ARTS & CULTURE

The surprising origin story of wonder woman.

The history of the comic-book superhero’s creation seven decades ago has been hidden away—until now

Jill Lepore

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/52/5c52beda-b4ef-4756-9e6f-77e0c7b8518f/oct14_g12_wonderwoman-1.jpg)

“Noted Psychologist Revealed as Author of Best-Selling ‘Wonder Woman,’” read the astonishing headline. In the summer of 1942, a press release from the New York offices of All-American Comics turned up at newspapers, magazines and radio stations all over the United States. The identity of Wonder Woman’s creator had been “at first kept secret,” it said, but the time had come to make a shocking announcement: “the author of ‘Wonder Woman’ is Dr. William Moulton Marston, internationally famous psychologist.” The truth about Wonder Woman had come out at last.

Or so, at least, it was made to appear. But, really, the name of Wonder Woman’s creator was the least of her secrets.

Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. Aside from Superman and Batman, no other comic-book character has lasted as long. Generations of girls have carried their sandwiches to school in Wonder Woman lunchboxes. Like every other superhero, Wonder Woman has a secret identity. Unlike every other superhero, she also has a secret history.

In one episode, a newspaper editor named Brown, desperate to discover Wonder Woman’s past, assigns a team of reporters to chase her down; she easily escapes them. Brown, gone half mad, is committed to a hospital. Wonder Woman disguises herself as a nurse and brings him a scroll. “This parchment seems to be the history of that girl you call ‘Wonder Woman’!” she tells him. “A strange, veiled woman left it with me.” Brown leaps out of bed and races back to the city desk, where he cries out, parchment in hand, “Stop the presses! I’ve got the history of Wonder Woman!” But Wonder Woman’s secret history isn’t written on parchment. Instead, it lies buried in boxes and cabinets and drawers, in thousands of documents, housed in libraries, archives and collections spread all over the United States, including the private papers of creator Marston—papers that, before I saw them, had never before been seen by anyone outside of Marston’s family.

The veil that has shrouded Wonder Woman’s past for seven decades hides beneath it a crucial story about comic books and superheroes and censorship and feminism. As Marston once put it, “Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who, I believe, should rule the world.”

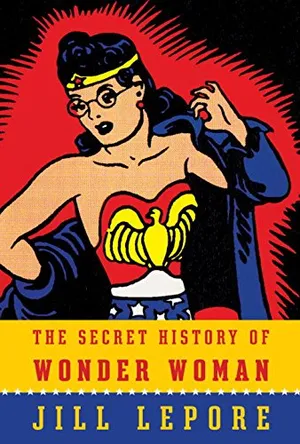

The Secret History of Wonder Woman

A riveting work of historical detection revealing that the origins of one of the world's most iconic superheroes hides within it a fascinating family story-and a crucial history of twentieth-century feminism Wonder Woman

Comic books were more or less invented in 1933 by Maxwell Charles Gaines, a former elementary school principal who went on to found All-American Comics. Superman first bounded over tall buildings in 1938. Batman began lurking in the shadows in 1939. Kids read them by the piles. But at a time when war was ravaging Europe, comic books celebrated violence, even sexual violence. In 1940, the Chicago Daily News called comics a “national disgrace.” “Ten million copies of these sex-horror serials are sold every month,” wrote the newspaper’s literary editor, calling for parents and teachers to ban the comics, “unless we want a coming generation even more ferocious than the present one.”

To defend himself against critics, Gaines, in 1940, hired Marston as a consultant. “‘Doc’ Marston has long been an advocate of the right type of comic magazines,” he explained. Marston held three degrees from Harvard, including a PhD in psychology. He led what he called “an experimental life.” He’d been a lawyer, a scientist and a professor. He is generally credited with inventing the lie detector test: He was obsessed with uncovering other people’s secrets. He’d been a consulting psychologist for Universal Pictures. He’d written screenplays, a novel and dozens of magazine articles. Gaines had read about Marston in an article in Family Circle magazine. In the summer of 1940, Olive Richard, a staff writer for the magazine, visited Marston at his house in Rye, New York, to ask him for his expert opinion about comics.

“Some of them are full of torture, kidnapping, sadism, and other cruel business,” she said.

“Unfortunately, that is true,” Marston admitted, but “when a lovely heroine is bound to the stake, comics followers are sure that the rescue will arrive in the nick of time. The reader’s wish is to save the girl, not to see her suffer.”

Marston was a man of a thousand lives and a thousand lies. “Olive Richard” was the pen name of Olive Byrne, and she hadn’t gone to visit Marston—she lived with him. She was also the niece of Margaret Sanger, one of the most important feminists of the 20th century. In 1916, Sanger and her sister, Ethel Byrne, Olive Byrne’s mother, had opened the first birth-control clinic in the United States. They were both arrested for the illegal distribution of contraception. In jail in 1917, Ethel Byrne went on a hunger strike and nearly died.

Olive Byrne met Marston in 1925, when she was a senior at Tufts; he was her psychology professor. Marston was already married, to a lawyer named Elizabeth Holloway. When Marston and Byrne fell in love, he gave Holloway a choice: either Byrne could live with them, or he would leave her. Byrne moved in. Between 1928 and 1933, each woman bore two children; they lived together as a family. Holloway went to work; Byrne stayed home and raised the children. They told census-takers and anyone else who asked that Byrne was Marston’s widowed sister-in-law. “Tolerant people are the happiest,” Marston wrote in a magazine essay in 1939, so “why not get rid of costly prejudices that hold you back?” He listed the “Six Most Common Types of Prejudice.” Eliminating prejudice number six—“Prejudice against unconventional people and non-conformists”—meant the most to him. Byrne’s sons didn’t find out that Marston was their father until 1963—when Holloway finally admitted it—and only after she extracted a promise that no one would raise the subject ever again.

Gaines didn’t know any of this when he met Marston in 1940 or else he would never have hired him: He was looking to avoid controversy, not to court it. Marston and Wonder Woman were pivotal to the creation of what became DC Comics. (DC was short for Detective Comics , the comic book in which Batman debuted.) In 1940, Gaines decided to counter his critics by forming an editorial advisory board and appointing Marston to serve on it, and DC decided to stamp comic books in which Superman and Batman appeared with a logo, an assurance of quality, reading, “A DC Publication.” And, since “the comics’ worst offense was their blood-curdling masculinity,” Marston said, the best way to fend off critics would be to create a female superhero.

“Well, Doc,” Gaines said, “I picked Superman after every syndicate in America turned it down. I’ll take a chance on your Wonder Woman! But you’ll have to write the strip yourself.”

In February 1941, Marston submitted a draft of his first script, explaining the “under-meaning” of Wonder Woman’s Amazonian origins in ancient Greece, where men had kept women in chains, until they broke free and escaped. “The NEW WOMEN thus freed and strengthened by supporting themselves (on Paradise Island) developed enormous physical and mental power.” His comic, he said, was meant to chronicle “a great movement now under way—the growth in the power of women.”

Wonder Woman made her debut in All-Star Comics at the end of 1941 and on the cover of a new comic book, Sensation Comics , at the beginning of 1942, drawn by an artist named Harry G. Peter. She wore a golden tiara, a red bustier, blue underpants and knee-high, red leather boots. She was a little slinky; she was very kinky. She’d left Paradise to fight fascism with feminism, in “America, the last citadel of democracy, and of equal rights for women!”

It seemed to Gaines like so much good, clean, superpatriotic fun. But in March 1942, the National Organization for Decent Literature put Sensation Comics on its blacklist of “Publications Disapproved for Youth” for one reason: “Wonder Woman is not sufficiently dressed.”

Gaines decided he needed another expert. He turned to Lauretta Bender, an associate professor of psychiatry at New York University’s medical school and a senior psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital, where she was director of the children’s ward, an expert on aggression. She’d long been interested in comics but her interest had grown in 1940, after her husband, Paul Schilder, was killed by a car while walking home from visiting Bender and their 8-day-old daughter in the hospital. Bender, left with three children under the age of 3, soon became painfully interested in studying how children cope with trauma. In 1940, she conducted a study with Reginald Lourie, a medical resident under her supervision, investigating the effect of comics on four children brought to Bellevue Hospital for behavioral problems. Tessie, 12, had witnessed her father, a convicted murderer, kill himself. She insisted on calling herself Shiera, after a comic-book girl who is always rescued at the last minute by the Flash. Kenneth, 11, had been raped. He was frantic unless medicated or “wearing a Superman cape.” He felt safe in it—he could fly away if he wanted to—and “he felt that the cape protected him from an assault.” Bender and Lourie concluded the comic books were “the folklore of this age,” and worked, culturally, the same way fables and fairy tales did.

That hardly ended the controversy. In February 1943, Josette Frank, an expert on children’s literature, a leader of the Child Study Association and a member of Gaines’ advisory board, sent Gaines a letter, telling him that while she’d never been a fan of Wonder Woman, she felt she now had to speak out about its “sadistic bits showing women chained, tortured, etc.” She had a point. In episode after episode, Wonder Woman is chained, bound, gagged, lassoed, tied, fettered and manacled. “Great girdle of Aphrodite!” she cries at one point. “Am I tired of being tied up!”

The story behind the writing and editing of Wonder Woman can be pieced together from Bender’s papers, at Brooklyn College; Frank’s papers, at the University of Minnesota; and Marston’s editorial correspondence, along with a set of original scripts, housed at the Dibner Library at the Smithsonian Institution Libraries. In his original scripts, Marston described scenes of bondage in careful, intimate detail with utmost precision. For a story about Mars, the God of War, Marston gave Peter elaborate instructions for the panel in which Wonder Woman is taken prisoner:

“Closeup, full length figure of WW. Do some careful chaining here—Mars’s men are experts! Put a metal collar on WW with a chain running off from the panel, as though she were chained in the line of prisoners. Have her hands clasped together at her breast with double bands on her wrists, her Amazon bracelets and another set. Between these runs a short chain, about the length of a handcuff chain—this is what compels her to clasp her hands together. Then put another, heavier, larger chain between her wrist bands which hangs in a long loop to just above her knees. At her ankles show a pair of arms and hands, coming from out of the panel, clasping about her ankles. This whole panel will lose its point and spoil the story unless these chains are drawn exactly as described here.”

Later in the story, Wonder Woman is locked in a cell. Straining to overhear a conversation in the next room, through the amplification of “bone conduction,” she takes her chain in her teeth: “Closeup of WW’s head shoulders. She holds her neck chain between her teeth. The chain runs taut between her teeth and the wall, where it is locked to a steel ring bolt.”

Gaines forwarded Frank’s letter of complaint to Marston. Marston shrugged it off. But then Dorothy Roubicek, who helped edit Wonder Woman—the first woman editor at DC Comics—objected to Wonder Woman’s torture, too.

“Of course I wouldn’t expect Miss Roubicek to understand all this,” Marston wrote Gaines. “After all I have devoted my entire life to working out psychological principles. Miss R. has been in comics only 6 months or so, hasn’t she? And never in psychology.” But “the secret of woman’s allure,” he told Gaines, is that “women enjoy submission—being bound.”

Gaines was troubled. Roubicek, who worked on Superman, too, had invented kryptonite. She believed superheroes ought to have vulnerabilities. She told Gaines she thought Wonder Woman ought to be more like Superman and, just as Superman couldn’t go back to the planet Krypton, Wonder Woman ought not to be able to go back to Paradise Island, where the kinkiest stuff tended to happen. Gaines then sent Roubicek to Bellevue Hospital to interview Bender. In a memo to Gaines, Roubicek reported that Bender “does not believe that Wonder Woman tends to masochism or sadism.” She also liked the way Marston was playing with feminism, Roubicek reported: “She believes that Dr. Marston is handling very cleverly this whole ‘experiment’ as she calls it. She feels that perhaps he is bringing to the public the real issue at stake in the world (and one which she feels may possibly be a direct cause of the present conflict) and that is that the difference between the sexes is not a sex problem, nor a struggle for superiority, but rather a problem of the relation of one sex to the other.” Roubicek summed up: “Dr. Bender believes that this strip should be left alone.”

Gaines was hugely relieved, at least until September 1943, when a letter arrived from John D. Jacobs, a U.S. Army staff sergeant in the 291st Infantry, stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. “I am one of those odd, perhaps unfortunate men who derive an extreme erotic pleasure from the mere thought of a beautiful girl, chained or bound, or masked, or wearing extreme high-heels or high-laced boots,—in fact, any sort of constriction or strain whatsoever,” Jacobs wrote. He wanted to know whether the author of Wonder Woman himself had in his possession any of the items depicted in the stories, “the leather mask, or the wide iron collar from Tibet, or the Greek ankle manacle? Or do you just ‘dream up’ these things?”

(For the record, Marston and Olive Byrne’s son, Byrne Marston, who is an 83-year-old retired obstetrician, thinks that when Marston talked about the importance of submission, he meant it only metaphorically. “I never saw anything like that in our house,” he told me. “He didn’t tie the ladies up to the bedpost. He’d never have gotten away with it.”)

Gaines forwarded Jacobs’ letter to Marston, with a note: “This is one of the things I’ve been afraid of.” Something had to be done. He therefore enclosed, for Marston’s use, a memo written by Roubicek containing a “list of methods which can be used to keep women confined or enclosed without the use of chains. Each one of these can be varied in many ways—enabling us, as I told you in our conference last week, to cut down the use of chains by at least 50 to 75% without at all interfering with the excitement of the story or the sales of the books.”

Marston wrote Gaines right back.

“I have the good Sergeant’s letter in which he expresses his enthusiasm over chains for women—so what?” As a practicing clinical psychologist, he said, he was unimpressed. “Some day I’ll make you a list of all the items about women that different people have been known to get passionate over—women’s hair, boots, belts, silk worn by women, gloves, stockings, garters, panties, bare backs,” he promised. “You can’t have a real woman character in any form of fiction without touching off a great many readers’ erotic fancies. Which is swell, I say.”

Marston was sure he knew what line not to cross. Harmless erotic fantasies are terrific, he said. “It’s the lousy ones you have to look out for—the harmful, destructive, morbid erotic fixations—real sadism, killing, blood-letting, torturing where the pleasure is in the victim’s actual pain, etc. Those are 100 per cent bad and I won’t have any part of them.” He added, in closing, “Please thank Miss Roubicek for the list of menaces.”

In 1944, Gaines and Marston signed an agreement for Wonder Woman to become a newspaper strip, syndicated by King Features. Busy with the newspaper strip, Marston hired an 18-year-old student, Joye Hummel, to help him write comic-book scripts. Joye Hummel, now Joye Kelly, turned 90 this April; in June, she donated her collection of never-before-seen scripts and comic books to the Smithsonian Libraries. Hiring her helped with Marston’s editorial problem, too. Her stories were more innocent than his. She’d type them and bring them to Sheldon Mayer, Marston’s editor at DC, she told me, and “He always OK’d mine faster because I didn’t make mine as sexy.” To celebrate syndication, Gaines had his artists draw a panel in which Superman and Batman, rising out of the front page of a daily newspaper, call out to Wonder Woman, who’s leaping onto the page, “Welcome, Wonder Woman!”

Gaines had another kind of welcome to make, too. He asked Lauretta Bender to take Frank’s place on the editorial advisory board.

In an ad King Features ran to persuade newspapers to purchase the strip, pointing out that Wonder Woman already had “ten million loyal fans,” her name is written in rope.

Hidden behind this controversy is one reason for all those chains and ropes, which has to do with the history of the fight for women’s rights. Because Marston kept his true relationship with Olive Byrne a secret, he kept his family’s ties to Margaret Sanger a secret, too. Marston, Byrne and Holloway, and even Harry G. Peter, the artist who drew Wonder Woman, had all been powerfully influenced by the suffrage, feminism and birth control movements. And each of those movements had used chains as a centerpiece of its iconography.

In 1911, when Marston was a freshman at Harvard, the British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, who’d chained herself to the gates outside 10 Downing Street, came to speak on campus. When Sanger faced charges of obscenity for explaining birth control in a magazine she founded called the Woman Rebel, a petition sent to President Woodrow Wilson on her behalf read, “While men stand proudly and face the sun, boasting that they have quenched the wickedness of slavery, what chains of slavery are, have been or ever could be so intimate a horror as the shackles on every limb—on every thought—on the very soul of an unwilling pregnant woman?” American suffragists threatened to chain themselves to the gates outside the White House. In 1916, in Chicago, women representing the states where women had still not gained the right to vote marched in chains.

In the 1910s, Peter was a staff artist at the magazine Judge , where he contributed to its suffrage page called “The Modern Woman,” which ran from 1912 to 1917. More regularly, the art on that page was drawn by another staff artist, a woman named Lou Rogers. Rogers’ suffrage and feminist cartoons very often featured an allegorical woman chained or roped, breaking her bonds. Sanger hired Rogers as art director for the Birth Control Review , a magazine she started in 1917. In 1920, in a book called Woman and the New Race , Sanger argued that woman “had chained herself to her place in society and the family through the maternal functions of her nature, and only chains thus strong could have bound her to her lot as a brood animal.” In 1923, an illustration commissioned by Rogers for the cover of Birth Control Review pictured a weakened and desperate woman, fallen to her knees and chained at the ankle to a ball that reads, “UNWANTED BABIES.” A chained woman inspired the title of Sanger’s 1928 book, Motherhood in Bondage , a compilation of some of the thousands of letters she had received from women begging her for information about birth control; she described the letters as “the confessions of enslaved mothers.” When Marston created Wonder Woman, in 1941, he drew on Sanger’s legacy and inspiration. But he was also determined to keep the influence of Sanger on Wonder Woman a secret.

He took that secret to his grave when he died in 1947. Most superheroes didn’t survive peacetime and those that did were changed forever in 1954, when a psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent and testified before a Senate subcommittee investigating the comics. Wertham believed that comics were corrupting American kids, and turning them into juvenile delinquents. He especially disliked Wonder Woman. Bender had written that Wonder Woman comics display “a strikingly advanced concept of femininity and masculinity” and that “women in these stories are placed on an equal footing with men and indulge in the same type of activities.” Wertham found the feminism in Wonder Woman repulsive.

“As to the ‘advanced femininity,’ what are the activities in comic books which women ‘indulge in on an equal footing with men’? They do not work. They are not homemakers. They do not bring up a family. Mother-love is entirely absent. Even when Wonder Woman adopts a girl there are Lesbian overtones,” he said. At the Senate hearings, Bender testified, too. If anything in American popular culture was bad for girls, she said, it wasn’t Wonder Woman; it was Walt Disney. “The mothers are always killed or sent to the insane asylums in Walt Disney movies,” she said. This argument fell on deaf ears.

Wertham’s papers, housed at the Library of Congress, were only opened to researchers in 2010. They suggest that Wertham’s antipathy toward Bender had less to do with the content of the comics than with professional rivalry. (Paul Schilder, Bender’s late husband, had been Wertham’s boss for many years.) Wertham’s papers contain a scrap on which he compiled a list he titled “Paid Experts of the Comic Book Industry Posing as Independent Scholars.” First on the list as the comic book industry’s number one lackey was Bender, about whom Wertham wrote: “Boasted privately of bringing up her 3 children on money from crime comic books.”

In the wake of the 1954 hearings, DC Comics removed Bender from its editorial advisory board, and the Comics Magazine Association of America adopted a new code. Under its terms, comic books could contain nothing cruel: “All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.” There could be nothing kinky: “Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.” And there could be nothing unconventional: “The treatment of love-romance stories shall emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.”

“Anniversary, which we forgot entirely,” Olive Byrne wrote in her secret diary in 1936. (The diary remains in family hands.) During the years when she lived with Marston and Holloway, she wore, instead of a wedding ring, a pair of bracelets. Wonder Woman wears those same cuffs. Byrne died in 1990, at the age of 86. She and Holloway had been living together in an apartment in Tampa. While Byrne was in the hospital, dying, Holloway fell and broke her hip; she was admitted to the same hospital. They were in separate rooms. They’d lived together for 64 years. When Holloway, in her hospital bed, was told that Byrne had died, she sang a poem by Tennyson: “Sunset and the evening star, / And one clear call for me! / And may there be no moaning of the bar, / When I put out to sea.” No newspaper ran an obituary.

Elizabeth Holloway Marston died in 1993. An obituary ran in the New York Times. It was headed, “Elizabeth H. Marston, Inspiration for Wonder Woman, 100.” This was, at best, a half-truth.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Jill Lepore | READ MORE

Jill Lepore is a staff writer at the New Yorker and the David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard University. Lepore is the author of Book of Ages , New York Burning and The Secret History of Wonder Woman .

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Origin in the Golden Age

The silver age and television success.

- Post- Crisis Wonder Woman and film success

What does Wonder Woman do?

What is the movie wonder woman 1984 about, when did wonder woman first appear.

- When did Batman first appear in DC Comics?

- When did Wonder Woman first appear in DC Comics?

Wonder Woman

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction - Wonder Woman

- Wonder Woman - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Who is Wonder Woman?

Wonder Woman is an American comic book heroine created for DC Comics by psychologist William Moulton Marston (under the pseudonym Charles Moulton) and artist Harry G. Peter.

How did Wonder Woman get her powers?

Wonder Woman is an Amazon , a race of female warriors in Greek mythology . For the purpose of the Wonder Woman character, it was the Greek gods who gave her her powers. These powers include superhuman strength and speed as well as the ability to fly.

Wonder Woman is a powerful leader and warrior. Her strength, speed, near invulnerability to physical harm, and equipment (particularly her golden lasso) make her a strong character. She is part of the DC “trinity,” along with Batman and Superman , and is a founder of the Justice League, humanity’s defense against powerful threats.

In the film Wonder Woman 1984 , Wonder Woman ( Gal Gadot ) encounters the Dreamstone. The Dreamstone is a dangerous artifact that grants one wish per person and has led to the collapse of past civilizations. In an attempt to save the world, Wonder Woman has to contend with Maxwell Lord (Pedro Pascal) and Cheetah ( Kristen Wiig ).

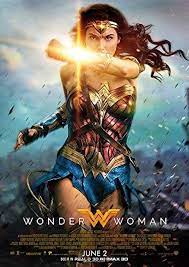

Wonder Woman first appeared in 1941, in a backup story in All Star Comics no. 8. The character received fuller treatment in Sensation Comics no. 1 (January 1942) and Wonder Woman no. 1 (June 1942). Lynda Carter starred as Wonder Woman in a live-action TV show that aired from 1975 to 1979. Gal Gadot later played the character in movies, beginning in 2017.

Wonder Woman , American comic book heroine created for DC Comics by psychologist William Moulton Marston (under the pseudonym Charles Moulton) and artist Harry G. Peter. Wonder Woman first appeared in a backup story in All Star Comics no. 8 (December 1941) before receiving fuller treatment in Sensation Comics no. 1 (January 1942) and Wonder Woman no. 1 (June 1942). She perennially ranked as one of DC’s most-recognizable characters and a feminist icon.

Marston was something of a maverick in the scientific community , and he is credited with inventing a precursor of the modern lie detector . He practiced polygyny , he believed that women would rise up to lead the world into a new and peaceful age, and one of Marston’s longtime partners was the niece of family-planning pioneer Margaret Sanger . These details, as well as Marston’s long affiliation with the women’s suffrage movement, were obvious influences in the creation of Wonder Woman.

The details of Wonder Woman’s origin have changed many times over the years, but the basic premise has remained largely the same. U.S. Air Force pilot Steve Trevor’s plane crashes on the uncharted Paradise Island, home of the legendary Amazons . The raven-haired Princess Diana finds Trevor, and the Amazons nurse him back to health. A tournament is held to determine who will take the pilot back to “Man’s World,” but Diana is forbidden to enter. Disguising herself, she engages in the games, winning them and being awarded the costume of Wonder Woman. Diana takes Trevor back to the United States in her invisible plane, and she adopts the secret identity of Diana Prince. As Prince, she soon becomes Trevor’s assistant, and Trevor—much like a gender-reversed Lois Lane—never realizes that his coworker and the superhero who consistently comes to his rescue are the same person.

In her first 40 years of adventures, Wonder Woman wore a distinctive red bodice with a gold eagle, a blue skirt with white stars (quickly replaced by blue shorts with stars), red boots with a white centre stripe and upper edge, a gold belt and tiara, and bracelets on each wrist. The bracelets could deflect bullets or other missiles, and hanging from her belt was a magic golden lasso, which compelled anyone bound by it to tell the truth or obey her commands. Among her powers were prodigious strength and speed, near invulnerability to physical harm, and formidable combat prowess. On some occasions, she also displayed the ability to converse with animals.

Wonder Woman was popular with readers for many reasons. For a nation engulfed in World War II , her unwavering patriotism was welcome. Male readers enjoyed the adventures of a scantily clad woman who was drawn in the style of one of Esquire magazine’s Varga Girl pinups and who was often tied up by male or female villains. Critics—most notably anti-comics polemicist Frederic Wertham—would call attention to the preponderance of bondage in Wonder Woman stories, but Marston claimed such scenes to be allusions to suffragist imagery. (This defense strained credibility, however, as the concept of “loving submission” to authority was pervasive throughout both Wonder Woman comics and Marston’s personal life.) Female readers liked the series because it presented a strong and confident woman who often spoke about the power of womanhood and the need for female solidarity. In an industry where superheroines tended to be used for cheesecake titillation or as adjuncts to their more powerful and popular male counterparts, Wonder Woman stood apart.

Unlike Superman or Batman , the other members of what would come to be known as DC’s “trinity,” Wonder Woman would never develop an especially memorable gallery of villains. Among her persistent foes were the catlike Cheetah, the towering Giganta, the sorceress Circe, and the telepath Dr. Psycho, whose mental powers were a sinister inversion of Marston’s “loving submission” credo. Besides appearing in her own two titles, Wonder Woman was a featured member of the Justice Society of America in the pages of All Star Comics .

Marston wrote Wonder Woman until his death in May 1947, with Peter providing the art during most of that time. Robert Kanigher succeeded Marston as writer in 1948, but the popularity of superhero comics had sharply declined in the postwar years. The heroine last appeared with the Justice Society in All Star Comics no. 57 (February 1951), and she was dropped from Sensation Comics after no. 106 (December 1951). Sensation was subsequently turned into a horror anthology to capitalize on that genre’s surging popularity, leaving her bimonthly series as the sole Wonder Woman title. Peter was replaced by artists Ross Andru and Mike Esposito, among others.

Kanigher had a flair for the outrageous, and he introduced many elements into the Wonder Woman mythos that rattled longtime readers. These included adventures featuring a younger Wonder Woman (as Wonder Girl and Wonder Tot), romantic suitors such as Merman and Birdman (and their youthful counterparts Mer-Boy and Bird-Boy), and bizarre villains like Angle Man, Paper-Man, and a sentient egg (and obvious “yellow peril” stereotype ) known as Egg Fu. Resistance from fans would lead Kanigher to take the unorthodox step of writing himself, Andru, and Esposito into Wonder Woman no. 158 (November 1965), so he could personally “fire” the supporting cast that he had introduced and restore Wonder Woman to her “Golden Age” roots.

Outside of her own title, Wonder Woman appeared as a founding member of the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold no. 28 (February-March 1960). In 1968 Kanigher left Wonder Woman , and creative duties were taken over by writer Denny O’Neil and artists Mike Sekowsky and Dick Giordano. In Wonder Woman no. 178 (October 1968), Diana Prince was stripped of her superpowers and costume, and she became an undercover adventure heroine in the model of Emma Peel from the television series The Avengers . Feminist leader Gloria Steinem featured the heroine in her classic costume on the cover of the July 1972 debut issue of Ms. magazine, and Wonder Woman’s profile grew dramatically during the 1970s. Shortly after her appearance in Ms. , Wonder Woman regained her powers and costume, and the classic depiction of the hero played a prominent role in ABC ’s hit animated series Super Friends (1973–86). In 1975 Lynda Carter debuted as the title character in the live action Wonder Woman . The statuesque former beauty queen so perfectly embodied the Amazon princess that, although the show ran for just three seasons, Carter would become the face of the character for a generation. Early scripts tended to be very faithful to the World War II-era comics, while later episodes, moving the time frame to the 1970s, were less faithful to their progenitors.

Pioneering the Future of AI-Enhanced Storytelling

Wonder Woman

A confident and exciting exploration of the power of female intuition over probability.

Within the context of a great narrative, few superhero movies deserve the title of God, let alone God-killer. Patty Jenkin's Wonder Woman surpasses each and every DC offering (and some Marvel offerings) since The Dark Knight so completely that it sets the standard for "female-driven" action/adventure.

To observe the slate of upcoming attractions attached to this blockbuster, one would think it a simple case of replacing the usual male lead with a female. Dress her up—make her bad ass—and suddenly you have a culturally "hip" female-friendly crowd pleaser.

Unfortunately, everyone instinctively sees through the ruse.

Wonder Woman , on the other hand, does far more than simply provide eye-candy in a skirt and boots. The film promotes a female approach to problem-solving , eschewing the predominantly male perspective of playing with the odds for something more definite. Something more concrete.

Running the film through the Dramatica theory of story provides a framework for a greater understanding of how they accomplished this monumental—and super important—feat.

NOTE: The following analysis provides numerous spoilers. If you haven't seen the film, we highly suggest you see it first, then return here after. Trust us…you'll love it!

The Wonder Woman

Diana, Princess of Themyscira and Daughter of Hippolyta (Gal Gadot), is more than royalty—she's a God. More specifically, she is a God-killer , a Universe her mother works hard to keep secret and one Diana only fully realizes during her final battle with Aries, the God of War ( Main Character Throughline of Universe ). Zeus sculpted Diana out of clay as a final gesture of love for mankind—fulfilling this Work represents her greatest personal Issue ( Main Character Issue of Work ).

The truly feminine characteristic Diana brings to this world, and one that those pandering to the Audience miss, is her Certainty that she is always on the right path ( Main Character Problem of Certainty . This knowing , often mistaken as "female intuition", motivates Diana to leap before she thinks, cross battlefields before ascertaining the odds, and—in sharp contrast to the positive aspects of this knowing—murder Ludendorff (Danny Huston) thinking him Aries ( Main Character Approach of Do-er ).

This final act challenges her resolve to stay true to her calling. While following her intuition saves the village, it also leads her to kill the wrong person. For a moment, her sense of knowing seems to fail her and Aries—representing the ultimate male perspective—steps in to break her certainty down. Using Dr. Maru (Elena Anaya) as an example, Aries (David Thewlis) shows Diana the potential all humans possess for horror, demotivating her and manipulating her to change her approach ( Main Character Solution of Potential ). In fact, Aries manipulated the war itself into existence in order to get Diana to conceive of man's ultimate fallibility ( Story Consequence of Conceiving ).

And if it weren't for Steve Trevor's valiant act, she probably would have joined him.

Steve Trevor. Spy.

Steve Trevor (Chris Pine) challenges Diana throughout the narrative with his fixed belief that Gods aren't real, and that real men are capable of despicable horror ( Obstacle Character Throughline of Mind , Obstacle Character Concern of Conscious ). As Obstacle Character, Steve's play-it-safe attitude challenges Diana to question her own beliefs. Thinking himself "less" than the average man, minimizing conflict by playing yes-man to his generals, and even reducing Diana's status of Princess to just "Diana Prince " presents a completely foreign approach to solving problems ( Obstacle Character Problem of Reduction ).

Steve isn't the only man to think this way.

The generals themselves and the politicians in the backrooms work to minimize casualties and slowly reduce the enemy's capability of making war—an approach that only serves to extend and increase the ferocity of the atrocities ( Objective Story Problem of Reduction ).

Of Two Worlds

Diana and Steve develop a budding romance around the struggle to conceive of the other's world ( Relationship Story Concern of Conceiving ). Letting a clock tell you what to do, sleeping alone because you shouldn't lie with someone you're not married to, acknowledging their need for one another, and discussing the comical sexual deficiencies of the male species provide thematic context for their relationship ( Permission , Expediency , Need , and Deficiency —all Issues found within a Concern of Conceiving). Instigating that first step—whether it be on the boat, on the battlefield, or on the airfield at the end—drives them to come into conflict and eventually drives them towards the ultimate symbol of love ( Relationship Story Problem of Proaction —self-sacrifice).

The Final Solution

The development of their relationship eventually leads Steve to change his approach ( Obstacle Character Resolve Changed ). He confesses his love to Diana, gives her his watch as a symbol of altering his thinking towards the feminine, boards the airplane and destroys Maru's poison gas. By literally making a big scene, he tosses aside the male preference for probability over time and shows Diana what mankind truly deserves ( Obstacle Character Solution of Production ). This heroic act motivates Diana to reaffirm her initial intention and stand-up to defeat Aries once and for all ( Main Character Resolve of Steadfast ).

Subtle but Powerful Clarification

In a slight structural misstep that perhaps made its way in as a result of a more male-oriented understanding, Diana confirms her steadfastness to Aries by telling him: "It's not about what you deserve, it's about what you believe." Belief, or faith, is the Male understanding of Knowing. For Diana's line to truly resonate with the rest of the narrative, it should have read: "It's not about what you deserve, it's about what you know."

That knowing—that certainty that drives her to jump in without doubt and without second-guessing—that's the true power of the feminine hero. Faith is close—and works fine—but for a film that so eloquently encodes the feminine experience of problem-solving, an alignment with that intuition would affirm what so many are taught to ignore.

Resolution and Meaning

The story begins with the theft of Dr. Maru's book, turns with the discovery of Diana's island and the killing of General Luddendorf, and ends with the final destruction of Aries ( Story Driver of Action ). Diana's great show of force at the end confirms her intuition and fulfills the story's central concern of teaching Diana that mankind is worth fighting for ( Objective Story Solution of Production , Story Outcome of Success , and Story Goal of Learning ).

To say Wonder Woman is fantastic is an understatement. To say that it takes the plight of feminine understanding to the task of standing up against the forces of doubt and reduction is to honor its truest intentions. The unexplored chasm of knowing and certainty and "female intuition" deserves more than a girly costume and a gender attribution search and replace. It deserves a greater understanding and respect for its ability to save the world.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero .

Iconic Feminism: Narrative Analysis of Wonder Woman

"diana prince: what is a secretary etta candy: oh, well, i do everything. i go where he tells me to go, i do what he tells me to do. diana prince: well, where i'm from that's called slavery..

Diana Prince aka Wonder Woman has been a feminist icon since her first appearance in DC comics in 1941. Created by William Moultan Marston who had stated that he created her with “pedagogic intent”. (mettacuchi, p.122) The early portrayal of Wonder Woman was to be a model “biographical accounts of real-life “wonder women” like Susan B. Anthony and Joan of Arc to demonstrate to young female and male readers that female strength was not a fantastic supposition.” (p.122, Lavin) Wonder Woman was a symbol of women liberation and feminism. She is considered one of the first female superheroes and one of the most popular. The last 10 years Hollywood has seen a high demand of comic book superhero films. With this recent trend, Hollywood was bound to make a feature length film centered on this famous female superhero. In 2017, Warner Brothers production released the first live action Wonder Woman film, starring the beautiful Gal Gadot and directed by the prodigious director Patty Jenkins.

The film quickly became the highest grossing female lead action movie ever made with $821 million world wide. A female lead action film grossing this much movie has been unheard of in movie history. Female superheroes have along history of improper representation in the comic books and movies. Female superheroes go through major objectification and hyper-sexualization because of the main demographic being males. When hyper sexualization takes over a character that character is now scene as a object then a subject.

This study applies McClures reconceptualizing of Fishers Narrative Paradigm with highlight of identification to look into the feminist narrative of the film. Checking the narrative probability and fidelity will give us a indication that there are narratives in this film that will adhere to audience Identification. Then by applying feminist theory to the stories narratives we will be able to highlight the feminist values that are represented in the film.

70 Wonder Woman (2017)

Wonder Woman as a Sign of Feminism

by Alanna Martines

The classic DC comic we all know and love is brought to life in Wonder Woman (2017) starring Gal Gadot as the iconic Diana Prince, better known as Wonder Woman. The film serves as an origin story of the beloved hero and follows her journey as she steps into the outside world. Diana is portrayed as a strong, compassionate, determined, and willing to challenge traditional gender roles to become a symbol of female empowerment. The film explores themes of war, sacrifice, and the complexities we face as human beings. With the compelling storytelling and the impactful message, Wonder Woman has become a groundbreaking film, celebrating the strength and quality of women. The film uses its narrative and characters to shed light on DPD issues such as gender inequality, abuse of power, and discrimination. We will be taking a deep dive into the gender equality and feminism seen in Wonder Woman .

Wonder Woman stands as a powerful testament to female empowerment and representation. By showcasing the strength, courage, and compassion of its protagonist, the movie shattered gender stereotypes and celebrated the ideals of women. In a world where women have historically been treated as less than men, feminism emerged as a movement for women’s rights and equality. At the time of the movie, in January of 2017 there was a worldwide protest called The Women’s March. The march aimed to advocate legislation and policies regarding human rights and other issues. Ghaisani writes that “Women have been treated as lower than men ever since in the biological level ”. Throughout history, feminism has led to significant achievements, such as the right to vote and work. However, societal ideals of women, shaped predominantly by men, have persisted. This is particularly evident when examining portrayals of women in comic books, where they are often depicted in skimpy clothing and possess invisible powers, reinforcing traditional gender roles. Wonder Woman challenges these ideas by defying traditional stereotypes and featuring a lead actress from Israel, thereby improving the representation of feminism and women’s empowerment. Ghaisani writes that “Wonder Woman was firstly created by a man, psychologist William Moulton Marston. Even Marston portrays Wonder Woman as how the future ideal woman should be.” Marston believed that women possessed inherent qualities that made them superior to men in many ways.

Wonder Woman subverts the ideals of women by setting Princess Diana on an island where such traditional notions do not exist. The women on the island rely solely on themselves and do not require assistance from men. Cinematography techniques that are used are when Diana is shown climbing the wall and there are close up shots that show her strength. This portrayal challenges the societal construct that positions men as dominant and powerful, and women as weak and submissive. Moreover, the film aligns with real-world efforts towards gender equality, as the United Nations appointed the fictional character Wonder Woman as an Honorary Ambassador for the Empowerment of Women and Girls. This recognition underscores the film’s emphasis on portraying Wonder Woman as powerful, resilient, and independent, going beyond her physical beauty.

In addition to defying traditional ideals of women, Wonder Woman contributes to feminism through its choice of lead actress. Gal Gadot, hailing from Israel, becomes an icon for girls to look up to. Her journey from winning the Miss Israel beauty pageant to serving in the Israel Defense Forces as a combat instructor challenges stereotypes and demonstrates that women can occupy leadership roles. Gadot herself has expressed her belief that everyone should be feminist, emphasizing that feminism is about freedom of choice for all genders. Her casting in the film helps bridge cultural gaps and promotes inclusivity in the realm of superhero representation.

However, it is essential to acknowledge alternative perspectives that critique the film for objectifying women through the male gaze. Some argue that the film employs visual techniques that cater to the male audience and perpetuate the objectification of women. The portrayal of Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman, characterized by her slim figure, fair skin, and revealing costumes, is seen as intentionally flaunting her body. This can seen by having a Wonder Woman dresses in a corset and shorts, emphasizing her body and figure. While the film celebrates feminism in many aspects, it is important to recognize and critique instances where it may inadvertently reinforce traditional gendered expectations.

Despite these criticisms, Wonder Woman remains a significant milestone in promoting female empowerment and representation. Its success at the box office and positive reception among audiences highlight the demand for strong, complex female characters. By featuring a female superhero who possesses agency, strength, and compassion, the film provides a much-needed alternative to the male-dominated superhero genre. It offers a new model of heroism and inspires girls and women to embrace their own power and potential. Moreover, Wonder Woman films contribute to the broader feminist movement by sparking discussions and raising awareness about gender equality. It serves as a catalyst for conversations about representation, female empowerment, and the need for diverse voices in the entertainment industry. The film’s impact extends beyond the screen, inspiring individuals to challenge gender norms and fight for equal rights in their own lives and communities.

Wonder Woman explores the theme of the abuse of power through its portrayal of Ares, the god of war, and the larger context of World War I. Ares represents the embodiment of power and its corrupting influence. He is depicted as a manipulative and malevolent force, fueling the war and manipulating individuals to carry out his destructive agenda. This can be seen by Ares acting as someone who is on the side to help end the war, when in reality, he was the one creating the war. The movie illustrates how power, when misused, can lead to devastating consequences. Ares takes advantage of human vulnerabilities and weaknesses, exploiting their desires for power and control. His actions perpetuate the cycle of violence and suffering, showcasing the destructive nature of unchecked power. By exploring the abuse of power through the character of Ares and the larger context of war, Princess Diana highlights the need for individuals to be mindful of their own power and its potential consequences. It prompts viewers to reflect on the moral implications of power and encourages them to strive for a more just and balanced world.

Additionally, the film touches upon themes of discrimination and prejudice. Diana, as an outsider to the world of men, faces discrimination based on her gender and her origins. She encounters skepticism and disbelief from those who underestimate her abilities and dismiss her contributions. This serves as a commentary on the discrimination faced by marginalized groups and highlights the need to challenge and overcome prejudice. This can be seen throughout the whole movie especially, but a scene that stands out most to me is when Diana is willing to run out to the battlefield in order to stop Ares and save the village of people. Diana’s friends deny the request and instead insist on camping out behind the front line. Diana is furious with this and charges out onto the battlefield, also known as No Man’s Land, by herself. The film puts Wonder Woman in slow motion as she goes onto the field. Additionally, the film emphasizes the power by adding music that is powerful. By doing this, she showed Steve and the rest of the group what she was capable of, while also giving the men a chance to take the front line of Germany.

Wonder Woman , despite some criticisms, serves as a groundbreaking representation of female empowerment and challenges long-standing gender stereotypes. Through the strong and capable character of Diana Prince, the film inspires and empowers audiences, especially women and girls, to believe in their own strength and potential. By defying traditional ideals of women and featuring a lead actress from Israel, the film expands the notion of feminism and offers a diverse and inclusive perspective. While no work is without its flaws, Wonder Woma n contributes significantly to the ongoing dialogue surrounding gender equality and the representation of women in media and popular culture.

Driscoll, Molly. “Why Female Comic Book Fans Are Cheering for ‘Wonder Woman’.(The Culture).” The Christian Science Monitor, 1 June 2017, p. NA. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscpi&AN=edscpi.A493902825&site =eds-live&scope=site.

Ghaisani, Marinda P. D. “Wonder Woman (2017): An Ambiguous Symbol of Feminism.” Rubikon : Journal of Transnational American Studies , vol. 6, Nov. 2020, p. 12. EBSCOhost, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db= edsair&AN=edsair.doi.dedup…..ec9d92e44c874885010193dd319d304c&site=eds-live&s cope=site.

Marcus, Jaclyn. “Wonder Woman’s Costume as a Site for Feminist Debate.” Imaginations Journal , vol. 9, no. 2, July 2018, pp. 55–65. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.17742/IMAGE.FCM.9.2.6.

Potter, Amandas. “Feminist Heroines for Our Times: Screening the Amazon Warrior in Wonder Woman (1975 – 1979), Xena: Warrior Princess (1995 – 2001) and Wonder Woman (2017).” Thersites. Journal for Transcultural Presences & Diachronic Identities from Antiquity to Date , vol. 7, Nov. 2018. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.34679/thersites.vol7.85.

Difference, Power, and Discrimination in Film and Media: Student Essays Copyright © by Students at Linn-Benton Community College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Home / Essay Samples / Social Issues / Empowerment / Wonder Woman Superhero As A Symbol Of The Growing Female Empowerment

Wonder Woman Superhero As A Symbol Of The Growing Female Empowerment

- Category: Social Issues , Sociology

- Topic: Empowerment , Woman

Pages: 4 (1867 words)

Views: 1243

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Hate Speech Essays

Conversation Essays

Conflict Resolution Essays

Socialization Essays

Rhetorical Strategies Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->