- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Comparative Education

Introduction, general overviews.

- The Early Stage

- The 19th Century

- The 20th Century to the Present

- Education and Development

- A Codified Body of Theory and Knowledge Informing the Field

- Shifts in Paradigms

- The Case Study Approach versus Large-Scale Research

- Complexity, Continua, and Transitions

- International Testing Regimes

- Higher Education Programs and Professional Societies

- Scholarly Journals and Publications

- International and Regional Education Databanks and Statistics

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishing

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Comparative Education by Robert Arnove , Stephen Franz , Patricia K. Kubow LAST REVIEWED: 29 May 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 29 May 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0152

Comparative education is a loosely bounded field that examines the sources, workings, and outcomes of education systems, as well as leading education issues, from comprehensive, multidisciplinary, cross-national, and cross-cultural perspectives. Despite the diversity of approaches to studying relations between education and society, Arnove, et al. 1992 (cited under General Overviews ) maintains that the field is held together by a fundamental belief that education can be improved and can serve to bring about change for the better in all nations. The authors further note that comparative inquiry often has sought to discover how changes in educational provision, form, and content might contribute to the eradication of poverty or the end of gender-, class-, and ethnic-based inequities. A belief in the transformative power of education systems is aligned with three principal dimensions of the field. Arnove 2013 (cited under General Overviews ) designates these dimensions as scientific/theoretical, pragmatic/ameliorative, and global/international understanding and peace. According to Farrell 1979 (cited under General Overviews ), the scientific dimension of the field relates to theory building with comparison being absolutely essential to understanding what relationships pertain under what conditions among variables in the education system and society. Bray and Thomas 1995 (cited under General Overviews ) point out that comparison enables researchers to look at the entire world as a natural laboratory in viewing the multiple ways in which societal factors, educational policies, and practices may vary and interact in otherwise unpredictable and unimaginable ways. With regard to the pragmatic dimension, comparative educators have studied other societies to learn what works well and why. At the inception of study of comparative education as a mode of inquiry in the 19th century, pioneer Marc-Antoine Jullien de Paris (b. 1775–d. 1848) aimed at not only informing and improving educational policy, but also contributing to greater international understanding. According to Giddens 1991 , Rivzi and Lingard 2010 , and Carney 2009 (all cited under General Overviews ), international understanding has become an even more important feature of comparative education as processes of globalization increasingly require people to recognize how socioeconomic forces, emanating from what were previously considered distant and remote areas of the world, impinge upon their daily lives. The priority given to each of these dimensions varies not only across individuals but also across national and regional boundaries and epistemic communities. Yamada 2015 (cited under General Overviews ), for example, finds notable differences between the discourses and practices of North American and Japanese researchers, with the former tending to locate their research in existing theories and the latter trying to understand a particular situation before eventually finding patterns or elements applicable to a wider situation. Takayama 2011 (cited under General Overviews ) notes that one reason for differences in research traditions is the Japanese emphasis on area studies. The evolution of comparative education as a scholarly endeavor reflects changes in theories, research methodologies, and events on the world stage that have required more sophisticated responses to understanding transformations occurring within and across societies.

The references cited here include leading English-language textbooks in the field that introduce readers to the principal dimensions of comparative education, including its contributions to theory building, more informed and enlightened educational policy and practice, and international understanding and world peace. They illustrate the increasing focus of the field on how globalization impacts national education systems and, in turn, are refracted and changed by local contexts. Japan, which has one of the longest traditions of comparative studies, is included to point out differences in scholarly traditions.

Arnove, Robert F. 2013. Introduction: Reframing comparative education; The dialectic of the global and the local. In Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local . 4th ed. Edited by Robert F. Arnove, Carlos Alberto Torres, and Stephen Franz, 1–26. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

The global economy and the increasing interconnectedness of societies pose shared challenges for education worldwide. Understanding the tensions between the global and the local is necessary to reframing the field of comparative education. The global-local dialectic is explored in relation to Africa, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, and the United States.

Arnove, Robert F., Philip G. Altbach, and Gail P. Kelly. 1992. Introduction. In Emergent issues in education . Edited by Robert F. Arnove, Philip G. Altbach, and Gail P. Kelly, 1–10. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press.

The three editors/authors discuss how the book reflects the field as it emerged in the 1990s. They review the debates over theory that have remained unresolved since they emerged in the 1960s. Issues examined include modernization without Westernization, the role of international donor agencies, the reform of educational governance, public-private relations, the changing patterns of higher education, the education of girls and women, the professionalization of teaching, and the nature of literacy campaigns.

Bray, Mark, and R. Murray Thomas. 1995. Levels of comparison in educational studies: Different insights from different literatures and the value of multilevel analysis. Harvard Educational Review 65.3: 474–491.

DOI: 10.17763/haer.65.3.g3228437224v4877

The initial conceptual framework provided by Bray and Thomas constitutes a seminal contribution to comparative education that alerts scholars to the importance of multilevel units of analysis along three dimensions: geographic/local units (ranging from world/regions/ continents to that of schools/classrooms/individuals); nonlocational demographic units (ranging from ethnic/age/religious/gender groups to entire populations); and aspects of education and society (typically subjects studied, such as curriculum, teaching methods, educational finance, and management structures).

Carney, Stephen. 2009. Negotiating policy in an age of globalization: Exploring educational “policyscapes” in Denmark, Nepal, and China. Comparative Education Review 53.1: 63–68.

DOI: 10.1086/593152

The author explores the processes of policy implementation in Denmark, Nepal, and China. Carney introduces the notion of “policyscape” (one of “hyper-neoliberalism”) as a common context for understanding change efforts at different levels of education in particular localities.

Farrell, Joseph P. 1979. The necessity of comparison in educational studies: Different insights from the salience of science and the problem of comparability. Comparative Education Review 23.1: 3–16.

DOI: 10.1086/446010

In this presidential address, Farrell affirms that all sciences are comparative. The goal of science is not only to establish that relationships exist between variables, but also to determine the range over which they exist. Farrell makes a major contribution in discussing how variables in education-society relations may not be phenomenally identical, but they can be conceptually equivalent. A body of scholarship can be gradually constructed to establish comparative education as a disciplinary field of study.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. The consequences of modernity . Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

Giddens discusses the nature of social institutions at the end of the 20th century. Societies are entering a stage of “high modernity”—not post-modernity—as dominant forms of social and cultural organization have not yet been radically transformed. The current stage of world development provides previously unavailable opportunities for the well-being of humanity; however, it also poses systemic dangers resulting from totalitarian governments, degrading industrial work, environmental destruction, and militarism.

Rivzi, Fazal, and Bob Lingard. 2010. Globalizing education policy . London: Routledge.

The authors critique “the rationalist approach” to policy studies that have a narrow national focus. Instead, they offer insights into how reform trends in curriculum, pedagogy, evaluation, governance, and equity policies are located within a global framework. Their conclusions call for a new imaginary of globalization that challenges the dominance of the “neoliberal construction” of the world based in economics, while strengthening social solidarity and democratic learning within and across national borders.

Takayama, Keita. 2011. Reconceptualizing the politics of Japanese education: Reimagining comparative studies of Japanese education. In Reimagining Japanese education: Borders, transfers, circulations, and the comparative . Edited by David Blake Willis and Jeremy Rappleye, 247–285. Oxford: Symposium Books.

Takayama makes a strong case for viewing a dialogic relation between Japanese and non-Japanese research traditions that enables scholars to draw upon external transformations that have occurred in Japanese society and education in what he calls the “post-post-war time.”

Yamada, Shoko. 2015. The constituent elements of comparative education in Japan: A comparison with North America. Comparative Education Review 59.2: 234–260.

DOI: 10.1086/680172

Yamada analyzes how comparative education has been discussed and practiced in Japan, based on a questionnaire completed by members of the Japan Comparative Education Society and classification of articles published in its journal between 1975 and 2011. This information is then contrasted with North American trends identified by scholars examining research by members of the Comparative and International Education Society and articles in the Comparative Education Review (cited under Scholarly Journals and Publications ).

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Mixed Methods Research

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

- Program Information

- Students & Alumni

Master's Programs

You are here, international comparative education (ice).

The International Comparative Education (ICE) concentration is a multidisciplinary, international, cross-national program that places educational problems into a comparative framework.

The program

Master’s program.

This 12-month, full-time residential course of study combines an interdisciplinary overview of major issues in international and comparative education, development, and policy with specialized coursework in students’ areas of interest. The program’s two tracks—International Comparative Education (ICE) and International Education Policy Analysis (IEP)—focus on rigorous research, and culminate in a publishable-quality master’s paper. Flexibility and small cohort size are hallmarks of the program.

Learn more about program content

Doctoral program

The concentration in International Comparative Education also offers a doctoral degree within the Social Sciences, Humanities, and Interdisciplinary Policy Studies in Education (SHIPS) academic area. Students have the option of pursuing a concurrent master’s degree and/or a PhD minor. For general information on the doctoral specialization in ICE, visit this PhD program page . For ICE doctoral program requirements, visit the Doctoral Degree Handbook .

International Comparative Education at Stanford

ICE at Stanford affords students the opportunity to explore broadly, build community, and connect with career resources.

Why Stanford?

Stanford is known for its interdisciplinarity. Both the ICE PhD and ICE and IEPA MA programs allow students the flexibility to take courses outside of the GSE, depending on their interests and research goals. ICE students take courses at the business, law, and engineering schools, as well as in humanities and sciences. Access to top-notch faculty, and the rigor of Stanford academics are also reasons students choose ICE.

ICE students come from around the U.S. and the world. They bring a wide variety of perspectives and experiences, but share a passion for education and a desire to improve quality and accessibility for all learners. ICE students are curious, ambitious, and independent, while also enjoying the collaborative nature of small cohort learning.

Learn more about ICE students and alumni

After you graduate

Our graduates enjoy strong job placement opportunities, and go on to become leaders in a wide range of industries. As many as 30 percent of ICE and IEPA master’s graduates go on to pursue doctoral programs. Most PhD graduates pursue careers in academia. Stanford offers strong career support to students and alumni, both through GSE EdCareers and Stanford Career Education .

Learn more about careers in ICE

See all faculty

Our community

See more community stories

In the news

What you need to know

Admission requirements.

To learn more about requirements for admission, please visit the Application Requirements page .

Financing your education

To learn more about the cost of the program and options for financial support, please visit Financing Your Master’s Degree on the admissions website.

Contact admissions

For admissions webinars and to connect with the admission office, see our Connect and Visit page .

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Help & FAQ

A comparative analysis of education costs and outcomes: The United States vs. other OECD countries

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

In this paper we confirm the universality of steadily rising education expenditures among OECD nations, as predicted by "Baumol and Bowen's cost disease", and show that this trajectory of costs can be expected to continue for the foreseeable future. However, we find that while the level of education costs in America is significantly higher than that of all other OECD countries, education spending per student in the United States is increasing about as quickly as it is in many other countries-perhaps even less quickly. Although these cost increases undoubtedly will contribute to each nation's fiscal problems, we conclude that effective education contributes to improvement of the economic performance of each country and can mitigate resulting financial pressures by spurring growth in overall purchasing power.

- Cost disease

- International comparison

- Productivity

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- Economics and Econometrics

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.12.002

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Analysis of Education Business & Economics 100%

- Education costs Social Sciences 87%

- OECD Social Sciences 56%

- OECD Countries Business & Economics 54%

- Comparative Analysis Business & Economics 49%

- costs Social Sciences 33%

- education expenditures Social Sciences 29%

- purchasing power Social Sciences 25%

T1 - A comparative analysis of education costs and outcomes

T2 - The United States vs. other OECD countries

AU - Wolff, Edward N.

AU - Baumol, William J.

AU - Saini, Anne Noyes

N1 - Funding Information: We are deeply indebted to the Smith Richardson Foundation for its generous support of this work.

PY - 2014/4

Y1 - 2014/4

N2 - In this paper we confirm the universality of steadily rising education expenditures among OECD nations, as predicted by "Baumol and Bowen's cost disease", and show that this trajectory of costs can be expected to continue for the foreseeable future. However, we find that while the level of education costs in America is significantly higher than that of all other OECD countries, education spending per student in the United States is increasing about as quickly as it is in many other countries-perhaps even less quickly. Although these cost increases undoubtedly will contribute to each nation's fiscal problems, we conclude that effective education contributes to improvement of the economic performance of each country and can mitigate resulting financial pressures by spurring growth in overall purchasing power.

AB - In this paper we confirm the universality of steadily rising education expenditures among OECD nations, as predicted by "Baumol and Bowen's cost disease", and show that this trajectory of costs can be expected to continue for the foreseeable future. However, we find that while the level of education costs in America is significantly higher than that of all other OECD countries, education spending per student in the United States is increasing about as quickly as it is in many other countries-perhaps even less quickly. Although these cost increases undoubtedly will contribute to each nation's fiscal problems, we conclude that effective education contributes to improvement of the economic performance of each country and can mitigate resulting financial pressures by spurring growth in overall purchasing power.

KW - Cost disease

KW - Education

KW - International comparison

KW - Productivity

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84893515798&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=84893515798&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.12.002

DO - 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.12.002

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:84893515798

SN - 0272-7757

JO - Economics of Education Review

JF - Economics of Education Review

The Landscapes for Comparative and International Education

- First Online: 01 July 2021

Cite this chapter

- Beverly Lindsay 2

651 Accesses

This introductory chapter highlights the overall objectives and purposes of the volume, to articulate the research and significance of the field of comparative and international education and affairs experienced by Fellows of the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES). They will explicate critical components of their research and policy modalities and postulate how future directions of the field may evolve, based upon ongoing professional involvement in their specialties. Rationales for the subcategories are expounded regarding the salience of crosscutting and interdisciplinary themes. Important dimensions of the field include how the social sciences, humanities, and international affairs have affected the evolving nature of comparative and international education. Hence, the volume is centered around the following themes: (1) succinct history and selection of Fellows by professional societies; (2) conceptual, historical, and theoretical frameworks for enriching the field; (3) pedagogical epistemologies, teachers, and genders to deepen global engagement; (4) policies, practices, and paradigms emerging from applied research; and (5) movements in the new decade.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Altbach, Philip G. (1991). Trends in comparative education. Comparative Education Review , 35 (3), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1086/447049 .

Altbach, Philip G. (2016). Global perspectives on higher education . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Google Scholar

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (2020). About the academy. https://www.amacad.org/about-academy . Accessed 13 July 2020.

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2020). Mission and history. https://www.aaas.org/mission . Accessed 13 July 2020.

American Educational Research Association. (2020). Who we are. https://www.aera.net/About-AERA/Who-We-Are . Accessed 14 July 2020.

Appiah, Kwame A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Appiah, Kwame A. (2008). Chapter 6: Education for global citizenship . Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education , 107 (1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7984.2008.00133.x .

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2018). 2018–2022 strategic plan: Educating for democracy. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/about/AACU_StrategicPlan_2018-22.pdf . Accessed 28 June 2020.

Association of American Universities. (2020). AAU by the numbers. https://www.aau.edu/who-we-are/aau-numbers . Accessed 14 July 2020.

Association of Public Universities and Land-Grant Universities. (2017). Declaration on university global engagement. https://www.aplu.org/projects-and-initiatives/international-programs/declaration-on-global-engagement/index.html . Accessed 2 June 2020.

Baber, Lorenzo D., & Lindsay, Beverly. (2006). Analytical reflections on access in English higher education: Transnational lessons across the pond. Research in Comparative & International Education , 1 (2), 146–155. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2304/rcie.2006.1.2.146 .

Bourdieu, Pierre., & Passeron, Jean-Claude. (1990). Reproduction in education, society, and culture . London: Sage.

Bowles, Samuel., & Gintis, Herbert. (2012). Democracy and capitalism. London: Routledge.

Bulmer, Martin., & Solomos, John. (Eds.). (2017). Multiculturalism, social cohesion and immigration: Shifting conceptions in the UK . New York: Routledge.

Campbell, Joseph. (1976). The masks of God (Complete four volume set). New York: Penguin Books.

Carnoy, Martin. (1974). Education as cultural imperialism. New York: David McKay Co. Inc.

Carnoy, Martin. (2019). Transforming comparative education: Fifty years of theory building at Stanford. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Coles, Tony. (2020, August 10). Confronting COVID-19: Updates on treatment and response [On-the-Record Conference Call]. Council on Foreign Relations Member Conference Calls. https://www.cfr.org/conference-calls/covid-19-updates-treatment-and-response . Accessed 15 September 2020.

Commission on The Abraham Lincoln Study Abroad Fellowship Program. (2005, November). Global competence & national needs: One million Americans studying abroad. https://www.nafsa.org/sites/default/files/ektron/uploadedFiles/NAFSA_Home/Resource_Library_Assets/CCB/lincoln_commission_report%281%29.pdf . Accessed 12 July 2020.

Comparative and International Education Society. (2018). CIES awards. https://www.cies.us/page/Awards . Accessed 14 July 2020.

Cowen, Robert., & Kazamias, Andreas M. (Eds.). (2009). International handbook of comparative education (Vol. 22). New York: Springer.

Crossley, Michael. (2014). Global league tables, big data and the international transfer of educational research modalities. Comparative Education , 50 (1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.871438 .

Crossley, Michael., Arthur, Lore., & McNess, Elizabeth. (Eds.). (2016). Revisiting insider-outsider research in comparative and international education . Oxford: Symposium Books Ltd.

Crossley, Michael., Gu, Qing., Barrett, Angeline M., Brown, Lalage., Buckler, Alison., Christensen, Carly., Janmaat, Jan Germen., McCowan, Tristan., Preston, Rosemary A., Singal, Nidhi., & Trahar, Sheila. (2018). Celebration, reflection and challenge: The BAICE 20th anniversary. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education , 48 (5), 801–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1499219 .

Epstein, Erwin H. (Ed.). (2016). Crafting a global field: Six decades of the Comparative and International Education Society . Hong Kong: Springer.

Fraser, Stewart E. (1964). Jullien’s plan for comparative education, 1816–1817 . New York: Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Geiger, Roger L., & Sá, Creso M. (2009). Tapping the riches of science: Universities and the promise of economic growth . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ginsburg, Mark. (2017). Teachers as human capital or human beings? USAID’s perspective on teachers Current Issues in Comparative Education (CICE) , 20 (1), 6–30. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1170256.pdf . Accessed 28 August 2020.

Gramlich, John. (2019, July 10). For World Population Day, a look at the countries with the biggest projected gains—and losses—by 2100. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/10/for-world-population-day-a-look-at-the-countries-with-the-biggest-projected-gains-and-losses-by-2100/ . Accessed 3 June 2020.

Haass, Richard. (2020). The world: A brief introduction . New York: Penguin Press.

Higher Education Statistics Agency. (2019). Figure 18—HE qualifications obtained by subject area and sex. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/17-01-2019/sb252-higher-education-student-statistics/qualifications . Accessed 6 July 2020.

Holmes, Brian. (1981). Comparative education: Some considerations of method . New York: Routledge.

Kelly, Gail P., & Slaughter, Sheila. (Eds.). (1991). Women’s higher education in comparative perspective. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

King, Edmund J. (2012). Comparative studies and educational decision . New York: Routledge.

Klees, Steven. (2017). Will we achieve education for all and the education sustainable development goal? Comparative Education Review , 61 (2), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1086/691193 .

Knight, Jane., & de Wit, Hans. (2018). Internationalization of higher education: Past and future. International Higher Education , (95), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2018.95.10715 .

Lindsay, Beverly. (Ed.). (1980). Comparative perspectives of Third World women: The impact of race, sex, and class . New York: Praeger.

Lindsay, Beverly. (2012). Articulating domestic and global university descriptors and indices of excellence. Comparative Education , 48 (3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.613279 .

Lindsay, Beverly., & Blanchett, Wanda J. (Eds.). (2011). Universities and global diversity: Preparing educators for tomorrow . New York: Routledge.

Loader, Rebecca., & Hughes, Joanne. (2017). Balancing cultural diversity and social cohesion in education: The potential of shared education in divided contexts. British Journal of Educational Studies , 65 (1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1254156 .

Loss, Christopher P. (2014). Between citizens and the state: The politics of American higher education in the 20th century . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lovelace Jr., Berkeley. (2020 July 22). Dr. Anthony Fauci warns the coronavirus won’t ever be eradicated. CNBC.com . https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/22/dr-anthony-fauci-warns-the-coronavirus-wont-ever-be-totally-eradicated.html . Accessed 28 August 2020.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Fast facts degrees conferred by race and sex. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=72 . Accessed 1 June 2020.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). The condition of education: International comparisons: Reading, mathematics, and science literary of 15-year old students. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cnu.asp . Accessed 1 June 2020.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk . https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/risk.html . Accessed 11 July 2020.

Noah, Harold J., & Eckstein, Max A. (1998). Doing comparative education: Three decades of collaboration . Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Phillips, David., & Schweisfurth, Michele. (2014). Comparative and international education: An introduction to theory, method, and practice (2nd Edition). London: Bloomsbury.

Rizvi, Fazal., & Choo, Suzanne S. (2020). Education and cosmopolitanism in Asia: An introduction. Asia Pacific Journal of Education , 40 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1725282 .

Rodney, Walter. (2018). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. London: Verso.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. (2020). The ages of globalization . New York: Columbia University Press.

Sanger, Catherine S., & Gleason, Nancy W. (Eds.). (2020). Diversity and inclusion in global higher education Lessons from across Asia . Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schleicher, Andreas. (2019). PISA\2018: Insights and interpretations. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA%202018%20Insights%20and%20Interpretations%20FINAL%20PDF.pdf . Accessed 30 May 2020.

Schuelka, Matthew J., Johnstone, Christopher J., Thomas, Gary., & Artiles, Alfredo J. (Eds.). (2019). The SAGE handbook of inclusion and diversity in education . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stevens, Matthew C. (2015, February 19). Janet Napolitano urges ‘passionate conversation” on higher education. USC News . https://news.usc.edu/76189/janet-napolitano-urges-passionate-conversation-on-higher-education/ . Accessed 3 July 2020.

Straubhaar, Rolf. (2020). Teaching for America across two hemispheres: Comparing the ideological appeal of the Teach for All Teacher Education Model in the United States and Brazil. Journal of Teacher Education , 71 (3), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119845635 .

Tatto, Maria T., Richmond, Gail., & Carter Andrews, Dorinda J. (2016). The research we need in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education , 67 (4), 247–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116663694 .

Wallerstein, Immanuel. (2004). World-systems analysis: An introduction . Durham: Duke University Press.

Wilson, David N. (1994). Comparative and international education: Fraternal or siamese twins? A preliminary genealogy of our twin fields. Comparative Education Review , 38 (4) 449–486.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021a, February 8). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int . Accessed 8 February 2021.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2021b, February 8). United States of America: WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/us . Accessed 8 February 2021.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of California, California, USA

Beverly Lindsay

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Lindsay, B. (2021). The Landscapes for Comparative and International Education. In: Lindsay, B. (eds) Comparative and International Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64290-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64290-7_1

Published : 01 July 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-64289-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-64290-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IOE - Faculty of Education and Society

- Departments and centres

- Innovation and enterprise

- Teacher Education College

Cross-cohort comparative analysis in the British cohort studies

22 May 2024, 12:00 pm–1:00 pm

Join this event to hear David Bann and Liam Wright explore some methods for comparative research with the British cohort studies.

This event is free.

Event Information

Availability.

This webinar focuses on conducting cross-study comparisons across time, in the British birth cohorts and other datasets and provides insights into the benefits and importance of conducting cross-study comparisons in the social and health sciences – offering guidance and suggestions on methodological issues and other considerations.

The speakers will briefly discuss the opportunities of cross-study comparison research, and emphasise key areas to consider including target populations, measurement, harmonisation and interpretation.

The guidance offered applies when using any of the CLS cohorts or similar studies. This online webinar will be followed by a Q&A, with a recording published on the CLS YouTube channel after the event.

This online event will be particularly useful for early career researchers.

Related links

- Centre for Longitudinal Studies

- Social Research Institute

About the Speakers

Dr david bann.

Associate Professor in Population Health at the Centre for Longitudinal Studies

His research focuses on how health is distributed, its underlying causes, and how this knowledge can be used to enhance public health.

Dr Liam Wright

Lecturer in Statistics and Survey Methodology at the Centre for Longitudinal Studies

Related News

Related events, related case studies, related research projects, press and media enquiries.

UCL Media Relations +44 (0)7747 565 056

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Clinical decision making: validation of the nursing anxiety and self-confidence with clinical decision making scale (NASC-CDM ©) into Spanish and comparative cross-sectional study in nursing students

- Daniel Medel ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-5883-295X 1 ,

- Tania Cemeli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6683-3756 1 ,

- Krista White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4179-5383 2 ,

- Williams Contreras-Higuera ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4872-1590 3 ,

- Maria Jimenez Herrera ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2599-3742 4 ,

- Alba Torné-Ruiz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8072-1953 1 , 5 ,

- Aïda Bonet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7382-114X 1 , 6 &

- Judith Roca ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0645-1668 1 , 6

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 265 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

112 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Decision making is a pivotal component of nursing education worldwide. This study aimed to accomplish objectives: (1) Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence with Clinical Decision Making (NASC-CDM©) scale from English to Spanish; (2) Comparison of nursing student groups by academic years; and (3) Analysis of the impact of work experience on decision making.

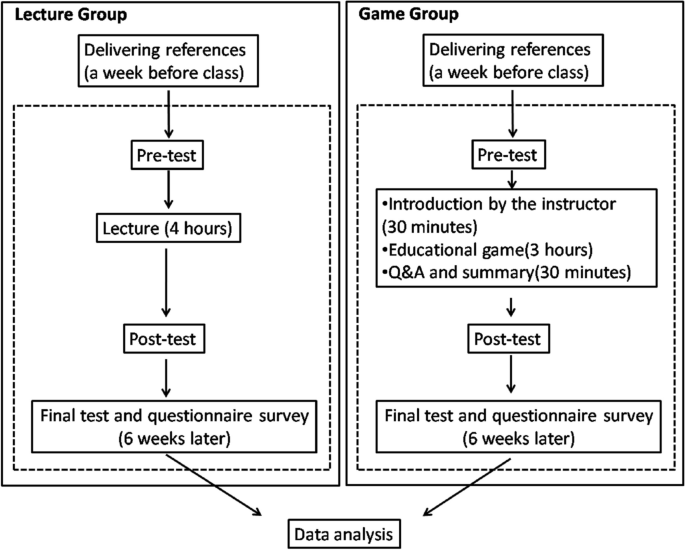

Cross-sectional comparative study. A convenience sample comprising 301 nursing students was included. Cultural adaptation and validation involved a rigorous process encompassing translation, back-translation, expert consultation, pilot testing, and psychometric evaluation of reliability and statistical validity. The NASC-CDM© scale consists of two subscales: self-confidence and anxiety, and 3 dimensions: D1 (Using resources to gather information and listening fully), D2 (Using information to see the big picture), and D3 (Knowing and acting). To assess variations in self-confidence and anxiety among students, the study employed the following tests: Analysis of Variance tests, homogeneity of variance, and Levene’s correction with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

Validation showed high internal consistency reliability for both scales: Cronbach’s α = 0.920 and Guttman’s λ2 = 0.923 (M = 111.32, SD = 17.07) for self-confidence, and α = 0.940 and λ2 = 0.942 (M = 80.44, SD = 21.67) for anxiety; and comparative fit index (CFI) of: 0.981 for self-confidence and 0.997 for anxiety. The results revealed a significant and gradual increase in students’ self-confidence ( p =.049) as they progressed through the courses, particularly in D2 and D3. Conversely, anxiety was high in the 1st year (M = 81.71, SD = 18.90) and increased in the 3rd year (M = 86.32, SD = 26.38), and significantly decreased only in D3. Work experience positively influenced self-confidence in D2 and D3 but had no effect on anxiety.

The Spanish version (NASC-CDM-S©) was confirmed as a valid, sensitive, and reliable instrument, maintaining structural equivalence with the original English version. While the students’ self-confidence increased throughout their training, their levels of anxiety varied. Nevertheless, these findings underscored shortcomings in assessing and identifying patient problems.

Peer Review reports

Decision making in nursing is a critical process that all nurses around the world use in their daily practice, involving the assessment of information, the identification of health issues, the establishment of care objectives, and the selection of appropriate interventions to address the patient’s health problems [ 1 , 2 ]. Nursing professionals must effectively apply their knowledge, skills, and clinical judgment to ensure the delivery of safe and high-quality care within the context of complex and ever-evolving situations [ 3 ]. For nearly 25 years, clinical decision-making has been highlighted as one of the key aspects of nursing practice [ 2 , 4 ].

Decision making in nursing does not follow a linear relationship that culminates in the decision made; instead, it has a circular nature that repeats through data collection, alternative selection, reasoning, synthesis, and testing [ 5 ]. Expert nurses, moreover, possess the ability to discern patterns and trends within clinical situations, providing them with a general overview of patient issues and facilitating decision making [ 6 ]. In this iterative and dynamic process, a solid knowledge base, clinical experience, reliable information, and a supportive environment are crucial pillars underpinning clinical decisions [ 7 ]. Therefore, nursing students, during their educational journey, require the support of others in decision making [ 4 ] and adequate training that optimizes their learning opportunities [ 8 ]. Clinical decision-making forms the cornerstone of professional nursing practice [ 9 ].

The process of decision making regarding patient care integrates theoretical knowledge with hands-on experience [ 10 ]. This practical experience has been instrumental in augmenting analytical skills, intuition, and cognitive strategies essential for determining sound judgment and decision-making in complex situations [ 11 ]. Although students’ clinical experience is limited, some of them work as nursing assistants or in support roles. This profile of nursing student is quite common [ 12 ]. Hence, prior work experience in healthcare should be considered in nursing students.

Additionally, it has been suggested that emotional factors, such as heightened levels of anxiety and low self-confidence, may influence clinical decision-making processes [ 13 ]. The Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence with Clinical Decision Making (NASC-CDM©) scale is used to make a self-report of how they feel about students’ self-confidence and anxiety levels during clinical decision-making [ 14 ] On one hand, nursing students frequently grapple with elevated stress and anxiety, which adversely affect their learning process [ 15 ]. Conversely, self-confidence is defined as a person’s self-recognition of their abilities and capacity to recognize and manage their emotions [ 16 ]. Self-confidence can foster well-being by strengthening positive emotions among nursing students [ 17 ]. In this regard, one of the leading authors in the study of self-confidence is Albert Bandura (1977) [ 18 ]. He employs the term self-efficacy to describe the belief that one holds in being capable of successfully performing a specific task to achieve a given outcome. Consequently, it can be considered a situationally specific self-confidence [ 19 ]; however, these terms are related to potential emotional barriers in decision making [ 20 ].

In line with the aforementioned, and as a rationale for this study, it should be noted that the NASC-CDM© scale offers significant contributions. Firstly, it highlights the ability to address self-reported levels of self-confidence and anxiety, both independently and interrelatedly, as these two are two distinct constructs with relevant effects on clinical decision making. This separation allows for a more comprehensive and precise understanding of the context [ 21 ]. Secondly, it is worth noting that the scale can be administered to both students and professionals [ 22 ]. The results obtained through this scale enable the identification of areas in which students need improvement and provide nursing educators the opportunity to develop strategies to strengthen students’ clinical decision-making skills [ 14 ].

The absence of a validated Spanish version of the Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence with Clinical Decision Making (NASC-CDM©) scale poses a significant challenge for researchers and educators. This limitation hinders the accurate assessment of self-confidence and anxiety levels among Spanish-speaking nursing students and professionals in both clinical decision-making both academic and healthcare settings. In heath research, the availability of reliable measurement tools is crucial to ensure accuracy and comparability across cultural and linguistic contexts [ 23 ]. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the NASC-CDM© scale is not only accessible in English [ 14 ] but also in other languages such as Turkish [ 24 ] and Korean [ 22 ], Therefore, its availability in Spanish presents numerous opportunities for cross-cultural comparisons in academic and healthcare settings, as well as between academic and clinical researchers.

Hence, this study aims to address two deficits in the Spanish context: first, to validate the NASC-CDM© scale in Spanish, and second, to employ it to assess self-confidence and anxiety levels in decision making among nursing students by academic year and the influence of prior work experience. By achieving these objectives, the study seeks to provide educators with essential insights to enhance the teaching and learning process in both academic and environments. Additionally, it aims to offer support students in enhancing their decision-making skills, ultimately fostering the development of proficient healthcare professionals capable of delivering care. Therefore, this study was designed to achieve three primary objectives: (1) To perform a cross-cultural and psychometric validation of the Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence scale with the Clinical Decision Making (NASC-CDM©) from English to Spanish Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence with Clinical Decision Making– Spanish (NASC-CDM-S©) scale.; (2) To compare groups of nursing students from their first to fourth academic year in terms of anxiety and self-confidence in their decision-making processes; and (3) To Investigate the potential impact of the participants’ work experience on their decision-making abilities. Hence, concerning objectives 2 and 3, the following hypothesis was posited: participants in higher academic years and participants with work experience have higher levels of self-confidence and lower levels of anxiety in their decision-making processes.

This study adopted a quantitative cross-sectional and analytical approach.

Setting and sampling

The study population comprised nursing students from the Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida (Spain). The nursing degree program in Spain consists of 240 European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) credits, approximately equivalent to 6000 h, distributed across 4 academic years (60 ECTS per year, totaling 1500 h per year). One ECTS credit corresponds to 25–30 study hours (Royal Decree 1125/2003). The first year primarily focuses on theoretical training in basic sciences, with more specific nursing sciences covered in higher years. Clinical practices gradually increase, with the fourth year being predominantly practical (1st year 6 ECTS, 2nd year 12 ECTS, 3rd year 24 ECTS, and 4th year 39 ECTS).

A convenience sample of 301 participants was used, representing a non-probability sampling method [ 25 ]. The sample size aligns with the recommended person-item ratio, with a minimum of 10 subjects per item for general psychometric approaches and 300–500 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) or conducting propriety analysis [ 23 ]. The NASC-CDM© scale contains 27 items. Inclusion criteria were nursing students from all four academic years who were willing to participate, and no exclusion criteria were specified. Participants received no compensation, and their participation was voluntary.

Instrument and variables

The original version of the NASC-CDM© tool was developed by White [ 14 , 21 ]. The use of this tool for the study was authorized in May 2022 through email communication with the instrument’s creator.

Regarding the original instrument, it is noteworthy that it was validated through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with 545 pre-licensure nursing students in the United States. The analysis revealed moderate convergent validity and significant correlations between the self-confidence and anxiety variables that constitute two separate sub-scales within the same instrument. The instrument achieved a Cronbach’s α of 0.98 for self-confidence and 0.94 for anxiety [ 14 , 21 ]. This instrument comprises 27 items and uses a 6-point Likert scale for responses (1 = Not at all; 2 = Only a little; 3 = Somewhat; 4 = Mostly; 5 = Almost completely; 6 = Completely). Scores range from 27 to 162 points. The EFA results confirmed a scale with three dimensions (D1, D2, and D3):

D1 (Using resources to gather information and listening fully) includes statements about recognizing clues or issues and assessing their clinical significance. This dimension comprises 13 items, with a minimum score of 13 and a maximum of 78.

D2 (Using information to see the big picture) includes statements about determining the patient’s primary problem. This dimension contains 7 items, with a minimum score of 7 and a maximum of 42.

D3 (Knowing and acting) includes statements about performing interventions to address the patient’s problem. This dimension consists of 7 items, with a minimum score of 7 and a maximum of 42.

Based on the original tool, the questionnaire used in this study consisted of two parts. It included the following variables: (a) sociodemographic data such as age (numeric), gender (male, female, non-binary), academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th), university entrance pathway (secondary school, training courses, other university degrees, over 25–45 years old), and participants’ work experience in healthcare (Yes or No); and (b) 27 paired statements about students’ perceptions of their level of self-confidence and anxiety (dependent variable) in decision making as per the translated NASC-CDM©. Regarding work experience, it should be noted that some nursing students work in healthcare facilities as nursing assistants or in support roles during their nursing studies.

Instrument validation

The tool presented by White [ 14 ] underwent translation and adaptation, following the guidance provided by Sousa & Rojjanasrirat [ 23 ] and Kalfoss [ 26 ]. In the forward-translation (English to Spanish) and back-translation phases, two independent bilingual translators participated, who were not part of the research team and who usually work with health-related translations. The back-translated version of the scale was reviewed and approved by the tool’s creator (Dr. White). These steps ensured content validity.

In the expert panel phase, 5 expert nurse educators from our university who were not part of the research team, with a doctoral degree and more than 5 years of teaching experience, assessed content relevancy. The scale proposed by Sousa & Rojjanasrirat [ 23 ] (1 = not relevant, 2 = unable to assess relevance, 3 = relevant but needs minor alteration, 4 = very relevant and succinct), along with the Kappa index were used to assess agreement. The educators rated the 27 items between 3 and 4. The concordance analysis yielded a score of 0.850, which, as per Landis & Koch [ 27 ], is considered nearly perfect. Only some expressions were modified for better cultural adaptation while retaining the original meaning of the statements. Finally, a pilot test was conducted during the pre-testing phase, involving 20 students, to assess comprehension and completion time. The students encountered no comprehension difficulties, and the average response time was 13 min. Therefore, it was concluded that the questionnaire was feasible in terms of time required taken and clarity of the questions/answers [ 28 ].

This validation process concludes with the psychometric testing of the prefinal version of the translated instrument. During this phase, the psychometric properties are established using a sample from the target population, in this case, nursing students [ 23 ]. The psychometric characteristics examined include: (1) the reliability of internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α) and Guttman split-half coefficients (λ2); (2) criterion validity, where the concurrent validity of the new version of the instrument was assessed against the original version via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and (3) for construct and structural validity, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and CFA were conducted to demonstrate the discriminant validity of the instrument by comparing groups within the sample.

Data collection

Data collection took place between May 2022 and June 2023. The lead researcher in a classroom administered the questionnaire in a paper format. Response times ranged from 10 to 15 min.

Data analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis of the participants’ study variables was conducted. Reliability was determined using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α) and Guttman split-half coefficients (λ2) for both sub-scales (self-confidence and anxiety) and their respective dimensions (D1, D2, D3). Cronbach’s provides a measure of item internal consistency, while Guttman split-half coefficient assesses the extent to which observed response patterns align with those expected from a perfect scale [ 29 ]. Item correspondence was reviewed by repeating the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the extraction and rotation methods outlined by the tool’s creator [ 14 , 21 ]. Factor validity was confirmed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), where a value ≥ 0.9 of the fit indices (comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI), and Bollen’s Incremental Fit Index (IFI) indicate reasonable fit [ 30 ]. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the unweighted least square (ULS) estimator was used Likert ordinal data [ 31 ]. Sample adequacy was also reviewed using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), Bartlett’s sphericity test, and average variance extracted (AVE).

Normality tests for self-confidence and anxiety data distribution ( N = 301) were performed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (K-S = 0.043 and 0.41; p >.05) and multivariable normality (Shapiro-Wilk = 0.993 and 994; p >.05). The results indicated that all dimensions followed a normal distribution. Consequently, parametric tests such as Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and group comparison tests (t-Student) were employed. To analyze differences in self-confidence and anxiety among students by academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th), the following tests were conducted: analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, homogeneity of variance tests, and Levene’s test applying Tukey’s post hoc correction to p -values for combined groups correction for combined groups. Effect sizes were determined using Cohen’s d for t-student tests and eta-squared (η²) for ANOVA tests.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 and JASP 0.18.1. A significance level was set at p <.05 for all analyses.

The results are presented in 4 sections: (1) Descriptive data of the participants, (2) Psychometric validation study of the NASC-CDM© questionnaire in Spanish (NASC-CDM-S©), (3) Comparative analysis of self-confidence and anxiety in decision making by academic year, and (4) The impact of students’ work experience on their decision-making processes.

Descriptive data of the participants

The nursing study involved 301 participants, mostly women who entered through high school. The sample comprised students from the 1st year of the degree (28.57%, with an average age of 20.43 years), 2nd year (38.54%, with an average age of 21.10 years), 3rd year (3.29%, with an average age of 23.90 years), and 4th year (19.60%, with an average age of 22.92 years). Nearly 2/3 of the participants entered the nursing program from secondary school, and just over 50% had work experience in healthcare. See Table 1 for Sample Characteristics.

Psychometric validation study of the NASC-CDM© questionnaire in Spanish

The set of items showed high internal consistency reliability in both sub-scales. In self-confidence, Cronbach’s α = 0.920, and Guttman’s λ2 = 0.923 (M = 111.32, SD = 17.07) and in anxiety the values were α = 0.940 and λ2 = 0.942 (M = 80.44, SD = 21.67). The KMO adequacy measure was 0.921 for self-confidence and 0.946 for anxiety, and Bartlett’s sphericity was highly significant, resulting in a p -value not exceeding 0.05, indicating a significantly different item correlation matrix (self-confidence χ2 = 4250.632, p <.001; anxiety χ2 = 5612.051, p <.001). In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) index exceeded 0.50, confirming the suitability of the original variables in both sub-scales for structure detection.

To confirm the validity of the factors, agreement of item alignment with the dimensions of the original tool was first examined through EFA (factor loading > 0.4), followed by a confirmatory analysis of the entire scale using CFA. Repeating the EFA, as conducted by White (2011) using alpha factoring extraction and Promax rotation with 3 factors (no eigenvalue), the total variance explained in both scales was 48.30% in self-confidence and 55.30% in anxiety, with an average of 51.80%. The agreement between the items in the resulting factor structure matrix from the EFA and the original matrix were very similar for the anxiety sub-scale (89.90%) but only moderately similar for the self-confidence sub-scale (59.30%), where items did not fall within the same dimensions.

Given the low result, a CFA was conducted based on the dimensions proposed by White (2011). The goodness-of-fit indicators of the model were: (CFI, IFI = 0.981, TLI, NNFI = 0.979, and RMSEA = 0.052) for self-confidence and (CFI, TLI, NNFI, IFI = 0.997 and RMSEA = 0.024) for anxiety. This indicates that the three-factor model retains the description with the original items.

Table 2 shows the estimated factor loadings by dimension and item, illustrating the robust composition of the dimensions with no item elimination. Although items Q5, Q27 and Q11 had factor loadings below 0.60, their KMO values were ≥ 0.80, indicating adequate sampling.

Highly significant correlations were found regarding criterion validity and relevance ( p <.001). Correlations within the dimensions within the same scale (D1, D2, D3) were positive, whereas the paired correlations between self-confidence and anxiety were inversely correlated, as increased confidence was associated with decreased anxiety: (D1 r = −.500), (D2 r = −.500) and (D3 r = −.532).

Comparative analysis of self-confidence and anxiety in decision making by academic year

The overall results for self-confidence and anxiety by academic year indicated that students significantly and gradually increased their self-confidence ( p =.049) as they progressed from the 1st year (M = 108.22, SD = 14.96) to the 4th year (M = 115.54, SD = 16.28). However, anxiety was higher in the 1st year (M = 81.71, SD = 18.90) and increased in the 3rd year (M = 86.32, SD = 26.38) (Table 3 ).

Table 4 shows statistically significant differences in dimensions D2 and D3 for self-confidence and D3 for anxiety.

Dimension D1 - using resources to collect information and listening carefully

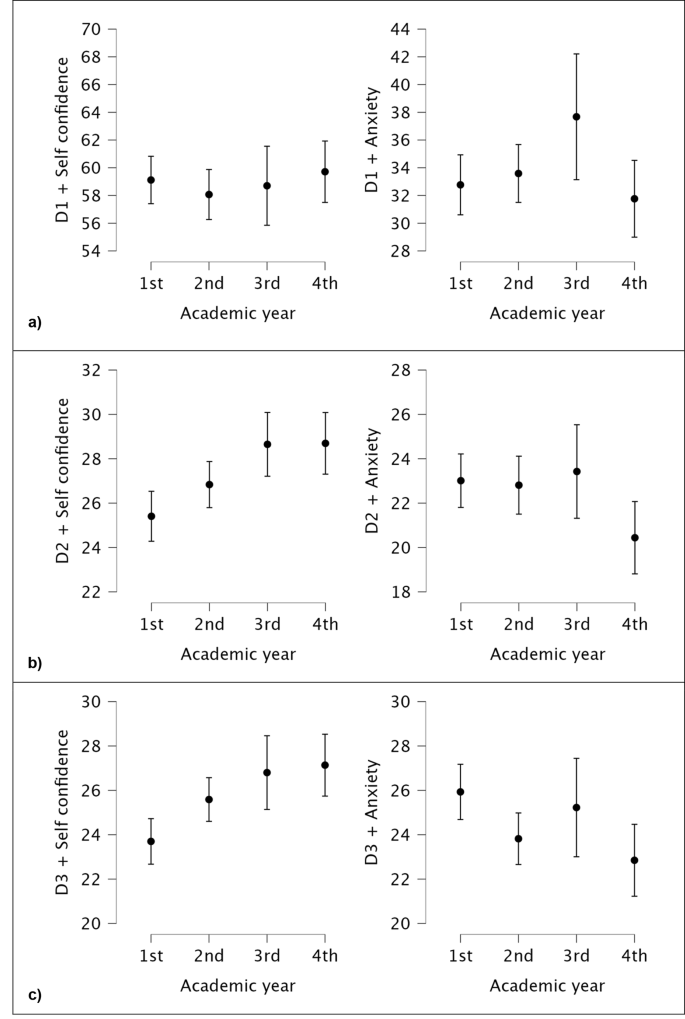

The post hoc Tukey test results indicate no statistically significant differences between academic years in dimension D1 (Table 4 ). Students in higher academic years did not obtain significantly higher self-confidence or lower anxiety scores (Fig. 1 a). The self-confidence means were similar across all 4 groups, while the anxiety mean had varying values. The highest anxiety was observed in the 3rd year (M = 37.67; SD = 14.63), and the lowest was in the 4th year (M = 31.76; SD = 10.82), although the differences were not statistically significant ( p =.178).

Comparison graphics of different dimensions of different Academic years ( a ) D1. Using resources to collect information and listening carefully: Post Hoc Comparisons Academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th) ( b ) D2. Using information to see the big picture: Post Hoc Comparisons Academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th). ( c ) D3. Knowing and acting: Post Hoc Comparisons Academic year (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th)

Dimension D2 - using information to see the big picture

Students in the higher academic years (3rd and 4th) obtained significantly higher self-confidence scores (M = 28.69; SD = 5.44) compared to the lowest, which is from the 1st year (M = 25.40; SD = 5.33) (Table 4 ; Fig. 1 b). There was a downward trend in anxiety in the later years, but it was not significant. Once again, the highest mean anxiety was observed in the 3rd year (M = 23.42; SD = 6.80) and the lowest in the 4th year (M = 20.44; DS = 6.39).

Dimension D3 - knowing and acting

This is the only dimension where a balance was maintained: self-confidence increased with academic years, while anxiety decreased. Significant differences in self-confidence scores were observed between the 1st year (M = 23.70; SD = 4.85) and the 4th year (M = 27.13; SD = 5.47). At the same time, anxiety significantly decreased between the 1st year (M = 25.93; SD = 5.90) and the 4th year (M = 22.85; SD = 6.36) (Table 4 ; Fig. 1 c).

Effect of students’ work experience on their decision-making processes

A comparative test was conducted between groups based on work experience to identify explanatory variables regarding the extent of self-confidence and anxiety (Table 5 ). Two significant differences were found, indicating that students with work experience, as opposed to students without experience, had higher self-confidence in D2 (M = 27.66, SD = 5.43 vs. M = 26.63, SD = 5.61) and D3 (M = 26.24, SD = 5.52 vs. M = 24.58, SD = 5.10). Meanwhile, the level of anxiety was similar in both groups.

Furthermore, when contrasting individual items, 7 specific items showed significant differences in self-confidence and 2 in anxiety based on students’ work experience (Table 6 ).

Two items belong to D2- Using information to see the big picture, where experienced students exhibited greater self-confidence in detecting important patient information patterns in I1 (M = 4.10 vs. M = 3.98) and experienced less anxiety (M = 2.96 vs. M = 3.30), and simultaneously evaluated their decisions better with patient laboratory results in I7 (M = 4.00 vs. M = 3.67).

The other five items correspond to D3- Knowing and acting, where nursing students with prior nursing experience felt more self-confidence when deciding the best priority alternative for the patient’s problem in I5 (M = 3.53 vs. M = 3.30), more confidence in implementing an intuition-based intervention in I14 (M = 3.95 vs. M = 3.59) with less anxiety (M = 3.38 vs. M = 3.69), more confidence in analyzing the risks associated with interventions I15 (M = 4.10 vs. M = 3.86) a better ability to make autonomous clinical decisions in I17 (M = 3.71 vs. M = 3.42), and to implement a specific intervention in an emergency in I20 (M = 3.79 vs. M = 3.47).

Given the objectives and results of this study, the discussion is subdivided into two sections: (1) Study of the Nursing Anxiety and Self-Confidence with Clinical Decision Making (NASC-CDM©) scale from English to Spanish, and (2) Assessment of self-confidence and anxiety in nursing students.

Study of the nursing anxiety and self-confidence with clinical decision making (NASC-CDM©) tool