- Abstract/Non-Verbal Reasoning Test

- Academic Assessment Services (AAS) Scholarship Test (Year 7)

- Brisbane State High School Selective Test (Sit in Grade 5)

- Brisbane State High School Selective Test (Sit in Grade 6)

- GATE Test (Gifted & Talented) Academic Selective Test - ASET in WA

- IELTS General Training Writing

- IGNITE Program South Australia Exam (a Selective Schools Test offered by ACER®)

- NAPLAN Grade 5

- Narrative Writing (Written Expression) Test

- NSW Selective Schools Test (HSPT)

- Numerical Reasoning Test

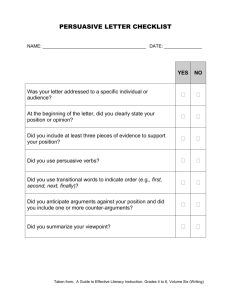

- Persuasive / Argumentative Writing Test (with Topics & Real-Life Examples)

- QLD Academies SMT Selective Grade 7 Entry

- Reading Comprehension Test Practice (Grade 5, Grade 6, Grade 7)

- Scholarship Tests (Year 7 – Level 1) offered by ACER®

- Scholarship Tests (Year 7) Offered by Edutest®

- SEAL/SEALP (Select Entry Accelerated Learning Program) Exams Offered by ACER®

- Select Entry Accelerated Learning Programs (SEAL/SEALP) Offered by Edutest®

- Test Practice Questions - Free Trial

- The ADF Aptitude Test (Defence Force YOU Session)

- Verbal Reasoning Tests

- Victorian Selective Schools Test

- ONLINE COURSES

- TEST PAPERS

- WRITING PROGRAMS

- SITE MEMBERSHIP

- WRITING CLUB

- BLOG & ARTICLES

- FREE VIDEOS

- WRITING PROMPTS

- SAMPLE ESSAYS

- MASTERCLASS VIDEOS

- Get Started

NAPLAN - Grade 5 - Persuasive Writing

You'll find writing prompts in here to practice for the Year 5 NAPLAN writing test. This area contains only persuasive writing and argumentative writing prompts.

QUESTION 1 - Are libraries dead? Libraries are no longer needed …

QUESTION 2 - Homework doesn't aid learning. Homework doesn't aid learning. …

QUESTION 3 - Prizes for participating. There shouldn't be any prizes g…

QUESTION 4 - Ranking and reviewing teachers The internet allows people to r…

QUESTION 5 - Hard work or talent? (NAPLAN Grade 5) Hard work is more important than talent. Do you agree or disagree? Argue your point. …

QUESTION 5A - Hard work or talent? (NAPLAN Grade 5) Hard work is more important tha…

QUESTION 6 - In captivity or in the wild? Animals should not be kept in c…

QUESTION 7 - Exotic pets Many exotic animals like koalas…

QUESTION 8 - Only child or siblings It is better to be an only chil…

QUESTION 9 – Home schooling should be prohibited Home schooling should not be al…

QUESTION 10 – Everyone should be vegetarian Everyone should be vegetarian. …

QUESTION 11 - Inland or Coast? Inland or near the coast? Some …

QUESTION 12 - Virtual or Physical Recreation? Computer games or sport? Some p…

QUESTION 13 - Rules Rules direct conduct, that is, …

QUESTION 14 - Inventions Choose an invention. This inven…

Have A Question?

Persuasive writing is about much more than PEEL, TEEL, NAPLAN, the HSC – or any other acronym!

If you can convince other people that your opinion is correct, you have a big advantage in life.

Learning to write strong, persuasive arguments can help you to participate and succeed, including as a student, employee, business owner, consumer, vendor, and citizen. It’s a useful skill in many face-to-face and in online settings, including in community meetings and on social media platforms like YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram.

In a democracy, communities, states, and nations benefit from the spirited interactions of informed individuals exchanging different perspectives with arguments that acknowledge and evaluate different views rationally, supported by evidence. Sadly, this is often not the case, with increasing levels of political polarisation and a decreasing tolerance for rational debate around a range of important social, economic, health, scientific, religious, intellectual, human rights, and environmental issues.

For students, learning to write arguments has an additional and more concrete benefit: it’s the main form of assessment in many school subjects, including many humanities subjects in the Higher School Certificate ( HSC ). In general, argumentative essays become more frequent and important for students as they progress through school.

In Australia, the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy ( NAPLAN ) has a big – and some think outsized – influence on how argumentative essays are taught and tested. NAPLAN requires students in Years 3, 5, 7, and 9 to write an argument or a narrative in response to a provocative prompt, e.g. that “Too much money is spent on toys and games”.

In practice, many teachers dedicate lots of class time preparing students for NAPLAN writing tests. Some teachers are expected to “teach to the test” by reverse-engineering NAPLAN writing tasks by reference to marking criteria.

1. How do teachers in Australia evaluate whether an essay is persuasive?

There are many ways of assessing writing quality. For example, in our speech pathology practice we use norm-referenced, standardised writing tests , informal discourse level probes (e.g. adapted from researchers like Koutsoftas and Gray), and our own in-house criterion-referenced test to look at students’ writing strengths and challenges. We then work with clients and families to set functional writing goals, and to plan intervention, using an explicit, direct approach to teaching writing .

In Australia, we also look at the NAPLAN Persuasive Writing Marking Guide and the Australian Curriculum: English. These documents are both influenced by an academic theory of language and argument called systemic functional linguistics ( SFL ).

I doubt many people outside the education sector know much about SFL. Even as a speech-language pathologist, I didn’t know much about the extent of its influence on how writing is taught and tested in Australia until I read a terrific recent paper by Damon Thomas from the University of Queensland (reference below).

It’s worth looking at SFL and its claims, briefly, because the theory has a real world effect on the way that many primary and secondary students are taught to write essays in Australia. It also helps us to understand the jargon used to describe and evaluate persuasive writing.

2. We write differently for different purposes

In (very) simple terms, SFL looks at the relationships between language and its functions in different contexts. It shares many common features with models of oral language used by speech pathologists in oral language therapy , including Bloom and Lahey’s famous model of language form, content and use .

SFL is often depicted like this:

Source: Thomas (2022)

Without doing a deep dive into all the jargon, this is not the clearest model – unless you are a linguist.

In basic terms, SFL seeks to connect language structure (e.g. phonology, syntax) and content (e.g. vocabulary and semantics) with its purpose (function) in different real world situations and cultural contexts (e.g. real world social or academic situations). A detailed analysis of SFL and its claims is beyond the scope of this article, but you can read more about it here , here and in the research referred to below.

3. We write things for three main purposes: to engage, to inform, and to persuade

In SFL, written texts are typically grouped into three broad categories, based on function or purpose:

- Texts that engage , e.g. recounts and narratives ;

- Texts that inform , e.g. explanations and reports ; and

- Texts that evaluate , e.g. arguments and responses that persuade .

Over time, writers of written genres (types of text) have evolved different structures to achieve their different purposes. To become effective writers, students should be taught about these different structures, and practice writing different types of texts that are appropriate for the purpose and context. This insight has a big effect on the way the Australian Curriculum approaches writing instruction – from Kindergarten to the end of Year 12.

4. There are four sub-types of persuasive writing

In this article, we’re focused on the structure of one subcategory of texts that evaluate: argumentative texts, also known as persuasive writing or persuasive texts . According to SFL, there are four sub-types (or genres) of these texts, which again differ in structure based on their purpose:

- Analytical expositions , written to persuade readers to believe one perspective on an issue. For example, a student might be asked to explain their views on whether mobile phones should be allowed in the classroom.

- Hortatory expositions , written to persuade readers to take some action based on the writer’s position. For example, a student might be asked to write an essay to persuade (“exhort”) others to stop using plastic straws.

- Discussions , written to discuss an issue from more than one perspective and to persuade readers to agree with one position. For example, a student might be asked to consider and evaluate arguments for and against Australia becoming a republic and to reach a well-reasoned conclusion.

- Challenges , written to rebut an established position. For example, a student might be asked to argue that the minimum age for voting should be reduced to 16 years in the jurisdiction in which they live.

5. How many Australian students are taught to structure their persuasive writing responses: The five-paragraph structure and ‘PEEL’ paragraphs

The structures of analytical, hortatory, discussion and challenge expositions are all slightly different, reflecting their different purposes. For example, the discussion text explicitly requires students to look at issues from multiple perspectives. Despite these differences, however, effective persuasive writing across the different genres typically involves writing texts with five main parts (or stages), in the following sequence:

- An introduction or thesis , usually including a statement of the student’s position and a preview of the arguments supporting it.

- P oint or T opic of the argument;

- E laboration and explanation of the point;

- E vidence for the point, including examples; and

- L inking sentence, which connects the point back to the student’s thesis and/or to the next paragraph.

- A conclusion or reiteration composed of a review of the main arguments, and a restatement of the student’s thesis or position.

This observation, derived from SFL, has led many Australian teachers to focus on teaching their students:

- the so-called five paragraph essay structure; and

- PEEL (or TEEL) paragraph writing structures for their arguments in essays, made up of P oint (or T opic), E laboration, E vidence, and L ink. (I prefer ‘PEEL’ over ‘TEEL’ as it helps some students to distinguish the specific p oint being made in an individual argument/paragraph from the overall t opic of the essay.)

In Australia, many high school teachers focus on teaching PEEL paragraph-writing to students. It is especially common to see students practising PEEL paragraph writing as they prepare for NAPLAN tests in Years 7 and 9.

6. An example PEEL paragraph

Let’s say a student in Year 7 decides to disagree with the prompt that “too much money is spent on toys and games”. In the first paragraph, she states her position (her thesis ) and then previews her main arguments, stating that “Many toys and games help children to develop skills and fitness (argument 1), do not cost much money compared to other expenses like food and housing (argument 2), and can help bring families together, improving family life (argument 3). In paragraph two, the student might write a PEEL paragraph to state her first argument:

7. There is much more to persuasive writing than the five-paragraph structure + PEEL

Unlike with speech and oral language, we are not biologically primed to learn to write . Students need to be taught how to do it. We’ve long advocated for explicit, sequenced writing instruction for all students, starting in Kindergarten . However, while explicit teaching of essay structures and PEEL can be helpful for beginners, it has also been criticised.

Some researchers think an over-emphasis on the five paragraph structure and PEEL:

- constrains students’ writing development, forcing students to write ‘colour-by-number’ essays that slavishly follow predictable ‘formulae’ that dictate what they should write sentence-by-sentence;

- forces teachers to teach it as ‘the correct way’ to maximise NAPLAN and HSC results by gaming the marking criteria; and

- may even have contributed to declines in writing outcomes.

In practice – working mainly with children with language and learning difficulties – we sometimes see students come to us trying to apply the PEEL formula without understanding the question. From time to time, we meet students who arrive at language therapy with pre-prepared, memorised essays (complete with quotes), with rigid plans to dutifully copy them out regardless of the question asked! This is – obviously – a terrible misuse of PEEL.

In writing, there is no single correct way to persuade – or, for that matter, to entertain, instruct, or explain things. Generations of students have learned to write persuasively without SFL concepts like PEEL.

In the recent study cited below, Thomas looked at the structural features of 60 high-scoring arguments written by students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9 as part of NAPLAN. He found, amongst other things, that many high-scoring students used the five-stage structure for their essays. However, he also found that many of them used a wider range of techniques and structures for their arguments and produced arguments that were longer and more nuanced. Further, many high scoring students didn’t include all elements of PEEL in their arguments. Notably, only three of the 60 essays included Link phrases.

Expert writers go far beyond PEEL. For example, take a quick look at the different structures and approaches used by essay-writing masters in this very small and unrepresentative selection of essays:

- “ Does Truth Matter? Science, Pseudoscience and Civilisation ” by Carl Sagan

- “ Death of the Moth ” by Virginia Woolf

- “ The Meditations ” by Marcus Aurelius

- “ How to use the Power of the Printed Word ” by Kurt Vonnegut

- “ On the Vanity of Words ” by Michel de Montaigne

- “ Once More to the Lake ” by E.B. White

- “ How to Do What you Love ” by Paul Graham

- “ On Self-Reliance ” by Ralph Waldo Emerson

8. The cognitive demands of persuasive writing

In contrast to the expert essays linked above, many primary and high school essays are one-sided and poorly supported. It takes a lot of time and effort for students to develop the cognitive skills necessary to write sophisticated argumentative essays.

Many students need to be taught explicitly how to look at issues from multiple perspectives. Many are likely to require significant teacher modelling and scaffolding to start with. For example, research tells us that:

- primary school-aged students rarely consider alternative perspectives when writing persuasive texts;

- many adolescents struggle to integrate multiple perspectives in their essays; and

- many older adolescents are unable to acknowledge and respond to counter-arguments in their writing.

Using our example above, our Year 7 student might have several good arguments to support her thesis against the idea that “too much money is spent on toys and games” but find it difficult to acknowledge in her essay that:

- other people think that too much money is spent on toys or games; and

- there are good reasons to think they might be right, e.g. amount of annual toy waste, high average number of toys owned by children, money could be spent on other things like education, health and family experiences.

Many people finish school and reach adulthood without learning to look at issues from more than one perspective or to anticipate or rebut counter arguments with evidence and reasons. We see the adverse effects of this problem play out daily in social media exchanges, especially on Twitter and Facebook!

To write persuasively, a student must learn:

- to accept that different people think different things from the student about all kinds of issues;

- to reflect on biases and the limitations of the student’s knowledge;

- that many real world issues are complex and nuanced, requiring sophisticated responses, trade-offs and an understanding of real world constraints;

- to use high quality evidence and reason to formulate, state and substantiate their position on a position; and

- anticipate, consider, and rebut counterarguments respectfully and with humility.

Over time, students (and adults) must learn how to consider different perspectives and arguments, to appraise multiple sources of (sometimes conflicting) evidence of varying quality, and to evaluate and make judgments between contrasting views.

9. The many language demands of persuasive writing tasks

In high school, persuasive writing tasks, including many NAPLAN and HSC exams, require advanced and higher level language skills. To even understand the question, students need:

- oral comprehension skills , including well-developed background knowledge and inferencing skills, phonological, syntactic and semantic knowledge; and

- adequate reading skills , including work recognition skills.

In addition to understanding the structure of argumentative essays, students need to plan and structure written responses using appropriate:

- simple , compound and complex sentences , and other complex syntax like relative clauses , that help provide the ‘machinery’ for students to express complex, nuanced ideas like “Although some people think that too much money is spent on toys and games, the better view is that money is often well spent on toys and games for several reasons including…”;

- well-formed paragraphs (see also, paragraph models , and descriptive paragraphs , and recounts );

- rhetorical devices, like logos, pathos, ethos, rhetorical questions, repetition, anaphora, onomatopoeia, and synecdoche;

- other higher level language and figurative language techniques like similes and metaphors , idioms , sayings , alliteration, assonance, personification, analogies , allusions, and hyperbole;

- humour, irony and sarcasm;

- vocabulary, including use of key academic verbs , and specific nouns and verbs and academic vocabulary generally ;

- cohesion, including verbal reasoning practice, linking ideas in different ways, e.g. with different combinations of because/but/so , before/after/until , if/while/although , despite/in spite of , and otherwise conjunctions and adverbs, transitions , and referring words (like pronouns , articles , determiners like “much” and “many” ), categories and semantic features ;

- punctuation, e.g. capital letters and full stops , proper noun capitalisation , quotation marks ); and

- spelling .

In some subjects, students also need to understand the language used in the text they are writing about , e.g. narrative structure for novels in English; as well as how to understand their school texts as a condition to writing about them.

This is all no small feat – especially for students with developmental and other language disorders , specific learning disorders (reading and/or writing) – and other neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD or autism, and some students with lifelong communication disabilities.

Bottom line

To prepare students for school success, the workplace, citizenship, and adulthood we need to teach them good argumentative writing skills, including how to tackle persuasive writing tasks at school. We’ve outlined some of the theories that underpin many teachers’ approaches to teaching and testing persuasive writing in Australia. We’ve also highlighted some of the cognitive and language challenges that make persuasive writing tasks so challenging for many students – especially in high school.

Teaching beginners the five-paragraph essay structure, and the ‘PEEL’ paragraph writing strategy may assist. However, as students master the basics, they should be encouraged to look beyond these supports, to look at issues from multiple perspectives, and to use a greater variety of language structures and devices flexibly to improve the effectiveness of their writing and the persuasiveness of their arguments.

Main source and recommended further reading : Thomas, D.P. (2022). Structuring written arguments in primary and secondary school: A systemic functional linguistics perspective, Linguistics and Education, 72 , accessed online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101120 .

This article also appears in a recent issue of Banter Booster, our weekly round up of the best speech pathology ideas and practice tips for busy speech pathologists, providers, speech pathology students, teachers and other interested readers.

Sign up to receive Banter Booster in your inbox each week:

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.

Share this:

David Kinnane

Banter Quick Tips: The stretchy-sound trick: How I teach beginners to read their first words

11 ways to improve writing interventions for struggling students

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

© 2024 Banter Speech & Language ° Call us 0287573838

Copy Link to Clipboard

- Arts & Humanities

3: NAPLAN* Persuasive Text sample work sheets – Primary

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

- NAPLAN 2012–2016 test papers

- NAPLAN national results

NAPLAN 2012–2016 test papers and answers

ACARA does not provide access to the NAPLAN tests after 2016. These tests are used for other projects related to the continued improvement of the National Assessment Program. ACARA notes the decision of the Acting Information Commissioner, Timothy Pilgrim, in the Marty Ross decision in support of its position. See our copyright information .

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing prompt – Imagine (Years 3 and 5) (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing, Year 3 (PDF 105 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading magazine, Year 3 (PDF 11 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading, Year 3 (PDF 500 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 3 (PDF 2.5 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, language conventions, Year 3 (PDF 321 KB)

NAPLAN 2016 Year 3 paper test answers (PDF 147 KB)

Year 5

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing prompt – Imagine (Years 3 5 only) (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing, Year 5 (PDF 106 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading magazine, Year 5 (PDF 14.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading, Year 5 (PDF 330 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 5 (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, language conventions, Year 5 (PDF 311 KB)

NAPLAN 2016 Year 5 paper test answers (PDF 145 KB)

Year 7

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing prompt – Sign Said (Years 7 9) (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing, Year 7 (PDF 105 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading magazine, Year 7 (redacted name on page 7) (PDF 18 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading, Year 7 (PDF 320 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (calculator) (PDF 1.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (non-calculator) (PDF 1.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, language conventions, Year 7 (PDF 327 KB)

NAPLAN 2016 Year 7 paper test answers (PDF 149 KB)

Year 9

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing, Year 9 (PDF 107 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, writing prompt – Sign Said, Years 7 9 (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading magazine, Year 9 (PDF 14.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, reading, Year 9 (PDF 333 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (calculator) (PDF 1.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (non-calculator) (PDF 1.7 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016 final test, language conventions, Year 9 (PDF 337 KB)

NAPLAN 2016 Year 9 paper test answers (PDF 150 KB)

top

Year 3

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, language conventions, Year 3 (PDF 645 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy, Year 3 (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading magazine, Year 3 (redacted image of face page 4) (PDF 6.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading, Year 3 (PDF 310 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing prompt (Years 3 5 only) (PDF 4.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing, Year 3 (PDF 121 KB)

NAPLAN 2015 Year 3 paper test answers (PDF 146 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading magazine, Year 5 (PDF 8.4 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing prompt (Years 3 5 only) (PDF 4.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy, Year 5 (PDF 2.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing, Year 5 (PDF 125 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading, Year 5 (PDF 344 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, language conventions, Year 5 (PDF 641 KB)

NAPLAN 2015 Year 5 paper test answers (PDF 145 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading magazine, Year 7 (PDF 11.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing prompt – The Best (Years 7 9 only) (PDF 4.2 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy (calculator), Year 7 (PDF 1.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy (non-calculator), Year 7 (PDF 2.2 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading, Year 7 (PDF 334 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing, Year 7 (PDF 120 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, language conventions, Year 7 (PDF 662 KB)

NAPLAN 2015 Year 7 paper test answers (PDF 153 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading magazine, Year 9 (PDF 17.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (calculator) (PDF 1.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (non-calculator) (PDF 1.9 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, writing, Year 9 (PDF 121 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, reading, Year 9 (PDF 336 KB)

- NAPLAN 2015 final test, language conventions, Year 9 (PDF 640 KB)

NAPLAN 2015 Year 9 paper test answers (PDF 155 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, language conventions, Year 3 (PDF 247 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 3 (PDF 4.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading magazine, Year 3 (PDF 35 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading, Year 3 (PDF 290 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing prompt – Change a rule or law (all year levels) (PDF 7.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing, Year 3 (PDF 120 KB)

NAPLAN 2014 Year 3 paper test answers (PDF 147 KB)

Year 5

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading magazine, Year 5 (PDF 10.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing prompt – Change a rule or law (PDF 7 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 5 (PDF 3.4 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing, Year 5 (PDF 121 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading, Year 5 (PDF 357 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, language conventions, Year 5 (PDF 221 KB)

NAPLAN 2014 Year 5 paper test answers (PDF 148 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading magazine, Year 7 (PDF 24.6)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing prompt – Change a rule or law (all year levels) (PDF 7.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (calculator) (PDF 2.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (non-calculator) (PDF 2.4 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing, Year 7 (PDF 119 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading, Year 7 (PDF 340 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, language conventions, Year 7 (PDF 264 KB)

NAPLAN 2014 Year 7 paper test answers (PDF 155 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading magazine, Year 9 (PDF 29.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing prompt – Change a rule or law (PDF 7.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (calculator) (PDF 1.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (non-calculator) (PDF 1.5 MB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, writing, Year 9 (PDF 121 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, reading, Year 9 (PDF 340 KB)

- NAPLAN 2014 final test, language conventions, Year 9 (PDF 245 KB)

NAPLAN 2014 Year 9 paper test answers (PDF 156 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, language conventions, Year 3 (PDF 412 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 3 (with redacted image) (PDF 1.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading magazine, Year 3 (PDF 40.5 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading, Year 3 (PDF 1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing prompt – Hero award (PDF 2.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing, Year 3 (PDF 204 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 Year 3 paper test answers (PDF KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading magazine, Year 5 (redacted image of face page 3) (PDF 12.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 5 (redacted image of face page 8) (PDF 5 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing prompt – Hero Award (PDF 2.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading, Year 5 (PDF 636 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, language conventions, Year 5 (PDF 477 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing, Year 5 (PDF 205 KB)

NAPLAN 2013 Year 5 paper test answers (PDF 149 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading magazine, Year 7 (redacted image of face, page 2) (PDF 20 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (calculator) (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (non-calculator) (PDF 3.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing prompt – Hero Award (all year levels) (PDF 2.8 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading, Year 7 (PDF 700 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing, Year 7 (PDF 204 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, language conventions, Year 7 (PDF 450 KB)

NAPLAN 2013 Year 7 paper test answers (PDF 152 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading magazine, Year 9 (PDF 11.1 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (calculator) (PDF 2.4 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (non-calculator) (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, reading, Year 9 (PDF 697 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, language conventions, Year 9 (PDF 458 KB)

- NAPLAN 2013 final test, writing, Year 9 (PDF 206 KB)

NAPLAN 2013 Year 9 paper test answers (PDF 156 KB)

NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing prompt, all year levels (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, language conventions (PDF 411 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy (redacted image of face page 14) (PDF 3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading magazine (PDF 9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading (PDF 400 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing (PDF 200 KB)

NAPLAN 2012 Year 3 paper test answers (PDF 142 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, language conventions, Year 5 (PDF 543 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy, Year 5 (PDF 2.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading magazine, Year 5 (PDF 10.6 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing prompt (all years) (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing, Year 5 (PDF 200 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading, Year 5 (PDF 382 KB)

NAPLAN 2012 Year 5 paper test answers (PDF 142 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing, Year 7 (PDF 201 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (calculator) (PDF 3.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy, Year 7 (non-calculator) (PDF 2.7 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing prompt (all year levels) (PDF 2.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading magazine, Year 7 (PDF 24.9 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading, Year 7 (PDF 393 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, language conventions, Year 7 (PDF 498 KB)

NAPLAN 2012 Year 7 paper test answers (PDF 149 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading magazine, Year 9 (PDF 13.2)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, reading, Year 9 (PDF 384 KB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (calculator) (PDF 2.7 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, numeracy, Year 9 (non-calculator) (PDF 2.4 MB)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, language conventions, Year 9 (PDF 547)

- NAPLAN 2012 final test, writing, Year 9 (PDF 200 KB)

NAPLAN 2012 Year 9 paper test answers (PDF 149 KB)

NAPLAN special print paper tests

Schools provide special print paper tests to visually impaired students who are unable to access NAPLAN online and who use similar large-print resources as part of their everyday class activities. These paper tests do not simply have their font size enlarged, they are reformatted in accordance with the latest guidelines on printing for students with disability .

Special print paper tests come in the following formats for all years and domains:

- black and white

- large print – font sizes 18 and 24 on A4

- large print – font sizes 18, 24 and 36 on A3.

See below for some examples of the black-and-white and large-print tests that ACARA provides:

- NAPLAN 2016, language conventions test, Year 3, large print (PDF 152 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016, language conventions test, Year 9, black and white (PDF 465 KB)

- NAPLAN 2016, numeracy test, Year 5, black and white (PDF 2.2 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016, reading test, Year 5, large print (PDF 15.3 MB)

- NAPLAN 2016, writing test, Year 7, large print (PDF 4 MB)

Webpage feedback

- Student diversity

- Monitoring reports

- Alternative curriculum recognition

- Read Primary Matters newsletter

- Read DTiF newsletter

- National Report on Schooling in Australia

- Measurement Framework for Schooling in Australia

- National standards for student attendance data reporting

- Data standards manual: Student background characteristics

- Student background data collection for independent schools

- News and media

- ACARA Update

- Work with us

- NAPLAN test window

- Catch-ups and rescheduling sessions

- What's in the tests

- Public demonstration site

- Technical requirements

- Tailored tests

- Keyboard shortcuts

- Research and development

- Adjustments for students with disability

- Disability adjustments scenarios

- Connection to the Australian Curriculum

- National protocols for test administration

- Student participation

- Ramadan and NAPLAN

- For parents and carers

- NAPLAN national results

- Proficiency level descriptions

- NAPLAN - general

- NAPLAN - participation

- NAPLAN - results reports performance

- NAPLAN - writing test

- What's in the tests

National minimum standards

Between 2008 and 2022, students’ NAPLAN results were reported against 10 achievement bands including 5 national minimum standards, which are set out below. Band 1 was the lowest band and band 10 was the highest band. The national minimum standards encompassed one band at each year level and therefore represented a wide range of the typical skills demonstrated by students at this level.

From 2023, NAPLAN results are reported against proficiency standards with 4 proficiency levels for each assessment area at each year level. The NAPLAN measurement scales and time series have also been reset.

Read about the updated NAPLAN reporting .

See NAPLAN student reports 2008–2022 for advice on interpreting older NAPLAN student reports.

National minimum standards 2008–2022

The NAPLAN assessment scale is divided into 10 bands to record student results in the tests. Band 1 is the lowest band and band 10 is the highest band. The national minimum standards encompass one band at each year level and therefore represent a wide range of the typical skills demonstrated by students at this level. For more information, see NAPLAN results 2008–2022 .

Students who are below the national minimum standard have not achieved the learning outcomes expected for their year level. They are at risk of being unable to progress satisfactorily at school without targeted intervention.

Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 | Year 9 |

The skills demonstrated in reading at a particular year level are dependent on the complexity and accessibility of the text. Texts typically increase in difficulty from Year 3 to Year 9.

In Year 3, reading texts tend to have predictable text and sentence structures. Words that may be unfamiliar are explained in the writing or through the accompanying illustrations. Typically, these texts use familiar, everyday language.

At the national minimum standard, Year 3 students generally make some meaning from short texts, such as stories and simple reports, which have some visual support. They make connections between directly stated information and between text and pictures.

When reading simple imaginative texts, students can:

find directly stated information

connect ideas across sentences and paragraphs

interpret ideas, including some expressed in complex sentences

identify a sequence of events

infer the writer’s feelings.

When reading simple information texts, students can:

connect an illustration with ideas in the text

locate a detail in the text

identify the meaning of a word in context

connect ideas within a sentence and across the text

identify the purpose of the text

identify conventions such as lists and those conventions used in a letter.

In Year 5, reading texts may include a range of genres including biographies, autobiographies and persuasive texts such as advertisements. Sentence structure may be varied. Some unfamiliar vocabulary is included, particularly subject-specific words, but its use will be supported by text and illustrations.

At the national minimum standard, Year 5 students generally interpret ideas in simple texts and make connections between ideas that are not stated. They identify the purpose of a text as well as parts of a text such as diagrams and illustrations.

When reading a short narrative, students can:

locate directly stated information

connect and interpret ideas

recognise the relationship between text and illustrations

interpret the nature, behaviour and motivation of characters

identify cause and effect.

When reading an information text, students can:

connect ideas to identify cause and effect

identify the main purpose for the inclusion of specific information, diagrams and illustrations

identify the meaning of a phrase in context

infer the main idea of a paragraph.

When reading a biography or autobiography, students can:

connect ideas

identify the main purpose of the text

make inferences about the impact of an event on the narrator

interpret an idiomatic phrase or the meaning of a simple figurative expression.

When reading a persuasive text such as an advertisement, students can:

identify the main idea of a paragraph or the main message of the text.

In Year 7, reading texts may include a wide range of genres such as arguments and poems. These texts may use technical vocabulary, complex phrases and varied sentence structures. Use of complex punctuation is evident. Texts include simple examples of figurative language.

At the national minimum standard, Year 7 students generally infer the main idea in a text and connect ideas within and between sentences. At this level, students will not only interpret the meaning of words but also the intention of a narrator and the motivation of a character in a narrative, and the writer’s point of view in an argument.

When reading a narrative, students can:

infer the motivation or intention of the narrator or a character

draw together ideas to identify a character's attitude

interpret dialogue to describe a character

connect ideas to infer a character's intention or misconception, or the significance of the character’s actions

interpret the significance of an event for the main character.

When reading a poem, students can:

identify the intention of the narrator.

identify the main idea of a paragraph and the main purpose of the text

link and interpret information across the text

recognise the most likely opinion of a person

use text conventions to locate a detail.

When reading a persuasive text such as an argument, students can:

locate and interpret directly stated information, including the meaning of specific words and expressions

identify the main message of the text

identify the purpose of parts of the text

interpret the main idea of a paragraph

infer the writer's point of view

identify points of agreement in arguments that present different views

identify and interpret conventions used in the text, such as lists, order of online posts and the use of punctuation for effect

identify the common theme in a variety of writers’ opinions.

In Year 9, reading texts include those that describe, explain, instruct, argue and narrate, often in combination. Texts will use less familiar vocabulary, including subject-specific words, and complex sentences that contain detailed information. More extensive use of figurative language is evident.

At the national minimum standard, Year 9 students generally infer the main idea in more complex texts and connect ideas across the text. For example, students at this level identify the tone of an argument and infer the feelings of a character by interpreting descriptive text, figurative language and dialogue in a narrative.

When reading a complex narrative, students can:

locate a directly stated detail

connect ideas across a paragraph or across the text to interpret a description or the motivation of characters

infer the main idea

interpret and evaluate a character’s behaviour and attitude

interpret the reasons for a character's response

connect ideas to interpret figurative language

interpret the effect of a short sentence.

identify the main idea of the poem.

When reading a complex biographical text, students can:

locate a directly stated idea in the text.

When reading a complex information text, students can:

connect ideas in the introduction of the text or in the body of the text and illustrations

identify the main purpose of a text or an element of the text

identify the main idea of a paragraph

identify the purpose of a labelled diagram

identify the intended audience of the text

identify conventions used in a text, such as abbreviations or italics for a foreign word.

connect ideas across the text or in 2 arguments

identify the tone of an argument.

Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 | Year 9 |

The NAPLAN writing task requires students to write in response to a stimulus or prompt. The text of the prompt is read to all students.

A narrative piece of writing is assessed against 10 criteria: audience, text structure, ideas, character and setting, vocabulary, cohesion, paragraphing, sentence structure, punctuation and spelling. Each criterion has a different number of broad categories based on identifiable developmental stages.

A persuasive piece of writing is also assessed against 10 criteria, many of which are very similar to those assessed in students’ narrative writing. The 10 criteria against which persuasive writing is assessed are: audience, text structure, ideas, persuasive devices, vocabulary, cohesion, paragraphing, sentence structure, punctuation and spelling.

The text type will be revealed on the day of assessment. Students will be asked to write a narrative or persuasive response to the writing prompt.

Comparability of skills demonstrated in the writing and conventions of language assessments

Although there is some overlap in the skills assessed in the writing and conventions of language assessments (for example, both assess spelling and aspects of grammar and punctuation), a student’s placement on the band scales for the 2 tests may not match, due to the difference in the nature of the assessments.

Spelling results, in particular, may not be comparable across the 2 assessment tasks. For the writing task, spelling is scored in the context of writing and depends on the words the students choose to include in their responses to the stimulus words and the level of correctness then demonstrated. In contrast, the conventions of language assessment requires students to spell words that have been chosen to demonstrate specific spelling skills.

In the writing tests, the spelling criterion consists of 6 broad categories to measure the range of performance demonstrated from Year 3 through to Year 9.

Using the broad categories for assessing spelling in the writing tests, students at the national minimum standard may demonstrate similar skills in Years 5, 7 and 9.

This does not mean that students that achieve results at the national minimum standard for the writing tests fail to make progress from Years 5 to 9. Rather, it reflects a continuing tendency among students at the national minimum standard to spell difficult or challenging words (as defined in the writing test criteria) incorrectly. The same applies to punctuation and grammar. The use of a particular punctuation mark or sentence structure may not be applicable to the writing task and so will not necessarily be used by the student in his or her own writing; however, when given a specific item in a different context, such as determining the correct use of apostrophes, quotation marks and dependent clauses in the conventions of language test, students may demonstrate competency.

At the national minimum standard, Year 3 students responding to a narrative task generally write a text consisting of a few simple ideas that show audience awareness by using common story elements; for example, using a simple title, or beginning with Once upon a time. Students name the characters and setting, and the ideas and vocabulary used are generally very simple. Students typically choose mostly simple verbs, adverbs, adjectives and nouns. They may include a few examples of precise words and produce some correctly formed sentences. Students use some capital letters and full stops correctly and correctly spell most of the simple words they choose to use in their writing.

When responding to the persuasive task, students at the national minimum standard for Year 3 generally write a text consisting of a few simple ideas that show audience awareness by providing some simple information about the topic. Simple persuasive devices such as opinions and reasons are used in an attempt to convince a reader. Students typically choose mostly simple verbs, adverbs, adjectives and nouns. They may include a few examples of precise, topic specific words and produce some correctly formed sentences. Students use some capital letters and full stops correctly and correctly spell most of the simple words they choose to use in their writing.

At the national minimum standard, Year 5 students generally write a story with a few related ideas which are not well elaborated, and attempt to create a clear context by providing brief descriptions of the characters and/or setting. The vocabulary used is usually simple.

When responding to the persuasive task, these students at the national minimum standard for Year 5 generally write a text that attempts to create a position on a topic by providing a context and some points of argument with some simple elaboration. They attempt a small range of simple persuasive devices and use some topic specific vocabulary.

When writing to either task, students typically correctly structure most simple and compound sentences and generally use some correct links between sentences. Most referring words are accurate. Students typically correctly punctuate some sentences with both capital letters and full stops. They may demonstrate correct use of capitals for names and some other punctuation.

Students correctly spell most simple and common words.

At the national minimum standard, Year 7 students generally structure a story to include a beginning and a complication, although the conclusion may be weak or simple, or a persuasive essay that has an indefinable introduction, body and conclusion, although the introduction and/or the conclusion may be weak or simple.

Students typically include sufficient information for the story or essay to be easily understood by the reader and there is usually development and elaboration of ideas which all relate coherently to a central storyline or the position taken on a topic. They use a small range of simple persuasive devices with some success and use some topic specific vocabulary.

Some precision is evident in the vocabulary use although words are not all used successfully. Students correctly structure most simple and compound sentences and some complex sentences and correctly punctuate some sentences with both capital letters and full stops. They may demonstrate correct use of some other punctuation, for example quotation marks for direct speech or commas for phrasing.

At the national minimum standard, Year 9 students generally write stories with a beginning, complication and ending and can organise a story into paragraphs that focus on one idea or a group of related ideas. Students attempt to develop context by providing some elaboration, detail and description of characters and settings.

At the national minimum standard, Year 9 students generally write persuasive essays that contain an introduction, a body and a conclusion in which paragraphs are used to organise related ideas. Students attempt to develop their position on a topic with some elaboration and detail about the topic and use a range of persuasive devices with some success.

Students typically use accurate words or groups of words when describing events and ideas although there are typically errors evident in sentence construction. The writing often uses a small range of connectives and conjunctions to link text sections and sentences correctly.

Students punctuate most sentences correctly with capitals, full stops, exclamation marks and question marks. Students correctly use more complex punctuation marks some of the time.

Conventions of language – spelling

Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 | Year 9

In spelling, Year 3 students at the national minimum standard generally identify and correct errors in frequently used one-syllable words and some frequently used 2-syllable words with double letters.

Students can spell and correct identified errors in:

frequently used one-syllable words

frequently used 2-syllable words with regular spelling patterns.

In spelling, Year 5 students at the national minimum standard generally identify and correct errors in most one- and 2-syllable words with regular spelling patterns and some less frequently used words with double letters.

Students can spell and identify and correct errors in:

high frequency compound words

less frequently used multi-syllable words with double letters.

Students can identify and correct errors in:

frequently used one-syllable long vowel words

frequently used one-syllable words with irregular spelling patterns

common one-syllable verbs with tense markers

high frequency 2-syllable words.

In spelling, Year 7 students at the national minimum standard generally identify and correct errors in most frequently used multi-syllable words with regular spelling patterns and some words with silent letters.

one-syllable ‘soft c’ words

one-syllable words ending with silent letters

one-syllable words with irregular spelling patterns

frequently used compound words with irregular spelling patterns.

Students can correct identified errors in:

less frequently used one-syllable words

less frequently used compound words with regular spelling patterns

two-syllable words with irregular spelling patterns

less frequently used multi-syllable adverbs.

In spelling, Year 9 students at the national minimum standard generally identify and correct errors in most multi-syllable words with regular spelling patterns and some less frequently used words with irregular spelling patterns.

multi-syllable soft 'c' words

multi-syllable words with regular spelling patterns.

less frequently used one-syllable words with double or r-controlled vowels

less frequently used 2-syllable words

multi-syllable words with the suffix ‘ance’.

Conventions of language – grammar and punctuation

In grammar and punctuation, Year 3 students at the national minimum standard generally identify features of a simple sentence. They identify some common grammatical conventions such as the correct use of past and present tense and the use of pronouns to replace nouns in sentences. They typically recognise the correct use of punctuation in written English, such as capitalisation for sentence beginnings and proper nouns.

In grammar students can:

identify the correct preposition required to complete a sentence

identify the correct pronoun required to complete a sentence

identify the correct adverb of time required to complete a sentence

identify the correct form of a participle required to complete a sentence.

In punctuation students can:

identify the correct location of a full stop

identify proper nouns that require capitalisation.

In grammar and punctuation, Year 5 students at the national minimum standard generally identify common grammatical conventions such as the correct use of conjunctions and verb forms. They typically recognise the correct use of punctuation in written English, such as the use of question marks and speech marks for direct speech.

identify the correct conjunction required to join a pair of simple sentences

identify the correct form of the verb required to complete a sentence

identify which adverb in a sentence describes how an action took place

identify the correct plural pronoun required to complete a sentence.

- identify direct speech that uses capital letters, question marks and speech marks.

In grammar and punctuation, Year 7 students at the national minimum standard generally identify common grammatical conventions such as the correct use of relative pronouns and clauses. They typically recognise the correct use of punctuation in written English, such as the use of apostrophes for possession and of commas to separate nouns in lists.

identify the correct form of the verb required to complete a complex sentence

identify the correct personal pronoun required to complete a sentence

identify correct subject–verb agreement in a sentence

identify the phrase required to complete a sentence.

- locate a comma to separate items in a list.

In grammar and punctuation, Year 9 students at the national minimum standard generally identify in which tense a short passage is written and correctly use comparative adjectives. They typically recognise the correct use of punctuation in written English, such as the correct form of contractions, and can identify the purpose of italics and dashes in sentences.

identify the tense of a short passage

identify the correct form of a comparative adjective in a sentence

identify the word that functions as a verb in a sentence.

identify the purpose of italics in a sentence

locate commas in a sentence to emphasise a clause

recognise that colons can be used to introduce lists.

Year 3 | Year 5 | Year 7 | Year 9 |

Year 3: Number

In number, students at the national minimum standard at Year 3 generally recognise, compare and order whole numbers with up to 3 digits, recognising standard representations and different ways of partitioning one- and 2-digit numbers.

Students meeting the national minimum standard have typically developed computational fluency with addition and subtraction of small whole numbers. They generally add and subtract 2-digit numbers, add the value of coins and use partitioning and grouping to solve simple problems.

Whole numbers

Students read, recognise and count with whole numbers up to 3 digits. For example, students can generally:

recognise 3-digit numbers in words and symbols

recognise odd and even numbers

make given numbers larger or smaller by 1, by 10 or by 100

count forwards and backwards by 1s, 2s, 5s and 10s

skip count by 2s, 5s and 10s.

Students compare and order whole 2-digit numbers. They use place value knowledge up to the hundreds to interpret different representations of whole numbers. For example, students can generally:

compare and order 2-digit numbers

partition one- and 2-digit numbers in different ways

recognise different standard representations of numbers in hundreds, tens and ones.

Fractions and decimals

Students halve small amounts and recognise a half and a quarter in familiar contexts. They start to interpret decimals in a money context. For example, students can generally:

recognise a half and find half of discrete quantities or amounts

find half of a symmetrical object

interpret key decimals in money contexts as dollars and cents.

Calculating

Students recall basic number facts with small numbers and use them to complete addition and subtraction calculations. They recognise situations involving making equal groups. For example, students can generally:

recall and use addition and subtraction facts to 20

use partitioning to assist addition and subtraction of one- and 2-digit numbers

interpret repeated addition as multiplication

form equal groups of objects, given a visual support

count and record the total value of coins in dollars and cents (up to $5).

Applying number

Students generally identify situations and problems that require addition or subtraction with small numbers. For example, students can generally:

use addition or subtraction to solve routine problems

start to link the correct mathematical terms to the relevant operations (e.g. sum, difference, equal groups or equal sharing)

recognise situations involving a single operation.

Year 3: Space

In space, students at the national minimum standard generally recognise basic 2D shapes and their properties such as length of sides, and size of angles or areas. They typically recognise and visualise familiar 2D shapes such as triangles, squares and circles, and common 3D objects such as cubes, prisms, cylinders and cones. They also recognise standard 2D representations of common 3D objects, line of symmetry and single turns. They generally follow simple directions to find locations on grids and informal maps.

Classification and properties of shapes

Students typically recognise and describe familiar 2D shapes and common 3D objects. They identify them within sketches, diagrams or photographs. For example, students can generally:

identify familiar 2D shapes such as squares, rectangles, triangles and circles

identify families of common 3D objects such as prisms, cones, cylinders

recognise models and 2D diagrams of common 3D objects

differentiate between 2D shapes and 3D objects

recognise angles in shapes, objects and in turns

visualise simple objects made of cubes.

Transformations

Students recognise line of symmetry in simple 2D shapes. They recognise simple transformations of familiar shapes. For example, students can generally:

use folding or other techniques to identify a line of symmetry

recognise the effect of a single flip, slide or turn

use symmetry or transformations to continue patterns.

Location and movement

Students identify pathways and specific locations on simple informal maps, grids and plans. For example, students can generally:

identify the key features of simple informal maps, grids and plans

use alpha-numeric coordinates to locate position on simple grids

interpret informal maps or grids of familiar environments

follow directions for moving from one point to another using the language of turns.

Year 3: Algebra, function and pattern

In algebra, function and pattern, students at the national minimum standard have pre-algebraic skills and concepts that relate mostly to number sense. They relate known facts to simple number sentences and number patterns.

Students at the national minimum standard can typically complete addition or subtraction number sentences involving small numbers correctly. They can model familiar situations with addition or subtraction number sentences. Students can identify relationships between consecutive terms in number patterns with constant addition or subtraction of small numbers.

Equivalence

Students at the national minimum standard level recognise equivalences in a variety of ways. For example, students can generally:

recognise a familiar correspondence between 2 sets of objects

order objects according to a common criterion

follow a short sequence of instructions

recognise an equivalent form of a number or a simple expression

identify the same attribute in measurement or spatial contexts.

Students identify and continue patterns and sequences that show increase, decrease and repetition. For example, students can generally:

recognise and continue a number pattern with a constant addition or subtraction of a small whole number

identify the change between consecutive terms in a simple pattern.

Year 3: Measurement, chance and data

In measurement, chance and data, students at the national minimum standard at Year 3 are generally able to visually compare by length ordered objects and to choose the instrument that measures length. Students can also calculate areas or volumes by counting whole units. They are able to read and tell key times on digital and analog clocks.

Students meeting the national minimum standard record data using one-to-one correspondence and read data presented in simple tables, 2-way tables and pictographs with one-to-one or one-to-two correspondence.

Students identify and distinguish the attributes of shapes and objects with respect to length, area, volume and mass. They start to use informal units to compare, measure and order a set of objects according to a specified attribute. For example, students can generally:

understand the language used to describe length in familiar contexts

measure length using informal units

compare and order objects according to a specific attribute – length, capacity or area.

Students choose and use standard metric units such as metre, centimetre, litre and kilogram. They estimate and compare measurements, and choose appropriate instruments to measure to the nearest unit. For example, students can generally:

decide whether containers hold less, about the same or more than a litre

use informal units to estimate length, volume and mass of familiar objects

use some relationships between standard units, e.g. 1h = 60 min, 1m = 100 cm

read whole-number scales with all calibrations shown.

Students read times and dates using clocks and calendars. For example, students can generally:

read half and quarter hour times on analog clocks

read time on digital clocks in hours and minutes

recognise the time half an hour before or after a given time.

Students read data present in tallies and simple tables. They make statements about familiar events that are likely or unlikely to happen. For example, students can generally:

read and interpret data presented in lists, tallies, tables, pictographs (1:1 or 1:2 correspondence) or simple column graphs and 2-way tables

make qualitative judgements about data in frequency tables

identify variation of data in tables and graphs.

Year 3: Working mathematically

In working mathematically, the emphasis is on the processes rather than strand-specific content. In working mathematically, students at the national minimum standard at Year 3 can generally recognise and respond to routine questions addressing known facts in familiar contexts.

Students recall basic facts, terms, procedures or properties of numbers and recognise simple shapes in familiar contexts. For example, students can generally:

recall names of familiar shapes, symbols and notations

recognise images of familiar 2D shapes and 3D objects, and equivalent forms of whole numbers and simple number sentences

calculate with small numbers and coins

retrieve information from simple tables, graphs and pictographs

group shapes, objects or numbers according to a common attribute or property

compare shapes and objects by lengths, areas and masses.

Students’ ability to apply known problem-solving strategies and procedures to solve routine problems is essential for their progress and for their cognitive development. For example, students can generally:

select the correct operation or a number sentence for a given situation

compare information presented in familiar forms

interpret simple diagrams and tables

construct number sentences by using known facts

follow simple instructions

solve routine problems involving one or 2 steps.

Year 5: Number

In number, students at the national minimum standard at Year 5 typically understand and recognise relationships between numbers and perform simple calculations with the 4 operations.

Students meeting the national minimum standard have developed number sense of whole numbers with up to 3 digits, and use the understanding of the 4 operations to solve routine problems in familiar contexts. They generally interpret the symbols for common fractions and decimals, and they add and subtract decimals with the same number of decimal places.

Students recognise, read, compare, and order whole numbers up to 4 digits. For example, students can generally:

recognise different representations of a whole number

use place value to compare, order or locate numbers on a number line

multiply or divide by 10 or 100 in place-value contexts.

Students recognise equivalent forms of common fractions and link unit fractions to familiar situations. For example, students can generally:

identify and use equal partitions, and name the parts

recognise different representations of simple fractions

compare decimals with the same number of decimal places

use common unit fractions to solve routine problems.

Students recall addition and subtraction facts with one- and 2-digit numbers and link to routine multiplication and related division facts. They add and subtract whole numbers to hundreds and decimal fractions with the same number of decimal places, and multiply one-digit numbers. For example, students can generally:

recall addition and subtraction facts of small numbers

identify and use known number facts to assist calculations

multiply small whole numbers

complete operations with coins and record amounts of money in decimals

add or subtract common fractions with the same denominators.

Students recognise situations that require the use of addition, subtraction, multiplication or division. For example, students can generally:

recognise the use of a single operation in familiar contexts

use addition or subtraction to solve routine problems

solve routine problems involving a single operation

add or subtract decimals in money/measurement contexts

estimate the value of simple computations

link the 4 operations to routine situations.

Year 5: Space

In space, students at the national minimum standard at Year 5 identify familiar 2D shapes and recognise simple representations of common 3D objects that illustrate the essential features.

They generally identify symmetrical and non-symmetrical shapes and recognise spatial patterns and tessellations. They interpret conventions used in simple maps, grids and plans.

Students identify common properties of 2D shapes or 3D objects and use the correct mathematical terms to describe them. For example, students can generally:

identify features of common shapes and objects

summarise features of groups of common shapes or objects

interpret the spatial language used in describing common shapes and objects.

Students recognise common shapes and objects presented in drawings and diagrams. For example, students can generally:

interpret drawings of shapes or objects that reflect the size and significant features

recognise different orientations of a shape or different perspectives of an object

identify shapes or objects with given features

visualise simple objects made of unit cubes.

Students identify shapes and designs that are symmetrical or asymmetrical. They recognise a single transformation used in patterns or arrangements including tessellations. For example, students can generally:

identify symmetrical shapes and designs

identify the result of a single transformation of a simple shape

identify common shapes that tessellate.

Students interpret key symbols and conventions used in maps, grids and plans. For example, students can generally:

interpret the symbols for the key compass directions

link the 4 major compass points to a quarter, half, three-quarters and a full turn

interpret and follow directions.

Year 5: Algebra, function and pattern

In algebra, function and pattern, students at the national minimum standard at Year 5 complete number sentences with whole numbers involving addition or subtraction.

They generally recognise number patterns involving one operation and they select the correct rule used in a given pattern.

Relationships

Students recognise number relationships in familiar contexts. For example, students can generally:

identify a familiar criterion used in arranging and sorting shapes or objects

recognise and describe simple relationships

use simple tables or graphs to predict change.

Students make links between arithmetic operations based on familiar properties. For example, students can generally:

make links between routine multiplication and division facts

use known facts to work out related calculations

make changes to computations that maintain equivalence.

Students solve simple number sentences arising from familiar situations. For example, students can generally:

recognise the number sentence that matches a familiar situation

recognise equivalence in familiar contexts (e.g. balance scales)

solve one-step number sentences involving simple calculations.

Students recognise and describe numerical and spatial patterns. For example, students can generally:

recognise different representations of the same pattern

recognise a single relationship between consecutive terms

continue number patterns requiring one-step calculations.

Year 5: Measurement, chance and data

In measurement, chance and data, students at the national minimum standard at Year 5 use standard units such as centimetres and metres to measure lengths, grams and kilograms to measure mass, and litres to measure capacity.

Students meeting the national minimum standard identify the possible outcomes for familiar events and make predictions. They read data in tables and simple graphs, and check simple statements.

Students compare, measure, and order lengths, areas, volumes, angles and masses selecting and using suitable standard units and appropriate measuring instruments and scales. For example, students can generally:

choose the appropriate attribute to compare objects

measure and compare areas of shapes on grids counting whole and half units

measure and compare volumes counting informal units

arrange measurements in order of magnitude

make reasonable estimates of a quantity using known measures.

Students recognise different recordings of metric measures. They understand relationships between perimeters of familiar shapes and the lengths of their sides. For example, students can generally:

read measures from simple whole-unit scales.

Students read times on digital clocks and key times on analogue clocks, and they calculate durations of specific events. Students use calendars and simple timetables and timelines to sequence events. For example, students can generally:

recognise key times on analogue clocks and read times on digital clocks

identify equivalent forms of saying and recording a key time

use calendars and timetables to seek specific information.

Students identify the possible outcomes for familiar events and predict their comparative likelihood. For example, students can generally:

make predictions based on data.

Students read data presented in tables, bar graphs and simple 2-way tables and make simple interpretations. For example, students can generally:

read tabular and graphical displays involving simple whole-number scales

check statements or predictions against data

identify variation within a set of data.

Year 5: Working mathematically

In working mathematically, the emphasis is on the processes rather than strand-specific content. In working mathematically, students at the national minimum standard at Year 5 can generally recognise and respond to routine questions involving known facts in familiar contexts.

Students at the national minimum standard recall number facts, terms, properties of common shapes and recognise common objects in simple diagrams. For example, students can generally:

recall properties of numbers, common fractions, measures, familiar shapes and objects

recognise diagrams of common shapes and objects, equivalent forms of whole numbers, common fractions, decimals and simple expressions

calculate with whole numbers, common fractions with the same denominators and decimals

read and interpret information from whole-number scales, tables, simple graphs and pictographs (one-to-one or one-to-two correspondence)

measure length, area, mass and capacity using standard units

group shapes, objects or numbers according to a familiar attribute.

Students at the national minimum standard apply simple strategies to solve routine problems. For example, students can generally:

select the correct operation or the missing number in a number sentence

construct and complete number sentence involving one operation

interpret a situation presented in diagrams, tables or simple graphs

follow simple instructions and procedures

analyse patterns to identify the rule

solve routine problems in familiar contexts.

Year 7: Number

In number, students at the national minimum standard at Year 7 identify, represent, compare and order integers and common fractions using a variety of methods. They perform calculations using all four operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division), both with and without the access to a calculator.

Students meeting the national minimum standard can solve routine problems involving simple rates and proportions, and they can use strategies to form reasonable estimations.

Rational numbers

Students represent, describe and order integers, common fractions and decimals. For example, students can generally:

order and locate integers, mixed numbers or common fractions on a suitably scaled number line

recall decimal equivalence of common fractions

recognise different representations of a common fraction.

Students use mental and written methods with addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. They use a calculator to assist with more complex calculations.

For example, students can generally:

solve simple problems in familiar contexts involving addition or subtraction of integers

use knowledge of place value to multiply and divide decimals by 10 and 100

perform calculations involving key percentages or addition and subtraction of decimal numbers with the same number of decimal places.

Students form estimates and make approximations. They interpret and solve practical problems using appropriate operations. For example, students can generally:

round 7-digit numbers to the nearest thousand

solve simple rate problems involving time and distance

select an appropriate approximation to a calculation involving money

interpret and solve practical problems involving division, with access to a calculator.

Year 7: Space

In space students at the national minimum standard at Year 7 identify, describe and classify common 2D shapes and 3D objects. They recognise lines of symmetry of irregular shapes.

Students, meeting the national minimum standard, can read and interpret maps and plans and they use compass points to follow directions and find locations.

Students identify, describe and classify 2D shapes and 3D objects. For example, students can generally:

identify common 2D shapes that have specific properties.

Students recognise symmetry and congruence in 2D shapes. They visualise simple translations of objects in space. For example, students can generally:

identify an increase or a decrease of a shape or object

identify lines of symmetry in regular and irregular shapes

visualise possible results of joining objects made from cubes.

Students interpret maps and plans using compass points and directions. For example, students can generally:

locate and describe positions on maps or plans using the major compass points

interpret whole-number scales to estimate real distance between objects