Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

How two PhD students overcame the odds to snag tenure-track jobs

Adopt universal standards for study adaptation to boost health, education and social-science research

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Academic Writing

- Strategies for Writing

- Punctuation

- Plagiarism & Self-Plagiarism

How to Build a Literature Review

- PRISMA - Systematic reviews & meta-analyses

- Other Resources

- Using Zotero for Bibliographies

- Abstract Writing Tips

- Writing Assistance

- Locating a Journal

- Assessing Potential Journals

- Finding a Publisher

- Types of Peer Review

- Author Rights & Responsibilities

- Copyright Considerations

- What is a Lit Review?

- Why Write a Lit Review?

Structure of a Literature Review

Preliminary steps for literature review.

- Basic Example

- More Examples

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a comprehensive summary and analysis of previously published research on a particular topic. Literature reviews should give the reader an overview of the important theories and themes that have previously been discussed on the topic, as well as any important researchers who have contributed to the discourse. This review should connect the established conclusions to the hypothesis being presented in the rest of the paper.

What a Literature Review Is Not:

- Annotated Bibliography: An annotated bibliography summarizes and assesses each resource individually and separately. A literature review explores the connections between different articles to illustrate important themes/theories/research trends within a larger research area.

- Timeline: While a literature review can be organized chronologically, they are not simple timelines of previous events. They should not be a list of any kind. Individual examples or events should be combined to illustrate larger ideas or concepts.

- Argumentative Paper: Literature reviews are not meant to be making an argument. They are explorations of a concept to give the audience an understanding of what has already been written and researched about an idea. As many perspectives as possible should be included in a literature review in order to give the reader as comprehensive understanding of a topic as possible.

Why Write a Literature Review?

After reading the literature review, the reader should have a basic understanding of the topic. A reader should be able to come into your paper without really knowing anything about an idea, and after reading the literature, feel more confident about the important points.

A literature review should also help the reader understand the focus the rest of the paper will take within the larger topic. If the reader knows what has already been studied, they will be better prepared for the novel argument that is about to be made.

A literature review should help the reader understand the important history, themes, events, and ideas about a particular topic. Connections between ideas/themes should also explored. Part of the importance of a literature review is to prove to experts who do read your paper that you are knowledgeable enough to contribute to the academic discussion. You have to have done your homework.

A literature review should also identify the gaps in research to show the reader what hasn't yet been explored. Your thesis should ideally address one of the gaps identified in the research. Scholarly articles are meant to push academic conversations forward with new ideas and arguments. Before knowing where the gaps are in a topic, you need to have read what others have written.

As mentioned in other tabs, literature reviews should discuss the big ideas that make up a topic. Each literature review should be broken up into different subtopics. Each subtopic should use groups of articles as evidence to support the ideas. There are several different ways of organizing a literature review. It will depend on the patterns one sees in the groups of articles as to which strategy should be used. Here are a few examples of how to organize your review:

Chronological

If there are clear trends that change over time, a chronological approach could be used to organize a literature review. For example, one might argue that in the 1970s, the predominant theories and themes argued something. However, in the 1980s, the theories evolved to something else. Then, in the 1990s, theories evolved further. Each decade is a subtopic, and articles should be used as examples.

Themes/Theories

There may also be clear distinctions between schools of thought within a topic, a theoretical breakdown may be most appropriate. Each theory could be a subtopic, and articles supporting the theme should be included as evidence for each one.

If researchers mainly differ in the way they went about conducting research, literature reviews can be organized by methodology. Each type of method could be a subtopic, and articles using the method should be included as evidence for each one.

- Define your research question

- Compile a list of initial keywords to use for searching based on question

- Search for literature that discusses the topics surrounding your research question

- Assess and organize your literature into logical groups

- Identify gaps in research and conduct secondary searches (if necessary)

- Reassess and reorganize literature again (if necessary)

- Write review

Here is an example of a literature review, taken from the beginning of a research article. You can find other examples within most scholarly research articles. The majority of published scholarship includes a literature review section, and you can use those to become more familiar with these reviews.

Source: Perceptions of the Police by LGBT Communities

There are many books and internet resources about literature reviews though most are long on how to search and gather the literature. How to literally organize the information is another matter.

Some pro tips:

- Be thoughtful in naming the folders, sub-folders, and sub, sub-folders. Doing so really helps your thinking and concepts within your research topic.

- Be disciplined to add keywords under the tabs as this will help you search for ALL the items on your concepts/topics.

- Use the notes tab to add reminders, write bibliography/annotated bibliography

- Your literature review easily flows from your statement of purpose (SoP). Therefore, does your SoP say clearly and exactly the intent of your research? Your research assumption and argument is obvious?

- Begin with a topic outline that traces your argument. pg99: "First establish the line of argumentation you will follow (the thesis), whether it is an assertion, a contention, or a proposition.

- This means that you should have formed judgments about the topic based on the analysis and synthesis of the literature you are reviewing."

- Keep filling it in; flushing it out more deeply with your references

Other Resources/Examples

- ISU Writing Assistance The Julia N. Visor Academic Center provides one-on-one writing assistance for any course or need. By focusing on the writing process instead of merely on grammar and editing, we are committed to making you a better writer.

- University of Toronto: The Literature Review Written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre

- Purdue OWL - Writing a Lit Review Goes over the basic steps

- UW Madison Writing Center - Review of Literature A description of what each piece of a literature review should entail.

- USC Libraries - Literature Reviews Offers detailed guidance on how to develop, organize, and write a college-level research paper in the social and behavioral sciences.

- Creating the literature review: integrating research questions and arguments Blog post with very helpful overview for how to organize and build/integrate arguments in a literature review

- Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your “House” Article focusing on constructing a literature review for a dissertation. Still very relevant for literature reviews in other types of content.

A note that many of these examples will be far longer and in-depth than what's required for your assignment. However, they will give you an idea of the general structure and components of a literature review. Additionally, most scholarly articles will include a literature review section. Looking over the articles you have been assigned in classes will also help you.

- Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your “House” Excellent article detailing how to construct your literature review.

- Sample Literature Review (Univ. of Florida) This guide will provide research and writing tips to help students complete a literature review assignment.

- Sociology Literature Review (Univ. of Hawaii) Written in ASA citation style - don't follow this format.

- Sample Lit Review - Univ. of Vermont Includes an example with tips in the footnotes.

Attribution

Content on this page was provided by Grace Allbaugh

- << Previous: Writing a Literature Review

- Next: PRISMA - Systematic reviews & meta-analyses >>

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2023 3:23 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinoisstate.edu/academicwriting

Additional Links

- Directions and Parking

- Accessibility Services

- Library Spaces

- Staff Directory

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

How to Write a Literature Review

- What Is a Literature Review

What Is the Literature

- Writing the Review

The "literature" that is reviewed is the collection of publications (academic journal articles, books, conference proceedings, association papers, dissertations, etc) written by scholars and researchers for scholars and researchers. The professional literature is one (very significant) source of information for researchers, typically referred to as the secondary literature, or secondary sources. To use it, it is useful to know how it is created and how to access it.

The "Information Cycle"

The diagram below is a brief general picture of how scholarly literature is produced and used. Research does not have a beginning or an end; researchers build on work that has already been done in order to add to it, thus providing more resources for other researchers to build on. They read the professional literature of their field to see what issues, questions, and problems are current, then formulate a plan to address one or a few of those issues. Then they make a more focused review of the literature, which they use to refine their research plan. After carrying out the research, they present their results (presentations at conferences, published articles, etc) to other scholars in the field, i.e. they add to the general subject reading ("the literature").

Research may not have a beginning or an end, but researchers have to begin somewhere. As noted above, the professional literature is typically referred to as secondary sources. Primary and tertiary sources also play important roles in research. Note, though, that these labels are not rigid distinctions; the same resource can overlap categories.

- Lab reports (yours or someone else's) - Records of the results of experiments.

- Field notes, measurements, etc (yours or someone else's) - Records of observations of the natural world (electrons, elephants, earthquakes, etc).

- Journal articles, conference proceedings , and similar publications reporting results of original research.

- Historical documents - Official papers, maps, treaties, etc.

- Government publications - Census statistics, economic data, court reports, etc.

- Statistical data - Measurements (counts, surveys, etc.) compiled by researchers.

- First-person accounts - Diaries, memoirs, letters, interviews, speeches

- Newspapers - Some types of articles, e.g. stories on a breaking issue, or journalists reporting the results of their investigations.

- Published writings - Novels, stories, poems, essays, philosophical treatises, etc

- Works of art - Paintings, sculptures, etc.

- Recordings - audio, video, photographic

- Conference proceedings - Scholars and researchers getting together and presenting their latest ideas and findings

- Internet - Web sites that publish the author's findings or research; e.g. your professor's home page listing research results. Note: use extreme caution when using the Internet as a primary source … remember, anyone with internet access can post whatever they want.

- Archives - Records (minutes of meetings, purchase invoices, financial statements, etc.) of an organization (e.g. The Nature Conservancy), institution (e.g. Wesleyan University), business, or other group entity (even the Grateful Dead has an archivist on staff).

- Artifacts - manufactured items such as clothing, furniture, tools, buildings

- Manuscript collections - Collected writings, notes, letters, diaries, and other unpublished works.

- Books or articles - Depending on the purpose and perspective of your project, works intended as secondary sources -- analyzing or critiquing primary sources -- can serve as primary sources for your research.

- Secondary - Books, articles, and other writings by scholars and researchers reporting their analysis of their primary sources to others. They may be reporting the results of their own primary research or critiquing the work of others. As such, these sources are usually a major focus of a literature review: this is where you go to find out in detail what has been and is being done in a field, and thus to see how your work can contribute to the field.

- Summaries / Introductions - Encyclopedias, dictionaries, textbooks, yearbooks, and other sources which provide an introductory or summary state of the art of the research in the subject areas covered. They are an efficient means to quickly build a general framework for understanding a field.

- Indexes to publications - Provide lists of primary and secondary sources of more extensive information. They are an efficient means of finding books, articles, conference proceedings, and other publications in which scholars report the results of their research.

Work backwards . Usually, your research should begin with tertiary sources:

- Tertiary - Start by finding background information on your topic by consulting reference sources for introductions and summaries, and to find bibliographies or citations of secondary and primary sources.

- Secondary - Find books, articles, and other sources providing more extensive and thorough analyses of a topic. Check to see what other scholars have to say about your topic, find out what has been done and where there is a need for further research, and discover appropriate methodologies for carrying out that research.

- Primary - Now that you have a solid background knowledge of your topic and a plan for your own research, you are better able to understand, interpret, and analyze the primary source information. See if you can find primary source evidence to support or refute what other scholars have said about your topic, or posit an interpretation of your own and look for more primary sources or create more original data to confirm or refute your thesis. When you present your conclusions, you will have produced another secondary source to aid others in their research.

Publishing the Literature

There are a variety of avenues for scholars to report the results of their research, and each has a role to play in scholarly communication. Not all of these avenues result in official or easily findable publications, or even any publication at all. The categories of scholarly communication listed here are a general outline; keep in mind that they can vary in type and importance between disciplines.

Peer Review - An important part of academic publishing is the peer review, or refereeing, process. When a scholar submits an article to an academic journal or a book manuscript to a university publisher, the editors or publishers will send copies to other scholars and experts in that field who will review it. The reviewers will check to make sure the author has used methodologies appropriate to the topic, used those methodologies properly, taken other relevant work into account, and adequately supported the conclusions, as well as consider the relevance and importance to the field. A submission may be rejected, or sent back for revisions before being accepted for publication.

Peer review does not guarantee that an article or book is 100% correct. Rather, it provides a "stamp of approval" saying that experts in the field have judged this to be a worthy contribution to the professional discussion of an academic field.

Peer reviewed journals typically note that they are peer reviewed, usually somewhere in the first few pages of each issue. Books published by university presses typically go through a similar review process. Other book publishers may also have a peer review process. But the quality of the reviewing can vary among different book or journal publishers. Use academic book reviews or check how often and in what sources articles in a journal are cited, or ask a professor or two in the field, to get an idea of the reliability and importance of different authors, journals, and publishers.

Informal Sharing - In person or online, researchers discuss their ongoing projects to let others know what they are up to or to give or receive assistance in their work. Conferences, listservs, and online discussion boards are common avenues for these discussions. Increasingly, scholars are using personal web sites to present their work.

Conference Presentations - Many academic organizations sponsor conferences at which scholars read papers, display at poster sessions, or otherwise present the results of their work. To give a presentation, scholars must submit a proposal which is reviewed by those sponsoring the conference. Unless a presentation is published in another venue, it will likely be difficult to find a copy, or even to know what was presented. Some subject specific indexes and other sources list conference proceedings along with the author and contact information.

Conference Papers / Association Papers / Working Papers - Papers presented at a conference, submitted but not yet accepted for publication, works in progress, or not otherwise published are sometimes made available by academic associations. These are often not easy to find, but many are indexed in subject specific indexes or available in subject databases. Sometimes a collection of papers presented at a conference will be published in a book.

Journals - Articles in journals contain specific analyses of particular aspects of a topic. Journal articles can be written and published more quickly than books, academic libraries subscribe to many journals, and the contents of these journals are indexed in a variety of sources so others can easily find them. So, researchers commonly use articles to report their findings to a wide audience, and journals are a good readily available source for anyone researching current information on a topic.

- Research journals - Articles reporting in detail the results of research.

- Review journals - Articles reviewing the literature and work done on particular topics.

- News/Letters journals - News reports, brief research reports, short discussions of current issues.

- Proceedings/Transactions journals - A common venue for publishing conference papers or other proceedings of academic conferences.

- General interest magazines - News and other magazines that report scholarly findings for a general, nonacademic audience. These are usually written by journalists (who are usually not academically trained in the field), but sometimes are written by researchers (or at least by journalists with training in the field). Magazines are not peer reviewed, and are usually not academically useful sources of information for research purposes, but they can alert you to work being done in your field and give you a quick summary.

- Trade journals and magazines - These are written for people working in a particular industry or profession, such as advertising, banking, construction, dentistry, education. Articles are generally written by and for people working in that trade, and focus on current topics and developments in the trade. They do not present academic analyses of their topics, but they can provide useful background or context for academic work if the articles are relevant to your research.

Books - Books take a longer time than articles or conference presentations to get from research to publication, but they can cover a broader range of topics, or cover a topic much more thoroughly. University press books typically go through some sort of a peer review process. There is a wide range of review processes (from rigorous to none at all) among other book publishers.

Dissertations/Theses - Graduate students working on advanced degrees typically must perform a substantial piece of original work, and then present the results in the form of a thesis or dissertation. A master's thesis is typically somewhere between an article and a book in length, and a doctoral dissertation is typically about the length of a book. Both should include extensive bibliographies of their topics.

Web sites - In addition to researchers informally presenting and discussing their work on personal web pages, there are an increasing number of peer reviewed web sites publishing academic work. The rigor, and even existence, of peer reviewing can vary widely on the web, and it can be difficult to determine the reliability of information presented on the web, so always be careful in relying on a web-based information source. Do your own checking and reviewing to make sure the web site and the information it presents are reliable.

Reference Sources - Subject encyclopedias, dictionaries, and other reference sources present brief introductions to or summaries of the current work in a field or on a topic. These are typically produced by a scholar and/or publisher serving as an editor who invites submissions for articles from experts on the topics covered.

How to Find the Literature

Just as there are many avenues for the literature to be published and disseminated, there are many avenues for searching for and finding the literature. There are, for example, a variety of general and subject specific indexes which list citations to publications (books, articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, etc). The Wesleyan Library web site has links to the library catalog and many indexes and databases in which to search for resources, along with subject guides to list resources appropriate for specific academic disciplines. When you find some appropriate books, articles, etc, look in their bibliographies for other publications and also for other authors writing about the same topics. For research assistance tailored to your topic, you can sign up for a Personal Research Session with a librarian.

- << Previous: What Is a Literature Review

- Next: Writing the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

- Writing & Citing

- Paraphrasing

- Literature Reviews

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Database Citations

- BibTheo Style Guide

By the time you're reading this, you've probably written at least a few term papers during your time in school, whether at the high school or college level, but now you're in your major courses and professors are saying that it's time to write a "Literature Review." If this is the first time you're hearing of a paper like this, you're not alone! Literature reviews can seem overwhelming, but they are doable. This guide will help you determine what a literature review is, how to structure your literature review, how to summarize a journal article, and where to find your peer-reviewed resources.

What is a Literature Review?

There is one major difference between the term papers you've written before and the literature review you're writing now: Goal of the final product.

Term papers are written to research a specific topic that you have an opinion on and, in a way, provide informaiton to prove that your opinion is the most accurate according to the supporting research. You'll often find that term papers include things like counterarguments and emotion-weighted words. These aren't bad things! They're very important to term papers! However, literature reviews have a different end-goal.

Literature reviews are written to do one thing and one thing only: Review the literature. If you have an opinion on your topic (which, hopefully, you do!), the literature review is not the time to talk about it. For a literature review, you're going over the research that has already been done to establish a baseline of knowledge between you and your reader. You're looking to figure out what the experts already know and what they haven't figured out yet (also referred to as "gaps in the literature"). You're summarizing articles and drawing connections between them; not much more and not much less.

How to Structure a Literature View

If your professor has already given you an outline, ignore this box completely, and follow your professor's provided outline!

If you're writing your literature review from a blank slate, you can choose what kind of structure you want your literature review to have:

- Chronological = If you're writing about the history of a topic for your literature review, you can structure your review in such a way that indicates theory origins, early research, and more recent research and applications. For example, if you're researching applications for a theory like "Color Theory," then you may benefit most from a historical look from past to present.

- Topical = If your topic doesn't necessarily have a clear historical timeline or you're looking at a specific application of a theory, you'll likely need an outline that allows you to review topics of interest to your research. For example, if your topic is "Experiences of Hope in Religious Students," then you don't need to give a history; you only need to review current research that covers the topic you're looking for. Your topical outline may include headings like "Christianity and Experiences of Hope," "Buddhism and Experiences of Hope," etc. or "Elementary Students' Experiences of Hope," "Middle School Students' Experiences of Hope," etc.

- Synthetic = Honestly, don't pick this one unless you have to; this is the hardest kind of literature review to write, but is best if only a little bit of research has been done on your topic of interest. For example, if your topic is "Information seeking habits of squirrels on a college campus," not much research exists on this topic. Instead, you'll need to search for something like "how squirrels learn," "habits of squirrels on a college campus," and then combine (AKA synthesize) the information you found to draw conclusions where necessary. This is the most difficult structure because it requires advanced writing skills; this outline might be the right one if you're having trouble finding relevant resources to your topic, but talk to a librarian first, and see if we aren't able to help you find sources!

The structure you choose will determine how your outline is best set up; however, every outline should include both an introduction and a conclusion. Everything that's mentioned above is to help you figure out all the stuff in the middle.

Writing Your Conclusion & Introduction

Every term paper you've written up until now should have included an introduction and a conclusion, and your literature review is no different in that regard! Your conclusion will be the same as it has always been: A paragraph-ish summary of your paper, tying up all of your loose ends, and drawing any final conclusions for your reader. In literature reviews, your conclusion can (and should!) also include information on gaps in the literature; these are those areas or facets that very few people (or no one at all!) have researched yet. This is a great place to talk about where future research can go, including your current research that you're doing.

While your conclusion is still just a conclusion but with an extra flair, your introduction is likely to look a bit different than the ones you've written for past term papers. It's going to be much longer than 4-5 sentences, and it will include a great deal more in it. Here's something of an outline that you can consider for your introduction:

- Hook (an attention-catching statement that gets your reader to actually read your paper)

- Statistics (include any relevant statistics to your topic; consider things like how many people are affected by your topic)

- Definitions (define any terms/phrases/keywords you'll be using throughout your paper; even if you already think your reader knows the definition of an academic term, define it anyway to make sure you and your reader are on the same page) [Note: Figuring out what terms to define might be a bit tricky at first. Start with any term that could have multiple interpretations. For example, if your paper is about "Experiences of Hope in Religious Students," you may find it best to define the terms "Hope" and "Religious/Religion" so your readers don't misunderstand.]

- History (this is especially useful if you're doing a topical or synthetic outline, but it also applies to chronological; provide short biographical information, timelines, or key historical events to your topic.)

- Theories/Approached (this may not apply to every literature review or every topic, but, in general, think about whether or not there is already a baseline idea that your topic is based off of and discuss the main tenants of that theory/approach [e.g. "Cognitive Behavioral Theory" or "Catholocism"].)

- Thesis statement (avoid "I" and "You" statements like "In this paper, I am going to teach you about..." These statements aren't academic; if you need help formatting a thesis statement, you can visit the learning center on campus or reach out to writing center if you're online.)

Keep in mind that this is a generic/general outline. Your paper's introduction may include more (or even a little bit less!) than what's been listed here. It may be in a different order (maybe you define your terms and then give statistics). Not every introduction is going to look exactly the same, nor should they! As long as they give your reader the most basic understanding of what your paper discusses, you're well on your way to a passing literature review!

How to Summarize an Article

So we know now that a literature review, however it's structured, doesn't involve your own opinion. That leaves one major question: What does go in a literature review? What does "review the literature" actually mean? At the foundational level, what goes into a literature review are summaries of the peer-reviewed/scholarly/academic journal articles you find while researching. These summaries will help your readers understand what research already exists and how it applies to your theory or research topic. All you need to do after writing a summary is make the information connect by drawing bridges between articles, using transition statements (you can visit the Learning Center on campus or reach out to the Writing Center online if you need help with your writing and transitions), and pointing out agreements (or disagreements where appropriate!) in the research you're summarizing.

(Pro tip! Ever heard of an article abstract being referred to as that article's summary? The summaries you'll be writing and the article's abstract are pretty different. This means you can't just copy and paste an article's abstract into your paper. Not only is this not the right kind of summary your professor is looking for, this is also considered plagiarism. You can read an article abstract to help you figure out what might be important to your paper, but do not copy the abstract and paste it into your paper.)

Sounds simple enough, right? But if you've never summarized an article, how do you know what information to include? Our best recommendation is to use the following resource that was created and refined through a collaborative process between librarians and professors. This Journal Article Review Worksheet gives you step-by-step guidance on summarizing an article effectively and includes websites to help you determine key pieces of information like what kind of research you're looking at and how it can be used. After you've gotten all of your information into the worksheet, you can combine the aspects most important to your research/topic/theory into a 1-paragraph (sometimes 2-paragraph) summary that you'll be able to copy and paste into your literature review paper (don't forget to make your summary flow!).

- Journal Article Review Worksheet Note: While this document focuses primarily on research in the behavioral sciences (e.g. psychology research articles), the information should be relatively generalizable to most research articles. If this document isn't helpful, you don't have to use it at all, but it may be a good idea to look it over to understand the broad concepts of article summary.

Where to Find Peer-Reviewed/Academic/Scholarly Journal Articles

Finding your resources should be a breeze with Nelson Memorial Library's variety of databases and FAQs on how to search them! We recommend starting at the guide that's been created and curated with your subject in mind. Remember to choose the subject guide that matches the topic you're researching most closely (i.e. don't use the psychology subject guide for theological research or vis versa).

- Subject Guides

If you're having trouble figuring out how to use the databases you've found, check out our Library FAQs to see if we don't already have an answer for you!

THIS IS A TEST

If all else fails and you're still having trouble doing your research, never fear: That's exactly why your librarians are here to help you! You can schedule an appointment with any librarian by using our online scheduling service.

- << Previous: Paraphrasing

- Next: Primary & Secondary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 12:51 PM

- URL: https://sagu.libguides.com/writingciting

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

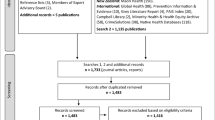

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations