Center for Gun Violence Solutions

- Make a Gift

- Stay Up-To-Date

- Research & Reports

Firearm Violence in the United States

- National Survey of Gun Policy

- The Public Health Approach to Prevent Gun Violence

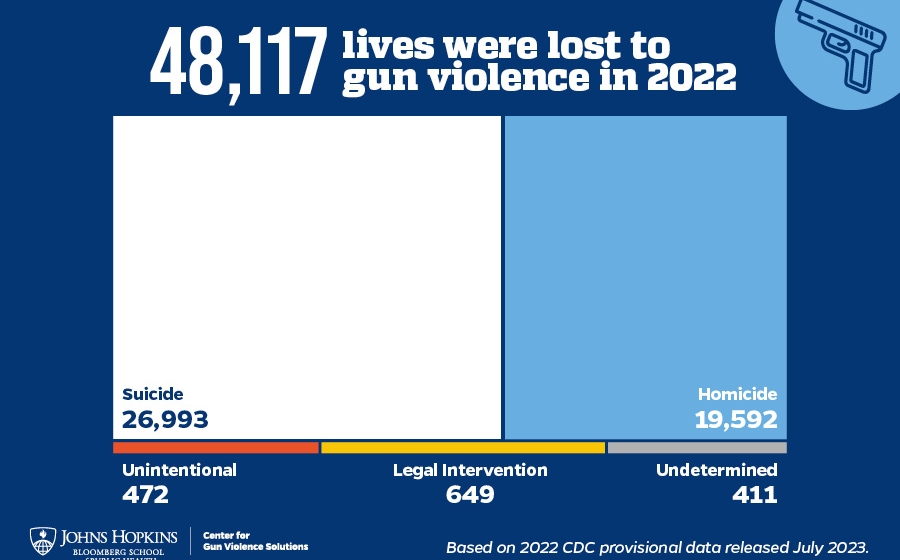

Firearm violence is a preventable public health tragedy affecting communities across the United States. In 2021 48,830 Americans died by firearms—an average of one death every 11 minutes. Over 26,328 Americans died by firearm suicide, 20,958 die by firearm homicide, 549 died by unintentional gun injury, and an estimated 1,000 Americans were fatally shot by law enforcment. 1,2 In addition, an average of more than 200 Americans visit the emergency department for nonfatal firearm injuries each day. 3

For each firearm death, many more people are shot and survive their injuries, are shot at but not physically injured, or witness firearm violence. Many experience firearm violence in other ways, by living in impacted communities with high levels of violence, losing loved ones to firearm violence, or being threatened with a firearm. Others are fearful to walk in their neighborhoods, attend events, or send their child to school. In short, firearm violence is public health epidemic that has lasting impacts on the health and well-being of everyone on this country.

Overwhelming evidence shows that firearm ownership and access is associated with increased suicide, homicide, unintentional firearm deaths, and injuries. These injuries and deaths are preventable, through evidence-based solutions.

Firearm Ownership

Firearms remain embedded in American history and modern culture. Americans own 46% of the world’s civilian-owned firearms and U.S. firearm ownership rates far exceed those of other high-income countries. 4,5 Forty-six percent of U.S. households report owning at least one firearm, including 30% of Americans who say they personally own a firearm. 6,7 Firearm ownership varies significantly by state. For example, an estimated 64% of households own a firearm in Montana compared to only 8% in New Jersey. 8

It has been well-documented that firearm ownership rates are associated with increased firearm-related death rates. Among high-income countries, the United States is an outlier in terms of firearm violence. The U.S. has the highest firearm ownership and highest firearm death rates of 27 high-income countries. 9

The firearm homicide rate in the U.S. is nearly 25 times higher than other high-income countries and the firearm suicide rate is nearly 10 times that of other high-income countries. 10

The Geography of Gun Violence

Gun death rates vary widely across the United States due to differences in socio-economic factors, demographics, and, importantly, gun policies. In general, the states with the highest gun death rates tend to be states in the South or Mountain West, with weaker gun laws and higher levels of gun ownership, while gun death rates are lower in the Northeast, where gun violence prevention laws are stronger.

* The total number of gun homicide deaths in New Hampshire and Vermont were less than 10 and thus repressed by CDC. Gun homicide deaths are thus listed as “other gun death rate” for these two states. Additionally, “other intents” include legal intervention, unintentional, and unclassified.

Firearm purchases increased during the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic firearm sales rose at unprecedented levels with an estimated one in five U.S. households purchasing a firearm from March 2020 to March 2022. 11 The FBI reported a record high of 20 million annual firearm sales in both 2020 and 2021, up from an average of 13 million firearms sold from 2010 to 2019. 12

Knowing the Facts About Firearm Ownership and Safety

Over four decades of public health research consistently finds that firearm ownership increases the risk of firearm homicide, suicide, and unintentional injury. Nevertheless, more than 6 in 10 Americans believe that a firearm in the home makes the family safer—a figure that has nearly doubled since 2000. 13 This increase in perceived safety is reflected in shifting reasons for firearm ownership. In a 2023 Pew Research survey, more than two-thirds (71%) of firearm owners cited protection as a major reason for ownership. 14 This represents a notable increase from the mid-1990s, when the majority of American firearm owners cited recreation as their primary reason for ownership and fewer than half owned firearms primarily for protection. 15

Research runs counter to these changing public perceptions of firearms providing safety. It shows that firearm ownership puts individuals and their families at higher risk of injury and death. Individuals who choose to own a firearm can mitigate many of the risks associated with ownership by always storing their firearms unloaded and locked in a secure place, and refraining from carrying their firearms in public places.

Firearm owners can make their homes safer through secure firearm storage practices. Unfortunately, the majority of U.S. firearm owners choose to leave their firearms unlocked, allowing children or persons, who are at risk for violence to self or others, to access them. 16 An estimated 4.6 million children live in households with at least one firearm that is loaded and unlocked. 17 These unsafe storage practices lead to countless suicides, homicides, and unintentional injuries by individuals who should not have access to a firearm. This includes children, prohibited persons with a history of violence, and family members who may be suicidal or temporarily in crisis.

Leaving firearms unsecured also fuels theft—a primary avenue in which firearms are diverted into the illegal market and used in crime. There are an estimated 250,000 firearm theft incidents each year resulting in about 380,000 firearms stolen annually. 18 In recent years, as more Americans carry firearms in public, theft from cars has skyrocketed. Firearms stolen from cars now make up the majority of thefts. In fact, one analysis of crime data reported to the FBI found that on average, at least one firearm is reported stolen from a car every 15 minutes. 19

Carrying firearms in public also increases the risk for violence by escalating minor arguments and increasing the chances that a confrontation will become lethal. Research has found that even the mere presence of a firearm increases aggressive thoughts and actions. 20

Some believe that carrying a firearm will act as a deterrent and help prevent conflicts or minimize harm. While there are specific examples where this was true, there are many more cases where firearm carrying escalates conflict and leads to firearm injury or death. In aggregate, research shows firearm carrying increases levels of violent crime. 21

It’s important for individuals to know the risks of firearm ownership, and the reality that higher levels of firearm ownership and carrying do not reduce violence or enhance public safety.

How does access to firearms affect deaths?

Higher levels of firearm ownership and permissive firearm laws are associated with higher rates of suicide, homicide, violent crime, unintentional firearm deaths, and shootings by police.

Suicide

More than 55% of all firearm deaths are suicides. 22 Evidence consistently shows that access to firearms increases the risk of suicide. 23,24 Access to a firearm in the home increases the odds of suicide more than three-fold. 25 Firearms are dangerous when someone is at risk for suicide because they are the most lethal suicide attempt method. Eighty-five percent of suicide attempts with a firearm are fatal compared to the most widely used suicide attempt methods, which have case fatality rates below 5%. 26

Research shows that individuals often do not substitute means for suicide if their preferred method is not available. In other words, when individuals who have planned a suicide by firearm cannot access a one, they often not do attempt suicide by another method. 27 Even if they substitute firearms with another method they increase their chances of survival because virtually every other method is less lethal than firearms. 28 Delaying a suicide attempt can also allow suicidal crises to pass and lead to fewer suicides. Ninety percent of individuals who attempt suicide and survive do not go on to die by suicide. 29 The use of a firearm in a suicide attempt often means there is no second chance. Reducing access to lethal means, such as firearms, is critical to saving lives.

Policies and practices that temporarily restrict access to someone at elevated risk for suicide can save lives. These interventions include Extreme Risk Protection Orders, safe and secure firearm storage practices, and lethal means safety counseling.

Homicide and violent crime

Over 40% of all firearm deaths are homicides. 30 Access to firearms—such as the presence of a firearm in the home—is correlated with an increased risk for homicide victimization. 31 Studies show that access to firearms in the household doubles the risk of homicide. 32 States with high rates of firearm ownership consistently have higher firearm homicide rates. 33 Firearms drive our nation’s high homicide rate, accounting for 8 out of every 10 homicides committed. 34

Lax public carry laws which allow individuals to carry firearms in public places with little oversight are linked to increases in firearm homicides and assaults. 35 Similarly, states with permissive firearm laws have higher rates of mass shootings. 36 Firearms also contribute to domestic violence with over half of all intimate partner homicides committed with firearms. 37 A women is five times more likely to be murdered when her abuser has access to a firearm. 38

Firearm homicide is a complex issue that includes different types of firearm violence—domestic violence, community violence, and mass shootings—and requires an array of policies. These policies include: firearm purchaser licensing laws which build upon universal background checks, firearm removal laws, safe and secure storage laws, community violence intervention programs, and strong public carry laws.

Unintentional Shootings

Each year more than 500 people are killed and thousands more are injured by unintentional shootings, also commonly referred to as accidental shootings. 39,40

Easy access to unsecured firearms increases the risk of unintentional injury and death by firearm. Children are often impacted by unintentional firearm injuries by gaining access to an unsecured firearm owned by a parent. In fact, every six days a child under the age of 10 is killed by an unintentional shooting. 41

Laws that promote safe and secure firearm storage practices can prevent unintentional shootings. For example, state Child Access Prevention laws, which hold gun owners accountable if a child accesses an unsecured firearm, are linked to reductions in unintentional shootings among children and teens and may also reduce unintentional shootings among adults. 42,43

Shootings by Police

Each year, more than 1,000 people are shot and killed by police officers, and thousands more are injured. 44,45 Black people are disproportionately impacted by this physical violence. Unarmed Black people are over three times more likely to be shot and killed by police compared to white people. 46

Permissive firearm laws are associated with increases in shootings by police. Specifically, research finds that state permitless concealed carry laws increase shootings by police by 13%. 47 Conversely, strong state firearm laws, like Firearm Purchaser Licensing laws, are linked to reductions in shootings by police. 48

Better data on police-involved injuries and deaths are sorely needed. Compulsory and comprehensive data collection at the local level, reporting to the federal government, and transparency in public dissemination of data will be critical for understanding this unique kind of firearm violence and developing evidence-based solutions to minimize police-involved shootings.

1. Davis A, Kim R, & Crifasi CK. (2023). A Year in Review: 2021 Gun Deaths in the U.S. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions . Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

2. Tate J, Jenkins J, & Rich S. (2021). Fatal Force. Washington Post .

3. Schnippel K, Burd-Sharps S, Miller T, Lawrence B, Swedler DL. (2021). Nonfatal firearm injuries by intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health .

4. Bangalore S & Messerli FH. (2013). Gun ownership and firearm-related deaths. American Journal of Medicine.

5. Karp A. (2018). Estimating global civilian-held firearms numbers. Small Arms Survey.

6. One in Five American Households Purchased a Gun During the Pandemic. (2022). NORC at the University of Chicago.

7. Schaeffer K. (2023). Key facts about Americans and guns. Pew Research Center.

8. Gun Ownership in America, 1980-2016. (2020). RAND Corporation.

9. Bangalore S & Messerli FH. (2013). Gun ownership and firearm-related deaths. American Journal of Medicine.

10. Grinshteyn E & Hemenway D. (2019). Violent death rates in the US compared to those of the other high-income countries, 2015. Preventive Medicine .

11. One in Five American Households Purchased a Gun During the Pandemic. (2022). NORC at the University of Chicago.

12. One in Five American Households Purchased a Gun During the Pandemic. (2022). NORC at the University of Chicago.

13. McCarthy J. (2014). More than six in 10 Americans say guns make homes safer. Gallup.

14. Doherty C, Kiley J, Oliphant B, Hartig H, Borelli G, Daniller A, Van Green T, Cerda A, Gracia S, and Lin K. (2023). For most U.S. gun owners, protection is the main reason they own a gun. Pew Research Center.

15. LaFrance A. (2016). The Americans who stockpile guns. The Atlantic .

16. Webster DW, Vernick JS, Zeoli AM, and Manganello JA. (2004). Association between youth-focused firearm laws and youth suicides. JAMA Network .

17. Miller M and Azrael D. (2022). Firearm storage in US households with children. JAMA Network .

18. Hemenway D, Azrael D, and Miller M. (2017). Whose guns are stolen? The epidemiology of gun theft victims. Injury Epidemiology.

19. O’Toole M, Szkola J, and Burd-Sharps S. (2022). Gun thefts from cars: the largest source of stolen guns. Everytown Research and Policy.

20. Benjamin Jr AJ, Kepes S, and Bushman BJ. (2018). Effects of weapons on aggressive thoughts, angry feelings, hostile appraisals, and aggressive behavior: A meta-analytic review of the weapons effect literature. Personality and Social Psychology Review.

21. Donohue JJ, Aneja A, & Weber KD. (2019). Right‐to‐carry laws and violent crime: A comprehensive assessment using panel data and a state‐level synthetic control analysis. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies.

22. Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death.

23. Anglemyer A, Horvath T, and Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

24. Siegel M and Rothman EF. (2016). Firearm ownership and suicide rates among US men and women, 1981–2013. American Journal of Public Health .

25. Anglemyer A, Horvath T, and Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

26. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2000). Lethality of suicide methods: Case fatality rates by suicide method, 8 U.S. states, 1989-1997.

27. Daigle MS. (2005). Suicide prevention through means restriction: Assessing the risk of substitution. A critical review and synthesis. Accident Analysis and Prevention .

28. Lethality of suicide methods . Means Matter. Harvard T.H.Chan School of Public Health.

29. Owens D, Horrocks J, & House A. (2002). Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry .

30. Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death.

31,32. Anglemyer A, Horvath T, and Rutherford G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

33. Siegel M, Ross CS, and King C. (2014). Examining the relationship between the prevalence of guns and homicide rates in the USA using a new and improved state-level gun ownership proxy. Injury Prevention .

34. Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death.

35. Doucette ML, McCourt AD, Crifasi CK, & Webster DW. (2023). Impact of changes to concealed-carry weapons laws on fatal and nonfatal violent crime, 1980–2019. American Journal of Epidemiology .

36. Reeping PM, Cerdá M, Kalesan B, Wiebe DJ, Galea S, and Branas CC. (2019). State gun laws, gun ownership, and mass shootings in the US: Cross sectional time series. British Medical Journal .

37. Zeoli AM, Malinski R, & Turchan B. (2016). Risks and targeted interventions: Firearms in intimate partner violence. Epidemiologic Reviews .

38. Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA, Gary F, Glass N, McFarlane J, Sachs C, Sharps P, Ulrich Y, Wilt SA, Manganello J, Xu X, Schollenberger J, Frye V, & Laughon K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health .

39. Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death.

40. Barber C, Cook PJ, Parker ST. (2022). The emerging infrastructure of US firearms injury data. Preventive medicine .

41. Three-year average, 2019-2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death.

42. Webster DW, Starnes M. (2000). Reexamining the association between child access prevention gun laws and unintentional shooting deaths of children. Pediatrics .

43. DeSimone J, Markowitz S, Xu J. (2013). Child access prevention laws and nonfatal gun injuries. Southern Economic Journal.

44. Kaufman EJ, Karp DN, and Delgado MK. (2017). US emergency department encounters for law enforcement-associated injury, 2006-2012. Jama Surgery .

45, 46. Tate J, Jenkins J, & Rich S. (2021). Fatal Force. Washington Post .

47. Doucette ML, Ward JA, McCourt AD, Webster D, Crifasi CK. (2022). Officer-involved shootings and concealed carry weapons permitting laws: analysis of gun violence archive data, 2014–2020. Journal of urban health.

48. Crifasi CK, Ward J, McCourt AD, Webster D, Doucette ML. (2023).The association between permit-to-purchase laws and shootings by police. Injury epidemiology.

Support Our Life Saving Work

MAKE A GIFT

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Case Discussions

- Special Symposiums

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with Public Health Ethics?

- About Public Health Ethics

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the burden of firearm violence, understanding and reducing firearm violence is complex and multi-factorial, interventions and recommendations, conclusions, research ethics.

- < Previous

Firearm Violence in the United States: An Issue of the Highest Moral Order

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Chisom N Iwundu, Mary E Homan, Ami R Moore, Pierce Randall, Sajeevika S Daundasekara, Daphne C Hernandez, Firearm Violence in the United States: An Issue of the Highest Moral Order, Public Health Ethics , Volume 15, Issue 3, November 2022, Pages 301–315, https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phac017

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Firearm violence in the United States produces over 36,000 deaths and 74,000 sustained firearm-related injuries yearly. The paper describes the burden of firearm violence with emphasis on the disproportionate burden on children, racial/ethnic minorities, women and the healthcare system. Second, this paper identifies factors that could mitigate the burden of firearm violence by applying a blend of key ethical theories to support population level interventions and recommendations that may restrict individual rights. Such recommendations can further support targeted research to inform and implement interventions, policies and laws related to firearm access and use, in order to significantly reduce the burden of firearm violence on individuals, health care systems, vulnerable populations and society-at-large. By incorporating a blended public health ethics to address firearm violence, we propose a balance between societal obligations and individual rights and privileges.

Firearm violence poses a pervasive public health burden in the United States. Firearm violence is the third leading cause of injury related deaths, and accounts for over 36,000 deaths and 74,000 firearm-related injuries each year ( Siegel et al. , 2013 ; Resnick et al. , 2017 ; Hargarten et al. , 2018 ). In the past decade, over 300,000 deaths have occurred from the use of firearms in the United States, surpassing rates reported in other industrialized nations ( Iroku-Malize and Grissom, 2019 ). For example, the United Kingdom with a population of 56 million reports about 50–60 deaths per year attributable to firearm violence, whereas the United States with a much larger population, reports more than 160 times as many firearm-related deaths ( Weller, 2018 ).

Given the pervasiveness of firearm violence, and subsequent long-term effects such as trauma, expensive treatment and other burdens to the community ( Lowe and Galea, 2017 ; Hammaker et al. , 2017 ; Jehan et al. , 2018 ), this paper seeks to examine how various evidence-based recommendations might be applied to curb firearm violence, and substantiate those recommendations using a blend of the three major ethics theories which include—rights based theories, consequentialism and common good. To be clear, ours is not a morally neutral paper wherein we weigh the merits of an ethical argument for or against a recommendation nor is it a meta-analysis of the pros and cons to each public health recommendation. We intend to promote evidence-based interventions that are ethically justifiable in the quest to ameliorate firearm violence.

It is estimated that private gun ownership in the United States is 30% and an additional 11% of Americans lived with someone who owed a gun in 2017 ( Gramlich and Schaeffer, 2019 ). Some of the reported motivations for carrying a firearm include protection against people (anticipating future victimization or past victimization experience) and hunting or sport shooting ( Schleimer et al. , 2019 ). A vast majority of firearm-related injuries and death occur from intentional harm (62% from suicides and 35% from homicides) versus 2% of firearm-related injuries and death occurring from unintentional harm or accidents (e.g. unsafe storage) ( Fowler et al. , 2015 ; Lewiecki and Miller, 2013 ; Monuteaux et al. , 2019 ; Swanson et al. , 2015 ).

Rural and urban differences have been noted regarding firearms and its related injuries and deaths. In one study, similar amount of firearm deaths were reported in urban and rural areas ( Herrin et al. , 2018 ). However, the difference was that firearm deaths from homicides were higher in urban areas, and deaths from suicide and unintentional deaths were higher in rural areas ( Herrin et al. , 2018 ). In another study, suicides accounted for about 70% of firearm deaths in both rural and urban areas ( Dresang, 2001 ). Hence, efforts to implement these recommendations have the potential to prevent most firearm deaths in both rural and urban areas.

The burden of firearm injuries on society consists of not only the human and economic costs, but also productivity loss, pain and suffering. Firearm-related injuries affect the health and welfare of all and lead to substantial burden to the healthcare industry and to individuals and families ( Corso et al. , 2006 ; Tasigiorgos et al. , 2015 ). Additionally, there are disparities in firearm injuries, whereby firearm injuries disproportionately affect young people, males and non-White Americans ( Peek-Asa et al. , 2017 ). The burden of firearm also affects the healthcare system, racial/ethnic minorities, women and children.

Burden on Healthcare System

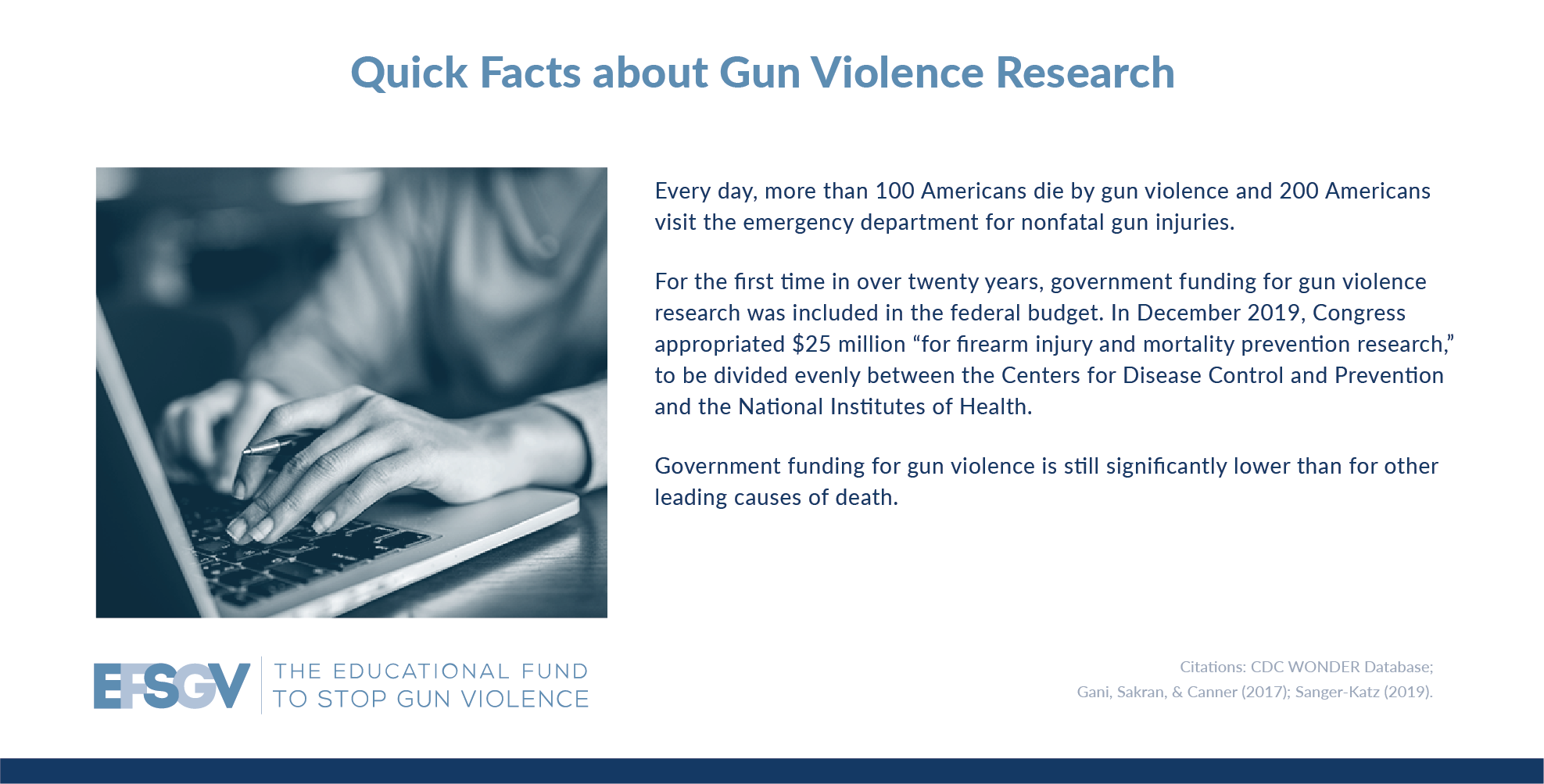

Firearm-related fatalities and injuries are a serious public health problem. On average more than 38 lives were lost every day to gun related violence in 2018 ( The Education Fund to Stop Gun Violence (EFSGV), 2020 ). A significant proportion of Americans suffer from firearm non-fatal injuries that require hospitalization and lead to physical disabilities, mental health challenges such as post-traumatic stress disorder, in addition to substantial healthcare costs ( Rattan et al. , 2018 ). Firearm violence and related injuries cost the U.S. economy about $70 billion annually, exerting a major effect on the health care system ( Tasigiorgos et al. , 2015 ).

Victims of firearm violence are also likely to need medical attention requiring high cost of care and insurance payouts which in turn raises the cost of care for everyone else, and unavoidably becomes a financial liability and source of stress on the society ( Hammaker et al. , 2017 ). Firearm injuries also exert taxing burden on the emergency departments, especially those in big cities. Patients with firearm injuries who came to the emergency departments tend to be overwhelmingly male and younger (20–24 years old) and were injured in an assault or unintentionally ( Gani et al. , 2017 ). Also, Carter et al. , 2015 found that high-risk youth (14–24 years old) who present in urban emergency departments have higher odds of having firearm-related injuries. In fact, estimates for firearm-related hospital admission costs are exorbitant. In 2012, hospital admissions for firearm injuries varied from a low average cost of $16,975 for an unintentional firearm injury to a high average cost of $32,237 for an injury from an assault weapon ( Peek-Asa et al. , 2017 ) compared with an average cost of $10,400 for a general hospital admission ( Moore et al. , 2014 ).

Burden on Racial/Ethnic Minorities, Women and Children

Though firearm violence affects all individuals, racial disparities exist in death and injury and certain groups bear a disproportionate burden of its effects. While 77% of firearm-related deaths among whites are suicides, 82% of firearm-related deaths among blacks are homicides ( Reeves and Holmes, 2015 ). Among black men aged 15–34, firearm-related death was the leading cause of death in 2012 ( Cerdá, 2016 ). The racial disparity in the leading cause of firearm-related homicide among 20- to 29-year-old adults is observed among blacks, followed by Hispanics, then whites. Also, victims of firearms tend to be from lower socioeconomic status ( Reeves and Holmes, 2015 ). Understanding behaviors that underlie violence among young adults is important. Equally important is the fiduciary duty of public health officials in creating public health interventions and policies that would effectively decrease the burden of gun violence among all Americans regardless of social, economic and racial/ethnic backgrounds.

Another population group that bears a significant burden of firearm violence are women. The violence occurs in domestic conflicts ( Sorenson and Vittes, 2003 ; Tjaden et al. , 2000 ). Studies have shown that intimate partner violence is associated with an increased risk of homicide, with firearms as the most commonly used weapon ( Leuenberger et al. , 2021 ; Gollub and Gardner, 2019 ). However, firearm threats among women who experience domestic violence has been understudied ( Sullivan and Weiss, 2017 ; Sorenson, 2017 ). It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of women who experience intimate partner violence and live in households with firearms have been held at gunpoint by intimate partners ( Sorenson and Wiebe, 2004 ). Firearms are used to threaten, coerce and intimidate women. Also, the presence of firearms in a home increases the risk of women being murdered ( Campbell et al. , 2015 ; Bailey et al. , 1997 ). Further, having a firearm in the home is strongly associated with more severe abuse among pregnant women in a study by McFarlane et al. (1998) . About half of female intimate partner homicides are committed with firearms ( Fowler, 2018 ; Díez et al. , 2017 ). Some researchers reported that availability of firearms in areas with fewer firearms restrictions has led to higher intimate partner homicides ( Gollub and Gardner, 2019 ; Díez et al. , 2017 ).

In the United States, children are nine times more likely to die from a firearm than in most other industrialized nations ( Krueger and Mehta, 2015 ). Children here include all individuals under age 18. These statistics highlight the magnitude of firearm injuries as well as firearms as a serious pediatric concern, hence, calls for appropriate interventions to address this issue. Unfortunately, children and adolescents have a substantial level of access to firearms in their homes which contributes to firearm violence and its related injuries ( Johnson et al. , 2004 ; Kim, 2018 ). About half of all U.S. households are believed to have a firearm, making firearms one of the most pervasive products consumed in the United States ( Violano et al. , 2018 ). Consequently, most of the firearms used by children and youth to inflict harm including suicides are obtained in the home ( Johnson et al. , 2008 ). Beyond physical harm, children experience increased stress, fear and anxiety from direct or indirect exposure to firearms and its related injuries. These effects have also been reported as predictors of post-traumatic stress disorders in children and could have long-term consequences that persist from childhood to adulthood ( Holly et al. , 2019 ). Additionally, the American Psychological Association’s study on violence in the media showed that witnessing violence leads to fear and mistrust of others, less sensitivity to pain experienced by others, and increases the tendency of committing violent acts ( Branas et al. , 2009 ; Calvert et al. , 2017 ).

As evidenced from the previous sections, firearm violence is a complex issue. Some argue that poor mental health, violent video games, substance abuse, poverty, a history of violence and access to firearms are some of the reasons for firearm violence ( Iroku-Malize and Grissom, 2019 ). However, the prevalence and incidence of firearm violence supersedes discrete issues and demonstrates a complex interplay among a variety of factors. Therefore, a broader public health analysis to better understand, address and reduce firearm violence is warranted. Some important factors as listed above should be taken into consideration to more fully understand firearm violence which can consequently facilitate processes for mitigation of the frequency and severity of firearm violence.

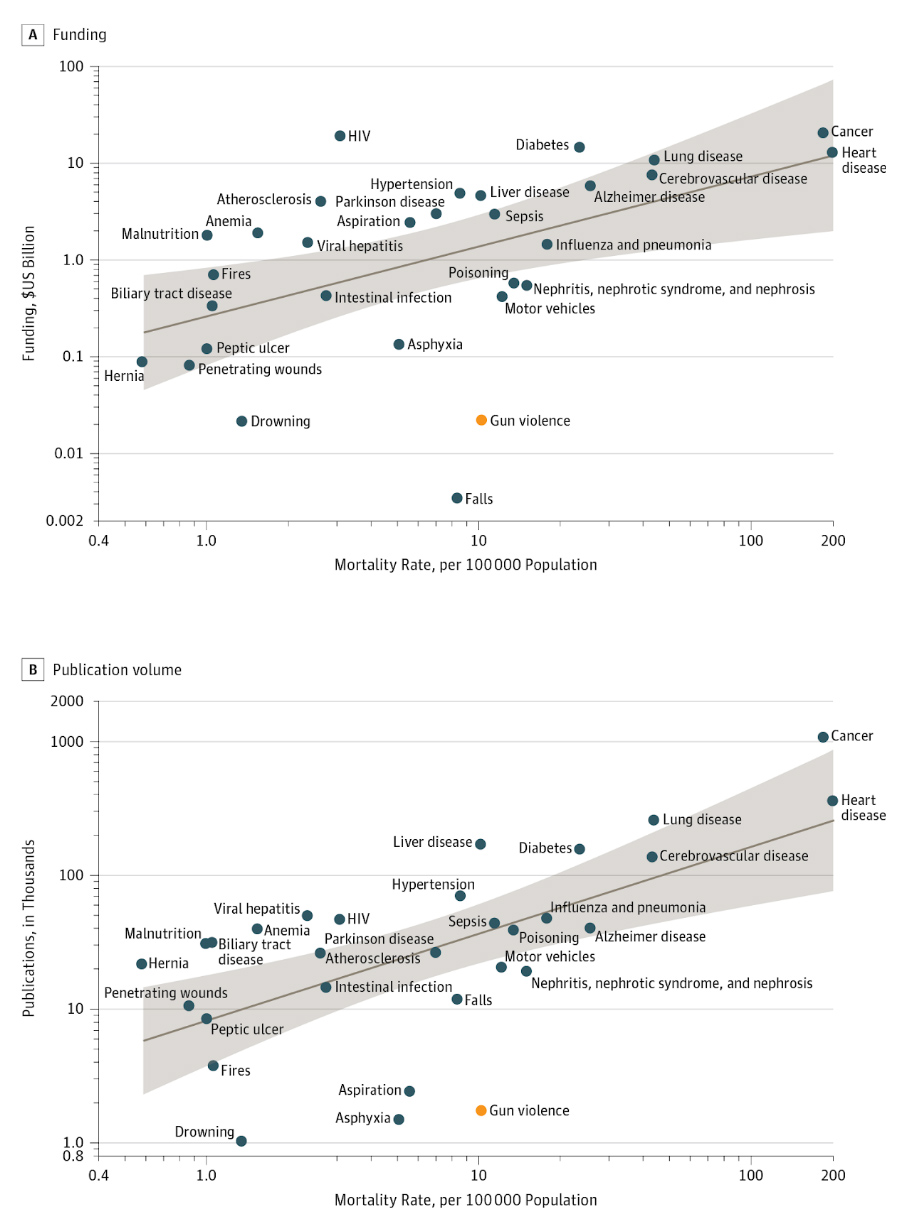

Lack of Research Prevents Better Understanding of Problem of Firearm Violence

A major stumbling block to understanding the prevalence and incidence of firearm related violence exists from a lack of rigorous scientific study of the problem. Firearm violence research constitutes less than 0.09% of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual budget ( Rajan et al. , 2018 ). Further research on firearm violence is greatly limited by the Dickey Amendment, first passed in 1996 and annually thereafter in budget appropriations, which prohibits use of federal funds to advocate or promote firearm control ( Rostron, 2018 ). As such, the Dickey Amendment impedes future federally funded research, even as public health’s interest in firearm violence prevention increased ( Peetz and Haider, 2018 ; Rostron, 2018 ). In the absence of rigorous research, a deeper understanding and development of evidence-based prevention measures continue to be needed.

Lack of a Public Health Ethical Argument Against Firearm Use Impedes Violence Prevention

We make an argument that gun violence is a public health problem. While some might think that public health is primarily about reducing health-related externalities, it is embedded in key values such as harm reduction, social justice, prevention and protection of health and social justice and equity ( Institute of Medicine, 2003 ). Public health practice is also historically intertwined with politics, power and governance, especially with the influence of the states decision-making and policies on its citizens ( Lee and Zarowsky, 2015 ). According to the World Health Organization, health is a complete physical, mental and social well-being that is not just the absence of injury or disease ( Callahan, 1973 ). Health is fundamental for human flourishing and there is a need for public health systems to protect health and prevent injuries for individuals and communities. Public health ethics, then, is the practical decision making that supports public health’s mandate to promote health and prevent disease, disability and injury in the population. It is imperative for the public health community to ask what ought to be done/can be done to curtail firearm violence and its related burdens. Sound public health ethical reasoning must be employed to support recommendations that can be used to justify various public policy interventions.

The argument that firearm violence is a public health problem could suggest that public health methods (e.g. epidemiological methods) can be used to study gun violence. Epidemiological approaches to gun violence could be applied to study its frequency, pattern, distribution, determinants and measure the effects of interventions. Public health is also an interdisciplinary field often drawing on knowledge and input from social sciences, humanities, etc. Gun violence could be viewed as a crime-related problem rather than public health; however, there are, of course, a lot of ways to study crime, and in this case with public health relevance. One dominant paradigm in criminology is the economic model which often uses natural experiments to isolate causal mechanisms. For example, it might matter whether more stringent background checks reduce the availability of guns for crime, or whether, instead, communities that implement more stringent background checks also tend to have lower rates of gun ownership to begin with, and stronger norms against gun availability. Therefore, public health authorities and criminologists may tend to have overlapping areas of expertise aimed to lead to best practices advice for gun control.

Our paper draws on three major theories: (1) rights-based theories, (2) consequentialism and (3) the common good approach. These theories make a convergent case for firearm violence, and despite their significant divergence, strengthen our public health ethics approach to firearm. The key aspects of these three theories are briefly reviewed with respect to how one might use a theory to justify an intervention or recommendation to reduce firearm injuries.

Rights-Based Theories

The basic idea of the rights framework is that people have certain rights, and that therefore it is impermissible to treat people in certain ways even if doing so would promote the overall good. People have rights to safety, security and an environment generally free from risky pitfalls. Conversely, people also have a right to own a gun especially as emphasized in the U.S.’s second amendment. Another theory embedded within our discussion of rights-based theories is deontology. Deontological approaches to ethics hold that we have moral obligations or duties that are not reducible to the need to promote some end (such as happiness or lives saved). These duties are generally thought to specify what we owe to others as persons ( rights bearers ). There are specific considerations that define moral behaviors and specific ways in which people within different disciplines ought to behave to effectively achieve their goals.

Huemer (2003) argued that the right to own a firearm has both a fundamental (independent of other rights) and derivative justification, insofar as the right is derived from another right - the right to self-defense ( Huemer, 2003 ). Huemer gives two arguments for why we have a right to own a gun:

People place lots of importance on owning a gun. Generally, the state should not restrict things that people enjoy unless doing so imposes substantial risk of harm to others.

People have a right to defend themselves from violent attackers. This entails that they have a right to obtain the means necessary to defend themselves. In a modern society, a gun is a necessary means to defend oneself from a violent attacker. Therefore, people have a right to obtain a gun.

Huemer’s first argument could be explained that it would be permissible to violate someone’s right to own or use a firearm in order to promote some impersonal good (e.g. number of lives saved). Huemer’s second argument also justifies a fundamental right to gun ownership. According to Huemer, gun restrictions violate the right of individual gun owners to defend themselves. Gun control laws will result in coercively stopping people to defend themselves when attacked. To him, the right to self-defense does seem like it would be fundamental. It seems intuitive to argue that, at some level, if someone else attacks a person out of the blue, the person is morally required to defend themselves if they cannot escape. However, having a right to self-defense does not entail that your right to obtain the means necessary to that thing cannot be burdened at all.

While we have a right to own a gun, that right is weaker than other kinds of rights. For example, gun ownership seems in no way tied to citizenship in a democracy or being a member of the community. Also, since other nations/democracies get along fine without a gun illustrates that gun ownership is not important enough to be a fundamental right. Interestingly, the UK enshrines a basic right to self-defense, but explicitly denies any right to possess any particular means of self-defense. This leads to some interesting legal peculiarities where it can be illegal to possess a handgun, but not illegal to use a handgun against an assailant in self-defense.

In the United States, implementing gun control policies to minimize gun related violence triggers the argument that such policies are infringements on the Second Amendment, which states that the rights to bear arms shall not be infringed. The constitution might include a right to gun ownership for a variety of reasons. However, it is not clear from the text itself that the right to bear arms is supposed to be as fundamental as the right to freedom of expression. Further, one could argue, then, that any form of gun regulation is borne from the rationale to retain our autonomy. Protections from gun violence are required to treat others as autonomous agents or as bearers of dignity. We owe others certain protections and affordances at least in part because these are necessary to respect their autonomy (or dignity, etc.). We discuss potential recommendations to minimize gun violence while protecting the rights of individuals to purchase a firearm if they meet the necessary and reasonable regulatory requirements. Most of the gun control regulations discussed in this article could provide an opportunity to ensure the safety of communities without unduly infringing on the right to keep a firearm.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism is the view that we should promote the common good even if doing so infringes upon some people’s (apparent) rights. The case for gun regulation under this theory is made by showing how many lives it would save. Utilitarianism, a part of consequentialist approach proposes actions which maximize happiness and the well-being for the majority while minimizing harm. Utilitarianism is based on the idea that a consequence should be of maximum benefit ( Holland, 2014 ) and that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness as the ultimate moral norm. If one believes that the moral purpose of public health is to make decisions that will produce maximal benefits for most affected, remove or prevent harm and ensure equitable distribution of burdens and benefits ( Bernheim and Childress, 2013 ), they are engaging in a utilitarian theory. Rights, including the rights to bear arms, are protected so long as they preserve the greater good. However, such rights can be overridden or ignored when they conflict with the principle of utility; that is to say, if greater harm comes from personal possession of a firearm, utilitarianism is often the ethical theory of choice to restrict access to firearms, including interventions that slow down access to firearms such as requiring a gun locker at home. However, it is important to note that utilitarians might also argue that one has to weigh how frustrating a gun locker would be to people who like to go recreationally hunting. Or how much it would diminish the feeling of security for someone who knows that if a burglar breaks in, it might take several minutes to fumble while inputting the combination on their locker to access their gun.

Using a utilitarian approach, current social statistics show that firearm violence affects a great number of people, and firearm-related fatalities and injuries threaten the utility, or functioning of another. Therefore, certain restrictions or prohibitions on firearms can be ethically justifiable to prevent harm to others using a utilitarian approach. Similarly, the infringement of individual freedom could be warranted as it protects others from serious harm. However, one might argue that a major flaw in the utilitarian argument is that it fails to see the benefit of self-defense as a reasonable benefit. Utilitarianism as a moral theory would weigh the benefits of proposed restrictions against its costs, including its possible costs to a felt sense of security on the part of gun owners. A utilitarian argument that neglects some of the costs of regulations wouldn’t be a very good argument.

One might legitimately argue that if an individual is buying a firearm, whether for protection or recreation, they are morally responsible to abide by the laws and regulations regarding purchasing that firearm and ensuring the safety of others in the society. Additionally, vendors and licensing/enforcement authorities would have the responsibility to ensure the safety of the rest of the society by ensuring that the firearm purchase does not compromise the safety of the community. Most people who own firearms would not argue against this position. However, arguments in support of measures that will reduce the availability of firearms center around freedom and liberty and are not as well tolerated by those who argue from a libertarian starting point. Further, this would stipulate that measures against firearm purchase or use impinge upon the rights of individuals who have the freedom to pursue what they perceive as good ( Holland, 2014 ). However, it seems as though the state has a fundamental duty to help ensure an adequate degree of safety for its citizens, and it seems that the best way to do that is to limit gun ownership.

Promoting the Common Good

A well-organized society that promotes the common good of all is to everyone’s advantage ( Ruger, 2015 ). In addition, enabling people to flourish in a society includes their ability to be healthy. The view of common good consists of ensuring the welfare of individuals considered as a group or the public. This group of people are presumed to have a common interest in protection and preservation from harms to the group ( Beauchamp, 1985 ). Health and security are shared by members of a community, and guns are an attempt to privatize public security and safety, and so is antithetical to the common good. Can one really be healthy or safe in a society where one’s neighbors are subject to gun violence? Maybe not, and so then this violence is a threat to one’s life too. If guns really are an effective means of self-defense, they help one defend only oneself while accepting that others in one’s community might be at risk. One might also argue that the more guns there are, the more that society accepts the legitimacy of gun ownership and the more that guns have a significant place in culture etc., and consequently, the more that there is likely to be a problem.

Trivigno (2018) suggests that the willingness to carry a firearm indicates an intention to use it if the need arises and Branas et al (2009) argue that perpetually carrying a firearm might affect how individuals behave ( Trivigno, 2018 ; Branas et al. , 2009 ). When all things are equal, will prudence and a commitment to the flourishing of others prevail? Trivigno (2013) wonders if such behaviors as carrying or having continual access to a firearm generates mistrust or triggers fear of an unknown armed assailant, allowing for aggression or anger to build; the exact opposite of flourishing ( Trivigno, 2013 ). One could suggest, then, that the recreational use of firearms is also commonly vicious. Many people use firearms to engage in blood sport, killing animals for their own amusement. For example, someone who kicks puppies or uses a magnifying glass to fry ants with the sun seems paradigmatically vicious; why not think the same of someone who shoots deer or rabbits for their amusement?. Firearm proponents might suggest that the fidelity (living out one’s commitments) or justice, which Aristotle holds in high regard, could justify carrying a firearm to protect one’s life, livelihood, or loved ones insofar as it would be just of a person to defend and protect the life of another or even one’s own life when under threat by one who means to do harm. Despite an argument justifying the use of a firearm against another for self-defense after the fact, the action might not have been right when evaluated through the previous rationale, or applying the doctrine of double effect as described by Aquinas’ passage in the Summa II-II, which mentions that self-defense is quite different than taking it upon one’s self to mete out justice ( Schlabach, n.d. ). The magistrate is charged with seeing that justice is done for the common good. At best, if guns really are an effective means of self-defense, they help one defend only oneself while accepting that others in one’s community might be at risk. They take a common good, the health and safety of the community, and make it a private one. For Aquinas and many other modern era ethicists, intention plays a critical part in judgment of an action. Accordingly, many who oppose any ownership of firearms do so in both a paternalistic fashion (one cannot intend harm if they don’t have access to firearms) and virtuous fashion (enabling human flourishing).

Classical formulations of the double doctrine effect include necessity and proportionality conditions. So, it’s wrong to kill in self-defense if you could simply run away (without giving up something morally important in doing so), or to use deadly force in self-defense when someone is trying to slap you. One thing the state can do, in its role of promoting the common good, is to reduce when it is necessary to use self-defense. If there were no police at all, then anyone who robs you without consequence will probably be back, so there’s a stronger reason to use deadly force against them to feel secure. That’s bad, because it seems to allow violence that truly isn’t necessary because no one is providing the good of public security. So, one role of the state is to reduce the number of cases in which the use of deadly force is necessary for our safety. Since most homicides in the United State involve a firearm, one way to reduce the frequency of cases in which deadly force is necessary for self-defense is to reduce the instances of gun crime.

We have attempted to lay the empirical and ethical groundwork necessary to support various interventions, and the recommendations aimed at curbing firearm violence that will be discussed in this next section. Specifically, by discussing the burden of the problem in its various forms (healthcare costs, disproportionate violence towards racial/ethnic minority groups, women, children, vulnerable populations and the lack of research) and the ethics theories public health finds most accessible, we can now turn our attention to well-known, evidence-based recommendations that could be supported by the blended ethics approach: rights-based theories, consequentialism and the common-good approach discussed.

Comprehensive, Universal Background Checks for Firearm Sales

Of the 17 million persons who submitted to a background check to purchase or transfer possession of a firearm in 2010, less than 0.5% were denied approval of purchase ( Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2014 ). At present, a background check is required only when a transfer is made by a licensed retailer, and nearly 40% of firearm transfers in recent years were private party transfers ( Miller et al. , 2017 ). As such, close to one-fourth of individuals who acquired a firearm within the last two years obtained their firearm without a background check ( Miller et al. , 2017 ). Anestis et al. , (2017) and Siegel et al. , (2019) evaluated the relationship between the types of background information required by states prior to firearm purchases and firearm homicide and suicide deaths ( Anestis et al. , 2017 ; Siegel et al. , 2019 ). Firearm homicide deaths appear lower in states checking for restraining orders and fugitive status as opposed to only conducting criminal background checks ( Sen and Panjamapirom, 2012 ). Similarly, suicide involving firearm were lower in states checking for a history of mental illness, fugitive status and misdemeanors ( Sen and Panjamapirom, 2012 ).

Research supports the evidence that comprehensive universal background checks could limit crimes associated with firearms, and enforcement of such laws and policies could prevent firearm violence ( Wintemute, 2019 ; Lee et al. , 2017 ). Comprehensive, universal background check policies that are applicable to all firearm transactions, including private party transfers, sales by firearm dealers and sales at firearm shows are justifiable using a blend of the ethics theories we have previously discussed. With the rights-based approach, one could still honor the right to own a firearm by a competent person while also enforcing the obligation of the firearm vendor to ensure only a qualified individual purchased the firearm. To further reduce gun crime, rather than ensure only the right people own guns, we can just reduce the number of guns owned overall. Consequentialism could be employed to ensure the protection of the most vulnerable such as victims of domestic violence and allowing a firearm vendor to stop a sale to an unqualified individual if they had a history of suspected or proven domestic violence. Also, having universal background checks that go beyond the bare minimum of assessing if a person has a permit, the legally required training, etc., but delving more deeply into a person’s past, such as the inclusion of a red flag ( Honberg, 2020 ), would be promoting the common good approach by creating the conditions for persons to be good and do good while propelling community safety.

Renewable License Before Buying and After Purchase of Firearm and Training Firearm Owners

At present, federal law does not require licensing for firearm owners or purchasers. However, state licensing laws fall into four categories: (1) permits to purchase firearms, (2) licenses to own firearms, (3) firearm safety certificates and (4) registration laws that impose licensing requirements ( Anestis et al. , 2015 ; Giffords Licensing, n.d. ). A study conducted in urban U.S. counties with populations greater than 200,000 indicated that permit-to-purchase laws were associated with 14% reduction in firearm homicides ( Crifasi et al. , 2018 ). In Connecticut, enforcing a mandatory permit-to-purchase law making it illegal to sell a hand firearm to anyone who did not have an eligible certificate to purchase firearms was associated with a reduction in firearm associated homicides ( Rudolph et al. , 2015 ). This also resulted in a significant reduction in the rates of firearm suicide rates in Connecticut ( Crifasi et al. , 2015 ). Conversely, the permit-to-purchase law was repealed in Missouri in 2007, which resulted in an increase of homicides with firearms and firearm suicides ( Crifasi et al. , 2015 ; Webster et al. , 2014 ). Similarly, two large Florida counties indicated that 72% of firearm suicides involved people who were legally permitted to have a firearm ( Swanson et al. , 2016 ). According to the study findings, a majority of those who were eligible to have firearms died from firearm-related suicide, and also had records of previous short-term involuntary holds that were not reportable legal events.

In addition to comprehensive, universal background checks for firearm purchases, licensing with periodic review requires the purchaser to complete an in-person application at a law enforcement agency, which could (1) minimize fraud or inaccuracies and (2) prevent persons at risk of harming themselves or others to purchase firearms ( Crifasi et al. , 2019 ). Subsequent periodic renewal could further reduce crimes and violence associated with firearms by helping law enforcement to confirm that a firearm owner remains eligible to possess firearms. More frequent licensure checks through periodic renewals could also facilitate the removal of firearms from individuals who do not meet renewal rules.

Further, including training on gun safety and shooting with every firearm license request could also be beneficial in reducing gun violence. In Japan, if you are interested in acquiring a gun license, you need to attend a one-day gun training session in addition to mental health evaluation and background check ( Alleman, 2000 ). This training teaches future firearm owners the steps they would need to follow and the responsibilities of owning a gun. The training completes with passing a written test and achieving at least a 95% accuracy during a shooting-range test. Firearm owners need to retake the class and initial exam every three years to continue to have their guns. This training and testing have contributed to the reduction in gun related deaths in Japan. Implementing such requirements could reduce gun misuses. Even though, this is a lengthy process, it could manage and reduce the risks associated with firearm purchases and will support a well-regulated firearm market. While some may argue that other forms of weapons could be used to inflict harm, reduced access to firearms would lead to a significant decrease in the number of firearm-related injuries in the United States.

From an ethics perspective, again, all three theories could be applied to the recommendation for renewable licenses and gun training. From a rights-based perspective, renewable licensure and gun training would still allow for the right to bear arms but would ensure that the right belongs with qualified persons and again would allow the proper state agency to exercise its responsibility to its citizens. Additionally, a temporary removal of firearms or prohibiting firearm purchases by people involuntarily detained in short-term holds might be an opportunity to ensure people’s safety and does so without unduly infringing on the Second Amendment rights. Renewable licenses and gun training create opportunities for law enforcement to step in periodically to ascertain if a licensee remains competent, free from criminal behavior or mental illness, which reduces the harm to the individual and to the community—a tidy application of consequentialism. Again, by creating the conditions for people to be good, we see an exercise of the common good.

Licensing Firearm Dealers and Tracking Firearm Sales

In any firearm transfer or purchase, there are two parties involved: the firearm vendor and the individual purchaser. Federal law states that “it shall be unlawful for any person, except for a licensed importer, licensed manufacturer, or licensed dealer, to engage in the business of importing, manufacturing, or dealing in firearms, or in the course of such business to ship, transport, or receive any firearm in interstate or foreign commerce” (18 U.S.C. 1 922(a)(1)(A)(2007). All firearm sellers must obtain a federal firearm license issued by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). However, ATF does not have the complete authority to inspect firearm dealers for license, revoke firearm license, or take legal actions against sellers providing firearms to criminals ( Vernick and Webster, 2007 ). Depending on individual state laws, typically the firearm purchaser maintains responsibility in obtaining the proper license for each firearm purchase whereas the justice system has the responsibility to enforce laws regulating firearm sales. Firearm manufacturers typically sell their products through licensed distributors and dealers, or a primary market (such as a retail store). Generally, firearms used to conduct a crime (including homicide) or to commit suicide are the product of secondary markets ( Institute of Medicine, 2003 ) such as retail secondhand sales or private citizen transfers/sales. Such secondary firearm transfers are largely unregulated and allow for illegal firearm purchases by persons traditionally prohibited from purchasing in the primary market ( Vernick and Webster, 2007 ; Chesnut et al. , 2017 ).

According to evidence from Irvin et al. (2014) in states that require licensing for firearm dealers and/or allow inspections, the reported rates of homicides were lower ( Irvin et al. , 2014 ). Specifically, after controlling for race, urbanicity, poverty level, sex, age, education level, drug arrest rate, burglary rates and firearm ownership proxy, the states that require licensing for firearm dealers reported ~25% less risk of homicides, and the states that allow inspection reported ~35% less risk of homicides ( Irvin et al. , 2014 ). This protective effect against homicides was stronger in states that require both licensing and inspections compared to states that require either alone. The record keeping of all firearm sales is important as it facilitates police or other authorized inspectors to compare a dealer’s inventory with their records to identify any secondary market transactions or other discrepancies ( Vernick et al. , 2006 ). According to Webster et al. (2006) , a change in firearm sales policy in the firearm store that sold more than half of the firearms recovered from criminals in Milwaukee, resulted in a 96% reduction in the use of recently sold firearms in crime and 44% decrease in the flow of new trafficked firearms in Milwaukee ( Webster et al. , 2006 ).

The licensing of firearm vendors and tracking of firearm sales sits squarely as a typical public health consequentialist argument; in order to protect the community, an individual’s right is only minimally infringed upon. An additional layer, justifiable by consequentialism, includes a national repository of all firearm sales which can be employed to minimize the sale of firearms on the secondary market and dealers could be held accountable for such ‘off-label’ use ( FindLaw Attorney Writers, 2016 ). Enforcing laws, mandating record keeping, retaining the records for a reasonable time and mandating the inspection of dealers could help to control secondary market firearm transfers and minimize firearm-related crimes and injuries.

One could argue from a rights perspective that routine inspections and record keeping are the responsibility of both firearms vendors and law enforcement, and in doing so, still ensure that competent firearm owners can maintain their rights to bear arms. In Hume’s discussion of property rights, he situates his argument in justice; and that actions must be virtuous and the motive virtuous ( Hume, 1978 ). Hume proposes that feelings of benevolence don’t form our motivation to be just. We tend (perhaps rightly) to feel stronger feelings of benevolence to those who deserve praise than to those who have wronged us or who deserve the enmity of humanity. However, justice requires treating the property rights or contracts of one’s enemies, or of a truly loathsome person, as equally binding as the property rights of honest, decent people. Gun violence disproportionately impacts underserved communities, which are same communities impacted by social and economic injustice.

Standardized Policies on Safer Storage for Firearms and Mandatory Education

Results from a cross-sectional study by Johnson and colleagues showed that about 14-30% of parents who have firearms in the home keep them loaded, while about 43% reported an unlocked firearm in the home ( Johnson et al. , 2006 ; Johnson et al. , 2008 ). The risk for unintentional fatalities from firearms can be prevented when all household firearms are locked ( Monuteaux et al. , 2019 ). Negligent storage of a firearm carries various penalties based on the individual state ( RAND, 2018 ). For example, negligent storage in Massachusetts is a felony. Mississippi and Tennessee prohibit reckless or knowingly providing firearms to minors through a misdemeanor charge, whereas Missouri and Kentucky enforce a felony charge. Also, Tennessee makes it a felony for parents to recklessly or knowingly provide firearms to their children ( RAND, 2018 ).

While a competent adult may have a right to bear arms, this right does not extend to minors, even in recreational use. Many states allow for children to participate in hunting. Wisconsin allows for children as young as 12 to purchase a hunting license, and in 2017 then Governor Scott Walker signed into law a no age minimum for a child to participate in a mentored hunt and to carry a firearm in a hunt when accompanied by an adult ( Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 2020 ). The minor’s ‘right’ to use a firearm is due in part to the adult taking responsibility for the minor’s safety. As such, some have argued that children need to know how to be safe around firearms as they continue to be one of the most pervasive consumer products in the United States ( Violano et al. , 2018 ).

In addition to locking firearms, parents are also encouraged to store firearms unloaded in a safe locked box or cabinet to prevent children’s access to firearms ( Johnson et al. , 2008 ). It follows then that reducing children and youth’s access to firearm injuries involves complying with safe firearm storage practices ( McGee et al. , 2003 ). In addition to eliminating sources of threat to the child, it is also important for children to be trained on how to safely respond in case they encounter a firearm in an unsupervised environment. Education is one of the best strategies for firearm control, storage and reduction of firearm-related injuries via development of firearm safety trainings and programs ( Jones, 1993 ; Holly et al. , 2019 ). Adults also need firearm safety education and trainings; as such, inclusion of firearm safety skills and trainings in the university-based curriculum and other avenues were adults who use guns are likely to be, could also mitigate firearm safety issues ( Puttagunta et al. , 2016 ; Damari et al. , 2018 ). Peer tutoring could also be utilized to provide training in non-academic and social settings.

Parents have a duty to protect their children and therefore mandating safe firearm storage, education and training for recreational use and periodic review of those who are within the purview of the law. Given that someone in the U. S. gets shot by a toddler a little more frequently than once a week ( Ingraham, 2017 ), others might use a utilitarian argument that limiting a child’s access to firearms minimizes the possibility of accidental discharge or intentional harm to a child or another. Again, the common good approach could be employed to justify mandatory safe storage and education to create the conditions for the flourishing of all.

Firearm and Ammunition Buy-Back Programs

Firearm and ammunition buy-back programs have been implemented in several cities in the United States to reduce the number of firearms in circulation with the ultimate goal of reducing gun violence. The first launch in Baltimore, Maryland was in 1974. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) has conducted a gun buy-back program for nearly eight years to remove more guns off the streets and improve security in communities. Currently there is a plan for a federal gun buy-back program in the United States. The objective of such programs is to reduce gun violence through motivating marginal criminals to sell their firearms to local governments, encourage law-abiding individuals to sell their firearms available for theft by would-be criminals, and to reduce firearm related suicide resulting from easy access to a gun at a time of high emotion ( Barber and Miller, 2014 ).

According to Kuhn et al. (2002) and Callahan et al. (1994) , gun buy-back programs are ineffective in reducing gun violence due to two main facts: 1- the frequently surrendered types of firearms are typically not involved in gun-related violence and 2- the majority of participants in gun buyback programs are typically women and older adults who are not often involved in interpersonal violence ( Kuhn et al. , 2002 ; Callahan et al. , 1994 ). However, as a result of implementation of the ‘‘good for guns’’ program in Worcester, Massachusetts, there has been a decline in firearm related injuries and mortality in Worcester county compared to other counties in Massachusetts ( Tasigiorgos et al. , 2015 ). Even though, there is limited research indicating a direct link between gun buy-back programs and reduction in gun violence in the United States, a gun buy-back program implemented in Australia in combination with other legislations to reduce household ownership of firearms, firearm licenses and licensed shooters was associated with a rapid decline in firearm related deaths in Australia ( Bartos et al. , 2020 ; Ozanne-Smith et al. , 2004 ).

The frequency of disparities in firearm-related violence, injuries and death makes it a central concern for public health. Even though much has been said about firearms and its related injuries, there continues to be an interest towards its use. Some people continue to desire guns due to fear, feeling of protection and safety, recreation and social pressure.

Further progress on reforms can be made through understanding the diversity of firearm owners, and further research is needed on ways to minimize risks while maximizing safety for all. Although studies have provided data on correlation between firearm possession and violence ( Stroebe, 2013 ), further research is needed to evaluate the interventions and policies that could effectively decrease the public health burden of firearm violence. Evidence-based solutions to mitigating firearm violence can be justified using three major public health ethics theories: rights-based theories, consequentialism and common good. The ethical theories discussed in this paper can direct implementation of research, policies, laws and interventions on firearm violence to significantly reduce the burden of firearm violence on individuals, health care systems, vulnerable populations and the society-at-large. We support five major steps to achieve those goals: 1. Universal, comprehensive background checks; 2. Renewable license before and after purchase of firearm; 3. Licensing firearm dealers and tracking firearm sales; 4. Standardized policies on safer storage for firearms and mandatory education; and 5. Firearm buy-back programs. For some of the goals we propose, there might be a substantial risk of non-compliance. However, we hope that through education and sensibilization programs, overtime, these goals are not met with resistance. By acknowledging the proverbial struggle of individual rights and privileges paired against population health, we hope our ethical reasoning can assist policymakers, firearm advocates and public health professionals in coming to shared solutions to eliminate unnecessary, and preventable, injuries and deaths due to firearms.

The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

Alleman , M. ( 2000 ). The Japanese Firearm and Sword Possession Control Law: Translator’s Introduction . Washington International Law Journal , 9 , 165 .

Google Scholar

Anestis , M. D. , Khazem , L. R. , Law , K. C. , Houtsma , C. , LeTard , R. , Moberg , F. and Martin , R. ( 2015 ). The Association Between State Laws Regulating Handgun Ownership and Statewide Suicide Rates . American Journal of Public Health , 105 , 2059 – 2067 .

Anestis , M. D. , Anestis , J. C. and Butterworth , S. E. ( 2017 ). Handgun Legislation and Changes in Statewide Overall Suicide Rates . American Journal of Public Health , 107 , 579 – 581 .

Bailey , J. E. , Kellermann , A. L. , Somes , G. W. , Banton , J. G. , Rivara , F. P. and Rushforth , N. P. ( 1997 ). Risk factors for violent death of women in the home . Archives of Internal Medicine , 157 , 777 – 782 .

Barber , C. W. and Miller , M. J. ( 2014 ). Reducing a suicidal person’s access to lethal means of suicide: a research agenda . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 47 , S264 – S272 .

Bartos , B. J. , McCleary , R. , Mazerolle , L. and Luengen , K. ( 2020 ). Controlling Gun Violence: Assessing the Impact of Australia’s Gun Buyback Program Using a Synthetic Control Group Experiment . Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research , 21 , 131 – 136 .

Beauchamp , D. E. ( 1985 ). Community: the neglected tradition of public health . The Hastings Center Report , 15 , 28 – 36 .

Bernheim , R.G. , Childress , J.F. ( 2013 ). Introduction: A Framework for Public Health Ethics. In Essentials of Public Health Ethics . Burlington, MA : Jones & Bartlett .

Google Preview

Branas , C. C. , Richmond , T. S. , Culhane , D. P. , Ten Have , T. R. and Wiebe , D. J. ( 2009 ). Investigating the Link Between Gun Possession and Gun Assault . American Journal of Public Health , 99 , 2034 – 2040 .

Callahan , D. ( 1973 ). The WHO definition of ‘health’ . Studies - Hastings Center , 1 , 77 – 88 .

Callahan , C. M. , Rivara , F. P. and Koepsell , T. D. ( 1994 ). Money for Guns: Evaluation of the Seattle Gun Buy-Back Program . Public Health Reports , 109 , 472 – 477 .

Calvert , S. L. , Appelbaum , M. , Dodge , K. A. , Graham , S. , Nagayama Hall , G. C. , Hamby , S. , Fasig-Caldwell , L. G. , Citkowicz , M. , Galloway , D. P. and Hedges , L. V. ( 2017 ). The American Psychological Association Task Force Assessment of Violent Video Games: Science in the Service of Public Interest . The American Psychologist , 72 , 126 – 143 .

Campbell , D. J. T. , O’Neill , B. G. , Gibson , K. and Thurston , W. E. ( 2015 ). Primary healthcare needs and barriers to care among Calgary’s homeless populations . BMC Family Practice , 16( 1 ), 139 .

Carter , P. M. , Walton , M. A. , Roehler , D. R. , Goldstick , J. , Zimmerman , M. A. , Blow , F. C. and Cunningham , R. M. ( 2015 ). Firearm Violence Among High-Risk Emergency Department Youth After an Assault Injury . Pediatrics , 135 , 805 – 815 .

Cerdá , M. ( 2016 ). Editorial: Gun Violence—Risk, Consequences, and Prevention . American Journal of Epidemiology , 183 , 516 – 517 .

Chesnut , K. Y. , Barragan , M. , Gravel , J. , Pifer , N. A. , Reiter , K. , Sherman , N. and Tita , G. E. ( 2017 ). Not an ‘iron pipeline’, but many capillaries: regulating passive transactions in Los Angeles’ secondary, illegal gun market . Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention , 23 , 226 – 231 .

Corso , P. , Finkelstein , E. , Miller , T. , Fiebelkorn , I. and Zaloshnja , E. ( 2006 ). Incidence and lifetime costs of injuries in the United States . Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention , 12 , 212 – 218 .

Crifasi , C. K. , Meyers , J. S. , Vernick , J. S. and Webster , D. W. ( 2015 ). Effects of changes in permit-to- purchase handgun laws in Connecticut and Missouri on suicide rates . Preventive Medicine , 79 , 43 – 49 .

Crifasi , C. K. , Merrill-Francis , M. , McCourt , A. , Vernick , J. S. , Wintemute , G. J. and Webster , D. W. ( 2018 ). Association between Firearm Laws and Homicide in Urban Counties . Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine , 95 , 383 – 390 .

Crifasi , C.K. , McCourt , A.D. , Webster , D.W. ( 2019 ). The Impact of Handgun Purchaser Licensing on Gun Violence . Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Gun Policy and Research .

Damari , N. D. , Ahluwalia , K. S. , Viera , A. J. and Goldstein , A. O. ( 2018 ). Continuing Medical Education and Firearm Violence Counseling . AMA Journal of Ethics , 20 , 56 – 68 .

Díez , C. , Kurland , R. P. , Rothman , E. F. , Bair-Merritt , M. , Fleegler , E. , Xuan , Z. , Galea , S. , Ross , C. S. , Kalesan , B. , Goss , K. A. and Siegel , M. ( 2017 ). State Intimate Partner Violence-Related Firearm Laws and Intimate Partner Homicide Rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015 . Annals of Internal Medicine , 167 , 536 – 543 .

Dresang , L. T. ( 2001 ). Gun deaths in rural and urban settings: recommendations for prevention . The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice , 14 , 107 – 115 .

Federal Bureau of Investigation ( 2014 ). National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Operations 2014 . Washington, DC : U.S. Department of Justice .

FindLaw Attorney Writers ( 2016 ). Responsibility of Firearm Owners and Dealers for Their Second Amendment Right to Bear Arms: A Survey of the Caselaw . Findlaw , available from: https://corporate.findlaw.com/litigation-disputes/responsibility-of-firearm-owners-and-dealers-for-their-second.html [accessed June 23, 2021 ].

Fowler , K. A. ( 2018 ). Surveillance for Violent Deaths — National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 States, 2014 . MMWR. Surveillance Summaries , 67 , 1 – 36 .

Fowler , K. A. , Dahlberg , L. L. , Haileyesus , T. and Annest , J. L. ( 2015 ). Firearm injuries in the United States . Preventive Medicine , 79 , 5 – 14 .

Gani , F. , Sakran , J. V. and Canner , J. K. ( 2017 ). Emergency Department Visits For Firearm-Related Injuries In The United States, 2006–14 . Health Affairs , 36 , 1729 – 1738 .

Giffords Law Center ( n.d .) Licensing. Available from https://giffords.org/lawcenter/gun-laws/policy-areas/owner-responsibilities/licensing/

Gollub , E. L. and Gardner , M. ( 2019 ). Firearm Legislation and Firearm Use in Female Intimate Partner Homicide Using National Violent Death Reporting System Data . Preventive Medicine , 118 , 216 – 219 .

Gramlich , J. , Schaeffer , K. ( 2019 ). 7 Facts About Guns in the U.S . Pew Research Center , available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/22/facts-about-guns-in-united-states/ [accessed September 23, 2020 ].

Hammaker , D.K. , Knadig , T.M. , Tomlinson , S.J. ( 2017 ). Environmental Safety and Gun Injury Prevention. In Health care ethics and the law . Jones & Bartlett Learning , pp. 319 – 335 .

Hargarten , S. W. , Lerner , E. B. , Gorelick , M. , Brasel , K. , deRoon-Cassini , T. and Kohlbeck , S. ( 2018 ). Gun Violence: A Biopsychosocial Disease . Western Journal of Emergency Medicine , 19 , 1024 – 1027 .

Herrin , B. R. , Gaither , J. R. , Leventhal , J. M. and Dodington , J. ( 2018 ). Rural Versus Urban Hospitalizations for Firearm Injuries in Children and Adolescents . Pediatrics , 142 ( 2 ), e20173318 .

Holland , S. ( 2014 ). Public Health Ethics . 2nd ed. Malden, MA : Polity Press .

Holly , C. , Porter , S. , Kamienski , M. and Lim , A. ( 2019 ). School-Based and Community-Based Gun Safety Educational Strategies for Injury Prevention . Health Promotion Practice , 20 , 38 – 47 .

Honberg , R. S. ( 2020 ). Mental Illness and Gun Violence: Research and Policy Options . The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics , 48 , 137 – 141 .

Huemer , M. ( 2003 ). Is There a Right to Own a Gun? Social Theory and Practice , 29 , 297 – 324 .

Hume , D. ( 1978 ). David Hume: A Treatise of Human Nature . 2nd edn. New York, United States : Oxford University Press .

Ingraham , C. ( 2017 ). Analysis | American Toddlers Are Still Shooting People on a Weekly Basis This Year . Washington Post . https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/09/29/american-toddlers-are-still-shooting-people-on-a-weekly-basis-this-year/

Institute of Medicine ( 2003 ). Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?: Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century .

Iroku-Malize , T. and Grissom , M. ( 2019 ). Violence and Public and Personal Health: Gun Violence . FP Essentials , 480 , 16 – 21 .

Irvin , N. , Rhodes , K. , Cheney , R. and Wiebe , D. ( 2014 ). Evaluating the Effect of State Regulation of Federally Licensed Firearm Dealers on Firearm Homicide . American Journal of Public Health , 104 , 1384 – 1386 .

Jehan , F. , Pandit , V. , O’Keeffe , T. , Azim , A. , Jain , A. , Tai , S. A. , Tang , A. , Khan , M. , Kulvatunyou , N. , Gries , L. and Joseph , B. ( 2018 ). The Burden of Firearm Violence in the United States: Stricter Laws Result in Safer States . Journal of Injury and Violence Research , 10 , 11 – 16 .

Johnson , R. M. , Coyne-Beasley , T. and Runyan , C. W. ( 2004 ). Firearm Ownership and Storage Practices, U.S. Households, 1992-2002. A Systematic Review . American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 27 , 173 – 182 .

Johnson , R. M. , Miller , M. , Vriniotis , M. , Azrael , D. and Hemenway , D. ( 2006 ). Are Household Firearms Stored Less Safely in Homes With Adolescents? Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine , 160 , 788 – 792 .

Johnson , R. M. , Runyan , C. W. , Coyne-Beasley , T. , Lewis , M. A. and Bowling , J. M. ( 2008 ). Storage of Household Firearms: An Examination of the Attitudes and Beliefs of Married Women With Children . Health Education Research , 23 , 592 – 602 .