- Open access

- Published: 17 February 2022

Effectiveness of problem-based learning methodology in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review

- Joan Carles Trullàs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7380-3475 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Carles Blay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3962-5887 1 , 4 ,

- Elisabet Sarri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2435-399X 3 &

- Ramon Pujol ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2527-385X 1

BMC Medical Education volume 22 , Article number: 104 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

88 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that shifts the role of the teacher to the student (student-centered) and is based on self-directed learning. Although PBL has been adopted in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education, the effectiveness of the method is still under discussion. The author’s purpose was to appraise available international evidence concerning to the effectiveness and usefulness of PBL methodology in undergraduate medical teaching programs.

The authors applied the Arksey and O’Malley framework to undertake a scoping review. The search was carried out in February 2021 in PubMed and Web of Science including all publications in English and Spanish with no limits on publication date, study design or country of origin.

The literature search identified one hundred and twenty-four publications eligible for this review. Despite the fact that this review included many studies, their design was heterogeneous and only a few provided a high scientific evidence methodology (randomized design and/or systematic reviews with meta-analysis). Furthermore, most were single-center experiences with small sample size and there were no large multi-center studies. PBL methodology obtained a high level of satisfaction, especially among students. It was more effective than other more traditional (or lecture-based methods) at improving social and communication skills, problem-solving and self-learning skills. Knowledge retention and academic performance weren’t worse (and in many studies were better) than with traditional methods. PBL was not universally widespread, probably because requires greater human resources and continuous training for its implementation.

PBL is an effective and satisfactory methodology for medical education. It is likely that through PBL medical students will not only acquire knowledge but also other competencies that are needed in medical professionalism.

Peer Review reports

There has always been enormous interest in identifying the best learning methods. In the mid-twentieth century, US educator Edgar Dale proposed which actions would lead to deeper learning than others and published the well-known (and at the same time controversial) “Cone of Experience or Cone of Dale”. At the apex of the cone are oral representations (verbal descriptions, written descriptions, etc.) and at the base is direct experience (based on a person carrying out the activity that they aim to learn), which represents the greatest depth of our learning. In other words, each level of the cone corresponds to various learning methods. At the base are the most effective, participative methods (what we do and what we say) and at the apex are the least effective, abstract methods (what we read and what we hear) [ 1 ]. In 1990, psychologist George Miller proposed a framework pyramid to assess clinical competence. At the lowest level of the pyramid is knowledge (knows), followed by the competence (knows how), execution (shows how) and finally the action (does) [ 2 ]. Both Miller’s pyramid and Dale’s cone propose a very efficient way of training and, at the same time, of evaluation. Miller suggested that the learning curve passes through various levels, from the acquisition of theoretical knowledge to knowing how to put this knowledge into practice and demonstrate it. Dale stated that to remember a high percentage of the acquired knowledge, a theatrical representation should be carried out or real experiences should be simulated. It is difficult to situate methodologies such as problem-based learning (PBL), case-based learning (CBL) and team-based learning (TBL) in the context of these learning frameworks.

In the last 50 years, various university education models have emerged and have attempted to reconcile teaching with learning, according to the principle that students should lead their own learning process. Perhaps one of the most successful models is PBL that came out of the English-speaking environment. There are many descriptions of PBL in the literature, but in practice there is great variability in what people understand by this methodology. The original conception of PBL as an educational strategy in medicine was initiated at McMaster University (Canada) in 1969, leaving aside the traditional methodology (which is often based on lectures) and introducing student-centered learning. The new formulation of medical education proposed by McMaster did not separate the basic sciences from the clinical sciences, and partially abandoned theoretical classes, which were taught after the presentation of the problem. In its original version, PBL is a methodology in which the starting point is a problem or a problematic situation. The situation enables students to develop a hypothesis and identify learning needs so that they can better understand the problem and meet the established learning objectives [ 3 , 4 ]. PBL is taught using small groups (usually around 8–10 students) with a tutor. The aim of the group sessions is to identify a problem or scenario, define the key concepts identified, brainstorm ideas and discuss key learning objectives, research these and share this information with each other at subsequent sessions. Tutors are used to guide students, so they stay on track with the learning objectives of the task. Contemporary medical education also employs other small group learning methods including CBL and TBL. Characteristics common to the pedagogy of both CBL and TBL include the use of an authentic clinical case, active small-group learning, activation of existing knowledge and application of newly acquired knowledge. In CBL students are encouraged to engage in peer learning and apply new knowledge to these authentic clinical problems under the guidance of a facilitator. CBL encourages a structured and critical approach to clinical problem-solving, and, in contrast to PBL, is designed to allow the facilitator to correct and redirect students [ 5 ]. On the other hand, TBL offers a student-centered, instructional approach for large classes of students who are divided into small teams of typically five to seven students to solve clinically relevant problems. The overall similarities between PBL and TBL relate to the use of professionally relevant problems and small group learning, while the main difference relates to one teacher facilitating interactions between multiple self-managed teams in TBL, whereas each small group in PBL is facilitated by one teacher. Further differences are related to mandatory pre-reading assignments in TBL, testing of prior knowledge in TBL and activating prior knowledge in PBL, teacher-initiated clarifying of concepts that students struggled with in TBL versus students-generated issues that need further study in PBL, inter-team discussions in TBL and structured feedback and problems with related questions in TBL [ 6 ].

In the present study we have focused on PBL methodology, and, as attractive as the method may seem, we should consider whether it is really useful and effective as a learning method. Although PBL has been adopted in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education, the effectiveness (in terms of academic performance and/or skill improvement) of the method is still under discussion. This is due partly to the methodological difficulty in comparing PBL with traditional curricula based on lectures. To our knowledge, there is no systematic scoping review in the literature that has analyzed these aspects.

The main motivation for carrying out this research and writing this article was scientific but also professional interest. We believe that reviewing the state of the art of this methodology once it was already underway in our young Faculty of Medicine, could allow us to know if we were on the right track and if we should implement changes in the training of future doctors.

The primary goal of this study was to appraise available international evidence concerning to the effectiveness and usefulness of PBL methodology in undergraduate medical teaching programs. As the intention was to synthesize the scattered evidence available, the option was to conduct a scoping review. A scoping study tends to address broader topics where many different study designs might be applicable. Scoping studies may be particularly relevant to disciplines, such as medical education, in which the paucity of randomized controlled trials makes it difficult for researchers to undertake systematic reviews [ 7 , 8 ]. Even though the scoping review methodology is not widely used in medical education, it is well established for synthesizing heterogeneous research evidence [ 9 ].

The specific aims were: 1) to determine the effectiveness of PBL in academic performance (learning and retention of knowledge) in medical education; 2) to determine the effectiveness of PBL in other skills (social and communication skills, problem solving or self-learning) in medical education; 3) to know the level of satisfaction perceived by the medical students (and/or tutors) when they are taught with the PBL methodology (or when they teach in case of tutors).

This review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews. The five main stages of the framework are: (1) identifying the research question; (2) ascertaining relevant studies; (3) determining study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results [ 7 ]. We reported our process according to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews [ 10 ].

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

With the goals of the study established, the four members of the research team established the research questions. The primary research question was “What is the effectiveness of PBL methodology for learning in undergraduate medicine?” and the secondary question “What is the perception and satisfaction of medical students and tutors in relation to PBL methodology?”.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

After the research questions and a search strategy were defined, the searches were conducted in PubMed and Web of Science using the MeSH terms “problem-based learning” and “Medicine” (the Boolean operator “AND” was applied to the search terms). No limits were set on language, publication date, study design or country of origin. The search was carried out on 14th February 2021. Citations were uploaded to the reference manager software Mendeley Desktop (version 1.19.8) for title and abstract screening, and data characterization.

Stage 3: Study selection

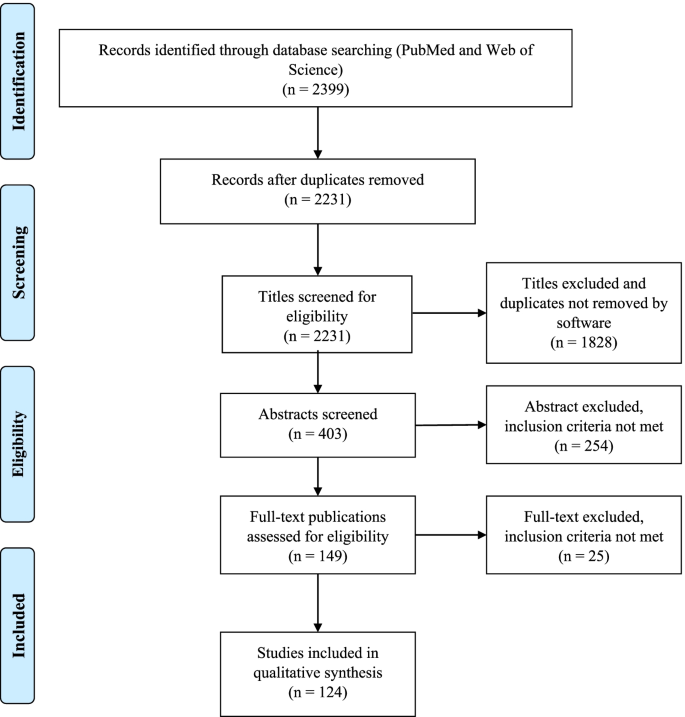

The searching strategy in our scoping study generated a total of 2399 references. The literature search and screening of title, abstract and full text for suitability was performed independently by one author (JCT) based on predetermined inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: 1) PBL methodology was the major research topic; 2) participants were undergraduate medical students or tutors; 3) the main outcome was academic performance (learning and knowledge retention); 4) the secondary outcomes were one of the following: social and communication skills, problem solving or self-learning and/or student/tutor satisfaction; 5) all types of studies were included including descriptive papers, qualitative, quantitative and mixed studies methods, perspectives, opinion, commentary pieces and editorials. Exclusion criteria were studies including other types of participants such as postgraduate medical students, residents and other health non-medical specialties such as pharmacy, veterinary, dentistry or nursing. Studies published in languages other than Spanish and English were also excluded. Situations in which uncertainty arose, all authors (CB, ES, RP) discussed the publication together to reach a final consensus. The outcomes of the search results and screening are presented in Fig. 1 . One-hundred and twenty-four articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis.

Study flow PRISMA diagram. Details the review process through the different stages of the review; includes the number of records identified, included and excluded

Stage 4: Charting the data

A data extraction table was developed by the research team. Data extracted from each of the 124 publications included general publication details (year, author, and country), sample size, study population, design/methodology, main and secondary outcomes and relevant results and/or conclusions. We compiled all data into a single spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel for coding and analysis. The characteristics and the study subject of the 124 articles included in this review are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 . The detailed results of the Microsoft Excel file is also available in Additional file 1 .

Stage 5: Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

As indicated in the search strategy (Fig. 1 ) this review resulted in the inclusion of 124 publications. Publication years of the final sample ranged from 1990 to 2020, the majority of the publications (51, 41%) were identified for the years 2010–2020 and the years in which there were more publications were 2001, 2009 and 2015. Countries from the six continents were represented in this review. Most of the publications were from Asia (especially China and Saudi Arabia) and North America followed by Europe, and few studies were from Africa, Oceania and South America. The country with more publications was the United States of America ( n = 27). The most frequent designs of the selected studies were surveys or questionnaires ( n = 45) and comparative studies ( n = 48, only 16 were randomized) with traditional or lecture-based learning methodologies (in two studies the comparison was with simulation) and the most frequently measured outcomes were academic performance followed by student satisfaction (48 studies measured more than one outcome). The few studies with the highest level of scientific evidence (systematic review and meta-analysis and randomized studies) were conducted mostly in Asian countries (Tables 1 and 2 ). The study subject was specified in 81 publications finding a high variability but at the same time great representability of almost all disciplines of the medical studies.

The sample size was available in 99 publications and the median [range] of the participants was 132 [14–2061]. According to study population, there were more participants in the students’ focused studies (median 134 and range 16–2061) in comparison with the tutors’ studies (median 53 and range 14–494).

Finally, after reviewing in detail the measured outcomes (main and secondary) according to the study design (Table 2 and Additional file 1 ) we present a narrative overview and a synthesis of the main findings.

Main outcome: academic performance (learning and knowledge retention)

Seventy-one of the 124 publications had learning and/or knowledge retention as a measured outcome, most of them ( n = 45) were comparative studies with traditional or lecture-based learning and 16 were randomized. These studies were varied in their methodology, were performed in different geographic zones, and normally analyzed the experience of just one education center. Most studies ( n = 49) reported superiority of PBL in learning and knowledge acquisition [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 ] but there was no difference between traditional and PBL curriculums in another 19 studies [ 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 ]. Only three studies reported that PBL was less effective [ 79 , 80 , 81 ], two of them were randomized (in one case favoring simulation-based learning [ 80 ] and another favoring lectures [ 81 ]) and the remaining study was based on tutors’ opinion rather than real academic performance [ 79 ]. It is noteworthy that the four systematic reviews and meta-analysis included in this scoping review, all carried out in China, found that PBL was more effective than lecture-based learning in improving knowledge and other skills (clinical, problem-solving, self-learning and collaborative) [ 40 , 51 , 53 , 58 ]. Another relevant example of the superiority of the PBL method over the traditional method is the experience reported by Hoffman et al. from the University of Missouri-Columbia. The authors analyzed the impact of implementing the PBL methodology in its Faculty of Medicine and revealed an improvement in the academic results that lasted for over a decade [ 31 ].

Secondary outcomes

Social and communication skills.

We found five studies in this scoping review that focused on these outcomes and all of them described that a curriculum centered on PBL seems to instill more confidence in social and communication skills among students. Students perceived PBL positively for teamwork, communication skills and interpersonal relations [ 44 , 45 , 67 , 75 , 82 ].

Student satisfaction

Sixty publications analyzed student satisfaction with PBL methodology. The most frequent methodology were surveys or questionnaires (30 studies) followed by comparative studies with traditional or lecture-based methodology (19 studies, 7 of them were randomized). Almost all the studies (51) have shown that PBL is generally well-received [ 11 , 13 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 29 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 46 , 50 , 56 , 58 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 78 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 ] but in 9 studies the overall satisfaction scores for the PBL program were neutral [ 76 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 ] or negative [ 117 , 118 ]. Some factors that have been identified as key components for PBL to be successful include: a small group size, the use of scenarios of realistic cases and good management of group dynamics. Despite a mostly positive assessment of the PBL methodology by the students, there were some negative aspects that could be criticized or improved. These include unclear communication of the learning methodology, objectives and assessment method; bad management and organization of the sessions; tutors having little experience of the method; and a lack of standardization in the implementation of the method by the tutors.

Tutor satisfaction

There are only 15 publications that analyze the satisfaction of tutors, most of them surveys or questionnaires [ 85 , 88 , 92 , 98 , 108 , 110 , 119 ]. In comparison with the satisfaction of the students, here the results are more neutral [ 112 , 113 , 115 , 120 , 121 ] and even unfavorable to the PBL methodology in two publications [ 117 , 122 ]. PBL teaching was favored by tutors when the institutions train them in the subject, when there was administrative support and adequate infrastructure and coordination [ 123 ]. In some experiences, the PBL modules created an unacceptable toll of anxiety, unhappiness and strained relations.

Other skills (problem solving and self-learning)

The effectiveness of the PBL methodology has also been explored in other outcomes such as the ability to solve problems and to self-directed learning. All studies have shown that PBL is more effective than lecture-based learning in problem-solving and self-learning skills [ 18 , 24 , 40 , 48 , 67 , 75 , 93 , 104 , 124 ]. One single study found a poor accuracy of the students’ self-assessment when compared to their own performance [ 125 ]. In addition, there are studies that support PBL methodology for integration between basic and clinical sciences [ 126 ].

Finally, other publications have reported the experience of some faculties in the implementation of the PBL methodology. Different experiences have demonstrated that it is both possible and feasible to shift from a traditional curriculum to a PBL program, recognizing that PBL methodology is complex to plan and structure, needs a large number of human and material resources, requiring an immense teacher effort [ 28 , 31 , 94 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 ]. In addition, and despite its cost implication, a PBL curriculum can be successfully implemented in resource-constrained settings [ 134 , 135 ].

We conducted this scoping review to explore the effectiveness and satisfaction of PBL methodology for teaching in undergraduate medicine and, to our knowledge, it is the only study of its kind (systematic scoping review) that has been carried out in the last years. Similarly, Vernon et al. conducted a meta-analysis of articles published between 1970 and 1992 and their results generally supported the superiority of the PBL approach over more traditional methods of medical education [ 136 ]. PBL methodology is implemented in medical studies on the six continents but there is more experience (or at least more publications) from Asian countries and North America. Despite its apparent difficulties on implementation, a PBL curriculum can be successfully implemented in resource-constrained settings [ 134 , 135 ]. Although it is true that the few studies with the highest level of scientific evidence (randomized studies and meta-analysis) were carried out mainly in Asian countries (and some in North America and Europe), there were no significant differences in the main results according to geographical origin.

In this scoping review we have included a large number of publications that, despite their heterogeneity, tend to show favorable results for the usefulness of the PBL methodology in teaching and learning medicine. The results tend to be especially favorable to PBL methodology when it is compared with traditional or lecture-based teaching methods, but when compared with simulation it is not so clear. There are two studies that show neutral [ 71 ] or superior [ 80 ] results to simulation for the acquisition of specific clinical skills. It seems important to highlight that the four meta-analysis included in this review, which included a high number of participants, show results that are clearly favorable to the PBL methodology in terms of knowledge, clinical skills, problem-solving, self-learning and satisfaction [ 40 , 51 , 53 , 58 ].

Regarding the level of satisfaction described in the surveys or questionnaires, the overall satisfaction rate was higher in the PBL students when compared with traditional learning students. Students work in small groups, allowing and promoting teamwork and facilitating social and communication skills. As sessions are more attractive and dynamic than traditional classes, this could lead to a greater degree of motivation for learning.

These satisfaction results are not so favorable when tutors are asked and this may be due to different reasons; first, some studies are from the 90s, when the methodology was not yet fully implemented; second, the number of tutors included in these studies is low; and third, and perhaps most importantly, the complaints are not usually due to the methodology itself, but rather due to lack of administrative support, and/or work overload. PBL methodology implies more human and material resources. The lack of experience in guided self-learning by lecturers requires more training. Some teachers may not feel comfortable with the method and therefore do not apply it correctly.

Despite how effective and/or attractive the PBL methodology may seem, some (not many) authors are clearly detractors and have published opinion articles with fierce criticism to this methodology. Some of the arguments against are as follows: clinical problem solving is the wrong task for preclinical medical students, self-directed learning interpreted as self-teaching is not appropriate in undergraduate medical education, relegation to the role of facilitators is a misuse of the faculty, small-group experience is inherently variable and sometimes dysfunctional, etc. [ 137 ].

In light of the results found in our study, we believe that PBL is an adequate methodology for the training of future doctors and reinforces the idea that the PBL should have an important weight in the curriculum of our medical school. It is likely that training through PBL, the doctors of the future will not only have great knowledge but may also acquire greater capacity for communication, problem solving and self-learning, all of which are characteristics that are required in medical professionalism. For this purpose, Koh et al. analyzed the effect that PBL during medical school had on physician competencies after graduation, finding a positive effect mainly in social and cognitive dimensions [ 138 ].

Despite its defects and limitations, we must not abandon this methodology and, in any case, perhaps PBL should evolve, adapt, and improve to enhance its strengths and improve its weaknesses. It is likely that the new generations, trained in schools using new technologies and methodologies far from lectures, will feel more comfortable (either as students or as tutors) with methodologies more like PBL (small groups and work focused on problems or projects). It would be interesting to examine the implementation of technologies and even social media into PBL sessions, an issue that has been poorly explorer [ 139 ].

Limitations

Scoping reviews are not without limitations. Our review includes 124 articles from the 2399 initially identified and despite our efforts to be as comprehensive as possible, we may have missed some (probably few) articles. Even though this review includes many studies, their design is very heterogeneous, only a few include a large sample size and high scientific evidence methodology. Furthermore, most are single-center experiences and there are no large multi-center studies. Finally, the frequency of the PBL sessions (from once or twice a year to the whole curriculum) was not considered, in part, because most of the revised studies did not specify this information. This factor could affect the efficiency of PBL and the perceptions of students and tutors about PBL. However, the adoption of a scoping review methodology was effective in terms of summarizing the research findings, identifying limitations in studies’ methodologies and findings and provided a more rigorous vision of the international state of the art.

Conclusions

This systematic scoping review provides a broad overview of the efficacy of PBL methodology in undergraduate medicine teaching from different countries and institutions. PBL is not a new teaching method given that it has already been 50 years since it was implemented in medicine courses. It is a method that shifts the leading role from teachers to students and is based on guided self-learning. If it is applied properly, the degree of satisfaction is high, especially for students. PBL is more effective than traditional methods (based mainly on lectures) at improving social and communication skills, problem-solving and self-learning skills, and has no worse results (and in many studies better results) in relation to academic performance. Despite that, its use is not universally widespread, probably because it requires greater human resources and continuous training for its implementation. In any case, more comparative and randomized studies and/or other systematic reviews and meta-analysis are required to determine which educational strategies could be most suitable for the training of future doctors.

Abbreviations

- Problem-based learning

Case-based learning

Team-based learning

References:

Dale E. Methods for analyzing the content of motion pictures. J Educ Sociol. 1932;6:244–50.

Google Scholar

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045 .

Article Google Scholar

Bodagh N, Bloomfield J, Birch P, Ricketts W. Problem-based learning: a review. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017;78:C167–70. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2017.78.11.C167 .

- Branda LA. El abc del ABP: Lo esencial del aprendizaje basado en problemas. In: Fundación Dr. Esteve, Cuadernos de la fundación Dr. Antonio Esteve nº27: El aprendizaje basado en problemas en sus textos, pp.1–16. 2013. Barcelona.

Burgess A, Matar E, Roberts C, et al. Scaffolding medical student knowledge and skills: team-based learning (TBL) and case-based learning (CBL). BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02638-3 .

Dolmans D, Michaelsen L, van Merriënboer J, van der Vleuten C. Should we choose between problem-based learning and team-based learning? No, combine the best of both worlds! Med Teach. 2015;37:354–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.948828 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. In J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 .

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 .

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5:371–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123 .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

Sokas RK, Diserens D, Johnston MA. Integrating occupational-health into the internal medicine clerkship using problem-based learning. Clin Res. 1990;38:A735.

Richards BF, Ober KP, Cariaga-Lo L, et al. Ratings of students’ performances in a third-year internal medicine clerkship: a comparison between problem-based and lecture-based curricula. Acad Med. 1996;71:187–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199602000-00028 .

Gresham CL, Philp JR. Problem-based learning in clinical medicine. Teach Learn Med. 1996;8:111–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401339609539776 .

Hill J, Rolfe IE, Pearson SA, Heathcote A. Do junior doctors feel they are prepared for hospital practice? A study of graduates from traditional and non-traditional medical schools. Med Educ. 1998;32:19–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00152.x .

Blake RL, Parkison L. Faculty evaluation of the clinical performances of students in a problem-based learning curriculum. Teach Learn Med. 1998;10:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1002\_3 .

Hmelo CE. Problem-based learning: effects on the early acquisition of cognitive skill in medicine. J Learn Sc. 1998;7:173–208. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0702\_2 .

Finch PN. The effect of problem-based learning on the academic performance of students studying podiatric medicine in Ontario. Med Educ. 1999;33:411–7.

Casassus P, Hivon R, Gagnayre R, d’Ivernois JF. An initial experiment in haematology instruction using the problem-based learning method in third-year medical training in France. Hematol Cell Ther. 1999;41:137–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00282-999-0137-0 .

Purdy RA, Benstead TJ, Holmes DB, Kaufman DM. Using problem-based learning in neurosciences education for medical students. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26:211–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100000287 .

Farrell TA, Albanese MA, Pomrehn PRJ. Problem-based learning in ophthalmology: a pilot program for curricular renewal. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1223–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.117.9.1223 .

Curtis JA, Indyk D, Taylor B. Successful use of problem-based learning in a third-year pediatric clerkship. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:132–5. https://doi.org/10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001%3c0132:suopbl%3e2.0.co;2 .

Trevena LJ, Clarke RM. Self-directed learning in population health. a clinically relevant approach for medical students. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00395-6 .

Astin J, Jenkins T, Moore L. Medical students’ perspective on the teaching of medical statistics in the undergraduate medical curriculum. Stat Med. 2002;21:1003–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1132 .

Whitfield CR, Manger EA, Zwicker J, Lehman EB. Differences between students in problem-based and lecture-based curricula measured by clerkship performance ratings at the beginning of the third year. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14:211–7. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1404\_2 .

McParland M, Noble LM, Livingston G. The effectiveness of problem-based learning compared to traditional teaching in undergraduate psychiatry. Med Educ. 2004;38:859–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01818.x .

Casey PM, Magrane D, Lesnick TG. Improved performance and student satisfaction after implementation of a problem-based preclinical obstetrics and gynecology curriculum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1874–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.061 .

Gurpinar E, Musal B, Aksakoglu G, Ucku R. Comparison of knowledge scores of medical students in problem-based learning and traditional curriculum on public health topics. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-5-7 .

Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, et al. Effect of a community oriented problem based learning curriculum on quality of primary care delivered by graduates: historical cohort comparison study. BMJ. 2005;331:1002. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38636.582546.7C .

Abu-Hijleh MF, Chakravarty M, Al-Shboul Q, Kassab S, Hamdy H. Integrating applied anatomy in surgical clerkship in a problem-based learning curriculum. Surg Radiol Anat. 2005;27:152–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-004-0293-4 .

Distlehorst LH, Dawson E, Robbs RS, Barrows HS. Problem-based learning outcomes: the glass half-full. Acad Med. 2005;80:294–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200503000-00020 .

Hoffman K, Hosokawa M, Blake R Jr, Headrick L, Johnson G. Problem-based learning outcomes: ten years of experience at the University of Missouri-Columbia school of medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81:617–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000232411.97399.c6 .

Kong J, Li X, Wang Y, Sun W, Zhang J. Effect of digital problem-based learning cases on student learning outcomes in ophthalmology courses. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1211–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.110 .

Tsou KI, Cho SL, Lin CS, et al. Short-term outcomes of a near-full PBL curriculum in a new Taiwan medical school. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:282–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70075-0 .

Wang J, Zhang W, Qin L, et al. Problem-based learning in regional anatomy education at Peking University. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:121–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.151 .

Abou-Elhamd KA, Rashad UM, Al-Sultan AI. Applying problem-based learning to otolaryngology teaching. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:117–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215110001702 .

Urrutia Aguilar ME, Hamui-Sutton A, Castaneda Figueiras S, van der Goes TI, Guevara-Guzman R. Impact of problem-based learning on the cognitive processes of medical students. Gac Med Mex. 2011;147:385–93.

Tian J-H, Yang K-H, Liu A-P. Problem-based learning in evidence-based medicine courses at Lanzhou University. Med Teach. 2012;34:341. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.531169 .

Hoover CR, Wong CC, Azzam A. From primary care to public health: using problem-based Learning and the ecological model to teach public health to first year medical students. J Community Health. 2012;37:647–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9495-y .

Li J, Li QL, Li J, et al. Comparison of three problem-based learning conditions (real patients, digital and paper) with lecture-based learning in a dermatology course: a prospective randomized study from China. Med Teach. 2013;35:e963–70. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.719651 .

Ding X, Zhao L, Chu H, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of problem-based learning of preventive medicine education in China. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5126. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05126 .

Meo SA. Undergraduate medical student’s perceptions on traditional and problem based curricula: pilot study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:775–9.

Khoshnevisasl P, Sadeghzadeh M, Mazloomzadeh S, Hashemi Feshareki R, Ahmadiafshar A. Comparison of problem-based learning with lecture-based learning. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16: e5186. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.5186 .

Al-Drees AA, Khalil MS, Irshad M, Abdulghani HM. Students’ perception towards the problem based learning tutorial session in a system-based hybrid curriculum. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:341–8. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.3.10216 .

Al-Shaikh G, Al Mussaed EM, Altamimi TN, Elmorshedy H, Syed S, Habib F. Perception of medical students regarding problem based learning. Kuwait Med J. 2015;47:133–8.

Hande S, Mohammed CA, Komattil R. Acquisition of knowledge, generic skills and attitudes through problem-based learning: student perspectives in a hybrid curriculum. J Taibah Univ Medical Sci. 2015;10:21–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.01.008 .

González Mirasol E, Gómez García MT, Lobo Abascal P, Moreno Selva R, Fuentes Rozalén AM, González MG. Analysis of perception of training in graduates of the faculty of medicine at Universidad de Castilla-Mancha. Eval Program Plann. 2015;52:169–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.06.001 .

Yanamadala M, Kaprielian VS, O’Connor Grochowski C, Reed T, Heflin MT. A problem-based learning curriculum in geriatrics for medical students. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39:122–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2016.1152268 .

Balendran K, John L. Comparison of learning outcomes in problem based learning and lecture based learning in teaching forensic medicine. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2017;6:89–92. https://doi.org/10.14260/jemds/2017/22 .

Chang H-C, Wang N-Y, Ko W-R, Yu Y-T, Lin L-Y, Tsai H-F. The effectiveness of clinical problem-based learning model of medico-jurisprudence education on general law knowledge for obstetrics/gynecological interns. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56:325–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2017.04.011 .

Eltony SA, El-Sayed NH, El-Araby SE-S, Kassab SE. Implementation and evaluation of a patient safety course in a problem-based learning program. Educ Heal. 2017;30:44–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.210512 .

Zhang S, Xu J, Wang H, Zhang D, Zhang Q, Zou L. Effects of problem-based learning in Chinese radiology education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97: e0069. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000010069 .

Hincapie Parra DA, Ramos Monobe A, Chrino-Barcelo V. Problem based learning as an active learning strategy and its impact on academic performance and critical thinking of medical students. Rev Complut Educ. 2018;29:665–81. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.53581 .

Ma Y, Lu X. The effectiveness of problem-based learning in pediatric medical education in China: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98: e14052. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014052 .

Berger C, Brinkrolf P, Ertmer C, et al. Combination of problem-based learning with high-fidelity simulation in CPR training improves short and long-term CPR skills: a randomised single blinded trial. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1626-7 .

Aboonq M, Alquliti A, Abdulmonem I, Alpuq N, Jalali K, Arabi S. Students’ approaches to learning and perception of learning environment: a comparison between traditional and problem-based learning medical curricula. Indo Am J Pharm Sci. 2019;6:3610–9. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2562660 .

Li X, Xie F, Li X, et al. Development, application, and evaluation of a problem-based learning method in clinical laboratory education. Clin Chim ACTA. 2020;510:681–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.037 .

Zhao W, He L, Deng W, Zhu J, Su A, Zhang Y. The effectiveness of the combined problem-based learning (PBL) and case-based learning (CBL) teaching method in the clinical practical teaching of thyroid disease. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02306 .

Liu C-X, Ouyang W-W, Wang X-W, Chen D, Jiang Z-L. Comparing hybrid problem-based and lecture learning (PBL plus LBL) with LBL pedagogy on clinical curriculum learning for medical students in China: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19687. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000019687 .

Margolius SW, Papp KK, Altose MD, Wilson-Delfosse AL. Students perceive skills learned in pre-clerkship PBL valuable in core clinical rotations. Med Teach. 2020;42:902–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1762031 .

Schwartz RW, Donnelly MB, Nash PP, Young B. Developing students cognitive skills in a problem-based surgery clerkship. Acad Med. 1992;67:694–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199210000-00016 .

Mennin SP, Friedman M, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Snyder J. Performances on the NBME-I, NBME-II, and NBME-III by medical-students in the problem-based learning and conventional tracks at the university-of-new-mexico. Acad Med. 1993;68:616–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199308000-00012 .

Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Comparing achievement on the medical council of Canada qualifying examination part I of students in conventional and problem-based learning curricula. Acad Med. 1998;73:1211–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199811000-00022 .

Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Achievement of students in a conventional and Problem-Based Learning (PBL) curriculum. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 1999;4:245–60. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009829831978 .

Antepohl W, Herzig S. Problem-based learning versus lecture-based learning in a course of basic pharmacology: a controlled, randomized study. Med Educ. 1999;33:106–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00289.x .

Dyke P, Jamrozik K, Plant AJ. A randomized trial of a problem-based learning approach for teaching epidemiology. Acad Med. 2001;76:373–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00016 .

Brewer DW. Endocrine PBL in the year 2000. Adv Physiol Educ. 2001;25:249–55. https://doi.org/10.1152/advances.2001.25.4.249 .

Seneviratne RD, Samarasekera DD, Karunathilake IM, Ponnamperuma GG. Students’ perception of problem-based learning in the medical curriculum of the faculty of medicine, University of Colombo. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:379–81.

Alleyne T, Shirley A, Bennett C, et al. Problem-based compared with traditional methods at the faculty of medical sciences, University of the West Indies: a model study. Med Teach. 2002;24:273–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590220125286 .

Norman GR, Wenghofer E, Klass D. Predicting doctor performance outcomes of curriculum interventions: problem-based learning and continuing competence. Med Educ. 2008;42:794–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03131.x .

Cohen-Schotanus J, Muijtjens AMM, Schoenrock-Adema J, Geertsma J, van der Vleuten CPM. Effects of conventional and problem-based learning on clinical and general competencies and career development. Med Educ. 2008;42:256–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02959.x .

Wenk M, Waurick R, Schotes D, et al. Simulation-based medical education is no better than problem-based discussions and induces misjudgment in self-assessment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14:159–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9098-2 .

Collard A, Gelaes S, Vanbelle S, et al. Reasoning versus knowledge retention and ascertainment throughout a problem-based learning curriculum. Med Educ. 2009;43:854–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03410.x .

Nouns Z, Schauber S, Witt C, Kingreen H, Schuettpelz-Brauns K. Development of knowledge in basic sciences: a comparison of two medical curricula. Med Educ. 2012;46:1206–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12047 .

Saloojee S, van Wyk J. The impact of a problem-based learning curriculum on the psychiatric knowledge and skills of final-year students at the Nelson R Mandela school of medicine. South African J Psychiatry. 2012;18:116.

Mughal AM, Shaikh SH. Assessment of collaborative problem solving skills in undergraduate medical students at Ziauddin college of medicine. Karachi Pakistan J Med Sci. 2018;34:185–9. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.341.13485 .

Hu X, Zhang H, Song Y, et al. Implementation of flipped classroom combined with problem-based learning: an approach to promote learning about hyperthyroidism in the endocrinology internship. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1714-8 .

Thompson KL, Gendreau JL, Strickling JE, Young HE. Cadaveric dissection in relation to problem-based learning case sequencing: a report of medical student musculoskeletal examination performances and self-confidence. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12:619–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1891 .

Chang G, Cook D, Maguire T, Skakun E, Yakimets WW, Warnock GL. Problem-based learning: its role in undergraduate surgical education. Can J Surg. 1995;38:13–21.

Vernon DTA, Hosokawa MC. Faculty attitudes and opinions about problem-based learning. Acad Med. 1996;71:1233–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199611000-00020 .

Steadman RH, Coates WC, Huang YM, et al. Simulation-based training is superior to problem-based learning for the acquisition of critical assessment and management skills. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:151–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000190619.42013.94 .

Johnston JM, Schooling CM, Leung GM. A randomised-controlled trial of two educational modes for undergraduate evidence-based medicine learning in Asia. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-63 .

Suleman W, Iqbal R, Alsultan A, Baig SM. Perception of 4(th) year medical students about problem based learning. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2010;26:871–4.

Blosser A, Jones B. Problem-based learning in a surgery clerkship. Med Teach. 1991;13:289–93. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421599109089907 .

Usherwood T, Joesbury H, Hannay D. Student-directed problem-based learning in general-practice and public-health medicine. Med Educ. 1991;25:421–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00090.x .

Bernstein P, Tipping J, Bercovitz K, Skinner HA. Shifting students and faculty to a PBL curriculum - attitudes changed and lessons learned. Acad Med. 1995;70:245–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199503000-00019 .

Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Comparing students’ attitudes in problem-based and conventional curricula. Acad Med. 1996;71:1096–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199610000-00018 .

Kalaian HA, Mullan PB. Exploratory factor analysis of students’ ratings of a problem-based learning curriculum. Acad Med. 1996;71:390–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199604000-00019 .

Vincelette J, Lalande R, Delorme P, Goudreau J, Lalonde V, Jean P. A pilot course as a model for implementing a PBL curriculum. Acad Med. 1997;72:698–701. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199708000-00015 .

Ghosh S, Dawka V. Combination of didactic lecture with problem-based learning sessions in physiology teaching in a developing medical college in Nepal. Adv Physiol Educ. 2000;24:8–12.

Walters MR. Problem-based learning within endocrine physiology lectures. Adv Physiol Educ. 2001;25:225–7. https://doi.org/10.1152/advances.2001.25.4.225 .

Leung GM, Lam TH, Hedley AJ. Problem-based public health learning - from the classroom to the community. Med Educ. 2001;35:1071–2.

Khoo HE, Chhem RK, Gwee MCE, Balasubramaniam P. Introduction of problem-based learning in a traditional medical curriculum in Singapore - students’ and tutors’ perspectives. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:371–4.

Villamor MCA. Problem-based learning (PBL) as an approach in the teaching of biochemistry of the endocrine system at the Angeles University College of Medicine. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:382–6.

Chang C-H, Yang C-Y, See L-C, Lui P-W. High satisfaction with problem-based learning for anesthesia. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:654–62.

McLean M. A comparison of students who chose a traditional or a problem-based learning curriculum after failing year 2 in the traditional curriculum: a unique case study at the Nelson R. Mandela school of medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:301–3. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328015tlm1603\_15 .

Lucas M, García Guasch R, Moret E, Llasera R, Melero A. Canet J [Problem-based learning in an undergraduate medical school course on anesthesiology, recovery care, and pain management]. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2006;53:419–25.

Burgun A, Darmoni S, Le Duff F, Weber J. Problem-based learning in medical informatics for undergraduate medical students: an experiment in two medical schools. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.014 .

Gurpinar E, Senol Y, Aktekin MR. Evaluation of problem based learning by tutors and students in a medical faculty of Turkey. Kuwait Med J. 2009;41:123–7.

Elzubeir MA. Teaching of the renal system in an integrated, problem-based curriculum. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23:93–8.

Sulaiman N, Hamdy H. Problem-based learning: where are we now? Guide supplement 36.3–practical application. Med Teach. 2013;35:160–2. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.737965 .

Albarrak AI, Mohammed R, Abalhassan MF, Almutairi NK. Academic satisfaction among traditional and problem based learning medical students a comparative study. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:1179–88.

Nosair E, Mirghani Z, Mostafa RM. Measuring students’ perceptions of educational environment in the PBL program of Sharjah Medical College. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2015;2:71–9. https://doi.org/10.4137/JMECDECDECD.S29926 .

Tshitenge ST, Ndhlovu CE, Ogundipe R. Evaluation of problem-based learning curriculum implementation in a clerkship rotation of a newly established African medical training institution: lessons from the University of Botswana. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:13. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.27.13.10623 .

Yadav RL, Piryani RM, Deo GP, Shah DK, Yadav LK, Islam MN. Attitude and perception of undergraduate medical students toward the problem-based learning in Chitwan Medical College. Nepal Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:317–22. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S160814 .

Asad MR, Tadvi N, Amir KM, Afzal K, Irfan A, Hussain SA. Medical student’s feedback towards problem based learning and interactive lectures as a teaching and learning method in an outcome-based curriculum. Int J Med Res & Heal Sci. 2019;8:78–84. https://doi.org/10.33844/ijol.2019.60392 .

Mpalanyi M, Nalweyiso ID, Mubuuke AG. Perceptions of radiography students toward problem-based learning almost two decades after its introduction at Makerere University. Uganda J Med imaging Radiat Sci. 2020;51:639–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2020.06.009 .

Korkmaz NS, Ozcelik S. Evaluation of the opinions of the first, second and third term medical students about problem based learning sessions in Bezmialem Vakif University. Bezmialem Sci. 2020;8:144–9. https://doi.org/10.14235/bas.galenos.2019.3471 .

McGrew MC, Skipper B, Palley T, Kaufman A. Student and faculty perceptions of problem-based learning on a family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 1999;31:171–6.

Kelly AM. A problem-based learning resource in emergency medicine for medical students. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:320–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.17.5.320 .

Bui-Mansfield LT, Chew FS. Radiologists as clinical tutors in a problem-based medical school curriculum. Acad Radiol. 2001;8:657–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80693-1 .

Macallan DC, Kent A, Holmes SC, Farmer EA, McCrorie P. A model of clinical problem-based learning for clinical attachments in medicine. Med Educ. 2009;43:799–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03406.x .

Grisham JW, Martiniuk ALC, Negin J, Wright EP. Problem-based learning (PBL) and public health: an initial exploration of perceptions of PBL in Vietnam. Asia-Pacific J public Heal. 2015;27:NP2019-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539512436875 .

Khan IA, Al-Swailmi FK. Perceptions of faculty and students regarding Problem Based Learning: a mixed methods study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65:1334–8.

Alduraywish AA, Mohager MO, Alenezi MJ, Nail AM, Aljafari AS. Evaluation of students’ experience with Problem-based Learning (PBL) applied at the College of Medicine, Al-Jouf University. Saudi Arabia J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:1870–3.

Yoo DM, Cho AR, Kim S. Satisfaction with and suitability of the problem-based learning program at the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2019;16:20. https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2019.16.20 .

Aldayel AA, Alali AO, Altuwaim AA, et al. Problem-based learning: medical students’ perception toward their educational environment at Al-Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:95–104. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S189062 .

DeLowerntal E. An evaluation of a module in problem-based learning. Int J Educ Dev. 1996;16:303–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-0593(96)00001-6 .

Tufts MA, Higgins-Opitz SB. What makes the learning of physiology in a PBL medical curriculum challenging? Student perceptions. Adv Physiol Educ. 2009;33:187–95. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.90214.2008 .

Aboonq M. Perception of the faculty regarding problem-based learning as an educational approach in Northwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1329–35. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.11.12263 .

Subramaniam RM, Scally P, Gibson R. Problem-based learning and medical student radiology teaching. Australas Radiol. 2004;48:335–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-8461.2004.01317.x .

Chang BJ. Problem-based learning in medical school: a student’s perspective. Ann Med Surg. 2016;12:88–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2016.11.011 .

Griffith CD, Blue AV, Mainous AG, DeSimone PA. Housestaff attitudes toward a problem-based clerkship. Med Teach. 1996;18:133–4. https://doi.org/10.3109/01421599609034147 .

Navarro HN, Zamora SJ. The opinion of teachers about tutorial problem based learning. Rev Med Chil. 2014;142:989–97. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872014000800006 .

Demiroren M, Turan S, Oztuna D. Medical students’ self-efficacy in problem-based learning and its relationship with self-regulated learning. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:30049. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.30049 .

Tousignant M, DesMarchais JE. Accuracy of student self-assessment ability compared to their own performance in a problem-based learning medical program: a correlation study. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2002;7:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014516206120 .

Brynhildsen J, Dahle LO, Behrbohm Fallsberg M, Rundquist I, Hammar M. Attitudes among students and teachers on vertical integration between clinical medicine and basic science within a problem-based undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Teach. 2002;24:286–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590220134105 .

Desmarchais JE. A student-centered, problem-based curriculum - 5 years experience. Can Med Assoc J. 1993;148:1567–72.

Doig K, Werner E. The marriage of a traditional lecture-based curriculum and problem-based learning: are the offspring vigorous? Med Teach. 2000;22:173–8.

Kemahli S. Hematology education in a problem-based curriculum. Hematology. 2005;10(Suppl 1):161–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/10245330512331390267 .

Grkovic I. Transition of the medical curriculum from classical to integrated: problem-based approach and Australian way of keeping academia in medicine. Croat Med J. 2005;46:16–20.

Bosch-Barrera J, Briceno Garcia HC, Capella D, et al. Teaching bioethics to students of medicine with Problem-Based Learning (PBL). Cuad Bioet. 2015;26:303–9.

Lin Y-C, Huang Y-S, Lai C-S, Yen J-H, Tsai W-C. Problem-based learning curriculum in medical education at Kaohsiung Medical University. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:264–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70072-5 .

Salinas Sánchez AS, Hernández Millán I, Virseda Rodríguez JA, et al. Problem-based learning in urology training the faculty of medicine of the Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha model. Actas Urol Esp. 2005;29:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0210-4806(05)73193-4 .

Amoako-Sakyi D, Amonoo-Kuofi H. Problem-based learning in resource-poor settings: lessons from a medical school in Ghana. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0501-4 .

Carrera LI, Tellez TE, D’Ottavio AE. Implementing a problem-based learning curriculum in an Argentinean medical school: implications for developing countries. Acad Med. 2003;78:798–801. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200308000-00010 .

Vernon DT, Blake RL. Does problem-based learning work? A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad Med. 1993;68:550–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199307000-00015 .

Shanley PF. Viewpoint: leaving the “empty glass” of problem-based learning behind: new assumptions and a revised model for case study in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2007;82:479–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803eac4c .

Koh GC, Khoo HE, Wong ML, Koh D. The effects of problem-based learning during medical school on physician competency: a systematic review. CMAJ. 2008;178:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070565 .

Awan ZA, Awan AA, Alshawwa L, Tekian A, Park YS. Assisting the integration of social media in problem-based learning sessions in the faculty of medicine at King Abdulaziz University. Med Teach. 2018;40:S37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1465179 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Medical Education Cathedra, School of Medicine, University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia, Vic, Barcelona, Spain

Joan Carles Trullàs, Carles Blay & Ramon Pujol

Internal Medicine Service, Hospital de Olot i Comarcal de La Garrotxa, Olot, Girona, Spain

Joan Carles Trullàs

The Tissue Repair and Regeneration Laboratory (TR2Lab), University of Vic-Central University of Catalonia, Vic, Barcelona, Spain

Joan Carles Trullàs & Elisabet Sarri

Catalan Institute of Health (ICS) – Catalunya Central, Barcelona, Spain

Carles Blay

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JCT had the idea for the article, performed the literature search and data analysis and drafted the first version of the manuscript. CB, ES and RP contributed to the data analysis and suggested revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Availability of data and materials.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for a literature review.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Characteristics ofthe 124 included studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Trullàs, J.C., Blay, C., Sarri, E. et al. Effectiveness of problem-based learning methodology in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 22 , 104 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03154-8

Download citation

Received : 03 October 2021

Accepted : 02 February 2022

Published : 17 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03154-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Problem-Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) uses clinical cases to stimulate inquiry, critical thinking and knowledge application and integration related to biological, behavioral and social sciences. Through this active, collaborative, case-based learning process, students acquire a deeper understanding of the principles of medicine and, more importantly, acquire the skills necessary for lifelong learning.

The goal is for students to:

- Acquire, synthesize and apply basic science knowledge in a clinical context

- Engage in critical thinking and problem-solving

- Develop the ability to evaluate their own learning and collaborate with peers

- Effectively use information technology and identify the most appropriate resources for knowledge acquisition and hypothesis testing

- Contextualize and communicate their knowledge to others

- Ask for, provide and incorporate feedback in order to improve performance

Each PBL group has six to nine students and a faculty facilitator. Case information is disclosed progressively across two or more sessions for each case. This process mimics the manner in which a practicing physician obtains data from a patient. PBL allows students to develop hypotheses and identify learning issues as the additional pieces of information about a patient are disclosed to the student.

The students identify learning issues and information needs and assign learning tasks among the group. The students discuss their findings at the next session and review the case in light of their learning. At the conclusion of a case, the students create a concept map synthesizing the knowledge garnered over the course of their discussions to demonstrate their understanding of how the elements of the case integrate with and relate to one another.

Faculty Development Modules

Faculty interested in learning more about PBL should review these online learning modules.

Welcome to PBL: A Guide for Tutors

This module is required for new tutors and optional for experienced tutors who are interested in a refresher course. It is intended to serve as an introduction to facilitating small-group sessions in the PBL course. This video will show you what a PBL session looks like and demonstrates some tutor behaviors. Open the module and use password fsmpbl for access.

PBL Tutor Feedback Module

All tutors (new and experienced) must go through this brief training module to help you provide students with feedback in the context of the PBL course. Open the module (Safari or Firefox recommended) and sign in when prompted with your NetID and password. Completing the module will count toward CME credit.

Kristin Van Genderen, MD

Co-Director

View Faculty Profile

Nahzinine Shakeri, MD

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Problem based learning...

Problem based learning in continuing medical education: a review of controlled evaluation studies

- Related content

- Peer review

- P B A Smits , occupational physician ( p.b.smits{at}amc.uva.nl ) a ,

- J H A M Verbeek , PhD occupational physician b ,

- C D de Buisonjé , educational researcher a

- a Netherlands School of Occupational Health, PO Box 2557, 1000 CN Amsterdam, Netherlands,

- b Coronel Institute, Academic Medical Centre/University of Amsterdam, PO Box 22660, 1100 DD Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Correspondence to: P B A Smits

- Accepted 20 September 2001

Problem based learning is one of the best described methods of interactive learning, and many claim it is more effective than traditional methods in terms of lifelong learning skills, and is more fun. 1 In the early 1990s, four systematic reviews of undergraduate medical education cautiously supported the short term and long term outcomes of problem based learning compared with traditional learning. 2 – 5 Since then, many medical curricula have changed to problem based learning, but a recent review has questioned the value of problem based learning in undergraduate medical education. 6

Postgraduate and continuing medical education differ from undergraduate education in that they go beyond increasing knowledge and skills to improving physician competence and performance in practice, ultimately leading to better patient health. 7 Problem based learning may also be effective in this context. 8 There is some evidence that interactive sessions can change professional practice, but there have been few well conducted trials. 9 10

We could find no reviews of the effectiveness of problem based learning in continuing medical education. Controlled evaluation studies provide the best evidence of effectiveness of educational methods, in line with the movement of best evidence medical education. 11 We therefore conducted a systematic review of the literature to find out if there is evidence that problem based learning in continuing medical education is effective.

Summary points

Reviews of undergraduate medical education cautiously support the short term and long term outcomes of problem based learning compared with traditional learning

The effectiveness of problem based learning in continuing medical education, however, has not been reviewed

This review of controlled evaluation studies found limited evidence that problem based learning in continuing medical education increased participants' knowledge and performance and patients' health

There was moderate evidence that doctors are more satisfied with problem based learning

Literature search

We searched the databases Medline, Embase, Psyclit, the Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC), the Cochrane Library , and the Research and Development Resource Base in CME on the Internet (RDRBWEB) from 1974 (the year Neufeld and Barrows published their new approach to medical education) to August 2000. We searched for studies with the keywords “problem-based (PBL),” “practice-based,” “self-directed,” “learner centred,” and “active learning.” We combined the search results with another search using the keywords “continuing medical education (CME),” “continuing professional development (CPD),” “post-professional,” “postgraduate,” and “adult learning.” Finally, we conducted a manual search of relevant references in the included studies.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies in which the author(s) had indicated that the educational intervention was problem based and in which the learning process in essence resembled the methods used at McMaster University or the University of Maastricht. 12 13 This consists of a tutor facilitated, problem based learning session in which a small, self directed group starts with a brainstorming session. A problem is posed that challenges their knowledge and experience. Learning goals are formulated by consensus, and new information is learnt by self directed study. It ends with a group discussion and evaluation.

For this review, we included keywords to find relevant educational articles in the total domain of postgraduate and continuing medical education and continuing professional development. We scanned all the studies collected for controlled trials with a pretest/post-test design. Because of the small number of randomised trials, we did not exclude other types of controlled trial. With this strategy, we hoped to find all relevant controlled studies on problem based learning in continuing medical education.

Review method of selected studies

Two reviewers (PBAS and JHAMV) independently assessed the quality of the studies using five quality criteria. Each criterion was allotted a maximum of 10 points, making a maximum possible score of 50 points (see appendix on bmj.com for more details). We discarded a sixth possible criterion, that groups should be treated equally, with the exception of experimental education. 14 Many factors may influence the outcome of education (tutor, educational materials, lecture rooms, etc), and it was not possible to extract this information from the studies: we therefore could not assess equal treatment of groups.

Studies with a total score of ≥25 points were considered to be of high quality, and those with <25 points were of low quality. We distinguished two different categories of study by the control groups: in one category problem based learning was compared with a more lecture based programme, while in the other it was compared with no educational intervention.

Outcome variables

For each study, we looked for four outcome variables— participants' knowledge, performance, and satisfaction and patients' health—and assessed the level of evidence on these. We graded the evidence for the effectiveness of problem based learning as strong if there was a positive outcome in two high quality studies, as moderate if there was a positive outcome in one high quality and one low quality study, as limited if there was a positive outcome in one high quality study or one or more low quality study, and none if there was a contradictory outcome or no outcome.

Quality assessment of six studies evaluating effectiveness of problem based learning in continuing medical education

- View inline

Results of six studies evaluating effectiveness of problem based learning in continuing medical education

Results of literature search

Six controlled trials met our inclusion criteria. 15 – 20 A manual search of references from these studies did not yield any new trials that met our criteria. Five of the studies assessed the effect of continuing medical education on general practitioners. Four studies contained over 50 participants, 16 – 18 20 and two had fewer than 20. 15 19

Table 1 shows the results of our quality assessment of the six studies. Two studies were of “high” quality, 15 17 and the others were “low.” Two of the trials were randomised trials. 15 16 In Heale et al's study, however, the group of randomly allocated doctors was combined with a group who did not want to participate in the entire study. 16 Whether the randomisation is valid in terms of equality of groups is unclear.

Results of studies

Table 2 shows the results of the six studies. Outcome measurement was often restricted to only one variable. No study measured both the preferred outcome variables—participants' performance and patients' health. In one of the high quality studies—problem based learning via email versus use of internet resources—neither educational programme increased participants' knowledge, but group size was small. 15 The other high quality study—problem based versus lecture based learning—showed positive results for problem based learning in terms of participants' knowledge, clinical reasoning, and satisfaction. 17 It is unclear whether these effects can be attributed to the problem based learning format, however, because of differing periods of educational exposure.

Table 3 shows the level of evidence we found for the outcome variables. With the three studies that compared problem based learning with another educational format, we found no evidence that problem based learning affected participants' knowledge and performance and moderate evidence that it increased participants' satisfaction. None of the studies measured patients' health. The other three studies compared problem based learning with no educational intervention and were of low quality. They show limited evidence that problem based learning was effective in improving participants' knowledge and performance and patients' health (table 3 ). Differing degrees of satisfaction cannot be compared in this study design.

Level of evidence on outcome variables measured in six studies evaluating effectiveness of problem based learning in continuing medical education

Conclusions

We found few relevant studies, of varying quality. There is no consistent evidence that problem based learning in continuing medical education was superior to other educational strategies in increasing doctors' knowledge and performance but moderate evidence that it led to higher satisfaction. There is limited evidence that problem based learning increased doctors' knowledge and performance and patients' health more than no educational intervention at all.

However, the studies in which the control group received no educational intervention can give information only on the effects of receiving education, not of the specific educational method. With the studies that compared problem based learning with another method, in order to deduce that one educational intervention is more effective, the content, process, and influencing variables in both interventions must be clearly stated. The information on the educational interventions given in the three studies can be rated as completely absent, 16 poor, 15 and reasonable. 17

In studies not restricted to problem based learning, there is some evidence that interactive educational methods in continuing medical education are more effective in changing doctors' performance and patients' health. 9 The results of this literature study on problem based learning in continuing medical education seem to be comparable with those on problem based learning in undergraduate medical education. 2 – 4

Studying the effectiveness of education is complex, 21 22 but we should be able to perform studies of higher quality than those reviewed here, especially when comparing educational methods. As our review found, it is apparently not impossible to randomise participants to different educational methods. We have to do better in defining an educational method and controlling what actually happens in educational practice. We also have to clarify the aims of our education. Is our objective to increase knowledge, change attitudes, or improve health care? Outcome variables should correspond with our objectives, and preferably several different variables should be measured, including participants' performance and patients' health. 9 There seems to be agreement that a small significant effect found is evidence of effectiveness. 21 23 Evaluation is further complicated by professional and social context, as is shown in research on implementation of guidelines. 24 This calls for randomisation, because observational studies can easily be biased by these factors.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: PBAS coordinated the systematic review, formulated the study hypothesis, performed the searches, assessed the quality of studies, and wrote the article. JHAMV initiated the review, helped formulate the study hypothesis, supervised the systematic approach of the review, reported on the results, and helped write the article. CDdB helped formulate the study hypothesis, performed the searches, and made a first review and draft of the study results. PBAS and JHAMV are guarantors for this article.

Editorials by Prideaux and Goldbeck-Wood and Peile

Funding This study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) as part of the priority programme on fatigue and work and by the Netherlands School of Occupational Health.

Competing interests None declared.

- Dolmans D ,

- Albanese MA ,

- Vernon DT ,

- Norman GR ,

- Colliver JA

- Bennett NL ,

- Easterling WE ,

- Friedmann P ,

- Koeppen BM ,

- Dolmans DHJM ,

- van der Vleuten CPM

- O'Brien MA ,

- Freemantle N ,

- Mazmanian P ,

- Taylor-Vaisey A

- Coffey CMM ,

- Carr-Gregg M ,

- Patton GC ,

- Albanese MA

- Sackett DL ,

- Straus SE ,

- Richardson WS ,

- Rosenberg W ,

- Leclair K ,

- Kaczorowski J

- Woodward C ,

- Neufeld V ,

- Doucet MD ,

- Kaufman DM ,

- Langille DB

- Benjamin EM ,

- Schneider MS ,

- Shannon S ,

- Hartwick K ,

- Wakefield J ,

- Cate ThJ ten

Problem-Based Learning

- First Online: 17 March 2022

Cite this chapter

- Debra Klamen 11 ,

- Boyung Suh 11 &

- Shelley Tischkau 11

Part of the book series: Innovation and Change in Professional Education ((ICPE,volume 20))

841 Accesses

1 Citations