- 0 Shopping Cart

Hurricane Katrina Case Study

Hurricane Katrina is tied with Hurricane Harvey (2017) as the costliest hurricane on record. Although not the strongest in recorded history, the hurricane caused an estimated $125 billion worth of damage. The category five hurricane is the joint eight strongest ever recorded, with sustained winds of 175 mph (280 km/h).

The hurricane began as a very low-pressure system over the Atlantic Ocean. The system strengthened, forming a hurricane that moved west, approaching the Florida coast on the evening of the 25th August 2005.

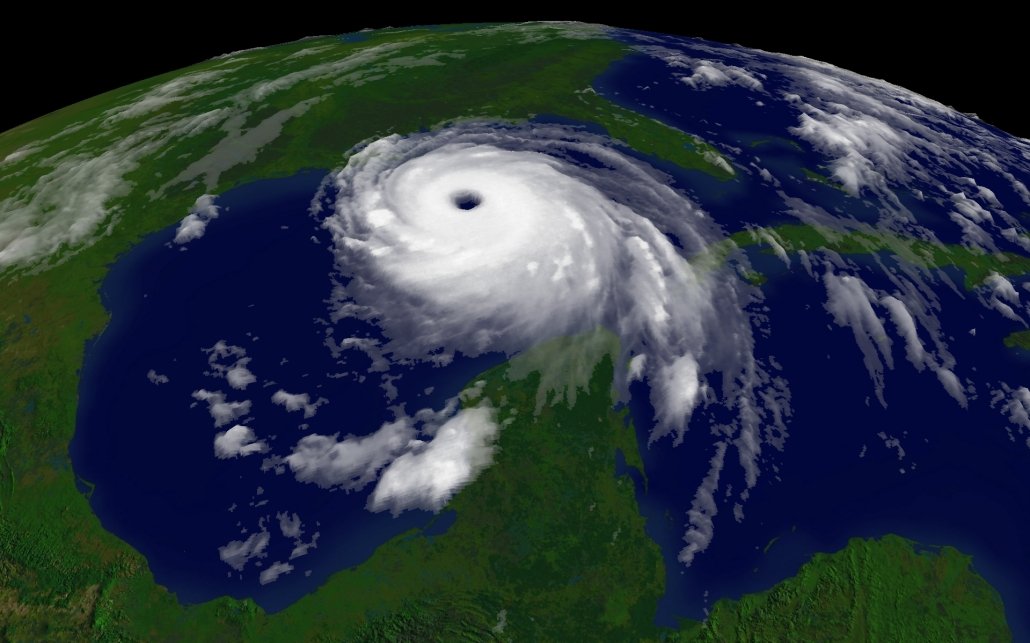

A satellite image of Hurricane Katrina.

Hurricane Katrina was an extremely destructive and deadly Category 5 hurricane. It made landfall on Florida and Louisiana, particularly the city of New Orleans and surrounding areas, in August 2005, causing catastrophic damage from central Florida to eastern Texas. Fatal flaws in flood engineering protection led to a significant loss of life in New Orleans. The levees, designed to cope with category three storm surges, failed to lead to catastrophic flooding and loss of life.

What were the impacts of Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina was a category five tropical storm. The hurricane caused storm surges over six metres in height. The city of New Orleans was one of the worst affected areas. This is because it lies below sea level and is protected by levees. The levees protect the city from the Mississippi River and Lake Ponchartrain. However, these were unable to cope with the storm surge, and water flooded the city.

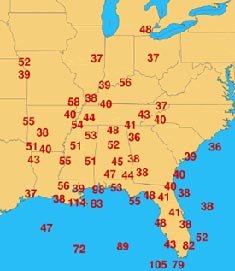

$105 billion was sought by The Bush Administration for repairs and reconstruction in the region. This funding did not include potential interruption of the oil supply, destruction of the Gulf Coast’s highway infrastructure, and exports of commodities such as grain.

Although the state made an evacuation order, many of the poorest people remained in New Orleans because they either wanted to protect their property or could not afford to leave.

The Superdome stadium was set up as a centre for people who could not escape the storm. There was a shortage of food, and the conditions were unhygienic.

Looting occurred throughout the city, and tensions were high as people felt unsafe. 1,200 people drowned in the floods, and 1 million people were made homeless. Oil facilities were damaged, and as a result, the price of petrol rose in the UK and USA.

80% of the city of New Orleans and large neighbouring parishes became flooded, and the floodwaters remained for weeks. Most of the transportation and communication networks servicing New Orleans were damaged or disabled by the flooding, and tens of thousands of people who had not evacuated the city before landfall became stranded with little access to food, shelter or basic necessities.

The storm surge caused substantial beach erosion , in some cases completely devastating coastal areas.

Katrina also produced massive tree loss along the Gulf Coast, particularly in Louisiana’s Pearl River Basin and among bottomland hardwood forests.

The storm caused oil spills from 44 facilities throughout southeastern Louisiana. This resulted in over 7 million US gallons (26,000 m 3 ) of oil being leaked. Some spills were only a few hundred gallons, and most were contained on-site, though some oil entered the ecosystem and residential areas.

Some New Orleans residents are no longer able to get home insurance to cover them from the impact of hurricanes.

What was the response to Hurricane Katrina?

The US Government was heavily criticised for its handling of the disaster. Despite many people being evacuated, it was a very slow process. The poorest and most vulnerable were left behind.

The government provided $50 billion in aid.

During the early stages of the recovery process, the UK government sent food aid.

The National Guard was mobilised to restore law and order in New Orleans.

Premium Resources

Please support internet geography.

If you've found the resources on this page useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

Hurricane Florence

Topic home, hurricane michael, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Hurricane Katrina

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 28, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Early in the morning on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. When the storm made landfall, it had a Category 3 rating on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale–it brought sustained winds of 100–140 miles per hour–and stretched some 400 miles across.

While the storm itself did a great deal of damage, its aftermath was catastrophic. Levee breaches led to massive flooding, and many people charged that the federal government was slow to meet the needs of the people affected by the storm. Hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were displaced from their homes, and experts estimate that Katrina caused more than $100 billion in damage.

Hurricane Katrina: Before the Storm

The tropical depression that became Hurricane Katrina formed over the Bahamas on August 23, 2005, and meteorologists were soon able to warn people in the Gulf Coast states that a major storm was on its way. By August 28, evacuations were underway across the region. That day, the National Weather Service predicted that after the storm hit, “most of the [Gulf Coast] area will be uninhabitable for weeks…perhaps longer.”

Did you know? During the past century, hurricanes have flooded New Orleans six times: in 1915, 1940, 1947, 1965, 1969 and 2005.

New Orleans was at particular risk. Though about half the city actually lies above sea level, its average elevation is about six feet below sea level–and it is completely surrounded by water. Over the course of the 20th century, the Army Corps of Engineers had built a system of levees and seawalls to keep the city from flooding. The levees along the Mississippi River were strong and sturdy, but the ones built to hold back Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Borgne and the waterlogged swamps and marshes to the city’s east and west were much less reliable.

Levee Failures

Before the storm, officials worried that surge could overtop some levees and cause short-term flooding, but no one predicted levees might collapse below their designed height. Neighborhoods that sat below sea level, many of which housed the city’s poorest and most vulnerable people, were at great risk of flooding.

The day before Katrina hit, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin issued the city’s first-ever mandatory evacuation order. He also declared that the Superdome, a stadium located on relatively high ground near downtown, would serve as a “shelter of last resort” for people who could not leave the city. (For example, some 112,000 of New Orleans’ nearly 500,000 people did not have access to a car.) By nightfall, almost 80 percent of the city’s population had evacuated. Some 10,000 had sought shelter in the Superdome, while tens of thousands of others chose to wait out the storm at home.

By the time Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans early in the morning on Monday, August 29, it had already been raining heavily for hours. When the storm surge (as high as 9 meters in some places) arrived, it overwhelmed many of the city’s unstable levees and drainage canals. Water seeped through the soil underneath some levees and swept others away altogether.

By 9 a.m., low-lying places like St. Bernard Parish and the Ninth Ward were under so much water that people had to scramble to attics and rooftops for safety. Eventually, nearly 80 percent of the city was under some quantity of water.

Hurricane Katrina: The Aftermath

Many people acted heroically in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The Coast Guard rescued some 34,000 people in New Orleans alone, and many ordinary citizens commandeered boats, offered food and shelter, and did whatever else they could to help their neighbors. Yet the government–particularly the federal government–seemed unprepared for the disaster. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) took days to establish operations in New Orleans, and even then did not seem to have a sound plan of action.

Officials, even including President George W. Bush , seemed unaware of just how bad things were in New Orleans and elsewhere: how many people were stranded or missing; how many homes and businesses had been damaged; how much food, water and aid was needed. Katrina had left in her wake what one reporter called a “total disaster zone” where people were “getting absolutely desperate.”

Failures in Government Response

For one thing, many had nowhere to go. At the Superdome in New Orleans, where supplies had been limited to begin with, officials accepted 15,000 more refugees from the storm on Monday before locking the doors. City leaders had no real plan for anyone else. Tens of thousands of people desperate for food, water and shelter broke into the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center complex, but they found nothing there but chaos.

Meanwhile, it was nearly impossible to leave New Orleans: Poor people especially, without cars or anyplace else to go, were stuck. For instance, some people tried to walk over the Crescent City Connection bridge to the nearby suburb of Gretna, but police officers with shotguns forced them to turn back.

Katrina pummeled huge parts of Louisiana , Mississippi and Alabama , but the desperation was most concentrated in New Orleans. Before the storm, the city’s population was mostly black (about 67 percent); moreover, nearly 30 percent of its people lived in poverty. Katrina exacerbated these conditions and left many of New Orleans’s poorest citizens even more vulnerable than they had been before the storm.

In all, Hurricane Katrina killed nearly 2,000 people and affected some 90,000 square miles of the United States. Hundreds of thousands of evacuees scattered far and wide. According to The Data Center , an independent research organization in New Orleans, the storm ultimately displaced more than 1 million people in the Gulf Coast region.

How Levee Failures Made Hurricane Katrina a Bigger Disaster

Breaches in the system of levees and floodwalls left 80 percent of the city underwater.

Hurricane Katrina: 10 Facts About the Deadly Storm and Its Legacy

The 2005 hurricane and subsequent levee failures led to death and destruction—and dealt a lasting blow to leadership and the Gulf region.

I Was There: Hurricane Katrina: Divine Intervention

When Angela Trahan and her family were trapped in their own kitchen by floodwaters from Hurricane Katrina, Brother Ronald Hingle, a member of their school community, braved the winds and rising waters to bring them to safety.

Political Fallout From Hurricane Katrina

In the wake of the storm's devastating effects, local, state and federal governments were criticized for their slow, inadequate response, as well as for the levee failures around New Orleans. And officials from different branches of government were quick to direct the blame at each other.

"We wanted soldiers, helicopters, food and water," Denise Bottcher, press secretary for then-Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco of Louisiana told the New York Times . "They wanted to negotiate an organizational chart."

New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin argued that there was no clear designation of who was in charge, telling reporters, “The state and federal government are doing a two-step dance."

President George W. Bush had originally praised his director of FEMA, Michael D. Brown, but as criticism mounted, Brown was forced to resign, as was the New Orleans Police Department Superintendent. Louisiana Governor Blanco declined to seek re-election in 2007 and Mayor Nagin left office in 2010. In 2014 Nagin was convicted of bribery, fraud and money laundering while in office.

The U.S. Congress launched an investigation into government response to the storm and issued a highly critical report in February 2006 entitled, " A Failure of Initiative ."

Changes Since Katrina

The failures in response during Katrina spurred a series of reforms initiated by Congress. Chief among them was a requirement that all levels of government train to execute coordinated plans of disaster response. In the decade following Katrina, FEMA paid out billions in grants to ensure better preparedness.

Meanwhile, the Army Corps of Engineers built a $14 billion network of levees and floodwalls around New Orleans. The agency said the work ensured the city's safety from flooding for the time. But an April 2019 report from the Army Corps stated that, in the face of rising sea levels and the loss of protective barrier islands, the system will need updating and improvements by as early as 2023.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Hurricane Katrina summary

Hurricane Katrina , Tropical cyclone that struck the U.S. in 2005. The storm that became Hurricane Katrina was one of the most powerful Atlantic storms on record, with winds in excess of 170 mi (275 km) per hour. On August 29 the hurricane struck Louisiana and, later, Mississippi . It caused massive destruction, especially in New Orleans , where the levee system failed. By August 30, about 80 percent of the city was underwater. A public-health emergency ensued, and civil disorder was widespread until an effective military presence was established on September 2. Ultimately, the storm and its aftermath caused more than $160 billion in damage and claimed more than 1,800 lives. It was the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

- Afghanistan

- Budget Management

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Current News

- Press Briefings

- Proclamations

- Executive Orders

- Setting the Record Straight

- Ask the White House

- White House Interactive

- President's Cabinet

- USA Freedom Corps

- Faith-Based & Community Initiatives

- Office of Management and Budget

- National Security Council

- Nominations

Chapter Five: Lessons Learned

This government will learn the lessons of Hurricane Katrina. We are going to review every action and make necessary changes so that we are better prepared for any challenge of nature, or act of evil men, that could threaten our people.

-- President George W. Bush, September 15, 2005 1

The preceding chapters described the dynamics of the response to Hurricane Katrina. While there were numerous stories of great professionalism, courage, and compassion by Americans from all walks of life, our task here is to identify the critical challenges that undermined and prevented a more efficient and effective Federal response. In short, what were the key failures during the Federal response to Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina Critical Challenges

- National Preparedness

- Integrated Use of Military Capabilities

- Communications

- Logistics and Evacuations

- Search and Rescue

- Public Safety and Security

- Public Health and Medical Support

- Human Services

- Mass Care and Housing

- Public Communications

- Critical Infrastructure and Impact Assessment

- Environmental Hazards and Debris Removal

- Foreign Assistance

- Non-Governmental Aid

- Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned

- Homeland Security Professional Development and Education

- Citizen and Community Preparedness

We ask this question not to affix blame. Rather, we endeavor to find the answers in order to identify systemic gaps and improve our preparedness for the next disaster – natural or man-made. We must move promptly to understand precisely what went wrong and determine how we are going to fix it.

After reviewing and analyzing the response to Hurricane Katrina, we identified seventeen specific lessons the Federal government has learned. These lessons, which flow from the critical challenges we encountered, are depicted in the accompanying text box. Fourteen of these critical challenges were highlighted in the preceding Week of Crisis section and range from high-level policy and planning issues (e.g., the Integrated Use of Military Capabilities) to operational matters (e.g., Search and Rescue). 2 Three other challenges – Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned; Homeland Security Professional Development and Education; and Citizen and Community Preparedness – are interconnected to the others but reflect measures and institutions that improve our preparedness more broadly. These three will be discussed in the Report’s last chapter, Transforming National Preparedness.

Some of these seventeen critical challenges affected all aspects of the Federal response. Others had an impact on a specific, discrete operational capability. Yet each, particularly when taken in aggregate, directly affected the overall efficiency and effectiveness of our efforts. This chapter summarizes the challenges that ultimately led to the lessons we have learned. Over one hundred recommendations for corrective action flow from these lessons and are outlined in detail in Appendix A of the Report.

Critical Challenge: National Preparedness

Our current system for homeland security does not provide the necessary framework to manage the challenges posed by 21st Century catastrophic threats. But to be clear, it is unrealistic to think that even the strongest framework can perfectly anticipate and overcome all challenges in a crisis. While we have built a response system that ably handles the demands of a typical hurricane season, wildfires, and other limited natural and man-made disasters, the system clearly has structural flaws for addressing catastrophic events. During the Federal response to Katrina 3 , four critical flaws in our national preparedness became evident: Our processes for unified management of the national response; command and control structures within the Federal government; knowledge of our preparedness plans; and regional planning and coordination. A discussion of each follows below.

Unified Management of the National Response

Effective incident management of catastrophic events requires coordination of a wide range of organizations and activities, public and private. Under the current response framework, the Federal government merely “coordinates” resources to meet the needs of local and State governments based upon their requests for assistance. Pursuant to the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Plan (NRP), Federal and State agencies build their command and coordination structures to support the local command and coordination structures during an emergency. Yet this framework does not address the conditions of a catastrophic event with large scale competing needs, insufficient resources, and the absence of functioning local governments. These limitations proved to be major inhibitors to the effective marshalling of Federal, State, and local resources to respond to Katrina.

Soon after Katrina made landfall, State and local authorities understood the devastation was serious but, due to the destruction of infrastructure and response capabilities, lacked the ability to communicate with each other and coordinate a response. Federal officials struggled to perform responsibilities generally conducted by State and local authorities, such as the rescue of citizens stranded by the rising floodwaters, provision of law enforcement, and evacuation of the remaining population of New Orleans, all without the benefit of prior planning or a functioning State/local incident command structure to guide their efforts.

The Federal government cannot and should not be the Nation’s first responder. State and local governments are best positioned to address incidents in their jurisdictions and will always play a large role in disaster response. But Americans have the right to expect that the Federal government will effectively respond to a catastrophic incident. When local and State governments are overwhelmed or incapacitated by an event that has reached catastrophic proportions, only the Federal government has the resources and capabilities to respond. The Federal government must therefore plan, train, and equip to meet the requirements for responding to a catastrophic event.

Command and Control Within the Federal Government

In terms of the management of the Federal response, our architecture of command and control mechanisms as well as our existing structure of plans did not serve us well. Command centers in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and elsewhere in the Federal government had unclear, and often overlapping, roles and responsibilities that were exposed as flawed during this disaster. The Secretary of Homeland Security, is the President’s principal Federal official for domestic incident management, but he had difficulty coordinating the disparate activities of Federal departments and agencies. The Secretary lacked real-time, accurate situational awareness of both the facts from the disaster area as well as the on-going response activities of the Federal, State, and local players.

The National Response Plan’s Mission Assignment process proved to be far too bureaucratic to support the response to a catastrophe. Melvin Holden, Mayor-President of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, noted that, “requirements for paper work and form completions hindered immediate action and deployment of people and materials to assist in rescue and recovery efforts.” 4 Far too often, the process required numerous time consuming approval signatures and data processing steps prior to any action, delaying the response. As a result, many agencies took action under their own independent authorities while also responding to mission assignments from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), creating further process confusion and potential duplication of efforts.

This lack of coordination at the Federal headquarters-level reflected confusing organizational structures in the field. As noted in the Week of Crisis chapter, because the Principal Federal Official (PFO) has coordination authority but lacks statutory authority over the Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO), inefficiencies resulted when the second PFO was appointed. The first PFO appointed for Katrina did not have this problem because, as the Director of FEMA, he was able to directly oversee the FCOs because they fell under his supervisory authority. 5 Future plans should ensure that the PFO has the authority required to execute these responsibilities.

Moreover, DHS did not establish its NRP-specified disaster site multi-agency coordination center—the Joint Field Office (JFO)—until after the height of the crisis. 6 Further, without subordinate JFO structures to coordinate Federal response actions near the major incident sites, Federal response efforts in New Orleans were not initially well-coordinated. 7

Lastly, the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) did not function as envisioned in the NRP. First, since the ESFs do not easily integrate into the NIMS Incident Command System (ICS) structure, competing systems were implemented in the field – one based on the ESF structure and a second based on the ICS. Compounding the coordination problem, the agencies assigned ESF responsibilities did not respect the role of the PFO. As VADM Thad Allen stated, “The ESF structure currently prevents us from coordinating effectively because if agencies responsible for their respective ESFs do not like the instructions they are receiving from the PFO at the field level, they go to their headquarters in Washington to get decisions reversed. This is convoluted, inefficient, and inappropriate during emergency conditions. Time equals lives saved.”

Knowledge and Practice in the Plans

At the most fundamental level, part of the explanation for why the response to Katrina did not go as planned is that key decision-makers at all levels simply were not familiar with the plans. The NRP was relatively new to many at the Federal, State, and local levels before the events of Hurricane Katrina. 8 This lack of understanding of the “National” plan not surprisingly resulted in ineffective coordination of the Federal, State, and local response. Additionally, the NRP itself provides only the ‘base plan’ outlining the overall elements of a response: Federal departments and agencies were required to develop supporting operational plans and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to integrate their activities into the national response. 9 In almost all cases, the integrating SOPs were either non-existent or still under development when Hurricane Katrina hit. Consequently, some of the specific procedures and processes of the NRP were not properly implemented, and Federal partners had to operate without any prescribed guidelines or chains of command.

Furthermore, the JFO staff and other deployed Federal personnel often lacked a working knowledge of NIMS or even a basic understanding of ICS principles. As a result, valuable time and resources were diverted to provide on-the-job ICS training to Federal personnel assigned to the JFO. This inability to place trained personnel in the JFO had a detrimental effect on operations, as there were not enough qualified persons to staff all of the required positions. We must require all incident management personnel to have a working knowledge of NIMS and ICS principles.

Insufficient Regional Planning and Coordination

The final structural flaw in our current system for national preparedness is the weakness of our regional planning and coordination structures. Guidance to governments at all levels is essential to ensure adequate preparedness for major disasters across the Nation. To this end, the Interim National Preparedness Goal (NPG) and Target Capabilities List (TCL) can assist Federal, State, and local governments to: identify and define required capabilities and what levels of those capabilities are needed; establish priorities within a resource-constrained environment; clarify and understand roles and responsibilities in the national network of homeland security capabilities; and develop mutual aid agreements.

Since incorporating FEMA in March 2003, DHS has spread FEMA’s planning and coordination capabilities and responsibilities among DHS’s other offices and bureaus. DHS also did not maintain the personnel and resources of FEMA’s regional offices. 10 FEMA’s ten regional offices are responsible for assisting multiple States and planning for disasters, developing mitigation programs, and meeting their needs when major disasters occur. During Katrina, eight out of the ten FEMA Regional Directors were serving in an acting capacity and four of the six FEMA headquarters operational division directors were serving in an acting capacity. While qualified acting directors filled in, it placed extra burdens on a staff that was already stretched to meet the needs left by the vacancies.

Additionally, many FEMA programs that were operated out of the FEMA regions, such as the State and local liaison program and all grant programs, have moved to DHS headquarters in Washington. When programs operate out of regional offices, closer relationships are developed among all levels of government, providing for stronger relationships at all levels. By the same token, regional personnel must remember that they represent the interests of the Federal government and must be cautioned against losing objectivity or becoming mere advocates of State and local interests. However, these relationships are critical when a crisis situation develops, because individuals who have worked and trained together daily will work together more effectively during a crisis.

Lessons Learned:

The Federal government should work with its homeland security partners in revising existing plans, ensuring a functional operational structure - including within regions - and establishing a clear, accountable process for all National preparedness efforts. In doing so, the Federal government must:

- Ensure that Executive Branch agencies are organized, trained, and equipped to perform their response roles.

- Finalize and implement the National Preparedness Goal.

Critical Challenge: Integrated Use of Military Capabilities

The Federal response to Hurricane Katrina demonstrates that the Department of Defense (DOD) has the capability to play a critical role in the Nation’s response to catastrophic events. During the Katrina response, DOD – both National Guard and active duty forces – demonstrated that along with the Coast Guard it was one of the only Federal departments that possessed real operational capabilities to translate Presidential decisions into prompt, effective action on the ground. In addition to possessing operational personnel in large numbers that have been trained and equipped for their missions, DOD brought robust communications infrastructure, logistics, and planning capabilities. Since DOD, first and foremost, has its critical overseas mission, the solution to improving the Federal response to future catastrophes cannot simply be “let the Department of Defense do it.” Yet DOD capabilities must be better identified and integrated into the Nation’s response plans.

The Federal response to Hurricane Katrina highlighted various challenges in the use of military capabilities during domestic incidents. For instance, limitations under Federal law and DOD policy caused the active duty military to be dependent on requests for assistance. These limitations resulted in a slowed application of DOD resources during the initial response. Further, active duty military and National Guard operations were not coordinated and served two different bosses, one the President and the other the Governor.

Limitations to Department of Defense Response Authority

For Federal domestic disaster relief operations, DOD currently uses a “pull” system that provides support to civil authorities based upon specific requests from local, State, or Federal authorities. 11 This process can be slow and bureaucratic. Assigning active duty military forces or capabilities to support disaster relief efforts usually requires a request from FEMA 12 , an assessment by DOD on whether the request can be supported, approval by the Secretary of Defense or his designated representative, and a mission assignment for the military forces or capabilities to provide the requested support. From the time a request is initiated until the military force or capability is delivered to the disaster site requires a 21-step process. 13 While this overly bureaucratic approach has been adequate for most disasters, in a catastrophic event like Hurricane Katrina the delays inherent in this “pull” system of responding to requests resulted in critical needs not being met. 14 One could imagine a situation in which a catastrophic event is of such a magnitude that it would require an even greater role for the Department of Defense. For these reasons, we should both expedite the mission assignment request and the approval process, but also define the circumstances under which we will push resources to State and local governments absent a request.

Unity of Effort among Active Duty Forces and the National Guard

In the overall response to Hurricane Katrina, separate command structures for active duty military and the National Guard hindered their unity of effort. U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) commanded active duty forces, while each State government commanded its National Guard forces. For the first two days of Katrina response operations, USNORTHCOM did not have situational awareness of what forces the National Guard had on the ground. Joint Task Force Katrina (JTF-Katrina) simply could not operate at full efficiency when it lacked visibility of over half the military forces in the disaster area. 15 Neither the Louisiana National Guard nor JTF-Katrina had a good sense for where each other’s forces were located or what they were doing. For example, the JTF-Katrina Engineering Directorate had not been able to coordinate with National Guard forces in the New Orleans area. As a result, some units were not immediately assigned missions matched to on-the-ground requirements. Further, FEMA requested assistance from DOD without knowing what State National Guard forces had already deployed to fill the same needs. 16

Also, the Commanding General of JTF-Katrina and the Adjutant Generals (TAGs) of Louisiana and Mississippi had only a coordinating relationship, with no formal command relationship established. This resulted in confusion over roles and responsibilities between National Guard and Federal forces and highlights the need for a more unified command structure. 17

Structure and Resources of the National Guard

As demonstrated during the Hurricane Katrina response, the National Guard Bureau (NGB) is a significant joint force provider for homeland security missions. Throughout the response, the NGB provided continuous and integrated reporting of all National Guard assets deployed in both a Federal and non-Federal status to USNORTHCOM, Joint Forces Command, Pacific Command, and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense. This is an important step toward achieving unity of effort. However, NGB’s role in homeland security is not yet clearly defined. The Chief of the NGB has made a recommendation to the Secretary of Defense that NGB be chartered as a joint activity of the DOD. 18 Achieving these efforts will serve as the foundation for National Guard transformation and provide a total joint force capability for homeland security missions. 19

The Departments of Homeland Security and Defense should jointly plan for the Department of Defense’s support of Federal response activities as well as those extraordinary circumstances when it is appropriate for the Department of Defense to lead the Federal response. In addition, the Department of Defense should ensure the transformation of the National Guard is focused on increased integration with active duty forces for homeland security plans and activities.

Critical Challenge: Communications

Hurricane Katrina destroyed an unprecedented portion of the core communications infrastructure throughout the Gulf Coast region. As described earlier in the Report, the storm debilitated 911 emergency call centers, disrupting local emergency services. 20 Nearly three million customers lost telephone service. Broadcast communications, including 50 percent of area radio stations and 44 percent of area television stations, similarly were affected. 21 More than 50,000 utility poles were toppled in Mississippi alone, meaning that even if telephone call centers and electricity generation capabilities were functioning, the connections to the customers were broken. 22 Accordingly, the communications challenges across the Gulf Coast region in Hurricane Katrina’s wake were more a problem of basic operability 23 , than one of equipment or system interoperability . 24 The complete devastation of the communications infrastructure left emergency responders and citizens without a reliable network across which they could coordinate. 25

Although Federal, State, and local agencies had communications plans and assets in place, these plans and assets were neither sufficient nor adequately integrated to respond effectively to the disaster. 26 Many available communications assets were not utilized fully because there was no national, State-wide, or regional communications plan to incorporate them. For example, despite their contributions to the response effort, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service’s radio cache—the largest civilian cache of radios in the United States—had additional radios available that were not utilized. 27

Federal, State, and local governments have not yet completed a comprehensive strategy to improve operability and interoperability to meet the needs of emergency responders. 28 This inability to connect multiple communications plans and architectures clearly impeded coordination and communication at the Federal, State, and local levels. A comprehensive, national emergency communications strategy is needed to confront the challenges of incorporating existing equipment and practices into a constantly changing technological and cultural environment. 29

The Department of Homeland Security should review our current laws, policies, plans, and strategies relevant to communications. Upon the conclusion of this review, the Homeland Security Council, with support from the Office of Science and Technology Policy, should develop a National Emergency Communications Strategy that supports communications operability and interoperability.

Critical Challenge: Logistics and Evacuation

The scope of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation, the effects on critical infrastructure in the region, and the debilitation of State and local response capabilities combined to produce a massive requirement for Federal resources. The existing planning and operational structure for delivering critical resources and humanitarian aid clearly proved to be inadequate to the task. The highly bureaucratic supply processes of the Federal government were not sufficiently flexible and efficient, and failed to leverage the private sector and 21st Century advances in supply chain management.

Throughout the response, Federal resource managers had great difficulty determining what resources were needed, what resources were available, and where those resources were at any given point in time. Even when Federal resource managers had a clear understanding of what was needed, they often could not readily determine whether the Federal government had that asset, or what alternative sources might be able to provide it. As discussed in the Week of Crisis chapter, even when an agency came directly to FEMA with a list of available resources that would be useful during the response, there was no effective mechanism for efficiently integrating and deploying these resources. Nor was there an easy way to find out whether an alternative source, such as the private sector or a charity, might be able to better fill the need. Finally, FEMA’s lack of a real-time asset-tracking system – a necessity for successful 21st Century businesses – left Federal managers in the dark regarding the status of resources once they were shipped. 30

Our logistics system for the 21st Century should be a fully transparent, four-tiered system. First, we must encourage and ultimately require State and local governments to pre-contract for resources and commodities that will be critical for responding to all hazards. Second, if these arrangements fail, affected State governments should ask for additional resources from other States through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) process. Third, if such interstate mutual aid proves insufficient, the Federal government, having the benefit of full transparency, must be able to assist State and local governments to move commodities regionally. But in the end, FEMA must be able to supplement and, in catastrophic incidents, supplant State and local systems with a fully modern approach to commodity management.

The Department of Homeland Security, in coordination with State and local governments and the private sector, should develop a modern, flexible, and transparent logistics system. This system should be based on established contracts for stockpiling commodities at the local level for emergencies and the provision of goods and services during emergencies. The Federal government must develop the capacity to conduct large-scale logistical operations that supplement and, if necessary, replace State and local logistical systems by leveraging resources within both the public sector and the private sector.

With respect to evacuation—fundamentally a State and local responsibility—the Hurricane Katrina experience demonstrates that the Federal government must be prepared to fulfill the mission if State and local efforts fail. Unfortunately, a lack of prior planning combined with poor operational coordination generated a weak Federal performance in supporting the evacuation of those most vulnerable in New Orleans and throughout the Gulf Coast following Katrina’s landfall. The Federal effort lacked critical elements of prior planning, such as evacuation routes, communications, transportation assets, evacuee processing, and coordination with State, local, and non-governmental officials receiving and sheltering the evacuees. Because of poor situational awareness and communications throughout the evacuation operation, FEMA had difficulty providing buses through ESF-1, Transportation, (with the Department of Transportation as the coordinating agency). 31 FEMA also had difficulty delivering food, water, and other critical commodities to people waiting to be evacuated, most significantly at the Superdome. 32

The Department of Transportation, in coordination with other appropriate departments of the Executive Branch, must also be prepared to conduct mass evacuation operations when disasters overwhelm or incapacitate State and local governments.

Critical Challenge: Search and Rescue

After Hurricane Katrina made landfall, rising floodwaters stranded thousands in New Orleans on rooftops, requiring a massive civil search and rescue operation. The Coast Guard, FEMA Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Task Forces 33 , and DOD forces 34 , in concert with State and local emergency responders from across the country, courageously combined to rescue tens of thousands of people. With extraordinary ingenuity and tenacity, Federal, State, and local emergency responders plucked people from rooftops while avoiding urban hazards not normally encountered during waterborne rescue. 35

Yet many of these courageous lifesavers were put at unnecessary risk by a structure that failed to support them effectively. The overall search and rescue effort demonstrated the need for greater coordination between US&R, the Coast Guard, and military responders who, because of their very different missions, train and operate in very different ways. For example, Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) teams had a particularly challenging situation since they are neither trained nor equipped to perform water rescue. Thus they could not immediately rescue people trapped by the flood waters. 36

Furthermore, lacking an integrated search and rescue incident command, the various agencies were unable to effectively coordinate their operations. 37 This meant that multiple rescue teams were sent to the same areas, while leaving others uncovered. 38 When successful rescues were made, there was no formal direction on where to take those rescued. 39 Too often rescuers had to leave victims at drop-off points and landing zones that had insufficient logistics, medical, and communications resources, such as atop the I-10 cloverleaf near the Superdome. 40

The Department of Homeland Security should lead an interagency review of current policies and procedures to ensure effective integration of all Federal search and rescue assets during disaster response.

Critical Challenge: Public Safety and Security

State and local governments have a fundamental responsibility to provide for the public safety and security of their residents. During disasters, the Federal government provides law enforcement assistance only when those resources are overwhelmed or depleted. 41 Almost immediately following Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, law and order began to deteriorate in New Orleans. The city’s overwhelmed police force–70 percent of which were themselves victims of the disaster—did not have the capacity to arrest every person witnessed committing a crime, and many more crimes were undoubtedly neither observed by police nor reported. The resulting lawlessness in New Orleans significantly impeded—and in some cases temporarily halted—relief efforts and delayed restoration of essential private sector services such as power, water, and telecommunications. 42

The Federal law enforcement response to Hurricane Katrina was a crucial enabler to the reconstitution of the New Orleans Police Department’s command structure as well as the larger criminal justice system. Joint leadership from the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security integrated the available Federal assets into the remaining local police structure and divided the Federal law enforcement agencies into corresponding New Orleans Police Department districts.

While the deployment of Federal law enforcement capability to New Orleans in a dangerous and chaotic environment significantly contributed to the restoration of law and order, pre-event collaborative planning between Federal, State, and local officials would have improved the response. Indeed, Federal, State, and local law enforcement officials performed admirably in spite of a system that should have better supported them. Local, State, and Federal law enforcement were ill-prepared and ill-positioned to respond efficiently and effectively to the crisis.

In the end, it was clear that Federal law enforcement support to State and local officials required greater coordination, unity of command, collaborative planning and training with State and local law enforcement, as well as detailed implementation guidance. For example, the Federal law enforcement response effort did not take advantage of all law enforcement assets embedded across Federal departments and agencies. Several departments promptly offered their assistance, but their law enforcement assets were incorporated only after weeks had passed, or not at all. 43

Coordination challenges arose even after Federal law enforcement personnel arrived in New Orleans. For example, several departments and agencies reported that the procedures for becoming deputized to enforce State law were cumbersome and inefficient. In Louisiana, a State Police attorney had to physically be present to swear in Federal agents. Many Federal law enforcement agencies also had to complete a cumbersome Federal deputization process. 44 New Orleans was then confronted with a rapid influx of law enforcement officers from a multitude of States and jurisdictions—each with their own policies and procedures, uniforms, and rules on the use of force—which created the need for a command structure to coordinate their efforts. 45

Hurricane Katrina also crippled the region’s criminal justice system. Problems such as a significant loss of accountability of many persons under law enforcement supervision 46 , closure of the court systems in the disaster 47 , and hasty evacuation of prisoners 48 were largely attributable to the absence of contingency plans at all levels of government.

The Department of Justice, in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security, should examine Federal responsibilities for support to State and local law enforcement and criminal justice systems during emergencies and then build operational plans, procedures, and policies to ensure an effective Federal law enforcement response.

Critical Challenge: Public Health and Medical Support

Hurricane Katrina created enormous public health and medical challenges, especially in Louisiana and Mississippi—States with public health infrastructures that ranked 49th and 50th in the Nation, respectively. 49 But it was the subsequent flooding of New Orleans that imposed catastrophic public health conditions on the people of southern Louisiana and forced an unprecedented mobilization of Federal public health and medical assets. Tens of thousands of people required medical care. Over 200,000 people with chronic medical conditions, displaced by the storm and isolated by the flooding, found themselves without access to their usual medications and sources of medical care. Several large hospitals were totally destroyed and many others were rendered inoperable. Nearly all smaller health care facilities were shut down. Although public health and medical support efforts restored the capabilities of many of these facilities, the region’s health care infrastructure sustained extraordinary damage. 50

Most local and State public health and medical assets were overwhelmed by these conditions, placing even greater responsibility on federally deployed personnel. Immediate challenges included the identification, triage and treatment of acutely sick and injured patients; the management of chronic medical conditions in large numbers of evacuees with special health care needs; the assessment, communication and mitigation of public health risk; and the provision of assistance to State and local health officials to quickly reestablish health care delivery systems and public health infrastructures. 51

Despite the success of Federal, State, and local personnel in meeting this enormous challenge, obstacles at all levels reduced the reach and efficiency of public health and medical support efforts. In addition, the coordination of Federal assets within and across agencies was poor. The cumbersome process for the authorization of reimbursement for medical and public health services provided by Federal agencies created substantial delays and frustration among health care providers, patients and the general public. 52 In some cases, significant delays slowed the arrival of Federal assets to critical locations. 53 In other cases, large numbers of Federal assets were deployed, only to be grossly underutilized. 54 Thousands of medical volunteers were sought by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and though they were informed that they would likely not be needed unless notified otherwise, many volunteers reported that they received no message to that effect. 55 These inefficiencies were the products of a fragmented command structure for medical response; inadequate evacuation of patients; weak State and local public health infrastructures 56 ; insufficient pre-storm risk communication to the public 57 ; and the absence of a uniform electronic health record system.

In coordination with the Department of Homeland Security and other homeland security partners, the Department of Health and Human Services should strengthen the Federal government’s capability to provide public health and medical support during a crisis. This will require the improvement of command and control of public health resources, the development of deliberate plans, an additional investment in deployable operational resources, and an acceleration of the initiative to foster the widespread use of interoperable electronic health records systems.

Critical Challenge: Human Services

Disasters—especially those of catastrophic proportions—produce many victims whose needs exceed the capacity of State and local resources. These victims who depend on the Federal government for assistance fit into one of two categories: (1) those who need Federal disaster-related assistance, and (2) those who need continuation of government assistance they were receiving before the disaster, plus additional disaster-related assistance. Hurricane Katrina produced many thousands of both categories of victims. 58

The Federal government maintains a wide array of human service programs to provide assistance to special-needs populations, including disaster victims. 59 Collectively, these programs provide a safety net to particularly vulnerable populations.

The Emergency Support Function 6 (ESF-6) Annex to the NRP assigns responsibility for the emergency delivery of human services to FEMA. While FEMA is the coordinator of ESF-6, it shares primary agency responsibility with the American Red Cross. 60 The Red Cross focuses on mass care (e.g. care for people in shelters), and FEMA continues the human services components for ESF-6 as the mass care effort transitions from the response to the recovery phase. 61 The human services provided under ESF-6 include: counseling; special-needs population support; immediate and short-term assistance for individuals, households, and groups dealing with the aftermath of a disaster; and expedited processing of applications for Federal benefits. 62 The NRP calls for “reducing duplication of effort and benefits, to the extent possible,” to include “streamlining assistance as appropriate.” 63

Prior to Katrina’s landfall along the Gulf Coast and during the subsequent several weeks, Federal preparation for distributing individual assistance proved frustrating and inadequate. Because the NRP did not mandate a single Federal point of contact for all assistance and required FEMA to merely coordinate assistance delivery, disaster victims confronted an enormously bureaucratic, inefficient, and frustrating process that failed to effectively meet their needs. The Federal government’s system for distribution of human services was not sufficiently responsive to the circumstances of a large number of victims—many of whom were particularly vulnerable—who were forced to navigate a series of complex processes to obtain critical services in a time of extreme duress. As mentioned in the preceding chapter, the Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) did not provide victims single-point access to apply for the wide array of Federal assistance programs.

The Department of Health and Human Services should coordinate with other departments of the Executive Branch, as well as State governments and non-governmental organizations, to develop a robust, comprehensive, and integrated system to deliver human services during disasters so that victims are able to receive Federal and State assistance in a simple and seamless manner. In particular, this system should be designed to provide victims a consumer oriented, simple, effective, and single encounter from which they can receive assistance.

Critical Challenge: Mass Care and Housing

Hurricane Katrina resulted in the largest national housing crisis since the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The impact of this massive displacement was felt throughout the country, with Gulf residents relocating to all fifty States and the District of Columbia. 64 Prior to the storm’s landfall, an exodus of people fled its projected path, creating an urgent need for suitable shelters. Those with the willingness and ability to evacuate generally found temporary shelter or housing. However, the thousands of people in New Orleans who were either unable to move due to health reasons or lack of transportation, or who simply did not choose to comply with the mandatory evacuation order, had significant difficulty finding suitable shelter after the hurricane had devastated the city. 65

Overall, Federal, State, and local plans were inadequate for a catastrophe that had been anticipated for years. Despite the vast shortcomings of the Superdome and other shelters, State and local officials had no choice but to direct thousands of individuals to such sites immediately after the hurricane struck. Furthermore, the Federal government’s capability to provide housing solutions to the displaced Gulf Coast population has proved to be far too slow, bureaucratic, and inefficient.

The Federal shortfall resulted from a lack of interagency coordination to relocate and house people. FEMA’s actions often were inconsistent with evacuees’ needs and preferences. Despite offers from the Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA), Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Agriculture (USDA) as well as the private sector to provide thousands of housing units nationwide, FEMA focused its housing efforts on cruise ships and trailers, which were expensive and perceived by some to be a means to force evacuees to return to New Orleans. 66 HUD, with extensive expertise and perspective on large-scale housing challenges and its nation-wide relationships with State public housing authorities, was not substantially engaged by FEMA in the housing process until late in the effort. 67 FEMA’s temporary and long-term housing efforts also suffered from the failure to pre-identify workable sites and available land and the inability to take advantage of housing units available with other Federal agencies.

Using established Federal core competencies and all available resources, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, in coordination with other departments of the Executive Branch with housing stock, should develop integrated plans and bolstered capabilities for the temporary and long-term housing of evacuees. The American Red Cross and the Department of Homeland Security should retain responsibility and improve the process of mass care and sheltering during disasters.

Critical Challenge: Public Communications

The Federal government’s dissemination of essential public information prior to Hurricane Katrina’s Gulf landfall is one of the positive lessons learned. The many professionals at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Hurricane Center worked with diligence and determination in disseminating weather reports and hurricane track predictions as described in the Pre-landfall chapter. This includes disseminating warnings and forecasts via NOAA Radio and the internet, which operates in conjunction with the Emergency Alert System (EAS). 68 We can be certain that their efforts saved lives.

However, more could have been done by officials at all levels of government. For example, the EAS—a mechanism for Federal, State and local officials to communicate disaster information and instructions—was not utilized by State and local officials in Louisiana, Mississippi or Alabama prior to Katrina’s landfall. 69

Further, without timely, accurate information or the ability to communicate, public affairs officers at all levels could not provide updates to the media and to the public. It took several weeks before public affairs structures, such as the Joint Information Centers, were adequately resourced and operating at full capacity. In the meantime, Federal, State, and local officials gave contradictory messages to the public, creating confusion and feeding the perception that government sources lacked credibility. On September 1, conflicting views of New Orleans emerged with positive statements by some Federal officials that contradicted a more desperate picture painted by reporters in the streets. 70 The media, operating 24/7, gathered and aired uncorroborated information which interfered with ongoing emergency response efforts. 71 The Federal public communications and public affairs response proved inadequate and ineffective.

The Department of Homeland Security should develop an integrated public communications plan to better inform, guide, and reassure the American public before, during, and after a catastrophe. The Department of Homeland Security should enable this plan with operational capabilities to deploy coordinated public affairs teams during a crisis.

Critical Challenge: Critical Infrastructure and Impact Assessment

Hurricane Katrina had a significant impact on many sectors of the region’s “critical infrastructure,” especially the energy sector. 72 The Hurricane temporarily caused the shutdown of most crude oil and natural gas production in the Gulf of Mexico as well as much of the refining capacity in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. “[M]ore than ten percent of the Nation’s imported crude oil enters through the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port” 73 adding to the impact on the energy sector. Additionally, eleven petroleum refineries, or one-sixth of the Nation’s refining capacity, were shut down. 74 Across the region more than 2.5 million customers suffered power outages across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. 75

While there were successes, the Federal government’s ability to protect and restore the operation of priority national critical infrastructure was hindered by four interconnected problems. First, the NRP-guided response did not account for the need to coordinate critical infrastructure protection and restoration efforts across the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs). The NRP designates the protection and restoration of critical infrastructure as essential objectives of five ESFs: Transportation; Communications; Public Works and Engineering; Agriculture; and Energy. 76 Although these critical infrastructures are necessary to assist in all other response and restoration efforts, there are seventeen critical infrastructure and key resource sectors whose needs must be coordinated across virtually every ESF during response and recovery. 77 Second, the Federal government did not adequately coordinate its actions with State and local protection and restoration efforts. In fact, the Federal government created confusion by responding to individualized requests in an inconsistent manner. 78 Third, Federal, State, and local officials responded to Hurricane Katrina without a comprehensive understanding of the interdependencies of the critical infrastructure sectors in each geographic area and the potential national impact of their decisions. For example, an energy company arranged to have generators shipped to facilities where they were needed to restore the flow of oil to the entire mid-Atlantic United States. However, FEMA regional representatives diverted these generators to hospitals. While lifesaving efforts are always the first priority, there was no overall awareness of the competing important needs of the two requests. Fourth, the Federal government lacked the timely, accurate, and relevant ground-truth information necessary to evaluate which critical infrastructures were damaged, inoperative, or both. The FEMA teams that were deployed to assess damage to the regions did not focus on critical infrastructure and did not have the expertise necessary to evaluate protection and restoration needs. 79

The Interim National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) provides strategic-level guidance for all Federal, State, and local entities to use in prioritizing infrastructure for protection. 80 However, there is no supporting implementation plan to execute these actions during a natural disaster. Federal, State, and local officials need an implementation plan for critical infrastructure protection and restoration that can be shared across the Federal government, State and local governments, and with the private sector, to provide them with the necessary background to make informed preparedness decisions with limited resources.

The Department of Homeland Security, working collaboratively with the private sector, should revise the National Response Plan and finalize the Interim National Infrastructure Protection Plan to be able to rapidly assess the impact of a disaster on critical infrastructure. We must use this knowledge to inform Federal response and prioritization decisions and to support infrastructure restoration in order to save lives and mitigate the impact of the disaster on the Nation.

Critical Challenge: Environmental Hazards and Debris Removal

The Federal clean-up effort for Hurricane Katrina was an immense undertaking. The storm impact caused the spill of over seven million gallons of oil into Gulf Coast waterways. Additionally, it flooded three Superfund 81 sites in the New Orleans area, and destroyed or compromised numerous drinking water facilities and wastewater treatment plants along the Gulf Coast. 82 The storm’s collective environmental damage, while not creating the “toxic soup” portrayed in the media, nonetheless did create a potentially hazardous environment for emergency responders and the general public. 83 In response, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Coast Guard jointly led an interagency environmental assessment and recovery effort, cleaning up the seven million gallons of oil and resolving over 2,300 reported cases of pollution. 84

While this response effort was commendable, Federal officials could have improved the identification of environmental hazards and communication of appropriate warnings to emergency responders and the public. For example, the relatively small number of personnel available during the critical week after landfall were unable to conduct a rapid and comprehensive environmental assessment of the approximately 80 square miles flooded in New Orleans, let alone the nearly 93,000 square miles affected by the hurricane. 85

Competing priorities hampered efforts to assess the environment. Moreover, although the process used to identify environmental hazards provides accurate results, these results are not prompt enough to provide meaningful information to responders. Furthermore, there must be a comprehensive plan to accurately and quickly communicate this critical information to the emergency responders and area residents who need it. 86 Had such a plan existed, the mixed messages from Federal, State, and local officials on the reentry into New Orleans could have been avoided.

Debris Removal

State and local governments are normally responsible for debris removal. However, in the event of a disaster in which State and local governments are overwhelmed and request assistance, the Federal government can provide two forms of assistance: debris removal by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) or other Federal agencies, or reimbursement for locally contracted debris removal. 87

Hurricane Katrina created an estimated 118 million cubic yards of debris. In just five months, 71 million cubic yards of debris have been removed from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. In comparison, it took six months to remove the estimated 20 million cubic yards of debris created by Hurricane Andrew. 88

However, the unnecessarily complicated rules for removing debris from private property hampered the response. 89 In addition, greater collaboration among Federal, State, and local officials as well as an enhanced public communication program could have improved the effectiveness of the Federal response.

The Department of Homeland Security, in coordination with the Environmental Protection Agency, should oversee efforts to improve the Federal government’s capability to quickly gather environmental data and to provide the public and emergency responders the most accurate information available, to determine whether it is safe to operate in a disaster environment or to return after evacuation. In addition, the Department of Homeland Security should work with its State and local homeland security partners to plan and to coordinate an integrated approach to debris removal during and after a disaster.

Critical Challenge: Managing Offers of Foreign Assistance and Inquiries Regarding Affected Foreign Nationals

Our experience with the tragedies of September 11th and Hurricane Katrina underscored that our domestic crises have international implications. Soon after the extent of Hurricane Katrina’s damage became known, the United States became the beneficiary of an incredible international outpouring of assistance. One hundred fifty-one (151) nations and international organizations offered financial or material assistance to support relief efforts. 90 Also, we found that among the victims were foreign nationals who were in the country on business, vacation, or as residents. Not surprisingly, foreign governments sought information regarding the safety of their citizens.

We were not prepared to make the best use of foreign support. Some foreign governments sought to contribute aid that the United States could not accept or did not require. In other cases, needed resources were tied up by bureaucratic red tape. 91 But more broadly, we lacked the capability to prioritize and integrate such a large quantity of foreign assistance into the ongoing response. Absent an implementation plan for the prioritization and integration of foreign material assistance, valuable resources went unused, and many donor countries became frustrated. 92 While we ultimately overcame these obstacles amidst the crisis, our experience underscores the need for pre-crisis planning.

Nor did we have the mechanisms in place to provide foreign governments with whatever knowledge we had regarding the status of their nationals. Despite the fact that many victims of the September 11, 2001, tragedy were foreign nationals, the NRP does not take into account foreign populations (e.g. long-term residents, students, businessmen, tourists, and foreign government officials) affected by a domestic catastrophe. In addition, Federal, State, and local emergency response officials have not included assistance to foreign nationals in their response planning.

Many foreign governments, as well as the family and friends of foreign nationals, looked to the Department of State for information regarding the safety and location of their citizens after Hurricane Katrina. The absence of a central system to manage and promptly respond to inquires about affected foreign nationals led to confusion. 93

The Department of State, in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security, should review and revise policies, plans, and procedures for the management of foreign disaster assistance. In addition, this review should clarify responsibilities and procedures for handling inquiries regarding affected foreign nationals.

Critical Challenge: Non-governmental Aid

Over the course of the Hurricane Katrina response, a significant capability for response resided in organizations outside of the government. Non-governmental and faith-based organizations, as well as the private sector all made substantial contributions. Unfortunately, the Nation did not always make effective use of these contributions because we had not effectively planned for integrating them into the overall response effort.

Even in the best of circumstances, government alone cannot deliver all disaster relief. Often, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are the quickest means of providing local relief, but perhaps most importantly, they provide a compassionate, human face to relief efforts. We must recognize that NGOs play a fundamental role in response and recovery efforts and will contribute in ways that are, in many cases, more efficient and effective than the Federal government’s response. We must plan for their participation and treat them as valued and necessary partners.

The number of volunteer, non-profit, faith-based, and private sector entities that aided in the Hurricane Katrina relief effort was truly extraordinary. Nearly every national, regional, and local charitable organization in the United States, and many from abroad, contributed aid to the victims of the storm. Trained volunteers from member organizations of the National Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster (NVOAD), the American Red Cross, Medical Reserve Corps (MRC), Community Emergency Response Team (CERT), as well as untrained volunteers from across the United States, deployed to Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

Government sponsored volunteer organizations also played a critical role in providing relief and assistance. For example, the USA Freedom Corps persuaded numerous non-profit organizations and the Governor’s State Service Commissions to list their hurricane relief volunteer opportunities in the USA Freedom Corps volunteer search engine. The USA Freedom Corps also worked with the Corporation for National and Community Service, which helped to create a new, people-driven “Katrina Resource Center” to help volunteers connect their resources with needs on the ground. 94 In addition, 14,000 Citizen Corps volunteers supported response and recovery efforts around the country. 95 This achievement demonstrates that seamless coordination among government agencies and volunteer organizations is possible when they build cooperative relationships and conduct joint planning and exercises before an incident occurs. 96

Faith-based organizations also provided extraordinary services. For example, more than 9,000 Southern Baptist Convention of the North American Mission Board volunteers from forty-one states served in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. These volunteers ran mobile kitchens and recovery sites. 97 Many smaller, faith-based organizations, such as the Set Free Indeed Ministry in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, brought comfort and offered shelter to the survivors. They used their facilities and volunteers to distribute donated supplies to displaced persons and to meet their immediate needs. 98 Local churches independently established hundreds of “pop-up” shelters to house storm victims. 99

More often than not, NGOs successfully contributed to the relief effort in spite of government obstacles and with almost no government support or direction. Time and again, government agencies did not effectively coordinate relief operations with NGOs. Often, government agencies failed to match relief needs with NGO and private sector capabilities. Even when agencies matched non-governmental aid with an identified need, there were problems moving goods, equipment, and people into the disaster area. For example, the government relief effort was unprepared to meet the fundamental food, housing, and operational needs of the surge volunteer force.

The Federal response should better integrate the contributions of volunteers and non-governmental organizations into the broader national effort. This integration would be best achieved at the State and local levels, prior to future incidents. In particular, State and local governments must engage NGOs in the planning process, credential their personnel, and provide them the necessary resource support for their involvement in a joint response.

- « Back to Table of Contents

- « Previous | Next »

- Appendix E - Endnotes »

Adding to the destruction following Hurricane Katrina, fires burn in parts of New Orleans in an apocalyptic scene from early on September 3, 2005. The storm struck the Gulf Coast with devastating force at daybreak on Aug. 29, 2005, pummeling a region that included New Orleans and neighboring Mississippi.

- ENVIRONMENT

Hurricane Katrina, explained

Hurricane Katrina was the costliest storm in U.S. history, and its effects are still felt today in New Orleans and coastal Louisiana.

Hurricane Katrina made landfall off the coast of Louisiana on August 29, 2005. It hit land as a Category 3 storm with winds reaching speeds as high as 120 miles per hour . Because of the ensuing destruction and loss of life, the storm is often considered one of the worst in U.S. history. An estimated 1,200 people died as a direct result of the storm, which also cost an estimated $108 billion in property damage , making it the costliest storm on record.

The devastating aftermath of Hurricane Katrina exposed a series of deep-rooted problems, including controversies over the federal government's response , difficulties in search-and-rescue efforts, and lack of preparedness for the storm, particularly with regard to the city's aging series of levees—50 of which failed during the storm, significantly flooding the low-lying city and causing much of the damage. Katrina's victims tended to be low income and African American in disproportionate numbers , and many of those who lost their homes faced years of hardship.

Ten years after the disaster, then-President Barack Obama said of Katrina , "What started out as a natural disaster became a man-made disaster—a failure of government to look out for its own citizens."

( What are hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons ?)

The city of New Orleans and other coastal communities in Katrina's path remain significantly altered more than a decade after the storm, both physically and culturally. The damage was so extensive that some pundits had argued, controversially, that New Orleans should be permanently abandoned , even as the city vowed to rebuild.

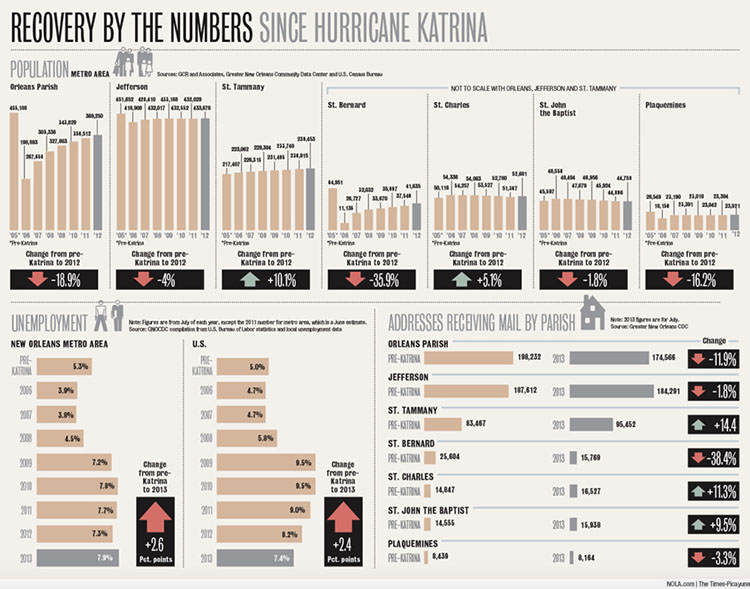

The population of New Orleans fell by more than half in the year after Katrina, according to Data Center Research . As of this writing, the population had grown back to nearly 80 percent of where it was before the hurricane.

Timeline of a Storm