Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

18.1 Understanding Health, Medicine, and Society

Learning objectives.

- Understand the basic views of the sociological approach to health and medicine.

- List the assumptions of the functionalist, conflict, and symbolic interactionist perspectives on health and medicine.

Health refers to the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being. This definition, taken from the World Health Organization’s treatment of health, emphasizes that health is a complex concept that involves not just the soundness of a person’s body but also the state of a person’s mind and the quality of the social environment in which she or he lives. The quality of the social environment in turn can affect a person’s physical and mental health, underscoring the importance of social factors for these twin aspects of our overall well-being.

Medicine is the social institution that seeks both to prevent, diagnose, and treat illness and to promote health as just defined. Dissatisfaction with the medical establishment has been growing. Part of this dissatisfaction stems from soaring health-care costs and what many perceive as insensitive stinginess by the health insurance industry, as the 2009 battle over health-care reform illustrated. Some of the dissatisfaction also reflects a growing view that the social and even spiritual realms of human existence play a key role in health and illness. This view has fueled renewed interest in alternative medicine. We return later to these many issues for the social institution of medicine.

The Sociological Approach to Health and Medicine

We usually think of health, illness, and medicine in individual terms. When a person becomes ill, we view the illness as a medical problem with biological causes, and a physician treats the individual accordingly. A sociological approach takes a different view. Unlike physicians, sociologists and other public health scholars do not try to understand why any one person becomes ill. Instead, they typically examine rates of illness to explain why people from certain social backgrounds are more likely than those from others to become sick. Here, as we will see, our social location in society—our social class, race and ethnicity, and gender—makes a critical difference.

A sociological approach emphasizes that our social class, race and ethnicity, and gender, among other aspects of our social backgrounds, influence our levels of health and illness.

U.S. Army Garrison Japan – Arnn students celebrate diversity; weeklong recognition – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

The fact that our social backgrounds affect our health may be difficult for many of us to accept. We all know someone, and often someone we love, who has died from a serious illness or currently suffers from one. There is always a “medical” cause of this person’s illness, and physicians do their best to try to cure it and prevent it from recurring. Sometimes they succeed; sometimes they fail. Whether someone suffers a serious illness is often simply a matter of bad luck or bad genes: we can do everything right and still become ill. In saying that our social backgrounds affect our health, sociologists do not deny any of these possibilities. They simply remind us that our social backgrounds also play an important role (Cockerham, 2009).

A sociological approach also emphasizes that a society’s culture shapes its understanding of health and illness and practice of medicine. In particular, culture shapes a society’s perceptions of what it means to be healthy or ill, the reasons to which it attributes illness, and the ways in which it tries to keep its members healthy and to cure those who are sick (Hahn & Inborn, 2009). Knowing about a society’s culture, then, helps us to understand how it perceives health and healing. By the same token, knowing about a society’s health and medicine helps us to understand important aspects of its culture.

An interesting example of culture in this regard is seen in Japan’s aversion to organ transplants, which are much less common in that nation than in other wealthy nations. Japanese families dislike disfiguring the bodies of the dead, even for autopsies, which are also much less common in Japan than other nations. This cultural view often prompts them to refuse permission for organ transplants when a family member dies, and it leads many Japanese to refuse to designate themselves as potential organ donors (Sehata & Kimura, 2009; Shinzo, 2004).

As culture changes over time, it is also true that perceptions of health and medicine may also change. Recall from Chapter 2 “Eye on Society: Doing Sociological Research” that physicians in top medical schools a century ago advised women not to go to college because the stress of higher education would disrupt their menstrual cycles (Ehrenreich & English, 2005). This nonsensical advice reflected the sexism of the times, and we no longer accept it now, but it also shows that what it means to be healthy or ill can change as a society’s culture changes.

A society’s culture matters in these various ways, but so does its social structure, in particular its level of economic development and extent of government involvement in health-care delivery. As we will see, poor societies have much worse health than richer societies. At the same time, richer societies have certain health risks and health problems, such as pollution and liver disease (brought on by high alcohol use), that poor societies avoid. The degree of government involvement in health-care delivery also matters: as we will also see, the United States lags behind many Western European nations in several health indicators, in part because the latter nations provide much more national health care than does the United States. Although illness is often a matter of bad luck or bad genes, the society we live in can nonetheless affect our chances of becoming and staying ill.

Sociological Perspectives on Health and Medicine

The major sociological perspectives on health and medicine all recognize these points but offer different ways of understanding health and medicine that fall into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches. Together they provide us with a more comprehensive understanding of health, medicine, and society than any one approach can do by itself (Cockerham, 2009). Table 18.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what they say.

Table 18.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Good health and effective medical care are essential for the smooth functioning of society. Patients must perform the “sick role” in order to be perceived as legitimately ill and to be exempt from their normal obligations. The physician-patient relationship is hierarchical: the physician provides instructions, and the patient needs to follow them. |

| Conflict theory | Social inequality characterizes the quality of health and the quality of health care. People from disadvantaged social backgrounds are more likely to become ill and to receive inadequate health care. Partly to increase their incomes, physicians have tried to control the practice of medicine and to define social problems as medical problems. |

| Symbolic interactionism | Health and illness are : Physical and mental conditions have little or no objective reality but instead are considered healthy or ill conditions only if they are defined as such by a society. Physicians “manage the situation” to display their authority and medical knowledge. |

The Functionalist Approach

As conceived by Talcott Parsons (1951), the functionalist perspective on health and medicine emphasizes that good health and effective medical care are essential for a society’s ability to function. Ill health impairs our ability to perform our roles in society, and if too many people are unhealthy, society’s functioning and stability suffer. This was especially true for premature death, said Parsons, because it prevents individuals from fully carrying out all their social roles and thus represents a “poor return” to society for the various costs of pregnancy, birth, child care, and socialization of the individual who ends up dying early. Poor medical care is likewise dysfunctional for society, as people who are ill face greater difficulty in becoming healthy and people who are healthy are more likely to become ill.

For a person to be considered legitimately sick, said Parsons, several expectations must be met. He referred to these expectations as the sick role . First, sick people should not be perceived as having caused their own health problem. If we eat high-fat food, become obese, and have a heart attack, we evoke less sympathy than if we had practiced good nutrition and maintained a proper weight. If someone is driving drunk and smashes into a tree, there is much less sympathy than if the driver had been sober and skidded off the road in icy weather.

Second, sick people must want to get well. If they do not want to get well or, worse yet, are perceived as faking their illness or malingering after becoming healthier, they are no longer considered legitimately ill by the people who know them or, more generally, by society itself.

Third, sick people are expected to have their illness confirmed by a physician or other health-care professional and to follow the professional’s advice and instructions in order to become well. If a sick person fails to do so, she or he again loses the right to perform the sick role.

Talcott Parsons wrote that for a person to be perceived as legitimately ill, several expectations, called the sick role, must be met. These expectations include the perception that the person did not cause her or his own health problem.

Nathalie Babineau-Griffith – grand-maman’s blanket – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

If all of these expectations are met, said Parsons, sick people are treated as sick by their family, their friends, and other people they know, and they become exempt from their normal obligations to all these people. Sometimes they are even told to stay in bed when they want to remain active.

Physicians also have a role to perform, said Parsons. First and foremost, they have to diagnose the person’s illness, decide how to treat it, and help the person become well. To do so, they need the cooperation of the patient, who must answer the physician’s questions accurately and follow the physician’s instructions. Parsons thus viewed the physician-patient relationship as hierarchical: the physician gives the orders (or, more accurately, provides advice and instructions), and the patient follows them.

Parsons was certainly right in emphasizing the importance of individuals’ good health for society’s health, but his perspective has been criticized for several reasons. First, his idea of the sick role applies more to acute (short-term) illness than to chronic (long-term) illness. Although much of his discussion implies a person temporarily enters a sick role and leaves it soon after following adequate medical care, people with chronic illnesses can be locked into a sick role for a very long time or even permanently. Second, Parsons’s discussion ignores the fact, mentioned earlier, that our social location in society in the form of social class, race and ethnicity, and gender affects both the likelihood of becoming ill and the quality of medical care we receive. Third, Parsons wrote approvingly of the hierarchy implicit in the physician-patient relationship. Many experts say today that patients need to reduce this hierarchy by asking more questions of their physicians and by taking a more active role in maintaining their health. To the extent that physicians do not always provide the best medical care, the hierarchy that Parsons favored is at least partly to blame.

The Conflict Approach

The conflict approach emphasizes inequality in the quality of health and of health-care delivery (Conrad, 2009). As noted earlier, the quality of health and health care differ greatly around the world and within the United States. Society’s inequities along social class, race and ethnicity, and gender lines are reproduced in our health and health care. People from disadvantaged social backgrounds are more likely to become ill, and once they do become ill, inadequate health care makes it more difficult for them to become well. As we will see, the evidence of inequities in health and health care is vast and dramatic.

The conflict approach also critiques the degree to which physicians over the decades have tried to control the practice of medicine and to define various social problems as medical ones. Their motivation for doing so has been both good and bad. On the good side, they have believed that they are the most qualified professionals to diagnose problems and treat people who have these problems. On the negative side, they have also recognized that their financial status will improve if they succeed in characterizing social problems as medical problems and in monopolizing the treatment of these problems. Once these problems become “medicalized,” their possible social roots and thus potential solutions are neglected.

Several examples illustrate conflict theory’s criticism. Alternative medicine is becoming increasingly popular (see Chapter 18 “Health and Medicine” , Section 18.4 “Medicine and Health Care in the United States” ), but so has criticism of it by the medical establishment. Physicians may honestly feel that medical alternatives are inadequate, ineffective, or even dangerous, but they also recognize that the use of these alternatives is financially harmful to their own practices. Eating disorders also illustrate conflict theory’s criticism. Many of the women and girls who have eating disorders receive help from a physician, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or another health-care professional. Although this care is often very helpful, the definition of eating disorders as a medical problem nonetheless provides a good source of income for the professionals who treat it and obscures its cultural roots in society’s standard of beauty for women (Whitehead & Kurz, 2008).

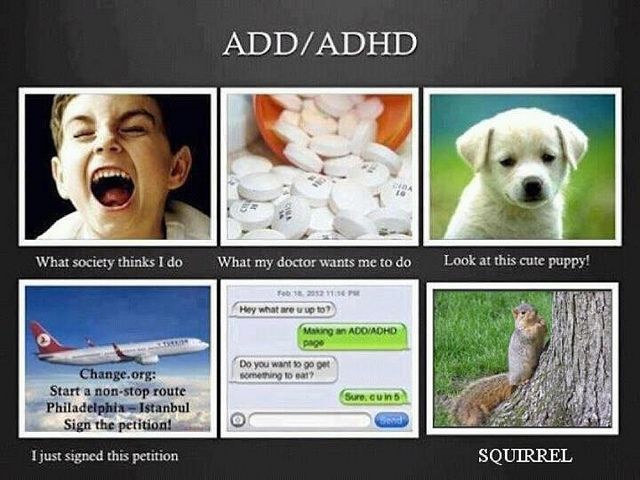

Obstetrical care provides another example. In most of human history, midwives or their equivalent were the people who helped pregnant women deliver their babies. In the 19th century, physicians claimed they were better trained than midwives and won legislation giving them authority to deliver babies. They may have honestly felt that midwives were inadequately trained, but they also fully recognized that obstetrical care would be quite lucrative (Ehrenreich & English, 2005). In a final example, many hyperactive children are now diagnosed with ADHD, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A generation or more ago, they would have been considered merely as overly active. After Ritalin, a drug that reduces hyperactivity, was developed, their behavior came to be considered a medical problem and the ADHD diagnosis was increasingly applied, and tens of thousands of children went to physicians’ offices and were given Ritalin or similar drugs. The definition of their behavior as a medical problem was very lucrative for physicians and for the company that developed Ritalin, and it also obscured the possible roots of their behavior in inadequate parenting, stultifying schools, or even gender socialization, as most hyperactive kids are boys (Conrad, 2008; Rao & Seaton, 2010).

According to conflict theory, physicians have often sought to define various social problems as medical problems. An example is the development of the diagnosis of ADHD, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

birgerking – What I Really Do… ADD/ADHD – CC BY 2.0.

Critics of the conflict approach say that its assessment of health and medicine is overly harsh and its criticism of physicians’ motivation far too cynical. Scientific medicine has greatly improved the health of people in the industrial world; even in the poorer nations, moreover, health has improved from a century ago, however inadequate it remains today. Although physicians are certainly motivated, as many people are, by economic considerations, their efforts to extend their scope into previously nonmedical areas also stem from honest beliefs that people’s health and lives will improve if these efforts succeed. Certainly there is some truth in this criticism of the conflict approach, but the evidence of inequality in health and medicine and of the negative aspects of the medical establishment’s motivation for extending its reach remains compelling.

The Interactionist Approach

The interactionist approach emphasizes that health and illness are social constructions . This means that various physical and mental conditions have little or no objective reality but instead are considered healthy or ill conditions only if they are defined as such by a society and its members (Buckser, 2009; Lorber & Moore, 2002). The ADHD example just discussed also illustrates interactionist theory’s concerns, as a behavior that was not previously considered an illness came to be defined as one after the development of Ritalin. In another example, in the late 1800s opium use was quite common in the United States, as opium derivatives were included in all sorts of over-the-counter products. Opium use was considered neither a major health nor legal problem. That changed by the end of the century, as prejudice against Chinese Americans led to the banning of the opium dens (similar to today’s bars) they frequented, and calls for the banning of opium led to federal legislation early in the 20th century that banned most opium products except by prescription (Musto, 2002).

In a more current example, an attempt to redefine obesity is now under way in the United States. Obesity is a known health risk, but a “fat pride” movement composed mainly of heavy individuals is arguing that obesity’s health risks are exaggerated and calling attention to society’s discrimination against overweight people. Although such discrimination is certainly unfortunate, critics say the movement is going too far in trying to minimize obesity’s risks (Saulny, 2009).

The symbolic interactionist approach has also provided important studies of the interaction between patients and health-care professionals. Consciously or not, physicians “manage the situation” to display their authority and medical knowledge. Patients usually have to wait a long time for the physician to show up, and the physician is often in a white lab coat; the physician is also often addressed as “Doctor,” while patients are often called by their first name. Physicians typically use complex medical terms to describe a patient’s illness instead of the more simple terms used by laypeople and the patients themselves.

Management of the situation is perhaps especially important during a gynecological exam. When the physician is a man, this situation is fraught with potential embarrassment and uneasiness because a man is examining and touching a woman’s genital area. Under these circumstances, the physician must act in a purely professional manner. He must indicate no personal interest in the woman’s body and must instead treat the exam no differently from any other type of exam. To further “desex” the situation and reduce any potential uneasiness, a female nurse is often present during the exam (Cullum-Swan, 1992).

Critics fault the symbolic interactionist approach for implying that no illnesses have objective reality. Many serious health conditions do exist and put people at risk for their health regardless of what they or their society thinks. Critics also say the approach neglects the effects of social inequality for health and illness. Despite these possible faults, the symbolic interactionist approach reminds us that health and illness do have a subjective as well as an objective reality.

Key Takeaways

- A sociological understanding emphasizes the influence of people’s social backgrounds on the quality of their health and health care. A society’s culture and social structure also affect health and health care.

- The functionalist approach emphasizes that good health and effective health care are essential for a society’s ability to function. The conflict approach emphasizes inequality in the quality of health and in the quality of health care.

- The interactionist approach emphasizes that health and illness are social constructions; physical and mental conditions have little or no objective reality but instead are considered healthy or ill conditions only if they are defined as such by a society and its members.

For Your Review

- Which approach—functionalist, conflict, or symbolic interactionist—do you most favor regarding how you understand health and health care? Explain your answer.

- Think of the last time you visited a physician or another health-care professional. In what ways did this person come across as an authority figure possessing medical knowledge? In formulating your answer, think about the person’s clothing, body position and body language, and other aspects of nonverbal communication.

Buckser, A. (2009). Institutions, agency, and illness in the making of Tourette syndrome. Human Organization, 68 (3), 293–306.

Cockerham, W. C. (2009). Medical sociology (11th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Conrad, P. (2008). The medicalization of society: On the transformation of human conditions into treatable disorders . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Conrad, P. (Ed.). (2009). Sociology of health and illness: Critical perspectives (8th ed.). New York, NY: Worth.

Cullum-Swan, B. (1992). Behavior in public places: A frame analysis of gynecological exams . Paper presented at the American Sociological Association, Pittsburgh, PA.

Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (2005). For her own good: Two centuries of the experts’ advice to women (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hahn, R. A., & Inborn, M. (Eds.). (2009). Anthropology and public health: Bridging differences in culture and society (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lorber, J., & Moore, L. J. (2002). Gender and the social construction of illness (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Musto, D. F. (Ed.). (2002). Drugs in America: A documentary history . New York, NY: New York University Press.

Parsons, T. (1951). The social system . New York, NY: Free Press.

Rao, A., & Seaton, M. (2010). The way of boys: Promoting the social and emotional development of young boys . New York, NY: Harper Paperbacks.

Saulny, S. (2009, November 7). Heavier Americans push back on health debate. The New York Times , p. A23.

Sehata, G., & Kimura, T. (2009, February 28). A decade on, organ transplant law falls short. The Daily Yomiuri [Tokyo], p. 3.

Shinzo, K. (2004). Organ transplants and brain-dead donors: A Japanese doctor’s perspective. Mortality, 9 (1), 13–26.

Whitehead, K., & Kurz, T. (2008). Saints, sinners and standards of femininity: Discursive constructions of anorexia nervosa and obesity in women’s magazines. Journal of Gender Studies, 17 , 345–358.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Sociology and Health

- First Online: 23 March 2022

Cite this chapter

- Mat Jones 3

1846 Accesses

Illness can seem random; yet, an extensive body of evidence suggests that health and disease are patterned in complex ways suggesting a more systematic and social process of disease causation. The first part of this chapter explores the social patterning of health and illness. Evidence linking social divisions, such as class, gender and ethnicity, with experiences of health and healthcare is examined. Sociology contributes to finding explanations for the persistence of social inequalities in health, as well as strategies to eliminate or reduce them.

Part 2 of the chapter explores the methodological approaches of sociology. Sociologists have looked beyond the assumed altruism of health professionals to examine the individual, group and social impact of professional practice. Sociology relies on both evidence and theory. In addition to a critical examination of evidence such as mortality rates, sociology involves the development and testing of theoretical frameworks and perspectives that seek to explain patterns of health and illness.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Determinants of Health

Data, Social Determinants, and Better Decision-making for Health: the 3-D Commission

Further reading.

Annandale, E. (2014). The Sociology of Health and Medicine: A Critical Introduction (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Google Scholar

Bartley, M. (2016). Health Inequality: An Introduction to Concepts, Theories and Methods . John Wiley & Sons.

Cockerburn, W. C. (2013). Social Causes of Health and Disease (2nd ed.). Polity.

Gabe, J., Kelleher, D., & Williams, G. (Eds.). (2006). Challenging Medicine (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Nettleton, S. (2020). The Sociology of Health and Illness (4th ed.). Polity.

Finally, it is important to remember that sociological research often appears in journals before it is described in books. Relevant journals include the Sociology of Health and Illness, Social Science and Medicine, Health, Health Risk and Society, and Frontiers in Sociology.

Ahmad, W. I. U. (1993). Making Black People Sick: “Race”, Ideology and Health Research. In W. I. U. Ahmad (Ed.), ‘Race’ and Health in Contemporary Britain (pp. 11–13). Open University Press.

Allen, L., Williams, J., Townsend, N., Mikkelsen, B., Roberts, N., Foster, C., & Wickramasinghe, K. (2017). Socioeconomic Status and Non-communicable Disease Behavioural Risk Factors in Low-income and Lower-middle-income Countries: A Systematic Review. The Lancet Global Health, 5 (3), e277–e289.

Article Google Scholar

Allik, M., Brown, D., Dundas, R., & Leyland, A. H. (2019). Differences in Ill Health and in Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health by Ethnic Groups: A Cross-Sectional Study Using 2011 Scottish Census. Ethnicity & Health , 1–19.

Armstrong, D. (1995). The Rise of Surveillance Medicine. Sociology of Health and Illness, 17 (3), 393–404.

Backett-Milburn, K., Wills, W., Gregory, S., & Lawton, J. (2006). Making Sense of Eating, Weight and Risk in the Early Teenage Years: Views and Concerns of Parents in Poorer Socio-economic Circumstances. Social Science and Medicine., 63 (3), 624–635.

Barnett, P., Mackay, E., Matthews, H., Gate, R., Greenwood, H., Ariyo, K., Bhui, K., Halvorsrud, K., Pilling, S., & Smith, S. (2019). Ethnic Variations in Compulsory Detention Under the Mental Health Act: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of International Data. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6 (4), 305–317.

Baum, F. (1999). Social Capital: Is It Good for Your Health? Issues for a Public Health Agenda. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53 , 195–196.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity . Sage.

Ben-Shlomo, Y., & Kuh, D. (2002). A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology: Conceptual Models, Empirical Challenges and Interdisciplinary Perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31 , 285–293.

Beresford, P. (2019). Public Participation in Health and Social Care: Exploring the Co-production of Knowledge. Frontiers in Sociology, 3 , 41.

Bor, J., Cohen, G. H., & Galea, S. (2017). Population Health in an Era of Rising Income Inequality: USA, 1980–2015. The Lancet, 389 (10077), 1475–1490.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste . Routledge.

Bury, M. (1982). Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption. Sociology of Health and Illness, 4 (2), 167–182.

Bury, M. (2001). Illness Narratives: Fact Or Fiction? Sociology of Health & Illness, 23 (3), 263–285.

Cameron, E., & Bernades, J. (1998). Gender and Disadvantage in Health: Men’s Health for a Change. Sociology of Health and Illness, 20 (5), 673–693.

Caraher, M., & Coveney, M. (2004). Public Health Nutrition and Food Policy. Public Health Nutrition, 7 (5), 591–598.

Caroli, E., & Weber-Baghdiguian, L. (2016). Self-Reported Health and Gender: The Role of Social Norms. Social Science & Medicine, 153 , 220–229.

Chan, K. S., Parikh, M. A., Thorpe, R. J., & Gaskin, D. J. (2019). Health Care Disparities in Race-Ethnic Minority Communities and Populations: Does the Availability of Health Care Providers Play a Role? Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7 , 1–11.

Clapp, J., & Scrinis, G. (2017). Big Food, Nutritionism, and Corporate Power. Globalizations, 14 (4), 578–595.

Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., & Solé-Auró, A. (2011). Gender Differences in Health: Results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. European Journal of Public Health, 21 (1), 81–91.

Crossley, M. (1998). ‘Sick role’ Or ‘empowerment’: The Ambiguities of Life with an HIV Positive Diagnosis. Sociology of Health and Illness, 20 (4), 507–531.

CSDH [Commission on Social Determinants of Health]. (2008). Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report , Geneva, WHO.

Cummins, S., & Macintyre, S. (2006). Food Environments and Obesity – Neighbourhood Or Nation? International Journal of Epidemiology, 35 , 100–104.

Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2015). Contribution of Food Prices and Diet Cost to Socioeconomic Disparities in Diet Quality and Health: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 73 (10), 643–660.

Davey-Smith, G. (Ed.). (2003). Health Inequalities: Lifecourse Approaches . Polity Press.

Davies, C. (1995). Gender and the Professional Predicament in Nursing . Open University Press.

DeVisser, R., & Smith, J. A. (2006). Mister in-Between – A Case Study of, Masculine Identity and Health-Related Behaviour. Journal of Health Psychology, 11 , 685–695.

Diamond, L. M. (2020). Gender Fluidity and Nonbinary Gender Identities Among Children and Adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 14 (2), 110–115.

Doyal, L. (2001). Sex, Gender and Health: The Need for a New Approach. BMJ, 323 , 1061–1063.

Durkheim, E. (1952). Suicide . Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Ehsan, A., Klaas, H. S., Bastianen, A., & Spini, D. (2019). Social Capital and Health: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. SSM-Population Health, 8 , 100425.

Everingham, C. (2001). Reconstituting Community: Social Justice, Social Order and the Politics of Community. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 36 (2), 105–122.

Fleischhacker, S. E., Evenson, K. R., Rodriguez, D. A., & Ammerman, A. S. (2011). A Systematic Review of Fast Food Access Studies. Obesity Review, 12 (5), e460–e471.

Fleming, P. J., Lee, J. G., & Dworkin, S. L. (2014). “Real Men Don’t”: Constructions of Masculinity and Inadvertent Harm in Public Health Interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 104 (6), 1029–1035.

Foster, P. (1995). Women and the Health Care Industry. An Unhealthy Relationship? Open University Press.

Foucault, M. (1976). The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception . Tavistock.

Foucault, M. (1979a). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1 . Allen Lane.

Foucault, M. (1979b). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison . Vintage.

Frank, A. W. (1991). For a Sociology of the Body: An Analytical Review. In M. F. M. Hepworth & B. Turner (Eds.), The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory . Sage.

Frank, J., Abel, T., Campostrini, S., Cook, S., Lin, V. K., & McQueen, D. V. (2020). The Social Determinants of Health: Time to Re-Think? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (16), 5856.

Frank, R. (2001). A Reconceptualization of the Role of Biology in Contributing to Race/Ethnic Disparities in Health Outcomes. Population Research and Policy Review, 20 , 441–455.

Freidson, E. (1970). Professional Dominance . Artherton.

Frost, L. (2003). Doing Bodies Differently? Gender, Youth, Appearance and Damage. Journal of Youth Studies, 6 (1), 55–70.

George, J., Mathur, R., Shah, A. D., Pujades-Rodriguez, M., Denaxas, S., Smeeth, L., Timmis, A., & Hemingway, H. (2017). Ethnicity and the First Diagnosis of a Wide Range of Cardiovascular Diseases: Associations in a Linked Electronic Health Record Cohort of 1 Million Patients. PloS One, 12 (6), e0178945.

Gidaris, C. (2019). Surveillance Capitalism, Datafication, and Unwaged Labour: The Rise of Wearable Fitness Devices and Interactive Life Insurance. Surveillance & Society, 17 (1/2), 132–138.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self Identity: A Study of Comparative Sociology . Polity Press.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma . Penguin.

Gough, B., & Conner, M. T. (2006). Barriers to Healthy Eating Amongst Men: A Qualitative Analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 62 , 387–395.

Green, J., & Dowler, D. A. (2003). Short Cuts to Safety: Risk and ‘rules of thumb’ in Accounts of Food Choice. Health, Risk and Society, 5 (1), 33–52.

Green, M. A., Evans, C. R., & Subramanian, S. V. (2017). Can Intersectionality Theory Enrich Population Health Research? Social Science & Medicine, 178 , 214–216.

Hay, K., McDougal, L., Percival, V., Henry, S., Klugman, J., Wurie, H., Raven, J., Shabalala, F., Fielding-Miller, R., Dey, A., & Dehingia, N. (2019). Disrupting Gender Norms in Health Systems: Making the Case for Change. The Lancet, 393 (10190), 2535–2549.

Higgins, J. A., Carpenter, E., Everett, B. G., Greene, M. Z., Haider, S., & Hendrick, C. E. (2019). Sexual Minority Women and Contraceptive Use: Complex Pathways Between Sexual Orientation and Health Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 109 (12), 1680–1686.

IHME [Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation] (2018). Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study .

Illich, I. (1977). The Limits to Medicine . Penguin.

Islam, M. M. (2019). Social Determinants of Health and Related Inequalities: Confusion and Implications. Frontiers in Public Health, 7 , 11.

Jecker, N. S. (2018). Age-Related Inequalities in Health and Healthcare: The Life Stages Approach. Developing World Bioethics, 18 (2), 144–155.

Johnson, T. (1993). Expertise and the State. In M. Gane & T. Johnson (Eds.), Foucault’s New Domains . Routledge.

Johnson, T. (1995). Governmentality and the Institutionalisation of Expertise. In T. Johnson, G. Larkin, & M. Saks (Eds.), Professions and the State in Europe . Routledge.

Jones, M. (2004). Anxiety and Containment in the Risk Society: Theorising Young People’s Drugs Policy. International Journal of Drug Policy, 15 , 367–376.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K., et al. (1997). Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 87 , 1491–1499.

Knight, R., Shoveller, J. A., Oliffe, J. L., Gilbert, M., Frank, B., & Ogilve, G. (2012). Masculinities, ‘guy talk’ and ‘manning up’: A Discourse Analysis of How Young Men Talk About Sexual Health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34 (8), 1246–1261.

Kurian, A. K., & Cardarelli, K. M. (2007). Racial and Ethnic Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. Ethnicity and Disease, 17 (1), 143.

Lang, T. (2020). Feeding Britain. Our Food Problems and How to Fix Them . Pelican Books.

Leigh, J. A., Alvarez, M., & Rodriguez, C. J. (2016). Ethnic Minorities and Coronary Heart Disease: An Update and Future Directions. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 18 (2), 9.

Lewington, L., Sebar, B., & Lee, J. (2018). “Becoming the man you always wanted to be”: Exploring the Representation of Health and Masculinity in Men’s Health Magazine. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 29 (3), 243–250.

Lim, W. Y., Ma, S., Heng, D., Bhalla, V., & Chew, S. K. (2007). Gender, Ethnicity, Health Behaviour & Self-Rated Health in Singapore. BMC Public Health, 7 (1), 184.

Liu, J. (2019). What Does In-Work Poverty Mean for Women: Comparing the Gender Employment Segregation in Belgium and China. Sustainability, 11 (20), 5725.

LSP [Longevity Science Panel]. (2018). Life Expectancy: Is the Socioeconomic Gap Narrowing? Available at https://www.longevitypanel.co.uk/_files/LSP_Report.pdf

Lupton, D. (1995). The Imperative of Health: Public Health and the Regulated Body . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Lupton, D. (2005). Lay Discourses and Beliefs Related to Food Risks: An Australian Perspective. Sociology of Health and Illness, 27 (4), 448–467.

Lynch, J., Due, P., & Muntaner, C. Davey Smith, G. (2000). Social Capital – Is It a Good Investment Strategy for Public Health? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54 , 404–408.

Mackenbach, J. (2019). Health Inequalities; Persistence and Change in European Welfare States . Oxford University Press.

Mackenbach, J. D., Nelissen, K. G., Dijkstra, S. C., Poelman, M. P., Daams, J. G., Leijssen, J. B., & Nicolaou, M. (2019). A Systematic Review on Socioeconomic Differences in the Association Between the Food Environment and Dietary Behaviors. Nutrients, 11 (9), 2215.

Marmot, M. (2015). The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World . Bloomsbury.

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020). Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years on . Institute of Health Equity.

Marmot, M. G., Stansfeld, S., Patel, C., North, F., Head, J., White, I., Brunner, E., Feeney, A., & Smith, G. D. (1991). Health Inequalities Among British Civil Servants: The Whitehall II Study. The Lancet, 337 (8754), 1387–1393.

Martin, G., & P, Myles L, Minion, J, Willars J, Dixon-Woods, M. (2013). Between Surveillance and Subjectification: Professionals and the Governance of Quality and Patient Safety in English Hospitals. Social Science & Medicine, 99 , 80–88.

McTaggart, L. (1996). What Doctors Don’t Tell You. The Truth About the Dangers of Modern Medicine . Thorsons.

Meeks, K. A., Freitas-Da-Silva, D., Adeyemo, A., Beune, E. J., Modesti, P. A., Stronks, K., Zafarmand, M. H., & Agyemang, C. (2016). Disparities in Type 2 Diabetes Prevalence Among Ethnic Minority Groups Resident in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 11 (3), 327–340.

Mills, C. W. (1959/2000). The Sociological Imagination . Oxford University Press.

Monteiro, C. A., Moubarac, J.-C., Cannon, G., Ng, S. W., & Popkin, B. (2013). Ultra-Processed Products Are Becoming Dominant in the Global Food System. Obesity Reviews, 14 (11), 21–28.

Moss, N. E. (2002). Gender Equity and Socioeconomic Inequality: A Framework for the Patterning of Women’s Health. Social Science and Medicine, 54 , 649–661.

Navarro, V. (1979). Medicine Under Capitalism . Croom Helm.

NVSR [National Vital Statistics Reports]. (2019). 68 (13): 1–47. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_13-508.pdf

Parsons, T. (1951). Illness and the Role of the Physician: A Sociological Perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 21 (3), 452.

Parsons, T. (1975, Summer). The Sick Role and the Role of the Physician Reconsidered. Millbank Memorial Fund Quarterly , 257–278.

Patel, N., Ferrer, H. B., Tyrer, F., Wray, P., Farooqi, A., Davies, M. J., & Khunti, K. (2017). Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Lifestyle Changes in Minority Ethnic Populations in the UK: A Narrative Review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4 (6), 1107–1119.

Pearce, M., Bray, I., & Horswell, M. (2018). Weight Gain in Mid-Childhood and Its Relationship with the Fast Food Environment. Journal of Public Health, 40 (2), 237–244.

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and Family in the Second Decade of the 21st Century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82 (1), 420–453.

Petrovic, D., de Mestral, C., Bochud, M., Bartley, M., Kivimäki, M., Vineis, P., Mackenbach, J., & Stringhini, S. (2018). The Contribution of Health Behaviors to Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health: A Systematic Review. Prev. Med. (Baltim.), 113 , 15–31.

PHE [Public Health England]. (2018). Local Action on Health Inequalities: Understanding and Reducing Ethnic Inequalities in Health . Public Health England. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/730917/local_action_on_health_inequalities.pdf

PHE [Public Health England]. (2020). Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19 . London PHE Publications. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

Phillimore, J. A., Bradby, H., & Brand, T. (2019). Superdiversity, Population Health and Health Care: Opportunities and Challenges in a Changing World. Public Health , 172 , 93–98.

Porter, S. (1999). Social Theory and Nursing Practice . Macmillan.

Portes, A. (1998). Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24 , 1–24.

Powell, B. L., Luckett, R., Bekele, A., & Chao, T. E. (2020). Sex Disparities in the Global Burden of Surgical Disease. World Journal of Surgery, 44 , 1–5.

Priest, N., Paradies, Y., Trenerry, B., Truong, M., Karlsen, S., & Kelly, Y. (2013). A Systematic Review of Studies Examining the Relationship Between Reported Racism and Health and Wellbeing for Children and Young People. Social Science & Medicine, 95 , 115–127.

Putnam, R., & D. (1995). Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Journal of Democracy, 6 (1), 65–78.

Radcliffe, E., Lowton, K., & Morgan, M. (2013). Co-construction of Chronic Illness Narratives by Older Stroke Survivors and Their Spouses. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36 (7), 993–1007.

Robertson, S. (2006). ‘Not Living Life in Too Much of an Excess’: Lay Men Understanding Health and Well-Being. Health, 10 , 175–189.

Salway, S., Carter, L., Powell, K., et al. (2014). Race Equality and Health Inequalities: Towards More Integrated Policy and Practice . Race Equality Foundation Better Health Briefing Paper 32. Race Equality Foundation.

Samari, G., Alcalá, H. E., & Sharif, M. Z. (2018). Islamophobia, Health, and Public Health: A Systematic Literature Review. American Journal of Public Health, 108 (6), e1–e9.

Sauer, A. G., Siegel, R. L., Jemal, A., & Fedewa, S. A. (2019). Current Prevalence of Major Cancer Risk Factors and Screening Test Use in the United States: Disparities by Education and Race/Ethnicity. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 28 (4), 629–642.

Schrecker, T. (2019). The Commission on Social Determinants of Health: Ten Years on, a Tale of a Sinking Stone, Or of Promise Yet Unrealised? Critical Public Health, 29 (5), 610–615.

Shakespeare, T. (2013). Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited . Routledge.

Shaw, A. (2004). Discourses of Risk in Lay Accounts of Microbiological Safety and BSE: A Qualitative Interview Study. Health Risk and Society, 6 (2), 151–171.

Small, M. J., Allen, T. K., & Brown, H. L. (2017). Global Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Seminars in Perinatology, 41 (5), 318–322.

Tai, D. B. G., Shah, A., Doubeni, C. A., Sia, I. G., & Wieland, M. L. (2020). The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 7 , 10.

Thompson, D., Johnson, K. R., Cistrunk, K. M., Vancil-Leap, A., Nyatta, T., Hossfeld, L., Rico Méndez, G., & Jones, C. (2020). Assemblage, Food Justice, and Intersectionality in Rural Mississippi: The Oktibbeha Food Policy Council. Sociological Spectrum, 40 , 1–19.

Townsend, P., & Davidson, N. (1982). Inequalities in Health: The Black Report . Penguin.

UN [United Nations]. (2020). World Population Dashboard . Available at https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population-dashboard

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-Diversity and its Implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30 (6), 1024–1054.

Villatoro, A. P., Mays, V. M., Ponce, N. A., & Aneshensel, C. S. (2018). Perceived Need for Mental Health Care: The Intersection of Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status. Society and Mental Health, 8 (1), 1–24.

Walsh, D., Bendel, N., Jones, R., & Hanlon, P. (2010). It’s Not ‘just deprivation’: Why Do Equally Deprived UK Cities Experience Different Health Outcomes? Public Health, 124 (9), 487–495.

Wang, Y. J., Chen, X. P., Chen, W. J., Zhang, Z. L., Zhou, Y. P., & Jia, Z. (2020). Ethnicity and Health Inequalities: An Empirical Study Based on the 2010 China Survey of Social Change (CSSC) in Western China. BMC Public Health, 20 , 1–12.

Wallace, S., Nazroo, J., & Bécares, L. (2016). Cumulative Effect of Racial Discrimination on the Mental Health of Ethnic Minorities in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health, 106 (7), 1294–1300.

Welch, H., Schwartz, L. M., & Woloshin, S. (2011). Overdiagnosed. Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health . Beacon Press.

WHO. (2017). Gender and Women’s Mental Health . WHO. Available at https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

Wilkinson, R. G. (1996). Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality . London: Routledge.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. (2009). The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Better . London: Allen Lane.

Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2009). Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32 (1), 20–47.

Williams, G. H. (2003). The Determinants of Health: Structure, Context and Agency. Sociology of Health and Illness, 25 , 131–154.

Witz, A. (1992). Professions and Patriarchy . Routledge.

Wong, Y. L. A., & Charles, M. (2020). Gender and Occupational Segregation. Companion to Women’s and Gender Studies , 303–325.

Zimmerman, F. J., & Anderson, N. W. (2019). Trends in Health Equity in the United States by Race/Ethnicity, Sex, and Income, 1993–2017. JAMA Network Open, 2 (6), e196386–e196386.

Zola, I. (1972). Medicine as an Institution of Social Control. Sociological Review, 20 (4), 487–504.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of the West of England, Bristol, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mat Jones .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Health, Community & Policy Studies, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK

Jennie Naidoo

London South Bank University, London, UK

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Jones, M. (2022). Sociology and Health. In: Naidoo, J., Wills, J. (eds) Health Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2149-9_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2149-9_7

Published : 23 March 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-2148-2

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-2149-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Sociological contributions to race and health: Diversifying the ontological and methodological agenda

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Associated Data

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study. This is a review article that reviews current scholarship published in the field of Sociology.

Sociologists have made fundamental contributions to the study of race and health in the United States. They have disrupted biological assumptions of race, uncovered individual and structural factors that drive racial health disparities and explored the effects of racism on health. In recent years, however, with broader shifts towards big data, the work to understand the dynamics between race and health has been increasingly pursued from a quantitative perspective. Often, such analyses isolate intermediary mechanisms to further explain race as a cause of disease. While important, these approaches potentially limit our investigations of underlying assumptions about race and the complexity of this critical social construct. We argue that the resulting dearth of qualitative research on race and health substantially limits the knowledge being produced. After providing an overview of the overwhelming shift towards quantitative methods in the study of race and health, we present three areas of study that would benefit from greater qualitative inquiry as follows: (1) Healthy Immigrant Effect, (2) Maternal Health and (3) End-of-Life Care. We conclude with a call to the discipline to embrace the critical role of qualitative research in exploring the dynamics of race and health in the United States.

INTRODUCTION

From theoretical conceptualisations of race ( Bonilla-Silva, 1999 , 2019 ; Omi & Winant, 1994 ; Ray, 2019 ) to empirical studies exploring mechanisms that drive racial inequality across all facets of social life, sociologists have extensively explored race and racialised experiences in the United States. Quantitatively, scholars have examined the relationship between race and various individual-level outcomes including socioeconomic status, educational attainment ( Telles & Ortiz, 2009 ), employment and housing (for review, see Pager & Shepherd, 2008 ). Sociologists have also analysed neighbourhood effects (for review, see Sampson et al., 2003 ) that lead to concentrated disadvantage (Du Bois, ([1899]1967)), residential segregation, and the creation of the underclass ( Massey & Denton, 1993 ; Wilson, 1987 ), which disproportionately impact people of colour. Qualitatively, scholars have focused on lived experiences, particularly those of people of colour residing in urban settings ( Desmond, 2016 ; Duneier, 2000 ). A robust sociological tradition of urban ethnography, that dates back to the 1940s, has extensively explored neighbourhood contexts and how the increased risk of marginalisation, discrimination and criminalisation directly shapes the social worlds of people of colour living in these spaces ( Goffman, 2014 ). Furthermore, more recently scholars have looked beyond the ‘urban underclass’ and instead have examined the experiences of middle class and elite racial minorities living in urban ( Pattillo, 1999 ), suburban ( Lacy, 2007 ) and rural settings ( Eason, 2017 ). While themes of marginalisation, discrimination and stigma still emerge in this work, this scholarship has also shed much needed light on the multi-dimensional lived experiences, cultural meanings, decision-making and interactional orders surrounding people of colour living in the United States.

In the subfield of medical sociology, US scholars have documented extensive racial disparities in health, often explored from a quantitative demographic tradition. For example, age-adjusted black-white death rate ratios have worsened for blacks for heart disease and cancer over the past several decades, blacks have higher rates of premature mortality than their white counterparts ( Geronimus et al., 2001 ), greater incidence and severity of hypertension ( Kershaw et al., 2011 ), obesity ( Kershaw et al., 2013 ) and Type II diabetes as well ( Bancks et al., 2017 ), and the homicide rate was over seven times higher for Black men than for White men in 2016 ( National Center for Health Statistics, 2018 ). Resonant with several aspects of broader sociological race research, explanations for these racial disparities in health often invoke differences in socioeconomic status, neighbourhood residential conditions and medical care, frequently the consequence of enduring structural inequalities and racism ( Riley, 2017 ; Sewell, 2016 ; Williams & Collins, 2001 ; Yearby, 2018 ).

Despite these strengths, however, the subfield of medical sociology exhibits some key departures from the sociological study of race more broadly. First, as noted by Williams and Sternthal in their contribution to the 2010 special issue of Journal of Health and Social Behavior , ‘for much of the twentieth century, as reflected by publications in the two leading journals in American sociology, the health of the black populations has not been a central focus of the discipline’ ( Williams & Sternthal, 2010 , p. S16). Indeed, their review of American Journal of Sociology and American Sociological Review revealed a total of only 18 publications on racial-ethnic disparities in health by 1989, with fourteen more published from 1990–2008 (six in AJS and 8 in ASR ). In that article, Williams and Sternthal identify a series of important sociological contributions to scholarship on race and health, including, for example: (1) showing that race is largely a social rather than biological category; (2) capitalising on the multidimensionality of socioeconomic status to more fully articulate its relationship to race; (3) developing multilevel constructs of racism; and (4) identifying a multitude of empirical pathways through which segregation can affect health. The authors conclude by calling for quantitative health data to be ‘routinely collected, analysed, and presented simultaneously by race, SES, and gender’ (2010, p. S23). As a whole, this 2010 review characterises flagship medical sociology research on race and health as making critical contributions but also as limited in volume and largely oriented to using quantitative operationalisation and analytic tools in the measurement of racial disparities.

Using the same search terms as Williams and Sternthal (2010 , p. S16), we observe that flagship sociological research on race and health has modestly increased in volume in the intervening decade, but retains the largely quantitative ontological and methodological orientation of earlier work. For the years 2009–2020, out of approximately 385 articles published by American Journal of Sociology , four were captured by our search for the terms ‘race and health’, ‘health inequality and race’, ‘health inequality and ethnicity’ or ‘health disparity’ in abstracts; of those, none were qualitative. For American Sociological Review , eighteen articles addressed these topics, but only three of those used qualitative methods. For Journal of Health and Social Behavior , there was a larger volume of work addressing race, health, and inequality but a similarly small proportion was qualitative (for example, 68 unique articles came up under a search for ‘race and health’, one of which used qualitative methods). In total, only four qualitative JHSB papers were captured with the full set of search terms – a meagre 1.5% of all the articles published over eleven years by American Sociological Association’s lead medical sociology journal. Thus, while flagship publication of research in these areas has certainly increased from the pre-1989 period, and perhaps shown modest gains since 2009, developments have been overwhelmingly in the analysis of large secondary data sets and negligible qualitative approaches. Furthermore, this pattern is not fully explained by assuming that qualitative studies of race and health are simply published in other outlets. A broader search of Dissertation Abstracts International and Sociological Abstracts, using the same search terms and time periods, indicates that the proportion of research on race and health that is qualitative is generally higher than in the flagship journals, yet still quite modest. For example, our search on ‘race and health’ yielded 3741 (English language) doctoral dissertations, of which 419 were qualitative (11.2%). Considering the full set of peer-reviewed scholarly articles and books listed in Sociological Abstracts, the same search yielded 1841 publications, of which 63 (3.4%) were qualitative, a figure more in line with the flagship journals. A search of current NIH grants shows a current portfolio of 35,322 grants on ‘race and health’, but only 6% of those also use qualitative methods. Based on these data, we conclude that methodological foci of US flagship journals may be partially explained by selection biases in the placement of papers but that a broad survey of sociological scholarship suggests that these trends towards quantitative investigations of race and health also hold more generally.

Critically, we are loathe to conflate ‘flagship’ with ‘quality’ in this discussion. We recognise that there is a plethora of excellent qualitative research on race and health published in outlets other than AJS, ASR and JHSB . This type of research is regularly published in respected outlets such as Social Science and Medicine , The Milbank Quarterly and Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved . Indeed, Sociology of Health and Illness has been a leader in this area for many years exploring racialised experiences across different regions and health-care contexts (e.g., see Cain & McCleskey, 2019 ; Gunaratnam 2001 ; Persson & Newman, 2008 ; Smart & Weiner, 2018 ; Younis & Jadhav, 2019 ). However, we believe this ontological and methodological dominance of quantitative approaches to studies of race and health has major implications for sociology more broadly, in the United States and internationally. The assumptions and conceptualisations embedded in the intellectual traditions we see calcifying in sociology around race and health inherently narrow the types of research questions posed, concepts developed, evidence marshalled and conclusions drawn about race and health. This dominance implicitly positions qualitative approaches to these topics as ‘alternative’ or secondary to the main discoveries.

Far from being secondary, we view this type of work as fundamental for moving beyond the treatment of race as an essentialist concept and having a deeper engagement with the ways that race is configured in relational, processual and contextual terms ( Loveman, 1999 ; Morning, 2014 ; Saperstein & Penner, 2012 ). Such understanding entails unpackaging of systems, organisations, variables, racialisation and proxies for race, all of which are embedded in cultural, social, and economic systems and resources which have the potential for multiple types of health influences ( Nazroo et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, stratification systems, including the ways that people explain, rationalise and justify their biases, are reproduced through dynamic interactions ( Bonilla-Silva, 2006 ), which are insufficiently captured in quantitative measures. Qualitative approaches are ideally equipped for the elucidation of such processes and refinement of our assumptions and theories about how race operates. These approaches can help reveal our own biases and points of stagnation as theorists and researchers.

Furthermore, the implications of these patterns are cascading and reifying, mattering for intellectual and professional reasons. To the extent that hiring, funding and career trajectories are tethered to dissemination outlets, and reputations of departments and programmes are built on those indicators of individual researchers’ successes, the type of research that is published in flagship outlets matters. Rather than be relegated to the ‘alternative’ spaces within and around sociology, we believe that qualitative research on race and health should also be central to the modern sociological agenda in order to help the field outgrow outdated essentialist conceptualisations of race and bring health research into alignment with cutting edge race theory and sociological studies of race more broadly. Without research examining assumptions about race categories, racialisation processes, and the ways that racial bias and discrimination become built into our organisations, cultures and emotional economies, our understandings of race and health will be fundamentally limited.

In this article, we examine the implications of this limited qualitative research agenda around race and health in sociology, with careful attention to the types of empirical questions being asked, the methodologies being used, and the potential gains to be had with increased ontological and methodological diversity. Here, we selected three key areas of research that would greatly advance scholarship on race and health through more qualitative inquiry: Healthy Immigrant Effect, Maternal Health and End-of-Life Care. That said, this sort of evaluation is needed in most aspects of research on race and health and could be explored in any area where race is treated as a quantitative variable related to health. We selected these areas as they: (1) represent the full spectrum of the life course; (2) are not entirely centred on clinical interactions, thus providing an opportunity to examine how race is operative upstream of medicine and how those processes are not well understood; and (3) as elaborated below, each of these subfields is faced with prolonged puzzles around the role of race and are thus ripe for qualitative inquiry.

First, we provide a general overview of the current literature in each research area, focusing on empirical studies published in the flagship US sociological journals American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology and Journal of Health and Social Behavior . We highlight successes and opportunities lost in each area and propose qualitative research agendas to fill critical gaps in the current scholarship. We must note that the broad, multidisciplinary scope of these topics makes it impossible to fully address all of the studies on each of these areas within a single article, but we do our best to provide comprehensive overviews of the research areas within the United States. We conclude with a discussion of how the dominance of quantitative methodology and ontology in sociology not only hinders intellectual advancements in scholarship on race and health, but also has cascading effects that directly shape institutions and the profession more broadly. We also consider possible reasons for these observed patterns.

HEALTHY IMMIGRANT EFFECT

The Healthy Immigrant Effect, or the Latinx Health Paradox, refers to the fact that foreign-born individuals, particularly Latinx immigrants, tend to perform better on health indicators such as all-cause mortality, infant mortality and self-rated health compared with Whites and their US-born counterparts, despite experiencing lower socioeconomic status and educational attainment ( Markides & Coreil, 1986 ; Scribner, 1996 ). The health assimilation model has been widely accepted to explain this paradox: as Latinx immigrants become more acculturated through prolonged US residence, they lose protective health effects that give them this health advantage. In recent years, however, scholars have increasingly questioned the paradox's efficacy arguing that while Latinx individuals may live longer, they tend to have faster physical decline and poorer quality of life compared with Whites ( Boen & Hummer, 2019 ).

Sociologists have confronted assumptions in the paradox primarily through quantitative methodologies that have been extensively published in the JHSB . Individual-level factors explored include socioeconomic status ( Brown et al., 2016 ), educational attainment ( Crosnoe, 2006 ), gender ( Gorman et al., 2010 ), English language proficiency ( Lebrun, 2012 ), country of origin ( Montazer & Wheaton, 2011 ), arrival year ( Hamilton et al., 2015 ) and length of residence in the United States ( Tegegne, 2018 ). Others have looked to cultural and structural factors, including intergenerational family dynamics ( Schmeer & Tarrence, 2018 ) and the impact of institutions, neighbourhoods and policies on immigrant health ( Dondero et al., 2018 ; Rosenbaum, 2008 ; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012 ). One persisting critique of the paradox is that studies have mostly ignored the health status of undocumented individuals. The available scholarship however has found that undocumented individuals are much less likely to access necessary healthcare services ( Torres & Waldinger, 2015 ) and experience an exacerbation of chronic conditions ( Hacker et al., 2011 ).

New empirical research continues to problematise the Healthy Immigrant Effect's depiction of US immigrant health. For example, the relationship between variables like citizenship and English language acquisition, common measures of acculturation and assimilation, and immigrant health do not consistently align with the paradox. Lebrun (2012) found that immigrants who remained in the United States and Canada for longer and acquired greater English proficiency, tended to have better healthcare access, utilisation and experiences with healthcare providers. Tegegne (2018) argued that immigrants who were embedded in diverse networks and acquired greater English language proficiency, reported better health over time and were less likely to be diagnosed with a chronic condition.

While quantitative scholarship on the Healthy Immigrant Effect is robust, qualitative research in the area has been ostensibly absent in the discipline's flagship journals. Sociologists who have utilised qualitative methods have frequently done so to explore the efficacy of the Latina Birth Paradox, which asserts that Latinx immigrant women have better birth outcomes than their White and US-born counterparts ( Fleuriet & Sunil, 2015 ). In their interview study of pregnant Mexican women in Texas, Fleuriet and Sunil (2015) found that while infant birth weight decreased as length of time in the United States increased and Mexican American women reported higher levels of depression and stress, Mexican immigrant women reported higher levels of anxiety directly related to the pregnancy itself. These findings resonate with recent quantitative research that also reveals that foreign-born Latina women do not necessarily have better birth outcomes than White women ( Hoggatt et al., 2012 ) or only in the context of specific birth outcomes and migration histories ( Urquia et al., 2012 ). Collectively, this research points to the ongoing need to reconsider our assumptions of immigrant health. For instance, these inconsistencies may point to the need to embrace a life-course perspective when thinking about immigrant health, recognising that health and immigrant status are fluid and deeply interconnected experiences that cannot be measured simply as single data points in time.

This relative dearth of qualitative explorations of the Healthy Immigrant Effect, which could be attributed to the model's historical roots in epidemiology and assumptions that qualitative measurement of this paradox may be too difficult, leads to persisting gaps in the literature. Variables across studies share the same name yet result in vastly different findings due to their complexity and the great variation across immigrant groups. These inconsistencies beg for greater qualitative inquiry, which is particularly well-equipped for the refinement of our assumptions related to the Healthy Immigrant Effect. One way to target these persisting puzzles would be to incorporate more qualitative inquiry to explore how the paradox relates to undocumented status, racialised experiences, discrimination and other obstacles that emerge in daily life ( Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012 ). It is important to note that there has been valuable qualitative research on immigrant experiences in health-care encounters, revealing how culture, contexts and social structures directly shape immigrants’ clinical experiences (e.g. Lo, 2010 and Lo & Stacey, 2008 ). We argue that such conceptualisations and approaches should be applied to examine the Healthy Immigrant Effect as well.

Another area of fruitful inquiry is qualitatively exploring the impact of neighbourhood effects on immigrant health. Cagney et al. (2007) found that while foreign-born Latinx have much lower rates of asthma and other respiratory conditions compared to their US-born counterparts, this advantage was contingent on the physical environment. When Latinx immigrants lived in communities with high rates of other immigrants, the respiratory health advantage remained, yet when Latinx immigrants lived in largely non-immigrant communities, their respiratory health deteriorated ( Cagney et al., 2007 ). What are the resources, opportunities and experiences in majority-immigrant communities vs. non-majority-immigrant communities that may lead to such differential health outcomes? How do neighbourhoods reproduce racial inequalities via norms, culture, and various other mechanisms? And how do individuals in a community differentially encounter agency, segregation and discrimination in different structural contexts ( Ray, 2019 ; Wingfield & Chavez, 2020 )? Participant observation, interviews and other qualitative approaches would be able to offer critical insights into these questions.

There is also value in applying qualitative methods to understand how health intersects with race, policing and the implementation of both local and federal immigration policies. Recent qualitative scholarship on policing and incarceration has elucidated the complex, and at times surprising, ways in which race operates in these contexts ( Eason, 2017 ; Western, 2018 ). Negative perceptions, fear of, and past traumatic experiences with providers and law enforcement officials may shape individual decision-making and patient–provider interactions, exacerbating inadequate access to care, leading to undetected, poor health outcomes ( Read & Reynolds, 2012 ) and expectations of poor health and survival in the long-term ( Warner & Swisher, 2015 ). Collectively, these examples of possible qualitative inquiry would help unpack both individual and structural factors that directly shape immigrant health in the United States.

MATERNAL HEALTH

Clinicians and public health scholars have primarily used quantitative methods to explain sustaining racial disparities in pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality in the United States ( Creanga et al., 2012 ). In contrast, within sociology, the relationship between race and maternal health has been less central to the research agenda, which has focused largely on reproductive health, childbearing experiences and maternal and infant outcomes. Much of the scholarship published in top US sociology journals has relied on quantitative methods and have operational-ised maternal health in terms of infant birth weight or pre-term births ( Dooley & Prause, 2005 ) and mothers’ physical and mental health ( Hartnett & Brantley, 2020 ; Williams & Finch, 2019 ). Individual maternal characteristics, like age ( Mirowsky, 2005 ), education ( Kravdal & Rindfuss, 2008 ), socioeconomic status ( Strully et al., 2010 ), employment ( Frech & Damaske, 2012 ) and relationship status ( Meadows et al., 2008 ), and structural factors, such as social networks ( Balbo & Barban, 2014 ; Sandberg, 2006 ), neighbourhood context ( Morenoff, 2003 ) and residential segregation ( Walton, 2009 ), have been targeted as critical factors that shape disparate maternal and infant health outcomes.

In the past decade, quantitative sociologists have accelerated a research agenda exploring how race impacts maternal health ( Colen et al., 2019 ; Reyes et al., 2018 ; Williams et al., 2015 ). Reyes et al. (2018) found that Black women experienced greater emotional distress during pregnancy than their White counterparts. Williams et al. (2015) found that African American women, who had a child when they were adolescents or young adults, reported worse health outcomes later in life compared with White women who had children at similar ages. Furthermore, Colen et al. (2019) found that African American women, whose children experienced acute and chronic discrimination, had faster and poorer declines in health compared to their White counterparts.

In contrast, qualitative scholarship has largely investigated the organisational, sociocultural and political structures that shape women's experiences navigating their reproductive health ( Almeling, 2007 ; Waggoner, 2017 ), pregnancy ( Armstrong, 2003 ; Casper, 1988 ; MacKendrick & Cairns, 2018 ) and childbirth within the United States ( Dillaway & Brubaker, 2006 ; Morris, 2013 ) and abroad ( Storeng et al., 2010 ; Story et al., 2012 ). While this research has provided key insights revealing experiences, mechanisms and consequences of maternal healthcare, race has largely remained on the periphery – particularly in the research that has been featured most prominently in the discipline. For instance, Almeling’s (2007) ASR article exploring the impact of sociocultural notions of gender and family on the markets of egg and sperm donation provides invaluable information on how such market dynamics result in divergent compensation, marketing tactics and interactions with egg versus sperm donors. Yet, there is little discussion of how racial backgrounds of donors and clients inevitably shape the market.

Similarly, in her study on foetal alcohol syndrome, Armstrong (2003) found that while low-income women of colour were generally less likely to drink than White women were, a small group of these women reported high levels of drinking during pregnancy. There, however, is a missed opportunity to unpack the factors that may lead to this pattern of distribution of FAS: although Armstrong (2003) notes structural inequalities that put low-income women of colour at greatest risk, much of her analytical argument focuses on how clinical and policy approaches to FAS lead to the social regulation of all women. Anthropologists, on the other hand, have delved more deeply into the relationship between race and maternal health ( Bridges, 2011 ; Davis, 2019 ; Galvez, 2019 ). Both Bridges (2011) and Gálvez (2019) found that women of colour frequently encountered racialised health-care experiences, often labelled as ‘at’ or ‘high risk’, and were subsequently subject to increased surveillance, interventions and sanctions. And Davis (2019) found that the medical racism of providers and institutions increased negative birth outcomes for African American women across different SES levels.

While maternal health research is extensive, there remain key limitations. In quantitative social scientific scholarship, conceptualisations of maternal health largely rely on infant health outcomes and mothers’ self-reported health status. Research on racial disparities is limited and primarily reveals disparities related to the ‘usual suspects’ (e.g. access to care and SES) without fully exploring broader social contexts and structural inequities. Qualitative sociological scholarship has been more minimal, with little focus on racial dynamics, which is a lost opportunity to unpack current racialised trends in maternal morbidity and mortality. For instance, recent qualitative research published in the JHSB reminds us that patient–provider interactions are directly shaped by provider perceptions ( Fenton, 2019 ; Stevens, 2016 ). Such empirical inquiry is especially necessary in maternal health, where recent publicised cases of maternal (near) deaths point to ineffective interactions with providers.

Despite repeated visits to the hospital after giving birth to her daughter, Dr. Shalon Irving, a 36-year-old African American epidemiologist at the CDC, died three weeks postpartum. Upon waiting over 7 hours for any clinical intervention after first reporting problematic symptoms, Kira Johnson, a 39-year-old African American woman in excellent health, died from the elective c-section of her second child due to haemorrhaging. Serena Williams, a sports icon, nearly lost her life after the birth of her daughter: health-care professionals initially refused to provide her with a CT scan that she requested and failed to adequately acknowledge her pain, even though she had a medical history that placed her at greater risk for maternal morbidity and mortality. These anecdotal cases disrupt the assumptions that racial health disparities largely mirror the racial distribution of poverty within our society, as these women were not short of resources yet struggled to receive necessary care.