tags --> Discourse Analysis in Critical Social Work: From Apology to Question

Tags. remove any or tags --> by amy rossiter, msw, ed.d., associate professor, school of social work, york university, toronto, ontario, canada.

This paper concerns the relation between critical reflective practice and social workers’ lived experience of the complicated and contradictory world of practice. I will outline how critical reflection based on discourse analysis may generate useful perspectives for practitioners who struggle to make sense of the gap between critical aspirations and practice realities, and who often mediate that gap as a sense of personal failure. I will describe two examples of discourse-based case studies, and show how the conceptual space that is opened by such reflection can help social workers gain a necessary distance from the complexity of their ambivalently constructed place. Discourse analysis can provide new vantage points from which to reconstruct practice theory in ways that are more consciously oriented to our social justice commitments. I understand these vantage points in the case studies I will describe as: 1) an historical consciousness, 2) access to understanding what is left out of discourses in use, 3) understanding of how actors are positioned in discourse, all leading to: 4) a new set of questions which expose the gap between the construction of practice possibilities and social justice values, thus allowing for a new understanding of the limitations, constraints and possibilities within the context of the practice problem.

Introduction

This paper concerns the relation between critical reflective practice and social workers’ lived experience of the complicated and contradictory world of practice. I will outline how critical reflection based on discourse analysis may generate useful perspectives for practitioners who struggle to make sense of the gap between critical aspirations and practice realities. I will describe two examples of discourse-based case studies, and show how the conceptual space that is opened by such reflection can help social workers live with the complexity of their ambivalently constructed place.

For some time now, I have been interested in the role of critical reflection in social work practice (Rossiter, 1996, 2001). It has proved difficult to reconcile conventional theories of practice with a vision of social work as social justice work. Thus, I have found myself on the terrain of a kind of critical ethics that views practice theories as stories about the cultural ideals of practice, and that treats practitioners’ experiences as stories that can teach us about the conduct of practice in relation to such ideals. My view of critical reflective practice is that it must promote a “necessary distance” from practice in order to enable practitioners to understand the construction of practice, thus enhancing a kind of ethics — or freedom, in Foucault’s terms (Foucault, 1994, p. 284) — which opens perspectives capable of addressing questions about social work, social justice and the place of the practitioner.

I am interested in a critical ethics of practice because social workers as people suffer when the results of practice seem so meager in comparison to the ideals inherent in social work education, in agency expectations, and in implicit norms which define “professional.” In conventional social work education, practitioners are asked to believe that they will learn a theory, and then learn how to implement it. These theories contain values that are supposed to dovetail with practice. There may be ethical dilemmas that need to be resolved via ethics codes and decision-making schema, but practitioners will follow the prescriptions of liberalism by making correct decisions, craftily implementing theory through the right interventions, and now, even overturning racism, classism and sexism in the process. The failures of this fantasy cause us to suffer, to apologize, to despair.

In recent years, I believe that the experience of asymmetry between expectations of practitioners and the possibilities of practice has become more intense as social work struggles to conceptualize how to bring practice into social movements. In this hope for practice as justice, the responsibility of social work is shifted from change at the more discreet levels of individuals, families, groups, communities, to the social determinants that produce private troubles. Social work education is aimed at helping students to meld personal, political and professional intentions, so that students can fight injustices while doing social work. Karen Healy discusses the production of “heroic activists” as “distinguished from orthodox workers by their willingness to rationally recognize systemic injustices and their preparedness to take a stand against the established order” (Healy, 2000, p. 135). Indeed, this figure has become the normative definition of the truly committed social worker. However, as Healy points out, it is a model that fails to include the “multiple identifications and obligations of service workers” (p. 136). Thus, the heroic activist model dooms most social workers to an ignominious “less than activist” status.

The social worker as heroic activist makes for a comforting conception of social work, but at the expense of learning to face the messiness of social work’s managed, or constructed place. We don’t know how to know social work as a constructed place, and ourselves as constructed subjectivities within that political space (Rossiter, 2000). Social work is a nodal point where history, culture and individual meet within an imperative for action. Given the mandate of working with marginalized people, this particular nexus is a place of crushing ambivalence. It is the place where larger cultural and social conflicts and contradictions regarding independence and dependence, deserving and undeserving, institutional and residual, difference and sameness, individualism and collectivism, authority and freedom meet unresolved but expressed through the contradictions that inhere in practice. No wonder we cling to the fantasy of the smooth trajectory of practice.

Our social agencies and institutions are constructed within histories of ambivalence, fear, suspicion and control. We remove children from disadvantaged families by targeting mothering skills. We administer welfare policies that cement poverty. We’re asked to help but not make people dependent. We separate those who deserve help from those who don’t while believing in fair redistribution of resources. We decry racism and declare our allegiance to anti-oppressive practice while working in primarily white agencies. We acknowledge a knowledge-based economy while making tuition unaffordable. And into this breach enter social workers with our desire to make a difference, and our theories on how to do that. When we fail, we describe the result as burnout. Neatly avoiding how workers are constructed, we ascribe burnout to hearing painful stories of others, to stress, “doing more with less,” dysfunctional organizations and other explanations that implicate individuals.

Most social workers take up the profession because of personal ideals. We want to use our work as a contribution, as something of value to the world. Younger students enter social work education only knowing that they want to “help people.” Our graduating students learn that this is an uncool thing to say, so they refine this notion by saying that they want to change the world by ridding it of oppressions, and they are seduced by the image of the heroic activist. When they enter the world of practice, they are thrown into sites constructed by contradictions and ambivalences where their subjectivities as practitioners embody these contradictions, yet they still expect to enact their ideals. Yet, as Linda Weinberg (Weinberg, 2004), in her work on the construction of practice judgments, notes that “...to locate ethics within the actions of individual practitioners, as if they were free to make decisions irrespective of the broader environment in which they work, is to neglect the significant ways that structures shape those constructions and to erect an impossible standard for those embodies practitioners mired in institutional regimes, working with finite resources and conflicting requirements and expectations” (Weinberg, 2004, p.204).

Our constructed location is often a painful one. We know all too well the struggles of the child protection workers, welfare workers, and hospital workers who find it difficult to face the fate of their ideals within the construction of their practice. Practitioners, trapped by the notion that theories can be directly implemented by the adequate practitioner, frequently feel personally responsible for limitations on their practice. Perhaps an alternative way to understand burnout is to see it as deep disappointment that results when we are unable to enact the values we hold and have been encouraged to hold, and when that disappointment is interpolated as our fault or the agency’s fault, at the expense of understanding the social construction of the failure. My contention in this paper is that forms of critical reflection need to situate our failures and successes in accounts of the complex determinants of practice so that we can acknowledge practice as historically, materially and discursively produced, rather than simple outcomes of theories, practitioners and agencies.

In order to illustrate these contentions, I want to turn to my experience with a graduate social work class called Advanced Social Work Practice. Teaching this class was a daunting prospect. A conventional course on advanced practice should explicate practice theories, perhaps compare and critically analyze them and then devise methods for their application in practice. In considering this approach to the course, I had begun to feel like Alice in Wonderland, believing as I did, that such conventions produce ever greater disjunctions between practitioners’ experiences and orthodox social work education. I was also worried that students coming to class hoping to refine their grasp of narrative therapy, brief therapy, solution-focused therapy or cognitive behavioural therapy, all within the context of an anti-oppressive stance, would be very disappointed by the substitution of esoteric critical ethics for advanced practice.

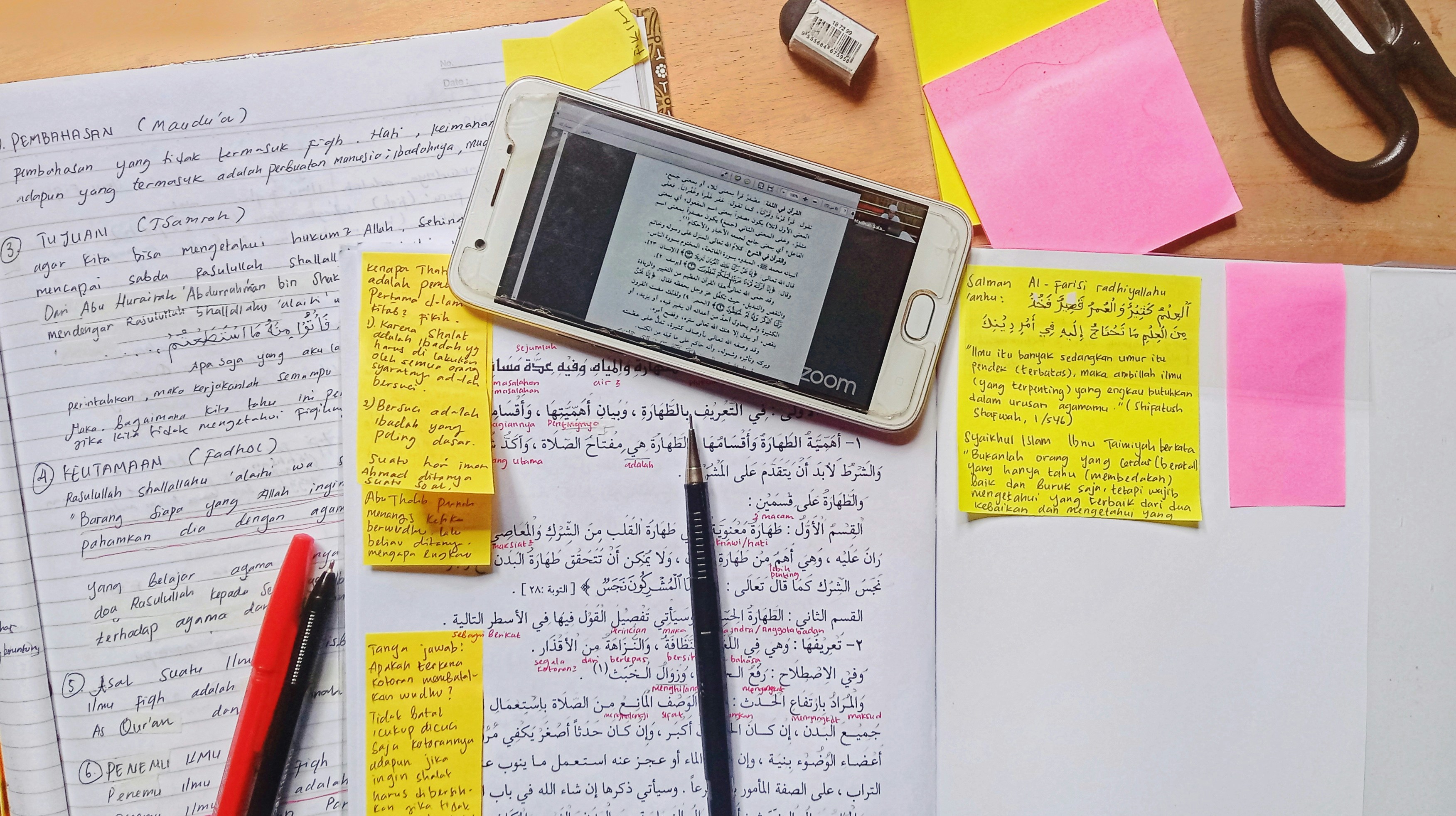

With trepidation, I began the class by asking students to submit a case study from their practice experience that they would like to study collectively using a form of discourse analysis. These students either had significant work experience, or experience in a previous practicum to draw from. When I read the case studies, I was taken aback to find that students chose to write about stories of pain and distress in their practice contexts. The case studies were stories of clients whom they remembered with a sense of failure or apology or shame. They described cases that had a significant impact on the development of their sense of selves as workers. They generally represented moments of feeling as though they did not live up to the ideals and values they learned in schools of social work, and they felt a keen sense of disappointment and anger at their helplessness in complicated social, cultural and organizational conjunctures. My students came to class as failed heroes.

I was at once horrified by the level of individual self-recrimination in the cases, and inspired by the deep levels of commitment, thought and reflection evidenced by these students. It was clear to me that the emotions described in these cases could only be exacerbated by introducing newer and improved practice theories, as if the proper application of such theories could have achieved different outcomes, thus alleviating individual failure. Indeed, more “how tos” could only add to their apology stance. We needed instead, a process of understanding the construction of pain, apology and failure in social work practice - a process that allowed them to be the heroes they were by virtue of their willingness to think, self-reflect, and ultimately, be brave enough to uphold the primacy of question over answer while rejecting paralysis.

Critical Reflection Through Discourse Analysis

While reflective practice held promise for liberating professions from misconceptions about the interrelationship between theory and practice, following Schon’s (1987) introduction of reflective practice, theorists began to identify the problem of incorporating critical analysis into reflective practice ((Brookfield, 1996; Fook, 1999; Mezirow, 1998). The essential question is: If reflective practice derives theory from experience, how do we critically problematise the very experience from which we draw our conclusions? Joan Scott (Scott, 1992), in her effort to call the innocence of experience into question says:

When experience is taken as the origin of knowledge, the vision of the individual subject (the person who had the experience or the historian who recounts it) becomes the bedrock of evidence upon which explanation is built. Questions about the constructed nature of the experience, about how subjects are constituted as different in the first place, about how one’s vision is structured — about language (or discourse) and history — are left aside (Scott, 1992, p. 25).

In other words, if experience is the unproblematized foundation of theory, how do we challenge the values and ideologies that are carried in and through experience? After all, says Stephen Brookfield, “Experience can teach us habits of bigotry, stereotyping and disregard for significant but inconvenient information. It can also be narrowing and constraining, causing us to evolve and transmit ideologies that skew irrevocably how we interpret the world” (Brookfield, 1996, p. 36).

Carolyn Taylor and Susan White make a distinction between reflection and reflexivity where the latter adds a critical dimension by calling taken-for-granted assumptions into questions (Taylor & White, 2000). Further, they suggest that reflexivity is not simply an augmentation of practice by individual professionals, but a profession-wide responsibility. “...knowledge is not simply a resource to deploy in practice. It is a topic worthy of scrutiny” (p. 199). In our case, the class project was to scrutinize the knowledge claims embedded in cases — and to understand the implication of such claims for their affective relationship to practice as well as on the experience of their clients.

But how do we scrutinize knowledge claims? In order to achieve a critical social work practice — a practice capable of grasping towards an ethics of practice - we needed to raise questions about the construction of experience in the class’s case studies. Elements of postmodern theory provided a way into the achievement of this “necessary distance.” A postmodern perspective, in Jan Fook’s view (Fook, 1999), “pays attention to the ways in which social relations and structures are constructed, particularly to the ways in which language, narrative, and discourses shape power relations and our understanding of them. In particular, dominant structures are subject to question because of the ways in which meanings are constructed on oppositional lines” (p. 203)

Understanding our constructed place in social work depends on identifying how language creates templates of shared understandings. Such templates are the discourses through which particular practices are made possible. Jane Flax (Flax, 1992) defines discourses as follows:

A discourse is a system of possibilities for knowledge. Discursive formations are made up in part of sets of usually tacit rules that enable us to identify some statements as true or false, to construct a map, model or classificatory system in which these statements can be organized, and to name certain “individuals” as authors. The rules provide the necessary precondition for the formation of statements. The place, function, and character of the knowers, authors, and audiences of a discourse are also functions of discursive rules. All discursive formations simultaneously enable us to do certain things and confine us within a necessarily delimited system (Flax, 1992, p. 205).

Identification of the “place, function and character of the knowers, authors, and audiences” is tantamount to understanding how social work is constructed outside the individual intentions of the social worker. This is how discourse analysis can displace the individualism of the “heroic activist” in favour of a more nuanced, complex and sophisticated analysis. “Discourse analysis can enrich progressive social work practices by demonstrating how the language practices through which organizations, theorists, practitioners and service users express their understanding of social work also shape the kinds of practices that occur...” (Healy, 2000).

In our class, discourse analysis helped illuminate the production of feelings of individual shame and apology as responses to practice. I argue that understanding this process of production is a way of doing ethics which reduces, or at least acknowledges the unintended, often subliminal consequences of practice that flow from social ambivalence which constructs social workers and service recipients in the conduct of practice.

In order to provide a frame for critical reflection on their cases, I chose four elements of associated with discourse analysis: 1) Identification of “ruling” discourses in the case studies; 2) the oppositions and contradictions between discourses; 3) positions for “actors” created by discourses which in turn shape perspectives and actions; 4) and the constructed nature of experience itself. These elements helped students writing cases from memories saturated with unease about their own performance to shift from “what I did” to how the case was constructed, and how their feelings arose from the complicated constructions of their practice within particular locations and time.

Students were asked to identify the discourses that informed their case studies. The purpose was to analyze how such discourses produced their conceptions of the cases — and how they confined their thinking about the case. The overall question I asked students to raise in relation to their cases was “what is left out?” Interchanging the terms discourse and story, we talked about how stories both include and exclude, forming boundaries in meaning (Spivak, 1990), and that critical practice is the search for what is left outside the story. Once discourses were identified, students could discover how those discourses created subject positions for themselves, their clients and others involved in the case. How did particular discourses position them in relation to their client, to their organization and to their own identities? How did some discursive positions conflict with their own self-knowledge? Such a process enabled them to stand back from the scope of their practice in order to understand its construction within a particular discursive space.

We worked to identify oppositions between competing discourses. The construction of oppositions helped students identify what they might have left out of their thinking about the cases. When oppositions are in place, what boundaries are erected? How do some discourses oppose or resist power? Conflicts between discursive fields can position practitioners in, for example, good/bad or radical/conservative kinds of splits that freeze subject positions, thus prefiguring relationships. While not eschewing the need to take positions — in other words, without advocating relativism — students could look at ways of thinking, at alternative perspectives that were outside the terms of the oppositions. We frequently found that dependencies within competing discourses were obscured by oppositions. Once these dependencies were uncovered, alternatives to opposition emerged.

Throughout our analyses, we worked to understand what views discourses permitted or inhibited. In other word’s we challenged the “god trick” of an all-encompassing, unlocated perspective, in Donna Haraway’s terms (Haraway, 1988, p. 581). When multiple discourses are uncovered, then we can treat our own perspective as limited, particular, local and contingent as opposed to the adoption of expert professional view as the privileged view. Understanding our perspectives as contingent enables us to understand our own complicated construction within a field of multiple stories giving rise to multiple perspectives. The sense of the “multiple stories” at play helped relocate the notion of experience as brute reality carrying authority by virtue of being “real” to a notion of experience as constructed, contingent, and always interpreted. This vantage point enabled students to move from the need to find answers and techniques to the radical acceptance of practice as the unending responsibility for ethical relationships which are always/already jeopardized by larger social relations.

Two Case Studies

I would like to turn to two case studies which illustrate how discourse analysis was used by students.

Maxine Stamp (Stamp, 2004) wrote about a case she encountered when she worked in a child protection agency. The case involved a single mother originally from the Caribbean. Maxine was routinely assigned cases involving immigrant people of colour because she herself is an immigrant woman of colour. Her agency had neither an analysis of the sensitivity of her position in relation to immigrant clients, nor the racist assumptions that grounded these case allocations.

The case involved Ms. M, a single mother of two teenage daughters. Ms. M had immigrated to Canada when she was an adolescent. Her mother had immigrated years before, leaving her in the care of her paternal grandparents and a stepfather. Following her immigration, she lived only for a short time with her mother, from whom she had been separated for most of her childhood. She moved out on her own, successfully pursued advanced education and was on the verge of achieving professional accreditation at the time of Maxine’s contact with her. She had two teen-aged daughters who had been left in the country of origin as very young children while Ms. M established herself in Canada. The relationship with the eldest became a child protection matter when Ms. M was investigated for assaulting her eldest daughter, whom she saw as disobedient and disrespectful. Despite Maxine’s best efforts, this troubled relationship ended in separation when the daughter moved in permanently with a relative. Maxine was devastated at her inability to put the relationship between mother and daughter to rights. She remembered the case with a sense of failure, and her recounting of the case was marked by a kind of unexplained sorrow.

Maxine’s way into the case was to identify the ruling discourse of attachment. Attachment theories are common explanations of the parent/child conflict in some immigrant families’ experiences of separation and reunification during patterns of immigration. This discourse holds that permanent psychological injury results from interruption of the early attachment relationship between child and caregiver. Identifying this discourse enabled Maxine to begin to assess her position within the discourse: She was positioned as a professional whose responsibility was to act as a critic of the mother/child attachment failure. From this position, responsibility for the problems were located in the mother, who, in attachment terms, did not properly manage the separation and reunification issues. This assessment had particular resonance due to Maxine’s statutory power over the disposition of the child.

This discursive position effectively disallowed a subject position of another sort: solidarity with her client. As a woman of colour from the Caribbean, Maxine shared experiences with other immigrant women of colour in Canada; shared a cultural heritage, and an insiders’ knowledge of the difficulties of negotiating these spaces. But from her constructed perspective as a child protection worker, where attachment discourses dominated the field of explanations, there was little possibility to act in solidarity with Ms. M. Indeed, she was profoundly aware of Ms. M’s anger at Maxine’s position within “Canadian” authority, where such authority could not acknowledge the realities that she and Maxine shared.

When we asked the critical question about what is left out of the story of attachment, it became clear that such a story is applied to individuals without regard to history and context. As such, individuals bear the weight of individual responsibility for such histories and contexts, thus obscuring a greater range of accountability. We began to think about the history of forced separation and forced disruption of families beginning with the importation of African slaves to the Caribbean. We began to think about the ways slavery is replicated in different incarnations following the end of slavery. Maxine pointed out, for example, that Caribbean women were previously allowed to immigrate to Canada to take up positions as domestic servants but were expressly forbidden to bring their children.

A historical perspective, unavailable in attachment discourses and child welfare practices, allowed new possibilities of an ethics of practice to emerge. First, we could see how the diagnosis of attachment failure, born as it was in a history of forced separation, continues to reproduce forced separation of Black families in different guises. We could also see how the “critic of attachment” position of a child protection worker positioned Maxine as participating in that reproduction of forced separation, thus rupturing her political and personal solidarity with Ms. M. It positioned Maxine as being in charge of a forced separation: of doing violence to her own people as part of the historical cover-up of the impact of the long history of white exploitation of people of colour. Maxine made extraordinary efforts to help Ms. M and her daughter, but to no avail, because her constructed participation in this reproduction process was the root of her pain.

Such critical analysis allows us to contemplate a major question at the heart of her practice: How can historical consciousness, left out of psychological discourses, contribute to forming relations of solidarity with our clients, thus enabling practice better aligned with justice? Such an analysis might allow us to ask the kind of questions that are the heart of social work ethics: How, for example, could we think differently about child welfare practices with black families if our work were guided first and foremost by a desire to find forms of practice that take into account centuries of trauma from racial injustice? I suggest that this question is a practical practice question which recognizes that our cherished fantasy that practice emanates from theory is rather grandiose in the face of the complex social and historical constructions that produce the moment of practice.

The second case study (Gorman, 2004) takes place during a practicum in a school setting. A 13-yr old girl, Tara, was referred to Ronni Gorman for counseling. Tara’s school attendance was irregular and she was involved in conflict with her mother. She engaged in low level self-mutilation and in sexual activity. Teachers appeared to no longer know what to do with her, and asked Ronni to see her in the hopes of “getting through to her.” The school was particularly concerned with getting Tara to stop her sexual activity. A conflict occurred between Ronni’s perspective and that of school personnel when Tara disclosed her pregnancy to Ronni. Ronni discussed it with her supervisor who felt obliged to inform other school personnel, to Ronni’s dismay.

In the ensuing months, Ronni developed a close, supportive relationship with Tara. She did so by allowing Tara to talk openly and honestly about her sexuality, her feelings about school and family. Ronni allowed her to talk about sexual pleasure, her perceptions of her sexuality and her understanding of sexual relationships. At no time did Ronni focus on “getting her to stop.”

Ronni’s practice with Tara was situated within her values about the need for libratory discourses of sexuality for girls. Ronni worked with Tara from a critique of prevention and risk education strategies normally used in dealing with girls’ sexuality. Indeed, Carol- Ann O’Brian (O'Brien, 1999) documents the history of prevention of sexuality as the dominate focus of social work literature related to youth sexuality. Such interventions are aimed at delaying sexual activity until “appropriate” ages and also educating around the risks of sexuality. Ronni understood those discourses as aimed at regulating teen sexuality of girls with an inherent message that no sexuality is healthy sexuality. Ronni’s anti-oppressive analysis focused on the disciplinary intent of social work’s history of excluding the existence of youth sexuality. Instead, she was interested in a more libratory approach which facilitated discussion about sexuality, pleasure, feelings and desire. Ronni’s approach had an explicitly political agenda: she opposed prevention discourses as ways of silencing female desire. Also, she was well-informed about the ways that prevention and risk education inherently set up a trajectory of sex as normatively heterosexual, “age appropriate” sexual experience. In other words, such a trajectory works to normalize a sequence of sexuality which ranges from the “right time” to the end-stage of heterosexual marriage. Ronni believed that such discourses silenced and disciplined not only young women such as Tara, but all young women’s diverse and fluid experiences of sexuality.

In class, we worked to identify the existence of two, opposing discourses: one was the prevention and risk education approach of the school and the other was Ronni’s libratory approach to girls and sexuality. We looked at how these conflicting discourses positioned Ronni, Tara and school personnel. Ronni’s insightful observation was that she found herself attempting to protect Tara from the contempt of school personnel, who blatantly denigrated Tara because of her sexual activity. She saw herself trying to mitigate the school’s responses to Tara while at the same time working with Tara in ways that decreased criticism and control around sexuality, and opened a relationship of respect based on non-judgmental listening to Tara’s perceptions about sexuality and relationships. Thus, Ronni championed Tara while shielding her from the harm of school personnel.

We then asked what was left out when discourses were set in opposition. In this case, those discourses were set up with the prevention and risk discourse as repressive and the validation of sexuality discourse as progressive and libratory for young women. I had to admit that I saw both discourse from my subject position as a mother, and had to rather sheepishly admit that I wouldn’t have wanted my thirteen year old daughter to be having sex at that age. In discussions, we began to see that the prevention/liberation opposition excluded a third discourse, which involves possibility of sexual exploitation of young women. Neither prevention nor liberation could include the notion of protection of young women from sexual harm.

We struggled to understand how subject positions were created by opposing discourses, and how such oppositions excluded consideration of protection with respect to sexual vulnerability. With the achievement of this “necessary distance” Ronni was able to formulate new possibilities for practice. In particular she called for educators to consider alliance with youth based on respect for youth’s own construction of their realities.

I would contend that youth are expressive and creative beings who would likely perceive themselves as benefited by the opportunity to reclaim the language within sexuality discourses which is presently being used to describe, and in some cases, subjugate them. Variant language constructions in which sexual exploration and health are balanced and encouraged as opposed to silenced can ultimately succeed in fostering a sense of recognition amongst youth what challenges discourses of shame and deviance. Acknowledging current terminology that socially regulates sexuality through ‘good girl/bad girl’ ideologies has the opportunity to be reconstructed in alliance with youth. If sexuality is open to be approached as fluid with respect to the variations which are absent from the current risk discourse, these variations will optimistically evolve outside those of deviance and difference (Gorman, 2004, p. 18).

Ronni sees such a health-based approach as capable of including protection from disease, harm, or sexual exploitation by its emphasis on openness, dialogue, and choice. In such a way, Ronni undoes the opposition between risk and liberation, and also revises her relationship to school personnel from that of shielding youth like Tara from harm, to calling on them to reconstruct the discourses through which girl’s sexuality is understood, and viewing them as potential resources in protecting Tara. Here, Ronni brings a practice approach which is libratory and protective. While she understands that such an approach is constructed — a fiction — it is a construction she chooses to empower because it is grounded in her social justice aspirations.

Why is this approach critical and what does critical do for us?

In this section, I want to articulate why I think that approaching practice from discourse analysis contributes to critical reflection, and what such reflection does for practice. When we reflect on what is left out of the discursive construction of our practice, we are “stepping back” from our immersion in such discourses as “reality” in order to examine whether our practice is being shaped in ways that contradict or constrain our commitments to social justice. This is why it is critical reflection. This distance from the immediate thought of practice is enabled by a focus on discursive boundaries, rather than the technical implementation of practice theories that are part of discursive fields. I suggest that we gain new vantage points from which to reconstruct practice theory in ways that are more consciously oriented to our social justice commitments. I understand these vantage points in the two case studies I have described in the four ways: 1) an historical consciousness, 2) access to understanding what is left out of discourses in use, 3) understanding of how actors are positioned in discourse, all leading to: 4) a new perspective which exposes the gap between the construction of practice possibilities and social justice values, thus allowing for field of limited and constrained choices which may either narrow the gap, or make clear the impossibility of options and choice in the particular case.

Historical consciousness

The hold of possessive individualism in the helping professions means that the target of practice is the individual, community, or family in the present . Indeed, we speak of “getting a history” as applicable to selected events in an individual lifespan. Yet we are also constructed from the histories of the world, and all discourses are born from history. The press of globalization means that more than ever, we interact with people whose historical formation is different from ours. Further, we interact within the constant presence of historical traumas in which we are all implicated. Maxine’s client, for example, comes to Canada seeking greater opportunity: opportunity that originated over two hundred years ago when my ancestors on the coast of Rhode Island traded with the Caribbean for goods produced by slave labour thus giving birth to the very American capitalism that created the need for Maxine’s and Ms. M’s migration in search of opportunity.

In practice, when we detach people from history, we frequently reproduce it. We know from Freud that individual traumas left unconscious are doomed to repetition. Historical trauma repeats itself in the small micro interactions of practice. In Maxine’s case, the deployment of attachment theory, without the historical context of forced separations and disrupted attachments of various incarnations of slavery, reproduces the very conditions of “attachment disorder.” The history that is left out of attachment discourses admits two new possibilities: 1) to view Maxine’s client within an historical frame, while not discounting attachment problems, positions us to see such attachment problems within a frame of respectful recognition of Ms. M. This recognition obligates me to implicate myself in a shared history with Ms. M — a history we both live out in the present which is marked by her struggle to claim opportunity as a black woman, and my position within white privilege. 2) Such recognition allows us to examine practice for the ways that history reproduces itself in our daily actions and reactions. We can raise questions about practices that may be outside such reproduction. In doing so, we increase our choices or at least, our awareness regarding how we participate in the creation of culture.

What is left out of the discourses in use

Discourses delineate what can be said within a given set of ideas so that critical practice is exercised when we try to look at what is excluded by a particular discourse in order to alternative viewpoints. These alternative viewpoints are important because discourses are structured through power relations so that the identification of what is outside prevailing stories may give us a better picture of how power operates.

In social work, critical practice is crucial because social work is a nexus where social contradictions are manifest. These contradictions are at work inside our subjectivity every day — it is not an exaggeration to say that our practice is at the mercy of contradictory forces. Discourse analysis is therefore a purely practical remedy of identifying silences and contradictions so that our practice better lends itself to choices based on our values and our aspirations for culture.

Ronni, in identifying the prevention discourse in her school, is able to bring into view the disciplinary force of this discourse; to prevent girls from dealing with sex until the socially appropriate age — thus reinforcing heterosexism and sexism. This vantage point opens opportunities for practice that work towards Ronni’s social justice goals.

It is important to consider the role of opposition here. Many times our investigations pointed to opposing discourses - discourses that counteract each other. These discourses are effects of power, usually when an opposing discourse is mobilized to resist another. It is important to understand how the opposition itself locks out practice opportunities. Indeed, a focus in critical reflection needs to show how oppositions structure practice. For example, Ronni mobilizes a libratory discourses as a way of resisting prevention discourses. On reflection, she sees that the opposition excludes aspects which both discursive positions require — the inclusion of protection. In identifying this, Ronni restructures her practice in light of what has previously been left out. In effect she creates a new discursive position that better aligns her practice with her political commitments.

Positionality

One of the advantages of identifying discourses-in-use in practice is that we gain access to how we are positioned within discourses. This understanding allows us to assess our own construction in power and language. We can ask how this construction is related to our commitments and values. We can also assess how discourses position us in relation to other professionals and to clients. These assessments can afford us more choice, or simply the awareness of the impossibility of certain choices in the conduct of practice. In turn, such assessments act against the internalization of the contradictions played out in social work practice.

Maxine considered how she was positioned both by discourses of professionalism and by the attachment discourses used to explain Ms. M. As a professional with statutory power, Maxine was given Caribbean family cases due to her “insider” status. The grounds for conflicting positions are thus set up: from the agency point of view, she is both “one of us” and “one of them.” Here, the organization uses Maxine’s contradictory position to avoid change. As “one of us,” she is expected to deploy white, Western knowledge with her Caribbean clients - clients she is given because of her “special knowledge.” In other words, she embodies the contradiction between professional expectations to deploy Eurocentric knowledge while also being positioned to deliver service to those who are an exception to that knowledge. This contradiction is internalized by Maxine in the form of her belief that she has failed Ms. M and that her monumental efforts did not make a difference in this case.

The knowledge she is expected to deploy is based on attachment theory — the personality damage that results from interrupted early attachment. This theoretical perspective creates discursive boundaries around caregiver and child. Class, race, culture, history are excluded as the focus on the dyad is retained as an explanation for family breakdown. When Maxine regards Ms. M. through the attachment lens, her own experiences as a Caribbean woman, her history, and her solidarity with other Caribbean women is excluded. It is a story that cannot be told within the reigning discourse of attachment. Thus, Maxine is positioned to assess and discipline Ms. M. She cannot find room for the very insider knowledge she is supposed to have. This is because that insider knowledge is knowledge of historical trauma, injustice, racism and white privilege, and it is certainly outside the boundaries of attachment discourses. Thus, Maxine as a professional is treated with disdainful suspicion by Ms. M. Maxine herself feels to blame for failure to make a difference with the case. Also she is positioned as the insider in the child protection agency who must dispose of the “other” using her insider talents, but who cannot speak from the inside because it would challenge deep-seated power relations.

Ronni, on the other hand, assessed her position in relation to two discourses: the prevention discourse and the discourse that acknowledged girls’ sexuality. These were oppositional discourses. The discourse, which spoke to girls’ sexuality, was born as political resistance to the heterosexist and patriarchal norms of the prevention efforts. Ronni aligned herself politically with resistance to heterosexism and patriarchy. In taking up that alignment, she positioned herself as Tara’s protector — her shield against school personnel with their regressive focus on prevention of acknowledgment of sexuality. Ronni came to see that this discursive position cancelled out the possibility of calling on school personnel as resources for Tara - resources that had the potential to protect her as a young girl with particular vulnerabilities. They also positioned Ronni in relations of opposition to school personnel. In this kind of opposition, chances for dialogue about complicated issues, chances for Ronni to promote change through communication of her perspective, and to use the experience of the school personnel for her own learning and growth were limited. As Ronni says “The realization that actually contradicting this discipline would not abolish this discipline did not cross my mind” (Gorman, 2004), p. 16).

Ronni’s analysis moved beyond opposition through a new discourse of health-oriented openness to girls sexuality in which protection is configured as part of healthy sexuality. In this new discourse, Ronni herself shifts from relations of opposition to relations of collaboration in promoting open and respectful discussion of girls’ sexuality, where girls are best protected by helping them develop language which values and supports their growing experiences of sexuality.

The assessment of new possibilities

Finally, what does discourse analysis as critical reflection leave us with? Here, I want to gather strands of the previous discussion. I am arguing that social work, because of its focus on marginalized people, is a concentrated site of social, political and cultural ambivalence and contradiction. Social workers are the bodies in the middle of this site and must act within the force field of contradictions. Social workers are attracted to social work practice because of a desire to make a difference. This desire is subjected to the strange twists and turns of which take place inside the institutions of practice. Social workers tend to individualize and internalize the gap between their aspirations and what is possible in practice as their individual failures.

Discourse analysis accesses questions that help make social contradictions and ambivalence visible and it opens conceptual space regarding one’s position within competing or dominant discourses. When we look outside the boundaries of discourses, we may discover practice questions which help us reflect on power and possibility. Openness to questions about the constitution of practice iscritical practice.

As the art of asking questions, dialectic proves its value because only the person who knows how to ask questions is able to persist in his questioning, which involves being able to preserve his orientation toward openness. The art of questioning is the art of questioning ever further --.i.e., the art of thinking” (Gadamer, 1992).

Such questioning opens up as social workers attempt to account for their own social construction within the cultural construct of social work. Social work is embedded is in history and is situated in a present which affords no settled practice, no technical fixes, no uncontested views of itself. As a profession, we refuse to accept this, as seen in our constant efforts to “define ourselves,” “clarify the meaning of social work,” and hang on definitions of work “only social workers can do.” Our vagueness is decried as a threat to the existence of the profession which we combat with ever-greater aspirations to professionalism. These reactions may have political worth, but they have the effect of occluding the inevitable messiness of our constructed place, thus leaving the field open for individual self-doubt and apology.

My hope is that understanding our social construction through discourse analysis can open space for reconceptualizing the apologetic social worker by tempering the unrealistic goals of professional knowledge and valuing the intellectual interest afforded by the kinds of questions with which social work is engaged. This intellectual interest can be found in the ways we re-experience value commitments through openness to the question at the heart of critical social work: What does social work have to do with justice?

Brookfield, S. (1996). Helping people learn what they do: Breaking dependence on experts. In N. Miller (Ed.), Working with Experience. London: Routledge.

Flax, J. (1992). The end of innocence. In J. Butler & J. Scott (Eds.), Feminists theorize the political (pp. 445-463). New York: Routledge.

Fook, J. (1999). Critical reflectivity in education and practice. In J. Fook (Ed.), Transforming social work practice: Postmodern critical perspectives. St. Leonards NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1992). Truth and method (J. W. a. D. G. Marshall, Trans. second revised edition ed.). New York: The Crossroad Publishing Corporation.

Gorman, R. (2004). Critical case study: My experience with Tara .Unpublished manuscript, Toronto. [email protected]

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Healy, K. (2000). Social work practices: Contemporary perspectives on change. London: Sage.

Mezirow, J. (1998). On Critical Reflection. Adult Education Quarterly, 48 (3), 185-198.

O'Brien, C.-A. (1999). Contested territory: Sexualities and social work. In A. Chambon & A. Irving & L. Epstein (Eds.), Reading Foucault for social work (pp. 131-155). New York: Columbia University Press.

Rossiter, A. (1996). A Perspective on Critical Social Work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 7(2), 23-41.

Rossiter, A. (2000). The professional is political: An interpretation of the problem of the past in solution-focused therapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(2), 150-161.

Rossiter, A. (2001). Innocence lost and suspicion found: Do we educate for or against social work? Critical Social Work, 2(1).

Scott, J. (1992). "Experience". In J. Butler & J. Scott (Eds.), Feminists Theorize the Political (pp. 22-40). New York: Routledge.

Spivak, G. (1990). The post-colonial critic: Interviews, strategies, dialogues . New York: Routledge.

Stamp, M. (2004). Case study: Lady Caribbean. Unpublished manuscript, Toronto. [email protected] .

Taylor, C., & White, S. (2000). Practising reflectivity in health and welfare: Making knowledge . Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Weinberg, L. (2004). Pregnant with possibility: Reducing ethical trespasses in social work practice with young single mothers. Unpublished Ph.D., University of Toronto, Toronto.

- Iriss Podcast

What do we mean by analysis?

Analysis in practice

Analysis is central to everyday social work practice and involves paying careful attention to what is going on in any situation in order to understand that situation and make recommendations for support. Analysis is an ongoing process that social workers are engaged in all of the time.

Analysis is of course also a product, a written record which captures key aspects of all the different parts of the analytic process – the thinking, listening and observing that social workers do. The written record of analysis involves selecting the most important details from all these aspects and writing in a way that makes these understandable to many different kinds of readers. Moving from analysis as process – a part of almost every moment of everyday practice and involving a wide range of professional skills, intuition and expertise – to analysis as a written product is central to the securing of services and providing good care for vulnerable young people and adults.

In our workshops exploring social work writing, the group discussed what analysis as a product looks like. Practitioners felt that good analysis has a number of key features, but that in everyday practice it can be challenging to produce written analysis that includes all features.

- Outcomes focused – short-, mid- and long-term outcomes

- States clearly what the outcomes or impacts will be and if these are positive or negative

- Clear history running through - it is sequential and measured

- Analysis provides the history of what’s happened and what’s been discussed

- Clear reasoning, decision making and planning, all this is clearly connected to/ by the information previously given

- Summarises and weighs up risks and risk factors, and shows protective factors, uses relevant risk tools

- Contains the right amount of detail

- Captures different perspectives in a non-judgemental way

- Brings in evidence, practice wisdom, information from other professionals, family, carers

- Explains what’s recorded and why

- Weighs up the likelihood or probability of change/ impacts

How it ‘reads’

- Writer has a good understanding of the issues

- Being able to get a sense of the service user and what they see as a priority

- It is clear and concise

- When required, analysis should be tailored to the requirement of the report / assessment and, distil the key information to inform the plan for the child / family.

“I feel like analysis is this thing, this concept. The best way I can describe it is that it’s like a butterfly, I can’t quite catch it to give a proper description. It’s holistic, it’s about layers. I’m constantly thinking about what is important and asking ‘what is someone else going to get from this?’. It’s about taking the information and making sure that it’s going to be meaningful to the next person who is reading it” Claire, Adult Social Work

The ethical principles underpinning written analysis

There is no one-stop-shop or template for writing ‘good analysis’. However, there are some ethical principles that underpin written analysis as part of ethical practice in social care.

Respect for persons

Respect for human rights, dignity and worth is captured by good analysis. In writing, the values of acceptance and respect for both the reader and the subject of the writing can be demonstrated by the language used. Respect for persons involves writing with sensitivity and is about being able to see the world from the viewpoints of others. Good analysis demonstrates thoughtful use of language that avoids labelling, stereotyping and cultural or other bias.

Professional integrity

Good analysis writing takes account of organisational requirements and legal obligations. It also means being mindful of professional boundaries and responsibilities. This integrity then leads good analysis to offer clearly articulated and justified decisions, while taking into account the broader social context. Accuracy in recording leads to a fair representation of a supported person’s point of view, allowing records to be shared in an open and direct way.

Accuracy, judiciousness and credibility

Good analysis provides full and accurate information about people’s circumstances and accurately records the information to give a clear understanding of their needs to other professionals working with them. It includes only essential and relevant details, and does not use emotive or derogatory language.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity is essential to social work practice and writing reflexively is part of good analysis. Writing explores not only what an experience was, but considers the meaning the writer attached to it, both at the time and subsequently, and how this meaning may influence practice in the future. Good analysis gives the reader a sense that the writer has a sense of ‘self’ and has made connections between ideas, feelings and memories of experience.

Social justice

Strong analysis in social work writing is one of the tools that a social worker can use to challenge injustice, particularly as it relates to policies and practices. Good analysis openly values people’s lived experiences, is critically reflective, connects with the audience, and draws attention to social injustices to advocate for social change. It can challenge negative discrimination and recognise diversity by using language that is inclusive and does not further stigmatise already marginalised people.

Adapted from Ethical Professional Writing in Social Work and Human Services. Donna McDonald, Jennifer Boddy, Katy O’Callaghan, Poll Chester (2015)Ethical Professional Writing in Social Work and Human Services, Ethics and Social Welfare, 9(4):1-16.

Iriss is a charitable company limited by guarantee. Registered in Scotland: No 313740. Scottish Charity No: SC037882. Registered Office: Brunswick House, 51 Wilson Street, Glasgow, G1 1UZ.

Social Work

- Video recordings of how to find resources

- Finding articles in journals

- Finding articles using databases

- Useful websites

- Reports, Inquiries & Legislation

- Critical thinking, writing and reflection

- Literature reviews a guide how to carry them out This link opens in a new window

- Evidence informed Social Work practice

- Functional Skills

- Referencing and understanding plagiarism This link opens in a new window

- Decolonalisation - what is it?

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: Diverse Library Resources

Critical thinking, reflection, reading and writing

Social Work students in particular need to develop their ability to think and reflect critically and provide critical analysis in their written work. If you feel you need to develop in this area or have had feedback on your assignments asking you to be more critical, you can get one to one help from the Writing Development team at the library. Alternatively you could attend or watch one of their pre recorded workshops on Critical Writing . Workshops are advertised on the library webpage .

Skills for Study

Critical thinking model

Plymouth University has devised a critical thinking model to help you reflect and analyse a critical incident and how this can be used in your critical writing. This video shows the basics of the model:

Critical thinking and writing resources

There are a selection of books on the Academic Writing webpage of the library to help you with critical thinking

Stella Cottrell, Critical Thinking Skills and and Kate Williams, Getting Critical are practical books that you can work through to improve your skills and gain confidence in this area. The other books listed are specific to critical reading and writing in Social Work.

Oxford Brookes University has developed a guide ' Be more critical ' aimed at Health and Social Care students.

Critical reflection resources

A selection of articles and books to help you reflect critically on your practice:

- Critical reflection: how to develop it in your practice

- << Previous: Study skills

- Next: Literature reviews a guide how to carry them out >>

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2024 4:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.lincoln.ac.uk/social_work

- Admin login

- ICT Support Desk

- Policy Statement

- www.lincoln.ac.uk

- Accessibility

- Privacy & Disclaimer

How To Write A Critical Analysis Essay With Examples

Declan Gessel

May 4, 2024

A Critical Analysis Essay is a form of academic writing that requires students to extract information and critically analyze a specific topic. The task may seem daunting, but with the right approach, it can become an exciting task.

Critical Analysis Essays help students improve their analytical skills and foster principles of logic. In this article, we are going to discuss how to write an essay and break it down for you. So sit back, relax, and enjoy the ride!

Table Of Content

What is a critical analysis essay, why the subject of your critical analysis essay is important, 5 reading strategies for critical analysis essay, building the body of your analysis, 5 things to avoid when writing your critical analysis essay, write smarter critical analysis essay with jotbot — start writing for free today.

When you write a critical analysis essay, you move beyond recounting the subject's main points and delve into examining it with a discerning eye. The goal? To form your own insights about the subject, based on the evidence you gather.

This involves dissecting and contemplating the author's arguments , techniques, and themes while also developing your own critical response. While forming your own conclusions may sound intimidating, it's a key aspect of fine-tuning your critical thinking skills and organizing your thoughts into a cohesive, argumentative response.

Key Skills in the Craft

This process consists of two key elements: understanding the core components of the subject and forming your own critical response, both supported by evidence. The first part involves grasping the subject's main arguments, techniques, and themes. The second part entails taking that knowledge and constructing your analytical and evaluative response.

Deconstructing the Subject

In other words, roll up your sleeves and get deep into the subject matter. Start by identifying the author's main point, deconstructing their arguments, examining the structure and techniques they use, and exploring the underlying themes and messages. By engaging with the subject on this level, you'll have a thorough understanding of it and be better prepared to develop your own response.

The Power of Evidence

Remember that evidence is your secret weapon for crafting a convincing analysis. This means going beyond summarizing the content and instead using specific examples from the subject to support your own arguments and interpretations. Evidence isn't just about facts, either; it can also be used to address the effectiveness of the subject, highlighting both its strengths and weaknesses.

The Art of Evaluation

Lastly, put your evaluation skills to work. Critically assess the subject's effectiveness, pinpointing its strengths and potential shortcomings. From there, you can offer your own interpretation, supported by evidence from the subject itself. This is where you put everything you've learned about the subject to the test, showcasing your analytical skills and proving your point.

Related Reading

• Argumentative Essay • Essay Format • Expository Essay • Essay Outline • How To Write A Conclusion For An Essay • Transition Sentences • Narrative Essay • Rhetorical Analysis Essay • Persuasive Essay

Let’s delve on the importance of understanding the Work you'll be analyzing:

Main Argument

When diving into a work, one must unravel the central point or message the author is conveying. All other analyses stem from this fundamental point. By identifying and comprehending the main argument, one can dissect the various elements that support it, revealing the author's stance or point of view.

Themes are the underlying concepts and messages explored in the subject matter. By venturing into the depths of themes, one can unravel the layers of meaning within the work. Understanding these underlying ideas not only enriches the analysis but also sheds light on the author's intentions and insights.

Structure & Techniques

Understanding how the work is built - be it a chronological story, persuasive arguments, or the use of figurative language - provides insight into the author's craft. Structure and techniques can influence the way the work is perceived, and by dissecting them, one can appreciate the intricacies of the author's style and the impact it has on the audience.

In critical analysis, understanding the context can add an extra layer of depth to the analysis. Considering the historical, social, or cultural context in which the work was created can provide valuable insights into the author's influences, intentions, and the reception of the work. While not always necessary, contextual analysis can elucidate aspects of the work that might otherwise go unnoticed.

To conduct a comprehensive critical analysis , understanding the work you'll be analyzing is the foundation on which all other interpretations rely. By identifying the main argument, themes, structure, techniques, and context, a nuanced and insightful analysis can be crafted. This step sets the stage for a thorough examination of the work, bringing to light the nuances and complexities that make critical analysis a valuable tool in literary and artistic exploration.

1. Close Reading: Go Deeper Than Skimming

Close reading is a focused approach to reading where you don't just skim the text. Instead, you pay close attention to every word, sentence, and detail. By doing this, you can uncover hidden meanings, themes, and literary devices that you might miss if you were reading too quickly. I recommend underlining or annotating key passages, literary devices, or recurring ideas. This helps you remember these important details later on when you're writing your critical analysis essay.

2. Active Note-Taking to Capture Important Points

When reading a text for a critical analysis essay, it's important to take active notes that go beyond summarizing the plot or main points. Instead, try jotting down the author's arguments, interesting details, confusing sections, and potential evidence for your analysis. These notes will give you a solid foundation to build your essay upon and will help you keep track of all the important elements of the text.

3. Identify Recurring Ideas: Look for Patterns

In a critical analysis essay, it's crucial to recognize recurring ideas, themes, motifs, or symbols that might hold deeper meaning. By looking for patterns in the text, you can uncover hidden messages or themes that the author might be trying to convey. Ask yourself why these elements are used repeatedly and how they contribute to the overall message of the text. By identifying these patterns, you can craft a more nuanced analysis of the text.

4. Consider the Author's Purpose

Authorial intent is an essential concept to consider when writing a critical analysis essay. Think about the author's goals: are they trying to inform, persuade, entertain, or something else entirely? Understanding the author's purpose can help you interpret the text more accurately and can give you insight into the author's motivations for writing the text in the first place.

5. Question and Analyze your Arguments

In a critical analysis essay, it's important to take a critical approach to the text. Question the author's ideas, analyze the effectiveness of their arguments, and consider different interpretations. By approaching the text with a critical eye, you can craft a more thorough and nuanced analysis that goes beyond a surface-level reading of the text.

Jotbot is your personal document assistant. Jotbot does AI note taking, AI video summarizing, AI citation/source finder, it writes AI outlines for essays, and even writes entire essays with Jotbot’s AI essay writer. Join 500,000+ writers, students, teams, and researchers around the world to write more, write better, and write faster with Jotbot. Write smarter, not harder with Jotbot. Start writing for free with Jotbot today — sign in with Google and get started in seconds.

Let’s delve on the essentials of building the body of your analysis:

Topic Sentence Breakdown: The Purpose of a Strong Topic Sentence

A powerful topic sentence in each paragraph of your critical analysis essay serves as a roadmap for your reader. It tells them the focus of the paragraph, introducing the main point you will explore and tying it back to your thesis. For instance, in an essay about the role of symbolism in "The Great Gatsby," a topic sentence might read, "Fitzgerald's use of the green light symbolizes Gatsby's unattainable dreams, highlighting the theme of the American Dream's illusion."

Evidence Integration: The Significance of Evidence from the Subject

To bolster your arguments, you need to use evidence from the subject you are analyzing. For example, in "To Kill a Mockingbird," when explaining Atticus Finch's moral compass, using a quote like, "You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view - until you climb into his skin and walk around in it," can back up your analysis. It proves that the character values empathy and understanding.

Textual Evidence: Integrating Quotes, Paraphrases, or Specific Details

When you quote or paraphrase text, ensure it directly relates to your analysis. For example, when discussing Sylvia Plath's use of imagery in "The Bell Jar," quote, "I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story." This paints a vivid picture for readers and helps solidify your point about the protagonist's feelings of entrapment.

Visual Evidence: Analyzing Specific Elements in the Artwork

If you are analyzing a painting, you can use visual details like color, lines, or symbolism as evidence. For instance, if exploring Van Gogh's "Starry Night," you could delve into the calming effect of the swirls in the sky or the stark contrast between the bright stars and the dark village below. This visual evidence helps explain the painting's emotional impact on viewers.

Analysis & Explanation: The Importance of Going Beyond Evidence Presentation

When examining evidence, don't stop at merely presenting it. Analyze how it supports your thesis. For instance, when exploring the role of the conch in "Lord of the Flies," after showing how it represents order, explain how its loss signals the boys' descent into savagery. By unpacking the evidence's meaning, you help readers understand why it matters and how it connects to your overall argument.

• Words To Start A Paragraph • Essay Structure • Types Of Essays • How To Write A Narrative Essay • Synthesis Essay • Descriptive Essay • How To Start Off An Essay • How To Write An Analytical Essay • Write Me A Paragraph • How To Write A Synthesis Essay

1. Avoiding Summary vs. Analysis Pitfalls

When crafting a critical analysis essay, it's crucial not to fall into the trap of merely summarizing the subject without offering your own critical analysis. A summary merely recaps the content, while an analysis breaks down and interprets the subject. If you overlook this vital distinction, your essay will lack the depth and insight that characterize a strong critical analysis. Ensure your critical analysis essay doesn't read like an extended book report.

2. Steering Clear of Weak Thesis Statements

A critical analysis essay lives and dies on the strength of its thesis statement, the central argument that guides your analysis. A weak or vague thesis statement will result in an unfocused essay devoid of direction, leaving readers unclear about your point of view. It's essential to craft a thesis statement that is specific, arguable, and concise, setting the tone for a thoughtful and illuminating analysis.

3. Using Evidence is Key

The use of evidence from the subject matter under analysis is instrumental in substantiating your critical claims. Without evidence to back up your assertions, your analysis will appear unsubstantiated and unconvincing. Be sure to provide detailed examples, quotes, or data from the text under scrutiny to support your analysis. Evidence adds credibility, depth, and weight to your critical analysis essay.

4. The Importance of Clear and Supported Analysis

A successful critical analysis essay goes beyond simply presenting evidence to analyzing its significance and connecting it to your central argument. If your essay lacks clear analysis, readers won't understand the relevance of the evidence you present. Go beyond description to interpret the evidence, explaining its implications and how it supports your thesis. Without this analysis, your essay will lack depth and will not persuade your audience.

5. Addressing Counter Arguments

In a critical analysis essay, it's vital to acknowledge and engage with potential counterarguments. Ignoring opposing viewpoints undermines the credibility of your essay, presenting a one-sided argument that lacks nuance. Addressing counter arguments demonstrates that you understand the complexity of the issue and can anticipate and respond to objections.

By incorporating counterarguments, you strengthen your analysis and enhance the overall persuasiveness of your critical essay.

Jotbot is an AI-powered writing tool that offers a wide range of features to assist writers in producing high-quality written content efficiently. These features include AI note-taking, video summarization, citation and source finding, generating essay outlines, and even writing complete essays. Jotbot is designed to streamline the writing process, enabling writers to create content more effectively and quickly than traditional methods.

AI Note-Taking

Jotbot's AI note-taking feature helps writers collect and organize information in a structured manner. By enabling writers to jot down key points and ideas during research or brainstorming sessions, Jotbot ensures that important details are not missed and can be easily accessed during the writing process.

AI Video Summarization

The AI video summarization feature of Jotbot allows writers to input videos for summarization and analysis. Jotbot’s AI engine processes the content of the video and provides a concise summary. This feature is particularly useful for writers who need to reference video content in their work but may not have the time to watch the entire video.

AI Citation/Source Finder

Jotbot's AI citation and source finding feature helps writers accurately reference and cite sources in their work. By analyzing the text and identifying key information, Jotbot streamlines the citation process, reducing the time and effort involved in finding and citing sources manually.

AI Outlines for Essays

Jotbot generates AI outlines for essays based on the writer's input. These outlines provide a structured framework that writers can use to organize their thoughts and ideas before beginning the writing process. By creating a roadmap for the essay, Jotbot helps writers maintain focus and coherence throughout their work.

AI Essay Writer

Jotbot's AI essay writer feature can generate complete essays based on the writer's input and preferences. By analyzing the given information, Jotbot constructs an essay that meets the writer's criteria, enabling users to create high-quality content quickly and efficiently. With its advanced AI capabilities, Jotbot helps writers write more, write better, and write faster.

• How To Write A Personal Essay • Chat Gpt Essay Writer • How To Write An Outline For An Essay • What Makes A Good Thesis Statement • Essay Writing Tools • How To Write A 5 Paragraph Essay • How To Write A Rhetorical Analysis Essay • First Person Essay • How To Write A Header For An Essay • Memoir Essay • Formula For A Thesis Statement

Trusted by 500,000+ Students

Your documents, supercharged with AI.

Once you write with JotBot, you'll never want to write without it.

Start writing for free

Your personal document assistant.

Start for free

Press enquiries

Influencer Program

Affiliate Program

Terms & Conditions

Privacy policy

AI Source Finder

AI Outline Generator

How to Use JotBot AI

AI Note Taker

AI Video Summarizer

AI YouTube Video Summarizer

© 2023 JotBot AI by SLAM Ventures, LLC all rights reserved

© 2023 SLAM Ventures, LLC

Home » PCF 6: Critical Reflection & Analysis

PCF 6: Critical Reflection & Analysis

CRITICAL REFLECTION AND ANALYSIS – Apply critical reflection and analysis to inform and provide a rationale for professional decision-making.

Social workers critically reflect on their practice, use analysis, apply professional judgement and reasoned discernment. We identify, evaluate and integrate multiple sources of knowledge and evidence. We continuously evaluate our impact and benefit to service users. We use supervision and other support to reflect on our work and sustain our practice and wellbeing. We apply our critical reflective skills to the context and conditions under which we practise. Our reflection enables us to challenge ourselves and others, and maintain our professional curiosity, creativity and self-awareness.

More tools coming soon…

PCF 6: Tool 2 – Cake model for reflecting on an intervention/incident

PCF 6: Tool 3 – Suggested Critical Incident prompts

PCF 6: Tool 5 – Knowns / Unknowns exercise

PCF 6: Tool 6 – Template for Critical Incident Analysis

PCF 6: Tool 8 – Personal Reflective Model

- About Our Partnership

- The Teaching Partnership Team

- People with Lived Experience

- The Teaching Consultants

- Upcoming Training and Events

- Step Up to Social Work

- Social Work FAQs

- About Continuing Professional Development (CPD)

- Accredited CPD courses

- CPD Frameworks and Training Opportunities

- SWE video: How to…Record continuing professional development (CPD)

- Professional Standards

- External Publications

- Publications about Teaching Partnerships

- Newsletters

- Recordings of Online Events

- Interview Tips

- Practice Education in our TP

- Practice Education Resources

- PCF Toolkit

- Practice Education Workshops

- Practice Education Updates

- Support for me

- Support for my team

- Wellbeing Articles

- Share Point

- Anti-Racism

- Teaching Partnership Equality Statement

Student selection

Ensure the highest calibre of social work students with the attributes, competencies and passion needed to thrive in the profession are recruited to our academic programmes.

Curriculum development

Develop a curriculum that aligns with local need and is grounded not only in research and the CSWs’ KSS, but also in practice.

Readiness for practice

Give students the experience and support they need to ensure they are ready to practice within our region as Newly Qualified Social Workers.

Academics in practice

Ensure practice across our region is consistently informed by theory and research and that academics’ teaching is equally informed by practice.

Regional progression and development

Create regional progression pathways and CPD opportunities capable of attracting and retaining the best and brightest social workers in the UK.

Future workforce

Better understand our regional labour market to enable us to develop a robust plan to meet our partnership’s current and future workforce demands.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Critical Analysis

Definition:

Critical analysis is a process of examining a piece of work or an idea in a systematic, objective, and analytical way. It involves breaking down complex ideas, concepts, or arguments into smaller, more manageable parts to understand them better.

Types of Critical Analysis

Types of Critical Analysis are as follows:

Literary Analysis

This type of analysis focuses on analyzing and interpreting works of literature , such as novels, poetry, plays, etc. The analysis involves examining the literary devices used in the work, such as symbolism, imagery, and metaphor, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Film Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting films, including their themes, cinematography, editing, and sound. Film analysis can also include evaluating the director’s style and how it contributes to the overall message of the film.

Art Analysis

This type of analysis involves examining and interpreting works of art , such as paintings, sculptures, and installations. The analysis involves examining the elements of the artwork, such as color, composition, and technique, and how they contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

Cultural Analysis