Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

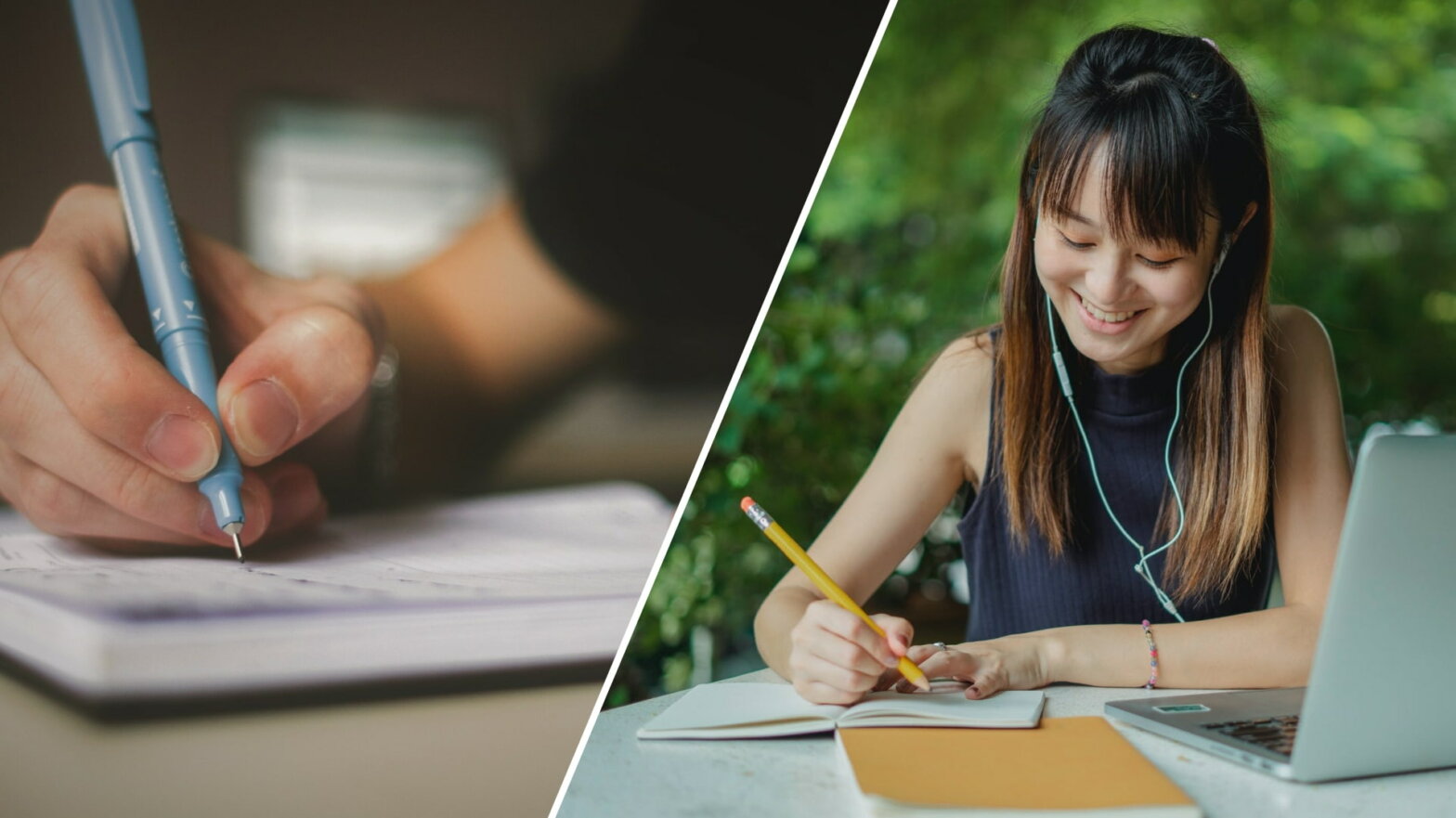

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Academic Proposals

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource introduces the genre of academic proposals and provides strategies for developing effective graduate-level proposals across multiple contexts.

Introduction

An important part of the work completed in academia is sharing our scholarship with others. Such communication takes place when we present at scholarly conferences, publish in peer-reviewed journals, and publish in books. This OWL resource addresses the steps in writing for a variety of academic proposals.

For samples of academic proposals, click here .

Important considerations for the writing process

First and foremost, you need to consider your future audience carefully in order to determine both how specific your topic can be and how much background information you need to provide in your proposal. While some conferences and journals may be subject-specific, most will require you to address an audience that does not conduct research on the same topics as you. Conference proposal reviewers are often drawn from professional organization members or other attendees, while journal proposals are typically reviewed by the editorial staff, so you need to ensure that your proposal is geared toward the knowledge base and expectations of whichever audience will read your work.

Along those lines, you might want to check whether you are basing your research on specific prior research and terminology that requires further explanation. As a rule, always phrase your proposal clearly and specifically, avoid over-the-top phrasing and jargon, but do not negate your own personal writing style in the process.

If you would like to add a quotation to your proposal, you are not required to provide a citation or footnote of the source, although it is generally preferred to mention the author’s name. Always put quotes in quotation marks and take care to limit yourself to at most one or two quotations in the entire proposal text. Furthermore, you should always proofread your proposal carefully and check whether you have integrated details, such as author’s name, the correct number of words, year of publication, etc. correctly.

Methodology is often a key factor in the evaluation of proposals for any academic genre — but most proposals have such a small word limit that writers find it difficult to adequately include methods while also discussing their argument, background for the study, results, and contributions to knowledge. It's important to make sure that you include some information about the methods used in your study, even if it's just a line or two; if your proposal isn't experimental in nature, this space should instead describe the theory, lens, or approach you are taking to arrive at your conclusions.

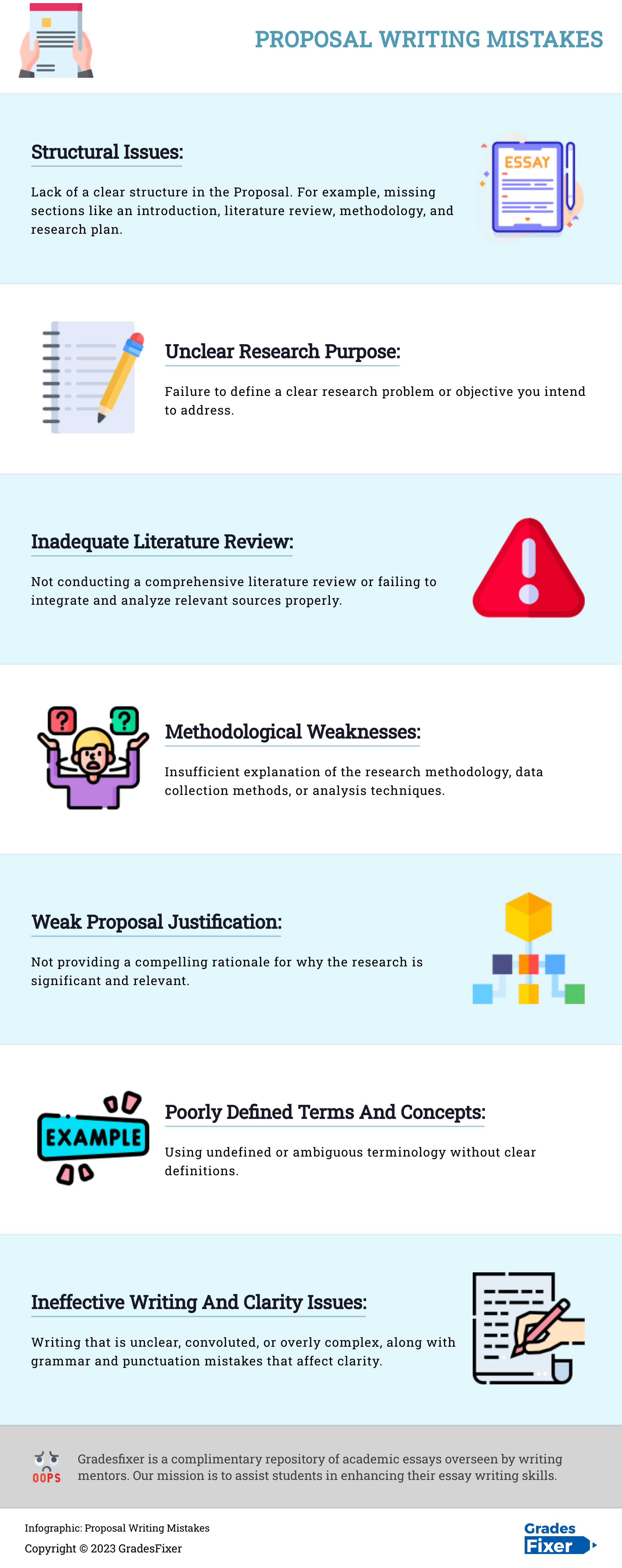

Reasons proposals fail/common pitfalls

There are common pitfalls that you might need to improve on for future proposals.

The proposal does not reflect your enthusiasm and persuasiveness, which usually goes hand in hand with hastily written, simply worded proposals. Generally, the better your research has been, the more familiar you are with the subject and the more smoothly your proposal will come together.

Similarly, proposing a topic that is too broad can harm your chances of being accepted to a conference. Be sure to have a clear focus in your proposal. Usually, this can be avoided by more advanced research to determine what has already been done, especially if the proposal is judged by an important scholar in the field. Check the names of keynote speakers and other attendees of note to avoid repeating known information or not focusing your proposal.

Your paper might simply have lacked the clear language that proposals should contain. On this linguistic level, your proposal might have sounded repetitious, have had boring wording, or simply displayed carelessness and a lack of proofreading, all of which can be remedied by more revisions. One key tactic for ensuring you have clear language in your proposal is signposting — you can pick up key phrases from the CFP, as well as use language that indicates different sections in academic work (as in IMRAD sections from the organization and structure page in this resource). This way, reviewers can easily follow your proposal and identify its relatedness to work in the field and the CFP.

Conference proposals

Conference proposals are a common genre in graduate school that invite several considerations for writing depending on the conference and requirements of the call for papers.

Beginning the process

Make sure you read the call for papers carefully to consider the deadline and orient your topic of presentation around the buzzwords and themes listed in the document. You should take special note of the deadline and submit prior to that date, as most conferences use online submission systems that will close on a deadline and will not accept further submissions.

If you have previously spoken on or submitted a proposal on the same topic, you should carefully adjust it specifically for this conference or even completely rewrite the proposal based on your changing and evolving research.

The topic you are proposing should be one that you can cover easily within a time frame of approximately fifteen to twenty minutes. You should stick to the required word limit of the conference call. The organizers have to read a large number of proposals, especially in the case of an international or interdisciplinary conference, and will appreciate your brevity.

Structure and components

Conference proposals differ widely across fields and even among individual conferences in a field. Some just request an abstract, which is written similarly to any other abstract you'd write for a journal article or other publication. Some may request abstracts or full papers that fit into pre-existing sessions created by conference organizers. Some request both an abstract and a further description or proposal, usually in cases where the abstract will be published in the conference program and the proposal helps organizers decide which papers they will accept.

If the conference you are submitting to requires a proposal or description, there are some common elements you'll usually need to include. These are a statement of the problem or topic, a discussion of your approach to the problem/topic, a discussion of findings or expected findings, and a discussion of key takeaways or relevance to audience members. These elements are typically given in this order and loosely follow the IMRAD structure discussed in the organization and structure page in this resource.

The proportional size of each of these elements in relation to one another tends to vary by the stage of your research and the relationship of your topic to the field of the conference. If your research is very early on, you may spend almost no time on findings, because you don't have them yet. Similarly, if your topic is a regular feature at conferences in your field, you may not need to spend as much time introducing it or explaining its relevance to the field; however, if you are working on a newer topic or bringing in a topic or problem from another discipline, you may need to spend slightly more space explaining it to reviewers. These decisions should usually be based on an analysis of your audience — what information can reviewers be reasonably expected to know, and what will you have to tell them?

Journal Proposals

Most of the time, when you submit an article to a journal for publication, you'll submit a finished manuscript which contains an abstract, the text of the article, the bibliography, any appendices, and author bios. These can be on any topic that relates to the journal's scope of interest, and they are accepted year-round.

Special issues , however, are planned issues of a journal that center around a specific theme, usually a "hot topic" in the field. The editor or guest editors for the special issue will often solicit proposals with a call for papers (CFP) first, accept a certain number of proposals for further development into article manuscripts, and then accept the final articles for the special issue from that smaller pool. Special issues are typically the only time when you will need to submit a proposal to write a journal article, rather than submitting a completed manuscript.

Journal proposals share many qualities with conference proposals: you need to write for your audience, convey the significance of your work, and condense the various sections of a full study into a small word or page limit. In general, the necessary components of a proposal include:

- Problem or topic statement that defines the subject of your work (often includes research questions)

- Background information (think literature review) that indicates the topic's importance in your field as well as indicates that your research adds something to the scholarship on this topic

- Methodology and methods used in the study (and an indication of why these methods are the correct ones for your research questions)

- Results or findings (which can be tentative or preliminary, if the study has not yet been completed)

- Significance and implications of the study (what will readers learn? why should they care?)

This order is a common one because it loosely follows the IMRAD (introduction, methods, results and discussion) structure often used in academic writing; however, it is not the only possible structure or even always the best structure. You may need to move these elements around depending on the expectations in your field, the word or page limit, or the instructions given in the CFP.

Some of the unique considerations of journal proposals are:

- The CFP may ask you for an abstract, a proposal, or both. If you need to write an abstract, look for more information on the abstract page. If you need to write both an abstract and a proposal, make sure to clarify for yourself what the difference is. Usually the proposal needs to include more information about the significance, methods, and/or background of the study than will fit in the abstract, but often the CFP itself will give you some instructions as to what information the editors are wanting in each piece of writing.

- Journal special issue CFPs, like conference CFPs, often include a list of topics or questions that describe the scope of the special issue. These questions or topics are a good starting place for generating a proposal or tying in your research; ensuring that your work is a good fit for the special issue and articulating why that is in the proposal increases your chances of being accepted.

- Special issues are not less valuable or important than regularly scheduled issues; therefore, your proposal needs to show that your work fits and could readily be accepted in any other issue of the journal. This means following some of the same practices you would if you were preparing to submit a manuscript to a journal: reading the journal's author submission guidelines; reading the last several years of the journal to understand the usual topics, organization, and methods; citing pieces from this journal and other closely related journals in your research.

Book Proposals

While the requirements are very similar to those of conference proposals, proposals for a book ought to address a few other issues.

General considerations

Since these proposals are of greater length, the publisher will require you to delve into greater detail as well—for instance, regarding the organization of the proposed book or article.

Publishers generally require a clear outline of the chapters you are proposing and an explication of their content, which can be several pages long in its entirety.

You will need to incorporate knowledge of relevant literature, use headings and sub-headings that you should not use in conference proposals. Be sure to know who wrote what about your topic and area of interest, even if you are proposing a less scholarly project.

Publishers prefer depth rather than width when it comes to your topic, so you should be as focused as possible and further outline your intended audience.

You should always include information regarding your proposed deadlines for the project and how you will execute this plan, especially in the sciences. Potential investors or publishers need to know that you have a clear and efficient plan to accomplish your proposed goals. Depending on the subject area, this information can also include a proposed budget, materials or machines required to execute this project, and information about its industrial application.

Pre-writing strategies

As John Boswell (cited in: Larsen, Michael. How to Write a Book Proposal. Writers Digest Books , 2004. p. 1) explains, “today fully 90 percent of all nonfiction books sold to trade publishers are acquired on the basis of a proposal alone.” Therefore, editors and agents generally do not accept completed manuscripts for publication, as these “cannot (be) put into the usual channels for making a sale”, since they “lack answers to questions of marketing, competition, and production.” (Lyon, Elizabeth. Nonfiction Book Proposals Anybody Can Write . Perigee Trade, 2002. pp. 6-7.)

In contrast to conference or, to a lesser degree, chapter proposals, a book proposal introduces your qualifications for writing it and compares your work to what others have done or failed to address in the past.

As a result, you should test the idea with your networks and, if possible, acquire other people’s proposals that discuss similar issues or have a similar format before submitting your proposal. Prior to your submission, it is recommended that you write at least part of the manuscript in addition to checking the competition and reading all about the topic.

The following is a list of questions to ask yourself before committing to a book project, but should in no way deter you from taking on a challenging project (adapted from Lyon 27). Depending on your field of study, some of these might be more relevant to you than others, but nonetheless useful to reiterate and pose to yourself.

- Do you have sufficient enthusiasm for a project that may span years?

- Will publication of your book satisfy your long-term career goals?

- Do you have enough material for such a long project and do you have the background knowledge and qualifications required for it?

- Is your book idea better than or different from other books on the subject? Does the idea spark enthusiasm not just in yourself but others in your field, friends, or prospective readers?

- Are you willing to acquire any lacking skills, such as, writing style, specific terminology and knowledge on that field for this project? Will it fit into your career and life at the time or will you not have the time to engage in such extensive research?

Essential elements of a book proposal

Your book proposal should include the following elements:

- Your proposal requires the consideration of the timing and potential for sale as well as its potential for subsidiary rights.

- It needs to include an outline of approximately one paragraph to one page of prose (Larsen 6) as well as one sample chapter to showcase the style and quality of your writing.

- You should also include the resources you need for the completion of the book and a biographical statement (“About the Author”).

- Your proposal must contain your credentials and expertise, preferably from previous publications on similar issues.

- A book proposal also provides you with the opportunity to include information such as a mission statement, a foreword by another authority, or special features—for instance, humor, anecdotes, illustrations, sidebars, etc.

- You must assess your ability to promote the book and know the market that you target in all its statistics.

The following proposal structure, as outlined by Peter E. Dunn for thesis and fellowship proposals, provides a useful guide to composing such a long proposal (Dunn, Peter E. “Proposal Writing.” Center for Instructional Excellence, Purdue University, 2007):

- Literature Review

- Identification of Problem

- Statement of Objectives

- Rationale and Significance

- Methods and Timeline

- Literature Cited

Most proposals for manuscripts range from thirty to fifty pages and, apart from the subject hook, book information (length, title, selling handle), markets for your book, and the section about the author, all the other sections are optional. Always anticipate and answer as many questions by editors as possible, however.

Finally, include the best chapter possible to represent your book's focus and style. Until an agent or editor advises you to do otherwise, follow your book proposal exactly without including something that you might not want to be part of the book or improvise on possible expected recommendations.

Publishers expect to acquire the book's primary rights, so that they can sell it in an adapted or condensed form as well. Mentioning any subsidiary rights, such as translation opportunities, performance and merchandising rights, or first-serial rights, will add to the editor's interest in buying your book. It is enticing to publishers to mention your manuscript's potential to turn into a series of books, although they might still hesitate to buy it right away—at least until the first one has been a successful endeavor.

The sample chapter

Since editors generally expect to see about one-tenth of a book, your sample chapter's length should reflect that in these building blocks of your book. The chapter should reflect your excitement and the freshness of the idea as well as surprise editors, but do not submit part of one or more chapters. Always send a chapter unless your credentials are impeccable due to prior publications on the subject. Do not repeat information in the sample chapter that will be covered by preceding or following ones, as the outline should be designed in such a way as to enable editors to understand the context already.

How to make your proposal stand out

Depending on the subject of your book, it is advisable to include illustrations that exemplify your vision of the book and can be included in the sample chapter. While these can make the book more expensive, it also increases the salability of the project. Further, you might consider including outstanding samples of your published work, such as clips from periodicals, if they are well-respected in the field. Thirdly, cover art can give your potential publisher a feel for your book and its marketability, especially if your topic is creative or related to the arts.

In addition, professionally formatting your materials will give you an edge over sloppy proposals. Proofread the materials carefully, use consistent and carefully organized fonts, spacing, etc., and submit your proposal without staples; rather, submit it in a neat portfolio that allows easy access and reassembling. However, check the submission guidelines first, as most proposals are submitted digitally. Finally, you should try to surprise editors and attract their attention. Your hook, however, should be imaginative but inexpensive (you do not want to bribe them, after all). Make sure your hook draws the editors to your book proposal immediately (Adapted from Larsen 154-60).

How to Write An Effective Project Narrative

This post offers actionable tips and advice for organizing, brainstorming, writing, and editing project narratives.

A project narrative is a common component of a grant application or proposal. It defines a project’s scope and purpose, and it explains how it will be executed. Effective project narratives are succinct, organized, and written in clear, direct language. Your goal is to explain your project so well that a reader understands the breadth of the project and is convinced of its value.

This post, authored by Madeleine Cutrona, NYFA Coach and Senior Program Officer, NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship , offers suggestions for organizing, brainstorming, writing, and editing your project narrative. Read on for advice on how to write a successful project narrative.

Step 1: Use a Working Document

Consider your project narrative a working document or an ongoing draft that you occasionally update and can use as a point of departure for future opportunities.

With each application and proposal, you will describe your project to different stakeholders (ex. funders, collaborators, participants, partner organizations, etc). In order to speak to these different audiences, you can tweak your project narrative for each audience. Similarly, since your project will no doubt evolve over time, keeping a draft project narrative tracks your project’s evolution over time.

Step 2: Prepare to Write

Writing an effective project narrative is all about the art of written communication, and this process can be challenging. Here are specific strategies to help you transform your expansive ideas into a detailed project narrative.

- Brain Dump: Get alllllllllllllll your ideas out there. Write down every idea that comes into your head, stream-of-consciousness-style. No idea is too small, too silly, or too random to include. The goal of this exercise is to clear your mind (and future writing!) of clutter. There is absolutely no need to self-edit, revise, or in any way perfect your writing during a brain dump. If you’re new to this process, begin by setting a timer for five or ten minutes. With your thoughts securely jotted down, you can then close that document or put your paper in the drawer. You are now ready to write! You also have a treasure trove of ideas to come back to in the future, should you need inspiration.

- What activities does the project consist of?

- When will the project happen? When did it begin? When did it end? What are milestones in the project timeline?

- Who is leading the team? Who is on the team and what is their experience?

- Where does the project take place?

- Why is this project relevant at this time? Why are you (and/or your team) the right person to lead this project right now?

- How will you organize the project activities? How will the team work together?

- Summary: A concise overview of your project, highlighting the most important information.

- Goals: A long-term achievable outcome for your project. This SMART goals template is a useful format.

- Objectives: Specific, measurable steps to achieve the overall goals.

- Timeline: When does the project begin? What milestones will mark the progression of your project? When does your project conclude?

- Leadership: How is the team prepared to meet the challenges of the project, such as new content or processes?

- Impact: Identifying the impact of your project at the start of your project can help you write more detailed mechanics about your project operations. How will the world be different after your project concludes? Identify what the beginning, middle, and end (impact) of your work will be.

- Evaluation/Follow-up: How will you assess your project’s success? This section should align with the goals of your project.

Step 3: Write It…Finally!

With your main ideas recorded, it’s now time to put it all together and formally write your narrative.

- Build upon the framework of your outline by adding specific examples.

- Describe your project with language that allows your reader to see your project unfold in their mind’s eye.

- Write for a general audience, refraining from using technical language beyond what might be known/read by your audience.

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) shares Sample Applications from a variety of disciplines on their website . These are examples of funded projects/programs from arts organizations.

Step 4: Review

Find a trusted colleague or friend to read your project narrative for you. This is really important. Working with an outside reader is especially helpful for catching details about your project that you might have overlooked because you know your project so well. To help make the most of your review session:

- Ask a reader to identify the five W’s of your project after reading and see if they align with your own list. If they do not, you know what areas of your application are unclear.

- Ask a reader what questions they have about your project after reading the proposal. You will learn what you need to clarify in your narrative.

Step 5: Customize and Submit!

The purpose of having a working document is preparing project narrative text that you can easily adapt to specific applications. Although you will ultimately need to customize your narrative to fit your project when you submit the narrative with a grant or residency proposal, you can write for an idealized audience at this stage in a single document. When you later apply for a grant or to a residency to complete a project the institution you are applying to might have an existing form for you to complete. At this stage you can pull from your draft document.

– Madeleine Cutrona, Senior Program Officer, NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship

To book a session with Madeleine or any of our other coaches, click here . If you have questions about this program, contact [email protected] .

NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship’s quarterly no-fee application deadlines are March 31, June 30, September 30, and December 31. We also accept Out-of-Cycle Review applications year-round. Reach out to us at [email protected] for more information. Sign up for NYFA’s free bi-weekly newsletter to receive updates on future programs.

Sign up for NYFA’s free bi-weekly newsletter to receive updates on future programs.

Donate to NYFA

- Donation amount: Select donate button or input other amount is required

- Acknowledge as: Input is required

- First name: Input is required

- Last name: Input is required

- Email: Input is required

- Email: Must include '@' symbol

- Email: Please enter a part following '@'

- Country: Selection is required

- Street: Input is required

- City: Input is required

- State: Selection is required

- Zip: Input is required

- Address: Input is required

- reCaptcha is required

insert message here

New York Foundation for the Arts 29 W. 38th Street, 9th Floor New York, NY 10018

Terms & Conditions | Privacy Policy | Site Map

How to Write a Perfect Narrative Essay (Step-by-Step)

By Status.net Editorial Team on October 17, 2023 — 10 minutes to read

- Understanding a Narrative Essay Part 1

- Typical Narrative Essay Structure Part 2

- Narrative Essay Template Part 3

- Step 1. How to Choose Your Narrative Essay Topic Part 4

- Step 2. Planning the Structure Part 5

- Step 3. Crafting an Intriguing Introduction Part 6

- Step 4. Weaving the Narrative Body Part 7

- Step 5. Creating a Conclusion Part 8

- Step 6. Polishing the Essay Part 9

- Step 7. Feedback and Revision Part 10

Part 1 Understanding a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is a form of writing where you share a personal experience or tell a story to make a point or convey a lesson. Unlike other types of essays, a narrative essay aims to engage your audience by sharing your perspective and taking them on an emotional journey.

- To begin, choose a meaningful topic . Pick a story or experience that had a significant impact on your life, taught you something valuable, or made you see the world differently. You want your readers to learn from your experiences, so choose something that will resonate with others.

- Next, create an outline . Although narrative essays allow for creative storytelling, it’s still helpful to have a roadmap to guide your writing. List the main events, the characters involved, and the settings where the events took place. This will help you ensure that your essay is well-structured and easy to follow.

- When writing your narrative essay, focus on showing, not telling . This means that you should use descriptive language and vivid details to paint a picture in your reader’s mind. For example, instead of stating that it was a rainy day, describe the sound of rain hitting your window, the feeling of cold wetness around you, and the sight of puddles forming around your feet. These sensory details will make your essay more engaging and immersive.

- Another key aspect is developing your characters . Give your readers an insight into the thoughts and emotions of the people in your story. This helps them connect with the story, empathize with the characters, and understand their actions. For instance, if your essay is about a challenging hike you took with a friend, spend some time describing your friend’s personality and how the experience impacted their attitude or feelings.

- Keep the pace interesting . Vary your sentence lengths and structures, and don’t be afraid to use some stylistic devices like dialogue, flashbacks, and metaphors. This adds more depth and dimension to your story, keeping your readers engaged from beginning to end.

Part 2 Typical Narrative Essay Structure

A narrative essay typically follows a three-part structure: introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Introduction: Start with a hook to grab attention and introduce your story. Provide some background to set the stage for the main events.

- Body: Develop your story in detail. Describe scenes, characters, and emotions. Use dialogue when necessary to provide conversational elements.

- Conclusion: Sum up your story, revealing the lesson learned or the moral of the story. Leave your audience with a lasting impression.

Part 3 Narrative Essay Template

- 1. Introduction : Set the scene and introduce the main characters and setting of your story. Use descriptive language to paint a vivid picture for your reader and capture their attention.

- Body 2. Rising Action : Develop the plot by introducing a conflict or challenge that the main character must face. This could be a personal struggle, a difficult decision, or an external obstacle. 3. Climax : This is the turning point of the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the main character must make a critical decision or take action. 4. Falling Action : Show the consequences of the main character’s decision or action, and how it affects the rest of the story. 5. Resolution : Bring the story to a satisfying conclusion by resolving the conflict and showing how the main character has grown or changed as a result of their experiences.

- 6. Reflection/Conclusion : Reflect on the events of the story and what they mean to you as the writer. This could be a lesson learned, a personal realization, or a message you want to convey to your reader.

Part 4 Step 1. How to Choose Your Narrative Essay Topic

Brainstorming ideas.

Start by jotting down any ideas that pop into your mind. Think about experiences you’ve had, stories you’ve heard, or even books and movies that have resonated with you. Write these ideas down and don’t worry too much about organization yet. It’s all about getting your thoughts on paper.

Once you have a list, review your ideas and identify common themes or connections between them. This process should help you discover potential topics for your narrative essay.

Narrowing Down the Choices

After brainstorming, you’ll likely end up with a few strong contenders for your essay topic. To decide which topic is best, consider the following:

- Relevance : Is the topic meaningful for your audience? Will they be able to connect with it on a personal level? Consider the purpose of your assignment and your audience when choosing your topic.

- Detail : Do you have enough specific details to craft a vivid story? The more detail you can recall about the event, the easier it’ll be to write a compelling narrative.

- Emotional impact : A strong narrative essay should evoke emotions in your readers. Choose a topic that has the potential to elicit some emotional response from your target audience.

After evaluating your potential topics based on these criteria, you can select the one that best fits the purpose of your narrative essay.

Part 5 Step 2. Planning the Structure

Creating an outline.

Before you start writing your narrative essay, it’s a great idea to plan out your story. Grab a piece of paper and sketch out a rough outline of the key points you want to cover. Begin with the introduction, where you’ll set the scene and introduce your characters. Then, list the major events of your story in chronological order, followed by the climax and resolution. Organizing your ideas in an outline will ensure your essay flows smoothly and makes sense to your readers.

Detailing Characters, Settings, and Events

Taking time to flesh out the characters, settings, and events in your story will make it more engaging and relatable. Think about your main character’s background, traits, and motivations. Describe their appearance, emotions, and behavior in detail. This personal touch will help your readers connect with them on a deeper level.

Also, give some thought to the setting – where does the story take place? Be sure to include sensory details that paint a vivid picture of the environment. Finally, focus on the series of events that make up your narrative. Are there any twists and turns, or surprising moments? Address these in your essay, using vivid language and engaging storytelling techniques to captivate your readers.

Writing the Narrative Essay

Part 6 step 3. crafting an intriguing introduction.

To start your narrative essay, you’ll want to hook your reader with an interesting and engaging opening. Begin with a captivating sentence or question that piques curiosity and captures attention. For example, “Did you ever think a simple bus ride could change your life forever?” This kind of opening sets the stage for a compelling, relatable story. Next, introduce your main characters and provide a bit of context to help your readers understand the setting and background of the story.

Part 7 Step 4. Weaving the Narrative Body

The body of your essay is where your story unfolds. Here’s where you’ll present a series of events, using descriptive language and vivid details.

Remember to maintain a strong focus on the central theme or main point of your narrative.

Organize your essay chronologically, guiding your reader through the timeline of events.

As you recount your experience, use a variety of sensory details, such as sounds, smells, and tastes, to immerse your reader in the moment. For instance, “The smell of freshly brewed coffee filled the room as my friends and I excitedly chattered about our upcoming adventure.”

Take advantage of dialogue to bring your characters to life and to reveal aspects of their personalities. Incorporate both internal and external conflicts, as conflict plays a crucial role in engaging your reader and enhancing the narrative’s momentum. Show the evolution of your characters and how they grow throughout the story.

Part 8 Step 5. Creating a Conclusion

Finally, to write a satisfying conclusion, reflect on the narrative’s impact and how the experience has affected you or your characters. Tie the narrative’s events together and highlight the lessons learned, providing closure for the reader.

Avoid abruptly ending your story, because that can leave the reader feeling unsatisfied. Instead, strive to create a sense of resolution and demonstrate how the events have changed the characters’ perspectives or how the story’s theme has developed.

For example, “Looking back, I realize that the bus ride not only changed my perspective on friendship, but also taught me valuable life lessons that I carry with me to this day.”

Part 9 Step 6. Polishing the Essay

Fine-tuning your language.

When writing a narrative essay, it’s key to choose words that convey the emotions and experiences you’re describing. Opt for specific, vivid language that creates a clear mental image for your reader. For instance, instead of saying “The weather was hot,” try “The sun scorched the pavement, causing the air to shimmer like a mirage.” This gives your essay a more engaging and immersive feeling.

Editing for Clarity and Concision

As you revise your essay, keep an eye out for redundancies and unnecessary words that might dilute the impact of your story. Getting to the point and using straightforward language can help your essay flow better. For example, instead of using “She was walking in a very slow manner,” you can say, “She strolled leisurely.” Eliminate filler words and phrases, keeping only the most pertinent information that moves your story forward.

Proofreading for Typos

Finally, proofread your essay carefully to catch any typos, grammatical errors, or punctuation mistakes. It’s always a good idea to have someone else read it as well, as they might catch errors you didn’t notice. Mistakes can be distracting and may undermine the credibility of your writing, so be thorough with your editing process.

Part 10 Step 7. Feedback and Revision

Gathering feedback.

After you’ve written the first draft of your narrative essay, it’s time to gather feedback from friends, family, or colleagues. Share your essay with a few trusted people who can provide insights and suggestions for improvement. Listen to their thoughts and be open to constructive criticism. You might be surprised by the different perspectives they offer, which can strengthen your essay.

Iterating on the Draft

Once you have collected feedback, it’s time to revise and refine your essay. Address any issues or concerns raised by your readers and incorporate their suggestions. Consider reorganizing your story’s structure, clarifying your descriptions, or adding more details based on the feedback you received.

As you make changes, continue to fine-tune your essay to ensure a smooth flow and a strong narrative. Don’t be afraid to cut out unnecessary elements or rework parts of your story until it’s polished and compelling.

Revision is a crucial part of the writing process, and taking the time to reflect on feedback and make improvements will help you create a more engaging and impactful narrative essay.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can i create an engaging introduction.

Craft an attention-grabbing hook with a thought-provoking question, an interesting fact, or a vivid description. Set the stage for your story by introducing the time, place, and context for the events. Creating tension or raising curiosity will make your readers eager to learn more.

What strategies help develop strong characters?

To develop strong characters, consider the following:

- Give your characters distinct traits, strengths, and weaknesses.

- Provide a backstory to explain their actions and motivations.

- Use dialogue to present their personality, emotions, and relationships.

- Show how they change or evolve throughout your story.

How can I make my story flow smoothly with transitions?

Smooth transitions between scenes or events can create a more coherent and easy-to-follow story. Consider the following tips to improve your transitions:

- Use words and phrases like “meanwhile,” “later that day,” or “afterward” to signify changes in time.

- Link scenes with a common theme or element.

- Revisit the main characters or setting to maintain continuity.

- Introduce a twist or an unexpected event that leads to the next scene.

What are some tips for choosing a great narrative essay topic?

To choose an engaging narrative essay topic, follow these tips:

- Pick a personal experience or story that holds significance for you.

- Consider a challenge or a turning point you’ve faced in your life.

- Opt for a topic that will allow you to share emotions and lessons learned.

- Think about what your audience would find relatable, intriguing, or inspiring.

How do I wrap up my narrative essay with a strong conclusion?

A compelling conclusion restates the main events and highlights any lessons learned or growth in your character. Try to end on a thought-provoking note or leave readers with some food for thought. Finally, make sure your conclusion wraps up your story neatly and reinforces its overall message.

- How to Write a Perfect Project Plan? [The Easy Guide]

- How to Write a Thoughtful Apology Letter (Inspiring Examples)

- 5 Main Change Management Models: ADKAR vs Kubler Ross vs McKinsey 7S vs Lewin's vs Kotter’s 8 Step

- How to Write a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP)

- How to Write an Effective Performance Review (Essential Steps)

- How to Write Scope of Work - 7 Necessary Steps and 6 Best Practices

Narrative Essay with Tips - a Detailed Guide

Defining What Is a Narrative Essay

We can explain a narrative essay definition as a piece of writing that tells a story. It's like a window into someone's life or a page torn from a diary. Similarly to a descriptive essay, a narrative essay tells a story, rather than make a claim and use evidence. It can be about anything – a personal experience, a childhood memory, a moment of triumph or defeat – as long as it's told in a way that captures the reader's imagination.

You might ask - 'which sentence most likely comes from a narrative essay?'. Let's take this for example: 'I could hear the waves crashing against the shore, their rhythm a soothing lullaby that carried me off to sleep.' You could even use such an opening for your essay when wondering how to start a narrative essay.

To further define a narrative essay, consider it storytelling with a purpose. The purpose of a narrative essay is not just to entertain but also to convey a message or lesson in first person. It's a way to share your experiences and insights with others and connect with your audience. Whether you're writing about your first love, a harrowing adventure, or a life-changing moment, your goal is to take the reader on a journey that will leave them feeling moved, inspired, or enlightened.

So if you're looking for a way to express yourself creatively and connect with others through your writing, try your hand at a narrative essay. Who knows – you might just discover a hidden talent for storytelling that you never knew you had!

Meanwhile, let's delve into the article to better understand this type of paper through our narrative essay examples, topic ideas, and tips on constructing a perfect essay.

Types of Narrative Essays

If you were wondering, 'what is a personal narrative essay?', know that narrative essays come in different forms, each with a unique structure and purpose. Regardless of the type of narrative essay, each aims to transport the reader to a different time and place and to create an emotional connection between the reader and the author's experiences. So, let's discuss each type in more detail:

- A personal narrative essay is based on one's unique experience or event. Personal narrative essay examples include a story about overcoming a fear or obstacle or reflecting on a particularly meaningful moment in one's life.

- A fictional narrative is a made-up story that still follows the basic elements of storytelling. Fictional narratives can take many forms, from science fiction to romance to historical fiction.

- A memoir is similar to personal narratives but focuses on a specific period or theme in a person's life. Memoirs might be centered around a particular relationship, a struggle with addiction, or a cultural identity. If you wish to describe your life in greater depth, you might look at how to write an autobiography .

- A literacy narrative essay explores the writer's experiences with literacy and how it has influenced their life. The essay typically tells a personal story about a significant moment or series of moments that impacted the writer's relationship with reading, writing, or communication.

You might also be interested in discovering 'HOW TO WRITE AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY'

Pros and Cons of Narrative Writing

Writing a narrative essay can be a powerful tool for self-expression and creative storytelling, but like any form of writing, it comes with its own set of pros and cons. Let's explore the pros and cons of narrative writing in more detail, helping you to decide whether it's the right writing style for your needs.

- It can be a powerful way to convey personal experiences and emotions.

- Allows for creative expression and unique voice

- Engages the reader through storytelling and vivid details

- It can be used to teach a lesson or convey a message.

- Offers an opportunity for self-reflection and growth

- It can be challenging to balance personal storytelling with the needs of the reader

- It may not be as effective for conveying factual information or arguments

- It may require vulnerability and sharing personal details that some writers may find uncomfortable

- It can be subjective, as the reader's interpretation of the narrative may vary

If sharing your personal stories is not your cup of tea, you can buy essays online from our expert writers, who will customize the paper to your particular writing style and tone.

20 Excellent Narrative Essay Topics and How to Choose One

Choosing a good topic among many narrative essay ideas can be challenging, but some tips can help you make the right choice. Here are some original and helpful tips on how to choose a good narrative essay topic:

- Consider your own experiences: One of the best sources of inspiration for a narrative essay is your own life experiences. Consider moments that have had a significant impact on you, whether they are positive or negative. For example, you could write about a memorable trip or a challenging experience you overcame.

- Choose a topic relevant to your audience: Consider your audience and their interests when choosing a narrative essay topic. If you're writing for a class, consider what topics might be relevant to the course material. If you're writing for a broader audience, consider what topics might be interesting or informative to them.

- Find inspiration in literature: Literature can be a great source of inspiration for a narrative essay. Consider the books or stories that have had an impact on you, and think about how you can incorporate elements of them into your own narrative. For example, you could start by using a title for narrative essay inspired by the themes of a favorite novel or short story.

- Focus on a specific moment or event: Most narrative essays tell a story, so it's important to focus on a specific moment or event. For example, you could write a short narrative essay about a conversation you had with a friend or a moment of realization while traveling.

- Experiment with different perspectives: Consider writing from different perspectives to add depth and complexity to your narrative. For example, you could write about the same event from multiple perspectives or explore the thoughts and feelings of a secondary character.

- Use writing prompts: Writing prompts can be a great source of inspiration if you struggle to develop a topic. Consider using a prompt related to a specific theme, such as love, loss, or growth.

- Choose a topic with rich sensory details: A good narrative essay should engage the senses and create a vivid picture in the reader's mind. Choose a topic with rich sensory details that you can use to create a vivid description. For example, you could write about a bustling city's sights, sounds, and smells.

- Choose a topic meaningful to you: Ultimately, the best narrative essays are meaningful to the writer. Choose a topic that resonates with you and that you feel passionate about. For example, you could write about a personal goal you achieved or a struggle you overcame.

Here are some good narrative essay topics for inspiration from our experts:

- A life-changing event that altered your perspective on the world

- The story of a personal accomplishment or achievement

- An experience that tested your resilience and strength

- A time when you faced a difficult decision and how you handled it

- A childhood memory that still holds meaning for you

- The impact of a significant person in your life

- A travel experience that taught you something new

- A story about a mistake or failure that ultimately led to growth and learning

- The first day of a new job or school

- The story of a family tradition or ritual that is meaningful to you

- A time when you had to confront a fear or phobia

- A memorable concert or music festival experience

- An experience that taught you the importance of communication or listening

- A story about a time when you had to stand up for what you believed in

- A time when you had to persevere through a challenging task or project

- A story about a significant cultural or societal event that impacted your life

- The impact of a book, movie, or other work of art on your life

- A time when you had to let go of something or someone important to you

- A memorable encounter with a stranger that left an impression on you

- The story of a personal hobby or interest that has enriched your life

Narrative Format and Structure

The narrative essay format and structure are essential elements of any good story. A well-structured narrative can engage readers, evoke emotions, and create lasting memories. Whether you're writing a personal essay or a work of fiction, the following guidelines on how to write a narrative essay can help you create a compelling paper:

- Introduction : The introduction sets the scene for your story and introduces your main characters and setting. It should also provide a hook to capture your reader's attention and make them want to keep reading. When unsure how to begin a narrative essay, describe the setting vividly or an intriguing question that draws the reader in.

- Plot : The plot is the sequence of events that make up your story. It should have a clear beginning, middle, and end, with each part building on the previous one. The plot should also have a clear conflict or problem the protagonist must overcome.

- Characters : Characters are the people who drive the story. They should be well-developed and have distinct personalities and motivations. The protagonist should have a clear goal or desire, and the antagonist should provide a challenge or obstacle to overcome.

- Setting : The setting is the time and place the story takes place. It should be well-described and help to create a mood or atmosphere that supports the story's themes.

- Dialogue : Dialogue is the conversation between characters. It should be realistic and help to reveal the characters' personalities and motivations. It can also help to move the plot forward.

- Climax : The climax is the highest tension or conflict point in the story. It should be the turning point that leads to resolving the conflict.

- Resolution : The resolution is the end of the story. It should provide a satisfying conclusion to the conflict and tie up any loose ends.

Following these guidelines, you can create a narrative essay structure that engages readers and leaves a lasting impression. Remember, a well-structured story can take readers on a journey and make them feel part of the action.

Want to Be Like an Expert Writer?

Order now and let our narrative essay service turn your experiences into a captivating and unforgettable tale

Narrative Essay Outline

Here is a detailed narrative essay outline from our custom term paper writing :

Introduction

A. Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing statement, question, or anecdote that introduces the topic and draws the reader in. Example: 'The sun beat down on my skin as I stepped onto the stage, my heart pounding with nervous excitement.'

B. Background information: Provide context for the story, such as the setting or the characters involved. Example: 'I had been preparing for this moment for weeks, rehearsing my lines and perfecting my performance for the school play.'

C. Thesis statement: State the essay's main point and preview the events to come. Example: 'This experience taught me that taking risks and stepping outside my comfort zone can lead to unexpected rewards and personal growth.'

Body Paragraphs

A. First event: Describe the first event in the story, including details about the setting, characters, and actions. Example: 'As I delivered my first lines on stage, I felt a rush of adrenaline and a sense of pride in my hard work paying off.'

B. Second event: Describe the second event in the story, including how it builds on the first event and moves the story forward. Example: 'As the play progressed, I became more comfortable in my role and connecting with the other actors on stage.'

C. Turning point: Describe the turning point in the story, when something unexpected or significant changes the course of events. Example: 'In the final act, my character faced a difficult decision that required me to improvise and trust my instincts.'

D. Climax: Describe the story's climax, the highest tension or conflict point. Example: 'As the play reached its climax, I delivered my final lines with confidence and emotion, feeling a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment.'

A. Restate thesis: Summarize the essay's main point and how the events in the story support it. Example: 'Through this experience, I learned that taking risks and pushing past my comfort zone can lead to personal growth and unexpected rewards.'

B. Reflection: Reflect on the significance of the experience and what you learned from it. Example: 'Looking back, I realize that this experience not only taught me about acting and performance but also about the power of perseverance and self-belief.'

C. Call to action: if you're still wondering how to write an essay conclusion , consider ending it with a call to action or final thought that leaves the reader with something to consider or act on. Example: 'I encourage everyone to take risks and embrace new challenges because you never know what kind of amazing experiences and growth they may lead to.

You might also be interested in getting detailed info on 'HOW TO WRITE AN ESSAY CONCLUSION'

Narrative Essay Examples

Are you looking for inspiration for your next narrative essay? Look no further than our narrative essay example. Through vivid storytelling and personal reflections, this essay takes the reader on a journey of discovery and leaves them with a powerful lesson about the importance of compassion and empathy. Use this sample from our expert essay writer as a guide for crafting your own narrative essay, and let your unique voice and experiences shine through.

Narrative Essay Example for College

College professors search for the following qualities in their students:

- the ability to adapt to different situations,

- the ability to solve problems creatively,

- and the ability to learn from mistakes.

Your work must demonstrate these qualities, regardless of whether your narrative paper is a college application essay or a class assignment. Additionally, you want to demonstrate your character and creativity. Describe a situation where you have encountered a problem, tell the story of how you came up with a unique approach to solving it, and connect it to your field of interest. The narrative can be exciting and informative if you present it in such fashion.

Narrative Essay Example for High School

High school is all about showing that you can make mature choices. You accept the consequences of your actions and retrieve valuable life lessons. Think of an event in which you believe your actions were exemplary and made an adult choice. A personal narrative essay example will showcase the best of your abilities. Finally, use other sources to help you get the best results possible. Try searching for a sample narrative essay to see how others have approached it.

Final Words

So now that you know what is a narrative essay you might want to produce high-quality paper. For that let our team of experienced writers help. Our research paper writing service offers a range of professional writing services that cater to your unique needs and requirements, from narrative essays to medical personal statement , also offering dissertation help and more.

With our flexible pricing options and fast turnaround times, you can trust that you'll receive great value for your investment. Contact us today to learn more about how we can help you succeed in your academic writing journey.

Unlock Your Potential with Our Essays!

Order now and take the first step towards achieving your academic goals

What Is A Narrative Essay?

How to start a narrative essay, how to write a good narrative essay, related articles.

.webp)

- Scriptwriting

How to Write a Narrative Essay — A Step-by-Step Guide

N arrative essays are important papers most students have to write. But how does one write a narrative essay? Fear not, we’re going to show you how to write a narrative essay by breaking down a variety of narrative writing strategies. By the end, you’ll know why narrative essays are so important – and how to write your own.

How to Write a Narrative Essay Step by Step

Background on narrative essays.

Narrative essays are important assignments in many writing classes – but what is a narrative essay? A narrative essay is a prose-written story that’s focused on the commentary of a central theme .

Narrative essays are generally written in the first-person POV , and are usually about a topic that’s personal to the writer.

Everything in a narrative essay should take place in an established timeline, with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

In simplest terms, a narrative essay is a personal story. A narrative essay can be written in response to a prompt or as an independent exercise.

We’re going to get to tips and tricks on how to write a narrative essay in a bit, but first let’s check out a video on “story.”

How to Start a Narrative Essay • What is a Story? by Mr. Kresphus

In some regards, any story can be regarded as a personal story, but for the sake of this article, we’re going to focus on prose-written stories told in the first-person POV.

How to Start a Narrative Essay

Responding to prompts.

Many people wonder about how to start a narrative essay. Well, if you’re writing a narrative essay in response to a prompt, then chances are the person issuing the prompt is looking for a specific answer.

For example: if the prompt states “recount a time you encountered a challenge,” then chances are the person issuing the prompt wants to hear about how you overcame a challenge or learned from it.

That isn’t to say you have to respond to the prompt in one way; “overcoming” or “learning” from a challenge can be constituted in a variety of ways.

For example, you could structure your essay around overcoming a physical challenge, like an injury or disability. Or you could structure your essay around learning from failure, such as losing at a sport or performing poorly on an important exam.

Whatever it is, you must show that the challenge forced you to grow.

Maturation is an important process – and an essential aspect of narrative essays... of course, there are exceptions to the rule; lack of maturation is a prescient theme in narrative essays too; although that’s mostly reserved for experienced essay writers.

So, let’s take a look at how you might respond to a series of narrative essay prompts:

How successful are you?

This prompt begs the writer to impart humility without throwing a pity party. I would respond to this prompt by demonstrating pride in what I do while offering modesty. For example: “I have achieved success in what I set out to do – but I still have a long way to go to achieve my long-term goals.”

Who is your role model?

“My role model is [Blank] because ” is how you should start this narrative essay. The “because” is the crux of your essay. For example, I’d say “Bill Russell is my role model because he demonstrated graceful resolve in the face of bigotry and discrimination.

Do you consider yourself spiritual?

For this prompt, you should explain how you came to the conclusion of whether or not you consider yourself a spiritual person. Of course, prompt-givers will differ on how much they want you to freely express. For example: if the prompt-giver is an employee at an evangelizing organization, then they probably want to see that you’re willing to propagate the church’s agenda. Alternatively, if the prompt-giver is non-denominational, they probably want to see that you’re accepting of people from various spiritual backgrounds.

How to Write Narrative Essay

What makes a good narrative essay.

You don’t have to respond to a prompt to write a narrative essay. So, how do you write a narrative essay without a prompt? Well, that’s the thing… you can write a narrative essay about anything!

That’s a bit of a blessing and a curse though – on one hand it’s liberating to choose any topic you want; on the other, it’s difficult to narrow down a good story from an infinite breadth of possibilities.

In this next video, the team at Essay Pro explores why passion is the number one motivator for effective narrative essays.

How to Write a Narrative Essay Step by Step • Real Essay Examples by Essay Pro

So, before you write anything, ask yourself: “what am I passionate about?” Movies? Sports? Books? Games? Baking? Volunteering? Whatever it is, make sure that it’s something that demonstrates your individual growth . It doesn’t have to be anything major; take a video game for example: you could write a narrative essay about searching for a rare weapon with friends.

Success or failure, you’ll be able to demonstrate growth.

Here’s something to consider: writing a narrative essay around intertextuality. What is intertextuality ? Intertextuality is the relationship between texts, i.e., books, movies, plays, songs, games, etc. In other words, it’s anytime one text is referenced in another text.

For example, you could write a narrative essay about your favorite movie! Just make sure that it ultimately reflects back on yourself.

Narrative Writing Format

Structure of a narrative essay.

Narrative essays differ in length and structure – but there are some universal basics. The first paragraph of a narrative essay should always introduce the central theme. For example, if the narrative essay is about “a fond childhood memory,” then the first paragraph should briefly comment on the nature of the fond childhood memory.

In general, a narrative essay should have an introductory paragraph with a topic sentence (reiterating the prompt or basic idea), a brief commentary on the central theme, and a set-up for the body paragraphs.

The body paragraphs should make up the vast majority of the narrative essay. In the body paragraphs, the writer should essentially “build the story’s case.” What do I mean by “build the story’s case?”

Well, I mean that the writer should display the story’s merit; what it means, why it matters, and how it proves (or refutes) personal growth.

The narrative essay should always conclude with a dedicated paragraph. In the “conclusion paragraph,” the writer should reflect on the story.

Pro tip: conclusion paragraphs usually work best when the writer stays within the diegesis.

What is a Video Essay?

A video essay is a natural extension of a narrative essay; differentiated only by purpose and medium. In our next article, we’ll explain what a video essay is, and why it’s so important to media criticism. By the end, you’ll know where to look for video essay inspiration.

Up Next: The Art of Video Analysis →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Film Distribution — The Ultimate Guide for Filmmakers

- What is a Fable — Definition, Examples & Characteristics

- Whiplash Script PDF Download — Plot, Characters and Theme

- What Is a Talking Head — Definition and Examples

- What is Blue Comedy — Definitions, Examples and Impact

- 2 Pinterest

Product Overview

- Donor Database Use a CRM built for nonprofits.

- Marketing & Engagement Reach out and grow your donor network.

- Online Giving Enable donors to give from anywhere.

- Reporting & Analytics Easily generate accurate reports.

- Volunteer Management Volunteer experiences that inspire.

- Bloomerang Payments Process payments seamlessly.

- Mobile App Get things done while on the go.

- Data Management Gather and update donor insights.

- Integrations

- Professional Services & Support

- API Documentation

Learn & Connect

- Articles Read the latest from our community of fundraising professionals.

- Guides & Templates Download free guides and templates.

- Webinars & Events Watch informational webinars and attend industry events.

- DEI Resources Get DEI resources from respected and experienced leaders.

- Ask An Expert Real fundraising questions, answered.

- Bloomerang Academy Learn from our team of fundraising and technology experts.

- Consultant Directory

- Comms Audit Tool

- Donor Retention Calculator

- Compare Bloomerang

- Volunteer Management

How to Write a Proposal Narrative

This session will cover everything you need to know about writing a proposal narrative! We’ll cover the most frequently requested information by funders, explore what they’re REALLY looking for, and examine some examples.

In the grant world, funders tend to request the same key areas of information within a grant proposal. Through this webinar, participants will explore how to write a compelling proposal narrative, including their:

- Organizational Background

- Need Statement

- Goals and Objectives

- Methodology

- Impact & Evaluation

- Sustainability

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to write a narrative essay [Updated 2023]

A narrative essay is an opportunity to flex your creative muscles and craft a compelling story. In this blog post, we define what a narrative essay is and provide strategies and examples for writing one.

What is a narrative essay?

Similarly to a descriptive essay or a reflective essay, a narrative essay asks you to tell a story, rather than make an argument and present evidence. Most narrative essays describe a real, personal experience from your own life (for example, the story of your first big success).

Alternately, your narrative essay might focus on an imagined experience (for example, how your life would be if you had been born into different circumstances). While you don’t need to present a thesis statement or scholarly evidence, a narrative essay still needs to be well-structured and clearly organized so that the reader can follow your story.

When you might be asked to write a narrative essay

Although less popular than argumentative essays or expository essays, narrative essays are relatively common in high school and college writing classes.

The same techniques that you would use to write a college essay as part of a college or scholarship application are applicable to narrative essays, as well. In fact, the Common App that many students use to apply to multiple colleges asks you to submit a narrative essay.

How to choose a topic for a narrative essay

When you are asked to write a narrative essay, a topic may be assigned to you or you may be able to choose your own. With an assigned topic, the prompt will likely fall into one of two categories: specific or open-ended.

Examples of specific prompts:

- Write about the last vacation you took.

- Write about your final year of middle school.

Examples of open-ended prompts:

- Write about a time when you felt all hope was lost.

- Write about a brief, seemingly insignificant event that ended up having a big impact on your life.

A narrative essay tells a story and all good stories are centered on a conflict of some sort. Experiences with unexpected obstacles, twists, or turns make for much more compelling essays and reveal more about your character and views on life.

If you’re writing a narrative essay as part of an admissions application, remember that the people reviewing your essay will be looking at it to gain a sense of not just your writing ability, but who you are as a person.

In these cases, it’s wise to choose a topic and experience from your life that demonstrates the qualities that the prompt is looking for, such as resilience, perseverance, the ability to stay calm under pressure, etc.