- Previous Article

- Next Article

Russia’s native son

A corpuscular world, electricity in the air, venus’s atmosphere, a peculiar polymath.

- Box 1. The parallel lives of Lomonosov and Franklin

- Box 2. Genius, society, and time

Mikhail Lomonosov and the dawn of Russian science

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Vladimir Shiltsev; Mikhail Lomonosov and the dawn of Russian science. Physics Today 1 February 2012; 65 (2): 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.1438

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

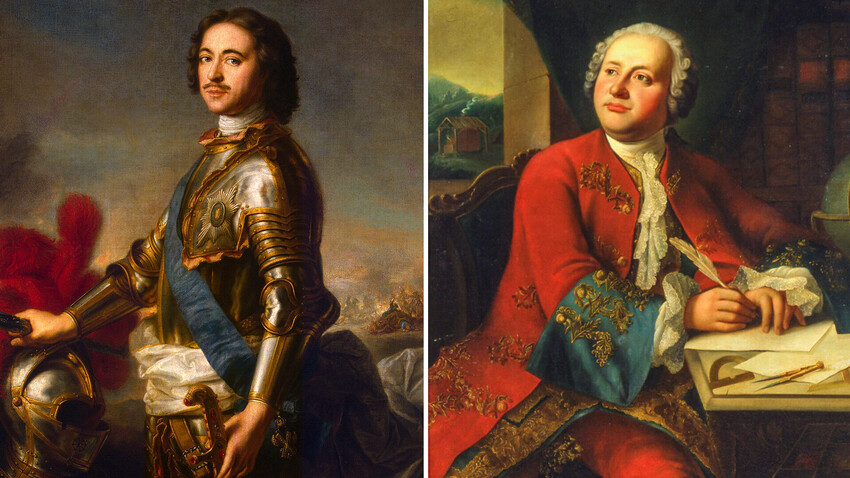

On 7 December 1730, a tall, physically fit 19-year-old, the son of a peasant-turned-fisherman, ran away from his hometown, a village near the northern Russian city of Archangel. His departure had been quietly arranged. He had borrowed three rubles and a warm jacket from a neighbor, and he carried with him his two most treasured books, Grammatica and Arithmetica . He persuaded the captain of a sleigh convoy carrying frozen fish to let him ride along to Moscow, where he was to fulfill his dream of studying “sciences.” He left behind a kind but illiterate father, a wicked and jealous stepmother, prospects of an arranged marriage into a family of means, and his would-be inheritance—a two-mast sailboat named Seagull . The young man’s name was Mikhail Vasilevich Lomonosov (figure 1 ).

![lomonosov biography in english Figure 1. Mikhail Vasilevich Lomonosov, 1711–65. (From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography [Kunstkamera], MJ1-41, Russian Academy of Sciences.)](https://aipp.silverchair-cdn.com/aipp/content_public/journal/physicstoday/65/2/10.1063_pt.3.1438/3/m_40_1_f1.jpeg?Expires=1716735902&Signature=S2GcPHDWXh~dczonrPPfITLcLCBZrFnSv8FlGcFJjx9pGS6qJJd7iBtwc92B5QXWPeyWmGX9I8y5corIBldxhUrjBAzafdgDS~sN-a8UE4GeC3~81bqjBaHvWiPRzu6h9dE~9RqkJHDTqBp-y3Z5JCB8cOdpNlSgOS5rPkKYcqYZ0XWs8BGfD0BfShLsjc7DwIrhMXBdo9h57XQRdNp98ZOEQUqsQwx~krnecQlrV3lxpYUW9cJIBIzmZAquHFjPHmuAr5j1bPO5EmclI3SD0el~s7exLHqmX1QSHtn4qHca9OzUdXXUlEU188GBftvyPQBuJ4Rtq5ugOJlwIaDmDQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Figure 1. Mikhail Vasilevich Lomonosov, 1711–65. (From the collection of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography [Kunstkamera], MJ1-41, Russian Academy of Sciences.)

He thought that ahead of him lay a month-long trek along a snowy, 800-mile route. In fact, it was the beginning of a much longer journey that would usher in the modern era of Russian science. Young Lomonosov couldn’t have known that after years of hardship and a decade of scientific training, he would become the first Russian-born member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences, a nobleman, and Russia’s most accomplished polymath. And although his name was forgotten in scientific circles for nearly 50 years, he has reemerged during the past two centuries as a cult figure in Russian science.

Lomonosov was born 19 November 1711 into a family of peasants of the state. His mother died when he was nine, and his stepmothers despised his adoration of the village’s few available books, including the Bible and Lives of the Saints , both of which he had learned to read in the village’s church. Reading, they claimed, distracted him from being a proper help to his father.

Not long after Lomonosov’s departure, his father tracked him down in Moscow at the boarding school of the Spassky Monastery, where he had been admitted under the false pretense that he was the son of a nobleman. His father asked him to come back, but the young runaway chose instead to continue his studies, even though that meant half-starving on a daily stipend of three kopeks—roughly $4 today—and being ridiculed for being considerably older than his classmates. In four years he had nearly finished an eight-year course in Latin, Greek, Church Slavonic, geography, history, and philosophy, but when his true parentage was revealed, he was threatened with expulsion. It was only by virtue of his impressive academic record that he was allowed to continue the course, and in 1736 he was transferred as one of 12 top students to continue his education at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

Lomonosov’s talents were quickly recognized at the academy as well, and in the fall of 1736, he and two other students were sent to the University of Marburg in Germany. For three years he studied natural sciences and mathematics with Christian Wolff, a renowned encyclopedic scientist, philosopher, and epigone of Gottfried Leibniz. (On his own initiative, Lomonosov also studied German, French, art, dance, and fencing.) From Wolff he acquired a logical, schematic style of scientific thought, which served him well throughout his life.

In the summer of 1739, Lomonosov and his classmates traveled to Freiberg, Germany, to study practical mining with Johann Henckel. Within a year, having acquired a great deal of knowledge about mineralogy and metallurgy, Lomonosov left Freiberg and spent a large part of 1740 chasing the Russian ambassador through Germany and Holland in search of funds to return to Russia. Later that year, in Marburg, he married Elizabeth Zilch. In 1741 Lomonosov returned to Russia and was appointed an adjunct professor of physics at the academy, an institution with which he would remain affiliated until his death on 4 April 1765.

The Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences was founded in 1724 by a decree of Emperor Peter the Great. In its early days, it consisted of a dozen or so academicians (or professors) and a similar number of adjuncts instructing in the natural sciences, rhetoric, history, and law. Fully supported by the state, the academy enjoyed auspicious beginnings; its liberal scientific environment and more-than-generous salaries resulted in the influx of the highest-caliber scholars. Daniel Bernoulli and Leonhard Euler were the most notable of the first wave of faculty members. The ultimate goals of the academy were to train Russian scientists and to establish the country’s science and education. In its infancy, however, the academy was dominated by foreign-born scientists and, due to continual budget issues, limited in its educational activities.

By the time of Lomonosov’s arrival, the academy was in a state of crisis due to financial problems, bureaucratic infighting, and the departure of Euler, Bernoulli, Joseph Nicholas Delisle, and other luminaries. The task of educating Russian students had been mostly neglected, and by the end of its second decade, the academy had only three Russian adjuncts. Lomonosov, elected an academician in 1745 and later appointed to the academy’s triumvirate chancellery, fought hard to improve the situation. He succeeded in increasing the number of scientific publications and lectures in Russian, as opposed to Latin or German; recruiting more Russian interns and students to the academy’s gymnasium; and by 1765 bringing the number of Russian-born faculty up to 10, including 7 academicians.

As a scientist, Lomonosov was equal parts thinker and experimenter. He tested his theories and hypotheses with experiments that he planned and carried out himself. Although proficient in math, he never used differential calculus. He would work on research topics for years, even decades at a time, always with an eye toward turning discoveries into new practices or inventions.

Lomonosov believed physical and chemical phenomena were best explained in terms of the mechanical interactions of corpuscles—“minute, insensible particles” analogous to what we now know as molecules. 1 Giving name to the philosophy, he coined the term “physical chemistry” in 1752.

He is perhaps best known for being the first person to experimentally confirm the law of conservation of matter. That metals gain weight when heated—now a well-known consequence of oxidation—confounded British chemist Robert Boyle, who had famously observed the effect in 1673. The result seemed to implicate that heat itself was a kind of matter. In 1756 Lomonosov disproved that notion by demonstrating that when lead plates are heated inside an airtight vessel, the collective weight of the vessel and its contents stays constant. In a subsequent letter to Euler, he framed the result in terms of a broad philosophy of conservation:

All changes that we encounter in nature proceed so that . . . however much matter is added to any body, as much is taken away from another . . . since this is the general law of nature, it is also found in the rules of motion: a body loses as much motion as it gives to another body.

In analogous experiments 17 years later, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier progressed further, showing that the increase in the weight of the metal is exactly offset by a reduction in the weight of the air’s oxygen. But contrary to Lavoisier, who considered heat to be a “subtle caloric liquid,” Lomonosov understood it more accurately as a measure of the linear and rotational motion of corpuscles. In 1745, more than a century before Lord Kelvin introduced the absolute temperature scale, Lomonosov proposed the concept of absolute cold as the point at which corpuscles neither move nor rotate.

The corpuscular framework also led the Russian scientist to correctly predict a deviation from Boyle’s law: Because the particles themselves occupy a certain volume of space, argued Lomonosov, the air pressure wouldn’t remain inversely proportional to the gas volume at high pressures. Lomonosov’s deductions presaged molecular kinetic theory, which wouldn’t be fully developed until the 19th century. 2,3

Lomonosov began studying electricity with Georg Wilhelm Richmann in late 1744. Together, they pioneered a quantitative approach: Lomonosov had proposed a technique that called for measuring an object’s charge based on the electrostatic forces it exerts on a metal scale; Richmann’s simpler but more effective invention, a silk thread connected to a vertical metal rod, might be considered the first electrometer. The angle of the thread’s tilt gave a measure of the rod’s charge.

In 1753 their progress in understanding atmospheric electricity suffered a tragic interruption. While performing an experiment in a heavy thunderstorm, Richmann was killed by ball lightning. Lomonosov, who had been simultaneously performing a nearly identical experiment just three blocks away, reported having “miraculously survived” thanks to being momentarily distracted by his wife.

To prevent the impending cessation of the academy’s atmospheric-electricity studies and to eulogize his friend, Lomonosov wrote A Word on Atmospheric Phenomena Proceeding from Electrical Force . In it, he theorized that lightning was electricity generated by friction between warm, upward-flowing air and cool, downward-flowing air, with the electric charge accumulating on “oily” microparticles (see figure 2 ). He described the vertical drafts as resulting from air-density gradients, which he could estimate based on temperature and pressure profiles. All of that marked an advance beyond Benjamin Franklin’s earlier discovery of the connection between lightning and electricity. (See box 1 for a comparison of the two men’s lives.)

Figure 2. Circulating atmospheric flows like the ones depicted in this 1753 sketch were speculated by Mikhail Lomonosov to be the root cause of lightning. He conjectured that friction between warm updrafts and cool downdrafts caused charge to accumulate on microscopic atmospheric particles. (Adapted from ref. 6 .)

Looking to loft meteorological instruments and electrometers into the air, Lomonosov designed and built the contraption shown in figure 3 . A forerunner to the helicopter, it boasted two propellers—powered by a clock spring—that rotated in opposite directions to balance out torque. During its demonstration to the academy in July 1754, the model managed to lift itself slightly, but no practical device emerged.

Figure 3. A modern-day reconstruction of Mikhail Lomonosov’s “aerodynamic machine,” which he had hoped to use to loft meteorological instruments into the sky. In a 1754 demonstration, Lomonosov’s contraption mustered a lift force of about 0.1 N but never made it far off the ground.

In 1756 Lomonosov compiled 127 notes on the theory of light and electricity, presented a mathematical theory of electricity, and in a public meeting of the academy read his paper on the wave nature of light and on a new theory of the colors that constitute light.

The transit of Venus across the Sun’s disk on 6 June 1761 afforded a rare opportunity to measure the Earth-to-Sun distance using Edmond Halley’s method, which calls for comparing various apparent paths of the transit as measured from different Earth latitudes. As a leader of the academy, Lomonosov helped to organize a worldwide observation effort that included more than 170 astronomers dispatched to 117 stations, 4 of which were in Russia. He was alone, however, in having realized that a dense Venusian atmosphere, if one existed, would bend the Sun’s rays to produce a visible aureole, or ring of light, during the very beginning and very end—the ingress and egress—of the transit. Expecting the aureole to be faint, he viewed the ingress and egress using only a weak optical filter; to mitigate the considerable risk of damage to his vision, he observed the process in brief glimpses and only with well-rested eyes.

To his excitement, he observed an arc of light lining Venus’s shadow at the end of ingress and at the beginning of egress. Later, several other astronomers confirmed seeing the arc, but only Lomonosov recognized its significance. Within a month he published a report summarizing the observations and explaining how the atmosphere refracts light to produce the aureole, or “bulge,” as he called it (see figure 4 ). He proclaimed that “Venus is surrounded by a distinguished air atmosphere, similar (or even possibly larger) than the one around Earth.” 4

Figure 4. Venus’s halo. (a) Mikhail Lomonosov’s report on the 1761 solar transit of Venus contained sketches depicting an aureole, or bulge of light, that appeared as Venus’s silhouette crossed the edge of the Sun’s disk during the beginning and end of the transit. Lomonosov touted the aureole as evidence of Venus’s atmosphere. (b) Modern-day telescope images show the aureole appearing during the early stages of Venus’s 2004 transit across the Sun.

In an addendum, Lomonosov suggested that there might be life on Venus—a possibility that he argued wasn’t necessarily at odds with the Bible. Moreover, he contended Venusians might not necessarily be Christians. It was a bold stance to take in 18th-century Russia, where just 20 years earlier the Holy Synod had gone out of its way to denounce as heresy the heliocentric Copernican model of the universe.

The academy quickly published 200 copies of Lomonosov’s report in German and sent them abroad in August 1761. Inexplicably, they went virtually unnoticed in Europe. Other astronomers, including American David Rittenhouse, made similar observations of the aureole during the 1769 transit. But for nearly two centuries, the discovery of Venus’s atmosphere was credited to German-born astronomers Johann Schröter and William Herschel, who—unaware of their predecessors’ work—observed a different effect related to Venus’s atmosphere in 1790. Lomonosov’s priority wasn’t widely acknowledged until the mid 20th century.

Similarly overlooked was Lomonosov’s 1756 invention of a single-mirror reflecting telescope. Isaac Newton’s reflecting telescope, invented a century prior, consisted of two mirrors: a curved primary one and a small, diagonally oriented secondary one that reflected the primary image into a viewing piece. But given the low reflectivity of the brass mirrors of the day, the two-mirror scheme presented a substantial cost to brightness. Lomonosov obviated the secondary mirror by tilting the primary mirror 4° so that it formed an image directly in a side eyepiece. In 1789, however, Herschel used a similar approach to build what was then the world’s largest telescope, and what might have been appropriately known as a Lomonosov–Herschelian telescope is now named solely for Herschel.

Another of Lomonosov’s inventions, the so-called night-vision tube, sparked so much controversy that his colleagues at the academy rushed to publish theoretical tracts proving its implausibility. Demonstrated in 1756 and used during the Russian navy’s Arctic expeditions of 1765 and 1766, the simple telescope had just two lenses—to minimize optical loss—and a large objective aperture. Crucially, the short-focus lens at the eyepiece had a larger-than-usual diameter of about 8 mm, roughly the size of a fully dilated human pupil. 5

His colleagues saw no novelty in the design. At first glance, Lomonosov’s tube looked no different from the familiar Keplerian telescope, and it was well known that brightness can’t be increased by magnification. Lomonosov, however, argued that the device’s increased optical flux actually had allowed him to see better in the dark. He invited his critics to test the apparatus for themselves, but they remained unconvinced. The controversy survived until 1877, when Ricco’s law established that the minimum brightness detectable by a human eye is inversely proportional to the area of the image formed on the retina. Lomonosov was vindicated, and nowadays anyone can see the effect even with ordinary large-aperture binoculars.

During the severe winter of 1759, Lomonosov and colleague Joseph Adam Braun used a mixture of snow and nitric acid to chill a thermometer to −38 °C and obtain—for the first time on record—solid mercury. Upon hammering the frozen metal ball, they found it to be elastic and hard “like a lead.” Mercury, shrouded in mystique at the time, was shown to be not all that dissimilar to the more common metals. It was among the most widely discussed discoveries in Europe.

A firm, lifelong believer in corpuscular mechanics, Lomonosov was suspicious of Newton’s gravity and its action at a distance. The Russian spent the last five years of his life carrying out pendulum experiments in a futile attempt to overthrow it; his efforts were documented in hundreds of pages of logbook notes.

At more than six feet four inches tall and physically strong, Lomonosov reminded many of his idol, Peter the Great. Anecdotes of the scientist’s exploits depict a daring existence. He and two other Russian interns are said to have so out-reveled German students in Marburg that the city sighed with relief when the trio left for Freiberg. German hussars once got him drunk and enlisted in the Prussian army, which he later escaped. And as a 50-year-old academician, he once fought off three unlucky sailors attempting to rob him; he beat the men and stripped them of their clothes.

Lomonosov was also known to argue fiercely with inept colleagues at the academy. For one quarrel that ended in physical violence, he paid dearly. Then just an adjunct, his salary was halved, he was placed under house arrest for eight months—one of the most scientifically productive periods of his life, he later noted—and he was freed only after a public apology. Lomonosov’s hot temper and rebellious character were integral to his rise as a legendary figure, as were his immense self-esteem and dignity, rare traits in imperial Russia.

He once admonished his patron, Count Ivan Shuvalov, saying, “Not only do I not wish to be a court fool at the table of lords and such earthy rulers, but even of the Lord God himself, who gave me my wit until he sees fit to take it away.” Had it been said to a less-enlightened count, such a statement might have been met with severe repercussions. Shuvalov, however, remained a lifelong friend. It was he who embraced Lomonosov’s charter of the first Russian university and who convinced Empress Elizabeth to sign a decree establishing Moscow University on 25 January 1755, a day still celebrated annually in Russia as Students’ Day. The university offered education to a wide stratum of Russian society and was key to the country’s intellectual progress. In 1940 it was named after Lomonosov.

Originally, Lomonosov was recognized mainly as a historian, reformer of Russian grammar, rhetorician, and poet. His eulogistic odes to empresses were well accepted at the court. One of them earned him 2000 rubles, three times his annual academic salary at the time. For almost a century, Lomonosov’s poetry overshadowed his natural philosophy—not only abroad, where his science often failed to make an impact, but even in Russia.

As Lomonosov himself used to say, however, “Poetry is my solace; physics, my profession.” With a 1500-ruble grant from the Russian senate, he set up Russia’s first research chemical laboratory, which he led for eight years. He also won a 4000-ruble grant to start a mosaic factory and, subsequently, an 80 000–ruble commission (roughly $12 million today) to create 17 mosaics celebrating the deeds of Peter the Great. Only one was finished before he died—the grandiose Battle of Poltava , now displayed in the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Only in the mid 19th century did his scientific accomplishments begin to be fully appreciated in Russia and abroad. Through the works of Boris Menshutkin, 2 Nikolai Vavilov, 6 Nobel laureate Peter Kapitza, 7 and many others, Lomonosov has reemerged as the most renowned figure in Russian science (see box 2 ). Among his namesakes are a city, an Arctic ridge, lunar and Martian craters, a porcelain factory, and a mineral.

The complete works 6 of Lomonosov consist of four volumes on physics, chemistry, and astronomy; two on mineralogy, metallurgy, geology, Russian history, economics, and geography; two on philology, poetry, and prose; and three of correspondence, letters, and translations. Lomonosov’s tercentennial in 2011 was celebrated statewide by a decree of the Russian president.

How could such an accomplished figure remain so obscure for so long? Kapitza pointed to Russia’s relatively primitive scientific society, in which few people could appreciate Lomonosov’s genius, and to Lomonosov’s weak personal connections with most influential European scientists. Lomonosov never left Russia after he was a student, and he had a sustained exchange of ideas only with Euler, who was in Berlin at the time. 7 Robert Crease adds that polymaths tend to be underappreciated due to their breadth, a shortcoming in the eyes of the public, and that Lomonosov in particular was rarely written about in English. 8 Also, Lomonosov lived a relatively short life; he died at age 53, while many of his contemporaries, including Newton, Bernoulli, Franklin, and Herschel, lived to see 70, 80, or more. Moreover, he chose to divert much of his energy into promoting Russia’s science and education and modernizing its industry and military.

Another factor bears consideration: Lomonosov’s natural philosophy was based on Cartesian explanations of mechanical models, whereas his European counterparts at the time were increasingly turning to Newtonian-inspired reasoning that relied on caloric, electric, and other “imponderable fluids.” (Euler was an exception.) Only 19th-century physics, buttressed by the mechanical theory of heat and wave optics, provided the requisite background to appreciate Lomonosov’s discoveries and ideas.

Mikhail Lomonosov is often compared with his American contemporary Benjamin Franklin; both are considered scientific patriarchs and key figures of the enlightenments of their respective homelands. They each lived in the epoch of their nations’ emergence into Western civilization—Russia through wars and reforms initiated by Peter the Great, the American states through prerevolutionary developments and the War of Independence.

The biographical similarities between the two scientists are striking: Both devoted their lives to scientific observation and experiment, both made major discoveries regarding electricity and lightning, and both were deeply interested in public education. Lomonosov founded Russia’s first university and played a leading role in the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences; Franklin was the founder and first president of the American Philosophical Society. Both men tried to reform their languages’ grammars; Lomonosov succeeded, Franklin did not. And both were interested in geography: Lomonosov worked on finding an Arctic path to America; Franklin discovered the Atlantic Ocean’s Gulf Stream.

Lomonosov and Franklin are widely regarded as self-made men. Born into working-class families, both fled restrictive environments—and told lies as needed—in pursuit of opportunity. Both married their landladies’ daughters, unsophisticated women who did not share their husbands’ interests. Both were accomplished polymaths who rose to prestigious national rank, shaped their countries’ scientific cultures, and left enduring legacies. The religious views of Lomonosov, an enlightened Russian Orthodox who regarded God as a “wise clock-master,” were close to those of Franklin, a well-known deist.

Although they never met, the two men knew of each other, and each held the other’s scientific reputation in high regard. Lomonosov laboriously explained to his contemporaries the difference between his theory of atmospheric electricity and that of the “celebrated master Franklin.” Franklin advised Ezra Stiles, an amateur scientist and cofounder of Brown University, on how to best communicate with Lomonosov about temperature regimes in the Arctic Sea.

Franklin, however, enjoyed the advantages of being an Englishman (until 1776!) and a citizen of Philadelphia, perhaps the most liberal city in the world at the time. He flourished in a society that asserted, as a matter of principle, every man’s right to self-realization. Lomonosov, by contrast, lived in the backward society that defined Russia after Peter the Great. As one important Russian scholar put it, “Russia could not have produced a Franklin. But what an opportunity Lomonosov would have had, if he had been born in America!” 9

The chart shown here illustrates the evolving popularities of Gottfried Leibniz, Isaac Newton, and Mikhail Lomonosov—the three key figures of the national enlightenments of Germany, England, and Russia, respectively. The plot shows the frequency of appearances of each man’s last name as a fraction of the sum total of words published in his native language in a given year. By that metric, the three men are the most frequently recurring names among representatives of the natural sciences, and the chart illustrates their unique paths to fame.

Newton (1642–1727) enjoyed enormous recognition during his lifetime, a peak in celebrity during the decade right after his death, and then centuries of posthumous recognition. Leibniz (1646–1716) rose to fame in more dramatic fashion. Presumably due to having lost the argument with Newton over priority in developing differential calculus, Leibniz went unrecognized for almost 150 years after his death. Not until the second half of the 19th century, when a unified German state was created, did he gain fame. Since then, Leibniz’s prominence in the literature of his native tongue is unrivaled by any other scientist, likely owing to consistent scientific awareness on the part of German society.

Lomonosov (1711–65) rose to prominence via an equally remarkable path. He was posthumously forgotten in the Russian literature for some 40 years but then reemerged in the early 1800s during Russia’s cultural awakening, of which the appearance of renowned author Alexander Pushkin was the climax. Since then, Lomonosov has consistently been the most frequently mentioned scientist in the Russian literature, followed by Dmitri Mendeleyev, creator of the periodic table, and Nobel laureate Ivan Pavlov, pioneer in understanding physiological reflex mechanisms.

Lomonosov’s peaks in popularity during the 1860s and 1950s correspond to publicity campaigns—the most recent initiated by Joseph Stalin to popularize science and technology and to venerate Russia’s scientific heritage. Notably, those brief surges did not change the baseline level of Lomonosov’s popularity. The true value of a person in a nation’s eyes, it would seem, holds steady through the decades and centuries. (Chart produced using Google’s Ngram Viewer. See ref. 10 .)

This article is an edited version of a talk given at Fermilab in November 2011 on the occasion of Mikhail Lomonosov’s tercentennial anniversary.

Vladimir Shiltsev is director of the Accelerator Physics Center at Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois.

Citing articles via

- Online ISSN 1945-0699

- Print ISSN 0031-9228

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

- Quick Facts

- Sights & Attractions

- Tsarskoe Selo

- Oranienbaum

- Foreign St. Petersburg

- Restaurants & Bars

- Accommodation Guide

- St. Petersburg Hotels

- Serviced Apartments

- Bed and Breakfasts

- Private & Group Transfers

- Airport Transfers

- Concierge Service

- Russian Visa Guide

- Request Visa Support

- Walking Tours

- River Entertainment

- Public Transportation

- Travel Cards

- Essential Shopping Selection

- Business Directory

- Photo Gallery

- Video Gallery

- 360° Panoramas

- Moscow Hotels

- Moscow.Info

- History of St. Petersburg

- Petersburgers

- Scientists and inventors

Mikhail Lomonosov

Born: Denisovka, Archangelsk Province - 19 November 1711 Died: St. Petersburg - 15 April 1765

Mikhail Lomonosov was the great polymath of the Russian Enlightenment. Born in the deepest provinces of Northern Russia, he managed to gain a first-class education through a combination of natural intelligence and sheer force of will, and went on to make significant advances in several fields of science, as well as writing one of the first Russian grammars, several volumes of history, and a great quantity of poetry. In short, he was instrumental in pulling Russia further into the modern world, and in helping to make St. Petersburg a centre of learning as great as almost any in Europe.

Lomonosov was born in the village of Denisovka (now Lomonosovo), a village about 100 kilometers south-east of Arkhangelsk on the Severnaya Dvina river. His father was a peasant fisherman who had grown rich transporting goods from Arkhangelsk to settlements in the far north. His mother, the daughter of a deacon, died when he was very young, but not before she had taught him to read. From the age of ten, he accompanied his father on voyages to learn the business.

In 1730, however, determined to study, he ran away from home and walked over 1 000 kilometers to Moscow. Claiming to be the son of a provincial priest, he was able to enroll in the Slavic Greek Latin Academy, where he studied for five years before being sent on to St. Petersburg's Academic University. The following year (1736), he was a select group of outstanding students sponsored by the Academy of Sciences to study mathematics, chemistry, physics, philosophy and metallurgy in Western Europe. Lomonosov spent three years at the University of Marburg as a personal student of the philosopher Christian Wolff, then a year studying mining and metallurgy in Saxony, and a further year travelling in Germany and the Low Countries. While in Marburg, he fell in love with and married his landlady's daughter, Elizabeth Christine Zilch.

Due to lack of funds to support his young family, Lomonosov returned to St. Petersburg at the end of 1741, and was immediately appointed adjunct to the physics class at the Academy of Sciences. In 1745 he became the Academy's first Russian-born Professor of Chemistry, and in 1748 the first chemical research laboratory in Russia was built for him.

Throughout his career at the Academy, Lomonosov was a passionate advocate for making education in Russia more accessible to the lower ranks of Russian society. He campaigned to give public lectures in Russian and for the translation into Russian of more scientific texts. In this, he found himself in conflict with one of the founders of the Academy, the German ethnologist Gerhard Friedrich Miller (whose views on the importance of Scandinavians and Germans in Russian history Lomonosov also hotly disputed). By composing and presenting at an official Assembly of the Academy in 1749 his ode to the Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, Lomonosov gained considerable favour at court and a powerful ally in his pedagogical endeavours in the form of Elizaveta's lover, Count Ivan Shuvalov. Together, Lomonosov and Shuvalov founded Moscow University in 1755. It was also thanks to Shuvalov's influence that the Empress granted Lomonosov a manor and four surrounding villages at Ust-Ruditsa, where he was able to implement his plan to open a mosaic and glass factory, the first outside Italy to produce stained glass mosaics.

By 1758, Lomonosov's responsibilities included overseeing the Academy's Geography Department, Historical Assembly, University and Gymnasium, the latter of which he again insisted on making open to lowborn Russians. In 1760, he was appointed a foreign member of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, and in 1764 he was similarly honoured by the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna. The same year, he was granted by Elizaveta Petrovna the rank of Secretary of State. He died 4 April 1765, and was buried in the Lazarev Cemetery of St. Petersburg's Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

Much of Lomonosov's work was unknown outside Russia until many years after his death, and even now it is more the extraordinary breadth of his inquiry and understanding, rather than any specific grand advancements in a particular field, that make him such a seminal figure in Russian science. Among the highlights of his academic career were his discovery of an atmosphere around Venus, his assertion of the Law of Conservation of Mass (nearly two decades before Antoine Lavoisier), and his development of a prototype of the Herschelian telescope. In 1764, he arranged the expedition along the northern coast of Siberia that discovered the Northeast Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. His works also contained intuitions of the wave theory of light and the theory of continental drift. He made improvements to navigational instruments and demonstrated the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber. Without knowledge of Da Vinci's work, he developed a working prototype of a helicopter.

He wrote the first guide to rhetoric in the Russian language, and his Russian Grammar was among the first to codify the language. His Ancient Russian History compared the development of Russia to the development of the Roman Empire, a theme that would become increasingly popular in the 19th century. His poetry was much praised during his lifetime, although it has been largely ignored by posterity.

Lomonosov is remembered in central St. Petersburg in the names of Ulitsa Lomonosova ("Lomonosov Street"), Ploshchad Lomonosova ("Lomonosov Square") and the adjacent bridge across the Fontanka River. During the Soviet Period, his name was given to the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory, and hence to the nearby metro station, Lomonosovskaya. The Soviets also renamed the suburban town of Oranienburg as Lomonosovo. In 1986, a magnificent monument to Lomonosov was unveiled in front of the Twelve Colleges, the main campus of St. Petersburg State University, acknowledging the enormous debt that institution owes the great polymath who is rightfully considered the father of Russian science.

We can help you make the right choice from hundreds of St. Petersburg hotels and hostels.

Live like a local in self-catering apartments at convenient locations in St. Petersburg.

Comprehensive solutions for those who relocate to St. Petersburg to live, work or study.

Maximize your time in St. Petersburg with tours expertly tailored to your interests.

Get around in comfort with a chauffeured car or van to suit your budget and requirements.

Book a comfortable, well-maintained bus or a van with professional driver for your group.

Navigate St. Petersburg’s dining scene and find restaurants to remember.

Need tickets for the Mariinsky, the Hermitage, a football game or any event? We can help.

Get our help and advice choosing services and options to plan a prefect train journey.

Let our meeting and events experts help you organize a superb event in St. Petersburg.

We can find you a suitable interpreter for your negotiations, research or other needs.

Get translations for all purposes from recommended professional translators.

Pomor Polymath: The Upbringing of Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, 1711–1730

- Published: 26 November 2013

- Volume 15 , pages 391–414, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Robert P. Crease 1 &

- Vladimir Shiltsev 2

311 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The life story of Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (1711–1765) opens a window onto Russian science, politics, language, and social advancement in the era of Peter the Great (1672–1725). We cover Lomonosov’s background and upbringing, from his birth in 1711 near Kholmogory until his departure for Moscow on foot in 1730. The special character of the Pomor region, in Russia’s north, where Lomonosov was born and raised, is important for understanding his character, upbringing, and subsequent career trajectory. This character sprang from four overlapping factors: the isolation of the region, the political and religious tolerance that mainly prevailed there, the trade that brought the region into contact with foreigners, and the hardy lifestyle.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Bulgakov, Moscow, and The Master and Margarita

A Patriarch’s Progress: The Great Church under Grigórios VI

The principal English-language sources are Alexander Smith, “An Early Physical Chemist – M.W.Lomonossoff,” The Journal of the American Chemical Society 34 (February 1912), 109–119; Boris N. Menshutkin, Russia’s Lomonosov: Chemist, Courtier, Physicist, Poet (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952); B.B. Kudryavtsev, The Life and Work of Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954); W. Chapin Huntington, “Michael Lomonosov and Benjamin Franklin: Two Self-Made Men of the Eighteenth Century,” Russian Review 18 (4) (October 1959), 294–306; Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov on the Corpuscular Theory . Translated with an Introduction by Henry M. Leicester (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970); B.M. Kedrov, “Lomonosov, Mikhail Vasilievich,” in Charles Coulston Gillispie, Editor in Chief, Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. VIII (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973), pp. 467–472; G.E. Pavlova and A.S. Fedorov, Mikhail Vasilievich Lomonosov:His Life and Work (Moscow: Mir Publishers, 1984); Ilia Z. Serman, Mikhail Lomonosov: Life and Poetry. Translated by Stephany Hoffman (Jerusalem: The Centre of Slavic and Russian Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1988); Loren R. Graham, “Lomonosov, Mikhail Vasilievich,” in J.L. Heilbron, ed., The Oxford Guide to the History of Physics and Astronomy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 195–196; Sergei Maslikov, “Lomonosov, Mikhail Vasilievich,” in Thomas Hockey, Editor-in-Chief, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers . Vol. 1 (New York: Springer Science + Business Media, 2007), pp. 705–706; Vladimir Shiltsev, “Mikhail Lomonosov and the dawn of Russian science,” Physics Today 65 (February 2012), 40–46; Steven Usitalo, The Invention of Mikhail Lomonosov: A Russian National Myth [ Imperial Encounters in Russian History ] Brighton, Mass.: Academic Studies Press, 2013), website http://voicerussia.com/radio_broadcast/58461471/98645162/ .

See for instance Steven A. Usitalo, “Russia’s ‘First’ Scientist: The (Self-)Fashioning of Mikhail Lomonosov,” in Steven A. Usitalo and William Benton Whisenhunt, ed., Russian and Soviet History: From the Time of Troubles to the Collapse of the Soviet Union (Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), pp. 51–65.

Yaroslav E. Vodarsky, Naselenie Rossii v kontse XVII - nachale XVIII veka [ Population of Russia at the end of XVII - early XVIII centuries ] (Moscow: Nauka, 1977), pp. 153–163.

Google Scholar

V.V. Lisnichenko and N.B. Lisnichenko, Pomorskaya Mosaika [ Pomor’s Mosaics ] (Arkhangelsk: Pravda Severa, 2009), pp. 49–52.

M.I. Sukhomlinov, “K biografii Lomonosova” [“On Lomonosov’s biography”], in Izvestiya Otdeleniya russkogo yazika i slovesnosti Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk [ Proceedings of Russian language and literature department of Imperial Academy of Sciences ]. Vol. I. Book 4 (St. Petersburg: Academy of Sciences, 1896) pp. 779–791.

Alexandr I. Andreev, “O date rozhdeniya Lomonosova” [“On the date of birth of Lomonosov”], in Lomonosov: Sbornik statei i materialov [ Lomonosov: Collection of articles and materials ]. Vol. 3 (Moskow and Leningrad: Nauka, 1951), pp. 364–369.

Mikhail Verevkin, ( Akademicheskaya Biografiya ) “Zhizn pokoinogo Mikhailia Vasilievicha Lomonosova” [( Academic Biography ) “The life of the late Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov”], in Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii Mikhaila Vasilievicha Lomonosova s priobscheniem zhizni sochinitelya i s pribavleniem mnogih ego nigde esche ne napechatannih tvorenii [ Complete Works of Mikhail Lomonosov, with biography and with the addition of many not yet published works ] (St. Petersburg: Academy of Sciences, 1784), pp. III-XVIII.

“Cherti i Anekdoti dlya biografii Lomonosova, vzyatie s ego sobstvennih slov Stelinim 1783” [“Features and Anecdotes for Lomonosov’s biography, recorded from his own words by Shtehlin 1783”], in A. Kunik, Sbornik materialov dlya Istorii Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk v XVIII veke [ Collection of materials for the History of the Imperial Academy of Sciences ]. Vol. 2 (St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1865), pp. 390–405; Valery Shubinsky, Lomonosov: Vserossiiskii chelovek [ Lomonosov: An All - Russian Man ] ( Zhizn zamechatelnih lyudei [ Great People Series ] (Moscow: Molodyaya Gvardiya, 2010), pp. 8–51.

[François Marie Arouet de] Voltaire, Histoire de l’Empire de Russie sous Pierre le Grand . Tome Premier ([Genève: sine nomine ], 1759), p. 16.

Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii (PSS) [ Complete Works ] : Mikhail Vasilievich Lomonosov. 11 Vols. Edited by S. Vavilov and T. Kravets (Moscow and Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences, 1950–1983); available online from Russian National Fundamental Electronic Library, Russian Literature and Folklore – Lomonosov ; website http://feb-web.ru/feb/lomonos/default.asp , Vol. 6 (1952), p. 359.

Ibid. , Vol. 8 (1959), p. 696. For a somewhat different translation, see Serman, Mikhail Lomonosov: Life and Poetry (ref. 1), p. 9.

Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva M.V.Lomonosova [ Chronicles of the life and works of M.V. Lomonosov ], compiled by V.L. Chenakal, G.A. Andreeva, G.E. Pavlova, and N.V. Sokolova, edited by A.V. Topchiev, N.A. Figurovskiy, and V.L.Chenakal (Moscow and Leningrad, USSR Academy of Sciences, 1961), p. 20.

Jacob von Staehlin, “Cherty i Anekdoti dlya biografii Lomonosova, vzyatie s ego sobstvennih slov Stelinim 1783” [“Features and anecdotes for Lomonosov’s biography, recorded from his own words by Shtaehlin 1783”], in Arist Kunik, Sbornik materialov dlya Istorii Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk v XVIII veke [ Collection of materials for the history of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in the XVIII century ]. Vol. 2 (St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1865), pp. 390–405.

Verevkin, ( Akademicheskaya Biografiya ) (ref. 7), pp. III-XVIII.

Ibid. , p. V.

Peter von Havens M.Ph., Reise in Russland . Aus dem Dänischen ins Deutsche übersetzt von H.A.R. (Copenhagen: Gabriel Christian Rothe, 1744), pp. 108–109.

Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii (PSS): [ Complete Works ] (ref. 10). Vol. 10 (1957), pp. 481–482.

Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva M.V.Lomonosova [ Chronicles of the life and works of M.V. Lomonosov ] (ref. 12).

Ibid ., p. 21.

Ibid ., p. 22.

Petr Pekarskii [Pekarsky], “Istoriya Imperatorskoi Akademii Nauk” [“History of the Imperial Academy of Sciences”], St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences Vol. 2 (1870–1873), pp. 278–279.

Letopis’ zhizni i tvorchestva M.V.Lomonosova [ Chronicles of the life and works of M.V. Lomonosov ] (ref. 12), p. 23.

Neither the Academy biography of Lomonosov by Staehlin at the end of the 18 th century (ref. 13), nor the 19th-century biographies by Pekarsky (ref. 21), Pert S. Bilarsky, Materiali k biografii Lomonosova [ Materials for the biography of Lomonosov ] (St. Petersburg: Academy of Sciences, 1865) and Alexandr I. Lvovich-Kostritsa, Lomonosov (St. Petersburg: Ehrlich Publishing, 1892), nor the early 20 th -century biography by Boris Menshutkin, Mikhailo Vasilievich Lomonosov: zhizneopisnie [ Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov: biography ] (St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy Sciences, 1912), mention this rumor.

The original 1932 publication in the weekly Soversky Rybak [ Soviet Fisherman ] was not available to us; the story is reproduced in many publications, including N. Nepomnyaschii, 100 Zagadok Rossiiskoi Istorii [ 100 Mysteries of Russian History ] (Moscow: Veche, 2012).

Usitalo, “Russia’s ‘First’ Scientist” (ref. 2), pp. 58–59.

See, for instance, Julia Thomas, Shakespeare’s Shrine: The Bard’s Birthplace and the Invention of Stratford - upon Avon (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), and Claudia L. Johnson, Jane Austen’s Cults and Cultures (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Usitalo, “Russia’s ‘First’ Scientist” (ref. 2), p. 53.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Gary Marker for commenting on an early version of our manuscript, Marat Eseev for warm hospitality during our trip to Arkhangelsk in summer 2012, and Roger H. Stuewer for his excellent editorial work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 11794, USA

Robert P. Crease

Accelerator Physics Center, Fermilab, P.O. Box 500, Batavia, IL, 60510-5011, USA

Vladimir Shiltsev

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert P. Crease .

Additional information

Robert P. Crease (corresponding author) is Professor of Philosophy at Stony Brook University. Vladimir Shiltsev is Director of the Accelerator Physics Center at Fermilab.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Crease, R.P., Shiltsev, V. Pomor Polymath: The Upbringing of Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, 1711–1730. Phys. Perspect. 15 , 391–414 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00016-013-0113-5

Download citation

Published : 26 November 2013

Issue Date : December 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00016-013-0113-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov

- Peter the Great

- Leonty Philipovich Magnitsky

- Meletius Smotritsky

- Pomor region

- Kurostrov Island

- Solovetsky Monastery

- St. Petersburg

- Academy of Sciences

- science in Russia

- scientific mythology

- history of physics

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Español NEW

Early life and family

Education abroad, return to russia, chemistry and geology, grammarian, poet, historian.

Lomonosov was born in the village of Mishaninskaya (later renamed Lomonosovo in his honor) in Archangelgorod Governorate, on an island not far from Kholmogory, in the far north of Russia. His father, Vasily Dorofeyevich Lomonosov, was a prosperous peasant fisherman turned ship owner, who amassed a small fortune transporting goods from Arkhangelsk to Pustozyorsk, Solovki, Kola, and Lapland . Lomonosov's mother was Vasily's first wife, a deacon 's daughter, Elena Ivanovna Sivkova.

He remained at Denisovka until he was ten, when his father decided that he was old enough to participate in his business ventures, and Lomonosov began accompanying Vasily on trading missions.

Learning was young Lomonosov's passion, however, not business. The boy's thirst for knowledge was insatiable. Lomonosov had been taught to read as a boy by his neighbor Ivan Shubny, and he spent every spare moment with his books. He continued his studies with the village deacon, S.N. Sabelnikov, but for many years the only books he had access to were religious texts. When he was fourteen, Lomonosov was given copies of Meletius Smotrytsky's Modern Church Slavonic (a grammar book) and Leonty Magnitsky's Arithmetic . Lomonosov was a Russian orthodox all his life, but had close encounters with Old Believers schism in early youth and later in life he became a deist .

In 1724, his father married for the third and final time. Lomonosov and his stepmother Irina had an acrimonious relationship. Unhappy at home and intent on obtaining a higher education, which Lomonosov could not receive in Mishaninskaya, he was determined to leave the village.

Determined to "study sciences", in 1730, aged nineteen, Lomonosov walked all the way to Moscow . Shortly after arrival, he was admitted into the Slavic Greek Latin Academy by falsely claiming to be a son of a Kholmogory nobleman. In 1734 that initial falsehood, as well as another lie that he was the son of a priest, nearly got him expelled from the academy but the investigation ended without severe consequences.

Lomonosov lived on three kopecks a day, eating only black bread and kvass , but he made rapid progress scholastically. It is believed that in 1735, after three years in Moscow he was sent to Kiev to study for short period at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy . He quickly became dissatisfied with the education he was receiving there, and returned to Moscow to resume his studies there. In five years Lomonosov completed a twelve-year study course and in 1736, among 12 best graduates, was awarded a scholarship at the St. Petersburg Academy. He plunged into his studies and was rewarded with a four-year grant to study abroad, in Germany, first at the University of Marburg and then in Freiberg .

The University of Marburg was among Europe's most important universities in the mid-18th century due to the presence of the philosopher Christian Wolff , a prominent figure of the German Enlightenment . Lomonosov became one of Wolff's students while at Marburg from November 1736 to July 1739. Both philosophically and as a science administrator, this connection would be the most influential of Lomonosov's life. In 1739–1740 he studied mineralogy and philosophy at the University of Göttingen; there he intensified his studies of German literature.

Lomonosov quickly mastered the German language, and in addition to philosophy, seriously studied chemistry , discovered the works of 17th century Irish theologian and natural philosopher Robert Boyle , and even began writing poetry. He also developed an interest in German literature. He is said to have especially admired Günther. His Ode on the Taking of Khotin from the Turks , composed in 1739, attracted a great deal of attention in Saint Petersburg. Contrary to his adoration for Wolff, Lomonosov had fierce disputes with Henckel over the training and education courses he and his two compatriot students were getting in Freiberg, as well as over very limited financial support which Henckel was instructed to provide to the Russians after numerous debts they had accumulated in Marburg. As the result, Lomonosov left Freiberg without permission and wandered for quite a while over Germany and Holland, unsuccessfully trying to obtain permission from Russian envoys to return to the St. Petersburg Academy.

During his residence in Marburg, Lomonosov boarded with Catharina Zilch, a brewer's widow. He fell in love with Catharina's daughter Elizabeth Christine Zilch. They were married in June 1740. Lomonosov found it extremely difficult to maintain his growing family on the scanty and irregular allowance granted him by the Russian Academy of Sciences . As his circumstances became desperate, he got permission to return to Saint Petersburg.

Lomonosov returned to Russia in June 1741, after being abroad 4 years and 8 months. A year later he was named an Adjunct of the Russian Academy of Science in the physics department. In May 1743, Lomonosov was accused, arrested, and held under house arrest for eight months, after he supposedly insulted various people associated with the academy. He was released and pardoned in January 1744 after apologising to all involved.

Lomonosov was made a full member of the academy, and named Professor of chemistry , in 1745. He established the academy's first chemistry laboratory. Eager to improve Russia's educational system, in 1755, Lomonosov joined his patron Count Ivan Shuvalov in founding Moscow University .

In 1760, he was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences . In 1764, he was elected Foreign Member of the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna In 1764, Lomonosov was appointed to the position of the State Councillor which was of Rank V in the Russian Empire's Table of Ranks. He died on 4 April (o.s.), 1765 in Saint Petersburg. He is widely and deservingly regarded as the "Father of Russian Science", though many of his scientific accomplishments were relatively unknown outside Russia until long after his death and gained proper appreciation only in late 19th and, especially, 20th centuries.

Was Mikhail Lomonosov the son of Peter the Great?

Tall in stature and possessing great physical strength, as well as an extraordinary inclination for the sciences and a love of the Russian language – these traits were inherent in both Tsar Peter and the great scholar and scientist Mikhail Lomonosov . However, these coincidences were sufficient to ignite a Soviet era myth in the country’s collective memory: that Lomonosov was the son of Peter the Great . Indeed, he studied in Europe like his ‘father’, loved all things German like his ‘father’... And, of course, thanks to the alleged patronage of his ‘father’, he was able to enroll at the prestigious Slavic Greek Latin Academy in Moscow.

Where did the legend come from?

Captain Vasily Korelsky

The author of the Soviet era myth is Captain Vasily Pavlovich Korelsky from the city of Arkhangelsk, which is the officially recognized birthplace of Lomonosov. In the 1950s the newspaper 'Soviet Fisherman' published Korelsky’s memoirs in which he claimed that he had seen a document suggesting that Lomonosov was the son of tsar Peter.

According to this story, allegedly in 1932, Captain Korelsky’s older brother had shown him a document that had been found in the attic. The note said that in January or February 1711, when the tsar was resting in the village of Ust’-Tosno, some 35 kilometers from St. Petersburg, a local girl Elena Sivkova, who was an orphan, had been brought to him for carnal pleasures. Luka Lomonosov, a local peasant, was the intermediary in the procurement of the girl. After Tsar Peter left, Elena became pregnant, and Luka married her to his relative Vasily Lomonosov, into whose family Mikhail was born. Captain Korelsky claimed that Peter had commanded that his son be named Mikhail.

Except for the memoirs of Captain Korelsky, which were published in a separate book in 1996 in Arkhangelsk, there is no credible historical evidence and source for this legend. Captain Korelsky claimed the note that was his source had been destroyed. However, because of the Russian people’s inherent love for sensational stories related to the famous and powerful, this legend began to spread and was widely accepted.

How to prove that Lomonosov wasn’t Peter’s son?

Mikhail Lomonosov

It is easy to refute the legend that Peter was responsible for the conception of Lomonosov in 1711 in Ust’-Tosno. According to many surviving documents we can track the movements of Tsar Peter in the autumn of 1710 and in early 1711. At that time, Peter was certainly in St. Petersburg. On November 20, 1710, which was during the Northern War with Sweden , events developed whereby Russia declared war on the Ottomans. In February-March 1711, Peter was traveling between St. Petersburg and Moscow, from where on March 17, together with his wife Catherine , he left for the Prut campaign against the Ottoman Empire. During this entire period, before leaving for the war in the south, the tsar didn’t go anywhere north of St. Petersburg.

In addition, if Lomonosov really was a secret love child of Peter the Great, then why didn't the tsar patronize him? As a young man, Lomonosov had to study on his own in Russia and abroad, and then all alone fought for his place under the sun in the St. Petersburg scientific community. His life was not easy and carefree at all.

On the other hand, there’s indication that Lomonosov may well have had powerful patrons. In 1728, three years before his departure for Moscow, young Lomonosov met with the archimandrite of the Solovetsky monastery Varsonofiy, who was an important church leader. When Lomonosov arrived in Moscow, he was immediately granted a meeting with the rector of the Slavic-Greco-Latin Academy, Archimandrite German (Koptsevich) of the Zaikonospassky Monastery. Subsequently, German was the one who identified Lomonosov as among the most capable students to study at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox

- Mikhail Lomonosov: The 'Russian Da Vinci'

- The first woman on the Russian throne: A foreigner blamed for witchcraft

- What was so 'great' about Peter the Great?

This website uses cookies. Click here to find out more.

- Basic facts

- Entertainment

- Opera and ballet

- Politics and society

- History and mythology

- Cinema and theater

- Science and technology

- Geography and exploration

- Space and aviation

- The Ryurikovich dynasty

- The Romanov dynasty

- Foreigners in Russia

- Of Russian origin

- On this day

On August 5, 1963, the Treaty banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Underwater, often abbreviated as the Partial Test Ban Treaty, was signed between the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain. …

Go to On this day

Previous day Next day

Peter Carl Faberge

Peter Carl Faberge was a world famous master jeweler and head of the ‘House of Faberge’ in Imperial Russia in the waning days of the Russian Empire.

Go to Foreigners in Russia

Prominent Russians: Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov was the first Russian scientist-naturalist of universal importance. He was a poet who laid the foundation of modern Russian literary language, an artist, an historian and an advocate of development of domestic education, science and economy. In 1748 he founded the first Russian chemical laboratory at the Academy of Sciences. On his initiative the Moscow University was founded in 1755.

Universal scientist

The scientific discoveries of Lomonosov enriched many branches of knowledge. Among his amazing heritage are the following discoveries and ideas:

• He regarded heat as a form of motion;

• He suggested the wave theory of light;

• He contributed to the formulation of the kinetic theory of gases;

• He stated the idea of conservation of matter in the following words: “All changes in nature are such that inasmuch is taken from one object insomuch is added to another.

So, if the amount of matter decreases in one place, it increases elsewhere. This universal law of nature embraces the laws of motion as well -an object moving others by its own force in fact imparts to another object the force it loses”;

• In 1748, Lomonosov created a mechanical explanation of gravitation;

• Lomonosov was the first person to record the freezing of Mercury;

• He was also the first to hypothesize the existence of an atmosphere on Venus based on his observation of the transit of Venus of 1761;

• Believing that nature is subject to regular and continuous evolution, he demonstrated the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber. In 1745, he published a catalogue of over 3,000 minerals;

• In 1760, he explained the formation of icebergs;

• As a geographer, Lomonosov got close to the theory of continental drift, theoretically predicted the existence of Antarctica and invented sea tools which made writing and calculating directions and distances easier;

• Lomonosov was proud to restore the ancient art of mosaics;

• He wrote more than 20 solemn ceremonial odes, notably the “Evening Meditation on God’s Grandeur”;

• In 1755, he reformed the Russian literary language by combining Old Church Slavonic with the vernacular; ´

• He applied an idiosyncratic theory to his later poems – tender subjects needed words containing the front vowel sounds E, I, YU, whereas things that may cause fear (like “anger,” “envy,” “pain” and “sorrow”) needed words with back vowel sounds O, U, Y - an early version of what is now called sound symbolism.

To be more precise, Lomonosov developed the atomic-molecular conception of substance structure. During the domination of the teplorod theory he asserted that heat is caused by movement of corpuscles. Lomonosov formulated the principle of matter and movement conservation. He excluded phlogiston from chemical agents and laid the basis of physical chemistry. Lomonosov examined atmospheric electricity and gravity. He put forward the color doctrine. He created a number of optical devices. During a transit of Venus across the Sun on 26 May 1761 Lomonosov discovered that Venus possessed an atmosphere. He described the structure of Earth, explained the origin of treasures of the soil and minerals, and published a manual on metallurgy. He emphasized the importance of the North Sea route in research and development of Siberia. A supporter of deism, he materialistically examined natural phenomena.

Lomonosov was the author of works on Russian history. He was the greatest Russian poet-enlightener of the 18th century, one of the founders of syllabic-tonic versification. Lomonosov was the founder of philosophical and Russian odes of high civil character. The author of poems, epistles, tragedies, satires, fundamental philological works and scientific grammar of Russian, he also revived the art of mosaic and production of smalt, creating mosaic pictures in cooperation with his pupils. He became a member of the Academy of Arts in 1763.

Early years

Lomonosov was born in the village of Mishaninsk not far from Kholinogory, near the White Sea. This region along the northern coast of Russia was separated from the rest of the country by vast forests and swamps, nearly impassible in summer, but easily crossed when frozen in winter. The inhabitants of this isolated region had never been exposed to the Tatar conquest nor to the institution of serfdom, which had affected much of the rest of Russia. They were, however, in close contact with foreign trade and traders; their ports of Archangel and Kholmogory were the main gateways through which foreign goods from Western Europe reached Russia. As a result, most of the natives of this region, though classed as peasants, were far more independent and progressive than their counterparts in more southerly areas.

Lomonosov was taught reading and writing early and was an avid reader. In 1724 he received the books “Grammar” by Smotritsky, “Arithmetics” by Magnitsky and “Rhyme Psalm-book” by Semeon Polotsky, which he subsequently called the gates of his erudition. He was the son of a fisherman. Although the boy accompanied his father on fishing excursions and trading expeditions, he was not happy at home. His mother had died when he was still very young, and his father had married twice afterward, his second wife having also died early. The stepmother considered Lomonosov lazy because of his constant reading, and he reported later that he “was obliged to read and study, when possible, in lonely and desolate places and to endure cold and hunger.” Therefore when he was nineteen, he resolved to go to Moscow to seek further education.

Entering the world of science

Lomonosov had tried to enter Kholmogorsk School but being a fisherman’s son, he had been rejected. In Moscow he chose to conceal his poor background in order to gain entrance. After a three-month journey on foot, in 1730 Lomonosov entered the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy, where in 1735 he studied the penultimate course of “philosophy.” In 1734 he listened to lectures at the Kievo-Mogilyanskaya Academy and studied the Ukrainian language and culture. Mastering the Latin and Greek languages he was exposed to the riches of antique and European culture. After returning from Kiev he was sent with other students to St. Petersburg as a student of the university at the Academy of Sciences.

After graduating from the Academy, Lomonosov was sent to study mining in Saxony. He studied mineralogy and chemistry in Germany, first at Marburg University and then at the Freiburg Academy. There he gained extensive knowledge in the fields of physics and chemistry, and studied German, French, Italian and English, which enabled him to get acquainted with the literature of the time. Abroad Lomonosov worked in the field of Russian poetry and created the harmonious theory of the Russian syllabic-tonic verse, which was presented by him in “Letter on rules of Russian versification” and which is still in use today. He understood that there wasn't a uniform Russian literary language or a uniform Russian culture. He decided to do everything possible to lay the foundations of new Russian culture, science, literature and literary language. In 1742, after returning to Russia, Lomonosov was appointed junior scientific assistant to the Academy of Sciences in physics and in 1745 became the first Russian elected to a professorial post. He was appointed to a physics position at the St. Petersburg Academy of Science. The Academy was highly respected in Europe. It was staffed at this time mainly by foreign scientists, for example Lehmann.

Lomonosov had a particular interest in mineralogy dating back to his German education. He noticed natural groupings or occurrences of certain ore minerals and noted that certain minerals typically indicated the presence of other minerals. This phenomenon is now called Paragenesis - the common genesis of related minerals. His paper on “Discourses on the hardness and liquidity of bodies” describes geometric arrangements of packing spheres (atoms) in the crystal lattice. He noted the constancy of crystal interfacial angles. Lomonosov also applied chemical analysis to determine the genesis of various rocks and proved the organic origin of soil, peat, coal, petroleum and amber.

On 6 June 1740 he married Elizabeth Zilch, the daughter of a former city councilor of Marburg. The marriage was kept secret for several years, perhaps because he feared that the authorities would not approve of the foreign marriage. At last he was able to get in touch with the Academy in St. Petersburg and received an official recall to the capital. He reached it on 8 June 1741. It was not until 1744 that he felt able to send for his wife, who rejoined him in the summer of that year.

Achievements in literature

In spite of his difficulties in Germany, he had been able to complete several dissertations on scientific subjects and to begin to compose the odes that later brought him fame as a poet. The high regard for his abilities attested by his favorable reports from Wolff, Duising and even Henkel, made a deep impression at the Academy, and soon after his return he was made adjunct in the Class of Physical Science. His salary was 360 rubles a year, an ample sum at the time, but unfortunately the Academy had no funds to pay it, and so he was given the privilege of buying books at the Academy bookshop for a nominal sum and then selling them for whatever he could get. After breaking with one of his masters, the chemist Johann Henckel, and many other mishaps, Lomonosov returned in July 1741 to St. Petersburg.

The Academy, which was directed by foreigners and incompetent nobles, gave the young scholar no precise assignment, and the injustice insulted him. His violent temper and great strength sometimes led him to go beyond the rules of propriety, and in May 1743 he was placed under arrest. Two odes sent to Empress Elizabeth won him his liberation in January 1744, as well as a certain poetic prestige at the Academy.

Working in the Academy of Science

Affairs at the Academy at this time were in a very confused state. Schumacher had been running the Academy in a very despotic fashion and had favored the German members at every turn; Russia was then governed by Biron, the incompetent favorite of Empress Anne, but when she died the throne was taken by Elizabeth II, daughter of Peter the Great, and Biron fell from power. The enemies of Schumacher (and he had many) were then able to attack him openly and finally bring about his arrest.

Lomonosov sympathized with Schumacher's opponents, since as a patriotic Russian he felt that the German party had gained too much power in the Academy. He believed that Schumacher himself was responsible for many of the difficulties that had occurred. His own position was not too strong, for he himself was engaged in quarrels with various employees of the Academy, sometimes resulting in physical violence. As a result he was placed under house arrest and was freed only after a public apology.

Schumacher was soon cleared of the charges against him and resumed his former position of authority. After this, however, there was constant discord between the two men, and their struggles for advantage greatly interfered with Lomonosov's later scientific activities. His “Russian Grammar,” which defined features of Russian literary language, was the first real Russian grammar; “Eloquence compendium” is a course of general theory of literature. The treatise “About benefits of church books in Russian language” is the first experience in Russian stylistics.

Poetry occupied an important place in the life of Lomonosov: “Conversation with Anakreon” and “The Hymn to Beard.” He also wrote the plays “Tamira and Selim” and “Demofont” and numerous odes.

The Moscow University and lifelong devotion to science

Concerned about the distribution of education in Russia, Lomonosov insisted on the creation of a Russian University of European style accessible to all social groups of the population. His efforts were crowned with success in 1755. On his project there was founded the university in Moscow. Nowadays this University (Moscow State University) is one of the most prestigious universities in Russia and carries Lomonosov’s name. Lomonosov did much for the development of Russian science, which gave rise to Russian scientists and professors who in turn could teach at the university.

The last years of Lomonosov's life were not happy ones. He was plagued with debts from the factory at Ust Ruditsky and by almost constant ill health. His quarrels with his colleagues became ever bitterer. During his final illness he gave way to pessimism, saying: “I see that I must die and I look on death peacefully and indifferently. I regret only that I was unable to bring to completion everything I undertook for the benefit of my country, for the increase of learning and for the greater glory of the Academy, and now, at the end of my life, I realize that all my good intentions will vanish with me.” Despite the honors that came to him, he continued to lead a simple and industrious life, surrounded by his family and a few friends. His prestige was considerable in Russia, and his scientific works and his role in the Academy were known abroad. Lomonosov was well regarded by contemporary European scientists. He was made an honorary member of the Swedish Academy of Science in 1760 and became an honorary member of the Bologna Academy of Science in 1764. Lomonosov is memorialized in many place names –for example, an Arctic submarine ridge, an Atlantic current and more.

Last years and legacy

In the spring of 1765 Lomonosov caught a cold, fell ill with pneumonia and died. He was buried at Lazarevskoye Cemetery in the Aleksandro-Nevskaya Lavra (Monastery) in St. Petersburg.

Empress Catherine II the Great had the patriotic scholar buried with great ceremony, but she confiscated all the notes in which were outlined the great humanitarian ideas he had developed. Publications of his works were censored as material that constituted a menace to the system of serfdom, particularly that concerned with materialist and humanist ideas. Efforts were made to view him as a court poet and an upholder of monarchy and religion rather than as an enemy of superstition and a champion of popular education.

In 1948 Oranienbaum, a town in the outskirts of St. Petersburg, was renamed Lomonosov. The Chernyshev Bridge, Chernyshev Square and Chernyshev Lane also took his name. Lomonosovskaya metro station and some industrial companies (including Lomonosov Porcelain Plant) were named after Lomonosov. In 1949 the Lomonosov Museum was opened in the building of Kunstkammer, where the scientist had worked from 1741. A bust of Lomonosov was installed on Lomonosov Square in 1892 (sculptor P.P. Zabello, architect Lytkin) and in 1986 a statue of the great scientist was erected at Universitetskaya Embankment (sculptor Petrov and architect Sveshnikov).

Written by Tatyana Klevantseva, RT

Corporate profile Job opportunities Press releases Legal disclaimer Feedback Contact us © Autonomous Nonprofit Organization “TV-Novosti”, 2005–2021. All rights reserved.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Mikhail Lomonosov (born November 19 [November 8, Old Style], 1711, near Kholmogory, Russia—died April 15 [April 4], 1765, St. Petersburg) was a Russian poet, scientist, and grammarian who is often considered the first great Russian linguistics reformer. He also made substantial contributions to the natural sciences, reorganized the St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Sciences, established in ...

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (/ ˌ l ɒ m ə ˈ n ɒ s ɒ f /; Russian: Михаил (Михайло) Васильевич Ломоносов; 19 November [O.S. 8 November] 1711 - 15 April [O.S. 4 April] 1765) was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education, and science.Among his discoveries were the atmosphere of Venus and the law of ...

He was a member of the prestigious Academy of Arts at St. Petersburg. Personal Life & Legacy. Mikhail Lomonosov met Elizabeth Christine Zilch while studying in Germany and they got married in 1740. He died of influenza on 15 April 1765, at his residence in St. Petersburg, Russia, at the age of 53. Trivia.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov, (born Nov. 19, 1711, near Kholmogory, Russia—died April 15, 1765, St. Petersburg), Russian scientist, poet, and grammarian, considered the first great Russian linguistic reformer.Educated in Russia and Germany, he established what became the standards for Russian verse in the Letter Concerning the Rules of Russian Versification.

M ish-aninskaya, Arkhangelsk province, Russia, 19 November 1711; d, St. Petersburg, Russia, 15 April 1765) chemistry, physics, metallurgy, optics. Lomonosov's father, Vasily Dorofeevich, owned several fishing and cargo ships; his mother, Elena Ivanovna Sivkova, was the daughter of a deacon. A gifted child, Lomonosov learned to read and write ...

Mikhail Lomonosov was born in 1711 in the Arkhangelsk Region in the far north of Russia (615 miles north of Moscow). His father was a wealthy peasant fisherman who, like his ancestors, was ...

The son of a poor fisherman, Mikhail Vasilievich Lomonosov was born on November 19 (November 8 on the calendar used at the time), 1711, near Kholmogory, Russia. At the age of 19 he left his village, on foot and penniless, to study in Moscow. At the Slavonic-Greek-Latin Academy, the sons of nobles jeered at him, and he had scarcely enough money ...

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (Михаи́л Васи́льевич Ломоно́сов) (November 19 [O.S. November 8] 1711 - April 15 [O.S. April 4] 1765) was a Russian writer and polymath who made important contributions to literature, education, and science Among his most important contributions are the founding of Moscow State University, the revision of the Russian literary language ...

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education, and science. Among his discoveries were the atmosphere of Venus and the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions. His spheres of science were natural science, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, history, art, philology, optical devices and others.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (November 19 [ O.S. November 8] 1711 - April 15 [ O.S. April 4] 1765) was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer. Lomonosov made important contributions to literature, education, and science. Among his discoveries was the atmosphere of Venus . As a scientist, he contributed to the fields of chemistry including ...

Curiously unsung in the West, Lomonosov broke ground in physics, chemistry, and astronomy; won acclaim as a poet and historian; and was a key figure of the Russian Enlightenment. On 7 December 1730, a tall, physically fit 19-year-old, the son of a peasant-turned-fisherman, ran away from his hometown, a village near the northern Russian city of ...