Journal of Family Business Management

Issue(s) available: 43 – From Volume: 1 Issue: 1 , to Volume: 14 Issue: 4

- Issue 4 2024

- Issue 3 2024

- Issue 2 2024

- Issue 1 2024

- Issue 4 2023

- Issue 3 2023

- Issue 2 2023

- Issue 1 2023 The Future of Family Business: marketing challenges in times of crisis

- Issue 4 2022

- Issue 3 2022 Family Business in Tourism and Hospitality

- Issue 2 2022

- Issue 1 2022

- Issue 4 2021

- Issue 3 2021 Enhancing policies and measurements of family business: Macro, meso or micro analysis

- Issue 2 2021

- Issue 1 2021

- Issue 4 2020 Cross-cultural and entrepreneurial strategies towards new family business performance: An Asian context

- Issue 3 2020

- Issue 2 2020

- Issue 1 2020

- Issue 4 2019

- Issue 3 2019

- Issue 2 2019

- Issue 1 2019 New Insights on SMEs: Finance and Family SMEs in a Changing Economic Landscape

- Issue 3 2018

- Issue 2 2018

- Issue 1 2018

- Issue 3 2017

- Issue 2 2017

- Issue 1 2017

- Issue 3 2016

- Issue 2 2016 Family business governance: role, relevance and impact

- Issue 1 2016

- Issue 2 2015

- Issue 1 2015

- Issue 2 2014

- Issue 1 2014

- Issue 2 2013

- Issue 1 2013 Taking a hard look at soft issues in family business

- Issue 2 2012

- Issue 1 2012

- Issue 2 2011

- Issue 1 2011

The role of in-laws in family business continuity: a perspective

The purpose is to provide a brief summary on the current research development regarding the role of in-laws in family firms’ continuity. Additionally, I provide a perspective on…

Managing a Gen-Z workforce – what family firms need to know: a perspectives article

This paper highlights the opportunities and challenges for family firms in managing Generation Z (Gen-Z) employees. This perspective article explores several considerations for…

Corporate entrepreneurship and family businesses: a perspective article

Family businesses play a pivotal role in the world’s economy, contributing to 70% of its GDP. Their success in the current environment demands the enactment of entrepreneurial and…

Psychological ownership in family firms: a perspective article

This article explores psychological ownership (PO) in family firms (FFs); its impact on interpersonal relationships, attitudes and behaviors within the organization; and its…

Internal communication and family business: a perspective article

Family businesses require internal communication (IC) to guide and provide direction, and the unique nature of involving both family and nonfamily employees add complexity…

Generation Alpha and family business: a perspective article

This paper discusses the key features of Generation Alpha from the perspective of their implications for future family business.

Money education in the business family: a perspective article

The primary aim is to renew academic discourse on financial education in business families. It emphasizes the need for effective financial literacy programs to foster a healthier…

Regional development and family business: a perspective article

This perspective article aims to summarise the understanding of the link between regional development and family business and explore potential pathways for further investigations.

Entrepreneurial resilience (ER) and family business: a perspective article

This paper highlights the need for future studies researching the subject of resilience in family firms on different levels.

AI-driven sustainability brand activism for family businesses: a future-proofing perspective article

Artificial intelligence (AI) and sustainable business represent the irrefutable future of all forward looking businesses in the world today. In this perspective article, the…

African family dynamics and family business – a perspective article

Despite the potential benefits of family businesses, their dynamics present peculiar challenges that hinder the realisation of their full potential. This paper sought to assess…

Analysis of trends that turn an entrepreneurship idea into a family business: an article in perspective

This article examines some of the trends that allow to understand and analyze the evolution of the idea of entrepreneurship to become a family business.

First (latent) generation and family business: a perspective article

Family businesses are characterized by the simultaneous presence of the family and the business system. The literature analyses sporadically the family support during the creation…

Key drivers of green innovation in family firms: a machine learning approach

This study aims to find the key drivers of green innovation in family firms by examining firm characteristics and geographical factors. It seeks to develop a conceptual framework…

From tradition to technological advancement: embracing blockchain technology in family businesses

Despite the rapid advancement of blockchain technology across various sectors, scholarly research on its application within family businesses remains significantly underdeveloped…

Job crafting and entrepreneurial innovativeness: the moderated mediation roles of dynamic capabilities and self-initiated AI learning

This paper investigates the moderated mediation roles of dynamic capabilities and self-initiated AI learning between job crafting and entrepreneurial innovativeness among…

Innovating with heart: family firms' decision to automate with emotional responsibility

The paper aims to explore how family involvement influences family firms (FF) decisions to innovate in automation (i.e. artificial intelligence, big data and robotics). Automation…

Women on board and financial distress: channeling effect of family firms

This study seeks to evaluate gender diversity within family members and analyze its effects on financial distress in firms listed in Vietnam.

Tacit knowledge sharing in a Lebanese family business: the influence of organizational structure and tie strength

This study explores the influence of organizational structure on relationship formation and tacit knowledge sharing within a family business context.

Female directors' representation and firm carbon emissions performance: does family control matter?

This study investigates whether female board representation reduces carbon emissions in French-listed companies. It also analyzes to what extent and in what direction family…

Exploratory analysis of the antecedents of failure in family businesses: cases from Catalunya

Family businesses (FBs) are considered an essential type of entrepreneurship that impacts economic growth. However, statistics show that after a period of performance they…

Family business culture: a strategic resource and driver of firm performance

Through a resource-based theoretical lens, we elucidate conditions under which family business culture (FBC) amplifies the positive effects of high-performance work systems (HPWS…

Organisational learning in family firms: a systematic review

Organisational learning (OL) is a critical capability family firms (FFs) need in order to adapt to an increasingly turbulent environment. Given the uniqueness of FFs and their…

Narratives of and for survival in family firms: family influence on narrative processing

Resilience of long-lived family businesses has been widely acknowledged but the mechanisms enabling longevity need to be further investigated. This can be done by examining how…

Artificial intelligence and family businesses: a systematic literature review

This paper examines the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) within family businesses, focusing on how AI can enhance their competitiveness, resilience and sustainability…

Understanding customer’s post-M&A intentions and behaviors: the role of the family business brand and previous reputation of the acquiring firm

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) are a critical time for organizations and their consumers. For the company, there are many financial and non-financial risks. For customers, it…

Attenuating workplace cynicism among non-family employees in family firms: influence of mindful leadership, belongingness and leader–member exchange quality

Drawing on mindfulness theory, this study attempts to gain insights into whether leader-mindfulness (LM) influences workplace cynicism (WPC) among non-family employees (NFEs…

Evolved leader behaviours for adopting lean and green in family firms: a longitudinal study in Indonesia

This longitudinal study focuses on the specific behaviours of both top and other leaders in family firms that are implementing lean and green practices in order to contribute to…

Beyond profit in family businesses: ESG-driven business model innovation and the critical role of digital capabilities

This study aims to analyze the interaction between environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices and digital capabilities in promoting business model innovation (BMI) in…

An investigation of the masculinity of entrepreneurial orientation in family business

Miller (2011) revisited his influential 1983 work on entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and remarked that its underlying drivers are fully open to debate, fresh scholarship and…

Fair play in family firms: examining the perceived justice of performance management systems

This study examines the intricate relationship between family influence and perceived justice in performance management systems within family firms. Recognizing the unique…

We don’t fire! Family firms and employment change during the COVID-19 pandemic

By investigating the reactions of family businesses to COVID-19 pandemic this article aims to explaining how family firms are capable to preserve employment during hardship.

A systematic literature review on home-based businesses: two decades of research

The research identifies literature on Home-Based Businesses (HBBs) from 2000 to August 2023, focuses on their economic roles, challenges for entrepreneurs and success strategies…

The perceived effect of digital transformation and resultant empowerment on job performance of employees in the fitness family business

The impact of technological transformations in all sectors is undeniably significant, especially in fitness family business. The aim is to examine the digital transformation…

Facilitating corporate sustainability integration: innovation in family firms

The purpose of the study is to understand the relationship between family-driven innovation and the incorporation of corporate sustainability in German family firms.

Uncovering the research trends of family-owned business succession: past, present and the future

The succession phenomenon in family-owned businesses (F-OB) determines their future viability and success. This study aims to provide insight into key research areas related to…

A decision-making framework in family-owned hotels for evaluating and selecting suppliers and strategic partners

This paper presents a comprehensive decision-making framework designed for family-owned hotels, specifically focusing on evaluating and selecting suppliers and strategic partners…

Directing the future: artificial intelligence integration in family businesses

This study explores the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) within family businesses. It seeks to understand how family-owned enterprises navigate the adoption of AI…

Family firms and the collaborative advantage: unveiling innovation efficiency across partnership types

Based on the resource orchestration perspective, this paper aims to examine whether family firms are more efficient in their collaboration for innovation process than non-family…

Family firms in government lobbies

Although the outcomes arising from firms’ interaction with policymakers is a developed theme, family firms’ political credentials and lobbying remain unexplored. To ignite this…

“All employees are equal … but some are more equal than others”. Role identity and nonfamily member discrimination in family SMEs

This paper aims to investigate if, under which conditions, and with which consequences, nonfamily members have the perception of being discriminated against as a consequence of…

Factors affecting succession planning in Sub-Saharan African family-owned businesses: a scoping review

This scoping review investigates the factors influencing succession planning in Sub-Saharan African family-owned businesses.

Exploring the uncharted influence of family social capital in entrepreneurial ecosystems

The purpose of this research is to develop theory, thereby attending to the existing knowledge gap regarding the impact of family firms on entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs)…

Balancing work and family when family is work: a reconceptualization of work–family integration, burnout and detachment in family business

Building from calls for greater interdisciplinary research in interpreting family business phenomena, we integrate research on work–family conflict, detachment and burnout from…

The African philosophy of Ubuntu and family businesses: a perspective article

This perspective article underscores the importance of conducting studies that examine the African philosophy of Ubuntu among indigenous African family businesses. The article…

Are family businesses more gender inclusive in leadership succession today? A perspective article

Through this exploration, this article seeks to contribute to facilitate a greater female participation in power and leadership positions in the context of succession by…

Dynamic capabilities and family businesses: a perspective article

The individual perspective of dynamic capabilities and family firms could be useful to shed light on the relationship between these topics, considering not only the heterogeneity…

Evaluation of the performance of Spanish family businesses portfolios

The primary objective of this study is to analyze the performance and risk characteristics of portfolios composed of Spanish family businesses (FBs) when sustainability and…

Sustainability performance disclosure and family businesses: a perspective article

The deeper understanding of the disclosure of external and internal dynamics of family firms necessarily places the issue of sustainability as one of the most pressing needs from…

Nurturing family business resilience through strategic supply chain management

The study aspires to enhance comprehension of the intricate interplay between supply chain management (SCM) and resilience in family businesses, thereby offering valuable insights…

Sustainability in family business settings: a strategic entrepreneurship perspective

Family business sustainability is a critical issue. This study considers if adopting a strategic entrepreneurship orientation can support the sustainability of a family business.

The influence of family firm CEOs’ transformational leadership on employee engagement: the mediating role of psychological safety

This study aims to unravel a potential determinant of employee engagement in family firms. In particular, we focus on the role of the CEO by studying the influence of CEO…

Entrepreneurial orientation and socioemotional wealth as enablers of the impact of digital transformation in family firms

The research aims to investigate how digital transformation (DT), entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and socioemotional wealth (SEW) impact the financial performance of family firms…

Relationship between the implementation of formal board processes and structures and financial performance: the role of absolute family control in Colombian family businesses

We investigate the effect of the adoption of formal board structure and board processes on firm performance in Colombian family firms, in a context where firms can choose specific…

Integrating UN Sustainable Development Goals into family business practices: a perspective article

This paper explores the potential for family businesses (FBs) to play a pivotal role in advancing the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It seeks to…

Intersecting bonds: a perspective on polygamy's influence in Arab Middle East family firm succession

The aim of this study is to explore and elucidate the influence of polygamy on the succession dynamics of family businesses in the Arab world, offering insights that may be…

Environmental responsibility of family businesses: a perspective paper

This perspective paper explores ongoing research into stimuli that promote environmental responsibility in family business contexts. It also delineates emerging patterns and…

Factors affecting high-quality entrepreneurial performance in small- and medium-sized family firms

The purpose of this paper is to measure the high-quality entrepreneurial efficiency of family-owned small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) while exploring the potential…

Exploring the effect of family control on debt financing within large firms: a transnational study in emerging markets

This paper aims to analyze the effect of family control and influence dimension of the socioemotional wealth (SEW) on capital structure of large listed firms in the North African…

Importance of traditions and family business at Christmas: a quantitative analysis of practices and values in Portugal

Christmas is the most consumed event of the year, always full of traditions, namely family ones, which are very significant. In this way, it is intended to find out the importance…

Intra-family communication in challenging times and family business: a perspective article

This perspective article highlights the importance of future research that explores how intra-family communication in family businesses was affected during challenging times such…

Navigating the path of family business research: a personal reflection

This article provides a personal response to the questions raised by Ratten et al . (2023) on what family business researchers have learnt about the family business field and tips…

European family business owners: what factors affect their job satisfaction?

This research aims to better understand the factors and determinants that shape the job satisfaction of European family business owners.

Financial management and family business: a perspective article

This study aims to review major themes and findings of research into financial management of family business and to suggest new directions for future research.

Conceptualizing recourses as antecedents to the economic performance of family-based microenterprise – the moderating role of competencies

The development of family-based microenterprises has attracted the attention of regulators, microfinance institutions and other stakeholders in either developing or least…

The adoption of governance mechanisms in family businesses: an institutional lens

Despite agreement on the importance of adopting governance structures for developing competitive advantage, we still know little about why or how governance mechanisms are adopted…

Migrant family entrepreneurship – mixed and multiple embeddedness of transgenerational Turkish family entrepreneurs in Berlin

By combining manifold approaches from migrant entrepreneurship and family business studies, the purpose of the paper is to shed some light upon the contextual features of…

Encouraging consumer loyalty: the role of family business in hospitality

The aim of this paper is to understand the importance of consumer loyalty in the specific context of Hotel Family Business. This study proposes a conceptual model to examine how…

No hard feelings? Non-succeeding siblings and their perceptions of justice in family firms

Family farms, in which business and family life are intricately interwoven, offer an interesting context for better understanding the interdependence between the family and…

Next-generation leadership development: a management succession perspective

This research study focusses on the succession challenges in small-medium outboard marine businesses of Malaysian Chinese family ownership. The founder-owners face challenges in…

Promoting family business in handicrafts through local tradition and culture: an innovative approach

The purpose of the study is to investigate the potentiality and dimensions of promoting handicraft family business practices in handicraft as well as the extent to highlight the…

Family entrepreneurial resilience – an intergenerational learning approach

The purpose of this paper is to explore leadership succession in families in business. Although there is a vast amount of research on leadership succession, no attempt has been…

Embeddedness and entrepreneurial traditions: Entrepreneurship of Bukharian Jews in diaspora

The purpose of this paper is to explore how entrepreneurship traditions evolve in diaspora.

Family equity as a transgenerational mechanism for entrepreneurial families

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the process of family equity creation and its role for transgenerational entrepreneurship.

Retaining the adolescent workforce in family businesses

The purpose of this study is to critically explore the linkage between adolescent work, parent–child relationships and offspring career choice outcomes in a family business…

Online date, start – end:

Copyright holder:, open access:.

- Associate Professor Vanessa Ratten

Further Information

- About the journal (opens new window)

- Purchase information (opens new window)

- Editorial team (opens new window)

- Write for this journal (opens new window)

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

Journal of Family Business Management

- Submit your paper

- Author guidelines

- Editorial team

- Indexing & metrics

- Calls for papers & news

Before you start

For queries relating to the status of your paper pre-decision, please contact the Editor or Journal Editorial Office. For queries post-acceptance, please contact the Supplier Project Manager. These details can be found in the Editorial Team section.

Author responsibilities

Our goal is to provide you with a professional and courteous experience at each stage of the review and publication process. There are also some responsibilities that sit with you as the author. Our expectation is that you will:

- Respond swiftly to any queries during the publication process.

- Be accountable for all aspects of your work. This includes investigating and resolving any questions about accuracy or research integrity

- Treat communications between you and the journal editor as confidential until an editorial decision has been made.

- Include anyone who has made a substantial and meaningful contribution to the submission (anyone else involved in the paper should be listed in the acknowledgements).

- Exclude anyone who hasn’t contributed to the paper, or who has chosen not to be associated with the research.

- In accordance with COPE’s position statement on AI tools , Large Language Models cannot be credited with authorship as they are incapable of conceptualising a research design without human direction and cannot be accountable for the integrity, originality, and validity of the published work.

- If your article involves human participants, you must ensure you have considered whether or not you require ethical approval for your research, and include this information as part of your submission. Find out more about informed consent .

Research and publishing ethics

Our editors and employees work hard to ensure the content we publish is ethically sound. To help us achieve that goal, we closely follow the advice laid out in the guidelines and flowcharts on the COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) website .

We have also developed our research and publishing ethics guidelines . If you haven’t already read these, we urge you to do so – they will help you avoid the most common publishing ethics issues.

A few key points:

- Any manuscript you submit to this journal should be original. That means it should not have been published before in its current, or similar, form. Exceptions to this rule are outlined in our pre-print and conference paper policies . If any substantial element of your paper has been previously published, you need to declare this to the journal editor upon submission. Please note, the journal editor may use Crossref Similarity Check to check on the originality of submissions received. This service compares submissions against a database of 49 million works from 800 scholarly publishers.

- Your work should not have been submitted elsewhere and should not be under consideration by any other publication.

- If you have a conflict of interest, you must declare it upon submission; this allows the editor to decide how they would like to proceed. Read about conflict of interest in our research and publishing ethics guidelines .

- By submitting your work to Emerald, you are guaranteeing that the work is not in infringement of any existing copyright.

Third party copyright permissions

Prior to article submission, you need to ensure you’ve applied for, and received, written permission to use any material in your manuscript that has been created by a third party. Please note, we are unable to publish any article that still has permissions pending. The rights we require are:

- Non-exclusive rights to reproduce the material in the article or book chapter.

- Print and electronic rights.

- Worldwide English-language rights.

- To use the material for the life of the work. That means there should be no time restrictions on its re-use e.g. a one-year licence.

We are a member of the International Association of Scientific, Technical, and Medical Publishers (STM) and participate in the STM permissions guidelines , a reciprocal free exchange of material with other STM publishers. In some cases, this may mean that you don’t need permission to re-use content. If so, please highlight this at the submission stage.

Please take a few moments to read our guide to publishing permissions to ensure you have met all the requirements, so that we can process your submission without delay.

Open access submissions and information

All our journals currently offer two open access (OA) publishing paths; gold open access and green open access.

If you would like to, or are required to, make the branded publisher PDF (also known as the version of record) freely available immediately upon publication, you can select the gold open access route once your paper is accepted.

If you’ve chosen to publish gold open access, this is the point you will be asked to pay the APC (article processing charge) . This varies per journal and can be found on our APC price list or on the editorial system at the point of submission. Your article will be published with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 user licence , which outlines how readers can reuse your work.

Alternatively, if you would like to, or are required to, publish open access but your funding doesn’t cover the cost of the APC, you can choose the green open access, or self-archiving, route. As soon as your article is published, you can make the author accepted manuscript (the version accepted for publication) openly available, free from payment and embargo periods.

You can find out more about our open access routes, our APCs and waivers and read our FAQs on our open research page.

Find out about open

Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines

We are a signatory of the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines , a framework that supports the reproducibility of research through the adoption of transparent research practices. That means we encourage you to:

- Cite and fully reference all data, program code, and other methods in your article.

- Include persistent identifiers, such as a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), in references for datasets and program codes. Persistent identifiers ensure future access to unique published digital objects, such as a piece of text or datasets. Persistent identifiers are assigned to datasets by digital archives, such as institutional repositories and partners in the Data Preservation Alliance for the Social Sciences (Data-PASS).

- Follow appropriate international and national procedures with respect to data protection, rights to privacy and other ethical considerations, whenever you cite data. For further guidance please refer to our research and publishing ethics guidelines . For an example on how to cite datasets, please refer to the references section below.

Prepare your submission

Manuscript support services.

We are pleased to partner with Editage, a platform that connects you with relevant experts in language support, translation, editing, visuals, consulting, and more. After you’ve agreed a fee, they will work with you to enhance your manuscript and get it submission-ready.

This is an optional service for authors who feel they need a little extra support. It does not guarantee your work will be accepted for review or publication.

Visit Editage

Manuscript requirements

Before you submit your manuscript, it’s important you read and follow the guidelines below. You will also find some useful tips in our structure your journal submission how-to guide.

|

| Article files should be provided in Microsoft Word format While you are welcome to submit a PDF of the document alongside the Word file, PDFs alone are not acceptable. LaTeX files can also be used but only if an accompanying PDF document is provided. Acceptable figure file types are listed further below. |

|

| Articles should be between 7500 and 8500 words in length. This includes all text, for example, the structured abstract, references, all text in tables, and figures and appendices. Please allow 280 words for each figure or table. |

|

| A concisely worded title should be provided. |

|

| The names of all contributing authors should be added to the ScholarOne submission; please list them in the order in which you’d like them to be published. Each contributing author will need their own ScholarOne author account, from which we will extract the following details: (institutional preferred). . We will reproduce it exactly, so any middle names and/or initials they want featured must be included. . This should be where they were based when the research for the paper was conducted.In multi-authored papers, it’s important that ALL authors that have made a significant contribution to the paper are listed. Those who have provided support but have not contributed to the research should be featured in an acknowledgements section. You should never include people who have not contributed to the paper or who don’t want to be associated with the research. Read about our for authorship. |

|

| If you want to include these items, save them in a separate Microsoft Word document and upload the file with your submission. Where they are included, a brief professional biography of not more than 100 words should be supplied for each named author. |

|

| Your article must reference all sources of external research funding in the acknowledgements section. You should describe the role of the funder or financial sponsor in the entire research process, from study design to submission. |

|

| All submissions must include a structured abstract, following the format outlined below. These four sub-headings and their accompanying explanations must always be included: The following three sub-headings are optional and can be included, if applicable:

The maximum length of your abstract should be 250 words in total, including keywords and article classification (see the sections below). |

|

| Your submission should include up to 12 appropriate and short keywords that capture the principal topics of the paper. Our how to guide contains some practical guidance on choosing search-engine friendly keywords. Please note, while we will always try to use the keywords you’ve suggested, the in-house editorial team may replace some of them with matching terms to ensure consistency across publications and improve your article’s visibility. |

|

| During the submission process, you will be asked to select a type for your paper; the options are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit: You will also be asked to select a category for your paper. The options for this are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit: Reports on any type of research undertaken by the author(s), including: Covers any paper where content is dependent on the author's opinion and interpretation. This includes journalistic and magazine-style pieces. Describes and evaluates technical products, processes or services. Focuses on developing hypotheses and is usually discursive. Covers philosophical discussions and comparative studies of other authors’ work and thinking. Describes actual interventions or experiences within organizations. It can be subjective and doesn’t generally report on research. Also covers a description of a legal case or a hypothetical case study used as a teaching exercise. |

|

| Headings must be concise, with a clear indication of the required hierarchy. |

|

| Notes or endnotes should only be used if absolutely necessary. They should be identified in the text by consecutive numbers enclosed in square brackets. These numbers should then be listed, and explained, at the end of the article. |

|

| All figures (charts, diagrams, line drawings, webpages/screenshots, and photographic images) should be submitted electronically. Both colour and black and white files are accepted. |

|

| Tables should be typed and submitted in a separate file to the main body of the article. The position of each table should be clearly labelled in the main body of the article with corresponding labels clearly shown in the table file. Tables should be numbered consecutively in Roman numerals (e.g. I, II, etc.). Give each table a brief title. Ensure that any superscripts or asterisks are shown next to the relevant items and have explanations displayed as footnotes to the table, figure or plate. |

|

| Where tables, figures, appendices, and other additional content are supplementary to the article but not critical to the reader’s understanding of it, you can choose to host these supplementary files alongside your article on Insight, Emerald’s content hosting platform, or on an institutional or personal repository. All supplementary material must be submitted prior to acceptance. , you must submit these as separate files alongside your article. Files should be clearly labelled in such a way that makes it clear they are supplementary; Emerald recommends that the file name is descriptive and that it follows the format ‘Supplementary_material_appendix_1’ or ‘Supplementary tables’. . A link to the supplementary material will be added to the article during production, and the material will be made available alongside the main text of the article at the point of EarlyCite publication. Please note that Emerald will not make any changes to the material; it will not be copyedited, typeset, and authors will not receive proofs. Emerald therefore strongly recommends that you style all supplementary material ahead of acceptance of the article. Emerald Insight can host the following file types and extensions: , you should ensure that the supplementary material is hosted on the repository ahead of submission, and then include a link only to the repository within the article. It is the responsibility of the submitting author to ensure that the material is free to access and that it remains permanently available. Please note that extensive supplementary material may be subject to peer review; this is at the discretion of the journal Editor and dependent on the content of the material (for example, whether including it would support the reviewer making a decision on the article during the peer review process). |

|

| All references in your manuscript must be formatted using one of the recognised Harvard styles. You are welcome to use the Harvard style Emerald has adopted – we’ve provided a detailed guide below. Want to use a different Harvard style? That’s fine, our typesetters will make any necessary changes to your manuscript if it is accepted. Please ensure you check all your citations for completeness, accuracy and consistency.

References to other publications in your text should be written as follows: , 2006) Please note, ‘ ' should always be written in italics.A few other style points. These apply to both the main body of text and your final list of references. At the end of your paper, please supply a reference list in alphabetical order using the style guidelines below. Where a DOI is available, this should be included at the end of the reference. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), , publisher, place of publication. e.g. Harrow, R. (2005), , Simon & Schuster, New York, NY. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "chapter title", editor's surname, initials (Ed.), , publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. Calabrese, F.A. (2005), "The early pathways: theory to practice – a continuum", Stankosky, M. (Ed.), , Elsevier, New York, NY, pp.15-20. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of article", , volume issue, page numbers. e.g. Capizzi, M.T. and Ferguson, R. (2005), "Loyalty trends for the twenty-first century", , Vol. 22 No. 2, pp.72-80. |

|

| Surname, initials (year of publication), "title of paper", in editor’s surname, initials (Ed.), , publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. Wilde, S. and Cox, C. (2008), “Principal factors contributing to the competitiveness of tourism destinations at varying stages of development”, in Richardson, S., Fredline, L., Patiar A., & Ternel, M. (Ed.s), , Griffith University, Gold Coast, Qld, pp.115-118. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of paper", paper presented at [name of conference], [date of conference], [place of conference], available at: URL if freely available on the internet (accessed date). e.g. Aumueller, D. (2005), "Semantic authoring and retrieval within a wiki", paper presented at the European Semantic Web Conference (ESWC), 29 May-1 June, Heraklion, Crete, available at: ;(accessed 20 February 2007). |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of article", working paper [number if available], institution or organization, place of organization, date. e.g. Moizer, P. (2003), "How published academic research can inform policy decisions: the case of mandatory rotation of audit appointments", working paper, Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds, Leeds, 28 March. |

|

| (year), "title of entry", volume, edition, title of encyclopaedia, publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. (1926), "Psychology of culture contact", Vol. 1, 13th ed., Encyclopaedia Britannica, London and New York, NY, pp.765-771. (for authored entries, please refer to book chapter guidelines above) |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "article title", , date, page numbers. e.g. Smith, A. (2008), "Money for old rope", , 21 January, pp.1, 3-4. |

|

| (year), "article title", date, page numbers. e.g. (2008), "Small change", 2 February, p.7. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of document", unpublished manuscript, collection name, inventory record, name of archive, location of archive. e.g. Litman, S. (1902), "Mechanism & Technique of Commerce", unpublished manuscript, Simon Litman Papers, Record series 9/5/29 Box 3, University of Illinois Archives, Urbana-Champaign, IL. |

|

| If available online, the full URL should be supplied at the end of the reference, as well as the date that the resource was accessed. Surname, initials (year), “title of electronic source”, available at: persistent URL (accessed date month year). e.g. Weida, S. and Stolley, K. (2013), “Developing strong thesis statements”, available at: (accessed 20 June 2018) Standalone URLs, i.e. those without an author or date, should be included either inside parentheses within the main text, or preferably set as a note (Roman numeral within square brackets within text followed by the full URL address at the end of the paper). |

|

| Surname, initials (year), , name of data repository, available at: persistent URL, (accessed date month year). e.g. Campbell, A. and Kahn, R.L. (2015), , ICPSR07218-v4, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (distributor), Ann Arbor, MI, available at: (accessed 20 June 2018) |

Submit your manuscript

There are a number of key steps you should follow to ensure a smooth and trouble-free submission.

Double check your manuscript

Before submitting your work, it is your responsibility to check that the manuscript is complete, grammatically correct, and without spelling or typographical errors. A few other important points:

- Give the journal aims and scope a final read. Is your manuscript definitely a good fit? If it isn’t, the editor may decline it without peer review.

- Does your manuscript comply with our research and publishing ethics guidelines ?

- Have you cleared any necessary publishing permissions ?

- Have you followed all the formatting requirements laid out in these author guidelines?

- If you need to refer to your own work, use wording such as ‘previous research has demonstrated’ not ‘our previous research has demonstrated’.

- If you need to refer to your own, currently unpublished work, don’t include this work in the reference list.

- Any acknowledgments or author biographies should be uploaded as separate files.

- Carry out a final check to ensure that no author names appear anywhere in the manuscript. This includes in figures or captions.

You will find a helpful submission checklist on the website Think.Check.Submit .

The submission process

All manuscripts should be submitted through our editorial system by the corresponding author.

The only way to submit to the journal is through the journal’s ScholarOne site as accessed via the Emerald website, and not by email or through any third-party agent/company, journal representative, or website. Submissions should be done directly by the author(s) through the ScholarOne site and not via a third-party proxy on their behalf.

A separate author account is required for each journal you submit to. If this is your first time submitting to this journal, please choose the Create an account or Register now option in the editorial system. If you already have an Emerald login, you are welcome to reuse the existing username and password here.

Please note, the next time you log into the system, you will be asked for your username. This will be the email address you entered when you set up your account.

Don't forget to add your ORCiD ID during the submission process. It will be embedded in your published article, along with a link to the ORCiD registry allowing others to easily match you with your work.

Don’t have one yet? It only takes a few moments to register for a free ORCiD identifier .

Visit the ScholarOne support centre for further help and guidance.

What you can expect next

You will receive an automated email from the journal editor, confirming your successful submission. It will provide you with a manuscript number, which will be used in all future correspondence about your submission. If you have any reason to suspect the confirmation email you receive might be fraudulent, please contact our Rights team on [email protected]

Post submission

Review and decision process.

Each submission is checked by the editor. At this stage, they may choose to decline or unsubmit your manuscript if it doesn’t fit the journal aims and scope, or they feel the language/manuscript quality is too low.

If they think it might be suitable for the publication, they will send it to at least two independent referees for double anonymous peer review. Once these reviewers have provided their feedback, the editor may decide to accept your manuscript, request minor or major revisions, or decline your work.

While all journals work to different timescales, the goal is that the editor will inform you of their first decision within 60 days.

During this period, we will send you automated updates on the progress of your manuscript via our submission system, or you can log in to check on the current status of your paper. Each time we contact you, we will quote the manuscript number you were given at the point of submission. If you receive an email that does not match these criteria, it could be fraudulent and we recommend you email [email protected] .

If your submission is accepted

Open access.

Once your paper is accepted, you will have the opportunity to indicate whether you would like to publish your paper via the gold open access route.

If you’ve chosen to publish gold open access, this is the point you will be asked to pay the APC (article processing charge). This varies per journal and can be found on our APC price list or on the editorial system at the point of submission. Your article will be published with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 user licence , which outlines how readers can reuse your work.

All accepted authors are sent an email with a link to a licence form. This should be checked for accuracy, for example whether contact and affiliation details are up to date and your name is spelled correctly, and then returned to us electronically. If there is a reason why you can’t assign copyright to us, you should discuss this with your journal content editor. You will find their contact details on the editorial team section above.

Proofing and typesetting

Once we have received your completed licence form, the article will pass directly into the production process. We will carry out editorial checks, copyediting, and typesetting and then return proofs to you (if you are the corresponding author) for your review. This is your opportunity to correct any typographical errors, grammatical errors or incorrect author details. We can’t accept requests to rewrite texts at this stage.

When the page proofs are finalised, the fully typeset and proofed version of record is published online. This is referred to as the EarlyCite version. While an EarlyCite article has yet to be assigned to a volume or issue, it does have a digital object identifier (DOI) and is fully citable. It will be compiled into an issue according to the journal’s issue schedule, with papers being added by chronological date of publication.

How to share your paper

Visit our author rights page to find out how you can reuse and share your work.

To find tips on increasing the visibility of your published paper, read about how to promote your work .

Correcting inaccuracies in your published paper

Sometimes errors are made during the research, writing and publishing processes. When these issues arise, we have the option of withdrawing the paper or introducing a correction notice. Find out more about our article withdrawal and correction policies .

Need to make a change to the author list? See our frequently asked questions (FAQs) below.

Frequently asked questions

The only time we will ever ask you for money to publish in an Emerald journal is if you have chosen to publish via the gold open access route. You will be asked to pay an APC (article-processing charge) once your paper has been accepted (unless it is a sponsored open access journal), and never at submission.

Read about our APCs

At no other time will you be asked to contribute financially towards your article’s publication, processing, or review. If you haven’t chosen gold open access and you receive an email that appears to be from Emerald, the journal, or a third party, asking you for payment to publish, please contact our support team via [email protected] .

- Associate Professor Vanessa Ratten La Trobe University - Australia [email protected]

Associate Editor

- Professor Beatriz Casais Universidade do Minho - Portugal

- Jerónimo García-Fernández Universidad de Sevilla - Spain

- Dr Konstantinos Koronios University of Peloponnese - Greece

- Professor João Leitão Universidade da Beira Interior - Portugal

- Joseph Johnson Emerald Publishing - UK [email protected]

Journal Editorial Office (For queries related to pre-acceptance)

- Sonal Aherkar Emerald Publishing [email protected]

Supplier Project Manager (For queries related to post-acceptance)

- Preethi Vittal Emerald Publishing [email protected]

Editorial Advisory Board

- Jannett Ayup González Universidad Autònoma de Tamaulipas - Mexico

- Sergio Barile University of Rome “'La Sapienza” - Italy

- Robin Bell University of Worcester - UK

- Zografia Bika University of East Anglia - UK

- Isabel C. Botero University of Louisville - USA

- Richard Boyatzis Case Western Reserve University - USA

- Andrea Calabro IPAG Business School - France

- Mark Anthony Camilleri University of Malta, Msida, Malta

- Anna Carmon Indiana University-Purdue University - USA

- Francesca M. Cesaroni University of Urbino Carlo Bo - Italy

- Ranjan Chaudhuri Indian Institute of Management Ranchi - India

- Jim Chrisman Mississippi State University - USA

- Andrea Colli Università Bocconi - Italy

- Joshua J. Daspit McCoy College of Business, Texas State University - USA

- Josiane Fahed-Sreih Institute of Family and Entrepreneurial Business, Lebanese American University - Lebanon

- Shelley Farrington Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University - South Africa

- Birgit Feldbauer-Durstmüller Johannes Kepler University Linz - Austria

- Feranita Feranita Taylor's University - Malaysia

- Laura Galloway University of Edinburgh - UK

- Martin Hiebl Johannes Kepler University Linz - Austria

- Paul Jones Swansea University

- Andreas Kallmuenzer Excelia Business School - France

- Giacomo Laffranchini University of La Verne - USA

- Sankaran Manikutty Indian Institute of Management - India

- Laura E. Marler Mississippi State University - USA

- Nasina Mat Desa Universiti Sains Malaysia - Malaysia

- Stefan Mayr Johannes Kepler Univerity on Linz - Austria

- Mike Mustafa University of Nottingham - UK

- Atanas Nik Nikolov Kennesaw State University - USA

- Rosmini Omar Universiti Teknologi Malaysia - Malaysia

- Johann Packendorff KTH - Royal Institute of Technology - Sweden

- Mauricio Silva Glasgow Caledonian University - UK

- Gregorio Sánchez Marin University of Murcia - Spain

- Syed Awais Tipu University of Sharjah - United Arab Emirates

- Georgios Tsekouropoulos International Hellenic University - Greece

- Natalia Vershinina Audencia Business School, Audencia Nantes School of Management - France

- Demetris Vrontis University of Nicosia - Cyprus

- Yong Wang University of Wolverhampton - UK

- Jie (Jay) Yang University of Texas at Tyler - USA

- María Isabel de la Garza Ramos Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas - Mexico

Editorial Review Board

- George Acheampong University of Ghana - Ghana

- Naveed Akhter Jönköping International Business School - Sweden

- Mahmaod Al-Rawad King Faisal University - Saudi Arabia

- Abeer Alkhwaldi Mutah University - Jordan

- Afsaneh Bagheri University of Lincoln - UK

- Kanupriya Bakhru Jaypee Institute of Information Technology - India

- Jesús Barrena-Martínez Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at the University of Cádiz (Spain) - Spain

- Gül Erkol Bayram Sinop University - Turkey

- Börje Boers University of Skövde - Sweden

- Rayenda Khresna Brahmana Coventry University - UK

- Meghna Chhabra Delhi School of Business, New Delhi - India

- James M. Crick University of Leicester - UK; University of Ottawa - Canada

- Cinzia Dessì University of Cagliari - Italy

- Allan Discua Cruz Lancaster University Management School - UK

- Islam El Bayoumi Salem Alexandria University - Egypt; University of Technology and Applied Sciences - Oman

- Mariana Estrada-Robles University of Leeds - UK

- Esther Ferrnadiz Universidad de Cadiz - Spain

- Daniel Gandrita Universidade Europeia - Portugal

- Rafaela Gjergji Liuc University - Italy

- Raith Hendayani Telkom University - Indonesia

- Eglantina Hysa Epoka University - Albania

- Ermira Hoxha Kalaj Luigj Gurakuqi University - Albania

- Eijaz Khan James Cook University - Australia

- Mohammad Saud Khan School of Management, Victoria Business School (Department of Innovation Management and Entrepreneurship) - New Zealand

- Naveed R. Khan UCSI University - Malaysia

- Abdalwali Lutfi Khassawneh King Faisal University (KFU)-Al-Ahsa - Saudi Arabia

- Taewoo Kim University of Louisiana at Monroe - USA

- Emil Knezović International University of Sarajevo - Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Deepak Kumar La Trobe University - Australia

- Michael Kuttner Salzburg University of Applied Sciences - Austria

- Stella Lippolis University of Bari 'Aldo Moro' - Italy

- Farwis Mahrool South Eastern University of Sri Lanka - Sri Lanka

- Lucija Mihotić Vienna University of Economics and Business - Austria

- Marija Mosurović Institute of Economic Sciences - Serbia

- Anna Motylska-Kuzma DSW University of Lower Silesia - Poland

- Mohamed Mousa Pontifical Catholic University of Peru - Peru

- Hafiz Muhammad Muien Universiti Utara Malaysia - Malaysia

- Poh Yen Ng Robert Gorden University - UK

- Cuong Nguyen Industrial University of Ho Chi Minh City - Vietnam

- Ninh Nguyen Charles Darwin University - Australia

- Sérgio Nunes Polytechnic of Tomar - Portugal

- Nora Obermayer University of Pannonia - Hungary

- Parth Patel Australian Institute of Business - Australia

- Ivan Paunovic Bonn-Rhine-Sieg University of Applied Sciences - Germany

- Efstathios Polyzos Zayed University - United Arab Emirates

- Ahmad Rafiki Universitas Medan Area - Indonesia

- Kathleen Randerson Audencia University - France

- Aidin Salamzadeh University of Tehran (Iran)

- Yashar Salamzadeh University of Sunderland - UK

- Annalisa Sentuti University of Urbino - Italy

- Emilee L Simmons Leeds Trinity University - UK

- Mohammad Soliman UTAS - Oman

- Izabella Steinerowska-Streb University of Economics in Katowice - Poland

- Paul Strickland La Trobe University - Australia

- Mehdi Tajpour University of Tehran - Iran

- Sanjay Taneja Chandigarh University - India

- Wendy Teoh Ming Yen Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melak - Malaysia

- Anisha Thomas Kuwait College of Science and Technology - Kuwait

- Victor Tiberius University of Potsdam - Germany

- Asdren Toska SouthEast European University - Macedonia

- Tan Vo-Thanh Excelia Business School - France

- Jake Waddingham Texas State University - USA

- Umair Waqas University of Buraimi - Omar

- Anna Zamojska University of Gdansk - Poland

- Anita Zehrer Management Center Innsbruck - Austria

Citation metrics

CiteScore 2023

Further information

CiteScore is a simple way of measuring the citation impact of sources, such as journals.

Calculating the CiteScore is based on the number of citations to documents (articles, reviews, conference papers, book chapters, and data papers) by a journal over four years, divided by the number of the same document types indexed in Scopus and published in those same four years.

For more information and methodology visit the Scopus definition

CiteScore Tracker 2024

(updated monthly)

CiteScore Tracker is calculated in the same way as CiteScore, but for the current year rather than previous, complete years.

The CiteScore Tracker calculation is updated every month, as a current indication of a title's performance.

2023 Impact Factor

The Journal Impact Factor is published each year by Clarivate Analytics. It is a measure of the number of times an average paper in a particular journal is cited during the preceding two years.

For more information and methodology see Clarivate Analytics

5-year Impact Factor (2023)

A base of five years may be more appropriate for journals in certain fields because the body of citations may not be large enough to make reasonable comparisons, or it may take longer than two years to publish and distribute leading to a longer period before others cite the work.

Actual value is intentionally only displayed for the most recent year. Earlier values are available in the Journal Citation Reports from Clarivate Analytics .

Publication timeline

Time to first decision

Time to first decision , expressed in days, the "first decision" occurs when the journal’s editorial team reviews the peer reviewers’ comments and recommendations. Based on this feedback, they decide whether to accept, reject, or request revisions for the manuscript.

Data is taken from submissions between 1st June 2023 and 31st May 2024

Acceptance to publication

Acceptance to publication , expressed in days, is the average time between when the journal’s editorial team decide whether to accept, reject, or request revisions for the manuscript and the date of publication in the journal.

Data is taken from the previous 12 months (Last updated July 2024)

Acceptance rate

The acceptance rate is a measurement of how many manuscripts a journal accepts for publication compared to the total number of manuscripts submitted expressed as a percentage %

Data is taken from submissions between 1st June 2023 and 31st May 2024 .

This figure is the total amount of downloads for all articles published early cite in the last 12 months

(Last updated: July 2024)

This journal is abstracted and indexed by

- British Library

- Cabell's Directory of Publishing Opportunities in Management

- ReadCube Discover

This journal is ranked by

- Thomson Reuters Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI)

- VHB-JOURQUAL 3 (Germany)

- AIDEA (Italy)

- Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS UK)

- VHB Publication Media Rating 2024 (Germany) - Level C

Reviewer information

Peer review process.

This journal engages in a double-anonymous peer review process, which strives to match the expertise of a reviewer with the submitted manuscript. Reviews are completed with evidence of thoughtful engagement with the manuscript, provide constructive feedback, and add value to the overall knowledge and information presented in the manuscript.

The mission of the peer review process is to achieve excellence and rigour in scholarly publications and research.

Our vision is to give voice to professionals in the subject area who contribute unique and diverse scholarly perspectives to the field.

The journal values diverse perspectives from the field and reviewers who provide critical, constructive, and respectful feedback to authors. Reviewers come from a variety of organizations, careers, and backgrounds from around the world.

All invitations to review, abstracts, manuscripts, and reviews should be kept confidential. Reviewers must not share their review or information about the review process with anyone without the agreement of the editors and authors involved, even after publication. This also applies to other reviewers’ “comments to author” which are shared with you on decision.

Resources to guide you through the review process

Discover practical tips and guidance on all aspects of peer review in our reviewers' section. See how being a reviewer could benefit your career, and discover what's involved in shaping a review.

More reviewer information

Calls for papers

Artificial intelligence and family business.

Submit your paper here! Introduction Artificial intelligence has become a topical issue for many family businesses due to the uncertainty around ...

Sustainability and family business

Submit your paper here! Introduction Sustainability and how companies and institutions implement social, economic and environmental practices for...

JFBM Call for Perspective Articles

Submit your article here! Deadline: 30 October 2023 Authors are invited to write a perspective article on a topic related to famil...

Thank you to the 2022 Reviewers of Journal of Family Business Management

The publishing and editorial teams would like to thank the following, for their invaluable service as 2022 reviewers for this journal. We are very grateful for the contributions made. With their help, the journal has been able to publish such high...

JFBM Call for Associate and Regional Editors

Calling for expression of interests in being a associate or regional editor for the Journal of Family Business Management. To be considered you should have published on family business management. ...

Call for Special Journal Issue Proposals

Deadline: July 30th 2023 As the new Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Family Business Management, I am calling for new special journal issue proposals that develop ideas around new and emerging topics related to...

Seeking new editorial review and advisory board members

Associate Professor Vanessa Ratten, La Trobe University - Australia, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Family Business Management As the new Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Family Business Management, I am...

Thank you to the 2021 Reviewers of Journal of Family Business Management

The publishing and editorial teams would like to thank the following, for their invaluable service as 2021 reviewers for this journal. We are very grateful for the contributions made. With their help, the journal has been able to publish such high...

Family Business: Systems, Identity and Brand

This virtual issue will run from 1st September 2022 - 30th September 2022. Business identity and brand matters and, for family businesses, that brings a distinct set of challenges aroun...

Thank you to the 2019 Reviewers for the Journal of Family Business Management (JFBM)

The academic process as we know it could not exist without the service you provide. We are grateful for your continued support of the journal: Haya Al-dajani Keanon Alderson Wassim Aloulou Carlos Arbesú Daniel...

Literati awards

Journal of Family Business Management - Literati Award Winners 2023

We are pleased to announce our 2023 Literati Award winners. Outstanding Paper Investigating Social Capital, Trust and...

Journal of Family Business Management - Literati Award Winners 2022

We are pleased to announce our 2022 Literati Award winners. Outstanding Paper Enhancing policies and measur...

Journal of Family Business Management - Literati Awards 2021

We are pleased to announce our 2021 Literati Award winners. Outstanding Paper A dynamic capabilities approa...

Journal of Family Business Management provides unrivalled coverage of all aspects of family business, offering a unique focus on behavioural and applied research in family firms, particularly considering the impact of research on policy and practice.

Aims and scope

Journal of Family Business Management (JFBM) is a refereed journal publishing since 2011. JFBM provides broad and unrivalled coverage of all aspects of family business. JFBM offers a unique focus on behavioural and applied research, particularly considering the impact of research on policy and practice; it aims to communicate the latest family business research and knowledge worldwide for the benefit of scholars and family business practitioners. Other articles unique to JFBM are our ‘In conversation with’ series which provides insights from practicing family business advisors about how they are using theory in their practice now. JFBM aims to stimulate dialogue between scholars and practitioners in a timely manner.

The family business arena is dynamic. Family business owners, managers, and practitioners need to be aware of changing management approaches, processes and strategies which allow them to respond to global competition in an increasingly chaotic world, while keeping in mind the unique character, culture, and attributes of family owned businesses.

Journal of Family Business Management is endorsed by the Family and Smaller Enterprises Research Group at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh; the Center for Family and Small Enterprises at the University of Texas at Tyler in the United States; and the International Centre for Families in Business in the United Kingdom.

Editorial objectives

Journal of Family Business Management (JFBM) is a refereed journal publishing since 2011. JFBM provides broad and unrivalled coverage of all aspects of family business. JFBM offers a unique focus on behavioural and applied research, particularly considering the impact of research on policy and practice; it aims to communicate the latest family business research and knowledge worldwide for the benefit of scholars and family business practitioners. JFBM eagerly solicits work from new scholars and in particular encourages early stage scholars to consider submitting a literature review summary, a new type of scholarly article explained in a document entitled a new type of literature review, which JFBM is pioneering. Other articles unique to JFBM are our ‘In conversation with’ series which provides insights from practicing family business advisors about how they are using theory in their practice now. JFBM aims to stimulate dialogue between scholars and practitioners in a timely manner.

Editorial criteria

JFBM publishes original, interdisciplinary, empirical, conceptual, and theoretical research on all aspects of family business. This includes research articles; high quality case studies highlighting particular successes or problems in processes or techniques; literature review summaries; ‘research notes’ providing short, digestible information of current research projects and debate; book reviews and/or evaluation of other literature in the field; and practitioner commentaries providing a practitioner view of research developments; conceptual papers; viewpoint papers. All rigorous research methods including quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodology articles are welcome. All articles will be expected to include implications in regards to society and more importantly policy.

Systems of approach and methodological concerns

Although we are an interdisciplinary journal, we seek to publish articles from the perspective of social and behavioral science. Such disciplines include management, organizational behaviour, psychology, economics, and sociology. We also seek to publish articles from the perspective of practitioners, such as family business owners, consultants, and service providers. We publish articles that use any research methodology seeking the proliferation of knowledge in the realm of family business management. All forms of empirical findings; qualitative, quantitative, or mix-methodologies are welcome. We will consider research that is conducted on all sizes of family firms from micro/small to large.

Scope/coverage

The coverage of the journal includes, but is not limited to:

- Generational differences

- Gender issues

- Family dynamics

- New/best practice and interventions

- Policy effects and issues

- Work-life balance; hours worked, vacation/time, burn-out, guilt, workoholism

- Strategic planning and organizational changes in family firms

- Corporate governance and strategy in family business

- Impact of family dynamics on management behaviours

- Organizational structures

- Family business decision making

- Belief Systems in the family enterprise religious, political, or philosophical (congruent/discordant)

- Performance

- Top management team

- Financial issues, financial management

- Resource allocation and leveraging

- International family-owned business

- Ethics; norms, mores, and morality issues

- Human capital, social capital

- Skill acquisition in the family enterprise – training, performance, feedback, growth, and expertise

- Ethnicity and transnational cultures

- Globalization trends

- Communication

- Conflict prevention/avoidance

- Succession planning

Key Benefits

- JFBM is the only journal which brings together thought leadership and applied research conducted by and with practitioners and the academic community and leading actors in the family business arena. Of particular interest are articles jointly written by practitioners and academics in the field, which offer invaluable insights into a diverse range of subjects. A main goal is narrowing the scholar/practitioner gap.

- Combining rigour through strict peer review, with relevance through a theory-into-practice ethos, JFBM is an essential resource for all involved in this dynamic area.

- JFBM is the only publication in the field to publish broad-based behavioural research in the field of family business studies.

- The journal provides a high quality outlet for academic articles on the subject of contemporary issues in family business in three key areas: trends and topical issues; strategy and management; global issues and influences and will inform, and be informed by, practice.

- The journal provides an innovative and accessible forum for young researchers in this field, publishing a number of ‘research notes’ and ‘literature reviews in brief’ in each issue.

- 'Practitioner Forums' allow family business owners and service providers to discuss what is relevant and needed to advance the field through real world application.

- Each issue will include book reviews enabling both scholars and practitioners to benefit from a succinct overview. Readers will benefit from having both a scholar and a practitioner review the same book and highlight comparisons and differences.

What does the field of research think about JFBM?

Family businesses have been substantial contributors to the world economy since time immemorial. They account for the majority of new ventures and small and medium-size enterprises. Even among large firms, family businesses dominate most economies throughout the world. Given the ever-evolving nature of families, societies, and economies, the significance of family businesses is likely to increase rather than decrease in years to come. Researchers are just beginning to appreciate the need to understand the behaviors and performance of family businesses. They are also just beginning to appreciate how exciting and interesting family businesses are to study. It will be interesting to see what is uncovered about family businesses in the years to come. Professor Jim Chrisman, Mississippi State University, United States

Latest articles

These are the latest articles published in this journal (Last updated: July 2024)

Exploring the uncharted influence of family social capital in entrepreneurial ecosystems

Uncovering the research trends of family-owned business succession: past, present and the future, fair play in family firms: examining the perceived justice of performance management systems, top downloaded articles.

These are the most downloaded articles over the last 12 months for this journal (Last updated: July 2024)

The Influence of Family Dynamics on Business Performance: Does Effective Leadership Matter?

Generation ai and family business: a perspective article., family firm performance: the effects of organizational culture and organizational social capital.

These are the top cited articles for this journal, from the last 12 months according to Crossref (Last updated: July 2024)

The relationship between the use of technologies and digitalization strategies for digital transformation in family businesses

Family entrepreneurship: a perspective article, women entrepreneurs in transport family business: a perspective article..

This title is aligned with our responsible management goal

We aim to champion researchers, practitioners, policymakers and organisations who share our goals of contributing to a more ethical, responsible and sustainable way of working.

Related journals

This journal is part of our Business, management & strategy collection. Explore our Business, management & strategy subject area to find out more.

See all related journals

Journal of Global Responsibility

Journal of Global Responsibility is the premier journal that publishes original and high-quality theoretical and...

Social Responsibility Journal

Social Responsibility Journal is the leading interdisciplinary journal publishing research in the areas of social...

Strategy & Leadership

Strategy & Leadership is a global peer reviewed journal which aims to bridge the epistemic gaps between the theory and...

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Entrepreneurship and family role: a systematic review of a growing research.

- Department of Social Psychology and Anthropology, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

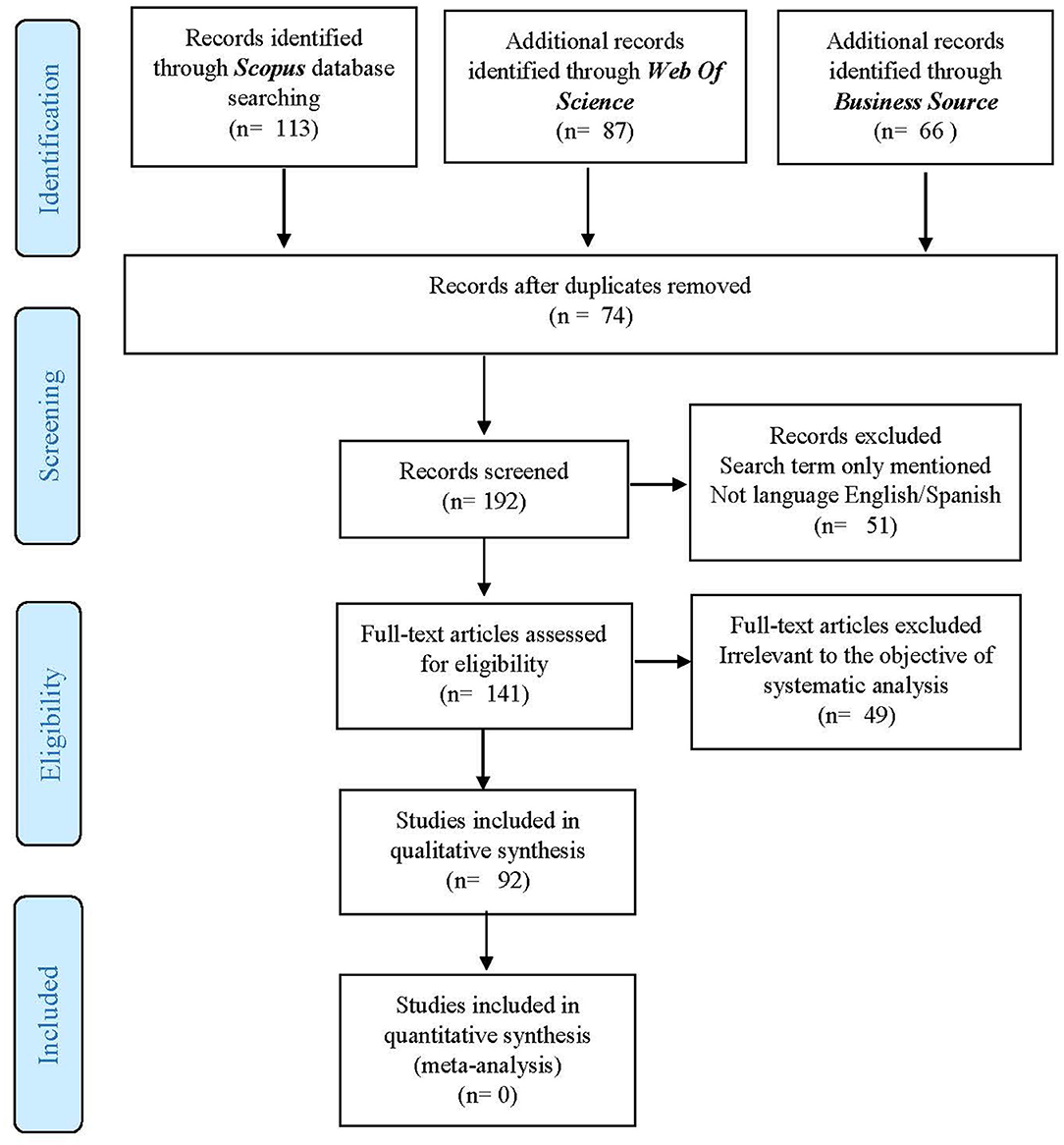

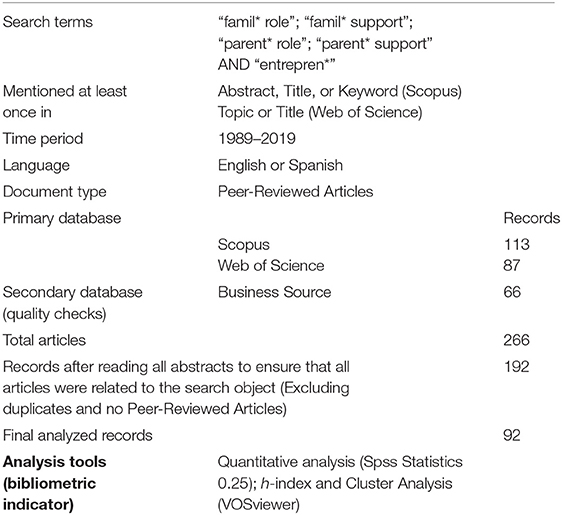

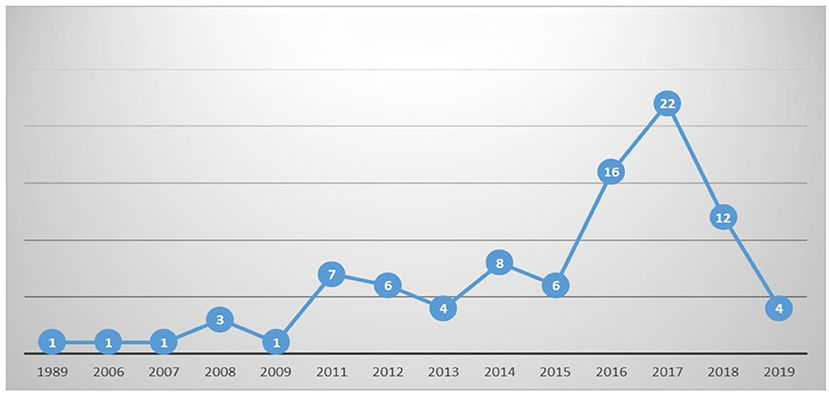

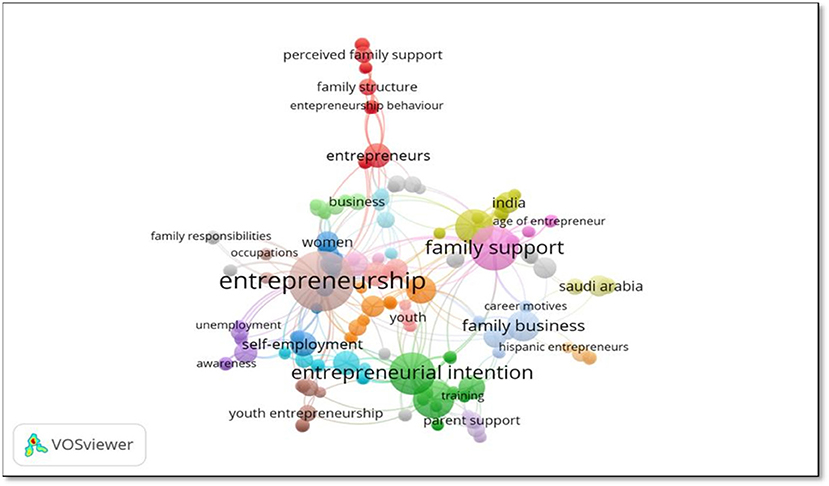

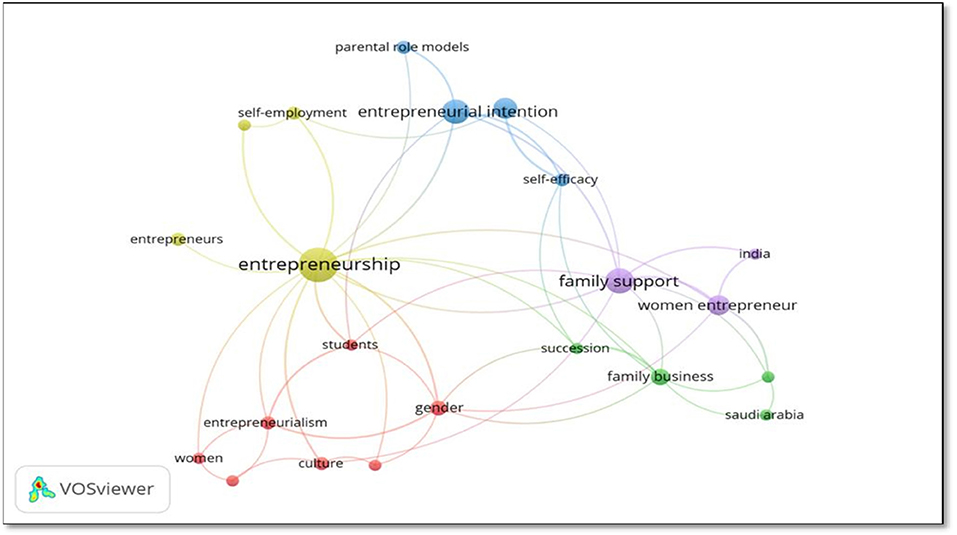

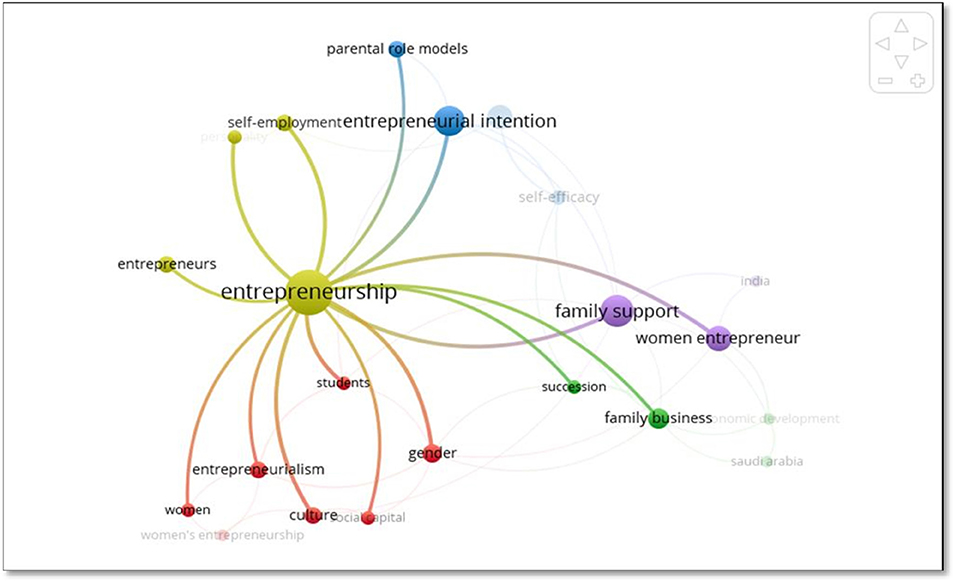

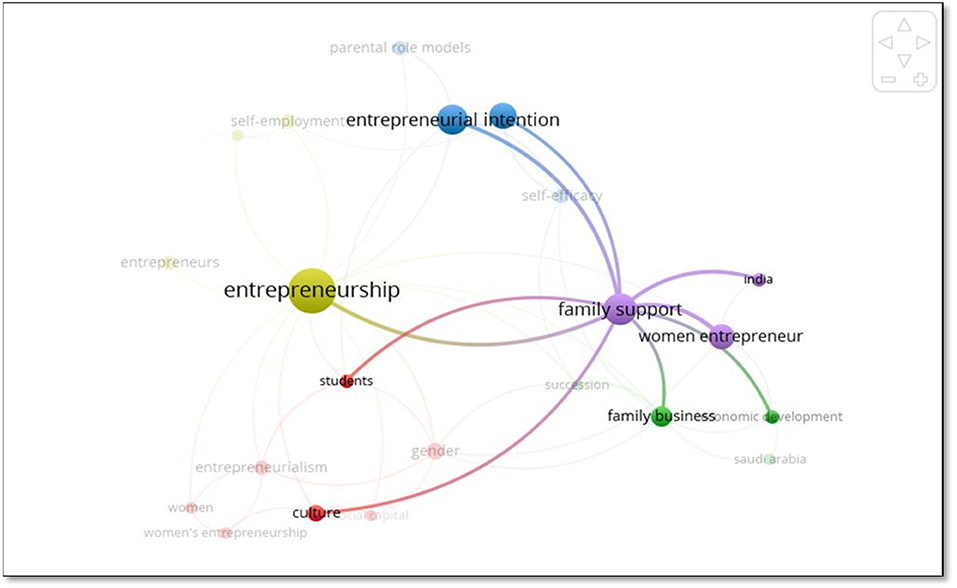

In recent years, research on the family role and entrepreneurship has increased noticeably, consolidating itself as a valid and current subject of study. This paper presents a systematic analysis of academic research, applying bibliometric indicators, and cluster analysis, which define the state of research about the relationship between family role and entrepreneurship. For this purpose, using three well-accepted databases among the research community: Scopus, Web of Science, Business Source, a total of 92 articles were selected and analyzed, published between 1989 and 2019 (until March). A cluster analysis shows five main areas of literature development: (1) cultural dimension and geneder issue; (2) family business and succession; (3) parental role models and entrepreneurial intentions; (4) entrepreneurship and self-employment; (5) family support and women entrepreneurs. Findings also show how this is a relatively recent field of study, with a multidisciplinary character.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a determining factor of economic development ( Thurik, 2009 ; Hessels and van Stel, 2011 ; Audretsch et al., 2015 ), social and structural change ( Acs et al., 1999 ; North, 2005 ). Entrepreneurship not only contributes to the economic and social growth of a nation, but also stimulates the development of knowledge ( Shane, 2000 ), technological change ( Acs and Varga, 2005 ), competitiveness and innovation ( Parker, 2009 ; Blanco-González et al., 2015 ). In fact, the European community has promoted numerous actions aimed to improve and develop the entrepreneurial attitude of European citizens toward Business venture, focusing on aspects that are essential for creating a corporate identity. However, the levels of entrepreneurial activity in some European countries are still low. According to the latest international study of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), published in 2018, Europe has the lowest TEA (Total Entrepreneurial Activity) of all regions in all age studied. This is a concerning result, especially in it's current crisis period.

Entrepreneurial activity is not just about discovering new ideas and possibilities ( Shane and Venkataraman, 2000 ), but also intentional planning, developed through the cognitive processing of internal and external factors ( Del Giudice et al., 2014 ). Intention is a cognitive process that precedes the effective involvement of the individual in any type of activity ( Liñán and Chen, 2009 ), and in particular, entrepreneurial intention is closely linked to business world ( Moriano et al., 2012 ) and has become a rapidly evolving research sector in the international scene ( Liñán and Fayolle, 2015 ).

Currently, in the literature there are two different theoretical approaches which attempt to clarify why some individuals are more inclined toward an entrepreneurial career when compared to others: the first analyzes personality traits ( Zhao and Seibert, 2006 ; Rauch and Frese, 2007 ; Leutner et al., 2014 ; DeNisi, 2015 ), the second focuses on environmental and behavioral factors ( Peterson, 1980 ; Aldrich, 1990 ; Baum et al., 2001 ). Specifically, researchers study the importance of some individual traits as factors predetermining to perform entrepreneurial activities such as high levels of self-efficacy ( Krueger et al., 2000 ; Zhao et al., 2005 ; Lee et al., 2011 ; Rasul et al., 2017 ), risk propensity ( Schwartz and Whistler, 2009 ; Tumasjan and Braun, 2012 ; Yurtkoru et al., 2014 ), tolerance to ambiguity, and uncertainty ( Hmieleski and Corbett, 2006 ; Schwartz and Whistler, 2009 ; Arrighetti et al., 2012 ), metacognitive abilities and individual abilities ( Kor et al., 2007 ; Dickson et al., 2008 ; Liñán et al., 2011 ), locus of control ( Battistelli, 2001 ; Gordini, 2013 ), as well as creativity ( Hamidi et al., 2008 ; Smith et al., 2016 ; Biraglia and Kadile, 2017 ); the environmental and behavioral focuses refers to the Social Learning Theory ( Bandura, 1986 ), according to which, individuals learn certain skills from other people, which act as models. Specifically, the term “role model” emphasizes the individual's tendency to identify with other people occupying important social and the consequent cognitive interdependence of skills and behavior patterns ( Gibson, 2004 ).