebellion, which historians termed as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 . Although the company took brutal action to regain control, it lost much of its credibility and economic image back home in England. The Company lost its powers following the Government of India Act of 1858. The Company armed forces, territories and possessions were taken over by the Crown. The East India Company was formally dissolved by the Act of Parliament in 1874 which marked the commencement of the British Raj in India.

Founding of the Company

The British East India Company was formed to claim their share in the East Indian spice trade. The British were motivated the by the immense wealth of the ships that made the trip there, and back from the East. The East India Company was granted the Royal Charter on 31 December, 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I. The charter conceded the Company monopoly of all English trade in lands washed by the Indian Ocean (from the southern African peninsula, to Indonesian islands in South East Asia). British corporations unauthorized by the company treading the sea in these areas were termed interlopers and upon identification, they were liable to forfeiture of ships and cargo. The company was owned entirely by the stockholders and managed by a governor with a board of 24 directors.

Coat of Arms for the English East India Company

Image Credit : alfa-img.com http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Coat_of_arms_of_the_East_India_Company.svg/2000px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_East_India_Company.svg.png

Early Voyages

The first voyage of the company left in February 1601, under the commandership of Sir James Lanchaster, and headed for Indonesia to bring back pepper and fine spices. The four ships had a horrendous journey reaching Bantam, in Java in 1602, left behind a small group of merchants and assistants and returned back to England in 1603.

The second voyage was commandeered by Sir Henry Middleton. The third voyage was undertaken between 1607 and 1610, with General William Keeling aboard the Red Dragon, Captain William Hawkins aboard the Hector and the Captain David Middleton directing the Consent.

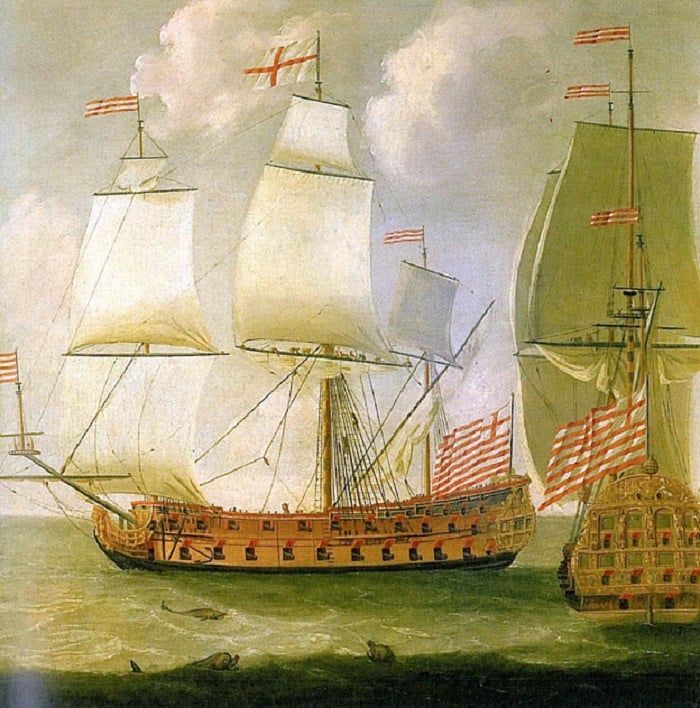

East India Company Ships, 1685

Image Credit : britishempire.co.uk http://www.britishempire.co.uk/images4/eastindiacompanyshipslarge.jpg

Establishment of Foothold in India

The Company’s ships first arrived in India, at the port of Surat, in 1608. In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe reached the court of the Mughal Emperor, Nuruddin Salim Jahangir (1605–1627) as the emissary of King James I, to arrange for a commercial treaty and gained for the British the right to establish a factory at Surat. A treaty was signed with the British promising the Mughal emperor “all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace” in return of his generous patronage.

Trading interest soon collided with establishments from other European countries like Spain, Portugal, France and Netherlands. The British East India Company soon found itself engaged in constant conflicts over trading monopoly in India, China and South East Asia with its European counterparts.

After the Amboina Massacre in 1623, the British found themselves practically ousted from Indonesia (then known as The Dutch East Indies). Losing horribly to the Dutch, the Company abandoned all hopes of trading out of Indonesia, and concentrated instead on India, a territory they previously considered as a consolation prize.

Under the secure blanket of Imperial patronage, the British gradually out-competed the Portuguese trading endeavor, Estado da India , and over the years oversaw a massive expansion of trading operations in India. The British Company’s win over the Portuguese in a maritime battle off the coast of India (1612) won them the much desired trading concessions from the Mughal Empire. In 1611 its first factories were established in India in Surat followed by acquisition of Madras (Chennai) in 1639, Bombay in 1668, and Calcutta in 1690. The Portuguese bases at Goa, Bombay and Chittagong were ceded to the British authorities as the dowry of Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705), Queen consort of Charles II of England. Numerous trading posts were established along the east and west coasts of India, and most conspicuous of English establishment developed around Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras, the three most important trading ports. Each of these three provinces was roughly equidistant from each other along the Indian peninsular coastline, and allowed the East India Company to commandeer a monopoly of trade routes more effectively over the Indian Ocean. The company started steady trade in cotton, silk, indigo, saltpeter, and an array of spices from South India. In 1711, the company established its permanent trading post in Canton province of China, and started trading of tea in exchange for silver. By the end of 1715, in a bid to expand trading activities, the Company had established solid trade footings in ports around the Persian Gulf, Southeast and East Asia.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal

Image Credit : mapstoryblog.thenittygritty.org http://mapstoryblog.thenittygritty.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2000.jpg

Towards Complete Monopoly

In 1694, the House of Commons voted “that all the subjects of England had an equal right to trade to the East Indies unless prohibited by act of Parliament.” Under pressure from wealthy influential tradesmen not associated with the Company. Following this the English Company Trading to the East Indies was founded with a state-backed indemnity of £2 million. To maintain financial control over the new company, existing stockholders of the old company paid a hefty sum of £315,000. The new company could hardly make a dent in the established old company markets. The new company was ultimately absorbed by the old East India Company in 1708. A tripartite venture was established between the state, the old and the new trading companies under the banner of United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies . The following few decades saw a bitter tug of war between the company lobby and the British Parliament to acquire permanent establishment rights which the latter was hesitant to relinquish in view of the immense profits the company brought. The united company lent to the government an additional £1,200,000 without interest in exchange of renewal of charter until1726. In 1730, the charter was renewed until 1766, in exchange of the East India Company lowering the interests on the remaining debt amount by one percent, and contributed another £200,000 to the Royal treasury. In 1743, they loaned the government another £1,000,000 at 3% interest, and the government prolonged the charter until 1783. Effectively, the company bought monopoly of trading in the East Indies by bribing the Government. At every juncture when this monopoly was expiring, it could only affect a renewal of its Charter by offering fresh loans and by fresh presents to the Government.

The French were late to enter the Indian trading markets and consequently entered into fresh rivalry with the British. By the 1740s rivalry between the British and the French was becoming acute. The Seven Years war between 1756 and 1763 effectively stumped out the French threat led by Governor General Robert Clive. This set up the basis of Colonial monopoly of East India Company in India. By the 1750s, the Mughal Empire was in a state of decadence. The Mughals, threatened by the British fortifying Calcutta, attacked them. Although the Mughals were able to acquire a victory in that face-off in 1756, their victory was short-lived. The British recaptured Calcutta later that same year. The East India Company forces went onto defeat the local royal representatives at the battle of Plassey in 1757 and at Buxar in 1764. Following the Battle of Buxar in 1764 , the Mughal emperor signed a treaty with the Company allowing them to oversee the administration of the province of Bengal, in exchange for a revised revenue amount every year. Thus began the metamorphosis of a mere trading concern to a colonial authority. The East India Company became responsible for administering the civil, judicial and revenue systems in one of India’s richest provinces. The arrangements made in Bengal provided the company direct administrative control over a region, and subsequently led to 200 years of Colonial supremacy and control.

Regulation of the Company’s Affairs

Throughout the next century, the East India Company continued to annex territory after territory until most of the Indian subcontinent was effectively under their control. From the 1760s onward, the government of Britain pulled the reins of the Company more and more, in an attempt to root out corruption and abuse of power.

As a direct repercussion of the military actions of Robert Clive, the Regulating Act of 1773 was enacted which prohibited people in the civil or military establishments from receiving any gift, reward, or financial assistance from Indians. This Act directed the promotion of the Governor of Bengal, to the rank of Governor General over the entire Company-controlled India. It also provided that nomination of Governor General, though made by a court of directors, would be subject to the approval of the Crown in conjunction with a council of four leaders (appointed by the Crown), in future. A Supreme Court was established in India. The justices were appointed by the Crown to be sent out to India.

William Pitt’s India Act (1784) established government authority over political policy making which needed to be approved through a Parliamentary regulatory board. It imposed the Board of Control, a body of six commissioners, above the Company Directors in London, consisting of the Chancellor of the Exchequer and a Secretary of State for India, together with the four councilors appointed by the Crown.

In 1813 the Company’s monopoly of the Indian trade was abolished, and, under the 1833 Charter Act , it lost its China trade monopoly as well. In 1854, the British Government in England ruled for the appointment of a Lieutenant-Governor to oversee regions of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha and the Governor General was directed to govern the entire Indian Colony. The Company continued its administrative functions until the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857.

Takeover of the Company by the British Crown

The brutal and rapid annexation of native Indian states by introduction of unscrupulous policies like the Doctrine of lapse or on the grounds of inability to pay taxes along with forcible renunciation of titles sparked widespread discontent among the country’s nobility. Moreover, tactless efforts at social and religious reforms contributed to spread of discomfiture among the common people. The sorry state of Indian soldiers and their mistreatment compared to their British counterparts in the armed forces of the Company provided the final push towards the first real rebellion against the Company’s governance in 1857.Known as the Sepoy Mutiny, what began as soldiers protest soon took epic proportions when disgruntled royalties joined forces. The British forces were able to curb the rebels with some effort, but the munity resulted in major loss of face for the Company and advertised its inability to successfully govern the colony of India. In 1858, the Crown enacted the Government of India Act , and assumed all governmental responsibilities held by the company. They also incorporated the Company owned military force into the British Army. The East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act was brought in effect on January 1, 1874 and the East India Company was dissolved in its entirety.

Half Anna coins during the East India Company rule in India

Image Credit : indiacoin.wordpress.com https://indiacoin.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/1845.jpg

Legacy of the East India Company

Although the East India Company’s colonial rule was hugely detrimental to the interest of the common people due to the exploitative nature of governance and tax implementation, there is no denying the fact that it brought forward some interesting positive outcomes as well.

One of the most impactful of them was a complete overhaul of the Justice System and establishment of the Supreme Court. Next big important impact was the introduction of postal system and telegraphy which the Company arguably established for its own benefit in 1837. The East Indian Railway Company was awarded the contracts to construct a 120-mile railway from Howrah-Calcutta to Raniganj in 1849. The transport system in India saw improvements in leaps and bounds with the completion of a 21-mile rail-line from Bombay to Thane, the first-leg of the Bombay-Kalyan line, in 1853.

Artist’s impression of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857

Image Credit : factsninfo.com http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-pfaSUdfpdus/VYzg12YpB0I/AAAAAAAAA1E/D2yozS213S8/s640/The_Relief_of_Lucknow.jpg

The British also brought forth social reforms by abolishing immoral indigenous practices through acts like the Bengal Sati Regulation in 1829 prohibiting immolation of widows, the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856 , enabling adolescent Hindu widows to remarry and not live a life of unfair austerity. Establishment of several colleges in the principal presidencies of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras was undertaken by the Company governance. These institutions contributed towards enriching young minds bringing to them a taste of world literature, philosophy and science. The educational reforms also included encouragement of native citizens to sit for the civil services exams and absorbing them into the service consequently.

The Company is popularly associated with unfair exploitation of its colonies and widespread corruption. The humongous amounts of taxes levied on agriculture and business led to man-made famines such as the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and subsequent famines during the 18th and 19th centuries. Forceful cultivation of opium and unfair treatment of indigo farmers lead to much discontent resulting in widespread militant protests.

The positive aspects of social, education and communication advancements were overshadowed largely by the plundering attitude of the Company rule stripping its dominions bare for profit.

Recent Posts

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How the East India Company Became the World’s Most Powerful Monopoly

By: Dave Roos

Updated: June 29, 2023 | Original: October 23, 2020

One of the biggest, most dominant corporations in history operated long before the emergence of tech giants like Apple or Google or Amazon. The English East India Company was incorporated by royal charter on December 31, 1600 and went on to act as a part-trade organization, part-nation-state and reap vast profits from overseas trade with India, China, Persia and Indonesia for more than two centuries. Its business flooded England with affordable tea, cotton textiles and spices, and richly rewarded its London investors with returns as high as 30 percent.

“At its peak, the English East India Company was by far the largest corporation of its kind,” says Emily Erikson, a sociology professor at Yale University and author of Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company . “It was also larger than several nations. It was essentially the de facto emperor of large portions of India, which was one of the most productive economies in the world at that point.”

But just when the East India Company’s grip on trade weakened in the late 18th century, it found a new calling as an empire-builder. At one point, this mega corporation commanded a private army of 260,000 soldiers, twice the size of the standing British army. That kind of manpower was more than enough to scare off the remaining competition, conquer territory and coerce Indian rulers into one-sided contracts that granted the Company lucrative taxation powers.

Without the East India Company, there would be no imperial British Raj in India in the 19th and 20th centuries. And the wild success of the world’s first multinational corporation helped shape the modern global economy, for better or worse.

East India Company Founded Under Queen Elizabeth I

On the very last day of 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted a charter to a group of London merchants for exclusive overseas trading rights with the East Indies, a massive swath of the globe extending from Africa’s Cape of Good Hope eastward to Cape Horn in South America. The new English East India Company was a monopoly in the sense that no other British subjects could legally trade in that territory, but it faced stiff competition from the Spanish and Portuguese, who already had trading outposts in India, and also the Dutch East Indies Company, founded in 1602.

England, like the rest of Western Europe, had an appetite for exotic Eastern goods like spices, textiles and jewelry. But sea voyages to the East Indies were tremendously risky ventures that included armed clashes with rival traders and deadly diseases like scurvy. The mortality rate for an employee of the East India Company was a shocking 30 percent, says Erikson. The monopoly granted by the royal charter at least protected the London merchants against domestic competition while also guaranteeing a kickback for the Crown, which was in desperate need of funds.

Many of the hallmarks of the modern corporation were first popularized by the East India Company. For example, the Company was the largest and longest-lasting joint stock company of its day, which means that it raised and pooled capital by selling shares to the public. It was governed by a president, but also a “board of control” or “board of officers.” Unlike today’s relatively staid corporate board meetings, the East India Company’s meetings were raucous affairs attended by hundreds of stockholders.

And while the East India Company charter granted it an ostensible monopoly in India, the Company also allowed its employees to engage in private trading on the side. At first, the Company didn’t have a lot of money to pay its employees for this highly dangerous work, so it needed to provide other incentives.

“That incentive was to trade for their own private interest overseas,” says Erikson. “Employees of the East India Company would trade both within and outside of the rules that the Company granted. There were so many opportunities to fudge, cheat and smuggle. Think about jewelry, which is a very small and very expensive thing that you can hide on yourself easily.”

East Indies Trade Fueled Consumer Culture

Before the East India Company, most clothes in England were made out of wool and designed for durability, not fashion. But that began to change as British markets were flooded with inexpensive, beautifully woven cotton textiles from India, where each region of the country produced cloth in different colors and patterns. When a new pattern arrived, it would suddenly become all the rage on the streets of London.

“There’s this possibility of being ‘in the right style’ that hadn’t existed before,” says Erikson. “A lot of historians think this is the beginning of consumer culture in England. Once they brought over the cotton goods, it introduced this new volatility in what was popular.”

In India, Trade and Politics Blend

When the British and other European traders arrived in India, they had to curry favor with local rulers and kings, including the powerful Mughul Empire that extended across India. Even though the East India Company was technically a private venture, its royal charter and battle-ready employees gave it political weight. Indian rulers invited local Company bosses to court, extracted bribes from them, and recruited the Company’s muscle in regional warfare, sometimes against French or Dutch trading companies.

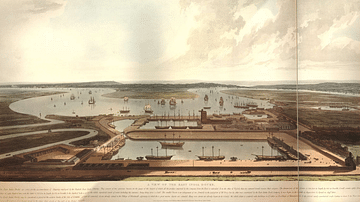

The Mughul Empire concentrated its power in the interior of India, leaving coastal cities more open to foreign influence. From the start, one of the reasons the East India Company needed so much pooled capital was to capture and build fortified trading outposts in port cities like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. When the Mughul Empire collapsed in the 18th century, war broke out in the interior, driving more Indian merchants to these company-run coastal “mini kingdoms.”

“The problem was, how would the East India Company rule these territories and by what principle?” says Tirthankar Roy, a professor of economic history at the London School of Economics and author of The East India Company: The World’s Most Powerful Corporation . “A company is not a state. A company ruling in the name of the Crown cannot happen without the Crown’s consent. Sovereignty became a big problem. In whose name will the company devise laws?”

The answer, in most cases, was the East India Company’s local branch officer. The London office of the company didn’t concern itself with Indian politics. Roy says that as long as trade continued, the Board was happy and didn’t interfere. Since there was very little communication between London and the branch offices (a letter took three months each way) it was left to the branch officer to write the laws governing company cities like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta, and to create local police forces and justice systems.

This would be the equivalent of Exxon Mobil drilling for oil in coastal Mexico, taking over a major Mexican city using private armed guards, and then electing a corporate middle manager as the mayor, judge and executioner.

From Mercantile Company to Empire Building

A major turning point in the East India Company’s transformation from a profitable trading company into a full-fledged empire came after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. The battle pitted 50,000 Indian soldiers under the Nawab of Bengal against just 3,000 Company men. The Nawab was angry with the Company for skirting taxes. But what the Nawab didn’t know was that the East India Company’s military leader in Bengal, Robert Clive, had struck a backroom deal with Indian bankers so that most of the Indian army refused to fight at Plassey.

Clive’s victory gave the East India Company broad taxation powers in Bengal, then one of the richest provinces in India. Clive plundered the Nawab’s treasure and shipped it back to London (keeping plenty for himself, of course). Erikson sees the East India Company’s actions in Bengal as a seismic shift in its corporate mission.

“This completely changes the Company’s business model from one that had been focused on profitable trade to one that focused on tax collection,” says Erikson. “That’s when it became a really damaging institution, in my opinion.”

In 1784, the British Parliament passed Prime Minister William Pitt’s “India Act,” which formally included the British government in ruling over the East India Company’s land holdings in India.

“When this act came into being, the Company ceased to be a very significant trade power or a significant governing power in India,” says Roy. “The proper British Empire took hold.”

The Opium Wars and the End of the East India Company

The exploits of the East India Company didn’t end in India. In one of its darkest chapters, the Company smuggled opium into China in exchange for the country’s most prized trade good: tea. China only traded tea for silver, but that was hard to come by in England, so the Company flouted China’s opium ban through a black market of Indian opium growers and smugglers. As tea flowed into London, the Company’s investors grew rich and millions of Chinese men wasted away in opium dens.

When China cracked down on the opium trade, the British government sent warships, triggering the Opium War of 1840. The humiliating Chinese defeat handed the British control of Hong Kong , but the conflict shed further light on the East India Company’s dark dealings in the name of profit.

By the mid-19th century, opposition to the East India Company’s monopoly status reached a fever pitch in Parliament fueled by the free-market arguments of Adam Smith. Erikson says that ultimately, the death of the East India Company in the 1870s was less about moral outrage over corporate corruption (of which there was plenty), but more about English politicians and businessmen realizing that they could make even more money trading with partners who were on a stronger economic footing, not captive patrons of a corporate state.

Even though the East India Company dissolved more than a century ago, its influence as a ruthless corporate pioneer has shaped the way modern business is conducted in a global economy.

“It’s hard to understand the global political structure without understanding the role of the Company,” says Erikson. “I don’t think we’d have a global capitalist economic system that looks the way it does if England hadn’t become so uniquely powerful at this point in history. They transitioned into a modern industrial force and exported their vision of production and governance to the rest of the world, including North America. It’s the cornerstone of the modern liberal global political order.”

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The East India Company: how a trading corporation became an imperial ruler

The East India Company was founded during the rule of Queen Elizabeth I and grew into a dominating global player with its own army, with huge influence and power. Writing for History Extra , Professor Andrea Major gives an insight into one of history's most powerful companies, and its rise to political power on the Indian subcontinent…

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

In 1600, a group of London merchants led by Sir Thomas Smythe petitioned Queen Elizabeth I to grant them a royal charter to trade with the countries of the eastern hemisphere. And so, the ‘Honourable Company of Merchants of London Trading with the East Indies’ – or East India Company, as it came to be known – was founded. Few could have predicted the seismic shifts in the dynamics of global trade that would follow, nor that 258 years later, the company would pass control of a subcontinent to the British crown. How did this company gain and consolidate its power and profit?

At the same time as Elizabeth I was signing the East India Company (EIC) into existence in 1600, her counterpart in India – the Mughal emperor Akbar – was ruling over an empire of 750,000 square miles, stretching from northern Afghanistan in the northwest, to central India’s Deccan plateau in in the south and the Assamese highlands in the northeast. By 1600, the Mughal empire (founded by Akbar’s grandfather, Babur, in 1526) had come of age and was embarking on a century of strong centralised power, military dominance and cultural productiveness that would mark the rule of the ‘Great Mughals’. The Mughal court possessed a wealth and magnificence to overshadow anything that Europe could produce at the time, while India’s natural produce and that of its artisans was coveted all over the world.

- Listen | Historian Jon Wilson responds to listener queries and popular search enquiries about the English trading company that went on to become an agent of British imperialism in India during the 18th and 19th centuries

When the East India Company first visited the Mughal court in the early 17th century, it was as supplicants attempting to negotiate favourable trading relations with Akbar’s successor, Emperor Jehangir. The company had initially planned to try and force their way into the lucrative spice markets of south-east Asia, but found this trade was already dominated by the Dutch. After EIC merchants were massacred at Amboyna (in present day Indonesia) in 1623, the company increasingly turned their attention to India.

- “This was a corporation that could topple kings”: William Dalrymple on the East India Company

With Emperor Jehangir’s permission, they began to build small bases, or factories, on India's eastern and western coasts. From these coastal toeholds, they orchestrated the profitable trade in spices, textiles and luxury goods on which their commercial success was predicated, dealing with Indian artisans and producers primarily through Indian middlemen. Meanwhile, the ‘joint stock’ organisation of the company [in which ownership was shared between shareholders] spread the cost and risk of individual voyages between investors. The company grew in both size and influence across the 17th and 18th centuries. Although always volatile, EIC shares became an important bellwether of the British economy and the company emerged as one of London's most powerful financial institutions.

- Listen | William Dalrymple explains how a single London corporation took over the Mughal empire and became a major imperial power on this episode of the HistoryExtra podcast

A player in politics

Initially a junior partner in the Mughal empire’s sophisticated commercial networks, in the 18th century, the EIC became increasingly involved in subcontinental politics. They grappled to maintain their trading privileges in the face of declining central Mughal authority and the emergence of dynamic individual successor states.

More like this

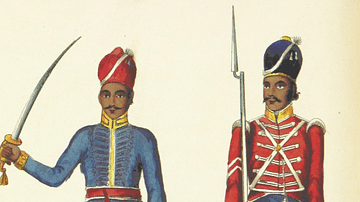

European competitors also began to have an increased presence on the subcontinent, with France emerging as a major national and imperial rival during the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War . This particularly increased the strategic importance of the EIC's Indian footholds, and the country’s coastline became crucial to further imperial expansion in Asia and Africa. As well as maintaining a large standing army consisting primarily of sepoys (Indian mercenary soldiers trained in European military techniques), the EIC was able to call on British naval power and crown troops garrisoned in India.

- The chaotic conquest of India

Such military advantages made the EIC a powerful player in local conflicts and disputes, as did the financial support offered by some local Indian merchants and bankers, who saw in the EIC's increasing influence an unmissable commercial opportunity. After military victories at the battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), the EIC was granted the diwani of Bengal – control over the administration of the region and the right to collect tax revenue. At the same time, the company expanded its influence over local rulers in the south, until by the 1770s the balance of power had fundamentally changed. Expansion continued and rivals such as the Maratha people in western India and Tipu Sultan of Mysore were defeated. By 1818, the EIC was the paramount political power in India, with direct control over two thirds of the subcontinent’s landmass and indirect control over the rest.

A ‘colony of exploitation’

The first years of EIC rule were notorious for their corruption and profiteering – the so-called ‘shaking of the pagoda tree’ or ‘ rape of Bengal ’. Individual nabobs (as EIC employers were derisively dubbed) amassed massive personal fortunes, often at the expense of their Indian subjects. Yet the late 18th century also saw the development of what would become the basis of the EIC state in India, as traders sought to become administrators and develop systems of rule compatible with both their Georgian ideas of political economy and the specific circumstances in India.

India’s large population and sophisticated social, political and economic institutions made imperialistic ideas of terra nullius (empty land) inapplicable in India, and as a result the EIC did not achieve the level of control over the resources of land and labour that characterised British settler communities in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Cape, and the Caribbean. India was a ‘colony of exploitation’, rather than one of settlement; its value to the EIC lay primarily in the profits that could be made by controlling its internal markets and international trade, appropriating peasant production and, above all, collecting tax revenue. These taxes paid for both a large standing army, and a sizeable cadre of EIC employees and covenanted civil servants who worked in India, but did not ultimately settle there.

- The battle of Saragarhi: when 21 Sikh soldiers stood against 10,000 men

The EIC’s rise to political power in India was the subject of heated debate back in Britain. EIC activities in the wake of the 1757 battle of Plassey as a company with huge influence and power – and one which is unafraid to further its interests by nefarious means –were viewed with suspicion – as poet William Cowper put it, the EIC: “Build factories with blood, conducting trade / At the swords point, and dyeing the white robe / Of innocent commercial justice red”.

Against the backdrop of the loss of the American colonies, the emergence of the anti-slavery movement and the French Revolution , the ‘India Question’ took on considerable political importance in Britain. The perceived immorality of EIC actions in India, the fear of private and institutionalised corruption, and tensions between British and ‘Asiatic’ forms of governance resonated with wider concerns about what it meant to be an imperial power, and the responsibilities Britons had to their non-white subjects overseas. Metropolitan concern with EIC activities in the second half of the 18th century manifested itself in popular hostility to returning nabobs , and culminated with the impeachment and trial of former governor general Warren Hastings [for mismanagement and personal corruption] in 1788–95.

The ‘India Question’

Attempts to regulate EIC activities began in the 1770s, with North’s Regulating Act (1773) and Pitt’s India Act (1784), which both sought to bring the company under closer parliamentary supervision. Meanwhile a series of internal reforms under governor general Charles Cornwallis in the late 1780s and early 1790s saw the EIC's administration radically restructured in order to eradicate private corruption. This was intended to improve both the lustre of its public image and the efficiency of its revenue-extracting machine. After the acquittal of Hastings and the implementation of the Cornwallis reforms, the company attempted to rehabilitate its reputation. It aimed to reposition itself as a benevolent and legitimate ruler that extended the limits of civil society and brought both security of property and impartiality of justice to India.

Reforms such as the remodelling of the judiciary and the 1793 Permanent Settlement agreement (which fixed the rate of land tax) took place under the rubric of ‘improving’ Indian society. The EIC increasingly justified its presence in India by using the rhetoric of a ‘civilising mission’, epitomised by the publicity given to showpiece social reform legislation such as the abolition of the rare but controversial practice of sati (widow-burning). However, the actual impact of its activities on local economies and societies was often very different. These reforms were primarily aimed at securing EIC control, facilitating Britain’s longstanding pursuit of wealth, and ensuring her strategic advantage by excluding European rivals from the subcontinent.

The first half of the 19th century was marked by economic depression in India. Excessive land tax demands and lack of investment stunted agricultural development, while traditional industries such as textiles were decimated by the import of cheap manufactured goods. Catastrophic famines, most notably in Bengal (1770) and in the Agra region (1837–8) were exacerbated by the EIC’s tax policies, its laissez faire attitudes towards the grain market, and failures of state relief.

- Famine and freedom: how the Second World War ignited India

While by the early 19th century British attitudes to India were characterised more by ‘pride and complacency’ than by ‘self-flagellation' (to quote historian Peter Marshall), criticism of EIC’s activities and their consequences – both intended and unintended – did not disappear entirely. Rather, these issues remained close to the surface of British public debate. They found expression through a range of issues, sources and media – for example through the vocal, but short-lived activities of the British India Society (1839–43) [Established to ‘enlighten’ people about conditions in India].

Nor did the Indian population simply meekly acquiesce to East India Company dominance. Dispossessed Indian rulers sent numerous delegations to London to protest mistreatment and breach of treaties on the part of the EIC, while various forms of both direct and indirect resistance were endemic throughout the period. Indeed, as historian Sir Christopher Bayly noted, when the fighting that would ultimately bring about the end of the East India Company broke out in 1857, the event was “unique only in its scale”.

In the wake of the uprising of 1857 (often referred to in Britain as the ‘Indian Mutiny’, and in India as the ‘First War of Independence’), observers in Britain were quick to critique the mistakes of the East India Company. Yet the ship had already sailed: once the uprising had been suppressed – with great brutality and loss of life on both sides – control of India passed from the East India Company to the crown, ushering the period of high imperialism in India epitomised by the Raj.

Andrea Major is professor in British colonial history at the University of Leeds

This article was first published by HistoryExtra in January 2017

Summer Sale is now live - save 86% when you get your first 5 issues for £5

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

SUMMER SALE! Subscribe now for £5!

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

After overseeing the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I issued a royal charter authorizing British merchants to trade in the East Indies on behalf of the crown.

How the East India Company became the world’s most powerful business

The trading firm took command of an entire subcontinent and left behind a legacy that still impacts modern life.

Think Google or Apple are powerful? Then you’ve never heard of the East India Company, a profit-making enterprise so mighty, it once ruled nearly all of the Indian subcontinent. Between 1600 and 1874, it built the most powerful corporation the world had ever known, complete with its own army, its own territory, and a near-total hold on trade of a product now seen as quintessentially British: Tea.

At the dawn of the 17th century, the Indian subcontinent was known as the “East Indies,” and—as home to spices, fabrics, and luxury goods prized by wealthy Europeans—was seen as a land of seemingly endless potential. Due to their seafaring prowess, Spain and Portugal held a monopoly on trade in the Far East. But Britain wanted in, and when it seized the ships of the defeated Spanish Armada in 1588, it paved the way for the monarchy to become a serious naval power.

A painting of a British East India Company official riding on an elephant at the end of the 18th century.

In 1600, a group of English businessmen asked Elizabeth I for a royal charter that would let them voyage to the East Indies on behalf of the crown in exchange for a monopoly on trade. The merchants put up nearly 70,000 pounds of their own money to finance the venture, and the East India Company was born.

The corporation relied on a “factory” system , leaving representatives it called “factors” behind to set up trading posts and allowing them to source and negotiate for goods. Thanks to a treaty in 1613 with the Mughal emperor Jahangir, it established its first factory in Surat in what is now western India. Over the years, the company shifted its attention from pepper and other spices to calico and silk fabric and eventually tea, and expanded into the Persian Gulf, China, and elsewhere in Asia.

Mughal emperor Shah Alam II grants Robert Clive, leader of the East India Company’s army, the ability to collect taxes in Bengal.

The East India Company’s royal charter gave it the ability to “wage war,” and initially it used military force to protect itself and fight rival traders. In 1757, however, it seized control of the entire Mughal state of Bengal. Robert Clive, who led the company’s 3,000-person army, became Bengal’s governor and began collecting taxes and customs, which were then used to purchase Indian goods and export them to England. The company then built on its victory and drove the French and Dutch out of the Indian subcontinent.

In the years that followed, the East India company forcibly annexed other regions of the subcontinent and forged alliances with rulers of territory they could not conquer. At its height, it had an army of 260,000 (twice the size of Britain’s standing army) and was responsible for almost half of Britain’s trade. The subcontinent was now under the rule of the East India Company’s shareholders, who elected "merchant-statesmen" each year to dictate policy within its territory.

But financial woes and a widespread awareness of the company’s abuses of power eventually led Britain to seek direct control of the East India Company. In 1858, after a long wind down, the British government finally ended company rule in India. By 1874, the company was a shell of its former shelf and was dissolved.

By then, the East India Company had been involved in everything from getting China hooked on opium (the Company grew opium in India, then illegally exported it to China in exchange for coveted Chinese goods) to the international slave trade (it conducted slaving expeditions , transported slaves and used slave labor throughout the 17th and 18th centuries). The East India Company may have since been overshadowed by modern capitalism, but its legacy is still felt around the world.

Related Topics

- IMPERIAL CHINA

You May Also Like

Was Manhattan really sold to the Dutch for just $24?

These treasure-hunting pirates already came from riches

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

Why Lunar New Year prompts the world’s largest annual migration

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Interactive Graphic

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Modern History

The rise and fall of the British East India Company

The British East India Company, once a mere trading entity, evolved into a colossal force that reshaped the destiny of India.

From its humble beginnings in the bustling ports of England to its meteoric rise as a quasi-imperial power in the heart of Asia, the company dominated India for over 200 years.

But how did a group of English merchants come to wield such unparalleled power?

What challenges did they face in their quest for dominance?

And what impact did they have on the peoples and cultures of India?

The East India Company was founded on the 31st of December 1600, with the goal of establishing trade relations between England and the East Indies.

The company was established by a group of more than 200 English merchants who appealed to Queen Elizabeth I, who was then the queen of England.

As a result, the Queen issued the company with a Royal Charter, allowing it to monopolise trade in the Far East.

In 1601, the East India Company built its first trading posts in Bantam and Moluccas.

The company then began to expand its operations, eventually establishing a network of trading posts across the Indian subcontinent.

The East India Company and the Mughal Empire

The East India Company's expansion into India was not without its challenges. The most significant challenge came in the form of the Mughal Empire , which was then one of the most powerful empires in the world.

In 1612, the English king James I sent a request to the Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir, asking for permission for the British East India Company to enter Indian territory.

The Mughals were initially reluctant to allow the East India Company to establish itself in India.

The British East India Company sought coveted trading privileges in India in exchange for British pledges to send the Mughal emperor exclusively manufactured products from Europe.

Jahangir eventually accepted the conditions of the British proposal.

Even though the British East India Company began operations in India from around 1607, it was only after the Mughal acceptance of their presence that their influence began to be felt.

By 1647, The East India Company had established 23 factories in India, including ones in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay.

Cotton, silk, dyes, saltpetre, and tea were the main commodities sought by the company at this time.

In 1670, the English king, Charles II, passed several laws to strengthen the British East India Company's position in India, grant the company more autonomy and privileges.

In general, these statutes permitted the firm to expand into new areas, establish its own currency, and build fortresses.

The British East India Company's success in the textile industry was due, in part, to factors such as this.

As a result, during the 17th and 18th centuries, it became the world leader in textile trade with India.

Most significantly, the British East India Company began to create its own private armies in order to spread their dominance throughout India.

For example, the European powers in India frequently recruited and employed Indian males into their own military forces, called sepoys.

Sepoys were Indian troops who fought for European colonial powers or trading companies during the colonial period.

The East India Company and Colonialism

The company quickly grew in power and influence, and by the mid-1700s, it had become one of the most powerful organisations in the world.

On 23 June 1757, the British East India Company routed the Nawab (the title of the Muslim ruler) of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, and his French allies in the Battle of Plassey.

The French had chosen to assist the Nawabs, who had their own economic motivation in the area, but their defeat in the battle only reduced their power in the country.

The British East India Company's victory in the Battle of Plassey was crucial for two reasons: it provided the company a foothold in Bengal from which to extend throughout India, and it secured its future.

The company then began to expand its territory, eventually colonising India.

The British government and the East India Company established a dual system of control in 1757, dividing duties between them.

Important political matters were kept for the parliament, while commercial issues were handed over to the company.

In 1784, Prime Minister William Pitt issued the 'India Act', which placed the company under the direct control of the British government.

From 1757 until 1858, therefore, the British East India Company ruled India as a sort of colony.

Because of this, historians have dubbed it 'Company Rule'. By 1857, the British East India Company had at least 267,000 troops under its command.

The company's power began to decline in the early 1800s, due to a number of factors including internal corruption and external pressure from other European powers.

The British East India Company's rule over India came to an end with the Indian Rebellion of 1857 .

The rebellion was sparked by a number of factors, including the company's high taxes, its mistreatment of Indians, and its policy of favouring Europeans over Indians.

The rebellion quickly spread across the country, and it took several years for the British to regain control.

In 1858, the British government took over control of India from the East India Company, and began ruling it as a colony.

As a result, the East India Company was eventually dissolved during the 1870s. This began the period of Indian history known as the British Raj.

The British Raj was the period of British rule over India until 1947.

During this time, the British government controlled India's economy, politics, and society. Indian culture and traditions were also greatly influenced by the British Raj.

The legacy of the British East India Company is a mixed one. On the one hand, it was a powerful force that shaped the history of India and played a significant role in the development of the country.

On the other hand, its rule was often harsh and oppressive, and it left a legacy of division and conflict that continues to this day.

Nevertheless, the company's impact on India cannot be denied.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

The History of The East India Company

The British East India Company (EIC) was founded as a trading company in 1600. Run by a board of directors in London, the company employed a private army, first to protect the trade it conducted in the Indian subcontinent and then to expand its territories as it rampantly colonised its competition.

This collection examines the history of the company from beginning to end, the many wars it engaged in, the trade goods it shipped around the world and the consequent effects on diverse cultures, how it evolved and was constrained by regulation, and its ultimate demise in 1858 when it was taken over by the British government.

The British Parliament were aghast at lurid tales of the EIC's policies in India , and many sought to bring the company under much greater scrutiny and control...The burning question of the day was why was this private company with private interests being allowed to conduct itself like a state but without any of the constraints of an electorate or any of the scruples of justice.

Articles & Definitions

East India Company

Trade Goods of the East India Company

The Armies of the East India Company

Battle of Plassey

Anglo-Mysore Wars

Anglo-Maratha Wars

Anglo-Nepalese War

First Anglo-Afghan War

First Anglo-Sikh War

Second Anglo-Sikh War

Sepoy Mutiny

Fall of the East India Company

External links, questions & answers, how did the east india company start, what are 2 important moments in the history of the british east india company, what happened to the east india company, when did the east india company first come to india, about the author.

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

License & Copyright

Uploaded by Mark Cartwright , published on 02 February 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

The British East India Company Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

A brief contextual history of chartered companies, the establishment and organization of east india company (eic).

Bibliography

Even today the term Chartered Company is usually applied with reference to the great chartered that existed from the sixteenth to eighteenth century including the likes of English, French and Dutch East Asia companies. These establishments were formed for other purposes other than trade and continued flourishing beyond the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Evidence of this can be seen by turning to a recent stock exchange yearbook where a list of British Chartered companies will be identified. According to statistics provided by Oriental, in the volume compiled for the year 1960, there were seventeen of these companies listed.

The origins of these Chartered companies can be traced back to an era during the Middle Ages. It was during this age that it was observed that not all enterprises could be operated by individuals on their own account or by partnerships. It became apparent that a corporate form was necessary to conduct business in an efficient and proper fashion. Following this, the English developed several ways of forming such a corporation; through parliamentary authority, using common law and by prescription or charter of the King.

As suggested in the name, the option of incorporation by charter became the most popular method of formation of these companies. The charter drafted on paper was a document by which the state conferred certain privileges on corporate bodies. Among the privileges accorded these companies was state protection in their excursions whether at home or abroad.

This explains how these corporations accompanied by soldiers spread across the world. In this paper, the discussions presented will delve into the subject of these chartered companies. A brief history and an analysis of their role in history and politics will be presented. Based on the facts a conclusion will be offered suggesting their role if any in business today.

Having established how these companies came into existence it is essential to also answer the question as to why they were created. The answer to this lies in the fact that documentary evidence was required to protect the trades and industries within the country in the event of civil commotion, feudal oppression and general lawlessness. These companies were initially limited to particular localities within a state but owing to mutual advantages to both the Crown and the corporations their realm rapidly expanded.

It has been reported that during periods of border warfare between Scotland, Wales and eventually during the disastrous War of the Roses, numerous of these concessions were granted to the Great trade guilds. Prior to this these private bodies were institutions acting in the common interests of their craft.

However, upon receiving these state concessions, they were accorded numerous immunities, privileges and monopolies in exchange for services and money grants to the Crown in times of emergency. Among the trades that benefited from these concessions included goldsmiths, haberdashers, fishmongers, etc. These charters formed the basis upon which future charters with merchant classes that carried out trade across borders. However, it was the effects of these charters that led to the economic growth that saw an increased need for raw materials.

According to reports by Gupta, the British East India Company (EIC) was formed around the year 1600. Within a period of fifteen years after incorporation, the King of England had noted the immense value trade from this region had brought to England.

The principal driving factor behind this immense benefit could be traced to activities of the native rulers abroad and the role of the English Crown. The native rulers sought to attain the most favourable trading treatment possible while the Crown managed to build a monopoly of English trade in the region of the East Indies.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, the power of the Crown had expanded steadily albeit unevenly following the conquest of the Bengal region on the eastern coast in 1765. Following this efforts to expand trade opportunities in the region required the involvement in Indian political affairs with the result that there arose an era of intense political aggression and military conquest.

Following this intense campaign unrest increased within the local communities and eventually led to the Indian Mutiny in 1857-1858. During the period of the campaign, the company gradually shifted its interests from those of a trading corporation to that of a colonial power. As expected this shift in focus also led to a shift in strategy used by the company in the region.

As mentioned in the introduction these charters included privileges such as trade monopolies which were of great value to their home states. It is important to note at this on that prior to this campaign there were other East Indian companies in operation in the region. The Dutch, French and Danish companies had co-existed with the British East India Company in the region from 1600 to the late 1700s.

This suggests that the period of the 1800s marked the beginning of British monopoly in the region and may have been the reason behind the change in focus.

Following the exit of the other companies, the British implemented strategies to increase their authority in their coastal territories and expand control further inland. Owing to this by 1820 the company controlled the greater portion of this sub-continent. Local control was achieved through varied forms of land administration.

This saw the formation of presidencies in Bengal, Madras and Bombay. Majority of local administrators were selected from the land owners who were given charge of the peasantry. In other states, annexation which allowed for the levying of taxes in exchange for protection was practiced. In many cases, the steep charges of annexation eventually led to the complete conquest of regions.

As the territory grew in size the company embarked on training programs in England for administrative officials who were to be incorporated in the civil service. These civil servants were posted in newly created districts inland to perform administrative and company duties.

The district official was charged with duties which included; dispute resolution through court where they acted as magistrates, revenue collection within the district and control of the district police. Within these subunits the knowledgeable and skilled locals were enlisted though owing to racial innuendo they were barred from any high-ranking offices.

Having so far highlighted the role of the monarchs and governments in this history of this company, the discussion will also briefly glimpse at the role of merchants. The main purpose of this company was trade which essentially described the purchase of goods in Asia and their sale in Europe. The agents of the company were accorded the privilege to trade from one part of the Indian Ocean to another with exception of Europe.

This privilege was also extended to license holders not employed by the company also known as free merchants. Within the territories, the company would make arrangements with local rulers to establish factories from which its agents would procure goods and transport them either inland or abroad. Inland trade was meant to be free from duties though these concessions were often vague and prone to misinterpretation by territorial rulers.

As it can be seen from the above paragraph the operations of this company were not without challenges. However, it has been suggested that the work of these merchants in the various territories may have been the driving force behind colonization. In fact some authors have argued that the formation of these companies was part of a political machine with a single objective of gaining resources and control associated with those resources.

This position is reflected in the fact that from the establishment of this company, it concerned itself with trade and expansion of its trade territory. It would be unrealistic in the opinion of mercantilism to continue expansion of trade without government regulation and involvement.

This point is further strengthened by the fact that local rulers in India were used to using despotic means over their citizens. As such it was easy to use strategies such as annexation to gradually take control of the entire region. On clear aspect that is evident from the performance of these companies is the existence of a persistent link between state affairs and regional trade. This is due to the fact that a well-orchestrated partnership between the two allowed these companies to survive in a period that spanned over two centuries.

In this paper, the discussion presented introduced the subject of trading companies that existed within governments that colonized vast territories of the world in the past. The discussion suggests criteria that led to their formation and subsequent sections have shown how these partnerships flourished amid changing times. Owing to this it has been suggested that the merchants of these times provide on possible core of information for free-standing firms today.

It is possible that these companies formed the basis for business entities as we know them today. According to Jones, both firms and individuals attempt to create institutional forms when existing ones fail to efficiently meet transaction relationship requirements. This suggests that what we see today may be due to attempts to replace these companies owing to their inability to survive in the free world.

Bowen, Huw, Margarette Lincoln and Nigel Rigby. The worlds of the East India Company . Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2002.

Carter, Mia and Barbara Harlow. Archives of Empire: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal . USA: Duke University Press, 2003.

Cavendish, Marshall. World and its People: Eastern and Southern Asia . New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 2007.

Cawston, George and Augustus Henry Keane. The Early Chartered Companies (A.D. 1296-1858) . New Jersey: The Law Book Exchange Ltd., 2003.

Chaudhuri, Kirti Narayan. The trading world of Asia and the English East India Company . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Gupta, Brijen Kishore. Sirajdullah and the East India Company, 1756-1757 . Netherlands: E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1962.

Jones, Geoffrey. The multinational traders . London: Routledge, 1998.

Orhinal, Tony. Limited liability and the corporation . London: Action Society Trust, 1982.

- The Comparison of Georgia and Rhode Island Charters

- Complex Foundations: The Inland Revenue Building

- The Requirements for Chartered Financial Analyst Designation

- Why did Europe undergo such a bloody and destructive period from 1914-1945?

- How Did the Age of Enlightenment Influence Western Civilization

- History of Hitler’s Nazi Propaganda

- European Jewry in the 18th And 19th Centuries

- The background and evolution of British policy regarding the Palestine issue

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 27). The British East India Company. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-british-east-india-company/

"The British East India Company." IvyPanda , 27 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-british-east-india-company/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The British East India Company'. 27 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The British East India Company." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-british-east-india-company/.

1. IvyPanda . "The British East India Company." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-british-east-india-company/.

IvyPanda . "The British East India Company." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-british-east-india-company/.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The east india company 1600–1858: a short history with documents, by ian barrow indianapolis: hackett publishing company, 2017 208 pages, isbn: 978-1624665967, paperback reviewed by michelle damian.

Ian Barrow’s slim volume uses the East India Company (or, as he refers to it throughout the book, simply the “Company”) as a case study through which to examine Britain’s colonial journey. From the Company’s inception in 1600 to its formal dissolution in 1874, its trajectory reflects England’s expanding global trade to obtaining a foothold in foreign lands to its problematic role as a colonizing country, through the growing challenges to and eventual collapse of that colonial authority. It is a concise history, but works well at bringing those multiple threads into one story.

One of the strengths of this volume is the way it treats the ripple effect of maritime trade, particularly as conducted on a global scale. In the first chapter, Barrow follows the various products that were of interest to the Company, beginning with spices and proceeding on to silver, textiles, and eventually tea and sugar. It is not a simple exchange, however; as one product became available on the market, it affected other aspects of seventeenth-century life. As the Company increased its trading capabilities in India and silver flooded the market, for example, it resulted in a population shift as weavers moved to the cities to take advantage of that increased trade. The resulting availability of cotton print textiles allowed merchants to sell them cheaply in England, causing domestic sales of woolen clothing to plummet. Parliament intervened by creating laws to force citizens to wear wool clothing and raised import duties on cotton. This engendered an initial backlash against the Company but eventually ended with a new industry developing in England: dyeing of the imported plain white cotton. Though that is just one example of the complexities of seventeenth-century global trade, it provides a more robust picture than simply noting that textiles were an important commodity for the Company.

The second chapter, focusing on the eighteenth century, notes that while the Company’s role began with trade, as its network expanded, so too did its power abroad. Military ventures in India became more important, and Barrow focuses on political and economic methods that the Company used to strengthen its authority on the ground there. There was, however, a growing disconnect between those working for the Company in its colonial outposts and those watching it from back home. As its influence abroad grew, it was subject to additional restrictions from Parliament. The Regulating Act of 1773 created a governor general position and court system based in Calcutta that shifted some of the Company’s power to politicians, intertwining the interests of the state with the interests of the Company. The influx of wealth created class divides both among the British and the Indians. “Nabobs” (from the Arabic and Urdu title nawab), or Company employees, would make as much money as quickly as possible in India and then return to England to live large. New classes of landowners and rent collectors in Bengal often then sold to others the rights to collect rents, creating multiple layers of oversight. The discussion demonstrates the ramifications of the growing presence of the Company and its shift from a focus on trade to landholding and government.

Barrow’s detail on the stories of the colonized countries, particularly the Indian interactions with the Company’s representatives and the conflicts that ensued, is a valuable aspect of this work. Instead of writing a story only about the colonizing power, Barrow looks at the complexities of Indian reactions to the changing Company influences. His descriptions of the various uprisings in the nineteenth century are particularly illuminating of the different factions within India. In addition, his focus on the contentious role of religion in the Company’s actions in Asia is an important one. Barrow traces the shifting attitudes toward religious involvement in Asia as a parallel to Britain’s conflicted relationship with religion. He begins with the Company keeping the church at arm’s length to using Hindu and Muslim temples as a gateway to interactions with the locals to a gradual rise of evangelicalism and the growing power of the church as it came to influence political reform in India. After over 250 years of waxing and waning fortunes, the Company’s demise after increased rebellions in India seems almost anticlimactic, as this highly influential power suddenly disappeared from the political and economic landscape of British-Asian relations.

One slightly disappointing aspect of the book stems from its subtitle, A Short History with Documents. I had expected and hoped that the primary sources would comprise a significant portion of the volume. Instead, there were eighteen documents, some of which were only selections from the original source, making up thirty-four pages of the 176-page book. Admittedly, my reaction may have stemmed from my home department’s teaching curriculum, which prioritizes the analysis of primary sources in our introductory classes, and I anticipated a more robust selection of sources. Still, the documents are usually not even explicitly referred to in the body of the text. A reference in the footnotes that a longer excerpt is available at the end of the book, or perhaps the inclusion of several documents at the end of each relevant chapter, would have been helpful.

On a similar note, several images (political cartoons, broadsides, and artwork) are scattered throughout the body of the text. While their inclusion is certainly appreciated, it would have been extremely interesting had these, too, been explicitly put forward as another type of document to be analyzed. Too often historians focus on “documents” solely as the written word present in sources such as letters, statutes, and laws, and overlook these other types of evidence as having a wealth of information in their own right. Figure 3, for example, is a political cartoon depicting the corruption of the Company as embodied by Warren Hastings, Governor General in 1788. It is a rich source, and Barrow’s caption does call attention to Hastings’s clothing (“Oriental”), the king scooping coins from the toilet upon which Hastings sits, and the other figures in the image. That being said, there is more to this scene that is left unmined. Additional words are in the cartoon, including Hastings speaking something, more words inscribed on the toilet, and an unclear inset that, had they been transcribed, could have provided the reader with additional information. One corner is filled with hats outstretched for handouts that appear to represent people from many different social strata, including what appears to be a representative of the church, but there is no acknowledgment of that. Several objects that may be medals are in a lower corner, but again are unclear. While the inclusion of these images is appreciated, as a volume that is privileging source documents in its title, I would hope that these types of sources would receive as detailed attention as the more typical diaries and news articles in the documents section.

In a more positive light, there are many resources in this volume that will be beneficial for students and nonspecialists. A chronology, glossary, and series of maps provide useful aids to understanding and visualizing new concepts in the readings. Barrow closes with a concise and easily comprehensible summation of how the Company’s story is important as a case study of colonial rule and imperialism, and this will be one of the book’s most valuable aspects for educators. It is story that is easy to follow, even in its complexity, and incorporates economic, religious, ethnic, political, and military history throughout the narrative. Students should find various topics that will hold their interest in this very readable book. ■

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

MICHELLE DAMIAN is currently an Assistant Professor in the History Department of Monmouth College, Illinois. She has an MA in Maritime History and Nautical Archaeology from East Carolina University and a PhD in History from the University of Southern California. Her current research focuses on maritime trade routes and networks of medieval Japan. She is also a member of the Board of Directors for the Museum of Underwater Archaeology ( http://www.themua.org ).

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

The AAS Secretariat is closed on Thursday, July 4 and Friday, July 5 in observance of the Independence Day holiday

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

The East India Company, 1600-1857

DOI link for The East India Company, 1600-1857

Get Citation

This book employs a wide range of perspectives to demonstrate how the East India Company facilitated cross-cultural interactions between the English and various groups in South Asia between 1600 to 1857 and how these interactions transformed important features of both British and South Asian history. Rather than viewing the Company as an organization projecting its authority from London to India, the volume shows how the Company’s history and its broader historical significance can best be understood by appreciating the myriad ways in which these interactions shaped the Company’s story and altered the course of history. Bringing together the latest research and several case studies, the work includes examinations of the formulation of economic theory, the development of corporate strategy, the mechanics of state finance, the mapping of maritime jurisdiction, the government and practice of religions, domesticity, travel, diplomacy, state formation, art, gift-giving, incarceration, and rebellion. Together, the essays will advance the understanding of the peculiarly corporate features of cross-cultural engagement during a crucial early phase of globalization.

Insightful and lucid, this volume will be useful to scholars and researchers of modern history, South Asian studies, economic history, and political studies.

TABLE OF CONTENTS