Easy Literary Lessons

- [email protected]

Knowledge and Wisdom by Bertrand Russell | Knowledge and Wisdom | Bertrand Russell | Key Points | Summary | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lessons

- Post author: easyliterarylessons

- Post published: April 24, 2024

- Post category: Bertrand Russell / ESSAYS

- Post comments: 0 Comments

Table of Contents

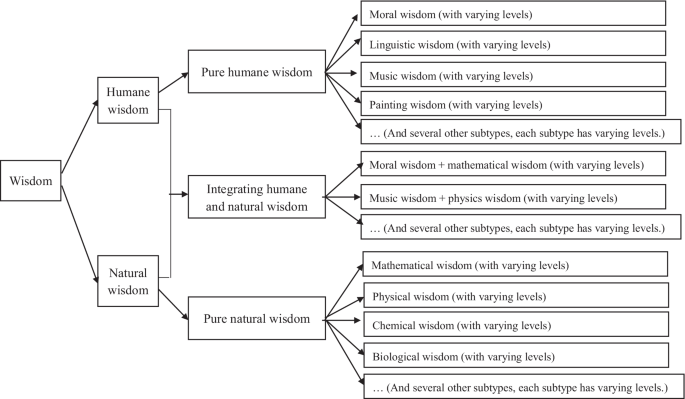

Knowledge and Wisdom

Most people would agree that, although our age far surpasses all previous ages in knowledge, there has been no correlative increase in wisdom. But agreement ceases as soon as we attempt to define `wisdom’ and consider means of promoting it. I want to ask first what wisdom is, and then what can be done to teach it. There are, I think, several factors that contribute to wisdom. Of these I should put first a sense of proportion: the capacity to take account of all the important factors in a problem and to attach to each its due weight. This has become more difficult than it used to be owing to the extent and complexity fo the specialized knowledge required of various kinds of technicians. Suppose, for example, that you are engaged in research in scientific medicine. The work is difficult and is likely to absorb the whole of your intellectual energy. You have not time to consider the effect which your discoveries or inventions may have outside the field of medicine. You succeed (let us say), as modern medicine has succeeded, in enormously lowering the infant death-rate, not only in Europe and America, but also in Asia and Africa. This has the entirely unintended result of making the food supply inadequate and lowering the standard of life in the most populous parts of the world. To take an even more spectacular example, which is in everybody’s mind at the present time: You study the composistion of the atom from a disinterested desire for knowledge, and incidentally place in the hands of powerful lunatics the means of destroying the human race. In such ways the pursuit of knowledge may becorem harmful unless it is combined with wisdom; and wisdom in the sense of comprehensive vision is not necessarily present in specialists in the pursuit of knowledge. Comprehensiveness alone, however, is not enough to constitute wisdom. There must be, also, a certain awareness of the ends of human life. This may be illustrated by the study of history. Many eminent historians have done more harm than good because they viewed facts through the distorting medium of their own passions. Hegel had a philosophy of history which did not suffer from any lack of comprehensiveness, since it started from the earliest times and continued into an indefinite future. But the chief lesson of history which he sought to unculcate was that from the year 400AD down to his own time Germany had been the most important nation and the standard-bearer of progress in the world. Perhaps one could stretch the comprehensiveness that contitutes wisdom to include not only intellect but also feeling. It is by no means uncommon to find men whose knowledge is wide but whose feelings are narrow. Such men lack what I call wisdom. It is not only in public ways, but in private life equally, that wisdom is needed. It is needed in the choice of ends to be pursued and in emancipation from personal prejudice. Even an end which it would be noble to pursue if it were attainable may be pursued unwisely if it is inherently impossible of achievement. Many men in past ages devoted their lives to a search for the philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life. No doubt, if they could have found them, they would have conferred great benefits upon mankind, but as it was their lives were wasted. To descend to less heroic matters, consider the case of two men, Mr A and Mr B, who hate each other and, through mutual hatred, bring each other to destruction. Suppose you dgo the Mr A and say, ‘Why do you hate Mr B?’ He will no doubt give you an appalling list of Mr B’s vices, partly true, partly false. And now suppose you go to Mr B. He will give you an exactly similar list of Mr A’s vices with an equal admixture of truth and falsehood. Suppose you now come back to Mr A and say, ‘You will be surprised too learn that Mr B says the same things about you as you say about him’, and you go to Mr B and make a similar speech. The first effect, no doubt, will be to increase their mutual hatred, since each will be so horrified by the other’s injustice. But perhaps, if you have sufficient patience and sufficient persuasiveness, you may succeed in convincing each that the other has only the normal share of human wickedness, and that their enmity is harmful to both. If you can do this, you will have instilled some fragment of wisdom. I think the essence of wisdom is emancipation, as fat as possible, from the tyranny of the here and now. We cannot help the egoism of our senses. Sight and sound and touch are bound up with our own bodies and cannot be impersonal. Our emotions start similarly from ourselves. An infant feels hunger or discomfort, and is unaffected except by his own physical condition. Gradually with the years, his horizon widens, and, in proportion as his thoughts and feelings become less personal and less concerned with his own physical states, he achieves growing wisdom. This is of course a matter of degree. No one can view the world with complete impartiality; and if anyone could, he would hardly be able to remain alive. But it is possible to make a continual approach towards impartiality, on the one hand, by knowing things somewhat remote in time or space, and on the other hand, by giving to such things their due weight in our feelings. It is this approach towards impartiality that constitutes growth in wisdom. Can wisdom in this sense be taught? And, if it can, should the teaching of it be one of the aims of education? I should answer both these questions in the affirmative. We are told on Sundays that we should love our neighbors as ourselves. On the other six days of the week, we are exhorted to hate. But you will remember that the precept was exemplified by saying that the Samaritan was our neighbour. We no longer have any wish to hate Samaritans and so we are apt to miss the point of the parable. If you wnat to get its point, you should substitute Communist or anti-Communist, as the case may be, for Samaritan. It might be objected that it is right to hate those who do harm. I do not think so. If you hate them, it is only too likely that you will become equally harmful; and it is very unlikely that you will induce them to abandon their evil ways. Hatred of evil is itself a kind of bondage to evil. The way out is through understanding, not through hate. I am not advocating non-resistance. But I am saying that resistance, if it is to be effective in preventing the spread of evil, should be combined with the greatest degree of understanding and the smallest degree of force that is compatible with the survival of the good things that we wish to preserve. It is commonly urged that a point of view such as I have been advocating is incompatible with vigour in action. I do not think history bears out this view. Queen Elizabeth I in England and Henry IV in France lived in a world where almost everybody was fanatical, either on the Protestant or on the Catholic side. Both remained free from the errors of their time and both, by remaining free, were beneficent and certainly not ineffective. Abraham Lincoln conducted a great war without ever departing from what I have called wisdom. I have said that in some degree wisdom can be taught. I think that this teaching should have a larger intellectual element than has been customary in what has been thought of as moral instruction. I think that the disastrous results of hatred and narrow-mindedness to those who feel them can be pointed out incidentally in the course of giving knowledge. I do not think that knowledge and morals ought to be too much separated. It is true that the kind of specialized knowledge which is required for various kinds of skill has very little to do with wisdom. But it should be supplemented in education by wider surveys calculated to put it in its place in the total of human activities. Even the best technicians should also be good citizens; and when I say ‘citizens’, I mean citizens of the world and not of this or that sect or nation. With every increase of knowledge and skill, wisdom becomes more necessary, for every such increase augments our capacity of realizing our purposes, and therefore augments our capacity for evil, if our purposes are unwise. The world needs wisdom as it has never needed it before; and if knowledge continues to increase, the world will need wisdom in the future even more than it does now.

Bertrand Russell’s reflections on knowledge and wisdom are insightful and raise important considerations about the relationship between the two. Here are some key points from the text: Knowledge vs. Wisdom: Russell begins by pointing out the apparent disconnect between the vast increase in knowledge in his time and the lack of a corresponding increase in wisdom. While knowledge involves the acquisition of information, wisdom is characterized by a sense of proportion, awareness of human ends, and the ability to make judicious choices. Comprehensive Vision: Russell emphasizes the importance of comprehensiveness in wisdom, the capacity to consider all relevant factors in a problem and assign them their due weight. Specialized knowledge, while valuable, can lead to unintended consequences if not combined with a broader understanding of its implications. Awareness of Ends: Wisdom involves an awareness of the ultimate goals of human life. Russell uses the example of historians who, driven by personal passions, may distort facts. Understanding the broader context and purpose of one’s actions is crucial in the pursuit of wisdom. Emotional Intelligence: Russell suggests that wisdom includes emotional intelligence. Men with wide knowledge but narrow feelings lack wisdom. The ability to empathize, understand others, and manage one’s emotions is essential for a wise perspective. Emancipation from the Present: Russell sees the essence of wisdom as emancipation from the tyranny of the present moment. As individuals move beyond personal concerns and develop a broader perspective, they approach impartiality and grow in wisdom. Teaching Wisdom: Russell argues that wisdom, to some extent, can be taught. He suggests that education should aim to instill wisdom by combining intellectual elements with moral instruction. The understanding of the consequences of hatred and narrow-mindedness should be integrated into knowledge dissemination. Hatred and Understanding: Russell challenges the idea that hatred of evil is productive. Instead, he advocates for understanding as a way to combat evil effectively. Resistance, in his view, should be coupled with a deep understanding and minimal force necessary to preserve the good. Compatibility of Wisdom and Vigor in Action: Contrary to the belief that wisdom may hinder vigorous action, Russell cites historical figures like Queen Elizabeth I, Henry IV, and Abraham Lincoln as examples of leaders who combined wisdom with effective action. Global Citizenship: Russell concludes by emphasizing the need for citizens, even skilled technicians, to be good citizens of the world. Wisdom becomes increasingly crucial with the growth of knowledge, as the capacity for both good and evil expands.

Author Bertrand Russell was a British philosopher, logician, essayist, and social critic. He is best known for his work in mathematical logic and analytic philosophy. His contributions to logic, epistemology, and the philosophy of mathematics established him as one of the foremost philosophers of the 20th century. In 1950, Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” Introduction In the essay “Knowledge and Wisdom,” Russell explores the relationship between knowledge and wisdom. He begins by defining knowledge as the awareness and understanding of facts, information, descriptions, or skills acquired through experience or education. On the other hand, he defines wisdom as the ability to think and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense, and insight. Russell emphasizes that while knowledge is necessary, it is not sufficient. Wisdom is needed to use knowledge in a way that promotes well-being and ethical values. Structure The essay is structured as a series of reflections and observations. Russell uses a variety of examples from history and contemporary society to illustrate his points. The essay is not divided into sections or chapters, but it follows a logical progression from the introduction of the topic to the exploration of the relationship between knowledge and wisdom, and finally to the conclusion where Russell emphasizes the importance of wisdom. Setting The setting of the essay is not a physical location but the intellectual and philosophical landscape in which Russell was writing. He discusses the role of knowledge and wisdom in society and the dangers of knowledge without wisdom. The essay reflects the intellectual climate of the early 20th century, but its themes and insights remain relevant today. Theme The main theme of the essay is the distinction between knowledge and wisdom. Russell argues that knowledge is about facts and information, while wisdom is about understanding and applying this knowledge in a meaningful and ethical way. He emphasizes that wisdom is more important than knowledge because it leads to a better understanding of the world and a more fulfilling life. Style Russell’s style in this essay is clear, concise, and thought-provoking. He uses logical arguments and real-world examples to make his points. His writing is accessible to a general audience, but also offers deep insights for those familiar with philosophical concepts. Russell’s style is characterized by clarity, precision, and a commitment to logical reasoning. Message The key message of the essay is the importance of wisdom in using knowledge. Russell warns of the dangers of knowledge without wisdom, giving examples of how knowledge can be misused when not tempered with wisdom. He advocates for the integration of wisdom into education, arguing that knowledge alone can lead to its misuse. He also discusses several factors that contribute to wisdom, including a sense of proportion, comprehensiveness with broad feeling, emancipation from personal prejudices, and the tyranny of sensory perception. The essay is a call to action for individuals and societies to value and cultivate wisdom.

Bertrand Russell

Full Name: Bertrand Arthur William Russell. Title: 3rd Earl Russell. Birth: He was born on 18 May 1872 in Trellech, Wales, United Kingdom. Death: He died on 2 February 1970 in Penrhyndeudraeth, Wales, UK. Profession: He was a British philosopher, logician, and mathematician. Work: He worked mostly in the 20th century. Nobel Prize: He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950. Contributions: He wrote many books and articles and tried to make philosophy popular1. He gave his opinion on many topics. Famous Essay: He wrote the essay, “On Denoting”, which has been described as one of the most influential essays in philosophy in the 20th Century. Political Views: He was a well-known liberal as well as a socialist and anti-war activist for most of his long life. Beliefs: In his 1949 speech, “Am I an Atheist or an Agnostic?”, Russell expressed his difficulty over whether to call himself an atheist or an agnostic.

Very Short Answer Questions

Who is the author of “Knowledge and Wisdom”? The author is Bertrand Russell. What is the main theme of the essay? The main theme is the distinction between knowledge and wisdom. What is knowledge according to Russell? Knowledge is defined as the acquisition of data and information. What is wisdom according to Russell? Wisdom is the practical application and use of knowledge to create value. How is wisdom gained? Wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization. What is the danger of knowledge without wisdom? Knowledge without wisdom can lead to misuse and harm. What are the factors that contribute to wisdom? Factors include a sense of proportion, comprehensiveness with broad feeling, emancipation from personal prejudices, and the tyranny of sensory perception. What is the message conveyed with the example of technicians? Knowledge alone cannot save the world and, in certain situations, may threaten mankind. Which leaders were able to mix knowledge and wisdom soundly? Leaders like Queen Elizabeth I of England, Henry IV of France, and Abraham Lincoln. What is the style of Russell’s writing in this essay? The style is clear, concise, and thought-provoking. What is the setting of the essay? The setting is the intellectual and philosophical landscape in which Russell was writing. What is the structure of the essay? The essay is structured as a series of reflections and observations. What is the key message of the essay? The importance of wisdom in using knowledge. What is the danger of knowledge without wisdom according to Russell? It can lead to misuse and harm. What does Russell advocate for in education? The integration of wisdom into education. What is the role of wisdom in society according to Russell? Wisdom is needed to use knowledge in a way that promotes well-being and ethical values. What is the relationship between knowledge and wisdom according to Russell? Wisdom is the practical application and use of knowledge. What is the danger of knowledge without wisdom in the context of scientific discoveries? Scientific discoveries can be misused when not tempered with wisdom. What is the role of wisdom in the use of scientific knowledge according to Russell? Wisdom is needed to use scientific knowledge in a way that promotes well-being and ethical values. What is the impact of wisdom on the quality of life according to Russell? Wisdom leads to a better understanding of the world and a more fulfilling life.

Short Answer Questions

What are the factors that contribute to wisdom according to Russell? Bertrand Russell, in his essay ‘Knowledge and Wisdom’, suggests that wisdom is influenced by several factors: A sense of proportion: This is the capacity to carefully evaluate all of the key aspects of a subject. It’s challenging due to specialization. For example, scientists develop novel drugs but may not fully understand how these medicines will affect people’s lives. Awareness of the ends of human life: This involves understanding the broader implications of actions and decisions, such as how a decrease in infant mortality due to new medicines could lead to a population increase and potential food crisis. Choice of ends to pursue: Wisdom is needed to decide our life’s objectives and to discern which goals are worth pursuing. Emancipation from personal prejudice: Wisdom helps free us from personal biases, enabling us to make more objective and fair decisions.

What message does Russell try to convey with the example of technicians? Russell uses the example of technicians to illustrate the potential harm that can result from applying technical knowledge without wisdom. He suggests that if technical knowledge is implemented without considering the broader implications, it can lead to destructive outcomes for humanity.

Which leaders does Russell say were able to mix knowledge and wisdom soundly? Russell cites Queen Elizabeth I of England, Henry IV of France, and Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, as examples of leaders who successfully combined knowledge and wisdom.

Why is wisdom needed not only in public ways, but in private life equally? Wisdom is needed in both public and private life because it helps in decision-making and overcoming personal biases. It is important in setting life goals and being able to persuade others. Without wisdom, one may not be able to make the right choices or effectively communicate their beliefs.

What is the true aim of education according to Russell? According to Russell, the true aim of education is to instill wisdom in individuals. Wisdom allows people to apply their knowledge in a way that doesn’t cause harm, and it is crucial for being a responsible and good citizen.

Can wisdom be taught? There are differing views on whether wisdom can be taught. Some sources suggest that wisdom-related skills can, to a certain extent, be taught. Teaching experiments have been made as part of university education, with successful examples of wisdom pedagogy including reading great philosophers or classic texts, discussing the texts in the classroom, and writing different kinds of reflection diaries related to one’s own beliefs and values. However, other sources suggest that wisdom cannot be taught, but only sought. It is achieved as a synthesis in reflection by individuals who are facing a practical need or a theoretical challenge of orientation.

Why does the world need more wisdom in the future? The world needs more wisdom in the future because with advancements in knowledge and technology, people may make unwise decisions and cause harm if they don’t have wisdom to guide them. Wisdom is crucial for making responsible and informed choices, and it is necessary for a brighter future.

How does Russell define wisdom? Russell defines wisdom as the ability to use knowledge, understanding, experience, common sense, and insight to make sound decisions and sensible judgments. Wisdom helps a person to overcome multiple difficult situations that he may encounter and get out of them with the least possible losses.

What is the difference between knowledge and wisdom according to Russell? According to Russell, knowledge and wisdom are different things. Knowledge is defined as the acquisition of data and information, while wisdom is defined as the practical application and use of the knowledge to create value. Wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization.

What is the role of wisdom in the use of knowledge? Wisdom plays a crucial role in the use of knowledge. It provides the necessary perspective and insight required to make good decisions. It involves using knowledge to understand the situation, consider the consequences, and weigh the options before making a decision. Wisdom is essential in applying knowledge as it provides the necessary perspective and insight required to make sound decisions and sensible judgments.

Essay Type Questions

Write the critical appreciation of the essay..

Introduction Bertrand Russell, a renowned British philosopher, logician, and Nobel laureate, explores the relationship between knowledge and wisdom in his essay “Knowledge and Wisdom”. He emphasizes the importance of wisdom and suggests that in the absence of it, knowledge can be dangerous.

Definition of Wisdom Russell defines wisdom as the ability to use knowledge, understanding, experience, common sense, and insight to make sound decisions. He describes the factors that influence wisdom, including a sense of proportion, comprehensiveness with broad feeling, emancipation from personal prejudices and the tyranny of sensory perception, impartiality, and awareness of human needs and understanding.

Wisdom vs Knowledge Russell distinguishes between knowledge and wisdom. He states that knowledge involves acquiring data, while wisdom involves practical application and value creation through learning and experience. He critiques the global explosion of knowledge but emphasizes that knowledge and wisdom are not synonymous.

The Role of Wisdom Russell argues that wisdom is needed not only in public ways but in private life equally. In deciding what goals to follow and overcoming personal prejudice, wisdom is needed. He also suggests that wisdom is gained when a person’s thoughts and feelings become less persona.

The Danger of Knowledge Without Wisdom Russell gives the example of scientists and historians to illustrate how knowledge without wisdom can be dangerous. Scientists develop novel drugs but may not fully understand how these medicines will affect people’s lives. Similarly, historians like Hegel wrote with historical knowledge and made the Germans believe they were a master race, and this false sense of pride drove them to war.

The Aim of Education Russell believes that the true aim of education is to instill wisdom in individuals. He is assured that wisdom must be an integral part of education because a person can be well educated but lack the wisdom to understand the true meaning of life. Wisdom is required in education because knowledge alone leads to its misuse.

Conclusion In conclusion, Russell’s essay “Knowledge and Wisdom” is a profound exploration of the relationship between knowledge and wisdom. It emphasizes the importance of wisdom in using knowledge responsibly and highlights the dangers of knowledge without wisdom. The essay is a call to action for individuals and society to strive for wisdom, not just knowledge.

Detailed Analysis Russell begins his essay by differentiating between knowledge and wisdom. He defines knowledge as the acquisition of data and information, whereas wisdom is the practical application and use of the knowledge to create value. He emphasizes that wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization. He then discusses the factors that contribute to wisdom. According to him, a sense of proportion, comprehensiveness with broad feeling, emancipation from personal prejudices and the tyranny of sensory perception, impartiality, and awareness of human needs and understanding are all factors that contribute to wisdom. Russell also discusses the dangers of knowledge without wisdom. He uses the example of scientists and historians to illustrate this point. Scientists develop novel drugs but have no idea how these medicines will affect people’s lives. Drugs may help lower the infant mortality rate. However, it may result in a rise in population, and the world is sure to face the consequences of the rise in population. Once, Hegel, the greatest historian, wrote with historical knowledge and made the Germans believe they were a master race, and this false sense of pride drove them to war. Russell emphasizes the importance of wisdom in both public and private life. He suggests that wisdom is needed to decide the goal of our life and to free ourselves from personal prejudices. He also suggests that wisdom emerges when we begin to value things that do not directly affect us. In the end, Russell discusses the role of education in instilling wisdom. He believes that the true aim of education is to instill wisdom in individuals. He is assured that wisdom must be an integral part of education because a person can be well educated but lack the wisdom to understand the true meaning of life. Wisdom is required in education because knowledge alone leads to its misuse. In conclusion, Russell’s essay “Knowledge and Wisdom” is a profound exploration of the relationship between knowledge and wisdom. It emphasizes the importance of wisdom in using knowledge responsibly and highlights the dangers of knowledge without wisdom. The essay is a call to action for individuals and society to strive for wisdom, not just knowledge.

Write long note on Bertrand Russell as Essayist.

Bertrand Russell, a British philosopher, logician, and social reformer, was also a prolific essayist whose works have had a profound influence on the 20th century intellectual landscape. Style and Approach Russell’s essays are characterized by a clear, logical style and a precise approach. He always argues his case in a strictly logical manner and his aim is exactitude or precision. As far as possible, he never leaves the reader in any doubt about what he has to say. He stresses the need for rationality, which he calls skepticism in all spheres of life. Each of his essays is logically well-knit and self-contained. Themes and Topics Russell’s essays cover a wide range of topics, reflecting his broad interests and deep knowledge. He wrote on philosophy, mathematics, logic, social reform, and peace advocacy. His essays often addressed contemporary social, political, and moral subjects, making them relevant and accessible to a general audience. Influence and Impact Russell’s essays have had a significant impact on various fields. His contributions to logic, epistemology, and the philosophy of mathematics established him as one of the foremost philosophers of the 20th century. However, to the general public, he was best known as a campaigner for peace and as a popular writer on social, political, and moral subjects. Recognition Russell’s work as an essayist and writer was recognized with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. This award attests to the quality of his writing and the influence of his ideas. In conclusion, Bertrand Russell’s work as an essayist is characterized by its clarity, precision, and logical rigor. His essays, which cover a wide range of topics, have had a significant impact on various fields and continue to be widely read and studied.

Free Full PDF Download Now Click Here

Please share this share this content.

- Opens in a new window

You Might Also Like

Dream Children by Charles Lamb | Dream Children: A Reverie | Charles Lamb | Summary | Key Points | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Critical Appreciation | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lesson

Of Youth and Age by Francis Bacon | Of Youth and Age | Francis Bacon | Francis Bacon as Essayist | Summary | Key Points | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Critical Appreciation | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lesson

On an Educational Reform by Hilaire Belloc | On an Educational Reform | Summary | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lessons

EL Dorado by RL Stevenson | EL Dorado | RL Stevenson | Free Full PDF – Easy Literary Lessons

Third Thoughts by EV Lucas | EV Lucas | Summary | Word Meaning | Key Points | Questions Answers | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lessons

Fearlessness by MK Gandhi | Fearlessness | MK Gandhi | Mahatma Gandhi | Summary | Key Points | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Critical Appreciation | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lesson

Popular Superstitions by Joseph Addison | Popular Superstitions | Joseph Addison | Summary | Key Points | Word Meaning | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lesson

Of Studies by Francis Bacon | Of Studies Essay | Francis Bacon | Explanation | Summary | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lessons

Getting Up on Cold Mornings by Leigh Hunt | Getting Up on Cold Mornings | Leigh Hunt | Summary | Key Points | Word Meaning | Questions Answers | Free PDF Download – Easy Literary Lesson

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

“Wisdom” vs. “Knowledge”: What’s The Difference?

Is it better to have wisdom or knowledge ? Can you have one without the other? And which comes first? If you’ve ever searched for acumen into these two brainy terms, we’re here to help break them down.

Wisdom and knowledge have quite a bit in common. Both words are primarily used as nouns that are related to learning. They’re listed as synonyms for one another in Thesaurus.com , and in some cases they may be used interchangeably.

In this article, we’ll explain the difference between knowledge and wisdom , what they mean and how their meanings overlap, and explain how to understand them with the help of some useful quotes.

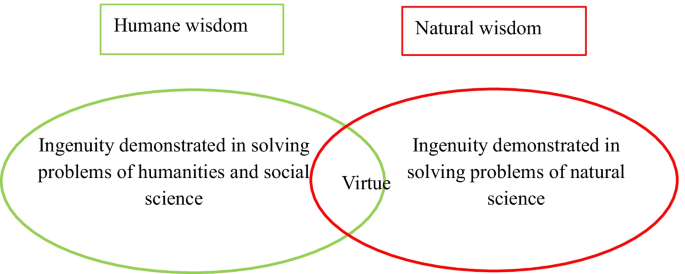

What is the difference between knowledge and wisdom ?

The word knowledge is defined first as the “acquaintance with facts, truths or principles, as from study or investigation; general erudition .” It is recorded at least by the 1300s as the Middle English knouleche , which combines the verb know (a verb that means “ to perceive or understand as fact or truth; to apprehend clearly and with certainty”) and – leche , which may be related to the same suffix we see in wedlock and conveys a sense of “action, practice, or state.”

Knowledge is typically gained through books, research, and delving into facts. Knowledge can also be gained in the bedroom ( hubba hubba !), as the term is sometimes used, albeit archaically , to describe sexual intercourse. As in: they had carnal knowledge of one another.

Wisdom is defined as “the state of being wise,” which means “having the power of discernment and judging properly as to what is true or right: possessing discernment , judgement, or discretion.” It’s older (recorded before the 900s), and joins wise and -dom , a suffix that can convey “general condition,” as in freedom . Wisdom is typically gained from experiences and acquired over time.

While wisdom and knowledge are synonyms, the other synonyms for each word, respectively, don’t overlap much. And they give more hints at each word’s unique meaning.

For example, other synonyms for knowledge include:

- familiarity

Other synonyms for wisdom include:

Go Behind The Words!

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

The primary difference between the two words is that wisdom involves a healthy dose of perspective and the ability to make sound judgments about a subject while knowledge is simply knowing. Anyone can become knowledgeable about a subject by reading, researching, and memorizing facts. It’s wisdom, however, that requires more understanding and the ability to determine which facts are relevant in certain situations. Wisdom takes knowledge and applies it with discernment based on experience, evaluation, and lessons learned.

A quote by an unknown author sums up the differences well: “Knowledge is knowing what to say. Wisdom is knowing when to say it.”

Wisdom is also about knowing when and how to use your knowledge, being able to put situations in perspective, and how to impart it to others. For example, you may be very knowledgeable about how to raise a baby after reading countless books, attending classes, and talking to wise friends and family members. When that precious little person comes home, however, most new parents would kill for an ounce of wisdom to help soothe their screaming baby … and their fears.

To put it another way, there is this simple fruit salad philosophy: “Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit. Wisdom is knowing not to put it in the fruit salad.”

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

What comes first: wisdom or knowledge ?

So which comes first, knowledge or wisdom? There’s no chicken-egg scenario here: knowledge always comes first. Wisdom is built upon knowledge. That means you can be both wise and knowledgeable, but you can’t be wise without being knowledgeable. And just because you’re knowledgeable doesn’t mean you’re wise … even though your teenager may feel differently.

As for how long it takes to achieve wisdom, and how you know when you have achieved it, that’s where things get murkier. Albert Einstein famously said, “Wisdom is not a product of schooling but of the lifelong attempt to acquire it.” So yeah, it’s one of those journey-not-destination things. There’s no limit to wisdom, however, and you can certainly gain degrees of it along the way.

So, there you have it. Have you wised up to the differences between the two words yet?

Commonly Confused

Hobbies & Passions

Current Events

Trending Words

[ sahyz -mik ]

Summary of ‘Knowledge and Wisdom’ by Bertrand Russell

- December 28, 2021

Main Summary [Brief]

In this essay, Russell differentiates between knowledge and wisdom. Knowledge and wisdom are different things. According to him, knowledge is defined as the acquisition of data and information, while wisdom is defined as the practical application and use of the knowledge to create value. Wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization.

Major Word Meanings of this Essay

proportion (n.): a part or share of a whole

absorb (v.): to take, draw or suck something in

distorting (v.): pull or twist out of shape

inculcate (v.): inplant, infuse, instil

bound up (v.): to limit something

fanatical (adj.): a person who is too enthusiastic about something

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell (1872–1970) was a British philosopher, logician, essayist and social critic best known for his work in mathematical logic and analytic philosophy. His most influential contributions include his championing of logicism (the view that mathematics is in some important sense reducible to logic), his refining of Gottlob Frege’s predicate calculus (which still forms the basis of most contemporary systems of logic), his defense of neutral monism (the view that the world consists of just one type of substance which is neither exclusively mental nor exclusively physical), and his theories of definite descriptions, logical atomism and logical types.

Summary of Russell’s Essay, Knowledge and Wisdom

“Never mistake knowledge for wisdom. One helps you make a living; the other helps you make a life.”

– Sandra Carey

Knowledge and wisdom are different things. According to Russell, knowledge is defined as the acquisition of data and information, while wisdom is defined as the practical application and use of the knowledge to create value. Wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization.

A sense of proportion is very much necessary for wisdom. By inventing medicine, a scientist may reduce the infant death-rate. Apparently, it leads to population explosion and shortage of food. The standard of life comes down. If misused, knowledge of atom can lead human to destruction by manufacturing nuclear weapon.

Knowledge without wisdom can be harmful. Even complete knowledge is not enough. For example, Hegel wrote with great knowledge about history, but made the Germans believe that they were a master race. It led to war. It is necessary, therefore to combine knowledge with feelings.

We need wisdom both in public and private life. We need wisdom to decide the goal of our life. We need it to free ourselves from personal prejudices. Wisdom is needed to avoid dislike for one another. Two persons may remain enemies because of their prejudice. If they can be told that we all have flaws then they may become friends.

Question Answer of Knowledge & Wisdom

a. What are the factors that contribute to wisdom?

Ans : – In the essay “Knowledge and Wisdom”, Bertrand Russell talks about several factors that contribute to wisdom. According to him, the factors that contribute to wisdom are :

i) a sense of proportion,

ii) comprehensiveness with broad feeling,

iii) emancipation from personal prejudices and tyranny of sensory perception,

iv) impartiality and

v) awareness of human needs and understanding.

b. What message does the writer try to convey with the examples of technicians?

Ans : – Russell has given some examples of technicians to convey the message that the lone technical knowledge can be harmful to humankind if that knowledge is applied without wisdom. They can’t find out how their knowledge in one field can be harmful in another field. For example, the discovery of medicine to decrease the infant mortality rate can cause population growth and food scarcity. Similarly, the knowledge of atomic theory can be misused in making atom bombs.

c. Which leaders does Russell say were able to mix knowledge and wisdom soundly?

Ans : – According to Russell, Queen Elizabeth I in England, Henry IV in France and Abraham Lincoln can mix knowledge and wisdom soundly. Queen Elizabeth I and Henry IV remained free from the errors of their time being Global Trade Starts Here Alibaba.com unaffected by the conflict between the Protestants and the Catholics. Similarly, Abraham Lincoln conducted a great war without ever departing from wisdom.

d. Why is wisdom needed not only in public ways but in private life equally?

Ans : – Wisdom is not only needed in public ways but also used in private life equally. It is needed in the choice of ends to be pursued and in emancipation from personal prejudice. In the lack of wisdom, we may fail in choosing the target of our life and we may not have sufficient patience and sufficient persuasiveness in convincing people.

e. What, according to Russell, the true aim of education?

Ans : – The true aim of education, according to Russell, is installing wisdom in people. It is wisdom that makes us utilize our knowledge in practical life purposefully without making any harm to humankind. Along with knowledge, people must have the wisdom to be good citizens.

f. Can wisdom be taught? If so, how?

Ans : – Yes, wisdom can be taught. The teaching of wisdom should have a larger intellectual element more than moral instruction. The disastrous results of hatred and narrow mindedness to those who feel them can be pointed out incidentally in the course of giving knowledge. For example, while teaching the composition of an atom, the disastrous results of it must be taught to eliminate its misuse such as making an atom bomb. Reference to the Context Answer the following questions.

a. According to Russell, “The Pursuit of Knowledge may become harmful unless it is combined with wisdom.” Justify this statement.

Ans : – Humans are curious creatures and they always want to learn new things. Most people have spent their whole lives in pursuit of knowledge. Some pieces of knowledge are noble and beneficial for humans whereas some pieces of knowledge are harmful to us. The knowledge which is combined with wisdom is useful for us because it addresses the total needs of mankind. The knowledge of atomic composition has become harmful to mankind because it is used in making bombs.

Similarly, Hegal, though he had great knowledge about history, made the Germans believe that they were a master race. It led to the great disastrous wars. So, it is necessary to combine knowledge with the feeling of humanity. We need it an event to decide the aim of our life. It makes us free from personal prejudices. Even noble things are applied unwisely in the lack of wisdom

b. What, according to Russell, is the essence of wisdom? And how can one acquire the very essence?

Ans : – According to Russell, the essence of wisdom is emancipation from the tyranny of being partiality. It makes our thoughts and feeling less personal and less concerned with our physical states. It is wisdom that makes us care and love the entire human race, it takes us into the higher stage of spirituality. It makes us be able to make the right decision, install a broad vision and unbiasedness in our minds. We can acquire the very essence by breaking the chain of the egoism of our sense, understanding the ends of human life, applying our knowledge wisely for the benefit of humans, finding noble and attainable goals of our life, controlling our sensory perceptions, being impartial gradually and loving others.

Reference Beyond the Text

a. Why is wisdom necessary in education? Discuss. Ans : It is wisdom that makes our mind broad and unbiased. When we gain wisdom, our thoughts and feelings become less personal. It makes us use our knowledge wisely. It helps us to utilize our knowledge for the benefit of humankind. When we have wisdom we love even our enemy, we completely get rid of ego, we don’t have any kind of prejudices.

If education/knowledge is one part of human life then wisdom is another part. If one compasses these both parts appropriately, then s/he become a perfect being. The goal of education is not only imparting knowledge but also creating good citizens. People may misuse the acquired knowledge if they don’t have wisdom and it doesn’t come automatically, it must be taught. It must be one of the goals of education and must be taught in schools. It must be planted and nursed in one’s mind with practical examples.

Understanding the Text

b. What message does the writer try to convey with the example of technicians?

c. Which leaders does Russell say were able to mix knowledge and wisdom soundly?

d. Why is wisdom needed not only in public ways, but in private life equally?

e. What, according to Russell, is the true aim of education?

g. Why does the world need more wisdom in the future? Reference to the context

a. According to Russel, “The pursuit of knowledge may become harmful unless it is combined with wisdom.” Justify this statement.

b. What, according to Russell, is the essence of wisdom? And how can one acquire the very essence?

Reference beyond the text

a. Why is wisdom necessary in education? Discuss.

b. How can you become wise? Do you think what you are doing in college contributes to wisdom?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You may like to read:

Teachers’ guide class 10 english pdf download || english guide class10.

- July 29, 2024

Role of Language in Mathematics Education

- July 12, 2024

Reading – II Flowers in Russian Culture || NEB Class 10 History & Culture

- June 23, 2024

Cabbage White – Class 10 Exercise

- May 15, 2024

Summary of Russell’s Essay, Knowledge and Wisdom

“Never mistake knowledge for wisdom. One helps you make a living; the other helps you make a life.”

– Sandra Carey

Knowledge and wisdom are different things. According to Russell , knowledge is defined as the acquisition of data and information, while wisdom is defined as the practical application and use of the knowledge to create value. Wisdom is gained through learning and practical experience, not just memorization.

A sense of proportion is very much necessary for wisdom . By inventing medicine, a scientist may reduce the infant death-rate. Apparently, it leads to population explosion and shortage of food. The standard of life comes down. If misused, knowledge of atom can lead human to destruction by manufacturing nuclear weapon.

Knowledge without wisdom can be harmful. Even complete knowledge is not enough. For example, Hegel wrote with great

knowledge about history, but made the Germans believe that they were a master race. It led to war. It is necessary, therefore to combine knowledge with feelings.

We need wisdom both in public and private life. We need wisdom to decide the goal of our life. We need it to free ourselves from personal prejudices. Wisdom is needed to avoid dislike for one another. Two persons may remain enemies because of their prejudice. If they can be told that we all have flaws then they may become friends.

- Russell’s View on World Government in his Essay The Future of Mankind

So, ‘Hate Hatred’ should be our slogan. Wisdom lies in freeing ourselves from the control of our sense organs. Our ego develops through our senses. We cannot be free from the sense of sight, sound and touch. We know the world primarily through our senses. As we grow we discover that there are other things also. We start recognizing them. Thus we give up thinking of ourselves alone. We start thinking of other people and grow wiser. We give up on our ego. Wisdom comes when we start loving others.

Russell feels that wisdom can be taught as a goal of education. Even though we are born unwise which we cannot help, we can cultivate wisdom. Queen Elizabeth I, Henry IV and Abraham Lincoln, are some impressive personalities who fused vigour with wisdom and fought the evil.

Related posts:

- Russell’s View on World Government in his Essay The Future of Mankind

- Indian English Poetry and Poets: An Essay

- Character Analysis of Sir Roger de Coverley in Addison’s Essay

- Bertrand Russell as a Prose Writer

- Summary of E. V. Lucas’ Essay The Town Week

8 thoughts on “Summary of Russell’s Essay, Knowledge and Wisdom”

Great article with excellent idea!Thank you for such a valuable article. I really appreciate for this great information.. quora

Really nice and well informative article wrote in a very concise and beautiful manner

thank you for a great post. กาแฟออแกนิค

Critical analysis plz post

An examination essay dissects the likenesses and contrasts between two items or thoughts. Correlation essays may incorporate an assessment, if the realities show that on item or thought is better than another. narrative essay outline

A doctor may invent medicine which reduces infant mortality rate. Consequently, it may lead to population explosion and shortage of food. That shows a lack of KNOWLEDGE itself. Not knowing the consequences rather than “Wisdom” stuff that Russell talks about here

I am satisfied with the arrangement of your post. You are really a talented person I have ever seen.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

From Knowledge to Wisdom

The Key to Wisdom

Nicholas Maxwell University College London

Section 1 of " Arguing for Wisdom in the University: An Intellectual Autobiography ", Philosophia , vol 40, no. 4, 2012. Nearly forty years ago I discovered a profoundly significant idea - or so I believe. Since then, I have expounded and developed the idea in six books [1] and countless articles published in academic journals and other books. [2] I have talked about the idea in universities and at conferences all over the UK, in Europe, the USA and Canada. And yet, alas, despite all this effort, few indeed are those who have even heard of the idea. I have not even managed to communicate the idea to my fellow philosophers. What did I discover? Quite simply: the key to wisdom. For over two and a half thousand years, philosophy (which means "love of wisdom") has sought in vain to discover how humanity might learn to become wise - how we might learn to create an enlightened world. For the ancient Greek philosophers, Socrates, Plato and the rest, discovering how to become wise was the fundamental task for philosophy. In the modern period, this central, ancient quest has been laid somewhat to rest, not because it is no longer thought important, but rather because the quest is seen as unattainable. The record of savagery and horror of the last century is so extreme and terrible that the search for wisdom, more important than ever, has come to seem hopeless, a quixotic fantasy. Nevertheless, it is this ancient, fundamental problem, lying at the heart of philosophy, at the heart, indeed, of all of thought, morality, politics and life, that I have solved. Or so I believe. When I say I have discovered the key to wisdom, I should say, more precisely, that I have discovered the methodological key to wisdom. Or perhaps, more modestly, I should say that I have discovered that science contains, locked up in its astounding success in acquiring knowledge and understanding of the universe, the methodological key to wisdom. I have discovered a recipe for creating a kind of organized inquiry rationally designed and devoted to helping humanity learn wisdom, learn to create a more enlightened world. What we have is a long tradition of inquiry - extraordinarily successful in its own terms - devoted to acquiring knowledge and technological know-how. It is this that has created the modern world, or at least made it possible. But scientific knowledge and technological know-how are ambiguous blessings, as more and more people, these days, are beginning to recognize. They do not guarantee happiness. Scientific knowledge and technological know-how enormously increase our power to act. In endless ways, this vast increase in our power to act has been used for the public good - in health, agriculture, transport, communications, and countless other ways. But equally, this enhanced power to act can be used to cause human harm, whether unintentionally, as in environmental damage (at least initially), or intentionally, as in war. It is hardly too much to say that all our current global problems have come about because of science and technology. The appalling destructiveness of modern warfare and terrorism, vast inequalities in wealth and standards of living between first and third worlds, rapid population growth, environmental damage - destruction of tropical rain forests, rapid extinction of species, global warming, pollution of sea, earth and air, depletion of finite natural resources - all only exist today because of modern science and technology. Science and technology lead to modern industry and agriculture, to modern medicine and hygiene, and thus in turn to population growth, to modern armaments, conventional, chemical, biological and nuclear, to destruction of natural habitats, extinction of species, pollution, and to immense inequalities of wealth across the globe. Science without wisdom, we might say, is a menace. It is the crisis behind all the others. When we lacked our modern, terrifying powers to act, before the advent of science, lack of wisdom did not matter too much: we were bereft of the power to inflict too much damage on ourselves and the planet. Now that we have modern science, and the unprecedented powers to act that it has bequeathed to us, wisdom has become, not a private luxury, but a public necessity. If we do not rapidly learn to become wiser, we are doomed to repeat in the 21st century all the disasters and horrors of the 20th: the horrifyingly destructive wars, the dislocation and death of millions, the degradation of the world we live in. Only this time round it may all be much worse, as the population goes up, the planet becomes ever more crowded, oil and other resources vital to our way of life run out, weapons of mass destruction become more and more widely available for use, and deserts and desolation spread. The ancient quest for wisdom has become a matter of desperate urgency. It is hardly too much to say that the future of the world is at stake. But how can such a quest possibly meet with success? Wisdom, surely, is not something that we can learn and teach, as a part of our normal education, in schools and universities? This is my great discovery! Wisdom can be learnt and taught in schools and universities. It must be so learnt and taught. Wisdom is indeed the proper fundamental objective for the whole of the academic enterprise: to help humanity learn how to nurture and create a wiser world. But how do we go about creating a kind of education, research and scholarship that really will help us learn wisdom? Would not any such attempt destroy what is of value in what we have at present, and just produce hot air, hypocrisy, vanity and nonsense? Or worse, dogma and religious fundamentalism? What, in any case, is wisdom? Is not all this just an abstract philosophical fantasy? The answer, as I have already said, lies locked away in what may seem a highly improbably place: science! This will seem especially improbable to many of those most aware of environmental issues, and most suspicious of the role of modern science and technology in modern life. How can science contain the methodological key to wisdom when it is precisely this science that is behind so many of our current troubles? But a crucial point must be noted. Modern scientific and technological research has met with absolutely astonishing, unprecedented success, as long as this success is interpreted narrowly, in terms of the production of expert knowledge and technological know-how. Doubts may be expressed about whether humanity as a whole has made progress towards well being or happiness during the last century or so. But there can be no serious doubt whatsoever that science has made staggering intellectual progress in increasing expert knowledge and know-how, during such a period. It is this astonishing intellectual progress that makes science such a powerful but double-edged tool, for good and for bad. At once the question arises: Can we learn from the incredible intellectual progress of science how to achieve progress in other fields of human endeavour? Is scientific progress exportable, as it were, to other areas of life? More precisely, can the progress-achieving methods of science be generalized so that they become fruitful for other worthwhile, problematic human endeavours, in particular the supremely worthwhile, supremely problematic endeavour of creating a good and wise world? My great idea - that this can indeed be done - is not entirely new (as I was to learn after making my discovery). It goes back to the 18th century Enlightenment. This was indeed the key idea of the Enlightenment, especially the French Enlightenment: to learn from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards an enlightened world. And the philosophes of the Enlightenment, men such as Voltaire, Diderot and Condorcet, did what they could to put this magnificent, profound idea into practice in their lives. They fought dictatorial power, superstition, and injustice with weapons no more lethal than those of argument and wit. They gave their support to the virtues of tolerance, openness to doubt, readiness to learn from criticism and from experience. Courageously and energetically they laboured to promote reason and enlightenment in personal and social life. Unfortunately, in developing the Enlightenment idea intellectually, the philosophes blundered. They botched the job. They developed the Enlightenment idea in a profoundly defective form, and it is this immensely influential, defective version of the idea, inherited from the 18th century, which may be called the "traditional" Enlightenment, that is built into early 21st century institutions of inquiry. Our current traditions and institutions of learning, when judged from the standpoint of helping us learn how to become more enlightened, are defective and irrational in a wholesale and structural way, and it is this which, in the long term, sabotages our efforts to create a more civilized world, and prevents us from avoiding the kind of horrors we have been exposed to during the last century. The task before us is thus not that of creating a kind of inquiry devoted to improving wisdom out of the blue, as it were, with nothing to guide us except two and a half thousand years of failed philosophical discussion. Rather, the task is the much more straightforward, practical and well-defined one of correcting the structural blunders built into academic inquiry inherited from the Enlightenment. We already have a kind of academic inquiry designed to help us learn wisdom. The problem is that the design is lousy. It is, as I have said, a botched job. It is like a piece of engineering that kills people because of faulty design - a bridge that collapses, or an aeroplane that falls out of the sky. A quite specific task lies before us: to diagnose the blunders we have inherited from the Enlightenment, and put them right. So here, briefly, is the diagnosis. The philosophes of the 18th century assumed, understandably enough, that the proper way to implement the Enlightenment programme was to develop social science alongside natural science. Francis Bacon had already stressed the importance of improving knowledge of the natural world in order to achieve social progress. The philosophes generalized this, holding that it is just as important to improve knowledge of the social world. Thus the philosophes set about creating the social sciences: history, anthropology, political economy, psychology, sociology. This had an immense impact. Throughout the 19th century the diverse social sciences were developed, often by non-academics, in accordance with the Enlightenment idea. Gradually, universities took notice of these developments until, by the mid 20th century, all the diverse branches of the social sciences, as conceived of by the Enlightenment, were built into the institutional structure of universities as recognized academic disciplines. The outcome is what we have today, knowledge-inquiry as we may call it, a kind of inquiry devoted in the first instance to the pursuit of knowledge. But, from the standpoint of creating a kind of inquiry designed to help humanity learn how to become enlightened and civilized, which was the original idea, all this amounts to a series of monumental blunders. In order to implement properly the basic Enlightenment idea of learning from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards a civilized world, it is essential to get the following three things right. 1. The progress-achieving methods of science need to be correctly identified. 2. These methods need to be correctly generalized so that they become fruitfully applicable to any worthwhile, problematic human endeavour, whatever the aims may be, and not just applicable to the one endeavour of acquiring knowledge. 3. The correctly generalized progress-achieving methods then need to be exploited correctly in the great human endeavour of trying to make social progress towards an enlightened, civilized world. Unfortunately, the philosophes of the Enlightenment got all three points wrong. They failed to capture correctly the progress-achieving methods of natural science; they failed to generalize these methods properly; and, most disastrously of all, they failed to apply them properly so that humanity might learn how to become civilized by rational means. Instead of seeking to apply the progress-achieving methods of science, after having been appropriately generalized, to the task of creating a better world, the philosophes applied scientific method to the task of creating social science. Instead of trying to make social progress towards an enlightened world, they set about making scientific progress in knowledge of social phenomena. That the philosophes made these blunders in the 18th century is forgivable; what is unforgivable is that these blunders still remain unrecognized and uncorrected today, over two centuries later. Instead of correcting the blunders, we have allowed our institutions of learning to be shaped by them as they have developed throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, so that now the blunders are an all-pervasive feature of our world. The Enlightenment, and what it led to, has long been criticized, by the Romantic movement, by what Isaiah Berlin has called 'the counter-Enlightenment', and more recently by the Frankfurt school, by postmodernists and others. But these standard objections are, from my point of view, entirely missing the point. In particular, my idea is the very opposite of all those anti-rationalist, romantic and postmodernist views which object to the way the Enlightenment gives far too great an importance to natural science and to scientific rationality. My discovery is that what is wrong with the traditional Enlightenment, and the kind of academic inquiry we now possess derived from it - knowledge-inquiry - is not too much 'scientific rationality' but, on the contrary, not enough. It is the glaring, wholesale irrationality of contemporary academic inquiry, when judged from the standpoint of helping humanity learn how to become more civilized, that is the problem. But, the cry will go up, wisdom has nothing to do with reason. And reason has nothing to do with wisdom. On the contrary! It is just such an item of conventional 'wisdom' that my great idea turns on its head. Once both reason and wisdom have been rightly understood, and the irrationality of academic inquiry as it exists at present has been appreciated, it becomes obvious that it is precisely reason that we need to put into practice in our personal, social, institutional and global lives if our lives, at all these levels, are to become imbued with a bit more wisdom. We need, in short, a new, more rigorous kind of inquiry which has, as its basic task, to seek and promote wisdom. We may call this new kind of inquiry wisdom-inquiry. But what is wisdom? This is how I define it in From Knowledge to Wisdom, a book published some years ago now, in 1984, in which I set out my 'great idea' in some detail: "[wisdom is] the desire, the active endeavour, and the capacity to discover and achieve what is desirable and of value in life, both for oneself and for others. Wisdom includes knowledge and understanding but goes beyond them in also including: the desire and active striving for what is of value, the ability to see what is of value, actually and potentially, in the circumstances of life, the ability to experience value, the capacity to use and develop knowledge, technology and understanding as needed for the realization of value. Wisdom, like knowledge, can be conceived of, not only personal terms, but also in institutional or social terms. We can thus interpret [wisdom-inquiry] as asserting: the basic task of rational inquiry is to help us develop wiser ways of living, wiser institutions, customs and social relations, a wiser world." (From Knowledge to Wisdom, p. 66.) What, then, are the three blunders of the Enlightenment, still built into the intellectual/institutional structure of academia? First, the philosophes failed to capture correctly the progress-achieving methods of natural science. From D'Alembert in the 18th century to Karl Popper in the 20th, the widely held view, amongst both scientists and philosophers, has been (and continues to be) that science proceeds by assessing theories impartially in the light of evidence, no permanent assumption being accepted by science about the universe independently of evidence. Preference may be given to simple, unified or explanatory theories, but not in such a way that nature herself is, in effect, assumed to be simple, unified or comprehensible. This orthodox view, which I call standard empiricism is, however, untenable. If taken literally, it would instantly bring science to a standstill. For, given any accepted fundamental theory of physics, T, Newtonian theory say, or quantum theory, endlessly many empirically more successful rivals can be concocted which agree with T about observed phenomena but disagree arbitrarily about some unobserved phenomena, and successfully predict phenomena, in an ad hoc way, that T makes false predictions about, or no predictions. Physics would be drowned in an ocean of such empirically more successful rival theories. In practice, these rivals are excluded because they are disastrously disunified. Two considerations govern acceptance of theories in physics: empirical success and unity. In demanding unity, we demand of a fundamental physical theory that it ascribes the same dynamical laws to the phenomena to which the theory applies. But in persistently accepting unified theories, to the extent of rejecting disunified rivals that are just as, or even more, empirically successful, physics makes a big persistent assumption about the universe. The universe is such that all disunified theories are false. It has some kind of unified dynamic structure. It is physically comprehensible in the sense that explanations for phenomena exist to be discovered. But this untestable (and thus metaphysical) assumption that the universe is physically comprehensible is profoundly problematic. Science is obliged to assume, but does not know, that the universe is comprehensible. Much less does it know that the universe is comprehensible in this or that way. A glance at the history of physics reveals that ideas have changed dramatically over time. In the 17th century there was the idea that the universe consists of corpuscles, minute billiard balls, which interact only by contact. This gave way to the idea that the universe consists of point-particles surrounded by rigid, spherically symmetrical fields of force, which in turn gave way to the idea that there is one unified self-interacting field, varying smoothly throughout space and time. Nowadays we have the idea that everything is made up of minute quantum strings embedded in ten or eleven dimensions of space-time. Some kind of assumption along these lines must be made but, given the historical record, and given that any such assumption concerns the ultimate nature of the universe, that of which we are most ignorant, it is only reasonable to conclude that it is almost bound to be false. The way to overcome this fundamental dilemma inherent in the scientific enterprise is to construe physics as making a hierarchy of metaphysical assumptions concerning the comprehensibility and knowability of the universe, these assumptions asserting less and less as one goes up the hierarchy, and thus becoming more and more likely to be true, and more nearly such that their truth is required for science, or the pursuit of knowledge, to be possible at all. In this way a framework of relatively insubstantial, unproblematic, fixed assumptions and associated methods is created within which much more substantial and problematic assumptions and associated methods can be changed, and indeed improved, as scientific knowledge improves. Put another way, a framework of relatively unspecific, unproblematic, fixed aims and methods is created within which much more specific and problematic aims and methods evolve as scientific knowledge evolves. There is positive feedback between improving knowledge, and improving aims-and-methods, improving knowledge-about-how-to-improve-knowledge. This is the nub of scientific rationality, the methodological key to the unprecedented success of science. Science adapts its nature to what it discovers about the nature of the universe. This hierarchical conception of physics, which I call aim-oriented empiricism, can readily be generalized to take into account problematic assumptions associated with the aims of science having to with values, and the social uses or applications of science. It can be generalized so as to apply to the different branches of natural science. Different sciences have different specific aims, and so different specific methods although, throughout natural science there is the common meta-methodology of aim-oriented empiricism. So much for the first blunder of the traditional Enlightenment, and how to put it right. [3] Second, having failed to identify the methods of science correctly, the philosophes naturally failed to generalize these methods properly. They failed to appreciate that the idea of representing the problematic aims (and associated methods) of science in the form of a hierarchy can be generalized and applied fruitfully to other worthwhile enterprises besides science. Many other enterprises have problematic aims - problematic because aims conflict, and because what we seek may be unrealizable, undesirable, or both. Such enterprises, with problematic aims, would benefit from employing a hierarchical methodology, generalized from that of science, thus making it possible to improve aims and methods as the enterprise proceeds. There is the hope that, as a result of exploiting in life methods generalized from those employed with such success in science, some of the astonishing success of science might be exported into other worthwhile human endeavours, with problematic aims quite different from those of science. Third, and most disastrously of all, the philosophes failed completely to try to apply such generalized, hierarchical progress-achieving methods to the immense, and profoundly problematic enterprise of making social progress towards an enlightened, wise world. The aim of such an enterprise is notoriously problematic. For all sorts of reasons, what constitutes a good world, an enlightened, wise or civilized world, attainable and genuinely desirable, must be inherently and permanently problematic. Here, above all, it is essential to employ the generalized version of the hierarchical, progress-achieving methods of science, designed specifically to facilitate progress when basic aims are problematic. It is just this that the philosophes failed to do. Instead of applying the hierarchical methodology to social life, the philosophes sought to apply a seriously defective conception of scientific method to social science, to the task of making progress towards, not a better world, but to better knowledge of social phenomena. And this ancient blunder, developed throughout the 19th century by J.S. Mill, Karl Marx and many others, and built into academia in the early 20th century with the creation of the diverse branches of the social sciences in universities all over the world, is still built into the institutional and intellectual structure of academia today, inherent in the current character of social science. Properly implemented, in short, the Enlightenment idea of learning from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards an enlightened world would involve developing social inquiry, not primarily as social science, but rather as social methodology, or social philosophy. A basic task would be to get into personal and social life, and into other institutions besides that of science - into government, industry, agriculture, commerce, the media, law, education, international relations - hierarchical, progress-achieving methods (designed to improve problematic aims) arrived at by generalizing the methods of science. A basic task for academic inquiry as a whole would be to help humanity learn how to resolve its conflicts and problems of living in more just, cooperatively rational ways than at present. The fundamental intellectual and humanitarian aim of inquiry would be to help humanity acquire wisdom - wisdom being, as I have already indicated, the capacity to realize (apprehend and create) what is of value in life, for oneself and others. One outcome of getting into social and institutional life the kind of aim-evolving, hierarchical methodology indicated above, generalized from science, is that it becomes possible for us to develop and assess rival philosophies of life as a part of social life, somewhat as theories are developed and assessed within science. Such a hierarchical methodology provides a framework within which competing views about what our aims and methods in life should be - competing religious, political and moral views - may be cooperatively assessed and tested against broadly agreed, unspecific aims (high up in the hierarchy of aims) and the experience of personal and social life. There is the possibility of cooperatively and progressively improving such philosophies of life (views about what is of value in life and how it is to be achieved) much as theories are cooperatively and progressively improved in science. Wisdom-inquiry, because of its greater rigour, has intellectual standards that are, in important respects, different from those of knowledge-inquiry. Whereas knowledge-inquiry demands that emotions and desires, values, human ideals and aspirations, philosophies of life be excluded from the intellectual domain of inquiry, wisdom-inquiry requires that they be included. In order to discover what is of value in life it is essential that we attend to our feelings and desires. But not everything we desire is desirable, and not everything that feels good is good. Feelings, desires and values need to be subjected to critical scrutiny. And of course feelings, desires and values must not be permitted to influence judgements of factual truth and falsity. Wisdom-inquiry embodies a synthesis of traditional Rationalism and Romanticism. It includes elements from both, and it improves on both. It incorporates Romantic ideals of integrity, having to do with motivational and emotional honesty, honesty about desires and aims; and at the same time it incorporates traditional Rationalist ideals of integrity, having to do with respect for objective fact, knowledge, and valid argument. Traditional Rationalism takes its inspiration from science and method; Romanticism takes its inspiration from art, from imagination, and from passion. Wisdom-inquiry holds art to have a fundamental rational role in inquiry, in revealing what is of value, and unmasking false values; but science, too, is of fundamental importance. What we need, for wisdom, is an interplay of sceptical rationality and emotion, an interplay of mind and heart, so that we may develop mindful hearts and heartfelt minds (as I put it in my first book What's Wrong With Science?). It is time we healed the great rift in our culture, so graphically depicted by C. P. Snow. The revolution we require - intellectual, institutional and cultural - if it ever comes about, will be comparable in its long-term impact to that of the Renaissance, the scientific revolution, or the Enlightenment. The outcome will be traditions and institutions of learning rationally designed to help us realize what is of value in life. There are a few scattered signs that this intellectual revolution, from knowledge to wisdom, is already under way. It will need, however, much wider cooperative support - from scientists, scholars, students, research councils, university administrators, vice chancellors, teachers, the media and the general public - if it is to become anything more than what it is at present, a fragmentary and often impotent movement of protest and opposition, often at odds with itself, exercising little influence on the main body of academic work. I can hardly imagine any more important work for anyone associated with academia than, in teaching, learning and research, to help promote this revolution. Notes [1] What's Wrong With Science? (Bran's Head Books, 1976), From Knowledge to Wisdom (Blackwell, 1984; 2nd edition, Pentire Press, 2007), The Comprehensibility of the Universe (Oxford University Press, 1998, paperback 2003), and The Human World in the Physical Universe: Consciousness, Free Will and Evolution (Rowman and Littlefield, 2001), Is Science Neurotic? (Imperial College Press, 2004), Cutting God in Half - And Putting the Pieces Together Again (Pentire Press, 2010). For critical discussion see L. McHenry, ed., Science and the Pursuit of Wisdom: Studies in the Philosophy of Nicholas Maxwell (Ontos Verlag, 2009).

Back to text