Compilation and Presentation of Evidence

ARTICLE 2 October 2023

Evidence is how you or the opposing party can prove or refute the facts in your case.

When presenting evidence in a trial, it's essential to consider a series of recommendations to avoid problems in the final stages of the case, states our Head of Litigation and Arbitration Department, Rubén Rivas.

"The compilation of evidence involves the search, acquisition, and organization of documents, records, witness testimonies, experts, and any other means of proof that may be relevant to the case. This process may include research, requesting documents from third parties, conducting interviews with witnesses, and obtaining expert reports," says Rivas.

Our associate attorney lists the steps for compiling and presenting evidence:

- Know the rules of evidence: Familiarize yourself with the specific rules and procedures governing the presentation of evidence in the court where the trial takes place. This includes knowing the objections that can be raised, authenticity requirements, and admissibility standards.

- Gather relevant and credible evidence: Identify and carefully gather evidence that supports your case. Ensure that it is relevant to the issues in dispute and credible. This may include documents, records, witness testimonies, photographs, or other means of proof.

- Prepare and organize your evidence: Organize your evidence clearly and systematically to facilitate its presentation at the trial. Use labels, indexes, or folders to keep it orderly and accessible. Additionally, prepare additional copies of relevant documents to share with the court, attorneys, and involved parties.

- Obtain affidavits or testimonies: If you have relevant witnesses, make sure to obtain their affidavits or written testimonies in advance. This will allow you to present their testimonies consistently and coherently during the trial.

- Consult experts: If the evidence requires specialized knowledge, consider consulting experts in the relevant field. These experts can provide opinions and technical analysis that support your case and help interpret the evidence more accurately.

- Be clear and concise when presenting evidence: When presenting evidence during the trial, be clear, concise, and focused on key points. Avoid digressions or irrelevant details that may distract or confuse the court. Use charts, images, or audiovisual media if necessary to enhance the understanding of the evidence.

- Maintain objectivity: When presenting evidence, avoid manipulating or distorting it to support your position. Evidence should be presented objectively and honestly, allowing the court to assess its weight and credibility.

- Prepare your witnesses: If you have witnesses who will testify during the trial, make sure to prepare them adequately. Review relevant facts with them, the questions they will be asked, and potential objections. This will help ensure that they provide clear and coherent testimonies.

- Respect the court's rules: During the presentation of evidence, follow the judge's instructions and adhere to procedural rules. Avoid unnecessary interruptions, do not interrupt opposing attorneys, and maintain a respectful tone at all times.

- Work closely with your attorney: Collaborate closely with your attorney in the preparation and presentation of evidence. Trust their expertise and follow their advice on how to present your case more effectively.

-Written by the Torres Legal Team.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Nonrational sources of evidence

Semirational sources of evidence, the influence of roman-canonical law.

- Oral proceedings

- The burden of proof

- Relevance and admissibility

- The free evaluation of evidence

- Examination and cross-examination

- The hearsay rule

- Confessions and admissions

- Party testimony

- Expert evidence

- Documentary evidence

- Real evidence

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- State Library of NSW - Find Legal Answers - Precedent and evidence

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Evidence

- Table Of Contents

evidence , in law, any of the material items or assertions of fact that may be submitted to a competent tribunal as a means of ascertaining the truth of any alleged matter of fact under investigation before it.

To the end that court decisions are to be based on truth founded on evidence, a primary duty of courts is to conduct proper proceedings so as to hear and consider evidence. The so-called law of evidence is made up largely of procedural regulations concerning the proof and presentation of facts, whether involving the testimony of witnesses, the presentation of documents or physical objects, or the assertion of a foreign law. The many rules of evidence that have evolved under different legal systems have, in the main, been founded on experience and shaped by varying legal requirements of what constitutes admissible and sufficient proof.

Although evidence, in this sense, has both legal and technical characteristics, judicial evidence has always been a human rather than a technical problem. During different periods and at different cultural stages, problems concerning evidence have been resolved by widely different methods. Since the means of acquiring evidence are clearly variable and delimited, they can result only in a degree of probability and not in an absolute truth in the philosophical sense. In common-law countries, civil cases require only preponderant probability, and criminal cases require probability beyond reasonable doubt. In civil-law countries so much probability is required that reasonable doubts are excluded.

The early law of evidence

Characteristic features of the law of evidence in earlier cultures were that no distinction was made between civil and criminal matters or between fact and law and that rational means of evidence were either unknown or little used. In general, the accused had to prove his innocence.

The appeal to supernatural powers was, of course, not evidence in the modern sense but an ordeal in which God was appealed to as the highest judge. The judges of the community determined what different kinds of ordeals were to be suffered, and frequently the ordeals involved threatening the accused with fire, a hot iron, or drowning. It may be that a certain awe associated with the two great elements of fire and water made them appear preeminently suitable for dangerous tests by which God himself was to pass on guilt or innocence. Trial by battle had much the same origin. To be sure, the powerful man relied on his strength, but it was also assumed that God would be on the side of right.

The accused free person could offer to exonerate himself by oath . Under these circumstances, in contrast to the ordeals, it was not expected that God would rule immediately but rather that he would punish the perjurer at a later time. Nevertheless, there was ordinarily enough realism so that the mere oath of the accused person alone was not allowed. Rather, he was ordered to swear with a number of compurgators , or witnesses, who confirmed, so to speak, the oath of the person swearing. They stood as guarantees for his oath but never gave any testimony about the facts.

The significance of these first witnesses is seen in the use of the German word Zeuge , which now means “witness” but originally meant “drawn in.” The witnesses were, in fact, “drawn in” to perform a legal act as instrumental witnesses. But they gave only their opinions and consequently did not testify about facts with which they were acquainted. Nevertheless, together with community witnesses, they paved the way for the more rational use of evidence.

By the 13th century, ordeals were no longer used, though the custom of trial by battle lasted until the 14th and 15th centuries. The judicial machinery destroyed by dropping these sources of evidence could not be replaced by the oath of purgation alone. With the decline of chivalry , the flourishing of the towns, the further development of Christian theology, and the formation of states, both social and cultural conditions had changed. The law of evidence, along with much of the rest of the law of Europe, was influenced strongly by Roman-canonical law elaborated by jurists in northern Italian universities. Roman law introduced elements of common procedure that became known throughout the continental European countries and became something of a uniting bond between them.

Under the new influence, evidence was, first of all, evaluated on a hierarchical basis. This accorded well with the assumption of scholastic philosophy that all the possibilities of life could be formally ordered through a system of a priori , abstract regulations. Since the law was based on the concept of the inequality of persons, not all persons were suitable as witnesses, and only the testimony of two or more suitable witnesses could supply proof.

The formal theory of evidence that grew out of this hierarchical evaluation left no option for the judge: in effect, he was required to be convinced after the designated number of witnesses had testified concordantly. A distinction was made between complete, half, and lesser portions of evidence, evading the problem posed by such a rigid system of evaluation. Since interrogation of witnesses was secret, abuses occurred on another level. These abuses were nourished by the notion that the confession was the best kind of evidence and that reliable confessions could be obtained by means of torture.

Despite these obvious drawbacks and limitations, through the ecclesiastical courts Roman-canonical law gained influence. It contributed much to the elimination of nonrational evidence from the courts, even though, given the formality of its application, it could result only in formal truths often not corresponding to reality.

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

By Prof. Penny White

Federal Rules of Evidence

The Federal Rules of Evidence govern the introduction of evidence at civil and criminal trials in United States federal trial courts. The current rules were initially passed by Congress in 1975 after several years of drafting by the Supreme Court. The rules are broken down into 11 articles:

- General Provisions

- Judicial Notice

- Presumptions in Civil Actions and Proceedings

- Relevancy and Its Limits

- Opinions and Expert Testimony

- Authentication and Identification

- Contents of Writings, Recordings and Photographs

- Miscellaneous Rules

This article will focus on Rule 901 — Authenticating or Identifying Evidence — and the judge’s role in the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Establish Evidentiary Foundations

Evidentiary foundations must be established before any type of evidence can be admitted. These predicates to admission apply regardless of whether the evidence is verbal or tangible, but for some types of evidence, the foundation is largely subsumed into the presentation of the evidence itself. For example, the foundation for verbal evidence is generally a requirement that the testifying witness have personal knowledge of the matter in question. This foundation is rarely established by asking the witness specifically whether he or she has personal knowledge. Rather, it is included in the witness’ testimony which discloses that the witness experienced the occurrence. But for all types of evidence, the evidentiary foundation requires authentication before other issues of admissibility are considered.

Tangible Items of Evidence

Scholars at common law recognized that authentication and identification of tangible items of evidence represented a “special aspect of relevancy.” McCormick §§179, 185; Morgan, Basic Problems of Evidence 378 (1962). Wigmore describes the need for authentication as “an inherent logical necessity.” 7 Wigmore §2129, p. 564. The authenticity requirement falls into the category of conditional relevancy – before the item of evidence becomes relevant and admissible, it must be established that the item is what the proponent claims.

Authentication of Tangible Items of Evidence

The basic codified standard for the authentication of tangible items of evidence is “evidence sufficient to support a finding that the item is what the proponent claims it is.” Fed. R. Evid. 901. It is not necessary that the court find that the evidence is what the proponent claims, only that there is sufficient evidence from which the jury might ultimately do so. This is a low threshold standard. The laws of evidence set forth the general standard, followed by illustrations and a list of several types of self-authenticated documents. The proponent of any tangible or documentary evidence has an obligation, or burden of proof, to authenticate the evidence before requesting to admit or publish it to the fact- finder; if the opponent objects to its admissibility, based on any of a collection of rules, then the proponent must address that admissibility objection as well. Thus, all evidence must be both authenticated and admissible.

Determine the Presentation of Evidence

If both authentication and admissibility are established, then the court must determine how the evidence will best be presented to the trier of fact, bearing in mind that the court is obligated to exercise control over the presentation of evidence to accomplish an effective, fair, and efficient proceeding. Under Federal Rules 611, the court’s duty is to “exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of examining witnesses and presenting evidence so as to:

- Make those procedures effective for determining the truth

- Avoid wasting time

- Protect witnesses from harassment or undue embarrassment

Sometimes tangible evidence consists of fungible items that are not identifiable by sight. For tangible evidence that is not unique or distinctive, counsel must authenticate the item by establishing a chain of custody.

Establish a Chain of Custody

A chain of custody is, in essence, a consistent trail showing the path of the item from the time it was acquired until the moment it is presented into evidence. In establishing a chain of custody, each link in the chain should be sufficiently established. However, it is not required that the identity of tangible evidence be proven beyond all possibility of doubt. Most courts hold that “when the facts and circumstances that surround tangible evidence reasonably establish the identity and integrity of the evidence, the trial court should admit the item into evidence [but] the evidence should not be admitted, unless both identity and integrity can be demonstrated by other appropriate means.” See generally State v. Cannon, 254 S.W.3d 287, 296-97 (Tenn. 2008).

Additional Rules of Evidence Considerations for Tangible Evidence

For tangible evidence, in addition to authentication, the court must consider the following.

- Relevance rules

- The hearsay rules

- The original writing rules

- When appropriate, must balance the probative value of the tangible evidence against the dangers that its introduction may cause

The court in a jury trial must also consider what method of producing the evidence to a jury is most conducive to a fair and efficient fact-finding process.

Electronic Evidence

In order to admit electronic evidence, the same rules apply, but the content of electronic electronically stored information (ESI evidence) may implicate other rules such as the opinion rules and the personal knowledge rule. Most scholars and courts agree that the issues related to the authentication and admissibility of electronic evidence simply depend on an application of the existing evidence rules. Although technical challenges may arise, the rules are flexible enough in their approach to address this new kind of evidence.

Checklist for Authenticating Evidence in Court

The Federal Rules of Evidence apply regardless of whether the evidence is submitted in a civil case or criminal trial. To ensure that evidence is authentic and admissible, follow this five-point generic checklist for the authentication of tangible, documentary, or electronic evidence:

1. Is the evidence relevant?

Does it make a fact that is of consequence to the action more or less probable than it would be without the evidence?

2. Has the evidence been authenticated?

Has the proponent produce “evidence sufficient to support a finding that the electronic evidence is what the proponent claims?”

3. Is the evidence hearsay?

Is the evidence offered to prove the truth of what it asserts? If so, does it satisfy a hearsay exception? Are confrontation rights implicated?

4. Is the evidence a writing, recording, or photograph?

Is it offered to prove the content? If so, is it either the original or a duplicate (counterpart produced by the same impression as the original, or from the same matrix, etc.) unless genuine questions of authenticity or fairness exist?

5. Is the probative value of the evidence substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of cumulative evidence?

Of course, there are many other tools that a judge may use to rule on tangible and electronic evidence, each with its own benefits and limitations.

Penny White is the Director of the Center for Advocacy and Elvin E. Overton Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Tennessee College of Law. She teaches in several of NJC’s evidence courses including Fundamentals of Evidence, Advanced Evidence, and Criminal Evidence.

After 22 years of teaching judges, Tennessee Senior Judge Don Ash will retire as a regular faculty member a...

This month’s one-question survey* of NJC alumni asked, “How is 2024 shaping up for you and your court?�...

RENO, NV (PNS) – As they eye their inaugural football season this fall, the Gaveliers have question marks...

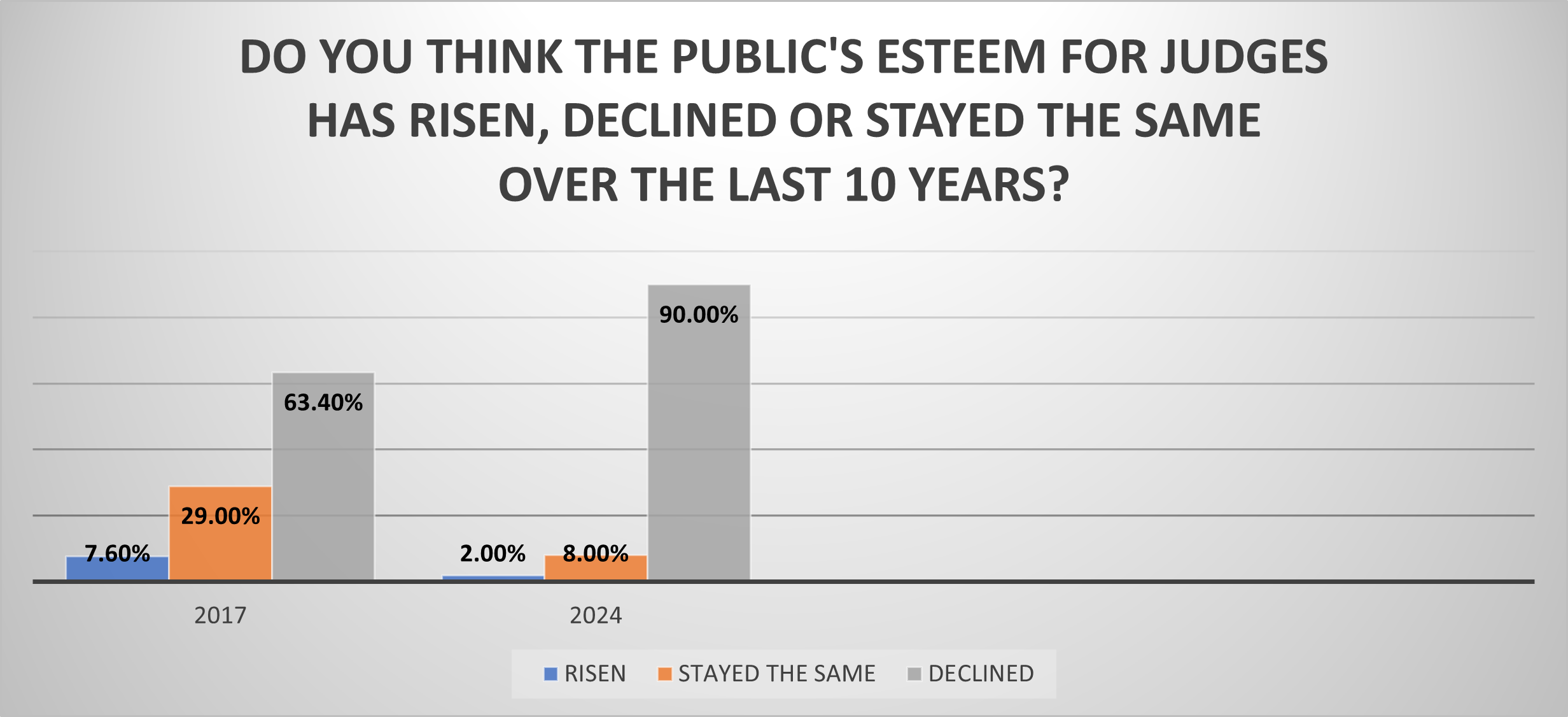

RENO, Nev. (March 8, 2024) — In what may reflect a devastating blow to the morale of the judiciary, 9 out...

Download a PDF of our 2024 course list

Definition of Evidence

Gathering and submitting evidence, types of evidence, scientific evidence, trace evidence, about dna evidence, physical evidence, testimonial evidence, circumstantial evidence, hearsay evidence, exculpatory evidence, rules of evidence, scott peterson and the circumstantial evidence, related legal terms and issues.

10 Steps for Presenting Evidence in Court

When you go to court, you will give information (called “evidence”) to a judge who will decide your case. This evidence may include information you or someone else tells to the judge (“testimony”) as well as items like email and text messages, documents, photos, and objects (“exhibits”). If you don’t have an attorney, you will need to gather and present your evidence in the proper way. Courts have rules about evidence so that judges will make decisions based on good information, not gossip and guesswork.

Although the rules can be confusing, they are designed to protect your rights, and you can use them to help you plan for your court appearance. Even though courts work differently, this publication will introduce you to the nuts and bolts of presenting evidence at a hearing. As you read it, please consider the kind of help you might want as you prepare and present your case.

With funding from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) developed the Implementation Sites Project to assist juvenile and family courts to integrate…

Juvenile justice system professionals are often unaware of or misinterpret the circumstances of commercially sexually exploited youths. As a result, many victims of sexual exploitation are criminalized instead of being diverted to appropriate resources and…

The technical assistance brief, A Template Guide to Develop a Memorandum of Understanding Between a Military Installation and a Court, is a tool for courts and military installations to utilize to enter into agreements that may…

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.2: Defining Evidence

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 152119

- Jim Marteney

- Los Angeles Valley College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

What is evidence? According to Reike and Sillars (1993), ”[e]vidence refers to specific instances, statistics, and testimony, when they support a claim in such a way as to cause the decision maker(s) to grant adherence to that claim” (p. 10).

Evidence is information that answers the question “ How do you know ? ” of a contention you have made. Please take that question very literally. It is often hard to tell the difference at first between telling someone what you know and telling them how you know it. To become an effective speaker in almost any context, you need to be able to ask this question repeatedly and test the answers you hear to determine the strength of the evidence.

Only experts can use phrases like "I think" or "I feel" or "I believe" as they have the qualifications needed that allow you to accept their observations. As for everyone else, we need to use evidence to support our arguments. As a critical thinker, you should rely much more on what a person can prove to a reasonable degree instead of what a person feels.

Evidence is a term commonly used to describe the supporting material utilized when informing or persuading others. Evidence gives support to your statements and arguments. It also makes your arguments more than a mere collection of personal opinions or prejudices. No longer are you saying, “ I believe ” or “ I think ” or “ In my opinion .” Now you can support your assertions with evidence. Because you are asking your audience to take a risk when you attempt to inform or persuade them, audiences will demand support for your assertions. Evidence needs to be carefully chosen to serve the needs of the claim and to reach the target audience.

An argument is designed to persuade a resistant audience to accept a claim via the presentation of evidence for the contentions being argued. The evidence establishes the amount of accuracy your arguments have. Evidence is one element of proof (the second is reasoning), that is used as a means of moving your audience toward the threshold necessary for them to grant adherence to your arguments.

The speaker should expect audiences to not be persuaded by limited evidence or by a lack of variety/scope, evidence drawn from only one source as opposed to diverse sources. On the other hand, too much evidence, particularly when not carefully crafted, may leave the audience overwhelmed and without focus. Evidence in support of the different contentions in the argument needs to make the argument reasonable enough to be accepted by the target audience.

Challenge of Too Much Evidence

I attended a lecture years ago where the guest speaker told us that we have access to more information in one edition of the New York Times than a man in the middle ages had in his entire lifetime. The challenge is not finding information, the challenge is sorting through information to find quality evidence to use in our speeches . Shenk (1997) expresses his concern in the first chapter:

Information has also become a lot cheaper--to produce, to manipulate, to disseminate. All of this has made us information-rich, empowering Americans with the blessings of applied knowledge. It has also, though, unleashed the potential of information-gluttony...How much of the information in our midst is useful, and how much of it gets in the way? ... As we have accrued more and more of it, information has emerged not only as a currency, but also as a pollutant (p. 23).

- In 1971 the average American was targeted by at least 560 daily advertising messages. Twenty years later, that number had risen six-fold to 3,000 messages per day.

- In the office, an average of 60 percent of each person's time is now spent processing documents.

- Paper consumption per capita in the United States tripled from 1940 to 1980 (from 200 to 600 pounds) and tripled again from 1980 to 1990 (to 1,800 pounds).

- In the 1980s, third-class mail (used to send publications) grew thirteen times faster than population growth.

- Two-thirds of business managers surveyed report tension with colleagues, loss of job satisfaction, and strained personal relationships as a result of information overload.

- More than 1,000 telemarketing companies employ four million Americans, and generate $650 billion in annual sales.

"Let us call this unexpected, unwelcome part of our atmosphere "data smog," an expression for the noxious muck and druck of the information age. Data smog gets in the way; it crowds out quiet moments and obstructs much-needed contemplation. It spoils conversation, literature, and even entertainment. It thwarts skepticism, rendering us less sophisticated as consumers and citizens. It stresses us out” (Shenk, 1997, p. 24).

We need ways of sorting through this information and the first method is understanding the different types of evidence that we encounter.

Sources of Evidence

The first aspect of evidence we need to explore is the actual source of evidence or where we find evidence. There are two primary sources of evidence; primary sources and secondary sources.

Primary Sources

A primary source provides direct or firsthand evidence about an event, object, person, or work of art. Primary sources include historical and legal documents, eyewitness accounts, results of experiments, statistical data, pieces of creative writing, audio and video recordings, speeches, and art objects. Interviews, surveys, fieldwork, and Internet communications via email, blogs, tweets, and newsgroups are also primary sources. In the natural and social sciences, primary sources are often empirical studies—research where an experiment was performed or a direct observation was made. The results of empirical studies are typically found in scholarly articles that are peer-reviewed (Ithica College, 2019)

Included in primary sources are:

- Original, first-hand accounts of events, activities, or time periods;

- Factual accounts instead of interpretations of accounts or experiments;

- Results of an experiment;

- Reports of scientific discoveries;

- Results of scientifically based polls.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources describe, discuss, interpret, comment upon, analyze, evaluate, summarize, and process primary sources. Secondary source materials can be articles in newspapers or popular magazines, book, movie reviews, or articles found in scholarly journals that discuss or evaluate someone else's original research (Ithica, 2019).

Included in secondary sources are:

- Analyzation and interpretation of the accounts of primary sources;

- Secondhand account of an activity or historical event;

- Analyzation and interpretation of scientific or social research results.

The key difference between the two sources is how far the author of the evidence is removed from the original event. You want to ask, " Is the author giving you a firsthand account, or a secondhand account? "

Types of Evidence

There are five types of evidence critical thinkers can use to support their arguments: precedent evidence, statistical evidence, testimonial evidence, hearsay evidence, and common knowledge evidence .

Precedent evidence is an act or event which establishes expectations for future conduct. There are two forms of precedent evidence: legal and personal.

Legal precedent is one of the most powerful and most difficult types of evidence to challenge. Courts establish legal precedent. Once a court makes a ruling, that ruling becomes the legal principle upon which other courts base their actions. Legislatures can also establish precedent through the laws they pass and the laws they choose not to pass. Once a principle of law has been established by a legislative body, it is very difficult to reverse.

Personal precedents are the habits and traditions you maintain. They occur as a result of watching the personal actions of others in order to understand the expectations for future behaviors. Younger children in a family watch how the older children are treated in order to see what precedents are being established. Newly employed on a job watch to see what older workers do in terms of breaks and lunchtime in order that their actions may be consistent. The first months of a marriage is essentially a time to establish precedent. Who does the cooking, who takes out the garbage, who cleans, which side of the bed does each person get, are precedents established early in a marriage. Once these precedents are displayed, an expectation of the other’s behavior is established. Such precedent is very difficult to alter.

To use either type of precedent as evidence, the arguer refers to how the past event relates to the current situation. In a legal situation, the argument is that the ruling in the current case should be the same as it was in the past, because they represent similar situations. In a personal situation, if you were allowed to stay out all night by your parents "just once," you can use that "just once" as precedent evidence when asking that your curfew be abolished.

Statistical evidence consists primarily of polls, surveys, and experimental results from the laboratory. This type of evidence is the numerical reporting of specific instances. Statistical evidence provides a means for communicating a large number of specific instances without citing each one. Statistics can be manipulated and misused to make the point of the particular advocate.

Don’t accept statistics just because they are numbers. People often fall into the trap of believing whatever a number says, because numbers seem accurate. Statistics are the product of a process subject to human prejudice, bias, and error. Questions on a survey can be biased, the people surveyed can be selectively chosen, comparisons may be made of non-comparable items, and reports of findings can be slanted. Take a look at all the polls that predict an election outcome. You will find variances and differences in the results.

Statistics have to be interpreted. In a debate over the use of lie detector tests to determine guilt or innocence in court, the pro-side cited a study which found that 98% of lie detector tests were accurate. The pro-side interpreted this to mean that lie detector tests were an effective means for determining guilt or innocence. However, the con-side interpreted the statistic to mean that two out of every 100 defendants in this country would be found guilty and punished for a crime they did not commit.

The great baseball announcer Vin Scully once described the misuse of statistics by a journalist by saying that “ He uses statistics like a drunk uses a lamppost, not for illumination but for support

Statistics are often no more reliable than other forms of evidence, although people often think they are. Advocates need to carefully analyze how they use statistics when attempting to persuade others. Likewise, the audience needs to question statistics that don't make sense to them.

Testimonial evidence is used for the purpose of assigning motives, assessing responsibilities, and verifying actions for past, present and future events. Testimony is an opinion of reality as stated by another person. There are three forms of testimonial evidence: eyewitness, expert-witness, and historiography.

Eyewitness testimony is a personal declaration as to the accuracy of an event. That is, the person actually saw an event take place and is willing to bear witness to that event. Studies have confirmed that eyewitness testimony, even with all of its problems, is a powerful form of evidence. There seems to be almost something "magical" about a person swearing to "tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth."

Expert-witness evidence calls upon someone qualified to make a personal declaration about the nature of the fact in question. Courts of law make use of experts in such fields as forensics, ballistics, and psychology. The critical thinker uses the credibility of another person to support an argument through statements about the facts or opinions of the situation.

What or who qualifies as an expert witness? Does being a former military officer make them an expert in military tactics? Often an advocate will merely pick someone who they know the audience will accept. But as an audience we should demand that advocates justify the expertise of their witness. As we acquire more knowledge, our standards of what constitutes an expert should rise. We need to make a distinction between sources that are simply credible like well-known athletes and entertainers that urge you to buy a particular product, and those who really have the qualities that allow them to make a judgment about a subject in the argumentative environment.

Although expert witness testimony is an important source of evidence, such experts can disagree. In a recent House Energy and Commerce subcommittee, two experts gave opposite testimony, on the same day, on a bill calling for a label on all aspirin containers warning of the drug's often fatal link to Reye's Syndrome. The head of the American Academy of Pediatrics gave testimony supporting the link, but Dr. Joseph White, President of The Aspirin Foundation of America, said there was insufficient evidence linking aspirin to Reye’s syndrome.

Historiography is the third form of testimonial evidence. In their book, ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY, Windes and Hastings write, "Historiographers are concerned in large part with the discovery, use, and verification of evidence. The historian traces influences, assigns motives, evaluates roles, allocates responsibilities, and juxtaposes events in an attempt to reconstruct the past. That reconstruction is no wiser, no more accurate or dependable than the dependability of the evidence the historian uses for his reconstruction." 5

Keep in mind that there are many different ways of determining how history happens. Remember, historians may disagree over why almost any event happened. In the search for how things happen, we get ideas about how to understand our present world's events and what to do about them, if anything.

Primary sources are essential to the study of history. They are the basis for what we know about the distant past and the recent past. Historians must depend on other evidence from the era to determine who said what, who did what, and why.

How successful is the historian in recreating “objective reality?" As noted historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. says,

“The sad fact is that, in many cases, the basic evidence for the historian’s reconstruction of the really hard cases does not exist, and the evidence that does exist is often incomplete, misleading, or erroneous. Yet, it is the character of the evidence which establishes the framework within which he writes. He cannot imagine scenes for which he has no citation, invent dialogue for which he has no text, assume relationships for which he has no warrant.”

Historical reconstruction must be done by a qualified individual to be classified as historical evidence. Critical thinkers will find it useful to consider the following three criteria for evaluating historical evidence.

Around 1,000 books are published internationally every day and the total of all printed knowledge doubles every 5 years.

More information is estimated to have been produced in the last 30 years than in the previous 5,000.

----The Reuters Guide to Good Information Strategy 2000

Was the author an eyewitness to what is being described, or is the author considered an authority on the subject? Eyewitness accounts can be the most objective and valuable but they may also be tainted with bias. If the author professes to be an authority, he/she should present his/her qualifications.

Does the author have a hidden agenda? The author may purposely or unwittingly tell only part of the story. The excerpt may seem to be a straight-forward account of the situation, yet the author has selected certain facts, details, and language, which advance professional, personal or political goals or beliefs. They may be factual, but the hidden agenda of these books was to make money for the author, or get even with those in the administration they didn't like.

Does the author have a bias? The author's views may be based on personal prejudice rather than a reasoned conclusion based on facts. Critical thinkers need to notice when the author uses exaggerated language, fails to acknowledge, or dismisses his or her opponents' arguments. Historians may have biases based on their political allegiance. Conservative historians would view events differently than a liberal historian. It is important to know the political persuasion of the historian in order to determine the extent of bias he or she might have on the specific topic they are writing about.

Sometimes we think we might know our history, but Historian Daniel Boorstin puts a perspective on the ultimate validity and accuracy of historical testimony when he writes, "Education is learning what you didn't even know you didn't know." Modern techniques of preserving data should make the task of recreating the past easier and adding to our education.

Hearsay evidence (also called rumor or gossip evidence) can be defined as an assertion or set of assertions widely repeated from person to person, though its accuracy is unconfirmed by firsthand observation. "Rumor is not always wrong , " wrote Tacitus, the Roman historian. A given rumor may be spontaneous or premeditated in origin. It may consist of opinion represented as fact, a nugget of accuracy garbled or misrepresented to the point of falsehood, exaggerations, or outright, intentional lies. Yet, hearsay may well be the "best available evidence" in certain situations where the original source of the information cannot be produced.

Rumor, gossip or hearsay evidence carries proportionately higher risks of distortion and error than other types of evidence. However, outside the courtroom, it can be as effective as any other form of evidence in proving your point. Large companies often rely on this type of evidence, because they lack the capability to deliver other types of evidence.

A recent rumor was started that actor Morgan Freeman had died. A page on “Facebook” was created and soon gained more that 60,000 followers, after it was announced that the actor had passed away. Many left their condolences and messages of tribute. Only one problem, Morgan Freeman was very much alive, actually that is not so much a problem, especially to Morgan Freeman. The Internet is a very effective tool when it comes to spreading rumors.

Common knowledge evidence is also a way to support one’s arguments. This type of evidence is most useful in providing support for arguments which lack any real controversy. Many claims are supported by evidence that comes as no particular surprise to anyone.

Basing an argument on common knowledge is the easiest method of securing belief in an idea, because an audience will accept it without further challenge. Patterson and Zarefsky (1983) explain:

Many argumentative claims we make are based on knowledge generally accepted by most people as true. For example, if you claimed that millions of Americans watch television each day, the claim would probably be accepted without evidence. Nor would you need to cite opinions or survey results to get most people to accept the statement that millions of people smoke cigarettes 6 (Pat.

Credibility of Evidence or How Good Is It?

In order to tell us how you know something, you need to tell us where the information came from. If you personally observed the case you are telling us about, you need to tell us that you observed it, and when and where. If you read about it, you need to tell us where you read about it. If you are accepting the testimony of an expert, you need to tell us who the expert is and why she is an expert in this field. The specific identity, name or position and qualifications of your sources are part of the answer to the question “How do you know?” You need to give your audience that information.

Keep in mind that it is the person, the individual human being, who wrote an article or expressed an idea who brings authority to the claim. Sometimes that authority may be reinforced by the publication in which the claim appeared, sometimes not. But when you quote or paraphrase a source you are quoting or paraphrasing the author, not the magazine or journal. The credibility of the evidence you use can be enhanced by:

Specific Reference to Source : Does the advocate indicate the particular individual or group making the statements used for evidence? Does the advocate tell you enough about the source that you could easily find it yourself?

Qualifications of the Source: Does the advocate give you reason to believe that the source is competent and well-informed in the area in question?

Bias of the Source : Even if an expert, is the source likely to be biased on the topic? Could we easily predict the source’s position merely from knowledge of his job, her political party, or organizations he or she works for?

Factual Support: Does the source offer factual support for the position taken or simply state personal opinions as fact?

Evaluating Internet Sources of Evidence

We currently obtain a significant amount of the evidence we use in an argument from the Internet. Some people are still under the influence that if they read it on the Internet, it must be accurate. But we all know that some Internet sources are better than others. We need to be able to evaluate websites to obtain the best information possible. Here are two approaches to evaluating websites

Who, What, When, Where, and Why

This first test is based on the traditional 5 “W’s.” These questions, like critical thinking, go back to Greek and Roman times. The notable Roman, Cicero, who was in office in 63 BC, is credited with asking these questions

Journalists are taught to answer these five questions when writing an article for publication. To provide an accurate interpretation of events to their viewers or readers, they ask these five questions and we can ask the same questions to begin discovering the level of quality of an online source.

Who wrote the post? What are their qualifications?

What is actually being said in the website. How accurate is the content?

When was the website’s latest post?

Where is the source of the post? Does the URL suggest it is from an academic source or an individual?

Why is the website published? Is the website there to inform or entertain?

There is a second method of evaluating websites that is more popular and includes a more in depth analysis. This method is known as the CRAAP test.

The C.R.A.A.P. Test

C.R.A.A.P. is an acronym standing for Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose. Developed by the Meriam Library at the California State University at Chico, each of these five areas is used to evaluate websites.

Currency How recent is this website. If you are conducting research on some historical subject a web site that has no recent additions could be useful. If, however you are researching some current news story, or technology, or scientific topic, you will want a site that has been recently updated.

Questions to Ask:

- When was the content of the website published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated recently?

- Have more recent articles on your subject been published?

- Does your topic require the most current information possible, or will older posts and sources be acceptable?

- Are the web links included in the website functional?

- Relevance This test of a website asks you how important is the information to the specific topic you are researching. You will want to determine if you are the intended audience and if the information provided fits your research needs.

- Does the content relate to your research topic or the question you are answering?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level for the purpose of your work? In other words, is it college level or targeted to a younger or less educated audience?

- Have you compared this site to a variety of other resources?

- Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research project?

Authority Here we determine if the source of the website has the credentials to write on the subject which makes you feel comfortable in using the content. If you are looking for an accurate interpretation of news events, you will want to know if the author of the website is a qualified journalist or a random individual reposting content.

- Who is the author/ publisher/ source/ sponsor of the website?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Does the author have the qualifications to write on this particular topic?

- Can you find information about the author from reference sources or the Internet?

- Is the author quoted or referred to on other respected sources or websites?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source?

Accuracy In this test we attempt to determine the reliability and accuracy of the content of the website. You need to determine if you can trust the information presented in the website or is it just slanted, personal beliefs.

- Where does the information in the website come from?

- Is the information supported by Evidence, or is it just opinion?

- Has the information presented been reviewed by qualified sources?

- Can you verify any of the content in another source or personal knowledge?

- Are there statements in the website you know to be false?

- Does the language or tone used in the website appear unbiased or free of emotion or loaded language?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors in the content of the website?

Purpose Finally we examine the purpose of the website. We need to determine if the website was created to inform, entertain or even sell a product or service. If we want accurate, high quality evidence, we would want to avoid a site that is trying to sell us something. Although a company selling solar power may have some factual information about solar energy on their site, the site is geared to sell you their product. The information they provide is not there to educate you with all aspects of solar power.

- What is the purpose of the content of this website? Is the purpose to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors of the website make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the content in the website considered facts, opinion, or even propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Does the author omit important facts or data that might disprove the claim being made in the post?

- Are alternative points of view presented?

- Does the content of the website contain political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

Questions used here are inspired from questions from the Meriam Library at California State University Chico, the University of Maryland University College Library and Creighton University Library

- Rieke, Richard D. and Malcolm Sillars. Argumentation and Critical Decision Making. (New York: HaperCollins Rhetoric and Society Series, 1993)

- Shenk, David. Data Smog, Surviving the Information Glut. 1. San Fransisco: HarperEdge, 1997

- Ithica College, "Primary and Secondary Sources," libguides.ithaca.edu/research101/primary (accessed October 31, 2019)

- ARGUMENTATION AND ADVOCACY. By Russel R. Windes and Arthur Hastings. New York: Random House, 1965

- Patterson, J. W. and David Zarefsky. Contemporary Debate. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Legal Concept of Evidence

The legal concept of evidence is neither static nor universal. Medieval understandings of evidence in the age of trial by ordeal would be quite alien to modern sensibilities (Ho 2003–2004) and there is no approach to evidence and proof that is shared by all legal systems of the world today. Even within Western legal traditions, there are significant differences between Anglo-American law and Continental European law (see Damaška 1973, 1975, 1992, 1994, 1997). This entry focuses on the modern concept of evidence that operates in the legal tradition to which Anglo-American law belongs. [ 1 ] It concentrates on evidence in relation to the proof of factual claims in law. [ 2 ]

It may seem obvious that there must be a legal concept of evidence that is distinguishable from the ordinary concept of evidence. After all, there are in law many special rules on what can or cannot be introduced as evidence in court, on how evidence is to be presented and the uses to which it may be put, on the strength or sufficiency of evidence needed to establish proof and so forth. But the law remains silent on some crucial matters. In resolving the factual disputes before the court, the jury or, at a bench trial, the judge has to rely on extra-legal principles. There have been academic attempts at systematic analysis of the operation of these principles in legal fact-finding (Wigmore 1937; Anderson, Schum, and Twining 2009). These principles, so it is claimed, are of a general nature. On the basis that the logic in “drawing inferences from evidence to test hypotheses and justify conclusions” is governed by the same principles across different disciplines (Twining and Hampsher-Monk 2003: 4), ambitious projects have been undertaken to develop a cross-disciplinary framework for the analysis of evidence (Schum 1994) and to construct an interdisciplinary “integrated science of evidence” (Dawid, Twining, and Vasilaki 2011; cf. Tillers 2008).

While evidential reasoning in law and in other contexts may share certain characteristics, there nevertheless remain aspects of the approach to evidence and proof that are distinctive to law (Rescher and Joynt 1959). Section 1 (“conceptions of evidence”) identifies different meanings of evidence in legal discourse. When lawyers talk about evidence, what is it that they are referring to? What is it that they have in mind? Section 2 (“conditions for receiving evidence”) approaches the concept of legal evidence from the angle of what counts as evidence in law. What are the conditions that the law imposes and must be met for something to be received by the court as evidence? Section 3 (“strength of evidence”) shifts the attention to the stage where the evidence has already been received by the court. Here the focus is on how the court weighs the evidence in reaching the verdict. In this connection, three properties of evidence will be discussed: probative value, sufficiency, and degree of completeness.

1. Conceptions of Evidence: What does Evidence Refer to in Law?

2.1.1 legal significance of relevance, 2.1.2 conceptions of logical relevance, 2.1.3 logical relevance versus legal relevance, 2.2 materiality and facts-in-issue, 2.3.1 admissibility and relevance, 2.3.2 admissibility or exclusionary rules, 3.1 probative value of specific items of evidence, 3.2.1 mathematical probability and the standards of proof, 3.2.2 objections to using mathematical probability to interpret standards of proof, 3.3 the weight of evidence as the degree of evidential completeness, other internet resources, related entries.

Stephen (1872: 3–4, 6–7) long ago noted that legal usage of the term “evidence” is ambiguous. It sometimes refers to that which is adduced by a party at the trial as a means of establishing factual claims. (“Adducing evidence” is the legal term for presenting or producing evidence in court for the purpose of establishing proof.) This meaning of evidence is reflected in the definitional section of the Indian Evidence Act (Stephen 1872: 149). [ 3 ] When lawyers use the term “evidence” in this way, they have in mind what epistemologists would think of as “objects of sensory evidence” (Haack 2004: 48). Evidence, in this sense, is divided conventionally into three main categories: [ 4 ] oral evidence (the testimony given in court by witnesses), documentary evidence (documents produced for inspection by the court), and “real evidence”; the first two are self-explanatory and the third captures things other than documents such as a knife allegedly used in committing a crime.

The term “evidence” can, secondly, refer to a proposition of fact that is established by evidence in the first sense. [ 5 ] This is sometimes called an “evidential fact”. That the accused was at or about the scene of the crime at the relevant time is evidence in the second sense of his possible involvement in the crime. But the accused’s presence must be proved by producing evidence in the first sense. For instance, the prosecution may call a witness to appear before the court and get him to testify that he saw the accused in the vicinity of the crime at the relevant time. Success in proving the presence of the accused (the evidential fact) will depend on the fact-finder’s assessment of the veracity of the witness and the reliability of his testimony. (The fact-finder is the person or body responsible for ascertaining where the truth lies on disputed questions of fact and in whom the power to decide on the verdict vests. The fact-finder is also called “trier of fact” or “judge of fact”. Fact-finding is the task of the jury or, for certain types of cases and in countries without a jury system, the judge.) Sometimes the evidential fact is directly accessible to the fact-finder. If the alleged knife used in committing the crime in question (a form of “real evidence”) is produced in court, the fact-finder can see for himself the shape of the knife; he does not need to learn of it through the testimony of an intermediary.

A third conception of evidence is an elaboration or extension of the second. On this conception, evidence is relational. A factual proposition (in Latin, factum probans ) is evidence in the third sense only if it can serve as a premise for drawing an inference (directly or indirectly) to a matter that is material to the case ( factum probandum ) (see section 2.2 below for the concept of materiality). The fact that the accused’s fingerprints were found in a room where something was stolen is evidence in the present sense because one can infer from this that he was in the room, and his presence in the room is evidence of his possible involvement in the theft. On the other hand, the fact that the accused’s favorite color is blue would, in the absence of highly unusual circumstances, be rejected as evidence of his guilt: ordinarily, what a person’s favorite color happens to be cannot serve as a premise for any reasonable inference towards his commission of a crime and, as such, it is irrelevant (see discussion of relevance in section 2.1 below). In the third sense of “evidence”, which conceives of evidence as a premise for a material inference, “irrelevant evidence” is an oxymoron: it is simply not evidence. Hence, this statement of Bentham (1825: 230): [ 6 ]

To say that testimony is not pertinent, is to say that it is foreign to the case, has no connection with it, and does not serve to prove the fact in question; in a word, it is to say, that it is not evidence.