- Consumer Goods and Services /

- Travel and Tourism /

- Hotels and Travel Accomodation

The impact of COVID-19 on Airbnb: Case Study

- Region: Global

- ID: 5022059

- Description

Table of Contents

- Companies Mentioned

Related Topics

Related reports.

- Purchase Options

- Ask a Question

- Recently Viewed Products

- Airbnb is unique in that the travelers are not their only customers. Hosts use the Airbnb platform to advertise properties, and benefit from the awareness Airbnb has in the market. Different to Online Travel Agencies (OTA’s) such as Booking.com or TripAdvisor, the hosts are in most cases individual people who are renting out their own homes, and therefore do not have the bargaining power, cash reserves or brand image that hotels would do on other OTA’s.

- Hosts are welcoming a dramatic drop in guest numbers, and in turn not receiving any income from their properties. For hosts who rely upon Airbnb for their income, it poses a worry on being able to make mortgage payments, pay bills and survive themselves during the pandemic. Airbnb’s current free cancellation period up until May 31st for bookings made on or before March 14th, mirrors that offered by hotels, Airbnb’s indirect competitor. However, the hosts have to offer the refunds on this personally, and unlike hotels do not have the cash reserves and ability to do so.

- The scale and extent of Airbnb’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic should be carefully thought about, as each move they make will make a large difference to how Airbnb will operate after the height of the pandemic is over. Detrimental stories that have emerged in the press such as hosts offering ‘COVID-19 Retreats’ in the UK despite national lockdown rules and the backlash of troubles in obtaining refunds for stays and experiences, could leave a bad image of the brand in the future.

- This report provides insight into how COVID-19 is impacting Airbnb and looks at the affects the pandemic is having on Airbnb’s relationship with both guests and hosts.

- It also analyzes the company’s response to the current crisis.

- Gain an overview of the current global COVID-19 situation

- Understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the lodging industry

- Assess the impact on Airbnb

- Understand what the future may hold for Airbnb

- Airbnb Overview

- Impacts on Airbnb

- Airbnb’s Response

- SWOT Analysis

- Airbnb post-COVID-19

Companies Mentioned (Partial List)

A selection of companies mentioned in this report includes, but is not limited to:

- Hotels And Travel Accomodation

Sharing Accommodation Market By Type, Business to Business, By Application: Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2023-2032

- Report

- October 2023

Short-term Vacation Rental Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Booking Mode (Online/Platform-based, Offline), By Accommodation Type (Home, Resort/Condominium), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2023 - 2030

- August 2023

Global Vacation Rental Market 2024-2028

- December 2023

Global Short Term Vacation Rental Market 2024-2028

- January 2024

Vacation Rental Global Market Insights 2023, Analysis and Forecast to 2028, by Market Participants, Regions, Technology, Application, Product Type

ASK A QUESTION

We request your telephone number so we can contact you in the event we have difficulty reaching you via email. We aim to respond to all questions on the same business day.

Request a Quote

YOUR ADDRESS

YOUR DETAILS

PRODUCT FORMAT

DOWNLOAD SAMPLE

Please fill in the information below to download the requested sample.

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My Portfolio

- Stock Market

- Biden Economy

- Stocks: Most Actives

- Stocks: Gainers

- Stocks: Losers

- Trending Tickers

- World Indices

- US Treasury Bonds

- Top Mutual Funds

- Highest Open Interest

- Highest Implied Volatility

- Stock Comparison

- Advanced Charts

- Currency Converter

- Basic Materials

- Communication Services

- Consumer Cyclical

- Consumer Defensive

- Financial Services

- Industrials

- Real Estate

- Mutual Funds

- Credit Cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash-back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Personal Loans

- Student Loans

- Car Insurance

- Options 101

- Good Buy or Goodbye

- Options Pit

- Yahoo Finance Invest

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

Yahoo Finance

Airbnb - the impact of covid-19 and how the company is responding to the crisis.

Dublin, June 18, 2020 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The "The impact of COVID-19 on Airbnb: Case Study" report has been added to ResearchAndMarkets.com's offering.

Travel restrictions in place, cancellations increased and therefore occupancy down. Hosts are suffering from minimal income from their properties and Airbnb is suffering from a lack of commission from these bookings. This case study looks at how the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting Airbnb and assesses the company's response. Key Highlights

Airbnb is unique in that the travelers are not their only customers. Hosts use the Airbnb platform to advertise properties, and benefit from the awareness Airbnb has in the market. Different to Online Travel Agencies (OTA's) such as Booking.com or TripAdvisor, the hosts are in most cases individual people who are renting out their own homes, and therefore do not have the bargaining power, cash reserves or brand image that hotels would do on other OTA's.

Hosts are welcoming a dramatic drop in guest numbers, and in turn not receiving any income from their properties. For hosts who rely upon Airbnb for their income, it poses a worry on being able to make mortgage payments, pay bills and survive themselves during the pandemic. Airbnb's current free cancellation period up until May 31st for bookings made on or before March 14th, mirrors that offered by hotels, Airbnb's indirect competitor. However, the hosts have to offer the refunds on this personally, and unlike hotels do not have the cash reserves and ability to do so.

The scale and extent of Airbnb's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic should be carefully thought about, as each move they make will make a large difference to how Airbnb will operate after the height of the pandemic is over. Detrimental stories that have emerged in the press such as hosts offering COVID-19 Retreats' in the UK despite national lockdown rules and the backlash of troubles in obtaining refunds for stays and experiences, could leave a bad image of the brand in the future.

Report Scope

This report provides insight into how COVID-19 is impacting Airbnb and looks at the affects the pandemic is having on Airbnb's relationship with both guests and hosts.

It also analyzes the company's response to the current crisis.

Key report benefits:

Gain an overview of the current global COVID-19 situation

Understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the lodging industry

Assess the impact on Airbnb

Understand what the future may hold for Airbnb

Key Topics Covered: Current COVID-19 Overview

Airbnb Overview

Impacts on Airbnb

Airbnb's Response

SWOT Analysis

Airbnb post-COVID-19

Companies Mentioned

For more information about this report visit https://www.researchandmarkets.com/r/iug9l6

About ResearchAndMarkets.com ResearchAndMarkets.com is the world's leading source for international market research reports and market data. We provide you with the latest data on international and regional markets, key industries, the top companies, new products and the latest trends.

Research and Markets also offers Custom Research services providing focused, comprehensive and tailored research.

CONTACT: ResearchAndMarkets.com Laura Wood, Senior Press Manager [email protected] For E.S.T Office Hours Call 1-917-300-0470 For U.S./CAN Toll Free Call 1-800-526-8630 For GMT Office Hours Call +353-1-416-8900

Travel restrictions in place, cancellations increased and therefore occupancy down. Hosts are suffering from minimal income from their properties and Airbnb is suffering from a lack of commission from these bookings. This case study looks at how the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting Airbnb and assesses the company's response.

Key Highlights

- Airbnb is unique in that the travelers are not their only customers. Hosts use the Airbnb platform to advertise properties, and benefit from the awareness Airbnb has in the market. Different to Online Travel Agencies (OTA's) such as Booking.com or TripAdvisor, the hosts are in most cases individual people who are renting out their own homes, and therefore do not have the bargaining power, cash reserves or brand image that hotels would do on other OTA's.

- Hosts are welcoming a dramatic drop in guest numbers, and in turn not receiving any income from their properties. For hosts who rely upon Airbnb for their income, it poses a worry on being able to make mortgage payments, pay bills and survive themselves during the pandemic. Airbnb's current free cancellation period up until May 31st for bookings made on or before March 14th, mirrors that offered by hotels, Airbnb's indirect competitor. However, the hosts have to offer the refunds on this personally, and unlike hotels do not have the cash reserves and ability to do so.

- The scale and extent of Airbnb's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic should be carefully thought about, as each move they make will make a large difference to how Airbnb will operate after the height of the pandemic is over. Detrimental stories that have emerged in the press such as hosts offering COVID-19 Retreats' in the UK despite national lockdown rules and the backlash of troubles in obtaining refunds for stays and experiences, could leave a bad image of the brand in the future.

- This report provides insight into how COVID-19 is impacting Airbnb and looks at the affects the pandemic is having on Airbnb's relationship with both guests and hosts.

- It also analyzes the company's response to the current crisis.

Key report benefits:

- Gain an overview of the current global COVID-19 situation

- Understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the lodging industry

- Assess the impact on Airbnb

- Understand what the future may hold for Airbnb

Key Topics Covered:

Current COVID-19 Overview

- Airbnb Overview

- Impacts on Airbnb

- Airbnb's Response

- SWOT Analysis

- Airbnb post-COVID-19

Companies Mentioned

For more information about this report visit https://www.researchandmarkets.com/r/h93voz

About ResearchAndMarkets.com

ResearchAndMarkets.com is the world's leading source for international market research reports and market data. We provide you with the latest data on international and regional markets, key industries, the top companies, new products and the latest trends.

ResearchAndMarkets.com Laura Wood, Senior Press Manager [email protected] For E.S.T Office Hours Call 1-917-300-0470 For U.S./CAN Toll Free Call 1-800-526-8630 For GMT Office Hours Call +353-1-416-8900

- Follow UNSW on LinkedIn

- Follow UNSW on Instagram

- Follow UNSW on Facebook

- Follow UNSW on WeChat

- Follow UNSW on TikTok

Disrupting the disruption: COVID-19 reverses the Airbnb effect

Sydney rents fell during the pandemic as investors swapped short-term holiday lettings for traditional rentals, UNSW research shows.

Media contact

Ben Knight UNSW Media & Content (02) 9065 4915 [email protected]

The meteoric rise of Airbnb across cities has disrupted rental housing markets worldwide as property owners took advantage of a new avenue for investment returns. But the tables might have turned.

A recent UNSW City Futures Research Centre report assessing how Airbnb activity and the rental market has changed during the COVID-19 shows that it’s now renters who could be benefiting from a decline in Airbnb activity due to the pandemic.

The study, Airbnb during COVID-19 and what this tells us about Airbnb’s Impact on Rental Prices , by professor of urban science Christopher Pettit and postgraduate researcher William Thackway , found that weekly rents declined in proportion to reduced Airbnb activity, as Airbnb landlords converted their properties to long-term rentals – at cut-price rates.

Airbnb during COVID-19

The researchers used a comprehensive record of Airbnb listings and rental sales data to find the supply of long-term rentals increased during the pandemic in historical Airbnb hotspots such as Bondi, Manly and the CBD. Meanwhile, rental prices fell proportionately with Airbnb listings, up to 7.1% in the most active Airbnb neighbourhoods.

“Since the pandemic, with border closures and city lockdowns, particularly between March and May where Airbnb wasn’t in operation, there’s been subdued [Airbnb] activity, ” Mr Thackway says. “ We saw the reverse of what had been happening for the last 10 years, which is that many Airbnb’s were converted to long-term rentals, presumably by landlords who are now seeking a more stable income source, particularly given that Airbnb wasn’t even operating for a few months.”

Airbnb traditionally receives a far higher daily rate than long-term rentals due to short-term tourism demand, which has previously motivated many landlords to invest in short-term rentals, Mr Thackway says.

“While there are other actors at play, there were ultimately fewer long-term rentals in the market because of Airbnb. The reduced supply of long-term rentals, without any difference in the demand, meant that overall rental prices have, until this point, been rising,” he says.

“Now, when you get Airbnb’s converted back to long term rentals, there’s a new influx of supply to the rental market, and there has been a corresponding reduction in rental prices, and that’s been observed for almost all active Airbnb areas.”

According to the research, Sydney had over 23,000 active Airbnb listings at its height. The Airbnb density measure used in the study also found that the proportion of Airbnb’s was as high as 25% in some areas such as Bondi.

“It’s not necessarily saying that those are active all the time, but it’s saying that 25% of the houses in the area listed are being booked out at some point during the year,” Mr Thackway says.

Thinking long-term

While Airbnb’s effect on the rental market may have been reversed in the city, the researchers suggest this hasn’t been the case for coastal and regional areas.

“We suspect that regional areas are experiencing increases in tourist activity, mostly associated with domestic tourism, particularly urbanites wanting to get out of the city and holiday regionally,” Mr Thackway says.

“So, we would likely see those regional tourism hotspots having experienced an overall increase in Airbnb activity, and possibly rental prices, which would contrast with urban areas where Airbnb activity and tourist activity generally has fallen quite dramatically.”

While the temporary reversal of Airbnb activity on the housing market is a timely win for renters amid the housing affordability crisis, the researchers say it’s likely to revert to business as usual once international tourism returns.

“In terms of house prices and rents, Sydney is among the most unaffordable cities globally,” Mr Thackway says. “Reduced Airbnb and subsequently, reduced rental prices can only be a good thing for renters, and ultimately, for Sydney, because it is such an exclusive market and keeps tending towards that way.”

In NSW, there’s currently a 180-day cap on the number of days an Airbnb can be listed, while local governments and council can also exert additional control within the cap. But further regulations of short-term letting could be timely, Mr Thackway says.

“If the government wants to restrict its impact on renters, then tougher regulation, specifically on commercial Airbnb’s that permanently take away supply, would be necessary.”

More From Forbes

How airbnb beat the covid-19 virus.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

POLAND - 2020/05/04: In this photo illustration an Airbnb logo seen displayed on a smartphone. ... [+] (Photo Illustration by Filip Radwanski/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Going into 2020, Airbnb was growing at a rapid pace and aggressively expanding into new categories. So what could possibly go wrong?

Well, within a couple months, the Covid-19 pandemic would shutdown the travel industry. And suddenly Airbnb was facing an existential crisis.

By April, the gross bookings for nights and experiences plunged by 72% on a year-over-year basis. In fact, from March to April, there were more cancellations than bookings!

While the situation was certainly dire, the management team wasted little time in pursuing a major restructuring. The result was that—over time—the business started to improve. By June, there was actually a 1% increase in gross bookings.

Now this is not to say that the business is no longer under pressure. The fact remains that revenues are still well off the levels of 2019. But then again, Airbnb has weathered the pandemic relatively well compared to other major travel operators, whether hotel chains or online marketplaces.

So why is this so? What did Airbnb do? Let’s take a look:

Cost Cutting : The mantra of Silicon Valley is high growth. But this philosophy makes no sense when the market is experiencing huge problems.

In the situation of Airbnb, management initiated a layoff of 25% of the workforce. There was also a steep reduction in discretionary and capital expenditures, a slashing of executive salaries and a suspension of all facilities build-outs.

Best Tax Software Of 2022

Best tax software for the self-employed of 2022, income tax calculator: estimate your taxes.

Airbnb CEO and founder, Brian Chesky, set forth this plan in a letter that was sent to employees and published on the company blog . He did not mince words, saying “I have to share some very sad news.” He would go on to be thoughtful, transparent and clear about the “hard truths.”

Chesky also set forth a variety of principles about how the restructuring would be handled:

- Map all reductions to our future business strategy and the capabilities we will need.

- Do as much as we can for those who are impacted.

- Be unwavering in our commitment to diversity.

- Optimize for 1:1 communication for those impacted.

- Wait to communicate any decisions until all details are landed — transparency of only partial information can make matters worse.

Focus On The Core Business : In the shareholder letter in the S-1, the founders noted: “When the pandemic hit, we knew we couldn’t pursue everything that we used to. We chose to focus on what is most unique about Airbnb—our core business of hosting. We got back to our roots and back to what is truly special about Airbnb—the everyday people who host their homes and offer experiences. We scaled back investments that did not directly support the core of our host community.”

This move proved critical. As the pandemic deepened, people were looking more at local stays—and this played to the advantage of Airbnb. It was one of the biggest factors in the turnaround of the business.

Creatively-led : When there are severe constraints and limitations, this can lead to even more inspiration. This was certainly the case with the Airbnb team. For example, when the in-person Experiences segment was suspended, this led to the creation of Online Experiences. It turned out to be an extremely popular offering.

Trust : This is the heart of any successful business. But during times of crisis, it can be tempting to make short-term financial decisions that ultimately undermine trust.

An example of this quandary for Airbnb was about the spike in cancellations. Keep in mind that many were non-refundable. But to bolster the marketplace, Airbnb used more than $1 billion of its funding to provide refunds. There was also a commitment of up to $250 million for those hosts that were impacted by the cancellations.

Long-Term Optimism : During the early days of the pandemic, it would have been easy to lose confidence in the vision of Airbnb. But the founders did not let this happen. They knew that the long-term prospects looked bright.

According to the founders: “A crisis brings you clarity about what is truly important. You become thankful for not only what you have in your life, but for who you have in your life. We are thankful for everyone who stuck by us during our darkest hours.”

Tom ( @ttaulli ) is an advisor/board member to startups and the author of Artificial Intelligence Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction and The Robotic Process Automation Handbook: A Guide to Implementing RPA Systems . He also has developed various online courses, such as for the COBOL and Python programming languages.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Disrupting the disruptors: how Covid-19 will shake up Airbnb

Airbnb created an industry and changed the face of many neighbourhoods. Now it’s facing the challenge of the coronavirus

A irbnb was built on the premise of bringing the world closer together. Tourists could travel like locals, while locals could cash in on their desirable neighbourhood properties by letting those visitors in. Last year the company was estimated to be worth more than US$30bn . It is scheduled to go public in 2020. Then came the Covid-19 pandemic.

Travel is suspended. Australians are almost entirely confined to their homes. Now the once heralded disruptor is seeing a collapse in bookings . The hosts who have become reliant on income-generating properties to pay their bills are being bled dry by a lack of business, and already-suspicious neighbours are up in arms over the potential that short-term renters may spread the virus.

In the decade before the pandemic, Airbnb became “this very attractive thing”, says Chris Martin, a senior research fellow at the University of New South Wales’s City Futures Research Centre. The platform, and others like it, fundamentally changed not only the travel industry but housing and rental markets. A home is no longer just a home, Martin says. “[The company] tapped into the idea that a person’s house can also be viewed as an asset that has capacity for generating income.”

This shift “massively upped the scale of [short-term rental]”, which in turn put pressure on residential rental markets. The changes have resulted in lawsuits in the US and a petition by 10 cities to the European parliament in 2019. There are more than seven million Airbnb listings spread across 100,000 cities – with an estimated 346,581 listings between July 2016 and February 2019 in Australia alone .

‘The whole industry has fallen through’

Stephen Colman, who was an Airbnb host and ran an Airbnb management business up until last year, says “the whole industry has fallen through”. Many hosts are either pulling out of Airbnb to find cheaper long-term tenants or have been offering “14-day isolation suites”.

The former, Colman says, will come with a long wait and big rent cuts, as everyone else rushes to do the same. The latter is even more fraught. This week the Greens state MP for Ballina, Tamara Smith, called on online holiday booking websites such as Airbnb and Stayz in the Byron Bay region to stop marketing regional properties as ideal places for self-isolation, saying it wasn’t fair on regional hospitals and communities.

“There are real concerns around cleaning stuff,” Colman says, “How many hours between checkout and check-in … [Hosts] have seen a fightback from body corporates who are just outright cancelling the key fobs for anyone who they believe is doing Airbnb. They’ve just gone ‘we’re going to take this hard line to protect the safety of our long-term tenants’.”

Jane Hearn, deputy chair of the Owners Corporation Network, has argued that opening Airbnb properties for quarantine “increases the viral load on apartment owners and tenants”. Resident advocacy groups such as We Live Here and Neighbours Not Strangers were already lobbying against Airbnb on behalf of local communities who were sick of rowdy travellers in their apartment complexes. In a letter to New South Wales premier Gladys Berejiklian on 1 April, Neighbours Not Strangers called for an immediate ban on all short-term rentals, due to the risks from Covid-19.

Airbnb does not support reservation requests from users who are showing symptoms, or those who are awaiting test results. Last week the company instituted a ban on any listings that “reference Covid-19, coronavirus or quarantine” and listings which “incentivise bookings through Covid-19-related discounts, stocks of limited resources, or the highlighting of quarantine-friendly listing attributes”. The company’s updated instructions for cleaning and hygiene recommend hosts stock their properties with “a few extras” like “antibacterial hand sanitizer, disposable gloves and wipes, hand soap, paper towels, tissues” … and toilet paper.

The government has now mandated that all international arrivals must complete their quarantine at designated pre-booked hotels . But, before that, some Australians were happy turning to Airbnb. Comedian Alice Fraser is currently in a “good value” Bondi Airbnb after returning from London. She saw Airbnb as “the responsible option”: “[It’s there] for people who don’t have favours to call in, or family who happen to have a massive home that can be segmented into parts.”

‘We lost everything’

Lisa Porgazian and her husband have listed their three Gold Coast apartments on Airbnb for the past four years. Now the properties are empty, and the mortgage payments will come out of the couple’s superannuation. “We were relying on this for our income, as well as our retirement plan,” she says, distraught. “Now that’s completely died in the arse.”

Porgazian, a 46-year-old former IT contractor, has been managing her property portfolio full-time. She’s unable to work in many other jobs due to rheumatoid arthritis. “I’m earning zero. My husband’s earning zero. And we’ve still got these mortgages to pay.”

With the spread of Covid-19, a downturn in business was inevitable. But many Airbnb hosts were shocked at how quickly it came. The company introduced a policy earlier this month allowing all guests who booked prior to 14 March (and were checking in no later than 31 May) to cancel existing bookings for free. Porgazian says this left hosts holding the cheque.

“We lost everything straight away … Everything is cancelled, basically until Christmas.”

Susan Wheeldon, Airbnb’s country manager for Australia and New Zealand, said offering these free cancellations “wasn’t an easy decision”, but it was one made with “public health considerations” front of mind. “The primary consideration for us was protecting the wellbeing of the community.”

‘There’s not enough tenants to fill these places’

Travis Lipshus, a real estate agent in Byron Bay, thinks this chaos for Airbnb hosts could result in cheaper long-term rent for locals. He’s getting flooded with properties from Airbnb hosts who now need permanent tenants. But with so many of the town’s hospitality staff and backpackers currently out of work “there’s not enough tenants to fill these places”.

If rents did lower, it would be a massive relief. It’s notoriously difficult for locals to find affordable rentals in Byron Bay, as 17.6% of properties are listed as holiday accommodation. “Airbnb should be banned up here,” Lipshus says. “ The cost of living is insane. I’ve lived in all sorts of places here, and it’s not uncommon to pay at least 50% of your wage in rent.”

Martin describes the current regulation around Airbnb as “really quite liberal”. He says at present, it “didn’t seem to fit well with highly local impacts. Local councils [should] have a strategy and a plan around short-term letting – especially around limits.”

For now, he is not so certain we’ll see a drop in rents. “Landlords may still withhold properties and leave them vacant instead,” he says. “For whatever reason, that seems to be a surprisingly common scenario in the high-pressure [locations].”

Wheeldon says that Airbnb “has not seen a material drop in the overall number of listings on our platform. While the Covid-19 crisis has significantly disrupted the tourism industry and wider economy, we know that travel is resilient in the long term and will ultimately recover.”

But will the hosts recover?

“We know our hosts are doing it tough,” Wheeldon says. The peak body representing Airbnb and other short term rental companies has sought urgent support from the federal government for hosts in the form of mortgage payment deferrals, among other measures. For many, that may not be enough.

“A lot of people have over-leveraged themselves with these properties,” Lipshus says. “The upper-middle class are probably going to be fine. But the middle class – the ones taking risks, trying to get up that class ladder – they’re going to be pretty fucked.”

Lisa Porgazian knows what people are saying. “The criticism that we’re getting is ‘well you shouldn’t have a business if you can’t pay for it’, but who ever predicted something like this?”

- Coronavirus

- Australia travel blog

- Australia holidays

- New South Wales holidays

- Australian lifestyle

Most viewed

Advertisement

Supported by

The Future of Airbnb

Home-sharing’s challenges aren’t only about social distancing and hygiene. Overtourism, racial bias, fee transparency and controlling the party crowd are also in the mix.

- Share full article

By Elaine Glusac

In the travel wreckage caused by the pandemic, home-sharing has emerged as battered, but with a steady pulse, as rental houses became social-distancing refuges for the travel-starved.

Home rentals have outperformed hotels in 27 global markets since the onset of Covid-19, according to a report by the hotel benchmarking firm STR and the short-term rental analysts AirDNA. As leisure travel ticked up this summer, average daily rates were higher for rentals in July 2020 versus July 2019 in the United States — from about $300 to $323 — thanks to the popularity of larger homes.

Still, global restrictions have squeezed every aspect of the travel industry, including vacation rentals. Across home-sharing platforms, according to STR and AirDNA, occupancy fell by almost half between mid-March and the end of June to between roughly 33 and 36 percent, depending on the size of the rental (hotels by comparison fell to an average of 17.5 percent occupancy).

The biggest player in the short-term rental market, with more than 7 million listings in over 220 countries, is Airbnb . Over the years, its rampant growth and lack of transparency have made it a target for everything from charges of fueling overtourism and turning formerly residential neighborhoods into tourist zones to enabling raucous parties despite complaints and virus-related restrictions on gatherings.

After laying off a quarter of its work force in the spring, Airbnb jettisoned some new ventures, including forays into transportation and entertainment, and hunkered down to focus on its core strength, lodging, even as its valuation fell from a high of $31 billion to, recently, $18 billion, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Now, as Airbnb prepares to go public , we talked to Airbnb’s co-founder and chief executive, Brian Chesky, along with other industry experts, about some of the company’s challenges and the ways it is changing travel.

“People want to travel, they just don’t want to get on airplanes,” Mr. Chesky said. “They don’t want to go for business. They don’t want to stay in the really big cities as prevalently as they used to. They don’t want to be in crowded hotel districts.” But, he said, “they do want to get out of the house. And so we think demand is going to be strong in the future. I’m very optimistic, actually, about the industry.”

Lifestyle vs. vacation

Airbnb has touted privacy and guests’ control over their environment — including having your own kitchen in lieu of patronizing restaurants — as safeguards during the pandemic. It instituted new cleaning guidelines and indicated in late August that more than 1 million listings had earned the “ Enhanced Clean ” certification, which involves training in new guidelines that detail how and what to wash and sanitize. The procedures recommend 45 minutes of cleaning per room. Some listings guarantee a 72-hour vacancy window before check in.

The company says its offerings are aligned with the way people are traveling now, in family and friend groups to less populated destinations. Over Labor Day weekend, 30 percent of its bookings — double the previous year — were in remote areas, though classic vacation spots like Hilton Head Island, S.C., and Palm Springs, Calif., were among the most popular. Urban bookings remain down.

“We’re seeing a little blurring between traveling and living,” Mr. Chesky said. “Before the pandemic, you lived somewhere 50, 51 weeks of the year, and if you were so fortunate, you’d go on your once-or-twice-a-year vacation. Now the pandemic is changing how people want to work, travel and live.” Remote school and work unbind families from their homes. “People are living differently and people want to live anywhere,” he added.

Whether travel truly turns into nomadism remains to be seen, though the average length of stay since May 1 increased 58 percent to more than four days, and fall bookings are stronger than usual, according to AirDNA.

Overtourism, rising rents and housing shortages

Cities around the world, from Barcelona to Vancouver, are looking to curb Airbnb and other short-term rental companies, which many blame for hollowing out neighborhoods as real estate managers took long-term leases and listed them as more lucrative short-term rentals.

“You can earn more renting out apartments and houses on Airbnb than renting to locals,” said David Wachsmuth, an associate professor in the School of Urban Planning at McGill University in Montreal. “What’s happened on their platform is that actual home-sharing is a fraction of the activity. It’s dominated by commercial interests.”

Research published in the Harvard Business Review found that as listings rise in a city, so do rents. Analyses by the Economic Policy Institute , a nonpartisan think tank, found the costs to local communities of having Airbnb listings, including rising housing prices and shrinking availability, likely outweigh the benefits.

“The problems of overtourism were in the making for a long time,” said Makarand Mody, an assistant professor of marketing in the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. “Airbnb came along and made it worse. It was seen as one evil that needs to be sorted out, but there are much deeper societal and economic issues. Airbnb is just the supply side. But demand has increased so much.”

By 2019, the rise of the middle class globally contributed to expanding tourism above the rate of worldwide economic growth for nine years in a row, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council. In Airbnb, many travelers found affordable accommodations that allowed them to stay in neighborhoods rather than business centers.

Now that the pandemic is the ultimate overtourism disrupter, Mr. Chesky believes travel has been redistributed in a lasting way to places beyond bucket-list capitals. “It’s kind of redeemed our vision,” he said. “What I would love is to be able to help spread out travel to as many communities as possible rather than over-concentrating them in any one place.”

“My speculation is that the world does not quickly snap back to the way it was,” he added. “I don’t think travel will ever, ever look like it did in January. The world can’t change so dramatically like it has and then one of the industries that’s been hit hardest just looks exactly like it did before.”

Communities aim to ensure that. Last summer, Oahu enacted a law to restrict rentals without permits on the Hawaiian island, enforced with fines. In Europe , cities like Lisbon and Dublin are buying back leases or forcing landlords into long-term rentals in an effort to ensure that when tourism rebounds it won’t overwhelm them again.

Enforcement remains thorny, and Airbnb has been accused of looking the other way when it comes to illegal listings. Last year, Los Angeles limited rentals to owner-occupied properties registered with the city, though many illegal units remain on the site, according to the Los Angeles Times .

In response, Airbnb just launched a new City Portal that it says will allow governments to more easily identify listings that don’t comply with local regulations, such as unregistered listings.

Before the launch, the company shared the new tool with San Francisco’s Office of Short-Term Rentals . “They’re pretty positive about it and hopeful this will definitely improve their ability to get bad actors off the platform,” said Jeffrey Cretan, a spokesman for the city’s mayor.

Perhaps because of these scofflaws, Airbnb says it has not lost significant listings. According to AllTheRooms Analytics, among popular cities in Europe, only Rome and Lisbon have shed listings, about 2,000 each. In Lisbon, the crackdown still leaves just above 14,500 listings, the same figure as in January 2019, but down from the peak in July 2019.

The effect of more regulations may show up in the future, posing a threat to a robust portfolio. “For a platform like Airbnb, they’re not just worried about the demand side, but the supply side,” Mr. Mody, of Boston University, said, noting the travel freeze may convince hosts to put their units in the long-term rental market, shrinking the platform, and worrying potential investors. “When you’re living on venture capital, profitability is not as important as growth,” Mr. Mody added. “Shareholders will be a lot less patient.”

The music stops at party houses

During the pandemic, Host Compliance , which tracks legal compliance among short-term rentals for 350 cities and counties in the United States, said noise complaints about so-called “party houses” tripled.

“A lot of people have been at home for a long time and they have to let some steam off and can’t jump on a plane to go to Europe or Cancún to party so they are renting out short-term rentals in driving distance from their homes,” said Ulrik Binzer, the founder and general manager of Host Compliance.

Often, these rentals are in residential neighborhoods, triggering noise complaints and health concerns about large gatherings.

In Miami Beach, short-term rentals were closed this summer, though those within condo and apartment buildings were allowed to reopen, with capacity limits, in August. That month, the city of Los Angeles cut the power on a house (not an Airbnb property) rented by prominent TikTok stars during a large party.

In August, Airbnb pulled the plug, too, announcing a global ban on party houses , defined as those that persistently generate complaints from neighbors. The company says 73 percent of listings already ban parties, though hosts often allow small gatherings like baby showers and birthday parties. Occupancy is now limited to 16 people.

Airbnb imposed a similar restriction in Canada earlier this year after a party in Toronto ended in three shooting deaths, according to BBC News .

“We want to do everything we can do to preserve the character of the communities and not allow these parties to get out of hand,” Mr. Chesky said.

It’s too soon, say observers, to know if the ban is working.

“The issue with Airbnb party houses is enforcement,” Mr. Binzer said. “It’s a little like having the fox watch the henhouse.”

The $52 rental with a $125 cleaning fee

On Sept. 14, a Twitter user wrote , “Found a cheap @Airbnb for 52 dollars. Cleaning fee for 1 night, 125. Nonsense.”

It’s a typical complaint about the platform, which lists attractive nightly rates, but buries the fees until users begin booking. Cleaning and service fees can be modest — zero to $25, say — or add $450 to a booking, reflecting a mix of mandatory and optional host-applied fees. Sometimes there are additional occupancy taxes. And in some countries, Airbnb applies a Value Added Tax on its service fees.

Under Airbnb’s pricing structure , hosts pay the company 3 percent of the booking subtotal, which includes the nightly rate plus any cleaning fee and fees for additional guests. Most guests are charged a service fee of less than 14.2 percent of the booking subtotal, which goes to Airbnb. (If hosts elect to cover the fee entirely, they normally pay Airbnb 14 to 16 percent of the subtotal.)

Because of their variability and lack of transparency, fees are the latest financial facet users have fixated on after the company created its extenuating circumstances policy during the pandemic. It said that travelers who had reservations made on or before March 14 could cancel and not be subject to cancellation fees, even if, in their rental agreement, they were in the penalty period. The policy has been extended several times, now to Oct. 31. (While most guests were happy with the resolution, many hosts were not and Airbnb later apologized to hosts for not consulting them).

Airbnb said it aims to introduce a redesign of price displays this year. “We’re trying to partner with hosts to create clear standards and change the search line, so if someone has higher cleaning fees, that affects their placement” in search results, Mr. Chesky said. “We’ve heard from travelers that they want a simpler way for us to show more of the price up front.”

Reckoning with racial bias

Four years before George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis, igniting this summer’s protests for social justice, the emergence of the hashtag # AirbnbWhileBlack called attention to a spate of racist incidents that users said happened at rental homes. Some Black renters were reported by neighbors as thieves. Others were subject to abuse by racist hosts rejecting their bookings. Complaints by Muslim, transgender and other groups followed.

Airbnb worked to purge discrimination from its platform by hiding guest’s profile pictures until a booking is confirmed; hiring anti-discrimination specialists to audit the platform; and creating a reporting channel to identify listings not complying with its nondiscrimination policy . The company said it has removed 1.3 million offenders.

This month, Airbnb plans to launch Project Lighthouse , a research initiative in the United States that aims to measure bias through perception based on names and photos, to determine where and when bias happens on the platform, from booking through reviews.

According to the company, the study has been in the works for two years in partnership with the racial justice organization Color of Change , with input from several social justice nonprofits, including Asian Americans Advancing Justice and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People .

“It’s really hard to change what you can’t measure,” Mr. Chesky said. “Then hopefully we will use this data to continue to evolve our platform and reduce the bias.”

Its tech focus — on the platform rather than the in-person experience — won’t address incidents of in-person bias. Through its existing Open Doors policy , Airbnb offers to find a guest an alternative place to stay if they feel they have been discriminated against by a host.

“In a departure from its peers in Big Tech who pass off structural problems on the behavior of individual users, with Project Lighthouse, Airbnb is attempting to take responsibility for how tech platforms create the opportunity for harm at scale,” wrote Jade Magnus Ogunnaike, senior campaigns director at Color Of Change, in an email.

Experiences in the digital age

Airbnb doesn’t just rent lodgings. Through its Airbnb Experiences branch, it offers classes in mole making with an Indigenous cook in Mexico City, a music and cultural tour of Havana with a D.J. and walks among penguins with a conservationist in South Africa.

During the pandemic, many of its Experiences went virtual . Now, via Zoom, armchair travelers can visit an animal rescue farm in Connecticut, follow a plague doctor through Prague and sit in on a songwriting session in Nashville.

After Airbnb’s layoffs, many wondered whether Airbnb Experiences, long rumored to be losing money, would be shelved, too. In January , it had 50,000 Experiences in 1,000 cities. During the pandemic, the division was shut down, and later transitioned, with a fraction of its offerings, online. Today, it has 700 virtual Experiences generating $2 million in bookings over the past five months. In-person Experiences have resumed in more than 70 countries with restrictions on group sizes, though the company declined to say how many Experiences are available in person and how much money they are making.

“I would be surprised if they drop it completely,” Mr. Mody, of Boston University, said. “They don’t want to be just a home rental company. Travel is about experiencing the destination in its entirety and they want to play a role in that.”

The company said it stands by Experiences, even waiving its take — which is normally 20 percent — for its Social Impact Experiences , which include playing with shelter cats in Osaka, Japan ($25) and learning beat-making with an organization devoted to teaching underserved youth ($75).

“Experiences was hit hard by social distancing,” Mr. Chesky said, maintaining that the online transition has been successful. “In a world where there’s not a lot of things to do, we think there’s a window for Airbnb Experiences,” he said.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

UT Urban Information Lab

The Urban Information Lab uses emerging information technologies to better understand, measure, plan, and develop our urban environments.

April 7, 2024 , Filed Under: Projects

Cities reshaped by Airbnb: A case study in New York City, Chicago, and Los Angeles

- The Director

- News & Events

- Digital twin

- Miscellaneous

Become a member today, It's free!

Remember me

Send my password

Case study on the impact of covid-19 on airbnb - researchandmarkets.com.

The "The impact of COVID-19 on Airbnb: Case Study" report has been added to ResearchAndMarkets.com's offering.

Travel restrictions in place, cancellations increased and therefore occupancy down. Hosts are suffering from minimal income from their properties and Airbnb is suffering from a lack of commission from these bookings. This case study looks at how the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting Airbnb and assesses the company's response.

Key Highlights

- Airbnb is unique in that the travelers are not their only customers. Hosts use the Airbnb platform to advertise properties, and benefit from the awareness Airbnb has in the market. Different to Online Travel Agencies (OTA's) such as Booking.com or TripAdvisor, the hosts are in most cases individual people who are renting out their own homes, and therefore do not have the bargaining power, cash reserves or brand image that hotels would do on other OTA's.

- Hosts are welcoming a dramatic drop in guest numbers, and in turn not receiving any income from their properties. For hosts who rely upon Airbnb for their income, it poses a worry on being able to make mortgage payments, pay bills and survive themselves during the pandemic. Airbnb's current free cancellation period up until May 31st for bookings made on or before March 14th, mirrors that offered by hotels, Airbnb's indirect competitor. However, the hosts have to offer the refunds on this personally, and unlike hotels do not have the cash reserves and ability to do so.

- The scale and extent of Airbnb's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic should be carefully thought about, as each move they make will make a large difference to how Airbnb will operate after the height of the pandemic is over. Detrimental stories that have emerged in the press such as hosts offering COVID-19 Retreats' in the UK despite national lockdown rules and the backlash of troubles in obtaining refunds for stays and experiences, could leave a bad image of the brand in the future.

- This report provides insight into how COVID-19 is impacting Airbnb and looks at the affects the pandemic is having on Airbnb's relationship with both guests and hosts.

- It also analyzes the company's response to the current crisis.

Key report benefits:

- Gain an overview of the current global COVID-19 situation

- Understand the impact that COVID-19 is having on the lodging industry

- Assess the impact on Airbnb

- Understand what the future may hold for Airbnb

Key Topics Covered:

Current COVID-19 Overview

- Airbnb Overview

- Impacts on Airbnb

- Airbnb's Response

- SWOT Analysis

- Airbnb post-COVID-19

Companies Mentioned

For more information about this report visit https://www.researchandmarkets.com/r/h93voz

About ResearchAndMarkets.com

ResearchAndMarkets.com is the world's leading source for international market research reports and market data. We provide you with the latest data on international and regional markets, key industries, the top companies, new products and the latest trends.

View source version on businesswire.com: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200616005562/en/

ResearchAndMarkets.com Laura Wood, Senior Press Manager [email protected] For E.S.T Office Hours Call 1-917-300-0470 For U.S./CAN Toll Free Call 1-800-526-8630 For GMT Office Hours Call +353-1-416-8900

Related News

@ the bell: the market sell-off continues, @ the bell: market drop and overseas tensions hurt tsx, recent u.s. press releases, update: new aurinia presentation details at the 2024 bloom burton & co. healthcare investor..., coursera receives industry-first authorized instructional platform designation from the american..., philip morris international to host webcast of 2024 first-quarter results, featured news links, this gambling tech stock is future-proofing the world’s casinos and has no direct competition, q precious & battery metals contracts first class drilling for quebec projects, why the tonopah gold project is one to watch, discover your next investment at this free online conference, targeting nevada and ontario for the critical minerals supply chain, asset sale allows biotech company to refocus on the high value dermatological market.

Get the latest news and updates from Stockhouse on social media

Follow STOCKHOUSE Today

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2024

Estimated public health impact of concurrent mask mandate and vaccinate-or-test requirement in Illinois, October to December 2021

- François M. Castonguay 1 , 2 , 4 ,

- Arti Barnes 3 ,

- Seonghye Jeon 1 , 2 ,

- Jane Fornoff 3 ,

- Bishwa B. Adhikari 1 , 2 ,

- Leah S. Fischer 1 , 2 ,

- Bradford Greening Jr. 1 , 2 ,

- Adebola O. Hassan 3 ,

- Emily B. Kahn 1 , 2 ,

- Gloria J. Kang 1 , 2 ,

- Judy Kauerauf 3 ,

- Sarah Patrick 3 ,

- Sameer Vohra 3 &

- Martin I. Meltzer 1 , 2

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1013 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

201 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Facing a surge of COVID-19 cases in late August 2021, the U.S. state of Illinois re-enacted its COVID-19 mask mandate for the general public and issued a requirement for workers in certain professions to be vaccinated against COVID-19 or undergo weekly testing. The mask mandate required any individual, regardless of their vaccination status, to wear a well-fitting mask in an indoor setting.

We used Illinois Department of Public Health’s COVID-19 confirmed case and vaccination data and investigated scenarios where masking and vaccination would have been reduced to mimic what would have happened had the mask mandate or vaccine requirement not been put in place. The study examined a range of potential reductions in masking and vaccination mimicking potential scenarios had the mask mandate or vaccine requirement not been enacted. We estimated COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations averted by changes in masking and vaccination during the period covering October 20 to December 20, 2021.

We find that the announcement and implementation of a mask mandate are likely to correlate with a strong protective effect at reducing COVID-19 burden and the announcement of a vaccinate-or-test requirement among frontline professionals is likely to correlate with a more modest protective effect at reducing COVID-19 burden. In our most conservative scenario, we estimated that from the period of October 20 to December 20, 2021, the mask mandate likely prevented approximately 58,000 cases and 1,175 hospitalizations, while the vaccinate-or-test requirement may have prevented at most approximately 24,000 cases and 475 hospitalizations.

Our results indicate that mask mandates and vaccine-or-test requirements are vital in mitigating the burden of COVID-19 during surges of the virus.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Public health mandates or requirements are laws put into place to promote healthy behaviors that mitigate disease burden. The mechanisms through which these policies interact with public health can vary substantially. For instance, a mask mandate aims to reduce disease transmission and a vaccinate-or-test requirement aims to reduce exposure to infectious cases through testing and also reduce the incidence of severe disease and mortality through vaccination. Several studies have estimated the impact of face mask mandates [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] and vaccination requirements [ 5 , 6 ] on COVID-19 transmission.

Facing a surge in COVID-19 cases during the fall of 2021 due to the emergence of the Delta variant [ 7 ], the Governor of Illinois issued an executive order on August 26, 2021 [ 8 ] that required workers in certain frontline professions ( e.g. , healthcare workers, school personnel, higher education personnel, and state owned or operated congregate facilities) to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (i.e., at least receive the first dose of a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine series), or undergo, at a minimum, weekly testing for COVID-19 if they remained unvaccinated by September 19, 2021 [ 9 ]. At the latest, individuals had to receive their second dose of a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine series 30 days after the September 19 th deadline [ 9 ]. There was also a mandate that required face mask use for any individual in a public indoor setting, beginning August 30, 2021, regardless of vaccination status. The August 26, 2021 executive order [ 8 ] was issued while the rate of cases continued to rise steeply, despite an earlier mask mandate for schools, daycares, and long-term care facilities enacted on August 4, 2021 [ 10 ]. The Delta variant represented more than 99% of sampled strains in Illinois at that point [ 7 ] and healthcare capacity was strained.

In this paper, we provide estimates of cases and hospitalizations averted by the concomitant mask mandate and vaccinate-or-test requirement in Illinois between October 20 and December 20, 2021. We estimate separately the impact of increases in masking and vaccination. We adjust for a wide range of compliance levels by estimating the impact for various levels of mask-wearing pre- and post-mandate, and for various potential levels of vaccination uptake in the front-line workforce that would follow the announcement of the vaccinate-or-test requirement.

We estimated the impact of increases in masking and vaccination on COVID-19 incidence in Illinois from October 20 to December 20, 2021. Previous reports have shown that use of face masks reduces SARS-CoV-2 transmission [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. We simplified estimating the impact of mask wearing, hereby referred to as mask effectiveness, by using (i) an average estimate of mask efficacy and (ii) an average percent of population compliant with correct mask wearing (see Technical Appendix for more details). Footnote 1 For vaccines, the effectiveness of the vaccinate-or-test requirement depends on the difference between the percentage of population that complied with the executive order to vaccinate-or-test, and the percentage that were already vaccinated. This research activity was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. Footnote 2

We used CDC’s COVIDTracer modeling tool [ 14 ] to build an epidemic curve that mimicked the observed one in Illinois over the two-month period (October 20 - December 20, 2021). Footnote 3 Similar to other studies [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] (Castonguay FM, Borah BF, Jeon S, Rainisch G, Kelso P, Adhikari BB, Daltry DJ, Fischer LS, Greening Jr B, Kahn EB, Kahn GJ, Meltzer MI: The Public Health Impact of COVID-19 Variants of Concern on the Effectiveness of Contact Tracing in Vermont, United States, unpublished), the two-month duration balances the need for sufficient time to pass after the start of the mandate to allow for an adequate assessment of the impact of the interventions being studied. Simultaneously, it aims to limit the potential for unknown confounding factors that may alter the impact of the interventions. We assumed that the effectiveness of interventions remained constant over the two-month study period. Those vaccinated following the vaccinate-or-test requirement should have achieved full vaccine-induced immunity Footnote 4 by mid-October 2021, which matches the start of our analytic timeframe. Footnote 5 COVIDTracer uses a compartmental Susceptible–Exposed–Infectious–Recovered (SEIR) mathematical model [ 19 ]. A user enters location-specific COVID-19 case counts, vaccination levels, a set of parameters describing COVID-19 epidemiology ( e.g. , basic reproduction number), and estimates of the effectiveness of the interventions (Table 1 ) (see Technical Appendix for details and Appendix Table A4 for a list of Illinois-specific inputs).

Impact of mask mandate

To model the impact of mandate-induced increased mask effectiveness, we first inputted a selected value from the range provided in Table 1 into COVIDTracer. The pre-mandate mask effectiveness range was 3.6%–16.8% and post-mandate mask effectiveness range of 6.1%–23.3%. For baseline analysis, we used post-mandate mask effectiveness of 14.2%, assuming 20% mask efficacy and 71% compliance. As it is very difficult to measure the degree of compliance with effective mask wearing in any population, we therefore constructed 24 scenarios of combinations of pre-and post-mandate mask effectiveness. We avoided over-estimating the impact of the mask mandate by using pre-mandate mask effectiveness values of less than 20% and only one post-mandate mask effectiveness value of over 20% (see Sensitivity Analyses).

We then “fitted” the curve of cumulative cases modeled by COVIDTracer to the jurisdiction’s reported cases by altering the percentage reduction in transmission ascribed to vaccine and various Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs). The estimated percentage reduction in transmission that minimized the difference ( i.e., minimized the mean squared error) between the fitted and reported cumulative case curves is the estimate of the effectiveness of non-CICT NPIs (see Appendix for further details). Note that, because there were no measurements of the degree of under-reporting, we had to use the reported cases without any adjustments for possible under-reporting. Correcting for under-reporting may well have increased the estimates of cases and hospitalizations averted, for both mandates. Finally, we simulated what would have occurred without the mask mandate by re-setting the impact of mask effectiveness to one of 2 pre-mandate effectiveness levels (7.2% and 11.2%). The resulting plots are the number of cases that would have occurred without the mask mandate. The difference between the hypothetical plots of cases without mandate-induced increases in mask effectiveness and the plot of the reported cases (which includes the impact of mask mandate) are the cases averted due to the mask mandate. By “fitting the curve” (finding the best match between the SEIR model and the observed data), this methodology prevents over- or under-estimating the combined impact of all interventions.

Sensitivity analyses: mask mandate

Mask wearing compliance depends on several locality factors [ 32 , 33 ]. As noted earlier, it is very difficult to measure the degree of compliance in large populations. We therefore constructed 24 scenarios of combinations of pre-and post-mandate mask effectiveness (Appendix Table A1 ).

Impact of vaccinate-or-test requirement

To estimate the impact of the vaccinate-or-test requirement, we followed the same process as described above for masking (Table 1 ; see the Appendix for further details). The number of cases averted by the vaccinate-or-test requirement depended on (i) the baseline, pre-requirement, vaccination coverage, and (ii) the increase in vaccination coverage attributable to the requirement. We obtained an estimate of 929,370 frontline workers in Illinois who were potentially affected by the vaccinate-or-test requirement (see Appendix Table A2 ). The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) reported that, for the period analyzed, vaccination coverage of the staff working in certified Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS-certified) nursing homes in Illinois increased from 64.8% to 75.9%––an 11.1 percentage point increase in coverage (see Appendix Table A3 ). We used this 11.1 percentage point increase (equivalent to 103,160 additional persons vaccinated) as a base case scenario for analyzing the impact of the vaccinate-or-test requirement.

Sensitivity analyses: vaccinate-or-test requirement

We do not know what proportion of the 11.1 percentage point increased coverage was due to the vaccinate-or-test requirement. Other factors, such as intent to be vaccinated regardless of the requirement or other requirements/mandates ( e.g. , the federal mandate for CMS facilities announced during the study period), could have contributed to the increase. To address this uncertainty, we evaluated the impact of an arbitrary assumption that only half of the recorded increase in vaccine coverage could be attributable to the mandate (i.e., a 5.6 percentage point increase, equivalent to 51,580 additional persons vaccinated). Note that the potential indirect impact that the vaccinate-or-test requirement could have had on the general population [ 6 ] is not accounted for, which may have increased the overall impact of the requirement.

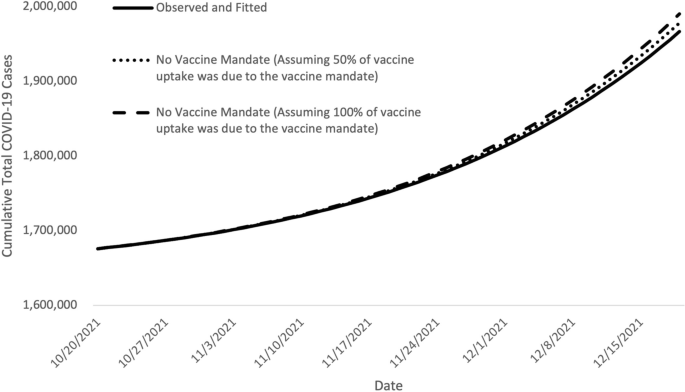

In Fig. 1 , we present the plot of the cases assuming the post-mandate mask effectiveness of 14.2% (calculated assuming 20% mask efficacy and 71% compliance; represented by the solid black line in Fig. 1 ). This plot is then compared to the hypothetical plots of increased cases, assuming no mask mandate and a continuation of pre-mask effectiveness of either 7.2% or 11.2% (dotted and dashed lines). The cumulative difference between the dotted or dashed plotted lines and the solid line plot is the estimate of additional cases averted due to the mask mandate.

Fitted epidemic curves of COVID-19 case counts showing the impact of the mask mandate

Notes: Fitted epidemic curve of observed COVID-19 case counts, assuming a post-mandate mask effectiveness of 14.2%, and simulated epidemic curves assuming no mandate and continuation of pre-mandate mask effectiveness of either 7.2% or 11.2% (all three for the October 20 – December 20, 2021 period). The solid line is Illinois’s observed (fitted) cumulative COVID-19 case counts, and the broken lines are the simulated curves illustrating the cumulative total COVID-19 cases for the various scenarios that might have occurred if the mask mandate had not been enacted and mask efficacy was 20%. The differences between the solid and broken lines show the benefits of the mask mandate with greater divergence between the solid and broken lines indicating a greater impact. All results assume that the effects of nonpharmaceutical interventions —including masks—were constant over the two months shown

To calculate a lower-bound estimate of cases averted, we assumed that the mask mandate increased mask effectiveness from 3.6% to 6.1%. This resulted in an estimate of 149,817 additional cases and 3,028 additional hospitalizations averted due to the mask mandate (Table 2 ). We calculated an upper-bound estimate by increasing the mask effectiveness for pre- and post-mandate to 10.2% and 21.3%, respectively. This resulted in an upper estimate of 1,820,764 additional cases and 36,801 additional hospitalizations averted due to the mask mandate (Table 2 ). The remainder of the results in Table 1 show the estimates of cases and hospitalizations averted from another 10 scenarios. The results from all 24 scenarios of combinations of pre-and post-mandate mask effectiveness are presented in Appendix Table A1 .

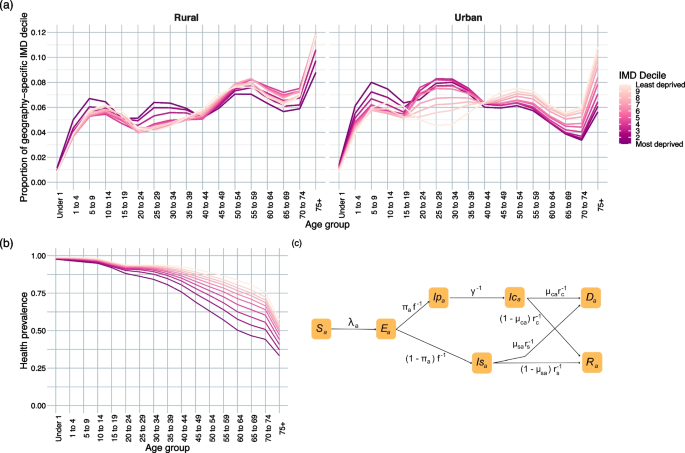

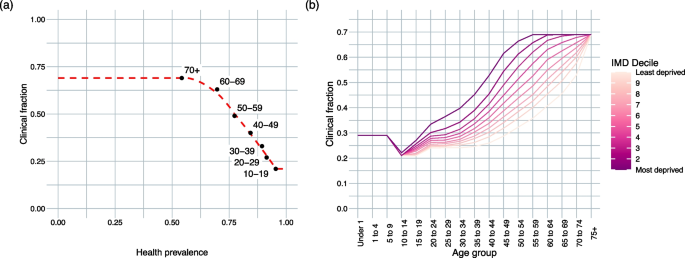

Assuming that the vaccinate-or-test requirement resulted in an 11.1 percentage point increase in persons vaccinated, we estimated that 23,593 cases and 477 hospitalizations were averted (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ).

Fitted epidemic curves of COVID-19 case counts showing the impact of the vaccinate-or-test requirement

Notes: Fitted epidemic curve of observed COVID-19 case counts and of two assumed increases in vaccination coverage attributable to the announcement of the vaccinate-or-test requirement (for October 20 – December 20, 2021). These represent approximately 51,580 and 103,160 individuals vaccinated because of the vaccinate-or-test requirement. The solid line is Illinois’s observed cumulative COVID-19 case counts, and the dashed and dotted lines are the simulated curves illustrating the cumulative total cases for scenarios where there would have been a lower vaccine uptake without the vaccinate-or-test requirement. The differences between the solid and dashed or dotted lines show the number of cases averted by the vaccinate-or-test requirement. All results assume that the effects of other nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) were constant over the two months analyzed

Sensitivity analyses: Vaccinate-or-test Requirement

When we assumed that only half of the increase was attributable to the vaccinate-or-test requirement, an estimated 11,571 cases and 234 hospitalizations were averted by the vaccinate-or-test requirement (Table 3 and Fig. 2 ).

We estimated that increases in masking following the announcement of the mask mandate may have averted at least 58,000 cases in Illinois. The vaccinate-or-test requirement among frontline workers averted up to 24,000 cases during the period studied. The assumed post-mandate mask effectiveness (6.1% - 21.1%) was the most influential variable assessing the impact of mask mandates.

Our results provide data-driven evidence that can inform decision-making regarding public health interventions during times of surge. While there have been concerns regarding the negative impact of such mitigation measures [ 34 ], mask mandates are impactful [ 35 ] and vaccination requirements have demonstrated the ability to strengthen vaccination intentions across racial and ethnic groups, and even those who may be resistant [ 36 ]. Public adherence to these practices due to requirements as opposed to free choice is a more complicated debate. Several studies have demonstrated that while vaccine mandates may result in some vaccine hesitancy, they have been associated with improved vaccination rates [ 37 , 38 ]. Hospital staff vaccination reports have found that many employees chose vaccination over resignation [ 37 ].

Our study has limitations. Several factors made it difficult to use a direct causal identification methodology, such as difference-in-differences. These factors included the absence of a credible control group and several confounding factors due to the important period between the announcement of the intervention and when compliance was required. We had to make several assumptions because the precise impact that the concomitant mask mandate and vaccinate-or-test requirement in Illinois had on COVID-19 burden depended largely on several unobserved factors, namely mask quality, level of mask-wearing pre- and post-mandate, and the proportion of vaccine uptake attributable to mandate. Further, while we estimated the impact of increases in masking and vaccination separately, there may have been unaccounted synergistic effects from combining both interventions [ 39 ]. We also assumed that the impact of face masks and vaccination remained constant over the period of study. To reduce the potential impact of such assumption, we limit our study period to two months. We do not account for partial immunity ( e.g., if an individual received their first vaccine shot during the study period), and hence assume individuals are either fully susceptible (because the individual was never vaccinated or never infected, or because immunity acquired through vaccination or prior infection was more than 180 days ago [ 29 ] and is no longer protective) or fully immune (due to prior infection or vaccination) during the two-month study period. By doing so, we may underestimate the impact of the policies (e.g., because the first dose of a two dose COVID-19 vaccine series may still provide some protection [ 40 ] which would increase the impact of the vaccinate-or-test requirement) or overestimate the impact of the policies (e.g., because those protected by the first dose of a two dose COVID-19 vaccine series would not have been protected by masks), with the overall direction of the bias being uncertain. There is also the possibility that the vaccinate-or-test requirement for frontline workers may have had an impact on the general population, as the requirement may have signaled the importance of vaccination for individuals not directly covered by the vaccinate-or-test requirement [ 6 ]. Finally, we assumed that there are no differences in disease transmission that are attributable to age, location, or occupation—in other words, every individual in the population is assumed to have the same risk of catching COVID-19 and is assumed to behave in the same way as any other individual. Those affected by the vaccinate-or-test requirement were frontline professionals who could have had potentially very different mixing patterns compared to the general population.

During the two-month study period, almost 2,000 hospitalizations were averted according to our model. Had these hospitalizations occurred, they would have had a significant impact on an already strained healthcare system. These findings can help control viral transmission of diseases other than COVID-19 at both hospital and community levels, and will help refine future decisions on the timing and scale of such public health measures should we find ourselves again in a similar healthcare crisis.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Mask effectiveness is the product of (i) mask efficacy and (ii) mask compliance. Mask efficacy is defined as the extent to which masks reduce the output and uptake of the virus droplets/aerosols (range 10%-30%, see Ueki et al. [ 11 ]) and mask compliance is defined as the percentage of the population properly wearing masks.

See e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

This modeling tool has been used by several studies to estimate the impact of CICT [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] (Castonguay FM, Borah BF, Jeon S, Rainisch G, Kelso P, Adhikari BB, Daltry DJ, Fischer LS, Greening Jr B, Kahn EB, Kahn GJ, Meltzer MI: The Public Health Impact of COVID-19 Variants of Concern on the Effectiveness of Contact Tracing in Vermont, United States, unpublished) along with instructions provided for replicating this analysis and model use [ 15 , 16 ].

We defined fully vaccinated as either having received two doses of the monovalent mRNA BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech, Comirnaty) or monovalent mRNA mRNA-1273 (Moderna, Spikevax) COVID-19 vaccine, or one dose of the single-dose adenovirus vector-based Ad26.COV.S (Janssen [Johnson & Johnson]) COVID-19 vaccine [ 48 ].

Recall that the vaccinate-or-test requirement required individuals to get their first dose of a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine series, or undergo, at a minimum, weekly testing for COVID-19 if they remained unvaccinated by September 19, 2021 [ 9 ]. CDC recommended at least three weeks between two doses for Pfizer-BioNTech and 28 days between two doses for Moderna any two vaccine [ 49 ]. To comply with the requirement, individuals had to receive their second dose of a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine series on October 19, 2021, at the latest.

Abaluck J, Kwong LH, Styczynski A, Haque A, Kabir MA, Bates-Jefferys E, Crawford E, Benjamin-Chung J, Raihan S, Rahman S, and others. Impact of community masking on COVID-19: a cluster-randomized trial in Bangladesh,. Science . 2022;375(6577):eabi9069.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bundgaard H, Bundgaard JS, Raaschou-Pedersen DET, von Buchwald C, Todsen T, Norsk JB, Pries-Heje MM, Vissing CR, Nielsen PB, Winslow UC, et al. Effectiveness of adding a mask recommendation to other public health measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in Danish mask wearers: a randomized controlled trial. Annals Internal Med. 2021;174(3):335–43.

Article Google Scholar

Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, Tufekci Z, Zdimal V, Van Der Westhuizen HM, Von Delft A, Price A, Fridman L, Tang LH, et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2021;118(4):e2014564118.

Eikenberry SE, Mancuso M, Iboi E, Phan T, Eikenberry K, Kuang Y, Kostelich E, Gumel AB. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infectious disease modelling. 2020;5:293–308.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mohammed I, Nauman A, Paul P, Ganesan S, Chen KH, Jalil SMS, Jaouni SH, Kawas H, Khan WA, Vattoth AL, et al. The efficacy and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in reducing infection, severity, hospitalization, and mortality: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin immunother. 2022;18(1):2027160.

Howard-Williams M, Soelaeman RH, Fischer LS, McCord R, Davison R, Dunphy C. Association Between State-Issued COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates and Vaccine Administration Rates in 12 US States and the District of Columbia. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e223810–e223810.

E. B. Hodcroft, "CoVariants: SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and Variants of Interest,". Available: https://covariants.org/per-country?region=United+States&country=Illinois . Accessed 29 Aug. 2023.

JB Pritzker, Governor, "Executive Order 2021-20 (COVID-19 EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 87)," Governor JB Pritzker © 2023 State of Illinois, August 26, 2021. [online] https://www.illinois.gov/government/executive-orders/executive-order.executive-order-number-20.2021.html .

JB Pritzker, Governor, "Executive Order 2021-22 (COVID-19 EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 88)," Governor JB Pritzker © 2023 State of Illinois, September 03, 2021. [online] https://www.illinois.gov/government/executive-orders/executive-order.executive-order-number-22.2021.html .

JB Pritzker, Governor, "Executive Order Number 18 (COVID-19 EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 85)," Governor JB Pritzker © 2023 State of Illinois, August 04, 2021. [online] https://www.illinois.gov/government/executive-orders/executive-order.executive-order-number-18.2021.html .

Ueki H, Furusawa Y, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Imai M, Kabata H, Nishimura H, Kawaoka Y. Effectiveness of face masks in preventing airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. MSphere. 2020;5(5):e00637-20.

Cheng Y, Ma N, Witt C, Rapp S, Wild PS, Andreae MO, Poschl U, Su H. Face masks effectively limit the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Science. 2021;372(6549):1439–43.

Li Y, Liang M, Gao L, Ahmed MA, Uy JP, Cheng C, Zhou Q, Sun C. Face masks to prevent transmission of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of infection control. 2021;49(7):900–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , "COVIDTracer and COVIDTracer Advanced," 19 January 2021. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/COVIDTracerTools.html . Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Jeon S, Rainisch G, Lash RR, Moonan PK, Oeltmann JE, Greening B, Adhikari BB, Meltzer MI, et al. Estimates of cases and hospitalizations averted by COVID-19 case investigation and contact tracing in 14 health jurisdictions in the United States,. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(1):16–24.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rainisch G, Jeon S, Pappas D, Spencer K, Fischer LS, Adhikari B, Taylor M, Greening B, Moonan P, Oeltmann J, Kahn EB, Washington ML, Meltzer MI. Estimated COVID-19 Cases and Hospitalizations Averted by Case Investigation and Contact Tracing in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(3):e224042–e224042.