10 technology trends to watch in the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus demonstrates the importance of and the challenges associated with tech like digital payments, telehealth and robotics. Image: REUTERS/David Estrada

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Yan Xiao

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated 10 key technology trends, including digital payments, telehealth and robotics.

- These technologies can help reduce the spread of the coronavirus while helping businesses stay open.

- Technology can help make society more resilient in the face of pandemic and other threats.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, technologies are playing a crucial role in keeping our society functional in a time of lockdowns and quarantines. And these technologies may have a long-lasting impact beyond COVID-19.

Have you read?

Apple and google are working together on technology for coronavirus contact tracing, coronavirus: graduates replaced with robots in japan.

Here are 10 technology trends that can help build a resilient society, as well as considerations about their effects on how we do business, how we trade, how we work, how we produce goods, how we learn, how we seek medical services and how we entertain ourselves.

1. Online Shopping and Robot Deliveries

In late 2002, the SARS outbreak led to a tremendous growth of both business-to-business and business-to-consumer online marketplace platforms in China .

Similarly, COVID-19 has transformed online shopping from a nice-to-have to a must-have around the world. Some bars in Beijing have even continued to offer happy hours through online orders and delivery.

Online shopping needs to be supported by a robust logistics system. In-person delivery is not virus-proof. Many delivery companies and restaurants in the US and China are launching contactless delivery services where goods are picked up and dropped off at a designated location instead of from or into the hands of a person. Chinese e-commerce giants are also ramping up their development of robot deliveries . However, before robot delivery services become prevalent, delivery companies need to establish clear protocols to safeguard the sanitary condition of delivered goods.

2. Digital and Contactless Payments

Cash might carry the virus, so central banks in China, US and South Korea have implemented various measures to ensure banknotes are clean before they go into circulation. Now, contactless digital payments, either in the form of cards or e-wallets, are the recommended payment method to avoid the spread of COVID-19. Digital payments enable people to make online purchases and payments of goods, services and even utility payments, as well as to receive stimulus funds faster.

However, according to the World Bank, there are more than 1.7 billion unbanked people, who may not have easy access to digital payments. The availability of digital payments also relies on internet availability, devices and a network to convert cash into a digitalized format.

3. Remote Work

Many companies have asked employees to work from home . Remote work is enabled by technologies including virtual private networks (VPNs), voice over internet protocols (VoIPs), virtual meetings, cloud technology, work collaboration tools and even facial recognition technologies that enable a person to appear before a virtual background to preserve the privacy of the home. In addition to preventing the spread of viruses, remote work also saves commute time and provides more flexibility.

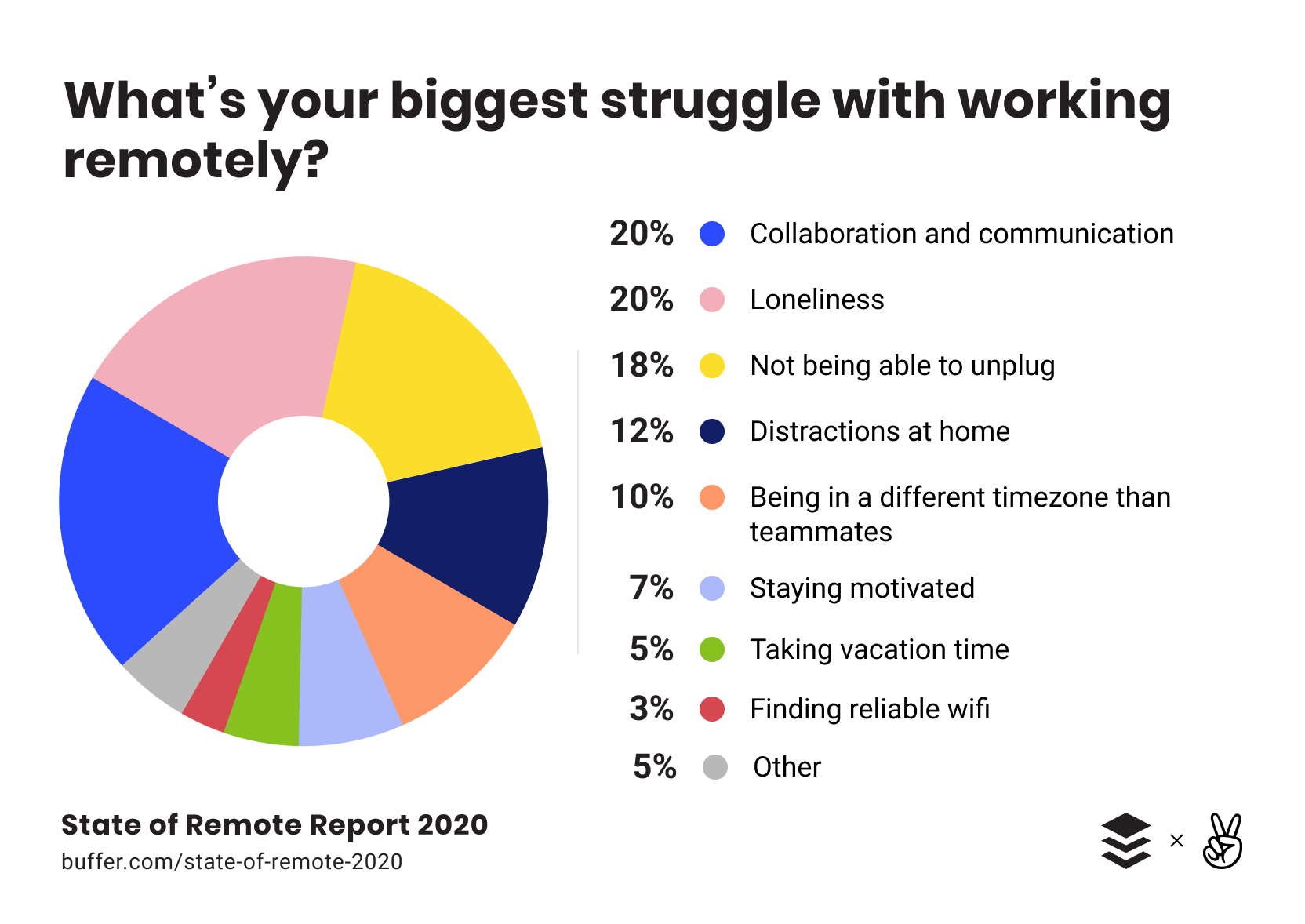

Yet remote work also imposes challenges to employers and employees. Information security, privacy and timely tech support can be big issues, as revealed by recent class actions filed against Zoom . Remote work can also complicate labour law issues, such as those associated with providing a safe work environment and income tax issues. Employees may experience loneliness and lack of work-life balance . If remote work becomes more common after the COVID-19 pandemic, employers may decide to reduce lease costs and hire people from regions with cheaper labour costs .

Laws and regulations must be updated to accommodate remote work – and further psychological studies need to be conducted to understand the effect of remote work on people.

Further, not all jobs can be done from home, which creates disparity. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 25% of wage and salary workers worked from home at least occasionally from 2017 to 2018. Workers with college educations are at least five times more likely to have jobs that allow them to work from home compared with people with high school diplomas. Some professions , such as medical services and manufacturing, may not have the option at all. Policies with respect to data flows and taxation would need to be adjusted should the volume of cross-border digital services rise significantly.

4. Distance Learning

As of mid-April, 191 countries announced or implemented school or university closures, impacting 1.57 billion students. Many educational institutions started offering courses online to ensure education was not disrupted by quarantine measures. Technologies involved in distant learning are similar to those for remote work and also include virtual reality, augmented reality, 3D printing and artificial-intelligence-enabled robot teachers .

Concerns about distance learning include the possibility the technologies could create a wider divide in terms of digital readiness and income level. Distance learning could also create economic pressure on parents – more often women – who need to stay home to watch their children and may face decreased productivity at work.

5. Telehealth

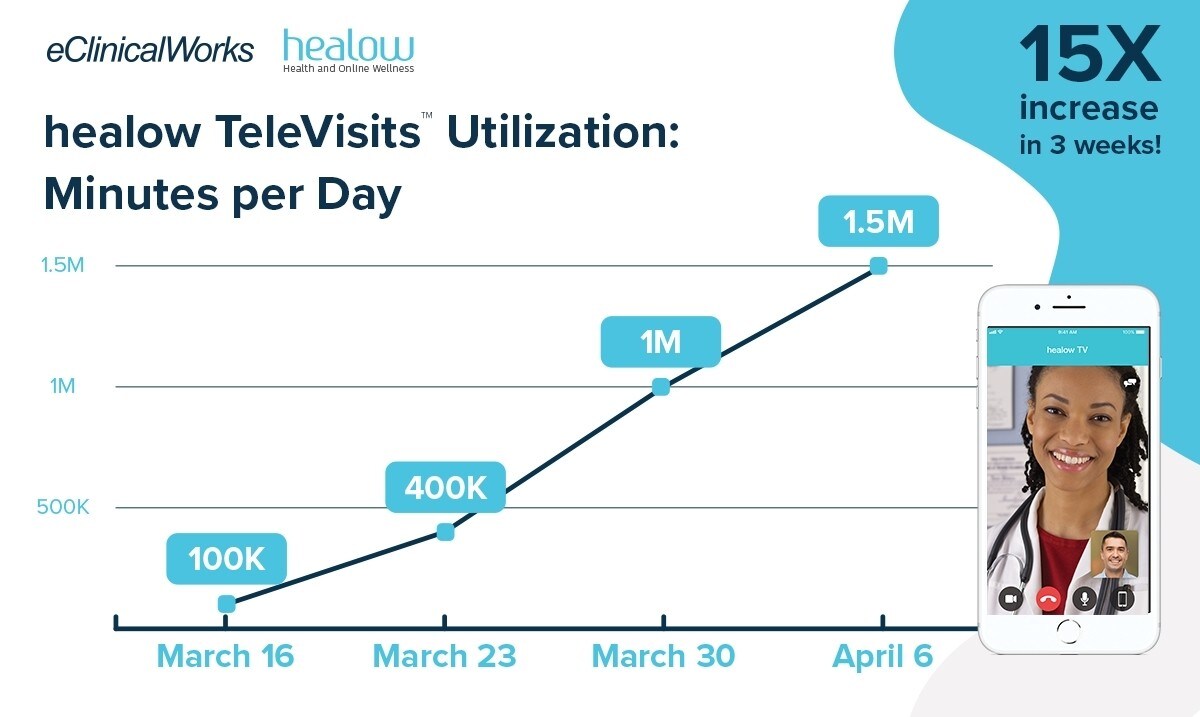

Telehealth can be an effective way to contain the spread of COVID-19 while still providing essential primary care. Wearable personal IoT devices can track vital signs. Chatbots can make initial diagnoses based on symptoms identified by patients.

However, in countries where medical costs are high, it's important to ensure telehealth will be covered by insurance . Telehealth also requires a certain level of tech literacy to operate, as well as a good internet connection. And as medical services are one of the most heavily regulated businesses, doctors typically can only provide medical care to patients who live in the same jurisdiction. Regulations , at the time they were written, may not have envisioned a world where telehealth would be available.

6. Online Entertainment

Although quarantine measures have reduced in-person interactions significantly, human creativity has brought the party online. Cloud raves and online streaming of concerts have gain traction around the world. Chinese film production companies also released films online . Museums and international heritage sites offer virtual tours. There has also been a surge of online gaming traffic since the outbreak.

7. Supply Chain 4.0

The COVID-19 pandemic has created disruptions to the global supply chain. With distancing and quarantine orders, some factories are completely shut down. While demand for food and personal protective equipment soar, some countries have implemented different levels of export bans on those items. Heavy reliance on paper-based records , a lack of visibility on data and lack of diversity and flexibility have made existing supply chain system vulnerable to any pandemic.

Core technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, such as Big Data, cloud computing, Internet-of-Things (“IoT”) and blockchain are building a more resilient supply chain management system for the future by enhancing the accuracy of data and encouraging data sharing.

The World Economic Forum was the first to draw the world’s attention to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the current period of unprecedented change driven by rapid technological advances. Policies, norms and regulations have not been able to keep up with the pace of innovation, creating a growing need to fill this gap.

The Forum established the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Network in 2017 to ensure that new and emerging technologies will help—not harm—humanity in the future. Headquartered in San Francisco, the network launched centres in China, India and Japan in 2018 and is rapidly establishing locally-run Affiliate Centres in many countries around the world.

The global network is working closely with partners from government, business, academia and civil society to co-design and pilot agile frameworks for governing new and emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) , autonomous vehicles , blockchain , data policy , digital trade , drones , internet of things (IoT) , precision medicine and environmental innovations .

Learn more about the groundbreaking work that the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Network is doing to prepare us for the future.

Want to help us shape the Fourth Industrial Revolution? Contact us to find out how you can become a member or partner.

8. 3D Printing

3D printing technology has been deployed to mitigate shocks to the supply chain and export bans on personal protective equipment. 3D printing offers flexibility in production: the same printer can produce different products based on different design files and materials, and simple parts can be made onsite quickly without requiring a lengthy procurement process and a long wait for the shipment to arrive.

However, massive production using 3D printing faces a few obstacles. First, there may be intellectual property issues involved in producing parts that are protected by patent. Second, production of certain goods, such as surgical masks, is subject to regulatory approvals , which can take a long time to obtain. Other unsolved issues include how design files should be protected under patent regimes, the place of origin and impact on trade volumes and product liability associated with 3D printed products.

9. Robotics and Drones

COVID-19 makes the world realize how heavily we rely on human interactions to make things work. Labor intensive businesses, such as retail, food, manufacturing and logistics are the worst hit.

COVID-19 provided a strong push to rollout the usage of robots and research on robotics. In recent weeks, robots have been used to disinfect areas and to deliver food to those in quarantine. Drones have walked dogs and delivered items .

While there are some report s that predict many manufacturing jobs will be replaced by robots in the future, at the same time, new jobs will be created in the process. Policies must be in place to provide sufficient training and social welfare to the labour force to embrace the change.

10. 5G and Information and Communications Technology (ICT)

All the aforementioned technology trends rely on a stable, high-speed and affordable internet. While 5G has demonstrated its importance in remote monitoring and healthcare consultation, the rollout of 5G is delayed in Europe at the time when the technology may be needed the most. The adoption of 5G will increase the cost of compatible devices and the cost of data plans . Addressing these issues to ensure inclusive access to internet will continue to be a challenge as the 5G network expands globally.

The importance of digital readiness

COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of digital readiness, which allows business and life to continue as usual – as much as possible – during pandemics. Building the necessary infrastructure to support a digitized world and stay current in the latest technology will be essential for any business or country to remain competitive in a post-COVID-19 world, as well as take a human-centred and inclusive approach to technology governance .

As the BBC points out, an estimated 200 million people will lose their jobs due to COVID-19. And the financial burden often falls on the most vulnerable in society. Digitization and pandemics have accelerated changes to jobs available to humans. How to mitigate the impact on the larger workforce and the most vulnerable is the issue across all industries and countries that deserves not only attention but also a timely and human-centred solution.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on COVID-19 .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Winding down COVAX – lessons learnt from delivering 2 billion COVID-19 vaccinations to lower-income countries

Charlotte Edmond

January 8, 2024

Here’s what to know about the new COVID-19 Pirola variant

October 11, 2023

How the cost of living crisis affects young people around the world

Douglas Broom

August 8, 2023

From smallpox to COVID: the medical inventions that have seen off infectious diseases over the past century

Andrea Willige

May 11, 2023

COVID-19 is no longer a global health emergency. Here's what it means

Simon Nicholas Williams

May 9, 2023

New research shows the significant health harms of the pandemic

Philip Clarke, Jack Pollard and Mara Violato

April 17, 2023

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

The internet and the pandemic, 90% of americans say the internet has been essential or important to them, many made video calls and 40% used technology in new ways. but while tech was a lifeline for some, others faced struggles.

Pew Research Center has a long history of studying technology adoption trends and the impact of digital technology on society. This report focuses on American adults’ experiences with and attitudes about their internet and technology use during the COVID-19 outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,623 U.S. adults from April 12-18, 2021. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Chapter 1 of this report includes responses to an open-ended question and the overall report includes a number of quotations to help illustrate themes and add nuance to the survey findings. Quotations may have been lightly edited for grammar, spelling and clarity. The first three themes mentioned in each open-ended response, according to a researcher-developed codebook, were coded into categories for analysis.

Here are the questions used for this report , along with responses, and its methodology .

The coronavirus has transformed many aspects of Americans’ lives. It shut down schools, businesses and workplaces and forced millions to stay at home for extended lengths of time. Public health authorities recommended limits on social contact to try to contain the spread of the virus, and these profoundly altered the way many worked, learned, connected with loved ones, carried out basic daily tasks, celebrated and mourned. For some, technology played a role in this transformation.

Results from a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted April 12-18, 2021, reveal the extent to which people’s use of the internet has changed, their views about how helpful technology has been for them and the struggles some have faced.

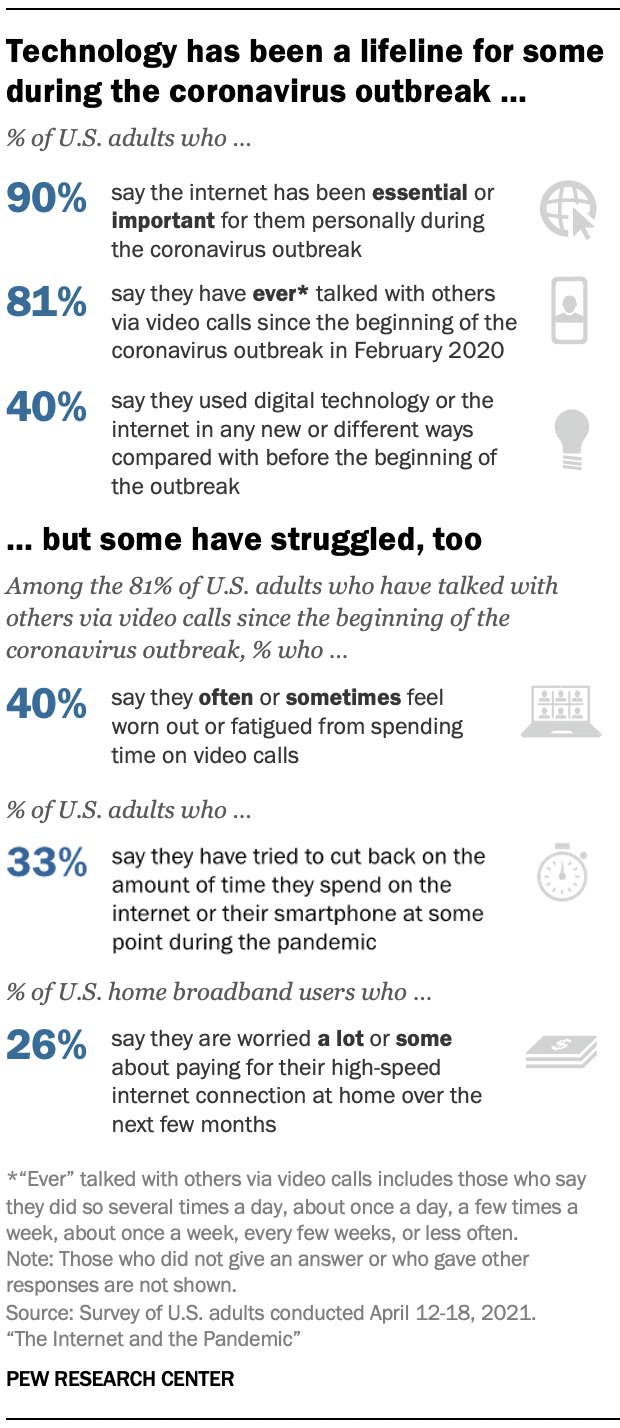

The vast majority of adults (90%) say the internet has been at least important to them personally during the pandemic, the survey finds. The share who say it has been essential – 58% – is up slightly from 53% in April 2020. There have also been upticks in the shares who say the internet has been essential in the past year among those with a bachelor’s degree or more formal education, adults under 30, and those 65 and older.

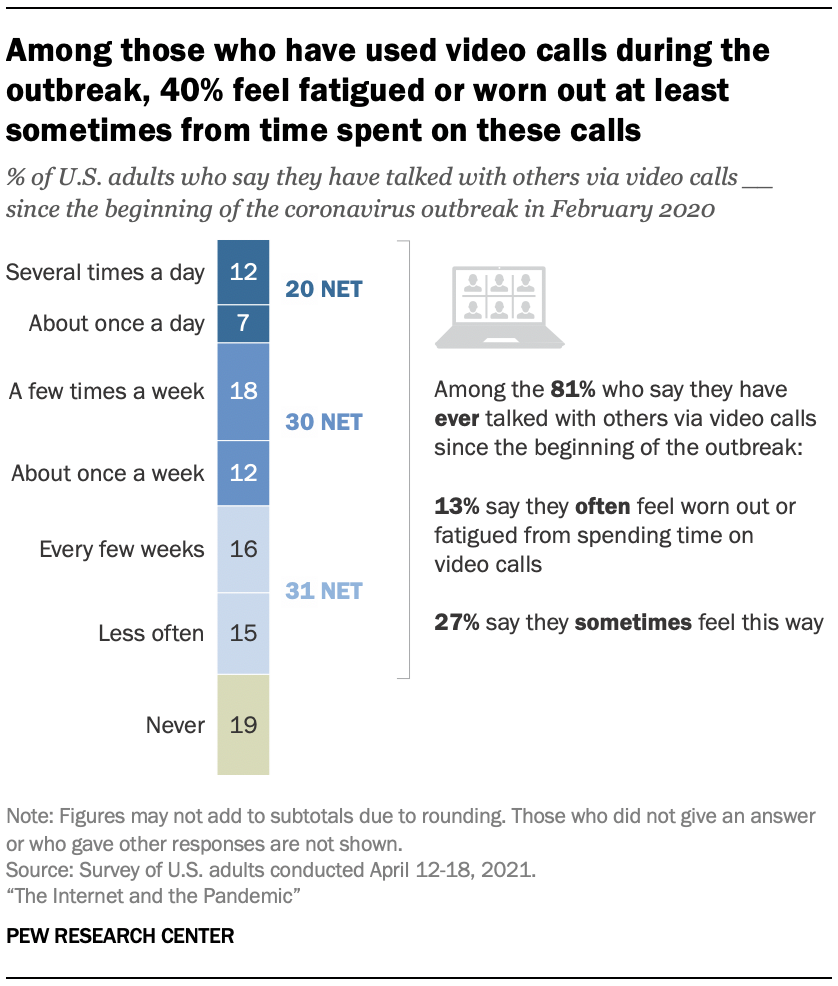

A large majority of Americans (81%) also say they talked with others via video calls at some point since the pandemic’s onset. And for 40% of Americans, digital tools have taken on new relevance: They report they used technology or the internet in ways that were new or different to them. Some also sought upgrades to their service as the pandemic unfolded: 29% of broadband users did something to improve the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connection at home since the beginning of the outbreak.

Still, tech use has not been an unmitigated boon for everyone. “ Zoom fatigue ” was widely speculated to be a problem in the pandemic, and some Americans report related experiences in the new survey: 40% of those who have ever talked with others via video calls since the beginning of the pandemic say they have felt worn out or fatigued often or sometimes by the time they spend on them. Moreover, changes in screen time occurred for Americans generally and for parents of young children . The survey finds that a third of all adults say they tried to cut back on time spent on their smartphone or the internet at some point during the pandemic. In addition, 72% of parents of children in grades K-12 say their kids are spending more time on screens compared with before the outbreak. 1

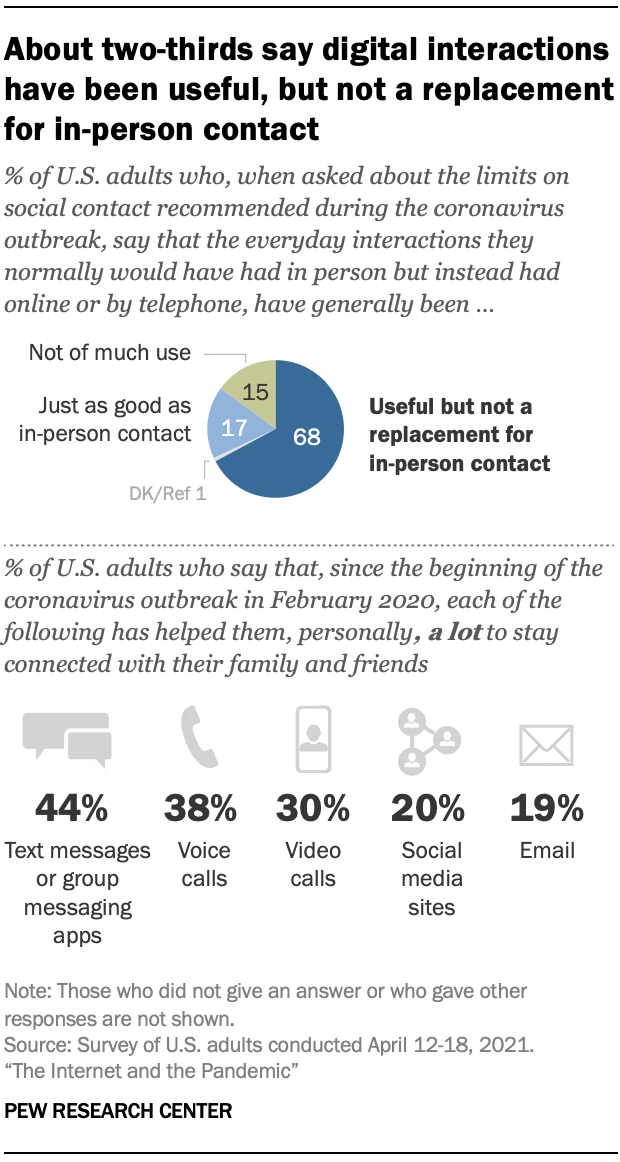

For many, digital interactions could only do so much as a stand-in for in-person communication. About two-thirds of Americans (68%) say the interactions they would have had in person, but instead had online or over the phone, have generally been useful – but not a replacement for in-person contact. Another 15% say these tools haven’t been of much use in their interactions. Still, 17% report that these digital interactions have been just as good as in-person contact.

Some types of technology have been more helpful than others for Americans. For example, 44% say text messages or group messaging apps have helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends, 38% say the same about voice calls and 30% say this about video calls. Smaller shares say social media sites (20%) and email (19%) have helped them in this way.

The survey offers a snapshot of Americans’ lives just over one year into the pandemic as they reflected back on what had happened. It is important to note the findings were gathered in April 2021, just before all U.S. adults became eligible for coronavirus vaccine s. At the time, some states were beginning to loosen restrictions on businesses and social encounters. This survey also was fielded before the delta variant became prominent in the United States, raising concerns about new and evolving variants .

Here are some of the key takeaways from the survey.

Americans’ tech experiences in the pandemic are linked to digital divides, tech readiness

Some Americans’ experiences with technology haven’t been smooth or easy during the pandemic. The digital divides related to internet use and affordability were highlighted by the pandemic and also emerged in new ways as life moved online.

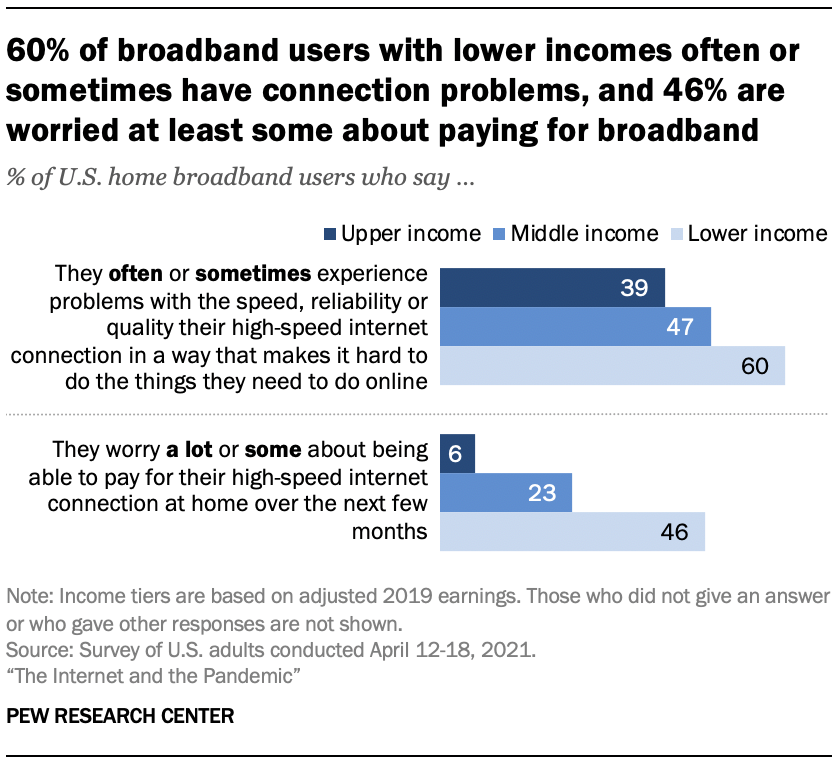

Beyond that, affordability remained a persistent concern for a portion of digital tech users as the pandemic continued – about a quarter of home broadband users (26%) and smartphone owners (24%) said in the April 2021 survey that they worried a lot or some about paying their internet and cellphone bills over the next few months.

From parents of children facing the “ homework gap ” to Americans struggling to afford home internet , those with lower incomes have been particularly likely to struggle. At the same time, some of those with higher incomes have been affected as well.

Affordability and connection problems have hit broadband users with lower incomes especially hard. Nearly half of broadband users with lower incomes, and about a quarter of those with midrange incomes, say that as of April they were at least somewhat worried about paying their internet bill over the next few months. 3 And home broadband users with lower incomes are roughly 20 points more likely to say they often or sometimes experience problems with their connection than those with relatively high incomes. Still, 55% of those with lower incomes say the internet has been essential to them personally in the pandemic.

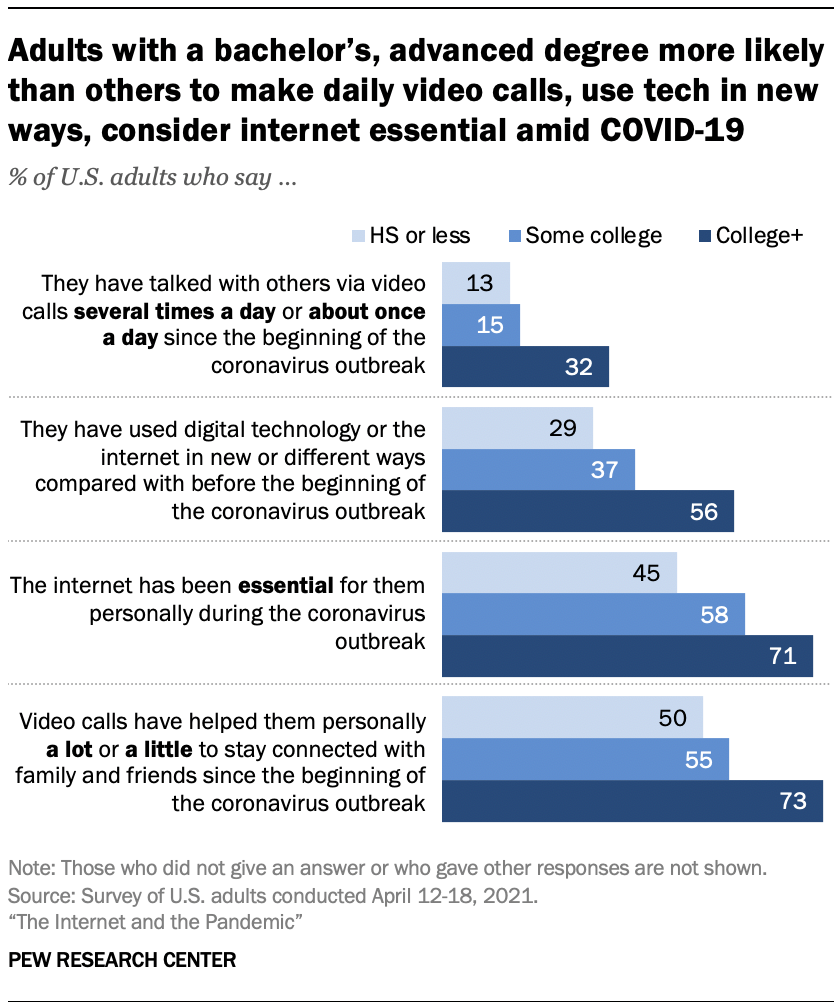

At the same time, Americans’ levels of formal education are associated with their experiences turning to tech during the pandemic.

Those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree are about twice as likely as those with a high school diploma or less formal education to have used tech in new or different ways during the pandemic. There is also roughly a 20 percentage point gap between these two groups in the shares who have made video calls about once a day or more often and who say these calls have helped at least a little to stay connected with family and friends. And 71% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more education say the internet has been essential, compared with 45% of those with a high school diploma or less.

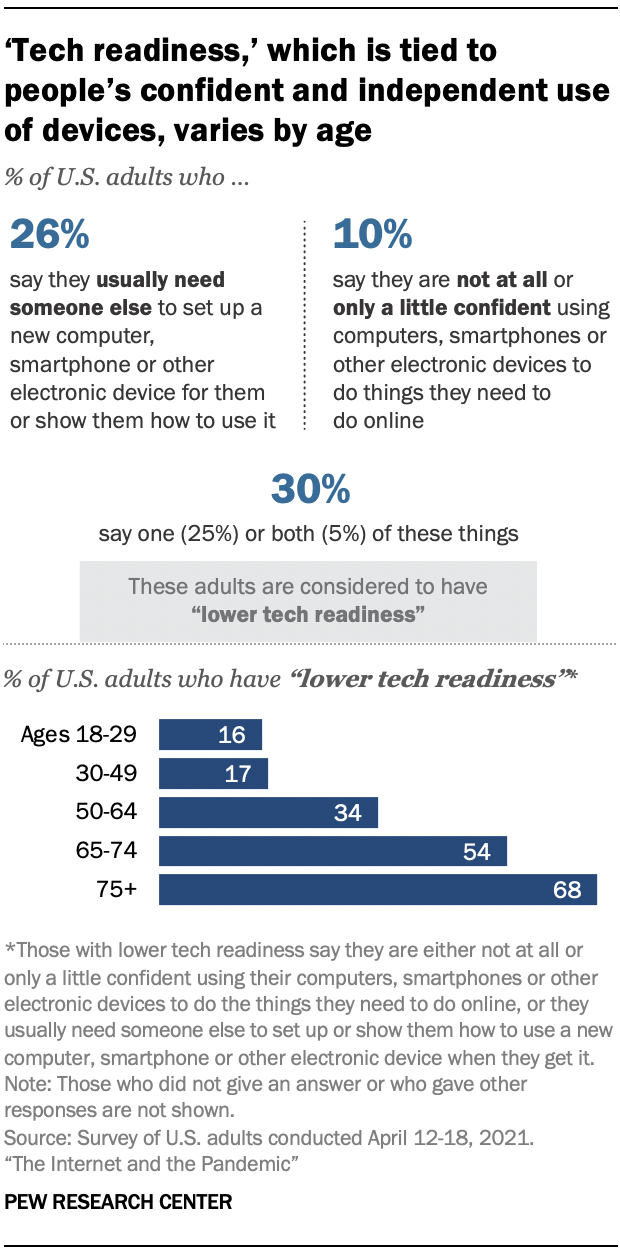

More broadly, not all Americans believe they have key tech skills. In this survey, about a quarter of adults (26%) say they usually need someone else’s help to set up or show them how to use a new computer, smartphone or other electronic device. And one-in-ten report they have little to no confidence in their ability to use these types of devices to do the things they need to do online. This report refers to those who say they experience either or both of these issues as having “lower tech readiness.” Some 30% of adults fall in this category. (A full description of how this group was identified can be found in Chapter 3. )

These struggles are particularly acute for older adults, some of whom have had to learn new tech skills over the course of the pandemic. Roughly two-thirds of adults 75 and older fall into the group having lower tech readiness – that is, they either have little or no confidence in their ability to use their devices, or generally need help setting up and learning how to use new devices. Some 54% of Americans ages 65 to 74 are also in this group.

Americans with lower tech readiness have had different experiences with technology during the pandemic. While 82% of the Americans with lower tech readiness say the internet has been at least important to them personally during the pandemic, they are less likely than those with higher tech readiness to say the internet has been essential (39% vs. 66%). Some 21% of those with lower tech readiness say digital interactions haven’t been of much use in standing in for in-person contact, compared with 12% of those with higher tech readiness.

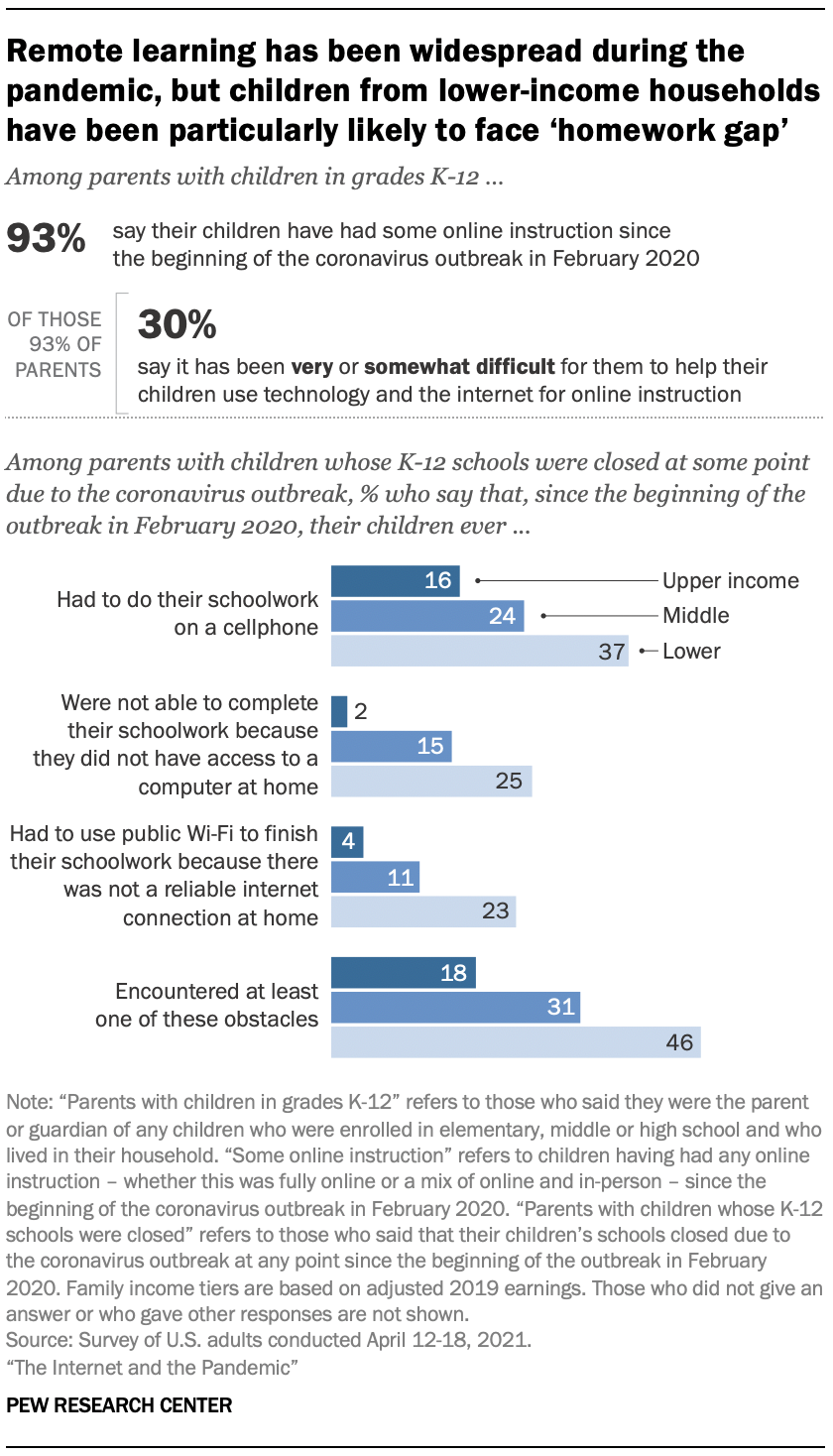

46% of parents with lower incomes whose children faced school closures say their children had at least one problem related to the ‘homework gap’

As school moved online for many families, parents and their children experienced profound changes. Fully 93% of parents with K-12 children at home say these children had some online instruction during the pandemic. Among these parents, 62% report that online learning has gone very or somewhat well, and 70% say it has been very or somewhat easy for them to help their children use technology for online instruction.

Still, 30% of the parents whose children have had online instruction during the pandemic say it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet for this.

The survey also shows that children from households with lower incomes who faced school closures in the pandemic have been especially likely to encounter tech-related obstacles in completing their schoolwork – a phenomenon contributing to the “ homework gap .”

Overall, about a third (34%) of all parents whose children’s schools closed at some point say their children have encountered at least one of the tech-related issues we asked about amid COVID-19: having to do schoolwork on a cellphone, being unable to complete schoolwork because of lack of computer access at home, or having to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

This share is higher among parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed. Nearly half (46%) say their children have faced at least one of these issues. Some with higher incomes were affected as well – about three-in-ten (31%) of these parents with midrange incomes say their children faced one or more of these issues, as do about one-in-five of these parents with higher household incomes.

Prior Center work has documented this “ homework gap ” in other contexts – both before the coronavirus outbreak and near the beginning of the pandemic . In April 2020, for example, parents with lower incomes were particularly likely to think their children would face these struggles amid the outbreak.

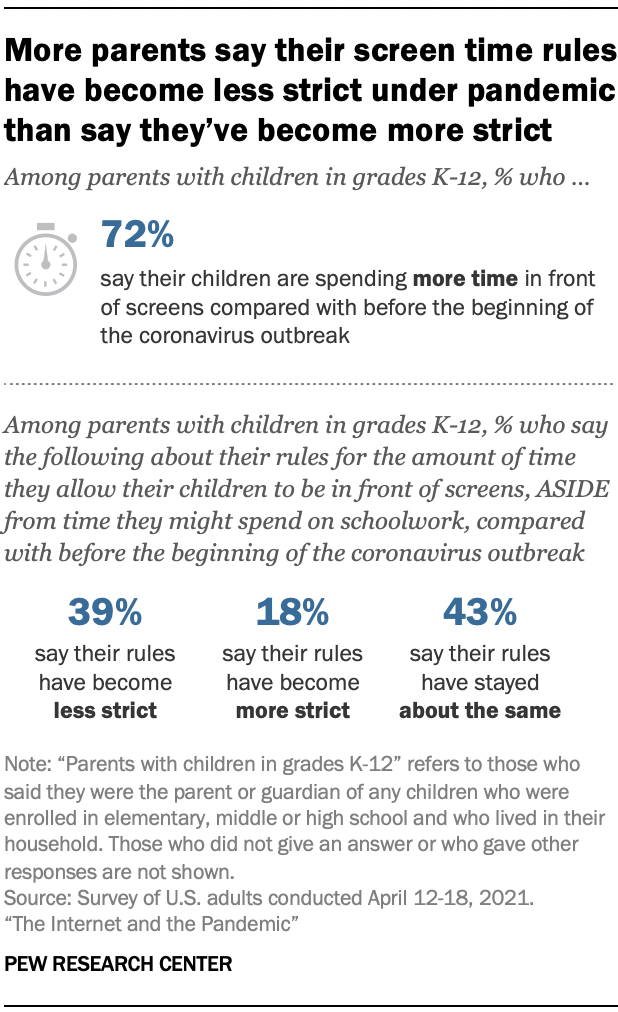

Besides issues related to remote schooling, other changes were afoot in families as the pandemic forced many families to shelter in place. For instance, parents’ estimates of their children’s screen time – and family rules around this – changed in some homes. About seven-in-ten parents with children in kindergarten through 12th grade (72%) say their children were spending more time on screens as of the April survey compared with before the outbreak. Some 39% of parents with school-age children say they have become less strict about screen time rules during the outbreak. About one-in-five (18%) say they have become more strict, while 43% have kept screen time rules about the same.

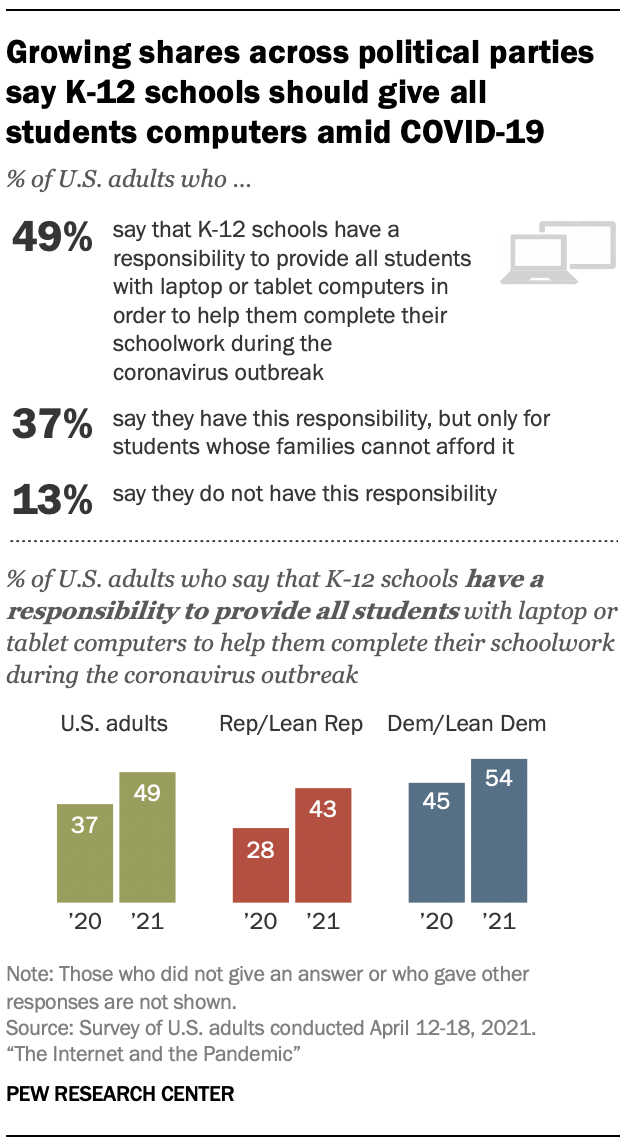

More adults now favor the idea that schools should provide digital technology to all students during the pandemic than did in April 2020

Americans’ tech struggles related to digital divides gained attention from policymakers and news organizations as the pandemic progressed.

On some policy issues, public attitudes changed over the course of the outbreak – for example, views on what K-12 schools should provide to students shifted. Some 49% now say K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork during the pandemic, up 12 percentage points from a year ago.

The shares of those who say so have increased for both major political parties over the past year: This view shifted 15 points for Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP, and there was a 9-point increase for Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say the government has this responsibility, and within the Republican Party, those with lower incomes are more likely to say this than their counterparts earning more money.

Video calls and conferencing have been part of everyday life

Americans’ own words provide insight into exactly how their lives changed amid COVID-19. When asked to describe the new or different ways they had used technology, some Americans mention video calls and conferencing facilitating a variety of virtual interactions – including attending events like weddings, family holidays and funerals or transforming where and how they worked. 5 From family calls, shopping for groceries and placing takeout orders online to having telehealth visits with medical professionals or participating in online learning activities, some aspects of life have been virtually transformed:

“I’ve gone from not even knowing remote programs like Zoom even existed, to using them nearly every day.” – Man, 54

“[I’ve been] h andling … deaths of family and friends remotely, attending and sharing classical music concerts and recitals with other professionals, viewing [my] own church services and Bible classes, shopping. … Basically, [the internet has been] a lifeline.” – Woman, 69

“I … use Zoom for church youth activities. [I] use Zoom for meetings. I order groceries and takeout food online. We arranged for a ‘digital reception’ for my daughter’s wedding as well as live streaming the event.” – Woman, 44

When asked about video calls specifically, half of Americans report they have talked with others in this way at least once a week since the beginning of the outbreak; one-in-five have used these platforms daily. But how often people have experienced this type of digital connectedness varies by age. For example, about a quarter of adults ages 18 to 49 (27%) say they have connected with others on video calls about once a day or more often, compared with 16% of those 50 to 64 and just 7% of those 65 and older.

Even as video technology became a part of life for users, many accounts of burnout surfaced and some speculated that “Zoom fatigue” was setting in as Americans grew weary of this type of screen time. The survey finds that some 40% of those who participated in video calls since the beginning of the pandemic – a third of all Americans – say they feel worn out or fatigued often or sometimes from the time they spend on video calls. About three-quarters of those who have been on these calls several times a day in the pandemic say this.

Fatigue is not limited to frequent users, however: For example, about a third (34%) of those who have made video calls about once a week say they feel worn out at least sometimes.

These are among the main findings from the survey. Other key results include:

Some Americans’ personal lives and social relationships have changed during the pandemic: Some 36% of Americans say their own personal lives changed in a major way as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Another 47% say their personal lives changed, but only a little bit. About half (52%) of those who say major change has occurred in their personal lives due to the pandemic also say they have used tech in new ways, compared with about four-in-ten (38%) of those whose personal lives changed a little bit and roughly one-in-five (19%) of those who say their personal lives stayed about the same.

Even as tech helped some to stay connected, a quarter of Americans say they feel less close to close family members now compared with before the pandemic, and about four-in-ten (38%) say the same about friends they know well. Roughly half (53%) say this about casual acquaintances.

The majority of those who tried to sign up for vaccine appointments in the first part of the year went online to do so: Despite early problems with vaccine rollout and online registration systems , in the April survey tech problems did not appear to be major struggles for most adults who had tried to sign up online for COVID-19 vaccines. The survey explored Americans’ experiences getting these vaccine appointments and reveals that in April 57% of adults had tried to sign themselves up and 25% had tried to sign someone else up. Fully 78% of those who tried to sign themselves up and 87% of those who tried to sign others up were online registrants.

When it comes to difficulties with the online vaccine signup process, 29% of those who had tried to sign up online – 13% of all Americans – say it was very or somewhat difficult to sign themselves up for vaccines at that time. Among five reasons for this that the survey asked about, the most common major reason was lack of available appointments, rather than tech-related problems. Adults 65 and older who tried to sign themselves up for the vaccine online were the most likely age group to experience at least some difficulty when they tried to get a vaccine appointment.

Tech struggles and usefulness alike vary by race and ethnicity. Americans’ experiences also have varied across racial and ethnic groups. For example, Black Americans are more likely than White or Hispanic adults to meet the criteria for having “lower tech readiness.” 6 Among broadband users, Black and Hispanic adults were also more likely than White adults to be worried about paying their bills for their high-speed internet access at home as of April, though the share of Hispanic Americans who say this declined sharply since April 2020. And a majority of Black and Hispanic broadband users say they at least sometimes have experienced problems with their internet connection.

Still, Black adults and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say various technologies – text messages, voice calls, video calls, social media sites and email – have helped them a lot to stay connected with family and friends amid the pandemic.

Tech has helped some adults under 30 to connect with friends, but tech fatigue also set in for some. Only about one-in-five adults ages 18 to 29 say they feel closer to friends they know well compared with before the pandemic. This share is twice as high as that among adults 50 and older. Adults under 30 are also more likely than any other age group to say social media sites have helped a lot in staying connected with family and friends (30% say so), and about four-in-ten of those ages 18 to 29 say this about video calls.

Screen time affected some negatively, however. About six-in-ten adults under 30 (57%) who have ever made video calls in the pandemic say they at least sometimes feel worn out or fatigued from spending time on video calls, and about half (49%) of young adults say they have tried to cut back on time spent on the internet or their smartphone.

- Throughout this report, “parents” refers to those who said they were the parent or guardian of any children who were enrolled in elementary, middle or high school and who lived in their household at the time of the survey. ↩

- People with a high-speed internet connection at home also are referred to as “home broadband users” or “broadband users” throughout this report. ↩

- Family incomes are based on 2019 earnings and adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and for household sizes. Middle income is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for all panelists on the American Trends Panel. Lower income falls below that range; upper income falls above it. ↩

- A separate Center study also fielded in April 2021 asked Americans what the government is responsible for on a number of topics, but did not mention the coronavirus outbreak. Some 43% of Americans said in that survey that the federal government has a responsibility to provide high-speed internet for all Americans. This was a significant increase from 2019, the last time the Center had asked that more general question, when 28% said the same. ↩

- Quotations in this report may have been lightly edited for grammar, spelling and clarity. ↩

- There were not enough Asian American respondents in the sample to be broken out into a separate analysis. As always, their responses are incorporated into the general population figures throughout this report. ↩

Sign up for our Internet, Science and Tech newsletter

New findings, delivered monthly

Report Materials

Table of contents, 34% of lower-income home broadband users have had trouble paying for their service amid covid-19, experts say the ‘new normal’ in 2025 will be far more tech-driven, presenting more big challenges, what we’ve learned about americans’ views of technology during the time of covid-19, key findings about americans’ views on covid-19 contact tracing, how americans see digital privacy issues amid the covid-19 outbreak, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

How the Pandemic Has Changed Our Relationship With Technology

From virtual theater to smartphone-driven distress, covid-19 is changing the digital landscape for what appears to be both better and worse..

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in the spring of 2020, Americans became more isolated than ever. Suddenly work, social events and live entertainment migrated from the realm world onto digital platforms. Between social media, video calls and entertainment, people around the world began to spend a staggering amount of their waking lives in front of screens.

While the deleterious effects of compulsive technology use are often cited, the same platforms have also allowed many people to stay social, stimulated and productive while stuck at home. In a 2021 Pew Research Center survey , 90 percent of Americans said that the internet has been important or essential to them during the pandemic. A majority of respondents said video calls had helped them stay connected with friends and family.

Even after the initial wave of COVID-19 waned, Americans continued to use the internet at unprecedented rates. In a second Pew study from last year, nearly half of respondents between 18 and 29 years old reported using the internet “almost constantly.”

So after two years of excessive screen time, how has our collective internet obsession actually affected our health?

Problematic Use

Long before COVID-19, scientists had already recognized the serious impacts of technology misuse. “Going back 15 years ago, we found that problematic use of the internet was associated with a number of negative health outcomes,” says Marc Potenza, a psychiatrist at Yale Medical School.

In 2019, the World Health Organization adopted the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). It included two emerging disorders that stem from compulsive online behaviors: internet gaming disorder and gambling disorder (predominantly online). Experts argue that online shopping, pornography and social media may cause addictive disorders as well. “During the onset of the pandemic, there seemed to be increases in online engagement for all of these behaviors," Potenza adds.

Currently, there isn’t enough data to make any sweeping generalizations about how the pandemic has affected internet addictions. But the anecdotal evidence is alarming: In the week following the WHO’s official declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic, the website PornHub experienced an 11.6 percent rise in traffic worldwide, with a particular increase in use in the wee hours of the morning. “It suggests that there might have been an increase in insomnia and disregulated pornography viewing,” Potenza speculates.

Addiction Versus High-Frequency Use

A long-term study that analyzed problematic gaming and smartphone use in Chinese schoolchildren hints at a more complex story. While compulsive gaming was associated with psychological distress pre-pandemic, the two were not correlated after the onset of COVID-19. The results, published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine last March, support a preliminary theory that gaming might actually provide an avenue to cope with loneliness and emotional stress during periods of isolation.

Interestingly, the same research noted that problematic smartphone use was increasingly associated with psychological distress after the onset of the pandemic. This result points towards another theory — that social media can exacerbate COVID-19 anxiety . This effect, coupled with the well-documented link between social media and depression, may have led to the outcomes observed in the study.

Overall, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of discerning frequent internet use from addictive behaviors. While many people use the internet extensively during their waking hours, only a small percentage experience the pitfalls of addiction. “For a disorder to be present there needs to be some sort of impairment in a major area of life functioning,” Potenza says. “It’s important to try to disentangle high-frequency use from unhealthy and problematic use.”

Silver Linings

Despite the downfalls of isolation, crises can also inspire creativity. For example, the pandemic spurred a virtual reality boom in the art world.

This technology came in handy in March 2020, when England’s Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) was in the early stages of a production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” As the pandemic shuttered venues across the U.K., they were forced to quickly find ways to adapt. The company worked feverishly with partners in tech to create a prototypical VR theater production. Though the complexity of Shakespeare’s original story was boiled down to an eight-person cast and a single narrative strand, the result was highly immersive. “We had to find a way to embody this narrative,” says Sarah Ellis, RSC’s director of digital development

In the final production, the actors' movements and speech were tracked and projected into a virtual forest. Audience members entered the fictional realm as fireflies and buzzed around the Shakespearean sprites’ heads as they propelled the story to an inevitable conclusion.

The performance reached the widest audience of any RSC production to date. The 65,000 attendees hailed from 92 countries and 76 percent of them were at their first-ever RSC production. Ellis was elated. “We often talk about new audiences, but we don’t talk about new content,” she says. “It was amazing to see the younger generation show up.”

While COVID-19 has stuck around for nearly two years, the broader impacts on our collective habits, mental health and culture remain unclear. But it is evident that the pandemic changed our relationship to technology — for better and worse.

- electronics

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: Getty Images

COVID-19 is transforming how companies use digital technology

How companies approach sales has changed more in the past five months than it has in the past five years, says carey business school associate professor joël le bon.

By Patrick Ercolano

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced millions of people to work from home, making workers and corporations alike more dependent on the digital technology that has long enabled them to handle both personal and professional tasks from their smartphones, laptops, and personal computers.

Joël Le Bon has been paying particularly close attention to these rapid developments. The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School associate professor specializes in the commercial applications of digital technology, including its use in sales, marketing, and management. COVID-19's impact on the digital sphere, he notes, has been extraordinary.

"I used to say that with modern digital sales capabilities, sales changed more in the past five years than in the past 50 years. I should say now that sales changed more in the past five months than in the past five years," he says.

With Carey Professor Andrew Ching , Le Bon established the business school's Science of Digital Business Development Initiative , launched just months before the pandemic emerged. The coronavirus has added urgency to the work and mission of the initiative, says Le Bon.

"Advancing the research, education, and practice of digital business development as organizations shift their strategic, marketing, and sales activities makes the Science of Digital Business Development Initiative even more critical for the future of sales, leadership, and work," he says.

The Carey Business School reached out to Le Bon for more insights about some of the ways the pandemic has affected the world of digital business.

The Science of Digital Business Development Initiative aims to show business organizations how to thrive in a digital economy. How has this goal, or the means of achieving it, been affected by the pandemic?

The initiative's mission is to advance the research, education, and practice aspects of digital business development, offer a leading network to address the profound impact of digital transformation and open new paths of opportunity for the future of work in the digital economy. The pandemic has made our mission and goal even more relevant by changing organizations' perspectives on work, leadership, and business interactions with their customers with a radical shift to digital capabilities.

From an organizational standpoint, working and leading from home requires the leverage of digital capabilities, thus raising significant new challenges such as redefining interpersonal engagement, communication, developing people, and sustaining and measuring individuals' and teams' productivity. Interestingly, from a go-to-market standpoint, similar challenges apply in terms of redefining interpersonal engagement, communication, developing relationships with clients, and sustaining and measuring value-creating growth for customers.

Although several technologies already exist to support organizations' digital shift regarding work, leadership, and business interactions, the offering is quite complex and will grow substantially. For example, for the marketing and sales functions, digital capabilities in areas such as virtual offices, video conferencing, messaging and chat, project management, collaborative design, sales, and customer engagements and analytics can truly facilitate collaborative endeavors to engage and serve the customers. Yet, this implies that organizations profoundly rethink their culture, structure, process, and competency models for better digital engagements and with diverse stakeholders.

What types of business and industries do you think will benefit most in the wake of this crisis? And which ones will suffer most?

When it comes to how value is created, it is important to recognize that value is based on content, or what is offered; context, or how it is offered; and cadence, or when it is offered. However, the extent to which that value is mainly provided through a physical experience or a digital experience helps recognize which industries can suffer or benefit the most from this crisis.

For example, in industries such as airlines and transportation, leisure, hospitality, tourism, entertainment, sports, retail, logistics, or higher education, value is mainly created through a physical experience, and thus cannot be easily transformed and offered as digitized content and distributed through the Internet. However, other industries where value can be created through digital experiences easily transformed and offered, as digitized content distributed through the Internet, will benefit from the crisis. Examples are media, communication, telecommunications, e-commerce, and information technology, to name a few.

Do you expect a significant long-term or perhaps even permanent increase in the number of people working remotely, away from the traditional office setting? If so, what would be the pros and cons of such arrangements?

Yes, yet not with the same magnitude in all industries, and for all functions. The technologies to support remote and virtual work already exist. However, the pandemic has intensified the need for a digital shift from a mindset perspective for organizations and individuals, who are thus encouraged to approach work, interpersonal engagement, and communication differently.

The Global Workplace Analytics consulting firm has shown that a typical employer can save an average of $11,000 per half-time telecommuter per year, in terms of increased productivity, lower real estate costs, reduced absenteeism, and turnover. Further, some positive outcomes at the individual level pertain to more independence and autonomy, work flexibility, or time management.

However, some discrepancies exist between employees' and employers' perceived main struggles. From an employee standpoint, the most significant concerns relate to unplugging after work, loneliness, and collaborating and communicating. From a manager standpoint, the concerns relate to reduced employee productivity, reduced employee focus, and reduced team cohesiveness. Interestingly, if employees struggle to unplug after work, managers should be less concerned about productivity, and more about distress and communication and their employees' mental health.

How do you think the COVID-19 disruption will affect the education field, especially in terms of how the "product" and services will be delivered?

Industries that can suffer the most from the crisis, such as higher education, can also benefit the most of the transformative changes the crisis initiated, should they build their business models and value proposition on the radical shift that digital capabilities offer.

Knowledge can be easily produced, transformed, and distributed through digital capabilities. Yet the question of the credibility and reliability of the source of knowledge is of paramount importance; but at what price for the colleges, and cost for the students? The problem with digital-based knowledge as a raw material to be transformed and distributed is that it can be commoditized because of being readily accessible, thus raising the question of price and cost of its accessibility. For this reason, such value should not only be protected at the content level with constant research to advance knowledge, but mainly at the context and cadence levels through the transformation and distribution of advanced knowledge. In fact, this is where the business models and value proposition of higher education should shift, and shift fast.

Before COVID-19, the professor was the main channel enabler for transforming and distributing knowledge content in the context of the classroom, and at the course cadence. Tomorrow, technology-enabled professors will make the difference for the students, beyond commoditized readily accessible content. Consequently, the perceived value of digital college-based knowledge and degrees will shift to well-designed and well-distributed content through virtual, remote experience, and innovative instructions. As students may question the perceived value of college-based knowledge and degrees if they cannot enjoy the physical experience on being on a campus and learn in the classroom with their peers, colleges will need to radically change their very approach to digitally transformed and distributed instructions. In fact, this may also facilitate the transfer of knowledge and education at scale to more students, from a volume perspective.

In higher education, there cannot be a new normal if we only wish to come back to normalcy.

As a marketing professor, what's your view of how advertisers have responded to the pandemic? For example, TV ads that express empathy during a 30-second product pitch—is that effective marketing, or might it run the risk of seeming insincere and calculating?

Effective marketing makes customers understand the value they receive from a product or service. Unauthentic, insincere, and calculating marketing messages do not go a long way, as the most important thing for a company is not the first purchase, but repeated purchases. If such messages do not intrinsically belong to the very values of the brand, customers will not be fooled.

How might the pandemic affect the ways in which sales are conducted?

"Inside sales"—remote and virtual selling where sales professionals use digital information and communication technologies and social selling platforms (e.g., LinkedIn) to connect with, and engage, customers—is the fastest-growing title in the sales industry. It expands at a much higher rate than outside sales, and is regarded as the future of sales. Contrary to outside sales that are performed face-to-face in the field, inside sales also reflects modern buyers' expectations in their will to use the Internet and social media platforms rather than salespeople as effective sources of information and communication.

COVID-19 made organizations who did not have an inside sales force go to inside sales overnight. The pandemic thus accelerated the digital transformation of sales organizations, and such transformation will remain, because inside sales is an effective go-to-market and go-to-customers strategy. There are four main reasons for this, namely: cost, productivity, training, and motivation.

From a cost standpoint, an inside salesperson costs one-third the cost of an outside salesperson. From a productivity standpoint, 30 inside salespeople are likely to sell more than 10 outside salespeople, at the same cost to the company. From a training standpoint, inside sales structures are centralized, which allows inside salespeople to be trained easily and quickly on new product announcements, acquisitions, or internal documents such as compensation plans. And from a motivation standpoint, since inside sales structures leverage powerful sales technologies for interpersonal and customer engagement, communication, and the managing and sustaining of individuals' and teams' productivity, this facilitates the leading of inside sales organizations.

Sales is a struggle for everyone, but it is less so for those who understand it, and know how to leverage digital sales capabilities. In fact, digital sales transformation is about making technology focus on the process, so you can focus on the customer.

Posted in Voices+Opinion , Politics+Society

Tagged business , marketing

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

- All Articles

- Education Technology

- Industry News

- Op-Ed Submission Guidelines

- Write For Us

How Technology Has Helped Students Survive During COVID-19

By elearning inside, december 07, 2020.

The onset of the global pandemic has highlighted a series of new social changes and restrictions. But with it, a whole new set of hardware and software technology has come to help us cope with the new normal. During the beginning of the lockdown a few months ago, businesses had to adapt quickly to survive. Millions of employees began working from home across the globe, and shoppers could not enjoy shopping in stores. However, despite the changes and challenges of COVID-19, a host of other sectors are thriving. This article explores how technology has transformed our daily lives and allowed us to cope during the pandemic.

Education Tools

Technology has changed education in America . When the world was hit by coronavirus and countries went on lockdown, all schools had to close immediately to avoid spreading the virus. Teachers had to find ways to communicate with their students because we are unsure when the pandemic will end. A few months ago, what was impossible has become a reality for many, and educational software tools allow students and teachers to communicate and learn.

One of the biggest challenges for distance learning is that discussions in classrooms and communication are more difficult when students and teachers are not in the same classroom. Most of the tasks must also be driven by self-direction, and it may be difficult for younger students to focus on while learning.

This is where teaching management systems like Google classrooms and Canvas, and even virtual reality have come into play and mitigated the issue and has helped support teachers in directing their students better. Virtual teaching was borne out of a need during the coronavirus pandemic. Most schools have adopted this new way of learning, and even if they go back to the classroom, some will still use online learning and blend it into their curriculum even after the pandemic.

Remote Working Technology

It is no secret that the usual workplace has changed forever, and what you used to know as regular working days have changed entirely now that you can do them all from home. As your work schedule has been altered, the technologies you used to work with have also changed.

Technologies like Zoom saw their users rise from 10million to 200million per day as more people started using video communication software to communicate with families and colleagues more than ever before. Microsoft teams, just like Zoom, has seen a large increase in the number of users. It’s mainly used for workplace meetings and communications.

As the pandemic continues to spread across the World and the uncertainty continues, more and more people are getting used to working from home, and software like Zoom makes work easier for them to communicate with each other.

Financial Technology

Another area that has seen a boost in usage during the pandemic is financial technologies (FinTech). FinTech services have become more popular as a way to buy and sell goods digitally. More than half of the World’s population is now practicing self-isolation. This means that local businesses, casinos, restaurants, and whatnot are closed down or minimizing the number of people who can come into their premises.

However, with the development of FinTech, people can order their things online and have them delivered to their homes. You can order food, grocery, and anything you need and have it delivered to your doorstep. This is only possible because different financial technologies have made money transfer safe and secure.

Internet of Things (IoT)

Internet of things devices are now found in most households , from smart speaker devices to yoga mats and even toasters and fridges. Developers see an opportunity to incorporate digital transformations in homes. The use of such devices has increased during the pandemic period as more people are looking for home convenience.

Internet of Things devices can also be used in the fight against COVID-19. Researchers suggest that an IoT enabled healthcare system can monitor COVID-19 patients by implementing an interconnected network. The technology can help increase patient satisfaction and reduce the readmission rate in hospitals. It can also be used to gather patient information remotely for assessment and recommendations.

IoT has also helped businesses and has had a positive impact on their ability to function during the pandemic. It has also helped employees while working from home, freed up their time, and has a significant return on investment for most businesses.

Drone Technology

During the pandemic, many countries tried to take advantage of drone technology in different scenarios. Some countries in Africa, like Malawi, Rwanda, and Ghana, are using drones for transportation and delivery purposes during COVID-19. They would deliver and pick up medical supplies to reduce transportation time and minimize infection and exposure risk.

Companies like Amazon are also utilizing drone technology, granted permission by the US government to start a trial with a drone delivery service. In Ireland, Tesco was given permission to start a delivery grocery service drone, which cut delivery service time, freed delivery drivers, and helped vulnerable customers during the pandemic.

The technology has also seen applications in other industries besides E-commerce. NHS Clinical Entrepreneur Programme is running a project to have medical supplies delivered between hospitals across the UK to cut delivery time and free up human resources.

There have also been media reports of the use of drone technology for aerial spraying disinfectant in some public places to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus. Countries that used drones to spray public areas were the UAE, China, Spain, and South Korea. Some companies even claim to have been able to cover around 3km of spraying.

Several law enforcement agencies and public safety organizations around the World have used drones to survey public spaces and to enforce quarantine messages over loudspeakers, and tracking non-compliant citizens. The use of drones to send out messages reduces the possibility of responders directly contacting a potentially infected population. Some academic groups even used drone technology to conduct symptoms tracing, enabled by thermal imagery and artificial intelligence.

Drone tech has been utilized across various industries, including the military, oil and gas, and emergency services.

Featured Image: This Is Engineering, Unsplash.

This High School CS Club, with Help from DTML, Created an Online Literacy Game

University of Colorado (CU Online) Announces Online Degree in Business Administration

4 Tips to Help You Get into Your Preferred College

Dr. Camille Preston on Hacking Your Training

Study Suggests Online Students Communicate Better with Peers and Instructors

Where to Buy Stationery: Online Vs. Offline Shops

No comments, leave a reply, most popular post.

Important notice for administrators: The WordPress Popular Posts "classic" widget is going away!

This widget has been deprecated and will be removed in version 7.0 to be released sometime around June 2024. Please use either the WordPress Popular Posts block or the wpp shortcode instead.

AI in Education: the Pros...

Learning tips for student..., higher education: using a..., online math and english g..., how elearning transforms..., the 5 most common challen..., how technology has helped..., 10 most important soft sk..., how universities make and..., why do so many parents op....

© 2023 eLearningInside.com All Rights Reserved.

- Share full article

Advertisement

The Virus Changed the Way We Internet

By Ella Koeze and Nathaniel Popper April 7, 2020

Stuck at home during the coronavirus pandemic, with movie theaters closed and no restaurants to dine in, Americans have been spending more of their lives online.

But a New York Times analysis of internet usage in the United States from SimilarWeb and Apptopia, two online data providers, reveals that our behaviors shifted, sometimes starkly, as the virus spread and pushed us to our devices for work, play and connecting.

We are looking to connect and entertain ourselves, but are turning away from our phones

Facebook.com

First U.S. Covid-19 death

Average daily traffic

Netflix.com

YouTube.com

With nearly all public gatherings called off, Americans are seeking out entertainment on streaming services like Netflix and YouTube, and looking to connect with one another on social media outlets like Facebook.

In the past few years, users of these services were increasingly moving to their smartphones, creating an industrywide focus on mobile. Now that we are spending our days at home, with computers close at hand, Americans appear to be remembering how unpleasant it can be to squint at those little phone screens.

Facebook, Netflix and YouTube have all seen user numbers on their phone apps stagnate or fall off as their websites have grown, the data from SimilarWeb and Apptopia indicates. SimilarWeb and Apptopia both draw their traffic numbers from several independent sources to create data that can be compared across the internet.

With the rise of social distancing, we are seeking out new ways to connect, mostly through video chat

Google Duo (app)

Nextdoor.com (web)

Houseparty (app)

While traditional social media sites have been growing, it seems that we want to do more than just connect through messaging and text — we want to see one another. This has given a big boost to apps that used to linger in relative obscurity, like Google’s video chatting application, Duo, and Houseparty, which allows groups of friends to join a single video chat and play games together.

We have also grown much more interested in our immediate environment, and how it is changing and responding to the virus and the quarantine measures. This has led to a renewed interest in Nextdoor, the social media site focused on connecting local neighborhoods.

We have suddenly become reliant on services that allow us to work and learn from home

Daily app sessions for popular remote work apps.

Microsoft Teams

Unlimited Proxy

Hangouts Meet by Google

Google Classroom

VPN Super Unlimited Proxy

The offices and schools of America have all moved into our basements and living rooms. Nothing is having a more profound impact on online activity than this change. School assignments are being handed out on Google Classroom. Meetings are happening on Zoom, Google Hangouts and Microsoft Teams. The rush to these services, however, has brought new scrutiny on privacy practices .

The search for updates on the virus has pushed up readership for local and established newspapers, but not partisan sites

Percent change in average monthly u.s. traffic.

Local News Sites

sf c hroni c l e . c om

seattletime s . c om

b oston g lo b e . c om

b ea c onjou r nal. c om

Large Media Organizations

c n b c . c om

n ytime s . c om

w ashin g ton p ost. c om

foxnews.com

Partisan Sites

d aily k o s . c om

in f o w ar s . c om

free b ea c on. c om

b reit b a r t. c om

t r uth d i g . c om

d aily c alle r . c om

Amid the uncertainty about how bad the outbreak could get — there are now hundreds of thousands of cases in the United States , with the number of dead multiplying by the day — Americans appear to want few things more than the latest news on the coronavirus .

Among the biggest beneficiaries are local news sites, with huge jumps in traffic as people try to learn how the pandemic is affecting their hometowns.

Americans have also been seeking out more established media brands for information on the public health crisis and its economic consequences. CNBC, the business news site, has seen readership skyrocket. The websites for The New York Times and The Washington Post have both grown traffic more than 50 percent over the last month, according to SimilarWeb.

The desire for the latest facts on the virus appears to be curbing interest in the more opinionated takes from partisan sites, which have defined the media landscape in recent years. Publications like The Daily Caller, on the right, and Truthdig on the left, have recorded stagnant or falling numbers. Even Fox News has seen disappointing numbers compared to other large outlets.

Beating all of the news sites, in terms of increased popularity, is the home page for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , which has been attracting millions of readers after previously having almost none. Over time, readers have also looked to more ambitious efforts to quantify the spread of the virus, like the one produced by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center .

wiki p e d ia.org

coronavirus.jhu.edu

The single-minded focus on the virus has crowded out the broad curiosity that draws people to sites like Wikipedia, which had declining numbers before a recent uptick, data from SimilarWeb shows.

Video games have been gaining while sports have lost out

TikTok (app)

Twitch.tv (web)

ESPN.com (web)

With all major-league games called off, there hasn’t been much sports to consume beyond marble racing and an occasional Belarusian soccer match . Use of ESPN’s website has fallen sharply since late January, according to SimilarWeb.

At the same time, several video game sites have had surges in traffic, as have sites that let you watch other people play. Twitch, the leading site for streaming game play, has had traffic shoot up 20 percent.

TikTok, the mobile app filled with short clips of pranks and lip-syncing, was taking off before the coronavirus outbreak and it has continued its steady ascent ever since. It can be nice to see that at least some things remain unchanged by the crisis.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Promises and Pitfalls of Technology

Politics and privacy, private-sector influence and big tech, state competition and conflict, author biography, how is technology changing the world, and how should the world change technology.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Josephine Wolff; How Is Technology Changing the World, and How Should the World Change Technology?. Global Perspectives 1 February 2021; 2 (1): 27353. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2021.27353

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Technologies are becoming increasingly complicated and increasingly interconnected. Cars, airplanes, medical devices, financial transactions, and electricity systems all rely on more computer software than they ever have before, making them seem both harder to understand and, in some cases, harder to control. Government and corporate surveillance of individuals and information processing relies largely on digital technologies and artificial intelligence, and therefore involves less human-to-human contact than ever before and more opportunities for biases to be embedded and codified in our technological systems in ways we may not even be able to identify or recognize. Bioengineering advances are opening up new terrain for challenging philosophical, political, and economic questions regarding human-natural relations. Additionally, the management of these large and small devices and systems is increasingly done through the cloud, so that control over them is both very remote and removed from direct human or social control. The study of how to make technologies like artificial intelligence or the Internet of Things “explainable” has become its own area of research because it is so difficult to understand how they work or what is at fault when something goes wrong (Gunning and Aha 2019) .

This growing complexity makes it more difficult than ever—and more imperative than ever—for scholars to probe how technological advancements are altering life around the world in both positive and negative ways and what social, political, and legal tools are needed to help shape the development and design of technology in beneficial directions. This can seem like an impossible task in light of the rapid pace of technological change and the sense that its continued advancement is inevitable, but many countries around the world are only just beginning to take significant steps toward regulating computer technologies and are still in the process of radically rethinking the rules governing global data flows and exchange of technology across borders.

These are exciting times not just for technological development but also for technology policy—our technologies may be more advanced and complicated than ever but so, too, are our understandings of how they can best be leveraged, protected, and even constrained. The structures of technological systems as determined largely by government and institutional policies and those structures have tremendous implications for social organization and agency, ranging from open source, open systems that are highly distributed and decentralized, to those that are tightly controlled and closed, structured according to stricter and more hierarchical models. And just as our understanding of the governance of technology is developing in new and interesting ways, so, too, is our understanding of the social, cultural, environmental, and political dimensions of emerging technologies. We are realizing both the challenges and the importance of mapping out the full range of ways that technology is changing our society, what we want those changes to look like, and what tools we have to try to influence and guide those shifts.

Technology can be a source of tremendous optimism. It can help overcome some of the greatest challenges our society faces, including climate change, famine, and disease. For those who believe in the power of innovation and the promise of creative destruction to advance economic development and lead to better quality of life, technology is a vital economic driver (Schumpeter 1942) . But it can also be a tool of tremendous fear and oppression, embedding biases in automated decision-making processes and information-processing algorithms, exacerbating economic and social inequalities within and between countries to a staggering degree, or creating new weapons and avenues for attack unlike any we have had to face in the past. Scholars have even contended that the emergence of the term technology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries marked a shift from viewing individual pieces of machinery as a means to achieving political and social progress to the more dangerous, or hazardous, view that larger-scale, more complex technological systems were a semiautonomous form of progress in and of themselves (Marx 2010) . More recently, technologists have sharply criticized what they view as a wave of new Luddites, people intent on slowing the development of technology and turning back the clock on innovation as a means of mitigating the societal impacts of technological change (Marlowe 1970) .

At the heart of fights over new technologies and their resulting global changes are often two conflicting visions of technology: a fundamentally optimistic one that believes humans use it as a tool to achieve greater goals, and a fundamentally pessimistic one that holds that technological systems have reached a point beyond our control. Technology philosophers have argued that neither of these views is wholly accurate and that a purely optimistic or pessimistic view of technology is insufficient to capture the nuances and complexity of our relationship to technology (Oberdiek and Tiles 1995) . Understanding technology and how we can make better decisions about designing, deploying, and refining it requires capturing that nuance and complexity through in-depth analysis of the impacts of different technological advancements and the ways they have played out in all their complicated and controversial messiness across the world.