Employee psychological well-being and job performance: exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms

International Journal of Organizational Analysis

ISSN : 1934-8835

Article publication date: 12 August 2020

Issue publication date: 7 May 2021

Given the importance of employee psychological well-being to job performance, this study aims to investigate the mediating role of affective commitment between psychological well-being and job performance while considering the moderating role of job insecurity on psychological well-being and affective commitment relationship.

Design/methodology/approach

The data were gathered from employees working in cellular companies of Pakistan using paper-and-pencil surveys. A total of 280 responses were received. Hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling technique and Hayes’s Model 1.

Findings suggest that affective commitment mediates the association between psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) and employee job performance. In addition, perceived job insecurity buffers the association of psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) and affective commitment.

Practical implications

The study results suggest that fostering employee psychological well-being may be advantageous for the organization. However, if interventions aimed at ensuring job security are not made, it may result in adverse employee work-related attitudes and behaviors.

Originality/value

The study extends the current literature on employee well-being in two ways. First, by examining psychological well-being in terms of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being with employee work-related attitude and behavior. Second, by highlighting the prominent role played by perceived job insecurity in explaining some of these relationships.

- Psychological well-being

- Affective commitment

- Job insecurity

- Job performance

- Eudaimonic wellbeing

- Hedonic wellbeing

Kundi, Y.M. , Aboramadan, M. , Elhamalawi, E.M.I. and Shahid, S. (2021), "Employee psychological well-being and job performance: exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms", International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 736-754. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2020-2204

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Yasir Mansoor Kundi, Mohammed Aboramadan, Eissa M.I. Elhamalawi and Subhan Shahid.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Does the employee well-being have important implications both at work and for other aspects of an employees’ life? Of course! For years, we have known that they impact life at work and a plethora of research has examined the impact of employee well-being on work outcomes (Karapinar et al. , 2019 ; Turban and Yan, 2016 ). What is less understood is how employee well-being impacts job performance. Evidence suggests that employee health and well-being are among the most critical factors for organizational success and performance (Bakker et al. , 2019 ; Turban and Yan, 2016 ). Several studies have documented that employee well-being leads to various individual and organizational outcomes such as increased organizational performance and productivity (Hewett et al. , 2018 ), customer satisfaction (Sharma et al. , 2016 ), employee engagement (Tisu et al. , 2020 ) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; Mousa et al. , 2020 ).

The organizations’ performance and productivity are tied to the performance of its employees (Shin and Konrad, 2017 ). Much evidence has shown the value of employee job performance (i.e. the measurable actions, behaviors and outcomes that employee engages in or bring about which are linked with and contribute to organizational goals; Viswesvaran and Ones, 2017 ) for organizational outcomes and success (Al Hammadi and Hussain, 2019 ; Shin and Konrad, 2017 ), which, in turn, has led scholars to seek to understand what drives employee performance. Personality traits (Tisu et al. , 2020 ), job conditions and organizational characteristics (Diamantidis and Chatzoglou, 2019 ) have all been identified as critical antecedents of employee job performance.

However, one important gap remains in current job performance research – namely, the role of psychological well-being in job performance (Hewett et al. , 2018 ). Although previous research has found happy workers to be more productive than less happy or unhappy workers (DiMaria et al. , 2020 ), a search of the literature revealed few studies on psychological well-being and job performance relationship (Salgado et al. , 2019 ; Turban and Yan, 2016 ). Also, very little is known about the processes that link psychological well-being to job performance. Only a narrow spectrum of well-being related antecedents of employee performance has been considered, especially in terms of psychological well-being. Enriching our understanding of the consequences and processes of psychological well-being in the workplace, the present study examines the relationship between psychological well-being and job performance in the workplace setting. Such knowledge will not only help managers to attain higher organizational performance during the uncertain times but will uncover how to keep employees happy and satisfied (DiMaria et al. , 2020 ).

Crucially, to advance job performance research, more work is needed to examine the relationship between employees’ psychological well-being and their job performance (Ismail et al. , 2019 ). As Salgado et al. (2019) elaborated, we need to consider how an employees’ well-being affects ones’ performance at work. In an attempt to fill this gap in the literature, the present study seeks to advance job performance research by linking ones’ psychological well-being in terms of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being to ones’ job performance. Hedonic well-being refers to the happiness achieved through experiences of pleasure and enjoyment, while eudaimonic well-being refers to the happiness achieved through experiences of meaning and purpose (Huta, 2016 ; Rahmani et al. , 2018 ). We argue that employees with high levels of psychological well-being will perform well as compared to those having lower levels of psychological well-being. We connect this psychological well-being-job performance process through an employee affective commitment (employees’ perceptions of their emotional attachment to or identification with their organization; Allen and Meyer, 1996 ) – by treating it as a mediating variable between well-being-performance relationship.

Additionally, we also examine the moderating role of perceived job insecurity in the well-being-performance relationship. Perceived job insecurity refers to has been defined as the perception of being threatened by job loss or an overall concern about the continued existence of the job in the future (De Witte et al. , 2015 ). There is evidence that perceived job insecurity diminishes employees’ level of satisfaction and happiness and may lead to adverse job-related outcomes such as decreased work engagement (Karatepe et al. , 2020 ), deviant behavior (Soomro et al. , 2020 ) and reduced employee performance (Piccoli et al. , 2017 ). Thus, addressing the gap mentioned above, this study has two-fold objectives; First, to examine how the path between psychological well-being and job performance is mediated through employee affective commitment. The reason to inquire about this path is that well-being is associated with an employees’ happiness, pleasure and personal growth (Ismail et al. , 2019 ). Therefore, higher the well-being, higher will be the employees’ affective commitment, which, in turn, will lead to enhanced job performance. The second objective is to empirically test the moderating effects of perceived job insecurity on employees’ emotional attachment with their organizations. Thus, we propose that higher job insecurity may reduce the well-being of employees and their interaction may result in lowering employees’ emotional attachment with their organization.

The present study brings together employee well-being and performance literature and contributes to these research areas in two ways. First, we contribute to this line of inquiry by investigating the direct and indirect crossover from hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being to employees’ job performance. We propose that psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) influence job performance through employee affective commitment. Second, prior research shows that the effect of well-being varies across individuals indicating the presence of possible moderators influencing the relationship between employee well-being and job outcomes (Lee, 2019 ). We, therefore, extend the previous literature by proposing and demonstrating the general possibility that perceived job insecurity might moderate the relationship of psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) and affective commitment. While there is evidence that perceived job insecurity influence employees’ affective commitment (Schumacher et al. , 2016 ), what is not yet clear is the impact of perceived job insecurity on psychological well-being − affective commitment relationship. The proposed research model is depicted in Figure 1 .

2. Hypotheses development

2.1 psychological well-being and affective commitment.

Well-being is a broad concept that refers to individuals’ valued experience (Bandura, 1986 ) in which they become more effective in their work and other activities (Huang et al. , 2016 ). According to Diener (2009) , well-being as a subjective term, which describes people’s happiness, the fulfillment of wishes, satisfaction, abilities and task accomplishments. Employee well-being is further categorized into two types, namely, hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being (Ballesteros-Leiva et al. , 2017 ). Compton et al. (1996) investigated 18 scales that assess employee well-being and found that all the scales are categorized into two broad categories, namely, subjective well-being and personal growth. The former is referred to as hedonic well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000 ) whereas, the latter is referred to as eudaimonic well-being (Waterman, 1993 ).

Hedonic well-being is based on people’s cognitive component (i.e. people’s conscious assessment of all aspects of their life; Diener et al. , 1985 ) and affective component (i.e. people’s feelings that resulted because of experiencing positive or negative emotions in reaction to life; Ballesteros-Leiva et al. , 2017 ). In contrast, eudaimonic well-being describes people’s true nature and realization of their actual potential (Waterman, 1993 ). Eudaimonic well-being corresponds to happy life based upon ones’ self-reliance and self-truth (Ballesteros-Leiva et al. , 2017 ). Diener et al. (1985) argued that hedonic well-being focuses on happiness and has a more positive affect and greater life satisfaction, and focuses on pleasure, happiness and positive emotions (Ryan and Deci, 2000 ; Ryff, 2018 ). Contrarily, eudaimonic well-being is different from hedonic well-being as it focuses on true self and personal growth (Waterman, 1993 ), recognition for ones’ optimal ability and mastery ( Ryff, 2018 ). In the past, it has been found that hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being are relatively correlated with each other but are distinct concepts (Sheldon et al. , 2018 ).

To date, previous research has measured employee psychological well-being with different indicators such as thriving at work (Bakker et al. , 2019 ), life satisfaction (Clark et al. , 2019 ) and social support (Cai et al. , 2020 ) or general physical or psychological health (Grey et al. , 2018 ). Very limited studies have measured psychological well-being with hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, which warrants further exploration (Ballesteros-Leiva et al. , 2017 ). Therefore, this study assesses employee psychological well-being based upon two validated measures, namely, hedonic well-being (people’s satisfaction with life in general) and eudaimonic well-being (people’s personal accomplishment feelings).

Employee well-being has received some attention in organization studies (Huang et al. , 2016 ). Prior research has argued that happier and healthier employees increase their effort, performance and productivity (Huang et al. , 2016 ). Similarly, research has documented that employee well-being has a positive influence on employee work-related attitudes and behaviors such as, increasing OCB (Mousa et al. , 2020 ), as well as job performance (Magnier-Watanabe et al. , 2017 ) and decreasing employees’ work-family conflict (Karapinar et al. , 2019 ) and absenteeism (Schaumberg and Flynn, 2017 ). Although there is evidence that employee well-being positively influences employee work-related attitudes, less is known about the relationship between psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) and employee affective commitment (Pan et al. , 2018 ; Semedo et al. , 2019 ). Moreover, the existing literature indicated that employee affective commitment is either used as an antecedent or an outcome variable of employee well-being (Semedo et al. , 2019 ; Ryff, 2018 ). However, affective commitment as an outcome variable of employee well-being has gained less scholarly attention, which warrants further investigation. Therefore, in the present study, we seek to examine employee affective commitment as an outcome variable of employee psychological well-being because employees who are happy and satisfied in their lives are more likely to be attached to their organizations (Semedo et al. , 2019 ).

Hedonic well-being positively predicts employee affective commitment.

Eudaimonic well-being positively predicts employee affective commitment.

2.2 Affective commitment and job performance

The concept of organizational commitment was first initiated by sit-bet theory in the early 1960s (Becker, 1960 ). Organizational commitment is defined as the psychological connection of employees to the organization and involvement in it (Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005 ). It is also defined as the belief of an individual in his or her organizational norms (Hackett et al. , 2001 ); the loyalty of an employee toward the organization (Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005 ) and willingness of an employee to participate in organizational duties (Williams and Anderson, 1991 ).

Organizational commitment is further categorized into three correlated but distinct categories (Meyer et al. , 1993 ), known as affective, normative and continuance. In affective commitment, employees are emotionally attached to their organization. In normative commitment, employees remain committed to their organizations due to the sense of obligation to serve. While in continuance commitment, employees remain committed to their organization because of the costs associated with leaving the organization (Allen and Meyer, 1990 , p. 2). Among the dimensions of organizational commitment, affective commitment has been found to have the most substantial influence on organizational outcomes (Meyer and Herscovitch, 2001 ). It is a better predictor of OCB (Paul et al. , 2019 ), low turnover intention (Kundi et al. , 2018 ) and job performance (Jain and Sullivan, 2019 ).

Affective commitment positively predict employee job performance.

2.3 Affective commitment as a mediator

Many studies had used the construct of affective commitment as an independent variable, mediator and moderating variable because of its importance as an effective determinant of work outcomes such as low turnover intention, job satisfaction and job performance (Jain and Sullivan, 2019 ; Kundi et al. , 2018 ). There is very little published research on employee well-being and affective commitment relationship. Surprisingly, the effects of employee psychological well-being in terms of hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being have not been closely examined.

Affective commitment mediates the association between hedonic well-being and job performance.

Affective commitment mediates the association between eudaimonic well-being and job performance.

2.4 The moderating role of job insecurity

Job insecurity is gaining importance because of the change in organizational structure as it is becoming flattered, change in the nature of the job as it requires a diverse skill set and change in human resource (HR) practices as more temporary workers are hired nowadays (Piccoli et al. , 2017 ; Kundi et al. , 2018 ). Such changes have caused several adverse outcomes such as job dissatisfaction (Bouzari and Karatepe, 2018 ), unethical pro-organizational behavior (Ghosh, 2017 ), poor performance (Piccoli et al. , 2017 ), anxiety and lack of commitment (Wang et al. , 2018 ).

Lack of harmony on the definition of job insecurity can be found among the researchers. However, a majority of them acknowledge that job insecurity is subjective and can be referred to as a subjective perception (Wang et al. , 2018 ). Furthermore, job insecurity is described as the perception of an employee regarding the menace of losing a job in the near future (De Witte et al. , 2015 ). When there is job insecurity, employees experience a sense of threat to the continuance and stability of their jobs (Shoss, 2017 ).

Although job insecurity has been found to influence employee work-related attitudes, less is known about its effects on behavioral outcomes (Piccoli et al. , 2017 ). As maintained by the social exchange theory, behaviors are the result of an exchange process (Blau, 1964 ). Furthermore, these exchanges can be either tangible or socio-emotional aspects of the exchange process (Kundi et al. , 2018 ). Employees who perceive and feel that their organization is providing them job security and taking care of their well-being will turn to be more committed to their organization (Kundi et al. , 2018 ; Wang et al. , 2018 ). Much research has found that employees who feel job security are happier and satisfied with their lives (Shoss, 2017 ; De Witte et al. , 2015 ) and are more committed to their work and organization (Bouzari and Karatepe, 2018 ; Wang et al. , 2018 ). Shoss (2017) conducted a thorough study on job insecurity and found that job insecurity can cause severe adverse consequences for both the employees and organizations.

Employees who are uncertain about their jobs (i.e. high level of perceived job insecurity) are less committed with their organizations.

Employees with temporary job contracts were found to have low organizational committed as compared to the employees with permanent job contracts.

Such a difference between temporary and permanent job contract holders was mainly due to the perceived job insecurity by the temporary job contract holders.

Job insecurity will moderate the relationship between hedonic well-being, eudaimonic well-being and affective organizational commitment.

3.1 Sample and procedure

The data for this study came from a survey of Pakistani employees, who worked in five private telecommunication organizations (Mobilink, Telenor, Ufone, Zong and Warid). These five companies were targeted because they are the largest and highly competitive companies in Pakistan. Moreover, the telecom sector is a private sector where jobs are temporary or contractual (Kundi et al. , 2018 ). Hence, the investigation of how employees’ perceptions of job insecurity influence their psychological well-being and its outcomes is highly relevant in this context. Studies exploring such a phenomenon are needed, particularly in the Pakistani context, to have a better insight and thereby strengthen the employee well-being and job performance literature.

Two of the authors had personal and professional contacts to gain access to these organizations. The paper-and-pencil method was used to gather the data. Questionnaires were distributed among 570 participants with a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, noted that participation was voluntary, and provided assurances that their responses would be kept confidential and anonymous. After completion of the questionnaires, the surveys were collected the surveys on-site by one of the authors. As self-reported data often render itself to common method bias (CMB; Podsakoff et al. , 2012 ), we applied several procedural remedies such as reducing the ambiguity in the questions, ensuring respondent anonymity and confidentiality, separating of the predictor and criterion variable and randomizing the item order to limit this bias.

Of the 570 surveys distributed initially, 280 employees completed the survey form (response rate = 49%). According to Baruch and Holtom (2008) , the average response rate for studies at the individual level is 52.6% (SD = 19.7). Hence, our response rate meets the standard for a minimum acceptable response rate, which is 49%. Of the 280 respondents, 39% were female, their mean age was 35.6 years (SD = 5.22) and the average organizational tenure was 8.61 years (SD = 4.21). The majority of the respondents had at least a bachelors’ degree (83 %). Respondents represented a variety of departments, including marketing (29%), customer services (26%), finance (20%), IT (13%) and HR (12%).

3.2 Measures

The survey was administered to the participants in English. English is the official language of correspondence for professional organizations in Pakistan (De Clercq et al. , 2019 ). All the constructs came from previous research and anchored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree.

Psychological well-being. We measured employee psychological well-being with two sub-dimensions, namely, hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being. Hedonic well-being was measured using five items (Diener et al. , 1985 ). A sample item is “my life conditions are excellent” ( α = 0.86). Eudaimonic well-being was measured using 21 items (Waterman et al. , 2010 ), of which seven items were reverse-scored due to its negative nature. Sample items are “I feel that I understand what I was meant to do in my life” and “my life is centered around a set of core beliefs that give meaning to my life” ( α = 0.81).

Affective commitment. The affective commitment was measured using a six-item inventory developed by Allen and Meyer (1990) . The sample items are “my organization inspires me to put forth my best effort” and “I think that I will be able to continue working here” ( α = 0.91).

Job insecurity. Job insecurity was measured using a five-item inventory developed by Chirumbolo et al. (2015) . The sample item is “I fear I will lose my job” ( α = 0.87).

Job performance . We measured employee job performance with the seven-item inventory developed by Williams and Anderson (1991) . The sample items are “I do fulfill my responsibilities, which are mentioned in the job description” and “I try to work as hard as possible” ( α = 0.87).

Controls. We controlled for respondents’ age (assessed in years), gender (1 = male, 2 = female) and organizational tenure (assessed in years) because prior research (Alessandri et al. , 2019 ; Edgar et al. , 2020 ) has found significant effects of these variables on employees’ job performance.

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations among study variables.

4.2 Construct validity

Before testing hypotheses, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyzes (CFAs) using AMOS 22.0 to examine the distinctiveness of our study variables. Following the guidelines of Hu and Bentler (1999) , model fitness was assessed with following fit indices; comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). We used a parceling technique (Little et al. , 2002 ) to ensure item to sample size ratio. According to Williams and O’Boyle (2008) , the item-parceling approach is widely used in HRM research, which allows estimation of fewer model parameters and subsequently leads to the optimal variable to sample size ratio and stable parameter estimates (Wang and Wang, 2019 ). Based on preliminary CFAs, we combined the highest item loading with the lowest item loading to create parcels that were equally balanced in terms of their difficulty and discrimination. Item-parceling was done only for the construct of eudaimonic well-being as it entailed a large number of items (i.e. 21 items). Accordingly, we made five parcels for the eudaimonic well-being construct (Waterman et al. , 2010 ).

As shown in Table 2 , the CFA results revealed that the baseline five‐factor model (hedonic well-being, eudaimonic well-being, job insecurity, affective commitment and job performance) was significant ( χ 2 = 377.11, df = 199, CFI = 0.971, RMSEA = 0.034 and SRMR = 0.044) and better than the alternate models, including a four‐factor model in which hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being were considered as one construct (Δ χ 2 = 203.056, Δdf = 6), a three-factor model in which hedonic well-being, eudaimonic well-being and affective commitment were loaded on one construct (Δ χ 2 = 308.99, Δdf = 8) and a one‐factor model in which all items loaded on one construct (Δ χ 2 = 560.77, Δdf = 11). The results, therefore, provided support for the distinctive nature of our study variables.

To ensure the validity of our measures, we first examined the convergent validity through the average variance extracted (AVE). We found AVE scores higher than the threshold value of 0.5 ( Table 1 ; Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ), supporting the convergent validity of our constructs. We also estimated discriminant validity by comparing the AVE of each construct with the average shared variance (ASV), i.e. mean of the squared correlations among constructs ( Hair et al. , 2010 ). As expected, all the values of AVE were higher than the ASV constructs, thereby supporting discriminant validity ( Table 1 ).

4.3 Common method variance

Harman’s one-factor test.

CFA ( Podsakoff et al. , 2012 ).

Harman’s one-factor test showed five factors with eigenvalues of greater than 1.0 accounted for 69.12% of the variance in the exogenous and endogenous variables. The results of CFA showed that the single-factor model did not fit the data well ( χ 2 = 937.88, df = 210, CFI = 0.642, RMSEA = 0.136, SRMR = 0.122). These tests showed that CMV was not a major issue in this study.

4.4 Hypotheses testing

The hypotheses pertaining to mediation were tested using a structural model in AMOS 22.0 ( Figure 2 ), which had an acceptable goodness of fit ( χ 2 = 298.01, df = 175, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04 and SRMR = 0.04). Hypotheses about moderation were tested in SPSS (25 th edition) using PROCESS Model I ( Hayes, 2017 ; Table 3 ).

H1a and H1b suggested that hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being positively relate to employee affective commitment. According to Figure 2 , the results indicate that hedonic well-being ( β = 0.26, p < 0.01) and eudaimonic well-being ( β = 0.32, p < 0.01) are positively related to employee affective commitment. Taken together, these two findings provide support for H1a and H1b . In H2 , we predicted that employee affective commitment would positively associate with employee job performance. As seen in Figure 2 , employee affective commitment positively predicted employee job performance ( β = 0.41, p < 0.01), supporting H2 .

H3a and H3b suggested that employee affective commitment mediates the relationship between hedonic and eudaimonic well-being and employee job performance. According to Figure 2 , the results indicate that hedonic well-being is positively related to employee job performance via employee affective commitment ( β = 0.11, 95% CI = 0.09; 0.23). Similarly, eudaimonic well-being is positively related to employee job performance via employee affective commitment ( β = 0.15, 95% CI = 0.12; 0.35), supporting H3a and H3b .

Hedonic well-being.

Eudaimonic well-being and employee affective commitment.

In support of H4a , our results ( Table 3 ) revealed a negative and significant interaction effect between hedonic well-being and job insecurity on employee affective commitment ( β = −0.12, p < 0.05). The pattern of this interaction was consistent with our hypothesized direction; the positive relationship between hedonic well-being and employee affective commitment was weaker in the presence of high versus low job insecurity ( Figure 3 ). Likewise, the interaction effect between eudaimonic well-being and job insecurity on employee affective commitment was negatively significant ( β = −0.28, p < 0.01). The pattern of this interaction was consistent with our hypothesized direction; the positive relationship between eudaimonic well-being and employee affective commitment was weaker in the presence of high versus low job insecuritay ( Figure 4 ). Thus, H4a and H4b were supported. The pattern of these interactions was consistent with our hypothesized direction; the positive relationship of hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being with an employee affective commitment were weaker in the presence of high versus low perceived job insecurity.

5. Discussion

The present research examined the direct and indirect crossover from psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) to job performance through employee affective commitment and the moderating role of job insecurity between psychological well-being and affective commitment relationship. The results revealed that both hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being has a direct and indirect effect on employee job performance. Employee affective commitment was found to be a potential mediating mechanism (explaining partial variance) in the relationship between psychological well-being and job performance. Findings regarding the buffering role of job insecurity revealed that job insecurity buffers the positive relationship between psychological well-being and employee affective commitment such that higher the job insecurity, lower will be employee affective commitment. The findings generally highlight and reinforce that perceived job insecurity can be detrimental for both employees’ well-being and job-related behaviors (Soomro et al. , 2020 ).

5.1 Theoretical implications

The present study offers several contributions to employee well-being and job performance literature. First, the present research extends the employee well-being literature by investigating employee affective commitment as a key mechanism through which psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) influences employees’ job performance. In line with SDT, we found that both hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being enhanced employees’ affective commitment, which, in turn, led them to perform better in their jobs. Our study addresses recent calls for research to understand better how psychological well-being influence employees’ performance at work (Huang et al. , 2016 ), and adds to a growing body of work, which confirms the importance of psychological well-being in promoting work-related attitudes and behaviors (Devonish, 2016 ; Hewett et al. , 2018 ; Ismail et al. , 2019 ). Further, we have extended the literature on employee affective commitment, highlighting that psychological well-being is an important antecedent of employee’ affective commitment and thereby confirming previous research by Aboramadan et al. (2020) on the links between affective commitment and job performance.

Second, our results provide empirical support for the efficacy of examining the different dimensions of employee well-being, i.e. hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being as opposed to an overall index of well-being at work. Specifically, our results revealed that both hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being boost both employees’ attachment with his or her organization and job performance (Hewett et al. , 2018 ; Luu, 2019 ). Among the indicators of psychological well-being, eudaimonic well-being (i.e. realization and fulfillment of ones’ true nature) was found to have more influence on employee affective commitment and job performance as compared to hedonic well-being (i.e. state of happiness and sense of flourishing in life). Therefore, employees who experience high levels of psychological well-being are likely to be more attached to their employer, which, in turn, boosts their job performance.

Third, job insecurity is considered as an important work-related stressor (Schumacher et al. , 2016 ). However, the moderating role of job insecurity on the relationship between psychological well-being and affective commitment has not been considered by the previous research. Based on social exchange theory (Blau, 1964 ), we expected job insecurity to buffer the positive relationship between the psychological well-being and affective commitment. The results showed that employees with high levels of perceived job insecurity reduce the positive relationship of psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) and affective commitment. This finding is consistent with previous empirical evidence supporting the adverse role of perceived job insecurity in reducing employees’ belongingness with their organization (Jiang and Lavaysse, 2018 ). There is strong empirical evidence (Qian et al. , 2019 ; Schumacher et al. , 2016 ) that employee attitudes and health are negatively affected by increasing levels of job insecurity. Schumacher et al. (2016) suggested in an elaborate explanation of the social exchange theory that the constant worrying about the possibility of losing ones’ job promotes psychological stress and feelings of unfairness, which, in turn, affects employees’ affective commitment. Hence, employees’ psychological well-being and affective commitment are heavily influenced by the experience of high job insecurity.

5.2 Practical implications

Our study has several implications. First and foremost, this study will help managers in understanding the importance of employees’ psychological well-being for work-related attitudes and behavior. Based on our findings, managers need to understand how important psychological well-being is for employees’ organizational commitment and job performance. According to Hosie and Sevastos (2009) , several human resource-based interventions could foster employees’ psychological well-being, such as selecting and placing employees into appropriate positions, ensuring a friendly work environment and providing training that improves employees’ mental health and help them to manage their perceptions positively.

Besides, managers should provide their employees with opportunities to use their full potential, which will increase employees’ sense of autonomy and overall well-being (Sharma et al. , 2017 ). By promoting employee well-being in the workplace, managers can contribute to developing a workforce, which will be committed to their organizations and will have better job performance. However, based on our findings, in the presence of job insecurity, organizations spending on interventions to improve employees’ psychological well-being, organizational commitment and job performance might go in vain. In other words, organizations should ensure that employees feel a sense of job security or else the returns on such interventions could be nullified.

Finally, as organizations operate in a volatile and highly competitive environment, it is and will be difficult for them to provide high levels of job security to their employees, especially in developing countries such as Pakistan (Soomro et al. , 2020 ). Given the fact that job insecurity leads to cause adverse employee psychological well-being and affective commitment, managers must be attentive to subordinates’ perceptions of job insecurity and adverse psychological well-being and take action to prevent harmful consequences (Ma et al. , 2019 ). Organizations should try to avoid downsizings, layoffs and other types of structural changes, respectively, and find ways to boost employees’ perceptions of job security despite those changes. If this is not possible, i.e. the organization not able to provide job security, this should be communicated to employees honestly and early.

5.3 Limitations and future studies

There are several limitations to this study. First, we measured our research variables by using a self-report survey at a single point of time, which may result in CMB. We used various procedural remedies to mitigate the potential for CMB and conducted CFA as per the guidelines of Podsakoff et al. (2012) to ensure that CMV was unlikely to be an issue in our study. However, future research may rely on supervisors rated employees’ job performance or collect data at different time points to avoid the threat of such bias.

Second, the sample of this study consisted of employees working in cellular companies of Pakistan with different demographic characteristics and occupational backgrounds; thus, the generalizability of our findings to other industries or sectors is yet to be established. Future research should test our research model in various industries and cultures.

A final limitation pertains to the selection of a moderating variable. As this study was conducted in Pakistan, contextual factors such as the perceived threat to terrorism, law and order situation or perceived organizational injustice might also influence the psychological well-being of employees working in Pakistan (Jahanzeb et al. , 2020 ; Sarwar et al. , 2020 ). Future studies could consider the moderating role of such external factors in the relationship between employee psychological well-being, affective commitment and job performance.

6. Conclusion

This study proposed a framework to understand the relationship between employee psychological well-being, affective commitment and job performance. It also described how psychological well-being influences job performance. Additionally, this study examined the moderating role of perceived job insecurity on psychological well-being and affective commitment relationship. The results revealed that employee psychological well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic) has beneficial effects on employee affective commitment, which, in turn, enhance their job performance. Moreover, the results indicated that perceived job insecurity has ill effects on employee affective commitment, especially when the employee has high levels of perceived job insecurity.

Research model

Structural model with standardized coefficients; N = 280

Interactive effect of hedonic well-being and job insecurity on employee affective commitment

Interactive effect of eudaimonic well-being and job insecurity on employee affective commitment

Descriptive statistics and correlations among of variables

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01; Unstandardized coefficients and average bootstrap estimates are stated; demographic variables are controlled; bootstrapping procedure [5,000 iterations, bias-corrected, 95% CI]

Aboramadan , M. , Dahleez , K. and Hamad , M.H. ( 2020 ), “ Servant leadership and academics outcomes in higher education: the role of job satisfaction ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 1 .

Alessandri , G. , Truxillo , D.M. , Tisak , J. , Fagnani , C. and Borgogni , L. ( 2019 ), “ Within-individual age-related trends, cycles, and event-driven changes in job performance: a career-span perspective ”, Journal of Business and Psychology , Vol. 1 , pp. 1 - 20 .

Allen , N.J. and Meyer , J.P. ( 1990 ), “ The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization ”, Journal of Occupational Psychology , Vol. 63 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 18 .

Allen , N.J. and Meyer , J.P. ( 1996 ), “ Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: an examination of construct validity ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 49 No. 3 , pp. 252 - 276 .

Al Hammadi , F. and Hussain , M. ( 2019 ), “ Sustainable organizational performance: a study of health-care organizations in the United Arab Emirates ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 169 - 186 .

Bakker , A.B. , Hetland , J. , Olsen , O.K. and Espevik , R. ( 2019 ), “ Daily strengths use and employee wellbeing: the moderating role of personality ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 92 No. 1 , pp. 144 - 168 .

Ballesteros-Leiva , F. , Poilpot-Rocaboy , G. and St-Onge , S. ( 2017 ), “ The relationship between life-domain interactions and the wellbeing of internationally mobile employees ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 46 No. 2 , pp. 237 - 254 .

Bandura , A. ( 1986 ), Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social-Cognitive View , Prentice-Hall , Englewood Cliffs, NJ .

Baruch , Y. and Holtom , B.C. ( 2008 ), “ Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research ”, Human Relations , Vol. 61 No. 8 , pp. 1139 - 1160 .

Blau , P.M. ( 1964 ), Exchange and Power in Social Life , Wiley , New York, NY .

Becker , H.S. ( 1960 ), “ Notes on the concept of commitment ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 66 No. 1 , pp. 32 - 40 .

Bouzari , M. and Karatepe , O.M. ( 2018 ), “ Antecedents and outcomes of job insecurity among salespeople ”, Marketing Intelligence and Planning , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 290 - 302 .

Cai , L. , Wang , S. and Zhang , Y. ( 2020 ), “ Vacation travel, marital satisfaction, and subjective wellbeing: a chinese perspective ”, Journal of China Tourism Research , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 118 - 139 .

Chirumbolo , A. , Hellgren , J. , De Witte , H. , Goslinga , S. , NäSwall , K. and Sverke , M. ( 2015 ), “ Psychometrical properties of a short measure of job insecurity: a European cross-cultural study ”, Rassegna di Psicologia , Vol. 3 , pp. 83 - 98 .

Clark , B. Chatterjee , K. Martin , A. and Davis , A. ( 2019 ), “ How commuting affects subjective wellbeing ”, Transportation .

Compton , W.C. , Smith , M.L. , Cornish , K.A. and Qualls , D.L. ( 1996 ), “ Factor structure of mental health measures ”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , Vol. 71 No. 2 , pp. 406 - 413 .

Cooper-Hakim , A. and Viswesvaran , C. ( 2005 ), “ The construct of work commitment: testing an integrative framework ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 131 No. 2 , pp. 241 - 259 .

De Clercq , D. , Haq , I.U. and Azeem , M.U. ( 2019 ), “ Perceived contract violation and job satisfaction: buffering roles of emotion regulation skills and work-related self-efficacy ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 383 - 398 .

De Witte , H. and Näswall , K. ( 2003 ), “ Objective’ vs subjective’ job insecurity: consequences of temporary work for job satisfaction and organizational commitment in four European countries ”, Economic and Industrial Democracy , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 149 - 188 .

De Witte , H. Vander Elst , T. and De Cuyper , N. ( 2015 ), “ Job insecurity, health and well-being ”, Sustainable Working Lives , pp. 109 - 128 .

Deci , E.L. and Ryan , R.M. ( 1985 ), Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior , Springer Science and Business Media New York, NY .

Devonish , D. ( 2016 ), “ Emotional intelligence and job performance: the role of psychological well-being ”, International Journal of Workplace Health Management , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 428 - 442 .

Diamantidis , A.D. and Chatzoglou , P. ( 2019 ), “ Factors affecting employee performance: an empirical approach ”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management , Vol. 68 No. 1 , pp. 171 - 193 .

Diener , E. ( 2009 ), “ Subjective well-being ”, In The Science of Wellbeing , Springer , Dordrecht , pp. 11 - 58 .

Diener , E. , Emmons , R.A. , Larsen , R.J. and Griffin , S. ( 1985 ), “ The satisfaction with life scale ”, Journal of Personality Assessment , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 71 - 75 .

DiMaria , C.H. , Peroni , C. and Sarracino , F. ( 2020 ), “ Happiness matters: productivity gains from subjective well-being ”, Journal of Happiness Studies , Vol. 21 No. 1 , pp. 139 - 160 .

Edgar , F. , Blaker , N.M. and Everett , A.M. ( 2020 ), “ Gender and job performance: linking the high performance work system with the ability–motivation–opportunity framework ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 1

Fornell , C. and Larcker , D.F. ( 1981 ), “ Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 18 No. 1 , pp. 39 - 50 .

Ghosh , S.K. ( 2017 ), “ The direct and interactive effects of job insecurity and job embeddedness on unethical pro-organizational behavior ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 46 No. 6 , pp. 1182 - 1198 .

Grey , J.M. , Totsika , V. and Hastings , R.P. ( 2018 ), “ Physical and psychological health of family carers co-residing with an adult relative with an intellectual disability ”, Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities , Vol. 31 , pp. 191 - 202 .

Hackett , R.D. , Lapierre , L.M. and Hausdorf , P.A. ( 2001 ), “ Understanding the links between work commitment constructs ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 58 No. 3 , pp. 392 - 413 .

Hair , J.F. , Black , W.C. , Babin , B.J. and Anderson , R.E. ( 2010 ), Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective 7e , Pearson , Upper Saddle River, NJ .

Hayes , A.F. ( 2017 ), Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach , Guilford publications , New York .

Hewett , R. , Liefooghe , A. , Visockaite , G. and Roongrerngsuke , S. ( 2018 ), “ Bullying at work: cognitive appraisal of negative acts, coping, well-being, and performance ”, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 71 .

Hosie , P.J. and Sevastos , P. ( 2009 ), “ Does the “happy‐productive worker” thesis apply to managers? ”, International Journal of Workplace Health Management , Vol. 2 No. 2 , pp. 131 - 160 .

Hu , L. and Bentler , P.M. ( 1999 ), “ Cut-off criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives ”, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal , Vol. 6 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 55 .

Huang , L.-C. , Ahlstrom , D. , Lee , A.Y.-P. , Chen , S.-Y. and Hsieh , M.-J. ( 2016 ), “ High performance work systems, employee wellbeing, and job involvement: an empirical study ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 45 No. 2 , pp. 296 - 314 .

Huta , V. ( 2016 ), “ An overview of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being concepts ”, Handbook of Media Use and Wellbeing: International Perspectives on Theory and Research on Positive Media Effects , Routldge London pp. 14 - 33 .

Ismail , H.N. , Karkoulian , S. and Kertechian , S.K. ( 2019 ), “ Which personal values matter most? job performance and job satisfaction across job categories ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 109 - 124 .

Jahanzeb , S. , De Clercq , D. and Fatima , T. ( 2020 ), “ Organizational injustice and knowledge hiding: the roles of organizational dis-identification and benevolence ”, Management Decision , Vol. 1 .

Jain , A.K. and Sullivan , S. ( 2019 ), “ An examination of the relationship between careerism and organizational commitment, satisfaction, and performance ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 1 .

Jiang , L. and Lavaysse , L.M. ( 2018 ), “ Cognitive and affective job insecurity: a meta-analysis and a primary study ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 44 No. 6 , pp. 2307 - 2342 .

Karapinar , P.B. , Camgoz , S.M. and Ekmekci , O.T. ( 2019 ), “ Employee well-being, workaholism, work–family conflict and instrumental spousal support: a moderated mediation model ”, Journal of Happiness Studies , Vol. 1 , pp. 1 - 21 .

Karatepe , O.M. , Rezapouraghdam , H. and Hassannia , R. ( 2020 ), “ Job insecurity, work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ non-green and nonattendance behaviors ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 87 , p. 102472 .

Kundi , M. , Ikramullah , M. , Iqbal , M.Z. and Ul-Hassan , F.S. ( 2018 ), “ Affective commitment as mechanism behind perceived career opportunity and turnover intentions with conditional effect of organizational prestige ”, Journal of Managerial Sciences , Vol. 1 .

Lee , Y. ( 2019 ), “ JD-R model on psychological wellbeing and the moderating effect of job discrimination in the model: findings from the MIDUS ”, European Journal of Training and Development , Vol. 43 No. 3/4 , pp. 232 - 249 .

Little , T.D. , Cunningham , W.A. , Shahar , G. and Widaman , K.F. ( 2002 ), “ To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits ”, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 151 - 173 .

Luu , T.T. ( 2019 ), “ Discretionary HR practices and employee well-being: the roles of job crafting and abusive supervision ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 43 - 66 .

Ma , B. , Liu , S. , Lassleben , H. and Ma , G. ( 2019 ), “ The relationships between job insecurity, psychological contract breach and counterproductive workplace behavior: does employment status matter? ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 48 No. 2 , pp. 595 - 610 .

Magnier-Watanabe , R. , Uchida , T. , Orsini , P. and Benton , C. ( 2017 ), “ Organizational virtuousness and job performance in Japan: does happiness matter? ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 25 No. 4 , pp. 628 - 646 .

Meyer , J.P. and Herscovitch , L. ( 2001 ), “ Commitment in the workplace: toward a general model ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 299 - 326 .

Meyer , J.P. , Allen , N.J. and Smith , C.A. ( 1993 ), “ Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 78 No. 4 , pp. 538 - 551 .

Mousa , M. , Massoud , H.K. and Ayoubi , R.M. ( 2020 ), “ Gender, diversity management perceptions, workplace happiness and organisational citizenship behaviour ”, Employee Relations: The International Journal , Vol. 1 .

Pan , S.-L. , Wu , H. , Morrison , A. , Huang , M.-T. and Huang , W.-S. ( 2018 ), “ The relationships among leisure involvement, organizational commitment and well-being: viewpoints from sport fans in Asia ”, Sustainability , Vol. 10 No. 3 , p. 740 .

Paul , H. , Bamel , U. , Ashta , A. and Stokes , P. ( 2019 ), “ Examining an integrative model of resilience, subjective well-being and commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviours ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 1274 - 1297 .

Piccoli , B. , Callea , A. , Urbini , F. , Chirumbolo , A. , Ingusci , E. and De Witte , H. ( 2017 ), “ Job insecurity and performance: the mediating role of organizational identification ”, Personnel Review , Vol. 46 No. 8 , pp. 1508 - 1522 .

Podsakoff , P.M. , MacKenzie , S.B. and Podsakoff , N.P. ( 2012 ), “ Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it ”, Annual Review of Psychology , Vol. 63 No. 1 , pp. 539 - 569 .

Qian , S. , Yuan , Q. , Niu , W. and Liu , Z. ( 2019 ), “ Is job insecurity always bad? The moderating role of job embeddedness in the relationship between job insecurity and job performance ”, Journal of Management and Organization , Vol. 1 , pp. 1 - 17 .

Rahmani , K. , Gnoth , J. and Mather , D. ( 2018 ), “ Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: a psycholinguistic view ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 69 , pp. 155 - 166 .

Ryan , R.M. and Deci , E.L. ( 2000 ), “ Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being ”, American Psychologist , Vol. 55 No. 1 , pp. 68 - 78 .

Ryff , C.D. ( 2018 ), “ Eudaimonic well-being: highlights from 25 years of inquiry ”, in Shigemasu , K. , Kuwano , S. , Sato , T. and Matsuzawa , T. (Eds), Diversity in Harmony – Inghts from Psychology: Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Psychology , John Wiley & Sons , pp. 375 - 395 .

Salgado , J.F. , Blanco , S. and Moscoso , S. ( 2019 ), “ Subjective well-being and job performance: Testing of a suppressor effect ”, Revista de Psicología Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones , Vol. 35 No. 2 , pp. 93 - 102 .

Sarwar , F. , Panatik , S.A. and Jameel , H.T. ( 2020 ), “ Does fear of terrorism influence psychological adjustment of academic sojourners in Pakistan? Role of state negative affect and emotional support ”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations , Vol. 75 , pp. 34 - 47 .

Schaumberg , R.L. and Flynn , F.J. ( 2017 ), “ Clarifying the link between job satisfaction and absenteeism: the role of guilt proneness ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 102 No. 6 , p. 982 .

Schoemmel , K. and Jønsson , T.S. ( 2014 ), “ Multiple affective commitments: quitting intentions and job performance ”, Employee Relations , Vol. 36 No. 5 , pp. 516 - 534 .

Schumacher , D. , Schreurs , B. , Van Emmerik , H. and De Witte , H. ( 2016 ), “ Explaining the relation between job insecurity and employee outcomes during organizational change: a multiple group comparison ”, Human Resource Management , Vol. 55 No. 5 , pp. 809 - 827 .

Semedo , A.S. , Coelho , A. and Ribeiro , N. ( 2019 ), “ Authentic leadership, happiness at work and affective commitment: an empirical study in Cape Verde ”, European Business Review , Vol. 31 No. 3 , pp. 337 - 351 .

Sharma , S. , Conduit , J. and Rao Hill , S. ( 2017 ), “ Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being outcomes from co-creation roles: a study of vulnerable customers ”, Journal of Services Marketing , Vol. 31 Nos 4/5 , pp. 397 - 411 .

Sharma , P. , Kong , T.T.C. and Kingshott , R.P.J. ( 2016 ), “ Internal service quality as a driver of employee satisfaction, commitment and performance: exploring the focal role of employee well-being ”, Journal of Service Management , Vol. 27 No. 5 , pp. 773 - 797 .

Sheldon , K.M. , Corcoran , M. and Prentice , M. ( 2018 ), “ Pursuing eudaimonic functioning versus pursuing hedonic well-being: the first goal succeeds in its aim, whereas the second does not ”, Journal of Happiness Studies , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 1 - 15 .

Shin , D. and Konrad , A.M. ( 2017 ), “ Causality between high-performance work systems and organizational performance ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 43 No. 4 , pp. 973 - 997 .

Shoss , M.K. ( 2017 ), “ Job insecurity: an integrative review and agenda for future research ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 43 No. 6 , pp. 1911 - 1939 .

Soomro , S.A. , Kundi , Y.M. and Kamran , M. ( 2020 ), “ Antecedents of workplace deviance: role of job insecurity, work stress, and ethical work climate ”, Problemy Zarzadzania , Vol. 17 No. 6 .

Staw , B.M. and Barsade , S.G. ( 1993 ), “ Affect and managerial perfornnance: a test of the sadder-but-Wiser hypotheses ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 38 No. 2 , pp. 304 - 331 .

Thoresen , C.J. , Kaplan , S.A. , Barsky , A.P. , Warren , C.R. and de Chermont , K. ( 2003 ), “ The affective underpinnings of job perceptions and attitudes ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 129 No. 6 , pp. 914 - 945 .

Tisu , L. , Lupșa , D. , Vîrgă , D. and Rusu , A. ( 2020 ), “ Personality characteristics, job performance and mental health the mediating role of work engagement ”, Personality and Individual Differences , Vol. 153 .

Turban , D.B. and Yan , W. ( 2016 ), “ Relationship of eudaimonia and hedonia with work outcomes ”, Journal of Managerial Psychology , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 1006 - 1020 .

Viswesvaran , C. and Ones , D.S. ( 2017 ), “ Job performance: assessment issues in personnel selection ”, The Blackwell Handbook of Personnel Selection , Blackwell London , pp. 354 - 375 .

Wang , J. and Wang , X. ( 2019 ), Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus , John Wiley and Sons New York, NY .

Wang , W. , Mather , K. and Seifert , R. ( 2018 ), “ Job insecurity, employee anxiety, and commitment: the moderating role of collective trust in management ”, Journal of Trust Research , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 220 - 237 .

Waterman , A.S. ( 1993 ), “ Two conceptions of happiness: contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment ”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , Vol. 64 No. 4 , p. 678 .

Waterman , A.S. , Schwartz , S.J. , Zamboanga , B.L. , Ravert , R.D. , Williams , M.K. , Bede Agocha , V. and Yeong Kim , S. ( 2010 ), “ The questionnaire for eudaimonic well-being: psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity ”, The Journal of Positive Psychology , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 41 - 61 .

Williams , L.J. and Anderson , S.E. ( 1991 ), “ Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 17 No. 3 , pp. 601 - 617 .

Williams , L.J. and O’Boyle , E.H. Jr ( 2008 ), “ Measurement models for linking latent variables and indicators: a review of human resource management research using parcels ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 18 No. 4 , pp. 233 - 242 .

Further reading

Sabella , A.R. , El-Far , M.T. and Eid , N.L. ( 2016 ), “ The effects of organizational and job characteristics on employees' organizational commitment in arts-and-culture organizations ”, International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 24 No. 5 , pp. 1002 - 1024 .

Acknowledgements

Funding and Support statement : The authors did not receive any external funding or additional support from third parties for this work.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Associations between medical students’ stress, academic burnout and moral courage efficacy

- Galit Neufeld-Kroszynski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9093-1308 1 na1 ,

- Keren Michael ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2662-6362 2 na1 &

- Orit Karnieli-Miller ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5790-0697 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 296 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

142 Accesses

Metrics details

Medical students, especially during the clinical years, are often exposed to breaches of safety and professionalism. These contradict personal and professional values exposing them to moral distress and to the dilemma of whether and how to act. Acting requires moral courage, i.e., overcoming fear to maintain one’s core values and professional obligations. It includes speaking up and “doing the right thing” despite stressors and risks (e.g., humiliation). Acting morally courageously is difficult, and ways to enhance it are needed. Though moral courage efficacy, i.e., individuals’ belief in their capability to act morally, might play a significant role, there is little empirical research on the factors contributing to students’ moral courage efficacy. Therefore, this study examined the associations between perceived stress, academic burnout, and moral courage efficacy.

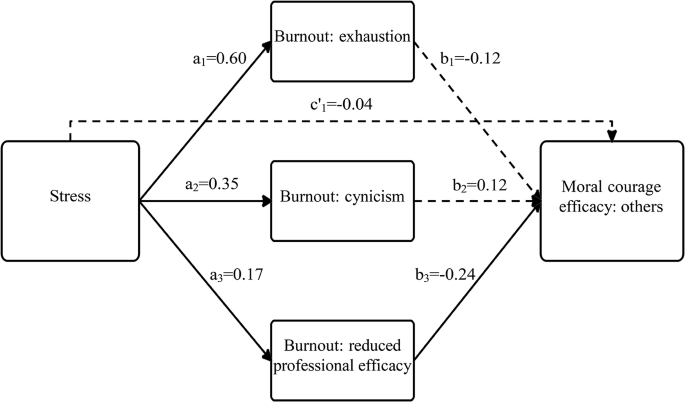

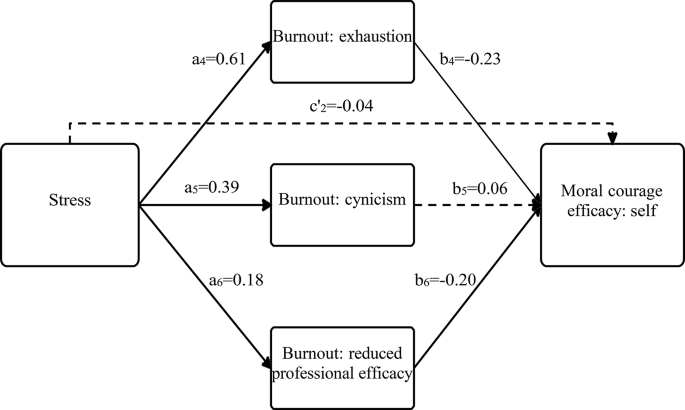

A cross-sectional study among 239 medical students who completed self-reported questionnaires measuring perceived stress, academic burnout (‘exhaustion,’ ‘cynicism,’ ‘reduced professional efficacy’), and moral courage efficacy (toward others’ actions and toward self-actions). Data analysis via Pearson’s correlations, regression-based PROCESS macro, and independent t -tests for group differences.

The burnout dimension of ‘reduced professional efficacy’ mediated the association between perceived stress and moral courage efficacy toward others’ actions. The burnout dimensions ‘exhaustion’ and ‘reduced professional efficacy’ mediated the association between perceived stress and moral courage efficacy toward self-actions.

Conclusions

The results emphasize the importance of promoting medical students’ well-being—in terms of stress and burnout—to enhance their moral courage efficacy. Medical education interventions should focus on improving medical students’ professional efficacy since it affects both their moral courage efficacy toward others and their self-actions. This can help create a safer and more appropriate medical culture.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In medical school, and especially during clinical years, medical students (MS) are often exposed to physicians’ inappropriate behaviors and various breaches of professionalism or safety [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. These can include lack of respect or sensitivity toward patients and other healthcare staff, deliberate lies and deceptions, breaching confidentiality, inadequate hand hygiene, or breach of a sterile field [ 4 , 5 ]. Furthermore, MS find themselves performing and/or participating in these inappropriate behaviors. For example, a study found that 80% of 3 rd– 4th year MS reported having done something they believed was unethical or having misled a patient [ 6 ]. Another study showed that 47.1–61.3% of females and 48.8–56.6% of male MS reported violating a patient’s dignity, participating in safety breaches, or examining/performing a procedure on a patient without valid consent, following a clinical teacher’s request, as a learning exercise [ 5 ]. These behaviors contradict professional values and MS’ own personal and moral values, exposing them to a dilemma in which they must choose if and how to act.

Taking action requires moral courage, i.e., taking an active stand or acting in the face of wrongdoing or moral injustice jeopardizing mental well-being [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Moral courage includes speaking up and “doing the right thing” despite risks, such as shame, retaliation, threat to reputation, or even loss of employment [ 8 ]. Moral courage is expressed in two main situations: when addressing others’ wrongdoing (e.g., identifying and disclosing a past/present medical error by colleagues/physicians); or when admitting one’s own wrongdoing (e.g., disclosing an error or lack of knowledge) [ 11 ].

Due to its “calling out” nature, acting on moral courage is difficult. A hierarchy and unsafe learning environment inhibits the ability for assertive expression of concern [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. This leads to concerning findings indicating that only 38% of MS reported that they would approach someone performing an unsafe behavior [ 12 ], and about half claimed that they would report an error they had observed [ 15 ].

Various reasons were suggested to explain why MS, interns, residents, or nurses, hesitate to act in a morally courageous way, including difficulty questioning the decisions or actions of those with more authority [ 12 ], and fear of negative social consequences, such as being disgraced, excluded, attacked, punished, or poorly evaluated [ 13 ]. Other reasons were the wish to fit into the team [ 6 ] and being a young professional experiencing “lack of knowledge” or “unfamiliarity” with clinical subtleties [ 16 ].

Nevertheless, failing to act on moral courage might lead to negative consequences, including moral distress [ 17 ]. Moral distress is a psychological disequilibrium that occurs when knowing the ethically right course of action but not acting upon it [ 18 ]. Moral distress is a known phenomenon among MS [ 19 ], e.g., 90% of MS at a New York City medical school reported moral distress when carrying for older patients [ 20 ]. MS’ moral distress was associated with thoughts of dropping out of medical school, choosing a nonclinical specialty, and increased burnout [ 20 ].

These consequences of moral distress and challenges to acting in a morally courageous way require further exploration of MS’ moral courage in general and their moral courage efficacy specifically. Bandura coined the term self-efficacy, focused on one’s perception of how well s/he can execute the action required to deal successfully with future situations and to achieve desired outcomes [ 21 ]. Self-efficacy plays a significant role in human behavior since individuals are more likely to engage in activities they believe they can handle [ 21 ]. Therefore, self-efficacy regarding a particular skill is a major motivating factor in the acquisition, development, and application of that skill [ 22 ]. For example, individuals’ perception regarding their ability to deal positively with ethical issues [ 23 ], their beliefs that they can handle effectively what is required to achieve moral performance [ 24 ], and to practically act as moral agents [ 25 ], can become a key psychological determinant of moral motivation and action [ 26 ]. Due to self-efficacy’s importance there is a need to learn about moral courage efficacy, i.e., individuals’ belief in their ability to exhibit moral courage through sharing their concerns regarding others and their own wrongdoing. Moral courage efficacy was suggested as important to moral courage in the field of business [ 27 ], but not empirically explored in medicine. Thus, there is no known prevalence of moral courage efficacy toward others and toward one’s own wrongdoing in medicine in general and for MS in particular. Furthermore, the potential contributing factors to moral courage efficacy, such as stress and burnout, require further exploration.

The associations between stress, burnout, and moral courage efficacy

Stress occurs when people view environmental demands as exceeding their ability to cope with them [ 28 ]. MS experience high levels of stress during their studies [ 29 ], due to excessive workload, time management difficulties, work–life balance conflicts, health concerns, and financial worries [ 30 ]. Studies show that high levels of stress were associated with decreased empathy [ 31 ], increased academic burnout, academic dishonesty, poor academic performance [ 32 ], and thoughts about dropping out of medical school [ 33 ]. As stress may impact one’s perceived efficacy [ 34 ], this study examined whether stress can inhibit individuals’ moral courage efficacy to address others’ and their own wrongdoing.

An aspect related to a poor mental state that may mediate the association between stress and MS’ moral courage efficacy is burnout. Burnout includes emotional exhaustion, cynicism toward one’s occupation value, and doubting performance ability [ 35 ]. Burnout is usually work-related and is common in the helping professions [ 60 ]. For students, this concept relates to academic burnout [ 36 ], which includes exhaustion due to study demands, a cynical and detached attitude to studying, and low/reduced professional efficacy, i.e. feeling incompetent as learners [ 37 ].

Burnout has various negative implications for MS’ well-being and professional development. Burnout is associated with psychiatric disorders and thoughts of dropping out of medical school [ 33 ]. Furthermore, MS’ burnout is associated with increased involvement in unprofessional behavior, eroding professional development, diminishing qualities such as honesty, integrity, altruism, and self-regulation [ 38 ], reducing empathy [ 31 , 39 ] and unwillingness to provide care for the medically underserved [ 40 ]. Thus, burnout may also impact MS’ views on their responsibility and perceived ability to promote high-quality care and advocate for patients [ 41 ], possibly leading them to feel reluctant and incapable to act with moral courage [ 42 ]. Earlier studies exploring stress and its various outcomes, found that burnout, and specifically exhaustion, can become a crucial mediator for various harmful outcomes [ 43 ]. Although stress is impactful to creating discomfort, the decision and ability to intervene requires one’s own drive and power. When one is feeling stress, leading to burnout their depleted energy reserves and diminished sense of professional worth likely undermine their perceived power (due to exhaustion) or will (due to cynicism) to uphold professional ethical standards and intervene to advocate for patient care in challenging circumstances, such as the need to speak up in front of authority members. Furthermore, burnout may facilitate a cognitive distancing from professional values and responsibilities, allowing for moral disengagement and reducing the likelihood of morally courageous actions. This mediation role requires further exploration.

This study examined associations between perceived stress, academic burnout, and moral courage efficacy. In addition to the mere associations among the variables, it will be examined whether there is a mediation effect (perceived stress → academic burnout → moral courage efficacy) to gain more insight into possible mechanisms of the development of moral courage efficacy and of protective factors. Understanding these mechanisms has educational benefit for guiding interventions to enhance MS’ moral courage efficacy.

H1: Perceived stress and academic burnout dimensions will be negatively associated with moral courage efficacy dimensions.

H2: Perceived stress will be positively associated with academic burnout dimensions.

H3: Academic burnout dimensions will mediate the association between perceived stress and moral courage efficacy dimensions.

Materials and methods

Sample and procedure.

A quantitative cross-sectional study among 239 MS. Most participants were female (60%), aged 29 or less (90%), and unmarried (75%). About two thirds (64.3%) were at the pre-clinical stage of medical school and about a third (35.7%) at the clinical stage. In December 2019, the research team approached MS through email and social media to participate in the study and complete an online questionnaire. This was a part of a national study focused on MS’ burnout [ 44 ]. The 239 participants were recruited by a convenience sampling. Data were collected online through Qualtrics platform, via anonymous self-reported questionnaires. The University Ethics Committee approved the study, and all participants signed an informed consent form.

Moral courage efficacy —This 8-item instrument, developed for this study, is based on the literature on moral courage, professionalism, and speaking-up, including qualitative and quantitative studies [ 7 , 13 , 45 , 46 , 47 ], and discussions with MS and medical educators. The main developing team included a Ph.D. medical educator expert in communication in healthcare and professionalism; an M.D. psychiatrist expert in decision making, professionalism, and philosophy; a Ph.D. graduate who analyzed MS’ narratives focused on moral dilemmas and moral courage during professionalism breaches; and a Ph.D. candidate focused on assertiveness in medicine [ 14 ]. This allowed the identification of different types of situations MS face that may require moral courage.

As guided by instructions for measuring self-efficacy, which encourage using specific statements that relate to the specific situation and skill required [ 48 ], the instrument measures MS’ perception of their own ability, i.e., self-efficacy, to act based on their moral beliefs when exposed to safety and professionalism breaches or challenges. Due to our qualitative findings indicating that students change their interpretation of the problematic event based on their decision to act in a morally courageous way and that some are exposed to specific professionalism violations while others are not when designing the questionnaire, we decided to make the cases not explicit to specific types of professionalism breaches – e.g., not focused on talking above a patient’s head [ 1 ], but rather general the type of behavior e.g., “behaves immorally”. This decreases the personal interpretation if one behavior is acceptable by this individual; and also decreases the possibility of not answering the question if the individual student has never seen that specific behavior. Furthermore, to avoid “gray areas” in moral issues, we wrote the statements in a manner where there is no doubt whether there is a moral problem (“problematic situation”) [ 47 ], and thus the focus was only on one’s feeling of being capable of speaking up about their concern, i.e., act in a moral courage efficacy (see Table 1 ).

The instrument’s initial development consisted of 14 items addressing various populations, including senior MDs. The 14-item tool included questions regarding the willingness to recommend a second opinion or to convey one’s medical mistake to patients and their families. These actions are less relevant to MS. Thus, we extracted the questionnaire to a parsimonious instrument of 8 items.

The 8 items were divided into two dimensions: others and the self. This division is supported by the literature on moral courage that distinguishes between courage regarding others- vs. self-behavior. Hence, the questionnaire was designed to assess one’s perceived ability to act/speak up in these two dimensions: (a) situations of moral courage efficacy relating to others’ behavior (e.g., “ capable of telling a senior physician if I have detected a mistake s/he might have made ”); (b) situations of moral courage efficacy relating to self (e.g., “ capable of disclosing my mistakes to a senior physician ”). This two-dimension division is important and was absent in former measurements of moral courage. It was also replicated in another study we conducted among MS [ 49 ]. Furthermore, factor analysis with Oblimin rotation supported this two-factor structure (Table 1 ). All items had a high factor loading on the relevant factor (it should be mentioned that item 4 was loaded 0.59 on the relevant factor and 0.32 on the non-relevant factor).

All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = to a small extent; 4 = to a very great extent) and are calculated by averaging the answers on the dimension, with higher scores representing higher moral courage efficacy. Internal reliability was α = 0.80 for the “others” dimension and α = 0.84 for the “self” dimension.

Perceived stress —This single-item questionnaire (“How would you rate the level of stress you’ve been experiencing in the last few days?” ) evaluates MS’ perceived stress currently in their life on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = no stress; 10 = extreme stress), with higher scores representing higher perceived stress. It is based on a similar question evaluating MS’ perceived emotional stress [ 29 ]. Even though a multi-item measure might be more stable, previous studies indicated that using a single item is a practical, reliable alternative, with high construct validity in the context of felt/perceived stress, self-esteem, health status, etc [ 43 , 50 , 51 ].

Academic burnout —This 15-item instrument is a translated version [ 44 ] of the MBI-SS (MBI–Student Survey) [ 37 ], a common instrument used to measure burnout in the academic context, e.g. MS [ 52 , 53 ]. It measures students’ feelings of burnout regarding their studies on three dimensions: (a) ‘exhaustion’ (5 items; e.g., “ Studying or attending a class is a real strain for me ”), (b) ‘cynicism’ (4 items; e.g., “ I doubt the significance of my studies ”), (c) lack of personal academic efficacy (‘reduced professional efficacy’) (6 items; “ I feel [un]stimulated when I achieve my study goals ”). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = never; 6 = always) and is calculated by summing the answers on the dimension (after re-coding all professional efficacy items), with higher scores representing more frequent feelings of burnout. Internal reliability was α = 0.80 for ‘exhaustion’, α = 0.80 for ‘cynicism’, and α = 0.84 for ‘reduced professional efficacy’.

Statistical analyses

IBM-SPSS (version 25) was used to analyze the data. Pearson’s correlations examined all possible bivariate associations between the study variables. PROCESS macro examined the mediation effects (via model#4). The significance of the mediation effects was examined by calculating 5,000 samples to estimate the 95% percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) of indirect effects of the predictor on the outcome through the mediator [ 54 ]. T -tests for independent samples examined differences between the study variables in the pre-clinic and clinic stages. The defined significance level was set generally to 5% ( p < 0.05).

This study focused on understanding moral courage efficacy, i.e., MS’ perceived ability to speak up and act while exposed to others’ and their own wrongdoing. The sample’s frequencies demonstrate that only 10% of the MS reported that their moral courage efficacy toward the others was “very high to high,” and 54% reported this toward the self. Mean scores demonstrate that regarding the others, MS showed relatively low/moderate levels of moral courage and higher levels regarding the self. As for the variables tested to be associated with moral courage efficacy, MS showed relatively high perceived stress and low-to-moderate academic burnout (see Table 2 for the variables’ psychometric characteristics).

Table 2 also shows the correlations among the study variables. According to Cohen’s (1988) [ 55 ] interpretation of the strength in bivariate associations (Pearson correlation), the effect size is low when r value varies around 0.1, medium when it is around 0.3, and large when it is more than 0.5. Hence, regarding the associations between the two dimensions of moral courage efficacy: we found a moderate positive correlation between the efficacy toward others and the efficacy toward the self. Regarding the associations among the three academic burnout dimensions: we found a strong positive correlation between ‘exhaustion’ and ‘cynicism,’ a weak positive correlation between ‘exhaustion’ and ‘reduced professional efficacy,’ and a moderate positive correlation between ‘cynicism,’ and ‘reduced professional efficacy.’

As for the associations concerning H1, Table 2 indicates that one academic burnout dimension, i.e., ‘reduced professional efficacy,’ had a weak negative correlation with moral courage efficacy toward the others, thus high burnout was associated with lower perceived moral courage efficacy toward others. Additionally, perceived stress and all three burnout dimensions had weak negative correlations with moral courage efficacy toward the self—partially supporting H1.

As for the associations concerning H2, Table 2 indicates that perceived stress had a strong positive correlation with ‘exhaustion,’ a moderate positive correlation with ‘cynicism,’ and a weak positive correlation with ‘reduced professional efficacy’—supporting H2.