Essay on Junk Food

Essay generator.

In the contemporary world, one cannot escape the prevalence of junk food. From ubiquitous fast-food chains to convenience store shelves stocked with sugary snacks and processed treats, junk food has become an integral part of modern diets. It’s quick, tasty, and often affordable, making it a popular choice for people of all ages. However, it is imperative that we delve deeper into the subject of junk food, exploring its definition, its effects on our health, and the measures we can take to promote a healthier lifestyle.

Before we delve into the complex implications of junk food, it is essential to define what it actually is. Junk food refers to a category of food that is typically high in calories, sugar, unhealthy fats, and salt while being low in essential nutrients like vitamins, minerals, and fiber. These foods are often processed and manufactured with additives and preservatives to enhance their taste and shelf life. Common examples include fast food items like burgers, fries, and pizza, as well as sugary beverages, candies, and chips.

The Temptation of Junk Food

Junk food’s allure lies in its taste and convenience. The combination of fats, sugars, and salt in these foods can trigger a pleasurable response in the brain, similar to what occurs with addictive substances. This pleasure reinforces the desire to consume these foods repeatedly. Additionally, the fast-paced nature of modern life has led to an increased reliance on convenience foods, many of which fall into the category of junk food.

The Health Consequences of Junk Food

While junk food may offer immediate satisfaction for our taste buds and fill our stomachs, it also carries severe health consequences that extend beyond the momentary pleasure of consumption.

- Weight Gain and Obesity: Junk food is often calorie-dense, and excessive consumption can lead to weight gain and obesity. Obesity is associated with numerous health problems, including diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancer.

- Nutrient Deficiency: Junk food is notoriously low in essential nutrients like vitamins and minerals. Overreliance on these foods can lead to nutrient deficiencies, weakening the immune system and impairing overall health.

- Blood Sugar Imbalance: Sugary junk foods can cause rapid spikes and crashes in blood sugar levels, leading to increased hunger, irritability, and cravings for more unhealthy snacks.

- Heart Health: The high levels of unhealthy fats and salt in junk food can raise blood pressure and increase the risk of heart disease.

- Dental Problems: Sugary snacks and beverages are a leading cause of dental cavities and gum disease.

- Mental Health: There is evidence linking the consumption of junk food to poor mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety.

- Addictive Behavior: The combination of sugars, fats, and salt in junk food can trigger addictive behavior, making it difficult for individuals to resist and moderate their consumption.

The Impact on Children

Children are particularly vulnerable to the allure of junk food. Advertisements targeting them are omnipresent, and the easy availability of sugary and processed snacks only adds to the problem. Poor eating habits developed during childhood can have lasting consequences on health. Childhood obesity, for example, can lead to a lifetime of health issues.

The Need for Education and Awareness

In the battle against junk food and its detrimental effects on health, education and awareness play a vital role. It is crucial to inform students and the general public about the risks associated with excessive consumption of junk food. This education should encompass the nutritional value of foods, the importance of a balanced diet, and the long-term consequences of unhealthy eating habits.

Schools and educational institutions have a significant role to play in this regard. They should incorporate nutrition education into their curricula, teaching students about making informed food choices and understanding food labels. Encouraging healthy eating habits at a young age can have a profound impact on students’ future well-being.

Promoting Healthier Alternatives

While it’s important to acknowledge the challenges posed by junk food, it’s equally essential to explore solutions and promote healthier alternatives. Here are some strategies to encourage better eating habits:

- Access to Nutritious Food: Efforts should be made to ensure that nutritious food options are readily available and affordable. This includes providing healthier meal choices in schools and workplaces and promoting the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins.

- Nutrition Labeling: Clear and easy-to-understand nutrition labels on packaged foods can empower consumers to make informed choices. Understanding serving sizes, calorie content, and nutrient values can guide individuals toward healthier options.

- Cooking Skills: Teaching students and adults how to prepare balanced meals from fresh ingredients can instill a lifelong appreciation for home-cooked food. Cooking classes and workshops can be valuable in this regard.

- Reducing Marketing to Children: Regulations should be in place to limit the marketing of junk food to children. This includes restrictions on advertising in schools, on children’s programming, and through digital media channels.

- Role of Parents and Caregivers: Parents and caregivers play a pivotal role in shaping children’s eating habits. Setting a positive example through their own food choices and providing a variety of nutritious foods at home can establish a strong foundation for healthy eating.

- Physical Activity: Encouraging regular physical activity is essential for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Schools and communities should provide opportunities for physical exercise and play.

- Government Policies: Governments can implement policies such as sugar taxes, restrictions on unhealthy food advertising, and regulations on school lunch programs to promote healthier eating habits.

In conclusion, junk food is a prevalent and tempting part of modern diets, but it comes with significant health consequences. It is essential to educate students and the general public about the risks associated with excessive junk food consumption and promote healthier alternatives. By emphasizing nutrition education, access to nutritious food, cooking skills, and responsible marketing practices, we can work towards a healthier future where individuals make informed food choices, leading to improved overall well-being and a reduced burden of diet-related diseases. It is a collective effort that involves individuals, families, communities, educational institutions, and policymakers. Together, we can navigate the path to a healthier future and help students make choices that support their long-term health and vitality.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Generate an essay on the importance of extracurricular activities for student development

Write an essay discussing the role of technology in modern education.

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

The Impacts of Junk Food on Health

Energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, otherwise known as junk foods, have never been more accessible and available. Young people are bombarded with unhealthy junk-food choices daily, and this can lead to life-long dietary habits that are difficult to undo. In this article, we explore the scientific evidence behind both the short-term and long-term impacts of junk food consumption on our health.

Introduction

The world is currently facing an obesity epidemic, which puts people at risk for chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes. Junk food can contribute to obesity and yet it is becoming a part of our everyday lives because of our fast-paced lifestyles. Life can be jam-packed when you are juggling school, sport, and hanging with friends and family! Junk food companies make food convenient, tasty, and affordable, so it has largely replaced preparing and eating healthy homemade meals. Junk foods include foods like burgers, fried chicken, and pizza from fast-food restaurants, as well as packaged foods like chips, biscuits, and ice-cream, sugar-sweetened beverages like soda, fatty meats like bacon, sugary cereals, and frozen ready meals like lasagne. These are typically highly processed foods , meaning several steps were involved in making the food, with a focus on making them tasty and thus easy to overeat. Unfortunately, junk foods provide lots of calories and energy, but little of the vital nutrients our bodies need to grow and be healthy, like proteins, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Australian teenagers aged 14–18 years get more than 40% of their daily energy from these types of foods, which is concerning [ 1 ]. Junk foods are also known as discretionary foods , which means they are “not needed to meet nutrient requirements and do not belong to the five food groups” [ 2 ]. According to the dietary guidelines of Australian and many other countries, these five food groups are grains and cereals, vegetables and legumes, fruits, dairy and dairy alternatives, and meat and meat alternatives.

Young people are often the targets of sneaky advertising tactics by junk food companies, which show our heroes and icons promoting junk foods. In Australia, cricket, one of our favorite sports, is sponsored by a big fast-food brand. Elite athletes like cricket players are not fuelling their bodies with fried chicken, burgers, and fries! A study showed that adolescents aged 12–17 years view over 14.4 million food advertisements in a single year on popular websites, with cakes, cookies, and ice cream being the most frequently advertised products [ 3 ]. Another study examining YouTube videos popular amongst children reported that 38% of all ads involved a food or beverage and 56% of those food ads were for junk foods [ 4 ].

What Happens to Our Bodies Shortly After We Eat Junk Foods?

Food is made up of three major nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. There are also vitamins and minerals in food that support good health, growth, and development. Getting the proper nutrition is very important during our teenage years. However, when we eat junk foods, we are consuming high amounts of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, which are quickly absorbed by the body.

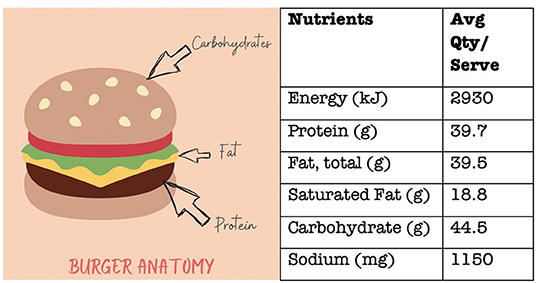

Let us take the example of eating a hamburger. A burger typically contains carbohydrates from the bun, proteins and fats from the beef patty, and fats from the cheese and sauce. On average, a burger from a fast-food chain contains 36–40% of your daily energy needs and this does not account for any chips or drinks consumed with it ( Figure 1 ). This is a large amount of food for the body to digest—not good if you are about to hit the cricket pitch!

- Figure 1 - The nutritional composition of a popular burger from a famous fast-food restaurant, detailing the average quantity per serving and per 100 g.

- The carbohydrates of a burger are mainly from the bun, while the protein comes from the beef patty. Large amounts of fat come from the cheese and sauce. Based on the Australian dietary guidelines, just one burger can be 36% of the recommended daily energy intake for teenage boys aged 12–15 years and 40% of the recommendations for teenage girls 12–15 years.

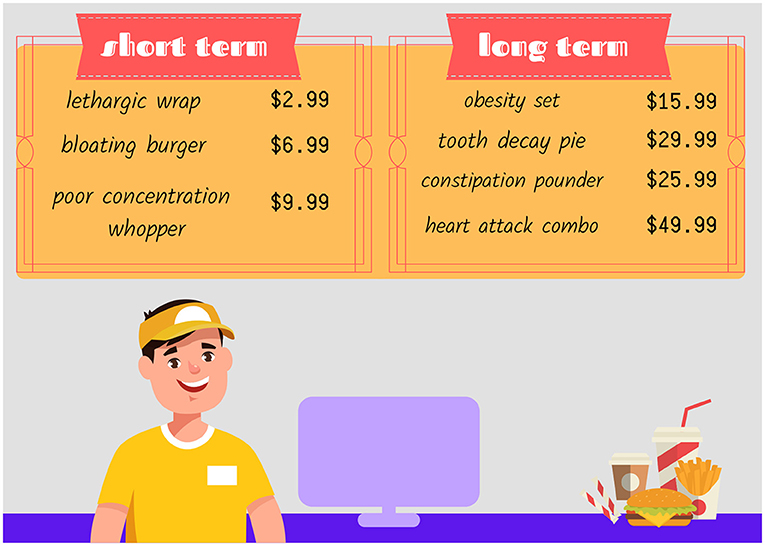

A few hours to a few days after eating rich, heavy foods such as a burger, unpleasant symptoms like tiredness, poor sleep, and even hunger can result ( Figure 2 ). Rather than providing an energy boost, junk foods can lead to a lack of energy. For a short time, sugar (a type of carbohydrate) makes people feel energized, happy, and upbeat as it is used by the body for energy. However, refined sugar , which is the type of sugar commonly found in junk foods, leads to a quick drop in blood sugar levels because it is digested quickly by the body. This can lead tiredness and cravings [ 5 ].

- Figure 2 - The short- and long-term impacts of junk food consumption.

- In the short-term, junk foods can make you feel tired, bloated, and unable to concentrate. Long-term, junk foods can lead to tooth decay and poor bowel habits. Junk foods can also lead to obesity and associated diseases such as heart disease. When junk foods are regularly consumed over long periods of time, the damages and complications to health are increasingly costly.

Fiber is a good carbohydrate commonly found in vegetables, fruits, barley, legumes, nuts, and seeds—foods from the five food groups. Fiber not only keeps the digestive system healthy, but also slows the stomach’s emptying process, keeping us feeling full for longer. Junk foods tend to lack fiber, so when we eat them, we notice decreasing energy and increasing hunger sooner.

Foods such as walnuts, berries, tuna, and green veggies can boost concentration levels. This is particularly important for young minds who are doing lots of schoolwork. These foods are what most elite athletes are eating! On the other hand, eating junk foods can lead to poor concentration. Eating junk foods can lead to swelling in the part of the brain that has a major role in memory. A study performed in humans showed that eating an unhealthy breakfast high in fat and sugar for 4 days in a row caused disruptions to the learning and memory parts of the brain [ 6 ].

Long-Term Impacts of Junk Foods

If we eat mostly junk foods over many weeks, months, or years, there can be several long-term impacts on health ( Figure 2 ). For example, high saturated fat intake is strongly linked with high levels of bad cholesterol in the blood, which can be a sign of heart disease. Respected research studies found that young people who eat only small amounts of saturated fat have lower total cholesterol levels [ 7 ].

Frequent consumption of junk foods can also increase the risk of diseases such as hypertension and stroke. Hypertension is also known as high blood pressure and a stroke is damage to the brain from reduced blood supply, which prevents the brain from receiving the oxygen and nutrients it needs to survive. Hypertension and stroke can occur because of the high amounts of cholesterol and salt in junk foods.

Furthermore, junk foods can trigger the “happy hormone,” dopamine , to be released in the brain, making us feel good when we eat these foods. This can lead us to wanting more junk food to get that same happy feeling again [ 8 ]. Other long-term effects of eating too much junk food include tooth decay and constipation. Soft drinks, for instance, can cause tooth decay due to high amounts of sugar and acid that can wear down the protective tooth enamel. Junk foods are typically low in fiber too, which has negative consequences for gut health in the long term. Fiber forms the bulk of our poop and without it, it can be hard to poop!

Tips for Being Healthy

One way to figure out whether a food is a junk food is to think about how processed it is. When we think of foods in their whole and original forms, like a fresh tomato, a grain of rice, or milk squeezed from a cow, we can then start to imagine how many steps are involved to transform that whole food into something that is ready-to-eat, tasty, convenient, and has a long shelf life.

For teenagers 13–14 years old, the recommended daily energy intake is 8,200–9,900 kJ/day or 1,960 kcal-2,370 kcal/day for boys and 7,400–8,200 kJ/day or 1,770–1,960 kcal for girls, according to the Australian dietary guidelines. Of course, the more physically active you are, the higher your energy needs. Remember that junk foods are okay to eat occasionally, but they should not make up more than 10% of your daily energy intake. In a day, this may be a simple treat such as a small muffin or a few squares of chocolate. On a weekly basis, this might mean no more than two fast-food meals per week. The remaining 90% of food eaten should be from the five food groups.

In conclusion, we know that junk foods are tasty, affordable, and convenient. This makes it hard to limit the amount of junk food we eat. However, if junk foods become a staple of our diets, there can be negative impacts on our health. We should aim for high-fiber foods such as whole grains, vegetables, and fruits; meals that have moderate amounts of sugar and salt; and calcium-rich and iron-rich foods. Healthy foods help to build strong bodies and brains. Limiting junk food intake can happen on an individual level, based on our food choices, or through government policies and health-promotion strategies. We need governments to stop junk food companies from advertising to young people, and we need their help to replace junk food restaurants with more healthy options. Researchers can focus on education and health promotion around healthy food options and can work with young people to develop solutions. If we all work together, we can help young people across the world to make food choices that will improve their short and long-term health.

Obesity : ↑ A disorder where too much body fat increases the risk of health problems.

Processed Food : ↑ A raw agricultural food that has undergone processes to be washed, ground, cleaned and/or cooked further.

Discretionary Food : ↑ Foods and drinks not necessary to provide the nutrients the body needs but that may add variety to a person’s diet (according to the Australian dietary guidelines).

Refined Sugar : ↑ Sugar that has been processed from raw sources such as sugar cane, sugar beets or corn.

Saturated Fat : ↑ A type of fat commonly eaten from animal sources such as beef, chicken and pork, which typically promotes the production of “bad” cholesterol in the body.

Dopamine : ↑ A hormone that is released when the brain is expecting a reward and is associated with activities that generate pleasure, such as eating or shopping.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. 4324.0.55.002 - Microdata: Australian Health Survey: Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2011-12 . Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online at: http://bit.ly/2jkRRZO (accessed December 13, 2019).

[2] ↑ National Health and Medical Research Council. 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines Summary . Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council.

[3] ↑ Potvin Kent, M., and Pauzé, E. 2018. The frequency and healthfulness of food and beverages advertised on adolescents’ preferred web sites in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health. 63:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.007

[4] ↑ Tan, L., Ng, S. H., Omar, A., and Karupaiah, T. 2018. What’s on YouTube? A case study on food and beverage advertising in videos targeted at children on social media. Child Obes. 14:280–90. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0037

[5] ↑ Gómez-Pinilla, F. 2008. Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 568–78. doi: 10.1038/nrn2421

[6] ↑ Attuquayefio, T., Stevenson, R. J., Oaten, M. J., and Francis, H. M. 2017. A four-day western-style dietary intervention causes reductions in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory and interoceptive sensitivity. PLoS ONE . 12:e0172645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172645

[7] ↑ Te Morenga, L., and Montez, J. 2017. Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 12:e0186672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186672

[8] ↑ Reichelt, A. C. 2016. Adolescent maturational transitions in the prefrontal cortex and dopamine signaling as a risk factor for the development of obesity and high fat/high sugar diet induced cognitive deficits. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00189

Essay on Junk Food

Students are often asked to write an essay on Junk Food in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Junk Food

The allure of junk food.

Junk food is popular for its taste, convenience, and affordability. It’s everywhere – in school cafeterias, at the cinema, and on our home tables.

The Downside of Junk Food

Healthy alternatives.

Instead of reaching for junk food, we should opt for healthier choices like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. These foods are not only tasty but also good for our health.

While junk food might be tempting, we must remember the importance of a balanced diet for our well-being.

250 Words Essay on Junk Food

Introduction.

Junk food, a term popularized in the latter half of the 20th century, refers to food that is high in calories but low in nutritional value. It is a pervasive element in modern societies, often associated with convenience, taste, and immediate gratification.

The appeal of junk food is multifaceted. It is typically easy to prepare, inexpensive, and designed to satisfy our innate preference for fat, sugar, and salt. Moreover, it’s often marketed with persuasive advertising strategies, making it an omnipresent temptation.

Nutritional Downfall

Despite its allure, junk food’s low nutritional value poses serious health risks. Its high sugar content can lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. High sodium levels can contribute to hypertension, and a dearth of essential nutrients can trigger a range of deficiencies.

Societal Impact

The ubiquity of junk food has significant societal implications. Its consumption is linked to a rise in chronic diseases, escalating healthcare costs, and decreased productivity. Moreover, it’s often more accessible in low-income communities, contributing to health disparities.

While junk food offers convenience and immediate satisfaction, its long-term effects on individual health and society are detrimental. It is crucial to promote healthier alternatives, regulate advertising, and improve nutritional education to mitigate these impacts. The challenge is not just a personal one, but a collective one that requires concerted effort and policy intervention.

500 Words Essay on Junk Food

Junk food’s popularity stems primarily from its convenience and addictive taste. Fast-paced modern lifestyles often leave little time for cooking or preparing nutritious meals. Junk food, easily accessible and ready-to-eat, fills this gap. Additionally, the high sugar, salt, and fat content in these foods stimulate the brain’s pleasure centers, creating a sense of satisfaction that encourages repeated consumption.

Nutritional Deficiencies

Despite their high calorie content, junk foods lack essential nutrients like vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Regular consumption of such foods can lead to nutritional deficiencies. For instance, a diet rich in junk food but devoid of fruits and vegetables can result in Vitamin C and fiber deficiencies, leading to health issues like scurvy and constipation respectively.

Health Implications

The role of marketing, addressing the issue.

Addressing the junk food epidemic requires a multi-faceted approach. Education about the harmful effects of junk food and the benefits of a balanced diet is crucial. Schools and colleges should promote healthier food choices in their cafeterias. Governments can play a role by implementing policies such as taxing junk food, restricting their advertising, and mandating clear nutritional labeling. Individuals also have a responsibility to make conscious choices about their diet and lifestyle.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Junk Food — People Should Eat Less Junk Food

People Should Eat Less Junk Food

- Categories: Dieting Junk Food

About this sample

Words: 475 |

Published: Jan 31, 2024

Words: 475 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Physical health, mental well-being, overall quality of life, counterargument and refutation.

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition - https://academic.oup.com/ajcn

- Nutritional Neuroscience - https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/iunu20/current

- World Health Organization - https://www.who.int

- National Institute on Drug Abuse - https://www.drugabuse.gov

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 823 words

2 pages / 1019 words

4 pages / 1793 words

2 pages / 775 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Junk Food

Cornelsen, L., Green, R., Dangour, A., & Smith, R. (2014). Why fat taxes won't make us thin. Journal of public health, 37(1), 18-23.Doshi, V. (2016, July 20).Tax on Junk food in Kerala leaves Indians with a bitter taste. The [...]

World Health Organization. (2018). Obesity and Overweight. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/may/16/fat-tax-unhealthy-food-effect

When it comes to the topic of junk food, there is a lot of debate and controversy. Some people argue that junk food should be avoided at all costs, while others believe that it is fine to indulge in moderation. In this [...]

Oliver, J. (2010, February). Teach every child about food. TED. Retrieved from Publishers.

Unhealthy eating is one of the most important health risk factors that can cause a range of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and other conditions linked to obesity. Unhealthy eating can add [...]

I have chosen unhealthy diet as the lifestyle behavior that affects my health directly. An unhealthy diet is defined as the consumption of “high levels of high-energy foods, such as processed foods that are high in fats and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Module: Academic Argument

Argumentative thesis statements.

Below are some of the key features of an argumentative thesis statement.

An argumentative thesis is . . .

An argumentative thesis must make a claim about which reasonable people can disagree. Statements of fact or areas of general agreement cannot be argumentative theses because few people disagree about them.

Junk food is bad for your health is not a debatable thesis. Most people would agree that junk food is bad for your health.

Because junk food is bad for your health, the size of sodas offered at fast-food restaurants should be regulated by the federal government is a debatable thesis. Reasonable people could agree or disagree with the statement.

An argumentative thesis takes a position, asserting the writer’s stance. Questions, vague statements, or quotations from others are not argumentative theses because they do not assert the writer’s viewpoint.

Federal immigration law is a tough issue about which many people disagree is not an arguable thesis because it does not assert a position.

Federal immigration enforcement law needs to be overhauled because it puts undue constraints on state and local police is an argumentative thesis because it asserts a position that immigration enforcement law needs to be changed.

An argumentative thesis must make a claim that is logical and possible. Claims that are outrageous or impossible are not argumentative theses.

City council members stink and should be thrown in jail is not an argumentative thesis. City council members’ ineffectiveness is not a reason to send them to jail.

City council members should be term limited to prevent one group or party from maintaining control indefinitely is an arguable thesis because term limits are possible, and shared political control is a reasonable goal.

Evidence Based

An argumentative thesis must be able to be supported by evidence. Claims that presuppose value systems, morals, or religious beliefs cannot be supported with evidence and therefore are not argumentative theses.

Individuals convicted of murder will go to hell when they die is not an argumentative thesis because its support rests on religious beliefs or values rather than evidence.

Rehabilitation programs for individuals serving life sentences should be funded because these programs reduce violence within prisons is an argumentative thesis because evidence such as case studies and statistics can be used to support it.

An argumentative thesis must be focused and narrow. A focused, narrow claim is clearer, more able to be supported with evidence, and more persuasive than a broad, general claim.

The federal government should overhaul the U.S. tax code is not an effective argumentative thesis because it is too general (What part of the government? Which tax codes? What sections of those tax codes?) and would require an overwhelming amount of evidence to be fully supported.

The U.S. House of Representative should vote to repeal the federal estate tax because the revenue generated by that tax is negligible is an effective argumentative thesis because it identifies a specific actor and action and can be fully supported with evidence about the amount of revenue the estate tax generates.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Argumentative Thesis Statements. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

Please wait while we process your request

Writing Essays About Fast Food

Academic writing

Essay paper writing

It is not a secret that the fast food sphere has come a long way from the convenience product cafe in the outskirts of Southern California to the multi-billion-dollar industry today. Since multiple studies show that cardiovascular and obesity problems of Americans in most cases are linked with overconsumption of foods filled with fats, salts, and carbs, careful exploration of the fast food market is highly demanded today. This demand inevitably brings every student to write essays about fast food. While this is quite a mouthwatering topic to write about, we should consider all the details for crafting an A+ essay. This article can be your guide in writing essays on fast food step by step.

Facts about the fast food industry are inexorable and striking. Let’s consider some of them:

- The highest death rates connected with junk food consumption and consequent weight-related complications have been reported in Nairobi, Kenya - that was nearly 2.8 million people each year.

- In more than 160,000 fast food locations in the US, more than 50 million Americans eat burgers daily.

- A third of children eat fast food on a daily basis.

- McDonald’s is more recognized than the Christian Cross.

We could continue with shocking facts and statistics even further, but what is crucial to understand that fortunately, the problem of eating too much junk meals is largely addressed by scholars from all around the world. As a result, multiple studies of recent years are available for you both on the Internet and in academic libraries. That might be exactly the reason why writing on this subject could be difficult, especially for students that are unfamiliar with professional essay writing. Why? Because it’s not that easy to gather all the overflow of the evidence and group it all into persuasive arguments, flowing through the pages of your academic assignment smoothly and in a scientifically correct way.

Whether you are writing a rationally constructed fast food argumentative essay or another type of paper requiring more opinion judgments, you should apply the same highly specific principles of academic writing. In addition to that, it’s also crucially important not to be too prejudiced about fast food. If you start your argument straight from the judgmental view of street meals as products that possess incontrovertible danger for human health, by doing this, you also start from the point of broken informational balance. Instead of taking the negative approach as an axiom, try to think like a scientist and explore any of fast food argumentative essay topics without the influence of your own point of view.

Nevertheless, fast food is a hot topic that might fuel some of the fiercest battles in your class, that’s why writing on this theme is especially interesting for a student of every faculty. So let’s get this show down the road and start our step by step guide of how to write an essay on what role does fast food play in our life and culture.

Fast food and obesity essay

The studies conducted at the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington clearly show that unhealthy eating habits are being the second biggest threat of early death worldwide, right next to the dangers of smoking. The risk factor here is a high body mass index, which signifies obesity and is a sign of increased cholesterol level. The high cholesterol level, high blood glucose level, along with high blood pressure, are all the consequences of obesity that is typically caused by regular consumption of fast food. Moreover, this problem also has an economic nature. This means that, when you are writing an unhealthy eating habits essay, it’s also useful to seek the roots of this issue in the economy field. By doing this, you will be able to propose a valid solution to the problem.

While we mentioned only one of the approaches above, when crafting your fast food and obesity essay, you could employ different techniques as far as your university professor considers it acceptable. Anyway, you need to start with the basics. First thing first, you have to find a proper topic. It is best if it will sound somewhat challenging and provocative because you have a chance to uncover the new approach and propose ideas that have never been addressed before by other students. Meanwhile, the general topic like a junk food and obesity essay could give you also more freedom in choosing the argument line, which you can shape after you perform extensive research on this theme. Some students come up with ideas for their titles after they do all the research and group their evidence by type and strength. While the other ones prefer to go with the flow, to apply their creativity and opinion right from the start by creating a compelling title in the first place, and then do all the most difficult parts. You can try both tactics and then choose whichever suits best for your pace, schedule, and style of writing.

Nevertheless, the research part is often being the key to crafting successful fast food is unhealthy essay. So what you do is begin to look for the evidence that supports the notion that any burger is a potential reason for one of five deaths in the world. Objectively speaking, eating one burger might not cause immediate and irreversible health problems. But the regular consumption of foods with low nutritional value, the high fat, calorie, and sodium content makes these meals potentially hazardous for health. As you can see now, whether writing an essay or a speech on fast food, it is crucial to employ an all-round approach to the exploration of this topic. This will help you sound rather professional than biased.

The good idea for your essay is to provide medical studies that prove the link between overconsumption of fast food and health as the first argument. You can find tons of information about this subject in scholarly articles on obesity and fast food from all around the world. For example, the Guardian research indicates that in 2011 alone, the number of people suffering from diabetes worldwide has increased nearly twice since 1980, and that was 153 million to 350 million people. This fact could be linked to junk foods available at any convenience store or shopping mall nearby, but this could be rather indirect evidence. Instead, it is much more relevant to look for specific studies on the topic that you are writing about.

Nevertheless, it is also worth noticing in a good persuasive essay on how fast food contributes to obesity about the hazards of obesity and the reason why we should talk about it more. According to recent studies, obesity rates have doubled in 2008 since 1980. The US, unfortunately, continues being an epicenter of this problem, where 2 of 3 Americans are clinically overweight. In addition to that, 500 million people were recorded in 2011 as obese with body mass indexes greater than 30, while 1.4 billion were clinically overweight with body mass indexes exceeding 25. A good opening phrase for effects of fast food essay could be based on the study that suggests that obesity kills more people than car crashes.

But if we return to specific studies about fast food and obesity relation, another research that you can highlight in your essay about junk food shows that fast food diminishes our basic instinct, which is the sensory-specific satiety. This instinct is responsible for feeling full after you eat your meal. You’ve probably noticed how soon you want to eat after visiting fast food restaurant. That’s the catch to mention in fast food essays. After experiments done on rats in e School of Medical Sciences at Australia’s University of New South Wales, it was proved that so-called junk food alters our brains’ motivational control and reward behavior. To put it simply, when someone stops eating traditional meals, they know when it’s enough. However, this trigger doesn’t work with fast food, which provokes overeating and results in health implications like mitochondrial dysfunction, weight gain, and tissue inflammation.

Finally, one of the studies shows that regular fast food consumption doubles the risk of insulin resistance being one of the reasons for the development of type 2 diabetes. They also point out that not only fast food affects obesity, including diabetes overweight, but also it increases cases of hospitalization with coronary diseases.

You could also mention in any of your future essays on junk food the marketing side of this problem. One of the reasons why people are overeating at fast food restaurants is the high number of them located in places where people usually work, live, and recreate. The Canadian Journal of Public Health researchers at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Ontario, Canada, published the results of their findings indicating that the density of fast food places increases the chances of eating too much junk food. Another research from the University of South Australia supported this information indicating in their European Journal of Epidemiology that in 2010, each 10% rise of the fast food locations resulted in 1.39 times more deaths from cardiovascular conditions. Similarly, the University of California, Berkeley, scholars found in 2009 that people living nearby fast food restaurants have a 5.2 percent greater risk of obesity.

In this regard, it is also valid to point out the reasons for eating too much fast food. Try to think about why people of different ages and backgrounds prefer eating at fast food diners rather than healthy food restaurants. Of course, one of the reasons for this is an attractive marketing image. First of all, eating something tasty is an essential part of how young people like to go out and socialize. In addition to that, specific chemicals and technology of production of junk food ingredients imply that they perform kind of a sensory attack to our receptors being enormously delicious, while also turning off the sensory satisfaction instinct and leaving us craving for more even when we are full. Make sure you don’t forget about this argument when writing an essay about what is really in fast food. Fast foods are also convenient for a variety of reasons for different people. Some of them don’t like cooking at home, so they go the easiest way and buy fast food. Also, people working in the office are also prone to eat at fast food restaurants. Such a meal is simply cheap, tasty, and convenient on the go.

Burgers and chips, chocolate bars and brightly colored candies, soda and ice-cream are also being an affordable treat for children from low-income families. It could appear as your central argument for a fast food and childhood obesity essay. Unfortunately, fast food is a highly desirable meal, especially for children. Various promotional offers and toy cartoon characters in the kit are another marketing trick that targets children to crave those burger menus. In many schools in the US, junk food is a part of the menu that any child can eat daily, which is also worth mentioning in a fast food in America essay. While in Mumbai, India, fast food is already totally prohibited for from selling in schools and next to their territories. We will talk more about this a couple sections below, so keep reading to know more about what you could write about the fast food industry with regard to the increasing worldwide childhood obesity rates of recent years.

Effects of fast food on health essay

In the section above, we have briefly touched upon the areas of research that could be relevant when writing the effects of fast food on health essay. The causation of regular fast food consumption is also strongly related to a wider variety of health issues. An essay on harmful effect of junk food is one of the most popular assignments to cover the topic of adverse effect of fast food on health. Even though the issue is rather serious, don’t overload it with negative assumptions and attempts to prove it in the most horrific way. Instead, keep things clear, reasonable, and rational. Try to dig into the roots and causes of the problem. Investigate the exact way of how fast food becomes hazardous for the health of children and adult people. You simply need to find that borderline that makes a tasty treat and turns it into a dangerous habit.

You may also alter the approach, creating something like eating at home vs eating out essay. Here, you have an opportunity to include all the pros and cons of healthier food, which one can easily cook at home. Moreover, this is also a good title for an argumentative essay because this type of academic assignment essentially needs to contain a counter-argument to your thesis statement, even if it’s quite common like a fast food kills argumentative essay. Further, you can examine things that stand in the way of cooking at home. For example, that could be the lack of knowledge of how to cook tasty and simple meals or the false assumption that home-cooked dinner is more expensive than eating out. People might also think that cooking at home takes a considerable amount of time.

Fast food and health problems have been widely discussed by academics from the leading universities around the world. Many famous dietologists also emphasize the incredible harm of junk food. While the most popular question to talk about is the threat of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems when writing the fast food and physical health essay, you also might want to mention that regular fast food consumption has proved to cause real brain damage and might even lead to a mental meltdown. The thing is that our brains just don’t get enough nutrients and vitamins with fast food, that’s why our bodies keep asking for more when being hungry shortly after you eat that French fries.

If you are writing the effects of consuming too much fast food essay, the great approach to choose to fascinate your professor and class is to go deeper into the chemistry of its ingredients. By carefully examining what fast food is made of and how nutrients work, you can find answers to your thesis statement proposed questions in order to resolve your argument and prove your point. You may look for ready answers as there are a lot of researches that have been performed to let people know what hides inside junk food. Meanwhile, it could also be much more interesting to propose your own ideas about the researched topic. As we already mentioned above, you may compare home-cooked meals with fast food in relation to its price, affordability, easiness, and the after-effects on the human body; this info will be especially relevant for a processed food essay. You might also explain how processed food is made, how to read nutrition labels, what foods are safe to buy, and what you should avoid. Your fast food informative speech will only benefit from that on the way to your A+ grade. Luckily, it is relatively easy to monitor what you eat thanks to the nutrition labels that fast food places and pre-packed food makers are obliged to make. You may enlist some especially dangerous elements so that the readers of your fast food warning labels essay will be aware of their harm.

The easiest way to know what you are buying is to read nutrition labels. A quick guide on them might be useful for you, but for shaping a persuasive essay about junk food, this information is obviously not enough. Our advice is to look for evidence to support your ideas in academic sources while also performing your own junk food research in restaurants and convenience stores. Due to the fact that the variety of food labels give too much specific information, try to start from simple steps. For example, you want to watch for a color-coding. To buy something healthier, look for more green ones (low fat, sugar, salt), than amber (medium fat, sugar, salt), or red (high amount of fat, sugar, salt). You also want to mention which amount of those ingredients plus energy (kJ/kcal), saturated fat carbohydrate, sugars, protein, and salt, is mentioned on the pack. These facts are great to explore in the essay on junk food a silent killer.

If too many students write about the current hazards of fast food relating to our physical health, and you don’t want to repeat the same ideas over and over again in one more essay, there is an alternative way to go. By choosing a slightly different topic, you can reserve yourself the highest grade of them all for sure. You will stand out from the crowd and be noticed by your professor. The only problem is that you will have to perform much more profound research to deliver your ideas in an academically proper way. So by now, you might be wondering, what are those mysterious alternative topics?

Well, for example, you can go for the history of fast food essay and examine the root cause of the whole problem that has got so globally large and important nowadays. How the burger culture went all the way from small and convenient products at the gas stations and suburbs diners to the leading worldwide industry that develops so well in almost every country? By watching its development, you might also propose the same approach for tackling the obesity problem. For instance, if promotion and smart marketing campaigns you consider as key factors to the overall fast food business success, then most likely, it is also the potentially most successful way to target the same audience and to promote healthier food choices.

However, if you want to go even further in your creativity, you may choose such a controversial topic as the benefits of fast food essay. Here, you will need to think out of the box. What benefits could have something so widely regarded as hazardous? Well, we have a few tips on what you could propose in such an essay. First of all, as we mentioned before, all food manufacturers and restaurants have calorie counts and nutrition labels on their foods. So in any renowned fast-food restaurant, you will get the portion that doesn’t exceed the recommended value of fats, sugars, salts, sodium, calories, etc. The good advice is just to eat one burger and say no to the second one in case if you want more.

Another benefit of fast food is that you can also pick healthier options in restaurants like the oatmeal for breakfast and the summer salad with grilled chicken for lunch. They also have a wide variety of affordable offers. You can try the best of Chinese, Mexican, Italian, and Middle-East food just for a few dollars.

Argumentative essay about junk food in schools

While fast food topic is quite popular today, still, writing an academic research paper, you shouldn’t let your emotions getting away with you. Your personal opinion and emotional approach are good for another kind of essay, which we will be talking about in the following sections. Meanwhile, it’s time to discuss what is so special about writing an argumentative essay about junk food in schools, and what you should do to make it the most appealing for a professor.

First and foremost, you should remember to maintain a rational approach to your subject. It is extremely important to keep the informational balance of both your arguments and counter-arguments; otherwise, it’s quite simple to get blown away by the most popular notion that fast food is simply unhealthy and then continue writing your essay based on that argument as an axiom that doesn’t need proving. However, simply a negative view of this topic cannot be considered the ultimate truth. When you are writing an academic assignment, you are acting as a scientist that explores the nature of things and makes their own conclusions on the basis of all the data and knowledge. All the info stated above might sound difficult at first, but when you look at this technique more closely, you will notice that performing this kind of research along with gathering the documentation as a proof of your assumptions from the trusted academic sources actually sounds like a very interesting way to work on an argumentative essay on fast food consumption.

When outlining your argumentative essay, you should also remember to put forth the strongest argument right in the first body paragraph. As you move on through your topic, keep uncovering the details about the ideas that you want to discuss in your paper, such as should junk food be banned in schools essay. According to the academic rules that define what an argumentative essay is, it should necessarily contain a tension of the argument. What do we mean by this? You can simply put together the opposing views right after another and discuss what evidence overweight the argument, thus making a point that proves your thesis statement. For example, the opposing view on the subject due to the previously stated example topic could be the essay about why schools should serve fast food options.

As you can clearly see now, here, you can explore both benefits and hazards of fast food being sold in schools. It would be extremely relevant to support your opinion on one or another argument by discussing the real examples. What happened to the schools that have already banned fast foods? Do they have statistics about the health of pupils learning in those schools? Do they run the promotional campaigns of encouraging kids to maintain a healthy diet, and if yes, do they work? See, here you can find a whole large field of investigation that is engaging and relevant for every student.

While writing about fast food selling in schools, it would also be valid to explore the topic in order to write children and fast food essay because particularly the younger generation is targeted by global brands marketing campaigns of junk food. The famous TV presenter, blogger, and cook Jamie Oliver runs a whole social media campaign against that tendency, which is called #IAdEnough, which you might also want to mention in your paper. It’s important to mention, though, that Jamie Oliver doesn’t argue against fast food promotional campaigns in general; he only insists that they should not be targeted at children and teenagers since they are more vulnerable and prone to copying the behavior shown in the advertisement.

Having said that, your thesis statement of a good argumentative essay could also focus on the questions that you could explore in an essay on effects of fast food on our new generation. Picture the societal advantages and challenges of our times and how they affect the choice of food for the younger audience. Of course, the global development of pocket-size smart devices, the Internet, and social media affects modern culture greatly. The overflow of various unfiltered information going through all of these sources makes it even harder for modern kids to make conscious decisions about what they want and what they really need.

When looking at all these social tendencies globally, you may shape the argument of essay writing on fast food towards finding the root cause for the problem of the overly high popularity of fast food in the market of the younger generation. You might also propose solutions to this problem. For example, why not making healthy food also cheap and quick to cook, as well as incredibly tasty and visually appealing?

Research paper on fast food

While an argumentative essay on any topic requires putting together two opposing points of view and make your own reasonable conclusions as a result of that exploration and comparison, when you are writing a research paper on fast food, you want to apply a slightly different approach. The main point to remember here is that the research paper doesn’t concentrate on the single one point of an argument, nor does it consider only one polarity view to be ultimately outweighing another. When writing this kind of an academic assignment, you want to focus on analyzing the problem that you pose in your thesis statement from various points of view, considering different facts and evidence along the way. The aim of the research paper is rather rationalizing on a particular subject than trying to convince or to discern certain ideas.

The first thing that you need to do while working on a fast food and obesity research paper is to carefully gather all the possible references on your topic that you can find. We know it is the most comfortable to look for them online, but at the same time, try to do something that’ll make you stand out of the crowd. For example, go to your university or public library. You will be surprised how much useful information is presented in the sources you find there.

However, if you are still looking for some fast food research paper topics, it is not necessarily to look among research papers that you see all around on the Internet. In order to sound original, try to look for scientific articles on fast food, as well as some popular media resources that cover the topic of junk food consumption effects. Often, these articles contain a lot of useful information given in quite a short form. When you know all the thesis sentences and claims that it covers, you can note them and then develop these ideas and use the given data throughout your research paper.

After you have collected all the data that will support your train of thought, you need to organize your facts and quotes by certain criteria. You decide what criteria will be the most significant for you. Anyway, it should reveal the idea of your thesis statement. You could also make notes along the way that will appear useful when you will write the body paragraphs. After you’ve done all that, it’s time to plan and write down the fast food research paper outline. This could be a simple topic phrase outline or a more advanced annotated outline with whole topic sentences. Whether you should choose the first or the second one, it depends on your academic level and requirements of the teacher.

Research essay about fast food

Another kind of academic assignment that you might be asked to write is a research essay about fast food. You might be wondering how this is different from all the other kinds of academic papers. Well, the specific requirements really differ from one university, college, or school to another. To know exactly what rules and norms of formatting, what style and scientific approach you should abide by, ask your professor. And of course, don’t forget to visit lectures on a regular basis.

Moreover, a research essay is different from, for example, a persuasive essay on why fast food is bad in the way that you want to prove and explain your thesis statement. In the first case, you perform extensive research of various credible sources on your topic and then analyze it in a rational and logical kind of way. Of course, all these principles you also apply in your persuasive essay about fast food, but that is slightly different. In the last case, you apply more of the emotional and moral evidence. Persuasive essays are pushier; they are designed to convince your audience to agree with your point of view on the subject that you are talking about.

Persuasive essays that require less of a logical approach and designed to assess mostly your ability for critical thinking are also called something like the opinion essay about fast food. When writing this, don’t forget that you shouldn’t be blown away by your emotions. Your ideas also shouldn’t be left without the support of relevant references in case you have a more advanced academic level. Yes, this is all about your opinion, but it also suggests that you have carefully researched the given topic before writing about it and not just reflected on something you know little or nothing about. The same goes for the fast food discussion essay. Here, you want to discuss various, often controversial points of view on the given subject, not relying much on your personal opinion.

Fast food essay outline

In order to get the best grade, you might start your work on the essay, looking for the catchy essay titles for the topic of the popularity of fast food restaurants. However, this approach might not always be the best idea to employ for writing an academic assignment. First off, what the excellent student really wants is crafting a relevant, strong, and persuasive fast food thesis statement that will lead them all along the way of writing the paper. A perfectly posed question can do miracles with your assignment. It will be so easy to write down paragraph by paragraph if you know for sure how you are going to deploy your topic.

You might not want to spend some considerable amount of time on shaping the perfect thesis statement, but you got to trust us, it’s definitely worth the hassle. Don’t be afraid to alter it on the way, for example, as you do your research, you get to know more and more important data and evidence about the subject. When you feel that you’ve done all these things right, it’s time to move on to the next step. And that is writing the fast food essay outline. You may be wondering how the perfect outline actually looks like. If you type in the search engine of your browser when starting to work on your fast food argumentative essay sample, the sample essays that you find might contain some advanced and long outlines. It looks professional, maybe even too much. Your task is creating a short and concise outline that can be accepted by your professor.

However, even the outline doesn’t have as much influence on your eventual grade as the fast food essay introduction. This part is the first page or two that the professor will read, and of course, he or she will memorize it the most at the end of the day when going through dozens of similar essays like yours. It may also be the main reference point if you have to stand out in front of the class and defend your point discussed in your essay. By the way, one more tip for you: competitive and engaging fast food essay hook makes the perfect introduction. It might take some time to think about mainly because the topic of junk food is largely addressed.

To find a perfectly new and fresh attention grabber for essays on effects of fast food persuasive essay, we recommend you look up the popular social activists and bloggers forums, websites, and groups in social media. This might not be the most reliable source of information to state in a reference page, but you need it for other reasons. Namely, for finding the newest and the most accurate information to hook the audience of your fast food persuasive essay. For example, one of the recent blog posts of the healthy diet community claimed that obesity kills more people annually than dictators and political regimes in the times of World War II. Does it sound shocking and attention-grabbing? For sure! And that is exactly what you are looking for when thinking how to write a persuasive essay introduction on fast food linked to obesity. After you have found this perfectly challenging hook statement and shaped your thesis statement in the proper way, don’t rush to finish your introduction right away. Wait for a few hours and even days so you can go back to it with fresh ideas and maybe alter it to perfection.

What is no less important for a good essay grade apart from the introduction is also a conclusion for a fast food essay. The first thing that you need to remember is that rephrasing all the arguments from your essay is not simply rewriting it. Strive for pointing out all the major turning points while thinking of your thesis statement as a proven fact. Thus, your conclusion will sound strong and persuasive. The next thing that you definitely want to do is finish your essay with a persuasive clincher phrase that encourages the further exploration of your essay topic.

Fast food essay topics

Given that writing about fast food consumption and its long-term effects on human health became a common thing to do for students at most of the universities across the world, it is fair to say that most of these essays include almost the same information. The facts about the link between fast-food restaurants density and health issues of people living nearby, the consequences of overconsumption of trans fats, sodium, and salts in fast food - all these data and statistics are surely known by your professors since they might have read it thousand times before. So, what should you do to really stand out and to gain the best grade in your class? We have the right answer! What you need to think of in the first place is picking some fresh and new topics for fast food essay. Do you think that there is not much place for creativity? We will prove to you in this section that there are lots of areas in the fast-food exploration field that haven’t been largely discussed by the scholar audience.

As we already mentioned in the previous sections, a good way in which you could start your exploration is the essay about how fast food places use kids to market their brand. Indeed, this is a global problem that requires spreading the carefully researched data and academic knowledge. As a result, you might contribute to the healthier development of our younger generations. Just think about all those toys in the food kits and children menu options in the fast-food restaurants that you know. The imagery that they use are is highly appealing to the younger audience. Meanwhile, due to the tremendous amounts of information that appears online and in advertising (oftentimes hidden in social media context), the unfiltered advertising portions process through our brains without much resistance. We almost subconsciously assume, without even giving it a second thought or doubt that a highly sweetened carbonated beverage is associated with happiness while chilling with your friends and family. We associate burgers with socializing and having a good time. Thus, the advertising is targeted directly at young and unprotected by media literacy and awareness minds.

The next paper you may want to work on is the causes and effects of the popularity of fast food restaurants essay. Here, you should employ a classic academic structure of the paper that requires a binary approach, i.e., you have to look both at causes of this problem and its direct consequences, also known as effects. In this regard, you should watch carefully to maintain a perfectly logical order and reasoning. To be completely sure about the links between certain facts and data and your comments on its consequences, look through the list of the most common logical fallacies in order to stay away from things like wrong reasoning or the ‘straw man’ effect. The cause and effect essay can have a few different kinds of structure to begin with. The first and most common type is the chain of causes and effects. In cases when you are working on one little write-up like an addiction to fast food essay, you can use only one to three causes and effects. For example, the regular habit of eating out causes the risk of obesity. The chain of causes and effects would look like a more expanded view of this general cause and effect link: the regular consumption of fast food delivers too many calories and too little nutrition, which causes an unsatisfied desire to eat more, and overeating, in its turn, provokes bad digestion and obesity as a result of it. That would be the chain of causes and effects.

The next type of causation and consequences linkage could also be deployed in a why is fast food bad for us and we keep going back essay. You could have a structure like this. Either there could be one cause and many effects, or it could be many causes that lead to one effect. Basically, here you can find a lot of similar features with the induction and deduction processes. If talking about examples, regular eating out at fast-food restaurants could be the one cause that provokes many long-term effects associated with health risks like obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and so on. Don’t forget to keep an eye on the latest researches in this field to possess the newest information that hasn’t been disproved by scholars recently.

The next structure that we are going to talk about is many causes that lead to one effect. For example, you are writing a should fast food be served with warning labels essay. You can include here many causes that lead to the overconsumption of fast food. That could be the lack of attention to the nutrition labels, the lack of knowledge about what those labels mean or how to count your daily calories, and which amount could be considered the optimal if thinking individually. There are many causes why we don’t care about what is written on those labels. There is also a number of reasons why they could be considered ineffective for reducing the health risks linked with fast food consumption. The labels might contain deceptive or improperly stated information, or they could be confused with advertising labels (like low-calorie, eco, natural, no gluten labels that potentially hide lots of sugars and other chemicals in the same product).

You can also go in the opposite direction in your research. Instead of focusing on the fast food hazards, explore why it became so popular and why so many people from various societal groups prefer eating fast food over other healthier options at full-serving restaurants. This could be examined in a convenience of fast food essay. Similarly, you can also explore both short-term and long-term consequences that the fast-food culture has for people of your country or in the world. You can also discuss the medical and health issues as a direct consequence of the regular fast food consumption and think about how the fast-food culture affects people regarding other social spheres in the effects fast food has on society essay.

Another interesting field for exploration is a comparison of opposing phenomena. They are easy to find in a topic that you are currently working on. Fast food is largely regarded as the opposite of a healthy diet. It is also being polarized to homemade meals. You could discuss the relations between one or a few of these opposing subjects in the fast food vs home cooked meals contrast and comparison essay. Just remember not to paint the fast food all black because this contrast could not be as obvious as you could think at first. For instance, I personally know a few families that cooked their meals only at home. They had lots of fried foods with an enormous amount of fats and carcinogens. Of course, as a result, all the family had an obesity problem, high blood pressure, and heart diseases.

Since the consumption of fast food has a huge impact on society in general, many students and professors tend to look at it from a political point of view. They try to assume and explore whether it would be effective to solve the problem on a governmental level. As a result, questions like the tax regulation of fast-food brands often arise these days. If you like to think of politics, you could pick a “should the government regulate fast food” essay topic. Remember to maintain a balanced approach and to discuss opposing points of view with a rational critical thinking attitude. It would be easier, if you know how to write a critical thinking essay. For example, you may tell about soda tax, which is a tax designed to reduce the consumption of drinks with added sugar. This tax became a matter of public debate in many countries, and beverage producers like Coca-Cola often oppose it.

Often, if you write a persuasive essay, you would be interested in what are people talking about fast food in advertising, political speeches, editorials, newspapers, forums, and blogs. This is exactly the reason why professors and teachers choose contemporary topics for you to discuss, like the dark side of fast food essay. To write this kind of a persuasive essay the best way possible, try to think of yourself as a journalist or a lawyer that fights for a certain opinion to be widely considered. Pick the side you wish to advocate and stand for at all means. The next essential thing to know is your audience. Are they opposing your viewpoint, inclined to favor your side, or still undecided? Depending on that, you would structure your essay.

We could talk for hours about the various ideas for fast food essay topics, but your creativity could do this job even better. The most important thing to do when writing an academic essay is to show your personal approach to the topic and the ability to think critically. Of course, your essay should be adjusted to all the rules and norms of the university formatting, but that is not the main thing that professors usually assess when deciding on what grade to give to some particular essay writing.

So now you know how to approach such a broad and burning topic. We really hope that with the help of our guidelines, you will get the best mark possible. Good luck!

Your email address will not be published / Required fields are marked *

Try it now!

Calculate your price

Number of pages:

Order an essay!

Fill out the order form

Make a secure payment

Receive your order by email

Writing About LGBTQ Rights

Violation of the rights of sexual minorities is an acute problem in modern society. That is why LGBT essay topics are getting more and more popular nowadays. The issue is that some conservative…

20th Jan 2020

Definition Essay Topics

A definition essay is one of the most popular assignments in schools and universities, and the majority of students have definitely written such a paper. Even though it seems easy at first, you have…

7th Sep 2018

Multiple-Choice Questions Writing

Sometimes, time is all we have, and along with that, time is all we don't have. Time is the relentless foe and the judge that values our deeds. This expression is especially true when you are…

9th Nov 2016

Get your project done perfectly

Professional writing service

Reset password

We’ve sent you an email containing a link that will allow you to reset your password for the next 24 hours.

Please check your spam folder if the email doesn’t appear within a few minutes.

Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Every person in the world has to make daily decisions about what they eat. These decisions are based on various factors, including food’s availability, convenience, and taste – and, evidently, its cost. According to Salads Square (2021), it was estimated that, for one person, eating healthily costs approximately $1.5 a day more than eating unhealthily. Savoie-Roskos et al. (n.d.) note that, as a result, people choose less nutritious foods in an attempt to save money. In order to persuade the audience that a solution to this problem is the change of prices to make healthy food more affordable, a problem-cause-solution approach will be used. As per this approach, first, a problem is established; then, the causes of this problem are discussed; after that, a solution is offered.

The problem has been stated, and now it is time to turn to its causes. According to Elementum (2018), to understand the costs of healthy foods, one is to pay attention to the food supply chain. First of all, processed and packaged foods are more efficient in production. Secondly, the transportation of fresh produce is quite expensive since it requires continual refrigeration to prevent spoilage. Thirdly, many organic foods are to be separated from conventional ones in storage, which applies to all supply chain links. Finally, since demand for fresh and organic foods is generally lower, companies cannot do bulk deliveries to reduce logistics costs. When combined together, all of this increases the costs of final products.

When it comes to the solution to this problem, one of the policies that can be implemented is that of competitive pricing. According to County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (2021), competitive pricing is the assignation of higher costs for foods and beverages deemed non-nutritious. This policy includes price discounts, incentives for healthy products, and price increases and disincentives for unhealthy ones. Preliminary data on such interventions indicates that a 1% reduction in prices is connected to more than a 1% increase in required quantities of healthy foods (County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2021). To enhance this effect, Pennington Biomedical Research Center (n.d.) suggests providing incentives to store owners, schools, and sport complexes so that they promote healthier snack and beverages options. Since there is no way to affect the cost of organic foods via the food supply chain, it is the government’s mission to ensure that its people are healthy by implementing such policies.

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (2021). Competitive pricing for healthy foods .

Elementum. (2018). Why does eating healthier cost more? Medium.

Pennington Biomedical Research Center. (n.d.). Junk food relative pricing [PDF file]. Web.

Salads Square (2021). Why is healthy food so expensive compared to junk food?

Savoie-Roskos, M. R., Jorgensen, M. A., & Durward, C. (n.d.). Does healthy eating cost more? Utah State University.

- Healthy Nutrition: Case Study of Malnutrition

- "The Game Changers" Movie Reflection

- Literacy Environment for Young Learners

- Patient Falls and Federal Agencies’ Initiatives

- Cosmetic Surgery: Dangers and Alternatives

- Aspects of Food and Nutrition Myths

- Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in Food Production

- Diet Quality and Late Childhood Development

- Wellness: Physical Activity and Healthy Nutrition

- Very-Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet and Kidney Failure

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, March 30). Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-junk-food-should-cost-more-than-healthy-food/

"Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food." IvyPanda , 30 Mar. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/why-junk-food-should-cost-more-than-healthy-food/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food'. 30 March.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food." March 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-junk-food-should-cost-more-than-healthy-food/.

1. IvyPanda . "Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food." March 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-junk-food-should-cost-more-than-healthy-food/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Why Junk Food Should Cost More Than Healthy Food." March 30, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-junk-food-should-cost-more-than-healthy-food/.

Harmful Effects of Junk Food Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on harmful effects of junk food.

Junk Food is very harmful that is slowly eating away the health of the present generation. The term itself denotes how dangerous it is for our bodies. Most importantly, it tastes so good that people consume it on a daily basis. However, not much awareness is spread about the harmful effects of junk food.

The problem is more serious than you think. Various studies show that junk food impacts our health negatively. They contain higher levels of calories, fats, and sugar. On the contrary, they have very low amounts of healthy nutrients and lack dietary fibers. Parents must discourage their children from consuming junk food because of the ill effects it has on one’s health.

Impact of Junk Food