- How it works

Use of Pronouns in Academic Writing

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 17th, 2021 , Revised On August 24, 2023

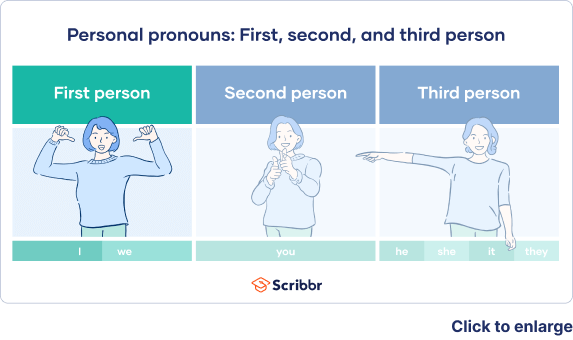

Pronouns are words that make reference to both specific and nonspecific things and people. They are used in place of nouns.

First-person pronouns (I, We) are rarely used in academic writing. They are primarily used in a reflective piece, such as a reflective essay or personal statement. You should avoid using second-person pronouns such as “you” and “yours”. The use of third-person pronouns (He, She, They) is allowed, but it is still recommended to consider gender bias when using them in academic writing.

The antecedent of a pronoun is the noun that the pronoun represents. In English, you will see the antecedent appear both before and after the pronoun, even though it is usually mentioned in the text before the pronoun. The students could not complete the work on time because they procrastinated for too long. Before he devoured a big burger, Michael looked a bit nervous.

The Antecedent of a Pronoun

Make sure the antecedent is evident and explicit whenever you use a pronoun in a sentence. You may want to replace the pronoun with the noun to eliminate any vagueness.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection were complete, it was delivered to the owner.

In the above sentence, it is unclear what the pronoun “it” is referring to.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection was complete, the car was delivered to the owner.

Use of First Person Pronouns (I, We) in Academic Writing

The use of first-person pronouns, such as “I” and “We”, is a widely debated topic in academic writing.

While some style guides, such as ‘APA” and “Harvard”, encourage first-person pronouns when describing the author’s actions, many other style guides discourage their use in academic writing to keep the attention to the information presented within rather than who describes it.

Similarly, you will find some leniency towards the use of first-person pronouns in some academic disciplines, while others strictly prohibit using them to maintain an impartial and neutral tone.

It will be fair to say that first-person pronouns are increasingly regular in many forms of academic writing. If ever in doubt whether or not you should use first-person pronouns in your essay or assignment, speak with your tutor to be entirely sure.

Avoid overusing first-person pronouns in academic papers regardless of the style guide used. It is recommended to use them only where required for improving the clarity of the text.

If you are writing about a situation involving only yourself or if you are the sole author of the paper, then use the singular pronouns (I, my). Use plural pronouns (We, They, Our) when there are coauthors to work.

| Use the first person | Examples |

|---|---|

| To signal your position on the topic or make a claim different to what the opposition says. | In this research study, I have argued that First, I have provided the essay outline We conclude that |

| To report steps, procedures, and methods undertaken. | I conducted research We performed the statistical analysis. |

| To organise and guide the reader through the text. | Our findings suggest that A is more significant than B, contrary to the claims made in the literature. However, I argue that. |

Avoiding First Person Pronouns

You can avoid first-person pronouns by employing any of the following three methods.

| Sentences including first-person pronouns | Improvement | Improved sentence |

|---|---|---|

| We conducted in-depth research. | Use the third person pronoun | The researchers conducted in-depth research. |

| I argue that the experimental results justify the hypothesis. | Change the subject | This study argues that the experimental results justify the hypothesis. |

| I performed statistical analysis of the dataset in SPSS. | Switch to passive voice | The dataset was statistically analysed in SPSS. |

There are advantages and disadvantages of each of these three strategies. For example, passive voice introduces dangling modifiers, which can make your text unclear and ambiguous. Therefore, it would be best to keep first-person pronouns in the text if you can use them.

In some forms of academic writing, such as a personal statement and reflective essay, it is completely acceptable to use first-person pronouns.

The Problem with the Editorial We

Avoid using the first person plural to refer to people in academic text, known as the “editorial we”. The use of the “editorial we” is quite common in newspapers when the author speaks on behalf of the people to express a shared experience or view.

Refrain from using broad generalizations in academic text. You have to be crystal clear and very specific about who you are making reference to. Use nouns in place of pronouns where possible.

- When we tested the data, we found that the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- When the researchers tested the data, they found the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- As we started to work on the project, we realized how complex the requirements were.

- As the students started to work on the project, they realized how complex the requirements were.

If you are talking on behalf of a specific group you belong to, then the use of “we” is acceptable.

- It is essential to be aware of our own

- It is essential for essayists to be aware of their own weaknesses.

- Essayists need to be aware of their own

Use of Second Person Pronouns (You) in Academic Writing

It is strictly prohibited to use the second-person pronoun “you” to address the audience in any form of academic writing. You can rephrase the sentence or introduce the impersonal pronoun “one” to avoid second-person pronouns in the text.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, you must avoid procrastination.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, one must avoid procrastination.

- As you can notice in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

- As shown in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

Use of Third Person Pronouns (He, She, They) in Academic Writing

Third-person pronouns in the English language are usually gendered (She/Her, He/Him). Educational institutes worldwide are increasingly advocating for gender-neutral language, so you should avoid using third-person pronouns in academic text.

In the older academic text, you will see gender-based nouns (Fishermen, Traitor) and pronouns (him, her, he, she) being commonly used. However, this style of writing is outdated and warned against in the present times.

You may also see some authors using both masculine and feminine pronouns, such as “he” or “she”, in the same text, but this generally results in unclear and inappropriate sentences.

Considering using gender-neutral pronouns, such as “they”, ‘there”, “them” for unknown people and undetermined people. The use of “they” in academic writing is highly encouraged. Many style guides, including Harvard, MLA, and APA, now endorse gender natural pronouns in academic writing.

On the other hand, you can also choose to avoid using pronouns altogether by either revising the sentence structure or pluralizing the sentence’s subject.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, he can take a specific position on the topic.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, they can take a specific position on the topic.

- When students are asked to write an essay, they are expected to take a specific position on the topic.

- Students are expected to take a specific position on the essay topic.

- The writer submitted his work for approval

- The writer submitted their work for approval.

- The writers submitted their work for approval.

- The writers’ work was submitted for approval.

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to with the singular “they” pronoun. You may want to rewrite the sentence or name the subject directly if the pronoun makes the sentence ambiguous.

For example, in the following example, you can see it is unclear who the plural pronoun “they” is referring to. To avoid confusion, the subject is named directly, and the context approves that “their paper” addresses the writer.

- If the writer doesn’t complete the client’s paper in time, they will be frustrated.

- The client will be frustrated if the writer doesn’t complete their paper in due time.

If you need to make reference to a specific person, it would be better to address them using self-identified pronouns. For example, in the following sentence, you can see that each person is referred to using a different possessive pronoun.

The students described their experience with different academic projects: Mike talked about his essay, James talked about their poster presentation, and Sara talked about her dissertation paper.

Ensure Consistency Throughout the Text

Avoid switching back and forth between first-person pronouns (I, We, Our) and third-person pronouns (The writers, the students) in a single piece. It is vitally important to maintain consistency throughout the text.

For example, The writers completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. We completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. The writers completed the work in due time, and the content quality is well above the standard expected.“

How to Use Demonstrative Pronouns (This, That, Those, These) in Academic Writing

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to when using demonstrative pronouns. Consider placing a descriptive word or phrase after the demonstrative pronouns to give more clarity to the sentence.

For example, The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this. The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This situation shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this issue.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 8 types of pronouns.

The 8 types of pronouns are:

- Personal: Refers to specific persons.

- Demonstrative: Points to specific things.

- Interrogative: Used for questioning.

- Possessive: Shows ownership.

- Reflexive: Reflects the subject.

- Reciprocal: Indicates mutual action.

- Relative: Introduces relative clauses.

- Indefinite: Refers vaguely or generally.

You May Also Like

Apostrophes are one of the most commonly used types of punctuation in the English language. You must follow apostrophe rules to write flawlessly.

Conjunctions is the glue that the sentence together. This article explains coordinating conjunctions, subordinating conjunctions and correlative conjunctions with examples.

A hyphen ( – ) is a punctuation mark used as a joiner. It is used to join two parts of a single word. This article teaches the use of hyphen in writing with examples.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

First-Person Pronouns

Use first-person pronouns in APA Style to describe your work as well as your personal reactions.

- If you are writing a paper by yourself, use the pronoun “I” to refer to yourself.

- If you are writing a paper with coauthors, use the pronoun “we” to refer yourself and your coauthors together.

Referring to yourself in the third person

Do not use the third person to refer to yourself. Writers are often tempted to do this as a way to sound more formal or scholarly; however, it can create ambiguity for readers about whether you or someone else performed an action.

Correct: I explored treatments for social anxiety.

Incorrect: The author explored treatments for social anxiety.

First-person pronouns are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 4.16 and the Concise Guide Section 2.16

Editorial “we”

Also avoid the editorial “we” to refer to people in general.

Incorrect: We often worry about what other people think of us.

Instead, specify the meaning of “we”—do you mean other people in general, other people of your age, other students, other psychologists, other nurses, or some other group? The previous sentence can be clarified as follows:

Correct: As young adults, we often worry about what other people think of us. I explored my own experience of social anxiety...

When you use the first person to describe your own actions, readers clearly understand when you are writing about your own work and reactions versus those of other researchers.

APA Style: Writing & Citation

- Voice and Tense

- Clarity of Language

First vs Third Person Pronouns

Editorial "we", singular "they".

- Avoiding Bias

- Periods, Commas, and Semicolons

- APA Citation Style This link opens in a new window

- Using Generative AI in Papers & Projects

APA recommends avoiding the use of the third person when referring to your self as the primary investigator or author. Use the personal pronoun I or we when referring to steps in an experiment. (see page 120, 4.16 in the APA 7th Edition Manual)

Correct: We assessed the vality of the experiment design with a literature review.

Incorrect: The authors assessed the vality of the experiment with a literature review.

Avoid the use of the editorial or universal we. The use of we can be confusing because it is not clear to the reader who you are referring to in your research. Substitute the word we with a noun, such as researchers, nurses, or students. Limit the use of the word we to refer to yourself and your coauthors. (See page 120 4.17 in the APA 7th edition manual)

Correct: Humans experience the world as a spectrum of sights, sounds, and smells.

Incorrect: We experience the world as a spectrum of sights, sounds, and smells .

The Singular "They" refers to a generic third-person singular pronoun. APA is promoting the use of the singular "they" as a way of being more inclusive and to avoid assumptions about gender. Many advocacy groups and publishers are now supporting it.

Observe the following guidelines when addressing issues surrounding third-person pronouns:

- Always use a person's self identified pronoun.

- Use "they" to refer to a person whose gender is not known.

- Do not use a combination forms, such as "(s)he" and "s/he."

- Reword a sentence to avoid using a pronoun, if the gender is not known.

- You can use the forms of THEY such as them, their, theirs, and themselves.

- << Previous: Clarity of Language

- Next: Numbers >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2024 4:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gvltec.edu/apawriting

We Vs. They: Using the First & Third Person in Research Papers

Writing in the first , second , or third person is referred to as the author’s point of view . When we write, our tendency is to personalize the text by writing in the first person . That is, we use pronouns such as “I” and “we”. This is acceptable when writing personal information, a journal, or a book. However, it is not common in academic writing.

Some writers find the use of first , second , or third person point of view a bit confusing while writing research papers. Since second person is avoided while writing in academic or scientific papers, the main confusion remains within first or third person.

In the following sections, we will discuss the usage and examples of the first , second , and third person point of view.

First Person Pronouns

The first person point of view simply means that we use the pronouns that refer to ourselves in the text. These are as follows:

Can we use I or We In the Scientific Paper?

Using these, we present the information based on what “we” found. In science and mathematics, this point of view is rarely used. It is often considered to be somewhat self-serving and arrogant . It is important to remember that when writing your research results, the focus of the communication is the research and not the persons who conducted the research. When you want to persuade the reader, it is best to avoid personal pronouns in academic writing even when it is personal opinion from the authors of the study. In addition to sounding somewhat arrogant, the strength of your findings might be underestimated.

For example:

Based on my results, I concluded that A and B did not equal to C.

In this example, the entire meaning of the research could be misconstrued. The results discussed are not those of the author ; they are generated from the experiment. To refer to the results in this context is incorrect and should be avoided. To make it more appropriate, the above sentence can be revised as follows:

Based on the results of the assay, A and B did not equal to C.

Second Person Pronouns

The second person point of view uses pronouns that refer to the reader. These are as follows:

This point of view is usually used in the context of providing instructions or advice , such as in “how to” manuals or recipe books. The reason behind using the second person is to engage the reader.

You will want to buy a turkey that is large enough to feed your extended family. Before cooking it, you must wash it first thoroughly with cold water.

Although this is a good technique for giving instructions, it is not appropriate in academic or scientific writing.

Third Person Pronouns

The third person point of view uses both proper nouns, such as a person’s name, and pronouns that refer to individuals or groups (e.g., doctors, researchers) but not directly to the reader. The ones that refer to individuals are as follows:

- Hers (possessive form)

- His (possessive form)

- Its (possessive form)

- One’s (possessive form)

The third person point of view that refers to groups include the following:

- Their (possessive form)

- Theirs (plural possessive form)

Everyone at the convention was interested in what Dr. Johnson presented. The instructors decided that the students should help pay for lab supplies. The researchers determined that there was not enough sample material to conduct the assay.

The third person point of view is generally used in scientific papers but, at times, the format can be difficult. We use indefinite pronouns to refer back to the subject but must avoid using masculine or feminine terminology. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he has enough material for his experiment. The nurse must ensure that she has a large enough blood sample for her assay.

Many authors attempt to resolve this issue by using “he or she” or “him or her,” but this gets cumbersome and too many of these can distract the reader. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he or she has enough material for his or her experiment. The nurse must ensure that he or she has a large enough blood sample for his or her assay.

These issues can easily be resolved by making the subjects plural as follows:

Researchers must ensure that they have enough material for their experiment. Nurses must ensure that they have large enough blood samples for their assay.

Exceptions to the Rules

As mentioned earlier, the third person is generally used in scientific writing, but the rules are not quite as stringent anymore. It is now acceptable to use both the first and third person pronouns in some contexts, but this is still under controversy.

In a February 2011 blog on Eloquent Science , Professor David M. Schultz presented several opinions on whether the author viewpoints differed. However, there appeared to be no consensus. Some believed that the old rules should stand to avoid subjectivity, while others believed that if the facts were valid, it didn’t matter which point of view was used.

First or Third Person: What Do The Journals Say

In general, it is acceptable in to use the first person point of view in abstracts, introductions, discussions, and conclusions, in some journals. Even then, avoid using “I” in these sections. Instead, use “we” to refer to the group of researchers that were part of the study. The third person point of view is used for writing methods and results sections. Consistency is the key and switching from one point of view to another within sections of a manuscript can be distracting and is discouraged. It is best to always check your author guidelines for that particular journal. Once that is done, make sure your manuscript is free from the above-mentioned or any other grammatical error.

You are the only researcher involved in your thesis project. You want to avoid using the first person point of view throughout, but there are no other researchers on the project so the pronoun “we” would not be appropriate. What do you do and why? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

I am writing the history of an engineering company for which I worked. How do I relate a significant incident that involved me?

Hi Roger, Thank you for your question. If you are narrating the history for the company that you worked at, you would have to refer to it from an employee’s perspective (third person). If you are writing the history as an account of your experiences with the company (including the significant incident), you could refer to yourself as ”I” or ”My.” (first person) You could go through other articles related to language and grammar on Enago Academy’s website https://enago.com/academy/ to help you with your document drafting. Did you get a chance to install our free Mobile App? https://www.enago.com/academy/mobile-app/ . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter: https://www.enago.com/academy/subscribe-now/ .

Good day , i am writing a research paper and m y setting is a company . is it ethical to put the name of the company in the research paper . i the management has allowed me to conduct my research in thir company .

thanks docarlene diaz

Generally authors do not mention the names of the organization separately within the research paper. The name of the educational institution the researcher or the PhD student is working in needs to be mentioned along with the name in the list of authors. However, if the research has been carried out in a company, it might not be mandatory to mention the name after the name in the list of authors. You can check with the author guidelines of your target journal and if needed confirm with the editor of the journal. Also check with the mangement of the company whether they want the name of the company to be mentioned in the research paper.

Finishing up my dissertation the information is clear and concise.

How to write the right first person pronoun if there is a single researcher? Thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

How to Use Pronouns Effectively While Writing Research Papers?

Usage of Pronouns in an Article

- Smooth: For the smooth flow of writing, pronouns are a necessary tool. Any article, book, or academic paper needs pronouns. If pronouns are replaced by nouns everywhere in a piece of writing, its readability would decrease, making it clumsy for the reader. However, the correct usage of pronouns is also required for the proper understanding of a subject.

- Simple to Read: In academic writing, it is important to use the accurate pronoun with the correct noun in the correct place of the sentence. If the pronouns make an article complicated instead of simple to read, they have not been used effectively.

- Singular/Plural, Person: When the pronoun that substitutes a noun agrees with the number and person of that noun, the writing becomes more meaningful. Here, the number implies whether the noun is singular or plural, and person implies whether the noun is in the first, second, or third person.

- Gender-Specific: Gender-specific pronouns bring clarity to the writing. If it is a feminine noun, the pronoun should be ‘she’, and for a masculine noun, it should be ‘he’. If the gender is not specified, both ‘he’ and ‘she’ should be used. In the case of plural nouns, ‘they’ should be used.

- Exceptions: Terms like ‘everyone’ and ‘everybody’ seem to be plural, but they carry singular pronouns. Singular pronouns are used for terms like ‘anybody’, ‘anyone’, ‘nobody’, ‘each’, and ‘someone’. These pronouns are also needed in academic writing.

Which Pronoun Should be Used Where?

- Personal Pronoun: If the author is writing from the first-person singular or plural point of view, then pronouns like ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘mine’, ‘my’, ‘we’, ‘our’, ‘ours’, and ‘us’ can be used. Academic writing considers these as personal pronouns. They make the author’s point of view and the results of the research immodest and opinionated. These pronouns should be avoided in academic writing as they understate the research findings. Authors must remember that their research and results should the focus, not themselves.

- First Person Plural Pronoun: Though sometimes ‘I’ can be used in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections, it should be avoided. It is advisable to use ‘we’ instead.

- Second Person Pronoun: The use of pronouns such as ‘you’, ‘your’, and ‘yours’ is also not appropriate in academic writing. They can be used to give instructions. It is better to use impersonal pronouns instead.

- Gender-Neutral Pronoun: Publications and study guides demand the writing to be gender-neutral which is why, either ‘s/he’ or ‘they’ is used.

- Demonstrative Pronoun: While using demonstrative pronouns such as this, that, these, or those, it should be clear who is being referred to.

Did the blog interest you? Would you like to read more blogs on services related to Manuscript editing? Visit our website https://www.manuscriptedit.com/scholar-hangout/ for more information. You can reach us at [email protected] . We will be waiting for your email!!!!

Related Posts

Guidelines to write an effective abstract.

The abstract, which is a concise portrayal of the research work, is a decisive factor for the target journal or reader. It is not only essential to encourage people to read your paper, but also to persuade them to cite it in their research work. Thus, it is worth investing some extra time to write […]

Conference papers vs journal publications: Which is the better publication route?

In course of their research, academicians often need to interact and exchange views with their colleagues to provide a firmer ground for their inferences. Such meetings help them debate their research topic with other like-minded participants and then assimilate the information that is presented through audio-visual media to produce a more conclusive finding. Therefore, seminars […]

SEO Content Writing

Search engine optimisation or SEO content writing is not just an application to be used for the website, but it can be used for various other benefits as well. In a broad sense, SEO tools can be used in many different ways in order to promote websites, businesses, and products and services. In fact, one […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Is it recommended to use "we" in research papers?

Is it recommended to use "we" in research papers? If not, should I always use passive voice?

- writing-style

- passive-voice

- Related: Style Question: Use of “we” vs. “I” vs. passive voice in a dissertation – herisson Commented Dec 3, 2016 at 16:12

- 1 It's over a decade late, but I've seen multiple answers and comments here suggest use of subjects like "I" and "this researcher", so I feel obligated to point out that for papers going under double-blind peer review, use of such singular subjects can significantly bias the reviewer by tipping them off to the fact that there is only one author. This is effectively a form of de-anonymization, and it would make sense for some publishers to consider this a bad thing. In such a case, "we" might be preferred over "I"... but you should definitely check with the publisher to be sure. – Alexander Guyer Commented Feb 15, 2022 at 5:57

3 Answers 3

We is used in papers with multiple authors. Even in papers having only one author/researcher, we is used to draw the reader into the discussion at hand. Moreover, there are several ways to avoid using the passive voice in the absence of we . On the one hand, there are many instances where the passive voice cannot be avoided, while, on the other, we can also be overused to the point of irritation. Variety is indeed the spice of a well written scientific paper, but the bottom line is to convey the information as succinctly as possible.

- 1 Thanks, Jimi. So you suggest that using "we" not a really bad thing as long as not overusing it, right? – evergreen Commented Mar 2, 2011 at 23:46

- @evergreen: Definitely. Take a look at the best papers out there; we is used liberally. It really cannot be avoided, especially in experimental research writing. – Jimi Oke Commented Mar 2, 2011 at 23:48

- 5 Since this is an English site, I feel obliged to point out that “at the end of the day” and “the bottom line is” are almost synonym, and anyway close enough in meaning to clash horribly when put next to each other. Furthermore, you simply can’t follow “the bottom line is” with “on the other hand”. That contradicts the whole meaning of “bottom line”. – Konrad Rudolph Commented Mar 3, 2011 at 8:34

- @Konrad: Great points you make here. I don't necessarily agree with your final sentences, but I guess I went for too much color, resulting in an overkill of idiomatic phrases. But this is not a well-written scientific paper :) And I guess it also shows that too much spice is usually not a good thing! – Jimi Oke Commented Mar 4, 2011 at 1:13

- There is alleged to be a research paper, by a single author, who wrote: "We with to thank our wife for her understanding..." – GEdgar Commented Nov 14, 2011 at 15:22

APA (The American Psychology Association) has the following to say about the use of "we" (p. 69-70).

To avoid ambiguity, use a personal pronoun rather than the third person when describing steps taken in your experiment. Correct: "We reviewed the literature." Incorrect: "The authors reviewed the literature." [...] For clarity, restrict your use of "we" to refer only to yourself and your coauthors (use "I" if you are the sole author of the paper). Broader uses of "we" may leave your readers wondering to whom you are referring; instead, substitute an appropriate noun or clarity your usage: Correct: "Researchers usually classify birdsong on the basis of frequency and temporal structure of the elements. Incorrect: "We usually classify birdsong on the basis of frequency and temporal structure of the elements" Some alternatives to "we" to consider are "people", "humans", "researchers", "psychologists", "nurses", and so on. "We" is an appropriate and useful referent: Correct: "As behaviorists, we tend to dispute... Incorrect: "We tend to dispute..."

It's definitely OK to use "we" in research papers. I edit them professionally and see it used frequently.

However, many papers with multiple authors use such constructions as "the investigators," or "the researchers." In practice, there really aren't that many occasions when the authors of a scientific paper need to refer to themselves as agents. It happens, sure. But not that often.

Rather, the Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusion sections should speak for themselves. Any reference to the authors should be minimal as except in rare cases they are not germane to the findings.

- 1 “It’s definitely OK” … well, if it’s merely OK, then what are the alternatives? Using the passive voice extensively sounds stilted and sometimes a pronoun simply cannot be involved. So is “I” OK when writing as a single author? In my experience, this is a complete no-go for various reasons. – Konrad Rudolph Commented Mar 3, 2011 at 8:37

- 5 As noted above, instead of "I," constructions such as "this researcher" are normal. "We" is a pronoun used when one author is writing on behalf of a team or group, but usually "the researchers" or the passive voice is used. It also depends on both the field and the journal in question. – The Raven Commented Mar 3, 2011 at 12:19

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged pronouns writing-style passive-voice or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Site maintenance - Tuesday, July 23rd 2024, 8 PM - Midnight ET (3 AM - 7 AM...

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

- Upcoming initiatives on Stack Overflow and across the Stack Exchange network...

Hot Network Questions

- Limited list of words for a text or glyph-based messaging system

- Does a Fixed Sequence of Moves Solve Any Rubik's Cube Configuration When Repeated Enough Times?

- One hat's number is the sum of the other 2. How did A figure out his hat number?

- When I use rigid body collision, if the volume is too large, it will cause decoupling

- How deep should I check references of a papers I am going to cite?

- Is there any way for a character to identify another character's class?

- Probability for a random variable to exceed its expectation

- Variety without a compactification whose complement is smooth

- Can epic magic escape the Demiplane of Dread?

- How to simulate interaction between categorical and continuous variables over a binary outcome?

- Applying a voltage by DAC to a Feedback pin of a DC-DC controller

- How do people print text on GUI on Win3.1/95/98/... before Win2000?

- Data type implementation of 1.58 bits

- Is "avoid extra null pointer risk" a reason to avoid "introduce parameter objects"?

- How to properly align a scope and a node?

- Bosch 625Wh: How to Charge Spare Battery At Home?

- What is ground in a physical circuit?

- Why are the categories of category theory called "category"?

- How do you cite an entire magazine/periodical?

- Which word can be used to describe either the beat or the subdivision?

- Why does my GOV.UK IHS Surcharge keep Declining

- Why is my Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) score higher than my Speed Index (SI) score?

- How to disconnect the supply line from these older bathroom faucets?

- Why does the 75 move rule apply when the game have a forced checkmate?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Nouns and pronouns

- First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation

First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation

Published on October 17, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 4, 2023.

First-person pronouns are words such as “I” and “us” that refer either to the person who said or wrote them (singular), or to a group including the speaker or writer (plural). Like second- and third-person pronouns , they are a type of personal pronoun .

They’re used without any issue in everyday speech and writing, but there’s an ongoing debate about whether they should be used in academic writing .

There are four types of first-person pronouns—subject, object, possessive, and reflexive—each of which has a singular and a plural form. They’re shown in the table below and explained in more detail in the following sections.

| I | me | mine | myself | |

| we | us | ours | ourselves |

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

First-person subject pronouns (“i” and “we”), first-person object pronouns (“me” and “us”), first-person possessive pronouns (“mine” and “ours”), first-person reflexive pronouns (“myself” and “ourselves”), first-person pronouns in academic writing, other interesting language articles, frequently asked questions.

Used as the subject of a verb , the first-person subject pronoun takes the form I (singular) or we (plural). Note that unlike all other pronouns, “I” is invariably capitalized .

A subject is the person or thing that performs the action described by the verb. In most sentences, it appears at the start or after an introductory phrase, just before the verb it is the subject of.

To be honest, we haven’t made much progress.

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

Used as the object of a verb or preposition , the first-person object pronoun takes the form me (singular) or us (plural). Objects can be direct or indirect, but the object pronoun should be used in both cases.

- A direct object is the person or thing that is acted upon (e.g., “she threatened us ”).

- An indirect object is the person or thing that benefits from that action (e.g., “Jane gave me a gift”).

- An object pronoun should also be used after a preposition (e.g., “come with me ”).

It makes no difference to me .

Will they tell us where to go?

First-person possessive pronouns are used to represent something that belongs to you. They are mine (singular) and ours (plural).

They are closely related to the first-person possessive determiners my (singular) and our (plural). The difference is that determiners must modify a noun (e.g., “ my book”), while pronouns stand on their own (e.g., “that one is mine ”).

It was a close game, but in the end, victory was ours .

A reflexive pronoun is used instead of an object pronoun when the object of the sentence is the same as the subject. The first-person reflexive pronouns are myself (singular) and ourselves (plural). They occur with reflexive verbs, which describe someone acting upon themselves (e.g., “I wash myself ”).

The same words can also be used as intensive pronouns , in which case they place greater emphasis on the person carrying out the action (e.g., “I’ll do it myself ”).

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

While first-person pronouns are used without any problem in most contexts, there’s an ongoing debate about their use in academic writing . They have traditionally been avoided in many academic disciplines for two main reasons:

- To maintain an objective tone

- To keep the focus on the material and not the author

However, the first person is increasingly standard in many types of academic writing. Some style guides, such as APA , require the use of first-person pronouns (and determiners) when referring to your own actions and opinions. The tendency varies based on your field of study:

- The natural sciences and other STEM fields (e.g., medicine, biology, engineering) tend to avoid first-person pronouns, although they accept them more than they used to.

- The social sciences and humanities fields (e.g., sociology, philosophy, literary studies) tend to allow first-person pronouns.

Avoiding first-person pronouns

If you do need to avoid using first-person pronouns (and determiners ) in your writing, there are three main techniques for doing so.

| First-person sentence | Technique | Revised sentence |

|---|---|---|

| We 12 participants. | Use the third person | The researchers interviewed 12 participants. |

| I argue that the theory needs to be refined further. | Use a different subject | This paper argues that the theory needs to be refined further. |

| I checked the dataset for and . | Use the | The dataset was checked for missing data and outliers. |

Each technique has different advantages and disadvantages. For example, the passive voice can sometimes result in dangling modifiers that make your text less clear. If you are allowed to use first-person pronouns, retaining them is the best choice.

Using first-person pronouns appropriately

If you’re allowed to use the first person, you still shouldn’t overuse it. First-person pronouns (and determiners ) are used for specific purposes in academic writing.

| Use the first person … | Examples |

|---|---|

| To organize the text and guide the reader through your argument | argue that … outline the development of … conclude that … |

| To report methods, procedures, and steps undertaken | analyzed … interviewed … |

| To signal your position in a debate or contrast your claims with another source | findings suggest that … contend that … |

Avoid arbitrarily inserting your own thoughts and feelings in a way that seems overly subjective and adds nothing to your argument:

- In my opinion, …

- I think that …

- I dislike …

Pronoun consistency

Whether you may or may not refer to yourself in the first person, it’s important to maintain a consistent point of view throughout your text. Don’t shift between the first person (“I,” “we”) and the third person (“the author,” “the researchers”) within your text.

- The researchers interviewed 12 participants, and our results show that all were in agreement.

- We interviewed 12 participants, and our results show that all were in agreement.

- The researchers interviewed 12 participants, and the results show that all were in agreement.

The editorial “we”

Regardless of whether you’re allowed to use the first person in your writing, you should avoid the editorial “we.” This is the use of plural first-person pronouns (or determiners) such as “we” to make a generalization about people. This usage is regarded as overly vague and informal.

Broad generalizations should be avoided, and any generalizations you do need to make should be expressed in a different way, usually with third-person plural pronouns (or occasionally the impersonal pronoun “one”). You also shouldn’t use the second-person pronoun “you” for generalizations.

- When we are given more freedom, we can work more effectively.

- When employees are given more freedom, they can work more effectively.

- As we age, we tend to become less concerned with others’ opinions of us .

- As people age, they tend to become less concerned with others’ opinions of them .

If you want to know more about nouns , pronouns , verbs , and other parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other language articles with explanations and examples.

Nouns & pronouns

- Common nouns

- Collective nouns

- Personal pronouns

- Proper nouns

- Second-person pronouns

- Verb tenses

- Phrasal verbs

- Types of verbs

- Active vs passive voice

- Subject-verb agreement

- Interjections

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

Yes, the personal pronoun we and the related pronouns us , ours , and ourselves are all first-person. These are the first-person plural pronouns (and our is the first-person plural possessive determiner ).

If you’ve been told not to refer to yourself in the first person in your academic writing , this means you should also avoid the first-person plural terms above . Switching from “I” to “we” is not a way of avoiding the first person, and it’s illogical if you’re writing alone.

If you need to avoid first-person pronouns , you can instead use the passive voice or refer to yourself in the third person as “the author” or “the researcher.”

Personal pronouns are words like “he,” “me,” and “yourselves” that refer to the person you’re addressing, to other people or things, or to yourself. Like other pronouns, they usually stand in for previously mentioned nouns (antecedents).

They are called “personal” not because they always refer to people (e.g., “it” doesn’t) but because they indicate grammatical person ( first , second , or third person). Personal pronouns also change their forms based on number, gender, and grammatical role in a sentence.

In grammar, person is how we distinguish between the speaker or writer (first person), the person being addressed (second person), and any other people, objects, ideas, etc. referred to (third person).

Person is expressed through the different personal pronouns , such as “I” ( first-person pronoun ), “you” ( second-person pronoun ), and “they” (third-person pronoun). It also affects how verbs are conjugated, due to subject-verb agreement (e.g., “I am” vs. “you are”).

In fiction, a first-person narrative is one written directly from the perspective of the protagonist . A third-person narrative describes the protagonist from the perspective of a separate narrator. A second-person narrative (very rare) addresses the reader as if they were the protagonist.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 04). First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation. Scribbr. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/first-person-pronouns/

Aarts, B. (2011). Oxford modern English grammar . Oxford University Press.

Butterfield, J. (Ed.). (2015). Fowler’s dictionary of modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2016). Garner’s modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a pronoun | definition, types & examples, active vs. passive constructions | when to use the passive voice, second-person pronouns | list, examples & explanation, what is your plagiarism score.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Choice of personal pronoun in single-author papers

Which personal pronoun is appropriate in single-author papers - 'I' or 'we'? Could the use of 'I' be considered egotistical? Or will the use of 'we' be considered to be grammatically incorrect?

- publications

- writing-style

- see also hsm.stackexchange.com/questions/2002/… – GEdgar Commented Apr 30, 2016 at 21:15

- 1 Your question is similar to academia.stackexchange.com/questions/11659/… – Richard Erickson Commented Dec 14, 2017 at 17:04

- 15 Easy solution: get a co-author. It wouldn't be the first time – Davidmh Commented Dec 14, 2017 at 17:22

7 Answers 7

Very rarely is 'I' used in scholarly writing (at least in math and the sciences). A much more common choice is 'we', as in "the author and the reader". For example: "We examine the case when..."

One exception to this rule is if you're writing a memoir or some other sort of "personal piece" for which the identity of the author is particularly relevant.

Now let me quote Paul Halmos (Section 12 of "How to Write Mathematics"):

One aspect of expository style that frequently bothers beginning authors is the use of the editorial "we", as opposed to the singular "I", or the neutral "one". It is in matters like this that common sense is most important. For what it's worth, I present here my recommendation. Since the best expository style is the least obtrusive one, I tend nowadays to prefer the neutral approach. That does not mean using "one" often, or ever; sentences like "one has thus proved that..." are awful. It does mean the complete avoidance of the first person pronouns in either singular or plural. "Since p , it follows that q ." "This implies p ." "An application of p to q yields r ." Most (all ?) mathematical writing is (should be ?) factual; simple declarative statements are the best for communicating facts. A frequently effective time-saving device is the use of the imperative. "To find p , multiply q by r ." "Given p , put q equal to r ."... There is nothing wrong with the editorial "we", but if you like it, do not misuse it. Let "we" mean "the author and the reader" (or "the lecturer and the audience"). Thus, it is fine to say "Using Lemma 2 we can generalize Theorem 1", or "Lemma 3 gives us a technique for proving Theorem 4". It is not good to say "Our work on this result was done in 1969" (unless the voice is that of two authors, or more, speaking in unison), and "We thank our wife for her help with the typing" is always bad. The use of "I", and especially its overuse, sometimes has a repellent effect, as arrogance or ex-cathedra preaching, and, for that reason, I like to avoid it whenever possible. In short notes, obviously in personal historical remarks, and perhaps, in essays such as this, it has its place.

You can download the pdf of Halmos' complete essay .

- 6 +1 for the Halmos quote. Your example ("we let...") is certainly a place where I wouldn't use a pronoun at all! – David Ketcheson Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 6:04

- 2 @scaaahu Without reading the specific example, I can't be sure, but... I would liken "We call something X" to saying "this is how it's done" descriptive of those in the know and prescriptive for those new to the area. – Dan C Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 6:57

- 19 I can see the value of Halmos' advice in the specific field of mathematics, where the entire content of a paper is composed of incontrovertible facts. However, in the natural sciences things are rarely so clear-cut, and in the end what most papers express are not facts but opinions. These are highly informed opinions based on evidence, but they are opinions nevertheless. In my view it's counterproductive and misleading to try and avoid any mention of whose opinions they are, so I think it's very appropriate to introduce such a paper with "I argue that...". – N. Virgo Commented Aug 26, 2012 at 10:28

- 22 Additionally, outside of mathematics you have to deal with descriptions of experiments. It's a question of style whether to say "a device was constructed", "we constructed a device", "I constructed a device". Personally, I find the first incredibly awkward (constructed by whom?), the second a bit jarring (wait, was there someone else involved?) and the third perfectly fine. – N. Virgo Commented Aug 26, 2012 at 10:32

- 6 I, for one, find the idea of using 'we' in a single-author essay to be utterly bizarre. Authors should take responsibility for their own work and leave the readers out of it. – Ubiquitous Commented May 12, 2015 at 15:06

Authorial "we" is quite common, even in single author papers (at least in math and related fields). The explanation I've heard is that it should be read as both the writer and the reader (as in "we now prove...", meaning that we two shall now prove it together). Some people find it awkward, and insist on "I", but this is unusual (and I've heard of referees demanding "we"). In cases where "we" is truly nonsensical (for instance, introducing a list of people being thanked), people who avoid "I" either find an alternate phrasing or refer to themselves in the third person ("The author would like to thank...").

In single-author papers, I think consistency trumps any particular rule or style. As the Haimos essay suggests, you can achieve whatever style you choose; you just need to make sure that it makes sense.

For instance, don't switch back and forth between "I" and "we," or between active and passive constructions too close to one another. Make the use of "I" and "we" clear to indicate active participation in the project (for instance, for assumptions or approximations made, you choose that—unless it's something everybody does).

- 21 I agree with "don't switch back and forth between 'I' and 'we'", but I disagree with your comparison of that with "[don't switch back and forth between] active and passive constructions". There are contexts where habitual use of I makes sense. I know of no analogous contexts for repeated use of passive constructions . As a general rule, writing extensively in the passive voice is just bad writing . – Dan C Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 15:20

- +1, "I" or "We", it's your call, but be consistent (and also use the present tense, but this is another story). – Sylvain Peyronnet Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 17:08

- The passive voice is useful for switching the emphasis. But what I meant was don't go "We modeled X. This was done to study Y. We will not look at Z further. Z was not modeled because A." and so on. – aeismail Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 20:15

- 2 "We modeled X to study Y. We did not model Z because A." – JeffE Commented Aug 24, 2012 at 12:53

- 7 @aeismail: I honestly can't find anything objectionable in your proposed counterexample! – Aant Commented Aug 26, 2012 at 23:49

When not faced with a journal/publisher specific style, my go to style guide is APA. I really like the APA style blog. In this post they explain:

If you’re writing a paper alone, use I as your pronoun. If you have coauthors, use we.

They go on to lash out against the editorial we

However, avoid using we to refer to broader sets of people—researchers, students, psychologists, Americans, people in general, or even all of humanity—without specifying who you mean (a practice called using the editorial “we”). This can introduce ambiguity into your writing.

There is also another related post about using we and avoiding ambiguity.

- 3 The context is important, though. If you are writing a scientific/mathematical paper, writing "I" will come across as odd and unprofessional, so this would be pretty bad advice. – Rob Commented Sep 18, 2021 at 19:45

There are already two good answers for this entry, one is also accepted. But I'm going to give my two cent answer anyway...

This is what I learned from a workshop on writing scientific texts. Basically, my suggestion would be avoid using either "we" or "I" in the whole paper, except the "Experiment and results" section 1 . The idea is that by using passive form in the text, you avoid both issues related to being egotistical or ungrammatical.

Then in the "Experiment and results" you use "We" 2 . Why not using passive form in "Experiment" section? Well, you could but the idea here is that these results can be produced by everyone, including readers. So "we" is not referring to author(s), but to author(s) and readers. 1. This might not be the case in fields that papers do not have an experimental section. 2. Once could object that this will result in inconstancy in paper which is a valid objection.

- 1 Why the factually incorrect "we" in the experiments and results sections? This is nonsense. The "we" should be used iff it can refer to author and reader . – Walter Commented Jul 6, 2017 at 9:25

The " royal we " works

The " royal we " suggests a hypothetical population of peers who hold some position. This hypothetical population may-or-may-not include the reader, at the reader's option. And since it's a hypothetical population with a subjective number of members, " we " is appropriate.

Even if you're talking about a real-world action that you did to perform a specific experimental step, it's still accurate to describe the hypothetical population as having performed that action.

This approach has a few advantages:

It's easier for readers to put themselves into your shoes as a member of the population engaging in the study.

It avoids distracting the reader with inconsistent pronouns for the authors across papers.

It's field-dependent. English teachers told me the following:

In STEM you use "we" for "the reader and the author(s)", regardless of how many authors you have. (Note that the "royal we" would be the wrong term, since the authors don't wish to sound as ostentatious in "we, the king of ...".)

In languages, you use "I" if you are the sole author.

- 2 That really is bad advice. "We studied X" does not mean that the reader studied it. – aeismail Commented Jan 6, 2018 at 22:57

- 11 @aeismail That really is a bad comment. In STEM, "we studied X" in the conclusion of a paper does mean that the reader studied X while reading the paper. In languages, "we" may mean sound pompous, may or may not involve the reader, or be completely misunderstood. – user85520 Commented Jan 6, 2018 at 23:43

- 1 And what does It mean in the introduction? It shouldn’t mean one thing in the introduction and another somewhere else. – aeismail Commented Jan 7, 2018 at 1:21

- 4 Sorry, "we" does not universally mean "reader and the author." There are too many usages where that definition simply doesn't work: "We added reagent X." "We measured the growth of species Y." "We observed that Y grew with temperature." The reader did none of those. – aeismail Commented Jan 7, 2018 at 2:14

- 4 It would be more accurate to say that in mathematics (and related areas like theoretical computer science), one uses "we" for "the author and the reader(s)". There is no such area as "STEM". – JeffE Commented Jan 7, 2018 at 4:27

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged publications writing writing-style grammar ..

- Featured on Meta

- Site maintenance - Tuesday, July 23rd 2024, 8 PM - Midnight ET (3 AM - 7 AM...

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

- Upcoming initiatives on Stack Overflow and across the Stack Exchange network...

Hot Network Questions

- How to decide sizes for transistors in a design? What does it mean to design an IC?

- Looking for title about time traveler finding empty cities and dying human civilization

- Variety without a compactification whose complement is smooth

- How do you calculate the mass of diproton helium-2 nucleus?

- How many different rectangles can be formed by connecting four dots in a 4x4 square array of dots, such that the sides are parallel to the grid?

- Determining coordinates of point B and C given distance and coordinates from point A to point B and C in QGIS

- why does RaggedRight and indentfirst cause over and underfull problems?

- How can 4 chess queens attack all empty squares on a 6x6 chessboard without attacking each other?

- Is there anyway a layperson can discern what is true news vs fake news?

- User stories can be moved from BA to Development team, or a separate story has to be created for Developers and further for QA?

- If a unitary operator is close to the identity, will it leave any state it acts on unchanged?

- Probability for a random variable to exceed its expectation

- The run_duration column from the msdb.dbo.sysjobhistory returns negative values

- 具合 vs. 塩梅 for "condition/state"

- Using a dynamo hub to run ONLY rear lights

- What does "ad tempus tantum" mean?

- One hat's number is the sum of the other 2. How did A figure out his hat number?

- Applying a voltage by DAC to a Feedback pin of a DC-DC controller

- General support

- Dumb replacement for cites command

- Bosch 625Wh: How to Charge Spare Battery At Home?

- Why are the categories of category theory called "category"?

- Which word can be used to describe either the beat or the subdivision?

- How do you cite an entire magazine/periodical?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Appropriate Pronoun Usage

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Because English has no generic singular—or common-sex—pronoun, we have used HE, HIS, and HIM in such expressions as "the student needs HIS pencil." When we constantly personify "the judge," "the critic," "the executive," "the author," and so forth, as male by using the pronoun HE, we are subtly conditioning ourselves against the idea of a female judge, critic, executive, or author. There are several alternative approaches for ending the exclusion of women that results from the pervasive use of masculine pronouns.

Recast into the plural

- Original: Give each student his paper as soon as he is finished.

- Alternative: Give students their papers as soon as they are finished.

Reword to eliminate gender problems.

- Original: The average student is worried about his grade.

- Alternative: The average student is worried about grades.

Replace the masculine pronoun with ONE, YOU, or (sparingly) HE OR SHE, as appropriate.

- Original: If the student was satisfied with his performance on the pretest, he took the post-test.

- Alternative: A student who was satisfied with her or his performance on the pretest took the post-test.

Alternate male and female examples and expressions. (Be careful not to confuse the reader.)

- Original: Let each student participate. Has he had a chance to talk? Could he feel left out?

- Alternative: Let each student participate. Has she had a chance to talk? Could he feel left out?

Indefinite Pronouns

Using the masculine pronouns to refer to an indefinite pronoun ( everybody, everyone, anybody, anyone ) also has the effect of excluding women. In all but strictly formal uses, plural pronouns have become acceptable substitutes for the masculine singular.

- Original: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring his money tomorrow.

- Alternative: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring their money tomorrow.

An alternative to this is merely changing the sentence. English is very flexible, so there is little reason to "write yourself into a corner":

- Original: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring his money.

- Alternative: People who want to go to the game should bring their money.

Encyclopedia