Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 June 2024

From poverty to prosperity: assessing of sustainable poverty reduction effect of “welfare-to-work” in Chinese counties

- Feng Lan 1 , 2 ,

- Weichao Xu 1 ,

- Weizeng Sun 3 &

- Xiaonan Zhao 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 758 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

374 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Social policy

The “welfare-to-work” program is a comprehensive supportive policy in the 14th five-year plan period in China. In this paper, a systematical assessment of the long-run effectiveness of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction is of great significance to stimulate the internal impetus of people who are lifted out of poverty to achieve income growth and prosperity and promote regional economic development. Based on the data at the county (city) level in China from 2000 to 2019 and the sustainable development theory, in this paper, a county-relative poverty evaluation system was constructed. Besides, the double difference method was employed to evaluate the effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction and test its action mechanism. The findings are as follows: (1) the welfare-to-work policy has a significant poverty reduction effect and presents an inverted “U” shape. In addition, significant achievements have been made in “maintaining employment stability, ensuring income, strengthening skills, and supporting the economy” ; (2) the welfare-to-work policy boosts poverty reduction in counties through infrastructure construction, fiscal intervention, and financial tools; however, the financial tools play a positive role in poverty reduction in the northwest region and suppressed role in the southwest region, and has an insignificant effect in the central region; and (3) there are differences in the effect of poverty alleviation policies of the counties with different sustainable development levels, and the regions with higher development level have a stronger driving effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration

Reducing sectoral hard-to-abate emissions to limit reliance on carbon dioxide removal

Participatory action research

Introduction.

In 2021, China has scored a competitive victory in the fight against poverty. The final 98.99 million impoverished rural residents living under the current poverty line have all been lifted out of poverty. All 832 impoverished counties across the country and 128,000 impoverished villages have been removed from the poverty list Footnote 1 . Regional overall poverty has been resolved, which marks that China’s poverty governance has entered a new stage from absolute poverty to relative poverty, and from income poverty to multidimensional poverty. Relative poverty and multidimensional poverty have become new forms of poverty in China (Xu et al. 2021 ).

China’s anti-poverty focus has shifted from targeted poverty alleviation in absolute poor areas to comprehensive measures to promote high-quality development in relatively poor areas. The limited ability of the relatively poor population to obtain various livelihood capital also reduces the range of livelihood activities, and aggravates the livelihood risk and vulnerability. These factors will affect the economic development of relatively poor areas and the ability of rural populations to increase their income, and the long-term and complexity of this external environment also determine the long-term sustainability of consolidating and expanding the achievements of poverty alleviation.

Since ancient times, China has had the practice of “providing employment as a form of relief”. Since 1984, welfare-to-work, as a social and economic policy, has played an important role in poverty alleviation and development. Nowadays, with the transformation of China’s anti-poverty focus from the governance of absolute poverty to the high-quality development of relatively poor areas. The welfare-to-work policy not only has the attribute of poverty alleviation, but also has the overlapping role of social welfare and economic development, maximizing the release of the effects of the policy and activating the endogenous power of county economic development. On the one hand, it can be used to resist the impact of unfavorable factors and emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic, earthquakes, and tsunamis. Welfare-to-work policy can effectively play the role of “relief” in the process of flood control and post-disaster recovery. Compared with direct subsidies, welfare-to-work further mobilizes the enthusiasm of the broad masses of peasants to participate in the construction of rural public infrastructure and give full play to the investment of government for supporting agriculture. On the other hand, aiming at the employment needs of low-income groups, it provided timely payment of labor remuneration, and employment skills training. With compulsory and welfare means, it enhanced the capacity and subjective motivation of poverty-stricken people and low-income groups, thus encouraging them to participate in the competition.

Through data analysis, it was found that since the implementation of the “Welfare-to-work” policy in different regions, the effects have not been the same. For instance, during the implementation process, the phenomenon of emphasizing construction while neglecting relief has come into existence. Besides, influenced by the factors in regional development level, geographical restrictions, and population flow, the current labor force has lower quality and insufficient skills and thus achieves an unsatisfactory effect on employment and income growth. Although these areas have all been lifted out of poverty under the country’s targeted poverty alleviation policy, once impacted by external uncertainties, the obtained achievements in poverty alleviation will be irrevocably lost.

Therefore, what kind of impact does the sustainability of poverty reduction performance of the welfare-to-work policy have? Is there heterogeneity in the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy in different districts and counties? What is the role of a welfare-to-work policy in poverty reduction?

In this paper, a multi-dimensional relative poverty evaluation index system was constructed and the poverty reduction effect of the “welfare-to-work” policy was evaluated by the method of double difference (DID). In addition, the panel regression model was constructed to explore the mechanism of poverty reduction, and the Shapley method was used to quantify the contribution of mechanism variables to the poverty reduction effect. The study has several important findings. First of all, the cash-for-work policy effectively promotes poverty reduction in counties, and the higher the level of local development, the more significant the poverty reduction effect. The results are still valid after robustness testing. Second, policies promote poverty reduction at the county level through infrastructure construction, fiscal intervention, and financial instruments, but the contribution of different variables in different regions is different.

The remainder of this study is arranged as follows. Section 2 “Literature review and research hyptothesis” provides a literature review and research hypothesis. Section 3 “Research design” describes our empirical design. Section 4 “Analysis of empirical results” reports our empirical results and robustness tests. Section 5 “Test of action mechanism” reports the quantitative results of the mechanism of action. Finally, we provide a summary.

Literature review and research hypothesis

Evolution of welfare-to-work policy.

(1) From 1949 to 1983: the stage with a focus on disaster relief. At the First and Second National Civil Affairs work conference, it was emphasized that in disaster relief work, the principles of overcoming adversity through greater production, saving grain to tide over a lean year, holding on to mutual assistance, work relief, and supplementary necessary government relief should be encouraged. However, in accordance with the statement of the National Civil Affairs Conference in 1953, as the following continuous various projects in economic construction in China would inevitably attract the participation of victims, so the Welfare-to-work policy was removed from the disaster relief policy. At this stage, the planned economy system not only strengthened the government’s ability to organize disaster victims to carry out self-rescue action but also endowed the welfare-to-work policy and other policies with distinctive epochal features (Zhu, 2021 ). Specifically, the Welfare-to-work policy mainly focuses on the unemployed population and disaster relief. In addition, with efforts of supply optimization manpower allocation, and material and financial resources supply, the government organized victims in the form of mutual assistance and cooperation and built some engineering facilities in flood control, drainage, irrigation, and power generation, which have promoted the recovery of production and reconstruction of homes while providing disaster relief.

(2) From 1984 to 2000: the early stage of poverty alleviation and development. With the economic reform, poverty has been included as an important part of social and economic development. In 1984, China began to regard welfare-to-work as a means of alleviating poverty, and successively implemented six large-scale welfare-to-work programs, namely “grain and cotton cloth related welfare-to-work program”, “medium-and low-grade industrial products related welfare-to-work program”, “industrial products related welfare-to-work program”, “grain related welfare-to-work program”, “river control related welfare-to-work program” and “state-owned poor farms related welfare-to-work program”. In other words, since 1984, China has organized the impoverished people to carry out infrastructure construction in the fields, roads, rivers, houses, and toilets and has paid for grain, cotton, cotton cloth and industrial products to workers as labor remuneration. This measure not only provides employment opportunities and achieves income growth for poor workers but also improves infrastructure and public services in poor areas. In 1990, the State Council issued the Opinions on the Arrangement of Industrial Products for Welfare to Work from 1990 to 1992. According to the Opinions, 1.5 billion yuan of industrial products were used for the labor remuneration for workers in the construction of the welfare-to-work program; during the eighth five-year plan period, the Chinese government invested 1 billion kilograms of grain or equivalent industrial products per year in the Welfare-to-work program in poor areas; and in 1996, the welfare-to-work program was supported by financial funds instead of the form of in-kind cash conversion. In 1998, in the context of the financial crisis, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued measures to support the welfare-to-work program with treasury bonds, which solved the problem of expanding domestic demand. As an important part of the central poverty alleviation fund, the proportion of welfare-to-work funds increased from 15.38% to 37.04% in the ten years from 1986 to 1996, during which the acceleration of infrastructure construction in poor areas became the main operation mode of the welfare-to-work policy. At this time, the Welfare-to-work system not only had the function of disaster relief but also promoted the construction of local infrastructure.

(3) From 2000 to 2020: the special-purpose poverty alleviation policy stage. In the 21st century, the welfare-to-work program gradually has developed with “fine, small and deep” characteristics, with a focus on the implementation in a certain region or in-depth research on the analysis of welfare-to-work on the system (Shen, 2018 ). In December 2005, the NDRC issued the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work Policy, which highlighted the funds' management, project implementation, and organizational management of the welfare-to-work program, thereby improving the implementation performance of the policy. In 2011, to improve the quality of cultivated land, strengthen infrastructure construction, enhance the ability to withstand natural disasters, and consolidate the foundation of economic development in poor areas, the Chinese government issued the Outline for Poverty Alleviation and Development in China’s Rural Areas (2011–2020), in which the welfare-to-work program was included as a special-purpose poverty alleviation policy measure. In December 2014, to meet the requirements of rural poverty alleviation under the new situation, the NDRC launched the revision of the administrative measures for welfare-to-work policy. In 2016, the NDRC issued the National “13th five-year plan” for the welfare-to-work program, taking small and medium-sized infrastructure in rural areas the focus of the welfare-to-work program. According to the work plan, the welfare-to-work program should be transformed from “adopting a deluge of strong stimulus policies” to “precision regulation policies”, and a new model of poverty alleviation with asset income featuring “changing assets into equity, poor households into shareholders” should be innovated. In June 2019, the NDRC issued guiding opinions on further leveraging the role of welfare-to-work policies to help win the battle against poverty, which called for the continuous focus on supporting deeply impoverished areas such as the “three regions and three prefectures” to win the battle against poverty as scheduled and consolidate poverty alleviation achievements in poor areas. In July 2019, the NDRC issued Opinions on further adhering to the original purpose of “Relief” and giving full play to the function of the welfare-to-work policy, which underscored the importance of comprehensively expanding a variety of relief modes, relying on welfare-to-work projects to extensively carry out employment skills training and public welfare position development, and exploring the implementation of quantitative dividends through asset share conversion. In November 2020, the NDRC and nine other departments issued opinions on actively promoting welfare-to-work policy in the field of agricultural and rural infrastructure construction, requiring that the welfare-to-work policy should be actively promoted in the fields of rural production and life, transportation, water conservancy infrastructure, cultural tourism infrastructure, forestry, and grassland infrastructure construction, so as to improve rural production and living conditions, which has played an important role in consolidating the achievements of poverty alleviation.

(4) From 2021 to present: multifunctional comprehensive stage. In July 2021, the NDRC issued the National “14th Five-Year Plan” for the welfare-to-work program, which comprehensively expands the implementation areas, implementation functions, beneficiary groups, construction areas, and relief modes of the policy in the next five years. In July 2022, the NDRC issued a work plan on vigorously implementing welfare-to-work policy in key engineering projects to promote employment and income growth of local people. In the work plan, the NDRC emphasized that vigorously implementing the Welfare-to-work policy in key engineering projects is an important measure to promote effective investment, ensure employment stability and people’s well-being, stimulate county consumption, and stabilize the economic market, which will drive the people to share in the fruits of reform and development. In January 2023, in the context of a new journey and new requirements in the new era, the NDRC revised the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work policy. The NDRC stressed that on the one hand, we should stick to the original purpose of “Relief”, insist on helping people who have talent and poverty problems, and adhere to the principles of earning more from more work and getting rich through hard work to enhance the internal impetus of income growth and prosperity. On the other hand, we should strengthen the employment assistance for the people in difficulty, and promote common prosperity.

In summary, different from the “blood transfusion” poverty alleviation policy, “the welfare-to-work policy”, as an effective tool of the national “hematopoietic poverty reduction” policy, has a comprehensive poverty alleviation function and profound poverty alleviation connotation in solving the “two no worries, three guarantees”(no worries for basic food and clothing, and guarantees for compulsory education, basic medical services, and safe housing and drinking water), optimizing redundant resources, and improving the supply of public services and infrastructure. As the focus of China’s poverty reduction strategy has shifted from “extensive poverty reduction” to “targeted poverty reduction” and then to “consolidating the achievements of poverty alleviation”, the welfare-to-work policy has transformed from “adopting a deluge of strong stimulus policies” to “precision regulation policies”. However, the policy target always focuses on boosting employment and income growth, enhancing self-development and internal impetus to become rich, and promoting regional development; the scope of implementation has changed from the national key impoverished counties to the less developed areas with poverty alleviation as the focus; the construction field has expanded from the small and medium-sized rural infrastructure field to “one key area” and “seven major areas”; the relief mode has been expanded from the single mode of participating in the construction of welfare-to-work projects to obtain labor remuneration to the various relief modes such as conducting the quantitative dividends through asset share conversion, and carrying out employment skills training and public welfare position development; and the policy function has changed from the single relief type to the comprehensive type integrating the functions of promoting employment, ensuring people’s well being, carrying out emergency disaster relief, and boosting regional development of infrastructure (Table 1 ).

Literature review on the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction

The relationship between welfare-to-work and sustainable poverty alleviation of relative poverty.

In the early studies on poverty, poverty alleviation policy is an important influencing factor, and related theories involve human capital theory, poverty cycle theory and sustainable livelihood theory, etc. This paper will combine these theories to analyze the relationship between welfare-to-work policy and relative poverty and put forward a research hypothesis.

Long-term governance of relative poverty is the basic goal of poverty governance in China’s post-poverty alleviation era. The exploration of the transformation of government poverty alleviation ability should not only take this as starting point of the research, but also take solid theoretical achievements as theoretical support (Wang and Wang, 2021 ). Therefore, the governance of relative poverty should start from the perspective of sustainable development. On the one hand, it promotes the sustainability of the livelihood of local low-income people, including the continuous improvement of living standards and the continuous improvement of their livelihood self-improvement ability, that is, they are endowed with development power, create development opportunities, strengthen development ability and share development achievements at the individual level (Luo et al. 2021 ), and then realize the transformation from “blood transfusion” governance to “hematopoiesis” governance. On the other hand, relatively poor areas are an important type of area to promote the formulation of sustainable development policies in underdeveloped areas in China (Zhou et al. 2020 ). In 2020, Fan’s research team introduced the concept of relative poverty into the research of regional sustainable development for the first time, and expanded the micro-sustainable livelihood model into a macro analysis framework of sustainable development in underdeveloped areas–relatively poor areas (Fan et al. 2020 ). From the regional poverty-causing factors, the poverty types were divided and the classified poverty alleviation strategies were discussed. Through 20 consecutive years of follow-up research, this paper reveals the changing process of poverty-relative poverty and explores the poverty alleviation effect and its impact on the natural ecological environment and social progress. According to scholars Li and He ( 2022 ), endogenous motivation is an important foundation for sustainable poverty alleviation, and incentive policies such as “replacing compensation with awards” and “welfare-to-work” should be adopted to promote the transformation of poverty alleviation mode from blood transfusion to hematopoiesis.

According to the cycle of poverty, the development of poverty-stricken areas and the growth of residents’ living standards are subject to the lack of capital, which is the fundamental cause of the vicious circle of poverty (Nurkse, 1957 ). However, a basic feature of underdeveloped areas is that the infrastructure is relatively backward and the production conditions are relatively poor. The welfare-to-work policy is that the state injects construction capital from the outside, provides local infrastructure construction, improves farming conditions, and provides job opportunities for local low-income groups (Xiao and Yan, 2023 ). Foreign scholars can define the welfare-to-work program as a public intervention measure to provide employment opportunities for poor families and individuals with relatively low wages. However, according to sustainable poverty alleviation, the welfare-to-work policy studied in this paper refers to a poverty alleviation policy in which the government invests in the construction of public infrastructure policy, and the recipients participate in the policy construction to obtain labor remuneration instead of direct relief. For low-income people, the welfare-to-work policy has dual value: one is to reduce poverty and vulnerability (Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018 ), and the other is to create public goods through the work done by participants. It can also contribute to a third value if the participants acquire new skills. In addition, the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy strengthens the poor groups’ resistance to external risks by promoting social cohesion and strengthening economic ties between groups (Beierl and Dodlova, 2022 ). On the other hand, based on the local resource endowment, the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy is suitable for the local environment and promotes the sustainable development of underdeveloped areas by improving infrastructure and promoting industrial development (Si, 2011 ). Therefore, this paper puts forward the following assumption:

H1: welfare-to-work policy actively promotes sustainable poverty alleviation.

The mediating effect of infrastructures

According to the analysis of the welfare-to-work policy above, it can be seen that the main methods to implement the welfare-to-work policy are to carry out infrastructure construction in the fields of transportation, water conservancy, energy, agriculture and rural areas, urban construction, ecological environment, and post-disaster recovery and reconstruction. Many scholars have paid attention to the economic growth effect of infrastructure. But to govern poverty, the government should emphasize infrastructure investment, especially agricultural infrastructure investment (Xie et al. 2018 ). Firstly, the construction and improvement of rural infrastructure have created employment opportunities for low-income groups. The more opportunities local farmers have to obtain secondary and tertiary industries, the stronger the employment income-increasing effect of local farmers will be (Gibson and Olivia, 2010 ). In addition, rural infrastructure directly and significantly improves agricultural production efficiency, increases agricultural production efficiency, and reduces agricultural production costs. Secondly, infrastructure interconnection catalyzes the “market scale effect” and improves the market potential of poor areas. The accessibility of infrastructure guarantees the expectation of investment income, leading to expanded investment in poverty-stricken areas and increased innovation support received by producers in poverty-stricken areas (Zhang et al. 2018 ). Thus, his paper puts forward the following assumptions:

H2a: welfare-to-work policy achieves sustainable poverty alleviation effect through infrastructure.

There are two opposite views on the effect of financial poverty alleviation in academic circles. Some scholars such as Skoufias and Di Maro ( 2008 ), Imai ( 2011 ), and Xie ( 2018 ) believe that special financial transfer payment is an effective fiscal policy tool to reduce income inequality and poverty. According to Ma et al. ( 2016 ) and Huang ( 2018 ), financial transfer payment stimulates economic growth in poverty-stricken areas, reduces the incidence of poverty, and promotes the equalization of regional basic public services and financial resources. In addition, it has good policy effects in improving human capital, preventing future poverty, and improving income distribution according to Liu and Qi ( 2019 ). However, other scholars believe that financial transfer payments is not effective in reducing poverty. Presbitero ( 2016 ) pointed out that the large-scale increase of public expenditure in low-income developing countries did not significantly promote economic growth, and Chen et al. ( 2018 ) used the data from China Family Panel Studies to think that financial transfer payment did not play a good role in reducing extreme multidimensional poverty. According to Musgrave’s ( 1959 ) definition of the financial function, public finance should play three basic functions: resource allocation, economic stability, and income distribution. Welfare-to-work policy mainly means that the government provides capital supply and sufficient human capital guarantee for economic development in backward areas by issuing special poverty alleviation funds from the central government. It creates development opportunities for low-income people, consolidates the foundation of individual income growth, and then enhances the ability to resist risk shocks. In addition, increasing the income of such income groups or reducing their expenditure obligations can improve the production and living conditions of poor people and strengthen their economic self-reliance. Therefore, this paper puts forward the following hypothesis:

H2b: welfare-to-work policy achieves sustainable poverty alleviation effect through fiscal intervention.

The analysis method of combining welfare economics with poverty lays a foundation for multidimensional relative poverty theory and empirical research. Amartya Sen’s sustainable livelihoods theory ( 2005 ), attributes individual endowment and welfare sources to the substantive freedom of acquisition. It emphasizes the superposition of external risk impact and internal risk resistance, which easily causes rural families out of poverty to suffer the impact of poverty again and the emergence of poverty vulnerability. All of these hinder poverty alleviation, sustainability, and common prosperity to a certain extent. Finance is an important external influencing factor for the comprehensive development of counties, and financial poverty alleviation mainly provides poor households with “two exemptions one subsidy” micro-credit funds for productive poverty alleviation, which can better meet the capital needs of poor households for industrial development. At the same time, poor households are usually required to have a supporting production and operation policy when obtaining poverty alleviation microfinance, which can ensure that credit funds are effectively used for production and operation to a certain extent. In the long run, it is conducive to improving the self-development ability of poor households (Weng et al. 2023 ). In addition, there is an obvious synergy between rural financial poverty alleviation and financial poverty alleviation measures. Rural finance can often play a greater role in poverty alleviation on the basis of financial poverty alleviation measures (Xia, 2023 ), which can drive economic and industrial development, and then have a significant effect on poverty alleviation (Liu and Liu, 2020 ). Therefore, this paper defines financial instruments as financial measures to accelerate production by improving the ability of beneficiary individuals to resist risks and promoting the flow of local production factors. In the practice of the welfare-to-work policy, the implementation area is weak in resisting risk shocks, while the local people’s savings level can effectively improve the level of resisting risk shocks. On the other hand, because of welfare-to-work projects’ characteristics of long construction periods and poor capital demand, the transmission mechanism of monetary policy is used to better match the scale and structure of bank deposits and loans. By doing so, the circulation of production factors such as manpower, capital, and materials in underdeveloped areas can be accelerated, thus realizing the comprehensive effects of expanding effective investment, driving employment, and promoting consumption. In addition, financial institutions are guided to increase financing support, attract private capital to participate, and form a more physical workload. Therefore, the research hypothesis is as follows:

H2c: welfare-to-work policy achieves sustainable poverty alleviation through financial instruments.

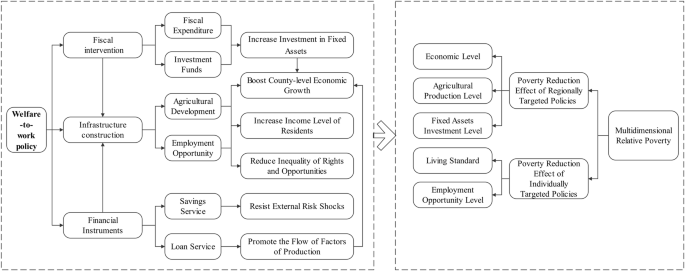

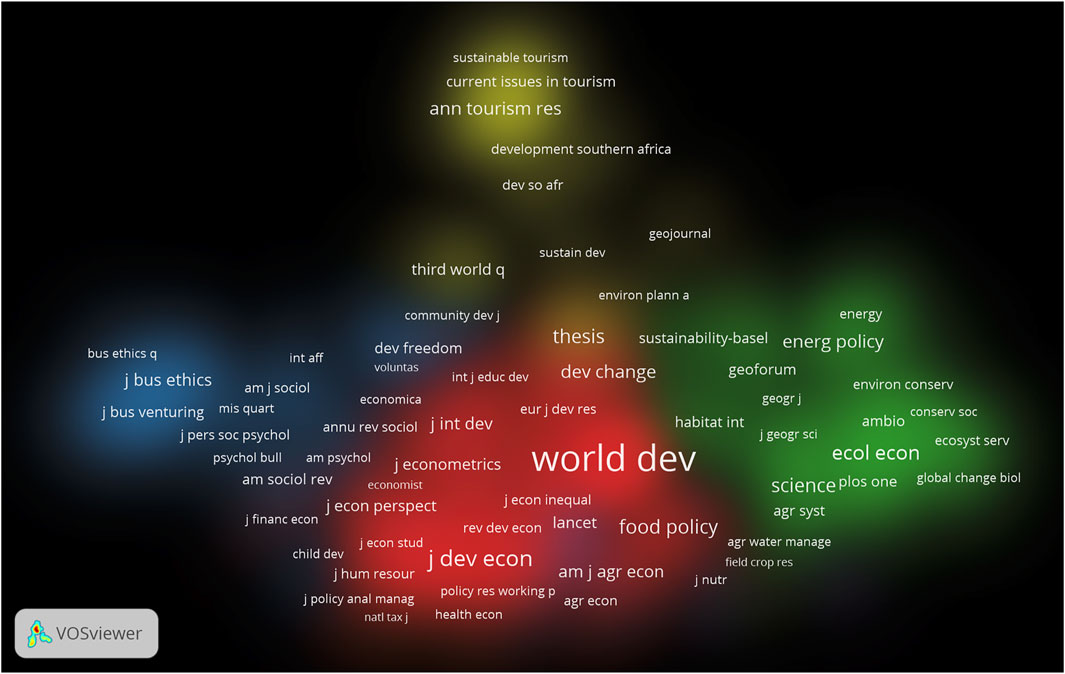

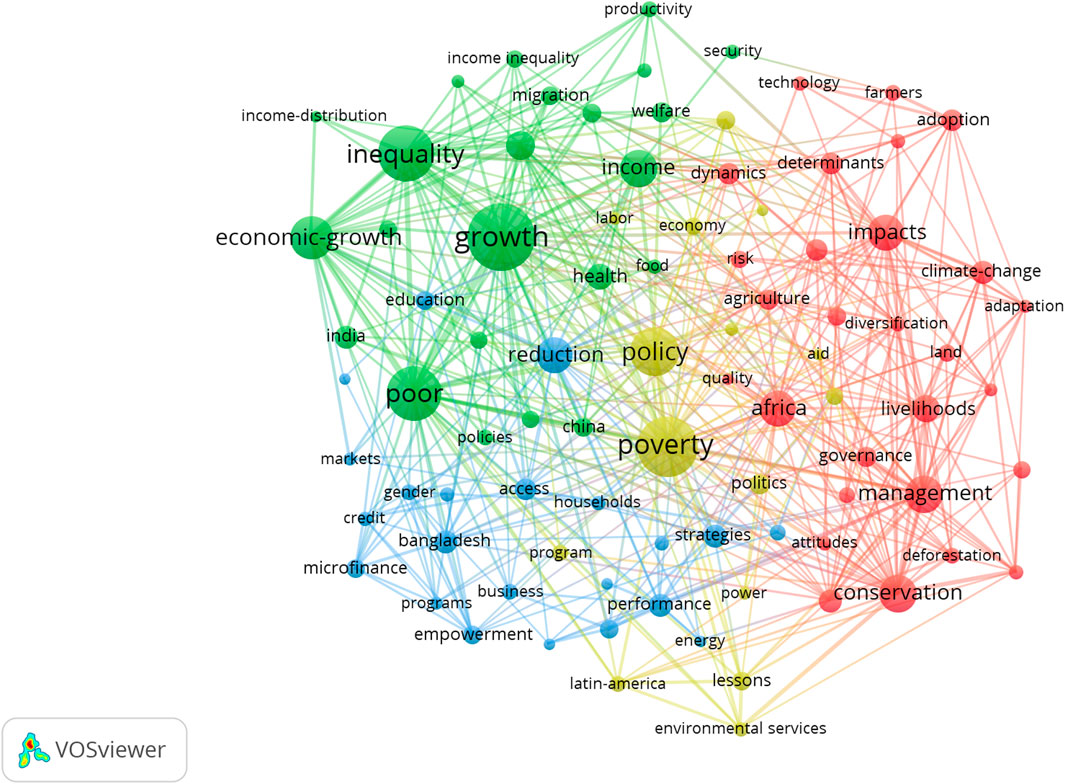

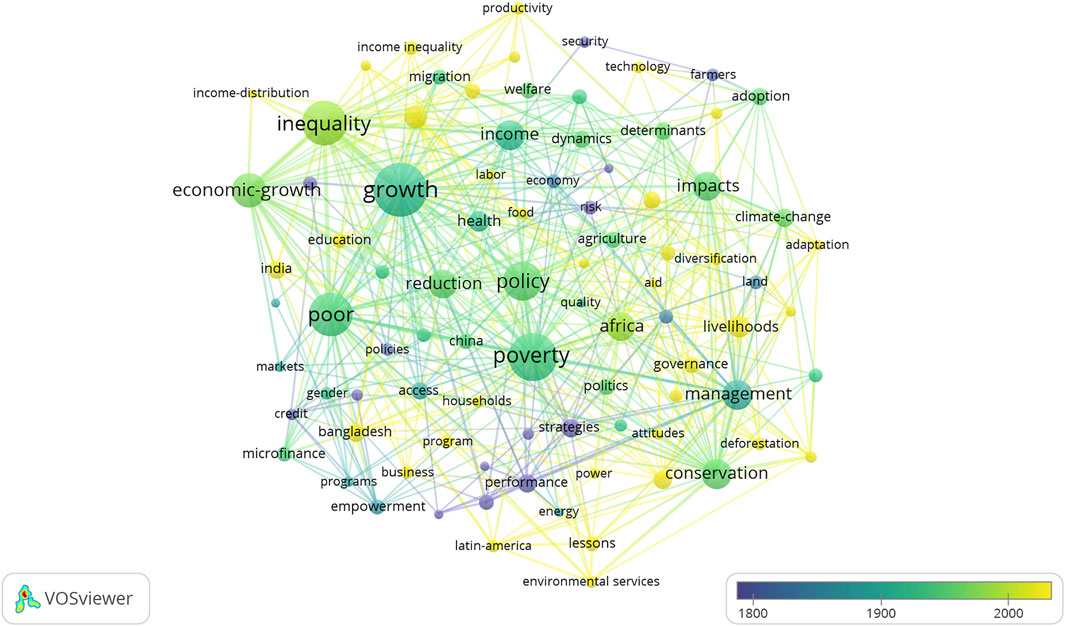

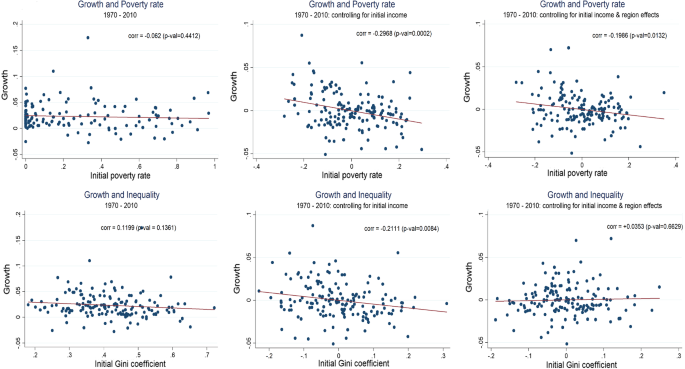

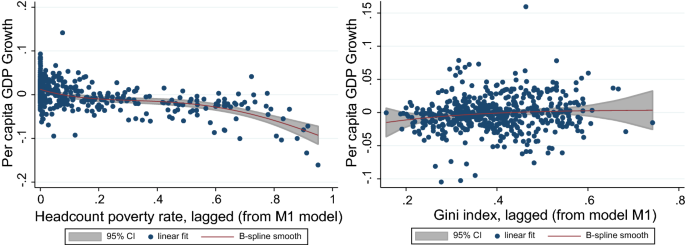

Currently, there are abundant studies on sustainable poverty reduction and policy assessment in academic circles, which provide good theoretical support and research perspective for this paper. But there are still several limitations: first, the current types of policy in poverty reduction mainly focus on the combination type or emphasis on the impact of poverty reduction policies implemented in a certain district, but there is room for research in the performance evaluation of a single welfare-to-work poverty reduction policy. Second, prior studies on quantifying their poverty reduction performance and action mechanism of the welfare-to-work policy by combining the policy with regional sustainable poverty reduction effects are relatively limited. Therefore, the theoretical analysis of this article is based on the theory of “welfare-to-work” and relative poverty. It summarizes the causes of relative poverty in underdeveloped areas, and on this basis, combines the characteristics of welfare-to-work to construct the theoretical analysis of poverty alleviation with welfare-to-work policy. As shown in Fig. 1 , firstly, according to the poverty cycle theory (Nurkse, 1957 ), the lack of capital formation and the contradiction between supply and demand in underdeveloped areas lead to low income and persistent poverty in underdeveloped areas. Secondly, according to the human capital theory (Schultz, 1949 ), human capital is the main factor of national economic growth. The loss of human capital caused by the difficulty of regional development has seriously affected the growth of the local national economy. In order to break this vicious circle, according to the capability approach (Amartya Sen, 2005 ), if a region wants to get rid of poverty and become rich, it must have the natural, economic, and social conditions to support its sustainable development. The welfare-to-work policy is the government’s financial investment in infrastructure to attract local people to work nearby. It is implemented in the form of government public investment to provide more employment opportunities for local people, and thus increases the opportunity cost of labor. On the other hand, stimulated by the market economy, the local labor force can have the opportunity to transfer from agricultural production to infrastructure construction conditionally, which improves the marginal income of the labor force. Firstly, they obtain skills training and increased stock of human capital; Secondly, they obtain broader horizons and more external economic information. In addition, according to development economics, the main constraint force to poverty alleviation comes from capital accumulation in which finance plays an important role. Through the intermediary function, finance can integrate social idle funds to realize the transformation from savings to investment, and promote poverty alleviation and economic growth at a higher level of equilibrium by improving the rate of capital accumulation.

Logical analysis of the impact of Welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction.

There are several potential contributions in this paper: firstly, the difference with other articles lies in the different research perspectives. Relative poverty will exist for a long time in a certain historical period, in specific areas, and in specific conditions. These characteristics of relative poverty are the key factors that constrain the objectives, contents, and methods of poverty governance. Therefore, sustainable development is introduced into the welfare-to-work policy to alleviate relative poverty and strengthen the sustainable poverty alleviation effect of the policy. On the other hand, it lies in the comprehensiveness of the research subject. According to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development promulgated by the United Nations, the sustainable development of poverty-stricken areas should also require people’s equal rights to access economic resources and inclusive and sustainable economic growth of the region. However, the relevant research on sustainable poverty alleviation directly or indirectly revolves around endogenous motivation stimulation and external resource assistance, and rarely analyzes and integrates these two themes within a unified framework (Ma et al. 2023 ). Therefore, this article takes individual and regional sustainable development as the main body, and takes the concept of sustainable development and the welfare-to-work policy as the donor, promoting the realization of sustainable governance of welfare-to-work policy in relatively poor areas. The third is to quantify the mechanism of action, because the policy will be affected by the local objective environment and show different effects in the implementation process as the regional scope of China’s welfare-to-work policy covering the central and western parts of China. This article adopts Shapley value to quantify the contribution of the action mechanism to poverty alleviation in different regions, and then provides policy reference for local governments to consolidate their poverty alleviation achievements and solve relative poverty problems.

Research design

Model construction.

The National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work policy (2005) was first formulated by the Chinese government with the aims of standardizing and strengthening the management of the welfare-to-work policy and improving the use efficiency of welfare-to-work funds so as to improve the production and living conditions and development environment of impoverished rural areas, and to help poor residents get rid of poverty and become rich Footnote 2 . Then, it was implemented in specific regions in 2006, and subsequently amended twice and respectively, named the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work policy (2014) and the National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work Policy (2023), but the starting points are to give full play to the role of welfare-to-work policy in poverty reduction.

Therefore, the author regards the welfare-to-work program as a quasi-natural experiment and takes 2006 as the processing point of welfare-to-work policy evaluation. The year before 2006 refers to before the policy implementation, which was denoted as time = 0; and the year after 2006 refers to after the policy implementation, which was denoted as time = 1. In addition, considering that the implementation areas of three revisions of the welfare-to-work policy are mainly less developed areas and ensure continuity of policy implementation, the regions that have been implementing the welfare-to-work policy since 2006 were selected as the treatment group whose dummy variable was set as treat = 1; and to ensure the net effect of the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy every year, the samples added to the implementation after 2006 were deleted, and the remaining regions without conducting the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy were defined as the control group whose dummy variable was set as treat = 0.

Drawing on the modeling practice of Yao et al. ( 2023 ), the author conducted tests on the net effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction by studying the increment over time and non-time-varying heterogeneity among individuals through DID elimination. The model settings are as follows:

Where the explained variable is the county multidimensional development index (CMDI), the core explanatory variable is the welfare-to-work policy interaction term (did = treat × time), \({\beta }_{1}\) represents the net effect of welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction; \({{\rm{\nu }}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) indicates individual fixed effects, which control the individual factors that affect CMDI but do not change with time; \({{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) denotes the period effect, which controls the time factors that affect all individuals over time; and \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) indicates the error term.

As the selection of the implementation area of the welfare-to-work policy is subject to national regulation and coupled with imperceptible factors, to avoid selectivity bias and endogenous problems and ensure the robustness of results, the PSM-DID method was employed to conduct a robustness test, and the following model was constructed. The variables are defined as Eq. ( 2 ):

Dynamic effect model

Besides, to test the dynamic effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction, on the basis of Eq. ( 1 ), a dynamic effect model was constructed as follows:

In the model, \({{\rm{treat}}}_{i,t}\,\times\,{{\rm{time}}}_{i,t}\) represents the dummy variable of the dynamic poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy. When the welfare-to-work policy is set at period t, its value is 1.

Test model of action mechanism

To further investigate the impact of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction, the author took the modeling ideas of scholars Li and Zhang ( 2021 ) as a reference to interact with the independent variable did, so as to test the differences in sustainable poverty reduction in counties with different levels. The specific model settings are as follows:

Where M is the variable of the action mechanism, which is considered from infrastructure construction, government finance and financial poverty reduction. \({Y}_{{it}}\) is the explained variable, representing the relative poverty parameter of the county (CMDI) and a series of outcome variables about the multidimensional development of the county; \({\beta }_{1}\) represents the influence of the welfare-to-work policy on the dependent variable \({Y}_{{it}}\) through the action mechanism variables, while \({\beta }_{1}\) is significantly positive, the incentive variable \({Y}_{{it}}\) through the action mechanism variable M , M is the mechanism variable of the welfare-to-work policy; other parameters have the same meaning and benchmark model parameters.

Variable selection

Explained variable: cmdi.

The academic research on regional multi-dimensional relative poverty index systems mostly draws on the theory of man-land relationships and sustainable livelihood theory. British international development institutions based on a multidimensional perspective established a sustainable livelihood model, from the economic, natural, human, material, and social five aspects of comprehensive indicators, and the Chinese Social Science Research Institute of sustainable development strategy group combined with domestic actual situation, established to involve “government regulation, social development, scientific and technological innovation, human resources, survival, safety and environmental protection” and so on six big ability as the core of sustainable ability analysis framework.

Based on the research of the sustainable livelihood model by scholars Zhou et al. ( 2020 ) and Xu et al. ( 2021 ), this article builds a bridge between micro-main economic activities and regional high-quality development, draws lessons from the poverty alleviation requirements and tasks specified in the relevant policy documents of Welfare-to-work, and follows the principles of data availability, dynamics, and relevance.

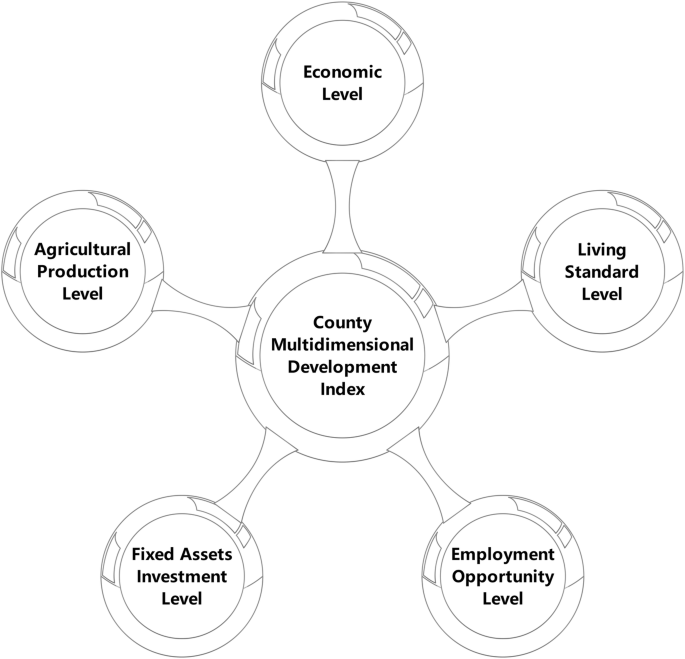

As shown in Fig. 2 , “opinions on actively promoting welfare-to-work in the field of rural infrastructure construction” emphasizes that giving full play to the multiple functions of welfare-to-work policy, such as employment, disaster relief, investment, and income, it is combined with making up the shortcomings of infrastructure in the fields of agriculture, rural areas, and farmers to consolidate the construction of agricultural production capacity (Lan, 2021 ). Drawing lessons from the research of Liu and Zhao ( 2015 ) and Yang et al. ( 2023 ), the output efficiency of agricultural land is used to measure the agricultural production efficiency, that is, the output of crops per unit area is used. The ratio of rural employment number to the total population under the county is used to measure rural employment opportunities. The logarithmic value of Real GDP per capita (ln PGDP) is used to measure the level of county economic development the logarithmic value of rural per capita disposable income is used to measure the county living standard, and the ratio of fixed assets investment to GDP is used to to measure the level of fixed investment.

Framework of indicators for CMDI.

The identification of multidimensional relative poverty depends on CMDI. This article mainly draws lessons from the calculation ideas of Xu et al. ( 2021 ), and makes improvements on this basis. Specific calculation methods are as follows: firstly, the calculation idea is as follows: the entropy weight method is used to calculate the index weights of each dimension, and the scores of each dimension are calculated on this basis. Then, the polygon area method is used to calculate the CMDI. The reason why the area method is chosen instead of the simple weighting method is that the pentagon constitutes a stable structure and develops in a balanced way, and the five livelihood capitals influence each other, which can not only characterize the multi-dimensional relative poverty degree of the county, but also characterize its sustainability and anti-risk degree. The calculation formula is as follows:

Assuming that the scores of county i in five dimensions are a , b , c , d , and e respectively, and the angle between any two dimensions is α (α = 360°/5).

In addition, in order to avoid the difference of area caused by different sorting methods of five dimensions, the final algorithm is to calculate the average of various possible results. The larger the development index, the higher the comprehensive development potential of the county, the stronger its sustainability and anti-risk ability, and the lower the multidimensional relative poverty level. On the contrary, the higher the degree.

Control variables

In addition to the impact of the welfare-to-work policy on the sustainable development of the county, there are other influencing factors. Therefore, to eliminate interference, these exogenous factors need to be controlled. Drawing on the research ideas of Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), this paper selected the following control variables: the county-level population density was employed to control the impact of economic agglomeration on its economic development; the logarithm of the total output value of large-scale industry was employed to reflect the industrial scale level, and the social consumption level was measured by the total retail sales/total population of household registration; the ratio of the number of rural households to the total number of households in the county was selected to measure the urban-rural structure; and local telephone users were chosen to evaluate the level of regional information, and the ratio of the number of students in primary and secondary schools to the total population was used for the measurement of the educational level of the county.

Data description

The data used in this paper were sourced from the county-level Statistical Yearbook and China Regional Database. The data from 2000 to 2019 at the county (city) level in China were collected, and the counties with incomplete main variables were screened and processed, including 1687 county-level units, among which 456 counties with the implementation of welfare-to-work policy were set as the treatment group. In addition, due to the gap between the development of the eastern and western parts of China, the economically developed areas of the eastern coastal area were excluded from the control group, and the 1231 counties failing to implement the welfare-to-work policy were set as the control group. Other data come from the Statistical Yearbooks and statistical announcements of counties (districts) and cities across the country, and the data that cannot be obtained by each county (district) and city were supplemented by searching for the government data of the corresponding distract. To reduce the impact of heteroscedasticity on the results, all variables were processed by CPI index (with 2020 as the base period) and conducted logarithmic processing. The descriptive statistics of variables are shown in Table 2 .

Analysis of empirical results

Benchmark regression analysis.

The benchmark results are shown in Table 3 . The control variables were not included in column (1), resulting in a significantly positive estimated coefficient of poverty reduction through welfare-to-work policy; and the control variables were introduced in column (2) with a result of a still significantly positive coefficient, indicating that welfare-to-work policy significantly promoted the comprehensive development and alleviated the relative poverty level of counties. Different from the previous two columns, both the individual fixed effect and the year fixed effect were controlled in column (3), as a result, the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy was still significant.

On this basis, the effectiveness of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction will be further studied to analyze poverty reduction performance in various aspects in detail. The results are shown in Table 4 .

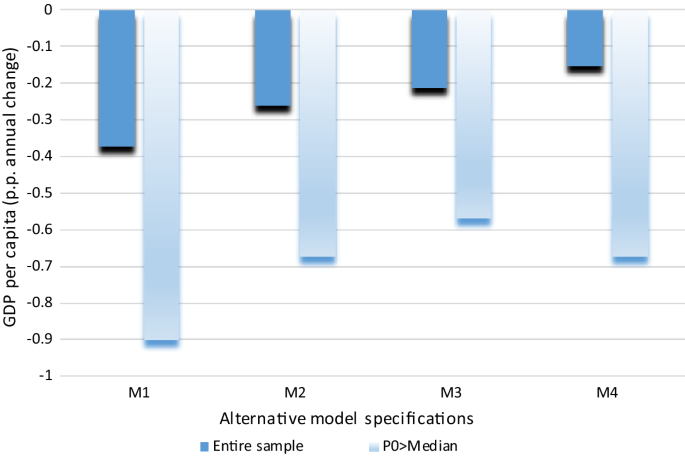

The results from columns (1–5) show that: with the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy, the GDP per capita of counties has significantly increased by 11.1%, the disposable income of rural residents by 1.3%, the level of fixed asset investment by 14.0%, the quality of cultivated land by 73.7%, and the rural employment opportunities by 0.7%. These growth data indicate that the welfare-to-work policy not only can significantly promote development and effectively alleviate the relative poverty of the counties, but also can achieve remarkable results in “stabilizing employment and ensuring income to boost the economy”, especially in the quality of cultivated land. However, although the policy plays a significant role in providing rural employment opportunities, the coefficient is the smallest. According to the relevant literature on China’s welfare-to-work and foreign welfare work policies, the author finds that welfare-to-work emphasizes the employment promotion mechanism in poverty alleviation, which is essentially consistent with the work-for-welfare concept of “work” for “welfare”, but welfare-to-work emphasizes disaster relief and regional economic development, combines government investment with public demand, and the government focuses on agricultural production development and rural infrastructure investment and construction. The implementation area is mainly concentrated in underdeveloped areas to improve the local development environment, improve the living standards of local residents, and increase the output of land by increasing investment to improve production conditions (Xiao and Yan, 2023 ). In addition, the implementation of the Welfare-to-work policy is mainly supported by the government’s financial and monetary support, while the relevant relief policies affect economic development through various transmission mechanisms, and then affect the employment problem. The policy transmission chain is too long, and employment is at the end of policy transmission, which is only a by-product of the strategy of promoting growth, and the efficiency is bound to be deficient (Tcherneva, 2014 ). Therefore, the Welfare-to-work policy has the weakest impact on employment and a greater impact on the quality of cultivated lands.

Robustness test

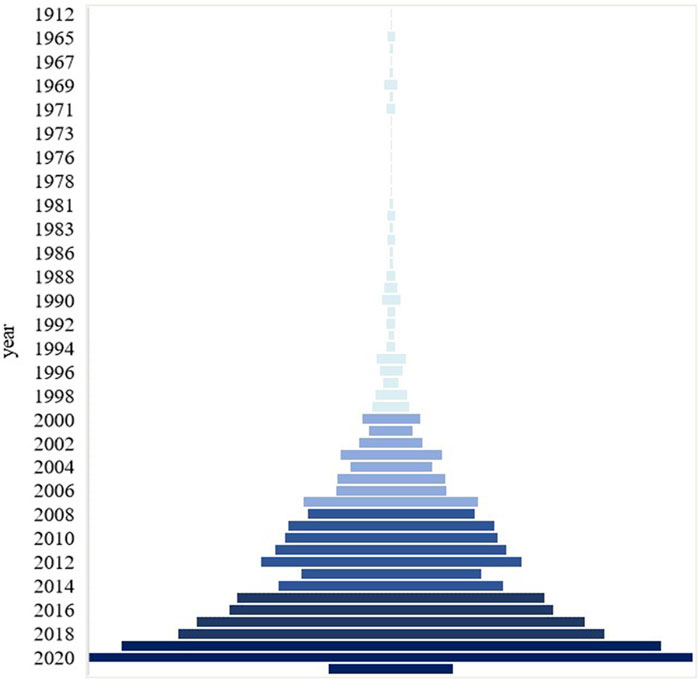

Parallel trend test and dynamic effect test.

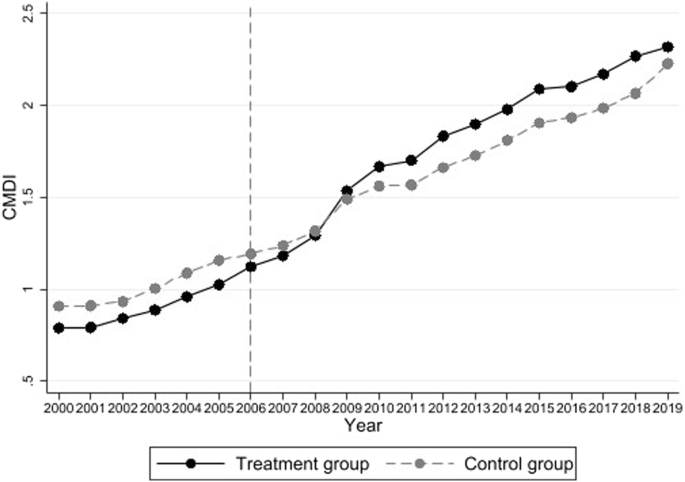

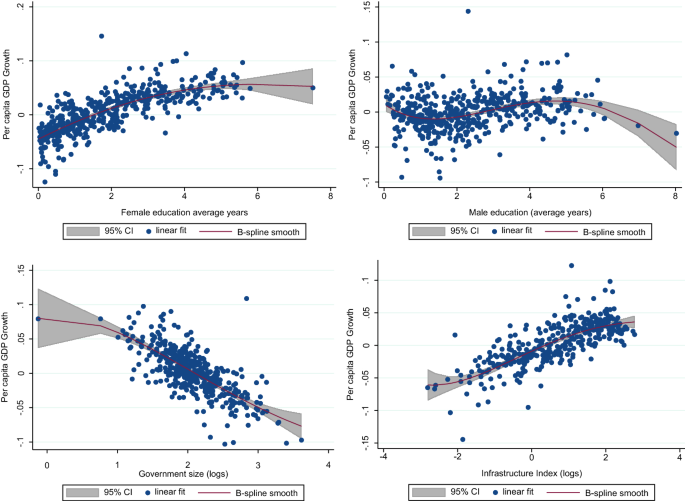

By conducting parallel trend tests, the author can accurately evaluate the net effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction by using the DID method. The condition for passing the test was that before the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy, the coefficients of the treatment group and the control group showed a parallel trend on the whole.

As shown in Fig. 3 , there is a same change trend between the treatment group and the control group before the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy, but there was a difference after the policy implementation. Especially after the policy implementation, the annual differentiation increased significantly, indicating that the economic status of the treatment group is significantly better than that of the control group, which provides evidence for the effectiveness of the policy.

Parallel trend of poverty reduction between the treatment group and the control group.

Equation ( 3 ) was employed to test the dynamic effect of welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction, and the results are shown in Table 5 .

When other variables are controlled, the coefficient of interaction term in 2006 is 0.0063, which shows a significantly positive trend, and there is no hysteresis effect. When the policy time point moves backward year by year, the coefficient of the interaction term is significantly positive and constantly increasing, indicating that the welfare-to-work policy has a sustainable poverty reduction effect.

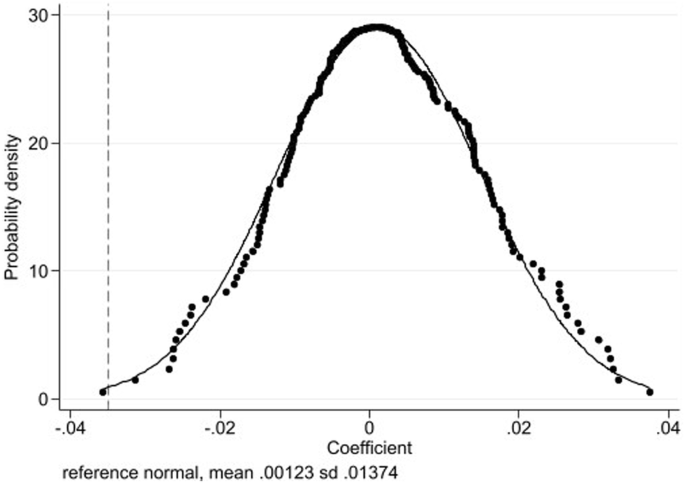

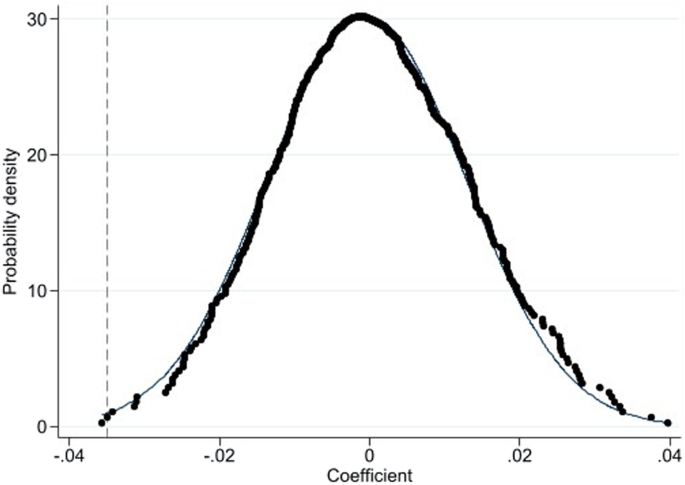

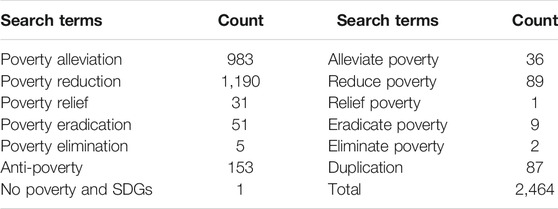

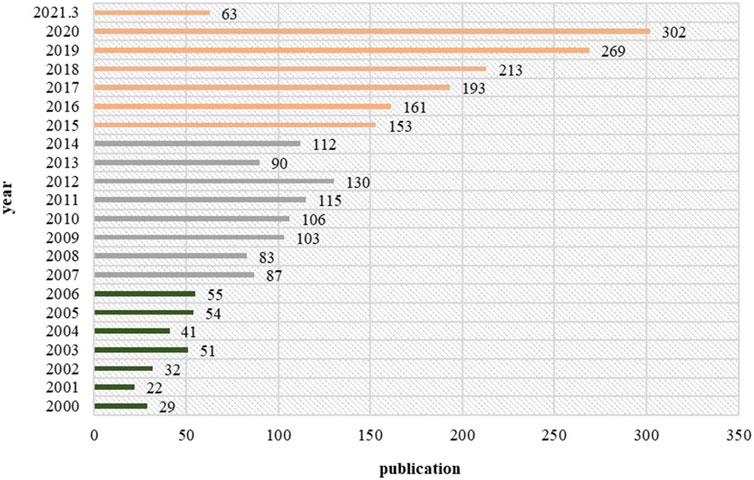

Placebo test

To ensure the robustness of the regression results, the author refers to the ideas of scholars Qian and Ma ( 2022 ) and adopts a “counterfactual” method. Two hundred fifty counties in all regions were randomly selected as policy implementation areas, and other regions were regarded as control groups. To avoid the influence of interaction terms on the explained variable CMDI, random sampling was set to 200 and 500 times, respectively, and the estimated coefficients of 200 and 500 interaction terms DID could be obtained, respectively.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5 , the results obtained from the two random sampling show that most of the coefficients and values t are concentrated around 0 and follow a normal distribution. The mean value is far from the true value, and most of the estimated coefficients are not significant, indicating that other unobserved factors have no impact on the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy, which is in line with the expectation of the placebo test.

The placebo test-sampling 200 times.

The placebo test-sampling 500 times.

Replacement of evaluation method (PSM-DID method)

First, the propensity score PS values of all samples were estimated, and then the samples with similar PS values to the treatment group were selected. That is, under the constraints of characteristic variables such as urban–rural structure, educational, medical level, and government fiscal intervention degree, the Logit model was utilized to estimate the predicted probability P(Xi) identified as implementing the welfare-to-work policy. Then the nearest neighbor matching, radius matching, and kernel matching methods were used to match the samples of the treatment group with the control group, respectively, and the control group samples with the most similar comprehensive characteristics were employed as the control group. The results are shown in Table 6 . After matching, the mean value of each covariate is not significantly different from 0 in the control group and the treatment group, which satisfies the equilibrium hypothesis test.

Then, the net effect of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction was tested based on the DID method. The regression results are shown in Table 6 . Compared with the benchmark results, the three matching methods are basically consistent in terms of the estimated coefficient, symbol, and significance level, which confirms the robustness of the conclusions in this paper.

Replacement of the measuring method of the explained variable

In this paper, the CMDI which was constructed on the basis of a sustainable livelihood model was used to measure the county multidimensional poverty degree, while the academic community often adopts the A–F double critical value method and FGT method to measure the regional multidimensional poverty degree. Therefore, to ensure the robustness of the results, the author replaced the current measurement method with the A–F double critical value method and FGT method, respectively to test the robustness of the explained variable—relative poverty degree in counties.

The results are shown in Table 7 . The estimated coefficients obtained from the A–F double critical value method and FGT method are 0.01 and 0.009, respectively, with significance at the 1% level. Compared with the result of benchmark regression, the coefficients are slightly lower but still play a positive incentive role, which confirms the robustness of the benchmark regression result.

Heterogeneity analysis

County-level heterogeneity.

To explore the heterogeneity in the effect of poverty alleviation policies in the counties with different development levels, the quantile diff-in-diff method was adopted for analysis. Compared with the OLS method, the overall picture showing the conditional distribution of explained variables was more comprehensive and the outliers were more robust.

The results are shown in Table 8 . The DID coefficients of the interaction term of CMDI at 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 90% quantiles were all significantly positive at the 1% level, with the highest coefficient at 90% quantile and the lowest coefficient at 10% quantile. The results indicate that there is heterogeneity in the effect of poverty alleviation policies in the regions with different sustainable development levels, and the higher the development level, the stronger the driving effect. Therefore, enormous efforts should be made in the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy. The government should take proactive moves to accelerate the construction of infrastructure in areas with low development potential, and make full use of financial tools to drive the flow of production factors. Besides, the government should encourage the cultivation of industries with local features according to local conditions to improve the regional sustainable development level and boost the county economic development, so as to prevent the large-scale poverty-return phenomenon and effectively consolidate the achievements of regional poverty alleviation.

Regional heterogeneity

With the economic development, there are obvious differences in China’s regional development due to geographical location, infrastructure, public services, economic foundation, and other factors. The absolute majority of the people who are lifted out of poverty are located in rural areas in the central and western inland provinces. It is necessary to conduct a regional heterogeneity analysis on the basic regression results. Therefore, the sample size was divided into the central, northwest, and southwest regions, and Eq. ( 1 ) was employed to carry out studies on the effect of the poverty alleviation policies in each region.

The results are shown in Table 9 . The estimated parameter of the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy in the central region and northwest region is 0.172 and 0.157, respectively, with significance at the 1% level, while the estimated parameter of the southwest region is 0.035 with no obvious significance. The results indicate that the welfare-to-work policy has a significant effect on poverty reduction only in the central region and the northwest region, but not in the southwest region, with a higher effect in the central region followed by the northwest region. According to the relevant poverty alleviation policies implemented in China since 2005, the paper finds that a large amount of poverty alleviation resources have been invested in the central and western regions, while the central region has a higher level of development in its enterprises, a significant improvement in income level and a better driving effect of social participation compared with the western region. In addition, since the reform and opening up, although the poverty-stricken areas in the west have also developed to some extent, the gap between the eastern and central regions is widening, and the distribution of poor people is further concentrated in the western region according to Liu and Ye ( 2013 ). Moreover, the counties in the southwest region are mostly hilly counties and ethnic counties, which will significantly weaken the positive impact of the national poverty-stricken county policy on county poverty and the income gap between urban and rural (Guan et al. 2023 ). In addition, this is consistent with the conclusion of county heterogeneity mentioned above, and the sustainable poverty reduction effect of cash-for-work policy in areas with weak development degrees is weaker than that with higher development station levels. Therefore, the effect of the welfare-to-work policy in the southwest region is weaker than in other regions.

Test of action mechanism

Test of action mechanism of welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction.

According to existing literature research, infrastructure is the main impact mechanism of policy poverty reduction, and government finance is the material guarantee for the smooth implementation of the welfare-to-work policy, which has an important impact on the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy. In addition, financial poverty alleviation cultivates the mechanism of hematopoietic and promotes financial marketization in rural areas (Wang et al. 2021 ). With reference to the specific methods of employment assistance, the welfare-to-work program provides preferential policies such as social insurance subsidies, tax incentives, and small guaranteed loans to enterprises that recruit poor laborers to participate in project construction or provide basic jobs, so as to reduce the production cost of enterprises, thus promoting a virtuous cycle of social and economic development (Qin, 2022 ). Therefore, the action mechanism variables of infrastructure construction level, government fiscal intervention, and financial tools were added to the model to conduct a test via Eq. ( 4 ).

First, infrastructure construction is the main way to implement the welfare-to-work policy. Through the opinions on actively promoting welfare-to-work in the field of agricultural and rural infrastructure construction, the NDRC and other nine ministries and commissions emphasize that the main areas for the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy should be strengthened in the field of agricultural and rural infrastructure. Through infrastructure construction, the development environment of agriculture and rural areas will be improved, on the other hand, the effect of increasing employment income will be promoted. Referring to Qiu et al. ( 2021 ), this paper selects the logarithmic output value of capital construction to express the level of infrastructure construction. Second, the measures for the management of welfare-to-work emphasize that government investment in infrastructure construction, that is, government finance, is the material guarantee for the implementation of the welfare-to-work policy, which has an important impact on the poverty alleviation effect. More investment benefits will be achieved when government investment is closely combined with public demand, the role of beneficiaries is brought into full play in the construction of investment policy, and the active participation of beneficiaries is actively promoted (Ma, 2023 ). Referring to Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), this paper uses the logarithmic value of general expenditure of the public budget to express the degree of government financial intervention. Third, savings and credit are effective ways to significantly increase risk resistance and reduce household vulnerability to poverty (Urrea and Maldonado, 2011 ). With reference to the specific methods of employment assistance, the welfare-to-work policy gives preferential policies such as social insurance subsidies, tax incentives, and small secured loans to enterprises that recruit poor laborers to participate in engineering construction or provide basic jobs, so as to reduce the production costs of enterprises and promote a virtuous circle of social and economic development (Qin, 2022 ). Referring to Zhang et al. ( 2019 ), this paper uses the logarithm of the loan balance of financial institutions at the end of the year to represent the loan level as an indicator that directly reflects the use level of financial instruments; The balance of urban and rural residents’ savings deposits/total resident population is selected to indicate the local savings level and reflect the local indicators to resist the impact of external risks.

The results are shown in Table 10a–d : (1) the coefficient of the interaction term of infrastructure construction level is significantly positive, indicating that the county-level poverty reduction has gotten a greater degree with the improved infrastructure investment level. With the construction of infrastructure, the welfare-to-work program focuses on infrastructure fields such as “mountains, forests, paddy fields, roads, grass, and sand”, as well as, on infrastructure projects related to rural life and production. The welfare-to-work policy stimulated the development of a non-agricultural economy in impoverished areas and promoted the transformation and upgrading of employment structure to a diversified and high-value level, thus optimizing the spatial layout of infrastructure and improving the efficiency of resource allocation and giving play to the poverty reduction effect of infrastructure (Lin and Lin, 2022 ). On this basis, the author separately conducted an analysis of the target indicators of the welfare-to-work policy. The results show that except for insignificant improvement in labor efficiency, the level of infrastructure construction has played a significantly positive role in the rest of the aspects. The welfare-to-work policy has a significant impact on “boosting economic growth”, “ensuring income” and “maintaining employment stability” through the level of infrastructure construction. (2) Government financial intervention plays a significant role in the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy. In other words, the government can effectively improve the degree of poverty reduction in the local region by increasing government financial expenditure on the welfare-to-work program. However, specifically, the government fiscal expenditure can effectively increase the per capital disposable income and fixed asset investment level of local rural people, but inhibit the development of the local economy. The possible reason lies in that the government fiscal expenditure will directly affect the increase of the local GDP. (3) The utilization of financial tools can effectively promote the poverty reduction degree of welfare-to-work policy, especially can significantly boost the local economic growth and income growth of rural residents.

Regional heterogeneity test of action mechanism

To further verify the impact of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction through mechanism variables in different regions, according to the particularity of policy implementation and sample limitations, the samples were divided into three sub-samples in northwest, southwest, and central regions for regional heterogeneity test.

The results are shown in Table 11 . In the northwest and southwest regions, the three action mechanisms of infrastructure construction, government fiscal intervention, and financial tools play a significant role in the impact of the county poverty reduction degree, but there is heterogeneity among regions. Specifically, the financial tools play a positive role in poverty reduction in the northwest region but caused a significantly inhibited effect in the southwest, while the test was invalid in the central region. With regard to the heterogeneity of financial instruments among regions, the author researches the relevant theories and literature, and finds that the mitigation effect of finance on rural poverty is unbalanced among regions. However, due to the imbalance of resource endowments and economic development in central and western China, there is a gap in the level of financial development in different regions, leading to different effects of poverty alleviation (Zeng and Hu, 2023 ). Thus, the effect of financial poverty alleviation is also affected by the regional relative poverty level. When the income gap between urban and rural areas is large, the relative poverty level is high, and the downward trend is gentle, the poverty alleviation effect is more significant. The relative poverty level in the western region is higher than that in the central region, so the poverty alleviation effect in the central region is weaker than that in the western region. In addition, economically backward areas have less financial support for finance, imperfect financial infrastructure construction, and unbalanced allocation of financial resources, which restrict the availability of financial services for economic entities in economically backward areas. The shortage of financial service supply often forms a “crowding out effect” on rural low-income groups, while the development level of Southwest China is lower than that of Northwest China (Gong and Chen, 2018 ). The availability of financial services in southwest China is weak, which forms service barriers and inhibits the integration of funds.

Analysis of the contribution of the action mechanism variables

The above tests proved that the welfare-to-work policy has an impact on county-level poverty reduction performance through the infrastructure level, government fiscal intervention, and financial tools. However, there is a heterogeneity in the poverty reduction effect between regions. In order to better combine their own advantages in local counties, timely regulate the infrastructure construction, policy and financial intervention, and financial tools, so as to achieve the sustainability of poverty reduction in counties. With reference to the research of Fu and Tang ( 2022 ), the author adopted the Shapley value decomposition method to figure out the contribution degree of action mechanism variables to the county-level poverty reduction performance in different regions. The principle is to average the marginal effect of a factor by calculating the possible results of all combinations and all other factors, and then obtain the marginal contribution of the factor.

In accordance with Table 12 , the estimation results provide a good explanation of the impact of each variable on county poverty reduction. On the whole, among the three major action mechanism variables, infrastructure construction contributes the most with ratios of 58.31%, 51.96%, and 57.33% to the county economic development, the income and the employment opportunities of rural residents, respectively, and it occupies the second place in fixed asset investment, reaching 44.22%, but makes a most minor contribution to the cultivated land quality, only reaching 2.58%. The government financial intervention contributed the most to the fixed asset investment and cultivated land quality with ratios of 45.29% and 66.23%, respectively, the second to the employment opportunities reaching 23.57%, while the least to the county economic development and the rural residents’ income with ratios of 1.71% and 1.05%, respectively. Financial tools take the second place in contribution with ratios of 39.98%, 47.00%, and 2.19% to the county economic development, the rural residents’ income, and the cultivated land quality, but make the least contribution to fixed asset investment and employment opportunities, only reaching 10.49% and 19.10%.

Specifically, in southwest China, infrastructure construction makes the most significant contribution to the promotion of the county economic development, the rural residents’ income and fixed asset investment, fiscal intervention, and financial tools play a decisive role in improving the cultivated land quality with the contribution rate reaching over 40%, and financial tools have a contribution ratio of 68.13% to employment opportunities. In northwest China, infrastructure construction makes the highest contribution to the promotion of county economic development and rural residents’ income, both reaching over 60%; infrastructure construction and fiscal intervention contributed the most in terms of fixed asset investment with ratios of 37.06% and 48.75%, respectively, accounting for more than 85% of the contribution; financial tools make the highest contribution to improving the cultivated land quality, reaching 67.58%, and both the government fiscal intervention and financial tools make the contribution of over 40% to employment opportunities. In central China, infrastructure construction contributes the most to the promotion of the county economic development, rural residents’ income and fixed asset investment, financial tools play the highest role in improving the cultivated land quality, and the government fiscal intervention and financial tools make the contribution of 36.97% and 43.99% to employment opportunities, respectively.

Conclusions and policy suggestions

Conclusions.

The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of cash-for-work policies in reducing poverty and to provide insights on how to improve these policies in the future. On the basis of combining the evolution of the cash-for-work policy, the impact of the welfare-to-work policy on poverty reduction is empirically analyzed by using the DID method. The basic regression results show that the sustainable poverty alleviation effect of the welfare-to-work policy reaches 16.1%, which shows that the welfare-to-work policy significantly promotes the sustainable poverty alleviation effect in county areas. which was mainly reflected in the sustainable poverty reduction effect of regional economic development and the endogenous driving force of people’s livelihood income increase and prosperity, which showed that the poverty reduction effect of the welfare-to-work policy was significant, promoted the accumulation of social capital, effectively increased the development opportunities of the local people, and improved the endogenous motivation of the local people. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of the sustainable poverty reduction effect of the cash-for-work policy verifies the heterogeneity in different regions and different levels of development, and confirms that the strength of the development level in the three regions is consistent in China. From the perspective of mechanism, the cash-for-work policy has promoted the sustainable development capacity of counties and alleviated the relative poverty level of counties through a series of measures such as infrastructure construction, fiscal intervention, and financial instruments. However, due to the differences in resource endowment and development levels among different regions, the effect of different mechanisms on the sustainable poverty reduction of cash-for-work policies is inconsistent in different regions. Among them, the impact of infrastructure construction on county-level sustainable poverty alleviation is the largest, and the impact of financial instruments on county-level sustainable poverty reduction is promoted in the northwest region, but significantly inhibited in the southwest region, while the poverty reduction effect is not significant in the central region.

The main finding of this study is that t the welfare-to-work policy for poverty reduction has achieved great results in regional economic development and people’s livelihood income increase. However, a number of challenges and constraints still need to be addressed to ensure the sustainability of poverty reduction efforts.

Policy suggestions

Based on the above analysis, this paper puts forward the following suggestions for improving the sustainable poverty reduction of cash-for-work policies:

First, sustainable poverty reduction should be achieved through the use of active and differentiated cash-for-work policies. Cash-for-work policy support cannot be simply implemented in all regions, but should be based on its own unique geographical environment and resource advantages, increase the construction of infrastructure suitable for itself, adapt measures to local conditions, develop characteristic industries, realize the upgrading of regional economic quality and efficiency, and focus on employment opportunities for the local people, actively help the local people to broaden the channels for nearby employment and income, and strengthen the self-survival and development ability of local groups.

Second, the government needs to further increase the construction of financial services in the southwest and central regions, further, enhance the internal function and effect of financial services, attract social forces to actively participate in the construction of rural infrastructure region, and give full play to the multiplier effect of the combination of financial services and infrastructure construction to achieve long-term sustainable poverty reduction. Accordingly, in the central region, the government should step up efforts in financial intervention, and all parties should reasonably adjust the critical point of infrastructure construction to improve supply efficiency and poverty reduction efficiency, in the northwest region, the government should focus on taking advantage of financial tools to create good business tools; and in the southwest region, the government should adjust the use pattern of financial tools to promote local high-quality development.

Third, focusing on the specific situation of deeply impoverished areas and special poverty groups, we will increase government financial investment in poverty alleviation, and strive to improve the effectiveness of sustainable poverty reduction. On the one hand, we should give preference to project approval and resource allocation, and improve the allocation of public financial resources to underdeveloped areas and low-income groups from the macro, and micro levels, so as to improve the efficiency of supply and poverty reduction. In addition, the quantitative conclusion of the mechanism of action shows that fiscal intervention has played a positive incentive role, but the effect is not large, especially in indirectly promoting regional economic growth and individual development, so we should pay attention to guiding the supplementary and regulating role of the third distribution on redistribution, and at the same time support the development of industries that meet the needs of poor areas to improve people’s livelihood and well-being.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Xi Jinping’s Speech at Summary Commendation Congress for National poverty alleviation.

National Development and Reform Commission—decree no. 41 of the National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China “National Administrative Measures for welfare-to-work Policy” (2005).

Beierl S, Dodlova M (2022) Public works programmers and cooperation for the common good: evidence from Malawi. Eur J Dev Res 34:1264–1284

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen GQ, Luo CL, Wu SY (2018) Poverty reduction effect of public transfer payment. J Quant Technol Econ 35:59–76. https://doi.org/10.13653/j.cnki.jqte.20180503.005

Article Google Scholar

Fan J, Zhou K, Wu JX (2020) Typical study on sustainable development in relative poverty areas and policy outlook of China. Bull Chin Acad Sci 35:1249–1263. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20201008001

Fu GM, Tang JF (2022) Is America’s re-industrialization a blessing or a curse: Can two-way FDI promote China’s high-quality economy development? based on the mediating role of industrial structure and technological innovation. J Syst Manag 31:1137–1149

Google Scholar

Gehrke E, Hartwig R (2018) Productive effects of public works programs: What do we know? What should we know? World Dev 107:111–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.031

Gibson J, Olivia S (2010) The effect of infrastructure access and quality on non-farm enterprises in rural Indonesia. World Dev 38:717–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.010

Gong QY, Chen XZ (2018) Digital financial inclusion, rural poverty, and economic growth. Gansu Social Sci :139–145 https://doi.org/10.15891/j.cnki.cn62-1093/c.2018.06.021

Guan R, Xu CH, Yu J (2023) How can the state poverty county policy improve the quality of poverty alleviation in the county? From the perspective of coordinated governance of poverty and income gap. J Macro-Qual Res 11:52–66. https://doi.org/10.13948/j.cnki.hgzlyj.2023.01.005