Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

140k Accesses

221 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Growth mindset and social comparison effects in a peer virtual learning environment

- Pamela Sheffler

- Cecilia S. Cheung

Social Psychology of Education (2024)

Exploring the configurations of learner satisfaction with MOOCs designed for computer science courses based on integrated LDA-QCA method

- Yangcai Xiao

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Nursing students’ learning flow, self-efficacy and satisfaction in virtual clinical simulation and clinical case seminar

- Sunghee H. Tak

BMC Nursing (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Digital learning and transformation of education

Digital technologies have evolved from stand-alone projects to networks of tools and programmes that connect people and things across the world, and help address personal and global challenges. Digital innovation has demonstrated powers to complement, enrich and transform education, and has the potential to speed up progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) for education and transform modes of provision of universal access to learning. It can enhance the quality and relevance of learning, strengthen inclusion, and improve education administration and governance. In times of crises, distance learning can mitigate the effects of education disruption and school closures.

What you need to know about digital learning and transformation of education

2-5 September 2024, UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, France

Digital competencies of teachers

in Member States of the Group of 77 and China

Best practices

The call for applications and nominations for the 2023 edition is open until 21 February 2024

Upcoming events

Open educational resources

A translation campaign to facilitate home-based early age reading

or 63%of the world’s population, were using the Internet in 2021

do not have a household computer and 43% of learners do not have household Internet.

to access information because they are not covered by mobile networks

in sub-Saharan Africa have received minimum training

Contact us at [email protected]

Project-Based Approach to Enhance Online Learning: A Case of Teaching Systems Thinking and System Dynamics Modeling

- First Online: 23 September 2023

Cite this chapter

- Sreenivasulu Bellam 4

103 Accesses

Teaching online poses challenges in terms of meaningful student engagement, physical interactions, and also delivering the content. To keep students actively engaged and motivated for their learning and to achieve the intended learning outcomes of a course, it is essential to implement appropriate learner-centric pedagogy. For this, project-based approach favors collaborative learning in small groups and offers opportunities to engage students for effective and active participation online. Any systems thinking course also requires a project/problem-based approach to enable students to learn to model real-world problems. This chapter presents an example of the implementation of a project-based approach to teach systems thinking and system dynamics modeling while engaging students in online settings. It also focuses on how students can be engaged online effectively to learn collaboratively from the project, and through a workable framework of TPACK. The author integrates content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and technology-enabled learning (TPK) via Zoom as the online platform.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Integrated Experience: Through Project-Based Learning

An Educational Experience with Online Teaching – Not a Best Practice

Project-Based Learning in Higher Education

Anderson, V., & Johnson, L. (1997). Systems thinking basics. From concepts to causal loops . Pegasus Communications.

Google Scholar

Arnold, R. D., & Wade, J. P. (2017). A complete set of systems thinking skills. Insight, 20 (3), 9–17.

Article Google Scholar

Baeten, M., Dochy, F., & Struyven, K. (2013). The effects of different learning environments on students’ motivation for learning and their achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83 (3), 484–501.

Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., & Rumble, M. (2012). Defining twenty-first century skills. In P. Griffin, B. McGaw, & E. Care (Eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 17–66). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Blumberg, P. (2019). Making learning centered teaching work . Stylus Publishing.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26 , 369–398.

Brennan, J. (2020). Engaging Students through Zoom (1st ed.). Wiley.

Butt, A. (2014). Student views on the use of a flipped classroom approach: Evidence from Australia. Business Education and Accreditation, 6 (1), 33–43.

Eker, S., Zimmermann, N., Carnohan, S., & Davies, M. (2018). Participatory system dynamics modeling for housing, energy and wellbeing interactions. Building Research & Information, 46 (7), 738–754.

Forrester, J. W. (1961). Industrial dynamics . M.I.T. Press.

Forrester, J. W. (1971). World dynamics . Pegasus Communications.

Forrester, J. W. (1994). System dynamics, systems thinking, and soft OR. System Dynamics Review, 10 , 245–256.

Garrison, D., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-Learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice . Routledge Falmer.

Book Google Scholar

Garrison, R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles and guidelines . Jossey-Bass.

George, E. M. (2018). Teaching systems thinking to general education students. Ecological Modelling, 373 , 13–21.

Gregory, A., & Miller, S. (2014). Using systems thinking to educate for sustainability in a business school. Systems, 2 , 313–327.

Hall, W., Palmer, S., & Bennett, M. (2012). A longitudinal evaluation of a project-based learning initiative in an engineering undergraduate programme. European Journal of Engineering Education, 37 (2), 155–165.

Hannafin, M. J., & Hannafin, K. M. (2010). Cognition and student-centered web-based learning: Issues and implications for research and theory. In M. Spector, D. Ifenthaler, & Kinshuk (Eds.), Learning and instruction in the digital age (pp. 11–23). Springer.

Jones, L. (2007). The student-centered classroom . Cambridge University Press.

Kanuka, H., & Garrison, D. (2004). Cognitive presence on online learning. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 15 (2), 21–39.

Kim, M., & Hannafin, M. (2011). Scaffolding problem solving in technology-enhanced learning environments (TELEs): Bridging research and theory with practice. Computers and Education, 56 (2), 403–417.

Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9 (1), 60–70.

Krauss, J., & Boss, S. (2013). Thinking through project-based learning: Guiding deeper inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA.

Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer . Chelsea Green Publishing.

Melrose, S., & Bergeron, K. (2007). Instructor immediacy strategies to facilitate group work in online graduate study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technologies, 23 (1), 132–148.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108 (6), 1017–1054.

Munich, K. (2014). Social support for online learning: Perspectives of nursing students. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 29 (2), 1–12.

Palaima, T., & Skařzauskienė, A. (2010). Systems thinking as a platform for leadership performance in a complex world. Baltimore J. Management, 5 (3), 330–355.

Palmer, S., & Hall, W. (2011). An evaluation of a project-based learning initiative in engineering education. European Journal of Engineering Education, 36 (4), 357–365.

Pavlov, O. V., Doyle, J. K., Saeed, K., Lyneis, J. M., & Radzicki, M. J. (2014). The design of educational programs in system dynamics at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI). Systems, 2 (1), 54–76.

Pedersen, S., & Liu, M. (2003). Teachers’ beliefs about issues in the implementation of a student-centered learning environment. Educational Technology Research and Development, 51 (2), 57–76.

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93 (3), 223–232.

Richardson, G. P., Black, L. J., Deegan, M., Ghaffarzadegan, N., Greer, D., Kim, H., Luna-Reyes, L. F., MacDonald, R., Rich, E., Stave, K. A., Zimmermann, N., & Andersen, D. F. (2015). Reflections on peer mentoring for ongoing professional development in system dynamics. System Dynamics Review, 31 (3), 173–181.

Richardson, G. P., & Pugh, A. L. (1981). Introduction to system dynamics modeling with DYNAMO . MIT Press.

Richmond, B. (1991). Systems Thinking: Four Key Questions . Watkins, GA: High Performance Systems, Inc.

Richmond, B. (1994). System dynamics/systems thinking: Let’s just get on with it. System Dynamics Review, 10 (2–3), 135–157.

Richmond, B. (2000). The “Thinking” in systems thinking: Seven essential skills . Pegasus Communications.

Rooney-Varga, J. N., Kapmeier, F., Sterman, J. D., Jones, A. P., Putko, M., & Rath, K. (2020). The climate action simulation. Simulation & Gaming, 51 (2), 114–140.

Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organisation . Broadway Books.

Starobin, S. S., Chen, Y., Kollasch, A., Baul, T., & Laanan, F. S. (2014). The effects of a pre-engineering project-based learning curriculum on self-efficacy among community college students. Community Colleges J, 38 (2−3), 131–143.

Sterman, J. D. (2000). Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World . McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results . Chelsea Green Publishing.

Suprun, E., Horvat, A., & Andersen, D. F. (2021). Making each other smarter: Assessing peer mentoring groups as a way to support learning system dynamics. System Dynamics Review, 37 , 212–226.

Ventana Systems Inc. (1990). Vensim® Version 9.2.0 . https://vensim.com/vensim-personal-learning-edition/

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice . JosseyBass.

Wheat, I. D. (2007). The feedback method. A system dynamics approach to teaching macroeconomics . (Doctoral thesis). University of Bergen.

Wheat, I. D. (2008). The feedback method of teaching macroeconomics: Is it effective? System Dynamics. Review, 23 (4), 391–413.

Wilkerson, B., Aguiar, A., Gkini, C., Czermainski de Oliveira, I., Lunde Trellevik, L.-K., & Kopainsky, B. (2020). Reflections on adapting group model building scripts into online workshops. System Dynamics Review, 36 , 358–372.

Wright, G. B. (2011). Student-centered learning in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23 (3), 92–97.

Yoon, S. A., Goh, S. E., & Park, M. (2017). Teaching and learning about complex systems in K–12 science education: A review of empirical 1995-2015. Review of Educational Research, 88 (2), 285–325.

Zhang, K., Peng, S. W., & Hung, J. (2009). Online collaborative learning in a project-based learning environment in Taiwan: A case study on undergraduate students’ perspectives. Educational Media International, 46 (2), 123–135.

Zimmermann, N., Pluchinotta, I., Salvia, G., Touchie, M., Stopps, H., Hamilton, I., Kesik, T., Dianati, K., & Chen, T. (2021). Moving online: Reflections from conducting system dynamics workshops in virtual settings. System Dynamics Review, 37 , 59–71.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Residential College 4, National University of Singapore, University Town, Singapore

Sreenivasulu Bellam

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sreenivasulu Bellam .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center of English Language Communication and College of Peter & Alice Tan, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Misty So-Sum Wai-Cook

Center for Excellence in Education, Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR, USA

Amany Saleh

Advanced Studies, Leadership and Policy, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Krishna Bista

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Bellam, S. (2023). Project-Based Approach to Enhance Online Learning: A Case of Teaching Systems Thinking and System Dynamics Modeling. In: So-Sum Wai-Cook, M., Saleh, A., Bista, K. (eds) Online Teaching and Learning in Asian Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38129-4_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38129-4_5

Published : 23 September 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-38128-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-38129-4

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The influence of online education on pre-service teachers’ academic experiences at a higher education institution in the united arab emirates.

- College of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Al Ain University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Online education has gained widespread adoption in recent years due to several factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, which has accelerated the growth of online education, with universities transitioning to online platforms to continue their activities. However, this transition has also impacted the preparation of pre-service teachers, who receive training to become licensed or certified teachers. This study investigates the influence of online education on the academic experiences of 130 pre-service teachers attending the Postgraduate Diploma Program at Al Ain University in the UAE. It also explores the relationships between pre-service teachers’ demographics and five academic experiences. A quantitative questionnaire consisting of five newly-developed scales was used for data collection. Pre-service teachers’ demographics were found not to impact effective teaching and learning, skill development, or satisfaction. Age and employment status were found not to influence pre-service teachers’ views of faculty online assessment and feedback or course organization and management. However, online course organization and management and faculty online assessment and feedback were significantly correlated with marital status as engagement and motivation with employment status was, but not with age or marital status. Effective teaching and learning, faculty assessment, and feedback positively impacted pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation, while effective teaching and learning and course organization correlated with pre-service teachers’ skill development and satisfaction. Research on online education and pre-service teachers’ experiences post-pandemic is limited. Thus, future studies should explore this relationship to understand better pre-service teachers’ online learning experiences, involvement, and success.

Introduction

The widespread adoption of online education is variously attributed to technological advances, revolutionized delivery of educational content, and the flexibility and convenience of anytime, anywhere access. Enrolment in online education grew steadily for a decade in the United States, reaching 6.3 million students in 2016 ( Jiang et al., 2019 ). However, many students and faculty members had little or no online teaching/learning experience until the COVID-19 pandemic ( Rajab et al., 2020 ), when growth accelerated as campuses closed and higher education (HE) institutions rapidly transitioned to online teaching platforms ( Liguori and Winkler, 2020 ).

The pandemic also impacted the training and instruction of pre-service teachers on programs delivering the knowledge, skills, and experience needed to teach effectively. While the transition to online education has brought opportunities for pre-service teachers, impediments to its effectiveness include technical difficulties, unfamiliarity with online tools, and limited access to reliable devices and internet connections ( Salifu and Owusu-Boateng, 2022 ), underscoring the need for effective online teaching strategies and support for students and educators ( Okyere et al., 2022 ). For example, online education requires pre-service teachers to develop digital literacy and technological skills, such as proficiently navigating online platforms and adapting to video conferencing tools and learning management systems ( Aristeidou and Herodotou, 2020 ). During the pandemic, Lee et al. (2022) report that pre-service teachers became more familiar with online technologies, enhancing their digital competencies to effectively transform course materials to online versions, deliver instruction, provide academic support to future students in virtual classrooms, and resolve technical issues. Thus, pre-service teachers’ technological integration and competence will likely continue to expand and be an asset for their future teaching practices ( Özüdoğru and Cakir, 2020 ).

Pre-service teachers worldwide face several hurdles during the shift to online education, such as problems related to internet connectivity, student engagement, and pedagogical abilities ( Bunyamin, 2021 ; Gustine, 2021 ). However, additional issues become relevant while considering the particular circumstances of pre-service teachers in the UAE. A study by Mohebi et al. (2022) suggests that the socioeconomic and cultural disparities in UAE classrooms can present distinct difficulties during online practicum, in contrast to Western environments. Moreover, Emirati pre-service teachers may encounter particular difficulties associated with the presence of diverse students in inclusive classrooms ( Saqr and Tennant, 2016 ).

Although research has shown that online teacher training programs effectively prepare pre-service teachers for inclusive teaching, it is important to note that the findings may not be widely applicable due to the small number of participants and the specific settings, such as private universities in the UAE. This highlights the necessity for doing more extensive research that considers a wider variety of institutions and participants to fill the research gap and comprehend the difficulties and possibilities encountered by pre-service teachers in the UAE. Examining the shift to online education for pre-service teachers in the UAE is important because it enables the customization of teacher education programs to suit the unique requirements of this setting. To better equip future educators for success in the UAE educational system, teacher education programs should focus on recognizing and tackling the distinct problems pre-service teachers encounter.

Higher education in the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) government has invested heavily in becoming a global HE hub, attracting foreign students through international branch campuses and programs ( Karabchuk et al., 2021 ). The COVID-19 pandemic impacted HE in the UAE as institutions adapted to online learning ( Mukasa et al., 2021 ), compelling HE institutions in the UAE to switch to online learning to protect students’ safety while continuing the broader transition to entirely online learning ( Al Dulaimi et al., 2022 ). This impacted the academic experience of learners and teachers and the provision of educational continuity and quality ( Omar et al., 2021 ). For example, the UAE Ministry of Education implemented a virtual learning initiative delivering financial aid, resources, and support for teachers and students to access remote learning tools and technologies such as tablets and laptops ( Shah, 2023 ). It is significant that while COVID-19 accelerated the acceptance of online learning, it was not uncommon pre-COVID, when training programs and colleges began shifting toward more online, self-directed learning ( Silkens et al., 2023 ).

Reforms to HE in the UAE, primarily in reaction to the pandemic, have also impacted the education of pre-service teachers. For example, in order to ensure that they receive essential practical training and assistance, it has been necessary to amend the methodologies and approaches of their training programs. The abrupt move to online/ hybrid learning has significantly impacted the pre-service teacher observation and training components, according to Quirke and Saeed AlShamsi (2023) , who explored a “phygital” community of interest, combining physical and digital components to enable pre-service teachers to provide reflective peer observation of teaching in online learning contexts within the UAE. This involved observing colleagues’ teaching to provide constructive feedback, ensuring that pre-service teachers continue to receive beneficial practical instruction and assistance.

The postgraduate Professional Diploma in Teaching Program

Al Ain University in the UAE offers a Professional Diploma in Teaching Program (PDTP) for holders of bachelor’s degrees in relevant disciplines. Its curriculum of theoretical coursework and practical teaching experience covers a range of teaching-related topics, including educational psychology, assessment and evaluation, classroom management, curriculum development, and educational technology, emphasizing the development of the teaching skills these pre-service teachers will need. They are exposed to many pedagogical approaches and techniques and are urged to use what they learn in actual classroom situations. The PDTP strongly emphasizes how technology can be used effectively to enhance teaching and learning, offering pre-service teachers the knowledge and skills to design stimulating and dynamic learning environments. Its graduates should have the knowledge, competencies, and skills necessary to succeed in education and contribute to the growth of the sector in the UAE by working as teachers in a range of public and private educational settings. During the pandemic, Al Ain University had to shift the PDTP entirely online to ensure continuity of education for pre-service teachers, using platforms such as Moodle, Teams, and Google Classroom to deliver remote learning.

Literature review

This section reviews literature on the challenges and advantages of online learning for pre-service teachers; the quality of online teaching; engagement, motivation, skill development, and satisfaction in online education; and online education and pre-service teachers’ characteristics.

Challenges of online learning for pre-service teachers

The significant challenges for pre-service teachers of switching to online learning and adjusting to new platforms and technologies include poor internet connections, lack of enthusiasm, and increased stress ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). They may have been affected socially and emotionally by the lack of face-to-face connection and physical classroom presence ( Dergham et al., 2023 ). Some may also have been poorly prepared for online learning. In Kosovo, Nikoçeviq-Kurti (2023) found pre-service teachers had lower readiness in computer/internet self-efficacy, communication self-efficacy, and learning control.

Moreover, personal traits and individual variances can impact the effectiveness of online education. Kaspar et al. (2023) found that personality factors, educational attainment, and gender all significantly affected the online learning outcomes of university students during the pandemic, while anxiety was found to moderate pre-service teachers’ inclination to use digital technologies. Thus, individual circumstances may influence the success of online education. Other challenges were related to the quality of online teaching and overall learning outcomes and satisfaction with online education. A qualitative study by Nikoçeviq-Kurti (2023) found that pre-service teachers encountered challenges including technological skills, unrealistic assessments, and students being overloaded with assignments not counted in final assessments. Some participants reported that the practical portion of online classes was entirely absent, despite its importance for them, while some educators lacked motivation when teaching online. Martin et al. (2019) discovered that faculty new to online education felt unprepared and required pedagogical and technological support, emphasizing the importance of pinpointing the skills needed to train faculty for online instruction.

Advantages of online learning for pre-service teachers

Despite such difficulties, educators benefit from the flexibility of online learning, enabling them to reconcile their personal and academic obligations ( Lemay et al., 2021 ). Online education is recognized for its effectiveness, practicality, and adaptability, allowing students to work at their own pace and in the setting of their choice, control their learning schedules, and access course materials ( Zapata-Cuervo et al., 2021 ). Lemay et al. (2021) assert that pre-service teachers have benefited significantly from this flexibility because they frequently have other obligations, such as part-time work or family responsibilities, which online learning can help them to manage efficiently. Moreover, by fostering ownership and motivation, the flexibility and autonomy of online courses has helped pre-service teachers to engage in effective self-directed learning ( Uyen et al., 2023 ).

Crucially, online education has allowed future teachers to advance their technological expertise ( Ogbonnaya et al., 2020 ). Using learning technologies and online platforms enhances active learning, facilitates collaboration, discussion, and communication between pre-service teachers, their classmates, and educators, and allows them to exchange resources and feedback, thus improving the quality of education ( Irfan and Asif Raheem, 2023 ).

Quality of online teaching

Phillips (2021) notes that the transition from face-to-face to online pedagogies presents challenges and opportunities for postgraduate students who are themselves teachers. Therefore, HE institutions must ensure robust and flexible pedagogical practices to deliver quality teaching and learning. Effective online teaching of pre-service teachers requires faculty to have a comprehensive understanding of pedagogical principles and the ability to create interactive and engaging learning experiences. Among insights into the best strategies and practices for effective teaching in online education, Byrka et al. (2022) list 12 principles for effective online teaching in postgraduate education, covering course design, lecture readiness, assessment and feedback, and student engagement. Educators must also acquire appropriate technological skills for effective online teaching and learning ( Biedermann and Ahern, 2023 ). According to Ramaila and Mavuru (2022) , online education gives pre-service teachers sustainable development opportunities to boost their capacity to implement online teaching and learning. Effective teaching of pre-service teachers also requires the ability to create engaging and interactive learning experiences. Engagement entails enthusiastic participation and immediacy of communication, using applications and platforms such as online forums to facilitate dialog and interaction ( Mendelowitz et al., 2022 ) and reduce anxiety, essential to enhance postgraduate students’ learning experience ( Kumar and Verma, 2021 ).

Moreover, effective teaching and learning in postgraduate diploma programs, particularly online, requires careful planning, clear alignment of objectives, and innovative pedagogical approaches, to help pre-service teachers understand what is expected of them while enhancing their learning experience, which varied during the pandemic. Rafiq et al. (2022) found that pre-service teachers of English as a foreign language varied in readiness for online learning and in technological/pedagogical content knowledge. A study of pre-service English teachers in Hong Kong found that online education provided limited opportunities for immediate and extensive feedback ( Atmaca, 2023 ). Yildirim (2022) explored 72 pre-service teachers’ perceptions of online education during the pandemic, finding that 80% considered face-to-face classes more productive. Participants identified contributory factors including internet connection problems, digital literacy, readiness for online learning, lack of communication and interaction, lack of motivation and self-regulation, and feedback mechanisms.

Among research into the effects of the epidemic on online instruction, Khoiriyah et al. (2022) found that collaborative lesson planning improved pre-service teachers’ motivation and self-efficacy and shaped their professional identities, illustrating the importance of considering their specific knowledge and skills and the required professional development.

Assessment and feedback are important in guaranteeing the quality of teacher education programs, particularly online. COVID-related changes to online teaching/ learning have introduced obstacles and opportunities for faculty to assess and deliver feedback to pre-service teachers. In India, Joshi et al. (2020) examined the impact of the pandemic on instructors’ attitudes toward online teaching and assessment, identifying challenges including lack of technical support and awareness of online teaching platforms, security concerns, and personal issues such as technical incompetence, negativity, and weak enthusiasm. Having examined faculty readiness for online crisis teaching during the pandemic, Cutri et al. (2020) concluded that they must have adequate training and resources to transition effectively.

Engagement, motivation, skill development, and satisfaction in online education

Numerous research studies have found the engagement and motivation of pre-service teachers to be significantly impacted by online education. Uyen et al. (2023) found that the incorporation of online project-based learning into teacher education during the pandemic positively affected how pre-service teachers developed their knowledge, professional abilities, and learning attitudes. However, it also presented difficulties for educators, such as the need for teachers and students to possess the necessary knowledge and abilities and access to facilities and technology.

Motivation and engagement are influenced by attitudes and preparedness. Düzgün and Kaşkaya (2023) report that pre-service teachers’ views of online instruction were more positive in certain programs, such as social studies and early childhood education, than in others, while Chibisa et al. (2022) found that pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the usage of online learning influenced their readiness to adopt it, concluding that for online learning to be implemented successfully, pre-service teachers’ attitudes must change. According to Atmaca (2023) , the effectiveness of online education could be improved by raising the caliber of online learning platforms and the instruction given to pre-service teachers and their educators. Malabanan et al. (2022) established that pre-service teachers had the pedagogical skills necessary for the 21 st century and were prepared for online learning. Similarly, Uyar (2023) concluded that pre-service teachers had 21 st -century skills at high level.

Online education and pre-service teachers’ characteristics

Several studies have investigated the effects of demographic factors including age, employment status, gender, and marital status on pre-service teachers’ academic performance, knowledge, and skills. While no research has been identified as specifically addressing these in the context of the UAE, there are pertinent studies of how demographic factors affect teaching methods and online academic experiences in general.

One such factor is age. Yang et al. (2022) found that younger people frequently possess greater technological knowledge and expertise, which can enhance their online learning opportunities. They emphasize that other characteristics, such as digital competency and access to technology, may nonetheless have more impact on online academic experiences.

Another demographic factor, albeit rarely examined, that may affect online academic experience is marital status, whose influence may extend to educational ambitions. Married people, for instance, may have obligations and responsibilities that limit their capacity to engage in online learning ( Chen et al., 2021 ).

As to employment status, working people may struggle to balance their academic goals with their professional obligations, especially in an online learning setting, and they may have different reasons for wanting to pursue an online degree and different objectives, which can affect how engaged and satisfied they are with the learning process ( She et al., 2021 ).

Gender has also been found to affect teachers’ attitudes toward online learning and digital competencies ( Yang et al., 2022 ). Yalley et al. (2022) found that pre-service teachers’ demographic characteristics, including program of study, gender, and major and minor areas of expertise, were important predictors of technological competence.

In conclusion, there has been limited research into relationships of pre-service teachers’ demographic traits (age, marital status, work status, and gender) with their online academic experiences in the UAE, although existing literature on factors affecting such experiences may shed light on the possible impact of demographic traits. Therefore, further detailed research is required to investigate this association in the particular context of pre-service teachers in the UAE.

Theoretical framework

The Community of Inquiry paradigm developed by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer ( Duncan and Barnett, 2009 ) offers a suitable theoretical foundation for a study on online education for pre-service teachers. This framework prioritizes the educational experience of persons in online environments, with a specific emphasis on the significance of cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. Using this framework, researchers can examine how pre-service teachers participate in online learning, create educational material, and manage the intricacies of teaching in virtual settings. Within the scope of a research project examining online education for pre-service teachers in the UAE, the Community of Inquiry framework would be crucial for comprehending the manner in which these teachers engage with online platforms, cooperate with peers and instructors, and enable significant learning opportunities for students. This theory would offer a systematic methodology for analyzing the difficulties and possibilities encountered by pre-service teachers as they shift to online teaching methods.

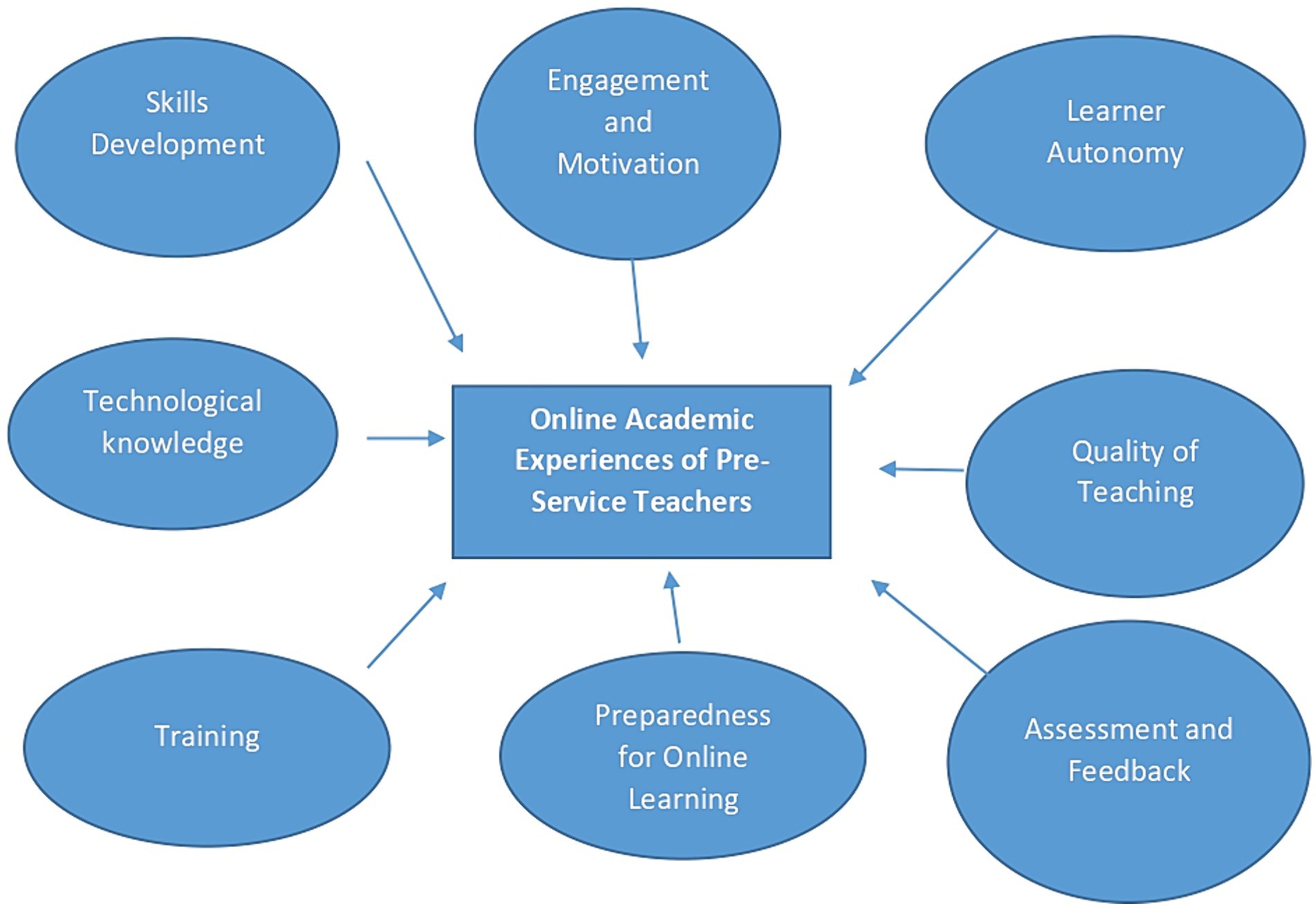

Using the Community of Inquiry framework can help to examine the particular factors of online education that affect pre-service teachers in the UAE, including digital literacy, technological expertise, and the capacity to develop captivating online learning environments. By employing this theoretical framework ( Figure 1 ), a thorough examination may be conducted to investigate how pre-service teachers in the institution under study adjust to online teaching methods and acquire the essential skills needed to succeed in virtual educational environments.

Figure 1 . Theoretical framework.

The literature review above indicates that positive online academic experiences for pre-service teachers require adaptation to new online platforms and technologies ( Zheng et al., 2021 ). Personal traits and individual variances impact the effectiveness and quality of pre-service teachers’ online education ( Kaspar et al., 2023 ), which also require faculty to have a comprehensive understanding of pedagogical principles and the ability to create interactive and engaging learning experiences ( Byrka et al., 2022 ). Understanding faculty’s readiness and providing them with the required training and resources, along with effective assessment and feedback, are crucial for the transition to high-quality online teacher education programs ( Cutri et al., 2020 ; Joshi et al., 2020 ). Online education significantly involves pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation ( Uyen et al., 2023 ). Finally, factors including age, employment status, gender, and marital status can affect online academic experiences ( Chen et al., 2021 ; She et al., 2021 ; Yang et al., 2022 ).

Study rationale

Rapid advances in educational technology have promoted online learning, significantly impacting pre-service teachers’ academic experiences. This quantitative study investigated the effects of online education on pre-service teachers’ academic experiences at Al Ain University, paying particular attention to the quality of teaching and learning, engagement and motivation, assessment and feedback, organization and management, and skill development and satisfaction. We believe that investigating pre-service teachers’ online learning experiences is critical to understanding how the change from face-to-face to online learning can affect the experiences of prospective teachers. This study is significant because pre-service teachers often rely on applying theoretical knowledge in real classroom contexts to develop their classroom management techniques and pedagogical skills, so the shift to online education may have challenged them by limiting their practical teaching experience and in-person classroom observations. Given the paucity of UAE-specific research into demographic influences noted above, we also believe that insights regarding pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the pedagogical approaches employed by faculty members in online education will be valuable in designing and implementing future online teacher education programs in the UAE. Therefore, we anticipate that the findings of this study can guide the development of effective training programs, inform policy development and practice and suggest tactics to improve pre-service teachers’ online learning experiences.

Research questions

The study sought to answer the following questions:

1. Is there any relationship between pre-service teachers’ demographic characteristics (age, marital status, and employment status) and their academic experiences, which include: quality of teaching and learning; engagement and motivation; assessment and feedback; organization and management; and skill development and satisfaction?

2. Do perceptions of effective teaching and learning (ETL) and faculty assessment and feedback (FAF) predict pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation (PTEM)?

3. Do ETL and course organization and management (COM) predict pre-service teachers’ skill development and satisfaction (PTSDS)?

In this study we utilized a descriptive survey design with quantitative technique to investigate the impact of online education on the academic experiences of pre-service teachers. The research design was chosen to investigate the effects of online education on different aspects of pre-service teachers’ academic experiences, including the quality of teaching and learning, engagement, motivation, assessment and feedback, organization and management, and skill development and satisfaction. The study sought to investigate potential correlations between demographic variables such as age, gender, marital status, and work status of pre-service teachers and their academic experiences.

The choice of a descriptive survey design is consistent with the nature of the research questions presented in the study. Descriptive survey methods are particularly suitable for creating a comprehensive overview of important concepts within a specific environment. This makes them an excellent choice for examining the impact of online education on the academic experiences of pre-service teachers ( Güler, 2022 ). This design facilitates gathering data that may be subjected to quantitative analysis to get insights into the connections between various variables, such as demographic features and academic experiences among pre-service teachers ( Obispo et al., 2023 ), yielding valuable insights for educational practitioners and policymakers.

In addition, applying a quantitative technique in the descriptive survey design allows to systematically collect numerical data on the many scales created to assess the various aspects of pre-service teachers’ academic experiences. This methodology simplifies the examination of the data to detect patterns, trends, and possible correlations among the variables being studied ( Asanga et al., 2023 ).

A descriptive survey methodology was developed, using Microsoft Forms to collect quantitative data on demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, and employment status) and on five scales developed by the researchers to measure quality of teaching and learning, engagement and motivation, assessment and feedback, organization and management, and skill development and satisfaction. These had five response options, from Strongly Disagree = 1 to Strongly Agree = 5.

The target population comprised all 450 pre-service teachers enrolled in the Professional Diploma in Teaching Program during the Spring semester of the 2021–2022 academic year, who were sent a link to the survey through their university Microsoft Teams accounts. An accompanying document stated the study’s purpose, assured respondents of confidentiality, and gave detailed instructions on accessing and completing the survey. Recipients were given 2 weeks to respond, during which polite reminders helped to increase response rates. Responses were received from 130 teachers, constituting 34.6 percent of those invited and exceeding the recommended minimum sample size of 10% of the population for descriptive quantitative research ( Purbasari et al., 2023 ).

Data analysis

The following statistical procedures were employed to analyze the data using IBM SPSS Statistics 26:

1. Descriptive statistics, which involved calculating the means and standard deviations of participants’ scores on each scale.

2. The independent-samples t -test investigated the effects of participants’ marital and employment status on their academic experiences: quality of teaching and learning; engagement and motivation; assessment and feedback; organization and management; skill development and satisfaction.

3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to quantify the effects of age on the same dependent variables.

4. Regression analysis was used to investigate the association of engagement and motivation with effective teaching and learning and with faculty assessment and feedback and that of course organization and management with skill development and satisfaction.

Gender was excluded from the analysis because only 1.5% of respondents were male.

In order to examine the influence of online education on the academic experiences of pre-service teachers, data gathering involved the use of five created scales. These scales evaluate several elements, including the effectiveness of teaching and learning, the level of engagement and motivation, the quality of evaluation and feedback, the efficiency of organization and management, and the extent of skill development and satisfaction.

The creation of these scales followed a strict methodology to guarantee their accuracy and consistency in measuring the essential aspects of teaching and learning quality, student engagement and motivation, assessment and feedback, organization and management, and skill development and satisfaction in online education. Therefore, creating these scales involved the participation of some experts, testing with a sample of pre-service teachers, analysis of individual items, running factor analysis to verify the validity of the measures, and testing for internal consistency to determine reliability. Accordingly, the scales were improved through expert and participant feedback to ensure they precisely represented the intended concepts and were appropriate for assessing the academic experiences of pre-service teachers in online education. The following are descriptions of all scales:

Effective teaching and learning scale

The ETL scale was developed to assess the efficacy of instructional techniques, curriculum materials, and educational achievements in the context of online learning. This scale consisted of instructional design items, information delivery lucidity, and learning activities’ applicability ( Liang, 2023 ). The ETL scale, developed initially, comprised 13 items, reduced to 10 and again to eight, following successive reviews by the researchers and by experts in the field. Assessing the internal consistency of the scale on a sample of 60 pre-service teachers yielded a Cronbach’s alpha (α) value of 0.80.

Pre-service teachers engagement and motivation scale

The PTEM scale, developed to gather data on online engagement and motivation, originally had 10 items, reduced as above to eight, then to six. This scale included factors such as student motivation, active engagement, and the perceived worth of the learning process ( Vasyukova et al., 2022 ). Its internal consistency, assessed as for ETL, was α = 0.78.

Faculty assessment and feedback scale

The FAF scale, developed to gather data on online assessment and feedback by faculty. It encompassed items pertaining to the equity of evaluations, promptness of feedback, and transparency of evaluation methods ( Rossettini et al., 2021 ). The FAF scale started with seven items, was reduced to five, and then to four. This small number of items may explain the low internal consistency value of α = 0.58.

Course organization and management scale

The COM scale, developed to gather data on course organization and management, began with six items, reduced to five, and then to four as above. The COM scale encompassed items about the arrangement of the course, availability of resources, and the promptness of teachers and support staff in addressing concerns ( Atkinson et al., 2022 ). Again, internal consistency appeared low (α = 0.72), perhaps because there were so few items.

Pre-service teachers’ skill development and satisfaction scale

The PTSDS scale measured how participants developed various skills through engaging in online teaching and learning and their satisfaction with this approach. It aimed to assess the attainment of new skills, knowledge, and general contentment with the online learning process. The PTSDS scale consisted of items pertaining to the enhancement of skills, the perceived worth of the program, and the general contentment with the achieved learning results ( Alhusban et al., 2023 ). Its original nine items were reduced on review to eight, then to six. Table 1 shows that it had the highest internal consistency value of the five scales (α = 0.81).

Table 1 . The research scales and their reliability.

Participants

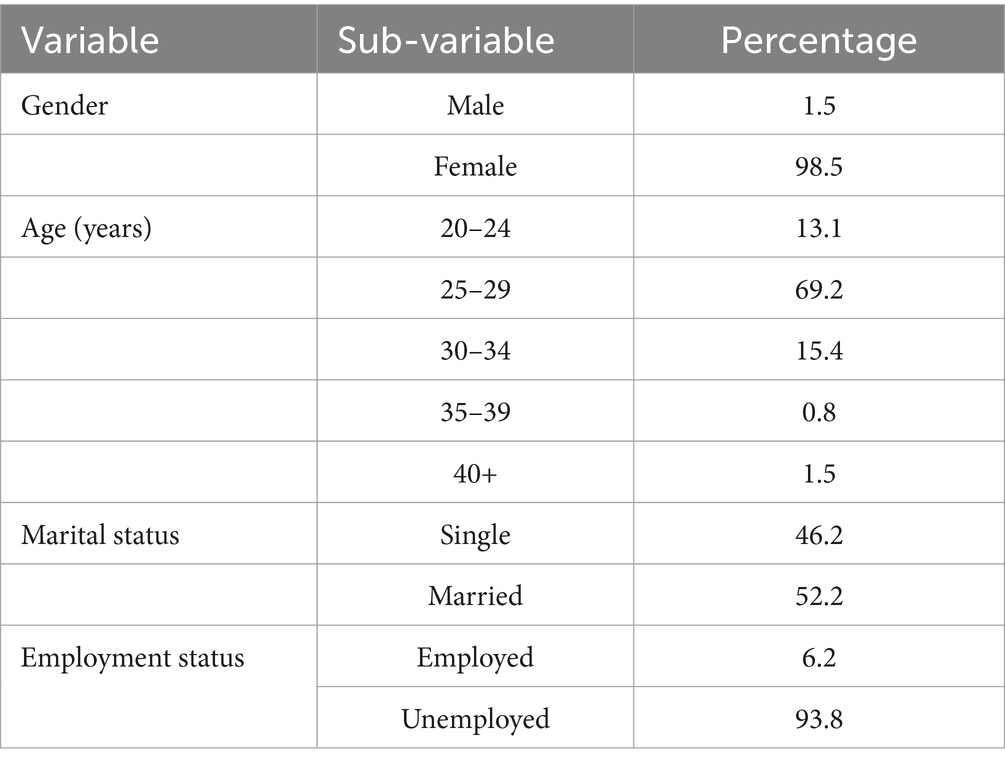

Table 2 lists demographic data on the 130 pre-service teachers who participated, showing that the great majority were female, so the two males were removed from the analysis. Ages ranged between 20 and 40+ years ( M = 2.08, SD = 0.671), more than two-thirds being between 25 and 29. As only three participants were over 34, they were also removed from the analysis. Slightly more respondents were married than single. Only two respondents were widowed, divorced, or separated, so again, these categories were removed from the analysis. The great majority of respondents were employed, with only eight being unemployed.

Table 2 . Demographic data.

Demographic characteristics and academic experiences (research question 1)

Perceptions of effective teaching and learning in relation to age, marital status, and employment status.

A one-way between-subjects ANOVA revealed a statistically insignificant relationship between ETL and participants’ age (20–24, 25–29, 30–34 years): F (2, 127) = 0.511, p = 0.601. The independent-samples t -test found no significant relationship of ETL with marital status, t (128) = −1.591, p = 0.114, nor with employment status, t (128) = 0.243, p = 0.808. Thus, pre-service teachers’ marital and employment status did not influence their online teaching and learning. In conclusion, age, marital status, and employment status did not impact participants’ effective teaching and learning.

Engagement and motivation in relation to age, marital status and employment

The independent-samples t -test and one-way between-subjects ANOVA revealed no significant association of PTEM with age, F (2, 127) = 1.04, p = 0.356, nor with marital status on PTEM, t (128) = −0.164, p = 0.104, but it was significantly related to employment status (employed: M = 23.13, SD = 6.01; unemployed: M = 25.66, SD = 2.95), t (128) = −2.17, p = 0.032. Taken together, these results suggest that teachers’ online engagement and motivation was more effective when they were unemployed.

Perceptions of faculty online assessment and feedback in relation to age, marital status and employment

A one-way between-subjects ANOVA found no significant impact of age on teachers’ views of faculty online assessment and feedback, F (2, 127) = 0.215, p = 0.807, but the independent-samples t -test revealed a significant relationship between these views and their marital status (single: M = 15.52, SD = 2.91; married: M = 16.56, SD = 2.17), t (128) = − 2.33, p = 0.021. Thus, pre-service teachers’ views of faculty online assessment and feedback appear more effective among married ones. However, the t -test found no significant relationship of teachers’ views on faculty online assessment and feedback with employment status, t (128) = −1.22, p = 0.225, meaning employment status did not impact participants’ views on faculty online assessment and feedback.

Perceptions of online course organization and management in relation to age, marital status, and employment

The one-way between-subjects ANOVA found no significant association between participants’ age and their views of online course organization and management, F (2, 127) = 0.459, p = 0.633; nor did the t- test find these views to be significantly related to employment status, t (128) = −0.120, p = 0.905. The only significant correlation of views on course organization and management was with marital status (single: M = 15.68, SD = 2.81; married: M = 16.69, SD = 1.83), t (128) = −2.44, p = 0.016. These results suggest that pre-service teachers’ views of online course organization and management were more effective when they were married.

Online skills development and satisfaction in relation to age, marital status, and employment

The same t -test and ANOVA procedures revealed no significant relationship of PTSDS with age, F (2, 127) = 0.811, p = 0.446, marital status, t (128) = −0.564, p = 0.574, or employment status, t (128) = −0.300, p = 0.764. This indicates that age, marital status, and employment status did not impact participants’ views on online skills development and satisfaction.

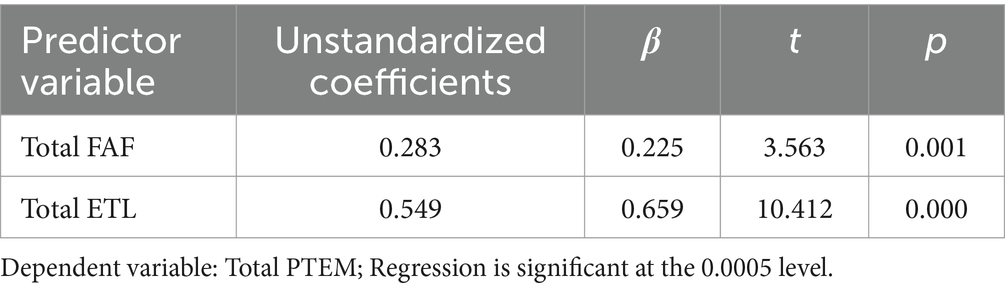

Engagement and motivation in relation to effective teaching and learning and to faculty assessment and feedback (research question 2)

A multiple regression was run to predict PTEM from ETL and FAF. These variables significantly predicted PTEM, F (2, 127) = 118.367, p < 0.0005, R 2 = 0.651. The two variables (ETL & FAF) added significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. This means that FAF had a significant effect on PTEM, t (127) =3.56, p < 0.05, as did ETL, t (127) =10.41, p < 0.05. It also means that with one-unit increase in FAF, the PTEM score increased by 0.280 and with one-unit increase in ETL, it increased by 0.550. Overall, the regression model is a good fit for the data. Therefore, the multiple regression analysis reveals that ETL and FAF as predictors were able to explain 65.1% of PTEM, meaning that as predictors, Effective Teaching and Learning and Faculty Assessment and Feedback explained pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation well ( Table 3 ). The regression equation is as follows:

Table 3 . Total PTEM by total FAF and total ETL.

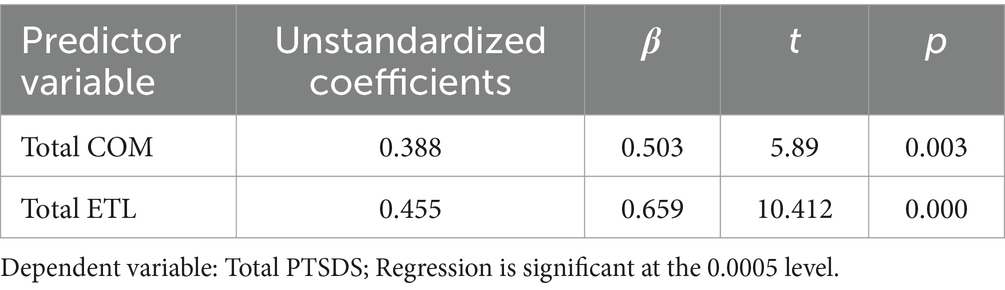

Effective teaching and learning, and course organization and management as predictors of skill development and satisfaction (research question 3)

A multiple linear regression was fitted to explain participants’ skill development and satisfaction in terms of course organization and management, and effective teaching and learning. COM and ETL as independent variables statistically significantly predicted PTSDS, F (2, 127) = 63.456, p < 0.0005 , R 2 = 0.500. These two variables (ETL and COM) added statistically significantly to the prediction, p < 0.05. This means that COM had a significant effect on PTSDS, t (127) =3.07, p < 0.05, while ETL also had a significant effect on PTSDS, t (127) =5.89, p < 0.05. Thus, the PTSDS score increased by 0.388 for every one-unit increase in COM and by 0.455 for each one-unit increase in ETL. Overall, the regression model is a good fit for the data. The multiple regression analysis reveals that ETL and COM as predictors were able to explain 50% of PTSDS, meaning that as predictors, Effective Teaching and Learning and Course Organization and Management explained pre-service teachers’ skill development and satisfaction well ( Table 4 ). The regression equation is as follows:

Table 4 . Total PTSDS by total COM and total ETL.

Summary and discussion

Various factors affect the online academic experiences of pre-service teachers. There follows a summary and discussion of the main results for each research question.

Research question 1

The results of the current study indicate that pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation in online education are more effective when they are unemployed. This finding of a positive relationship of engagement and motivation with employment status is consistent with some studies ( Ogbonnaya et al., 2020 ; Malabanan et al., 2022 ) but inconsistent with others. For example, Gussen et al. (2023) concluded that many pre-service teachers have negative attitudes toward research and lack the motivation to conduct it, while Ye et al. (2021) found that pre-service teachers demonstrated better motivation than beginners, except for a few factors like intrinsic value and teaching skills. These discrepancies imply that motivation levels may vary over a teacher’s tenure. Meanwhile, Calderón et al. (2019) and Plak et al. (2022) , for example, found no significant correlation between these variables.

The current finding that views of faculty online assessment and feedback were more effective in married pre-service teachers is consistent with Chibisa et al. (2022) and with Yıldırım and Tekel (2023) , who found that married pre-service teachers reported a positive impact of online assessment on their academic performance, crediting their stronger engagement in online education to the comfort of their home environment. Conversely, Nikoçeviq-Kurti (2023) found no significant effect of marital status on positive aspects of online teaching and quality of teaching activities. Other studies, such as Elshami et al. (2021) and Saribas and Çetinkaya (2021) , did not specifically seek correlations of assessment and feedback with marital status, but suggest that pre-service teachers’ analysis of feedback is extremely important whatever their marital status.

Current results also suggest that pre-service teachers’ views of online course organization and management were positively correlated with their marital status. While no studies address this relationship, some do address perceptions of the management and organization of online courses. Thus, Kulal and Nayak (2020) and Vakaliuk et al. (2022) emphasize the value of teachers’ development and technical proficiency. Conversely, Hulda (2022) and Tao and Gao (2022) emphasize teacher preparation programs and classroom management techniques, while Estaji and Zhaleh (2022) and Moore and Hong (2022) note that social presence, explicit training, and instructional design can help manage and structure online courses.

We found no literature consistent with our finding of no significant association of effective teaching and learning in online education with pre-service teachers’ age, marital status, or employment status. Nevertheless, some studies reveal factors influencing online teaching effectiveness generally, such as effective communication ( Liu et al., 2022 ), self-confidence and technology use ( Teoh et al., 2023 ), challenges ( Nikoçeviq-Kurti, 2023 ), and support ( Pourdavood and Song, 2021 ). Although demographic characteristics may not have a substantial impact on the efficiency of online teaching and learning for pre-service teachers in this study, research conducted in other locations on in-service teachers, such as in the Philippines ( Sacramento et al., 2021 ), indicates that the factors impacting the success of online education can fluctuate depending on the specific setting. Therefore, it is crucial to consider geographical differences and modify online education approaches to cater to the individual needs of various groups of learners.

Similarly, no existing research appears to focus on the relationship between pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation in online education and their age and marital status, which we found to be statistically insignificant. However, some studies support a positive relationship between motivation and engagement in online learning contexts ( Zapata-Cuervo et al., 2021 ; Malabanan et al., 2022 ).

Our finding of no significant relationship of pre-service teachers’ views of faculty online assessment and feedback with age and employment status is again not addressed in the literature, although some studies consider how online testing affects the emotional states of pre-service teachers ( Yıldırım and Tekel, 2023 ) and how pre-service teachers find online teaching effective but not for evaluation ( Saha et al., 2022 ).

Our results also suggest that age and work status do not significantly influence teachers’ perceptions of online course management. While the literature appears not to address this, Tao and Gao (2022) offer insights into online teaching and learning, highlighting the importance of efficient class management tactics and addressing anxiety and satisfaction factors.

We failed to find a significant effect of age, marital status, or employment status on pre-service teachers’ online skill development and satisfaction. Again, we identified no consistent prior findings, although other studies found online classroom management ( Taghizadeh and Amirkhani, 2022 ), 21st-century pedagogical competencies ( Malabanan et al., 2022 ), and interest in job choices ( Shen and Chee Luen, 2022 ) to be relevant factors in pre-service teachers’ online skill development. These findings suggest that demographic factors do not significantly impact online skill development.

Research question 2

The current results indicate that effective teaching and learning and faculty assessment and feedback predict pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation, consistent with Li et al. (2022) and Rojabi et al. (2022) . The latter identifies gamification as an online teaching strategy effective in boosting motivation and student involvement. Similarly, by increasing motivation through rewards and enhancing the quality of training, institutional support can increase faculty satisfaction with online instruction ( Basbeth et al., 2021 ). However, studies inconsistent with our finding imply that the accessibility and caliber of educational technology tools may impact the functioning of online courses ( Hayat et al., 2021 ). The degree to which new teachers believe they are competent at teaching online may vary, and students’ technical proficiency may partly determine their online performance ( Stewart and Baker, 2021 ). Further research into these factors would help to make online teaching and learning and faculty assessment and feedback more effective at fostering pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation.

Various studies show that pre-service teachers’ engagement and motivation can be predicted through faculty assessment and feedback, that realistic learning experiences and evaluation tools are crucial for effective online teaching ( Hayat et al., 2021 ), and that feedback on instructional strategies can increase motivation and engagement ( Bradley and Kramer-Gordon, 2023 ), as can effective online instruction and participation in online classrooms, making inexperienced teachers who receive support and training more motivated and at ease, boosting their interest in online education ( Tanguay and Many, 2022 ). Successful online teaching depends on the use of authentic learning experiences, assessment tools, and feedback systems to increase the involvement and motivation of pre-service teachers ( Byrka et al., 2022 ). Research conducted by Hunukumbure et al. (2021) has demonstrated that offering feedback on teaching tactics substantially enhances students’ motivation and engagement in the learning process. Additionally, faculty calibration and the utilization of instructional rubrics are acknowledged as efficacious approaches to strengthen the caliber of feedback and assessment in educational environments ( Gosselin and Golick, 2020 ). Moreover, studies have emphasized the significance of utilizing online feedback systems to foster transparent conversations between students and teachers, encouraging meaningful feedback exchanges ( Hidayah, 2020 ). Thus, the success of online teaching practices relies heavily on faculty attitudes toward motivational principles, the utilization of online feedback systems, and the incorporation of experiential learning.

Research question 3

Effective teaching and learning and course organization and management were found to be good predictors of pre-service teachers’ skill development and satisfaction, consistent with much existing research ( Atmaca, 2023 ). A vital predictor of self-assurance and effectiveness in online instruction is self-efficacy in instructing ( Naz et al., 2021 ). Using technology in online instruction positively impacts the development of pre-service teachers’ skills and satisfaction ( Şahin and Şahin, 2022 ; Teoh et al., 2023 ).