Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

103 Race Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Race is a complex and sensitive topic that has been at the forefront of discussions for centuries. From systemic racism to cultural appropriation, race plays a significant role in shaping our society and the way we interact with one another. If you are looking for essay topic ideas on race, here are 103 examples to help you get started:

- The history of racism in America

- The impact of colonialism on race relations

- White privilege and its effects on society

- The role of race in the criminal justice system

- Racism in the workplace

- The intersectionality of race and gender

- The portrayal of race in the media

- The effects of racial profiling

- Colorism within communities of color

- The role of race in education

- Interracial relationships and their challenges

- The cultural appropriation of minority groups

- The impact of race on mental health

- The history of affirmative action

- Racial disparities in healthcare

- The stereotypes associated with different racial groups

- The role of race in politics

- The representation of race in literature

- The effects of gentrification on minority communities

- The role of race in sports

- The experience of being a person of color in a predominantly white community

- The impact of race on social mobility

- The role of race in shaping identity

- The effects of racism on mental health

- The history of racial segregation

- The portrayal of race in popular culture

- The impact of race on access to resources

- The representation of race in art

- The effects of racial microaggressions

- The role of race in shaping beauty standards

- The impact of race on voting rights

- The portrayal of race in advertising

- The effects of race-based trauma

- The role of race in shaping political ideologies

- The representation of race in video games

- The impact of race on environmental justice

- The effects of race on access to affordable housing

- The history of race-based discrimination in the legal system

- The portrayal of race in historical monuments

- The role of race in shaping immigration policies

- The impact of race on access to quality education

- The representation of race in fashion

- The effects of racial disparities in the criminal justice system

- The role of race in shaping reproductive rights

- The portrayal of race in social media

- The impact of race on access to healthcare

- The effects of race on access to clean water

- The history of race-based violence

- The role of race in shaping economic opportunities

- The representation of race in music

- The impact of race on access to technology

- The effects of racial disparities in the foster care system

- The role of race in shaping environmental policies

- The portrayal of race in reality TV shows

- The impact of race on access to transportation

- The effects of race on access to healthy food options

- The history of race-based hate crimes

- The role of race in shaping international relations

- The representation of race in comic books

- The impact of race on access to mental health services

- The effects of racial disparities in the juvenile justice system

- The role of race in shaping social movements

- The portrayal of race in online communities

- The impact of race on access to reproductive healthcare

- The effects of race on access to childcare services

- The history of race-based housing discrimination

- The role of race in shaping cultural norms

- The representation of race in theater

- The impact of race on access to legal services

- The effects of racial disparities in the education system

- The role of race in shaping family dynamics

- The portrayal of race in animated films

- The impact of race on access to public transportation

- The effects of race on access to affordable childcare

- The history of race-based employment discrimination

- The role of race in shaping religious beliefs

- The representation of race in documentaries

- The impact of race on access to affordable housing

- The effects of racial disparities in the healthcare system

- The role of race in shaping cultural traditions

- The portrayal of race in video games

- The impact of race on access to affordable childcare

- The effects of race on access to public transportation

When choosing a topic on race, it is important to consider your own perspective and experiences. By exploring these essay topic ideas, you can gain a deeper understanding of how race shapes our society and the ways in which we can work towards a more equitable and inclusive future.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Race and Ethnicity

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Race is a concept of human classification scheme based on visible features including eye color, skin color, the texture of the hair and other facial and bodily characteristics. Through these features, humans are ten categorized into distinct groups of population and this is enhanced by the fact that the characteristics are fully inherited.

Across the globe, debate on the topic of race has dominated for centuries. This is especially due to the resultant discrimination meted on the basis of these differences. Consequently, a lot of controversy surrounds the issue of race socially, politically but also in the scientific world.

According to many sociologists, race is more of a modern idea rather than a historical. This is based on overwhelming evidence that in ancient days physical differences mattered least. Most divisions were as a result of status, religion, language and even class.

Most controversy originates from the need to understand whether the beliefs associated with racial differences have any genetic or biological basis. Classification of races is mainly done in reference to the geographical origin of the people. The African are indigenous to the African continent: Caucasian are natives of Europe, the greater Asian represents the Mongols, Micronesians and Polynesians: Amerindian are from the American continent while the Australoid are from Australia. However, the common definition of race regroups these categories in accordance to skin color as black, white and brown. The groups described above can then fall into either of these skin color groupings (Origin of the Races, 2010, par6).

It is possible to believe that since the concept of race was a social description of genetic and biological differences then the biologists would agree with these assertions. However, this is not true due to several facts which biologists considered. First, race when defined in line with who resides in what continent is highly discontinuous as it was clear that there were different races sharing a continent. Secondly, there is continuity in genetic variations even in the socially defined race groupings.

This implies that even in people within the same race, there were distinct racial differences hence begging the question whether the socially defined race was actually a biologically unifying factor. Biologists estimate that 85% of total biological variations exist within a unitary local population. This means that the differences among a racial group such as Caucasians are much more compared to those obtained from the difference between the Caucasians and Africans (Sternberg, Elena & Kidd, 2005, p49).

In addition, biologists found out that the various races were not distinct but rather shared a single lineage as well as a single evolutionary path. Therefore there is no proven genetic value derived from the concept of race. Other scientists have declared that there is absolutely no scientific foundation linking race, intelligence and genetics.

Still, a trait such as skin color is completely independent of other traits such as eye shape, blood type, hair texture and other such differences. This means that it cannot be correct to group people using a group of features (Race the power of an illusion, 2010, par3).

What is clear to all is that all human beings in the modern day belong to the same biological sub-species referred to biologically as Homo sapiens sapiens. It has been proven that humans of different races are at least four times more biologically similar in comparison to the different types of chimpanzees which would ordinarily be seen as being looking alike.

It is clear that the original definition of race in terms of the external features of the facial formation and skin color did not capture the scientific fact which show that the genetic differences which result to these changes account to an insignificant proportion of the gene controlling the human genome.

Despite the fact that it is clear that race is not biological, it remains very real. It is still considered an important factor which gives people different levels of access to opportunities. The most visible aspect is the enormous advantages available to white people. This cuts across many sectors of human life and affects all humanity regardless of knowledge of existence.

This being the case, I find it difficult to understand the source of great social tensions across the globe based on race and ethnicity. There is enormous evidence of people being discriminated against on the basis of race. In fact countries such as the US have legislation guarding against discrimination on basis of race in different areas.

The findings define a stack reality which must be respected by all human beings. The idea of view persons of a different race as being inferior or superior is totally unfounded and goes against scientific findings.

Consequently these facts offer a source of unity for the entire humanity. Humanity should understand the need to scrap the racial boundaries not only for the sake of peace but also for fairness. Just because someone is white does not imply that he/she is closer to you than the black one. This is because it could even be true that you have more in common with the black one than the white one.

Reference List

Origin of the Races, 2010. Race Facts. Web.

Race the power of an illusion, 2010. What is race? . Web.

Sternberg, J., Elena L. & Kidd, K. 2005. Intelligence, Race, and Genetics. The American Psychological Association Vol. 60(1), 46–59 . Web.

- Racial Disparities in American Justice System

- How Homo Sapiens Influenced Felis Catus

- Evidence of the Evolutionary Process

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Multi-Occupancy Buildings: Community Safety

- Friendship's Philosophical Description

- Gender Stereotypes on Television

- Karen Springen's "Why We Tuned Out"

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 18). Race and Ethnicity. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/

"Race and Ethnicity." IvyPanda , 18 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Race and Ethnicity'. 18 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Race and Ethnicity." May 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

1. IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." May 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Race and Ethnicity." May 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/race-and-ethnicity/.

- Teaching Resources

- Upcoming Events

- On-demand Events

The Concept of Race

Published: March 13, 2018

- facebook sharing

- email sharing

At a Glance

- Social Studies

- The Holocaust

About This Lesson

In the previous lesson, students began the “We and They” stage of the Facing History scope and sequence by examining the human behavior of creating and considering the concept of universe of obligation . This lesson continues the study of “We and They,” as students turn their attention to an idea—the concept of race —that has been used for more than 400 years by many societies to define their universes of obligation. Contrary to the beliefs of many people, past and present, race has never been scientifically proven to be a significant genetic or biological difference in humans. The concept of race was in fact invented by society to fulfill its need to justify disparities in power and status among different groups. The lack of scientific evidence about race undermines the very concept of the superiority of some “races” and the inferiority of other “races.”

Race is an especially crucial concept in any study of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, because it was central to Nazi ideology. However, the Nazis weren’t the only ones who had notions about race. This lesson also examines the history and development of the idea of “race” in England and the United States.

Essential Questions

Unit Essential Question: What does learning about the choices people made during the Weimar Republic, the rise of the Nazi Party, and the Holocaust teach us about the power and impact of our choices today?

Guiding Questions

- What is race? What is racism? How do ideas about race affect how we see others and ourselves?

- How have race and racism been used by societies to define their universes of obligation?

Learning Objectives

Students will define and analyze the socially constructed meaning of race, examining how that concept has been used to justify exclusion, inequality, and violence throughout history.

What's Included

This lesson is designed to fit into one 50-min class period and includes:

- 6 activities

- 1 teaching strategy

- 2 assessments

- 2 extension activities

Additional Context & Background

For at least 400 years, a theory of “race” has been a lens through which many individuals, leaders, and nations have determined who belongs and who does not. Theories about “race” include the notion that human beings can be classified into different races according to certain physical characteristics, such as skin color, eye shape, and hair form. The theory has led to the common, but false, belief that some “races” have intellectual and physical abilities that are superior to those of other “races.” Biologists and geneticists today have not only disproved this claim, they have also declared that there is no genetic or biological basis for categorizing people by race. According to microbiologist Pilar Ossorio:

Are the people who we call Black more like each other than they are like people who we call white, genetically speaking? The answer is no. There’s as much or more diversity and genetic difference within any racial group as there is between people of different racial groups. 1

As professor Evelynn Hammonds states in the film Race: The Power of an Illusion : “Race is a human invention. We created it, and we have used it in ways that have been in many, many respects quite negative and quite harmful.” 2

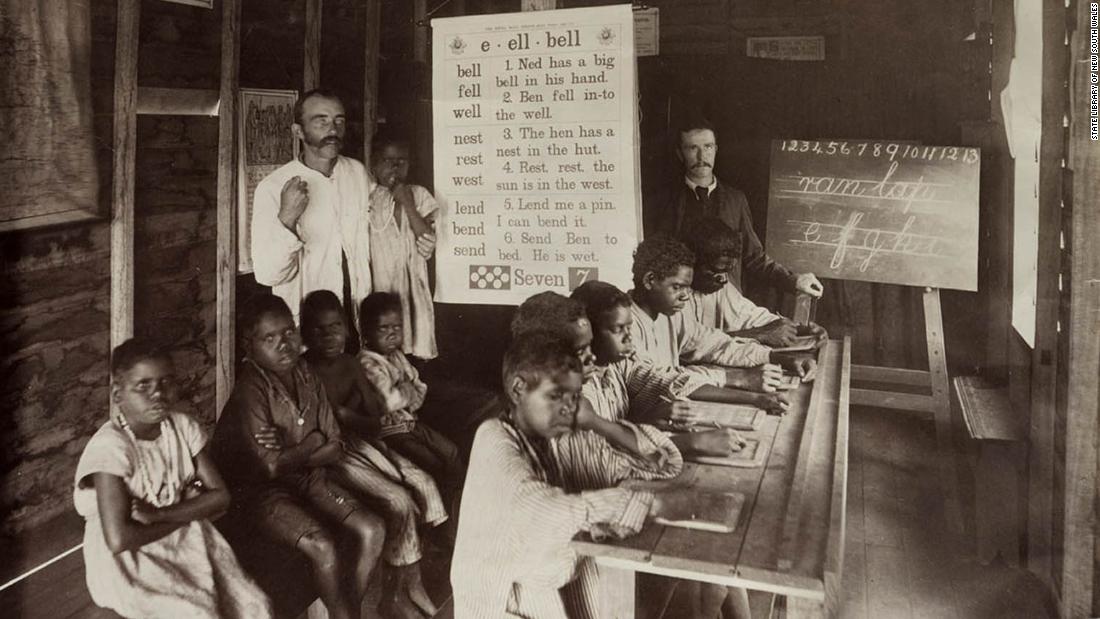

When the scientific and intellectual ideals of the Enlightenment came to dominate the thinking of most Europeans in the 1700s, they exposed a basic contradiction between principle and practice: the enslavement of human beings. Despite the fact that Enlightenment ideals of human freedom and equality inspired revolutions in the United States and France, the practice of slavery persisted throughout the United States and European empires. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, American and European scientists tried to explain this contradiction through the study of “race science,” which advanced the idea that humankind is divided into separate and unequal races. If it could be scientifically proven that Europeans were biologically superior to those from other places, especially Africa, then Europeans could justify slavery and other imperialistic practices.

Prominent scientists from many countries, including Sweden, the Netherlands, England, Germany, and the United States, used “race science” to give legitimacy to the race-based divisions in their societies. Journalists, teachers, and preachers popularized their ideas. Historian Reginald Horsman, who studied the leading publications of the time, describes the false messages about race that were pervasive throughout the nineteenth century:

One did not have to read obscure books to know that the Caucasians were innately superior, and that they were responsible for civilization in the world, or to know that inferior races were destined to be overwhelmed or even to disappear. 3

Some scientists and public figures challenged race science. In an 1854 speech, Frederick Douglass, the formerly enslaved American political activist, argued:

The whole argument in defense of slavery becomes utterly worthless the moment the African is proved to be equally a man with the Anglo-Saxon. The temptation, therefore, to read the Negro out of the human family is exceedingly strong. 4

Douglass and others who spoke out against race science were generally ignored or marginalized.

By the late 1800s, the practice of eugenics emerged out of race science in England, the United States, and Germany. Eugenics is the use of so-called science to improve the human race, both by breeding “society’s best with the best” and by preventing “society’s worst” from breeding at all. Eugenicists believed that a nation is a biological community that must be protected from “threat,” which they often defined as mixing with allegedly inferior “races.”

In the early twentieth century, influential German biologist Ernst Haeckel divided humankind into races and ranked them. In his view, “Aryans”—a mythical race from whom many northern Europeans believed they had descended—were at the top of the rankings and Jews and Africans were at the bottom. Ideas of race and eugenics would become central to Nazi ideology in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

Despite the fact that one’s race predicts almost nothing else about an individual’s physical or intellectual capacities, people still commonly believe in a connection between race and certain biological abilities or deficiencies. The belief in this connection leads to racism. As scholar George Fredrickson explains, racism has two components: difference and power.

It originates from a mindset that regards “them” as different from “us” in ways that are permanent and unbridgeable. This sense of difference provides a motive or rationale for using our power advantage to treat the...Other in ways that we would regard as cruel or unjust if applied to members of our own group. 5

The idea that there is an underlying biological link between race and intellectual or physical abilities (or deficiencies) has persisted for hundreds of years. Learning that race is a social concept, not a scientific fact, may be challenging for students. They may need time to absorb the reality behind the history of race because it conflicts with the way many in our society understand it.

- 1 Pilar Ossorio, Race: The Power of an Illusion , Episode 1: “The Difference Between Us” (California Newsreel, 2003), transcript accessed May 2, 2016.

- 2 Evelynn Hammonds, interview, Race: The Power of an Illusion, Episode 1: “The Difference Between Us (California Newsreel, 2003), transcript accessed April 12, 2017.

- 3 Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), 157.

- 4 Frederick Douglass, The Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered: An Address Before the Literary Societies of Western Reserve College, at Commencement, July 12, 1854 (Rochester, NY: Lee, Mann & Co., 1854), 8–9.

- 5 George M. Fredrickson, Racism: A Short History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), 9.

Preparing to Teach

A note to teachers.

Before teaching this text set, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Navigating Race

Race and racism are often difficult subjects for teachers and students to navigate. For this reason, you may want to briefly return to the class contract and to the agreed-upon norms of classroom discussion at the beginning of this lesson. You may also want to explore the lesson Preparing Students for Difficult Conversations (specifically Activities 2 and 3) for additional strategies and guidance.

That the meaning of race is socially, rather than scientifically, constructed is a new and complex idea for many students and adults that can challenge long-held assumptions. Therefore, we recommend providing opportunities for students to process, reflect, and ask questions about what they’ve learned in this lesson. The exit tickets teaching strategy used in the Assessment section is one way to achieve this, but you could also use the 3-2-1 strategy to elicit reflections and feedback from students.

Related Materials

- Lesson Preparing Students for Difficult Conversations

- Teaching Strategy Exit Tickets

- Teaching Strategy 3-2-1

Previewing Vocabulary

The following are key vocabulary terms used in this lesson:

Add these words to your Word Wall , if you are using one for this unit, and provide necessary support to help students learn these words as you teach the lesson.

- Teaching Strategy Word Wall

Save this resource for easy access later.

Lesson plans.

Opener: One of These Things Is Not Like the Others

- Race is one of the concepts that societies have created to sort and categorize their members. Before discussing race, this brief opening activity introduces students to the idea that when we sort and categorize the things and people around us, we make judgments about which characteristics are more meaningful than others. Students will be asked to look at four shapes and decide which is not like the others, but in doing so they must also choose the category on which they will base their decision.

- Share with students the handout Which of These Things Is Not Like the Others? If possible, you might simply project the image in the classroom.

- Ask students to answer the question by identifying the object in the image that is not like the others.

- Prompt students to share their answers and explain their thinking behind the answer to a classmate, using the Think, Pair, Share strategy. What criterion did they use to identify one item as different? Why? Did their partner use the same criterion?

- Explain that while students’ choices in this exercise are relatively inconsequential, we make similar choices with great consequence in the ways that we define and categorize people in society. While there are many categories we might use to describe differences between people, society has given more meaning to some types of difference (such as skin color and gender) and less meaning to others (such as eye and hair color). You might ask students to brainstorm some of the categories of difference that are meaningful in our society.

- Teaching Strategy Think-Pair-Share

- Handout Which One of These Things Is Not Like the Others?

Reflect on the Meaning of Race

- Tell students that in this lesson, they will look more closely at a concept that has been used throughout history by groups and countries to shape their universes of obligation: the concept of race. Race is a concept that continues to significantly influence the way that society is structured and the way that individuals think about and act toward one another.

- Before asking students to examine the concept closely in this lesson, it is worth giving them a few minutes to write down their own thoughts and assumptions about what race is and what it means. Share the following questions with students, and give them a few minutes to privately record their responses in their journals. Let them know that they will not be asked to share their responses. What is race? What, if anything, can one’s race tell you about a person? How might this concept impact how you think about others or how others think about you?

Learn about the History of “Race”

- Show students a short clip from the film Race: The Power of an Illusion (“The Difference Between Us,” from 07:55 to 13:10). Before you start the clip, pass out the Race: The Power of an Illusion Viewing Guide and preview the questions with students.

- Instruct students to take notes in response to the viewing guide questions as they watch the clip. If time permits, consider showing the clip a second time to help students gather additional details and answer the questions more thoroughly.

- Race is not meaningful in a biological sense.

- It was created rather than discovered by scientists and has been used to justify existing divisions in society.

- Video Race: The Power of an Illusion (The Difference Between Us)

Explore the Meaning of Racism

- Pass out the Race and Racism handout. Alternatively, you might project the handout in the classroom and instruct students to copy down Frederickson’s definition of racism into their journals.

- Circle any words that you do not understand in the definition.

- Underline three to four words that you think are crucial to understanding the meaning of racism .

- Below the definition, rewrite it in your own words.

- At the bottom of the page, write at least one synonym (or other word closely related to racism ) and one antonym.

- Allow a few minutes after this activity to discuss students’ answers and clear up any words they did not understand.

Consider the Impact of Racism

- What has been the impact of racism on Delpit? How has racism influenced the ways that people think and act toward her?

- How has racism affected how Delpit thinks about herself? According to her observations, how has racism affected how other African Americans think about themselves?

- How does racism affect how a society defines its universe of obligation?

- Reading Growing Up with Racism

Reflect on the Impact of Categorizing People

Finish the lesson by asking students to respond to the following prompt:

When is it harmful to point out the differences between people? When is it natural or necessary? Is it possible to divide people into groups without privileging one group over another?

If you would like to use this response as an assessment, consider asking students to complete it on a separate sheet of paper for you to collect. You might also ask students to complete the reflection for homework.

Check for Understanding

- Use the handouts in this lesson to help you gauge students’ understanding of the concept of race. The viewing guide to Race: The Power of an Illusion provides a window into the evolution of students’ understanding in the middle of the lesson, while the student-annotated Race and Racism handout can help you see their ability to articulate their understanding of these concepts.

- Read students’ written reflection from the end of the lesson to help you see how they are thinking about the broader patterns of human behavior—categorizing ourselves and collecting ourselves into groups—discussed in this lesson.

Extension Activities

View A Class Divided

The streaming video A Class Divided (53:53) provides a powerful example of how dividing people by seemingly arbitrary characteristics can affect how they think about and act toward themselves and others. It tells the story of teacher Jane Elliott’s second-grade classroom experiment in which she temporarily separated her students by eye color. Consider showing this compelling video to deepen your class discussion of why people create groups and why that behavior matters.

- Video A Class Divided

Go Deeper in Holocaust and Human Behavior

Another way to deepen the discussion of groups and belonging in this lesson is to introduce additional readings from Chapter 2 of Holocaust and Human Behavior for student discussion and reflection. The reading What Do We Do with a Difference? includes a poem that raises important questions about the ways we respond to differences. Other readings in the chapter trace the evolution of the concept of race during the Enlightenment and the emergence of “race science” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- Reading What Do We Do with a Difference?

Materials and Downloads

Quick downloads, download the files, get files via google, explore the materials, race: the power of an illusion (the difference between us).

Growing Up with Racism

Introducing the writing prompt.

The Roots and Impact of Antisemitism

You might also be interested in…

Dismantling democracy, do you take the oath, european jewish life before world war ii, exploring identity, the holocaust: bearing witness, how should we remember, introducing the unit, the holocaust: the range of responses, kristallnacht, laws and the national community, the power of propaganda, responding to a refugee crisis, unlimited access to learning. more added every month..

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

Working for justice, equity and civic agency in our schools: a conversation with clint smith, centering student voices to build community and agency, inspiration, insights, & ways to get involved.

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are, but rather sets of actions that people do. Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

A collection of new essays by an interdisciplinary team of authors that gives a comprehensive introduction to race and ethnicity. Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are , but rather sets of actions that people do . Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences: Volume I (2001)

Chapter: 8. the changing meaning of race, 8 the changing meaning of race.

Michael A.Omi

T he 1997 President’s Initiative on Race elicited numerous comments regarding its intent and focus. One such comment was made by Jefferson Fish, a psychologist at St. John’s University in New York, who said: “This dialogue on race is driving me up the wall. Nobody is asking the question, ‘What is race?’ It is a biologically meaningless category” (quoted in Petit, 1998:A1).

Biologists, geneticists, and physical anthropologists, among others, long ago reached a common understanding that race is not a “scientific” concept rooted in discernible biological differences. Nevertheless, race is commonly and popularly defined in terms of biological traits—phenotypic differences in skin color, hair texture, and other physical attributes, often perceived as surface manifestations of deeper, underlying differences in intelligence, temperament, physical prowess, and sexuality. Thus, although race may have no biological meaning, as used in reference to human differences, it has an extremely important and highly contested social one.

Clearly, there is an enormous gap between the scientific rejection of race as a concept, and the popular acceptance of it as an important organizing principle of individual identity and collective consciousness. But merely asserting that race is socially constructed does not get at how specific racial concepts come into existence, what the fundamental determinants of racialization are, and how race articulates with other major axes of stratification and “difference,” such as gender and class. Each of these topics would require an extensive treatise on possible variables

shaping our collective notions of race. The following discussion is much more modest.

I attempt to survey ways of thinking about, bringing into context, and interrogating the changing meaning of race in the United States. My intent is to raise a series of points to be used as frames of reference, to facilitate and deepen the conversation about race.

My general point is that the meaning of race in the United States has been and probably always will be fluid and subject to multiple determinations. Race cannot be seen simply as an objective fact, nor treated as an independent variable. Attempting to do so only serves, ultimately, to emphasize the importance of critically examining how specific concepts of race are conceived of and deployed in areas such as social-science research, public-policy initiatives, cultural representations, and political discourse. Real issues and debates about race—from the Federal Standards for Racial and Ethnic Classification to studies of economic inequality—need to be approached from a perspective that makes the concept of race problematic.

A second point is the importance of discerning the relationship between race and racism, and being attentive to transformations in the nature of “racialized power.” The distribution of power—and its expression in structures, ideologies, and practices at various institutional and individual levels—is significantly racialized in our society. Shifts in what “race” means are indicative of reconfigurations in the nature of “racialized power” and emphasize the need to interrogate specific concepts of racism.

GLOBAL AND NATIONAL RACIAL CHANGE

The present historical moment is unique, with respect to racial meanings. Since the end of World War II, there has been an epochal shift in the global racial order that had persisted for centuries (Winant and Seidman, 1998). The horrors of fascism and a wave of anticolonialism facilitated a rupture with biologic and eugenic concepts of race, and challenged the ideology(ies) of White supremacy on a number of important fronts. Scholarly projects in genetics, cultural anthropology, and history, among others, were fundamentally rethought, and antiracist initiatives became a crucial part of democratic political projects throughout the world.

In the United States, the Civil Rights Movement was instrumental in challenging and subsequently dismantling patterns of Jim Crow 1 segrega-

|

| The original “Jim Crow” was a character in a nineteenth-century minstrel act, a stereotype of a Black man. As encoded in laws sanctioning ethnic discrimination, the phrase refers to both legally enforced and traditionally sanctioned limitations of Blacks’ rights, primarily in the U.S. South. |

tion in the South. The strategic push of the Movement in its initial phase was toward racial integration in various institutional arenas—e.g., schools, public transportation, and public accommodations—and the extension of legal equality for all regardless of “color.” This took place in a national context of economic growth and the expansion of the role and scope of the federal government.

Times have changed and ironies abound. Domestic economic restructuring and the transnational flow of capital and labor have created a new economic context for situating race and racism. The federal government’s ability to expand social programs, redistribute resources, and ensure social justice has been dramatically curtailed by fiscal constraints and the rejection of liberal social reforms of the 1960s. Demographically, the nation is becoming less White and the dominant Black-White paradigm of race relations is challenged by the dramatic growth and increasing visibility of Hispanics and Asians.

All these changes have had a tremendous impact on racial identity, consciousness, and politics. Racial discourse is now littered with confused and contradictory meanings. The notion of “color-blindness” is now more likely to be advanced by political groups seeking to dismantle policies, such as affirmative action, initially designed to mitigate racial inequality. Calls to get “beyond race” are popularly expressed, and any hint of race consciousness is viewed as racism.

In this transformed political landscape, traditional civil rights organizations have experienced a crisis of mission, political values, and strategic orientation. Integrationist versus “separate-but-equal” remedies for persistent racial disparities have been revisited in a new light. More often the calls are for “self-help” and for private support to tackle problems of crime, unemployment, and drug abuse. The civil rights establishment confronts a puzzling dilemma—formal, legal equality has been significantly achieved, but substantive racial inequality in employment, housing, and health care remains, and in many cases, has deepened.

All this provides an historical context in which to situate evolving racial meanings. Over the past 50 years, changes in the meaning of race have been shaped by, and in turn have shaped, broader global/epochal shifts in racial formation. The massive influx of new immigrant groups has destabilized specific concepts of race, led to a proliferation of identity positions, and challenged prevailing modes of political and cultural organization.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE AND RACIAL TRANSFORMATION

In a discussion of Asian American cultural production and political formation, Lowe (1996) uses the concepts of heterogeneity, hybridity, and multiplicity to disrupt popular notions of a singular, unified Asian Ameri-

can subject. Refashioning these concepts, I use them to assess the changes in, and issues relevant to, racial meaning created by demographic shifts.

Heterogeneity

Lowe defines heterogeneity as “the existence of differences and differential relationships within a bounded category” (1996:67). Over the past several decades, there has been increasing diversity among so-called racial groups. Our collective understanding of who Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians are has undergone a fundamental revision as new groups entered the country. The liberalization of immigration laws beginning in 1965, political instability in various areas of the world, and labor migration set in motion by global economic restructuring all contributed to an influx of new groups—Laotians, Guatemalans, Haitians, and Sudanese, among others.

In the United States, many of these immigrants encounter an interesting dilemma. Although they may stress their national origins and ethnic identities, they are continually racialized as part of a broader group. Many first-generation Black immigrants from, for example, Jamaica, Ethiopia, or Trinidad, distance themselves from, subscribe to negative stereotypes of, and believe that, as ethnic immigrants, they are accorded a higher status than, Black Americans (Kasinitz, 1992). Children of Black immigrants, who lack their parents’ distinctive accents, have more choice in assuming different identities (Waters, 1994). Some try to defy racial classification as “Black Americans” by strategically asserting their ethnic identity in specific encounters with Whites. Others simply see themselves as “Americans.”

Panethnic organization and identity constitute one distinct political/ cultural response to increasing heterogeneity. Lopez and Espiritu define panethnicity as “the development of bridging organizations and solidarities among subgroups of ethnic collectivities that are often seen as homogeneous by outsiders” (1990:198); such a development, they claim, is a crucial feature of ethnic change, “supplanting both assimilation and ethnic particularism as the direction of change for racial/ethnic minorities” (1990:198).

Omi and Winant (1996) describe the rise of panethnicity as a response to racialization, driven by a dynamic relationship between the group being racialized and the state. Elites representing panethnic groups find it advantageous to make political demands backed by the numbers and resources panethnic formations can mobilize. The state, in turn, can more easily manage claims by recognizing and responding to large blocs, as opposed to dealing with specific claims from a plethora of ethnically defined interest groups. Different dynamics of inclusion and exclusion

are continually expressed. Conflicts often occur over the precise definition and boundaries of various racially defined groups and their adequate representation in census counts, reapportionment debates, and minority set-aside programs. The increasing heterogeneity of racial categories raises several questions for research to answer.

How do new immigrant groups negotiate the existing terrain of racial meanings? What transformations in racial self-identity take place as immigrants move from a society organized around one concept of race, to a new society with a different mode of conceptualization? Oboler (1995), for example, explores how Latin Americans “discover” the salience of race and ethnicity as a form of social classification in the United States.

Under what conditions can we imagine panethnic formations developing, and when are ethnic-specific identities maintained or evoked? Conflicts over resources within presumed homogeneous racial groups can be quite sharp and lead to distinctive forms of political consciousness and organization.

Under what conditions does it make sense to talk about groups such as Asians and Pacific Islanders, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Hispanics, Blacks, etc., and when is it important to disaggregate the various national-origin groups, ethnic groups, and tribes that make up these panethnic formations?

Researchers and policy makers need to be attentive to the increasing heterogeneity of racial/ethnic groups and assess how an examination of “differences” might help us rethink the nature and types of questions asked about life chances, forms of inequality, and policy initiatives.

Crouch, in his essay “Race Is Over” (1996), speculates that in the future, race will cease to be the basis of identity and “special-interest power” because of the growth in mixed-race people. It has been a longstanding liberal dream, most recently expressed by Warren Beatty in the film Bulworth, that increased “race mixing” would solve our racial problems. Multiraciality disrupts our fixed notions about race and opens up new possibilities with respect to dialogue and engagement across the color line. It does not, however, mean that “race is over.”

Although the number of people of “mixed-racial descent” is unclear, and contingent on self-definition, the 1990 census counted two million children (under the age of 18) whose parents were of different races (Marriott, 1996). The demographic growth and increased visibility of

“mixed-race” or “multiracial” individuals has resulted in a growing literature on multiracial identity and its meaning for a racially stratified society (Root, 1992; Zack, 1994).

In response to these demographic changes, there was a concerted effort from school boards and organizations such as Project RACE (Reclassify All Children Equally) to add a “multiracial” category to the 2000 Census form (Mathews, 1996). This was opposed by many civil rights organizations (e.g., Urban League, National Council of La Raza) who feared a reduction in their numbers and worried that such a multiracial category would spur debates regarding the “protected status” of groups and individuals. According to various estimates, 75 to 90 percent of those who now check the “Black” box could check a multiracial one (Wright, 1994). In pretests by the Census Bureau in 1996, however, only 1 percent of the sample claimed to be multiracial (U.S Bureau of the Census, 1996).

In October 1997, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) decided to allow Americans the option of multiple checkoffs on the census with respect to the newly modified racial and ethnic classifications (Holmes, 1997). Initial debate centered on how to count people who assigned themselves to more than one racial/ethnic category. At issue is not only census enumeration, but also its impact on federal policies relevant to voting rights and civil rights.

It remains to be seen how many people will actually identify themselves as members of more than one race. Much depends on the prevailing consciousness of multiracial identity, the visibility of multiracial people, and representational practices. As Reynolds Farley notes, “At the time of the 2000 census, if we have another Tiger Woods…those figures could up to 5 percent—who knows?” (quoted in Holmes, 1997:A19).

The debate over a multiracial category reveals an intriguing aspect about our conceptualizations of race. The terms “mixed race” or “multiracial” in themselves imply the existence of “pure” and discrete races. By drawing attention to the socially constructed nature of “race,” and the meanings attached to it, multiraciality reveals the inherent fluidity and slipperiness of our concepts of race. Restructuring concepts of race has a number of political implications. House Speaker Newt Gingrich (1997), for example, used the issue of multiraciality to illustrate the indeterminacy of racial categories and to vigorously advocate for their abolition in government data collection, much as advocates of color-blindness do.

In her definition of hybridity, Lowe refers to the formation of material culture and practices “produced by the histories of uneven and unsynthetic power relations” (Lowe, 1996:67). Indeed, the question of power cannot be elided in the discussion of multiraciality because power is deeply implicated in racial trends and in construction of racial mean-

ings. The rigidity of the “one-drop rule,” 2 long-standing fears of racial “pollution,” and the persistence (until the Loving decision in 1967) of antimiscegenation laws demonstrate the ways in which the color line has been policed in the United States. This legacy continues to affect trends in interracial marriage. Lind (1998) suggests that both multiculturalists and nativists have misread trends, and that a new dichotomy between Black and non-Blacks is emerging. In the 21st century, he envisions “a White-Asian-Hispanic melting-pot majority—a hard-to-differentiate group of beige Americans—offset by a minority consisting of Blacks who have been left out of the melting pot once again” (p. 39). Such a dire racial landscape raises a number of troubling political questions regarding group interests, the distribution of resources, and the organization of power.

Simultaneously, racial hybridity reveals the fundamental instability of all racial categories, helps us discern particular dimensions of racialized power, and raises a host of political issues.

How, when, and under what conditions, do people choose to identify as “mixed race”? According to the Bureau of the Census the American Indian population increased 255 percent between 1960 and 1990 as a result of changes in self-identification. What factors contributed to this shift?

What effects do multiracial identity and classification have on existing “race-based” public policies? Although most forms of race-based policies are under attack, a vast structure of bureaucracies, policies, and practices exists within government, academic, and private sectors that relies on discrete racial categories. Who, for example, would be considered an “underrepresented minority” and under what circumstances?

Although there has been a significant growth in the literature on multiraciality, much of it has not deeply examined the racial meanings that pervade distinctive “combinations” of multiracial identity. The experience of being White-Asian in most college/university settings is significantly different from being Black-Asian. Some groups, such as Black Cubans in Miami, encounter marginalization from both Black and Hispanic American communities (Navarro, 1997). We need to deconstruct multiraciality and understand the racial meanings that correspond to specific types of multiracial identities and classifications.

The repeal of antimiscegenation laws, the marked lessening of social distance between racial groups, and interracial marriage among specific

|

| A person was legally Negroid, regardless of actual physical appearance, if there were any proof of African ancestry—i.e., one drop of African blood. |

groups have contributed to the growth and increased visibility of a multiracial population. Studies thus far have focused on “cultural conflict” and psychological issues of individual adjustment. We need to assess more deeply how multiraciality affects the logic and organization of data on racial classification, and the political and policy issues that emanate from this.

Multiplicity

It is, by now, obvious that the racial composition of the nation has been radically changing. In seven years, Hispanics will surpass Blacks as the largest “minority group” in the United States (Holmes, 1998). Trends in particular states and regions are even more dramatic. In 1970, Whites constituted 77 percent of the San Francisco Bay Area’s population. Hispanics and Asians constituted 11 and 4 percent, respectively, of the population (McLeod, 1998). In 1997, Whites constituted 54 percent, and Hispanics and Asians each comprised nearly 20 percent of the population.

Much has been made in the popular literature about the “changing face of America,” but little has been said about how the increasing multiplicity of groups shapes our collective understanding about race. Specifically, how are the dominant paradigms of race relations affected by these demographic realities?

At the first Advisory Board meeting of the President’s Initiative on Race (July 14, 1997), a brief debate ensued among the panelists. Linda Chavez-Thompson argued that the “American dilemma” had become a proliferation of racial and ethnic dilemmas. Angela Oh argued that the national conversation needed to move beyond discussions of racism as solely directed at Blacks. Advisory Board chairman John Hope Franklin, by contrast, affirmed the historical importance of Black-White relations and stressed the need to focus on unfinished business. Although the Board members subsequently downplayed their differences, their distinct perspectives continued to provoke debate within academic, policy, and community activist settings regarding the Black-White race paradigm.

How we think about, engage, and politically mobilize around racial issues have been fundamentally shaped by a prevailing “Black-White” paradigm of race relations. Historical accounts of other people of color in the United States are cast in the shadows of the Black-White encounter. Contemporary conflicts between a number of different racial/ethnic groups are understood in relationship to Black-White conflict, and the media uses the bipolar model as a master frame to present such conflicts.

Such biracial theorizing misses the complex nature of race relations in post-Civil Rights Movement America. Complex patterns of conflict and accommodation have developed among multiple racial/ethnic groups.

In many major U.S. cities, Whites have fled to suburbia, leaving the inner city to the turf battles among different racial minorities for housing, public services, and economic development.

The dominant mode of biracial theorizing ignores the fact that a range of specific conditions and trends—such as labor-market stratification and residential segregation—cannot be adequately studied by narrowly assessing the relative situations of Whites and Blacks. Working within a “two-nations” framework of Black and White, Hacker (1992) needs to consider Asians in higher education at some length in order to address the issue of race-based affirmative action.

In suggesting that we get beyond the Black-White paradigm, I’m conscious of the consequences of such a move. On the one hand, I do not mean to displace or decenter the Black experience, which continues to define the fundamental contours of race and racism in our society. On the other hand, I do want to suggest that the prevailing Black-White model tends to marginalize, if not ignore, the experiences, needs, and political claims of other racialized groups. The challenge is to frame an appropriate language and analysis to help us understand the shifting dynamic of race that all groups are implicated in.

We would profit from more historical and contemporary studies that look at the patterns of interaction between, and among, a multiplicity of groups. Almaguer (1994), in his study of race in nineteenth-century California, breaks from the dominant mode of biracial theorizing to illustrate how American Indians, Mexicans, Chinese, and Japanese were racialized and positioned in relation to one another by the dominant Anglo elite. Horton (1995) takes a look at distinct sites of political and cultural engagement between different groups in Monterey Park, California—a city where Asians constitute the majority population. Such studies emphasize how different groups shape the conditions of each other’s existence.

Research needs to consider how specific social policies (e.g., affirmative action, community economic development proposals) have different consequences for different groups. The meaning and impact of immigration reforms for Hispanics, for example, may be quite distinct from its meaning and impact for Asians. In line with an eye toward heterogeneity, different ethnic groups (e.g., Cubans and Salvadorans) within a single racial category (Hispanic) may be differentially affected by particular policy initiatives and reforms. All this is important because politics, policies, and practices framed in dichotomous Black-White terms miss the ways in which specific initiatives structure the possibilities for conflict or accommodation among different racial minority groups.

The multiplicity of groups has transformed the nation’s political and cultural terrain, and provoked a contentious debate regarding multiculturalism. New demographic realities have also provided a distinctive

context in which to examine the changing dynamics of White racial identity. Both the debate over multiculturalism and the increasing salience of White racial identity are tied to changes in the meaning of race as a result of challenges to the logic and organization of White supremacy.

MULTICULTURALISM AND WHITENESS

Controversies over the multiculturalism have been bitter and divisive. Proponents claim that a multicultural curriculum, for example, can facilitate an appreciation for diversity, increase tolerance, and improve relations between and among racial and ethnic groups. Opponents claim that multiculturalists devalue or relativize core national values and beliefs, shamelessly promote “identity politics,” and unwittingly increase racial tensions.

One of problems of the multicultural debate is the conflation of “race” and “culture.” I take seriously Hollinger’s (1995) claim that we have reified what he calls the American “ethno-racial pentagon.” Blacks, Hispanics, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Whites are now seen as the five basic demographic blocs we treat as the subjects of multiculturalism. The problem is that these groups do not represent distinct and mutually exclusive “cultures.” American multiculturalism, Hollinger claims, has accomplished, in short order, a task that centuries of British imperial power could not complete: the making of the Irish as indistinguishable from English. Such a perspective argues for the need to rethink what we mean by the terms “race” and “culture,” and to critically interrogate the manner in which we articulate the connection between the two in research and policy studies.

Another issue is how forms of multiculturalist discourse elide the organization and distribution of power. Multiculturalism is often posed as the celebration of “differences” and unique forms of material culture expressed, for example, in music, food, dance, and holidays. Such an approach tends to level the important differences and contradictions within and among racial and ethnic groups. Different groups possess different forms of power—the power to control resources, the power to push a political agenda, and the power to culturally represent themselves and other groups. In a recent study of perceived group competition in Los Angeles, Bobo and Hutchings (1996) found, among other things, that Whites felt least threatened by Blacks and most threatened by Asians, while Asians felt a greater threat from Blacks than Hispanics. Such distinct perceptions of “group position” are related to, and implicated in, the organization of power.

Some scholars and activists have defined racism as “prejudice plus power.” Using this formula, they argue that people of color can’t be racist

because they don’t have power. But things aren’t that simple. In the post-Civil Rights era, some racial minority groups have carved out a degree of power in select urban areas—particularly with respect to administering social services and distributing economic resources. This has led, in cities like Oakland and Miami, to conflicts between Blacks and Hispanics over educational programs, minority business opportunities, and political power. We need to acknowledge and examine the historical and contemporary differences in power that different groups possess.

Dramatic challenges to ideologies and structures of White supremacy in the past 50 years, have caused some Whites to perceive a loss of power and influence. In 25 years, non-Hispanic Whites will constitute a minority in four states, including two of the most populous ones, and in 50 years, they will make up barely half of the U.S. population (Booth, 1998:A18). Whiteness has lost its transparency and self-evident meaning in a period of demographic transformation and racial reforms. White racial identity has recently been the subject of interrogation by scholars (Roediger, 1991; Lott, 1995; Ignatiev, 1995), who have explored how the social category of “White” has evolved and been implicated with racism and the labor movement. Contemporary works look at how White racial identities are constructed, negotiated, and transformed in institutional and everyday life (Hill, 1997).

Research on White Americans suggests that they do not experience their ethnicity as a definitive aspect of their social identity (Alba, 1990; Waters 1990). Rather, they perceive it dimly and irregularly, picking and choosing among its varied strands that allow them to exercise an “ethnic option” (Waters, 1990). Waters found that ethnicity was flexible, symbolic, and voluntary for her White respondents in ways that it was not for non-Whites.

The loose affiliation with specific European ethnicities does not necessarily suggest the demise of any coherent group consciousness and identity. In the “twilight of ethnicity,” White racial identity may increase in salience. Indeed, in an increasingly diverse workplace and society, Whites experience a profound racialization.

The racialization process for Whites is evident on many college/university campuses as White students encounter a heightened awareness of race, which calls their own identity into question. Focus group interviews with White students at the University of California, Berkeley, reveals many of the themes and dilemmas of White identity in the current period: the “absence” of a clear culture and identity, the perceived “disadvantages” of being White with respect to the distribution of resources, and the stigma of being perceived as the “oppressors of the nation” (Institute for the Study of Social Change, 1991:37). Such comments underscore the new problematic meanings attached to “White,” and debates about the

meanings will continue, and perhaps deepen, in the years to come, fueled by such social issues as affirmative action, English-only initiatives, and immigration policies.

Racial meanings are profoundly influenced by state definitions and discursive practices. They are also shaped by interaction with prevailing forms of gender and class formation. An examination of both these topics reveals the fundamental instability of racial categories, their historically contingent character, and the ways they articulate with other axes of stratification and “difference.” Extending this understanding, it is crucial to relate racial categories and meanings to concepts of racism. The idea of “race” and its persistence as a social category is only given meaning in a social order structured by forms of inequality—economic, political, and cultural—that are organized, to a significant degree, along racial lines.

FEDERAL STANDARDS FOR RACIAL AND ETHNIC CLASSIFICATION

State definitions of race and ethnicity have inordinately shaped the discourse of race in the United States. OMB Statistical Directive 15 (Office of Management and Budget, 1977) was initially issued to create “compatible, nonduplicated, exchangeable racial and ethnic data by Federal agencies” for three reporting purposes—statistical, administrative, and civil rights compliance. The directive has become the de facto standard for state and local agencies, the private and nonprofit sectors, and the research community. Social scientists use Directive 15 categories because data are organized and available under these rubrics.

Since its inception, the Directive has been the subject of debate regarding its conceptual vagueness and the logical flaws in its categorization (Edmonston and Tamayo-Lott, 1996). Some of the categories are racial, some are cultural, and some are geographic. Some groups cannot neatly be assigned to any category. In addition, little attention is given to the gap between state definitions and popular consciousness. Given the social construction of race and its shifting meaning, administrative definitions may not be meaningful to the very individuals and groups they purport to represent (Omi, 1997).

Some politicians and political commentators have seized on the difficulty of establishing coherent racial categories as a reason to call for the abolition of all racial classification and record keeping. Such a move, they argue, would save federal dollars and minimize racial/ethnic distinctions, consciousness, and divisive politics. In 1997, the American Anthropological Association counseled the federal government to phase out use of the term “race” in the collection of data because the concept has no scientific justification in human biology (Overbey, 1997). The problem is,

social concepts of race are still linked to forms of discrimination. Abolishing data-collection efforts that use racial categories would make it more difficult for us to track specific forms of discrimination with respect to financial loan practices, health-care delivery, and prison-sentencing patterns among other issues (Berry et al., 1998). The current debate about police “profiling” of Black motorists illustrates the issues involved in racial record keeping (Wilgoren, 1999).

Wishing to preserve racial and ethnic data, some demographers and social scientists argue for categories that are more precise, conceptually valid, exclusive, exhaustive, measurable, and reliable over time. I believe this is an impossible task because it negates the fluidity and transformation of race and racial meanings, and definitions, over time.

The strange and twisted history of the classification of Asian Indians in the United States is instructive. During and after the peak years of immigration, Asian Indians were referred to and classified as “Hindu,” though the clear majority of them were Sikh. In United States v. B.S.Thind (1923), the U.S. Supreme Court held that Thind, as a native of India, was indeed “Caucasian,” but he wasn’t “White” and therefore was ineligible to become a naturalized citizen (p. 213). “It may be true,” the court declared, “that the blond Scandinavian and the brown Hindu have a common ancestor in the dim reaches of antiquity, but the average man knows perfectly well that there are unmistakable and profound differences between them today” (p. 209). Their status as non-White was reversed after World War II when they became “White” in part as reward for their participation in the Pacific war and as a consequence of the postwar climate of anticolonial politics. In the post-Civil Rights era, Asian Indian leaders sought to change their classification in order to seek “minority” group status. In 1977, OMB agreed to reclassify immigrants from India and their descendants from “White/Caucasian” to “Asian Indian.” Currently, many Asian Indians self-identify as “South Asian” to foster panethnic identification with those from Pakistan and Bangladesh, among other countries.

The point of all this is that racial and ethnic categories are often the effects of political interpretation and struggle, and that the categories in turn have political effects. Such an understanding is crucial in the ongoing debates around the federal standards for racial and ethnic classification.

INTERSECTIONALITY

In a critique of racial essentialism, Hall (1996:444) states that “the central issues of race always appear historically in articulation, in a formation, with other categories and divisions and are constantly crossed

and recrossed by categories of class, of gender and ethnicity.” Although this may seem obvious, most social-science research tends to neglect an examination of the connections between distinct, yet overlapping, forms of stratification and “difference.” The result is a compartmentalization of inquiry and analysis. Higginbotham (1993:14) notes that, “Race only comes up when we talk about African Americans and other people of color, gender only comes up when we talk about women, and class only comes up when we talk about the poor and working class.”

Analyses that do grapple with more than one variable frequently reveal a crisis of imagination. Much of the race-class debate, for example, inspired by the work of Wilson (1978), suffers from the imposition of rigid categories and analyses that degenerate into dogmatic assertions of the primacy of one category over the other. In fairness, more recent work has examined the interactive effects of race and class on residential segregation (Massey and Denton, 1993) and inequalities in wealth accumulation (Oliver and Shapiro, 1995). Still, most work treats race and class as discrete and analytically distinct categories.

A new direction is reflected in scholarship that emphasizes the “intersectionality” of race, gender, and class (Collins, 1990). Such work does not simply employ an additive model of examining inequalities (e.g., assessing the relative and combined effects of race and gender “penalties” in wage differentials), but examines how different categories are constituted, transformed, and given meaning in dynamic engagement with each other. Glenn’s (1992, 1999) work on the history of domestic and service work, for example, reveals how race is gendered and gender is raced. Frankenberg (1993) explores the ways in which White women experience, reproduce, and/or challenge the prevailing racial order. In so doing, she reveals how the very notion of racial privilege is experienced and articulated differently by women and men.

In institutional and everyday life, any clear demarcation of specific forms of “difference” is constantly being disrupted. This suggests the importance of understanding how changes in racial meaning are affected by transformations in gender and class relations. New research promises a break with the conception of race, class, and gender as relatively static categories, and emphasizes an approach that looks at the multiple and mutually determining ways that they shape each other. Such a framework of analysis is, however, still tentative, incomplete, and in need of further elaboration and refinement.

RACE AND RACISM

Blauner (1994) notes that in classroom discussions of racism, White and Black students tend to talk past one another. Whites tend to locate

racism in color consciousness and find its absence in color-blindness. In so doing, they see the affirmation of difference and racial identity among racially defined minority students as racist. Black students, by contrast, see racism as a system of power, and correspondingly argue that they cannot be racist because they lack power. Blauner concludes that there are two “languages” of race, one in which members of racial minorities, especially Blacks, see the centrality of race in history and everyday experience, and another in which Whites see race as a peripheral, nonessential reality.

Such discussions remind us of the crucial importance of discerning and articulating the connections between the changing meaning of race and concepts of racism. Increasingly, some scholars argue that the term “racism” has suffered from conceptual inflation, and been subject to so many different meanings as to render the concept useless (Miles, 1989). Recently, John Bunzel, a former member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and current senior research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, argued that the President’s Advisory Board on Race should call for a halt to the use of the term “racism” because it breeds “bitterness and polarization, not a spirit of pragmatic reasonableness in confronting our difficult problems” (Bunzel, 1998:D-7).

In academic and policy circles, the question of what racism is continues to haunt discussions. Prior to World War II, the term “racism” was not commonly used in public discourse or in the social-science literature. The term was originally used to characterize the ideology of White supremacy that was buttressed by biologically based theories of superiority/inferiority. In the 1950s and 1960s, the emphasis shifted to notions of individual expressions of prejudice and discrimination. The rise of the Black power movement in the 1960s and 1970s fostered a redefinition of racism that focused on its institutional nature. Current work in cultural studies looks at the often implicit and unconscious structures of racial privilege and racial representation in daily life and popular culture.

All this suggests that more precise terms are needed to examine racial consciousness, institutional bias, inequality, patterns of segregation, and the distribution of power. Racism is expressed differently at different levels and sites of social activity, and we need to be attentive to its shifting meaning in different contexts. As Goldberg (1990:xiii) states, “the presumption of a single monolithic racism is being displaced by a mapping of the multifarious historical formulations of racisms .”

This intellectual task is wrapped up with, indeed, intrinsically connected to, surveying the changing meaning(s) of race. In a period when major social policies with respect to race are being challenged and rethought, it is crucial to consider how different meanings of race are shaped by, and in turn help shape, different concepts of racism. Being clear about

what we do and do not mean by racism is essential to future dialogues on race—dialogues that need to interrogate the nature of past and present forms of inequality, and the meaning of social justice.

LOOKING BACK, THINKING AHEAD

It is important to consider how unique the current racial context is, and its meaning for theorizing about race. Alba (1998) argues that many commentators and social scientists seize on the increasing complexity of race to reject, in blanket fashion, prior and existing understandings of racial transformation. He urges critical restraint, and states that “the conceptual models we have from the past should not be so quickly eclipsed by the seeming novelty of the present” (p. 7). To buttress his remarks, Alba suggests that we consider a “more refined conception of assimilation” to understand the trajectory of immigrant group incorporation over succeeding generations. Processes of assimilation render demographic projections, and the significance we impute to them, problematic because they rest on the assumption that racial and ethnic categories are stable enclosures. Rather than speak of the decreasing White population, Alba suggests that our collective notion of “majority group” might undergo a profound redefinition as “some Asians and Hispanics join what has been viewed as a ‘White,’ European population” (p. 10).

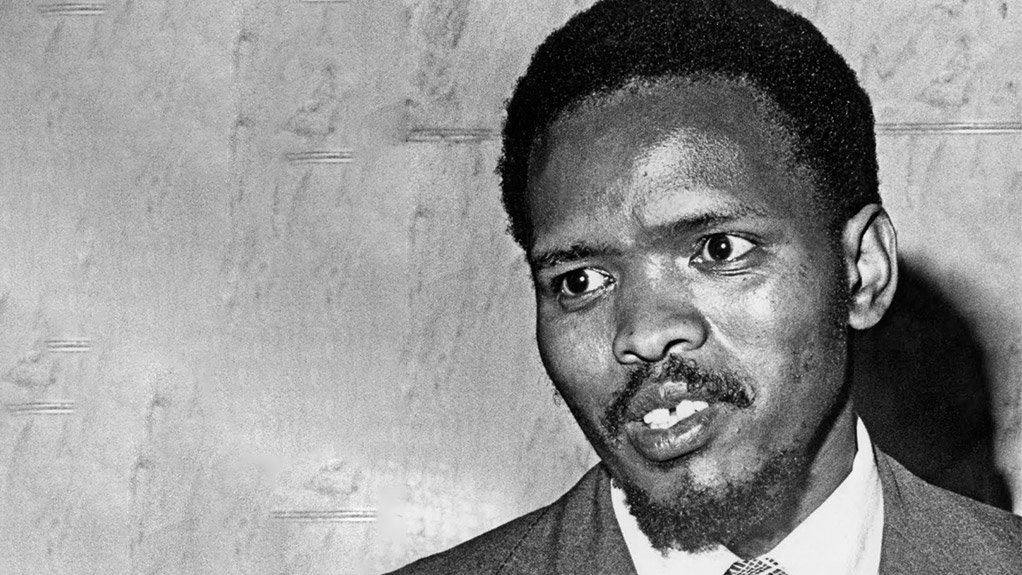

There is much here to consider. First, clearly there are historical continuities in patterns of relevance to race in the United States. The color line was rigidly enforced throughout much of America’s history, and racial inequalities have been stubbornly persistent in the face of political reforms. But I believe the current historical moment is a relatively unique one with respect to racial meanings. Over the past 50 years, White supremacy has been significantly challenged, not only in the United States but on a global scale. Since the end of World War II, there has been an epochal shift in the logic, organization, and practices of the centuries-old global racial order. Opposition to fascism, anticolonial struggles in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States facilitated the rupture with biologic and eugenic concepts of race. In the United States and South Africa, particularly, antiracist initiatives have become crucial elements of an overall project to extend political democracy. These developments provide a unique historical context for understanding the meaning we impart to race.

Second, while older paradigms of race can help us understand what’s going on today, it is important to historically situate various models of race and ethnicity, and see them as reflective of historically specific concerns. The vast influx of different groups of European immigrants at the turn of the century stimulated sociological thinking regarding assimila-

tion and group incorporation into the mainstream of American life. In a similar manner, the current influx of immigrant groups from Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the former Soviet Union, and elsewhere, provides an opportunity to rethink the nature of immigration, identity, and community formation; but the jury is still out on whether older models need to be modified to capture new realities, or if new and radically different models are called for.

Old theories, of course, are often revisited and remodeled. Traditional theories of assimilation, for example, have been substantially revised. No longer is assimilation posed and envisioned as a zero-sum game; the more “assimilated” one is, does mean that one is less “ethnic.” Assimilation is also no longer read as “Anglo conformity”; there is no clearly discernible social and cultural “core” that immigrant groups gravitate toward. Forms of what Portes and Zhou (1993) label “segmented assimilation” are occurring, and they involve complex patterns of accommodation and conflict between increasingly diverse racial and ethnic groups.

That said, it is important to critically examine racial trends and their interpretation through a conceptual framework such as assimilation. What is missing is sufficient attentiveness to the processes of racialization — the ways racial meanings are constructed and imparted to social groups and processes. From an assimilationist vantage point, one could examine the intermarriage patterns among Asians to support the idea of their incorporation into the White mainstream. Indeed some social scientists (Hacker, 1992) believe that increasing Asian-White marriage rates, along with positive trends in income, education, and residential patterns, suggest that Asian Americans are becoming “White” as the very category of “Whiteness” is being expanded.