An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Bentham Open Access

Internet Addiction: A Brief Summary of Research and Practice

Hilarie cash.

a reSTART Internet Addiction Recovery Program, Fall City, WA 98024

Cosette D Rae

Ann h steel, alexander winkler.

b University of Marburg, Department for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Gutenbergstraße 18, 35032 Marburg, Germany

Problematic computer use is a growing social issue which is being debated worldwide. Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) ruins lives by causing neurological complications, psychological disturbances, and social problems. Surveys in the United States and Europe have indicated alarming prevalence rates between 1.5 and 8.2% [1]. There are several reviews addressing the definition, classification, assessment, epidemiology, and co-morbidity of IAD [2-5], and some reviews [6-8] addressing the treatment of IAD. The aim of this paper is to give a preferably brief overview of research on IAD and theoretical considerations from a practical perspective based on years of daily work with clients suffering from Internet addiction. Furthermore, with this paper we intend to bring in practical experience in the debate about the eventual inclusion of IAD in the next version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

INTRODUCTION

The idea that problematic computer use meets criteria for an addiction, and therefore should be included in the next iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) , 4 th ed. Text Revision [ 9 ] was first proposed by Kimberly Young, PhD in her seminal 1996 paper [ 10 ]. Since that time IAD has been extensively studied and is indeed, currently under consideration for inclusion in the DSM-V [ 11 ]. Meanwhile, both China and South Korea have identified Internet addiction as a significant public health threat and both countries support education, research and treatment [ 12 ]. In the United States, despite a growing body of research, and treatment for the disorder available in out-patient and in-patient settings, there has been no formal governmental response to the issue of Internet addiction. While the debate goes on about whether or not the DSM-V should designate Internet addiction a mental disorder [ 12 - 14 ] people currently suffering from Internet addiction are seeking treatment. Because of our experience we support the development of uniform diagnostic criteria and the inclusion of IAD in the DSM-V [ 11 ] in order to advance public education, diagnosis and treatment of this important disorder.

CLASSIFICATION

There is ongoing debate about how best to classify the behavior which is characterized by many hours spent in non-work technology-related computer/Internet/video game activities [ 15 ]. It is accompanied by changes in mood, preoccupation with the Internet and digital media, the inability to control the amount of time spent interfacing with digital technology, the need for more time or a new game to achieve a desired mood, withdrawal symptoms when not engaged, and a continuation of the behavior despite family conflict, a diminishing social life and adverse work or academic consequences [ 2 , 16 , 17 ]. Some researchers and mental health practitioners see excessive Internet use as a symptom of another disorder such as anxiety or depression rather than a separate entity [e.g. 18]. Internet addiction could be considered an Impulse control disorder (not otherwise specified). Yet there is a growing consensus that this constellation of symptoms is an addiction [e.g. 19]. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recently released a new definition of addiction as a chronic brain disorder, officially proposing for the first time that addiction is not limited to substance use [ 20 ]. All addictions, whether chemical or behavioral, share certain characteristics including salience, compulsive use (loss of control), mood modification and the alleviation of distress, tolerance and withdrawal, and the continuation despite negative consequences.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR IAD

The first serious proposal for diagnostic criteria was advanced in 1996 by Dr. Young, modifying the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling [ 10 ]. Since then variations in both name and criteria have been put forward to capture the problem, which is now most popularly known as Internet Addiction Disorder. Problematic Internet Use (PIU) [ 21 ], computer addiction, Internet dependence [ 22 ], compulsive Internet use, pathological Internet use [ 23 ], and many other labels can be found in the literature. Likewise a variety of often overlapping criteria have been proposed and studied, some of which have been validated. However, empirical studies provide an inconsistent set of criteria to define Internet addiction [ 24 ]. For an overview see Byun et al . [ 25 ].

Beard [ 2 ] recommends that the following five diagnostic criteria are required for a diagnosis of Internet addiction: (1) Is preoccupied with the Internet (thinks about previous online activity or anticipate next online session); (2) Needs to use the Internet with increased amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction; (3) Has made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet use; (4) Is restless, moody, depressed, or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop Internet use; (5) Has stayed online longer than originally intended. Additionally, at least one of the following must be present: (6) Has jeopardized or risked the loss of a significant relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet; (7) Has lied to family members, therapist, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the Internet; (8) Uses the Internet as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness, guilt, anxiety, depression) [ 2 ].

There has been also been a variety of assessment tools used in evaluation. Young’s Internet Addiction Test [ 16 ], the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ) developed by Demetrovics, Szeredi, and Pozsa [ 26 ] and the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) [ 27 ] are all examples of instruments to assess for this disorder.

The considerable variance of the prevalence rates reported for IAD (between 0.3% and 38%) [ 28 ] may be attributable to the fact that diagnostic criteria and assessment questionnaires used for diagnosis vary between countries and studies often use highly selective samples of online surveys [ 7 ]. In their review Weinstein and Lejoyeux [ 1 ] report that surveys in the United States and Europe have indicated prevalence rates varying between 1.5% and 8.2%. Other reports place the rates between 6% and 18.5% [ 29 ].

“Some obvious differences with respect to the methodologies, cultural factors, outcomes and assessment tools forming the basis for these prevalence rates notwithstanding, the rates we encountered were generally high and sometimes alarming.” [ 24 ]

There are different models available for the development and maintenance of IAD like the cognitive-behavioral model of problematic Internet use [ 21 ], the anonymity, convenience and escape (ACE) model [ 30 ], the access, affordability, anonymity (Triple-A) engine [ 31 ], a phases model of pathological Internet use by Grohol [ 32 ], and a comprehensive model of the development and maintenance of Internet addiction by Winkler & Dörsing [ 24 ], which takes into account socio-cultural factors ( e.g. , demographic factors, access to and acceptance of the Internet), biological vulnerabilities ( e.g. , genetic factors, abnormalities in neurochemical processes), psychological predispositions ( e.g. , personality characteristics, negative affects), and specific attributes of the Internet to explain “excessive engagement in Internet activities” [ 24 ].

NEUROBIOLOGICAL VULNERABILITIES

It is known that addictions activate a combination of sites in the brain associated with pleasure, known together as the “reward center” or “pleasure pathway” of the brain [ 33 , 34 ]. When activated, dopamine release is increased, along with opiates and other neurochemicals. Over time, the associated receptors may be affected, producing tolerance or the need for increasing stimulation of the reward center to produce a “high” and the subsequent characteristic behavior patterns needed to avoid withdrawal. Internet use may also lead specifically to dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens [ 35 , 36 ], one of the reward structures of the brain specifically involved in other addictions [ 20 ]. An example of the rewarding nature of digital technology use may be captured in the following statement by a 21 year-old male in treatment for IAD:

“I feel technology has brought so much joy into my life. No other activity relaxes me or stimulates me like technology. However, when depression hits, I tend to use technology as a way of retreating and isolating.”

REINFORCEMENT/REWARD

What is so rewarding about Internet and video game use that it could become an addiction? The theory is that digital technology users experience multiple layers of reward when they use various computer applications. The Internet functions on a variable ratio reinforcement schedule (VRRS), as does gambling [ 29 ]. Whatever the application (general surfing, pornography, chat rooms, message boards, social networking sites, video games, email, texting, cloud applications and games, etc.), these activities support unpredictable and variable reward structures. The reward experienced is intensified when combined with mood enhancing/stimulating content. Examples of this would be pornography (sexual stimulation), video games (e.g. various social rewards, identification with a hero, immersive graphics), dating sites (romantic fantasy), online poker (financial) and special interest chat rooms or message boards (sense of belonging) [ 29 , 37 ].

BIOLOGICAL PREDISPOSITION

There is increasing evidence that there can be a genetic predisposition to addictive behaviors [ 38 , 39 ]. The theory is that individuals with this predisposition do not have an adequate number of dopamine receptors or have an insufficient amount of serotonin/dopamine [ 2 ], thereby having difficulty experiencing normal levels of pleasure in activities that most people would find rewarding. To increase pleasure, these individuals are more likely to seek greater than average engagement in behaviors that stimulate an increase in dopamine, effectively giving them more reward but placing them at higher risk for addiction.

MENTAL HEALTH VULNERABILITIES

Many researchers and clinicians have noted that a variety of mental disorders co-occur with IAD. There is debate about which came first, the addiction or the co-occurring disorder [ 18 , 40 ]. The study by Dong et al . [ 40 ] had at least the potential to clarify this question, reporting that higher scores for depression, anxiety, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, and psychoticism were consequences of IAD. But due to the limitations of the study further research is necessary.

THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET ADDICTION

There is a general consensus that total abstinence from the Internet should not be the goal of the interventions and that instead, an abstinence from problematic applications and a controlled and balanced Internet usage should be achieved [ 6 ]. The following paragraphs illustrate the various treatment options for IAD that exist today. Unless studies examining the efficacy of the illustrated treatments are not available, findings on the efficacy of the presented treatments are also provided. Unfortunately, most of the treatment studies were of low methodological quality and used an intra-group design.

The general lack of treatment studies notwithstanding, there are treatment guidelines reported by clinicians working in the field of IAD. In her book “Internet Addiction: Symptoms, Evaluation, and Treatment”, Young [ 41 ] offers some treatment strategies which are already known from the cognitive-behavioral approach: (a) practice opposite time of Internet use (discover patient’s patterns of Internet use and disrupt these patterns by suggesting new schedules), (b) use external stoppers (real events or activities prompting the patient to log off), (c) set goals (with regard to the amount of time), (d) abstain from a particular application (that the client is unable to control), (e) use reminder cards (cues that remind the patient of the costs of IAD and benefits of breaking it), (f) develop a personal inventory (shows all the activities that the patient used to engage in or can’t find the time due to IAD), (g) enter a support group (compensates for a lack of social support), and (h) engage in family therapy (addresses relational problems in the family) [ 41 ]. Unfortunately, clinical evidence for the efficacy of these strategies is not mentioned.

Non-psychological Approaches

Some authors examine pharmacological interventions for IAD, perhaps due to the fact that clinicians use psychopharmacology to treat IAD despite the lack of treatment studies addressing the efficacy of pharmacological treatments. In particular, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used because of the co-morbid psychiatric symptoms of IAD (e.g. depression and anxiety) for which SSRIs have been found to be effective [ 42 - 46 ]. Escitalopram (a SSRI) was used by Dell’Osso et al . [ 47 ] to treat 14 subjects with impulsive-compulsive Internet usage disorder. Internet usage decreased significantly from a mean of 36.8 hours/week to a baseline of 16.5 hours/week. In another study Han, Hwang, and Renshaw [ 48 ] used bupropion (a non-tricyclic antidepressant) and found a decrease of craving for Internet video game play, total game play time, and cue-induced brain activity in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after a six week period of bupropion sustained release treatment. Methylphenidate (a psycho stimulant drug) was used by Han et al . [ 49 ] to treat 62 Internet video game-playing children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. After eight weeks of treatment, the YIAS-K scores and Internet usage times were significantly reduced and the authors cautiously suggest that methylphenidate might be evaluated as a potential treatment of IAD. According to a study by Shapira et al . [ 50 ], mood stabilizers might also improve the symptoms of IAD. In addition to these studies, there are some case reports of patients treated with escitalopram [ 45 ], citalopram (SSRI)- quetiapine (antipsychotic) combination [ 43 ] and naltrexone (an opioid receptor antagonist) [ 51 ].

A few authors mentioned that physical exercise could compensate the decrease of the dopamine level due to decreased online usage [ 52 ]. In addition, sports exercise prescriptions used in the course of cognitive behavioral group therapy may enhance the effect of the intervention for IAD [ 53 ].

Psychological Approaches

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a client-centered yet directive method for enhancing intrinsic motivation to change by exploring and resolving client ambivalence [ 54 ]. It was developed to help individuals give up addictive behaviors and learn new behavioral skills, using techniques such as open-ended questions, reflective listening, affirmation, and summarization to help individuals express their concerns about change [ 55 ]. Unfortunately, there are currently no studies addressing the efficacy of MI in treating IAD, but MI seems to be moderately effective in the areas of alcohol, drug addiction, and diet/exercise problems [ 56 ].

Peukert et al . [ 7 ] suggest that interventions with family members or other relatives like “Community Reinforcement and Family Training” [ 57 ] could be useful in enhancing the motivation of an addict to cut back on Internet use, although the reviewers remark that control studies with relatives do not exist to date.

Reality therapy (RT) is supposed to encourage individuals to choose to improve their lives by committing to change their behavior. It includes sessions to show clients that addiction is a choice and to give them training in time management; it also introduces alternative activities to the problematic behavior [ 58 ]. According to Kim [ 58 ], RT is a core addiction recovery tool that offers a wide variety of uses as a treatment for addictive disorders such as drugs, sex, food, and works as well for the Internet. In his RT group counseling program treatment study, Kim [ 59 ] found that the treatment program effectively reduced addiction level and improved self-esteem of 25 Internet-addicted university students in Korea.

Twohig and Crosby [ 60 ] used an Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) protocol including several exercises adjusted to better fit the issues with which the sample struggles to treat six adult males suffering from problematic Internet pornography viewing. The treatment resulted in an 85% reduction in viewing at post-treatment with results being maintained at the three month follow-up (83% reduction in viewing pornography).

Widyanto and Griffith [ 8 ] report that most of the treatments employed so far had utilized a cognitive-behavioral approach. The case for using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is justified due to the good results in the treatment of other behavioral addictions/impulse-control disorders, such as pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating-disorders [ 61 ]. Wölfling [ 5 ] described a predominantly behavioral group treatment including identification of sustaining conditions, establishing of intrinsic motivation to reduce the amount of time being online, learning alternative behaviors, engagement in new social real-life contacts, psycho-education and exposure therapy, but unfortunately clinical evidence for the efficacy of these strategies is not mentioned. In her study, Young [ 62 ] used CBT to treat 114 clients suffering from IAD and found that participants were better able to manage their presenting problems post-treatment, showing improved motivation to stop abusing the Internet, improved ability to control their computer use, improved ability to function in offline relationships, improved ability to abstain from sexually explicit online material, improved ability to engage in offline activities, and improved ability to achieve sobriety from problematic applications. Cao, Su and Gao [ 63 ] investigated the effect of group CBT on 29 middle school students with IAD and found that IAD scores of the experimental group were lower than of the control group after treatment. The authors also reported improvement in psychological function. Thirty-eight adolescents with IAD were treated with CBT designed particularly for addicted adolescents by Li and Dai [ 64 ]. They found that CBT has good effects on the adolescents with IAD (CIAS scores in the therapy group were significant lower than that in the control group). In the experimental group the scores of depression, anxiety, compulsiveness, self-blame, illusion, and retreat were significantly decreased after treatment. Zhu, Jin, and Zhong [ 65 ] compared CBT and electro acupuncture (EA) plus CBT assigning forty-seven patients with IAD to one of the two groups respectively. The authors found that CBT alone or combined with EA can significantly reduce the score of IAD and anxiety on a self-rating scale and improve self-conscious health status in patients with IAD, but the effect obtained by the combined therapy was better.

Multimodal Treatments

A multimodal treatment approach is characterized by the implementation of several different types of treatment in some cases even from different disciplines such as pharmacology, psychotherapy and family counseling simultaneously or sequentially. Orzack and Orzack [ 66 ] mentioned that treatments for IAD need to be multidisciplinary including CBT, psychotropic medication, family therapy, and case managers, because of the complexity of these patients’ problems.

In their treatment study, Du, Jiang, and Vance [ 67 ] found that multimodal school-based group CBT (including parent training, teacher education, and group CBT) was effective for adolescents with IAD (n = 23), particularly in improving emotional state and regulation ability, behavioral and self-management style. The effect of another multimodal intervention consisting of solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT), family therapy, and CT was investigated among 52 adolescents with IAD in China. After three months of treatment, the scores on an IAD scale (IAD-DQ), the scores on the SCL-90, and the amount of time spent online decreased significantly [ 68 ]. Orzack et al . [ 69 ] used a psychoeducational program, which combines psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral theoretical perspectives, using a combination of Readiness to Change (RtC), CBT and MI interventions to treat a group of 35 men involved in problematic Internet-enabled sexual behavior (IESB). In this group treatment, the quality of life increased and the level of depressive symptoms decreased after 16 (weekly) treatment sessions, but the level of problematic Internet use failed to decrease significantly [ 69 ]. Internet addiction related symptom scores significantly decreased after a group of 23 middle school students with IAD were treated with Behavioral Therapy (BT) or CT, detoxification treatment, psychosocial rehabilitation, personality modeling and parent training [ 70 ]. Therefore, the authors concluded that psychotherapy, in particular CT and BT were effective in treating middle school students with IAD. Shek, Tang, and Lo [ 71 ] described a multi-level counseling program designed for young people with IAD based on the responses of 59 clients. Findings of this study suggest this multi-level counseling program (including counseling, MI, family perspective, case work and group work) is promising to help young people with IAD. Internet addiction symptom scores significantly decreased, but the program failed to increase psychological well-being significantly. A six-week group counseling program (including CBT, social competence training, training of self-control strategies and training of communication skills) was shown to be effective on 24 Internet-addicted college students in China [ 72 ]. The authors reported that the adapted CIAS-R scores of the experimental group were significantly lower than those of the control group post-treatment.

The reSTART Program

The authors of this article are currently, or have been, affiliated with the reSTART: Internet Addiction Recovery Program [ 73 ] in Fall City, Washington. The reSTART program is an inpatient Internet addiction recovery program which integrates technology detoxification (no technology for 45 to 90 days), drug and alcohol treatment, 12 step work, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), experiential adventure based therapy, Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT), brain enhancing interventions, animal assisted therapy, motivational interviewing (MI), mindfulness based relapse prevention (MBRP), Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR), interpersonal group psychotherapy, individual psychotherapy, individualized treatments for co-occurring disorders, psycho- educational groups (life visioning, addiction education, communication and assertiveness training, social skills, life skills, Life balance plan), aftercare treatments (monitoring of technology use, ongoing psychotherapy and group work), and continuing care (outpatient treatment) in an individualized, holistic approach.

The first results from an ongoing OQ45.2 [ 74 ] study (a self-reported measurement of subjective discomfort, interpersonal relationships and social role performance assessed on a weekly basis) of the short-term impact on 19 adults who complete the 45+ days program showed an improved score after treatment. Seventy-four percent of participants showed significant clinical improvement, 21% of participants showed no reliable change, and 5% deteriorated. The results have to be regarded as preliminary due to the small study sample, the self-report measurement and the lack of a control group. Despite these limitations, there is evidence that the program is responsible for most of the improvements demonstrated.

As can be seen from this brief review, the field of Internet addiction is advancing rapidly even without its official recognition as a separate and distinct behavioral addiction and with continuing disagreement over diagnostic criteria. The ongoing debate whether IAD should be classified as an (behavioral) addiction, an impulse-control disorder or even an obsessive compulsive disorder cannot be satisfactorily resolved in this paper. But the symptoms we observed in clinical practice show a great deal of overlap with the symptoms commonly associated with (behavioral) addictions. Also it remains unclear to this day whether the underlying mechanisms responsible for the addictive behavior are the same in different types of IAD (e.g., online sexual addiction, online gaming, and excessive surfing). From our practical perspective the different shapes of IAD fit in one category, due to various Internet specific commonalities (e.g., anonymity, riskless interaction), commonalities in the underlying behavior (e.g., avoidance, fear, pleasure, entertainment) and overlapping symptoms (e.g., the increased amount of time spent online, preoccupation and other signs of addiction). Nevertheless more research has to be done to substantiate our clinical impression.

Despite several methodological limitations, the strength of this work in comparison to other reviews in the international body of literature addressing the definition, classification, assessment, epidemiology, and co-morbidity of IAD [ 2 - 5 ], and to reviews [ 6 - 8 ] addressing the treatment of IAD, is that it connects theoretical considerations with the clinical practice of interdisciplinary mental health experts working for years in the field of Internet addiction. Furthermore, the current work gives a good overview of the current state of research in the field of internet addiction treatment. Despite the limitations stated above this work gives a brief overview of the current state of research on IAD from a practical perspective and can therefore be seen as an important and helpful paper for further research as well as for clinical practice in particular.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Internet addiction and related clinical problems: a study on italian young adults.

- 1 Department of Neurosciences, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

- 2 Unit of Addiction Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Integrated University Hospital of Verona, Policlinico “G.B. Rossi”, Verona, Italy

- 3 Department of Medical Sciences and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy

- 4 Amici C.A.S.A. San Simone No Profit Association, Mantova, Italy

The considerable prominence of internet addiction (IA) in adolescence is at least partly explained by the limited knowledge thus far available on this complex phenomenon. In discussing IA, it is necessary to be aware that this is a construct for which there is still no clear definition in the literature. Nonetheless, its important clinical implications, as emerging in recent years, justify the lively interest of researchers in this new form of behavioral addiction. Over the years, studies have associated IA with numerous clinical problems. However, fewer studies have investigated what factors might mediate the relationship between IA and the different problems associated with it. Ours is one such study. The Italian version of the SCL-90 and the IAT were administered to a sample of almost 800 adolescents aged between 16 and 22 years. We found the presence of a significant association between IA and two variables: somatization (β = 7.80; p < 0.001) and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (β = 2.18; p < 0.05). In line with our hypothesis, the results showed that somatization predicted the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA (β = −2.75; t = −3.55; p < 0.001), explaining 24.5% of its variance (Δ R 2 = 1.2%; F = 12.78; p < 0.01). In addition, simple slopes analyses revealed that, on reaching clinical significance (+1 SD), somatization showed higher moderation effects in the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA (β = 6.13; t = 7.83; p < 0.001). These results appear to be of great interest due to the absence of similar evidence in the literature, and may open the way for further research in the IA field. Although the absence of studies in the literature does not allow us to offer an exhaustive explanation of these results, our study supports current addiction theories which emphasize the important function performed by the enteroceptive system, alongside the more cited reflexive and impulsive systems.

Introduction

Internet addiction (IA), also referred to as problematic , pathological , or compulsive Internet use , is a controversial concept in the research field. The frequent use of different terms to describe this new phenomenon, linked to the advent and growth of the Internet, leads to confusion over what it really consists of Tereshchenko and Kasparov (2019) .

Although researchers have yet to find a common definition of IA, it can be considered a “ non-chemical, behavioral addiction, which involves human-machine interaction ” ( Griffiths, 2000 ). Useful clinical criteria were proposed by Block (2008) , who associates IA with (a) increased feelings of anger, anxiety or sadness when the Internet is not accessible (craving); (b) the need to spend more hours on Internet devices in order to feel pleasure or cope with dysregulation of mood (tolerance); (c) poor school performance or vocational achievement; and (d) isolation or social withdrawal.

One aspect that researchers agree on is the importance of IA prevention in children and adolescents ( Lan and Lee, 2013 ). As with other forms of addiction, younger people are at greater risk of the negative effects of out-of-control Internet use ( Ko et al., 2008 ). In adolescence, distress is expressed in the form of behavioral agitation, somatic symptoms, boredom and an inclination to act ( Carlson, 2000 ), all modalities that facilitate the development of a coping strategy based on compulsive Internet use. This is a problem, given that 80% of adolescents use tablets or smartphones ( Fox and Duggan, 2013 ), whereas general population prevalence rates range from 0.8% (Italy) to 26.5% (Hong Kong) ( Kuss et al., 2014 ).

We currently know that IA is associated with symptoms of ADHD in teens ( Yoo et al., 2004 ), pathological gambling ( Phillips et al., 2012 ), depression ( Andreou and Svoli, 2013 ; Ho et al., 2014 ), anxiety ( Griffiths and Meredith, 2009 ; Zboralski et al., 2009 ), social phobia ( Carli et al., 2013 ; Gonzalez-Bueso et al., 2018 ), experiential avoidance ( Hayes et al., 1996 ; García-Oliva and Piqueras, 2016 ), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) ( Jang et al., 2008 ; Cecilia et al., 2013 ), eating disorders ( Shapira et al., 2003 ; Bernardi and Pallanti, 2009 ), and sleep disorders ( Nuutinen et al., 2014 ; Tamura et al., 2017 ), as well as with relational conflicts ( Gundogar et al., 2012 ), aggression ( Cecilia et al., 2013 ), self-destructive behaviors ( Sasmaz et al., 2014 ), suicidal behaviors ( Durkee et al., 2016 ), physical health problems ( Sung et al., 2013 ), and chronic pain syndrome ( Wei et al., 2012 ). However, little is known about the factors potentially implicated in the etiopathogenesis of IA ( Tereshchenko and Kasparov, 2019 ).

Many of the most common symptoms of addiction and OCD are similar to each other, to the point that some authors define IA as compulsive computer use ( Kuss et al., 2014 ). However, there are also significant differences between the two sets of psychopathological symptoms. The obsessive-compulsive symptoms that characterize OCD can be described as recurring and persistent inappropriate thoughts (obsessions) that lead the individual to implement behaviors (compulsions) aimed at reducing the intensity of the distress deriving from these obsessive thoughts ( American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ). Instead, the obsessive-compulsive symptoms reported in the context of addiction can also derive from positive thoughts about the object of the addiction, which drive the individual to seek and, in this case, engage in the activity in order to obtain gratification ( Robbins and Clark, 2015 ).

In this framework, the obsessive-compulsive component of IA can be considered in terms of (a) recurrent positive and negative thoughts (obsessions), associated, respectively, with the memory of the enjoyable experience of using the Internet, and with craving or withdrawal syndrome; and (b) instrumental behaviors (compulsion) geared toward seeking the former (positive reward) or reducing the discomfort associated with the latter (negative reward).

Adolescents with IA can be expected to display: (a) a lower ability to use reflexivity to manage their internal states; and (b) a greater propensity for impulsive behaviors to manage these states. This is the hypothesis recently proposed by Wei et al. (2017) to explain internet gaming disorder (IGD), a form of IA. However, alongside the presence of a hypoactive reflective system and an overactive impulsive system, these authors also hypothesize a dysregulation of the interoceptive awareness system, and suggest that this dysregulation increases the incentive salience of Internet use, as well as the feeling of craving deriving from its compulsive use ( Wei et al., 2017 ). This thesis could explain the relationship commonly observed between compulsive use of the Internet and somatization ( Yang et al., 2005 ).

Somatization is defined as the “ unconscious process of expressing psychological distress in the form of physical symptoms ” ( Nakkas et al., 2019 ), and it is commonly found among adolescents with IA. It is estimated that 9% of Internet-addicted adolescents display somatization ( Yang, 2001 ), reported in the literature to consist of somatic symptoms ( Potembska et al., 2019 ), chronic pain ( Wei et al., 2012 ; Fava et al., 2019 ), physical health problems ( Sung et al., 2013 ), and sleep disorders ( Tamura et al., 2017 ). Moreover, in late adolescence, the presence of somatization has been positively associated with the intensity of specific forms of IA, such as IGD ( Cerniglia et al., 2019 ). One study showed that higher somatization and interpersonal sensitivity scores predict problematic smartphone use ( Fırat et al., 2018 ). Ballespi et al. (2019) , illustrate that inability to mentalize is associated with a higher frequency of somatic complaints.

Although the involvement of somatization in the etiopathogenesis of IA is not yet clear, models recently advanced to explain the development of addiction assign it a primary role. In the triadic neurocognitive model of addiction ( Noël et al., 2013 ), for example, perception of the somatic state of the organism, governed by the insular cortex, is considered a factor that mediates the development of addiction. In fact, in the absence of cognitive processing of the bottom-up somatic signals mediated by this cerebral structure, the main symptoms of addiction suddenly disappear.

These data were recently confirmed by Naqvi et al. (2007) , who showed that absence of the somatic symptoms typical of craving and physical abstinence, induced by ischemic damage to the insula, allowed heavy smokers to give up smoking.

Somatization has been reported in association with IA in a college student population ( Alavi et al., 2011 ), and it has also been identified among the causal factors and predictors of IA among first-year college students ( Yao et al., 2013 ). Indeed, this latter study confirmed that students with somatization seem to have a greater tendency to develop IA. In addition, a study by Biby (1998) showed that higher somatization scores are linked to higher obsessive-compulsive tendency scores. Therefore, if a key role of somatic symptoms in modulating the activity of the reflexive and impulsive systems can be taken to explain the development of IA, it seems possible to hypothesize that the presence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, commonly found in adolescents with IA ( Yen et al., 2008 ), may also be linked to the presence of somatization. In this sense, an additional hypothesis is that higher somatization in adolescents might exacerbate the effect of obsessive-compulsive symptoms on IA. Surprisingly, this hypothesis has not been investigated in the literature to date, although contemporary etiopathogenetic models suggest the importance of bottom-up somatic signals in addiction disorders ( Verdejo-García and Bechara, 2009 ). In fact, somatic symptoms may be linked to the presence of the same top-down processing of body signals related to craving or abstinence. According to the above hypothesis, these symptoms may upset the activity of the cognitive system, shifting it away from inhibitory control of Internet use, implemented by the reflexive system, toward compulsive behaviors, driven by the impulsive system ( Wei et al., 2017 ). In this way, high levels of somatization could both promote the development of IA and reinforce the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA.

In conclusion, our hypothesis is that somatization moderates the positive relationship between OC symptoms and IA. Specifically, the higher the level of somatization, the stronger the relationship.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Participants were recruited from schools in the north of Italy. The study was presented during the participants’ classes. Students were invited to take part in a research study that aimed to investigate: drug use/abuse, gambling problems, alcohol use/abuse, mood. Students who provided informed consent were given two self-report instruments. All the participants were free to stop filling in the questionnaires at any time. Underage subjects needed parental permission to participate in this study.

The participants (57.7% females) ranged in age from 16 to 22 years (mean age 17.52 ± 1.15). All were third (35%), fourth (37%), or fifth grade (28%) Italian secondary school students.

Instruments

Symptom checklist 90—revised (scl-90-r; derogatis, 1994 ).

The Somatization (SOM;12 items) and Obsessive-Compulsive (OC; 10 items) subscales of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R were used. The participants used a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely), to rate the extent to which they had experienced the listed symptoms during the past week. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 for SOM, and 0.82 for OC.

Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998 )

This is a 20-item questionnaire on which respondents are asked to rate, on a five-point Likert scale, items investigating the degree to which their Internet use affects their daily routine, social life, productivity, sleeping patterns, and feelings. The minimum score is 20, and the maximum is 100; the higher the score, the greater the problems caused by Internet use. Young suggests that a score of 20–39 points is that of an average on-line user who has complete control over his/her Internet use; a score of 40–69 indicates frequent problems due to Internet use; and a score of 70–100 means that the individual’s Internet use is causing significant problems. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Socio-Demographics

The participants reported their age, gender, school and grade. In order to maintain privacy, no other personal information was requested.

Control Variables

The use of illicit drugs and gambling behavior were introduced as control variables. Specifically, the participants answered questions on their habits regarding any use of illicit drugs (cannabis, cocaine, heroin), alcohol consumption, and gambling activities, such as scratch cards, lottery tickets, football pools, new slot machines (VLTs) and video poker, betting on sporting or other events, poker and other card games.

Statistical Analyses

All the analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 and AMOS ( Arbuckle, 2012 ). A series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) was conducted to establish the discriminant validity of the scales. A full measurement model was initially tested, comparing it to a one-factor structure (in which all the items loaded into a common factor). The model fit was tested by using the comparative fit index (CFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Kline (2008) and Byrne (2016) , the CFI and IFI values should have a cutoff value of ≥0.90, and the RMSEA a value of ≤ 0.08 to indicate a good fit of the model. Internal consistency of the constructs was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α).

We tested the effects of somatization symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and their interaction on IA by using the SPSS version of Hayes’s (2017) bootstrap-based PROCESS macro ( Hayes, 2012 , 2013 ; Model 1). All predictors were mean-centered prior to computing the interaction term and simple slopes were calculated at ± 1 SD. Age, sex, type of school, grade, use of illicit drugs, and gambling behaviors were included as covariates. To account for non-normality, analyses were performed with bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples.

Preliminary Analyses

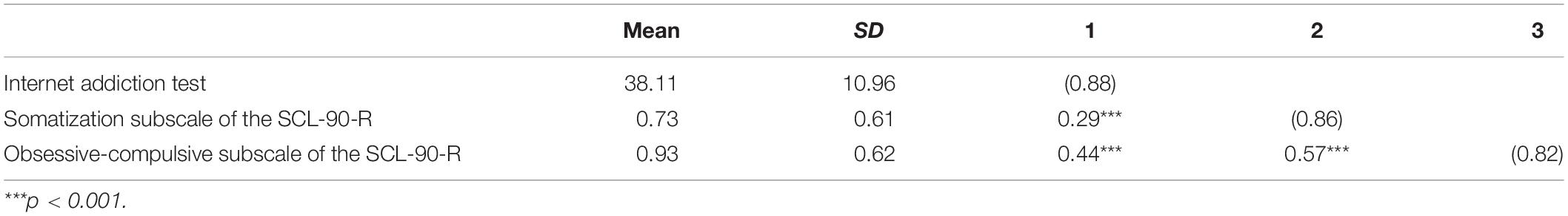

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations and internal consistencies obtained for each scale, and the correlations between the measures used in the current study.

Table 1. Descriptives of study variables ( n = 796).

Measurement Model

Prior to testing our hypothesis, we used CFAs to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of our study variables. The data were found to fit the measurement model: χ 2 (811) = 1150.99, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.035. All items loaded significantly on the intended latent factors.

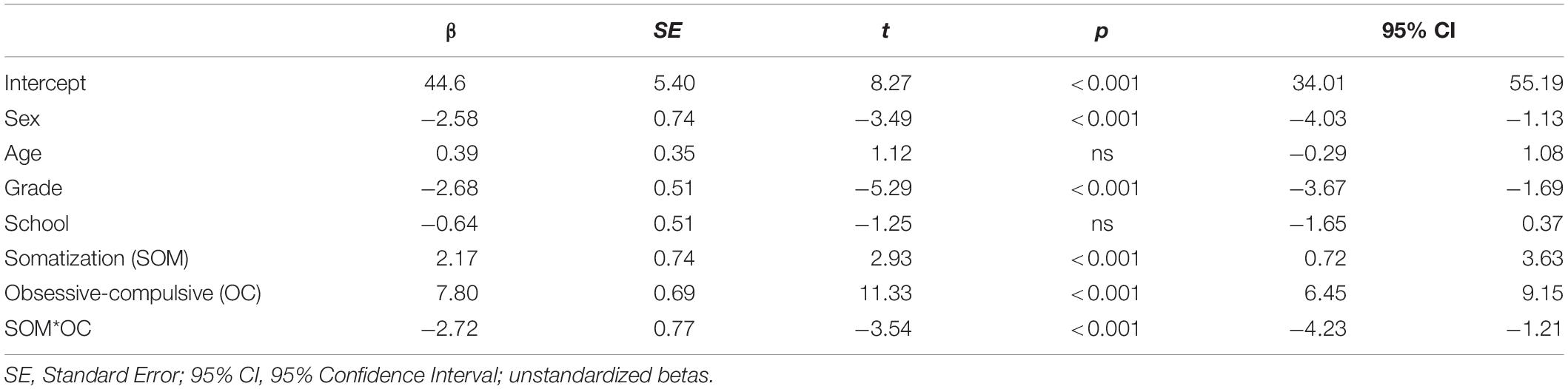

Moderation Analysis

It was hypothesized that obsessive-compulsive symptoms would predict IA, depending on the somatization symptoms (moderation hypothesis). Regression analyses ( Table 2 ) conducted with the PROCESS macro (Model 1; Hayes, 2012 ) showed that obsessive-compulsive symptoms (β = 7.80, p < 0.001) and somatization symptoms (β = 2.18, p < 0.05) were related to IA after controlling for age, sex, grade, school, illicit drug use, and gambling behaviors. The moderation effect was significant t (788) = −3.55; p < 0.001 (β = −2.75, SE = 0.77, CI −4.27 to −1.2) and accounted for a significant portion of variance of IA [Δ R 2 = 1.2%; F ( 788 ) = 12.78 p < 0.01]. In this sense, increasing obsessive-compulsive symptoms predicted increased IA, but this effect was greatest at higher levels of somatization symptoms. The final model accounted for a total of 24.5% of the variance in IA.

Table 2. Results of the moderation analysis.

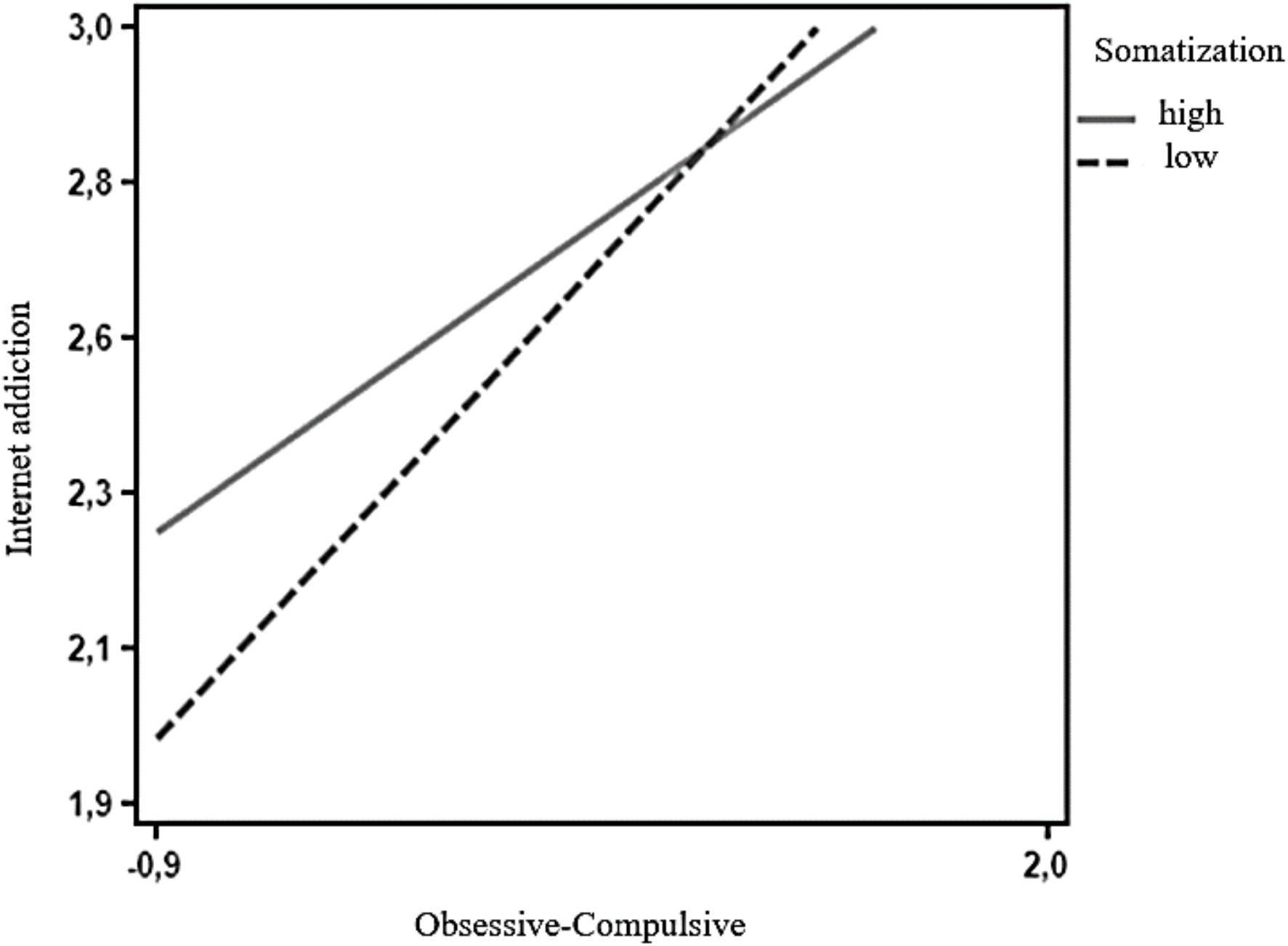

Simple slopes analyses revealed that when somatization symptoms were low (−1 SD), there was a statistically significant effect of obsessive-compulsive symptoms on increased IA (β = 9.48, SE = 0.88, t = 10.80, p < 0.01). Furthermore, also when somatization symptoms were high (+1 SD), there was a significant effect of obsessive-compulsive symptoms on IA (β = 6.13, SE = 0.79, t = 7.83, p < 0.001). Simple slopes analyses ( Figure 1 ) revealed that when somatization symptoms were low.

Figure 1. Interaction term for two levels of somatization: low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD). Using the Johnson-Neyman technique ( Bauer and Curran, 2005 ), we identified the region where the effect of somatization symptoms on the relationship between OC and IA ceased to be statistically significant. Application of the Johnson-Neyman technique gave cutoff scores for somatization symptoms of below 1.81 and above 1.63.

The aim of this study was to increase current knowledge about the relationship between somatization symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and IA in adolescents. Specifically, we hypothesized that the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA would be stronger at higher levels of somatization symptoms.

First, findings from our study suggest that obsessive-compulsive symptoms are associated with IA. These results are in line with prior research, which found that high levels of obsessive-compulsive symptoms are linked to higher IA risk ( Jang et al., 2008 ; Dong et al., 2011 ; Ko et al., 2012 ). Furthermore, IA has typically been described as a secondary condition resulting from various primary disorders, although findings in young adult samples have suggested that, within a range of psychopathologies, only obsessive-compulsive symptoms preceded IA ( Dong et al., 2011 ; Ko et al., 2012 ). The obsessive-compulsive symptoms observed in association with IA are similar to those of OCD, so much so that many researchers define IA as compulsive computer use ( Kuss et al., 2014 ). However, the obsessive-compulsive symptoms of OCD have been described as more ego-dystonic than those of IA ( Shapira et al., 2000 ). In general, the obsessive-compulsive symptoms of IA stem from recurring or persistent positive or negative thoughts (obsessions) that motivate the individual to implement behaviors (compulsions) intended to allow him/her to experience the hedonic satisfaction deriving from obtaining a positive reinforcement ( Robbins and Clark, 2015 ), or to reduce the distress typically associated with craving and abstinence states. IA may thus serve as a strategy for relieving pre-existing obsessive-compulsive psychopathology, a mechanism that, in turn, could actually reinforce the symptoms ( Ko et al., 2012 ). Similarly, this association could be further reinforced by underlying mechanisms shared by OC and IA behaviors ( Ko et al., 2012 ). Repetitive behavioral manifestations aimed at achieving immediate gratification or de-escalating the distress triggered by obsessive thoughts in order to improve one’s feelings are typical of addictions and compulsive behaviors ( Robbins and Clark, 2015 ). In the present study, the main effect of somatization symptoms on IA was in line with the findings of previous research ( Yang et al., 2005 ; Yen et al., 2008 ; Alavi et al., 2011 ; Yao et al., 2013 ). Somatization is conceptualized as a process that leads to translation of psycho-emotional distress into bodily discomfort ( Nakkas et al., 2019 ). Subjects with somatization disorders requiring inpatient treatment manifest deficits in both emotional awareness and Theory of Mind functioning. These deficits may underlie the phenomenon of somatization ( Subic-Wrana et al., 2010 ).

As regards our moderation hypothesis, we found that the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA was greatest at higher levels of somatization symptoms. Our results showed that in adolescents with higher somatization (+1 SD), the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and IA was stronger. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated this relationship. Our results are in line with the triadic theory of addiction ( Noël et al., 2013 ), where somatization, as a major expression of the enteroceptive system, could hinder the management of normal emotional distress through problem-focused coping strategies based on reflexive system mentalization skills. This apparent partial impairment of the reflexive system’s capacity to regulate emotional distress could therefore lead adolescents to adopt emotion-focused coping strategies, such as ones related to implementation of the same obsessive-compulsive behaviors promoted by the impulsive system. Somatization could therefore impair the mentalization skills used by the reflexive system to inhibit compulsive behaviors driven by the impulsive system, predisposing the adolescent to develop IA. This could explain why obsessive-compulsive symptoms are often found in the literature as prodromes of IA development ( Dong et al., 2011 ; Ko et al., 2012 ), as well as why IA has typically been described as a secondary disorder resulting from a primary one, like obsessive-compulsive symptomatology ( Dong et al., 2011 ; Ko et al., 2012 ), a relationship that is confirmed in our study.

Our analyses were performed controlling for gender, age, grade, and school. Specifically, a significant gender difference emerged, as showed in previous studies ( Cao et al., 2011 ; Barke et al., 2012 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ). As showed in a study by Feng et al. (2019) , we have found a significant grade difference.

The present study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design used does not allow the identification of causal relationships among variables. We cannot definitively conclude that obsessive-compulsive symptoms cause IA and that this relationship depends on levels of somatization. Future studies should consider longitudinal data to overcome the cross-sectional limitations. A second, potential, limitation concerns the reliance on self-reported data, which might have caused common method bias. However, we ran the Harman’s single factor test, which suggested that common method bias did not affect the results of this study. A third limitation concerns mentalization ability. Good mentalization could be protective against somatization, but we did not measure it. Future research could explore this aspect through specific questionnaires.

Adolescence is an important period of physical and psychological development. From a clinical perspective, the results of this study show that somatization is an important moderation factor in adolescence. The incapacity to use coping strategies and mentalization strategies to counter negative emotions could increase the somatization effect. In adolescents, obsessive-compulsive symptoms can be moderated by somatization. In this period of development, it is very important to pay attention to bodily signals, as they can mask psychological problems. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms can be very invalidating, and they can be exacerbated by somatization. Teenagers seeking a coping response in technological devices are at considerable risk of developing pathological use of these devices.

In conclusion, somatization is an important aspect to consider when dealing with adolescent patients. It could be a moderation factor capable of exacerbating obsessive-compulsive symptoms or IA. This particular aspect needs more studies in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the CARU-Comitato di Approvazione per la Ricerca sull’Uomo, Università di Verona. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

FL, AR, and LZ were responsible for the study concept and design. SC, FC, and RM contributed to the data acquisition. IP assisted with the data analysis and interpretation of findings. AF, LZ, IP, and AC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alavi, S. S., Maracy, M. R., Jannatifard, F., and Eslami, M. (2011). The effect of psychiatric symptoms on the Internet addiction disorder in Isfahan’s university students. J. Res. Med. Sci. 16, 793–800.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association [APA] (2013). Manuale Diagnostico e Statistico dei Disturbi Mentali, DSM-5 , 5th Edn. Milano: Tr. it. Raffaello Cortina.

Andreou, E., and Svoli, H. (2013). The association between internet user characteristics and dimensions of internet addiction among Greek adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 11, 139–148. doi: 10.1007/s11469-012-9404-3

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arbuckle, J. L. (2012). IBM SPSS AMOS (Version 21.0) [Computer Program] . Chicago, IL: IBM.

Ballespi, S., Vives, J., Alonso, N., Sharp, C., Ramirez, M. S., Fonagy, P., et al. (2019). To know or not to know? Mentalization as protection from somatic complaints. PLoS One 14:e0215308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215308

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barke, A., Nyenhuis, N., and Kröner-Herwig, B. (2012). The German version of the internet addiction test: a validation study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 15, 534–542. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0616

Bauer, D. J., and Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: inferential and graphical techniques. Multi. Behav. Res. 40, 373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5

Bernardi, S., and Pallanti, S. (2009). Internet addiction: a descriptive clinical study focusing on comorbidities and dissociative symptoms. Compr. Psychiatry 50, 510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.011

Biby, E. L. (1998). The relationship between body dysmorphic disorder and depression, self-esteem, somatization, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 54, 489–499. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199806)54:4<489::aid-jclp10<3.0.co;2-b

Block, J. J. (2008). Issues for DSM-V: internet addiction. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 306–307. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. London: Routledge.

Cao, H., Sun, Y., Wan, Y., Hao, J., and Tao, F. (2011). Problematic internet use in Chinese adolescents and its relation to psychoso- matic symptoms and life satisfaction. BMC Public Health 11:802. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-802

Carli, V., Durkee, T., Wasserman, D., Hadlaczky, G., Despalins, R., Kramarz, E., et al. (2013). The association between pathological internet use and comorbid psychopathology: a systematic review. Psychopathology 46, 1–13. doi: 10.1159/000337971

Carlson, G. A. (2000). The challenge of diagnosing depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Affect. Disord. 61, S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00283-4

Cecilia, M. R., Mazza, M., Cenciarelli, S., Grassi, M., and Cofini, V. (2013). The relationshipbetween compulsive behavior and internet addiction. Styles Commun. 5, 24–31.

Cerniglia, L., Guicciardi, M., Sinatra, M., Macis, L., Simonelli, A., and Cimino, S. (2019). The use of digital technologies, impulsivity and psychopathological symptoms in adolescence. Behav. Sci. 9:82. doi: 10.3390/bs9080082

Derogatis, L. R. (1994). Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R): Administration, Scoring and Proce- dures Manual , 3rd Edn. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

Dong, G., Lu, Q., Zhou, H., and Zhao, X. (2011). Precursor or sequela: pathological disorders in people with Internet addiction disorder. PLoS One 6:e14703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014703

Durkee, T., Carli, V., Floderus, B., Wasserman, C., Sarchiapone, M., Apter, A., et al. (2016). Pathological internet use and risk-behaviors among European adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030294

Fava, G. A., McEwen, B. S., Guidi, J., Gostoli, S., Offidani, E., and Sonino, N. (2019). Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology 108, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.028

Feng, Y., Ma, Y., and Zhong, Q. (2019). ‘The relationship between adolescents’ stress and internet addiction: a mediated-moderation model’. Front. Psychol. 10:2248. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02248

Fırat, S., Gül, H., Sertçelik, M., Gül, A., Gürel, Y., and Kılıç, B. G. (2018). The relationship between problematic smartphone use and psychiatric symptoms among adolescents who applied to psychiatry clinics. Psychiatry Res. 270, 97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.015

Fox, S., and Duggan, M. (2013). Health Online, 2013. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center.

García-Oliva, C., and Piqueras, J. A. (2016). Experiential avoidance and technological addictions in adolescents. J. Behav. Addict. 5, 293–303. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.041

Gonzalez-Bueso, V., Santamaria, J. J., Fernandez, D., Merino, L., Montero, E., and Riba, J. (2018). Association between internet gaming disorder or pathological video-game use and comorbid psychopathology: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15:668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15040668

Griffiths, M. (2000). Does internet and computer addiction exist? Some case study evidence. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 3, 211–218. doi: 10.1089/109493100316067

Griffiths, M. D., and Meredith, A. (2009). Videogame addiction and its treatment. J. Contemp. Psychotherapy 39, 247–253. doi: 10.1007/s10879-009-9118-4

Gundogar, A., Bakim, B., Ozer, O., and Karamustafalioglu, O. (2012). P-32 – The association between internet addiction, depression and ADHD among high school students. Eur. Psychiatry 27:1. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(12)74199-8

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White Paper] .

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach , 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., and Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behaviour disorder: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 64, 1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152

Ho, R. C., Zhang, M. W., Tsang, T. Y., Toh, A. H., Pan, F., and Lu, Y. (2014). The association between internet addiction and psychiatric co-morbidity: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 14:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-183

Jang, K. S., Hwang, S. Y., and Choi, J. Y. (2008). Internet addiction and psychiatric symptoms among Korean adolescents. J. Sch. Health 78, 165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00279.x

Kline, R. B. (2008). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling , 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford.

Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Chen, C.-S., Chen, C.-C., and Yen, C.-F. (2008). Psychiatric comorbidity of Internet addiction in college students: an interview study. CNS Spectrums 13, 147–153. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016308

Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Yen, C.-F., Chen, C.-S., and Chen, C.-C. (2012). The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. Eur. Psychiatry 27, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.011

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., and Binder, J. F. (2013). Internet addiction in students: prevalence and risk factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.024

Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Karila, L., and Billieux, J. (2014). Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 4026–4052. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990617

Lan, C. M., and Lee, Y. H. (2013). The predictors of internet addiction behaviours for taiwanese elementary school students. Sch. Psychol. Int. 34, 648–657. doi: 10.1177/0143034313479690

Nakkas, C., Annen, H., and Brand, S. (2019). Somatization and coping in ethnic minority recruits. Milit. Med. 184, 11–12. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usz014

Naqvi, N. H., Rudrauf, D., Damasio, H., and Bechara, A. (2007). Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315, 531–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1135926

Noël, X., Brevers, D., and Bechara, A. (2013). A triadic neurocognitive approach to addiction for clinical interventions. Front. Psychiatry 4:179. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00179

Nuutinen, T., Roos, E., Ray, C., Villberg, J., Valimaa, R., and Rasmussen, M. (2014). Computer use, sleep duration and health symptoms: a cross-sectional study of 15-year olds in three countries. Int. J. Public Health 59, 619–628. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0561-y

Phillips, J. G., Ogeil, R. P., and Blaszczynski, A. (2012). Electronic interests and behavioursassociated with gambling problems. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 10, 585–596. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9356-z

Potembska, E., Pawłowska, B., and Szymańska, J. (2019). Psychopathological symptoms in individuals at risk of Internet addiction in the context of selected demographic factors. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 26, 33–38. doi: 10.26444/aaem/81665

Robbins, T. W., and Clark, L. (2015). Behavioral addictions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30, 66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.09.005

Sasmaz, T., Oner, S., Kurt, A. O., Yapici, G., Yazici, A. E., Bugdayci, R., et al. (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of internet addiction in high school students. Eur. J. Public Health 24, 15–20. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt051

Shapira, N. A., Goldsmith, T. D., Keck, P. E., Khosla, U. M., and McElroy, S. L. (2000). Psychiatric features of individuals with problematic internet use. J. Affect. Disord . 57, 267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00107-x

Shapira, N. A., Lessig, M. C., Goldsmith, T. D., Szabo, S. T., Lazoritz, M., Gold, M. S., et al. (2003). Problematic internet use: proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress. Anxiety 17, 207–216. doi: 10.1002/da.10094

Subic-Wrana, C., Beutel, M. E., Knebel, A., and Lane, R. D. (2010). Theory of mind and emotional awareness deficits in patients with somatoform disorders. Psychosom. Med. 72, 404–411. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d35e83

Sung, J., Lee, J., Noh, H., Park, Y. S., and Ahn, E. J. (2013). Associations between the risk of internet addiction and problem behaviors among Korean adolescents. Korean J. Fam. Med. 34, 115–122. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.2.115

Tamura, H., Nishida, T., Tsuji, A., and Sakakibara, H. (2017). Association between excessive use of mobile phone and insomnia and depression among Japanese adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1–11.

Tereshchenko, S., and Kasparov, E. (2019). Neurobiological risk factors for the development of internet addiction in adolescents. Behav. Sci. 9:62. doi: 10.3390/bs9060062

Verdejo-García, A., and Bechara, A. (2009). A somatic-marker theory of addiction. Neuropharmacology 56, 48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.035

Wei, H. T., Chen, M. H., Huang, P. C., and Bai, Y. M. (2012). The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry 12:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-92

Wei, L., Zhang, S., Turel, O., Bechara, A., and He, Q. (2017). A tripartite neurocognitive model of internet gaming disorder. Front. Psychiatry 8:285. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00285

Yang, C. K. (2001). Sociopsychiatric characteristics of adolescents who use computers to excess. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 104, 217–222. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00197.x

Yang, C. K., Choe, B. M., Baity, M., Lee, J. H., and Cho, J. S. (2005). SCL-90-R and 16PF profiles of senior high school students with excessive internet use. Can. J. Psychiatry 50, 407–414. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000704

Yao, B., Han, W., Zeng, L., and Guo, X. (2013). Freshman year mental health symptoms and level of adaptation as predictors of internet addiction: a retrospective nested case-control study of male Chinese college students. Psychiatry Res. 210, 541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.023

Yen, J. Y., Ko, C. H., Yen, C. F., Chen, S. H., Chung, W. L., and Chen, C. C. (2008). Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with Internet addiction: comparison with substance use. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 62, 9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01770.x

Yoo, H. J., Cho, S. C., Ha, J., Yune, S. K., Kim, S. J., Hwang, J., et al. (2004). Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 58, 487–494.

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1, 237–244. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237

Zboralski, K., Orzechowska, A., Talarowska, M., Darmosz, A., Janiak, A., Janiak, M., et al. (2009). The prevalence of computer and internet addiction among pupils. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej 63, 8–12.

Keywords : somatization, internet addiction, adolescent, moderation, obssessive-compulsive disorder

Citation: Zamboni L, Portoghese I, Congiu A, Carli S, Munari R, Federico A, Centoni F, Rizzini AL and Lugoboni F (2020) Internet Addiction and Related Clinical Problems: A Study on Italian Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 11:571638. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.571638

Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 10 November 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Zamboni, Portoghese, Congiu, Carli, Munari, Federico, Centoni, Rizzini and Lugoboni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lorenzo Zamboni, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Advertisement

“Internet Addiction”: a Conceptual Minefield

- Open access

- Published: 19 September 2017

- Volume 16 , pages 225–232, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Francesca C. Ryding 1 &

- Linda K. Kaye 1

17k Accesses

56 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

With Internet connectivity and technological advancement increasing dramatically in recent years, “Internet addiction” (IA) is emerging as a global concern. However, the use of the term ‘addiction’ has been considered controversial, with debate surfacing as to whether IA merits classification as a psychiatric disorder as its own entity, or whether IA occurs in relation to specific online activities through manifestation of other underlying disorders. Additionally, the changing landscape of Internet mobility and the contextual variations Internet access can hold has further implications towards its conceptualisation and measurement. Without official recognition and agreement on the concept of IA, this can lead to difficulties in efficacy of diagnosis and treatment. This paper therefore provides a critical commentary on the numerous issues of the concept of “Internet addiction”, with implications for the efficacy of its measurement and diagnosticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

Azmawati Mohammed Nawi, Rozmi Ismail, … Nurul Shafini Shafurdin

Online Dating and Problematic Use: A Systematic Review

Gabriel Bonilla-Zorita, Mark D. Griffiths & Daria J. Kuss

Social Media and Youth Mental Health

Paul E. Weigle & Reem M. A. Shafi

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What Is Internet Addiction (IA)?

Traditionally, the term addiction has been associated with psychoactive substances such as alcohol and tobacco; however, behaviours including the use of the Internet have more recently been identified as being addictive (Sim et al. 2012 ). The concept of IA is generally characterised as an impulse disorder by which an individual experiences intense preoccupation with using the Internet, difficulty managing time on the Internet, becoming irritated if disturbed whilst online, and decreased social interaction in the real world (Tikhonov and Bogoslovskii 2015 ). These features were initially proposed by Young ( 1998 ) based on the criteria for pathological gambling (Yellowlees and Marks 2007 ), and have since been adapted for consideration within the DSM-5. This has been well received by many working in the field of addiction (Király et al. 2015 ; Petry et al. 2014 ), and has been suggested to enable a degree of standardisation in the assessment and identification of IA (King and Delfabbro 2014 ). However, there is still debate and controversy surrounding this concept, in which researchers acknowledge much conceptual disparity and the need for further work to fully understand IA and its constituent disorders (Griffiths et al. 2014 ).

Much of the debate relates to the issue that IA is conceptualised as addiction to the Internet as a singular entity, although it incorporates an array of potential activities (Van Rooij and Prause 2014 ). That is, the Internet, in all its formats, whether accessed via PC, console, laptop or mobile device, is fundamentally a portal through which we access activities and services. Internet connectivity thus provides us with ways of accessing the following types of activities; play (e.g. online forms of gaming, gambling), work (accessing online resources, downloading software, emailing, website hosting), socialising (social networking sites, group chats, online dating), entertainment (film databases, porn, music), consumables (groceries, clothes), as well as many other activities and services. In this way, the Internet is a highly multidimensional and diverse environment which affords a multitude of experiences as a product of the specific virtual domain. Thus, it is questionable as to whether there is any degree of consistency in the concept of IA, in light of these diverse and specific affordances which may relate to Internet engagement. Indeed, it has been indicated that there are several distinct types of IA, including online gaming, social media, and online shopping (Kuss et al. 2013 ), and it has been claimed that through engagement in these behaviours, individuals may become addicted to these experiences, as opposed to the medium itself (Widyanto et al. 2011 ). Thus, IA is arguably too generalised as a concept to adequately capture these nuances. That is, an individual who spends excessive time online for shopping is qualitatively different from someone who watches or downloads porn excessively. These represent distinct behaviours which are arguably underpinned by different gratifications. Thus, the functionality of aspects of the Internet is a key consideration for research in this area (Tokunaga 2016 ). This is perhaps best approached from a uses and gratifications perspective (LaRose et al. 2003 ; Larose et al. 2001a ; Wegmann et al. 2015 ), to more fully understand the aetiology of IA (discussed subsequently). This is often best underpinned by the uses and gratifications theory (Larose et al. 2001a , 2003 ), which seeks to explain (media) behaviours by understanding their specific functions and how they gratify certain needs. Indeed, in the context of IA, this may be particularly useful to establish the extent to which certain Internet-based behaviours may be more or less functional in need gratification than others, and the extent to which it is Internet platform itself which is driving usage or indeed the constituent domains which it affords. If the former, then controlling Internet-based usage behaviour more generically is perhaps appropriate, however, a more specified approach may often be required given the diverse needs the online environment can afford users.

IA from a Gratifications Perspective

It is questionable on the extent to which IA is itself the “addiction” or whether its aetiology relates to other pre-existing conditions, which may be gratified through Internet domains (Caplan 2002 ). One particular theory that has been referenced throughout much developing research (King et al. 2012 ; Laier and Brand 2014 ) is the cognitive-behavioural model, proposed by Davis ( 2001 ). This model suggests that maladaptive cognitions precede the behavioural symptoms of IA (Davis 2001 ; Taymur et al. 2016 ). Since much research focuses on the comorbidity between IA and psychopathology (Orsal et al. 2013 ), this is particularly useful in underpinning the concept of IA, and perhaps provides support that IA is a manifestation of underlying disorders, due to its psychopathological aetiology (Taymur et al. 2016 ). Additionally, the cognitive-behavioural model also distinguishes between both specific and generalised pathological Internet use, in comparison to global Internet behaviours that would not otherwise exist outside of the Internet, such as surfing the web (Shaw and Black 2008 ). As such, it would assume those individuals who spend excessive time playing poker online, for example, are perhaps better categorised as problematic gamblers rather than as Internet addicts (Griffiths 1996 ). This has been particularly advantageous in the contribution to defining IA, as earlier literature tended to focus solely on either content-specific IA, or the amount of time spent online, rather than focussing as to why individuals are actually online (Caplan 2002 ). Indeed, this shows promise in resolving some of the aforementioned issues in the specificity of IA, as well as the likelihood of pre-existing conditions underpinning problematic behaviours on the Internet.

Much of the recent literature in the realm of IA has focused upon Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) which has recently been included as an appendix as “a condition for further study” in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013 ). This has driven a wide range of research which has sought to establish the validity of IGD as an independent clinical condition (Kuss et al. 2017 ). Among the wealth of research papers surrounding this phenomenon, there remains large disparity within the academic community. Although some researchers claim there is consensus on IGD as a valid clinical disorder (Petry et al. 2014 ), others do not support this (e.g. Griffiths et al. 2016 ). As such, the academic literature has some way to go before more established claims can be made towards IGD as a valid construct, and indeed how this impacts upon clinical treatment.

One means by which researchers could move forward in this regard is to establish the validity of IGD to a wider range of gaming formats. That is, IGD research has predominantly defined the reference point in studies as “online games” or in some cases, is has been even less specific (Lemmens et al. 2015 ; Rehbein et al. 2015 ; Thomas and Martin 2010 ). Arguably, there are a range of forms of “online” gaming, including social networking site (SNS) games which are Internet-mediated and thus by definition, would appear under the remit of IGD. Indeed, links between SNS and gaming have been previously noted (Kuss and Griffiths 2017 ), although this has not specifically been empirically explored in the context of IGD symptomology. For example, causal form of gaming as is typically the case for SNS gaming have their own affordances in respect of where and how they are played, given these are often played on mobile devices rather than on more traditional PC or console platforms. Further, the demographics of who are most likely to play these games can vary from others forms of gaming which have predominated the IGD literature (Hull et al. 2013 ; Leaver and Wilson 2016 ). Accordingly, these affordances present additional nuances, which the literature has not yet fully accounted for in its exploration of IGD. Clearly, IGD relates to a specific form of Internet behaviour which may be conceptualised within IA, yet is paramount to understand it as a separate entity to ensure the conceptualisation and any associated treatment provision is sufficiently nuanced. Likewise, the same case can be made for many other Internet-based behaviours which may be best being established in respect of their functionality and gratification purposes for users.

IA as a Contextual Phenomenon