- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2022

A systematic review on digital literacy

- Hasan Tinmaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4310-0848 1 ,

- Yoo-Taek Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1913-9059 2 ,

- Mina Fanea-Ivanovici ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2921-2990 3 &

- Hasnan Baber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8951-3501 4

Smart Learning Environments volume 9 , Article number: 21 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

61k Accesses

50 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The purpose of this study is to discover the main themes and categories of the research studies regarding digital literacy. To serve this purpose, the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier were searched with four keyword-combinations and final forty-three articles were included in the dataset. The researchers applied a systematic literature review method to the dataset. The preliminary findings demonstrated that there is a growing prevalence of digital literacy articles starting from the year 2013. The dominant research methodology of the reviewed articles is qualitative. The four major themes revealed from the qualitative content analysis are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and digital thinking. Under each theme, the categories and their frequencies are analysed. Recommendations for further research and for real life implementations are generated.

Introduction

The extant literature on digital literacy, skills and competencies is rich in definitions and classifications, but there is still no consensus on the larger themes and subsumed themes categories. (Heitin, 2016 ). To exemplify, existing inventories of Internet skills suffer from ‘incompleteness and over-simplification, conceptual ambiguity’ (van Deursen et al., 2015 ), and Internet skills are only a part of digital skills. While there is already a plethora of research in this field, this research paper hereby aims to provide a general framework of digital areas and themes that can best describe digital (cap)abilities in the novel context of Industry 4.0 and the accelerated pandemic-triggered digitalisation. The areas and themes can represent the starting point for drafting a contemporary digital literacy framework.

Sousa and Rocha ( 2019 ) explained that there is a stake of digital skills for disruptive digital business, and they connect it to the latest developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud technology, big data, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The topic is even more important given the large disparities in digital literacy across regions (Tinmaz et al., 2022 ). More precisely, digital inequalities encompass skills, along with access, usage and self-perceptions. These inequalities need to be addressed, as they are credited with a ‘potential to shape life chances in multiple ways’ (Robinson et al., 2015 ), e.g., academic performance, labour market competitiveness, health, civic and political participation. Steps have been successfully taken to address physical access gaps, but skills gaps are still looming (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010a ). Moreover, digital inequalities have grown larger due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they influenced the very state of health of the most vulnerable categories of population or their employability in a time when digital skills are required (Baber et al., 2022 ; Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ).

The systematic review the researchers propose is a useful updated instrument of classification and inventory for digital literacy. Considering the latest developments in the economy and in line with current digitalisation needs, digitally literate population may assist policymakers in various fields, e.g., education, administration, healthcare system, and managers of companies and other concerned organisations that need to stay competitive and to employ competitive workforce. Therefore, it is indispensably vital to comprehend the big picture of digital literacy related research.

Literature review

Since the advent of Digital Literacy, scholars have been concerned with identifying and classifying the various (cap)abilities related to its operation. Using the most cited academic papers in this stream of research, several classifications of digital-related literacies, competencies, and skills emerged.

Digital literacies

Digital literacy, which is one of the challenges of integration of technology in academic courses (Blau, Shamir-Inbal & Avdiel, 2020 ), has been defined in the current literature as the competencies and skills required for navigating a fragmented and complex information ecosystem (Eshet, 2004 ). A ‘Digital Literacy Framework’ was designed by Eshet-Alkalai ( 2012 ), comprising six categories: (a) photo-visual thinking (understanding and using visual information); (b) real-time thinking (simultaneously processing a variety of stimuli); (c) information thinking (evaluating and combining information from multiple digital sources); (d) branching thinking (navigating in non-linear hyper-media environments); (e) reproduction thinking (creating outcomes using technological tools by designing new content or remixing existing digital content); (f) social-emotional thinking (understanding and applying cyberspace rules). According to Heitin ( 2016 ), digital literacy groups the following clusters: (a) finding and consuming digital content; (b) creating digital content; (c) communicating or sharing digital content. Hence, the literature describes the digital literacy in many ways by associating a set of various technical and non-technical elements.

- Digital competencies

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.1.), the most recent framework proposed by the European Union, which is currently under review and undergoing an updating process, contains five competency areas: (a) information and data literacy, (b) communication and collaboration, (c) digital content creation, (d) safety, and (e) problem solving (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ). Digital competency had previously been described in a technical fashion by Ferrari ( 2012 ) as a set comprising information skills, communication skills, content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills, which later outlined the areas of competence in DigComp 2.1, too.

- Digital skills

Ng ( 2012 ) pointed out the following three categories of digital skills: (a) technological (using technological tools); (b) cognitive (thinking critically when managing information); (c) social (communicating and socialising). A set of Internet skill was suggested by Van Deursen and Van Dijk ( 2009 , 2010b ), which contains: (a) operational skills (basic skills in using internet technology), (b) formal Internet skills (navigation and orientation skills); (c) information Internet skills (fulfilling information needs), and (d) strategic Internet skills (using the internet to reach goals). In 2014, the same authors added communication and content creation skills to the initial framework (van Dijk & van Deursen). Similarly, Helsper and Eynon ( 2013 ) put forward a set of four digital skills: technical, social, critical, and creative skills. Furthermore, van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ) built a set of items and factors to measure Internet skills: operational, information navigation, social, creative, mobile. More recent literature (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) divides digital skills into seven core categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

It is worth mentioning that the various methodologies used to classify digital literacy are overlapping or non-exhaustive, which confirms the conceptual ambiguity mentioned by van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ).

- Digital thinking

Thinking skills (along with digital skills) have been acknowledged to be a significant element of digital literacy in the educational process context (Ferrari, 2012 ). In fact, critical thinking, creativity, and innovation are at the very core of DigComp. Information and Communication Technology as a support for thinking is a learning objective in any school curriculum. In the same vein, analytical thinking and interdisciplinary thinking, which help solve problems, are yet other concerns of educators in the Industry 4.0 (Ozkan-Ozen & Kazancoglu, 2021 ).

However, we have recently witnessed a shift of focus from learning how to use information and communication technologies to using it while staying safe in the cyber-environment and being aware of alternative facts. Digital thinking would encompass identifying fake news, misinformation, and echo chambers (Sulzer, 2018 ). Not least important, concern about cybersecurity has grown especially in times of political, social or economic turmoil, such as the elections or the Covid-19 crisis (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

Ultimately, this systematic review paper focuses on the following major research questions as follows:

Research question 1: What is the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers?

Research question 2: What are the research methods for digital literacy related papers?

Research question 3: What are the main themes in digital literacy related papers?

Research question 4: What are the concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers?

This study employed the systematic review method where the authors scrutinized the existing literature around the major research question of digital literacy. As Uman ( 2011 ) pointed, in systematic literature review, the findings of the earlier research are examined for the identification of consistent and repetitive themes. The systematic review method differs from literature review with its well managed and highly organized qualitative scrutiny processes where researchers tend to cover less materials from fewer number of databases to write their literature review (Kowalczyk & Truluck, 2013 ; Robinson & Lowe, 2015 ).

Data collection

To address major research objectives, the following five important databases are selected due to their digital literacy focused research dominance: 1. WoS/Clarivate Analytics, 2. Proquest Central; 3. Emerald Management Journals; 4. Jstor Business College Collections; 5. Scopus/Elsevier.

The search was made in the second half of June 2021, in abstract and key words written in English language. We only kept research articles and book chapters (herein referred to as papers). Our purpose was to identify a set of digital literacy areas, or an inventory of such areas and topics. To serve that purpose, systematic review was utilized with the following synonym key words for the search: ‘digital literacy’, ‘digital skills’, ‘digital competence’ and ‘digital fluency’, to find the mainstream literature dealing with the topic. These key words were unfolded as a result of the consultation with the subject matter experts (two board members from Korean Digital Literacy Association and two professors from technology studies department). Below are the four key word combinations used in the search: “Digital literacy AND systematic review”, “Digital skills AND systematic review”, “Digital competence AND systematic review”, and “Digital fluency AND systematic review”.

A sequential systematic search was made in the five databases mentioned above. Thus, from one database to another, duplicate papers were manually excluded in a cascade manner to extract only unique results and to make the research smoother to conduct. At this stage, we kept 47 papers. Further exclusion criteria were applied. Thus, only full-text items written in English were selected, and in doing so, three papers were excluded (no full text available), and one other paper was excluded because it was not written in English, but in Spanish. Therefore, we investigated a total number of 43 papers, as shown in Table 1 . “ Appendix A ” shows the list of these papers with full references.

Data analysis

The 43 papers selected after the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively, were reviewed the materials independently by two researchers who were from two different countries. The researchers identified all topics pertaining to digital literacy, as they appeared in the papers. Next, a third researcher independently analysed these findings by excluded duplicates A qualitative content analysis was manually performed by calculating the frequency of major themes in all papers, where the raw data was compared and contrasted (Fraenkel et al., 2012 ). All three reviewers independently list the words and how the context in which they appeared and then the three reviewers collectively decided for how it should be categorized. Lastly, it is vital to remind that literature review of this article was written after the identification of the themes appeared as a result of our qualitative analyses. Therefore, the authors decided to shape the literature review structure based on the themes.

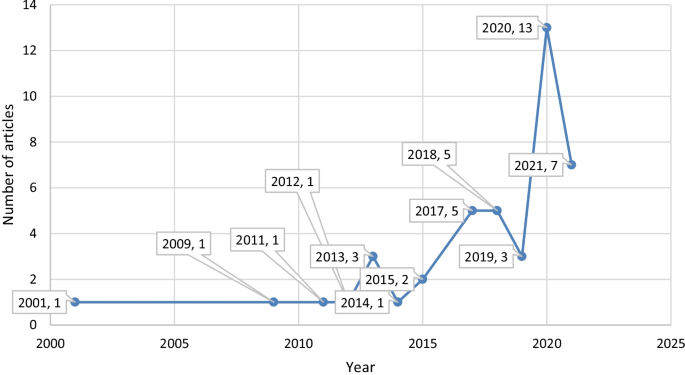

As an answer to the first research question (the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers), Fig. 1 demonstrates the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers. It is seen that there is an increasing trend about the digital literacy papers.

Yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers

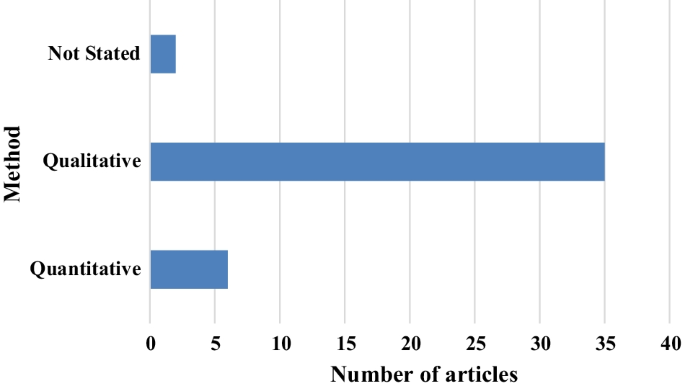

Research question number two (The research methods for digital literacy related papers) concentrates on what research methods are employed for these digital literacy related papers. As Fig. 2 shows, most of the papers were using the qualitative method. Not stated refers to book chapters.

Research methods used in the reviewed articles

When forty-three articles were analysed for the main themes as in research question number three (The main themes in digital literacy related papers), the overall findings were categorized around four major themes: (i) literacies, (ii) competencies, (iii) skills, and (iv) thinking. Under every major theme, the categories were listed and explained as in research question number four (The concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers).

The authors utilized an overt categorization for the depiction of these major themes. For example, when the ‘creativity’ was labelled as a skill, the authors also categorized it under the ‘skills’ theme. Similarly, when ‘creativity’ was mentioned as a competency, the authors listed it under the ‘competencies’ theme. Therefore, it is possible to recognize the same finding under different major themes.

Major theme 1: literacies

Digital literacy being the major concern of this paper was observed to be blatantly mentioned in five papers out forty-three. One of these articles described digital literacy as the human proficiencies to live, learn and work in the current digital society. In addition to these five articles, two additional papers used the same term as ‘critical digital literacy’ by describing it as a person’s or a society’s accessibility and assessment level interaction with digital technologies to utilize and/or create information. Table 2 summarizes the major categories under ‘Literacies’ major theme.

Computer literacy, media literacy and cultural literacy were the second most common literacy (n = 5). One of the article branches computer literacy as tool (detailing with software and hardware uses) and resource (focusing on information processing capacity of a computer) literacies. Cultural literacy was emphasized as a vital element for functioning in an intercultural team on a digital project.

Disciplinary literacy (n = 4) was referring to utilizing different computer programs (n = 2) or technical gadgets (n = 2) with a specific emphasis on required cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills to be able to work in any digital context (n = 3), serving for the using (n = 2), creating and applying (n = 2) digital literacy in real life.

Data literacy, technology literacy and multiliteracy were the third frequent categories (n = 3). The ‘multiliteracy’ was referring to the innate nature of digital technologies, which have been infused into many aspects of human lives.

Last but not least, Internet literacy, mobile literacy, web literacy, new literacy, personal literacy and research literacy were discussed in forty-three article findings. Web literacy was focusing on being able to connect with people on the web (n = 2), discover the web content (especially the navigation on a hyper-textual platform), and learn web related skills through practical web experiences. Personal literacy was highlighting digital identity management. Research literacy was not only concentrating on conducting scientific research ability but also finding available scholarship online.

Twenty-four other categories are unfolded from the results sections of forty-three articles. Table 3 presents the list of these other literacies where the authors sorted the categories in an ascending alphabetical order without any other sorting criterion. Primarily, search, tagging, filtering and attention literacies were mainly underlining their roles in information processing. Furthermore, social-structural literacy was indicated as the recognition of the social circumstances and generation of information. Another information-related literacy was pointed as publishing literacy, which is the ability to disseminate information via different digital channels.

While above listed personal literacy was referring to digital identity management, network literacy was explained as someone’s social networking ability to manage the digital relationship with other people. Additionally, participatory literacy was defined as the necessary abilities to join an online team working on online content production.

Emerging technology literacy was stipulated as an essential ability to recognize and appreciate the most recent and innovative technologies in along with smart choices related to these technologies. Additionally, the critical literacy was added as an ability to make smart judgements on the cost benefit analysis of these recent technologies.

Last of all, basic, intermediate, and advanced digital assessment literacies were specified for educational institutions that are planning to integrate various digital tools to conduct instructional assessments in their bodies.

Major theme 2: competencies

The second major theme was revealed as competencies. The authors directly categorized the findings that are specified with the word of competency. Table 4 summarizes the entire category set for the competencies major theme.

The most common category was the ‘digital competence’ (n = 14) where one of the articles points to that category as ‘generic digital competence’ referring to someone’s creativity for multimedia development (video editing was emphasized). Under this broad category, the following sub-categories were associated:

Problem solving (n = 10)

Safety (n = 7)

Information processing (n = 5)

Content creation (n = 5)

Communication (n = 2)

Digital rights (n = 1)

Digital emotional intelligence (n = 1)

Digital teamwork (n = 1)

Big data utilization (n = 1)

Artificial Intelligence utilization (n = 1)

Virtual leadership (n = 1)

Self-disruption (in along with the pace of digitalization) (n = 1)

Like ‘digital competency’, five additional articles especially coined the term as ‘digital competence as a life skill’. Deeper analysis demonstrated the following points: social competences (n = 4), communication in mother tongue (n = 3) and foreign language (n = 2), entrepreneurship (n = 3), civic competence (n = 2), fundamental science (n = 1), technology (n = 1) and mathematics (n = 1) competences, learning to learn (n = 1) and self-initiative (n = 1).

Moreover, competencies were linked to workplace digital competencies in three articles and highlighted as significant for employability (n = 3) and ‘economic engagement’ (n = 3). Digital competencies were also detailed for leisure (n = 2) and communication (n = 2). Furthermore, two articles pointed digital competencies as an inter-cultural competency and one as a cross-cultural competency. Lastly, the ‘digital nativity’ (n = 1) was clarified as someone’s innate competency of being able to feel contented and satisfied with digital technologies.

Major theme 3: skills

The third major observed theme was ‘skills’, which was dominantly gathered around information literacy skills (n = 19) and information and communication technologies skills (n = 18). Table 5 demonstrates the categories with more than one occurrence.

Table 6 summarizes the sub-categories of the two most frequent categories of ‘skills’ major theme. The information literacy skills noticeably concentrate on the steps of information processing; evaluation (n = 6), utilization (n = 4), finding (n = 3), locating (n = 2) information. Moreover, the importance of trial/error process, being a lifelong learner, feeling a need for information and so forth were evidently listed under this sub-category. On the other hand, ICT skills were grouped around cognitive and affective domains. For instance, while technical skills in general and use of social media, coding, multimedia, chat or emailing in specific were reported in cognitive domain, attitude, intention, and belief towards ICT were mentioned as the elements of affective domain.

Communication skills (n = 9) were multi-dimensional for different societies, cultures, and globalized contexts, requiring linguistic skills. Collaboration skills (n = 9) are also recurrently cited with an explicit emphasis for virtual platforms.

‘Ethics for digital environment’ encapsulated ethical use of information (n = 4) and different technologies (n = 2), knowing digital laws (n = 2) and responsibilities (n = 2) in along with digital rights and obligations (n = 1), having digital awareness (n = 1), following digital etiquettes (n = 1), treating other people with respect (n = 1) including no cyber-bullying (n = 1) and no stealing or damaging other people (n = 1).

‘Digital fluency’ involved digital access (n = 2) by using different software and hardware (n = 2) in online platforms (n = 1) or communication tools (n = 1) or within programming environments (n = 1). Digital fluency also underlined following recent technological advancements (n = 1) and knowledge (n = 1) including digital health and wellness (n = 1) dimension.

‘Social intelligence’ related to understanding digital culture (n = 1), the concept of digital exclusion (n = 1) and digital divide (n = 3). ‘Research skills’ were detailed with searching academic information (n = 3) on databases such as Web of Science and Scopus (n = 2) and their citation, summarization, and quotation (n = 2).

‘Digital teaching’ was described as a skill (n = 2) in Table 4 whereas it was also labelled as a competence (n = 1) as shown in Table 3 . Similarly, while learning to learn (n = 1) was coined under competencies in Table 3 , digital learning (n = 2, Table 4 ) and life-long learning (n = 1, Table 5 ) were stated as learning related skills. Moreover, learning was used with the following three terms: learning readiness (n = 1), self-paced learning (n = 1) and learning flexibility (n = 1).

Table 7 shows other categories listed below the ‘skills’ major theme. The list covers not only the software such as GIS, text mining, mapping, or bibliometric analysis programs but also the conceptual skills such as the fourth industrial revolution and information management.

Major theme 4: thinking

The last identified major theme was the different types of ‘thinking’. As Table 8 shows, ‘critical thinking’ was the most frequent thinking category (n = 4). Except computational thinking, the other categories were not detailed.

Computational thinking (n = 3) was associated with the general logic of how a computer works and sub-categorized into the following steps; construction of the problem (n = 3), abstraction (n = 1), disintegration of the problem (n = 2), data collection, (n = 2), data analysis (n = 2), algorithmic design (n = 2), parallelization & iteration (n = 1), automation (n = 1), generalization (n = 1), and evaluation (n = 2).

A transversal analysis of digital literacy categories reveals the following fields of digital literacy application:

Technological advancement (IT, ICT, Industry 4.0, IoT, text mining, GIS, bibliometric analysis, mapping data, technology, AI, big data)

Networking (Internet, web, connectivity, network, safety)

Information (media, news, communication)

Creative-cultural industries (culture, publishing, film, TV, leisure, content creation)

Academia (research, documentation, library)

Citizenship (participation, society, social intelligence, awareness, politics, rights, legal use, ethics)

Education (life skills, problem solving, teaching, learning, education, lifelong learning)

Professional life (work, teamwork, collaboration, economy, commerce, leadership, decision making)

Personal level (critical thinking, evaluation, analytical thinking, innovative thinking)

This systematic review on digital literacy concentrated on forty-three articles from the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier. The initial results revealed that there is an increasing trend on digital literacy focused academic papers. Research work in digital literacy is critical in a context of disruptive digital business, and more recently, the pandemic-triggered accelerated digitalisation (Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ; Sousa & Rocha 2019 ). Moreover, most of these papers were employing qualitative research methods. The raw data of these articles were analysed qualitatively using systematic literature review to reveal major themes and categories. Four major themes that appeared are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and thinking.

Whereas the mainstream literature describes digital literacy as a set of photo-visual, real-time, information, branching, reproduction and social-emotional thinking (Eshet-Alkalai, 2012 ) or as a set of precise specific operations, i.e., finding, consuming, creating, communicating and sharing digital content (Heitin, 2016 ), this study reveals that digital literacy revolves around and is in connection with the concepts of computer literacy, media literacy, cultural literacy or disciplinary literacy. In other words, the present systematic review indicates that digital literacy is far broader than specific tasks, englobing the entire sphere of computer operation and media use in a cultural context.

The digital competence yardstick, DigComp (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ) suggests that the main digital competencies cover information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving. Similarly, the findings of this research place digital competencies in relation to problem solving, safety, information processing, content creation and communication. Therefore, the findings of the systematic literature review are, to a large extent, in line with the existing framework used in the European Union.

The investigation of the main keywords associated with digital skills has revealed that information literacy, ICT, communication, collaboration, digital content creation, research and decision-making skill are the most representative. In a structured way, the existing literature groups these skills in technological, cognitive, and social (Ng, 2012 ) or, more extensively, into operational, formal, information Internet, strategic, communication and content creation (van Dijk & van Deursen, 2014 ). In time, the literature has become richer in frameworks, and prolific authors have improved their results. As such, more recent research (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) use the following categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Whereas digital thinking was observed to be mostly related with critical thinking and computational thinking, DigComp connects it with critical thinking, creativity, and innovation, on the one hand, and researchers highlight fake news, misinformation, cybersecurity, and echo chambers as exponents of digital thinking, on the other hand (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

This systematic review research study looks ahead to offer an initial step and guideline for the development of a more contemporary digital literacy framework including digital literacy major themes and factors. The researchers provide the following recommendations for both researchers and practitioners.

Recommendations for prospective research

By considering the major qualitative research trend, it seems apparent that more quantitative research-oriented studies are needed. Although it requires more effort and time, mixed method studies will help understand digital literacy holistically.

As digital literacy is an umbrella term for many different technologies, specific case studies need be designed, such as digital literacy for artificial intelligence or digital literacy for drones’ usage.

Digital literacy affects different areas of human lives, such as education, business, health, governance, and so forth. Therefore, different case studies could be carried out for each of these unique dimensions of our lives. For instance, it is worth investigating the role of digital literacy on lifelong learning in particular, and on education in general, as well as the digital upskilling effects on the labour market flexibility.

Further experimental studies on digital literacy are necessary to realize how certain variables (for instance, age, gender, socioeconomic status, cognitive abilities, etc.) affect this concept overtly or covertly. Moreover, the digital divide issue needs to be analysed through the lens of its main determinants.

New bibliometric analysis method can be implemented on digital literacy documents to reveal more information on how these works are related or centred on what major topic. This visual approach will assist to realize the big picture within the digital literacy framework.

Recommendations for practitioners

The digital literacy stakeholders, policymakers in education and managers in private organizations, need to be aware that there are many dimensions and variables regarding the implementation of digital literacy. In that case, stakeholders must comprehend their beneficiaries or the participants more deeply to increase the effect of digital literacy related activities. For example, critical thinking and problem-solving skills and abilities are mentioned to affect digital literacy. Hence, stakeholders have to initially understand whether the participants have enough entry level critical thinking and problem solving.

Development of digital literacy for different groups of people requires more energy, since each group might require a different set of skills, abilities, or competencies. Hence, different subject matter experts, such as technologists, instructional designers, content experts, should join the team.

It is indispensably vital to develop different digital frameworks for different technologies (basic or advanced) or different contexts (different levels of schooling or various industries).

These frameworks should be updated regularly as digital fields are evolving rapidly. Every year, committees should gather around to understand new technological trends and decide whether they should address the changes into their frameworks.

Understanding digital literacy in a thorough manner can enable decision makers to correctly implement and apply policies addressing the digital divide that is reflected onto various aspects of life, e.g., health, employment, education, especially in turbulent times such as the COVID-19 pandemic is.

Lastly, it is also essential to state the study limitations. This study is limited to the analysis of a certain number of papers, obtained from using the selected keywords and databases. Therefore, an extension can be made by adding other keywords and searching other databases.

Availability of data and materials

The authors present the articles used for the study in “ Appendix A ”.

Baber, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., Lee, Y. T., & Tinmaz, H. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of digital literacy research and emerging themes pre-during COVID-19 pandemic. Information and Learning Sciences . https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-10-2021-0090 .

Article Google Scholar

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111 , 10642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Avdiel, O. (2020). How does the pedagogical design of a technology-enhanced collaborative academic course promote digital literacies, self-regulation, and perceived learning of students? The Internet and Higher Education, 45 , 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100722

Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with eight proficiency levels and examples of use (No. JRC106281). Joint Research Centre, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC106281

Eshet, Y. (2004). Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia , 13 (1), 93–106, https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/4793/

Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 9 (2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.28945/1621

Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. JCR IPTS, Sevilla. https://ifap.ru/library/book522.pdf

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education (8th ed.). Mc Graw Hill.

Google Scholar

Heitin, L. (2016). What is digital literacy? Education Week, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/what-is-digital-literacy/2016/11

Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2013). Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. European Journal of Communication, 28 (6), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113499113

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference ? . Radiologic Technology, 85 (2), 219–222.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59 (3), 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016

Ozkan-Ozen, Y. D., & Kazancoglu, Y. (2021). Analysing workforce development challenges in the Industry 4.0. International Journal of Manpower . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2021-0167

Puig, B., Blanco-Anaya, P., & Perez-Maceira, J. J. (2021). “Fake News” or Real Science? Critical thinking to assess information on COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 6 , 646909. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.646909

Robinson, L., Cotten, S. R., Ono, H., Quan-Haase, A., Mesch, G., Chen, W., Schulz, J., Hale, T. M., & Stern, M. J. (2015). Digital inequalities and why they matter. Information, Communication & Society, 18 (5), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1012532

Robinson, P., & Lowe, J. (2015). Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39 (2), 103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393

Sousa, M. J., & Rocha, A. (2019). Skills for disruptive digital business. Journal of Business Research, 94 , 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.051

Sulzer, A. (2018). (Re)conceptualizing digital literacies before and after the election of Trump. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 17 (2), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-06-2017-0098

Tinmaz, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A snapshot of digital literacy. Library Hi Tech News , (ahead-of-print).

Uman, L. S. (2011). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20 (1), 57–59.

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2015). Development and validation of the Internet Skills Scale (ISS). Information, Communication & Society, 19 (6), 804–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1078834

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2009). Using the internet: Skills related problems in users’ online behaviour. Interacting with Computers, 21 , 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2009.06.005

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010a). Measuring internet skills. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 26 (10), 891–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2010.496338

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010b). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 13 (6), 893–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810386774

van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & Van Deursen, A. J. A. M. (2014). Digital skills, unlocking the information society . Palgrave MacMillan.

van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & de Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computer in Human Behavior, 72 , 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Download references

This research is funded by Woosong University Academic Research in 2022.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

AI & Big Data Department, Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Hasan Tinmaz

Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Yoo-Taek Lee

Department of Economics and Economic Policies, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

Mina Fanea-Ivanovici

Abu Dhabi School of Management, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Hasnan Baber

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors worked together on the manuscript equally. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hasnan Baber .

Ethics declarations

Competing of interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tinmaz, H., Lee, YT., Fanea-Ivanovici, M. et al. A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learn. Environ. 9 , 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Download citation

Received : 23 February 2022

Accepted : 01 June 2022

Published : 08 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital literacy

- Systematic review

- Qualitative research

Advertisement

From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework

- Development Article

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2020

- Volume 68 , pages 2449–2472, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Garry Falloon 1

129k Accesses

336 Citations

64 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Over the years, a variety of frameworks, models and literacies have been developed to guide teacher educators in their efforts to build digital capabilities in their students, that will support them to use new and emerging technologies in their future classrooms. Generally, these focus on advancing students’ skills in using ‘educational’ applications and digitally-sourced information, or understanding effective blends of pedagogical, content and technological knowledge seen as supporting the integration of digital resources into teaching, to enhance subject learning outcomes. Within teacher education institutions courses developing these capabilities are commonly delivered as standalone entities, or there is an assumption that they will be generated by technology’s integration in other disciplines or through mandated assessment. However, significant research exists suggesting the current narrow focus on subject-related technical and information skills does not prepare students adequately with the breadth of knowledge and capabilities needed in today’s classrooms, and beyond. This article presents a conceptual framework introducing an expanded view of teacher digital competence (TDC). It moves beyond prevailing technical and literacies conceptualisations, arguing for more holistic and broader-based understandings that recognise the increasingly complex knowledge and skills young people need to function ethically, safely and productively in diverse, digitally-mediated environments. The implications of the framework are discussed, with specific reference to its interdisciplinary nature and the requirement of all faculty to engage purposefully and deliberately in delivering its objectives. Practical suggestions on how the framework might be used by faculty, are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital Skill Mythology and Understanding in Preservice Teachers

Next-Generation Digital Curricula for Future Teaching and Learning

An Integrated Model of Digitalisation-Related Competencies in Teacher Education

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The problem of better-preparing teacher education students to use digital technologies effectively and productively in schools is an enduring issue (Guzman and Nussbaum 2009 ; Otero et al. 2005 ; Sutton 2011 ). Traditionally, teacher education providers have opted for isolated ICT courses or units, often positioned early in the students’ qualification programme. These are delivered on the assumption that ‘front loading’ students with what are perceived as essential knowledge and skills, will support them to complete course assessment requirements—such as developing ‘technology integrated’ units of learning, for practicum work in schools, and by implication, helping them use digital technology effectively in their later teaching career (Kleiner et al. 2007 ; Polly et al. 2010 ). These courses generally focus on building students’ confidence and attitudes towards using digital resources in teaching and learning, and developing the requisite hardware and software skills to facilitate this (Foulger et al. 2012 ).

However, a growing body of research suggests this approach is ineffective for building broader and deeper understandings of the knowledge and capabilities needed by teachers educating students for future life, and it has been criticised for its narrow focus on contextually-devoid, isolated technical skills (e.g., Ferrari 2012 ; Janssen et al. 2013 ; Ottestad et al. 2014 ). While there is general agreement about the need to develop and implement alternative approaches to teacher preparation that reflect a more holistic and integrated approach that addresses students’ concerns of “a disconnect between their technology training and the rest of their teacher preparation program” (Sutton 2011 , p. 43), debate exists about exactly how this should be done, and what programmes of this nature should comprise.

Digital literacy or digital competence?

Traditional approaches to developing digital capabilities in teacher education have focused on promoting students’ ‘digital literacy’ (Borthwick and Hansen 2017 ). This term first emerged around 1997, when Paul Gilster introduced it in his book as:

…a set of skills to access the internet, find, manage and edit digital information; join in communications, and otherwise engage with an online information and communication network. Digital literacy is the ability to properly use and evaluate digital resources, tools and services, and apply it to lifelong learning processes ( 1997 , p. 220).

Since that time the concept has become increasingly contested as new technologies and new applications for technology have emerged, many of which have been spawned by progressively ubiquitous access to the internet, and the proliferation of personal, mobile digital devices. Terms such as ‘information literacy’ (Zurkowski 1974 ), ‘computer literacy’ (Tsai 2002 ), ‘internet literacy’ (Harrison 2017 ), ‘media literacy’ (Christ and Potter 1998 ) and recently, ‘multi-modal literacy’ (Heydon 2007 ) have all been associated with effective use of digital resources in teaching and learning, and have been promoted as components of an inclusive view of digital literacy (Grusczynska and Pountney 2013 ). As Helsper ( 2008 ) identifies, reaching a singular definition of digital literacy is challenging, due to constantly evolving technological, cultural and societal landscapes redefining what, when and how digital technologies are used in personal and professional activities.

In terms of teacher education, producing digitally-literate students has generally meant the prioritisation of technical skills in using digital tools and systems deemed appropriate to educational settings, and identifying how these can be used within particular units of learning (Admiraal et al. 2016 ). This approach assumes that doing this, “equips pre-service teachers with a set of basic competencies they can transfer to their future classroom practice” (Admiraal et al. 2016 , p. 106). However, these approaches have been criticised for their narrow skills focus, lack of authenticity, failure to take account of different socio-cultural contexts for technology use, and their ineffective, reductive design (Gruszczynska et al. 2013 ; Lim et al. 2011 ; Lund et al. 2014 ; Ottestad et al. 2014 ). Others have identified limitations in their overly technical approach that ignores wider considerations, including ethical, digital citizenship, health, wellbeing, safety and social/collaborative elements (Foulger et al. 2017 ; Hinrichsen and Coombs 2013 ). More recent studies have called for a reconceptualisation of the outcomes of teacher education programmes, suggesting the present skills-focused digital literacy emphasis be abandoned, in favour of broader digital competency models that recognise the more diverse knowledge, capabilities and dispositions needed by future teachers.

In considering the nature of general digital competence, Janssen et al. comment that:

…digital competency clearly involves more than knowing how to use devices and applications… which is intricately connected with skills to communicate with ICT, as well as information skills. Sensible and healthy use of ICT requires particular knowledge and attitudes regarding legal and ethical aspects, privacy and security, as well as understanding the role of ICT in society and a balanced attitude towards technology… (Janssen et al. 2013 , p. 480).

While this conceptualisation acknowledges the relevance and importance of technical knowledge and skills, it adopts a wider socio-cultural stance by signalling the need to understand and consider broader implications and effects of digital technologies on individuals and society. It also introduces dispositional and attitudinal elements—or what Janssen et al. ( 2013 ) terms developing a “mind-set” (p. 474) towards technological innovations, in an effort to better understand and critically appraise their role and influence in forming new practices. This represents a considerable challenge for teacher educators, who not only need to better support their students to more effectively utilise digital resources in their future classrooms, but must also help them understand and develop a concern for broader considerations around technology use, and its impacts. Additionally, the notion of competence implies a need for constant revision, reflecting changes to technological systems and uses that, “take into account the evolving nature of technologies” (Janssen et al. 2013 , p. 474). This requires teacher educators to constantly reflect on current capabilities and needs and where necessary access professional learning, responding to rapidly changing educational environments and opportunities afforded by emerging technology innovations.

Existing frameworks guiding teacher digital capability development

Supporting development of the teacher digital competency framework introduced in this article, a scoping review of literature was undertaken investigating the characteristics of some present frameworks commonly used in teacher education. The purpose of the review was not to develop a definitive summary encompassing all frameworks. Instead, it overviewed frameworks that had been developed specifically for teacher education, made reference to possible application in teacher education, or had been researched and reported on within teacher education contexts, to identify the extent to which they represented a holistic interpretation of digital competence as described by Janssen et al. ( 2013 ). To facilitate this, a multi-database search was completed using various combinations of the keywords: teacher, education, teaching, digital, literacy, skills, competencies, ICT, technology, capabilities, information. From the results, a selection of frequently occurring frameworks considered most aligned with teacher education were selected for analysis (i.e., ones conceptualised, implemented or researched in teacher education contexts). A summary of these is presented in “ Appendix ”. In interpreting the table, different sized black circles have been used to indicate the level of emphasis given in each framework to skills development (S), pedagogical (P) and curriculum (C) changes, dispositional/attitudinal factors (Disp.) and personal considerations (Pers.). These are further defined in the notes section at the bottom of the table.

As indicated in the table there is a solid emphasis in most frameworks on skills development, although only TPACK, the UNESCO framework and to a lesser extent the ISTE standards, explicitly linked these to associated changes in pedagogy and curriculum. Skills generally focused on technical/operational aspects of ICT and information skills—specifically how to use devices and software to access, work with and evaluate information for a range of curriculum and teaching purposes, and the type of thinking associated with this (e.g., analysis, evaluation, critical). The frameworks were also quite different in structure, with the ISTE standards, UNESCO competencies and ICTE-MM maturity model adopting universal ‘checklist’ formats, while the others were more conceptual (broader ideas informing bespoke development). Notably, no existing frameworks included more than a passing mention of personal dispositions/attitudes or understandings of wider issues or safety and wellbeing (etc.) considerations, as components of teacher education students’ digital competence.

Two conceptual frameworks were indicated in literature as frequently used for informing the design of teacher education digital capability programmes, and were well-supported by empirical research. They were Mishra and Koehler’s ( 2006 ) TPACK framework (e.g., Graziano et al. 2017 ; Kimmons and Hall 2018 ; Krause and Lynch 2016 ; Reyes et al. 2017 ; Tan et al. 2019 ; Voogt and McKenney 2017 ) and Puentedura’s ( 2006 ) SAMR model (e.g., Aldosemani 2019 ; Baz et al. 2018 ; Beisel 2017 ; Kihoza et al. 2016 ; Sardone 2019 ). The next section investigates these frameworks in more detail, evaluating each for their capacity to support teacher educators in their efforts to foster broadly-based digital competence in their students.

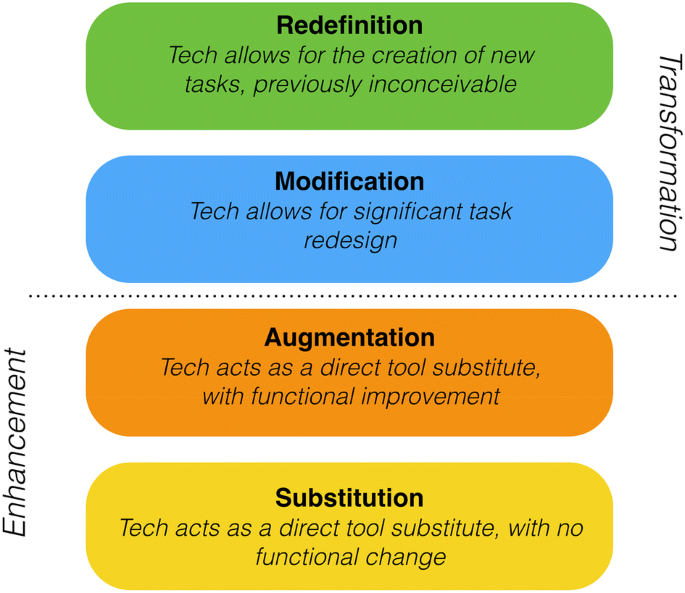

SAMR (substitution, augmentation, modification, redefinition) is essentially a descriptive framework that maps different educational uses of technology hierarchically against levels or stages—progressing from Substitution (‘doing digitally’ what has traditionally been carried out using conventional resources) through to Redefinition (curriculum, pedagogy and practice reconceptualised through digital technologies). SAMR has been widely adopted by teacher educators and schools as a pragmatic guide for signposting ICT development progress, as they work towards what is seen as the utopian position of curriculum Redefinition through technology (Geer et al. 2017 ; Hilton 2016 ). According to Puentedura ( 2006 ), at the Redefinition stage, “technology allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable” (slide 3)—tasks, he claims, that align with the exercise of higher order thinking capabilities such as analysing, evaluating and creating. At the Substitution stage, “technology acts as a direct tool substitute with no functional change” (slide 3), which Puentedura ( 2006 ) aligns with lower order thinking capabilities, such as understanding and remembering. The Augmentation and Modification stages represent intermediate steps between Substitution and Redefinition, describing increasing complexity and sophistication in using technology to facilitate changes to learning design and pedagogy, progressively supporting greater levels of curriculum innovation (Fig. 1 ).

The SAMR model (from Puentedura 2006 )

While the SAMR framework may be useful for pre-service and practicing teachers by providing descriptive ‘aim points’ towards which to evolve their practice, it does not provide concrete illustrations of the sort of practices that might represent each stage, or ways of transitioning through the stages—nor does it explicitly account for supporting and necessary pedagogical, technological and learning design changes. Although appealing possibly because of its simplicity, SAMR focuses solely on describing levels of subject-based technology integration, reflecting a narrow interpretation of the understandings teacher education students need for the more holistic and comprehensive capability set required by an expanded view of digital competence.

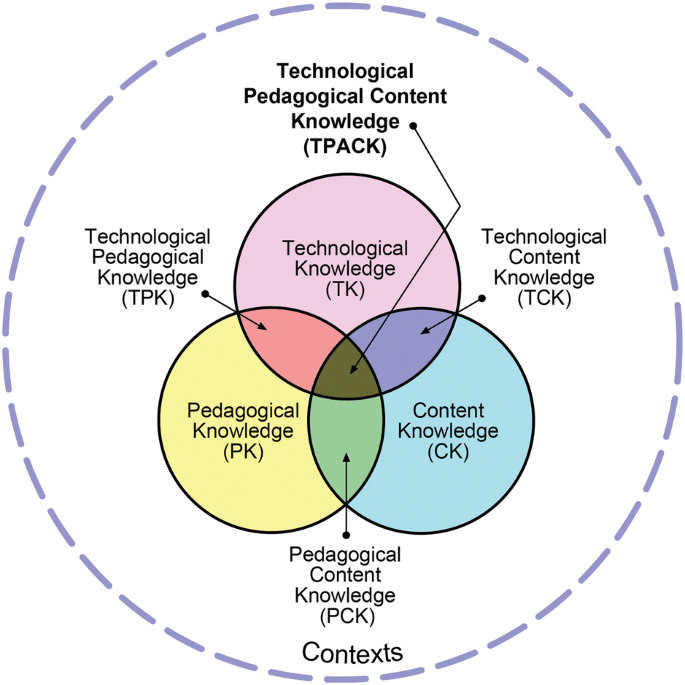

A broader and more inclusive framework that goes some way towards addressing the shortcomings of SAMR, is Mishra and Koehler’s ( 2006 ) technological pedagogical content knowledge, or TPACK model. TPACK builds on the earlier work of Shulman ( 1986 ), “to explain how teachers’ understanding of educational technologies and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) interact with one another to produce effective teaching with technology” (Koehler et al. 2013 , p. 14). Unlike SAMR, TPACK does not represent a hierarchy or staged progression, but rather presents a holistic model that theorises the relationship between, and contribution of, technological, pedagogical and content knowledge to effective curriculum learning-focused technology use. TPACK merges each element into a central core that blends deep and robust discipline conceptual knowledge (CK) with an understanding of the potential of, and capacity to use technology (TCK) to enhance learning, through supportive pedagogies (TPK) that acknowledge students’ prior understandings and learning needs (Fig. 2 ).

The TPACK framework (from Mishra and Koehler 2006 )

The success of TPACK relies on the capabilities of teachers within each domain, and their capacity for flexibility, willingness to update, and readiness to explore how the domains interrelate to support effective technology use in a range of different situations (Harris et al. 2009 ). While TPACK acknowledges the integrative relationship between conceptual content knowledge and pedagogy and technology, within teacher education programmes this relationship is seldom reflected in course design and teaching practices (Ndongfack 2015 ). According to Ndongfack, fundamental structural issues exist in many teacher education programmes that work against building integrative TPACK knowledge. These include a tendency to, “focus on developing knowledge of pedagogy and content separately… and empowering them (students) with some basic computer skills, not how to integrate them into the teaching and learning process” (Ndongfack 2015 , p. 1707). This separation is also noted in some frameworks that list capabilities separately, rather than indicating how they work together in more effective, integrative approaches (e.g., ISTE 2017 ; UNESCO 2011 ). Despite the emergence of a few studies signalling discipline-related learning benefits from redeveloping courses using an integrative TPACK approach (e.g., Habowski and Mouza 2014 ), such innovations are presently not commonplace in teacher education programmes.

Although offering a more comprehensive framework that acknowledges the complexities of optimising digital technology’s contribution in the classroom, TPACK maintains the focus of other frameworks firmly on subject learning-related outcomes. That is, it theorises the relationship between, and blending of pedagogical, content and technological knowledge to enhance the learning performance of students in, and sometimes across, subject disciplines. While valuable for this purpose, TPACK in its original form is limited in its usefulness for building a broader-based conceptualisation of teacher digital competence.

Since TPACK’s publication in 2006, the educational and technological landscape has altered significantly, largely in response to new digital innovations and rapidly changing and often unstable social, political and economic environments. Given these changes, it could be argued that the knowledge school students will need and that their teachers will need to teach them, to safely, sustainably and productively engage with and leverage benefits from digital resources in challenging future environments, requires more than simple ‘technical’ exposure to ICT in traditional school subjects. Concerns that were not apparent even 10 years ago, have emerged as major players in our understanding of what it now means to be ‘digitally competent’. These include considerations such as cybersafety and managing personal data and online presence, digital citizenship, ethics and judgement, and building knowledge from, and collaborating in, online networks and virtual environments. A more holistic conceptual framework is needed that takes account of such factors, and teacher educators must widen their focus to ensure their students understand and are equipped to teach these, when they begin their careers.

Understanding digital competence

Janssen et al.’s ( 2013 ) Delphi study provides insights into what a more holistic digital competence framework might look like. Their survey of 95 experts comprising representatives from academic, education and training, government and policy and IT business sectors, revealed twelve elements considered essential to broadly-based digital competence. These are summarised in Table 1 .

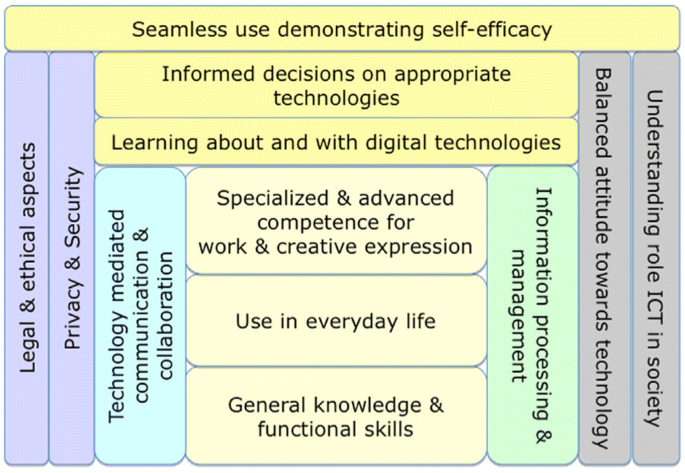

Janssen et al. ( 2013 ) conceptualised each element as a ‘building block’ in establishing holistic digital competence. They organised these into a model that displayed how the elements worked together, resulting in, “seamless use demonstrating self-efficacy” (p. 478) (Fig. 3 ). Central to the model are ‘core’ competencies that include functional, integrative and specialised uses of digital technology, that are enhanced by improved capabilities in networking (technology-mediated communication and collaboration) and information management (accessing and using digital information). Running parallel to these are what they term ‘supportive’ competencies. These are indicated in Fig. 3 by the purple and grey vertical pillars. They represent competencies including understanding legal and ethical considerations, personal and societal impacts and effects, and dispositional elements such as maintaining a balanced and objective attitude towards technology innovation, and a willingness to explore the potential of emerging technologies for personal and professional benefit. As competence develops, personal reflection and increased levels of integration into all aspects of daily activity contribute to greater awareness of how appropriate digital technology use can be leveraged across the lifespan, leading to seamless personal and professionally-beneficial selection and use.

Janssen et al.’s ( 2013 ) elements of digital competence model

In their discussion of the model, Janssen et al. ( 2013 ) signal limitations to its direct application to specific contexts. They point to the balance that needs to be struck between choosing, “a common denominator that is broad enough to encompass nearly everything, (thereby) being over-inclusive or too vague, or a narrower common denominator (with the risk of) the conception being too restrictive” (p. 480). They further comment that, “digital competence should be understood as a pluralistic concept” (p. 480), emphasising that consideration must be given to the unique but interrelated and connected purposes and functions of digital technology, in different contexts. Janssen et al. ( 2013 ) highlight that the way in which digital competence is developed and displayed in one context will differ from others, and that it is important to view digital competence, “from a plurality of angles” (p. 480).

In relation to teacher education, Lund et al. ( 2014 ) comment on the unique challenges faced by teacher educators in developing a holistic view of digital competence in their students. They point out that teacher educators are required both to educate their students about using present and emerging digital resources in their own professional practice, but also about how to make their students, “capable of using technology in productive ways” (p. 286). Achieving this is particularly difficult, as it requires catering for more than the immediate capability needs of students, to build a transformative competence , that will enable them to interpret into specific instructive, learning design, classroom organisation and assessment practices, how to best use digital resources to support their own students’ learning (Lund et al. 2014 ).

Other studies highlight the need for teacher educators and their students to consider digital technologies as culturally-embedded artefacts, understanding how they shape and influence our knowledge construction, social interactions and development as people (e.g., Ludvigsen and Mørch 2010 ; Säljö 2010 ). Säljö ( 2010 ) suggests that in assessing the impact of digital technology on learning, we need to broaden our perspective to consider not only knowledge outcomes, but also how these outcomes were arrived at, through using digital artefacts. He terms this “performative action” (Säljö 2010 , p. 60), arguing that it is the basis for transforming our understanding of what learning is, what we should expect people to learn, and how this learning can occur. Building on Säljö’s work, Lund et al. ( 2014 ) argues the importance of performative competence in supporting teacher education students to identify transformative uses for technology in teaching. Noting their unique position as newcomers to school environments, Lund et al. suggest performative competence will enable beginning teachers to resist, “merely being socialised into existing practices, but being able to contribute to the development of new ones” ( 2014 , p. 287). While acknowledging difficulties achieving this in practice, Lund et al. view performative competence as essential to a broad understanding of teacher digital competence in a knowledge-based society.

The contested nature of teacher digital competence

To this point, reviewed literature has presented different perspectives on building teacher education students’ digital capability. Models such as TPACK and SAMR represent pragmatic approaches, suggesting capability comprises the capacity to effectively combine technological, pedagogical and content-knowledge to use digital resources to enhance subject knowledge outcomes. Other discussion signals a broader interpretation, including elements such as personal ‘digital dispositions’ and behaviours, and consideration of the impacts of digital technologies on people, society and environment (e.g., Janssen et al. 2013 ). Some suggest incompatibility exists between these two interpretations, “with tensions between understandings as a skill set and technical competence, and those that focus on socio-cultural and communicative practices” (Gruszczynska and Pountney 2013 , p. 29); while others point to their compatibility and complementary nature (e.g., Ottestad et al. 2014 ; Põldoja et al. 2011 ).

Official documents and frameworks tend to emphasise ICT skills or ‘information literacy’ perspectives, prioritising the acquisition of technical and procedural skills that can be planned for and assessed against professional standards (e.g., Australia’s National Professional Standards for Teachers; ISTE Standards for Educators; UNESCO ICT Competency Standards for Teachers). On the other hand, researchers and academics are calling for a broadening of the emphasis to encompass personal and socio-cultural factors, such as managing one’s personal information and online profile, safety and security, and exercising digital judgement (e.g., Foulger et al. 2017 ; Salas-Pilco 2013 ). From a policy standpoint, the reductive approach of standards frameworks holds considerable appeal, due to the relative simplicity of assessing capabilities through testing or checklist-like recording. However, developing and assessing non-technical personal competencies is far more difficult although arguably just as important, given the need to educate students about dangers such as cyberbullying and online predatory behaviours through social media, identity theft, and the misuse of digitally-harvested personal information (Palermiti et al. 2017 ; Richards et al. 2015 ).

It is apparent considerable debate exists in literature concerning the exact definition and nature of teacher digital ‘competence’, and how this can be best developed during initial teacher education. While prevailing framework emphases based on digital literacy notions of technical, pedagogical and content knowledge go some way towards informing the capabilities required by graduating teachers, it is argued that these are insufficient in present and future educational environments. School students need to know more than procedural and technical skills and benefit from digital technology’s use in curriculum subject learning. It could reasonably be expected that teacher education students should strive to extend their competence beyond didactic application of digital technologies, towards a more holistic view encompassing personal and societal considerations, such as those introduced earlier. While this is a challenging undertaking it is a vitally important one, if the students they teach are to be better-prepared to function productively and safely in increasingly digitally-mediated personal and professional environments.

Conceptual frameworks and digital competence

Antonenko ( 2014 ) describes conceptual frameworks as, “practical tools—a process and a product for organising and aligning all aspects of an inquiry” (p. 55). According to Antoneko, conceptual frameworks can take different forms for different purposes, but generally communicate, “the system of beliefs, assumptions, theories and concepts that support and inform (inquiry)” ( 2014 , p. 55). Ravitch and Riggan ( 2012 ) suggest conceptual frameworks define the ‘big ideas’ associated with a particular inquiry, and comprise a blend of personal beliefs, assumptions and experiential knowledge; topical research (knowledge relevant to the field of study), and theories generated from prior empirical work. While conceptual frameworks are important for defining the key ideas, relevance, rationale and foci for an inquiry or programme, they are not intended to act as a ‘formula’ or ‘prescription’ detailing, in this case, universally-applicable curricula with the goal of improving students’ digital capabilities. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to guide and inform curriculum and programme design and content which is tailored by expert professionals to the context in which it is to function, not specify precisely what it should comprise or how it should be delivered. The next section introduces a teacher digital competence (TDC) conceptual framework that builds on Janssen et al.’s ( 2013 ) work. It positions Janssen et al.’s general competencies within the context of teacher education, extending it by introducing ‘teaching specific’ competencies aligned with TPACK, and integrated, personal/ethical and personal/professional competencies.

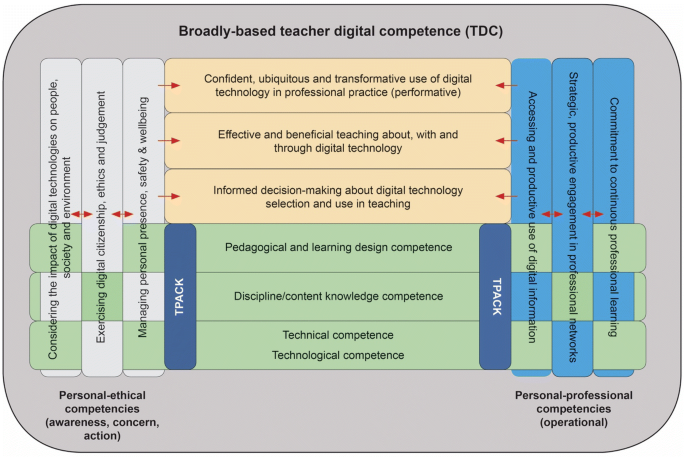

The teacher digital competence (TDC) framework

As signalled by Lund et al. ( 2014 ), the transformative potential of teachers new to the classroom offering contemporary ideas and perspectives, needs to be realised before they become enculturated or socialised into existing school norms and practices. By encouraging them to consider an expanded view of teacher digital competence, that includes but moves beyond the present focus on didactic application and technically-oriented digital literacy-building before entering the classroom, there exists the possibility that they challenge existing thinking, possibly becoming ‘change agents’ towards a more inclusive and contemporary understanding of teacher digital competence. At a practical level, such understandings will also support them in their efforts to plan and structure learning programmes to foster relevant competencies in their own students. The following section introduces elements of a comprehensive framework that depicts the integration of curriculum-related and personal-ethical and personal-professional competencies, argued above as essential for establishing the broad capability set required of teachers currently entering the profession, and in the future.

Understanding the framework

The TDC framework (Fig. 4 ) represents diagrammatically a broadly-based conceptualisation of teacher digital competence. While the framework could equally be used to inform the competency set of practicing teachers, the discussion that follows and suggestions for use, specifically focus on its applicability to teacher education.

Curriculum competencies

The TDC framework extends TPACK-aligned competencies that specifically focus on the skills and capabilities needed to integrate digital resources to support subject learning. The green horizontal bars depict the main elements of TPACK, with the vertical, dark blue side pillars indicating their integrated nature in forming the capabilities and skills needed to use digital technologies for subject-based learning. Technical competence refers to robust knowledge of the ‘mechanics’ of operating various digital technologies, such as mobile devices, apps, network services and so on. Technological competence focuses more on theoretical understandings related to the role and potential of digital technologies in teaching and learning, and knowledge of the rationale underpinning its inclusion in educational environments. In short, this competence emphasises understanding the hows (technical) and whys (technological) of digital technology in the classroom.

Discipline and content knowledge competence aligns closely with Mishra and Koehler’s ( 2006 ) definition, that is, knowledge of, “the actual subject matter to be learned and taught” (p. 1025). Although possibly self-evident, teacher education students need sound conceptual knowledge of subject content in order to teach it, with or without the assistance of technology. Put simply, they must ‘know their stuff’. The third bar, pedagogical and learning design competence, refers to the need for robust knowledge of how to plan and teach with , through and about digital technologies. Pedagogy has been described as, “the science and art of teaching” (Battro et al. 2013 , p. 177), suggesting a blending of technical and organisational capabilities with personal teaching creativity, flair and style. Competence in this element requires students to know how to best teach with, about and through digital technologies, focusing on effective and engaging teaching performance, strategies, resource, class management and organisational approaches, and appropriate learning designs. These might include knowledge of effective class group and resource access systems, critical review and selection of different technologies and applications as being ‘fit for purpose’, the compatibility of digital resources with subject and problem, project and inquiry-based learning designs, and so on. The three core competencies integrate to establish a solid foundation upon which teacher education students are able to make informed and beneficial decisions about digital resource use, improve their teaching effectiveness with them, and develop confident and seamless digitally-enhanced teaching practice (the yellow bars).

Personal-ethical competencies

Flanking the core competencies, the framework introduces two new sets of integrated competencies : personal-ethical and personal-professional. Personal-ethical competencies require teacher education students to understand, model and where relevant, include specific teaching content, to assist their students to access and use digital resources in a sustainable, safe and ethical way. Broadly, the first two pillars target what it means to be a good ‘digital citizen’, and aim to build knowledge of how to maintain personal safety and data security in a range of digitally-mediated environments (e.g., social networks), and ensure health and wellbeing while using devices. These respond to issues such as the increasing instances of identity theft, predatory online behaviours, cyberbullying, and harvesting and misuse of personal information; and also physical and psychological problems that have been associated with device overreliance and use, such as obesity, internet and game addiction, and social isolation. In practical terms, these two pillars serve the dual function of educating about the implications and effects of digital transactions and interactions on others, and also teaching students specific mitigation strategies, should they fall victim to negative digitally-mediated behaviours. The third pillar considers the impacts of digital technologies on people, society and environment. This has been included responding to increasing global concerns such as multinational company exploitation of workers in device production factories and at raw material source sites, the dumping of discarded devices in toxic waste pits in developing countries, and the intrusive effects digital devices can have on maintaining a sustainable and healthy work/life balance. The pillar encourages students to take a critical perspective on digital technologies, questioning who the winners and losers are from technological innovation, and adopting a proactive personal stance on societal issues related to the effects of technologies.

It should be noted that the order of the pillars does not represent their level of importance, and the red double-headed arrows indicate their interrelated nature. For example, it could be argued that the centre pillar, exercising ethical digital citizenship and judgement, broadly encompasses competencies included in the other two. While acknowledging this may be the case, to enhance the framework’s usefulness as a practical tool for informing teacher educators’ planning and practice, they have been detailed separately.

Personal-professional competencies

On the right flank of the core competencies, the lighter blue pillars depict three, integrated personal-professional competencies. The first of these encompasses capabilities aligned with earlier conceptualisations of information literacy. This includes skills such as recognising the need for information, sourcing relevant information using effective search strategies (digital and non-digital forms), evaluating and organising information, integrating information for practical application, and critical thinking and problem solving (Webber and Johnston 2000 ). This pillar effectively represents an operational competence, that will support students across all activities associated with the use of digital resources for information access, exchange and application.

The second pillar, strategic, productive engagement in professional networks, reflects the importance of understanding how best to leverage personal and professional benefit from strategic participation in an ever-expanding array of online networks and collaborative environments. However, competence in this element must focus on strategic engagement —that is, selection and collaborative participation likely to lead to professional benefit for the individual, and the online community as a whole. The web is abundant with teaching-related networks and communities, notwithstanding more generic professional networks such as LinkedIn or Xing. It is simply not possible, nor desirable, to engage in them all. Teacher education students must understand the importance of strategic engagement to ensure time and effort spent professional networking is beneficial and productive.