- How it works

How to Write the Dissertation Findings or Results – Steps & Tips

Published by Grace Graffin at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On June 11, 2024

Each part of the dissertation is unique, and some general and specific rules must be followed. The dissertation’s findings section presents the key results of your research without interpreting their meaning .

Theoretically, this is an exciting section of a dissertation because it involves writing what you have observed and found. However, it can be a little tricky if there is too much information to confuse the readers.

The goal is to include only the essential and relevant findings in this section. The results must be presented in an orderly sequence to provide clarity to the readers.

This section of the dissertation should be easy for the readers to follow, so you should avoid going into a lengthy debate over the interpretation of the results.

It is vitally important to focus only on clear and precise observations. The findings chapter of the dissertation is theoretically the easiest to write.

It includes statistical analysis and a brief write-up about whether or not the results emerging from the analysis are significant. This segment should be written in the past sentence as you describe what you have done in the past.

This article will provide detailed information about how to write the findings of a dissertation .

When to Write Dissertation Findings Chapter

As soon as you have gathered and analysed your data, you can start to write up the findings chapter of your dissertation paper. Remember that it is your chance to report the most notable findings of your research work and relate them to the research hypothesis or research questions set out in the introduction chapter of the dissertation .

You will be required to separately report your study’s findings before moving on to the discussion chapter if your dissertation is based on the collection of primary data or experimental work.

However, you may not be required to have an independent findings chapter if your dissertation is purely descriptive and focuses on the analysis of case studies or interpretation of texts.

- Always report the findings of your research in the past tense.

- The dissertation findings chapter varies from one project to another, depending on the data collected and analyzed.

- Avoid reporting results that are not relevant to your research questions or research hypothesis.

Does your Dissertation Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of the Dissertation strong.

1. Reporting Quantitative Findings

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or questions you intend to address as part of your dissertation project.

Report the relevant findings for each research question or hypothesis, focusing on how you analyzed them.

Analysis of your findings will help you determine how they relate to the different research questions and whether they support the hypothesis you formulated.

While you must highlight meaningful relationships, variances, and tendencies, it is important not to guess their interpretations and implications because this is something to save for the discussion and conclusion chapters.

Any findings not directly relevant to your research questions or explanations concerning the data collection process should be added to the dissertation paper’s appendix section.

Use of Figures and Tables in Dissertation Findings

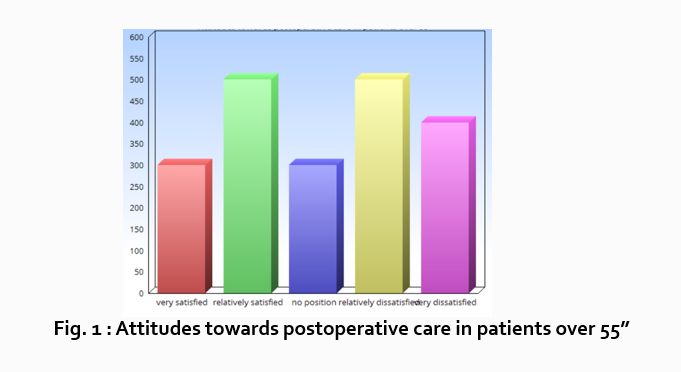

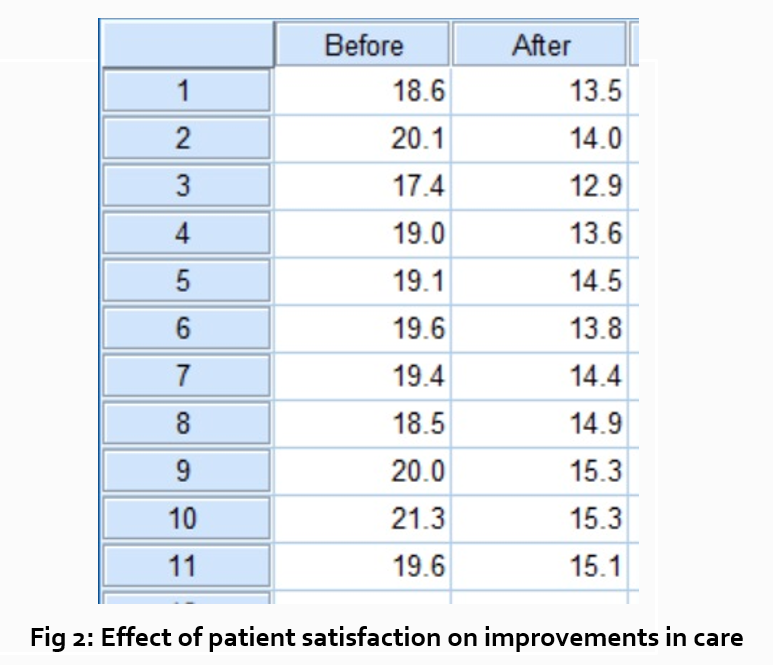

Suppose your dissertation is based on quantitative research. In that case, it is important to include charts, graphs, tables, and other visual elements to help your readers understand the emerging trends and relationships in your findings.

Repeating information will give the impression that you are short on ideas. Refer to all charts, illustrations, and tables in your writing but avoid recurrence.

The text should be used only to elaborate and summarize certain parts of your results. On the other hand, illustrations and tables are used to present multifaceted data.

It is recommended to give descriptive labels and captions to all illustrations used so the readers can figure out what each refers to.

How to Report Quantitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report quantitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

Two hundred seventeen participants completed both the pretest and post-test and a Pairwise T-test was used for the analysis. The quantitative data analysis reveals a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the pretest and posttest scales from the Teachers Discovering Computers course. The pretest mean was 29.00 with a standard deviation of 7.65, while the posttest mean was 26.50 with a standard deviation of 9.74 (Table 1). These results yield a significance level of .000, indicating a strong treatment effect (see Table 3). With the correlation between the scores being .448, the little relationship is seen between the pretest and posttest scores (Table 2). This leads the researcher to conclude that the impact of the course on the educators’ perception and integration of technology into the curriculum is dramatic.

Paired Samples

| Mean | N | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESCORE | 29.00 | 217 | 7.65 | .519 | |

| PSTSCORE | 26.00 | 217 | 9.74 | .661 |

Paired Samples Correlation

| N | Correlation | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESCORE & PSTSCORE | 217 | .448 | .000 |

Paired Samples Test

| Paired Differences | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Pair 1 | PRESCORE-PSTSCORE | 2.50 | 9.31 | .632 | 1.26 | 3.75 | 3.967 | 216 | .000 |

Also Read: How to Write the Abstract for the Dissertation.

2. Reporting Qualitative Findings

A notable issue with reporting qualitative findings is that not all results directly relate to your research questions or hypothesis.

The best way to present the results of qualitative research is to frame your findings around the most critical areas or themes you obtained after you examined the data.

In-depth data analysis will help you observe what the data shows for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be mentioned to the readers.

Additional information not directly relevant to your research can be included in the appendix .

How to Report Qualitative Findings

Here is an example of how to report qualitative results in your dissertation findings chapter;

The last question of the interview focused on the need for improvement in Thai ready-to-eat products and the industry at large, emphasizing the need for enhancement in the current products being offered in the market. When asked if there was any particular need for Thai ready-to-eat meals to be improved and how to improve them in case of ‘yes,’ the males replied mainly by saying that the current products need improvement in terms of the use of healthier raw materials and preservatives or additives. There was an agreement amongst all males concerning the need to improve the industry for ready-to-eat meals and the use of more healthy items to prepare such meals. The females were also of the opinion that the fast-food items needed to be improved in the sense that more healthy raw materials such as vegetable oil and unsaturated fats, including whole-wheat products, to overcome risks associated with trans fat leading to obesity and hypertension should be used for the production of RTE products. The frozen RTE meals and packaged snacks included many preservatives and chemical-based flavouring enhancers that harmed human health and needed to be reduced. The industry is said to be aware of this fact and should try to produce RTE products that benefit the community in terms of healthy consumption.

Looking for dissertation help?

Research prospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across a variety of disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

What to Avoid in Dissertation Findings Chapter

- Avoid using interpretive and subjective phrases and terms such as “confirms,” “reveals,” “suggests,” or “validates.” These terms are more suitable for the discussion chapter , where you will be expected to interpret the results in detail.

- Only briefly explain findings in relation to the key themes, hypothesis, and research questions. You don’t want to write a detailed subjective explanation for any research questions at this stage.

The Do’s of Writing the Findings or Results Section

- Ensure you are not presenting results from other research studies in your findings.

- Observe whether or not your hypothesis is tested or research questions answered.

- Illustrations and tables present data and are labelled to help your readers understand what they relate to.

- Use software such as Excel, STATA, and SPSS to analyse results and important trends.

Essential Guidelines on How to Write Dissertation Findings

The dissertation findings chapter should provide the context for understanding the results. The research problem should be repeated, and the research goals should be stated briefly.

This approach helps to gain the reader’s attention toward the research problem. The first step towards writing the findings is identifying which results will be presented in this section.

The results relevant to the questions must be presented, considering whether the results support the hypothesis. You do not need to include every result in the findings section. The next step is ensuring the data can be appropriately organized and accurate.

You will need to have a basic idea about writing the findings of a dissertation because this will provide you with the knowledge to arrange the data chronologically.

Start each paragraph by writing about the most important results and concluding the section with the most negligible actual results.

A short paragraph can conclude the findings section, summarising the findings so readers will remember as they transition to the next chapter. This is essential if findings are unexpected or unfamiliar or impact the study.

Our writers can help you with all parts of your dissertation, including statistical analysis of your results . To obtain free non-binding quotes, please complete our online quote form here .

Be Impartial in your Writing

When crafting your findings, knowing how you will organize the work is important. The findings are the story that needs to be told in response to the research questions that have been answered.

Therefore, the story needs to be organized to make sense to you and the reader. The findings must be compelling and responsive to be linked to the research questions being answered.

Always ensure that the size and direction of any changes, including percentage change, can be mentioned in the section. The details of p values or confidence intervals and limits should be included.

The findings sections only have the relevant parts of the primary evidence mentioned. Still, it is a good practice to include all the primary evidence in an appendix that can be referred to later.

The results should always be written neutrally without speculation or implication. The statement of the results mustn’t have any form of evaluation or interpretation.

Negative results should be added in the findings section because they validate the results and provide high neutrality levels.

The length of the dissertation findings chapter is an important question that must be addressed. It should be noted that the length of the section is directly related to the total word count of your dissertation paper.

The writer should use their discretion in deciding the length of the findings section or refer to the dissertation handbook or structure guidelines.

It should neither belong nor be short nor concise and comprehensive to highlight the reader’s main findings.

Ethically, you should be confident in the findings and provide counter-evidence. Anything that does not have sufficient evidence should be discarded. The findings should respond to the problem presented and provide a solution to those questions.

Structure of the Findings Chapter

The chapter should use appropriate words and phrases to present the results to the readers. Logical sentences should be used, while paragraphs should be linked to produce cohesive work.

You must ensure all the significant results have been added in the section. Recheck after completing the section to ensure no mistakes have been made.

The structure of the findings section is something you may have to be sure of primarily because it will provide the basis for your research work and ensure that the discussions section can be written clearly and proficiently.

One way to arrange the results is to provide a brief synopsis and then explain the essential findings. However, there should be no speculation or explanation of the results, as this will be done in the discussion section.

Another way to arrange the section is to present and explain a result. This can be done for all the results while the section is concluded with an overall synopsis.

This is the preferred method when you are writing more extended dissertations. It can be helpful when multiple results are equally significant. A brief conclusion should be written to link all the results and transition to the discussion section.

Numerous data analysis dissertation examples are available on the Internet, which will help you improve your understanding of writing the dissertation’s findings.

Problems to Avoid When Writing Dissertation Findings

One of the problems to avoid while writing the dissertation findings is reporting background information or explaining the findings. This should be done in the introduction section .

You can always revise the introduction chapter based on the data you have collected if that seems an appropriate thing to do.

Raw data or intermediate calculations should not be added in the findings section. Always ask your professor if raw data needs to be included.

If the data is to be included, then use an appendix or a set of appendices referred to in the text of the findings chapter.

Do not use vague or non-specific phrases in the findings section. It is important to be factual and concise for the reader’s benefit.

The findings section presents the crucial data collected during the research process. It should be presented concisely and clearly to the reader. There should be no interpretation, speculation, or analysis of the data.

The significant results should be categorized systematically with the text used with charts, figures, and tables. Furthermore, avoiding using vague and non-specific words in this section is essential.

It is essential to label the tables and visual material properly. You should also check and proofread the section to avoid mistakes.

The dissertation findings chapter is a critical part of your overall dissertation paper. If you struggle with presenting your results and statistical analysis, our expert dissertation writers can help you get things right. Whether you need help with the entire dissertation paper or individual chapters, our dissertation experts can provide customized dissertation support .

FAQs About Findings of a Dissertation

How do i report quantitative findings.

The best way to present your quantitative findings is to structure them around the research hypothesis or research questions you intended to address as part of your dissertation project. Report the relevant findings for each of the research questions or hypotheses, focusing on how you analyzed them.

How do I report qualitative findings?

The best way to present the qualitative research results is to frame your findings around the most important areas or themes that you obtained after examining the data.

An in-depth analysis of the data will help you observe what the data is showing for each theme. Any developments, relationships, patterns, and independent responses that are directly relevant to your research question or hypothesis should be clearly mentioned for the readers.

Can I use interpretive phrases like ‘it confirms’ in the finding chapter?

No, It is highly advisable to avoid using interpretive and subjective phrases in the finding chapter. These terms are more suitable for the discussion chapter , where you will be expected to provide your interpretation of the results in detail.

Can I report the results from other research papers in my findings chapter?

NO, you must not be presenting results from other research studies in your findings.

You May Also Like

Do dissertations scare you? Struggling with writing a flawless dissertation? Well, congratulations, you have landed in the perfect place. In this blog, we will take you through the detailed process of writing a dissertation. Sounds fun? We thought so!

This article is a step-by-step guide to how to write statement of a problem in research. The research problem will be half-solved by defining it correctly.

Dissertation discussion is where you explore the relevance and significance of results. Here are guidelines to help you write the perfect discussion chapter.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Research Findings – Objectives , Importance and Techniques

Published 16 October, 2023

Findings are basically the key outcome of the investigation. It is basically a key fact which you can discover during an investigation. Research findings are facts and phrases, observations, and experimental data resulting from research.

It’s important to note here that “finding” does not always mean “factual information” because conductive research relies on results and implications rather than measurable facts.

For example, A researcher is conducting research for measuring the extent up to which globalization impacts the business activities of firms. The findings of the research reveal that there has been a great increase in the profitability of companies after globalization. An important fact which researcher has discovered is that it is globalization which has enabled firms to expand their business operations at the international level.

Objectives of finding section in the research paper

- The main objective of the finding section in a research paper is to display or showcase the outcome in a logical manner by utilizing, tables, graphs, and charts.

- The objective of research findings is to provide a holistic view of the latest research findings in related areas.

- Research findings also aim at providing novel concepts and innovative findings that can be utilized for further research, development of new products or services, implementation of better business strategies, etc.

For example, an academic paper on “the use of product life cycle theory with reference to various product categories” will not only discuss different dimensions of the product life cycle but would also present a detailed case study analysis on how the concept was applied using several contemporary case studies from diverse industries.

Importance of findings in the research paper

The finding section in the research paper has great importance as

- It is the section in a research paper or dissertation that will help you in developing an in-depth understanding of the research problems .

- This is the section where the theories where you can accept or reject theories.

- The findings section helps you in demonstrating the significance of the problem on which you are performing research.

- It is through analysis of the finding section you can easily address the correlational research between the different types of variables in the study.

How to Write Research Findings?

Every research project is unique, so it is very much important for the researcher to utilize different strategies for writing different sections of the research paper. 5 steps that you need to follow for writing the research findings section are:

Step 1: Review the guidelines or instructions of the instructor

It is an initial step, where you should review the guidelines. By reading the guidelines you will be able to address the different requirements for presenting the results. While reviewing the guidelines you should also keep in mind the restrictions related to the interpretations. In the reseal findings sections, you can also make a comparison between your research results with the outcome of the investigation which other researchers have performed.

Step 2: Focus on the results of the experiment and other findings

At this step, you should choose specific focus experimental results and other research discoveries which are relevant to research questions and objectives. You utilizing subheadings can avoid excessive and peripheral details. Students can present raw data in appendices of a research paper. You should provide a summary of key findings after completion of the section. Before making the decision related to the structure of the findings section, you need to consider the hypothesis in research and research questions . You should match the format of the findings chapter with that of the research methods sections.

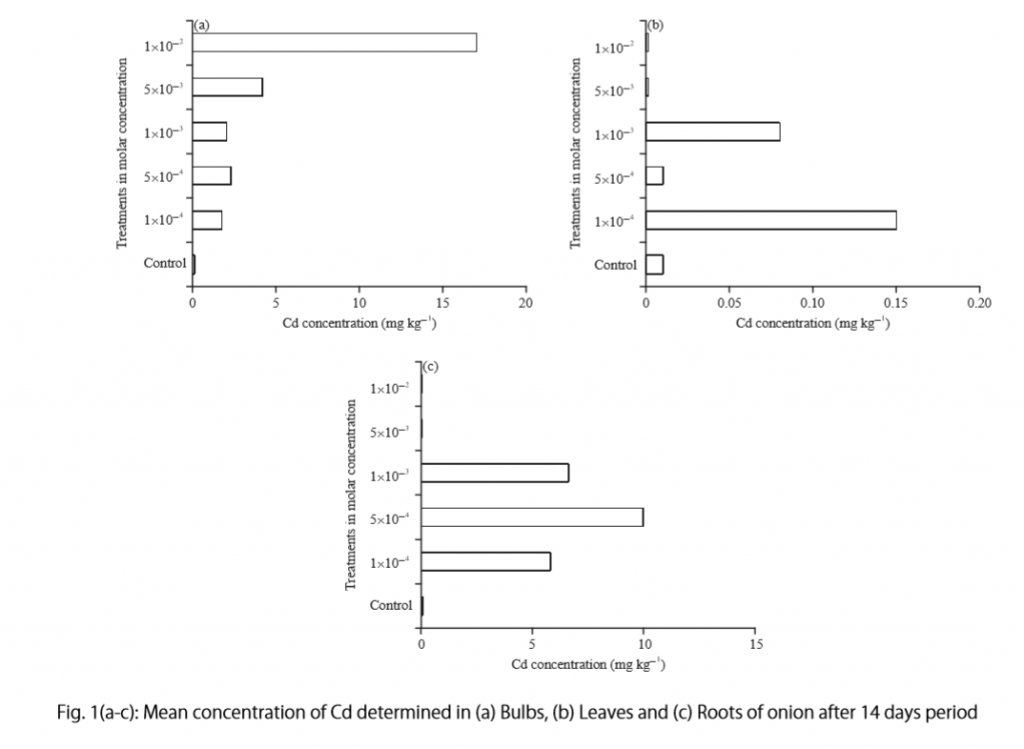

Step 3: Design effective visual presentations

Designing effective visual presentations of research results will help you in improving textual reports of findings. Students can use tables of different styles and unique figures such as maps, graphs, photos which are mainly used by researchers for presenting research findings. But it is very much essential for you to review the journal guidelines. As this is the tactics which will help you in analyzing the requirement of labeling and specific type of formatting. You should number tables, figures, and placement in the manuscript. You should provide a clear and detailed explanation of the data in tables and charts. Tables and figures should also be self-explanatory

Step 4: Write findings section

You should write the findings sections in a factual and objective manner. While writing the research findings section you should keep in mind its aim. The main aim of the specific section is to communicate information. While writing a findings chapter, it is very much important for you to construct sentences by using a simple structure. You should use an active voice for writing research-finding chapters. It is very much crucial for you to maintain your concentration on grammar, punctuation, and spelling. Students can utilize a special type of terminology for presenting the findings of the study. You can use thematic analysis in research for presenting the findings. In the thematic analysis technique, you need to design themes on the basis of the answers of respondents.

You should use a logical approach for organizing the findings section in a research paper. it is very much necessary to highlight the main point and provide summary information which is important for readers in order to develop an understanding of the research discussion section.

Step 5: Review draft of findings section

After writing the findings, you should revise and review them. It is the review technique that will enable you to check accuracy and consistency in information. You can read the content aloud. It s the strategy which will help you in addressing the mistakes. Ensure that the order in which you have presented results is the best order for focusing readers on your research objectives and preparing them for the interpretations, speculations. Students can also provide recommendations in the discussion chapter. They in order to provide good suggestions need to review back such as introduction, background material.

Read Also: Research Paper Conclusion Tips

Techniques of summarizing important findings

There are a few techniques that you can apply for writing your findings section in a systematic manner. Firstly, you should summarize the key findings. For example, you should start your finding a section like this:

- The outcome of research reveals that ……

- The investigation represents the correlation among….

- While writing the finding section in a research paper, you do not include information that is not important.

- You should provide a synopsis of outcomes along with a detailed description of the findings. It is considered to be an effective approach that can be applied to highlighting the key finding.

- You should use graphs, tables, and charts for presenting the finding

- While writing the findings section you need to highlight the negative outcomes. Students also need to provide proper justification and explanation for the same.

Stuck During Your Dissertation

Our top dissertation writing experts are waiting 24/7 to assist you with your university project,from critical literature reviews to a complete PhD dissertation.

Other Related Guides

- Research Project Questions

- Types of Validity in Research – Explained With Examples

- Schizophrenia Sample Research Paper

- Quantitative Research Methods – Definitive Guide

- Research Paper On Homelessness For College Students

- How to Study for Biology Final Examination

- Textual Analysis in Research / Methods of Analyzing Text

A Guide to Start Research Process – Introduction, Procedure and Tips

- Topic Sentences in Research Paper – Meaning, Parts, Importance, Procedure and Techniques

Recent Research Guides for 2023

Get 15% off your first order with My Research Topics

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

My Research Topics is provides assistance since 2004 to Research Students Globally. We help PhD, Psyd, MD, Mphil, Undergrad, High school, College, Masters students to compete their research paper & Dissertations. Our Step by step mentorship helps students to understand the research paper making process.

Research Topics & Ideas

- Sociological Research Paper Topics & Ideas For Students 2023

- Nurses Research Paper Topics & Ideas 2023

- Nursing Capstone Project Research Topics & Ideas 2023

- Unique Research Paper Topics & Ideas For Students 2023

- Teaching Research Paper Topics & Ideas 2023

- Literary Research Paper Topics & Ideas 2023

- Nursing Ethics Research Topics & Ideas 2023

Research Guide

Disclaimer: The Reference papers provided by the Myresearchtopics.com serve as model and sample papers for students and are not to be submitted as it is. These papers are intended to be used for reference and research purposes only.

From Data to Discovery: The Findings Section of a Research Paper

Discover the role of the findings section of a research paper here. Explore strategies and techniques to maximize your understanding.

Are you curious about the Findings section of a research paper? Did you know that this is a part where all the juicy results and discoveries are laid out for the world to see? Undoubtedly, the findings section of a research paper plays a critical role in presenting and interpreting the collected data. It serves as a comprehensive account of the study’s results and their implications.

Well, look no further because we’ve got you covered! In this article, we’re diving into the ins and outs of presenting and interpreting data in the findings section. We’ll be sharing tips and tricks on how to effectively present your findings, whether it’s through tables, graphs, or good old descriptive statistics.

Overview of the Findings Section of a Research Paper

The findings section of a research paper presents the results and outcomes of the study or investigation. It is a crucial part of the research paper where researchers interpret and analyze the data collected and draw conclusions based on their findings. This section aims to answer the research questions or hypotheses formulated earlier in the paper and provide evidence to support or refute them.

In the findings section, researchers typically present the data clearly and organized. They may use tables, graphs, charts, or other visual aids to illustrate the patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. The findings should be presented objectively, without any bias or personal opinions, and should be accompanied by appropriate statistical analyses or methods to ensure the validity and reliability of the results.

Organizing the Findings Section

The findings section of the research paper organizes and presents the results obtained from the study in a clear and logical manner. Here is a suggested structure for organizing the Findings section:

Introduction to the Findings

Start the section by providing a brief overview of the research objectives and the methodology employed. Recapitulate the research questions or hypotheses addressed in the study.

To learn more about methodology, read this article .

Descriptive Statistics and Data Presentation

Present the collected data using appropriate descriptive statistics. This may involve using tables, graphs, charts, or other visual representations to convey the information effectively. Remember: we can easily help you with that.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Perform a thorough analysis of the data collected and describe the key findings. Present the results of statistical analyses or any other relevant methods used to analyze the data.

Discussion of Findings

Analyze and interpret the findings in the context of existing literature or theoretical frameworks . Discuss any patterns, trends, or relationships observed in the data. Compare and contrast the results with prior studies, highlighting similarities and differences.

Limitations and Constraints

Acknowledge and discuss any limitations or constraints that may have influenced the findings. This could include issues such as sample size, data collection methods, or potential biases.

Summarize the main findings of the study and emphasize their significance. Revisit the research questions or hypotheses and discuss whether they have been supported or refuted by the findings.

Presenting Data in the Findings Section

There are several ways to present data in the findings section of a research paper. Here are some common methods:

- Tables : Tables are commonly used to present organized and structured data. They are particularly useful when presenting numerical data with multiple variables or categories. Tables allow readers to easily compare and interpret the information presented. Learn how to cite tables in research papers here .

- Graphs and Charts: Graphs and charts are effective visual tools for presenting data, especially when illustrating trends, patterns, or relationships. Common types include bar graphs, line graphs, scatter plots, pie charts, and histograms. Graphs and charts provide a visual representation of the data, making it easier for readers to comprehend and interpret.

- Figures and Images: Figures and images can be used to present data that requires visual representation, such as maps, diagrams, or experimental setups. They can enhance the understanding of complex data or provide visual evidence to support the research findings.

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics provide summary measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and dispersion (e.g., standard deviation, range) for numerical data. These statistics can be included in the text or presented in tables or graphs to provide a concise summary of the data distribution.

How to Effectively Interpret Results

Interpreting the results is a crucial aspect of the findings section in a research paper. It involves analyzing the data collected and drawing meaningful conclusions based on the findings. Following are the guidelines on how to effectively interpret the results.

Step 1 – Begin with a Recap

Start by restating the research questions or hypotheses to provide context for the interpretation. Remind readers of the specific objectives of the study to help them understand the relevance of the findings.

Step 2 – Relate Findings to Research Questions

Clearly articulate how the results address the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss each finding in relation to the original objectives and explain how it contributes to answering the research questions or supporting/refuting the hypotheses.

Step 3 – Compare with Existing Literature

Compare and contrast the findings with previous studies or existing literature. Highlight similarities, differences, or discrepancies between your results and those of other researchers. Discuss any consistencies or contradictions and provide possible explanations for the observed variations.

Step 4 – Consider Limitations and Alternative Explanations

Acknowledge the limitations of the study and discuss how they may have influenced the results. Explore alternative explanations or factors that could potentially account for the findings. Evaluate the robustness of the results in light of the limitations and alternative interpretations.

Step 5 – Discuss Implications and Significance

Highlight any potential applications or areas where further research is needed based on the outcomes of the study.

Step 6 – Address Inconsistencies and Contradictions

If there are any inconsistencies or contradictions in the findings, address them directly. Discuss possible reasons for the discrepancies and consider their implications for the overall interpretation. Be transparent about any uncertainties or unresolved issues.

Step 7 – Be Objective and Data-Driven

Present the interpretation objectively, based on the evidence and data collected. Avoid personal biases or subjective opinions. Use logical reasoning and sound arguments to support your interpretations.

Reporting Statistical Significance

When reporting statistical significance in the findings section of a research paper, it is important to accurately convey the results of statistical analyses and their implications. Here are some guidelines on how to report statistical significance effectively:

- Clearly State the Statistical Test: Begin by clearly stating the specific statistical test or analysis used to determine statistical significance. For example, you might mention that a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, correlation analysis, or regression analysis was employed.

- Report the Test Statistic: Provide the value of the test statistic obtained from the analysis. This could be the t-value, F-value, chi-square value, correlation coefficient, or any other relevant statistic depending on the test used.

- State the Degrees of Freedom: Indicate the degrees of freedom associated with the statistical test. Degrees of freedom represent the number of independent pieces of information available for estimating a statistic. For example, in a t-test, degrees of freedom would be mentioned as (df = n1 + n2 – 2) for an independent samples test or (df = N – 2) for a paired samples test.

- Report the p-value: The p-value indicates the probability of obtaining results as extreme or more extreme than the observed results, assuming the null hypothesis is true. Report the p-value associated with the statistical test. For example, p < 0.05 denotes statistical significance at the conventional level of α = 0.05.

- Provide the Conclusion: Based on the p-value obtained, state whether the results are statistically significant or not. If the p-value is less than the predetermined threshold (e.g., p < 0.05), state that the results are statistically significant. If the p-value is greater than the threshold, state that the results are not statistically significant.

- Discuss the Interpretation: After reporting statistical significance, discuss the practical or theoretical implications of the finding. Explain what the significant result means in the context of your research questions or hypotheses. Address the effect size and practical significance of the findings, if applicable.

- Consider Effect Size Measures: Along with statistical significance, it is often important to report effect size measures. Effect size quantifies the magnitude of the relationship or difference observed in the data. Common effect size measures include Cohen’s d, eta-squared, or Pearson’s r. Reporting effect size provides additional meaningful information about the strength of the observed effects.

- Be Accurate and Transparent: Ensure that the reported statistical significance and associated values are accurate. Avoid misinterpreting or misrepresenting the results. Be transparent about the statistical tests conducted, any assumptions made, and potential limitations or caveats that may impact the interpretation of the significant results.

Conclusion of the Findings Section

The conclusion of the findings section in a research paper serves as a summary and synthesis of the key findings and their implications. It is an opportunity to tie together the results, discuss their significance, and address the research objectives. Here are some guidelines on how to write the conclusion of the Findings section:

Summarize the Key Findings

Begin by summarizing the main findings of the study. Provide a concise overview of the significant results, patterns, or relationships that emerged from the data analysis. Highlight the most important findings that directly address the research questions or hypotheses.

Revisit the Research Objectives

Remind the reader of the research objectives stated at the beginning of the paper. Discuss how the findings contribute to achieving those objectives and whether they support or challenge the initial research questions or hypotheses.

Suggest Future Directions

Identify areas for further research or future directions based on the findings. Discuss any unanswered questions, unresolved issues, or new avenues of inquiry that emerged during the study. Propose potential research opportunities that can build upon the current findings.

The Best Scientific Figures to Represent Your Findings

Have you heard of any tool that helps you represent your findings through visuals like graphs, pie charts, and infographics? Well, if you haven’t, then here’s the tool you need to explore – Mind the Graph . It’s the tool that has the best scientific figures to represent your findings. Go, try it now, and make your research findings stand out!

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

About Sowjanya Pedada

Sowjanya is a passionate writer and an avid reader. She holds MBA in Agribusiness Management and now is working as a content writer. She loves to play with words and hopes to make a difference in the world through her writings. Apart from writing, she is interested in reading fiction novels and doing craftwork. She also loves to travel and explore different cuisines and spend time with her family and friends.

Content tags

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Dissertation Methodology – Structure, Example...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE: Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|