Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

Published on January 20, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

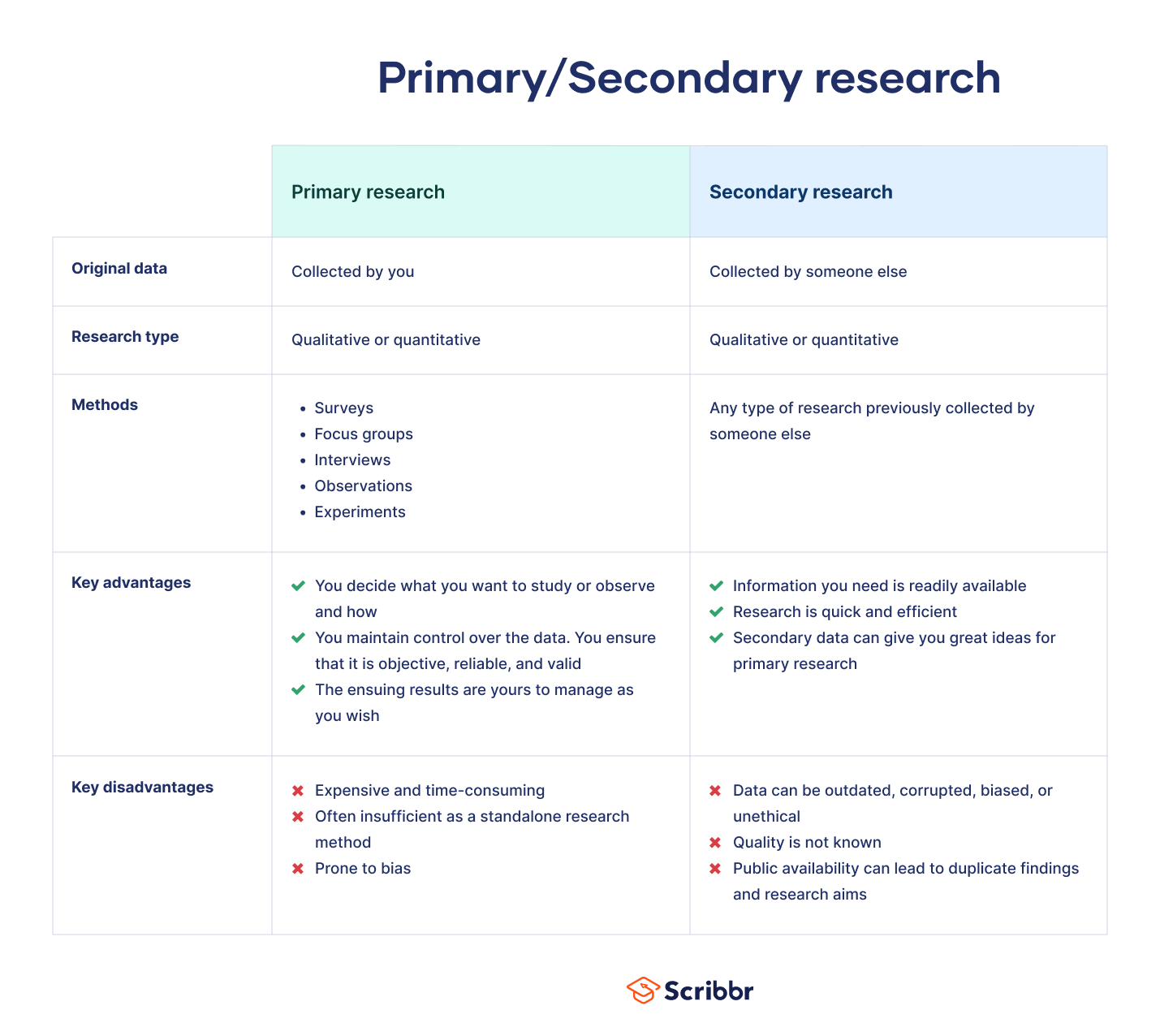

Secondary research is a research method that uses data that was collected by someone else. In other words, whenever you conduct research using data that already exists, you are conducting secondary research. On the other hand, any type of research that you undertake yourself is called primary research .

Secondary research can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. It often uses data gathered from published peer-reviewed papers, meta-analyses, or government or private sector databases and datasets.

Table of contents

When to use secondary research, types of secondary research, examples of secondary research, advantages and disadvantages of secondary research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Secondary research is a very common research method, used in lieu of collecting your own primary data. It is often used in research designs or as a way to start your research process if you plan to conduct primary research later on.

Since it is often inexpensive or free to access, secondary research is a low-stakes way to determine if further primary research is needed, as gaps in secondary research are a strong indication that primary research is necessary. For this reason, while secondary research can theoretically be exploratory or explanatory in nature, it is usually explanatory: aiming to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Secondary research can take many forms, but the most common types are:

Statistical analysis

Literature reviews, case studies, content analysis.

There is ample data available online from a variety of sources, often in the form of datasets. These datasets are often open-source or downloadable at a low cost, and are ideal for conducting statistical analyses such as hypothesis testing or regression analysis .

Credible sources for existing data include:

- The government

- Government agencies

- Non-governmental organizations

- Educational institutions

- Businesses or consultancies

- Libraries or archives

- Newspapers, academic journals, or magazines

A literature review is a survey of preexisting scholarly sources on your topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant themes, debates, and gaps in the research you analyze. You can later apply these to your own work, or use them as a jumping-off point to conduct primary research of your own.

Structured much like a regular academic paper (with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion), a literature review is a great way to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject. It is usually qualitative in nature and can focus on a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. A case study is a great way to utilize existing research to gain concrete, contextual, and in-depth knowledge about your real-world subject.

You can choose to focus on just one complex case, exploring a single subject in great detail, or examine multiple cases if you’d prefer to compare different aspects of your topic. Preexisting interviews , observational studies , or other sources of primary data make for great case studies.

Content analysis is a research method that studies patterns in recorded communication by utilizing existing texts. It can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature, depending on whether you choose to analyze countable or measurable patterns, or more interpretive ones. Content analysis is popular in communication studies, but it is also widely used in historical analysis, anthropology, and psychology to make more semantic qualitative inferences.

Secondary research is a broad research approach that can be pursued any way you’d like. Here are a few examples of different ways you can use secondary research to explore your research topic .

Secondary research is a very common research approach, but has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of secondary research

Advantages include:

- Secondary data is very easy to source and readily available .

- It is also often free or accessible through your educational institution’s library or network, making it much cheaper to conduct than primary research .

- As you are relying on research that already exists, conducting secondary research is much less time consuming than primary research. Since your timeline is so much shorter, your research can be ready to publish sooner.

- Using data from others allows you to show reproducibility and replicability , bolstering prior research and situating your own work within your field.

Disadvantages of secondary research

Disadvantages include:

- Ease of access does not signify credibility . It’s important to be aware that secondary research is not always reliable , and can often be out of date. It’s critical to analyze any data you’re thinking of using prior to getting started, using a method like the CRAAP test .

- Secondary research often relies on primary research already conducted. If this original research is biased in any way, those research biases could creep into the secondary results.

Many researchers using the same secondary research to form similar conclusions can also take away from the uniqueness and reliability of your research. Many datasets become “kitchen-sink” models, where too many variables are added in an attempt to draw increasingly niche conclusions from overused data . Data cleansing may be necessary to test the quality of the research.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 30, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/secondary-research/

Largan, C., & Morris, T. M. (2019). Qualitative Secondary Research: A Step-By-Step Guide (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Peloquin, D., DiMaio, M., Bierer, B., & Barnes, M. (2020). Disruptive and avoidable: GDPR challenges to secondary research uses of data. European Journal of Human Genetics , 28 (6), 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0596-x

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, primary research | definition, types, & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a case study | definition, examples & methods, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Qualitative Secondary Analysis: A Case Exemplar

- PMID: 29254902

- PMCID: PMC5911239

- DOI: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.007

Qualitative secondary analysis (QSA) is the use of qualitative data that was collected by someone else or was collected to answer a different research question. Secondary analysis of qualitative data provides an opportunity to maximize data utility, particularly with difficult-to-reach patient populations. However, qualitative secondary analysis methods require careful consideration and explicit description to best understand, contextualize, and evaluate the research results. In this article, we describe methodologic considerations using a case exemplar to illustrate challenges specific to qualitative secondary analysis and strategies to overcome them.

Keywords: Critical illness; ICU; qualitative research; secondary analysis.

Copyright © 2017 National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure statement: Drs. Tate and Happ have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose that relate to the content of this manuscript and do not anticipate conflicts in the foreseeable future.

Similar articles

- Patient Perspectives on Sharing Anonymized Personal Health Data Using a Digital System for Dynamic Consent and Research Feedback: A Qualitative Study. Spencer K, Sanders C, Whitley EA, Lund D, Kaye J, Dixon WG. Spencer K, et al. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Apr 15;18(4):e66. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5011. J Med Internet Res. 2016. PMID: 27083521 Free PMC article.

- Challenges arising when seeking broad consent for health research data sharing: a qualitative study of perspectives in Thailand. Cheah PY, Jatupornpimol N, Hanboonkunupakarn B, Khirikoekkong N, Jittamala P, Pukrittayakamee S, Day NPJ, Parker M, Bull S. Cheah PY, et al. BMC Med Ethics. 2018 Nov 7;19(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0326-x. BMC Med Ethics. 2018. PMID: 30404642 Free PMC article.

- Anaesthetists' perceptions of facilitative weaning strategies from mechanical ventilator in the intensive care unit (ICU): a qualitative interview study. Pettersson S, Melaniuk-Bose M, Edell-Gustafsson U. Pettersson S, et al. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012 Jun;28(3):168-75. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2011.12.004. Epub 2012 Jan 9. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2012. PMID: 22227354

- The acceptability of conducting data linkage research without obtaining consent: lay people's views and justifications. Xafis V. Xafis V. BMC Med Ethics. 2015 Nov 17;16(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0070-4. BMC Med Ethics. 2015. PMID: 26577591 Free PMC article. Review.

- Getting started with qualitative research: developing a research proposal. Vivar CG, McQueen A, Whyte DA, Armayor NC. Vivar CG, et al. Nurse Res. 2007;14(3):60-73. doi: 10.7748/nr2007.04.14.3.60.c6033. Nurse Res. 2007. PMID: 17494469 Review.

- Adolescent pregnancy persists in Nigeria: Does household heads' age matter? Mbulu CO, Yang L, Wallen GR. Mbulu CO, et al. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024 May 15;4(5):e0003212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0003212. eCollection 2024. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38748678 Free PMC article.

- Physician Perspectives on Addressing Anti-Black Racism. Brown CE, Marshall AR, Cueva KL, Snyder CR, Kross EK, Young BA. Brown CE, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jan 2;7(1):e2352818. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.52818. JAMA Netw Open. 2024. PMID: 38265801 Free PMC article.

- Decision-Making on Contraceptive Use among Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Malaysia: A Qualitative Inquiry. Sukeri S, Sulaiman Z, Hamid NA, Ibrahim SA. Sukeri S, et al. Korean J Fam Med. 2024 Jan;45(1):27-36. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.23.0088. Epub 2023 Oct 18. Korean J Fam Med. 2024. PMID: 37848368 Free PMC article.

- Knowledge exchange sessions on primary health care research findings in public libraries: A qualitative study with citizens in Quebec. Laberge M, Brundisini FK, Zomahoun HTV, Sawadogo J, Massougbodji J, Gogovor A, David G, Légaré F. Laberge M, et al. PLoS One. 2023 Jul 25;18(7):e0289153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289153. eCollection 2023. PLoS One. 2023. PMID: 37490456 Free PMC article.

- Men's experiences of receiving a prostate cancer diagnosis after opportunistic screening-A qualitative descriptive secondary analysis. Gellerstedt L, Langius-Eklöf A, Kelmendi N, Sundberg K, Craftman ÅG. Gellerstedt L, et al. Health Expect. 2022 Oct;25(5):2485-2491. doi: 10.1111/hex.13567. Epub 2022 Jul 27. Health Expect. 2022. PMID: 35898187 Free PMC article.

- Broyles L, Colbert A, Tate J, Happ MB. Clinicians’ evaluation and management of mental health, substance abuse, and chronic pain conditions in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(1):87–93. - PubMed

- Coyer SM, Gallo AM. Secondary analysis of data. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2005;19(1):60–63. - PubMed

- Fielding N. Getting the most from archived qualitative data: Epistemological, practical and professional obstacles. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2004;7(1):97–104.

- Gladstone BM, Volpe T, Boydell KM. Issues encountered in a qualitative secondary analysis of help-seeking in the prodrome to psychosis. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34(4):431–442. - PubMed

- Happ MB, Swigart VA, Tate JA, Arnold RM, Sereika SM, Hoffman LA. Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 2007;36(1):47–57. - PMC - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- R01 NR007973/NR/NINR NIH HHS/United States

- R03 AG063276/AG/NIA NIH HHS/United States

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Strategies in Teaching Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data

- Louise Corti ESDS Qualidata

- Libby Bishop ESDS Qualidata

Author Biographies

Louise corti, esds qualidata, libby bishop, esds qualidata, how to cite.

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2005 Louise Corti, Libby Bishop

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Louise Corti, Annette Day, Gill Backhouse, Confidentiality and Informed Consent: Issues for Consideration in the Preservation of and Provision of Access to Qualitative Data Archives , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 1 No. 3 (2000): Text . Archive . Re-Analysis

- Louise Corti, Progress and Problems of Preserving and Providing Access to Qualitative Data for Social Research—The International Picture of an Emerging Culture , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 1 No. 3 (2000): Text . Archive . Re-Analysis

- Louise Corti, Andreas Witzel, Libby Bishop, On the Potentials and Problems of Secondary Analysis. An Introduction to the FQS Special Issue on Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 6 No. 1 (2005): Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data

- Louise Corti, Gill Backhouse, Acquiring Qualitative Data for Secondary Analysis , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 6 No. 2 (2005): Qualitative Inquiry: Research, Archiving, and Reuse

- Miguel S. Valles, Louise Corti, Maria Tamboukou, Alejandro Baer, Qualitative Archives and Biographical Research Methods. An Introduction to the FQS Special Issue , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 12 No. 3 (2011): Qualitative Archives and Biographical Research Methods

- Louise Corti, Qualitative Data Archival Resource Centre, University of Essex, UK , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 1 No. 3 (2000): Text . Archive . Re-Analysis

- Louise Corti, Arofan Gregory, CAQDAS Comparability. What about CAQDAS Data Exchange? , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 12 No. 1 (2011): The KWALON Experiment: Discussions on Qualitative Data Analysis Software by Developers and Users

- Louise Corti, The European Landscape of Qualitative Social Research Archives: Methodological and Practical Issues , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 12 No. 3 (2011): Qualitative Archives and Biographical Research Methods

- Louise Corti, Nadeem Ahmad, Digitising and Providing Access to Socio-Medical Case Records: The Case of George Brown's Work , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 1 No. 3 (2000): Text . Archive . Re-Analysis

- Katja Mruck, Louise Corti, Susann Kluge, Diane Opitz, About this Issue , Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research: Vol. 1 No. 3 (2000): Text . Archive . Re-Analysis

Make a Submission

Current issue, information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Usage Statistics Information

We log anonymous usage statistics. Please read the privacy information for details.

Developed By

2000-2024 Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research (ISSN 1438-5627) Institut für Qualitative Forschung , Internationale Akademie Berlin gGmbH

Hosting: Center for Digital Systems , Freie Universität Berlin Funding 2023-2025 by the KOALA project

FQS received the Enter Award 2024 in the "Pioneering Achievement" category , funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and implemented by the think tank iRights.Lab.

Privacy Statement Accessibility Statement

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Iran J Public Health

- v.42(12); 2013 Dec

Secondary Data Analysis: Ethical Issues and Challenges

Research does not always involve collection of data from the participants. There is huge amount of data that is being collected through the routine management information system and other surveys or research activities. The existing data can be analyzed to generate new hypothesis or answer critical research questions. This saves lots of time, money and other resources. Also data from large sample surveys may be of higher quality and representative of the population. It avoids repetition of research & wastage of resources by detailed exploration of existing research data and also ensures that sensitive topics or hard to reach populations are not over researched ( 1 ). However, there are certain ethical issues pertaining to secondary data analysis which should be taken care of before handling such data.

Secondary data analysis

Secondary analysis refers to the use of existing research data to find answer to a question that was different from the original work ( 2 ). Secondary data can be large scale surveys or data collected as part of personal research. Although there is general agreement about sharing the results of large scale surveys, but little agreement exists about the second. While the fundamental ethical issues related to secondary use of research data remain the same, they have become more pressing with the advent of new technologies. Data sharing, compiling and storage have become much faster and easier. At the same time, there are fresh concerns about data confidentiality and security.

Issues in Secondary data analysis

Concerns about secondary use of data mostly revolve around potential harm to individual subjects and issue of return for consent. Secondary data vary in terms of the amount of identifying information in it. If the data has no identifying information or is completely devoid of such information or is appropriately coded so that the researcher does not have access to the codes, then it does not require a full review by the ethical board. The board just needs to confirm that the data is actually anonymous. However, if the data contains identifying information on participants or information that could be linked to identify participants, a complete review of the proposal will then be made by the board. The researcher will then have to explain why is it unavoidable to have identifying information to answer the research question and must also indicate how participants’ privacy and the confidentiality of the data will be protected. If the above said concerns are satisfactorily addressed, the researcher can then request for a waiver of consent.

If the data is freely available on the Internet, books or other public forum, permission for further use and analysis is implied. However, the ownership of the original data must be acknowledged. If the research is part of another research project and the data is not freely available, except to the original research team, explicit, written permission for the use of the data must be obtained from the research team and included in the application for ethical clearance.

However, there are certain other issues pertaining to the data that is procured for secondary analysis. The data obtained should be adequate, relevant but not excessive. In secondary data analysis, the original data was not collected to answer the present research question. Thus the data should be evaluated for certain criteria such as the methodology of data collection, accuracy, period of data collection, purpose for which it was collected and the content of the data. It shall be kept for no longer than is necessary for that purpose. It must be kept safe from unauthorized access, accidental loss or destruction. Data in the form of hardcopies should be kept in safe locked cabinets whereas softcopies should be kept as encrypted files in computers. It is the responsibility of the researcher conducting the secondary analysis to ensure that further analysis of the data conducted is appropriate. In some cases there is provision for analysis of secondary data in the original consent form with the condition that the secondary study is approved by the ethics review committee. According to the British Sociological Association’s Statement of Ethical Practice (2004) the researchers must inform participants regarding the use of data and obtain consent for the future use of the material as well. However it also says that consent is not a once-and-for-all event, but is subject to renegotiation over time ( 3 ). It appears that there are no guidelines about the specific conditions that require further consent.

Issues in Secondary analysis of Qualitative data

In qualitative research, the culture of data archiving is absent ( 4 ). Also, there is a concern that data archiving exposes subject’s personal views. However, the best practice is to plan anonymisation at the time of initial transcription. Use of pseudonyms or replacements can protect subject’s identity. A log of all replacements, aggregations or removals should be made and stored separately from the anonymised data files. But because of the circumstances, under which qualitative data is produced, their reinterpretation at some later date can be challenging and raises further ethical concerns.

There is a need for formulating specific guidelines regarding re-use of data, data protection and anonymisation and issues of consent in secondary data analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

- Fielding NG, Fielding JL (2003). Resistance and adaptation to criminal identity: Using secondary analysis to evaluate classic studies of crime and deviance . Sociology , 34 ( 4 ): 671–689. [ Google Scholar ]

- Szabo V, Strang VR (1997). Secondary analysis of qualitative data . Advances in Nursing Science , 20 ( 2 ): 66–74. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statement of Ethical Practice for the British Sociological Association (2004). The British Sociological Association, Durham . Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/media/abouttheuniversity/governanceandmanagement/governance/ethicscommittee/hssec/documents/BSA%20statement%20of%20ethical%20practice.pdf (Last accessed 24November2013)

- Archiving Qualitative Data: Prospects and Challenges of Data Preservation and Sharing among Australian Qualitative Researchers. Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland, 2009 . Available at: http://www.assda.edu.au/forms/AQuAQualitativeArchiving_DiscussionPaper_FinalNov09.pdf (Last accessed 05September2013)

Qualitative Research : Get data for secondary analysis

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Syracuse Qualitative Data Repository "QDR is a dedicated archive for storing and sharing digital data (and accompanying documentation) generated or collected through qualitative and multi-method research in the social sciences. QDR provides search tools to facilitate the discovery of data, and also serves as a portal to material beyond its own holdings, with links to U.S. and international archives. The repository’s initial emphasis is on political science."

- ICPSR The Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) archive includes quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods datasets. Using the search engine, select "Qualitative" under "Type of Analysis."

- Henry A. Murray Research Archive "The Henry A. Murray Research Archive is Harvard's endowed repository for quantitative and qualitative research data at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science. Our collection comprises over 100 terabytes of data, audio, and video. We provide long-term preservation of all types of data of interest to the research community, including numerical, video, audio, interview notes, and other data."

- UK Data Archive The UK Data Archive has quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods data.

- << Previous: Get software

- Next: Network with researchers >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2024

Improving Clerkship to Enhance Patients’ Quality of care (ICEPACQ): a baseline study

- Kennedy Pangholi 1 ,

- Enid Kawala Kagoya 2 ,

- Allan G Nsubuga 3 ,

- Irene Atuhairwe 3 ,

- Prossy Nakattudde 3 ,

- Brian Agaba 3 ,

- Bonaventure Ahaisibwe 3 ,

- Esther Ijangolet 3 ,

- Eric Otim 3 ,

- Paul Waako 4 ,

- Julius Wandabwa 5 ,

- Milton Musaba 5 ,

- Antonina Webombesa 6 ,

- Kenneth Mugabe 6 ,

- Ashley Nakawuki 7 ,

- Richard Mugahi 8 ,

- Faith Nyangoma 1 ,

- Jesca Atugonza 1 ,

- Elizabeth Ajalo 1 ,

- Alice Kalenda 1 ,

- Ambrose Okibure 1 ,

- Andrew Kagwa 1 ,

- Ronald Kibuuka 1 ,

- Betty Nakawuka 1 ,

- Francis Okello 2 &

- Proscovia Auma 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 852 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

175 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Proper and complete clerkships for patients have long been shown to contribute to correct diagnosis and improved patient care. All sections for clerkship must be carefully and fully completed to guide the diagnosis and the plan of management; moreover, one section guides the next. Failure to perform a complete clerkship has been shown to lead to misdiagnosis due to its unpleasant outcomes, such as delayed recovery, prolonged inpatient stay, high cost of care and, at worst, death.

The objectives of the study were to determine the gap in clerkship, the impact of incomplete clerkship on the length of hospital stay, to explore the causes of the gap in clerkship of the patients and the strategies which can be used to improve clerkship of the patients admitted to, treated and discharged from the gynecological ward in Mbale RRH.

Methodology

This was a mixed methods study involving the collection of secondary data via the review of patients’ files and the collection of qualitative data via key informant interviews. The files of patients who were admitted from August 2022 to December 2022, treated and discharged were reviewed using a data extraction tool. The descriptive statistics of the data were analyzed using STATA version 15, while the qualitative data were analyzed via deductive thematic analysis using Atlas ti version 9.

Data were collected from 612 patient files. For qualitative data, a total of 8 key informant interviews were conducted. Social history had the most participants with no information provided at all (83.5% not recorded), with biodata and vital sign examination (20% not recorded) having the least number. For the patients’ biodata, at least one parameter was recorded in all the patients, with the greatest gap noted in terms of recording the nearest health facility of the patient (91% not recorded). In the history, the greatest gap was noted in the history of current pregnancy (37.5% not provided at all); however, there was also a large gap in the past gynecological history (71% not recorded at all), past medical history (71% not recorded at all), past surgical history (73% not recorded at all) and family history (80% not recorded at all). The physical examination revealed the greatest gap in the abdominal examination (43%), with substantial gaps in the general examination (38.5% not recorded at all) and vaginal examination (40.5% not recorded at all), and the vital sign examination revealed the least gap. There was no patient who received a complete clerkship. There was a significant association between clerkships and the length of hospital stay. The causes of the gap in clerkships were multifactorial and included those related to the hospital, those related to the health worker, those related to the health care system and those related to the patient. The strategies to improve the clerkship of patients also included measures taken by health care workers, measures taken by hospitals and measures taken by the government.

Conclusion and recommendation

There is a gap in the clerkships of patients at the gynecological ward that is recognized by the stakeholders at the ward, with some components of the clerkship being better recorded than others, and no patients who received a complete clerkship. There was a significant association between clerkships and the length of hospital stay.

The following is the recommended provision of clerkship tools, such as the standardized clerkship guide and equipment for patient examination, continuous education of health workers on clerkships and training them on how to use the available tools, the development of SOPs for patient clerkships, the promotion of clerkship culture and the supervision of health workers.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

A complete clerkship is the core upon which a medical diagnosis is made, and this depends on the patient’s medical history, the signs noticed on physical examination, and the results of laboratory investigations [ 1 ]. These sections of the clerkship should be completed carefully and appropriately to obtain a correct diagnosis; moreover, one part guides the next. A complete gynecological clerkship comprises the patient’s biodata, presenting complaint, history of presenting complaint, review of systems, past gynecological history, past obstetric history, past medical history, past surgical history, family history, social history, physical examination, laboratory investigation, diagnosis and management plan [ 2 , 3 ].

History taking, also known as medical interviews, is a brief personal inquiry and interrogation about bodily complaints by the doctor to the patient in addition to personal and social information about the patient [ 4 ]. It is estimated that 70-90% of a medical diagnosis can be determined by history alone [ 5 , 6 ]. Physical examination, in addition to the patient’s history, is equally important because it helps to discover more objective aspects of the disease [ 7 ]. The investigation of the patient should be guided by the findings that have been obtained on history taking and the physical examination [ 1 ].

Failure to establish a good complete and appropriate clerkship for patients leads to diagnostic uncertainties, which are associated with unfavorable outcomes. Some of the effects of poor clerkship include delayed diagnosis and inappropriate investigations, which lead to unnecessary expenditures on irrelevant tests and drugs and other effects, such as delayed recovery, prolonged inpatient stays, high costs of care and, at worst, death [ 8 , 9 ]. Despite health care workers receiving training in medical school about the relevance of physical examination, this has been poorly practiced and replaced with advanced imaging techniques such as ultrasounds, CT scans, and MRIs, which continue to make health care services unaffordable for most populations in developing countries [ 6 ]. In a study conducted to determine the prevalence and classification of misdiagnosis among hospitalized patients in five general hospitals in central Uganda, 9.2% of inpatients were misdiagnosed, and these were linked to inadequate medical history and examination, as the most common conditions were the most commonly misdiagnosed [ 9 ].

At Mbale RRH, there has been a progressive increase in the number of patients included in the gynecology department, which is expected to have compromised the quality of the clerkships that patients receive at the hospital [ 10 ]. However, there is limited information about the quality and completeness of clerkships for patients admitted to and treated at Mbale RRH. The current study therefore aimed to determine the gap in patient clerkships and the possible causes of these gaps and to suggest strategies for improving clerkships.

Methods and materials

Study design.

This was a baseline study, which was part of a quality improvement project aimed at improving the clerkships of patients admitted and treated at Mbale RRH. This mixed cross-sectional survey employing both quantitative and qualitative techniques was carried out from August 2022 to December 2022. Both techniques were employed to triangulate the results and address the gap in clerkship using quantitative techniques. Then, qualitative methods were used to explain the reasons for the observed discrepancy, and strategies to improve clerkship were suggested.

Study setting

The study was carried out in Mbale RRH, at the gynecologic ward. The hospital is in Mbale Municipal Council, 214 km to the east of the capital city of Kampala. It is the main regional referral hospital in the Elgon zone in eastern Uganda, a geographic area that borders the western part of Kenya. The Mbale RRH serves a catchment population of approximately 5 million people from 16 administrative districts. It is the referral hospital for the districts of Busia, Budaka, Kibuku, Kapchorwa, Bukwo, Butaleja, Manafwa, Mbale, Pallisa, Sironko and Tororo. The hospital is situated at an altitude of 1140 m within a range of 980–1800 m above sea level. Over 70% of inhabitants in this area are of Bantu ethnicity, and the great majority are part of rural agrarian communities. The Mbale RRH is a government-run, not-for-profit and charge-free 470-bed capacity that includes four major medical specialties: Obstetrics and Gynecology, Surgery, Internal Medicine, and Pediatrics and Child Health.

Study population, sample size and sampling strategy

We collected the files of patients who were admitted to the gynecology ward at Mbale RRH from August 2022 to December 2022. All the files were selected for review. We also interviewed health workers involved in patient clerkships at the gynecological ward. For qualitative data, participants were recruited until data saturation was reached.

Data collection

We collected both secondary and primary data. Secondary data were collected by reviewing the patients’ files. We identified research assistants who were trained in the data entry process. The data collection tool on Google Forms was distributed to the gadgets that were given to the assistants to enter the data. The qualitative data collection was performed via key informant interviews of the health workers involved in the clerkship of the patients, and the interviews were performed by the investigators. The selection of the participants was purposive, as we opted for those who clerk patients. After providing informed consent, the interview proceeded, with a voice recorder used to capture the data collected during the interview process and brief key notes made by the interviewer.

Data collection tool

A data abstraction tool was developed and fed into Google Forms, which were used to collect information about patients’ clerkships from patients’ files. The tool was developed by the investigators based on the requirements of a full clerkship, and it acted as a checklist for the parameters of clerkships that were provided or not provided. The validity of this tool was first determined by using it to collect information from ten patients’ files, which were not included in the study, and the tool was adjusted accordingly. The tool for collecting the qualitative information was an interview guide that was developed by the interviewer and was piloted with two health workers. Then, the guide was adjusted before it was used for data collection.

Variable handling

The dependent variable in the current study was the length of hospital stay. This was calculated from the date of admission and the date of discharge. There were two outcomes: “prolonged hospital stay” and “not prolonged”. A prolonged hospital stay was defined as a hospital stay of more than the 75 th percentile, according to a study conducted in Ethiopia [ 9 ]. This duration was more than 5 (five) days in the current study. The independent variables were the components of the clerkship.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using STATA version 15. Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed. Continuous variables were summarized using measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion, while categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and proportions. Bivariate analysis was performed using chi-square or Fischer’s exact tests, one-way ANOVA and independent t tests, with the level of significance determined by a p value of <= 0.2. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression, and the level of significance was determined by a p value of <=0.05.

Qualitative data were analyzed using Atlas Ti version 9 via deductive thematic analysis. The audio recordings were transcribed, and the transcripts were then imported into Atlas Ti.

Qualitative

The files of a total of 612 patients were reviewed.

The gap in the clerkships of patients

Patient biodata.

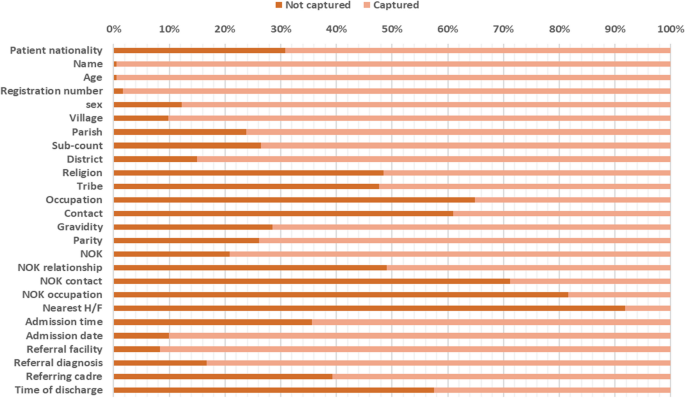

As shown in Fig. 1 below, at least one parameter under patient biodata was recorded for all the patients. The largest gap was identified in the recording of the nearest health facility of the patient, where 91% of the patients did not have this recorded, and the smallest gap was in the recording of the name and age, where less than 1% had this not recorded.

The gap in patients’ biodata

Compliance, HPC and ROS

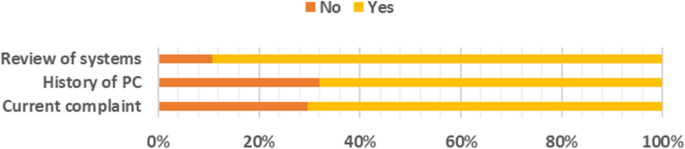

As shown in Fig. 2 below, the largest gap here was in recording the history of presenting complaint, which was not recorded in 32% of the participants. The least gap was in the review of systems, where it was not recorded in only 10% of the patients.

Gap in the presenting of complaints, HPCs and ROS

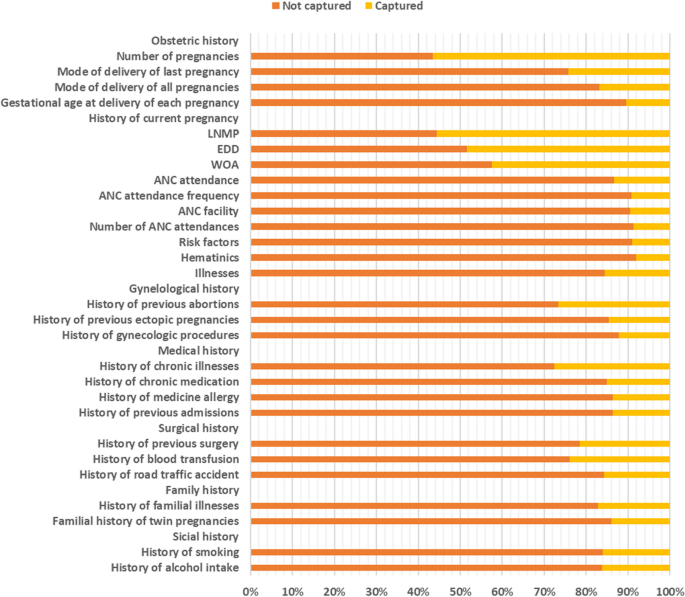

As shown in Fig. 3 below, the past obstetric history had the greatest gap in recording the gestational age at delivery of each pregnancy (89% not recorded), while the least gap was in recording the number of pregnancies (43% not recorded). In terms of the history of current pregnancy, the greatest gap was in recording whether hematinics were given to the mother (92% not recorded), while the least gap was in recording the date of the first day of the last normal menstrual period (LNMP) (44% not recorded). On other gynecological history, the largest gap was in recording the history of gynecological procedures (88% not recorded), while the least gap was in the history of abortions (73% not recorded). In the past medical history, the largest gap was in terms of history of medication allergies and history of previous admissions (86% not recorded), and the smallest gap was in terms of history of chronic illnesses (72% not recorded). In the past surgical history, the largest gap was in the history of trauma (84% not recorded), while the least gap was in the history of blood transfusion (76% not recorded). In terms of family history, there was a greater gap in the family history of twin pregnancies (86% not recorded) than in the family history of familial illnesses (83% not recorded). In terms of social history, neither alcohol intake nor smoking were recorded for 84% of the patients.

Gap in history

Physical examination

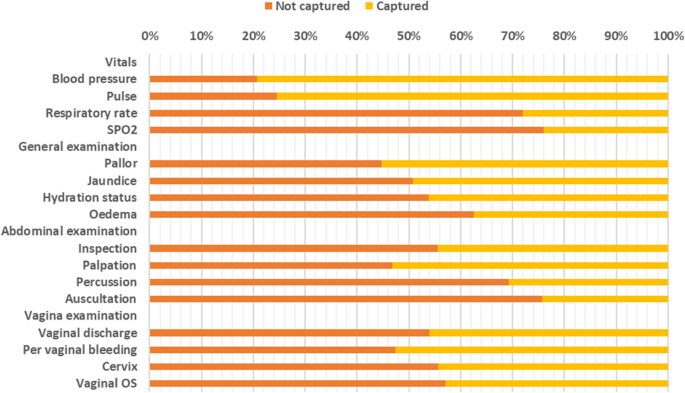

As shown in Fig. 4 below, the least recorded vital sign was oxygen saturation (SPO2), with 76% of the patients’ SPO2 not being recorded, while blood pressure was least recorded (21% not recorded). On the general examination, checking for edema had the greatest gap (63% not recorded), while checking for pallor had the least gap (45% not recorded). On abdominal examination, auscultation had the greatest gap (76% not recorded), while inspection of the abdomen had the least gap (56% not recorded). On vaginal examination, the greatest difference was in examining the vaginal OS (57% not recorded), while the least difference was in checking for vaginal bleeding (47% not recorded).

Gap in physical examination

Investigations, provisional diagnosis and management plan

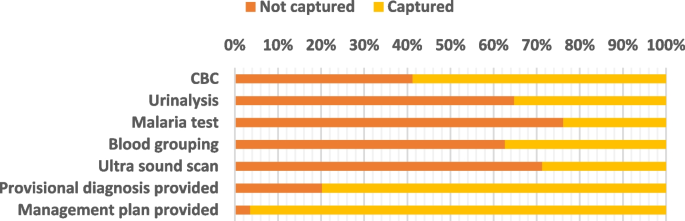

As shown in Fig. 5 below, the least common investigation was the malaria test (76% not performed), while the most common investigation was the CBC test (41% not performed). Provisional diagnosis was not performed in 20% of the patients. A management plan was not provided for approximately 4-5 of the patients.

Gap in the provisional diagnosis and management plan

Summary of the gap in clerkships

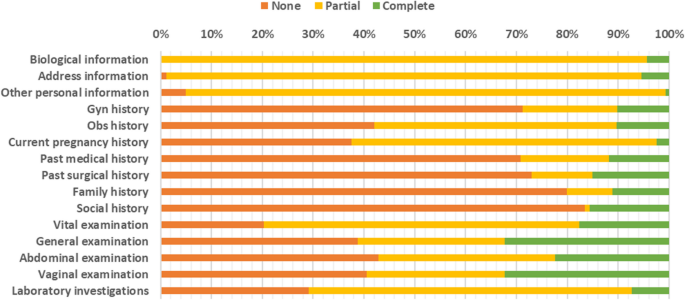

As shown in Fig. 6 below, most participants had a social history with no information provided at all, while biodata and vital sign examinations had the least number of participants with no information provided at all. There was no patient who had a complete clerkship.

Summary of the gaps in clerkships

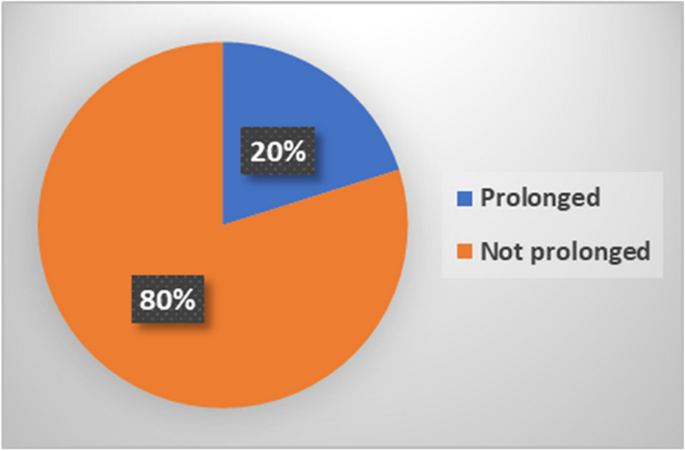

Days of hospitalization

The days of hospitalization were not normally distributed and were positively skewed, with a median of 3 [ 2 , 5 ] days. The mean days of hospitalization was 6.2 (±11.1). As shown in Fig. 7 below, 20% of the patients had prolonged hospitalization.

Duration of hospitalization

The effect of the clerkship gap on the number of days of hospital stay

As shown in Tables 1 and 2 below, the clerkship components that had a significant association with the days of hospitalization at the bivariate level included vital examination, abdominal examination, history of presenting complaint and treatment plan.

As shown in Table 3 , the only clerkship component that had a significant association with the days of hospitalization at the multivariate level was abdominal examination. People who had partial abdominal examinations were 1.9 times more likely to have prolonged hospital stays than those who had complete abdominal examinations.

Qualitative results

We conducted a total of 8 key informant interviews with the following characteristics as shown in table 4 below.

The qualitative results are summarized in Table 5 below.

The quality of clerkships on wards

It was reported that both the quality and completeness of clerkships on the ward are poor.

“…most are not clerking fully the patients, just put in like biodata three items name, age address, then they go on the present complaint, diagnosis then treatment; patient clerkship is missing out some important information…” (KIISAMW 2)

It was, however, noted that the quality of a clerkship depends on several factors, such as who is clerking, how sick the patient is, the number of patients to be seen that particular day and the number of hours a person clerks.

“…so, the quality of clerkship is dependent on who is clerking but also how sick the patient is…” (KIIMO 3)

Which people usually clerk patients on the ward?

The following people were identified as those who clerking patients, midwives, medical students, junior house officers, medical officers and specialists.

“…everyone clerks patients here; nurses, midwives, doctors, medical students, specialists, everyone as long as you are a health care provider…” (KIIMO 2)

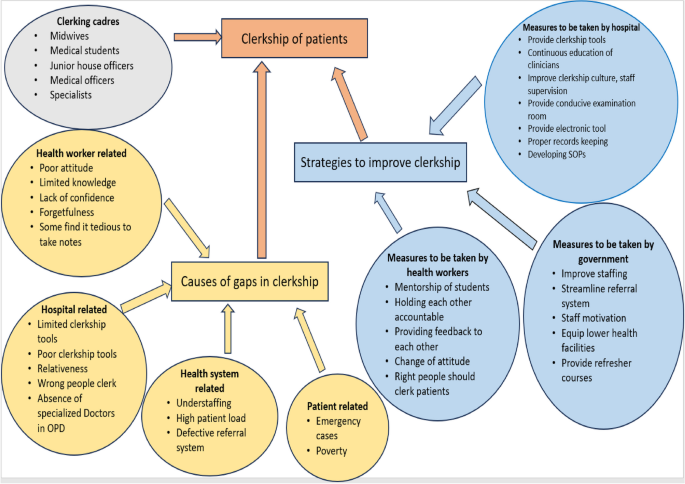

Causes of the gaps in clerkships

These factors were divided into factors related to health workers, hospital-related factors, health system-related factors and patient-related factors.

Hospital-related factors

The absence of clerkship tools such as a standardized clerkship guide and equipment for the examination of patients, such as blood pressure machines, thermometers, and glucometers, among others, were among the reasons for the poor clerkships of the patients.

…of course, there are other things like BP machines, thermometers; sometimes you want to examine a patient, but you don’t have those examining tools…” (KIIMO 1)

The tools that were available were plain, and they play little role in facilitating clerkships. They reported that they end up using small exercise books with no guidance for easy clerkship and with limited space.

“…most of our tools have these questions that are open ended and not so direct, so the person who is not so knowledgeable in looking out for certain things may miss out on certain data…” (KIIOG 1)

The reluctance of some health workers to clerk patients fully was also reported to be because it is the new normal, and everyone follows a bandwagon to collect only limited information from patients because there is no one to follow up or supervise.

“…you know when you go to a place, what you find people doing is what you also end up doing; I think it is because of what people are doing and no one is being held accountable for poor clerkship…” (KIIMO 3)

The absence of specialized doctors in the OPD department forces most patients, even stable patients, to be managed by the OPD to crowd the ward, making complete clerkships for all patients difficult. Poor triaging of the patients was also noted as one of the causes of poor clerkship, as emergency cases are mixed with stable cases.

“…and this gyn ward is supposed to see emergency gynecological cases, but you find even cases which are supposed to be in the gyn clinic are also here; so, it creates large numbers of people who need services…” (KIIMO 1)

Clerkships being performed by the wrong people were also noted. It was emphasized that it is only a medical doctor who can perform good clerkships for patients, and any other cadres who perform clerkships contribute to poor clerkships on the ward.

Health worker-related factors

A poor attitude of health workers was reported, and it was found that many health workers consider complete clerkship to be a practice that is performed by people who do not know what they look for to make a diagnosis.

A lack of knowledge about clerkships is another factor that has been reported. Some health workers were reported to forget some of the components of clerkship; hence, they end up recording only what they remember at the time of clerkship.

A lack of confidence by some health workers and students that creates fear of committing to making a diagnosis and drawing a management plan was reported to hinder some of them from doing a complete clerkship of the patients.

“…a nurse or a student may clerk, but they don’t know the diagnosis; so, they don’t want to commit themselves to a diagnosis…” (KIIMO 2)

Some health workers reported finding the process of taking notes while clerking tedious; hence, they collected only limited information that they could write within a short period of time.

Health system-related factors

Understaffing of the ward was noted to cause a low health worker-to-patient ratio. This overworked the health workers due to the large numbers of patients to be seen.

“…due to the thin human resource for health, many patients have to be seen by the same health worker, and it becomes difficult for one to clerk adequately; they tend to look out for key things majorly…” (KIIOG 1)

It was noted that in the morning or at the start of a shift, the clerkship can be fair, but as the day progresses, the quality of the clerkship decreases due to exhaustion.

“…you can’t clerk the person you are seeing at 5 pm the same way you clerked the person you saw at 9 am…” (KIIMO 3)

The large numbers of patients were also associated with other factors, such as the inefficient referral system, where patients who can be managed in lower health facilities are also referred to Mbale RRH. It was also stated that some patients do not understand the referral system, causing self-referral to the RRH. Other factors that contributed to the poor referral system were limited trust of the patients, drug stockouts, limited skilled number of health workers, and limited laboratory facilities in the lower health facilities.

“…so, everyone comes in from wherever they can, even unnecessary referrals from those lower health facilities make the numbers very high…” (KIIMO 1)

Patient-related factors

It was reported that the nature of some cases does not allow the health worker to collect all the information from such a patient, for example, the emergency cases. However, some responders stated the emergent nature of the cases to be a contributor to the complete clerkship of such a patient, as the person clerking such a case is more likely to call for help, so they must have enough information on the patient. Additionally, they do not want to fill the gap in the care of this critical patient.

“…usually, a more critical patient gets a more elaborate clerkship compared to a more stable one, where we will get something quick…” (KIIMO 3)

The poor health of some patients makes them unable to afford the files and books where clerkship notes are to be taken.

“…a patient has no money, and they have to buy books where to write, then you start writing on ten pages; does it make sense...” (KIIMO 2)

Strategies to improve patients’ clerkships

These were divided into measures to be taken by the health workers, those to be taken by the hospital leadership and those to be taken by the government.

Measures to be taken by health workers.

Holding each other accountable with respect to clerkship quality and completeness was suggested, including providing feedback from fellow health workers and from the records department.

…like everyone I think should just be held accountable for their clerkship and give each other feedback…” (KIIMO 3)

It was also suggested that medical students be mentored by senior doctors on the ward on the clerkship, and they should clerk the patients and present them to the senior doctors for guidance on the diagnosis and the management plan. This approach was believed to save time for senior doctors who may not have obtained time to collect information from patients and to facilitate the learning of students, most importantly ensuring the complete clerkship of patients.

“…students can give us a very good clerkship if supervised well, then we can discuss issues of diagnosis, the investigations to be done and the management…” (KIIMO 1)

Changes in the attitudes of health workers toward clerkships were suggested. This was also encouraged for those who work in laboratories to be able to perform the required investigations to guide diagnosis and management.

“…our lab has the equipment, but they need to change their attitude toward doing the investigations…” (KIIMO 1)

Measures to be taken by hospital leaders

The provision of tools to be used in clerkships was suggested as one of the measures that can be taken. Among the tools that were suggested include the following: a standardized clerkship guide, equipment for examination of the patients, such as blood pressure machines, and thermometers, among others. It was also suggested that a printer machine be used to print the clerkship guide to ensure the sustainability and availability of the tools. An electronic clerkship provision was suggested so that the amount of tedious paperwork could be reduced, especially for those who are comfortable with it.

“…if the stakeholders, especially those who have funds, can help us to make sure that these tools are always available, it is a starting point…” (KIIOG 1)

Continuous education of the clinicians about clerkships was suggested in the CMEs, and routine morning meetings were always held in the ward. Then, it was suggested that clinicians who clerked patients the best way are rewarded to motivate them.

“…for the staff, we can may be continuously talking about it during our Monday morning meetings about how to clerk well and the importance of clerking…” (KIIOG 1)

They also suggested providing a separate conducive room for the examination of patients to ensure the privacy of the patient, as this will ensure more detailed examination of the patients by the clinicians.

It was also suggested that more close supervision of the clerkship be performed and that a culture of good clerkship be developed to make clerkship a norm.

“…as leaders of the ward and of the department, we should not get tired to talk about the importance of clerkship, not only in this hospital but also in the whole country…” (KIIOG 1)

Proper record-keeping was also suggested, for people clerking to be assured that information will not be discarded shortly.

“…because how good is it to make these notes yet we can’t keep them properly...” (KIIMO 2)

It was also suggested that a records assistant be allocated to take notes for the clinicians to reduce their workload.

Coming up with SOPs, for example, putting different check points that ensure that a patient is fully clerked before the next step

“…we can say, before a patient accesses theater or before a mother enters second stage room, they must be fully clerked, and there is a checklist at that point…” (KIIOG 1)

Measures to be taken by the government

Improving the staffing level is strongly suggested to increase the health worker-to-patient ratio. This, they believed would reduce the workload off the health workers and allow them to give more time to the patients.

“…we also need more staffing for the scan because the person who is there is overwhelmed…” (KIIMO 1)

Staff motivation was encouraged through the enhancement of staff salaries and allowances. It was believed that it would be easy for these health workers to be supervised when they are motivated.

“…employ more health workers, pay them well then you can supervise them well…” (KIIMO 1)

Providing refresher courses to clinicians was also suggested so that they could be updated during the clerkship process.

Streamlining the referral system was also suggested through the use of lower health facilities so that some minor cases can be managed in those facilities to reduce the overcrowding of patients in the RRH.

“…we need to also streamline the referral system, the way people come to the RRH; some of these cases can be handled in the lower health facilities; we need to see only patients who have been referred…” (KIIMO 2)

The qualitative results are further summarized in Fig. 8 below.

Scheme of the clerkship of patients, including the causes of the clerkship gap and the strategies to improve the clerkship at Mbale RRH

Discussion of results

This study highlights a gap in the clerkships of patients admitted, treated, and discharged from the gynecological ward, with varying gaps in the different sections. This could be because some sections of the clerkship are considered more important than others. A study performed in Turkey revealed that physicians tended to record more information that aided their diagnostic tasks [ 11 ]. This is also reflected in the qualitative findings where participants expressed that particular information is required to make the diagnosis and not everything must be collected.

Biodata for patients were generally well recorded, and name and age were recorded for almost all the patients. A similar finding was found in the UK, where 100% of the patients had their personal details fully recorded [ 12 ]. Patient information should be carefully and thoroughly recorded because it enables health workers to create good rapport with patients and creates trust [ 13 ]. This information is also required for every interaction with the patient at the ward.

The presenting complaint, history of presenting complaint and the review of systems were fairly recorded, with each of them missing in less than 40% of the patients. The presence of a complaint is crucial in every interaction with the patient to the extent that a diagnosis can rarely be made without knowing the chief complaint [ 14 , 15 ]. This applies to the history of presenting complaint as well [ 16 ]. For the 30% who did not have the presenting complaint recorded, this could mean that even the patient’s primary problem was not given adequate attention.

In the history, the greatest gap was noted in the history of current pregnancy, where many parameters were not recorded in most patients. This is, however, expected since the study was conducted on a gynecological ward, where only a few pregnant women are expected to visit, as they are supposed to go to their antenatal clinics [ 17 ]. However, there was also a large gap in past gynecological history, which is expected to be fully explored in the gynecology ward. A good medical history is key to obtaining a good diagnosis, in addition to a good clinical examination [ 3 , 18 ]. Past obstetric history, past medical history, past surgical history, and family history also had large gaps, yet they are very important in the management of these patients.

The abdominal parameters, especially the pulse rate and blood pressure, were the least frequently recorded during the physical examination, and vital signs were most often recorded. However, there were substantial gaps in the general examination and vaginal examination. The least gap in vital sign examination is close monitoring, which is performed for most patients admitted to the ward due to the nature of the patients, some of whom are emergency patients [ 19 ].

Among the investigations, 29% of patients were not investigated. The least commonly performed investigations were pelvic USS and malaria tests, while complete blood count (CBC) was most commonly performed. Genital infections are among the most common reasons for women’s visits to health care facilities [ 20 ]. Therefore, most women in the gynecological ward are suspected to have genital tract infections, which could account for why CBC is most commonly performed.

The limited number of other investigations, such as pelvic ultrasound scans, underscore the relative contribution of medical history and physical examination to laboratory investigations and imaging studies aimed at making a diagnosis [ 1 ]. However, this would also highlight the system challenges of limited access to quality laboratory services in low- and middle-income countries [ 21 ]. This was also highlighted by one of the key informants who reported that the USS staff is available on some and not all days. This means that on days where the ultrasound department does not work, USS is not performed, even when needed.

We found that 20% of patients experienced prolonged hospitalization. This percentage is lower than the 24% reported in a study conducted in Ethiopia [ 22 ]. However, this study was conducted in a surgical ward. The median length of hospital stay was the same as that in a study conducted in Eastern Sudan among mothers following cesarean delivery [ 23 ]. A prolonged hospital stay has a negative impact not only on patients but also on the hospital [ 24 , 25 ]. Therefore, health systems should aim to reduce the length of hospital stay for patients as much as possible to improve the effectiveness of health services.

At the multivariate level, abdominal examination was significantly associated with length of hospital stay, with patients whose abdominal examination was not complete being more likely to have a prolonged hospital stay. This underscores the importance of good examination in the development of proper management plans that improve the care of patients, hence reducing the number of days of hospital stay [ 5 , 26 ].

There is a gap in the clerkships of patients at the gynecological ward, which is recognized by the stakeholders at the ward. Some components of clerkships were recorded better than others, with the reasoning that clerkships should be targeted. There were no patients who received a complete clerkship. There was a significant association between clerkships and the length of hospital stay. The causes of the gap in clerkships were multifactorial and included those related to the hospital, those related to the health worker, those related to the health care system and those related to the patient. The strategies to improve the clerkship of patients also included measures taken by health care workers, measures taken by hospitals and measures taken by the government.

Recommendations

Clerkship tools, such as the standardized clerkship guide and equipment for patient examination, were provided. The health workers were continuously educated on clerkships and trained on how to use the available tools. The development of SOPs for patient clerkships, the promotion of clerkship culture and the supervision of health workers.

Strengths of the study

A mixed study, therefore, allows for the triangulation of results.

Study limitations

The quantity of quantitative data collected, being secondary, is subject to bias due to documentation errors. We assessed the completeness of clerkship without considering the nature of patient admission. We did not record data on whether it was an emergency or stable case, which could be an important cofounder. However, this study gives a good insight into the status of clerkship in the gynecological ward and can lay foundation for future research into the subject.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials are available upon request from the corresponding author via the email provided.

Hampton JR, Harrison M, Mitchell JR, Prichard JS, Seymour C. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. Br Med J. 1975;2(5969):486.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kaufman MS, Holmes JS, Schachel PP, Latha G. Stead. First aid for the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. 2011.

Leis Potter. Gynecological history taking 2010 [Available from: https://geekymedics.com/gynaecology-history-taking/ .

Stoeckle JD, Billings JA. A history of history-taking: the medical interview. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2(2):119–27.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Muhrer JC. The importance of the history and physical in diagnosis. The Nurse Practitioner. 2014;39(4):30–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Foster DW. Every patient tells a story: medical mysteries and the art of diagnosis. J Clin Investig. 2010;120(1):4.

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Elder AT, McManus IC, Patrick A, Nair K, Vaughan L, Dacre J. The value of the physical examination in clinical practice: an international survey. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17(6):490–8.

Katongole SP, Anguyo RD, Nanyingi M, Nakiwala SR. Common medical errors and error reporting systems in selected Hospitals of Central Uganda. 2015.

Google Scholar

Katongole SP, Akweongo P, Anguyo R, Kasozi DE, Adomah-Afari A. Prevalence and Classification of Misdiagnosis Among Hospitalised Patients in Five General Hospitals of Central Uganda. Clin Audit. 2022;14:65–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/CA.S370393 .

Article Google Scholar

Kirinya A. Patients Overwhelm Mbale Regional Referral Hospital. 2022.

Yusuff KB, Tayo F. Does a physician’s specialty influence the recording of medication history in patients’ case notes? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(2):308–12.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wethers G, Brown J. Does an admission booklet improve patient safety? J Mental Health. 2011;20(5):438–44.

Flugelman MY. History-taking revisited: Simple techniques to foster patient collaboration, improve data attainment, and establish trust with the patient. GMS J Med Educ. 2021;38(6):Doc109.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gehring C, Thronson R. The Chief “Complaint” and History of Present Illness. In: Wong CJ, Jackson SL, editors. The Patient-Centered Approach to Medical Note-Writing. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 83–103.

Chapter Google Scholar

Virden TB, Flint M. Presenting Problem, History of Presenting Problem, and Social History. In: Segal DL, editor. Diagnostic Interviewing. New York: Springer US; 2019. p. 55-75.

Shah N. Taking a history: Introduction and the presenting complaint. BMJ. 2005;331(Suppl S3):0509314.

Uganda MOH. Essential Maternal and Newborn Clinical Care Guidelines for Uganda, May 2022. 2022.

Waller KC, Fox J. Importance of Health History in Diagnosis of an Acute Illness. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(6):e83–4.

Brekke IJ, Puntervoll LH, Pedersen PB, Kellett J, Brabrand M. The value of vital sign trends in predicting and monitoring clinical deterioration: a systematic review. PloS One. 2019;14(1):e0210875.

Mujuzi H, Siya A, Wambi R. Infectious vaginitis among women seeking reproductive health services at a sexual and reproductive health facility in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):677.

Nkengasong JN, Yao K, Onyebujoh P. Laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2018;391(10133):1873–5.

Fetene D, Tekalegn Y, Abdela J, Aynalem A, Bekele G, Molla E. Prolonged length of hospital stay and associated factors among patients admitted at a surgical ward in selected Public Hospitals Arsi Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2022. 2022.

Book Google Scholar

Hassan B, Mandar O, Alhabardi N, Adam I. Length of hospital stay after cesarean delivery and its determinants among women in Eastern Sudan. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:731–8.

LifePoint Health. The impact prolonged length of stay has on hospital financial performance. 2023. Retrieved from: https://lifepointhealth.net/insights-and-trends/the-impact-prolonged-length-of-stay-has-on-hospital-financialperformance .

Kelly S. Patient discharge delays pose threat to health outcomes, AHA warns. Healthcare Dive. 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/discharge-delay-American-Hospital-Association/638164/ .

Eskandari M, Alizadeh Bahmani AH, Mardani-Fard HA, Karimzadeh I, Omidifar N, Peymani P. Evaluation of factors that influenced the length of hospital stay using data mining techniques. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):1–11.

Download references

The study did not receive any funding

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health Science, Busitema University, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda

Kennedy Pangholi, Faith Nyangoma, Jesca Atugonza, Elizabeth Ajalo, Alice Kalenda, Ambrose Okibure, Andrew Kagwa, Ronald Kibuuka & Betty Nakawuka

Institute of Public Health Department of Community Health, Busitema University, faculty if Health Sciences, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda

Enid Kawala Kagoya, Francis Okello & Proscovia Auma

Seed Global Health, P.O. Box 124991, Kampala, Uganda

Allan G Nsubuga, Irene Atuhairwe, Prossy Nakattudde, Brian Agaba, Bonaventure Ahaisibwe, Esther Ijangolet & Eric Otim

Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Busitema University, Faculty of Health Science, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Busitema University, Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda

Julius Wandabwa & Milton Musaba

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mbale Regional Referral Hospital, P.O. Box 921, Mbale, Uganda

Antonina Webombesa & Kenneth Mugabe

Department of Nursing, Busitema University, Faculty of Health Sciences, P.O. Box 1460, Mbale, Uganda

Ashley Nakawuki

Ministry of Health, Plot 6, Lourdel Road, Nakasero, P.O. Box 7272, Kampala, Uganda

Richard Mugahi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.K came up with the concept and design of the work and coordinated the team to work K.E.K and A.P helped interpretation of the data O.F and O.A helped in the analysis of data N.A.G, A.I, N.P, W.P, W.J, M.M, A.W, M.K, N.F, A.J, A.E, M.R, K.A, K.A, A.B, A.B, I.E, O.E, N.A, K.R, N.B substantially revised the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kennedy Pangholi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and in line with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and Human Subject Protection. Prior to collecting the data, ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Mbale RRH, approval number MRRH-2023-300. The confidentiality of the participant information was ensured throughout the research process. Permission was obtained from the hospital administration before the data were collected from the patients’ files, and informed consent was obtained from the participants before the qualitative data were collected. After entry of the data, the devices were returned to the principal investigator at the end of the day, and they were given to the data entrants the next day.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. , rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pangholi, K., Kagoya, E.K., Nsubuga, A.G. et al. Improving Clerkship to Enhance Patients’ Quality of care (ICEPACQ): a baseline study. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 852 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11337-w

Download citation

Received : 25 September 2023

Accepted : 22 July 2024

Published : 26 July 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11337-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gynecology ward

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Analysis of tourism destination management strategies of angke kapuk mangrove nature tourism park as an ecotourism destination in North Jakarta to increase interest in returns

- Rosanto, S.

- Adinugroho, G.

Reduced tourist visitation have left the Angke Kapuk Mangrove Nature Tourist Park increasingly unkempt and degraded in supporting facilities. The lack of awareness and good management on the part of the organizers has resulted in a decline in the number of tourist visits to the Angke Kapuk Mangrove Nature Tourism Park. The aim of this research is to find out what management strategies are implemented in the Angke Kapuk Mangrove Nature Tourism Park area to increase tourist interest in returning to visit. This research method uses a qualitative descriptive research method. Researchers collect primary and secondary data through interviews, observation, and documentation. The analytical method used by researchers is the interactive model analysis method from Milles, Huberman, and Saldana which includes data condensation, data presentation, and drawing conclusions. Tourist interviews showed that the Angke Kapuk Mangrove Nature Tourism Park Area's management approach to protect the forest is still poor, where management in terms of facilities and cleanliness is very low and the level of awareness of tourists in maintaining cleanliness and hygiene. maintaining the available facilities is also very low, resulting in a lot of rubbish and damage to the various available facilities.

A qualitative analysis of male actors in amateur pornography: motivations, implications and challenges

- Open access

- Published: 30 July 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Tal Yaakobovitch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3400-4942 1 ,

- Moshe Bensimon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0008-035X 1 &

- Yael Idisis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7096-0758 1