Essay on These Days Exposure to Television and Internet

Students are often asked to write an essay on These Days Exposure to Television and Internet in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on These Days Exposure to Television and Internet

Introduction.

These days, exposure to television and the internet is a common part of our lives. They are powerful tools that provide information and entertainment.

Television Exposure

Television is a source of learning and amusement. It offers a variety of shows, from educational programs to cartoons, which can influence a child’s thoughts and behavior.

Internet Exposure

The internet is a vast resource. It’s used for research, communication, and entertainment. However, it also has potential risks like cyberbullying and exposure to inappropriate content.

While television and internet hold immense potential, it’s important to use them responsibly. Parents and teachers should guide children in their usage.

250 Words Essay on These Days Exposure to Television and Internet

The digital age: television and internet exposure.

In the contemporary world, exposure to television and the internet has become a ubiquitous aspect of daily life. This phenomenon, driven by constant technological advancements, has profound implications on individuals and societies.

Television: A Double-Edged Sword

Television, once the primary source of information and entertainment, has evolved significantly. While it offers educational content and a window into global cultures, excessive exposure can lead to sedentary lifestyles and passive consumption of information. It’s crucial to strike a balance between beneficial and detrimental use.

Internet: A Web of Possibilities

The internet, on the other hand, is a vast, interactive platform offering a wealth of information and opportunities for social connection. It empowers users to create, share, and access content. However, it also presents challenges, including misinformation, cyber threats, and the potential for addiction.

Implications for Society

The effects of these technologies on society are multifaceted. They have the potential to foster global connections, democratize information, and stimulate creativity. Conversely, they can also contribute to social isolation, mental health issues, and the spread of false information.

Conclusion: Striking the Balance

In conclusion, the exposure to television and internet is a complex issue requiring careful navigation. It’s crucial to harness the potential of these technologies while remaining vigilant of their risks. As digital citizens, we must strive to use these tools responsibly, promoting their positive aspects and mitigating their negative impacts.

500 Words Essay on These Days Exposure to Television and Internet

The evolution of media exposure: television and internet.

In the contemporary digital age, exposure to television and the internet has become an integral part of our daily lives. The evolution of these media platforms has revolutionized the way we consume information, shaping societal norms and individual behaviors.

Television: The Traditional Medium

Television, as a traditional medium, has been a primary source of entertainment and news for decades. It has played a pivotal role in shaping public opinion, promoting cultural values, and spreading awareness about global events. Television’s power lies in its ability to create a shared experience, a collective consciousness that transcends geographical boundaries. However, the advent of the internet has disrupted television’s monopoly, introducing a new dynamic in media consumption.

Internet: The Digital Revolution

The internet has emerged as a game-changer, democratizing access to information and transforming the way we communicate. The digital revolution has brought about a paradigm shift in our media consumption habits. With the internet, information is now available at our fingertips, anytime, anywhere. Unlike television, which offers a one-way communication channel, the internet fosters interactive communication, allowing users to not only consume but also create and share content.

The Confluence of Television and Internet

The convergence of television and the internet has given rise to new content formats and platforms. Streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu have revolutionized the way we consume television content, offering a personalized, on-demand viewing experience. This integration has blurred the lines between television and the internet, creating a hybrid media environment.

Implications of Media Exposure

The increased exposure to television and the internet has profound implications. On the positive side, it has enhanced our access to information, promoting global awareness and cultural exchange. It has also democratized content creation, giving voice to marginalized communities and fostering social change.

However, the downside cannot be overlooked. The overexposure to media can lead to information overload, affecting our mental health. The proliferation of fake news and misinformation on the internet poses a threat to societal harmony. Furthermore, the addictive nature of digital media can lead to unhealthy habits and lifestyle changes.

Conclusion: A Balanced Approach

In conclusion, while television and the internet have significantly enriched our lives, it is essential to adopt a balanced approach to media consumption. As informed consumers, we must critically evaluate the information we consume and be mindful of our screen time. The challenge lies in leveraging the benefits of these media platforms while mitigating their potential drawbacks. The future of media consumption will hinge on our ability to navigate this digital landscape responsibly and mindfully.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Internet Influence on Kids

- Essay on Internet a Boon or a Bane

- Essay on Importance of Computer

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Listening Tests

- Academic Tests

- General Tests

- IELTS Writing Checker

- IELTS Writing Samples

- Speaking Club

- IELTS AI Speaking Test Simulator

- Latest Topics

- Vocabularying

- 2024 © IELTS 69

These days exposure to television and internet is having bad influence on children.

IELTS essay These days exposure to television and internet is having bad influence on children.

- Structure your answers in logical paragraphs

- ? One main idea per paragraph

- Include an introduction and conclusion

- Support main points with an explanation and then an example

- Use cohesive linking words accurately and appropriately

- Vary your linking phrases using synonyms

- Try to vary your vocabulary using accurate synonyms

- Use less common question specific words that accurately convey meaning

- Check your work for spelling and word formation mistakes

- Use a variety of complex and simple sentences

- Check your writing for errors

- Answer all parts of the question

- ? Present relevant ideas

- Fully explain these ideas

- Support ideas with relevant, specific examples

- ? Currently is not available

- Meet the criteria

- Doesn't meet the criteria

- 6.5 band Many people believe that teenagers nowadays are facing more problems and difficulties than their parents faced at the same age. However, others think that both generations have to deal with equally challenging problems, yet in different contexts. It is supposed that teenagers these days are prone to confront more burdensome issues than the previous generation of youngsters did. Nevertheless, some people assume that each generation needs to get to grips with their particular troubles. This essay presents both sides of the debate. Initially, ...

- 6 band Death penalty is good solution to crime. Do agree with or disagree with Some people believe that penalty death should reserved for dangerous criminals like those who murdered and killed people. in my opinion, I am completely with disagreement this ideas and I would outline my reasons in the forthcoming paragraphs. First, I believe that death penalty shouldn't be so ...

- The most intimate temper of a people, its deepest soul, is above all in its language. Jules Michelet

- 6 band The extinction of species and biodiversity due to human activities. Despite knowing about the significance of biodiversity for a long period of time, human activities have caused massive extinctions of diverse species. Deforestation and waste in nature are the major problems to extinction of species and biodiversity. This essay is going to examine the major problem ...

- 6 band Do you think online media such as social networks and blogs have mainly improved our lives, or have they changed our lives in a negative ways? I partly concur that online media such as Facebook or Instagram have principally enhanced human lives. The following analyses can explain the reasons. Firstly, online media such as Facebook or Twitter can benefit from communication. They help to connect with people around the world, such as chattin ...

- Learning another language is not only learning different words for the same things, but learning another way to think about things. Flora Lewis

- 6 band Everyone should learn to play a musical instrument. ’ Music has been accompanying mankind since ancient times, and the question of whether everyone should learn to play a musical instrument is one of the important issues of the time. While some people think that everyone should have a good understanding of music and know how to play some musical instru ...

- 5 band An increasing number of people choose to have cosmetic surgery inorder to improve their appearance. why do people want to change the way they look? . Is it positive or negative development In this day and age people want to look attractive so they choose the path of cosmetic surgery according to my point of view it is an negative development Many people think that they want to look more smart and attractive as compared to there natural appearance. The main use of cosmetic surgery is p ...

- Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going. Rita Mae Brown

Climate One

Listen live.

BBC World Service

The latest news and information from the world's most respected news source. BBC World Service delivers up-to-the-minute news, expert analysis, commentary, features and interviews.

- Home & Family

Television has a negative influence on kids and should be limited

- Leona Thomas

Boy with remote control (image courtesy of Shutterstock.com)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Speak Easy

Thoughtful essays, commentaries, and opinions on current events, ideas, and life in the Philadelphia region.

You may also like

Finding our family’s roots through the ‘sepia rainbow’

Genealogy often looks like thumbing through old documents and pictures, but what story does skin color tell about family lineage?

Study shows new infant RSV antibody shot is highly effective. Delaware Valley pediatricians are hopeful for more protections next fall

A recent study by the CDC showed the antibody shot prevented RSV hospitalization in 90% of infants.

2 weeks ago

UPenn study helps caregiver coaches extend autism care beyond therapy sessions

AT PEACE Study supports providers who coach parents of children with autism on how to implement therapy strategies into their daily routines.

4 weeks ago

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

Nowadays television and the Internet have a greater influence on children's behavior than their parents. To what extent do you agree or disagree?

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Writing9 with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

- Check your IELTS essay »

- Find essays with the same topic

- View collections of IELTS Writing Samples

- Show IELTS Writing Task 2 Topics

Some people say that advertising encourages us to buy things we don't really need. Others say that advertisements tells us about new products that may improve our lives. Which viewpoint do you agree with? Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience.

Behaviour in schools is getting worse. explain the cause of this problem and suggest some possible solutions, tourists damage many historical places, making them harder to preserve. what are some of reasons for this suggest some ways to resolve this problem., many cars nowadays are driven by computers, not people. do you think the advantages of autonomous cars outweigh the disadvantages, we cannot help everyone in the world that needs help, so we should only be concerned with our own communities and countries.to what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- For authors

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 83, Issue 4

- The effects of television on child health: implications and recommendations

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Miriam E Bar-on

- Department of Pediatrics, Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine, 2160 South First Avenue, Maywood, IL 60153, USA

- Prof. Bar-on email: mbar{at}wpo.it.luc.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.83.4.289

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

The exposure of American children and adolescents to television continues to exceed the time they spend in the classroom: 15 000 hours versus 12 000 hours by the time they graduate. 1 According to recent Nielsen data, the average child and/or adolescent watches an average of nearly three hours of television per day. 2 These numbers have not decreased significantly over the past 10 years. 3 By the time a child finishes high school, almost three years will have been spent watching television. 1 This figure does not include time spent watching video tapes or playing video games. 4

Based on surveys of what children watch, the average child annually sees about 12 000 violent acts, 5 14 000 sexual references and innuendos, 6 and 20 000 advertisements. 7 Children and adolescents are especially vulnerable to the messages communicated through television which influence their perceptions and behaviours. 8 Many younger children cannot discriminate between what they see and what is real. Although there have been studies documenting some prosocial and educational benefits from television viewing, 9 , 10 significant research has shown that there are negative health effects resulting from television exposure in areas such as: violence and aggressive behaviour; sex and sexuality; nutrition and obesity; and substance use and abuse patterns. To help mitigate these negative health effects, paediatricians need to become familiar with the consequences of television and begin providing anticipatory guidance to their patients and families. 10 In addition, paediatricians need to continue their advocacy efforts on behalf of more child appropriate television.

In this review, we will describe the effects of television on children and adolescents. In addition, we will make recommendations for paediatricians and parents to help address this significant issue.

Prosocial and educational benefits

Studies from the early 1970s have shown that children imitate prosocial behaviour. These imitated behaviours included altruism, helping, delay of gratification, and high standards of performance when children are exposed to models exhibiting these behaviours. Friedrich and Stein provided evidence that children learned prosocial content of the television programmes and were able to generalise that learning to a number of real life situations. 9 In addition, they were also able to show that prosocial programmes increased helping behaviour in situations similar to and different from those shown on television.

Violence and aggressive behaviour

Young people view over 1000 rapes, murders, armed robberies, and assaults every year sitting in front of the television set. 11 Recently published, the three year, National Television Violence Study examined nearly 10 000 hours of television programming and found that 61% contained violence. 12-14 Children's programming was found to be the most violent. In addition, 26% (of the 61%) involved the use of guns. Portrayals of violence are usually glamorised and perpetrators often go unpunished. Another venue in which a significant amount of violence is portrayed is in rock music videos, which are viewed heavily by adolescents. In a comprehensive content analysis of these music videos, DuRant et al showed that 22.4% of all rap videos contained violent acts, and weapon carrying was depicted in 25% of them. 15

Numerous studies, including longitudinal research, 16 , 17 have shown a relation between children's exposure to violence and their own violent and aggressive behaviours. Many studies have documented the role of television in fostering violent behaviours among children. 18 , 19 Two recent meta-analyses investigating the relation between violence viewed on television and aggressive behaviour in children concluded that exposure to portrayals of violence on television was associated consistently with children's aggressive behaviours. 20 , 21

Sex and sexuality

American television, both programming and advertising, are highly sexualised in their content. Each year, children and adolescents view 14 000 sexual references, innuendoes, and jokes, of which less than 170 will deal with abstinence, birth control, sexually transmitted diseases, or pregnancy. 22 What has been traditionally described as the “family hour” (8–9 pm) now contains more than eight sexual incidents per hour, more than four times as much as in 1976. 23 Nearly one third of family hour shows contain sexual references, and the incidence of vulgar language has increased greatly. 24 In addition, soap operas, a genre highly viewed by adolescents, show extramarital sex eight times more commonly than sex between spouses. 11 At the present time there have only been four studies examining the relation between early onset of sexual intercourse and television viewing. However, there are numerous studies which illustrate television's powerful influence on teenagers' sexual attitudes, values, and beliefs. 25 , 26 Teens rank the media second only to school sex education programmes as a leading source of information about sex. 26

Nutrition and obesity

Over the past three decades the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents has increased and fitness has decreased. 27 Television viewing affects both fatness and fitness and multiple studies point to television viewing as one cause of childhood obesity. 28-31 Two primary mechanisms for this relation have been suggested: reduced energy expenditure from displacement of physical activity and increased dietary energy intake, either during viewing or as a result of food advertising.

The association between television viewing and food consumption can be explained, in part, by the frequent references to food or the consumption of food that occurs during both commercials and programmes. 11 Breakfast cereals, snacks, and fast foods are among the most heavily advertised products on television programmes aimed at children, and tend to have higher energy density than other products such as fruits or vegetables which are less frequently advertised. 30 The amount of time spent viewing television directly correlates with the request, purchase, and consumption of foods advertised on television. 11

Furthermore, obesity occurs among televised characters far less frequently than in the general population. Because the characters on television eat or talk about food so frequently, the implicit message may be that it is possible to eat frequently and remain thin. 32 Likewise, the almost exclusive presence of very thin, particularly female, television characters may contribute to the notion that the ideal body type is that of the women and adolescents shown; this may contribute to the culture wide obsession with thinness.

Tobacco and alcohol use and abuse

Increasingly, media messages and images, not necessarily direct advertising, are normalising and glamorising the use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs. Tobacco manufacturers spend $6 billion per year and alcohol manufacturers $2 billion per year to entice youngsters into consuming their products. Content analysis has found that alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs are present in 70% of prime time network dramatic programmes and half of all music videos. 33 The prominence of alcohol in prime time television applies to all characters, including adolescents, where negative characteristics are often applied. However, many adults shown to consume alcohol have positive personality characteristics. 34 Popular movies, frequently shown during the “family hour”, often show the lead or likeable characters using and enjoying tobacco and alcohol products. 35 , 36 In addition to programming, children and adolescents view approximately 20 000 advertisements each year, of which nearly 2000 are for beer and wine. 37 For every public service announcement, adolescents will view 25–50 beer commercials.

Research indicates that the combined 8 billion dollars which the tobacco and alcohol industries use every year to pitch their product to the American public has a significant impact on adolescents' beliefs and attitudes about smoking and drinking and may actually influence their consumption as well. Correlational studies have shown a small but positive relation between advertising exposure and consumption. 38-41 Furthermore, advertising exposure appears to influence initial drinking episodes which in turn contribute to excessive drinking and abuse. 39 The evidence, however, to increased consumption, is strongest regarding cigarette advertising and promotions. 42 , 43 A recent longitudinal study found that an estimated one third of all adolescent smoking could be causally related to tobacco promotional activities. 44

Recommendations for parents and paediatricians

As has been shown, there is a significant amount of literature to support the connection between adverse outcomes and exposure to television. There are ways to help attenuate the effects of television “promotion” of harmful activities and substances. They range from controlling the way children and adolescents view television to more effective office counselling and public health activism. The American Academy of Pediatrics, through its policy statements has taken a leadership role in making recommendations for both parents and paediatricians. 5 , 6 , 45 , 46

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PARENTS

Parents are often not familiar with what their children are viewing on television, nor do they control the television which they watch. 47 In addition, parents generally underestimate the amount of time their children spend viewing television. A recent study found that 32% of 2–7 year olds, 65% of 8–13 year olds, and 65% of 14–18 year olds have television sets in their bedrooms. 3 Furthermore, two 1997 surveys, with a sample size of nearly 1500 parents, found that less than half of them report “always watching” television with their children. 47 Co-viewing is thought to be an effective mechanism for mediating untoward effects of television viewing: an adult, watching a programme with a child and discussing it with him/her, serves simultaneously as a values filter and a media educator. 35 Based on this information, and the data available, the American Academy of Pediatrics 5 , 45 recommends that parents should:

Participate in the selection of programmes to be viewed

Co-view and discuss content with children and adolescents

Teach critical viewing skills to their children and adolescents

Limit and focus time spent viewing television to less than one to two hours per day

Be good media role models for their children and adolescents

Emphasise alternative activities

Remove television sets from children's and adolescents' bedrooms

Avoid using the television as an “electronic babysitter”.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PAEDIATRICIANS

With the known unhealthy effects of media on children and adolescents, it is crucial that paediatricians are aware and become knowledgeable about the media's influence on their patients. 9 Paediatricians need to be able to educate their patients' parents and advocate for improved, healthier media. 5 As part of health supervision visits, paediatricians also need to begin taking a media history and using the media history form developed by the Academy (table 1 ). 45 , 48 This tool enables young people and parents to examine their media habits and allows paediatricians to focus on areas of concern and offer counsel and support. 45 In addition, paediatricians can work with patients to help them understand that what they view on television is not “real” and that the purpose of advertisements is to sell them products. These premises of media education have been implemented in programmes with documented success. 49 , 50 Review of the available literature has enabled the Academy to make the following recommendations for paediatricians 5 , 45 , 47 :

Become educated about the public health risks of television exposure and share this information with their patients, families, and the community

Incorporate questions about television use into routine visits including use of the Academy's media history form

Include anticipatory guidance about television to their patients and their families at health supervision visits

Encourage parents to avoid television viewing for children under the age of 2 years

Serve as role models by using television sets and videocassette recorders in their waiting rooms for educational programming only

Advocate for improved media by writing to local stations, national networks, Hollywood studios, and the Federal Communications Commission

Promote media education as a means to help mitigate some of the unhealthy effects of television

Advocate for mandatory media education programmes with known effectiveness in the schools.

- View inline

Media history form: television focused questions 1-150

Conclusions

Although this review primarily focused on the unhealthy effects of television viewing on children and adolescents, some television programming has been shown to promote prosocial behaviours and have positive educational effects in young children. However, these programmes are in the minority and are mainly targeted to very young children (3–5 year olds). There are effective methods which can be used to lessen the negative influences of television. The primary method, besides turning off the television, is the introduction of media education to patients and their families. This introduction can be accomplished through many settings including the paediatrician's office, the school, and the community. The Academy's Media Matters Campaign is an example of such an integrated initiative to disseminate media education. It is important that paediatricians and parents jointly implement prevention campaigns and strategies. The effect on both children and adolescents, and the community will be much greater with a joint effort.

- Strasburger VC

- ↵ Nielsen Media Research, New York, 1998.

- Roberts DF ,

- Rideout VJ ,

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Communications

- Gerbner G ,

- Signorielli N

- Friedrich LK ,

- Corporate Research Department

- DuRant RH ,

- Singer MI ,

- Miller DB ,

- Flannery DJ ,

- Frierson T ,

- Chachere JG

- Harris L and Associates

- ↵ Parents Television Council. The family hour: no place for your kids . Los Angeles, CA: Parents Television Council, 8 May 1997.

- ↵ Kaiser Family Foundation . The 1996 Kaiser Family Foundation Survey on Teens and Sex. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 24 June 24 1996.

- Troiano RP ,

- The Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania

- Gortmaker SL

- Gortmaker SL ,

- Peterson K ,

- Colditz GA ,

- Robinson TN

- Hammond KM ,

- ↵ Gerbner G, Ozyegin N. Alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs in entertainment television, commercials, news, “reality shows”, movies and music channels. Report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ, 20 March 1997.

- Mathios A ,

- Bisogni C ,

- Goldstein AO ,

- Robinson TN ,

- Centers for Disease Control

- Institute of Medicine

- Pierce JP ,

- Gilpin EA ,

- Farkas AJ ,

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Public Education

- Strasburger VC ,

- Donnerstein E

- Anastassea-Vlachou K ,

- Fryssira-Kanioura H ,

- Papathanasiou-Klontza D ,

- Xipolita-Zachariadi A ,

- Matsaniotis N

- Singer DG ,

- Austin EW ,

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Essay on Television for Students and Children

500+ words essay on television.

Television is one of the most popular devices that are used for entertainment all over the world. It has become quite common nowadays and almost every household has one television set at their place. In the beginning, we see how it was referred to as the ‘idiot box.’ This was mostly so because back in those days, it was all about entertainment. It did not have that many informative channels as it does now.

Moreover, with this invention, the craze attracted many people to spend all their time watching TV. People started considering it harmful as it attracted the kids the most. In other words, kids spent most of their time watching television and not studying. However, as times passed, the channels of television changed. More and more channels were broadcasted with different specialties. Thus, it gave us knowledge too along with entertainment.

Benefits of Watching Television

The invention of television gave us various benefits. It was helpful in providing the common man with a cheap mode of entertainment. As they are very affordable, everyone can now own television and get access to entertainment.

In addition, it keeps us updated on the latest happenings of the world. It is now possible to get news from the other corner of the world. Similarly, television also offers educational programs that enhance our knowledge about science and wildlife and more.

Moreover, television also motivates individuals to develop skills. They also have various programs showing speeches of motivational speakers. This pushes people to do better. You can also say that television widens the exposure we get. It increases our knowledge about several sports, national events and more.

While television comes with a lot of benefits, it also has a negative side. Television is corrupting the mind of the youth and we will further discuss how.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How Television is Harming the Youth

Additionally, it also makes people addict. People get addicted to their TV’s and avoid social interaction. This impacts their social life as they spend their time in their rooms all alone. This addiction also makes them vulnerable and they take their programs too seriously.

The most dangerous of all is the fake information that circulates on news channels and more. Many media channels are now only promoting the propaganda of the governments and misinforming citizens. This makes causes a lot of division within the otherwise peaceful community of our country.

Thus, it is extremely important to keep the TV watching in check. Parents must limit the time of their children watching TV and encouraging them to indulge in outdoor games. As for the parents, we should not believe everything on the TV to be true. We must be the better judge of the situation and act wisely without any influence.

{ “@context”: “https://schema.org”, “@type”: “FAQPage”, “mainEntity”: [{ “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “How does television benefit people?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”: “Television offers people a cheap source of entertainment. It saves them from boredom and helps them get information and knowledge about worldly affairs.” } }, { “@type”: “Question”, “name”: “What is the negative side of television?”, “acceptedAnswer”: { “@type”: “Answer”, “text”:”Television has a negative side to it because it harms people’s health when watched in excess. Moreover, it is the easiest platform to spread fake news and create misunderstandings between communities and destroy the peace and harmony of the country.”} }] }

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Family Life

Constantly Connected: How Media Use Can Affect Your Child

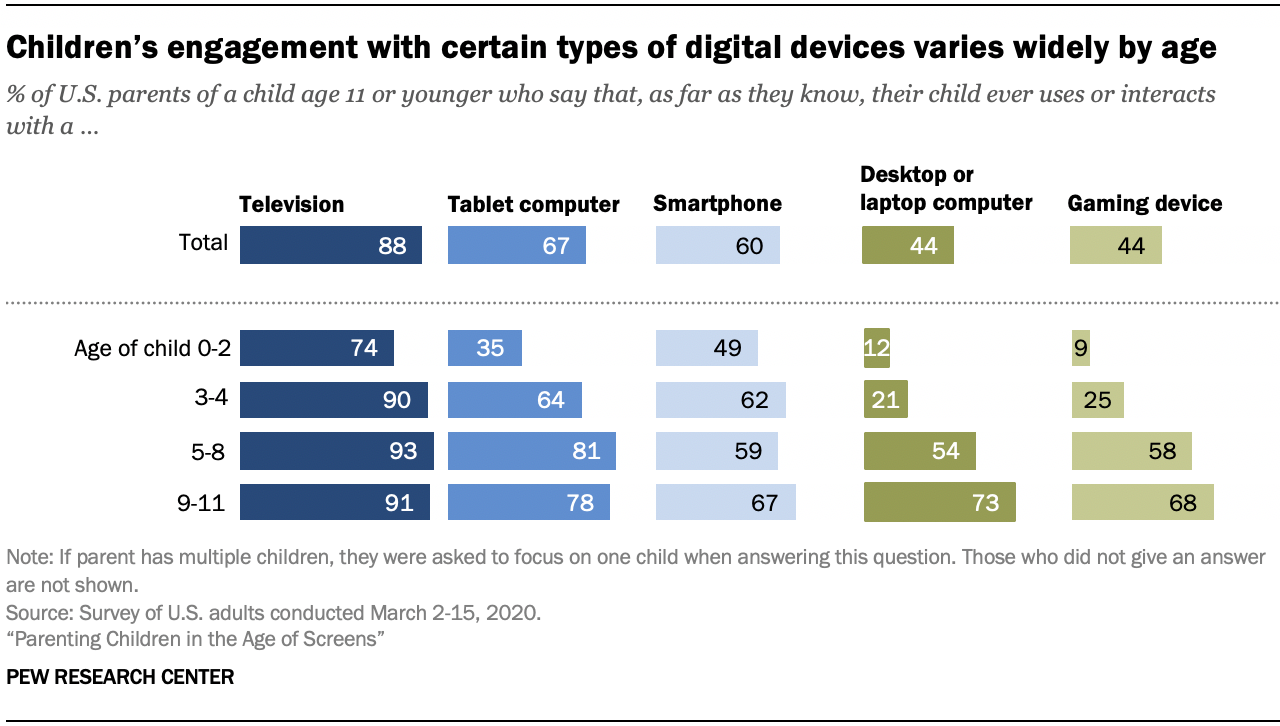

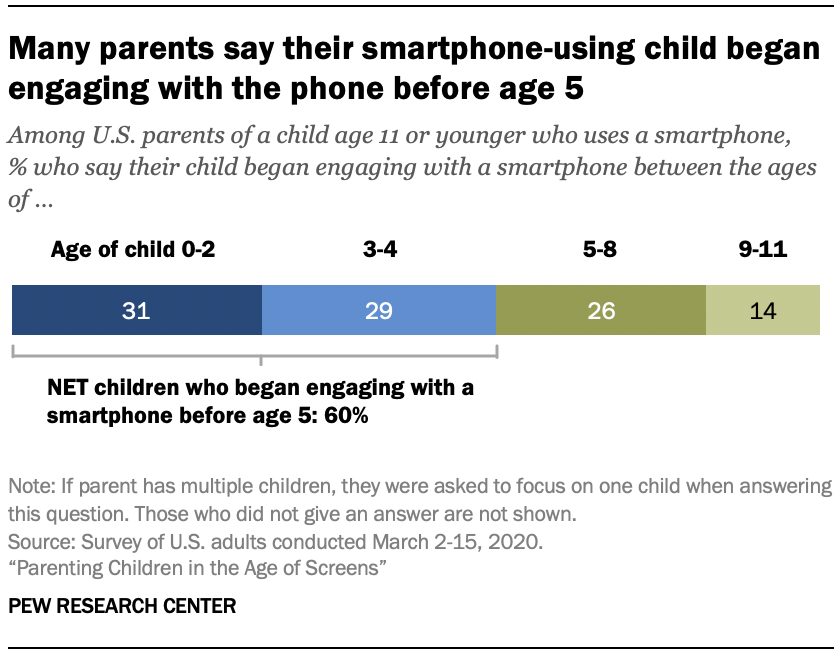

Today's children and teens are growing up immersed in digital media. It ranges from TV and videos to social media, video games and so much more. And it's all available on multiple devices—computers, e-readers, gaming consoles, smartphones and other screens.

Kids & media use: by the numbers

Recent Common Sense Media research shows that media use by tweens (ages 8–12 years) and teens (ages 13–18 years) rose faster in the two years since the COVID-19 pandemic than the four years before. The research found 8- to 12-year-olds spend an average of five and a half hours a day on screens and consuming media. That rate climbs to over eight and a half hours a day for teens.

Among teens, 79% said they use social media and online videos at least once a week, and 32% of these said they "wouldn't want to live without" YouTube. And nearly two-thirds (65%) of tweens said they watch TV, 64% watch online videos and 43% play games on a smartphone or tablet every day.

Average daily screentime rates soared highest among Black and Hispanic/Latino kids and those of lower-income families. These teens and tweens were spending between 6.5 and 7.5 hours a day on entertainment screens.

In another survey , 71% of parents with younger children (under 12 years old) said they were concerned about their child spending too much time in front of screens.

Risks & benefits of media use by children & teens

Why use digital media.

Digital media use can:

Expose users to new ideas and information.

Raise awareness of current events and issues.

Promote community participation.

Help students work with others on assignments and projects.

Digital media use also has social benefits that:

Allow families and friends to stay in touch, no matter where they live.

Enhance access to valuable support networks, especially for people with illnesses or disabilities.

Help promote wellness and healthy behaviors, such as how to quit smoking or how to eat healthy.

Why limit media use?

Overuse of digital media may place your children at risk of:

Not enough sleep. Media use can interfere with sleep. Children and teens who have too much media exposure or who have a TV, computer, or mobile device in their bedroom fall asleep later at night and sleep less. Even babies can be overstimulated by screens and miss the sleep they need to grow. Exposure to light (particularly blue light) and stimulating content from screens can delay or disrupt sleep and have a negative effect on school.

Obesity. Excessive screen use and having a TV in the bedroom can increase the risk of obesity . Watching TV for more than 1.5 hours daily is a risk factor for obesity for children 4 through 9 years of age. Teens who watch more than 5 hours of TV per day are 5 times more likely to have over-weight than teens who watch 0 to 2 hours. Food advertising and snacking while watching TV can promote obesity. Also, children who overuse media are less apt to be active with healthy, physical play.

Delays in learning & social skills. When infants or preschoolers watch too much TV, they may show delays in attention, thinking, language and social skills. One reason for this could be that they don't interact as much with their parents and family members. Parents who keep the TV on or spend excess time on their own digital media miss precious opportunities to interact with their children and help them learn.

Negative effect on school performance. Children and teens often use entertainment media at the same time that they're doing other things, such as homework . Such multitasking can have a negative effect on how well they do in school.

Behavior problems. Violent content on TV and screens can contribute to behavior problems in children, either because they are scared and confused by what they see or they try to mimic on-screen characters.

Problematic internet use. Children who spend too much time using online media can be at risk for a type of additive behavior called problematic internet use. Heavy video gamers are at risk for Internet gaming disorder. They spend most of their free time online and show less interest in offline or real-life relationships. There may be increased risks for depression at both the high and low ends of Internet use.

Risky behaviors. Teens' displays on social media often show risky behaviors, such as substance use, sexual behaviors, self-injury, or eating disorders. Exposure of teens through media to alcohol, tobacco use, or sexual behaviors is linked to engaging in these behaviors earlier.

Sexting, loss of privacy & predators. Sexting is the sending or receiving of sexually explicit images, videos, or text messages using a smartphone, computer, tablet, video game or digital camera. About 19% of youth have sent a sexual photo to someone else. Teens need to know that once content is shared with others, they may not be able to delete it completely. Kids may also not use privacy settings. Sex offenders may use social networking, chat rooms, e-mail and online games to contact and exploit children.

Cyberbullying. Children and teens online can be victims of cyberbullying. Cyberbullying can lead to short- and long-term negative social, academic, and health issues for both the bully and target. Fortunately, programs to help prevent bullying may reduce cyberbullying.

Make a family media use plan

Children today are growing up in a time of highly personalized media use experiences. It's smart to develop a customized media use plan for your children. This helps your kids avoid overusing media by balancing it with other healthy activities.

A media plan should consider each child's age, health, personality and developmental stage. Remember, all children and teens need adequate sleep (8–12 hours each night, depending on age), physical activity (1 hour a day) and time away from media. Create a customized plan for your family with our interactive Family Media Use Plan . Developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), this tool works with your family's values and busy life.

More information

- Beyond Screen Time: Help Your Kids Build Healthy Media Use Habits

- How to Make a Family Media Use Plan

- Virtual Violence: How Does It Affect Children?

- Cyberbullying: What Parents Need to Know

- Sexting: How To Talk With Kids About the Risks

- 5 Unhealthy Ways Digital Ads May Be Targeting Your Child

- Your Child's First Cell Phone: Are They Ready?

- Video Games: Establish Your Own Family's Rating System

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

28 The Influence of Television, Video Games, and the Internet on Children’s Creativity

Sandra L. Calvert, Children's Digital Media Center, Department of Psychology, Georgetown University

Patti M. Valkenburg, Amsterdam School of Communications Research, Center for Children, Adolescents, and the Media, University of Amsterdam

- Published: 01 August 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

For many children, substantial amounts of time are devoted almost every day to screen media, including television viewing, video game play, and online Internet activities. This chapter discusses exposure to these types of media activities and some of the ways they influence creativity. In particular, research investigating the extent to which different kinds of media activities might stimulate or, alternatively, have a negative reductive impact on, the development of creativity is reviewed. The evidence generally establishes a negative relationship between media use, particularly lean-back media such as television viewing, and creativity. An important positive exception is when children are exposed to educational television content that is designed to teach creativity through imaginative characters. Although many youth use newer media to view television content, children also lean forward and create content, such as online characters that engage in imaginative creative activities, such as role-playing.

For many children, development in the twenty-first century now takes place in the presence of a screen. Exposure remains primarily observational in nature, typically to television or video content that is presented via traditional broadcast venues, but also via newer options like Hulu that allow youth to view television programs online ( Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010 ). The ability to create content is also an important option of many newer media, such as blogs and social networking sites. How does the current media world, itself a symbolic construction and fabrication of reality, affect the development of children’s creativity? That question is the focus of this chapter.

We begin by defining creativity and the extent of children’s media exposure. Then we discuss alternative hypotheses concerning the relation between media exposure and children’s creativity and evaluate the research findings about the influences of television, video games, and the Internet. We end with a look to future research directions and our conclusions about what is currently known about the influence of media on children’s creativity.

What Is Creativity?

Creativity is a central facet of narrative thinking, which entails storylike, imaginistic thinking, whose object is not truth but “verisimilitude” or “lifelikeness” ( Bruner, 1986 , p. 11; Valkenburg & Peter, 2006 ). Narratives are a central form used in media, particularly television stories. According to Singer and Singer (2005) , the creative process involves the potential for imaginative novelty, in which there is a free flow of ideas, images, and mini stories, all facets of divergent processing, followed by an evaluation of the quality of these ideas within a domain of expertise (see chapter 24 ).

In the television literature, creativity can be defined as the capacity to generate many different novel or unusual ideas ( Valkenburg & van der Voort, 1994 ). Creativity is typically measured in television studies by divergent thinking tests, such as the number of novel responses an individual can generate to a problem, and by creative tasks like drawing, problem solving, and making up stories ( Valkenburg & van der Voort, 1994 ). Participation in extracurricular activities such as the visual arts, music, drama, and journalism, has also been defined as an indication of creativity ( D. R. Anderson, Huston, Schmitt, Linebarger, & Wright, 2001 ).

Although the research focus has often been on the effects of media on creativity after exposure, a neglected area of study involves an evaluation of the imaginative activities that take place during exposure ( Valkenburg & Peter, 2006 ). Expanding our knowledge of the role of imagination during media exposure may be particularly useful in understanding the role of newer technologies in creative processes because when children use interactive media, they have opportunities to create content rather than just consume the content of others.

Media Exposure and Experiences

From the cradle through the adolescent years, US children’s time is often spent in the presence of a screen. Using survey techniques, Common Sense Media (2011) and the Kaiser Family Foundation (2010) conducted nationally representative samples of US children and adolescents via online and telephone interviews, respectively. Two major reports were produced: one on media exposure during the first eight years of life, and the other on media exposure from ages 8 through 18.

The First eight Years

According to a recent Common Sense Media (2011) survey, young children’s lives are embedded in media. In a typical day for a US child under age eight, 69 percent will read or be read to, 75 percent will use some kind of screen media, and 51 percent will listen to music. Television remains the dominant force in children’s media use. Seventy percent of these children watch television on a typical day. Forty-two percent of children under age 8 have a television set in their bedroom, which allows them considerable autonomy in how much and what they decide to view.

The amount of time devoted to various media paints an even stronger picture of the role that audiovisual media play during the early years of life. Screen media 136 dominated young children’s time, with television and video use consuming 1 hour, 9 minutes on a typical day, followed by 25 minutes of media and video game play. Reading or being read to averaged 29 minutes per day, and listening to music consumed an average of 29 minutes per day. Thirty-nine percent of children lived in homes in which the television set was on all or most of the time.

The Common Sense Media (2011) report about early media exposure also found that the use of screen media increased with age. In the first year of life, screen use for all children averaged 53 minutes per day. By ages two to four, screen exposure time increased to two hours, 18 minutes daily, and increased to two hours, 50 minutes of exposure time for five- to eight-year-old children (Common Sense Media, 2011).

Middle Childhood and Adolescence

The Kaiser Family Foundation tracked the media use patterns of random samples of eight- to 18-year-old US children. Their findings revealed increase in exposure to digital media over time. In the latest survey of youth conducted by Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts (2010) , exposure to digital entertainment media averaged a staggering seven hours, 38 minutes per day, which increased to 10 hours, 45 minutes per day when multitasking (more than one medium being used at a time) was considered. These figures were significantly higher than the reported daily average of six hours, 21 minutes (eight hours, 33 minutes for total exposure with multitasking) from a comparable 2004 study ( Roberts, Rideout, & Foehr 2005 ), and from six hours, 19 minutes per day (seven hours, 29 minutes total exposure with multitasking) from 1999 ( Roberts, Foehr, Rideout, & Brodie, 1999 ). The explosion of cell phone and iPod/MP3 player use largely accounted for this increase in media use time. Leisure reading was the only area of decline.

The main kind of exposure that children select remains television content, which consumes four hours, 29 minutes of time on a typical day, up 38 minutes per day from 2004 figures. How that content is viewed, however, has shifted. In addition to television sets, youth view television programs and movies on the Internet, on their cell phones, and on their iPods ( Rideout et al., 2010 ). They also play video games on television sets, cell phones, and online. Thus, the delivery of media through a specific platform may now be a less useful concept for understanding media effects because youth can do just about any kind of activity on any electronic device that has a screen.

Media use by US children and adolescents is pervasive from the earliest days of life. Viewing television programs and videos dominate usage patterns, but adolescents also spend a considerable amount of time listening to music. Newer technologies like cell phones and iPods now make it possible for older youth to access many different kinds of content anytime, anywhere. Reading magazines and newspapers during leisure time has declined over time for preadolescents and adolescents.

Media Influences on Creativity: The Stimulation and Reduction Hypotheses

Two major hypotheses organize the literature on how media, which has mainly focused on the study of television, affects children’s creativity. One hypothesis argues for stimulation effects whereas the other argues for reduction effects ( Valkenburg & van der Voort, 1994 ). These hypotheses were based on children’s exposure to traditional “lean-back” audiovisual media, such as television and films. Given the current usage patterns and escalation of interactive computer media use ( Rideout et al., 2010 ), it would be interesting to investigate the fit of these hypotheses with children’s more recent “lean-forward” media experiences.

The Stimulation Hypothesis

The stimulation hypothesis argues that media provides children with content that they can then subsequently use in their creative activities, thereby enhancing their creative products ( Valkenburg, 1999 ). Presumably, exposure to imaginative content and social models that demonstrate imaginative behaviors has the potential to increase children’s creative behaviors. So can the way that the program is structured. For example, making games and other content with interactive media may also enhance children’s creativity.

Imaginative Content and Models of Imaginative Behavior

Several educational children’s television programs focus on creativity. The most studied program is Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood ( D. R. Anderson et al., 2001 ; Friedrich- Cofer, Huston-Stein, Kipnis, Susman, & Clewit, 1979 ; Singer & Singer, 1990 ), but other children’s educational television programs are also designed to cultivate divergent thinking. Many times these programs have a social model, such as Fred Rogers, who displays creative activities.

Social cognitive theory predicts that children who observe models engaging in behaviors, such as creative activities, are likely to learn that behavior and imitate it when it is appropriate for a specific situation ( Bandura, 1986 ). Imitation, though, is not necessarily an exact reproduction of a behavior. Rather, imitation can refer to an entire class of behaviors ( Bandura, 1986 ). In the case of creativity, televised models may provide children with a prototype for how to generate creative responses to situations. From this perspective, the kind of content viewed and the kind of relationship that children develop with imaginative characters should be key factors in determining subsequent activities. In particular, parasocial relationships, in which viewers develop a perceived relationship with a media character ( Hoffner, 2008 ), may be one reason that certain social models could enhance children’s creative activities.

Production and Production Techniques

To create, children need to be able to reflect ( Singer & Singer, 2005 ). Television programs that allow time for reflection, for instance, those that are slowly paced such as Mister Rogers Neighborhood , might be especially likely to elicit imaginative activities. In newer interactive media experiences, children can also create and be the characters that then appear and act onscreen ( Calvert, 2002 ).

Current production practices in children’s educational television programs also include the use of pauses built into the story at key program points ( D. R. Anderson et al., 2001 ). These pauses allow children time to respond to characters, thereby potentially promoting what is known as parasocial interaction , in which a child acts as if he or she is interacting with a media character ( Hoffner, 2008 ). More specifically, the character asks the child a question, the child presumably formulates a response, and the character then acts as if he or she hears or sees the child’s response ( Lauricella, Gola, & Calvert, 2011 ). Pauses also allow children time to think and reflect on content, a characteristic that could promote imaginative activity if an “interaction” occurs with an imaginative media character.

User-generated content is another potential way for creativity to be displayed. Youtube.com has a considerable amount of material that is produced by youth. Youth, for example, create videos about popular culture and post them on this site, and others come to see what has been created.

The Reduction Hypothesis

The reduction hypothesis involves five different reasons to explain why creativity might be disrupted by media exposure ( Valkenburg, 1999 ). All of these hypotheses suggest that there is something inherent in traditional media, such as television and films, which disrupts creativity ( D. R. Anderson et al., 2001 ).

The Displacement Hypothesis

According to the displacement hypothesis, children spend a considerable amount of time with media that displaces other activities, including creative ones. Television viewing, for instance, displaces reading, and reading is thought to enhance creative expression. Internet and video games now join the mix of media that may take time away from creative activities and leisure-time reading.

The Visualization Hypothesis