- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 December 2019

Top research priorities for preterm birth: results of a prioritisation partnership between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals

- Sandy Oliver 1 ,

- Seilin Uhm 1 ,

- Lelia Duley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6721-5178 2 ,

- Sally Crowe 3 ,

- Anna L. David 4 ,

- Catherine P. James 4 ,

- Zoe Chivers 5 ,

- Gill Gyte 6 ,

- Chris Gale 7 ,

- Mark Turner 8 ,

- Bev Chambers 9 ,

- Irene Dowling 10 ,

- Jenny McNeill 11 ,

- Fiona Alderdice 12 ,

- Andrew Shennan 13 &

- Sanjeev Deshpande 14

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 19 , Article number: 528 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

6179 Accesses

18 Citations

67 Altmetric

Metrics details

We report a process to identify and prioritise research questions in preterm birth that are most important to people affected by preterm birth and healthcare practitioners in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland.

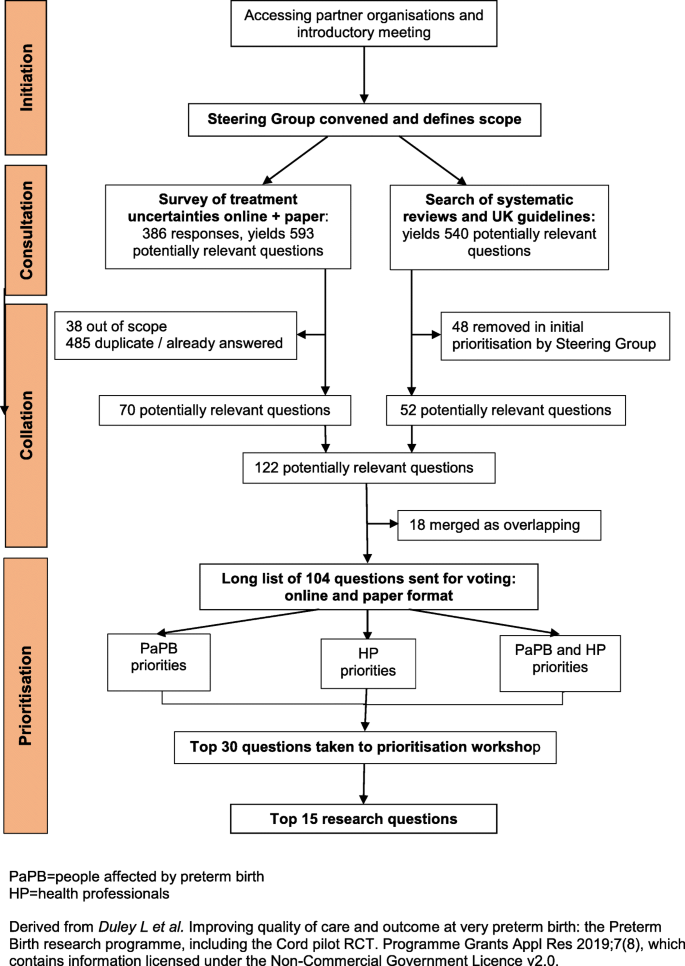

Using consensus development methods established by the James Lind Alliance, unanswered research questions were identified using an online survey, a paper survey distributed in NHS preterm birth clinics and neonatal units, and through searching published systematic reviews and guidelines. Prioritisation of these questions was by online voting, with paper copies at the same NHS clinics and units, followed by a decision-making workshop of people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals.

Overall 26 organisations participated. Three hundred and eighty six people responded to the survey, and 636 systematic reviews and 12 clinical guidelines were inspected for research recommendations. From this, a list of 122 uncertainties about the effects of treatment was collated: 70 from the survey, 28 from systematic reviews, and 24 from guidelines. After removing 18 duplicates, the 104 remaining questions went to a public online vote on the top 10. Five hundred and seven people voted; 231 (45%) people affected by preterm birth, 216 (43%) health professionals, and 55 (11%) affected by preterm birth who were also a health professional. Although the top priority was the same for all types of voter, there was variation in how other questions were ranked.

Following review by the Steering Group, the top 30 questions were then taken to the prioritisation workshop. A list of top 15 questions was agreed, but with some clear differences in priorities between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

These research questions prioritised by a partnership process between service users and healthcare professionals should inform the decisions of those who plan to fund research. Priorities of people affected by preterm birth were sometimes different from those of healthcare professionals, and future priority setting partnerships should consider reporting these separately, as well as in total.

Peer Review reports

Preterm birth has major impacts on survival, quality of life, psychosocial and emotional stress on the family, and costs for health services [ 1 ]. Improving outcome for these vulnerable babies and their families is a priority, and prioritising research questions is advocated as a pathway to achieve this [ 2 , 3 ].

Traditionally the research agenda has been determined primarily by researchers, either in academia or industry, who have used processes for priority setting that lack transparency [ 4 , 5 ]. This has contributed to a mismatch between the available research evidence and the research preferences of patients and members of the public, and of clinicians [ 6 , 7 ]. Often, research does not address the questions about treatments that are of greatest importance to patients, their carers and practising clinicians [ 5 , 8 ]. The James Lind Alliance has developed methods for establishing priority setting partnerships between patient organisations and clinician organisations, which then identify and prioritise treatment uncertainties in order to inform publicly funded research [ 9 , 10 ]. These methods have been used for a range of health conditions [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

We report the outcomes of a process to identify and prioritise research questions in preterm birth that are most important to people affected by preterm birth and healthcare practitioners in the United Kingdom and Ireland using methods established by the James Lind Alliance [ 18 ]. This partnership differed from previous priority setting partnerships supported by the James Lind Alliance in that pregnancy is not an illness or disease, and that it involves at least two people (mother and child); in addition preterm birth can have life-long consequences for them, their families and for the health services and society. Our aim was first to identify unanswered questions about the prevention and treatment of preterm birth from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers. Then to prioritise those questions that people affected by preterm birth and clinicians agree are the most important.

The Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership was convened in November 2011, following an introductory meeting in July 2011. The partnership followed the four stages of the James Lind Alliance process (see Fig. 1 ) [ 9 ].

Flow chart of the JLA Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership

Organisations whose areas of interest included preterm birth were informed about the priority setting partnership and invited to participate in, or contribute to, the introductory workshop. Those who then joined the partnership are listed in Box 1. All participating organisations were asked to complete a declaration of interests, including disclosure of relationships with the pharmaceutical or medical devices industry. Subsequently a Steering Group was convened, with members of participating organisations who volunteered to take on this role. This group was chaired by a representative from the James Lind Alliance (SC).

At the introductory workshop it was clear that many participants felt the scope of the partnership should be wider than was initially envisaged. Additional topics proposed for inclusion in the scope were uncertainties about the causes of preterm birth, about the prognosis following being born preterm, and about treatments long before birth. As widening the scope too far would risk leaving the prioritisation unachievable within a reasonable time frame and the existing resources, the Steering Group decided the scope would be restricted to uncertainties about treatments, to interventions during pregnancy and around the time of birth or shortly afterwards (taken up to the time of hospital discharge for the baby after birth).

Consultation to gather research questions (treatment uncertainties)

Research questions were gathered from people affected by preterm birth, clinicians and researchers, using methods developed by the James Lind Alliance [ 10 ]. First, a survey was distributed on-line, including through partner organisations, to ask for suggestions about preterm birth experiences, services or treatments which needed to be researched, and why the research would be important (see Additional file 1 for paper version of this survey). Respondents were asked to say if they were people with personal or family experiences of preterm birth, and/or if they were a health professional.

At an interim review of demographic data about home ownership and ethnicity from this survey there was concern that the respondents were not representative of the population at risk of preterm birth. To try and access a more high risk group, paper copies of the survey (see Additional file 1 ) were distributed at high risk specialist prematurity antenatal clinics at two tertiary level hospitals (University College London Hospital and Queen’s Medical Centre Nottingham), and to parents visiting their babies in three level 3 neonatal intensive care units (University College London Hospital and Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London; Liverpool Women’s Hospital) between March and December 2012. The survey closing date was extended to allow time to implement these changes. Respondents were invited to provide an email address to be notified about voting to prioritise the questions.

In addition, research questions were identified from systematic reviews of existing research and from national UK clinical guidelines (see Additional file 2 ).

Collation - checking and combining research questions

With support from an independent information specialist, submissions from the survey were formatted into research questions, which were checked against existing reviews and guidelines. Those already answered were removed. The remaining research questions were screened by the Steering Group, to remove those answered by a subsequent randomised trial or for which a large randomised trial was in progress, and those that were out of scope or unclear, and to combine similar research questions. This left the final long list of unanswered research questions which was sorted into similar categories, ordered chronologically from before pregnancy to hospital discharge following birth.

Prioritisation of the research questions

Prioritisation was by a two-stage process using a modified Delphi with individual voting, followed by a face-to-face workshop using nominal group technique [ 10 ]. First, the long list of unanswered research questions was made available online for public voting (from September to December 2013), with paper copies distributed to the same high risk antenatal clinics and neonatal units. Respondents were asked to pick the 10 they considered most important. Overall results and results by stakeholder group (people affected by preterm birth, health professional) were reviewed by the Steering Group to remove remaining repetition or overlap between questions. The final shortlist of 30 unanswered research questions to go forward to the prioritisation workshop was then agreed.

The aims of the prioritisation workshop were to agree a ranking for the short list, including the ‘top10’, and to consider next steps to ensure that the priorities are taken forward for research funding. Participants were invited from across the partnership, and included representatives from organisations representing both people affected by preterm birth and clinicians, parents of babies born preterm, and adults who were born preterm. Prior to the workshop, participants were sent the shortlist of unanswered research questions.

At the workshop (held in January 2014), after an introductory session participants were assigned to one of four small groups, each with a facilitator, to discuss ranking for each uncertainty. Groups were pre-specified in advance to include a mix of parents, people born preterm, clinicians and other health professionals. The groups were provided with a set of 30 large cards, each printed with one shortlisted research question. On the reverse were examples of wording from the original submissions, and a breakdown of how people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals had scored that question in their voting. Following discussion, these cards were placed in ranked order. Over the lunchtime break, rankings from the four groups were aggregated into a single ranking order. These aggregate rankings were presented at a plenary session, to demonstrate where there was existing consensus between groups, and where there were differences. Participants were then reconvened into three small groups, again pre-planned so each had a new mix of participants and retained a balance of backgrounds, to discuss the aggregate ranking. Similar processes were used as in the earlier small groups, with the aim of agreeing the top ten research questions and ranking all 30 questions. Aggregated ranking from the three small groups was taken to a final plenary session, with the 30 cards laid out on the floor in ranked order. Participants then debated and agreed the final ranking.

Forty two organisations were approached and invited to participate in the priority setting partnership (see Additional file 4 ); of these 25 accepted and joined the partnership (see Table 1 ). Ten organisations were represented on the Steering Group; four representing those affected by preterm birth, and six representing health professionals (obstetricians and neonatologists). Some Steering Group members were parents of infants born preterm, or had themselves been born preterm. The group also included four non-voting members: two researchers who co-ordinated the prioritisation partnership, one a clinical academic with a background in obstetrics and the other with expertise in public engagement in research; one charity representative, and one PhD student.

When the online survey closed it had been accessed by 1076 people, and completed by 349; an additional 37 paper survey forms were completed and returned. Hence a total of 386 people responded of whom 204 (53%) said that they were affected by preterm birth, 107 (28%) that they were health professionals, 43 (11%) that they were both affected by preterm birth and a health care professional, and 32 (8%) did not answer this question (Table 2 ). Of the 247 respondents affected by preterm birth, most 186 (75%) reported they were parents of a preterm baby, but some were grandparents and other family members.

The 386 responses contained 593 potential research questions. Submissions were formatted into research questions, with similar submission combined into one question (see Additional file 5 ), and screened to remove those already answered, out of scope or unclear, (see Additional file 6 ). Thirty eight submissions were removed as being outside the scope of this process. After merging similar questions and removing those that were fully answered, 70 unanswered questions were left from the survey.

The search of systematic reviews and clinical guidelines identified 540 potentially relevant questions. As there was such a large number, the Steering Group agreed a process to prioritise which would go forward to the next stage. Each member was asked to select the 60 questions from systematic reviews they considered to be most relevant and important. They then brought their list of 60 to a face-to-face meeting at which questions were only considered as potential priorities for the voting stage if they were supported by three or more members. This resulted in 28 questions from systematic reviews and 24 from clinical guidelines remaining in the process. Overall there were then 122 questions; as 18 of these overlapped with other questions, they were merged to give a final ‘long list’ of 104 unanswered research questions (see Additional file 3 ).

The 104 questions on the long list were sent for an online public vote, with paper copies distributed to the same high risk antenatal clinics and neonatal units. Overall 507 people voted (448 online and 59 on paper); 231 (45%) said they had been affected by preterm birth, 216 (43%) that they were a health professional, and 55 (11%) that they were affected by preterm birth and also a health professional (Table 2 ). Type of respondent was not known for 5 (1%) voters. Of the 271 who said they were a health professional (including those who had been affected by preterm birth themselves), 85 said they were an obstetrician, 51 a nurse, 44 a neonatologist, 24 a midwife, 4 a general practitioner, 32 were other health professionals and 31 preferred not to say. Of those who voted, 512 (87%) reported their ethnicity as white, and ethnicity was not known for 8 (2%). Responses were received from the four nations within the United Kingdom, and from the Republic of Ireland.

For public voting, the top priority (which treatments (including diagnostic tests) are most effective to predict or prevent preterm birth?) was the same for all three types of respondent (Table 3 ), but there was considerable variation in how other questions were ranked. Several questions were in the overall top 10 for only one type of voter. Questions ranked 1–40 in the public vote were reviewed by the Steering Group, taking into account the voting preferences of people affected by preterm birth and the overall balance of the topics. Four questions were removed: one had already been answered, one was being addressed by an ongoing trial, and two were merged with another broader question (all three being about infant feeding). A shortlist of the top 30 questions was then taken forward to the prioritisation workshop (Table 4 ).

The workshop to prioritise these 30 questions was attended by 34 participants; 13 parents or adults who had been born preterm and 21 health professions (neonatology, obstetrics, midwifery, speech therapy and psychology). Several of the health professionals also had personal experience of preterm birth. In addition, there were four facilitators (two from the James Lind Alliance and two non-voting members of the Steering Group), five observers (one from the James Lind Alliance, one from a research funding organisation in Canada, one from the Institute of Education University of London, and two who were non-voting members of the Steering Group).

During the prioritisation workshop, two questions were merged as it was agreed they overlapped, and the wording of a few others was modified for clarification. Following the first round of small group discussion, there was considerable variation in the top priorities between the four groups. Following the second round of small group discussion there was agreement about the top few priorities. During the final plenary discussion about the aggregated ranking there was consensus about the top seven questions, less consensus about the next three, and disagreement about those ranked as between 10 and 20. As it was not possible to achieve consensus about the top 10 questions within the timeframe, a proposal to expand this to a top 15 was agreed. Consensus about the top 15 was then achieved (Table 4 ). This top 15 had some significant differences to the ranking following public voting. The most noticeable was two questions ranked 18 (How do stress, trauma and physical workload contribute to the risk of preterm birth, are there effective ways to reduce those risks and does modifying those risks alter outcome?) and 26 (What treatments can predict reliably the likelihood of subsequent infants being preterm?) at the workshop were ranked 3 and 4 respectively in the overall public vote, and 2 and 3 by service users in the public vote (Table 3 ).

The unanswered research questions relevant to preterm birth identified during this process were prioritised in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland by people affected by preterm birth (parents, grandparents, adults who were born preterm, and others affected by preterm birth), by a range of health professionals, and by people who were both personally affected by preterm birth and a health professional. To our knowledge this is the first such process in preterm birth. People affected by preterm birth and health professionals had many shared priorities, but our process demonstrates that on some questions they have different perspectives. Priorities may also change over time and in different settings, Hence, although the top research priorities from this process should be considered by those who plan and fund research in this area, the full list of 104 unanswered questions is also relevant to decision-making about research funding. This is particularly true if we wish to make research more relevant to those whose lives have been affected by preterm birth, and the healthcare workers who care for them.

While several of the top priorities for research are broad topics already well recognised as important, such as what is the optimum milk feeding regimen for preterm infants and prevention of infection, others are indicative of areas previously underrepresented in research; for example packages of care to support families after discharge, and what is the role of stress, trauma and physical workload in the risk of preterm birth, and are there effective ways to reduce this risk and does this influence outcome. This is in keeping with findings from previous James Lind Alliance partnerships, which suggests and highlights the value of partnership and shared decision making with an inclusive stakeholder group with balanced representation of service users and clinicians [ 7 ].

In line with the literature on consensus development [ 19 ], the strengths of this Preterm Birth Priority Setting Partnership include the large numbers of participants in the process, the range of stakeholders involved, the formality of the processes, the use of facilitators for face-to-face debate to ensure that all options were discussed and all participants had a chance to voice their views, providing feedback and repeating the judgment, and ensuring that judgements were made confidentially. The first three features applied to both the consultation and the workshop; the last applied only to the consultation. The change in priorities between the survey and the workshop deserves further investigation. Although the choice of individuals within the professional groups represented is unlikely to have made a difference to the priorities, [ 20 ] difference in status across workshop participants may have [ 19 ].

Preterm birth is associated with factors such as lower socio-economic status, ethnicity (such as African origin), and maternal age (being lower than 18 years or above 35 years) [ 21 ]. Despite implementing strategies to reach a more representative population, our respondents remained primarily white and with a relatively high proportion of homeowners, hence not representative of the population affected by preterm birth. This could limit generalisablity of these priorities to other populations. A wide range of relevant health professionals participated in the public voting, including neonatologists, obstetricians, neonatal nurses, midwives, speech and language therapists, psychologists and general practitioners; strengthening generalisablity.

Maintaining balanced representation between people affected by preterm birth and the different groups of health professionals for the final prioritisation workshop was challenging. This may have had implications for the final decisions, as happens in guideline development, where consensus development research concludes that differences in how groups are constituted (but not individual members) leads to different decisions [ 22 ]. At our workshop differences in priorities between the various professional groups contributed to the difficulty in achieving consensus for a top 10 list, and to the two ‘lost priorities’ which although ranked in the top 5 at the public vote were not included in the final top 15. The difficulty in agreeing a top 10 underlines the complexity of priority setting for research, particularly for topics such as preterm birth, which involve mother and baby, as well as their wider family. This complexity, and the differing priorities of different stakeholders, make it important to publicise the top 30 list, and the full long list of 104 questions, as well as the top 15 priorities [ 23 ].

Large changes in ranking following the public vote and the final prioritisation appeared to be related to difficulty in the perspective of people affected by preterm birth being heard in the large group session, and an imbalance between the different priorities of two key types of health professional (neonatologists and obstetricians). This was further complicated by fewer obstetricians than expected attending the workshop, and by some of the healthcare professionals also being researchers. Another element of our work, reported in detail elsewhere, was a nested observational study of how service users and healthcare professionals interact when making collective decisions about research priorities [ 24 ]. This suggested that health care professionals and service users tended to use different pathways for persuasion in a group discussion, and communication patterns depended on the stage of group development. The Steering Group had worked together for some time, and when new participants joined for the workshop communication patterns returned to an earlier stage. This may have influenced quality of the consensus.

Reporting of the process for prioritisation is therefore important for transparency, and to identify ways to improve it. Future prioritisation processes, particularly those with a similar wide range of healthcare professionals, should endeavour to anticipate potential different perspectives and mitigate any imbalance where possible, and should report voting separately by ‘service users’ and healthcare professionals. Similarly, whilst it may be appropriate to include healthcare professionals who are also researchers in prioritisation, this potential conflict of interest should be declared and taken into account.

This priority setting was limited to the United Kingdom and Ireland, and is therefore most readily generalisable to settings with a similar population and health system. Previous research prioritisation processes for preterm birth [ 3 , 25 ] did not include people affected by preterm birth and were for low and middle income settings. The most recent neonatal prioritisation exercise in the UK did not include people affected by preterm birth and considered only medicines for neonates [ 26 ]. Although unanswered research questions are universal, prioritisation of these questions depends on the local values, context and setting. Nevertheless, there are common priorities across these different settings and our prioritisation process in the UK, such as prevention of preterm birth, postnatal infection and lung damage.

Failure to take account of the views of users of research (i.e. clinicians and the patients who look to them for help) contributes to research waste [ 27 ]. James Lind Alliance priority setting partnerships brings together ‘patients, carers and clinicians’ to identify unanswered research questions and to agree a list of the top priorities, ( http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/about-the-james-lind-alliance/about-psps.htm ) which can then shape the health research agenda [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The aim is to ensure that those who fund health research, and also those who support and conduct research, are aware of what really matters to both patients and clinicians. In our priority setting partnership, people affected by preterm birth and the different groups of health care professionals had different priorities. This underlines the importance of this paper presenting the full list of 30 questions taken forward to the prioritisation workshop, and the respective priorities of people affected by preterm birth and health professionals, as well as the long list of 104 unanswered questions sent out for public voting.

We present the top 30 unanswered research questions identified and prioritised by the priority setting partnership, along with the full list of 104 questions. These include treatment and prevention as well as how care should be organised and staff training. They should be publicised to the public, to research funders and commissioners, and to those who support and conduct research.

People affected by preterm birth and health professionals sometimes had different priorities. Future priority setting partnerships should consider reporting the priorities of service users and healthcare professionals separately, as well as in total. Those with a wide range of healthcare professionals involved should anticipate potential different perspectives and mitigate any imbalance where possible. Healthcare professionals who are also researchers should declare this potential conflict before participating in prioritisation, so that it can be taken into account.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):261–9.

Article Google Scholar

Delivering action on preterm births. Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1610.

Lackritz EM, Wilson CB, Guttmacher AE, Howse JL, Engmann CM, Rubens CE, Mason EM, Muglia LJ, Gravett MG, Goldenberg RL, et al. A solution pathway for preterm birth: accelerating a priority research agenda. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e328–30.

Chalmers I. The perinatal research agenda: whose priorities? Birth. 1991;18(3):137–41 discussion 142-135.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Chalmers I. Well informed uncertainties about the effects of treatments: how should clinicians and patients respond? BMJ. 2004;328:475–6.

Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet. 2000;355(9220):2037–40.

Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, Cowan K, Chalmers I. Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. BMC Res Involve Engage. 2015;1:2.

Partridge N, Scadding J. The James Lind Alliance: patients and clinicians should jointly identify their priorities for clinical trials. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1923–4.

Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind Alliance guidebook: James Lind Alliance; 2012. http://www.jlaguidebook.org/

The James Lind Alliance Guidebook. Version 8 2018 [ http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/ ]. Accessed Dec 2019.

Fernandez MA, Arnel L, Gould J, McGibbon A, Grant R, Bell P, White S, Baxter M, Griffin X, Chesser T, et al. Research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e023301.

Kelly S, Lafortune L, Hart N, Cowan K, Fenton M, Brayne C, On behalf of the Dementia Priority Setting, Partnership. Dementia priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance: using patient and public involvement and the evidence base to inform the research agenda. Age Ageing. 2015;44(6):985–93.

Layton A, Eady EA, Peat M, Whitehouse H, Levell N, Ridd M, Cowdell F, Patel M, Andrews S, Oxnard C, et al. Identifying acne treatment uncertainties via a James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e008085.

Deane KH, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, Pascoe R, Penhale B, Clarke CE, Sackley C, Storey S. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson's disease. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006434.

Hollis C, Sampson S, Simons L, Davies EB, Churchill R, Betton V, Butler D, Chapman K, Easton K, Gronlund TA, et al. Identifying research priorities for digital technology in mental health care: results of the James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(10):845–54.

Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, Firkins L. Top ten research priorities relating to life after stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(3):209.

Horne AW, Saunders PTK, Abokhrais IM, Hogg L, Endometriosis Priority Setting Partnership Steering G. Top ten endometriosis research priorities in the UK and Ireland. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2191–2.

Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins DL, Chameides L, Goldsmith JP, Guinsburg R, Hazinski MF, Morley C, Richmond S, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):e1319–44.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, Marteau T. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):i-iv):1–88.

Hutchings A, Raine R. A systematic review of factors affecting the judgments produced by formal consensus development methods in health care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(3):172–9.

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84.

Hutchings A, Raine R, Sanderson C, Black N. A comparison of formal consensus methods used for developing clinical guidelines. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(4):218–24.

Duley L, Uhm S, Oliver S, on behalf of the Steering Group. Top 15 UK research priorities for preterm birth. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2041–2.

Duley L, Dorling J, Ayers S, et al. Improving quality of care and outcome at very preterm birth: the Preterm Birth research programme, including the Cord pilot RCT. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Sep. (Programme Grants for Applied Research, No. 7.8.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547087/ . https://doi.org/10.3310/pgfar07080 .

Bahl R, Martines J, Bhandari N, Biloglav Z, Edmond K, Iyengar S, Kramer M, Lawn JE, Manandhar DS, Mori R, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from preterm birth and low birth weight by 2015. J Glob Health. 2012;2(1):010403.

Turner MA, Lewis S, Hawcutt DB, Field D. Prioritising neonatal medicines research: UK medicines for children research network scoping survey. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:50.

Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Gulmezoglu AM, Howells DW, Ioannidis JP, Oliver S. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):156–65.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to all the organisations which contributed to the partnership, to all the people who responded to our survey and voting, and to the participants in the final workshop. Thanks also to Ann Daly, Drew Davy, Elizabeth Oliver and Claire Stansfield for their help with the systematic reviews.

This paper presents work funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG- 0609-10107). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. ALD is supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. During this work CG was funded by the NIHR as a Clinical Lecturer and an Academy of Medical Sciences Starter Grant for Clinical Lecturers, supported by the Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, British Heart Foundation, Arthritis Research UK, Prostate Cancer UK and The Royal College of Physicians.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, 18 Woburn Square, London, WH10NR, UK

Sandy Oliver & Seilin Uhm

Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Lelia Duley

Crowe Associates Ltd, Thame, UK

Sally Crowe

Institute for Women’s Health, University College London, 86-96 Chenies Mews, London, WC1E 6HX, UK

Anna L. David & Catherine P. James

Bliss, London., UK

Zoe Chivers

National Childbirth Trust (NCT), 30 Euston Square, London, NW1 2FB, UK

Neonatal Medicine, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital campus, London, SW10 9NH, UK

Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Mark Turner

Bev Chambers

Irene Dowling

School of Nursing & Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast, Medical Biology Centre, Belfast, BT9 7BL, UK

Jenny McNeill

National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Old Road Campus, Headington, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK

Fiona Alderdice

Kings College London, St. Thomas Hospital, London, SE1 7EH, UK

Andrew Shennan

Sanjeev Deshpande, Princess Royal Hospital, Apley Castle, Grainger Drive, Telford, TF1 6TF, UK

Sanjeev Deshpande

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors were members of the Steering Group, and so planned the study, and reviewed data. SC chaired the Steering Group, and the final workshop. SU conducted the survey, managed the voting, and analysed the data. LD drafted the paper, with feedback from all authors. All authors agree the final draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lelia Duley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Research Ethics Committee approval for the whole priority setting exercise was obtained from the Institute of Education, University of London (reference FCL 318), and for distribution of paper versions of the survey and voting was from the North Wales REC (Central & East) Research Ethics Committee (reference 12 /WA/0286). Forms for both the survey of uncertainties and voting were self-completed, and consent was assumed if the form was completed and submitted (online) or returned (paper version). Consent for public surveys of this type of was not required by the NHS research ethics committees. For the nested qualitative study, consent to sound record meetings was given verbally by members of the steering group and the workshop participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

Survey form.

Additional file 2.

Mapping systematic reviews.

Additional file 3.

Long list of questions sent for voting.

Additional file 4.

Organisations invited to participate.

Additional file 5.

Submissions formatted as research questions.

Additional file 6.

Reasons for excluding submissions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Oliver, S., Uhm, S., Duley, L. et al. Top research priorities for preterm birth: results of a prioritisation partnership between people affected by preterm birth and healthcare professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19 , 528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2654-3

Download citation

Received : 01 May 2018

Accepted : 29 November 2019

Published : 30 December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2654-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Women’s lived experiences of preterm birth and neonatal care for premature infants at a tertiary hospital in Ghana: A qualitative study

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, Ghana, Holy Care Specialist Hospital, Accra, Ghana, Julius Global Health, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Holy Care Specialist Hospital, Accra, Ghana

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Julius Global Health, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Child Health, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, Ghana

- Kwame Adu-Bonsaffoh,

- Evelyn Tamma,

- Adanna Uloaku Nwameme,

- Martina Mocking,

- Kwabena A. Osman,

- Joyce L. Browne

- Published: December 1, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001303

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Preterm birth is a leading cause of death in children under five and a major public concern in Ghana. Women’s lived experiences of care following preterm birth in clinical setting represents a viable adjunctive measure to improve the quality of care for premature infants. This qualitative study explored the knowledge and experiences of women who have had preterm birth and the associated challenges in caring for premature infants at a tertiary hospital. A qualitative design using in-depth interviews (IDIs) was conducted among women who experienced preterm birth with surviving infants at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, Ghana. A thematic content analysis using the inductive analytic framework was undertaken using Nvivo. Thirty women participated in the study. We observed substantial variation in women’s knowledge on preterm birth: some women demonstrated significant understanding of preterm delivery including its causes such as hypertension in pregnancy, and potential complications including neonatal death whilst others had limited knowledge on the condition. Women reported significant social and financial challenges associated with preterm birth that negatively impacted the quality of postnatal care they received. Admission of preterm infants at the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) generated enormous psychological and emotional stress on the preterm mothers due to uncertainty associated with the prognosis of their babies, health system challenges and increased cost. Context-specific recommendations to improve the quality of care for prematurely born infants were provided by the affected mothers and include urgent need to expand the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) coverage and more antenatal health education on preterm birth. Mothers of premature infants experienced varied unanticipated challenges during the care for their babies within the hospital setting. While knowledge of preterm birth seems adequate among women, there was a significant gap in the women’s expectations of the challenges associated with the care of premature infants of which the majority experience psychosocial, economic and emotional impact.

Citation: Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Tamma E, Nwameme AU, Mocking M, Osman KA, Browne JL (2022) Women’s lived experiences of preterm birth and neonatal care for premature infants at a tertiary hospital in Ghana: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(12): e0001303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001303

Editor: Rachel Hall-Clifford, Emory University, UNITED STATES

Received: March 30, 2022; Accepted: October 28, 2022; Published: December 1, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Adu-Bonsaffoh et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: This study was supported by the UMC Utrecht Global Health Fellowship in the form of an award to KAB. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is the leading cause of death in children under five worldwide [ 1 ] and a major public health challenge worldwide [ 2 – 4 ]. The World Health Organization defines preterm birth as a childbirth that occurs before 37 weeks of gestation or less than 259 days from the first day of the last menstrual period [ 2 ]. Globally, about 15 million babies are born premature every year and more than one million of them die immediately after their birth [ 2 ]. Although preterm birth is a global phenomenon, the main burden of the resulting prematurity is far higher in low and middle- income countries (LMIC), with approximately 80% occurring in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [ 2 , 5 ]. In Ghana, a country in sub-Saharan Africa, the second leading cause of death among children under five is prematurity with a national rate of 14.5% [ 6 ]. Annually, more than 100,000 premature babies are born in the country with direct complications of preterm birth contributing to approximately 8,200 under five child deaths [ 6 ].

In the effort to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3: to eliminate preventable neonatal and under-5 mortalities, the burden of preterm births needs a global attention. Preterm babies are at risk of major health complications such as respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, feeding difficulties, vision and hearing impairment, learning disabilities and chronic lung disease [ 7 ]. Preterm infants usually require specialized care with prolonged hospitalization resulting in an increased psychological stress and financial burden on affected families [ 8 , 9 ]. The etiology of spontaneous PTB still remains unclear and provider-initiated preterm phenotype has varied causal associations [ 7 ]. Known common risk factors for preterm birth include multiple gestation, infection and chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension (pre-eclampsia), preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM), advanced maternal age and low socio-economic status [ 7 , 10 , 11 ].

Recently, the WHO highlighted evidence-based interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes as part of the global effort of reducing child mortality [ 12 ]. A recent systematic review on evidence-based intervention to reduce mortality among preterm and low birth weight neonates identified additional useful interventions such as cord and skin cleansing with chlorhexidine [ 13 ]. In addition to the recommendations that focus on the clinical provision of care, a better understanding of the plight of the preterm mothers and their lived experiences of care at the facility level can inform optimal implementation of these interventions. While some research exists from various settings that indicate that preterm birth women experience major challenges across the continuum of antenatal, intrapartum, postpartum and newborn care, studies from sub-Saharan Africa are limited [ 14 ].

In Ghana, there is limited research on preterm birth in general resulting in inadequate evidence to inform policy optimally [ 14 ]. More specifically, there is limited qualitative research to better understand the social, psychological and clinical challenges associated with preterm birth and the care for the preterm infants. Given the high prevalence of preterm birth in Ghana accompanied by increased maternal psychological and financial burden, the lived experiences of these mothers are vital in shaping the quality of care for the mothers and their premature infants. There is evidence that an individual’s knowledge about a health condition can influence early seeking of medical care, and can prevent (further) complications [ 15 ], improve compliance to treatment [ 16 ] and maternal and newborn’s health outcomes and care experiences. Therefore, this paper explores the knowledge and lived experiences of women who have experienced preterm birth and the associated challenges in caring for premature infants at a tertiary hospital.

Study design and sites

This was a qualitative phenomenological study, using in-depth interviews (IDIs), conducted to gain comprehensive understanding of the women’s knowledge on preterm birth including its causes and associated complications and their lived experiences of care. The study was carried out at the Maternity Unit of the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH) in Accra from August 2019 to January 2020. KBTH is the largest teaching hospital in the country and serves as a tertiary referral center for the Greater Accra Region and its environs. Annually, the KBTH conducts approximately 10,000 deliveries and nearly one in five pregnant women experience preterm birth [ 10 ]. The preterm birth rate of approximately 20% has been reported with about 50% NICU admission rate [ 10 ]. The hospital has a moderately well-equipped neonatal intensive care unit situated in the Maternity unit, managing preterm infants and neonates requiring intensive care services.

Study population

Women of 18 years and above who delivered preterm (less than 37 completed weeks of pregnancy) at the health facility, and provided informed consent were eligible for participation. We included preterm births with livebirths from spontaneous onset of labor (including preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes) or provider-initiated (medically indicated) phenotype including caesarean deliveries for maternal or fetal indications. Women were excluded if they had multiple pregnancies due to their increased risk for preterm birth and pregnancies that ended in stillbirth. We excluded the women with stillbirths because we were primarily interested in understanding the experiences of caring for preterm neonates especially at the neonatal intensive unit.

Recruitment, sampling and data collection

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants into the study with the aim of achieving varied obstetric history, maternal age and socio-economic characteristics. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling involving initial identification and selection of study participants of interest who are proficient and optimally informed concerning the phenomenon being studied [ 17 , 18 ]. In this study, the Research Assistant (RA) identified women who met the inclusion criteria. These women were then approached and the study protocol was explained to them individually by a trained research assistant (ET). The RA had Master’s degree in Statistics and was a non-health worker with considerable experience in conducting IDIs. Mothers who consented were then scheduled for an interview immediately after their discharge from the hospital. The IDIs were conducted in a quiet designated room at the hospital. All the respondents provided written informed consent before the interviews. Recruitment of participants continued until no new themes emerged from the data (data saturation was reached). The IDIs were carried out in English, Twi or Ga (two local Ghanaian dialects) and audio recorded. The interviews lasted between 17 to 50 minutes. We used a semi-structured interview guide ( S1 File ) with varied questions and appropriate probing was done during the interviews.

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the College of Health Sciences University of Ghana (Protocol ID: CHS-EtM.4-P1.2/2017-2017). Written informed consent was granted by all participants prior to collection of data. We ensured anonymity by non-inclusion of any identifiable information on the women included in the study.

Data management and analysis

Transcription of the interviews started soon after the commencement of data collection. Back-to-back translation of all IDIs from Twi or Ga (Ghanaian dialects) into English were done and ET checked all transcripts for accuracy and completeness. A code book was developed from the review of the transcripts and themes that emerged from the data were identified. The coding was done by ET and the principal investigator (KAB), who is an obstetrician/gynecologist at KBTH. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion between KAB and ET. NVivo version 12 software was used for the coding and analysis. In this study, the data analysis was undertaken based on the thematic content by employing the inductive analytic framework where the themes were based on recursive reading of the transcripts with minimal theoretical background influence [ 19 ]. Triangulation of the study findings was achieved via the inclusion of different case-mix comprising women with both spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm births. The authors of this study had different but relevant specialties including obstetricians, epidemiologists, social scientist, and pediatricians. The convergence of different researchers with related research interest created the needed reflexivity and interpretation of the study findings. In writing this paper, the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were employed as a guide [ 20 ].

A total of 50 women were invited for the in-depth interviews, out of which 30 provided informed consent and participated. The reasons given by those who declined participation in the interview included: the need to follow up on laboratory results of their babies and did not have time; some mothers had to return home to attend to their other young children; or they were emotionally stressed from their baby’s admission at NICU and were therefore not interested in the study.

Most of the women had Junior High School level of education (n = 13, 43.3%) and were married or cohabiting (n = 19, 63.3%). Half of the women were petty traders (non-professionals) and between the ages of 20–30 years (n = 15, 50%). Majority of the women had 1–4 previous deliveries (n = 29, 96.7%) and most had no history of previous preterm birth (n = 28, 93.3%) ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001303.t001

The major themes that emerged from the narratives of women who had recently experienced preterm birth were:

- Women’s knowledge on preterm birth

- Financial burden of preterm birth to families

- Mothers’ experiences of neonatal intensive care unit admission

- Recommendations to improve the quality of care

1. Women’s knowledge on preterm birth . Women’s knowledge on preterm birth was a major theme that emerged and mixed findings were reported concerning the causes and complications. An important sub-theme that emerged from the interviews related to the causes of preterm delivery and the study participants described various conditions associated with preterm birth. Hypertension in pregnancy, which is locally referred to as “BP”, was mentioned as the main cause of preterm delivery. Stress-related issues and physical activities such as frequent bending down were also cited by some respondents as causes of preterm birth.

“ They said a woman could deliver before her time and that could be as a result of BP , or if the baby is not well positioned that could also make the baby come before the time .” ( Married , 38 years )

“ High BP can cause it . High pressure can make you deliver preterm .” ( Married , 28 years )

“ If you bend down too much , over stressed , things like that can cause it or thinking or you have some marriage problems , plenty things like that .” ( Married , 30 years )

Most of the participants had adequate knowledge about the neonatal complications associated with preterm birth, and mothers mentioned complications associated with preterm birth such as infant death, poor physical health and infection.

“ You may lose the baby . Some of the babies survive but they don’t have the full strength to work or do something , may be physical activities .” ( Single , 25 years )

“ When you deliver the baby too early and in case the hospital where you delivered does not have an incubator , the baby can get an infection and can die instantly .” ( Married , 28 years )

Some participants indicated the possibility of poor development or formation of some organs in the infants (congenital anomalies) such as the eyes or ears. This is evidence suggesting that some of the mothers were well-informed about preterm birth and its complications.

“ May be a part of the body may not be well formed . May be the eye or ear .” ( Trader , 31 years )

On the other hand, some women had limited knowledge on preterm birth and its causes. There were significant misconceptions especially nutritional associations with preterm birth. Health education and more research into the causes of preterm birth were recommended to improve women’s understanding on the condition.

“ If we had been educated may be , I wouldn’t have eaten what I wasn’t supposed to . Be it the diet or thinking , I don’t know what caused it but if they can carry out research into it to find out the cause and are able to educate us , I’m sure these things ( preterm deliveries ) wouldn’t go on .” ( Cohabiting , 27 years )

2. Financial burden of preterm birth to families . Another important theme that emerged was the effect of hospital admission on participants and their families. Financial constraints greatly affected the preterm mothers, and their partners had to make extra efforts to raise the additional funds needed to pay hospital bills. The plans of families were also disrupted and in some instances some husbands could not go to work as they had to visit their wives in the hospital frequently. Following discharge, some women could not afford the cost of treatment and were not able leave the hospital until the bill was paid. Such mothers were frequently detained further in the hospital until all hospital bills were settled.

“ I have been discharged and the bill is 350 Ghana cedi [60 USD]and my husband hasn’t got the money . He has gone round and hasn’t been able to raise the money .” ( Married , 33 years )

“ I have been discharged now and my husband went to find out how much my bill is . They have given him the amount so he has gone out to look for the money so that he can get me discharged .” ( Married , 28 years )

Since my admission , my husband has not gone to work for three days . He can’t go to work because it is just the two of us . He is always here seeing to the purchase of my medication . It prevents you from making money and it takes up all your time . It has messed everything up .” ( Married , 28 years )

The national health insurance scheme (NHIS) provided minimal coverage for the facility bills leaving the preterm mothers and their families with the burden of paying most of the bills out-of-pocket. Some of the participants asserted that the insurance scheme covers only the less costly items in their medical bill and the more expensive ones are paid by the mothers themselves.

“ Since I came here , we bought all my drugs except the one that you insert [rectally] . My husband said he bought all the other drugs .” ( Married , 28 years )

“ Just the things that are not expensive—that is what the NHIS will cover .” ( Married , 31 years )

Although there is some NHIS coverage for neonatal care, most of the women had to pay for a significant portion of the medical bills related to oxygen therapy, laboratory test and medications for the preterm infants. The women’s narratives indicated the entrenchment of cost-sharing between the NHIS and parents. In some situations, the mothers verified the treatment provided to their babies before making payment for their hospital bill.

“ I’m paying 405 Ghana cedis [68 USD] after receiving support from insurance .” ( Married , 31 years )

“ All I saw was ward fee and oxygen . When I visited the baby on the second day I didn’t see any oxygen being given to him so I asked her why I was charged for oxygen and she said the baby was given . She brought the confirmation which had been recorded that the baby was on oxygen for 24 hours .” ( Married , 38 years )

“ I paid it myself . I bought the drugs and paid for the labs . Insurance covered some and I also paid for some .” ( Married , 22 years )

3. Mothers’ experiences of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission . Most of the prematurely born babies were admitted to NICU. Generally, mothers of preterm infants are informed about the need for admission of their preterm infants to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Although the narratives indicate that the mothers are informed about the need for NICU admission, no comprehensive counseling and education on expectations are provided.

“ So all I heard was the baby’s crying and they came to show her to me saying ‘you had a girl’ and I said ‘okay’ . Then they said she was small so they are sending her to NICU .” ( Cohabiting , 24 years )

“ They showed the baby to me after he was taken out : [ .. ] ‘this is your baby , but because his time wasn’t yet up , they will send him to NICU so that he can regain his strength’ .” ( Married , 30 years )

The NICU admissions had major psychological and emotional effect on the mothers, mainly due to the uncertainty of their preterm babies’ survival. Majority were not happy about the fact that they were separated from their babies and not knowing what is happening to their babies. Women who had previous experiences of delivering preterm and losing their babies at NICU were terrified of potentially experiencing infant demise for the second time.

“ I feel very sad , [ .. ] there is no mother who would feel happy when she is somewhere else and her baby [is] at another end .” ( Married , 28 years )

“ I was scared when they took the baby there [NICU] because my first pregnancy . That pregnancy was [ended at] about 26 weeks . They took the baby there and the next day the baby passed on . So this one I was so scared . I was praying to God that , ‘please this one spare me’ .” ( Single , 27 years )

“ You’ve delivered so your baby should be laying by you . So I don’t like going there [NICU] because leaving him behind is painful .” ( Married , 35 years )

The burden of having to visit their babies several times at NICU was very challenging for most mothers especially those who have had a caesarean section. Mothers who lived far from the hospital had to spend the entire day at the hospital as it was challenging for them to travel back and forth. In addition, some mothers spent long hours at the laboratory to wait for reports of their babies’ laboratory tests. This disrupted their expectations of motherhood in the postpartum period and had an enormous impact on their finances and emotions.

“ I have had CS and having to walk up and down is very worrying for me . When the baby is on admission the labs and all that are a lot , which make the cost very high . You are given a new lab test for the baby every day .” ( Married , 38 years )

“ I’m disturbed ( Respondent breaks down in tears ). I wish I had delivered my baby at 9 months . I live far from here [the hospital] and I come here and see the baby three times a day : If you come in the morning you have to wait till evening because you have to go and see him in the afternoon and evening . Everything has been messed up so I’m very worried .” ( Married , 28 years )

“ It took a long time because they [lab technicians] said I couldn’t get the lab results [of the baby] . So I pleaded with them and told them I had been operated on so I couldn’t go and come back so I had to sit down . So I really kept long . I got there at 4 [pm] but when I was leaving it was around 7 [pm] .” ( Married , 37 years )

4. Women’s recommendations to improve the quality of care . The preterm birth mothers explained how overwhelming the medical bills for them and their babies were. This resulted in some of them absconding from the hospital without paying their bills. They indicated that the NHIS does not cover the cost of most of the medications and laboratory tests needed by the preterm neonates. They therefore urgently recommended wider NHIS coverage of services to ease the financial burden associated with preterm delivery and neonatal care for premature infants.

“ The insurance should be able to cover majority of the cost . When you are discharged you pay a lot and the insurance only covers a small portion . So , the government should ensure that it [NHIS] covers majority of the labs for us ” ( Married , 38 years )

“ Three days and the drugs are almost 700 Ghana cedis [115 USD] plus . And what about the baby in the incubator ? Staying here for long [myself] and the baby too being on admission , when they discharge her and the money is a lot , that brings about a huge burden . So we will plead with the government for any form of support so that when it [preterm birth] happens (..) they can take care of the bills for us .” ( Married , 28 years )

Some mothers emphasized that they do not usually have an idea about the amount of money they will pay for their infants’ admission. This makes them inadequately prepared to pay their bills and result in psychological stress for them and their families. One mother speculated that her preterm infant might be on admission at neonatal intensive care for over a month and guessed she might pay a lot of money following discharge. She estimated the medical bill to be GHC 1500 (250 USD; 1USD was approximately 6GHC). The rate She pleaded with the government to come to their aid.

“ I don’t know the baby’s bill and I’m also here . They could come and ask me to pay the bill when the baby is 1 month 2 weeks or something . I might be asked to pay GHC1000 or GHC1500 [160–250 USD] , when that happens you are disturbed so I will plead with the government to help in this aspect .” ( Married , 28 years )

Health education on preterm delivery with emphasis on treatment was also recommended by majority of the respondents. Also, timely interventions such as giving medications that will help mothers and babies was requested.

“ If it depends on the medicines that we have being taking , they should educate us well . Maybe if you take too much of this drug , it can cause this or maybe when you are too stressed it can cause this . If they give us these forms of education , we will be aware and careful so that all these will end and not happen again .” ( Married , 30 years )

In this qualitative study we explored the knowledge and lived experiences of women who experienced preterm birth and the associated challenges in caring for premature infants. There were mixed findings concerning women’s knowledge on preterm birth with some mothers displaying significant understanding including the causes and potential complications. We found that women who recently experienced preterm birth faced significant social and financial challenges which negatively impacted on their experience of care. Admission of preterm infants to the neonatal intensive care unit also generated enormous psychological and emotional stress on the affected mothers due to uncertainty relating to the prognosis of their babies and the unexpected health system challenges including increased cost of care. Important recommendations to improve the experience of care for prematurely born infants were proffered by the affected mothers including the urgent need for expansion of the NHIS coverage and more client education.

Women demonstrated substantial knowledge about the causes of preterm birth and associated complications such as neonatal death. However, the mothers were not adequately prepared for the challenges of neonatal admission which resulted in substantial emotional stress and negative experiences during the postnatal period, consistent with observations by Brandon et al [ 21 ] in the United States. An important challenge faced by the mothers was the stress of multiple visits to see their babies in the NICU, especially for women who delivered by cesarean section. Modification of NICU facilities to align with WHO standards for improving quality of care [ 22 ] and provision of spaces or family rooms for mothers with preterm infants may improve bonding, direct hand-on care and reduce the stressful postnatal experiences by the mothers [ 23 ]. This will provide parents the opportunity, motivation and empowerment to offer parental support to their babies including Kangaroo mother care, as well as other care practices. There is an urgent need for improved ANC education to create more awareness about preterm birth and available neonatal care services for premature infants to adequately prepare prospective mothers for the unanticipated postnatal challenges. Similarly, improvement in the physical and logistic set up of the hospital could also address the long waiting hours at the laboratory centers for babies’ laboratory tests, which lead to extreme distress especially for the cesarean mothers. For example, with automatic direct or electronic sharing of laboratory results to the care providers can lessen the burden on the already stressed mothers who are recovering from childbirth. The electronic medical records system is currently being implemented in the hospital, and when fully established, can help send laboratory results directly to doctors to relieve mothers of this burden.

NICU admission had significant psychological and emotional effect on the mothers. This was due to uncertainty about the survival prognosis for the preterm infants perceived by the mothers, separation of the babies from their mothers resulting in poor bonding, financial worries, and other causes. There is evidence that mothers of preterm infants are at greater risk of postpartum depression (PPD) than mothers of term infants [ 24 ]. In the Netherlands, Blom et al reported that mothers who experienced more than two perinatal complications such as emergency cesarean delivery, hospitalization of the baby at birth, pre-eclampsia, and hospitalization during pregnancy had increased risk of developing PPD [ 25 ]. Similar maternal emotional concerns have been reported in other studies [ 21 , 26 ]. In Malawi, Gondwe et al reported that mothers of preterm infants experienced severe distress symptoms and cesarean section was associated with worse postpartum experiences [ 26 ]. In this study, women who had a previous experience of neonatal death following preterm birth were terrified of losing their babies again. These findings highlight the urgent need for integration of psychological support for all women who experience preterm birth to improve their postnatal experiences of care, and particularly for women and families who experience bereavement.

Similarly, majority of women expressed how their babies were immediately separated from them after birth resulting in impaired mother-baby bonding. Recent evidence determined that early parental interaction reduces the risk of late PPD but has no influence on early maternal adjustment or late mother-infant relationship [ 27 ]. In a related study, immediate separation of mothers and their babies after birth created challenges in women conceiving themselves and functioning optimally as mothers [ 28 , 29 ]. This phenomenon of “powerless responsibility” describes the situation when mothers are knowledgeable and yet powerless to influence their infants’ feeding which negatively impacts on their instinctive mother-care [ 28 ]. However, this challenge may be ameliorated via effective client-centered communication and care, including counselling of the affected mothers. WHO recommends mother-to-baby bonding should commence immediately after childbirth [ 22 ]. However, in preterm birth, most of the newborns are immediately transferred to the neonatal care unit frequently leaving the mother isolated, powerless and emotionally challenged as their birth expectations of motherhood are curtailed with substantial insecurity about the health status of their babies. Appropriate maternal education, optimal counseling, effective provider-client communication and supportive physical environment are important adjunctive measures for allaying the emotional and psychological influences of quality of care. Allowing women to be close to their infants, even during NICU admission is recommended to enhance mother-infant bonding and parental involvement in the care for the baby.

Although maternity care services under the NHIS are supposed to be free in Ghana [ 30 , 31 ] the coverage was reported by women to be only minimal. They narrated instances where they had to pay for medications and laboratory tests that were not covered by the NHIS resulting in significant financial constraints on the family. The financial consequences and out-of-pocket expenditures have also been reported by other studies [ 31 , 32 ]. A recent study in Ghana explored parental cost for hospitalized neonatal services and reported that irrespective of health insurance status, medical-associated costs accounted for approximately 66% of out-of-pocket payments and the mean out-of-pocket expenditure was about $148 for preterm or low birth weight [ 33 ]. In Ghana, the mean household size is approximately 6.5 and the average household annual income is approximately GH₵ 33,937 (6,650 USD) with monthly household income of GH₵ 2,830 (470 USD) [ 34 ]. Approximately 10% of parental annual income can be expended on acute care for premature or low birth weight infants [ 33 ]. In these circumstances, financial constraints can potentially delay the care process and result in suboptimal care. Most of the women therefore recommended for measures to increase the coverage of the NHIS by the government to ease the financial burden of the affected mothers, as others have also called for in other studies [ 35 ]. Similar national health insurance challenges have been reported in other LMICs including inadequate implementation and coverage [ 36 ].

In the Ghanaian context, family members play a major role in caring for their relatives on hospital admission including contribution to the payment of hospital bills, chasing of laboratory reports from laboratory centers, running to purchase medications and provision of psychological/social support. There is evidence that provision of social support by family relations improve the physical and psychological health of the mothers and enhance attainment of optimal maternal role in the postpartum period [ 37 ]. On the other hand, financial constraint in settling hospital bills is a major challenge for most mother and their families. Although the NHIS is expected to cover maternal health services (free delivery policy through the NHIS) [ 38 ], there is evidence that women and their relatives pay considerable proportion of their medical bill via out-of-pocket [ 30 , 39 ]. In addition to the burden of financial constraints or poverty, there are real-time health system challenges that preclude provision of comprehensive care for mother and their babies without the support from family members. To reduce unnecessary health system delays in provision of care and reduce the high perinatal morbidity in the country, an urgent paradigm shift in re-structuring the health system is needed to minimize significant dependance of family members especially for hospitalized mothers and preterm infants. An effective collaboration between the health system and NHIS is required to independently provide comprehensive clinical care to mothers without over-reliance on financial or physical support from families. To this direction, effective health system and NHIS financing or management with realistic costings for medical services is urgently recommended as a context specific intervention to improve maternal and newborn care in the country.

Strength and limitations

The main strength of this study relates to the qualitative design which provided the opportunity for the mothers of prematurely born infants to openly share their lived experiences of care emphasizing on the challenges and key recommendations for improvement. The conduct of the interviews after the mothers had been discharged also enabled the mothers to freely discuss the challenges they encountered without fear of not receiving optimal care.

The limitations of the study include the single tertiary hospital where the study was conducted compared to a multicenter study which would have provided a more comprehensive and varied descriptions of women’s experiences of preterm birth in Ghana. Also, the use of only one interviewer could have introduced some form of bias: the interviewer was however experienced in qualitative data collection thus reducing the potential for significant bias. Another important limitation was the use of in-depth interviews only for the data collection without inclusion of focused group discussions (FGDs). The non-inclusion of FGDs may have influenced the triangulation and the applicability of the findings. FGDs would have generated diverse women’s experiences of preterm birth in a more interactive manner. In addition, key informant interviews of health workers and key policy makers were not included. The perspectives of health workers and policy makers would have provided a more comprehensive understanding of the provision and experience of care related to preterm birth. Notwithstanding, the findings of this study provides significant insight into the clinical and postnatal experiences of women who deliver preterm in a typical tertiary hospital in Ghana.