Communication Process: Definition, Steps, and Importance

At first glance, the communication process seems simple enough, right?

You say a few words to the interlocutor, they understand what you mean and give you a prompt response.

But, that’s not always the way things go. Say that a joke you make falls flat, and you have to think of ways to redirect the conversation. Or, you use the word “ bike ” to talk of your love of cycling, but the interlocutor thought of motorbikes.

These issues occur because the communication process is ever-changing and depends on 8 interconnected factors .

In the following sections, we’ll devote more attention to the importance of the communication process and each of its factors.

We’ll also hear from experts who’ll share some of their tried-and-true tips on improving the communication process and eliminating miscommunication .

Without further delay, let’s jump in.

Table of Contents

What is the communication process?

The communication process encompasses a sequence of acts necessary for effective communication . These acts ensure the successful transmission of meaning between at least 2 participants, helping them to understand each other without issues.

However, while the communication process is a comprehensive and reliable tool that can help achieve successful communication between two or more people, it sometimes isn’t as straightforward as it first appears.

In reality, effective communication requires careful attention to the 8 interconnected factors that make up the process . When properly followed, the communication process can ensure the intended message is conveyed and understood without misinterpretation or confusion.

But, this requires a deep understanding of the process and active participation.

What are the parts of the communication process?

In the book The Process of Communication: An Introduction to Theory and Practice , American communication theorist David K. Berlo writes:

“ With the concept of process established in our minds, we can profit from an analysis of the ingredients of communication, the elements that seem necessary (if not sufficient) for communication to occur. ” – David K. Berlo

When Berlo mentions the “ concept of process ,” he references the fact that communication, like other processes, is dynamic and ever-evolving .

Take the conversations you have with your coworkers as an example. The topic changes depending on whom you’re speaking to, as does your tone of voice and body language .

But, some ingredients remain the same with each interaction — the 8 elements of the communication process. These are:

- Environment,

- Context, and

- Interference.

We’ll now examine these factors in greater detail.

Element #1: Source (Sender)

In the process of communication, the source or sender is the person who speaks in order to create and impart a specific message to their audience .

The source may convey their message using verbal language but also through their:

- Body language,

- Clothing, and

- Tone of voice.

According to Berlo, communication is virtually impossible without a source :

“ We can say that all human communication has some source , some person or group of persons with a purpose, a reason for engaging in communication. ” – David K. Berlo

Before speaking or writing, the source has to decide what they want to convey and how they wish to format their message.

Then, the source encodes this information using words and putting them in specific order to achieve the desired meaning. Only after taking these steps can a source deliver the message to the audience.

Element #2: Message

The message is the source’s purpose of communication , and during the communication process, the source converts this purpose into speech or text.

In The Basics of Speech Communication , Scott McLean describes the message as “ the stimulus or meaning produced by the source for the receiver or audience .”

McLean also emphasizes that the message is more than words strung together by order and grammatical rules . How we format and transmit our message depends on the type of communication we intend to engage in.

For instance, in written communication, you can change and reshape a message through:

- The use of emojis ,

- The addition of subheadings,

- Adjustments in writing style, and

- Formatting the message .

And, as we’ve mentioned, your appearance and body language during in-person meetings or video conferencing calls can also affect how you communicate your message.

But, there’s more to it.

Our environment and the context we provide can imbue the message with additional meaning. On the other hand, noise can obscure our intended meaning during the interaction and become a communication barrier .

Element #3: Channel

The channel is the manner by which the message travels from the source to the receiver .

In his examination of communication models , Berlo touches on channels, stating that:

“ A channel is a medium, a carrier of messages. It is correct to say that messages can exist only in some channels; however, the choice of channels often is an important factor in the effectiveness of communication. ” – David K. Berlo

If you think of the streaming services you’re subscribed to as separate channels, they all combine visual and auditory information to communicate a specific message. When you look away from the screen, you can still hear the program and gather enough clues to understand what’s going on.

The same goes if you lower the volume. Thanks to subtitles and visual cues, you’ll still be able to follow the plot without much trouble.

A similar scenario happens in real-time communication . Depending on our purpose and needs, we can choose from several different channels, which could include:

- Voice and video calls,

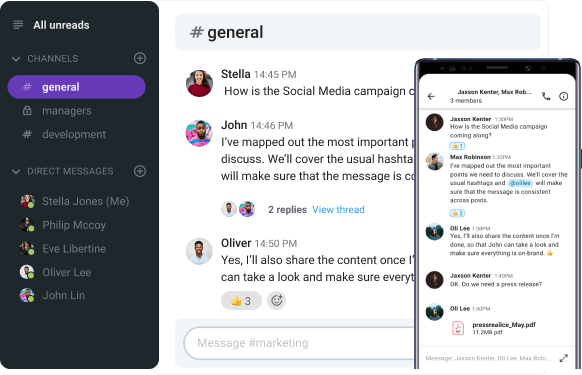

- Direct messaging in a business communication app ,

- Voice messages , and

- Emails.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

For a deeper look into communication channels and information about which channels are suitable for different kinds of communication, see this guide:

- Channels of communication

Element #4: Receiver

As the name suggests, the receiver is the person whose task is to receive the source’s message .

The receiver is just as important as the source in the communication process because their actions can make or break the interaction.

No matter how carefully you choose your words, the communication situation may go awry, as you have no control over how the interlocutor:

- Interprets the message ,

- Behaves after hearing the message , or

- Uses their cultural experience and knowledge to participate in communication.

The above points determine whether the receiver will choose to provide feedback to the source and actively participate in the communication action . No further communication can occur if the receiver decides not to respond and withholds feedback.

Keep in mind that a receiver may not always respond using verbal messages.

For example, if you are speaking at a business summit attended by more than 200 people, you’ll feel the audience sizing you up. Although the attendees won’t voice their opinion on what you’re saying, you can modify your performance and add more information to your message by watching the reaction of audience members.

Element #5: Feedback

Feedback is the response the receiver returns to the source.

- Unintentional or intentional and

- Nonverbal or verbal .

Feedback is vital in letting the source know how the receiver has interpreted the message .

Another important function of feedback in communication is to give the receiver the chance to:

- Request additional information or clarification,

- Support or object to the source’s claims, and

- Inform the source how to modify their approach.

The role feedback plays in the communication process cannot be overstated.

In the research article Some effects of feedback on communication , Mueller and Leavitt detailed the result of an experiment that dealt with how different levels of feedback affected communication. Their conclusion was that:

“ Increasing feedback resulted in increasing [communication] accuracy . ” – Mueller and Leavitt

Feedback is instrumental in professional communication, and so is feedforward. To learn more about how the two concepts are related and how to use them to your advantage, read this blog post:

- Feedback vs. feedforward: Moving from feedback to feedforward

Element #6: Environment

The environment refers to the mental and physical contexts in which we communicate , both as the sender and the receiver of messages. It encompasses the setting, atmosphere, and conditions that may influence the interpretation and reception of information .

For example, if you’re in a conference room, your environment might include:

- Windows, and

- A whiteboard.

Psychological aspects of the environment may include whether the topic is discussed in a transparent manner and whether the communication is formal or informal.

Free business communication tool

Secure, real-time communication for professionals.

FREE FOREVER • UNLIMITED COMMUNICATION

Element #7: Context

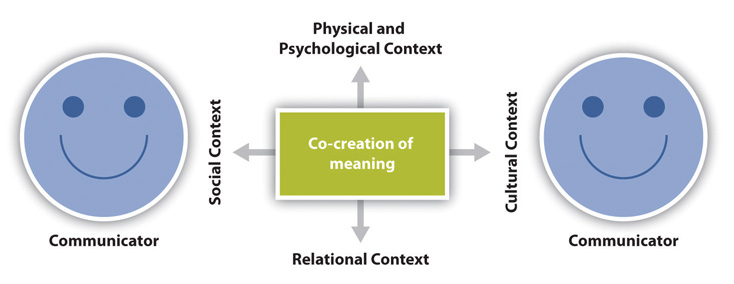

While some confuse context for the environment when talking about the communication process, context refers to the:

- Setting, and

- Expectations of the conversation participants.

For example, when you head into the office, you expect those present to be smartly dressed and speak and act in a specific way. Thus, anyone wearing a T-shirt and shorts would stick out like a sore thumb.

That’s because context dictates how formal or informal the environment should be.

During work meetings, someone’s position and expertise affect when and how they will speak, as well as what they will speak about. During short breaks, everyone is free to quickly catch up or talk about informal topics. But, when the meeting resumes, all off-topic conversations cease.

As a crucial element of the communication cycle, context is also vital in cross-cultural communication. Namely, the cultural context we inherit and learn through experience affects how we convey messages. For more information on cross-cultural communication and cultural context, check out this detailed blog post:

- How to perfect cross-cultural communication at the workplace

Element #8: Interference (Noise)

The final component of the communication process, interference , is also sometimes called noise .

Interference or noise can be anything that distorts or modifies the intended meaning of a message .

If your desk is by the window, you likely see billboards and commuters and hear traffic sounds. This noise can halt your stream of thought or interrupt a conversation with coworkers.

However, in the communication cycle, the noise could also be psychological .

Although you work in a quiet environment, your own thoughts could block you from fully listening to what someone is saying. For instance, if your superior hasn’t finished talking to you, but you are already coming up with what to say in return, chances are you’ve missed a few points.

Similarly, if you forgot to drink water before joining a meeting, you may pay more attention to the water cooler than the presentations.

Unfortunately, the modern workforce is rife with distractions that act as communication hurdles. The occasional pinging from your team messaging app may prevent you from giving your all to the task at hand. If you’ve struggled with this in the past, take a look at this helpful post:

- How to ensure business chat is not distracting your team

How does the communication process work?

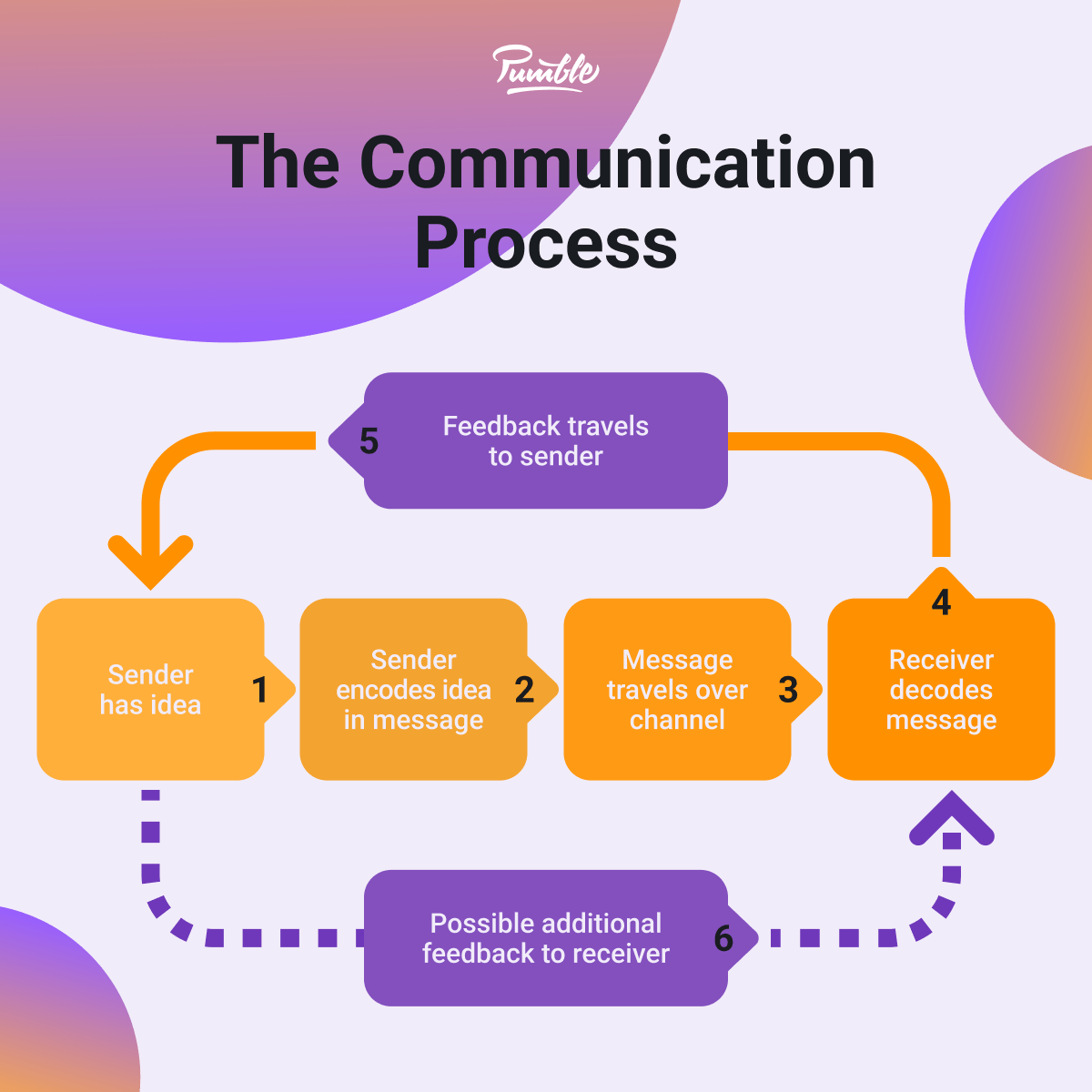

The communication process consists of 5 essential steps . They are:

- Idea formation,

- Message encoding,

- Message transmission,

- Message decoding , and

Breaking down these communication cycle phases will help you better understand your role in conversation and improve your communication skills.

Step #1: The source or sender has an idea (Idea formation)

Communication begins with the source, the person who thinks of and sends the message.

Several things can influence the message a source wants to convey, including their:

- Background , and

- Context of the communication situation .

For example, how you greet a coworker depends on:

- Your mood,

- Their position within the company,

- Your own culture, and

- Your knowledge of your coworker’s culture.

Consequently, before saying or writing anything, you have to consider the above factors to prevent misinterpretation and confusion.

Moreover, a source should always think about how the receiver or audience will respond to the message. One of the most invaluable skills an effective communicator can hone is the ability to adapt their message so that it elicits a positive response from the interlocutor.

Step #2: The source encodes the idea in a message (Encoding)

Encoding is the second step in the process of communication. This phase consists of transforming an idea into gestures and words that will successfully carry its meaning to the receiver .

However, encoding can be a challenging task as different people associate different meanings with the same words.

According to Guffey and Loewy in Business Communication: Process & Product , miscommunication that stems from mismatched meanings is called bypassing , and it is one of the most common pitfalls of professional communication.

To avoid these complications, skilled communicators should strive to use familiar words because the goal is to have the source and receiver agree on their meanings .

As one HBR article on language and culture states, just because you and your coworkers share a language doesn’t mean you share the same business culture , too.

Let’s see how language and culture can clash in the example below.

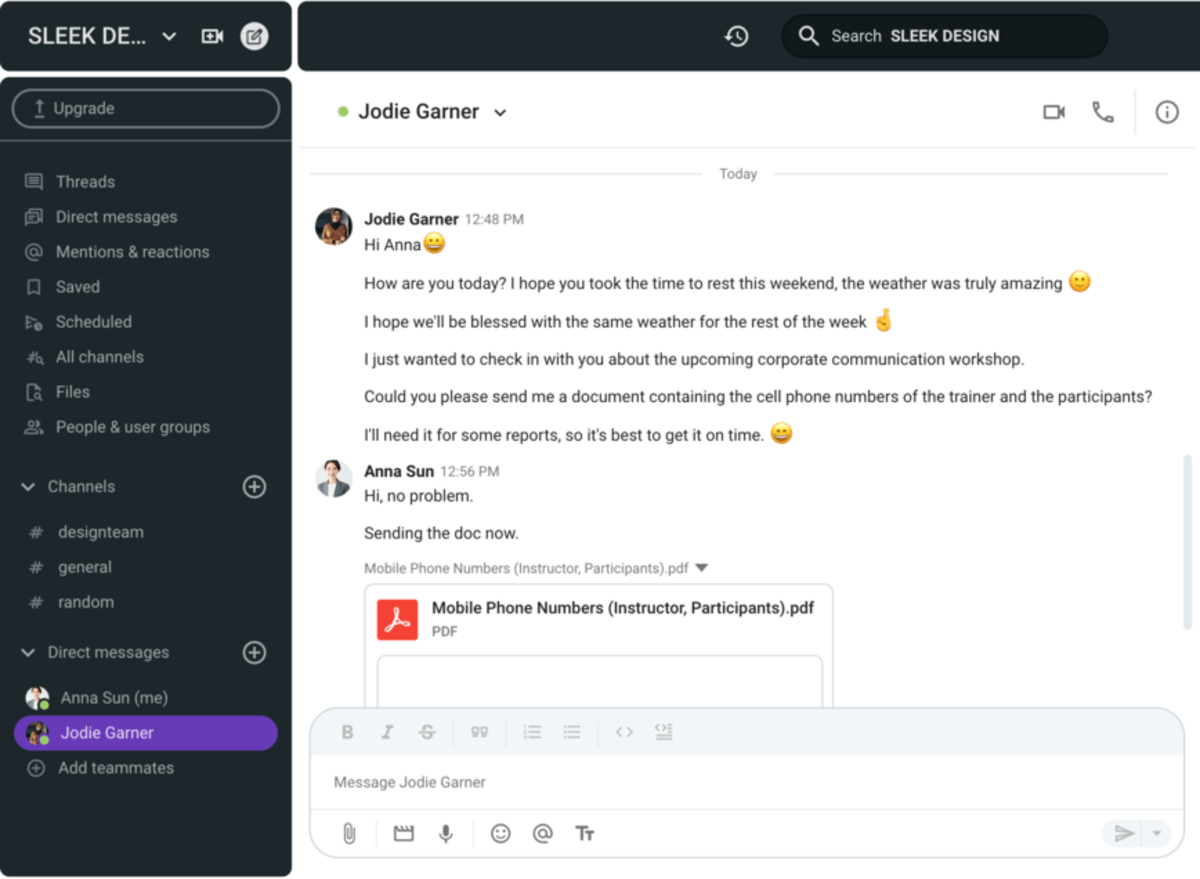

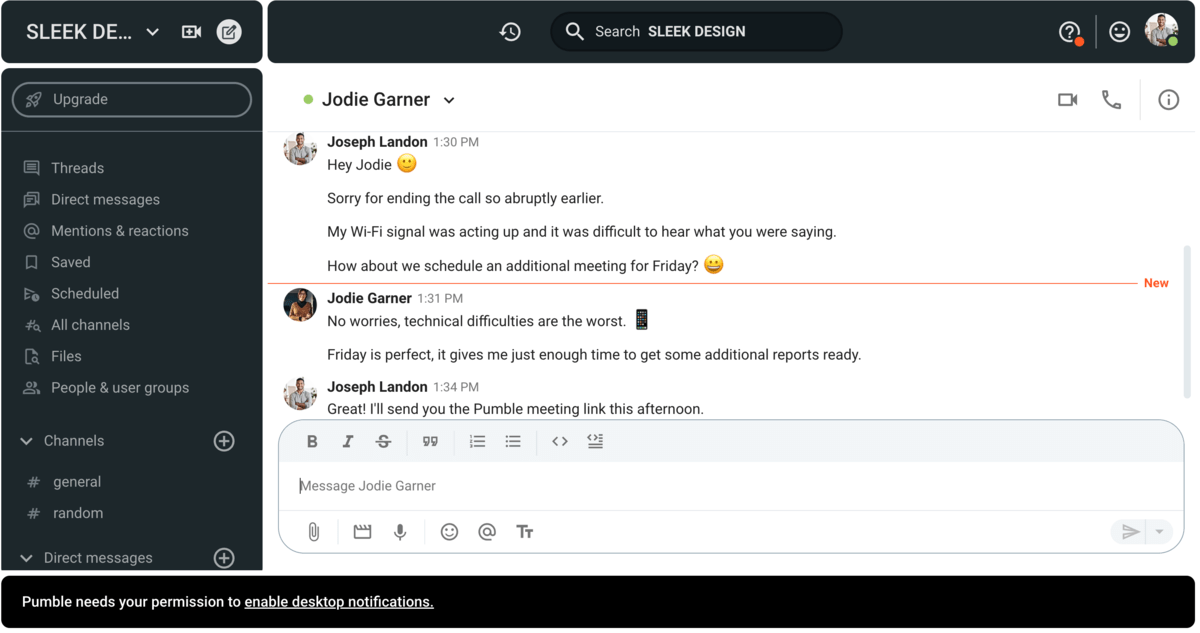

Jodie has sent a message to Anna, the new administration officer who has moved to the US from the UK. Jodie starts with casual chit chat before diving into the point of her message.

While that is considered polite behavior in the US, it can grate on people from countries where it is customary to get to the point without veering off-topic. Furthermore, Jodie uses the terms “ trainer ” and “ cell phone .” While these don’t throw Anna off, in the UK, it’s common to hear “ coach ” or “ instructor ” and “ mobile phone. ”

Finally, Anna’s response is brief and doesn’t venture into non-work-related territory.

Step #3: The message is transmitted via a communication channel (Transmission)

During the communication cycle, it is necessary to find the best way to physically transmit the message to the receiver. The transmission medium is the channel , and we can share messages via:

- Business communication apps ,

- Announcements,

- Phone calls,

- Pictures, and

- Memorandums.

Deciding on the most effective channel is imperative because it can affect how a receiver interprets both verbal and nonverbal messages .

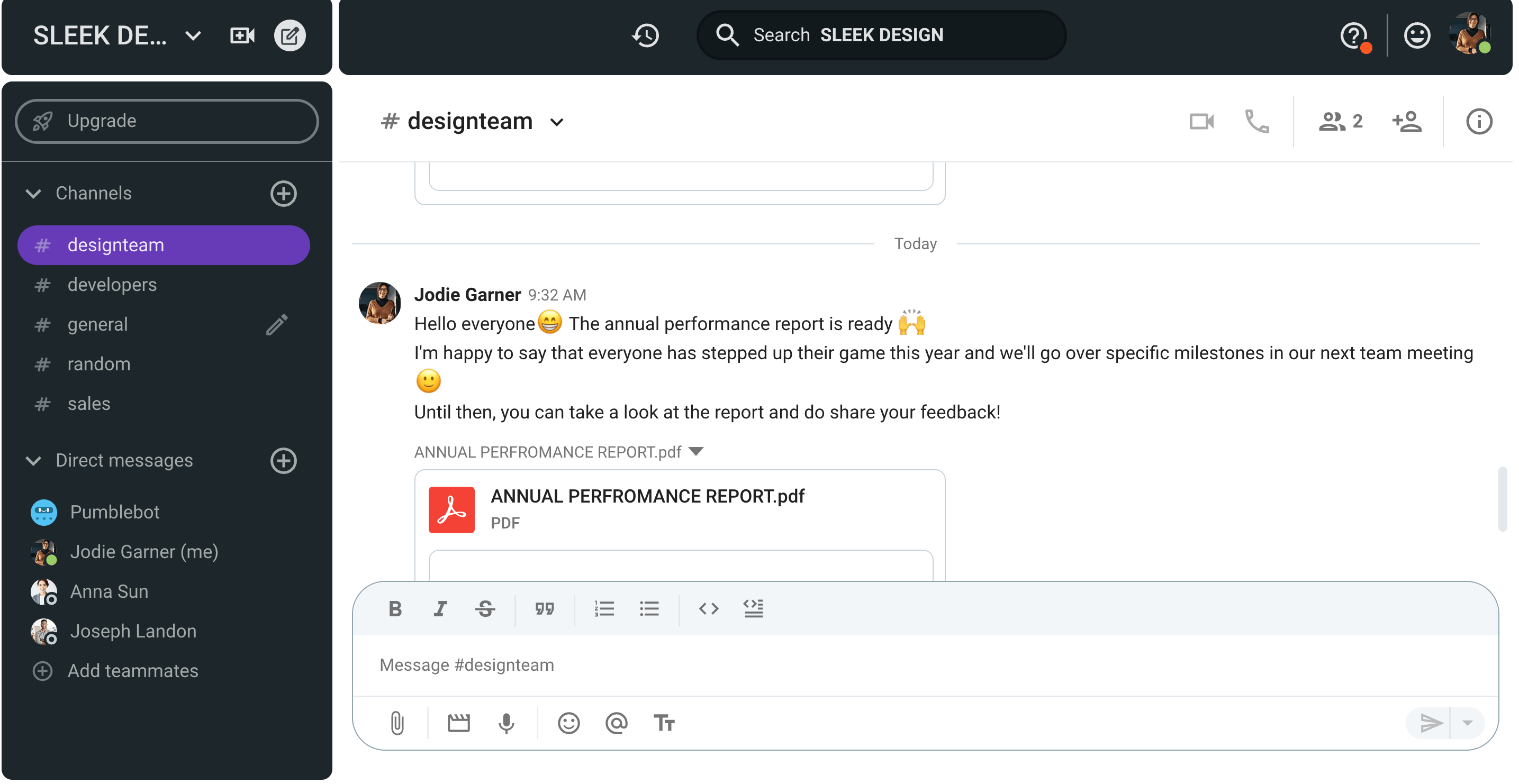

For instance, in the example below, Jodie is sharing the annual performance report with her colleagues. How they receive the message will depend on:

- The tone present throughout the report,

- The document’s layout, and

- The inclusion of graphics and charts.

Of course, before picking the most effective channel, the source must consider the noise and how it could interfere with the communication process.

As we’ve discussed, anything that obstructs the communication cycle is considered noise.

These interferences may take many forms, from misspellings in business emails to poor connection during a virtual call . However, choosing an unsuitable time to send an email or scheduling a team meeting for a simple update can also be an interference.

Step #4: The receiver decodes the message (Decoding)

An essential phase of the communication cycle — decoding — occurs when the receiver analyzes the message and converts its symbols to uncover the intended meaning .

Successful communication can only happen when the receiver cracks this code — that is, when they comprehend what the source intended to say .

But, achieving effective communication is easier said than done because no two people share the same experiences and knowledge. Moreover, numerous communication barriers can get in the way of decoding and halt the entire process.

Some factors that undermine decoding messages can be internal , and these include:

- A lack of attention when someone is speaking and

- Pre-existing cognitive biases and prejudice towards the source.

External factors can also impede the communication process. For example, it might be hard to decipher someone’s words in a loud environment, and misunderstandings are bound to happen.

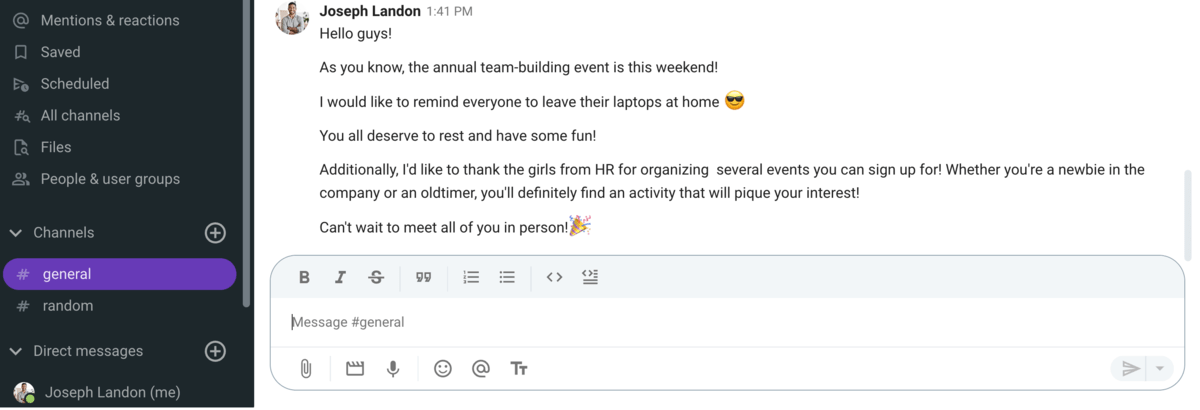

However, semantic hurdles can cause severe communication issues in a professional setting. For example, let’s analyze the announcement below.

Joseph has posted what he thinks is an exciting announcement about an upcoming company event. While his intentions may have come from the right place, his words have definitely missed the mark.

His choice to refer to new hires as “ newbies ,” the female employees as “ girls ,” and seasoned employees as “ oldtimers ” has the potential to offend part of the workforce.

Thus, these word choices could lead to strong reactions that prevent the employees from focusing on the overall message.

Step #5: Feedback reaches the source

Feedback is the backbone of communication and covers the interlocutor’s nonverbal and verbal responses. These signals let the source know how someone has received and understood the message .

For example, when a coworker asks, “ How’s your day going? ” you can respond with, “ Good, thanks. And yours? ”.

Or, if you’ve had a particularly draining day, you might smile and shrug your shoulders.

The same goes for using team communication apps . You can:

- Send a message,

- Post a comment, or

- Use an emoji to show how you feel.

Of course, different people share varying degrees of feedback, which is why it’s a good idea to encourage feedback with questions like:

- “ Is everything I’ve said clear? ”

- “ Do you need clarification on anything I’ve mentioned? ”

Remember that overwhelming the receiver with too much information may confuse them and thus lead to a lack of feedback.

Think of your delivery, time it appropriately, and give the interlocutor enough time to organize their thoughts.

Additionally, it’s essential to differentiate between 2 types of feedback:

- Evaluative feedback and

- Descriptive feedback .

Evaluative feedback doesn’t reflect whether the receiver has understood the source. Instead, it is often judgemental and can push the source into defensiveness .

On the other hand, descriptive feedback results from the receiver understanding the intended meaning of the source’s message.

For example, saying, “ I see how the numbers suggest we should focus more on inbound marketing in the next quarter, ” is better than stating, “ These numbers don’t look too good. ”

The first response invites others to become active in the conversation, while the second acts as more of a deterrent.

Do you want to become better at giving and requesting constructive feedback? If that’s the case, head to the blog posts below:

- How to give constructive feedback when working remotely

- How to ask your manager for feedback

Tips for improving the communication process

Now that we’re familiar with the elements and phases of the communication process, we can focus on learning how to ensure the best possible outcomes.

Tip #1: Beware of bypassing

Business communication is complex, and unless you’re careful, bypassing could become a common occurrence.

Bypassing is a phenomenon that happens when the source and receiver attach 2 wholly different meanings to a single word .

For example, if you’ve just landed your first job after graduating from university, seeing “ meeting cadence ” mentioned in a message from your manager might confuse you.

You may immediately think of the more well-known definition of the word “ cadence, ” which is the inflection of someone’s voice. But, your manager is referring to the frequency of team meetings, and it could take a while to straighten things out.

The good news is that business communication doesn’t have to be convoluted. You can prevent bypassing if you:

- Avoid using business jargon in the workplace ,

- Use simple and clear language , and

- Proofread your messages and emails to eliminate spelling errors and vague wording .

Tip #2: Strive to be a more attentive listener

Even when the source goes to great lengths to neatly package their message, their efforts will go to waste if the interlocutor is a poor listener.

Fortunately, active listening is a skill, and you can learn how to leverage it to your advantage in business communication.

In Communication in Business: Strategies and Skills , Judith Dwyer cites Gamble and Gamble (1996), who have identified 6 common behaviors most poor listeners exhibit .

These disruptive behaviors are:

- Dart thrower : Questioning the speaker and the validity of their story as soon as they make a mistake, no matter how minor it is.

- Ear hog : Dominating the communication situation by pushing your story and preventing others from telling their side.

- Bee : Only listening to parts of the conversation that interest you the most and ignoring everything else.

- Earmuff : Sidetracking the conversation to avoid confronting specific information.

- Gap filler : Coming up with additional information to prove you’ve heard the whole story, although you only zeroed in on parts of it.

- Nodder : Feigning listening by pretending to pay attention to the speaker. In reality, you are thinking about a different topic entirely.

Sometimes, we inadvertently engage in the above behaviors, so it’s essential to join every communication act without preconceived notions.

According to Joanna Staniszewska , a seasoned marketing, communication and HR professional, communication is a two-way street, and active listening is one of the most effective strategies:

“ Actively listening to others fosters trust and understanding. Encourage individuals to pay attention, ask questions, and confirm their comprehension during conversations. ”

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Do you want to learn more tips on becoming a present and attentive listener? If so, we have just the post for you:

- How to engage in deep listening in the workplace

Tip #3: Create an environment that encourages feedback

Establishing stable feedback loops positively impacts employee engagement , creating a safe space for people to self-advocate at work .

A system that compels team members to speak up without reservations in manager-employee relationships is invaluable. It can act both as a channel for employee recognition and resolving conflicts before they snowball into large-scale issues.

Staniszewska mentioned that a stable communication process should rely on sustainable feedback loops:

“ Emphasize the need for feedback mechanisms that allow individuals to assess their communication effectiveness continually. This can be formal, like surveys, or informal, like regular team check-ins .”

So, how do you create a positive feedback loop that reinforces the communication process?

You can start by:

- Leading with empathy: Emphasize to others you’re ready to hear them out without prejudice or judgment.

- Giving feedback in person: Face-to-face meetings or video calls often feel more authentic than messages and emails.

- Managing your emotions: Tap into your emotional intelligence and approach each situation with a clear mind.

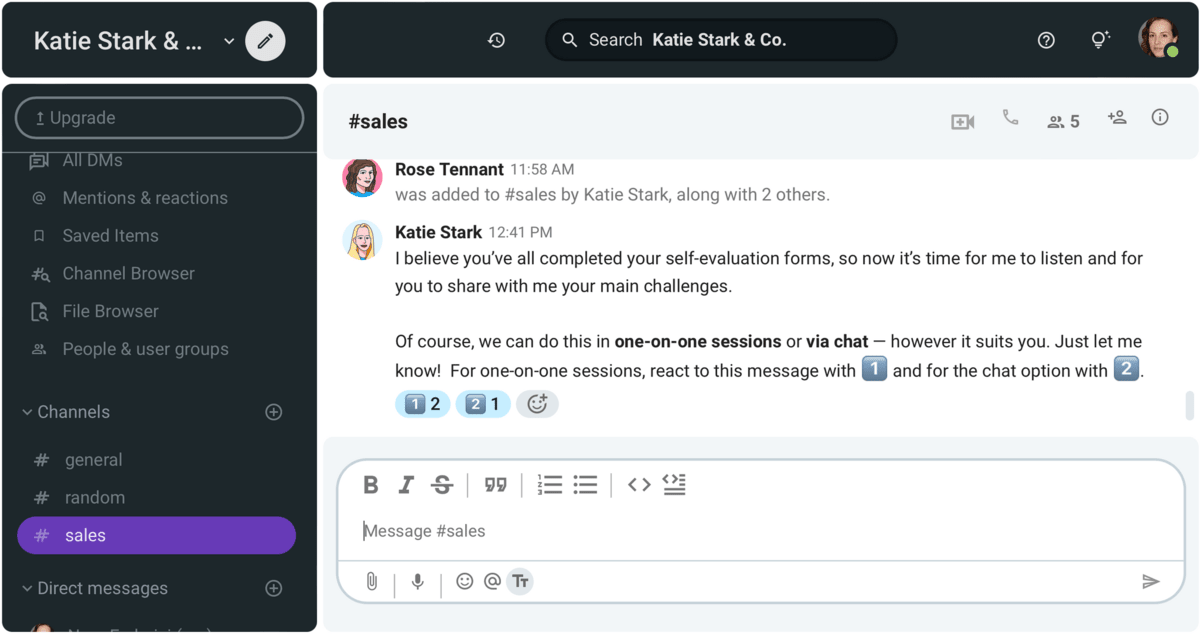

Here’s how that may look.

When eliciting feedback, remember not to rush the interaction, states Dawid Wiacek , a communication and executive career coach:

“ In today’s business landscape, speed is often a competitive advantage, but when it comes to success in communication, one of the keys is actually slowing down. To ensure the other person has digested your message accurately, it’s helpful to ask them to summarize it in their own words.

You can ask what resonated about the message and what didn’t; what they felt was the core element, and what was secondary; what was validating and perhaps surprising. The point here is you want to engage the recipient and make sure that the original message was translated appropriately and not lost in translation. ”

Tip #4: Think about where you (and others) come from

Although it can be nerve-wracking, giving feedback to colleagues is part of virtually all jobs.

Ideally, we deliver critiques in a constructive and empowering manner, but that’s not always how things pan out. That’s not to say we purposely try to offend our coworkers. The situation may simply be a result of cultural differences.

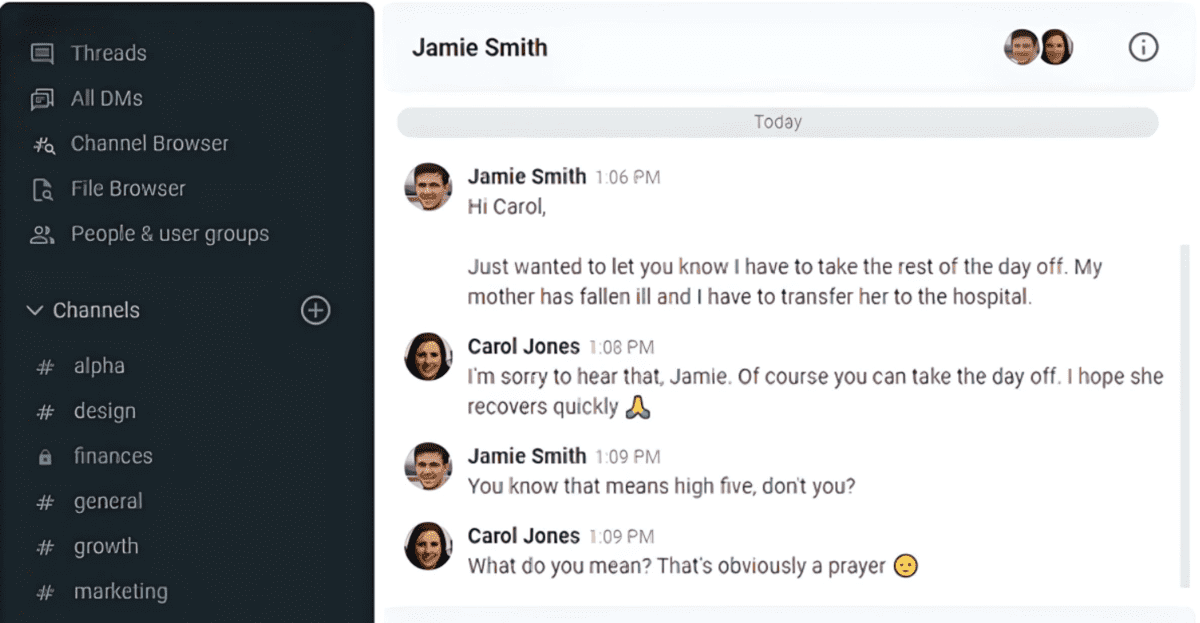

Let’s take the below exchange as an example.

Carol, who is from the US, sends her well wishes to Jamie, who has been working from Japan for the past 6 years. A minor misunderstanding arises because Carol assumed Jamie and she would interpret the meaning of an emoji in the same way.

This type of blunder can be funny — Carol and Jamie were able to clear the air quickly and move on.

But, what would happen in a more serious situation, such as a performance review?

For instance, moving a manager from Germany to take over a department in South Korea can become a disaster if no forethought goes into it. In Korean society and business, respect is determined through a mix of age, experience, and hierarchical position.

Thus, if the German manager is older than part of his Korean staff, they will be less likely to push back against unwarranted criticism. Moreover, after receiving information from the manager, they could even return disingenuous feedback in an effort to save face.

Fortunately, this doesn’t mean that all cross-cultural collaboration is doomed.

When we spoke to Joanna Staniszewska, she highlighted the importance of cultural intelligence and sensitivity:

“ Communication takes place in diverse environments. Stress the importance of cultural awareness and sensitivity. Encourage individuals to adapt their communication styles to resonate with the audience’s cultural norms and expectations. ”

Tip #5: Read up on communication styles

Understanding your preferred communication style and tweaking it to align with your coworkers can make a difference in team collaboration and communication .

When a colleague abruptly shuts down during the communication process, it might not be because of something you’ve intentionally said or done. Perhaps your personal communication style got in the way, and the person on the other end felt you were disregarding their ideas and opinions. Although you thought you were assertively standing up for your idea, your coworker may have felt like you were subtly attacking theirs.

Changing how you communicate can point you toward professional success, and a good starting point is bolstering your emotional intelligence . Through a combination of social awareness and self-awareness, you’ll gradually gain more control over how you speak and act in the workplace.

In the case that you need more guidance, another strategy would be enrolling in a professional development course that could help you become a more transparent and flexible communicator.

When a communication break occurs, it isn’t always possible to salvage the communication process. However, with the proper education and a dash of commitment, you can learn how to facilitate productive and open conversations.

For more extensive information on different communication styles, as well as becoming more flexible during business communication, check out this guide:

- Communication styles

Tip #6: Take into account the changing demographics of the workforce

Another unique issue in workplace communication is learning how to connect and collaborate with colleagues from different generations .

We all have specific habits and preferences, and the generational gap can sometimes put our behavior at odds with that of our older or younger coworkers.

Navigating these differences and refraining from resorting to stereotypes is the way to go when creating a well-connected and inclusive environment.

So, be honest about your preferred ways of communication and respect the boundaries of your team members. As soon as they notice these efforts, they’ll feel more at ease when asking for help or reaching out about a work task.

Are you interested in learning more about enhancing communication across generations within your team or company? Then check out this exhaustive blog post:

- How to improve communication across generations at work

Why is the communication process important?

Through the way we communicate, we learn not only how to get ahead in life but also how to form stable relationships.

If you think of life skills as a tower of cards, communication is near the bottom, laying a solid foundation. Should this card wobble slightly, it will jeopardize the stability of the entire tower.

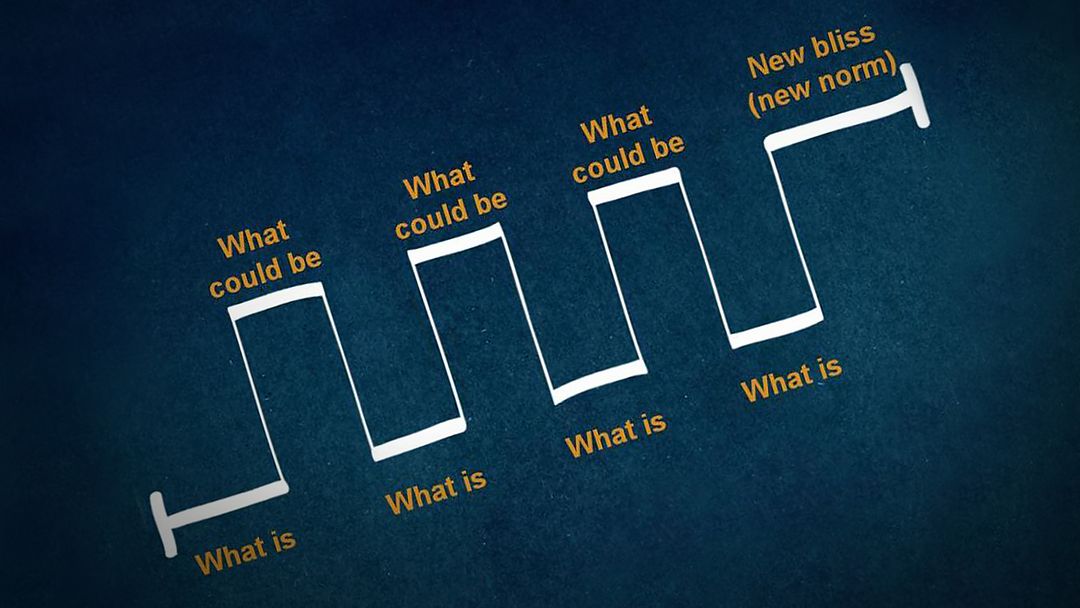

Moreover, by mastering the communication process, you :

- Readjust your self-perception and how you view the world around you ,

- Become a better learner , and

- Learn how to represent both your employer and yourself in the best light .

In the following sections, we will devote more attention to exploring the above three points.

Reason #1: The communication process affects how we view others and ourselves

The phrase “ at a loss for words ” aptly describes how it feels to come out of a communication situation unsuccessful.

Not only do you feel like you’re missing the right words, but it is as if you’re also missing a vital part of yourself. This unpleasant emotion sprouts because we share a part of our worldview with our interlocutor when communicating . We often inadvertently reveal the reasoning behind our train of thought and how we believe everything fits into this neatly organized snapshot of the world.

And, you go through the same scenario when listening to friends or coworkers. You take in their appearance, facial expressions, and words to form an assumption about what their values and priorities may be.

It’s not always feasible to pick the right words or rein in your facial expressions, but learning how the communication process works does help.

For example, you’ll realize that what you say could reveal just as much about yourself as the topic you are discussing. Thus, rather than simply waiting for your turn to speak, you might make a conscious effort to actively listen and understand the other person’s perspective.

Reason #2: The communication process affects the way we learn

In Business Communication for Success , McLean reminds anyone willing to work on their communication skills that this endeavor will require:

- Persistence, and

- Self-correction.

McLean likens becoming a better communicator to sharpening other valuable life skills. There was a time when you didn’t drive a car or have a clue about digital literacy , yet, over time (and much trial and error), you’ve become a much more capable person.

So, while results won’t come overnight, and you might get tangled up in a few difficult conversations at work , the effort is worth it. The key is to keep talking and listening. Soon enough, you may catch yourself broaching new subjects more assertively .

Reason #3: The communication process helps us put our best foot forward

When you work in a team, how you communicate can paint a positive image of both you and your coworkers . When your communication style oozes professionalism and respectfulness, reaching agreements and negotiating deals becomes much less of a hassle.

Not to mention that, paired with an excellent work ethic, strong communication is a huge plus when it comes to advancing to a leadership position. And, should you decide to change companies, sharp oral and written communication skills will significantly improve your employment prospects.

If you make a misstep while joining a new team, good communication can help you iron out any lingering issues. But, to avoid these awkward situations altogether and learn how to make a good first impression, check out the below blog post:

- How to professionally introduce yourself

Be mindful of the communication process for long-term success

Whether you want to speak more candidly with family members or reach the next level in your career, knowing what the communication process is and why it matters can give you a head start.

So, before you craft your next report or begin to lose patience with a coworker, try to:

- Remember the 8 elements of the communication process ,

- Identify your role in the communication situation , and

- Pinpoint your personal drawbacks and work on being a more thoughtful and involved conversation participant .

Not only will you see better outcomes following your exchanges with colleagues and collaborators, but you’ll find that your interactions have become more engaging and enjoyable.

References:

- Berlo, D. K. (1963). The process of communication: An introduction to theory and practice. Holt Rinehart and Winston. Retrieved September 2023 from https://archive.org/details/processofcommuni0000berl/mode/2up

- Christian, A. (2022, September 26). Why ‘digital literacy’ is now a workplace non-negotiable. BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220923-why-digital-literacy-is-now-a-workplace-non-negotiable-

- Dwyer, J. (2008). Communication in business: Strategies and skills (4th ed.). Pearson Education Australia. Retrieved September 2023 from https://archive.org/details/communicationinb0000dwye

- Guffey, M. E., & Loewy, D. (2011). Business communication: Process & product (7th ed.). South-Western.

- Leavitt, H. J., & Mueller, R. A. H. (1951). Some effects of feedback on communication. Human Relations, 4, 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675100400406

- McLean, S. (2010). Business communication for success. Flat World Knowledge.

- McLean, S. A. (2003). The basics of speech communication. Allyn and Bacon. Retrieved September 2023 from https://archive.org/details/basicsofspeechco00mcle/mode/2up

- Molinsky, A. (2014, August 7). Common Language Doesn’t Equal Common Culture. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/04/common-language-doesnt-equal-c

- Panel, E. (2021, May 27). How To Encourage Candid Employee Feedback: 14 Tips For CEOs. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2021/05/27/how-to-encourage-candid-employee-feedback-14-tips-for-ceos/?sh=2805bfec2407

Explore further

Team Communication Fundamentals

Improving Team Communication

Improving Communication Effectiveness

Additional Materials

Free team chat app

Improve collaboration and cut down on emails by moving your team communication to Pumble.

What is Communication Process: Examples, Stages & Types

Table of Contents

Communication enables us to connect, share ideas, and collaborate with one another. But have you ever wondered what exactly goes into the process of effective communication? How do our thoughts and intentions transform into meaningful messages that are understood by others?

In this blog post, we will delve into the details of the communication process. We will explore its fundamental components, examine how messages are transmitted and received, and highlight the key factors that can influence successful communication.

Definition of the communication process?

“The systematic process in which individuals interact with and through symbols to create and interpret meanings in a particular context.” – Joseph A. DeVito “The process by which people use signs, symbols, and behaviors to exchange information and create meaning.” – Kory Floyd

What is the communication process?

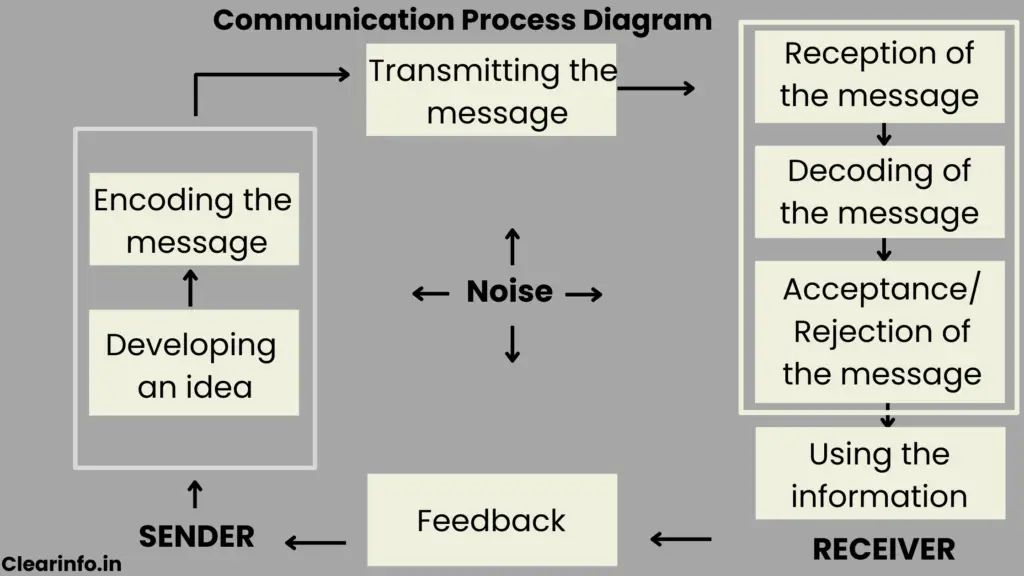

The communication process refers to the steps and elements involved in the successful transmission and understanding of a message between a sender and a receiver. It includes the exchange of information, ideas, opinions, or emotions through various channels or mediums. The communication process is cyclical, meaning it involves continuous feedback and adjustment.

Effective communication requires clarity, relevance, active listening, and consideration of the needs and perspectives of both the sender and the receiver. By understanding and utilizing the communication process, individuals and organizations can enhance their ability to convey messages, build relationships, and achieve their communication goals.

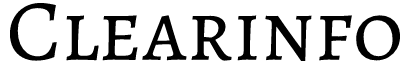

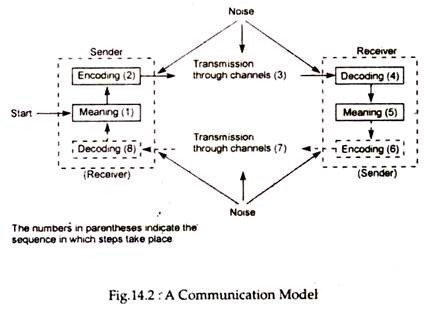

Process of communication with diagram

What is the communication process cycle?

The communication process cycle is a continuous and dynamic sequence of stages involved in the successful exchange of messages between a sender and a receiver. The communication process cycle typically includes the following phases:

- Sender’s Input

- Message Transmission

- Message Reception

- Receiver’s Response

- Feedback Transmission

- Iteration and Adjustment

The communication process cycle is continuous, as it involves ongoing interactions and exchanges between the sender and the receiver.

Distinctive characteristics of the communication process?

The following characteristics help distinguish the communication process from other forms of human interaction and highlight its unique nature. The key characteristics of the communication process are as follows:

- Sender-Receiver Relationship : The communication process involves a relationship between the sender and the receiver. It requires both parties to participate actively and engage in the exchange of messages.

- Noise Effect : The communication process can be influenced by noise, which refers to any barriers or disruptions that affect the accurate transmission or reception of the message. Noise can be physical (e.g., background noise) or psychological (e.g., cultural differences) .

Related Reading : Psychological barriers to effective communication

- Dynamic and Ongoing : Communication is a continuous process that involves ongoing interactions and exchanges between the sender and the receiver. It is not a one-time event but evolves.

- Subjectivity : The communication process is subject to interpretation and perception by both the sender and the receiver. Each individual may interpret and understand the message based on their own experiences, beliefs, and perspectives.

Components of the communication process

The communication process consists of several interconnected components that work together to facilitate effective communication.

1/ Sender: The sender takes the lead in initiating the communication process. They have a message or information to convey to the receiver. The sender’s role involves encoding the message, which means converting thoughts or ideas into a communicable format.

2/ Message: The message represents the ideas or informational content that the sender intends to convey. It can be expressed through different channels, including verbal, written, or non-verbal forms. Verbal elements include spoken or written words, while non-verbal elements encompass body language, facial expressions, and gestures.

3/ Channel: The channel serves as the pathway through which the message is conveyed from the sender to the receiver. Communication channels can include face-to-face conversations, phone calls, emails, text messages, video conferencing, or social media platforms.

4/ Receiver: The receiver is the person or group of people who are the intended target of the message. They play a crucial role in the communication process by decoding and interpreting the message received from the sender.

5/ Feedback: Feedback is the response or reaction given by the receiver in relation to the sender’s message. It serves as a vital component of the communication process, allowing the sender to gauge the effectiveness of their message and make necessary adjustments.

To know more check out our detailed article on: What are the components of the communication process

Types of the communication process

Communication processes can be broadly categorized into four main types:

1/ Verbal Communication Process: Verbal communication involves the usage of spoken or written language to express and convey messages. It allows for immediate feedback and clarification, promoting interactive and real-time exchanges.

Further Reading: What is verbal communication

2/ Nonverbal Communication Process: Nonverbal communication involves the transmission of messages without the use of words. It incorporates a range of nonverbal cues such as physical movements, hand gestures, vocal intonation, interpersonal distance, and other forms of nonverbal expression.

Further Reading: What is nonverbal communication

3/ Visual Communication Process: Visual communication relies on visual elements to convey messages. It involves the use of images, graphics, charts, diagrams, videos, presentations, and other visual aids. Visual communication is effective in simplifying complex information, enhancing understanding, and appealing to visual learners.

Further Reading: What are the advantages and disadvantages of visual communication

4/ Written Communication Process: Written communication includes the utilization of written words or text as a means to convey information. It includes letters, memos, reports, articles, emails, text messages, social media posts, and other forms of written communication.

Further Reading: What is written communication with example

How does the communication process work?

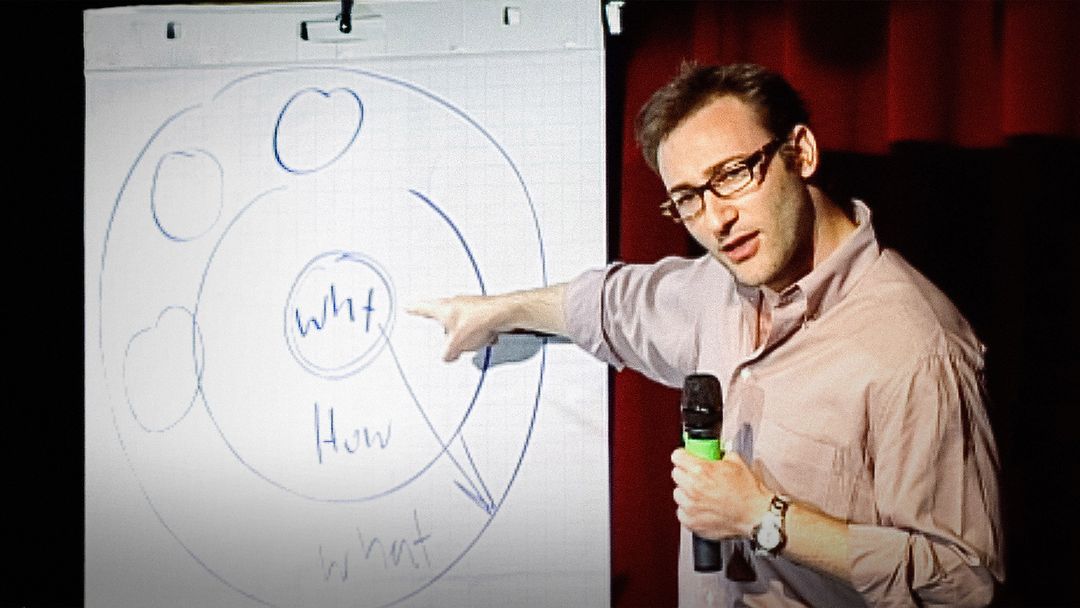

The communication process involves 8 interconnected stages that facilitate the exchange of information, ideas, or messages between a sender and a receiver. Here’s a simplified explanation of how the communication process works:

8 stages of the communication process

1/ Sender’s Input: The communication process begins with the sender, who initiates the communication by having a message to convey. The sender identifies the purpose of the communication and formulates the message accordingly. This involves determining what information, ideas, or emotions need to be conveyed and what outcome the sender hopes to achieve through the communication.

2/ Encoding the message: After formulating the message, the sender encodes it by selecting appropriate symbols, language, or means of expression. Encoding involves converting thoughts or ideas into a form that can be understood by the receiver. This could include:

- Selecting specific words

- Using nonverbal cues such as gestures or facial expressions

- Utilizing visual or auditory elements to enhance the message’s meaning.

3/ Message Transmission: Once the message is encoded, the sender transmits it through a chosen communication medium or channel. The medium can vary depending on the nature of the communication and the available options, such as:

- Face-to-face conversations

- Written communication

- Telephone calls or emails,

- Social media platforms

The sender selects the most suitable medium to effectively deliver the message to the receiver.

4/ Receptioning the Message: The receiver, who is the intended recipient of the message, receives the transmitted message through the selected medium or channel. The receiver perceives the message using their senses (e.g., hearing or reading) or through technological devices (e.g., listening to an audio recording or reading a text on a screen). The receiver’s attention and focus on the message play a crucial role in this stage.

5/ Decoding the Message: Upon receiving the message, the receiver decodes it by interpreting and extracting meaning from the information received. Decoding involves understanding the encoded symbols, language, or context used by the sender to derive the intended message. The receiver applies their knowledge, experiences, cultural background, and perceptual filters to make sense of the message and derive meaning from it.

6/ Receiver’s Response: After decoding the message, the receiver formulates a response or feedback based on their understanding and interpretation. This response can take various forms, such as verbal or written communication, actions, or nonverbal cues. The response allows the receiver to provide:

- Seek clarification,

- Ask questions,

- Express agreement or disagreement,

- Contribute additional information related to the message.

7/ Feedback Transmission: The receiver’s response is transmitted back to the sender through the same or a different communication medium or channel. Feedback serves as an essential component of the communication process, as it provides valuable information to the sender. It helps the sender gauge the effectiveness, understanding, and impact of the message on the receiver. Feedback allows for adjustments, clarification, and improvement of future communications, ensuring the accuracy and clarity of the message.

Related Reading : What is feedback in the communication cycle

8/ Noise: Throughout the communication process, various factors can influence the effectiveness of communication. These factors include noise, which can be

- External Noise: (e.g., Environmental distractions or technical issues)

- Internal Noise: (e.g., Preconceived notions or biases)

Noise can disrupt message transmission or reception. The communication context, such as the physical environment, cultural norms, relationship dynamics, and power dynamics between the sender and receiver, can also impact the communication process.

Example of the communication process?

Sarah, a project manager, wants to inform her team about a change in project deadlines, so she sends an email.

1/ Sender: Sarah, the project manager

- Sarah, as the project manager, is the sender of the message. She initiates communication by composing and sending emails.

2/ Message: Change in project deadlines

- The message is about the change in project deadlines. Sarah wants to inform her team members about this important update.

3/ Encoding: Composing the email

- Sarah encodes her message by composing an email. She chooses the appropriate words, tone, and structure to effectively convey the information regarding the change in project deadlines.

4/ Medium: Email

- The medium used for communication in this scenario is email. Sarah sends the message through the company’s email system.

5/ Channel: Company’s email server

- The channel refers to the means through which the message is transmitted. In this case, the email is transmitted through the company’s email server to reach the team members’ inboxes.

6/ Receivers: Sarah’s team members

- Sarah’s team members are the intended receivers of the message. They will receive and interpret the email sent by Sarah.

7/ Decoding: Reading and understanding the email

- The team members decode the email by reading it and interpreting the content. They understand that there has been a change in project deadlines based on the information provided by Sarah.

8/ Feedback: Team members’ response or clarification

- After decoding the message, the team members may provide feedback to Sarah by replying to the email. They might seek clarification, acknowledge the change, or ask questions related to the new deadlines.

9/ Noise: Distractions or communication barriers

- Noise can refer to technical issues with the email server, language barriers, or even conflicting priorities that could negatively affect the effective transmission or reception of the message.

10/ Context: Project management and deadlines

- The context of the communication is the project management and the change in deadlines. It provides the background and relevance for Sarah’s message to her team members.

The example highlights how the communication process functions within a business, specifically in the scenario of Sarah communicating changes in project deadlines to her team members via email.

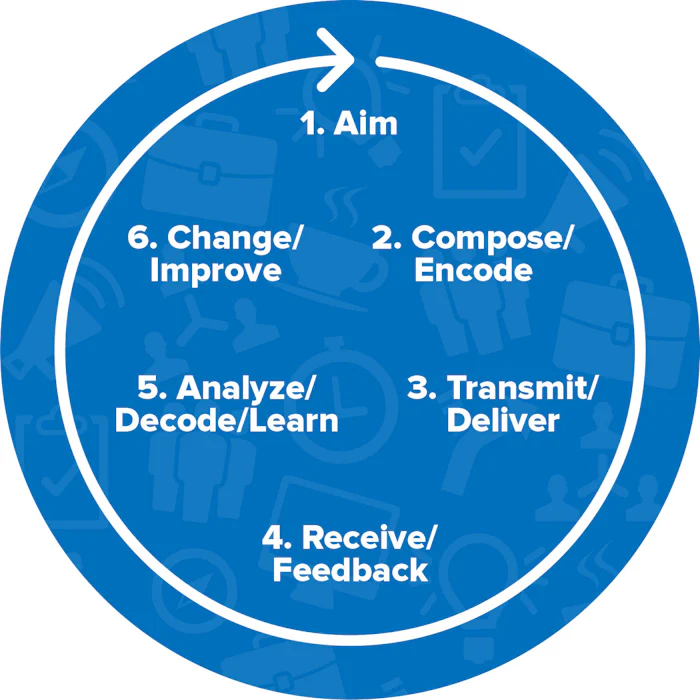

Examples of communication models:

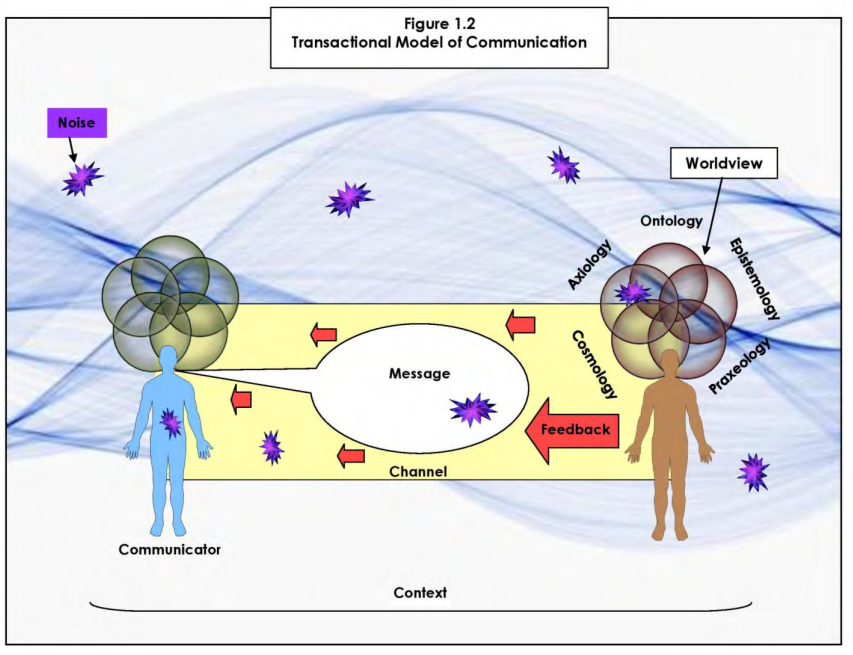

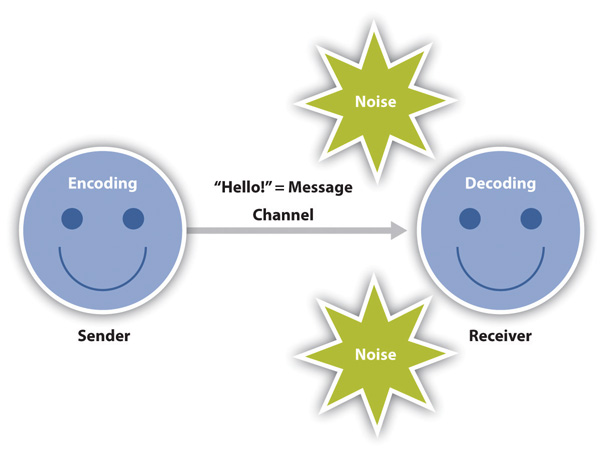

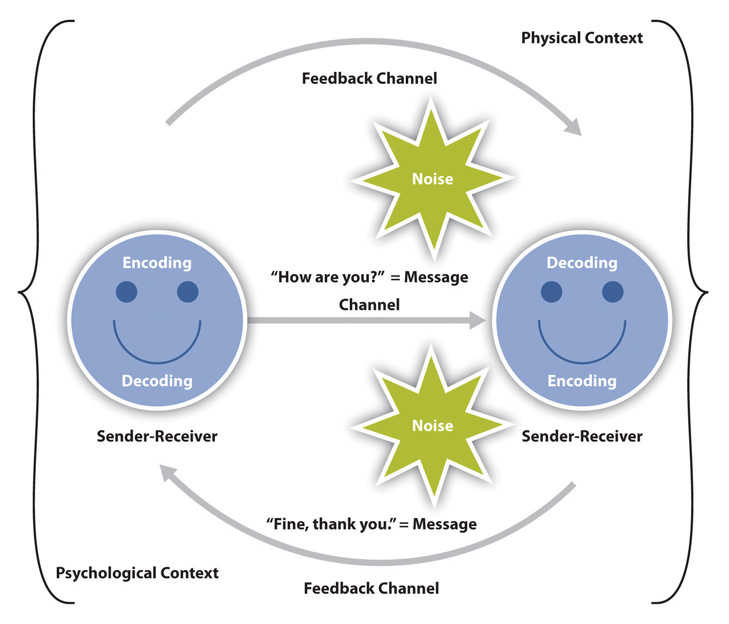

Communication models provide frameworks for understanding the complexities of the communication process. Two well-known models are the Shannon-Weaver model and the Transactional model. The Shannon-Weaver model focuses on the transmission of information from the sender to the receiver through a linear process.

The Transactional model emphasizes the dynamic nature of communication, where both the sender and receiver actively participate in encoding, decoding, and exchanging messages.

Why communication process is important?

The communication process serves as the foundation for effective and meaningful interactions between individuals, groups, and organizations. Here are some key reasons why the communication process is vital:

- Enhancing Decision-Making: Effective communication is essential for informed decision-making. Through the communication process, individuals can gather insights, weigh different options, and collectively arrive at well-informed decisions that consider multiple factors and stakeholder interests.

- Conflict Resolution: Communication plays a vital role in resolving conflicts and addressing differences. By encouraging open dialogue, active listening, and empathy, the communication process allows individuals to express their concerns, and find mutually acceptable solutions.

- Achieving Organizational Objectives: In the organizational context, the communication process is vital for achieving goals and objectives. It ensures that employees understand the organization’s vision, mission, and strategies.

- Influencing and Persuasion: Communication is a powerful tool for influencing and persuading others. The communication process allows for the delivery of persuasive messages that can shape opinions, change behaviors, and motivate individuals or groups to take desired actions.

- Social and Cultural Cohesion: Communication is a fundamental aspect of human interaction and societal cohesion. The communication process helps bridge gaps, promote understanding across diverse cultures, and foster inclusive and harmonious relationships within communities and societies.

Importance of the communication process in real life?

Effective communication serves as a cornerstone for building and nurturing relationships in personal, and social life. By actively engaging in the communication process, individuals establish connections and build trust, which forms the foundation of healthy and meaningful relationships.

Moreover, the communication process provides a platform for individuals to express their thoughts, emotions, and experiences. It serves as a medium for self-expression, enabling individuals to share their perspectives and joys with others.

Additionally, engaging in the communication process contributes to personal growth and development. It enhances self-awareness and interpersonal skills. Through active participation in communication, individuals can refine their communication abilities, become more adaptable, and strengthen their relationships, both personally and professionally.

What are the common problems in the process of communication?

There are several common problems that can arise in the process of communication. These problems can hinder effective communication and lead to misunderstandings or breakdowns in the exchange of information. Here are some common communication problems:

1/ Misunderstandings : Misunderstandings can arise when the receiver does not accurately grasp the intended meaning of a message, leading to misinterpretations. This can happen due to differences in language or individual interpretations. Misunderstandings can result in misinformation and ineffective communication.

2/ Encoding and Decoding Errors: Encoding involves transforming thoughts or ideas into a communicable format, while decoding refers to the interpretation of the received message. Errors can occur during encoding or decoding, leading to misinterpretation or distortion of the intended message.

3/ Channel Selection : Choosing the appropriate communication channel is crucial for effective message transmission. Using an incorrect or inefficient channel can lead to message loss, distortion, or delayed communication. Selecting the right channel based on the nature of the message and the target audience is essential.

4/ Lack of Adaptability : Communication processes need to be adaptable to different contexts, audiences, and communication styles. Failing to adapt the communication approach can result in resistance or a lack of engagement from the intended recipients.

How does intercultural communication affect the communication process?

Intercultural communication refers to the exchange of information and ideas between individuals or groups from different cultural backgrounds. It plays a significant role in today’s globalized world where people with diverse cultural identities interact and collaborate. Intercultural communication can have a profound impact on the communication process in several ways:

- Language Barriers: Different cultures have distinct languages or variations of languages. When individuals from different cultures communicate, language barriers may arise , making it challenging to convey ideas accurately.

- Nonverbal Communication Differences: Nonverbal communication, such as eye contact and body movements can reflect cultural variations. Various cultures may attribute different interpretations to specific nonverbal cues, resulting in differences in meaning and understanding.

- Cultural Context: Cultural context significantly influences the communication process. Social norms, customs, and historical backgrounds shape how messages are constructed and interpreted. Without an understanding of the cultural context, messages may be misunderstood.

Related Reading : Cultural Barriers To Communication: Examples & How to Overcome it

Communication process in the workplace

In the workplace, the communication process refers to the series of interactions through which information, feedback, and instructions are exchanged between employees or teams to achieve common goals and facilitate effective work dynamics.

It involves both verbal and non-verbal communication , utilizing various channels and methods to ensure clear and meaningful understanding among employees and across different levels of the organization.

Communication process in advertising

In advertising, the communication process refers to the strategic and systematic approach of developing and delivering persuasive messages to target audiences with the goal of promoting products, services, or ideas. It involves a series of interconnected stages that aim to capture attention, generate interest, and elicit desired actions from the audience.

Impact of Technology on the communication process

The impact of technology on the communication process refers to the changes and transformations that technology has brought to the way people exchange information, connect with others, and engage in communication. It has revolutionized various aspects of communication, including speed, accessibility, reach, and modes of interaction. Here are some key impacts of technology on the communication process:

- Speed and Efficiency: Technology has drastically increased the speed and efficiency of communication. Messages can be sent and received instantly through various digital platforms, reducing the time required for information exchange and decision-making processes.

- Global Connectivity: The internet and digital communication technologies have facilitated global connectivity, bringing together individuals from diverse regions of the world. Geographic barriers no longer limit communication, allowing individuals to connect, collaborate, and engage with others regardless of their physical location.

- Expanded Communication Channels: Technology has expanded the range of communication channels available. In addition to face-to-face conversations, people can communicate through emails, instant messaging, video calls, social media platforms, and other digital tools. This variety of channels provides flexibility and choice in how people interact and exchange information.

In addition, the impact of technology on the communication process also comes with challenges. Misinterpretation, miscommunication, and information overload are limitations of digital communication . Balancing virtual interactions with maintaining personal connections and non-verbal cues can also be a challenge. It is important to be mindful of these challenges and adapt communication strategies accordingly.

What makes the communication process effective and ineffective?

Key factors that make the communication process effective:.

1/ Clarity: Clearly articulating ideas and messages using concise and understandable language helps ensure that the intended meaning is easily comprehended by the audience.

2/ Active Listening: Actively engaging in the communication process by attentively listening to the speaker, seeking clarification when needed, and demonstrating genuine interest in their message.

3/ Empathy and Understanding: Showing empathy towards others’ perspectives, being open-minded, and seeking to understand their viewpoints fosters a positive and inclusive communication environment.

4/ Feedback and Confirmation: Providing feedback to the speaker to confirm understanding, asking questions, and actively seeking clarification when necessary to ensure accurate comprehension.

5/ Contextual Awareness: Being mindful of the context and situation in which the communication takes place, including cultural norms, social dynamics, and any relevant background information.

6/ Timeliness: Communicating information in a timely manner, providing updates and responses promptly, and avoiding unnecessary delays to maintain the relevance and effectiveness of the communication .

By incorporating these factors into the communication process, individuals can enhance their ability to convey messages clearly and promote meaningful and effective interactions.

Key factors that can make the communication process ineffective:

1/ Non-Verbal Inconsistency: Sending conflicting non-verbal cues, such as mismatched facial expressions or body language, can create confusion and mistrust.

2/ Information Overload: Overwhelming the audience with excessive or irrelevant information can lead to disengagement and hinder understanding.

3/ Assumptions and Stereotyping: Making assumptions about others’ knowledge, beliefs, or experiences based on stereotypes can lead to miscommunication and misunderstandings.

4/ Emotional Barriers: Allowing strong emotions, such as anger, frustration, or fear, to dominate the communication process can prevent effective dialogue and problem-solving.

Awareness of these factors can help individuals identify and address potential barriers to effective communication and fostering productive interactions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1) what are the 7 steps of the communication process .

Ans: The communication process involves seven key steps: sender, message, channel, encoding, decoding, receiver, and feedback. The sender initiates the process by encoding a message, which is transmitted through a chosen channel. The receiver decodes the message and provides feedback, completing the communication loop. Following these steps enhances communication effectiveness.

Q2) What are the 5 stages of communication?

Ans: The communication process involves five stages: sender, message, channel, receiver, and feedback. The sender encodes and delivers the message through a chosen channel, which is then received, decoded, and responded to by the receiver.

Q3) What is most important in the communication process?

Ans: The most important aspects of effective communication are clarity and active listening. Clarity involves using clear and concise language, while active listening refers to actively engaging with the speaker during a conversation or communication exchange. Other important elements include feedback, non-verbal communication, empathy, emotional intelligence, and adaptability.

Q4) What are the basics of the communication process?

Ans: The basics of the communication process include a sender who encodes a clear message, a chosen channel for transmission, an engaged receiver who decodes the message, and feedback for effective communication. Minimizing noise and considering the context is important.

Q5) What is a two-way communication process?

Share your read share this content.

- Opens in a new window

Aditya Soni

You might also like.

What is Two-way Communication: Examples, Elements & Importance

8 Types of Non-Verbal Communication With Examples & Competences

Interpersonal Barriers to Communication: Examples & Solutions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: The Speech Communication Process

The Speech Communication Process

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Prepare a Presentation on Communication?

Complication of Data and Information for helping you to prepare a presentation on Communication! After reading this article we will learn about:- 1. Communicating among People 2. Importance and Meaning of Communication 3. Process 4. Model 5. Behavioural Processes 6. Networks in Organisations 7. Communication in Groups 8. Managing the Communication Process 9. Organisational Actions and Other Details .

- Media and Communication

1. Communicating among People:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

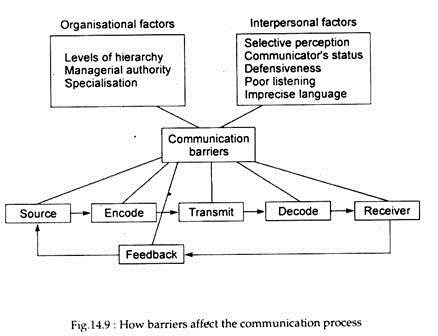

Communicating among people is not an easy task as it may appear to a layman. Thus, for managers to be able to communicate effectively, they must understand certain fundamental aspects of the communication process, i.e., how interpersonal factors such as perception, communication channels, nonverbal behaviour, and listening — all work to enhance or detract from communication.

1. Perception and Communication,

2. Communication Channels,

3. Nonverbal Communication, and

4. Listening.

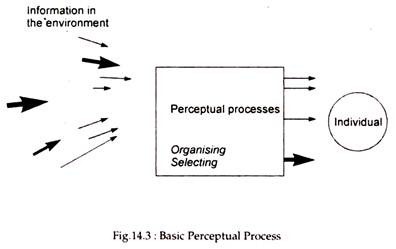

1. Perception and Communication:

Perception refers to the process one uses to make sense out of the environment. However, perception in itself often fails to give us an accurate picture of the environment. Perpetual selectivity refers to the process by which various objects and stimuli that vie for our attention are screened and selected by individuals. Certain stimuli fail to catch our attention but others do.

Once individuals recognize a stimulus, they organize or categorise it according to their frame of reference, that is, perceptual organisation. We just need a partial one to enable perceptual organisation to take place. For example, anybody can spot an old friend from a long distance and, without seeing the face or other features, recognize the person from the body movement.

The most common form of perceptual organisation is stereo-typing. A stereotype is “a widely held generalisation about a group of people that assigns attributes to them solely on the basis of one or a few categories, such as age, race, or, occupation.” For instance, young men usually assume that old people have a conservative outlook. Students may stereotype professors of philosophy as absent-minded.

What is of importance to managers is that they should be aware of the fact that words can mean different things to different people and should not assume that they already know what the other person or the communication is about.

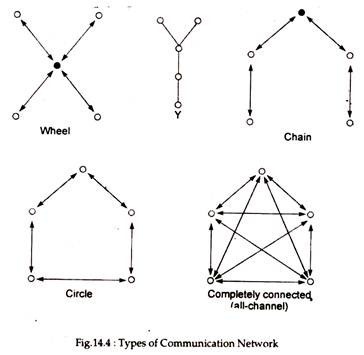

2. Communication Channels:

Managers have a choice of many channels through which to communicate to others (both managers or employees). A manager may discuss a problem face to face, use the telephone, write a memo or letter, or put an item in a newsletter, depending on the nature of the management. In truth, channels differ in their capacity to convey information.

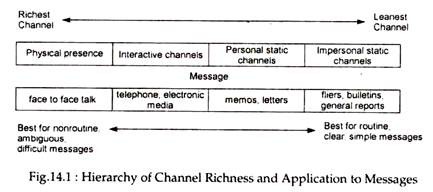

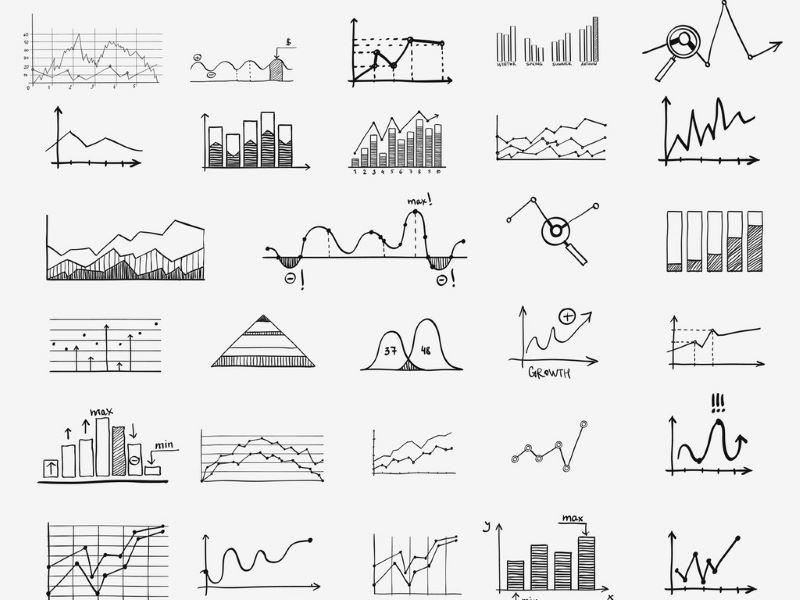

To be more specific, the physical characteristics of a channel limit the type and quantum of information that can be conveyed among managers. The channels available to managers can be classified into a hierarchy based on information richness. Channel richness refers to the quantum of information that can be transmitted during a communication episode. Figure 14.1 illustrates the hierarchy of channel richness.

The capacity of an information channel is influenced by three characteristics:

(1) The ability to handle multiple cues simultaneously;

(2) The ability to facilitate rapid feedback; and

(3) The ability to establish a personal focus for the communication.

On the contrary, interpersonal written media, including fliers, bulletins and computer reports, are the lowest in richness.

Channel selection also depends on whether the message is routine or non-routine. There is no misinterpretation in case of routine messages because they convey data or statistics or simply put into words what managers already agree on and understand. This explains why routine messages can be efficiently communicated through a channel lower in richness.

In a word, routing messages are simple and straightforward. On the contrary, non-routine messages typically are ambiguous, concern novel events, and have great potential for misunderstanding. These are often characterised by time pressure and surprise. It is possible for managers to communicate non-routine messages effectively only by selecting rich channels.

3. Nonverbal Communication:

Such communication refers to messages sent through human actions and behaviours (such as body movements, facial expressions, posture, or dress) rather than through words. It represents a major portion of the messages we send or receive.

Nonverbal communication occurs mostly face to face. So far three sources of communication cues during face-to-face communication have been discovered: the verbal, which are the actual spoken words, the vocal which include the pitch, tone, and timbre of a person’s voice; and facial expressions.

R. L. Dafts has rightly suggested that “managers should pay close attention to non-verbal behaviour when communicating. They must learn to coordinate their verbal and non-verbal messages and at the same time be sensitive to what their peers, subordinates and supervisors are saying nonverbally.”

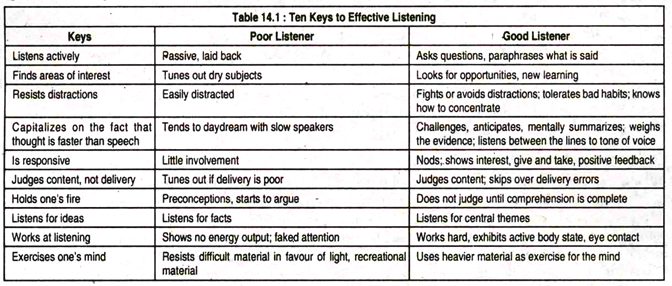

4. Listening:

The last important characteristic associated with successful interpersonal communication is listening. A good listener must have certain qualities: he has to find areas of interest, be flexible, work hard at listening and use thought speed to mentally summarise, weigh, and anticipate what the speaker will say. Table 14.1 illustrates a number of ways to distinguish a bad from a good listener.

The listener is responsible for message reception, which is no doubt a vital link in the communication process. The listener must actively seek to grasp facts and feelings and interpret the genuine meaning of the message. Only at this stage can the receiver provide the feedback with which to complete the communication circuit. Listening requires at least 3 things: attention, energy and skill.

Most U.S. multinational firms take listening very seriously. Managers are made to know that they are expected to listen to employees.

2. Importance and Meaning of Communication :

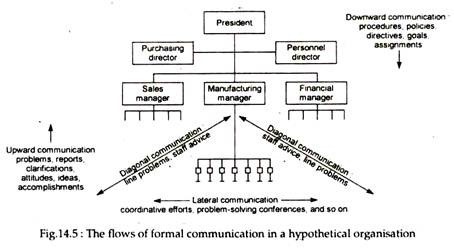

Communication permeates every organisational (managerial) function. It is a problem that plagues many organisations and individual managers. When for instance, managers perform the planning function, they collect information, write letters, memos, and reports, and then meet with other managers to explain the nature of the plan.

When managers act as leaders, they communicate with subordinates with a view to motivating them to accomplish certain tasks. In performing the organising function, managers gather necessary information about the state of the organisation and communicate to others about a new organisational structure.

Thus there is hardly any need to emphasise that communication skills are a basic part of any managerial function (activity). Communication is just a managerial tool designed to accomplish objectives and should not be treated as an end in itself.

In a particular day, the manager performs various tasks — attending meetings, making and receiving telephone calls and correspondence. Ail are a necessary part of a every manager’s job and all clearly involve communication.

The various roles of managers involve a great deal of communication. The three major types of managerial roles of interpersonal, decisions and informational. The interpersonal roles involve interacting with supervisors, subordinates, peers and others outside the organisation.

The decisional roles require that managers seek out information to use in making decisions and then communicate those decisions to others. The informational roles obviously involve communication; they focus specifically on acquiring and transmitting information.

Communication also relates directly to the basic management functions of planning, organising, leading and controlling.

As Griffin has summed up the whole thing in the following words:

“Environmental scanning, integrating, planning time horizons and decision-making, for example, all necessitate communication. Delegation, coordination and organisation change and development also contain communication. Developing reward systems and interacting with subordinates as a part of leading function would be impossible without some form of communication. And, communication is essential to establishing standards, monitoring performance and taking corrective actions as a part of control”.