Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale.

Case topics represented on the list vary widely, but a number are drawn from the case team’s focus on healthcare, asset management, and sustainability. The cases also draw on Yale’s continued emphasis on corporate governance, ethics, and the role of business in state and society. Of note, nearly half of the most popular cases feature a woman as either the main protagonist or, in the case of raw cases where multiple characters take the place of a single protagonist, a major leader within the focal organization. While nearly a fourth of the cases were written in the past year, some of the most popular, including Cadbury and Design at Mayo, date from the early years of our program over a decade ago. Nearly two-thirds of the most popular cases were “raw” cases - Yale’s novel, web-based template which allows for a combination of text, documents, spreadsheets, and videos in a single case website.

Read on to learn more about the top 10 most popular cases followed by a complete list of the top 40 cases of 2017. A selection of the top 40 cases are available for purchase through our online store .

#1 - Coffee 2016

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort

Coffee 2016 asks students to consider the coffee supply chain and generate ideas for what can be done to equalize returns across various stakeholders. The case draws a parallel between coffee and wine. Both beverages encourage connoisseurship, but only wine growers reap a premium for their efforts to ensure quality. The case describes the history of coffee production across the world, the rise of the “third wave” of coffee consumption in the developed world, the efforts of the Illy Company to help coffee growers, and the differences between “fair” trade and direct trade. Faculty have found the case provides a wide canvas to discuss supply chain issues, examine marketing practices, and encourage creative solutions to business problems.

#2 - AXA: Creating New Corporate Responsibility Metrics

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort and David Bach

The case describes AXA’s corporate responsibility (CR) function. The company, a global leader in insurance and asset management, had distinguished itself in CR since formally establishing a CR unit in 2008. As the case opens, AXA’s CR unit is being moved from the marketing function to the strategy group occasioning a thorough review as to how CR should fit into AXA’s operations and strategy. Students are asked to identify CR issues of particular concern to the company, examine how addressing these issues would add value to the company, and then create metrics that would capture a business unit’s success or failure in addressing the concerns.

#3 - IBM Corporate Service Corps

Faculty Supervision: David Bach in cooperation with University of Ghana Business School and EGADE

The case considers IBM’s Corporate Service Corps (CSC), a program that had become the largest pro bono consulting program in the world. The case describes the program’s triple-benefit: leadership training to the brightest young IBMers, brand recognition for IBM in emerging markets, and community improvement in the areas served by IBM’s host organizations. As the program entered its second decade in 2016, students are asked to consider how the program can be improved. The case allows faculty to lead a discussion about training, marketing in emerging economies, and various ways of providing social benefit. The case highlights the synergies as well as trade-offs between pursuing these triple benefits.

#4 - Cadbury: An Ethical Company Struggles to Insure the Integrity of Its Supply Chain

Faculty Supervision: Ira Millstein

The case describes revelations that the production of cocoa in the Côte d’Ivoire involved child slave labor. These stories hit Cadbury especially hard. Cadbury's culture had been deeply rooted in the religious traditions of the company's founders, and the organization had paid close attention to the welfare of its workers and its sourcing practices. The US Congress was considering legislation that would allow chocolate grown on certified plantations to be labeled “slave labor free,” painting the rest of the industry in a bad light. Chocolate producers had asked for time to rectify the situation, but the extension they negotiated was running out. Students are asked whether Cadbury should join with the industry to lobby for more time? What else could Cadbury do to ensure its supply chain was ethically managed?

#5 - 360 State Real Options

Faculty Supervision: Matthew Spiegel

In 2010 developer Bruce Becker (SOM ‘85) completed 360 State Street, a major new construction project in downtown New Haven. Just west of the apartment building, a 6,000-square-foot pocket of land from the original parcel remained undeveloped. Becker had a number of alternatives to consider in regards to the site. He also had no obligation to build. He could bide his time. But Becker worried about losing out on rents should he wait too long. Students are asked under what set of circumstances and at what time would it be most advantageous to proceed?

#6 - Design at Mayo

Faculty Supervision: Rodrigo Canales and William Drentell

The case describes how the Mayo Clinic, one of the most prominent hospitals in the world, engaged designers and built a research institute, the Center for Innovation (CFI), to study the processes of healthcare provision. The case documents the many incremental innovations the designers were able to implement and the way designers learned to interact with physicians and vice-versa.

In 2010 there were questions about how the CFI would achieve its stated aspiration of “transformational change” in the healthcare field. Students are asked what would a major change in health care delivery look like? How should the CFI's impact be measured? Were the center's structure and processes appropriate for transformational change? Faculty have found this a great case to discuss institutional obstacles to innovation, the importance of culture in organizational change efforts, and the differences in types of innovation.

This case is freely available to the public.

#7 - Ant Financial

Faculty Supervision: K. Sudhir in cooperation with Renmin University of China School of Business

In 2015, Ant Financial’s MYbank (an offshoot of Jack Ma’s Alibaba company) was looking to extend services to rural areas in China by providing small loans to farmers. Microloans have always been costly for financial institutions to offer to the unbanked (though important in development) but MYbank believed that fintech innovations such as using the internet to communicate with loan applicants and judge their credit worthiness would make the program sustainable. Students are asked whether MYbank could operate the program at scale? Would its big data and technical analysis provide an accurate measure of credit risk for loans to small customers? Could MYbank rely on its new credit-scoring system to reduce operating costs to make the program sustainable?

#8 - Business Leadership in South Africa’s 1994 Reforms

Faculty Supervision: Ian Shapiro

This case examines the role of business in South Africa's historic transition away from apartheid to popular sovereignty. The case provides a previously untold oral history of this key moment in world history, presenting extensive video interviews with business leaders who spearheaded behind-the-scenes negotiations between the African National Congress and the government. Faculty teaching the case have used the material to push students to consider business’s role in a divided society and ask: What factors led business leaders to act to push the country's future away from isolation toward a "high road" of participating in an increasingly globalized economy? What techniques and narratives did they use to keep the two sides talking and resolve the political impasse? And, if business leadership played an important role in the events in South Africa, could they take a similar role elsewhere?

#9 - Shake Shack IPO

Faculty Supervision: Jake Thomas and Geert Rouwenhorst

From an art project in a New York City park, Shake Shack developed a devoted fan base that greeted new Shake Shack locations with cheers and long lines. When Shake Shack went public on January 30, 2015, investors displayed a similar enthusiasm. Opening day investors bid up the $21 per share offering price by 118% to reach $45.90 at closing bell. By the end of May, investors were paying $92.86 per share. Students are asked if this price represented a realistic valuation of the enterprise and if not, what was Shake Shack truly worth? The case provides extensive information on Shake Shack’s marketing, competitors, operations and financials, allowing instructors to weave a wide variety of factors into a valuation of the company.

#10 - Searching for a Search Fund Structure

Faculty Supervision: AJ Wasserstein

This case considers how young entrepreneurs structure search funds to find businesses to take over. The case describes an MBA student who meets with a number of successful search fund entrepreneurs who have taken alternative routes to raising funds. The case considers the issues of partnering, soliciting funds vs. self-funding a search, and joining an incubator. The case provides a platform from which to discuss the pros and cons of various search fund structures.

40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

Click on the case title to learn more about the dilemma. A selection of our most popular cases are available for purchase via our online store .

What is Strategic Analysis? 8 Best Strategic Analysis Tools + Examples

A huge part of developing a strategic plan is a reliable, in-depth strategic analysis. An organization is separated into internal and external environments. Both components should be scrutinized to identify factors influencing organizations and guiding decision-making.

In this article, we'll cover:

What Is Strategic Analysis?

Types of strategic analysis, benefits of strategic analysis for strategy formulation, strategic analysis example - walmart, how to do a strategic analysis: key components, strategic analysis tools, how to choose the right strategic analysis tool, the next step: from analysis to action with cascade 🚀.

⚠️ Remember, insights aren't enough! Understanding your internal & external environment is vital, but true strategy comes from action. Cascade Strategy Execution Platform bridges the gap between analysis and execution. Talk to our strategy experts to turn your strategic analysis into a winning roadmap with clear goals and measurable results.

Strategic analysis is the process of researching and analyzing an organization along with the business environment in which it operates to formulate an effective strategy. This process of strategy analysis usually includes defining the internal and external environments, evaluating identified data, and utilizing strategic analysis tools.

By conducting strategic analysis, companies can gain valuable insights into what's working well and what areas need improvement. These valuable insights become key inputs for the strategic planning process , helping businesses make well-informed decisions to thrive and grow.

When it comes to strategic analysis, businesses employ different approaches to gain insights into their inner workings and the external factors influencing their operations.

Let's explore two key types of strategic analysis:

Internal strategic analysis

The focus of internal strategic analysis is on diving deep into the organization's core. It involves a careful examination of the company's strengths, weaknesses, resources, and competencies. By conducting a thorough assessment of these aspects, businesses can pinpoint areas of competitive advantage, identify potential bottlenecks, and uncover opportunities for improvement.

This introspective analysis acts as a mirror , reflecting the organization's current standing, and provides valuable insights to shape the path that will ultimately lead to achieving its mission statement.

External strategic analysis

On the other hand, external strategic analysis zooms out to consider the broader business environment. This entails conducting market analysis, trend research, and understanding customer behaviors, regulatory changes, technological advancements, and competitive forces. By understanding these external dynamics, organizations can anticipate potential threats and uncover opportunities that can significantly impact their strategic decision-making.

The external strategic analysis acts as a window , offering a view of the ever-changing business landscape.

The analysis phase sets “the stage” for your strategy formulation.

The strategic analysis informs the activities you undertake in strategic formulation and allows you to make informed decisions. This phase not only sets the stage for the development of effective business planning but also plays a crucial role in accurately framing the challenges to be addressed.

These are some benefits of strategic analysis for strategy formulation:

- Holistic View : Gain a comprehensive understanding of internal capabilities, the external landscape, and potential opportunities and threats.

- Accurate Challenge Framing : Identify and define core challenges accurately, shaping the strategy development process.

- Proactive Adaptation : Anticipate potential bottlenecks and areas for improvement, fostering proactive adaptability.

- Leveraging Strengths : Develop strategies that maximize organizational strengths for a competitive advantage.

At the very least, the right framing can improve your understanding of your competitors and, at its best, revolutionize an industry. For example, everybody thought that the early success of Walmart was due to Sam Walton breaking the conventional wisdom:

“A full-line discount store needs a population base of at least 100,000.”

But that’s not true.

Sam Walton didn’t break that rule, he redefined the idea of the “store,” replacing it with that of a “network of stores.” That led to reframing conventional wisdom, developing a coherent strategy, and revolutionizing an industry.

📚 Check out our #StrategyStudy: How Walmart Became The Retailer Of The People

%20(1).jpg)

Strategy is not a linear process.

Strategy is an iterative process where strategic planning and execution interact with each other constantly.

First, you plan your strategy, and then you implement it and constantly monitor it. Tracking the progress of your initiatives and KPIs (key performance indicators) allows you to identify what's working and what needs to change. This feedback loop guides you to reassess and readjust your strategic plan before proceeding to implementation again. This iterative approach ensures adaptability and enhances the strategy's effectiveness in achieving your goals.

Strategic planning includes the strategic analysis process.

The content of your strategic analysis varies, depending on the strategy level at which you're completing the strategic analysis.

For example, a team involved in undertaking a strategic analysis for a corporation with multiple businesses will focus on different things compared to a team within a department of an organization.

But no matter the team or organization's nature, whether it's a supply chain company aiming to enhance its operations or a marketing team at a retail company fine-tuning its marketing strategy, conducting a strategic analysis built on key components establishes a strong foundation for well-informed and effective decision-making.

The key components of strategic analysis are:

Define the strategy level for the analysis

- Complete an internal analysis

- Complete an external analysis

Unify perspectives & communicate insights

%20(1).jpg)

Strategy comes in different levels depending on where you are in an organization and your organization's size.

You may be creating a strategy to guide the direction of an entire organization with multiple businesses, or you may be creating a strategy for your marketing team. As such, the process will differ for each level as there are different objectives and needs.

The three strategy levels are:

- Corporate Strategy

- Business Strategy

- Functional Strategy

👉🏻If you're not sure which strategy level you're completing your strategy analysis for, read this article explaining each of the strategy levels .

Conduct an internal analysis

As we mentioned earlier, an internal analysis looks inwards at the organization and assesses the elements that make up the internal environment. Performing an internal analysis allows you to identify the strengths and weaknesses of your organization.

Let's take a look at the steps involved in completing an internal analysis:

1. Assessment of tools to use

First, you need to decide what tool or framework you will use to conduct the analysis.

You can use many tools to assist you during an internal analysis. We delve into that a bit later in the article, but to give you an idea, for now, Gap Analysis , Strategy Evaluation , McKinsey 7S Model , and VRIO are all great analysis techniques that can be used to gain a clear picture of your internal environment.

2. Research and collect information

Now it’s time to move into research . Once you've selected the tool (or tools) you will use, you will start researching and collecting data.

The framework you use should give you some structure around what information and data you should look at and how to draw conclusions.

3. Analyze information

The third step is to process the collected information. After the data research and collection stage, you'll need to start analyzing the data and information you've gathered.

How will the data and information you've gathered have an impact on your business or a potential impact on your business? Looking at different scenarios will help you pull out possible impacts.

4. Communicate key findings

The final step of an internal analysis is sharing your conclusions . What is the value of your analysis’ conclusions if nobody knows about them?

You should be communicating your findings to the rest of the team involved in the analysis and go even further. Share relevant information with the rest of your people to demonstrate that you trust them and offer context to your decisions.

Once the internal analysis is complete , the organization should have a clear idea of where they're excelling, where they're doing OK, and where current deficits and gaps lie.

The analysis provides your leadership team with valuable insights to capitalize on strengths and opportunities effectively. It also empowers them to devise strategies that address potential threats and counteract identified weaknesses.

Beginning strategy formulation after this analysis will ensure your strategic plan has been crafted to take advantage of strengths and opportunities and offset or improve weaknesses & threats. This way, the strategic management process remains focused on the identified priorities, enabling a well-informed and proactive approach to achieving your organizational goals.

You can then be confident that you're funneling your resources, time, and focus effectively and efficiently.

Conduct an external analysis

As we stated before, the other type of strategic analysis is the external analysis which looks at an organization's environment and how those environmental factors currently impact or could impact the organization.

A key difference between the external and the internal factors lies in the organization's level of control.

Internally, the organization wields complete control and can actively influence these factors. On the other hand, external components lie beyond the organization's direct control, and the focus is on scanning and reacting to the environment rather than influencing it.

External factors of the organization include the industry the organization competes in, the political and legal landscape the organization operates in, and the communities they operate in.

The steps for conducting an external analysis are much the same as an internal analysis:

- Assessment of tools to use

- Research and collect information

- Analyze information

- Communicate key findings

You'll want to use a tool such as SWOT analysis , PESTLE analysis , or Porter's Five Forces to help you add some structure to your analysis. We’ll dive into the tools in more detail further down this article!

Chances are, you didn't tackle the entire analysis alone. Different team members likely took responsibility for specific parts, such as the internal gap analysis or external environmental scan. Each member contributed valuable insights, forming a mosaic of information.

To ensure a comprehensive understanding, gather feedback from all team members involved. Collate all the data and share the complete picture with relevant stakeholders across your organization.

Much like strategy, this information is useless if not shared with everyone.

Remember : There is no such thing as overcommunication.

If you have to keep only one rule of communication, it’s that one. Acting on the insights and discoveries distilled from the analysis is what gives them value. Communicating those findings with your employees and all relevant (internal and external) stakeholders enables acting on them.

Setting up a central location where everyone can access the data should be your first step, but it shouldn't end there. Organize a meeting to go through all the key findings and ensure everyone is on the same page regarding the organization's environment.

There are a number of strategic analysis tools at your disposal. We'll show you 8 of the best strategic analysis tools out there.

.jpg)

The 8 best strategic analysis tools:

Gap analysis, vrio analysis, four corners analysis, value chain analysis.

- SWOT Analysis

Strategy Evaluation

Porter's five forces, pestel analysis.

Note: Analytical tools rely on historical data and prior situations to infer future assumptions. With this in mind, caution should always be used when making assumptions based on your strategic analysis findings.

The Gap Analysis is a great internal analysis tool that helps you identify the gaps in your organization, impeding your progress towards your objectives and vision.

The analysis gives you a process for comparing your organization's current state to its desired future state to draw out the current gaps, which you can then create a series of actions that will bridge the identified gap.

The gap analysis approach to strategic planning is one of the best ways to start thinking about your goals in a structured and meaningful way and focuses on improving a specific process.

👉 Grab your free Gap Analysis template to streamline the process!

The VRIO Analysis is an internal analysis tool for evaluating your resources.

It identifies organizational resources that may potentially create sustainable competitive advantages for the organization. This analysis framework gives you a process for categorizing the resources in your organization based on whether they hold certain traits: Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Organized.

The framework then encourages you to begin thinking about moving those resources to the “next step'' to ultimately develop those resources into competitive advantages.

👉 Grab your free VRIO strategy template that will help you to develop and execute a strategy based on your VRIO analysis.

The Four Corners Analysis framework is another internal analysis tool that focuses on your organization's core competencies.

However, what differentiates this tool from the others is its long-term focus. To clarify, most of the other tools evaluate the current state of an entity, but the Four Corners Analysis assesses the company’s future strategy, which is more precise because it makes the corporation one step ahead of its competitors.

By using the Four Corners, you will know your competitors’ motivation and their current strategies powered by their capabilities. This analysis will aid you in formulating the company’s trend or predictive course of action.

Similar to VRIO, the Value Chain Analysis is a great tool to identify and help establish a competitive advantage for your organization.

The Value Chain framework achieves this by examining the range of activities in the business to understand the value each brings to the final product or service.

The concept of this strategy tool is that each activity should directly or indirectly add value to the final product or service. If you are operating efficiently, you should be able to charge more than the total cost of adding that value.

A SWOT analysis is a simple yet ridiculously effective way of conducting a strategic analysis.

It covers both the internal and external perspectives of a business.

When using SWOT, one thing to keep in mind is the importance of using specific and verifiable statements. Otherwise, you won’t be able to use that information to inform strategic decisions.

👉 Grab your free SWOT Analysis template to streamline the process!

Generally, every company will have a previous strategy that needs to be taken into consideration during a strategic analysis.

Unless you're a brand new start-up, there will be some form of strategy in the company, whether explicit or implicit. This is where a strategy evaluation comes into play.

The previous strategy shouldn't be disregarded or abandoned, even if you feel like it wasn't the right direction or course of action. Analyzing why a certain direction or course of action was decided upon will inform your choice of direction.

A Strategic Evaluation looks into the strategy previously or currently implemented throughout the organization and identifies what went well, what didn't go so well, what should not have been there, and what could be improved upon.

👉To learn more about this analysis technique, read our detailed guide on how to conduct a comprehensive Strategy Evaluation .

Complementing an internal analysis should always be an analysis of the external environment, and Porter's Five Forces is a great tool to help you achieve this.

Porter's Five Forces framework performs an external scan and helps you get a picture of the current market your organization is playing in by answering questions such as:

- Why does my industry look the way it does today?

- What forces beyond competition shape my industry?

- How can I find a position among my competitors that ensures profitability?

- What strategies can I implement to make this position challenging for them to replicate?

With the answer to the above questions, you'll be able to start drafting a strategy to ensure your organization can find a profitable position in the industry.

👉 Grab your free Porter’s 5 Forces template to implement this framework!

We might sound repetitive, but external analysis tools are critical to your strategic analysis.

The environment your organization operates in will heavily impact your organization's success. PESTEL analysis is one of the best external analysis tools you can use due to its broad nature.

The name PESTEL is an acronym for the elements that make up the framework:

- Technological

- Environmental

Basically, the premise of the analysis is to scan each of the elements above to understand the current status and how they can potentially impact your industry and, thus, your organization.

PESTEL gives you extra focus on certain elements that may have a wide-ranging impact, and a birds-eye view of the macro-environmental factors.

There are as many ways to do strategy as there are organizations. So not every tool is appropriate for every organization.

These 8 tools are our top picks for giving you a helping hand through your strategic analysis. They're by no means the whole spectrum. There are many other frameworks and tools out there that could be useful and provide value to your process.

Choose the tools that fit best with your approach to doing strategy. Don’t limit yourself to one tool if it doesn’t make sense, don’t be afraid to combine them, mix and match! And, be faithful to each framework but always as long as it fits your organization’s needs.

Completing the strategic analysis phase is a crucial milestone, but it's only the beginning of a successful journey. Now comes the vital task of formulating a plan and ensuring its effective execution. This is where Cascade comes into play, offering a powerful solution to drive your strategy forward.

Cascade is your ultimate partner in strategy execution. With its user-friendly interface and robust features, it empowers you to translate the strategic insights distilled from your strategic analysis into actionable plans.

Some key features include:

- Planner : Seamlessly build out your objectives, initiatives, and key performance indicators (KPIs) while aligning them with the organization's goals. Break down the complexity from high-level initiative to executable outcomes.

- Alignment Map : Visualize how different organizational plans work together and how your corporate strategy breaks down into operational and functional plans.

%20(1).png)

- Metrics & Measures : Connect your business data directly to your core initiatives in Cascade for clear data-driven alignment.

.png)

- Integrations : Consolidate your business systems underneath a unified roof. Import context in real-time by leveraging Cascade’s native, third-party connector (Zapier/PA), and custom integrations.

- Dashboards & Reports : Stay informed about your strategy's performance at every stage with Cascade's real-time tracking and progress monitoring, and share it with your stakeholders, suppliers, and contractors.

Experience the power of Cascade today! Sign up today for a free forever plan or book a guided 1:1 tour with one of our Cascade in-house strategy execution experts.

Popular articles

Viva Goals Vs. Cascade: Goal Management Vs. Strategy Execution

What Is A Maturity Model? Overview, Examples + Free Assessment

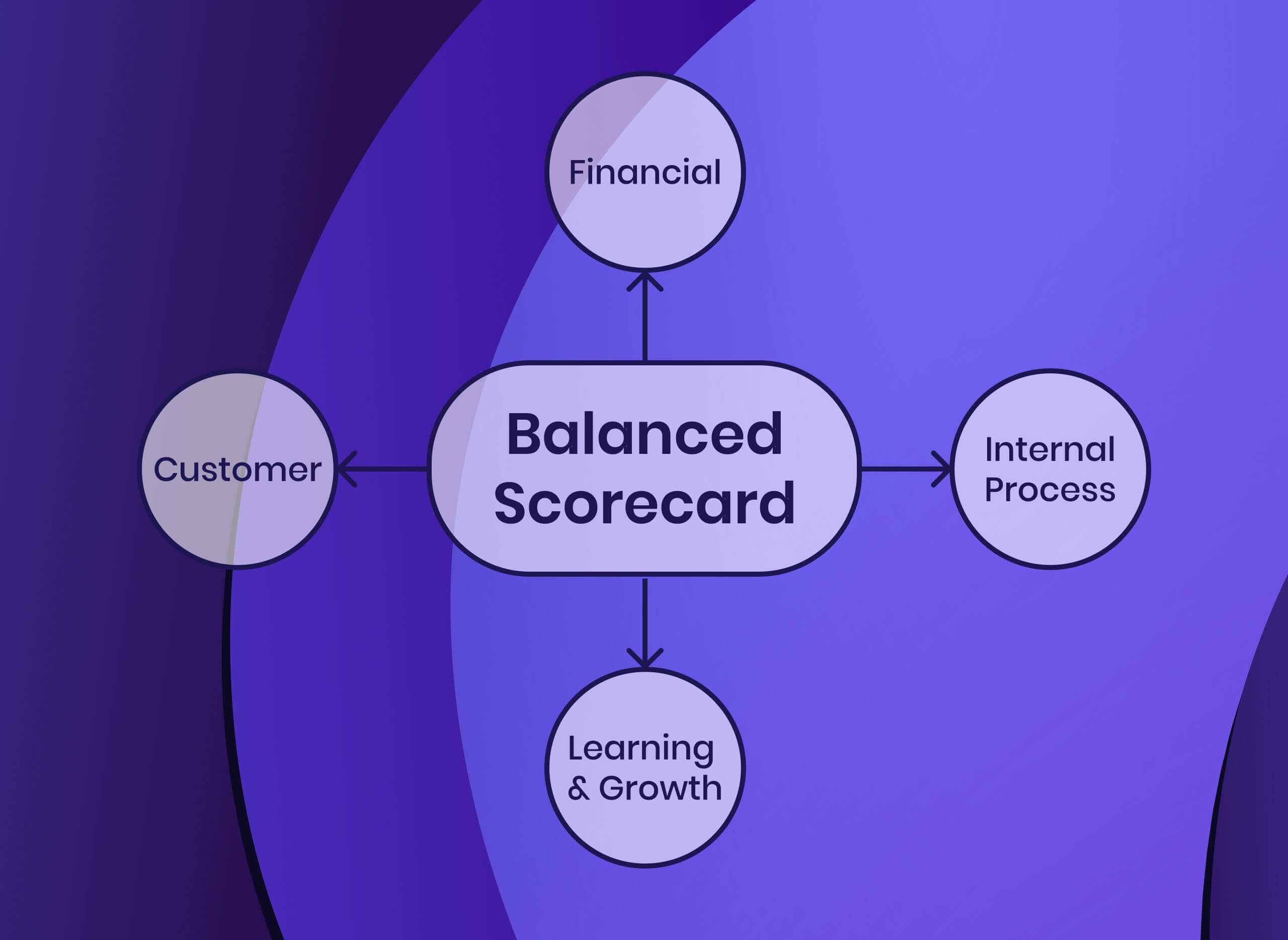

How To Implement The Balanced Scorecard Framework (With Examples)

The Best Management Reporting Software For Strategy Officers (2024 Guide)

Your toolkit for strategy success.

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Teaching Resources Library

Strategy Case Studies

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Strategic analysis

- Change management

- Competitive strategy

- Corporate strategy

- Customer strategy

Your Strategy Needs a Strategy

- Martin Reeves

- Claire Love

- Philipp Tillmanns

- From the September 2012 Issue

Lean Strategy

- David J. Collis

- From the March 2016 Issue

Create and Deliver a Strong Business Case

- June 25, 2015

Juggling Growth and Brand Identity

- Harvard Business Publishing

- Seth Goldman

- November 12, 2013

What Is Strategy?

- Michael E. Porter

- From the November–December 1996 Issue

Defining Strategy, Implementation, and Execution

- March 31, 2015

Are You Solving the Right Problem?

- Dwayne Spradlin

Building a Game-Changing Talent Strategy

- Douglas A. Ready

- Linda A. Hill

- Robert J. Thomas

- From the January–February 2014 Issue

Mission and Objectives

- Robert Steven Kaplan

- April 01, 2011

Saving Money, Saving Lives

- Jon Meliones

- From the November–December 2000 Issue

Making Your Ideas Credible

- Prashant Pundrik

- March 07, 2011

The Explainer: The Balanced Scorecard

- Robert S. Kaplan

- David P. Norton

- October 14, 2014

Is the Business of America Still Business?

- Niall Ferguson

- From the June 2013 Issue

How People Analytics Can Help You Change Process, Culture, and Strategy

- Chantrelle Nielsen

- Natalie McCullough

- May 17, 2018

Look Beyond Obvious Risks

- Mihir A. Desai

- June 16, 2015

Strategy: The Uniqueness Challenge

- Todd Zenger

- From the November 2013 Issue

The Balanced Scorecard—Measures that Drive Performance

- From the January–February 1992 Issue

The Best-Performing CEOs in the World

- Morten T. Hansen

- Herminia Ibarra

- From the January–February 2013 Issue

Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work

- From the September–October 1993 Issue

How Emerging Giants Can Take on the World

- John Jullens

- From the December 2013 Issue

Can GenAI Do Strategy?

- Michael Olenick

- Peter Zemsky

- November 24, 2023

Optimizing the Supply Chain by Aligning the Planning and Sourcing Functions

- May 03, 2023

Do You Really Understand Your Best (and Worst) Customers?

- Peter Fader

- Bruce G.S. Hardie

- Michael Ross

- December 23, 2022

Navigating the Data Deluge

- November 30, 2022

Using Value Stream Management to Speed Digital Transformation and Eliminate Silos

- November 22, 2022

Partnering in Complex Times: Turning to the Experts for Best-In-Class Customer Experience

- November 07, 2022

Two Questions to Ask Before Setting Your Strategy

- Annelies O’Dea

- June 28, 2022

5 Ways the Best Companies Close the Strategy-Execution Gap

- Michael Mankins

- November 20, 2017

Your Strategy Has to Be Flexible - But So Does Your Execution

- Rodolphe Charme di Carlo

- November 14, 2017

Developing Network Relationships: Part 1

- April 30, 2017

Whiteboard Session: 5 Principles for Innovation in Emerging Markets

- Efosa Ojomo

- April 12, 2017

A Good Digital Strategy Creates a Gravitational Pull

- Mark Bonchek

- January 25, 2017

The Explainer: Core Competence

- C.K. Prahalad

- September 29, 2016

Strategic Plans Are Less Important than Strategic Planning

- Graham Kenny

- June 21, 2016

Balancing Opportunity and Uncertainty

- Tomislav Mihaljevic

- June 10, 2016

How to Live with Risks

- Harvard Business Review

- From the July–August 2015 Issue

Experiment to Learn About Your Market

- Robyn Bolton

Mobil USM&R (A1)

- June 26, 1997

Cashing Out: The Future of Cash in Israel

- Benjamin Gilles

- January 29, 2018

Dilli Haat: Reviving Lost Glory

- Amita Mital

- July 10, 2017

Strategy Execution Module 9: Building a Balanced Scorecard

- Robert Simons

- November 20, 2016

Locally Laid Egg Company: No Time for Laying Around

- Rajiv Vaidyanathan

- Ahmed Maamoun

- April 01, 2018

SCI Ontario: Achieving, Measuring and Communicating Strategic Success

- Neil Bendle

- November 07, 2014

Voice War: Hey Google vs. Alexa vs. Siri

- David B. Yoffie

- Jodie Sweitzer

- Denzil Eden

- Karan Ahuja

- June 07, 2018

Otago Museum

- Ralph Adler

- June 01, 2010

World Trade Organization: Toward Free Trade or World Bureaucracy?

- George C. Lodge

- April 11, 1995

Four Steps to Effective Decisions

- July 30, 2018

Measuring the Financial Performance of Nonprofit Organizations: Text and Cases

- Regina E. Herzlinger

- May 19, 1997

Paramount Equipment

- Carliss Y. Baldwin

- July 08, 2014

Mobil USM&R (A2)

- June 20, 1997

Transworld Auto Parts (A)

- V.G. Narayanan

- August 08, 2011

United Way of Southeastern New England (UWSENE)

- Ellen L. Kaplan

- November 14, 1996

SMA: Micro-Electronic Products Division (B)

- Michael Beer

- Michael L. Tushman

- May 10, 2000

Strategic Performance Measurement of Suppliers at HTC

- Neale O'Connor

- Shannon Anderson

- June 09, 2011

The Pub: Survive, Thrive or Die?

- Gina Grandy

- Moritz P Gunther

- Andrew Couturier

- Ben Goldberg

- Ian MacLeod

- Trevor Steeves

- January 15, 2010

City of Charlotte (A)

- December 15, 1998

Economy Shipping Co. (Abridged)

- Thomas R. Piper

- November 01, 1973

Can a Positive Approach to Performance Evaluation Help Accomplish Your Goals?

- Karen S. Cravens

- Elizabeth Goad Oliver

- Jeanine S. Stewart

- May 15, 2010

Building a Co-Creative Performance Management System

- Venkat Ramaswamy

- Francis J. Gouillart

- March 15, 2011

Presenting the Balanced Scorecard Strategy Map

- Robert S. Gold

- July 15, 2004

Four Steps for Integrating Strategic Risk Management into Your Strategy Review Process

- Edward A. Barrows Jr.

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Order Status

- Testimonials

- What Makes Us Different

Case Analysis: Strategic Leadership at Coca Cola: The Real Thing Harvard Case Solution & Analysis

Home >> Harvard Case Study Analysis Solutions >> Case Analysis: Strategic Leadership at Coca Cola: The Real Thing

Case Analysis: Strategic Leadership at Coca Cola: The Real Thing Case Solution

Introduction

Leadership plays an important role in success of a company since leaders are the people who motivate people to achieve their targets, goals, and objectives. Moreover, there are two types of leaderships; the first type is the normal leadership under which the leader only motivates his fellows or followers in order to achieve the respective targets, while the second type is the strategic leadership, which is mostly followed in large organizations. (Riaz, 2008)

Strategic leadership allows the organization to respond to new opportunities and set targets accordingly in order to achieve those milestones and these type of leaders also motivate their followers to draw targets and objectives in short term to achieve the ultimate objective. This type of leadership plays a very crucial role in the organization, as it helps the company in responding to change and decides the growth of the company.

In addition, these types of leaders are also responsible for the growth and success of the company while they are also responsible for the side effects of any proposed strategy. Moreover, these types of leaders help the company to increase its core competencies in order to achieve competitive advantage over rivals. (ilm.com, 2010)

Furthermore, six components form the bottom line for strategic leadership since strategic leadership is useless until these milestones are not achieved. The first component of the strategic leadership is the creation of vision and mission; this is the first step, which guides the leader as well as the followers for what they are working. The next step includes the development of core competencies (those capabilities, which are not mentioned in the balance sheet of the company, but are those strengths of the company, which cannot be imitated by rivals easily). The third component is investment in human capital by training and facilitating the employees to achieve the ultimate objective.

Furthermore, the fourth step is to ensure sustainable organizational culture; since, without a perfect organizational structure, none of the visions can be achieved. Afterwards, the next job of strategic leadership is to ensure ethical practices and finally, the last step of strategic leadership is to ensure balanced organizational culture.

Leadership VS Strategic Leadership

There are several differences among both of the leadership approaches. However, the main difference, which is very helpful to understand the different aspects of both the approaches, is that under leadership , the leader can ask for any objective to be achieved at any level of the company. While strategic leadership belongs to the top management of the company. Therefore, it can be seen that strategic leadership is more crucial for any firm.

Leadership Styles

As highlighted in the case, there are three different types of leadership styles at strategic level of the company. The first style is the managerial leaders, the second type of leaders is visionary leaders, and the third category includes strategic leaders. However, these styles are not attached only with the top management of the company, but with the middle level management as well. (Riaz, 2008)

Managerial Leaders

These types of leaders only see themselves as the mediator of orders and rules from top management to middle and low-level hierarchy of the company . This type of managers motivate and encourage the front-core staff to achieve the goals and objectives set by them however, these leaders do not set the objective as per their desires or dreams and they do not do anything fancy in making changes from the orders received from the top management . In addition, these types of leaders are more focused towards the target competition in ways that are more traditional since they do not work to find out new and innovative ways to reduce the efforts for achieving maximum results. (Riaz, 2008)...................

This is just a sample partial case solution . Please place the order on the website to order your own originally done case solution.

Related Case Solutions & Analyses:

Hire us for Originally Written Case Solution/ Analysis

Like us and get updates:.

Harvard Case Solutions

Search Case Solutions

- Accounting Case Solutions

- Auditing Case Studies

- Business Case Studies

- Economics Case Solutions

- Finance Case Studies Analysis

- Harvard Case Study Analysis Solutions

- Human Resource Cases

- Ivey Case Solutions

- Management Case Studies

- Marketing HBS Case Solutions

- Operations Management Case Studies

- Supply Chain Management Cases

- Taxation Case Studies

More From Harvard Case Study Analysis Solutions

- Cycle for Survival

- FINANCE ASSIGNMENT

- International Trachoma Initiative

- Brandless: Alter Packed Consumer Goods

- Good Water and Good Plastic

- TerraCycle (A): Building a Venture With Spineless Employees

- Succession Planning: Surviving the Next Generation

Contact us:

Check Order Status

How Does it Work?

Why TheCaseSolutions.com?

Case Studies

Since its acquisition by BMW Group, MINI has retained a strong independent sense of brand identity. MINI Plant Oxford wanted to create a strong leadership culture that built on the mix of heritage, was aligned to BMW Group, but was also uniquely their own. MINI Plant Oxford now faced several challenges.

See the case study to view these challenges in details and our collaborate approach to solving these and the fabulous results obtained.

GLOBAL PHARMA & DIAGNOSTICS

About 500 managers within an organisation that is a global player in the Pharma/Diagnostics industry were the target audience. These Technical Product Managers (TPMs) are highly educated, qualified specialists, who have to juggle technical content and stakeholder relationships as well as leading project teams. Therefore, they face increasing non-technical responsibilities and challenges like financial pressure and shrinking R&D budgets. Because of the complex organisational matrix and the international nature of the environment in which they operate, TPMs need to constantly gain more skills to keep up with the pace of change. They need to improve worldwide collaboration and at the same time still ensure high service quality expectations – holding a technical qualification alone is not enough. Non-product-related soft skills increasingly need to be improved and enhanced for long-term business and career success.

As a result of this pressing need, Strategic Leadership designed an intense development programme known as the TPM Academy. See the case study to view our collaborate approach the results obtained.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Strategic Management (BUS 411) Case study & analysis

Related Papers

Hiba Sellaoui

Phuong Pham

Anthony Olabode Ayodele (Bode Ayodele)

Artur Twardowski

DASH | Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Irene Cieraad

Asia Pacific Journal of Management and Education

AJAY MASSAND

Consumer behavior is the study of consumers and the processes they use to choose, apply and dispose of products and services, including consumers’ emotional and behavioral responses. IKEA is a multinational home furnishings company founded in 1943 in Sweden that has grown rapidly. They manage to produce their products and services more widespread not only based on price but create a unique shopping experience. This study aims to examine the factors that affect consumer behavior in IKEA. Various factors like social factors, wide products assortment, price and others are investigated to analyze consumer behavior of IKEA’s customers. Likert Scale was used to get the final results from the questionnaire filled out by the respondents. The questionnaires were distributed to 250 respondents who use IKEA products. The Likert scale will be used to measure a person's perception and attitude or opinion. The results showed that they chose IKEA due to the cost-advantages and wide products as...

Allan Onyango

Pricing is an important element in business, and an appropriate pricing strategy is elementary for any business to see successful operations. Pricing affects the acceptability of the product and determines the growth rate of the brand in the market (Pan et al., 2018). For IKEA, the factors that influence the pricing range from customer needs, competitor strategies, and environmental elements. IKEA, being a well-developed brand with more than 48 suppliers in India alone, feels the challenge posed by these factors and the impact they have on its target market.

Shaik Nabil

Kevin Zentner , Rachel Killoh , Zhen Sun

Ikea is a worldwide success story; their stores were visited 915 million times and their website was accessed over 2 billion times in 2016 (Highlights, 2016). As the world’s largest furniture retailer, Ikea services a number of market segments. With significant volume discounts and a vertically integrated supply chain, the production of low-cost goods target young families and low income segments. Conversely, the flagship Stockholm line of furniture entices sophisticated consumers towards mid-priced, superior value products with quality materials such as walnut, bone china, and rustic grain leather.

Norman Meuschke

This paper presents an innovative concept for functional, low-priced, privately-owned housing products called BoKlok and analyses the development as well as the commercialization of this concept as a joint effort of the home furnishing company IKEA and the international construction enterprise Skanska. In the first chapter a short review on academic theory related to the paper is offered. In the second chapter the named housing products are introduced to the reader, their innovative characteristics are pointed out and an overview about the history of the concept as well as the current state of business related to the BoKlok products is given. In the third chapter the business model that is applied for merchandising BoKlok homes is analysed in detail. Chapter four and five each present a general overview about the companies IKEA and Skanska, which cooperated in the development project for the BoKlok concept. The development process as such is reviewed explicitly in chapter six. In chapter seven factors that significantly influenced the project results are identified and discussed in respect to relevant academic findings. Chapter eight illustrates how the BoKlok concept is continuously developed further in the present. The work concludes with providing some future perspectives for the concept in chapter nine.

Building resilience: analysis of health care leaders’ perspectives on the Covid-19 response in Region Stockholm

- Carl Savage 1 ,

- Leonard Tragl 1 ,

- Moa Malmqvist Castillo 1 ,

- Louisa Azizi 1 ,

- Henna Hasson 1 , 2 ,

- Carl Johan Sundberg 1 , 3 &

- Pamela Mazzocato 1 , 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 408 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

115 Accesses

Metrics details

The Covid-19 pandemic has tested health care organizations worldwide. Responses have demonstrated great variation and Sweden has been an outlier in terms of both strategy and how it was enacted, making it an interesting case for further study. The aim of this study was to explore how health care leaders experienced the challenges and responses that emerged during the initial wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, and to analyze these experiences through an organizational resilience lens.

A qualitative interview study with 12 senior staff members who worked directly with or supervised pandemic efforts. Transcripts were analyzed using traditional content analysis and the codes directed to the Integrated Resilience Attributes Framework to understand what contributed to or hindered organizational resilience, i.e. how organizations achieve their goals by utilizing existing resources during crises.

Results/Findings

Organizational resilience was found at the micro (situated) and meso (structural) system levels as individuals and organizations dealt with acute shortages and were forced to rapidly adapt through individual sacrifices, resource management, process management, and communications and relational capacity. Poor systemic resilience related to misaligned responses and a lack of learning from previous experiences, negatively impacted the anticipatory phase and placed greater pressure on individuals and organizations to respond. Conventional crisis leadership could hamper innovation, further cement chronic challenges, and generate a moral tension between centralized directives and clinical microsystem experiences.

Conclusions

The pandemic tested the resilience of the health care system, placing undue pressure on micro and meso systems responses. With improved learning capabilities, some of this pressure may be mitigated as it could raise the anticipatory resilience potential, i.e. with better health systems learning, we may need fewer heroes. How crisis leadership could better align decision-making with frontline needs and temper short-term acute needs with a longer-term infinite mindset is worth further study.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic tested health care organizations worldwide [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The rapid spread and high patient volumes bore with them a continual threat to overrun health systems, particularly within acute care [ 6 ]. Shortages in personal protective equipment (PPE), medications, ventilators, ICU and ward beds, staff, and morgue space were commonplace [ 7 ]. Staff experienced extraordinary physical and emotional demands, compounded by treatment uncertainties, ethical dilemmas, fear of becoming infected or infecting others [ 8 ]. Altogether, the challenges to health systems were multiple, urgent, and very real.

A pandemic is an unexpected disturbance of daily health care operations and can be described as a “low-chance, high-impact” (albeit inevitable and recurring) event [ 9 , 10 ]. In these situations of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, research suggests that even our best-laid schemes (often) go awry [ 11 , 12 ]. Instead, health systems need to be resilient, agile, and improvise to respond effectively by increasing autonomy, maintaining structure, and creating a shared understanding [ 13 ]. Therefore, organizational resilience may provide a relevant framework to understand the response of health care organizations to the pandemic [ 13 ].

Many organizations demonstrated the capability to innovate, partner with others, develop virtual care solutions, e.g. video and phone consultations, eVisits, eConsults, and chatbot messaging– all of which have seen widespread adoption [ 14 , 15 ]. Others became frustrated by the slow response to acute challenges and perceived a lack of coherence in resource supply chains, recommendations, and treatment guidelines. Global uncertainties were addressed by local actions as managers and health care professionals took extraordinary measures to solve problems. As these examples illustrate, and Ashby’s “Law” of Requisite Variety dictates, low-chance, high-impact events require multi-level responses that are of a matching level of complexity [ 16 ]. Thus, local health care solutions are impacted by national public health and political strategies, which in turn are often dependent on international decisions.

Sweden has been an outlier in its choice of response (fewer mandatory restrictions) and timing (often later) in comparison with many other countries, even if physical mobility and social behavioral patterns were similar [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. For example, lockdowns were avoided, far fewer restrictions were introduced, and they were less restrictive. The focus was on voluntary compliance to the governmental recommendations of social distancing, working from home, and mask use in crowded areas. Adherence to guidelines was high. Covid passes were only introduced for travel and there were no restrictions on outdoor activities. These national strategies themselves are worth studying, as are the strategies of Swedish health care providers working in this context. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore how health care leaders experienced the challenges and responses that emerged during the initial wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, and to analyze these experiences through an organizational resilience lens.

Study design

We employed a qualitative interview study design to inductively explore the challenges and responses. Upon reviewing the findings, we identified patterns that could be further analyzed through a resilience lens. We therefore directed the empirical findings to the Integrated Resilience Attributes Framework to abduct, i.e. logically infer, how they contributed to organizational resilience [ 20 , 21 ].

Theoretical framework

Resilience refers to the ability to utilize existing resources in the face of a crisis [ 22 ]. It can be seen as an organization’s ability to recover and regain its original functions after a period of stress. Through the advancement and development of processes and capabilities, the organization can exit the crisis stronger than before. A key component is predictive planning, i.e. the ability to anticipate the arrival of a crisis. This suggests that resilience is more than merely a defensive posturing that promotes survival, but an active response that engenders development.

Organizational resilience can be conceptualized as consisting of spatial and temporal moments [ 23 ]. It is located at different levels, i.e. the micro, meso, and macro (system) levels. These can be described as situated, structural, and system versions of resilience. Situated resilience involves the (immediate) use and combination of existing socio-technical resources. Structural resilience involves a mid-term (weeks to years) deliberate restructuring and redesign of socio-technical resources. Systemic resilience involves a long-term overhaul of how socio-technical resources are structured and utilized [ 23 ]. Building upon Hollnagel [ 24 ], resilience can be conceptualized as involving iterative cycles of behaviors related to anticipation, monitoring, responding, and learning at the micro, meso, and macro levels (Anderson et al., 2020). Anticipation involves identification of critical developments and potential threats. Monitoring involves keeping tabs on internal and external developments. This allows responding, which involves acceptance of the new reality created by the crisis; and coordinated, collective sense-making, and fast-responses to develop and implement new solutions. Learning, i.e. adaptation, involves emerging from a crisis in a stronger form through capabilities related to reflection and learning and organizational change. Learning involves first incorporating the lessons learned into the existing knowledge base that leads to change through the inception of new norms, values, and practices, so-called second-order learning. The organization’s capability to effect change is thus a critical capability [ 25 ]. This combined view of organizational resilience is captured in the Integrated Resilience Attributes Framework (Anderson et al., 2020).

Study setting

The Swedish health care system is highly decentralized with twenty-one self-governing regions responsible for funding and provision of health services [ 26 ]. Region Stockholm is the largest of these, with three acute teaching hospitals, one integrated acute and community care hospital, one eye hospital, and one university hospital (Karolinska University Hospital) serving a population of ca. 2 million inhabitants. A purchaser-provider model allows for patient choice and for private and publicly owned actors to work within the publicly financed system [ 27 ]. The majority of primary care, advanced home healthcare, as well as several outpatient specialist clinics are integrated into one provider organization, i.e. Stockholm Health Care Services (SLSO) [ 28 ]. Municipalities are responsible for care of elderly and disabled [ 26 ]. As in many health systems, challenges have been identified in terms of crossing organizational boundaries [ 29 ], particularly between tertiary and primary, psychiatric, and municipal care.

The first case of SARS-CoV-2 was registered in Sweden on January 31, 2020. Stockholm was among the first regions to prepare for these patients and soon faced one of the largest and fastest growing patient populations in the country. On February 7, Region Stockholm formed an emergency management team (RSSL) following the NATO emergency model [ 30 ]. On March 20, the Region Stockholm government directed SLSO to coordinate all operations in both private and public primary and community care as well as regional municipalities [ 30 ]. On March 27, RSSL established a regional Command Center to centralize and strengthen the supply of PPEs to health care staff [ 31 ]. The Command Center was coordinated by Karolinska University Hospital.

Participants

Through purposive sampling, we sought to interview experienced individuals in senior positions within regional health care-oriented organizations who had played pivotal leadership roles in addressing the challenges the pandemic created (Table 1 ). These individuals had gained visibility either through the media or through internal communication channels. We also employed a snowball technique where participants were asked to recommend others to interview. Despite the pressure of an ongoing pandemic, we interviewed twelve participants (seven women and five men). All but two had backgrounds in medicine (anesthesiology, surgery, and internal medicine) or nursing. Most had management roles, and all worked directly with or supervised efforts to address the pandemic in intensive care units, emergency departments, wards, HR, or hospital management at six different hospital sites. Others supported these efforts through education, the regional crisis planning and response organization, or the medical technology industry.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted between 28th of August 2020 and 21 of January 2021 using a semi-structured interview guide that allowed for follow-up questions (Additional File 1 ). The questions were arranged around five areas of inquiry: challenges, who was involved, responses, contextual factors, and lessons learned. The interview guide was pilot tested twice. Since no substantial changes were made, these interviews were included in the study. Interviews were mostly conducted online due to the pandemic; some at the place of employment. Most were approximately one hour in length, three were 45 min, and one 1h33 minutes long. They were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim .

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were read repeatedly to develop familiarity. Traditional (inductive) content analysis was performed using NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; QSR International (2018) [ 32 ]. LT identified meaning units relevant to the research question and using their manifest meaning, summarized them as codes. To strengthen trustworthiness, all codes were reviewed by all authors, who then jointly sorted them into themes, categories, and sub-categories using the Miro online virtual whiteboard ( www.miro.com ). In a second analysis phase, the inductively derived categories and subcategories were directed to the Integrated Resilience Attributes framework and labelled as facilitating (+) or hindering (-) factors [ 20 ].

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was sought and received prior to the interview. Data was handled confidentially, and all efforts were made to preserve anonymity. Participants were made aware that they could withdraw participation at any time. The Stockholm Regional Research Ethics Vetting Board formally stated that this research does not need an ethical permit.

An overview of the categories and sub-categories identified in the five areas of inquiry are presented in Additional File 2 and described in detail below.

Poor preparation led to acute shortages

Challenges were associated with pandemic preparedness, acute shortages, barriers to response development, and the emerging consequences of being ill-prepared.

Pandemic preparedness

Hospitals were described as unprepared for the pandemic, despite readily available knowledge about the pandemic and some staff with considerable international disaster relief experience.

The most distressing thing was that we knew this was coming. It didn’t come from nowhere. It was a catastrophic situation early in Italy. There were reports to colleagues warning us to prepare, “You have no idea what awaits.” We could have been more prepared. (P08)

Deficiencies in existing IT-systems led to the abandonment of digital innovations. Crisis leadership was faulted for unclear information, directives, and routines, e.g. conflicting infection control routines and large discrepancies between Swedish and WHO guidelines. Hospitals were better prepared than primary and elderly care and more able to repurpose wards and operating theaters to increase bed capacity.

Acute shortages

Participants described acute shortages in personal protective and medical equipment, staff, and care capacity. Material shortages were linked to dismantled stockpiles, the “just-in-time” principle. When established approval routines were not followed, there was uncertainty about if externally donated PPEs, medical equipment, and other consumables could be used. Staff shortages were partly attributed to employees who struggled with the increased tempo. Care capacity suffered due to a lack of dedicated wards and beds.

Barriers to response development

Anticipation difficulties.

Anticipating the size of the pandemic was challenging as prognoses were often incorrect. ED and ICU capacity was inadequate, and difficult to rapidly expand, which created challenges in patient flow logistics, patient hand-offs, and increased risks as patient transports became necessary when capacity was exceeded. Staff uncertainty and unfamiliarity with a new disease, its symptoms, and diagnostic testing made it difficult to adapt treatment and care strategies to patient needs. Resource scarcity limited testing to those with clear symptomatology.

- Crisis leadership

Crisis leadership was faulted for conflicting and rapidly changing directives from regional managers that often did not match the reality on the floor. Guideline discrepancies created communication challenges for managers as they struggled to inform staff. It also generated values conflicts, described as a tension between instructions and the professional ethos. Participants described the emotional difficulties of enforcing visitation restrictions on family members of dying patients.

When the instructions you receive do not match your values, you must eventually let go of the instructions. (P03)

Task shifting and facility repurposing

Task shifting and facility repurposing created new challenges. Participants’ clinical tasks increased, facility management demanded attention, there were concerns about losing well-functioning routines and units, and difficulties to distribute the large influx of external staff where they were needed most. Repurposed staff could therefore find themselves in a disorganized environment unable to train or support them adequately. Lack of knowledge about organizational structure and function under normal conditions slowed the transition from normal to crisis organization.

Emerging consequences

Participants described how poor planning led to local stockpiling, displacement of other care needs, and staff brittleness. Hospitals feared an impending lack of resources, so staff hoarded equipment locally and did not send material to central stockpiles for redistribution to where it was needed most. Other care needs, e.g. non-acute surgery and check-ups were postponed, and participants expressed concern over a mounting “care debt” as patients seeking care for non-covid related conditions diminished. The pandemic strained the endurance and perseverance of staff that worked in a high state of readiness for months.

Our staff has not volunteered for this. It is so stressful, that we rationalize it like this: It is ok to cry on your way home from work– that is a natural reaction to an unnatural situation. However, it is not ok that staff cry when they come into work. (P03)

New collaborations and support networks

While individuals’ frontline efforts in the microsystem around patients were in focus, participants also described collaboration at the meso (e.g. within and between hospitals) and macro levels (e.g. regional and national government agencies and international networks) that influenced the microsystem response.

Learning collaborations

Hospitals contacted each other through their clinical training centers and linked with universities and colleges to share experiences, curricular design, so medical and naprapathy students could ward patients.

Support for equipment, planning, and staffing

External actors repurposed and redirected staff, resources, and material to hospitals. Hospitals had daily contact with Swedish government, military, and ministries, the Swedish Association for Local Authorities and Regions, the National Board of Health and Welfare, and the Medical Products Agency to address the “enormous shortages” and resupply logistics. The Swedish work environment authority and the Ministry of development were vital in sourcing PPEs. Regionally, the Local Health Care Crisis Command (Lokal Särskild Sjukvårds Ledning, LSSL) assisted with ICU resource management, contingency planning, and taking competency inventories. Contacts were established with colleagues in other countries, such as Italy, China, and Taiwan to learn from their experiences.

Resource reprioritization, repurposing, and redirecting

Responses to the challenges posed by the pandemic were associated with resource management, process management, and communications and relational capacity.

Resource management

Resource management included the management of system inputs through governance methods, decision-making, and competency exchange and training. Participants described resource management responses (e.g. PPEs, staffing, and competencies) at the macro, meso, and individual levels. On the national level, government ministries repaired logistics chains based on inventory information from hospitals. The media was described as an important ally, as it often brought more attention from decisionmakers than traditional communication channels.

Regionally, a temporary Stockholm Command Center was established working out of a hospital CEO’s office, collected logistics and medical competencies, identified needs, and together with companies such as Scania (truck manufacturer), SAS (airline), Coor (facility management), H&M (clothing retail company), Camfil (advance filter producer), and IKEA (furniture company) sourced PPE. Companies retooled to manufacture products needed by hospitals. Resource management attained greater clinical relevance when Health Care Services Stockholm County (SLSO) was given crisis management responsibility for the entire healthcare system.

At the organizational level, hospitals adapted to a high state of readiness with the ambition to always be one step ahead.

We have worked based on a data model of what we thought would happen… You cannot manage today based on how it looks today. You must manage based on how it will look in two weeks if you want to have a hope about being able to do something about it… you must always be one step ahead. (P11)

Hospitals increased ED staffing to handle the massive patient flows, extended shifts, and set new routines. Competency exchange and training occurred both internally within hospitals, and externally within the region and internationally. Doctors and nurses from other departments were given rapid ICU training and medical, nursing, and naprapathy students were trained and employed. International colleagues were invited to share their knowledge and experiences. Certain equipment was prioritized, particularly PPE and medicines, and stockpiles were created. Digital matrices were developed to connect managers with the resources they needed.

At the individual level, staff at some hospitals were scheduled for 12-hour shifts to meet patient demand and urged to plan patient time carefully so they could use scarce PPE for longer, but fewer, periods.

Process management

New PMs and routines, restructuring of flows and physical layout, restructuring of operations to increase capacity, down-prioritization of non-essential education, managing psychological factors, redirecting ambulances, support from external actors, and fast iterations.

The pandemic forced hospitals to reprioritize, repurpose, redirect, establish new routines, and innovate. ICU capacity was prioritized and rapidly increased within days, with space repurposed from other units. Non-essential education such as clinical skills training for medical students was down prioritized in favor of training staff for ICU service. Ambulance communication lines were improved to alert about patient arrivals or when patients were redirected. ED patient flows were restructured to repurpose space and staff for Covid-care. New routines were established for dealing with family and informal caregivers; digital tablets enabled patients to communicate with family and digital patient consultations increased dramatically. Participants described a constant pressure to move fast. Some ideas with potential were lost due to the lack of time to develop a wider understanding, acceptance, or support. Nevertheless, despite the pressure, there was a common understanding within organizations to approach problem-solving and innovation scientifically, i.e. not just haphazardly throw together a solution, but to proceed in a systematic manner grounded in scientific knowledge, evidence, and proven experience.

Communication and relational capacity

Participants described collaborations with other providers, working within a medical framework, establishing routines for dealing with family and informal caregivers, quicker communication lines, and more efficient digital meetings.

Close collaboration between units resulted in a better understanding of each other’s competencies and needs. Hospitals and the regional administration mitigated staff burnout by putting hearts on a wall to celebrate each discharged patient or arranging for ministers and psychologists to walk the floors. A knowledge acquisition group met regularly to coalesce lessons learned into practical guidelines that could be disseminated. Participants stressed that CEO’s medical expertise enabled them to understand and support managers.

Efforts to improve communication included an information hotline for citizens. Reporting routines upwards from the floor were improved, but some initiatives, such as a staff suggestions email, failed due to lack of awareness. The high threshold for digital meetings prior to the pandemic was overcome as everyone became better at using the technology.

Organizational and individual factors influenced responses

Agile responses to the challenges were influenced by organizational facilitators, organizational barriers, and individuals’ desire to do good.

Organizational facilitators

Latent organizational factors that enabled a quick response included existing collaborations between units and hospitals, established catastrophe plans facilitated adaption of new guidelines, and existing digital health solutions were repurposed. Clinical educators quickly grasped the need for competency development of incoming, repurposed staff. Staff shared a common purpose and goal to solve the crisis, maintained a positive attitude, a desire to do good, and a willingness to make personal sacrifices.

Organizational barriers

The pandemic revealed serious difficulties in achieving collaboration across existing organizational boundaries, particularly between hospitals and primary care. Participants explained this was due to historical divides with poor communication and coordination, which made assigning responsibility for individual patients or patient segments such as non-hospitalized Covid-19 patients difficult. Inadequately formulated contracts with suppliers and the “just-in-time” principle were faulted by participants for frail supply-chains.

Individuals’ desire to do good

Participants described a common desire to make the most of one’s knowledge by sharing it with others, to learn and improve care delivery, and to do good. They saw widespread positive thinking and fighting spirit, and an optimism that individual action would lead to positive outcomes. They also described the eventual toll of sacrifices made, long shifts, delayed vacations, and skipped breaks.

Collaboration, adaptation, and leadership were key

Lessons were learned related to collaboration, adaptive responses, and crisis leadership.

Systems-based collaboration

The pandemic highlighted the importance of effective collaboration with key partners and the wider system. Centrally placed decision-makers lacked the requisite knowledge and holistic perspective to enable this. Instead, hospitals developed their own strategies, and the university hospital took the lead in developing patient treatment strategies and acted as a safety net when other hospitals’ ICUs were filled. Hospitals with good results shared their strategies with the region and eventually the rest of Sweden as cases increased in other parts of the country.

Adapt responses

Hospitals chose to work systematically with a two-week time frame that allowed them to be agile and continually adapt their responses. Participants explained how they learned to mobilize quickly, without analyzing or dwelling on single activities for too long. In preparation for a future pandemic, participants emphasized the need to link organizational change with the quick response, shorten decision-making pathways, align crisis leadership, and establish plans for protracted health crises of magnitude.

Participants argued for a professions-led and distributed agile response to decision-making.