Exploring phenomenological interviews: questions, lessons learned and perspectives

- Published: 06 January 2022

- Volume 21 , pages 1–7, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Svetlana Sholokhova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9427-3912 1 ,

- Valeria Bizzari 2 &

- Thomas Fuchs 3

2882 Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Doerr-Zegers, O., & Stanghellini, G. (2013). Clinical phenomenology and its psychotherapeutic consequences. Journal of Psychopathology, 19 , 228–233.

Google Scholar

Fuchs, T. (2007). Psychotherapy of the lived space. A phenomenological and ecological concept. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61 (4), 423–439.

Article Google Scholar

Høffding, S., & Martiny, K. (2015). Framing a phenomenological interview: What, why and how. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 15 (4), 539–564.

Murakami, Y. (2020). Phenomenological analysis of a Japanese professional caregiver specialized in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroethics, 13 (2), 181–191.

Nordgaard, J., Sass, L., & Parnas, J. (2012). The psychiatric interview: Validity, structure, and subjectivity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 263 (4), 353–364.

Pallagrosi, M., Fonzi, L., Picardi, A., & Biondi, M. (2014). Assessing clinician's subjective experience during interaction with patients. Psychopathology, 47 (2), 111–118.

Parnas, J., Moeller, P., Kircher, T., Thalbitzer, J., Jansson, L., Handest, P., & Zahavi, D. (2005). Examination of anomalous self-experience. Psychopathology, 38 (5), 236–258.

Parnas, J., Sass, L., & Zahavi, D. (2011). Phenomenology and psychopathology. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 18 , 37–39.

Parnas, J., Sass, L., & Zahavi, D. (2012). Rediscovering psychopathology: The epistemology and phenomenology of the psychiatric object. Schizophrenia Bullettin, 39 (2), 270–277.

Petitmengin, C., Remillieux, A., & Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C. (2018). Discovering the structures of lived experience. Towards a micro-phenomenological analysis method. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 18 (4), 691–730.

Rasmussen, A. R., Stephensen, H., & Parnas, J. (2018). EAFI: Examination of anomalous fantasy and imagination. Psychopathology, 51 (3), 1–11.

Reddy, V. (2008). How infants know minds . Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Sass, L. (2010). Phenomenology as description and as explanation: The case of schizophrenia. In S. Gallagher & D. Schmiking (Eds.), Handbook of phenomenology and cognitive science (pp. 635–665). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Sass, L. (2014). Explanation and description in phenomenological psychopathology. Journal of Psychopathology, 20 , 366–376.

Sass, L., Pienkos, E., Skodlar, B., Stanghellini, G., Fuchs, T., Parnas, J., & Jones, N. (2017). EAWE: Examination of anomalous world experience. Psychopathology, 50 (1), 10–54.

Stanghellini, G. & Aragona, M. (2016). An experiential approach to psychopathology. What is like to suffer from mental disorders?, springer.

Stanghellini, G., Broome, M., Raballo, A., Fernandez, A. V., Fusar-Poli, A., & Rosfort, R. (2019). The Oxford handbook of phenomenological psychopathology . Oxford University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgments

Valeria Bizzari wishes to thank the Center for Psychosocial Medicine, Department of Psychiatry of the Clinic University of Heidelberg, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation and the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) for the financial support (project 3H200042).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Alliance Nationale des Mutualités chrétiennes, Brussels, Belgium

Svetlana Sholokhova

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Valeria Bizzari

Department of General Psychiatry, Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Thomas Fuchs

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Svetlana Sholokhova .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sholokhova, S., Bizzari, V. & Fuchs, T. Exploring phenomenological interviews: questions, lessons learned and perspectives. Phenom Cogn Sci 21 , 1–7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-021-09799-y

Download citation

Accepted : 20 December 2021

Published : 06 January 2022

Issue Date : February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-021-09799-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19.4 Phenomenology

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with phenomenological design

- Determine when a phenomenological study design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of phenomenology research?

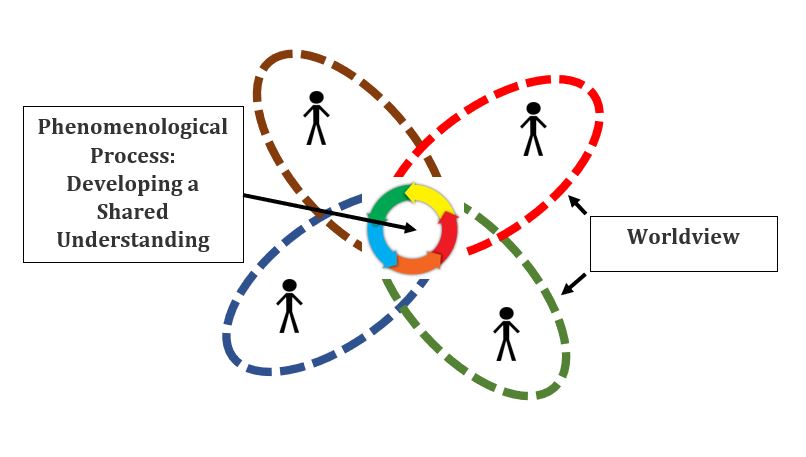

Phenomenology is concerned with capturing and describing the lived experience of some event or “phenomenon” for a group of people. One of the major assumptions in this vein of research is that we all experience and interpret our encounters with the world around us. Furthermore, we interpret these experiences from our own unique worldview, shaped by our beliefs, values and previous encounters. We then go on to attach our own meaning to them. By studying the meaning that people attach to their experiences, phenomenologists hope to understand these experiences in much richer detail. Ideally, this allows them to translate a unidimensional idea that they are studying into a multidimensional understanding that reflects the complex and dynamic ways we experience and interpret our world.

As an example, perhaps we want to study the experience of being a student in a social work research class, something you might have some first-hand knowledge with. Putting yourself into the role of a participant in this study, each of you has a unique perspective coming into the class. Maybe some of you are excited by school and find classes enjoyable; others may find classes boring. Some may find learning challenging, especially with traditional instructional methods; while others find it easy to digest materials and understand new ideas. You may have heard from your friends, who took this class last year, that research is hard and the professor is evil; while the student sitting next to you has a mother who is a researcher and they are looking forward to developing a better understanding of what she does. The lens through which you interpret your experiences in the class will likely shape the meaning you attach to it, and no two students will have the exact same experience, even though you all share in the phenomenon—the class itself. As a phenomenologist, I would want to try to capture how various students experienced the class. I might explore topics like: what did you think about the class, what feelings were associated with the class as a whole or different aspects of the class, what aspects of the class impacted you and how, etc. I would likely find similarities and differences across your accounts and I would seek to bring these together as themes to help more fully understand the phenomenon of being a student in a social work research class. From a more professionally practical standpoint, I would challenge you to think about your current or future clients. Which of their experiences might it be helpful for you to better understand as you are delivering services? Here are some general examples of phenomenological questions that might apply to your work:

- What does it mean to be part of an organization or a movement?

- What is it like to ask for help or seek services?

- What is it like to live with a chronic disease or condition?

- What do people go through when they experience discrimination based on some characteristic or ascribed status?

Just to recap, phenomenology assumes that…

- Each person has a unique worldview, shaped by their life experiences

- This worldview is the lens through which that person interprets and makes meaning of new phenomena or experiences

- By researching the meaning that people attach to a phenomenon and bringing individual perspectives together, we can potentially arrive at a shared understanding of that phenomenon that has more depth, detail and nuance than any one of us could possess individually.

What is involved in phenomenology research?

Again, phenomenological studies are best suited for research questions that center around understanding a number of different peoples’ experiences of particular event or condition, and the understanding that they attach to it. As such, the process of phenomenological research involves gathering, comparing, and synthesizing these subjective experiences into one more comprehensive description of the phenomenon. After reading the results of a phenomenological study, a person should walk away with a broader, more nuanced understanding of what the lived experience of the phenomenon is.

While it isn’t a hard and fast rule, you are most likely to use purposive sampling to recruit your sample for a phenomenological project. The logic behind this sampling method is pretty straightforward since you want to recruit people that have had a specific experience or been exposed to a particular phenomenon, you will intentionally or purposefully be reaching out to people that you know have had this experience. Furthermore, you may want to capture the perspectives of people with different worldviews on your topic to support developing the richest understanding of the phenomenon. Your goal is to target a range of people in your recruitment because of their unique perspectives.

For instance, let’s say that you are interested in studying the subjective experience of having a diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). We might imagine that this experience would be quite different across time periods (e.g. the 1980’s vs. the 2010’s), geographic locations (e.g. New York City vs. the Kingdom of Eswatini in southern Africa), and social group (e.g. Conservative Christian church leaders in the southern US vs. sex workers in Brazil). By using purposive sampling, we are attempting to intentionally generate a varied and diverse group of participants who all have a lived experience of the same phenomenon. Of course, a purposive recruitment approach assumes that we have a working knowledge of who has encountered the phenomenon we are studying. If we don’t have this knowledge, we may need to use other non-probability approaches, like convenience or snowball sampling. Depending on the topic you are studying and the diversity you are attempting to capture, Creswell (2013) suggests that a reasonable sample size may range from 3 -25 participants for a phenomenological study. Regardless of which sample size you choose, you will want a clear rationale that supports why you chose it.

Most often, phenomenological studies rely on interviewing. Again, the logic here is pretty clear—if we are attempting to gather people’s understanding of a certain experience, the most direct way is to ask them. We may start with relatively unstructured questions: “can you tell me about your experience with…..”, “what was it it like to….”, “what does it mean to…”. However, as our interview progresses, we are likely to develop probes and additional questions, leading to a semi-structured feel, as we seek to better understand the emerging dimensions of the topic that we are studying. Phenomenology embodies the iterative process that has been discussed; as we begin to analyze the data and detect new concept or ideas, we will integrate that into our continuing efforts at collecting new data. So let’s say that we have conducted a couple of interviews and begin coding our data. Based on these codes, we decide to add new probes to our interview guide because we want to see if future interviewees also incorporate these ideas into how they understand the phenomenon. Also, let’s say that in our tenth interview a new idea is shared by the participant. As part of this iterative process, we may go back to previous interviewees to get their thoughts about this new idea. It is not uncommon in phenomenological studies to interview participants more than once. Of course, other types of data (e.g. observations, focus groups, artifacts) are not precluded from phenomenological research, but interviewing tends to be the mainstay.

In a general sense, phenomenological data analysis is about bringing together the individual accounts of the phenomenon (most often interview transcripts) and searching for themes across these accounts to capture the essence or description of the phenomenon. This description should be one that reflects a shared understanding as well as the context in which that understanding exists. This essence will be the end result of your analysis.

To arrive at this essence, different phenomenological traditions have emerged to guide data analysis, including approaches advanced by van Manen (2016) [1] , Moustakas (1994) [2] , Polikinghorne (1989) [3] and Giorgi (2009) [4] . One of the main differences between these models is how the researcher accounts for and utilizes their influence during the research process. Just like participants, it is expected in phenomenological traditions that the researcher also possesses their own worldview. The researcher’s worldview influences all aspects of the research process and phenomenology generally encourages the researcher to account for this influence. This may be done through activities like reflexive journaling (discussed in Chapter 20 on qualitative rigor) or through bracketing (discussed in Chapter 19 on qualitative analysis), both tools helping researchers capture their own thoughts and reactions towards the data and its emerging meaning. Some of these phenomenological approaches suggest that we work to integrate the researcher’s perspective into the analysis process, like van Manen; while others suggest that we need to identify our influence so that we can set it aside as best as possible, like Moustakas (Creswell, 2013). [5] For a more detailed understanding of these approaches, please refer to the resources listed for these authors in the box below.

Key Takeaways

- Phenomenology is a qualitative research tradition that seeks to capture the lived experience of some social phenomenon across some group of participants who have direct, first-hand experience with it.

- As a phenomenological researcher, you will need to bring together individual experiences with the topic being studied, including your own, and weave them together into a shared understanding that captures the “essence” of the phenomenon for all participants.

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- As you think about the areas of social work that you are interested in, what life experiences do you need to learn more about to help develop your empathy and humility as a social work practitioner in this field of practice?

To learn more about phenomenological research

Errasti‐Ibarrondo et al. (2018). Conducting phenomenological research: Rationalizing the methods and rigour of the phenomenology of practice .

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach . Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Koopman, O. (2015). Phenomenology as a potential methodology for subjective knowing in science education research .

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Newberry, A. M. (2012). Social work and hermeneutic phenomenology .

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer.

Seymour, T. (2019, January, 30). Phenomenological qualitative research design .

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing . New York: Routledge.

For examples of phenomenological research

Curran et al. (2017). Practicing maternal virtues prematurely: The phenomenology of maternal identity in medically high-risk pregnancy .

Kang, S. K., & Kim, E. H. (2014). A phenomenological study of the lived experiences of Koreans with mental illness .

Pascal, J. (2010). Phenomenology as a research method for social work contexts: Understanding the lived experience of cancer survival .

- van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing . New York: Routledge. ↵

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer. ↵

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach . Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. ↵

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles Sage. ↵

A qualitative research design that aims to capture and describe the lived experience of some event or "phenomenon" for a group of people.

In a purposive sample, participants are intentionally or hand-selected because of their specific expertise or experience.

also called availability sampling; researcher gathers data from whatever cases happen to be convenient or available

For a snowball sample, a few initial participants are recruited and then we rely on those initial (and successive) participants to help identify additional people to recruit. We thus rely on participants connects and knowledge of the population to aid our recruitment.

An iterative approach means that after planning and once we begin collecting data, we begin analyzing as data as it is coming in. This early analysis of our (incomplete) data, then impacts our planning, ongoing data gathering and future analysis as it progresses.

Often the end result of a phenomological study, this is a description of the lived experience of the phenomenon being studied.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study

A qualitative research technique where the researcher attempts to capture and track their subjective assumptions during the research process. * note, there are other definitions of bracketing, but this is the most widely used.

Doctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Basics of Research Process

- Methodology

Phenomenological Research: Full Guide, Design and Questions

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

Phenomenological research is a qualitative research approach that focuses on exploring the subjective experiences and perspectives of individuals. Phenomenology aims to understand how people make meaning of their experiences and how they interpret the world around them.

Phenomenological research typically involves in-depth interviews or focus group discussions with individuals who have experienced a particular phenomenon or event. The data collected through these interviews or discussions are analyzed using thematic analysis.

Today, we will learn how a scholar can successfully conduct a phenomenological study and draw inferences based on individual's experiences. This information would be especially useful for those who conduct qualitative research . Well then, let’s dive into this together!

What Is Phenomenological Research: Definition

Let’s define phenomenological research notion. It is an approach that analyzes common experiences within a selected group. With it, scholars use live evidence provided by actual witnesses. It is a widespread and old approach to collecting data on certain phenomenon. People with first-hand experience provide researchers with necessary data. This way the most up-to-date and, therefore, least distorted information can be received. On the other hand, witnesses can be biased in their opinions. This, together with their lack of understanding about subject, can influence your study. This is why it is important to validate your results. If you aren’t sure how to validate the outcomes, feel free to contact our dissertation writers . They have proven experience in conducting different research studies, including phenomenology.

Phenomenological Research Methodology

You should use phenomenological research methods carefully, when writing an academic paper. Aside from chance of running into bias, you risk misplacing your results if you don't know what you're doing. Luckily, we're here to provide thesis help and explain what steps you should take if you want your work to be flawless!

- Form a target group. It is typically 10 to 20 people who have witnessed a certain event or process. They may have an inside knowledge of it.

- Systematically observe participants of this group. Take necessary notes.

- Conduct interviews, conversation or workshops with them. Ask them questions about the subject like ‘what was your experience with it?’, ‘what did it mean?’, ‘what did you feel about it?’, etc.

- Analyze the results to achieve understanding of the subject’s impact on the group. This should include measures to counter biases and preconceived assumptions about the subject.

Phenomenological Research: Pros and Cons

Phenomenological research has plenty of advantages. After all, when writing a paper, you can benefit from collecting information from live participants. So, here are some of the cons:

- This method brings unique insights and perspectives on a subject. It may help seeing it from an unexpected side.

- It also helps to form deeper understanding about a subject or event in question. Many details can be uncovered, which would not be obvious otherwise.

- It provides undistorted data first-hand.

But, of course, you can't omit some disadvantages of phenomenological research. Bias is obviously one of them, but they don't stop with it. Observe:

- Sometimes participants may find it hard to convey their experience correctly. This happens due to various factors, like language barriers.

- Organizing data and conducting analysis can be very time consuming.

- You can generalize the resulting data easily.

- Preparing a proper presentation of the results may be challenging.

Phenomenological Research: Questions With Examples

It is important to know what phenomenological research questions can be used for certain papers. Remember, that you should use a qualitative approach here. Use open-ended questions each time you talk with a participant. This way the participant could give you much more information than just ‘yes’ or ‘know’. Here are a few real examples of phenomenological research questions that have been used in academic works by term paper writers .

Phenomenological Research Questions: Examples

When you're stuck with your work, you might need some examples of phenomenological research questions. They focus on retrieving as much data as possible about a certain phenomenon. Participants are encouraged to share their experiences, feelings and emotions. This way scholars could get a deeper and more detailed view of a subject.

- What was it like, when the X event occurred?

- What were you thinking about when you first saw X?

- Can you tell me an example of encountering X?

- What could you associate X with?

- What was the X’s impact on your life/your family/your health etc.?

Phenomenological Research Examples

Do you need some real examples of phenomenological research? We'll be glad to provide them here, so you could better understand the information given above. Please note that good research topics should highlight the problem. It must also indicate the way you will collect and process data during analysis.

- Understanding the role of a teacher's personality and ability to lead by example play in the overall progress of their class. A study conducted in 6 private and public high schools of Newtown.

- Perspectives of aromatherapy in treating personality disorders among middle-aged residents of the city. A mixed methods study conducted among 3 independent focus groups in Germany, France and the UK.

- View and understanding of athletic activities' roles by college students. Their impact on overall academic success. Several focus groups have been selected for this study. They underwent both online conduct surveys and offline workshops to voice their opinions on the subject.

Phenomenological Research: Final Thoughts

Phenomenological qualitative research is crucial if you must collect data from live participants. In this article, we have examined the concept of this approach. Moreover, we explained how you can collect your data. Hopefully, this will provide you with a broader perspective about phenomenological research!

Or do tight deadlines give you a headache? Check out our paper writing services ! We’ve got a team of skilled authors with expertise in various academic fields. Our papers are well written, proofread and always delivered on time!

Frequently Asked Questions About Phenomenological Qualitative Research

1. what are the 4 various types of experiences in phenomenology.

Phenomenology studies the structure of various types of experience. It attempts to view a subject from many different angles. A good phenomenological research requires focusing on different ways the information can be retrieved from respondents. These can be: perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition. With them explained, a scholar can retrieve objective information, impressions, associations and assumptions about the subject.

3. What is the purpose of phenomenological research design?

Main goal of the phenomenological approach is highlighting the specific traits of a subject. This helps to identify phenomena through the perceptions of live participants. Phenomenological research design helps to formulate research statements. Questions must be asked so that the most informative replies could be received.

4. What is phenomenological research study?

A phenomenological research study explores what respondents have actually witnessed. It focuses on their unique experience of a subject in order to retrieve the most valuable and least distorted information about it. The study must include open-ended questions, target focus groups who will provide answers, and the tools to analyze the results.

2. What is hermeneutic phenomenology research?

Hermeneutic phenomenology research is a method often used in qualitative research in Education and other Human Sciences. It inspects deeper layers of respondents’ experiences by analyzing their interpretations and their level of comprehension of actual events, processes or objects. By viewing a person’s reply from different perspectives, researchers try to understand what is hidden beneath that.

Joe Eckel is an expert on Dissertations writing. He makes sure that each student gets precious insights on composing A-grade academic writing.

You may also like

The essential guide to developing a boomtastic semi-structured interview schedule for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research study

Written by Elena Gil-Rodriguez

Data collection for your interpretative phenomenological analysis (ipa), aka: how do i come up with some awesome interview questions.

Updated February 2022

Semi-Structured Interviews are the prince (or princess) of data collection methods for your IPA

I am well aware that many of you will be conducting semi-structured interviews (SSIs) as your data collection method for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research study. After all, it is the exemplar and the most common data collection method for this type of study.

As I have already covered developing your IPA research question (RQ) in a previous article, I will now turn my attention to constructing an effective interview schedule for your data collection.

A high-quality interview schedule (or interview guide) will give you the best chance of gathering high-quality data for your IPA

Another no-brainer but the quality of your preparation for interviewing process will really help ensure that you do not get caught in a ‘garbage in, garbage out’ situation with your data.

Firstly, make sure you have mapped out your topic area sufficiently with the extant literature and have therefore done your background research, and are clear on the gaps that you are looking to fill.

The reason for this is that it will inform what you ask in the interview and will help you avoid going over the same ground that has already been covered before in previous research.

Spend time on developing your interview schedule!

It is well worth investing the time and energy in optimising your schedule as far as is humanly possible to avoid the ‘garbage in and garbage out’ dilemma.

Practical tips for constructing your IPA interview schedule

Identify the main themes relevant to your RQ and start to develop specific questions around each theme.

Start freewriting, attempting to construct as many open-ended questions as you can.

You will eventually whittle this down to a shorter set of approximately ten questions – remember you will have lots of space for prompts and probes (see my next article on interviewing) to extend the conversation further.

So, while only having ten questions might feel anxiety-provoking, I can assure you it is more than enough if you mine the interview as much as possible by skilfully employing your prompts and probes to keep the conversation going and achieve greater depth from your participant. See this article to help with this aspect of your interview technique.

Once you have constructed your short-list of questions, check them over and ask yourself:

- Are they suitable for the topic area (e.g., are they relevant as per above)?

- Will my interview questions will help me answer my RQ?

- Is my first question broader and ‘scene setting’ to help settle my participant into the interview and develop rapport?

- Are my questions suitable for my participant group (e.g., are they worded correctly for specific groups such as young people, children, vulnerable participants etc)?

- Are they understandable (i.e., not confusing to the participant)? Do try them out on your geek-love study buddy to check comprehension and that you haven’t asked two questions in one (this is a common and very human habit)

- Can I get some broader peer feedback and take my schedule to my local IPA regional group?

- Can I organise a ‘reverse interview’ and try these questions on myself? This is where you get a buddy to interview you using your schedule so that you have some idea of how it might be to be the participant. NOTE: Doing a reverse interview can also help to reveal some of your fore conceptions as part of the hermeneutic circle and is sometimes referred to as a ‘bracketing interview’

What if the areas I am interested in are not covered by the participant in the interview?

Don’t fret!

IPA SSIs are participant-led and we are looking for their take on the phenomenon , not our take on the phenomenon.

We therefore need to allow the participant to set the parameters of the topic area and describe their experience, not what you assume their experience is .

You never know, you might uncover something quite novel and exciting that you had not anticipated by giving them the space to lead the interview!

You can, of course, introduce your topic of interest later in the interview if the participant does not raise it themselves. In this way, you will have let them set the parameters of that experience and yet can also probe into your area of concern once they have done this on their own terms.

What resources can I access to help me develop my IPA interview schedule?

Of course, the Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009) ‘bible’ pages 59 to 62 gives a great overview of types of questions with a bucketload of examples. I encourage you to access this helpful resource.

S mith, J.A., Larkin, M., & Flowers, P. (2009) . Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research . London: Sage

In the 2022 Second Edition , Chapter 4, ‘Collecting data’ is where you want to immediately head for guidance.

Braun and Clarke also have an excellent chapter on interviewing, including constructing a guide (schedule) in their wonderful 2013 text. This is also highly recommended.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners . London: Sage .

Other references that may be useful to you include:

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews . (2nd ed.) London: Sage

Warren, C.A.B. (2011). Qualitative interviewing. In J.F. Gubrium & J.A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of Interview Research (pp.83-102). London: Sage

The need to systematically develop your interviewing skills

Finally, just to mention that I obviously go into this area in a great deal of detail on my Supercharge Your Semi-Structured Interviewing workshop . I lead you by the hand through the process of constructing a high-quality interview schedule and preparing extensively for the interview process. We also spend a significant amount of time practicing interview skills in a group exercise.

I encourage you to attend one of my workshops dedicated specifically to helping you achieve the required skillset to conduct high-quality IPA interviews and therefore optimise the data that you gather for your study. You cannot make a silk purse from a sow’s ear and good quality data that achieves sufficient experiential depth is essential to make your life easier at the point of conducting your analysis.

As Professor Smith repeats, time and time again: ‘Interviewing is a critical part of the process and it can require considerable time to develop expertise’ (Smith, 2011, p. 23)

Reference: Smith, J.A. (2011). Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis. Health Psychology Review, 5 , 9-27.

This is an area that students typically struggle with, just as I did! This is why I developed my Supercharge Your Semi-Structured Interviewing workshop – to help you develop your ability in this vital area. Developing these skills and grappling with this task in your research journey are all part of the process of becoming a qualitative researcher. I encourage you to see it as such rather than a monkey on your back that is whispering doom and gloom into your ear!

Until next time!

To your research success, Elena

Copyright © 2020-24 Dr Elena Gil-Rodriguez

T hese works are protected by copyright laws and treaties around the world. Dr Elena GR grants to you a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, revocable licence to view these works, to copy and store these works and to print pages of these works for your own personal and non-commercial use. You may not reproduce in any format any part of the works without my prior written consent. Distributing this material in any form without permission violates my rights – please respect them.

The information contained in this article or any other content on this website is provided for information and guidance purposes only and is based on Dr Elena GR’s experience in teaching, conducting, and supervising IPA research projects. All such content is intended for information and guidance purposes only and is not meant to replace or supersede your supervisory advice/guidance or institutional and programme requirements, and are not intended to be the sole source of information or guidance upon which you rely for your research study. You must obtain supervisory and institutional advice before taking, or refraining from, any action on the basis of my guidance and/or content and materials. Dr Gil-Rodriguez disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed upon any of the contents of my website or associated content/materials. Finally, please note that the use of my content/materials does not guarantee any particular grade for your work.

You may also like…

Qualitative data collection in the time of coronavirus…

Updated February 2022 I had plenty of time in 2020, and indeed much of 2021, to muse on conducting qualitative...

The complete guide to online interviewing for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) or other qualitative research study: episode one

Updated February 2022 I know that I have already written a brief article about my musings on data collection in the...

Top tips and tricks for tackling online interviewing for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): episode two

Updated February 2022 After the last mammoth VC article, I am returning as promised with Episode Two. This time, I aim...

Up-level your semi-structured interview technique for your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): using prompts and probes to keep the conversation going and achieve greater depth

Updated February 2022 Following on from my article about developing a boomtastic interview schedule for your...

Privacy Overview

Phenomenology: One way to Understand the Lived Experience

8/21/17 / Matt Bruce

- Market Research

- Qualitative Research

How do workers experience returning to work after an on-the-job injury? How does a single-mother experience taking her child to the doctor? What is a tourist’s experience on his first visit to Colorado?

These research questions could all be answered by phenomenology, a research approach that describes the lived experience. While not a specific method of research, phenomenology is a series of assumptions that guide research tactics and decisions.Phenomenological research is uncommon in traditional market research, but that may be due to little awareness of it rather than its lack of utility. (However, UX research, which follows many phenomenological assumptions, is quickly gaining popularity). If you have been conducting research, but feel like you are no longer discovering anything new, then a phenomenology approach may shed some fresh insights.

Phenomenology is a qualitative research approach. It derives perspectives defined by experience and context, and the benefit of this research is a deeper and/or boarder understanding of these perspectives. To ensure perspectives are revealed, rather than prescribed, phenomenology avoids abstract concepts. The research doesn’t ask participants to justify their opinions or defend their behaviors. Rather, it investigates the respondents’ own terms in an organic way, assuming that people do not share the same interpretation of words or labels.

In market research, phenomenology is usually explored by unstructured, conversational interviews. Additional data, such as observing behavior (e.g., following a visitor’s path through a welcome center), can supplement the interviews. Interview questions typically do not ask participants to explain why they do, feel, or think something. These “why” questions can cause research participants to respond in ways that they think the researcher wants to hear, which may not be what’s in their head or heart. Instead, phenomenology researchers elicit stories from research participants by asking questions like “Can you tell me an example of when you…?” or, “What was it like when…?” This way, the researcher seeks and values context equally with the action of the experience.

The utility of this type of research may not be obvious at first. Project managers and decision makers may conclude the research project with a frustrating feeling of “now what?” This is a valid downside of phenomenological research. On the other hand, this approach has the power to make decision makers and organization leaders rethink basic assumptions and fundamental beliefs. It can reveal how reality manifests in very different ways.

A phenomenology study is not appropriate in all instances. But it is a niche option in our research arsenal that might best answer the question you are asking. As always, which research approach you use depends on your research question and how you want to use the results.

- Previous Post / Based on my experience…

- If you are traveling to watch the eclipse, be prepared / Next Post

Comments are closed.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.8(5); 2021 Sep

Designing interview guides on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children: an example from a hermeneutic phenomenological study

Sarah oerther.

1 Saint Louis University School of Nursing, St. Louis MO, USA

Associated Data

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

To develop a semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children for a hermeneutic phenomenological research study.

Hermeneutic phenomenological research approach which describes the development of an interview guide with semi‐structured questions.

Ovid MEDLINE, CIHAHL, ERIC, SCOPUS, Web of Science, JSTOR, Education Source, PsyINFO and ProQuest were searched to identify possible interview guides with questions related to stress and coping. The literature was searched in 2019 and included manuscripts from 1970–2019. An initial interview guide was constructed. Mock interviews were used to confirm the rigour of the guide.

The final outcome was a semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children.

The development of this semi‐structured interview guide is relevant to hermeneutic phenomenological researchers who are interested in discovering how personal background meanings and interpersonal concerns shape parents’ day‐to‐day stress appraisals and coping with parenting pre‐teen children.

This semi‐structured interviewing guide can be an impactful tool for researchers to use to understand how personal background meanings and interpersonal concerns shape background meanings and concerns related to stress and coping with parenting pre‐teen children.

1. INTRODUCTION

Hermeneutic phenomenological research is an established qualitative approach that is well matched to reveal self‐world relations and varied patterns and transitions in human meanings and practices (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; SmithBattle, 2018 ). Hermeneutic phenomenological research is contextual and offers a way “to study persons, events, and practices in their own terms” (Benner, 1994 , p. 99). A major premise of the approach is that humans primarily relate to the world by engaging in practical activities; that is, people learn how to act and relate to others by absorbing the meanings embedded in everyday activities (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; SmithBattle, 2018 ). Data for employing hermeneutic phenomenological research are generally collected using semi‐structured interviews with the aid of interview guides.

With semi‐structured interviews, researchers develop an a priori set of questions as an interview guide before conducting the interview, and then during the semi‐structured interview the set of questions guide, but do not dictate, the interview (SmithBattle, 2014 ). Every semi‐structured interview guide must be based on the study aims and the sampling criteria established for the study. Emerging scholars may find it difficult to develop interview guides for hermeneutic phenomenological research. This paper demonstrates the construction of a stress and coping interview guide for parenting pre‐teen children. In addition, suggestions to enhance the rigour of interview guides are also discussed.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. rene descartes.

Rene Descartes (1596—1,650), a French philosopher, believed that the universe operated similar to a machine, and if the laws of the universe could be understood, then actions of the human body could be deduced and repaired, like a machine (Berman, 1981 ). His philosophical reasoning resulted in the view that the body and mind are separate (Magee, 1987 ). Descartes was the first to depict the body as a machine, which contributed to the mechanistic view of the body (Leder, 1992 ). The living patient's body is divided into its component parts and their interactions, and viewed in a machine‐like fashion (Leder, 1984 ). This contributed to the notion in philosophy that the body and mind, the subject and the object, and the person and the world are separate and distinct entities, which came be to known as Cartesian dualism (Guignon, 1983 ).

Knowledge began to be conceptualized by some medical professionals as something that is entirely in the mind and separate from the body (Leder, 1984 ). A patient was viewed as subject, and the world, or the environment, as objective. A consequence of this reasoning was that healthcare professionals became fixated with the idea of a person as a collection of variables, such as “anxiety” or “self‐esteem,” which measured as context‐free traits to be joined according to theories that can be discovered through the scientific method (Leonard, 1989 ).

2.2. Martin Heidegger

In contrast to Descartes, Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher writing during the twentieth century, proposed that knowledge was not limited to conscious thought (McConnell‐Henry et al., 2009 ; Moran & Mooney, 2002 ). Rather, Heidegger claimed that Descartes’ focus on universal objective knowledge overlooked practical or pre‐theoretical understanding that is not held in the mind but is embedded in everyday practices (Guignon, 1983 ). For instance, when people drive a car, they are often unaware of all the embodied skills they use to drive the car (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). A skilled driver barely notices actions such as turning the steering wheel, staying in the lane or hitting the brake, even though the driver might do this almost fifty times on a trip to the store. These actions are automatic and escape the driver's conscious thought. Instead, the skilled driver's attention is usually focused on manoeuvring around other cars to get to the destination, or the driver is focused on the conversation with a passenger in the car (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ).

Heidegger's book, Being and Time , challenged the Cartesian dualism that separated the subjective from the objective, mind from body and person from world (Guignon, 1983 ). Heidegger was interested in the ontological question of what it is to be, and he focused on “being‐in‐the world” (Guignon, 1983 ). Heidegger uses the term Dasein to describe the human way of being‐in‐the world. Dasein is a German word that can be defined as existence (Guignon, 1983 ). Dasein is the human being's ordinary, pre‐theoretical understanding of being, which is reflected in the everyday activities of relating to others and skilful coping (Dreyfus, 1991 ; Guignon, 1983 ; Moran, 2000 ).

For Heidegger, people are thrown into a shared world as members of a particular culture, community and family. Those shared understandings and practices situate them in the world in specific ways (Dreyfus, 1991 ). For instance, it is expected that parents’ experiences of raising pre‐teen children are implicit in their everyday parenting practices and that these experiences shape their day‐to‐day appraisals of stress and situate them in the world (Benner, 1994 ; Packer & Addison, 1989 ). Their parenting practices can only be articulated by considering their past background experiences as members of specific cultures, communities and families. For researchers to understand parents and discover meaning, they must understand how parents of pre‐teen children are constituted by their world and family relationships (Benner, 1994 ).

According to Heidegger, there are three modes of “being‐in‐the world”: ready‐to‐hand, unready‐to‐hand and present‐at‐hand (Dreyfus, 1991 ). In the ready‐to‐hand mode, everyday skills and practices are familiar to people as they are actively absorbed in everyday activities. As people engage in activities with expertise, the tools they use become transparent and their bodies act skilfully without conscious thought (Guignon, 1983 ; Packer & Addison, 1989 ). This skilful coping is taken for granted because it is pre‐reflexive (Leonard, 1989 ; Magee, 1987 ). For instance, the bodily experience of driving a car passes largely unnoticed for a driver with experience. This is because the driver does not have to purposefully think about all of the bodily actions (e.g. steering the wheel or braking) as long as everything is running smoothly (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). The same is thought to be true when parents and pre‐teen children remain connected and have a healthy relationship; everyday activities run smoothly and interactions become transparent (Benner, 1994 ; Guignon, 1983 ; Packer & Addison, 1989 ).

The unready‐to‐hand mode of engagement occurs when a dilemma or breakdown interrupts practical, pre‐reflexive, smoothly running everyday activities. When this occurs, the surrounding conditions that constitute the world come explicitly into view and people become aware of the breakdown (Guignon, 1983 ; Packer & Addison, 1989 ). A good way to describe this mode of being is switching from driving an automatic car to a stick shift. An experienced driver of an automatic car might have been driving for many years, so their actions are essentially taken for granted and are often outside the realm of conscious thought. However, suddenly the experienced driver now needs to reflect on all the skills needed to drive the car, such as applying pressure to the gas pedal, pressing down the clutch, and changing gears and then releasing the clutch to reengage the drive. Suddenly, driving becomes a very “cognitive” task, and they start to consider when and how to adjust their driving speed, change gears and break. Basically, driving an automatic car was so automatic that it was often barely noticed; driving only appeared in a conscious way in learning to use a stick shift (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). Similarly, if a parent loses a job, becomes depressed and is unable to fully participate in everyday activities with their pre‐teen child, parent–child interactions may be interrupted and may become problematic (Benner, 1994 ).

Present‐at‐hand is when a person detaches themselves from the situation to find a solution. Present‐at‐hand is also any experience in which skilful coping is no longer possible, and it forces people to switch to deliberate attention. Implicit action becomes explicit. A person becomes like a scientist observing an experiment and disengages from the dilemma to find a solution. For instance, present‐at‐hand is the way a scientist would examine the characteristics and properties of a rock, measuring its mass and size. It is the mode of staring at something without engagement (Guignon, 1983 ; Packer & Addison, 1989 ). Scientists also approach parenting in the present‐at‐hand mode by identifying and measuring variables and their interactions separate from parents’ interpretations and contexts.

Seeking to understand everyday practices and modes of being helps to disclose the shared world and makes it possible to understand what Heidegger calls "the clearing" (Guignon, 1983 ; Moran & Mooney, 2002 ). World‐disclosing, or the clearing, is an interpretation or understanding made possible only through a shared background understanding (Guignon, 1983 ; Moran & Mooney, 2002 ). Parents learn to skilfully cope with the many stressors and challenges they face as parents based on the background meanings, or practical understandings, of being‐in‐the world as, for instance, residents of a rural community.

2.3. Stress and coping

The Lazarus Stress and Coping Paradigm is the framework for designing this semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children. The Lazarus Stress and Coping Paradigm views stress as residing not in the person or the event but in their interaction (Lazarus & Launier, 1978 ). Stress can be defined as a person's grasp of the meaning of circumstances for the self when that meaning overloads or surpasses normal adaptive resources (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). The response to stress interrupts practical, smoothly running everyday activities. Coping can be defined as what a person does in response to the disruption (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). This paradigm permits meanings to be identified without transforming them into discrete variables that would destroy the meaning of the situation. This paradigm is complementary to a hermeneutic phenomenological research approach because “stress” and “coping” refer to the dynamic relationship between the person and the world.

Caring for pre‐teen children sets up what counts as stressful for parents and what coping options are available for parents. Parenting stress can be defined as difficulties with the concerns surrounding the parenting role, which were meaning‐dependent and context‐dependent (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984 ; Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). Coping is integral to the parenting experience and the understanding of the parents’ stress, and consequently may transform the original understanding of situations and their concerns. Parental coping can be defined as what is effective for parents to do and is understood as what parents actually do in the situation, including new skills and meanings that parents learned from different situations (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ).

3. CONSTRUCTING QUESTIONS

Since the Age of Reason, during the 17th and 18th centuries, stories have been dismissed as unscientific and have been discounted as a methodological tool because formal reasoning has been elevated as valid knowledge at the cost of practical rationality (Mishler, 1986 ). Yet stories continue to be an essential foundation for understanding. For instance, reading a story opens up the world of the narrator, full of the possibilities, concerns, intentions, contradictions, options and impossibilities given in the world of that person. The first‐person account of a story offers an inside‐out viewpoint vital to grasping the terms in which people perceive their life and revealing people's self‐understandings, as well the background conditions that situate activities and contextualize the person (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; Mishler, 1986 ). Stories from parents of pre‐teen children can recover what formal theories necessarily overlook; namely, how parents of pre‐teen children are social and historical beings.

What distinguishes a hermeneutic phenomenological semi‐structured interview guide from alternatives such as quantitative surveys is the researcher's approach to interviewing diverges in style and form from quantitative interviewing techniques. For example, quantitative surveys are generally carried in a consistent manner to allow the comparison of cases according to a normative structure. The detached style of a quantitative survey and the power of the quantitative researcher to exclusively define legitimate questions and responses that are characteristic of a quantitative survey generally have the practical effect of discouraging contextualized, narrative accounts or stories (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; Mishler, 1986 ). Standardized quantitative surveys with predetermined and extremely focused lines of questioning limit the essential dialogue, restricting the work of understanding that is the purpose of hermeneutic phenomenological research.

The hermeneutic phenomenological research stance assumes that the study participants’ background meanings provide the basis for understanding. For instance, a parent of a pre‐teen child may take up meanings that are embedded in particular skills and practices of parenting without ever being aware of those meanings. If a parent loses a job, becomes depressed and is unable to fully participate in everyday activities with their pre‐teen child, parent–child interactions may be interrupted and may become problematic (Benner, 1994 ). Meanings such as these are inherent in parenting practices; they are best studied by examining actual events through stories (SmithBattle, 2014 ).

Hermeneutic phenomenological research offers a view of the person that is profoundly different from more traditional quantitative notions that are inherently Cartesian. It offers emerging scholars the opportunity to understand the meaningfully rich and complex lived world of those parents of pre‐teen children for whom they care (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; Mishler, 1986 ). Semi‐structured interview guide questions seek to elicit stories from, for instance, parents of pre‐teen children that reveal the context within which parents and pre‐teen children act, demonstrating how meanings are lived out on the background of shared understandings that develop within a socio‐cultural tradition.

Creating a semi‐structured interview guide for a study employing hermeneutic phenomenological research is an iterative process (SmithBattle, 2014 ). In a hermeneutic phenomenological research study, the semi‐structured interview guide should encapsulate the aims of what the researcher is trying to reveal, or the ontological, epistemological and methodological stance of the researcher's study (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ). “Research questions embed the values, world view, and direction of an inquiry. They also are influential in determining what type of knowledge is going to be generated” (Trede & Higgs, 2009 , p. 18). For instance, Phinny ( 2000 ) used hermeneutic phenomenological research to examine how people with dementia understand their illness and how their lives changed as a result of dementia.

3.1. Stage 1: Identifying the research aims

For much of modern history, medical professionals’ mechanical lens for seeing parents has been used to develop theories on parenting stress and objective resources for coping, using a deductive thought process. Theorists on parenting often treat the parent and child in a machine‐like fashion, and reduce them down to their interactions. This focus on the mechanical constructs and interactions of parents and pre‐teen children, such as parental involvement, engagement, accessibility and responsibility, without understanding the concerns of parents as shaped by context, limits understanding of the world of pre‐teen parents. For example, parenthood not only generates stressors that derive directly from parenting and the parent/pre‐teen child relationship, but it can also exacerbate problems or produce new stressors, such as stress from long‐term illness, occupational stress and financial stress, which may result in parental stress that can have effects on a parent's ability to care for their pre‐teen children.

Experiential meanings that constituted parents’ understanding of raising pre‐teen children (eight to 12 years old) in rural communities were examined using hermeneutic phenomenology research. The researcher examined parenting practices during this developmental stage, as well as the adaptive demands of parenting and the ways parents cope with those demands. Two of the research aims for this study related to stress and coping were to:

- Uncover the challenges of parenting pre‐teen children in rural communities.

- Describe the resources that support parents in raising pre‐teen children in rural communities.

The overall goal in developing this semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children was to discover how personal background meanings and interpersonal concerns shape parents’ day‐to‐day stress appraisals and coping with parenting pre‐teen children. Additionally, the researcher decided the sample for this study would consist of a convenience sample of 16 married or cohabitating parenting dyads from a rural Midwest community with at least one pre‐teen child, born any time from 2008–2011. The researcher wanted this semi‐structured interview on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children to last approximately 60 min.

3.2. Stage 2: Literature review

After deciding on the purpose of the study and research goal(s), and determining which study participants would provide the best information to answer the research question based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, relevant literature related to stress and coping was reviewed. A medical librarian‐assisted literature search was performed through the databases Ovid MEDLINE, CIHAHL, ERIC, SCOPUS, Web of Science, JSTOR, Education Source, PsyINFO and ProQuest. The search terms included the words “hermeneutic*” or “phenomenology*” and “stress*” or “coping*” and “interview*” in the title, abstract or keywords. The literature search was conducted in 2019 and examined articles from 1 January 1970 to 30 June 2019. The search yielded 3,475 articles after duplicates were deleted. An ancestry search of the reference list of manuscripts and authors was also completed; 20 additional manuscripts were found. Inclusion criteria were studies using hermeneutic phenomenological research to evaluate stress and coping. Manuscripts were excluded if they did not include a semi‐structured interview guide (Figure 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram. Note . Search terms: “hermeneutic*” or “phenomenology*” and “stress*” or “coping*” and “interview*” Search period: January 1970 through September of 2019. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (Liberati et al., 2009 )

Unfortunately, it is uncommon for researchers to publish how they created interview guides, and it can be difficult for some emerging scholars to find good examples of semi‐structured interview guides for a hermeneutic phenomenological research study. However, some dissertations provide examples of interview guides.

Many researchers’ dissertations have constructed interview guides to investigate stress and coping. For instance, SmithBattle ( 1992 ) examined the teenager's transition to mothering as shaped by the family's caregiving practices and the mother's participation in a defining community. She examined personal and family understandings related to caring for a young mother and her child as they are expressed in actual caregiving practices and rituals, and in stress and coping incidents (SmithBattle, 1992 ). Pohlman ( 2003 ) used semi‐structured interview guides to examine the meanings, concerns and practices of fathers of pre‐term infants. Stressful aspects of their experience were located outside the NICU and involved the juggling act between work, hospital visits and home; paradoxically, work was also noted as a coping resource for fathers (Pohlman, 2003 ). Another researcher sought to identify patterns and indicators of pre‐clinical disability among older women. A hermeneutic phenomenological research approach was taken to explore embodiment, taken‐for‐granted bodily sensations and coping practices (Lorenz, 2007 ). Finally, Fyle‐Thorpe ( 2015 ) examined the experiences of low‐income, non‐resident African American fathers with regard to parenting and depression. She revealed the challenges and barriers to parenting among low‐income non‐resident African American fathers (Fyle‐Thorpe, 2015 ).

A table was constructed with types of guiding questions, including (a) warm up questions; (b) core questions; (c) probing questions; and (d) wrap up questions related to stress and coping (Table 1 ). Warm up questions do not have to directly relate to the aims of the researcher's study (although they might), but help with rapport‐building, which will put the researcher and study participant more at ease with one another, allowing the rest of the interview to progress smoothly. Core questions are more difficult or potentially embarrassing questions. The goal is to tap into study participants’ experiences and expertise. Probing questions elicit more detailed and elaborate responses to key questions. For a study employing hermeneutic phenomenological research, the more details the study participants share, the better. Finally, wrap up questions provide closure for an interview and prevent the interview from ending abruptly.

Guiding questions

The researcher made sure all questions put in the table were open ended, neutral, and clear, and avoided leading language. In addition, the researcher only included example questions that used familiar language and avoided jargon. Table 1 gives details of the types of guiding questions including warm up questions, core questions, probing questions and wrap up questions (SmithBattle, 2014 ).

3.3. Stage 3: Writing the questions

The questions for this stress and coping interview guide were based on the work of other hermeneutic phenomenological researchers (Fyle‐Thorpe, 2015 ; Lorenz, 2007 ; Pohlman, 2005 ; SmithBattle, 1992 ). An initial list of questions was developed based on Table 1 . First, warm up questions were developed (Figure (Figure2). 2 ). These questions were used to help parents feel more at ease talking about potentially stressful situations.

Stress and coping interview

Second, core questions were developed. These questions were adapted to fit the study participants, parents of pre‐teen children living in rural communities. When using a hermeneutic phenomenological research approach for an interview guide about stress and coping, it is important to remember the primary source of knowledge is everyday practical activity. The study participant's perspective is paramount and core questions need to encourage detailed stories of lived experiences. In contrast to a quantitative survey, the core questions for this semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping seek to elicit stories about specific incidents, events and situations directed at human behaviour which became the text analogue that was studied and interpreted in order to discover hidden or obscured meaning. It is also important for emerging scholars to remember that the core questions are not fixed, standardized interviews that guarantee minimal responses amenable to discrete coding, interview protocols but core questions serve as flexible guides that encourage a dialogue that provides rich, thick descriptions.

Finally, probing questions were developed to elicit more detailed stories that would provide specific examples of how personal background meanings and concerns shape parents’ day‐to‐day stress appraisals and coping with parenting pre‐teen children in rural communities. It is important for emerging scholars to remember that meaning is often hidden because it is so pervasive and so taken for granted that it goes unnoticed. Since everyday lived experiences are so taken for granted as to go unnoticed, it is often through breakdowns that the researcher achieves flashes of insight into the lived world. Therefore, probes can assist in eliciting rich, descriptive information about the research setting, study participants, and their stories of their experiences. The probing questions were developed more as suggestions that may help the study participant to elaborate a detailed story of what they actually did, thought and felt about specific situations as they evolved and with enough detail so that the context of the situation would be fully described. Emerging scholars need to remember that the relevance of the probing questions may change from study participant to study participant, and some probing questions may not be asked.

After the initial list of questions was developed, the list was reviewed for language and sequencing. This semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping begins with a warm up question. The researcher took care to make sure this was something the study participant could answer easily but that wouldn't take too long. Next, the researcher considered the flow of the interview to make sure it was logical. What issues should be asked about first? What questions should come next, and would seem more or less “natural”? The most challenging or possibly upsetting core questions were asked towards the end of the interview, after rapport had been built. The last question, or the wrap up question, was intentionally chosen to leave the study participant feeling encouraged, heard, or otherwise glad they participated in the interview (SmithBattle, 2014 ).

3.4. Stage 4: Assessing rigour

Assessing the rigour of a hermeneutic phenomenological semi‐structured interview guide requires different criteria than those for assessing the validity and reliability of a quantitative survey (Creswell, 2016 ; Streubert & Carpenter, 2011 ). The rigour of a hermeneutic phenomenological semi‐structured interview guide must be consistent with understanding human experience (Benner et al., 1996 ). The researcher promoted the rigour of this semi‐structured interview guide in several different ways. First, the researcher participated in interpretive reading groups as a way to refine, challenge and validate initial semi‐structured interview guide questions (Benner, 1994 ). Colleagues read and analysed the questions. These sessions provided insight and feedback that assisted in refining and confirming the questions (Benner, 1994 ; Morse, 2015 ).

Then, the semi‐structured interview guide was used in mock interviews and feedback was given. A mock interview is an experience that includes both professors and doctoral students who practise together and help each other refine skills for interviewing (SmithBattle, 2014 ). Conducting mock interviews allowed the researcher to make sure questions were simple and that they were not asking more than one question at a time (SmithBattle, 2014 ). Conducting mock interviews allowed the researcher to begin to understand which questions prompted the longest answers from the study participants. The researcher found some of the questions could only be answered with a few words; these questions were removed. The researcher crafted the questions so that study participants would be encouraged to answer as authentically and completely as possible. During the mock interviews, the researcher thought through alternative ways of answering a few of the questions, such as through observation. Limitations and biases of the semi‐structured interview guide questions were also discussed with the researcher's advisor. It took several mock interviews to judge the correct length of the semi‐structured interview guide.

To ensure the rigour of this semi‐structured interview guide, the researcher also considered sensitivity to context, transparency and generalizability. Sensitivity to context was established through demonstrating sensitivity to the existing literature and the socio‐cultural setting of the study when writing the interview questions (Rodgers & Cowles, 1993 ). Transparency refers to how clearly the stages of the research process are described in the write‐up (Rodgers & Cowles, 1993 ). The semi‐structured interview guide was created using a table, which established an audit trail as a way to enhance transparency. The principle of generalizability or transferability is controversial in hermeneutic phenomenological research because the goal is to provide a rich, contextualized understanding of the human experience. The principle of generalizability in hermeneutic phenomenological research reflects how well or sensitively a piece of research is conducted, and whether or not it tells the reader something clinically useful (Creswell, 2016 ; Morse, 2015 ; Rodgers & Cowles, 1993 ). To achieve generalizability, the researcher sought to create rich, high‐quality questions that would elicit descriptive information about the research setting, study participants and their experiences. This will assist future researchers in making appropriate judgements about the proximal similarity of study contexts and their own environments.

3.5. Limitations

When hermeneutic phenomenological researchers create a semi‐structured interview guide and then conduct interviews and observations, they are thrown forward from their forestructure of understanding into the experiences of their study participants (Packer & Addison, 1989 ). This process is called the hermeneutic circle. The hermeneutic circle consists of forestructure and biases (pre‐suppositions), which are positive and negative (Packer & Addison, 1989 ). As the researcher moves in this circle of understanding, the researcher begins with their biases or what they already know (from personal experience, theory, research findings) and returns as they gain an appreciation of where they began (forestructure) and where their initial understanding may confirm or diverge from their study participants’ understanding and experience (Gadamer, 1975 ). While their initial biases helped them to enter the field, study participants’ data may enlarge their understanding and eventually, the hermeneutic phenomenological researcher experiences a fusion of horizons with study participants as the researcher better understands how one's own forestructure has shaped the original aims, research questions and early interpretation of the data (Gadamer, 1975 ). Therefore, limitations and biases of the semi‐structured interview guide questions were discussed with the researcher's advisor as the semi‐structured interview guide was developed. The researcher's own forestructure was also acknowledged as the semi‐structured interview guide was developed. Acknowledging forestructure is consistent with the hermeneutic phenomenological research process (Crist & Tanner, 2003 ; Finlay, 2006 ; Morse, 2015 ).

4. DISCUSSION

The goal of this semi‐structured interview guide on stress and coping related to parenting pre‐teen children was to encourage study participants to tell stories of their experiences so that meaning in context could be captured from personal accounts of the everyday world (Mishler, 1979 ). The semi‐structured interview guide was used to initiate conversation and encourage dialogue with parents of pre‐teen children. None of the questions in this semi‐structured interview guide abstracted experience and life events from their context of the parents’ stories. Parents were asked to describe a recent difficult or challenging situation, followed by a recent meaningful episode. Careful probing questions assisted parents in elaborating their thoughts, feelings and actions in self‐selected stress and coping situations, as they occurred in context. The probing, clarifying questions changed during conversations with parents, and the interviewer sought to help them provide detailed stories of what they did, thought and felt about specific situations as they occurred. The researcher sought to elicit as much detail about their stories as possible so that the researcher could more fully understand the parents’ thoughts and actions about particular situations (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 ; Mishler, 1986 ). The researcher followed the parents’ lead in the conversations because what parents of pre‐teen children chose to talk about reflected their practical understanding of their world of parenting pre‐teen children. Language, as noted by Guignon ( 1983 ), who interpreted Heidegger's philosophy, constitutes both the understanding and situatedness of our everyday being and lays out the possibilities of grasping the world.