Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How to Empower Students to Take Action for Social Change

Young people are increasingly aware and concerned about the problems our world is confronting, from climate change to racial disparities in society. When facing social problems, how can educators transform a child’s sense of helplessness toward hope and action?

Educators must not allow our adolescents to languish in the face of social problems and injustice. In James Baldwin’s 1963 Talk to Teachers , he reminds us of this charge: “Our obligation as educators is to entrust in our students the abilities to create conscious citizens who are vocal about reexamining their society.” It is the moral imperative of public education to foster student agency to nurture an engaged citizenry.

At the Rutgers University Social-Emotional Character Development Laboratory’s Students Taking Action Together project , we have developed a social problem-solving and action strategy, PLAN, that makes it possible for teachers to transform students’ sense of hopelessness into empowerment. It allows students to investigate a particular social problem to get to the root cause, then design an action plan to challenge the dominant power structure to make change. It emphasizes considering the issue from multiple viewpoints to develop a solution that is inclusive and viable.

Below, we’ll describe the four components of PLAN and demonstrate how to use PLAN to empower students in grades 5-12 to take action. We hope these strategies can help you encourage your students to be more deeply engaged with today’s problems and inspired to take social action.

P: Create a Problem description

Problems are an inherent part of our daily lives, and one of the key problem-solving skills is the ability to define a problem.

To define a problem, students working collaboratively in groups of four or five start by reviewing background sources, such as articles, speeches, and podcast episodes, and then draft a problem description . They can discuss the following questions to frame their thinking. Not all questions will be answered, yet the discussion will guide and stretch their thinking to begin defining the problem:

- Is there a problem? How do you know?

- What is the problem?

- Who is impacted by the problem?

- What are the issues from each perspective/party involved? What is the impact on the different individuals/groups involved?

- Who is responsible for the problem? What internal and external factors might have influenced this issue?

- What is causing those responsible to use these practices?

- Who were the key people involved in making important decisions?

To illustrate this process, let’s use the example of a recent issue: Texas’s refusal of federal funding to expand health care under the Affordable Care Act for all citizens of the state. For this issue, students might write the following problem description:

Along with Texas, 13 other states have refused to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid for citizens under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). State refusals can be attributed to a variety of factors. State lawmakers fear the loss of support from voters and their political party if they accept the federal funding to expand access to health care for lower-income communities and communities of color. Public perceptions of expanding social programs and the political costs of supporting bi-partisan reform also play a role. Political obstructionism harms all citizens, causing people to go without needed medical care and perpetuating inequalities in public health.

L: Generate a List of options to solve the problem and consider the pros and cons

Organizing for change is a skill that can be taught, even though problem solving in the political arena may feel novel and uncertain for students. Stress that while there is no guarantee of a positive outcome as they tackle a problem, brainstorming effective and inclusive solutions can help stimulate deeper awareness and discussion on the need for change. According to Irving Tallman and his colleagues , this process teaches students to apply reasoning to anticipate how solutions may play out and, ultimately, arrive at an estimate of the probability of a specific result.

That’s where the second step of PLAN comes into play: listing the possible solutions and considering the optimal plan of action to pursue. Students will revisit the background sources that they consulted during step one to consider how the actual current-event problem has been addressed over time and reflect on their own solutions. We encourage you to facilitate a whole-class discussion, guided by the following questions:

- What options did the group consider to be acceptable ways to resolve the problem?

- What do you think about their solution?

- What would your solution be?

- What solution did they ultimately decide to pursue?

For example, here are some solutions that students may generate as they brainstorm around health care funding in Texas:

- Launch a letter writing campaign to Senators and Congressional representatives communicating that obstructionism of federal funding to expand health care hurts all citizens and public health.

- Develop a social media-based public service announcement about the costs of refusing federal funding to expand health care, tagging state Senators and local Congressional representatives.

- Team up with a public health advocacy organization and learn about how to support their work in key states.

Students would then weigh the pros and cons of each solution, as well as apply perspective-taking skills to consider the needs and interests of all relevant stakeholders (e.g., government officials, insurance companies, and patients) to select what they deem to be the most effective and inclusive option. In evaluating the pros and cons of all of the solutions presented above, they may determine:

- Solutions have direct routes to communicating to politicians and have a wide audience reach.

- Solutions build student’s advocacy skills and can send a clear message to lawmakers.

- Solutions enable students to rehearse the skills of correspondence, networking, and communicating their ideas and plans with outside agencies.

- Solutions require substantial time for additional research.

- In some solutions, students may not be addressing issues in the state they live.

- In the letter-writing solution, letters lack a broad reach and the identified state(s) may already be developing reasonable alternatives to accepting federal funds to expand health care access.

- The solutions will require efforts to be sustained over time and will demand additional time in or beyond the classroom to orchestrate.

This essential problem-solving skill will support students in making objective, thoughtful decisions.

A: Create an Action plan to solve the problem

After students select what they assess to be the most effective solution, they collaborate with one another to develop a specific, measurable, attainable goal and a step-by-step action plan to implement the solution. Together, researchers refer to this as the solution plan.

For example, the goal might be to develop a one-minute public service announcement about the costs of a state’s refusal to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid under the ACA.

The step-by-step solution plan should align with the goal to resolve the problem and increase positive consequences, while minimizing potential negative effects. Your students should keep the following in mind when developing their plans:

- Make steps as specific as possible.

- Consider who is responsible for implementing each step.

- Determine how long each action step will take to execute.

- Anticipate any challenges that you may face and how you will address them.

- Identify the data that you can collect to determine whether or not your action plan was successful.

Below is a sample action plan that students may develop to meet their public service announcement goal:

- Convene a group of students to conduct research on the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid and the states that have accepted federal aid and those that refused federal aid.

- Conduct research by interviewing school nurses, county health commissioners, and the state’s Department of Health for additional content.

- Collaborate with visual arts teachers and students to design and develop the video, and course-level teacher to review the video.

- Post the social media public service announcement on YouTube and share on social media, tagging the appropriate audiences.

N: Evaluate the action plan by Noticing successes

The final step of PLAN involves evaluating the success of the action plan, using the evidence collected throughout in order to notice successes. As a whole class, students consider how similar problems were solved historically, as compared to the success of their plan. They also consider aspects of the plan that went well and those that could be improved upon moving forward. Connecting to past examples of social action affirms the understanding that you don’t always get it right in the initial push for change, and that the legacy and knowledge of incomplete change is passed from one generation to the next.

A Sample Lesson

To check out how to infuse PLAN using a historic event, check out our ready-made lesson on Fredrick Douglass’s 1852 Speech: "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" .

Noticing successes is essential to instilling confidence in students to exercise their voice and choice by organizing for and taking social action. Research suggests that problem-solving skills help buffer against distress when people are experiencing stressful events in life. With PLAN, we have discovered that equipping our students with problem-solving skills is a strong predictor of student agency and social action . By teaching a deliberate social problem-solving strategy, we nurture hope that change can be made.

In her 2003 Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope , bell hooks reminds us of the transformative power to upend the dominant power structure by bridging the gap between complaining and hope and action: “When we only name the problem, when we state a complaint without a constructive focus or resolution, we take away hope. In this way critique can become merely an expression of profound cynicism, which then works to sustain dominator culture.”

It is not enough to witness and criticize injustice. Students need to learn how to overcome injustice by developing solutions and gaining a sense of empowerment and agency.

About the Authors

Lauren Fullmer

Lauren Fullmer, Ed.D. , is the math curriculum chair and middle school math teacher at the Willow School in Gladstone, NJ; instructor for The Academy for Social-Emotional Learning in Schools—a partnership between Rutgers University and St. Elizabeth University—adjunct professor at the University of Dayton’s doctoral program, and a consulting field expert for the Rutgers Social-Emotional Character Development (SECD) Lab.

Laura Bond, M.A. , has served as a K–8 curriculum supervisor in central New Jersey. She has taught 6–12 Social Studies and worked as an assistant principal at both the elementary and secondary level. Currently, she is a field consultant for Rutgers Social Emotional Character Development Lab and serves on her local board of education.

You May Also Enjoy

These Kids Are Learning How to Have Bipartisan Conversations

How to Talk about Ethical Issues in the Classroom

Three SEL Skills You Need to Discuss Race in Classrooms

How to Inspire Students to Become Better Citizens

Three Strategies for Helping Students Discuss Controversial Issues

Nine Ways to Help Students Discuss Guns and Violence

Learning to live together: How education can help fight systemic racism

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, rebecca winthrop rebecca winthrop director - center for universal education , senior fellow - global economy and development.

June 5, 2020

The protests raging across the United States in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death all call for an end to systemic racism and inequality, which have been alive and well since the very founding of the United States. There is much that needs to be done to address systemic racism from police reform to opening ladders of economic opportunity. Education too has a role to play.

The strategy of “divide and conquer” has been used for literally thousands of years to expand empires and extend control of authoritarian leaders. The military strategy of Nazi Germany was, as former Secretary of Defense James Mattis recently so eloquently reminded us, to divide and conquer, and the American response was “in unity there is strength.” This applies not only to military strategy and morale but also to the fabric of society and our ability as Americans to bridge our differences and connect with each other. It is why after World War II, a U.N. organization dedicated to education was founded, stating “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed.”

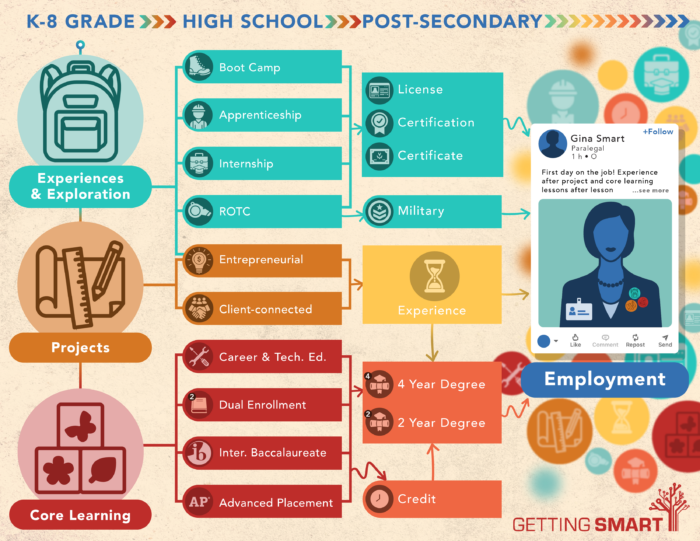

This remains true to this day and it is why education in its broadest sense must be a part of the solution to build unity across our country. Education does play a crucial role in social mobility and ensuring economic opportunity and it is why so many school districts across the U.S. are concerned with helping all young people develop academic mastery and 21st century job skills such as digital literacy, creativity, and teamwork. This is why there are such deep concerns about equity of access to quality schools and the disturbing legacy of tracking African American students into less prestigious avenues of study.

But education also plays a powerful role in shaping worldviews, connecting members of a community who might have never met before, and imagining the world we want. It is this power to shape values and beliefs that has made education susceptible to manipulation by those who want to divide and conquer (e.g., why extremists such as the Taliban in Afghanistan prioritized interfering in education as a top priority for achieving their agenda). Hence it is this power that we must turn to in an effort to fight inequality and racism. In 1996, a UNESCO global commission chaired by Jacques De Lors released a report—now affectionately known in education circles as the “ De Lors Report” —and spelled out the four purposes of education:

- Learning to know . A broad general knowledge with the opportunity to work in depth on a small number of subjects.

- Learning to do . To acquire not only occupational skills but also the competence to deal with many situations and to work in teams.

- Learning to be . To develop one’s personality and to be able to act with growing autonomy, judgment, and personal responsibility.

- Learning to live together . By developing an understanding of other people and an appreciation of interdependence.

These four purposes all remain urgent and relevant today but it is the fourth, learning to live together, that we must as a country pay more attention to. Luckily there are many in the education community that have for years been working on helping young people develop the mindsets and skills to live together. A number of organizations have long included fighting systemic racism in this effort, working tirelessly and more often than not with little visibility and recognition. Some of the best places to begin exploring this work include the nonprofit education organization Facing History, Facing Ourselves , which has been working for the past 45 years with teachers and schools across the United States to combat bigotry and hate and help build understanding across difference. Education International, a federation of the world’s teacher organizations and unions, has put forward the top 25 lessons from the teaching profession for delivering education that supports democracy for all and hence must foster inclusion and fight racism. More well-known to most Americans is Sesame Street, the children’s media organization that has for generations modeled tolerance to America’s youngest children.

On Saturday, June 6, Sesame Street and CNN will host a town-hall meeting titled “ Coming Together: Standing Up to Racism .” Finally, the new Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture has a host of resources for parents and families, schools and educators, and young people and adults for talking about race .

As Brookings President John R. Allen so eloquently stated in his recent piece on the need to condemn racism and come together, the leadership for this is not going to come from national political leaders, but every teacher, principal, school superintendent, and parent of students can do their part to make sure education is playing its part and contributing to all of us learning to live together.

Related Content

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Online Only

10:00 am - 12:30 pm EDT

Danielle Edwards, Matthew A. Kraft

July 17, 2024

Kenneth K. Wong

July 15, 2024

3.2 Education as a Social Problem

The stories that open this chapter illustrate core issues in education. Sociologists define education as a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. On one hand, the institution is essential. In modern societies, people need the ability to read, write, and think in order to succeed in their societies. On the other hand, not everyone can attain their educational goals.

As we remember from Chapter 1 , a social problem is “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world (Leon-Guerrero 2018:4). In this case, because not everyone has access to the education that they need to succeed, we experience negative consequences for individuals, families, and even global communities.

The story of modern education is a story of a significant social shift. As the video in figure 3.1 noted, most people in the world can read and write, something that wasn’t true even a hundred years ago. Although men and boys historically have had more chances to go to school than women and girls, the gender gap in education is closing in the United States and around the world (Roser and Ortiz-Espinosa 2022). Recently, evidence shows that young women are more likely to attend and complete college in the United States than men (Pew Research 2021). These positive results in creating equal access to education don’t tell the whole story, though.

Like every social problem, our social identities and social locations discussed in Chapter 1, play a significant role in the kind of education that is available to us. Social identities and social locations also influence how much school we can finish. When sociologists study education, they find that race, gender, geographical location, socioeconomic status, and all the combinations of these locations have a role in predicting a particular group’s likelihood of succeeding in school. Introductory textbooks commonly focus on race and gender as important predictors of educational success, and they are.

In this section, though, we will focus on the dimensions of diversity that students like you are most interested in understanding—education for d/Deaf, neurodiverse, LGBTQIA+, and Indigenous students. However, if you’d like to learn more about how race and gender affect education, you may be interested in this chapter: An Overview of Education in the United States .

3.2.1 d/Deaf and Black: Intersectional Justice

When sociologists examine the social problems of education, they look at who is defining the problem or claim. We examine the evidence that supports the claims. We evaluate what activists and community members suggest can be done about it. We review law and policy changes to understand their consequences. Finally, we explore how changes might feed subsequent social action.

When we examine educational access and outcomes for d/Deaf students in general and for Black and d/Deaf students in general, we see conflicting claims, different outcomes, and unexpected consequences of law and policy changes. This section explores the experiences of being d/Deaf and being d/Deaf and Black to highlight how inequality is intersectional and why intersectional justice is crucial to attain equity.

Figure 3.3 Being a Deaf Student in a Mainstream School [YouTube Video] . Please watch the first 5 minutes of this video. What experiences does this student have that are the same or different than yours?

As we begin our exploration, you may have noticed that we are using d/Deaf as a general term. This unexpected spelling highlights the first conflict in this area. The more common usage of deaf refers to the medical condition of being physically unable to hear. This traditional definition reflects the perspective of doctors and other medical professionals who define deafness as a medical disability, needing intervention, treatment and special support to enable deaf people to function in a hearing world.

When the word Deaf is capitalized, on the other hand, it refers to a culturally unique group of people. According to Dr. Lissa D. Stapleton, a Deaf Studies professor, “The upper case D in the word Deaf refers to individuals who connect to Deaf cultural practices, the centrality of American Sign Language (ASL), and the history of the community” (Ramirez-Stapleton 2015:569). In this idea of Deafness, Deaf communities have their own language, culture, and practices that are different from hearing cultures but just as valuable. We use d/Deaf in this book to acknowledge the complexity of deafness and Deafness and to discuss both a physical condition and a social location.

Figure 3.4 A family signing using American Sign Language

You may be d/Deaf or know people who are d/Deaf. In that case, you can draw upon your own experiences. The video that opens this section documents one student’s experience. The related picture in figure 3.4 shows people using American Sign Language.

Dr. Stapleton and her collegues explore why college graduation rates for d/Deaf women of color are particularly low. As of 2017, Only 13.7% of d/Deaf Black women get a bachelors degree. In comparison, 26.5% of Black hearing women graduate college. (Garberoglio et al 2019) You may remember from earlier chapters that many social problems are intersectional. People experience them differently based on their various social locations. In this case, Dr. Stapleton looks at how gender, race, and d/Deafness intersect in order to understand the unique experiences of these students. She explains that part of the difficulty for these students is related to being able to be d/Deaf, female and people of color. She shares one story about herself and an Asian d/Deaf student:

I have had several one-on-one interactions with Amy over her two years at the institution. She struggled with shifting identities between her life at home and school. At home, her family treated her like a hearing person; she spoke her ethnic language, participated in all her ethnic cultural practices, and used hearing aids. When she came to school, she only signed and did not interact with other Asian students, as most of the d/Deaf* students on campus were White. She did not feel hearing, Asian, or d/Deaf enough to fit into the residential or campus community. She struggled. Afraid, because of cultural taboos,to tell her parents that she needed counseling and was unable to find a counselor to meet her communication needs (simultaneously signing and speaking), she started to shut down.

The lack of congruency and peace she felt affected her schoolwork, her friendship circles, and now her ability to stay at school because her behavior had become unpredictable and distant.

These stories highlight the experiences of a d/Deaf female Asian student. In some situations being d/Deaf is the most important part of identity. In others, race is a shared experience, either of power or of discrimination. In this story, we begin to see how inequalities in social location set the stage for social problems in education.

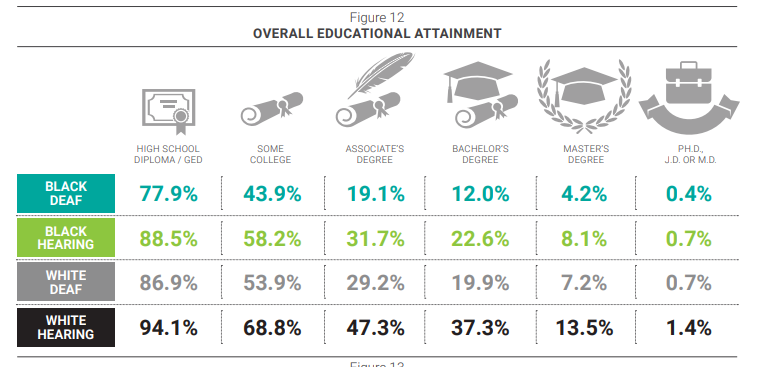

Beyond these stories, though, do we see unequal outcomes in education for d/Deaf students? Let’s look at a small slice of the quantitative data. The table in figure 3.5 addresses the overall educational attainment for Black Deaf, Black Hearing, White Deaf and White Hearing students.

Figure 3.5 Overall Educational Attainment for Black d/Deaf, Black Hearing, White d/Deaf and White Hearing Students, Figure 3.5 I mage Description

We notice that hearing people have higher educational attainments than d/Deaf people with the exception of the PhD, JD, or MD levels, in which Black hearing and White d/Deaf people comprise only .7 percent of each population attained that level of education. Black d/Deaf people had the lowest level of educational achievement of any category.

3.2.1.1 Audism and Racism

One factor in explaining the suffering in these students’ stories, and the different outcomes of d/Deaf students is audism. Audism is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). Students who are d/Deaf experience discrimination because others assume that hearing people are superior, and design education with hearing people in mind.

In the words of one student:

Society assumes and exerts superiority over their capabilities of hearings. In Deaf schools, deaf youths are [likely] to experience being discriminated against based on their deafness because the culture is too deep-rooted with the belief that deaf people can do what hearing people do, only that they can’t hear.

…In mainstream schools, I know this because I experienced this more than often. Sometimes I have teachers or interpreters who think I need some assistance with what to say. They think they know our needs. Sometimes we will have someone jump in to “help” us communicate. It is very embarrassing when speaking to a hearing student, especially if we are attracted to them and always have interpreters jump in act like we need their help to talk.

Hearing people misunderstood our facial, body and gesture expressions and avoided us; even told us to “dial down.” (SOC 204 student 2021)

A second factor in the experience is racism. Racism starts with a belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly a belief that White people are superior to Black, Brown or Indigenous people. We’ll dive deeper into race and racism in Chapter 6 , but as we saw in the stories of the d/Deaf students, people who are d/Deaf can experience prejudice based on the constellation of their social locations.

3.2.2 Inequality In Education: What’s with All the -isms?

|

Figure 3.6 Social ecology of interdependence: the individual and the interpersonal Audism, as defined earlier, is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). This language and this experience are one example of a class of beliefs that asserts that one group is superior to another. Racism may start with a belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly a belief that White people are superior to Black, Brown, or Indigenous people. Sexism starts with a personal belief that men are superior to women or nonbinary people. Ableism starts with a belief that people whose bodies work as expected are better than people who may not be able to see, hear, walk, or have other challenges. Homophobic doesn’t quite fit the pattern, becase it means fear of queer people, but it points to the flawed belief that straight people are better than queer people. What other words do you know that fit this pattern? Collectively, these beliefs are known as prejudice. More specifically, is a belief that people of another group are inferior or bad. While humans appear to be wired to notice difference as a survival trait, assigning value or worth to the difference is a problem. Often we have these feelings or beliefs without ever noticing them. When I was considering what to write, the first story that came to mind was, “Imagine that you are White woman, walking alone in the dark on a deserted city street. You might already be afraid. Now, imagine that a Black man turns the corner and is walking toward you. You might feel more afraid.” I am ashamed that this is my first idea, particularly because I know that most of the time women who are raped are raped by someone they know, most often a partner or ex-partner. And yet, the pattern of belief around White and safe remains in my brain. Many of us are unaware of these false beliefs. Researchers at Harvard have developed a set of tests that help people see their own patterns of belief. This test is called the Implicit Bias Test. Implicit means hidden or unspoken. Bias is another word for prejudice. The researchers compare categories of people—women and men, gay and straight, various religions, arab/muslim and other categories. If you’d like to check your own bias, feel free to take a test or two at . Because it is a belief or judgment of a person, prejudice happens internally. It is the first circle in figure 3.6. However, belief also drives behavior. Harmful action that arises from the flawed belief can be as small as a microaggression, as we explored in Chapter 1. It can be a racial slur or a sexist joke. It can be as violent as someone beating up a transgender person because they think the person is using the wrong bathroom. It can be bombing a Black church or a mosque or a synagogue. It can be passing laws that make it illegal to educate entire groups of people. All of these behaviors are , the unequal treatment of an individual or group on the basis of their statuses. Although the impact of the harm done varies, the belief in the unequal values of people results in behaviors (and systems) that reinforce that inequality. Discrimination is second component of audism, racism, sexism, ableism, and the other -isms that people experience. However belief and behavior are not the only two levels where discrimination can occur. Discrimination happens in our neighborhoods, our schools, our governments, and our countries. It is rooted in the unequal practices of the past, and left unchecked, will flourish in our children. We will refer to the other levels of discrimination throughout the book. For now, it is enough to notice: Where do you see prejudice and discrimination happening in your life, and the lives of the people around you? |

3.2.3 Neurodiversity

Figure 3.7 What is Neurodiversity? [YouTube Video] . As you watch the first 5 minutes of this video, consider the experience of this neurodiverse person. How does inequality in education show up for her?

Activists and scholars notice a parallel between the experiences of Deaf people and neurodiverse people. Deaf people assert that Deaf people form a cultural group. Deafness is not a disability but a normal human variation. Neurodiversity activists use a similar argument. To learn more, you may want to watch the videos in figure 3.7.

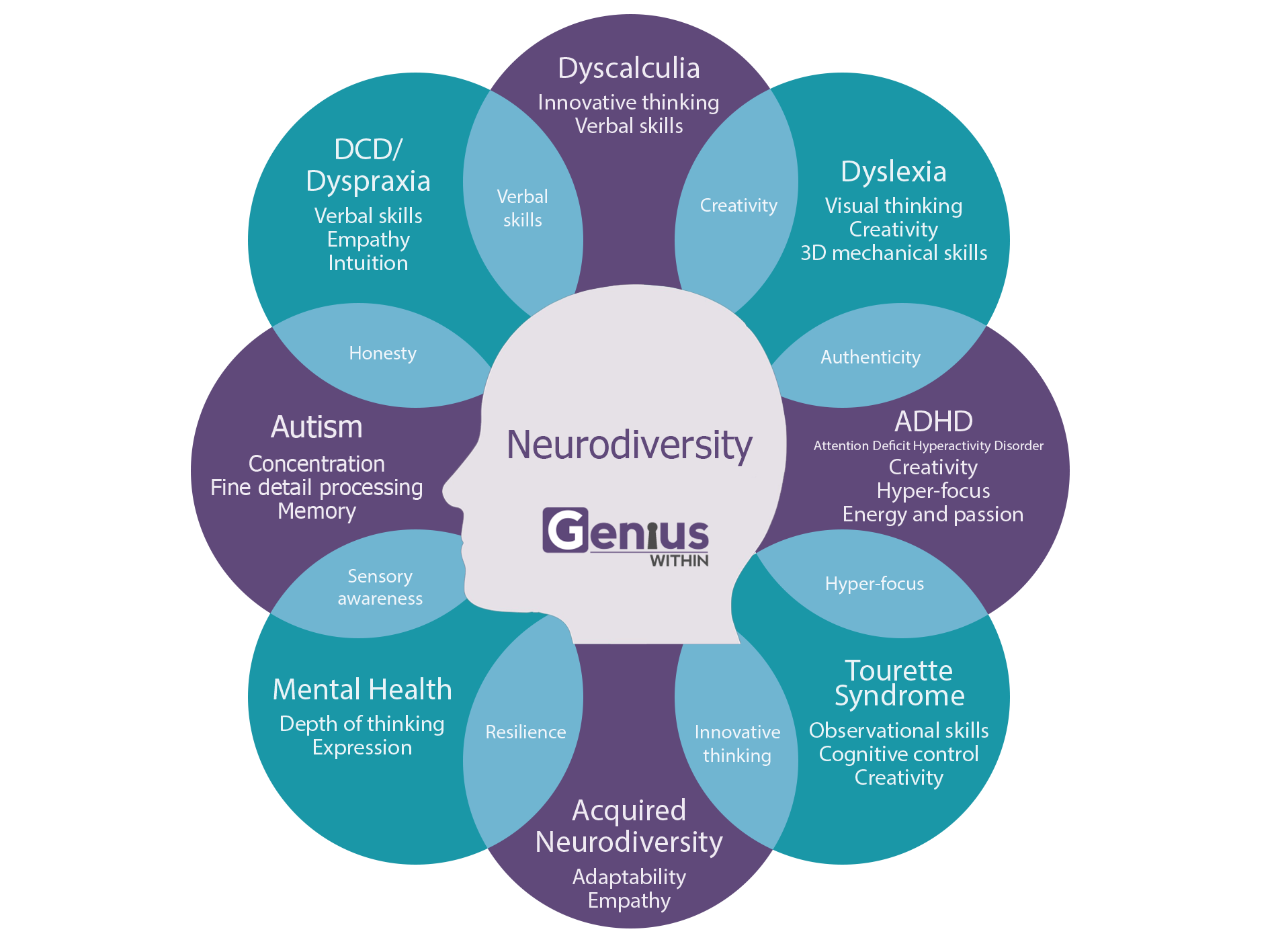

Neurodiversity is a term that means that brain differences are naturally occurring variations in humans. The neurodiversity perspective sees brain differences rather than brain deficits. Instead of viewing differences as disordered or needing to be cured, a neurodiverse perspective sees differences as welcome variants of the human population (Walker 2014; Pollack 2009; Play Spark n.d.).

People whose brains are wired differently than expected are called neurodivergent . Neurodivergent people have significantly better capabilities in some categories, and significantly poorer capabilities in other categories (Doyle 2020).You may hear many labels and diagnosis that make up neurodivergence: ADHD, autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, dyscalculia, learning difference, and many more words.

Researcher David Pollack provides a model of neurodivergence in figure 3.8 which relates several of the labels we listed at the beginning of this section. People experience many different and overlapping learning differences as part of being neurodivergent.

Figure 3.8 Neurodiversity is complicated. (Image created by Genius Within CIC , Source: Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley), Figure 3.8 Image Description

As we move from the individual experience to the social experience, we begin to define the particular social problem. Although estimates differ, Nancy Doyle, a psychologist writing for the British Medical Journal writes that approximately 15 to 20 percent of people worldwide are neurodivergent (Doyle 2020). We see that being neurodivergent is not just the experience of individuals. Rather, it is the shared experience of a group, a needed condition for a social problem.

We also see conflict between how people understand and explain neurodiversity. On one hand, we have a medical model, based on pathology or abnormality (Walker and Raymaker 2021). In this model, differences in reading, calculating, writing or interacting with others is considered a problem, something to be treated or cured.

In the 1990s, adults with these labels began to push back against these categorizations. Their alternate claim was that these conditions should be considered as normal human variants of neurology. Patient-centered care advocate Valerie Billingham coined the phrase, “nothing about me, without me” (1998). She was talking about the need to include the patient at the center of decision-making around patient health and patient treatment choices.

Figure 3.9 Positive experiences of Neurodiversity, Figure 3.9 Image Description

This phrase is used widely today by autism awareness activists, who have expanded the meaning to include the idea that people who are neurodivergent should be the ones describing their own experiences. The letter in figure 3.9 provides one example of this. People with autism are the ones who should make choices about what they need to fully participate in school and in life. They should propose the laws, policies and practices that make their participation possible.

Some experts see neurodiversity itself is a civil rights challenge. They argue that society privileges people who are considered neurotypical. Not only are neurodiverse people stigmatized with a label that implies disease, or symptom or medical problem, social institutions themselves are unequal. They propose that we strive for “ neuro-equality (understood to require equal opportunities, treatment and regard for those who are neurologically different)” (Fenton and Khran 2007:1). Likewise, Nick Walker , a queer, transgender, autistic scholar, encourages us to see beyond the medical model. She writes,

The neurodiversity paradigm starts from the understanding that neurodiversity is an axis of human diversity, like ethnic diversity or diversity of gender and sexual orientation, and is subject to the same sorts of social dynamics as those other forms of diversity —including the dynamics of social power inequalities, privilege, and oppression. (Walker 2021)

In this brief explanation, we see the shared experience of a group of people. We see disagreement in how we understand the experience of that group. We see unequal outcomes in school and in life. Activists propose changes, and our government enacts legal and policy changes. This activity leads to new formulations of the problem and requests for action. In short, we see a social problem.

3.2.4 Can You Display A Rainbow Flag at School?

Figure 3.10 Newberg’s ban on pride flags at schools gets national attention [YouTube Video] . Newberg School bans Black Lives Matter and Pride symbols.

In 2021, the school board of the small town of Newberg, Oregon, voted to ban the display of Black Lives Matter and Gay pride symbols at school and found themselves in the national spotlight. The video in figure 3.10 describes the school board’s reasoning and the community’s reaction. This local experience is not unique. In school boards, state legislatures, and national forums students, teachers, parents and community members discuss these questions. For example, on March 28, 2022, Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed the Parental Rights in Education Bill, which prohibits teachers from teaching about sexual orientation or gender identity in kindergarden through third grade.

The debate over these decisions reflects a larger social problem for another unique group of students, as shown in figure 3.11. LBGTQIA+ is an acronym which stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex asexual and more. We’ll explore the importance of terminology later in this chapter in “Inequality in Education: Why Do I Say Queer?”

Figure 3.11 People who are queer, Black, and disabled in front of a rainbow flag

The social problem in this case isn’t that the students are LGBTQIA+. It’s that these students face bullying, discrimination, homelessness, and violence because of their gender and sexual identities. When we look at experience in school, most research shows that queer youth are more likely to drop out of high school and less likely to attend college than their straight, cisgender peers (Sansone 2019). When we look at the recent data for Oregon in the 2020 Safe Schools report , LGBTQIA+ youth were twice as likely to be bullied or harassed at school (Heffernan and Gutierez-Schmich 2020).

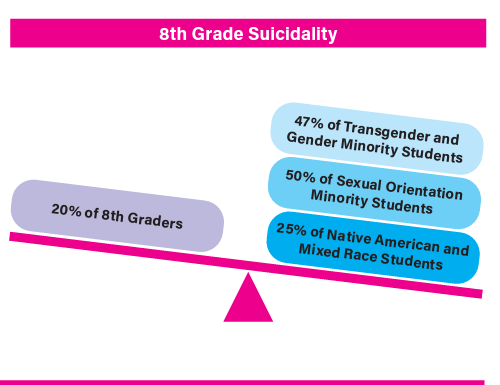

The Safe Schools report takes an intersectional approach by examining gender identity, sexual orientation, and race and ethnicity. The report finds that the more of these marginalized identities a student holds, the more likely they are to be bullied or to be threatened by a weapon at school (Heffernan and Gutierez-Schmich 2020). As the chart in figure 3.12 demonstrates, a person who is transgender or nonbinary, queer, Native American, or mixed race is far more likely to have thought about ending their life or tried to end their life, even as early as eighth grade. The weight of this evidence is compelling. Our LGBTQIA+ students experience bullying, discrimination and violence at school and in the wider world.

Figure 3.12 Safe Schools Report: Eighth grade suicidality by gender, sexual orientation and race, Figure 3.12 Image Description

3.2.5 Why Do I Say Queer?: A Badge of Courage or a Bad Word?

| For some people it is a bad word. For others, it is a source of power. Please take a moment to watch the 3-minute video in figure 3.13 from activist Tyler Ford about the history of the word queer. How do you understand this word?

Figure 3.13 I, Kim Puttman, call myself . Queer as in different, but also queer as in challenging dominant ideas about what identity, sexuality, love, relationship and family look like. I also identify as lesbian. I love my wife. Our relationship expands what it means to be “normal” and “healthy.” I embrace this identity as a source of my power, even though it is also a source of my marginalization. I stand with generations of activists before me, chanting “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” In the words of Alex Kapitan, on the Radical Copy Editor blog: But queer can also be used as a word that conveys hate. When used as an insult, queer is a word that wounds. Using this word as a threat may be grounded in , the irrational fear of or prejudice against individuals who are or perceived to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other non-heterosexual people. More importantly, it maintains , the assumption that heterosexuality is the standard for defining normal sexual behavior and that male–female differences and gender roles are the natural and immutable essentials in normal human relations (APA n.d.). When a bully calls someone queer, they reinforce the idea that straight and cisgender is the only right way to be. So, in this murky terrain, which word do you use? Figure 3.14 offers an illustration that may help:

Figure 3.14 LGBTQIA+ Deconstructed, Although there are many historical reasons that certain names are preferred, it can help to understand that we are looking at continuums of gender and sexual identity. We won’t repeat the dictionary, but you can look for specific definitions of the terms below at the and the . The following categories provide an entry point into this discussion about how people describe themselves: Some of these words describe the sexual characteristics of your physical body. These words include female, male, and intersex. Some of these words are used to explore whether your physical body and your identity about your physical body match. These words include cisgender and transgender. They can also include male and female, when your identity and your sex match. Want to learn more? In by Minus18, students describe transgender identities and pronouns Some of these words refer to someone’s gender, or outward expression of gender. These words include androgynous, feminine, or masculine. Some of these words refer to someone’s sexual attraction—do they love someone of the same gender, a different gender, or without reference to gender. These words can include lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, and many others. Finally, some of these words describe cultural experiences of non-conforming sexuality or gender identities. These words include Two Spirit, Muxes, and many more. For more, check out these resources: in which “two-spirit” is described by a two-spirit person, and the blogpostIf you want more information on the various continuums of gender and sexual expression check out this great discussion of But, wait, what’s the answer? Can I call someone queer? Maybe, maybe not… My advice is to listen first. If you listen to what people call themselves, you will use the right word, whether queer, lesbian, they, trans, or just me. |

3.2.6 Residential Schools

As we continue our exploration of education and inequality, we see that the institution of education can also support violent and oppressive social change. For this, we look at the history of residential schools in the United States and Canada designed with the explicit intention of disrupting the families and the cultures of Indigenous people.

By establishing boarding schools for Indigenous and First Nations peoples as part of a government-sanctioned attempt to solve the “Indian problem,” colonizers committed genocide , the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. Many indigenous children died in residential schools. The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report , released in May 2022. documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021). These deaths are only the start of supporting the claim of genocide. According to Jeffrey Ostler, a historian at the University of Oregon claims of genocide are contested by scholars and activists (like many social problems). Let’s look deeper.

The federal report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 federal boarding schools between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws that required Native American parents to send their children to these boarding schools (Newland 2022:35). Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022:38). Because students were required to learn English and agriculture, and punished, sometimes beaten, if they spoke their Indigenous languages and practiced their own religious and spiritual practices, families and cultures were indeed destroyed.

Figure 3.15 Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior

Deb Haaland, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, describes this history in the following way:

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland, shown in figure 3.15, also recounts the suffering in her own family. She writes, “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian, and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). The 2022 U.S. federal report documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021).

Figure 3.16 Chemawa Indian School

The U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children to attend residential schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition n.d.). Oregon shares this painful history. Historian Eva Guggemos and volunteer historian SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University combed the historical record for the Forest Grove Indian Training School in Forest Grove which became the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (figure 3.16). They found that at least 270 children had died while at these schools. Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases. “ The Forest Grove Indian Training School, 1880–1885 [YouTube Video] ” tells more of the story.

Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural assimilation , the process by which the members of a subordinate group adopt the aspects of a dominant group. In this case, the colonizers valued their own White European culture and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in figure 3.17 and 3.18 tell the story.

Figure 3.17 A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.”

Figure 3.18 Seven months later — the students pictured are probably the Spokane students who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief.

A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck.

Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse.

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures. (Francis 2019)

The function of education in the case of Native American boarding schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. Education functioned to purposefully disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to education of Indigenous children were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. Jefferson wrote:

To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts. (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21)

By removing people from the land, and children from families, the U.S. government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, using education as one method of enforcement.

3.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Problem

“Education as a Social Problem: d/Deaf Education, Neurodiversity and Rainbow Flags” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 3.3 “ Being Deaf in a Mainstream School ” by Rikki Poynter . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.4 ASL family by David Fulmer . License: CC BY 2.0 .

Figure 3.5 “ Overall Educational Attainment ” (p.12) by © National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes Postsecondary Achievement of Black Deaf People in the United States . License : BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 3.6 “Social Ecology of Interdependence: The Individual and the Interpersonal” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 3.7 “ What is neurodiversity? ” by The Counseling Channel . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.8 Neurodiversity is complicated © Genius Within CIC / Source: Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Figure 3.9 Photo by walkinred . License: CC BY-SA 2.0 .

Figure 3.10 “ Newberg School BLM and Pride are Banned ” by KGW News . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.11 Photo by Chona Kasinger , Disabled And Here . License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.12 “8th Grade Suicidality by Gender, Sexual Orientation and Race” in Safe Schools Report by Julie Heffernan and Tina Gutierez-Schmich. Used under fair use.

Figure 3.13 “ Tyler Ford Explains The History Behind the Word ‘Queer’”. by them . License Terms: Standard YouTube license.

Figure 3.14: LGBTQIA+ acronym © 2021 by Harold Tinoco-Giraldo , Eva María Torrecilla Sánchez .and Francisco J. García-Peñalvo License: CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 3.15 Deb Haaland by the U.S House Office of Photography is in the Public domain .

Figure 3.16 Chemawa Indian School by Library of Congress is in the Public domain .

Figure 3.17 Caption from A Tragic Collision of Cultures by Mike Francis. Fair Use.

Figure 3.18 Caption from A Tragic Collision of Cultures by Mike Francis. Fair Use.

Social Problems Copyright © by Kim Puttman. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

What the judge was thinking and what’s next in Trump documents case

What’s the point of kids?

Boston busing in 1974 was about race. Now the issue is class.

The costs of inequality: Education’s the one key that rules them all

When there’s inequity in learning, it’s usually baked into life, Harvard analysts say

Corydon Ireland

Harvard Correspondent

Third in a series on what Harvard scholars are doing to identify and understand inequality, in seeking solutions to one of America’s most vexing problems.

Before Deval Patrick ’78, J.D. ’82, was the popular and successful two-term governor of Massachusetts, before he was managing director of high-flying Bain Capital, and long before he was Harvard’s most recent Commencement speaker , he was a poor black schoolchild in the battered housing projects of Chicago’s South Side.

The odds of his escaping a poverty-ridden lifestyle, despite innate intelligence and drive, were long. So how did he help mold his own narrative and triumph over baked-in societal inequality ? Through education.

“Education has been the path to better opportunity for generations of American strivers, no less for me,” Patrick said in an email when asked how getting a solid education, in his case at Milton Academy and at Harvard, changed his life.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.”

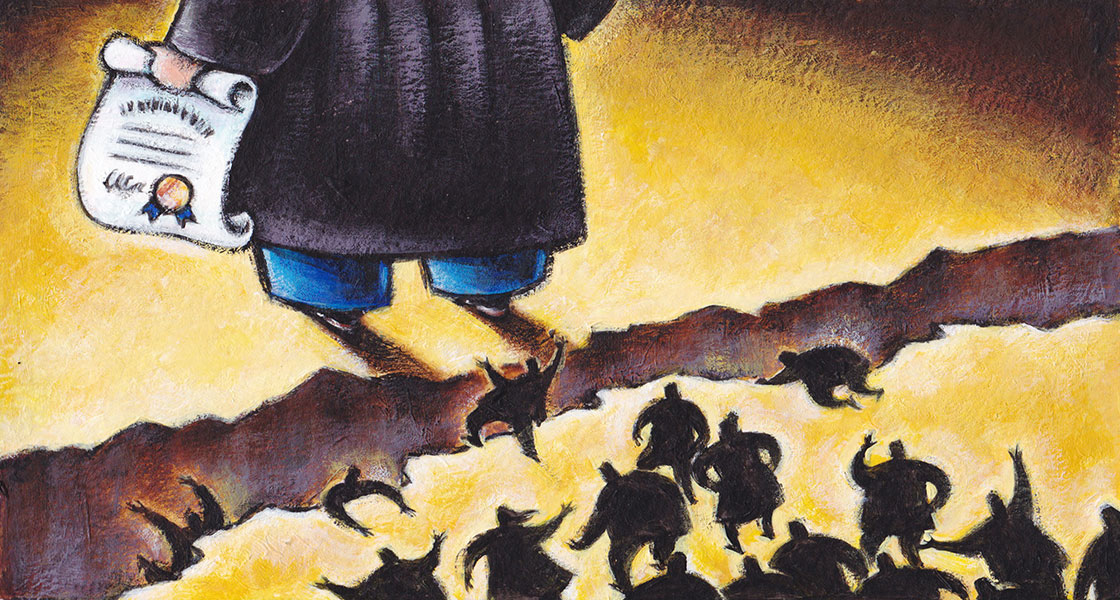

If inequality starts anywhere, many scholars agree, it’s with faulty education. Conversely, a strong education can act as the bejeweled key that opens gates through every other aspect of inequality , whether political, economic , racial, judicial, gender- or health-based.

Simply put, a top-flight education usually changes lives for the better. And yet, in the world’s most prosperous major nation, it remains an elusive goal for millions of children and teenagers.

Plateau on educational gains

The revolutionary concept of free, nonsectarian public schools spread across America in the 19th century. By 1970, America had the world’s leading educational system, and until 1990 the gap between minority and white students, while clear, was narrowing.

But educational gains in this country have plateaued since then, and the gap between white and minority students has proven stubbornly difficult to close, says Ronald Ferguson, adjunct lecturer in public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and faculty director of Harvard’s Achievement Gap Initiative. That gap extends along class lines as well.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.” — Deval Patrick

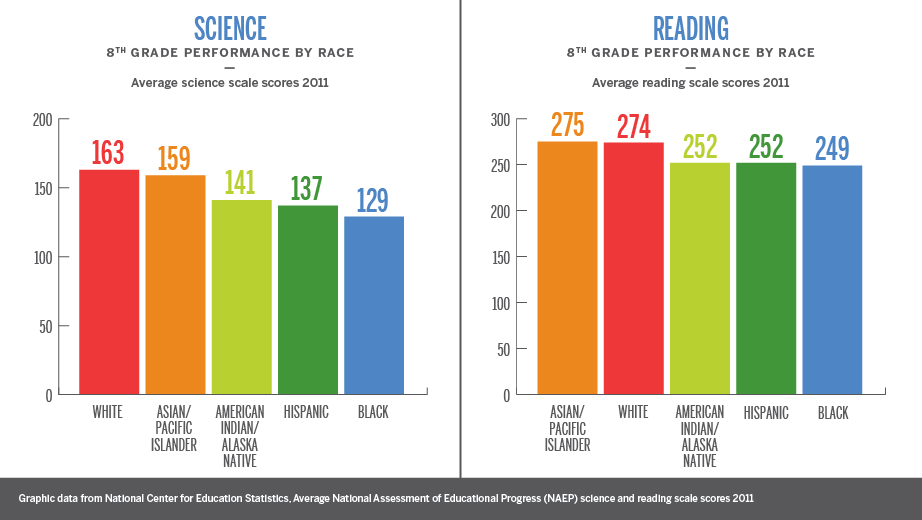

In recent years, scholars such as Ferguson, who is an economist, have puzzled over the ongoing achievement gap and what to do about it, even as other nations’ school systems at first matched and then surpassed their U.S. peers. Among the 34 market-based, democracy-leaning countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States ranks around 20th annually, earning average or below-average grades in reading, science, and mathematics.

By eighth grade, Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer Jr. noted last year, only 44 percent of American students are proficient in reading and math. The proficiency of African-American students, many of them in underperforming schools, is even lower.

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming,” wrote Fryer, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, who used the OECD rankings as a metaphor for minority standing educationally. “If they were to be considered a country, they would rank just below Mexico in last place.”

Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Dean James E. Ryan, a former public interest lawyer, says geography has immense power in determining educational opportunity in America. As a scholar, he has studied how policies and the law affect learning, and how conditions are often vastly unequal.

His book “Five Miles Away, A World Apart” (2010) is a case study of the disparity of opportunity in two Richmond, Va., schools, one grimly urban and the other richly suburban. Geography, he says, mirrors achievement levels.

A ZIP code as predictor of success

“Right now, there exists an almost ironclad link between a child’s ZIP code and her chances of success,” said Ryan. “Our education system, traditionally thought of as the chief mechanism to address the opportunity gap, instead too often reflects and entrenches existing societal inequities.”

Urban schools demonstrate the problem. In New York City, for example, only 8 percent of black males graduating from high school in 2014 were prepared for college-level work, according to the CUNY Institute for Education Policy, with Latinos close behind at 11 percent. The preparedness rates for Asians and whites — 48 and 40 percent, respectively — were unimpressive too, but nonetheless were firmly on the other side of the achievement gap.

In some impoverished urban pockets, the racial gap is even larger. In Washington, D.C., 8 percent of black eighth-graders are proficient in math, while 80 percent of their white counterparts are.

Fryer said that in kindergarten black children are already 8 months behind their white peers in learning. By third grade, the gap is bigger, and by eighth grade is larger still.

According to a recent report by the Education Commission of the States, black and Hispanic students in kindergarten through 12th grade perform on a par with the white students who languish in the lowest quartile of achievement.

There was once great faith and hope in America’s school systems. The rise of quality public education a century ago “was probably the best public policy decision Americans have ever made because it simultaneously raised the whole growth rate of the country for most of the 20th century, and it leveled the playing field,” said Robert Putnam, the Peter and Isabel Malkin Professor of Public Policy at HKS, who has written several best-selling books touching on inequality, including “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community” and “Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis.”

Historically, upward mobility in America was characterized by each generation becoming better educated than the previous one, said Harvard economist Lawrence Katz. But that trend, a central tenet of the nation’s success mythology, has slackened, particularly for minorities.

“Thirty years ago, the typical American had two more years of schooling than their parents. Today, we have the most educated group of Americans, but they only have about .4 more years of schooling, so that’s one part of mobility not keeping up in the way we’ve invested in education in the past,” Katz said.

As globalization has transformed and sometimes undercut the American economy, “education is not keeping up,” he said. “There’s continuing growth of demand for more abstract, higher-end skills” that schools aren’t delivering, “and then that feeds into a weakening of institutions like unions and minimum-wage protections.”

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming.” — Roland G. Fryer Jr.

Fryer is among a diffuse cohort of Harvard faculty and researchers using academic tools to understand the achievement gap and the many reasons behind problematic schools. His venue is the Education Innovation Laboratory , where he is faculty director.

“We use big data and causal methods,” he said of his approach to the issue.

Fryer, who is African-American, grew up poor in a segregated Florida neighborhood. He argues that outright discrimination has lost its power as a primary driver behind inequality, and uses economics as “a rational forum” for discussing social issues.

Better schools to close the gap

Fryer set out in 2004 to use an economist’s data and statistical tools to answer why black students often do poorly in school compared with whites. His years of research have convinced him that good schools would close the education gap faster and better than addressing any other social factor, including curtailing poverty and violence, and he believes that the quality of kindergarten through grade 12 matters above all.

Supporting his belief is research that says the number of schools achieving excellent student outcomes is a large enough sample to prove that much better performance is possible. Despite the poor performance by many U.S. states, some have shown that strong results are possible on a broad scale. For instance, if Massachusetts were a nation, it would rate among the best-performing countries.

At HGSE, where Ferguson is faculty co-chair as well as director of the Achievement Gap Initiative, many factors are probed. In the past 10 years, Ferguson, who is African-American, has studied every identifiable element contributing to unequal educational outcomes. But lately he is looking hardest at improving children’s earliest years, from infancy to age 3.

In addition to an organization he founded called the Tripod Project , which measures student feedback on learning, he launched the Boston Basics project in August, with support from the Black Philanthropy Fund, Boston’s mayor, and others. The first phase of the outreach campaign, a booklet, videos, and spot ads, starts with advice to parents of children age 3 or younger.

“Maximize love, manage stress” is its mantra and its foundational imperative, followed by concepts such as “talk, sing, and point.” (“Talking,” said Ferguson, “is teaching.”) In early childhood, “The difference in life experiences begins at home.”

At age 1, children score similarly

Fryer and Ferguson agree that the achievement gap starts early. At age 1, white, Asian, black, and Hispanic children score virtually the same in what Ferguson called “skill patterns” that measure cognitive ability among toddlers, including examining objects, exploring purposefully, and “expressive jabbering.” But by age 2, gaps are apparent, with black and Hispanic children scoring lower in expressive vocabulary, listening comprehension, and other indicators of acuity. That suggests educational achievement involves more than just schooling, which typically starts at age 5.

Key factors in the gap, researchers say, include poverty rates (which are three times higher for blacks than for whites), diminished teacher and school quality, unsettled neighborhoods, ineffective parenting, personal trauma, and peer group influence, which only strengthens as children grow older.

“Peer beliefs and values,” said Ferguson, get “trapped in culture” and are compounded by the outsized influence of peers and the “pluralistic ignorance” they spawn. Fryer’s research, for instance, says that the reported stigma of “acting white” among many black students is true. The better they do in school, the fewer friends they have — while for whites who are perceived as smarter, there’s an opposite social effect.

The researchers say that family upbringing matters, in all its crisscrossing influences and complexities, and that often undercuts minority children, who can come from poor or troubled homes. “Unequal outcomes,” he said, “are from, to a large degree, inequality in life experiences.”

Trauma also subverts achievement, whether through family turbulence, street violence, bullying, sexual abuse, or intermittent homelessness. Such factors can lead to behaviors in school that reflect a pervasive form of childhood post-traumatic stress disorder.

[gz_sidebar align=”left”]

Possible solutions to educational inequality:

- Access to early learning

- Improved K-12 schools

- More family mealtimes

- Reinforced learning at home

- Data-driven instruction

- Longer school days, years

- Respect for school rules

- Small-group tutoring

- High expectations of students

- Safer neighborhoods

[/gz_sidebar]

At Harvard Law School, both the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative and the Education Law Clinic marshal legal aid resources for parents and children struggling with trauma-induced school expulsions and discipline issues.

At Harvard Business School, Karim R. Lakhani, an associate professor who is a crowdfunding expert and a champion of open-source software, has studied how unequal racial and economic access to technology has worked to widen the achievement gap.

At Harvard’s Project Zero, a nonprofit called the Family Dinner Project is scraping away at the achievement gap from the ground level by pushing for families to gather around the meal table, which traditionally was a lively and comforting artifact of nuclear families, stable wages, close-knit extended families, and culturally shared values.

Lynn Barendsen, the project’s executive director, believes that shared mealtimes improve reading skills, spur better grades and larger vocabularies, and fuel complex conversations. Interactive mealtimes provide a learning experience of their own, she said, along with structure, emotional support, a sense of safety, and family bonding. Even a modest jump in shared mealtimes could boost a child’s academic performance, she said.

“We’re not saying families have to be perfect,” she said, acknowledging dinnertime impediments like full schedules, rudimentary cooking skills, the lure of technology, and the demands of single parenting. “The perfect is the enemy of the good.”

Whether poring over Fryer’s big data or Barendsen’s family dinner project, there is one commonality for Harvard researchers dealing with inequality in education: the issue’s vast complexity. The achievement gap is a creature of interlocking factors that are hard to unpack constructively.

Going wide, starting early

With help from faculty co-chair and Jesse Climenko Professor of Law Charles J. Ogletree, the Achievement Gap Initiative is analyzing the factors that make educational inequality such a complex puzzle: home and family life, school environments, teacher quality, neighborhood conditions, peer interaction, and the fate of “all those wholesome things,” said Ferguson. The latter include working hard in school, showing respect, having nice friends, and following the rules, traits that can be “elements of a 21st-century movement for equality.”

In the end, best practices to create strong schools will matter most, said Fryer.

He called high-quality education “the new civil rights battleground” in a landmark 2010 working paper for the Handbook of Labor Economics called “Racial Inequality in the 21st Century: The Declining Significance of Discrimination.”

Fryer tapped 10 large data sets on children 8 months to 17 years old. He studied charter schools, scouring for standards that worked. He champions longer school days and school years, data-driven instruction, small-group tutoring, high expectations, and a school culture that prizes human capital — all just “a few simple investments,” he wrote in the working paper. “The challenge for the future is to take these examples to scale” across the country.

How long would closing the gap take with a national commitment to do so? A best-practices experiment that Fryer conducted at low-achieving high schools in Houston closed the gap in math skills within three years, and narrowed the reading achievement gap by a third.

“You don’t need Superman for this,” he said, referring to a film about Geoffrey Canada and his Harlem Children’s Zone, just high-quality schools for everyone, to restore 19th-century educator Horace Mann’s vision of public education as society’s “balance-wheel.”

Last spring, Fryer, still only 38, won the John Bates Clark medal, the most prestigious award in economics after the Nobel Prize. He was a MacArthur Fellow in 2011, became a tenured Harvard professor in 2007, was named to the prestigious Society of Fellows at age 25. He had a classically haphazard childhood, but used school to learn, grow, and prosper. Gradually, he developed a passion for social science that could help him answer what was going wrong in black lives because of educational inequality.

With his background and talent, Fryer has a dramatically unique perspective on inequality and achievement, and he has something else: a seemingly counterintuitive sense that these conditions will improve, once bad schools learn to get better. Discussing the likelihood of closing the achievement gap if Americans have the political and organizational will to do so, Fryer said, “I see nothing but optimism.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately portrayed details of Dr. Fryer’s background.

Illustration by Kathleen M.G. Howlett. Harvard staff writer Christina Pazzanese contributed to this report.

Next Tuesday: Inequality in health care

Share this article

You might like.

Obama-era White House counsel says key point in Nixon decision should have ended inquiry

New book explores history, philosophy of having children and shifting attitudes in 21st century

School-reform specialist examines mixed legacy of landmark decision, changes in demography, hurdles to equity in opportunity

When should Harvard speak out?

Institutional Voice Working Group provides a roadmap in new report

Had a bad experience meditating? You're not alone.

Altered states of consciousness through yoga, mindfulness more common than thought and mostly beneficial, study finds — though clinicians ill-equipped to help those who struggle

College sees strong yield for students accepted to Class of 2028

Financial aid was a critical factor, dean says

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Here's what schools are doing to try to address students' social-emotional needs

Anya Kamenetz

Grimsley High School teacher Sierra Hannipole checks in with a student at the Greensboro, N.C., school's learning hub. According to new federal data, 6 in 10 schools around the U.S., including Grimsley, have given extra training to teachers to support students socially and emotionally this school year. Cornell Watson for NPR hide caption

Grimsley High School teacher Sierra Hannipole checks in with a student at the Greensboro, N.C., school's learning hub. According to new federal data, 6 in 10 schools around the U.S., including Grimsley, have given extra training to teachers to support students socially and emotionally this school year.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory this month saying the youth mental health crisis is getting worse.

"The pandemic era's unfathomable number of deaths, pervasive sense of fear, economic instability, and forced physical distancing from loved ones, friends, and communities have exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced," Murthy wrote . But he also emphasized that mental health conditions are treatable and preventable.

Children's Health

The u.s. surgeon general issues a stark warning about the state of youth mental health.

And newly released data from the U.S. Department of Education suggests that schools all over the country are trying to play their part. A federal survey of 170 schools in September found that 97% are taking some steps to support student well-being now that they are back to teaching in person. This includes one or more of the following:

- 59% are offering specialized professional development to existing staff members so they can support students in turn.

- 42% have hired new staff, such as counselors and social workers.

- 26% have added student classes to address topics related to social, emotional or mental well-being.

- 20% have created community events and partnerships.

Educators at Grimsley High School in Greensboro, N.C., have seen the toll the coronavirus pandemic has taken on students, socially and emotionally.

"A lot of our kids are still struggling with ... being acclimated to the reality that a couple of years ago they were in middle school, and then they were just dropped here [in high school]. So there are some struggles there, [as well as] kids who may be going through things emotionally at home," says Assistant Principal Christopher Burnette.

Back To School: Live Updates

We know students are struggling with their mental health. here's how you can help.

Guilford County Schools, which includes Grimsley High School, has partnered with outside donors, including the Walton Family Foundation and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, to offer "learning hubs" that run after school and in some schools on weekends. (Dell Technologies is a financial supporter of NPR.) The hubs are places to catch up on schoolwork, but they're also places to check in on students' states of mind, says Burnette.

"A lot of it is not always about homework or schoolwork — it's about kind of how you're doing, how you're feeling. And if they start to open up, we'll, you know, pull them to the side and we'll be able to identify certain things that support them in that particular way as well."

The hubs have a school counselor on hand, and the school has trained other staff members to handle these kinds of supportive conversations.

How Teachers Can Promote Social Change in the Classroom

The philosopher John Dewey wrote, “Education is not a preparation for life but is life itself.” Dewey reflected extensively on the page about the role of education in a healthy, ever-evolving democratic society, and he believed classrooms aren’t just a place to study social change, but a place to spark social change. Dewey wrote about these topics in the early twentieth century, at a time when debates raged about whether teachers should be tasked with preparing students to conform or to actively push for progress and improvement where they are necessary.

These same debates continue today with real implications for education policy. Dewey remains one of our clearest voices on the argument that the classroom ought to be seen as an important locus of social change. For present and future teachers, it’s one thing to appreciate Dewey’s views on education and social change and quite another to create a classroom environment that embodies them. So, how can teachers build real classrooms that exemplify Dewey’s ideals for education in society?

Here are a few ideas:

1. encourage active participation and experimentation with ideas among students..

Unfortunately, teachers and students who want to see some kind of paper-based progress often push for a lot of memorization of dates, facts, and definitions. However, this type of learning is not the society-shifting classroom activity of which Dewey wrote. Instead, teachers should construct active learning opportunities, where students can be fully engaged with the material and play with ideas without being reprimanded for going too far afield. A few ways teachers might facilitate such a learning environment include letting students teach each other, setting up a system for occasionally letting students ask anonymous questions, and assigning open-ended projects in which students aren’t given the impression that they’re expected to take prescribed steps until they get to the “right” answer.

2. Teach students how to think instead of teaching them what to think.

Starting to make strides in this area may be as simple as rethinking common assumptions about which subjects are suitable for which students and when. For example, multiple studies suggest that philosophical inquiry is not above the heads of elementary-aged students. A Washington Post article on the topic describes the Philosophy for Children movement, in which a teacher offers a poem, story, or other object and employs the Socratic method to stimulate classroom discussion – not necessarily about the prompt, but around it. The students’ impressions and quandaries are what take center stage, not an actual philosophical mode or text. In other words, students are being taught how to think (and that their thoughts have weight and value and should be pursued) rather than what to think. Evidence suggests that students respond well to the Philosophy in the Classroom exercise, which, when performed just once a week, has been shown to improve students’ reading levels, critical thinking skills, and emotional wellbeing.

Socrates himself said, “Education is a kindling of a flame, not a filling of a vessel.” It follows, then, that using Socrates’ method of discourse as a teaching tool would line up well with Dewey’s goals for the classroom.

3. Prepare students to expect the need for change and to believe in their own ability to take positive steps for the benefit of society.

One step teachers can take to encourage students to play a part in larger societal improvement is to create a classroom where they’re given the responsibility and authority to make some significant decisions. If teachers have all the answers, it’s implied that students are expected to receive knowledge, not offer solutions or improvements. But if teachers make it clear that, especially when it comes to the big questions we all face, even those in authority don’t know it all, then students have more room to rely on their own cognitive powers and problem-solving skills.

Teachers might try offering lessons in, for example, how ethical decisions are made and the role of empathy and considered argument, and then setting up situations in which students can apply these skills in solving problems.

It’s also important to create a learning environment in which students learn to see the benefit of a worthy failure – rather than learning to fear the possibility of doing something wrong.

4. Make classroom processes democratic to establish the idea that if we actively participate in our communities, we can help make decisions about how they function.