- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

College writing, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

What Is College Writing?

College writing, also called academic writing, teaches critical thinking and writing skills useful both in class and in other areas of life. College courses demand many different kinds of writing using a variety of strategies for different audiences. Sometimes your instructor will assign a topic and define the audience; sometimes you will have to define the topic and audience yourself.

Types of Assignments

You will write many different types of assignments throughout your college career. Each type of assignment has specific requirements for content and format. The process of completing these assignments teaches you about the series of decisions you must make as you forge the link between your information and your audience. Click on the arrows below for some assignment types typically assigned in college.

written arguments

Short answers (such as discussion posts or essay questions on tests), lab reports, documentation of the research process, design documents (brochures, newsletters, powerpoints), business reports or plans, research essays, literature reviews, case studies, educating yourself through research.

Most college writing emphasizes the knowledge you gain in class and through research. This makes such writing different from your previous writing and perhaps more challenging. Instructors may expect your essays to contain more research and to show that you are capable of effectively evaluating those sources. You might be expected to incorporate sophisticated expository techniques, such as argument and persuasion, and to avoid flawed thinking, such as false assumptions and leaps in logic. You will often use the skills you learn in college writing throughout your life.

Key Takeaways

College writing

- teaches critical thinking skills.

- allows you to demonstrate your knowledge.

- takes many forms, depending on the discipline, the audience, the knowledge involved, and the goal of the assignment.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

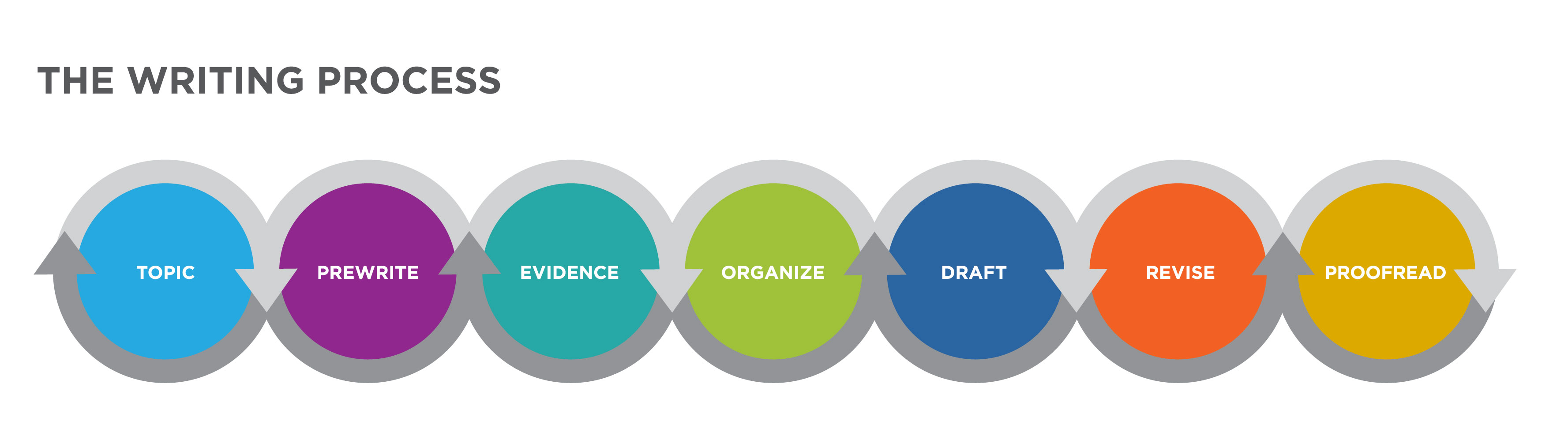

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Understanding Writing Assignments

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

How to Decipher the Paper Assignment

Many instructors write their assignment prompts differently. By following a few steps, you can better understand the requirements for the assignment. The best way, as always, is to ask the instructor about anything confusing.

- Read the prompt the entire way through once. This gives you an overall view of what is going on.

- Underline or circle the portions that you absolutely must know. This information may include due date, research (source) requirements, page length, and format (MLA, APA, CMS).

- Underline or circle important phrases. You should know your instructor at least a little by now - what phrases do they use in class? Does he repeatedly say a specific word? If these are in the prompt, you know the instructor wants you to use them in the assignment.

- Think about how you will address the prompt. The prompt contains clues on how to write the assignment. Your instructor will often describe the ideas they want discussed either in questions, in bullet points, or in the text of the prompt. Think about each of these sentences and number them so that you can write a paragraph or section of your essay on that portion if necessary.

- Rank ideas in descending order, from most important to least important. Instructors may include more questions or talking points than you can cover in your assignment, so rank them in the order you think is more important. One area of the prompt may be more interesting to you than another.

- Ask your instructor questions if you have any.

After you are finished with these steps, ask yourself the following:

- What is the purpose of this assignment? Is my purpose to provide information without forming an argument, to construct an argument based on research, or analyze a poem and discuss its imagery?

- Who is my audience? Is my instructor my only audience? Who else might read this? Will it be posted online? What are my readers' needs and expectations?

- What resources do I need to begin work? Do I need to conduct literature (hermeneutic or historical) research, or do I need to review important literature on the topic and then conduct empirical research, such as a survey or an observation? How many sources are required?

- Who - beyond my instructor - can I contact to help me if I have questions? Do you have a writing lab or student service center that offers tutorials in writing?

(Notes on prompts made in blue )

Poster or Song Analysis: Poster or Song? Poster!

Goals : To systematically consider the rhetorical choices made in either a poster or a song. She says that all the time.

Things to Consider: ah- talking points

- how the poster addresses its audience and is affected by context I'll do this first - 1.

- general layout, use of color, contours of light and shade, etc.

- use of contrast, alignment, repetition, and proximity C.A.R.P. They say that, too. I'll do this third - 3.

- the point of view the viewer is invited to take, poses of figures in the poster, etc. any text that may be present

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing I'll cover this second - 2.

- ethical implications

- how the poster affects us emotionally, or what mood it evokes

- the poster's implicit argument and its effectiveness said that was important in class, so I'll discuss this last - 4.

- how the song addresses its audience

- lyrics: how they rhyme, repeat, what they say

- use of music, tempo, different instruments

- possible cultural ramifications or social issues that have bearing

- emotional effects

- the implicit argument and its effectiveness

These thinking points are not a step-by-step guideline on how to write your paper; instead, they are various means through which you can approach the subject. I do expect to see at least a few of them addressed, and there are other aspects that may be pertinent to your choice that have not been included in these lists. You will want to find a central idea and base your argument around that. Additionally, you must include a copy of the poster or song that you are working with. Really important!

I will be your audience. This is a formal paper, and you should use academic conventions throughout.

Length: 4 pages Format: Typed, double-spaced, 10-12 point Times New Roman, 1 inch margins I need to remember the format stuff. I messed this up last time =(

Academic Argument Essay

5-7 pages, Times New Roman 12 pt. font, 1 inch margins.

Minimum of five cited sources: 3 must be from academic journals or books

- Design Plan due: Thurs. 10/19

- Rough Draft due: Monday 10/30

- Final Draft due: Thurs. 11/9

Remember this! I missed the deadline last time

The design plan is simply a statement of purpose, as described on pages 40-41 of the book, and an outline. The outline may be formal, as we discussed in class, or a printout of an Open Mind project. It must be a minimum of 1 page typed information, plus 1 page outline.

This project is an expansion of your opinion editorial. While you should avoid repeating any of your exact phrases from Project 2, you may reuse some of the same ideas. Your topic should be similar. You must use research to support your position, and you must also demonstrate a fairly thorough knowledge of any opposing position(s). 2 things to do - my position and the opposite.

Your essay should begin with an introduction that encapsulates your topic and indicates 1 the general trajectory of your argument. You need to have a discernable thesis that appears early in your paper. Your conclusion should restate the thesis in different words, 2 and then draw some additional meaningful analysis out of the developments of your argument. Think of this as a "so what" factor. What are some implications for the future, relating to your topic? What does all this (what you have argued) mean for society, or for the section of it to which your argument pertains? A good conclusion moves outside the topic in the paper and deals with a larger issue.

You should spend at least one paragraph acknowledging and describing the opposing position in a manner that is respectful and honestly representative of the opposition’s 3 views. The counterargument does not need to occur in a certain area, but generally begins or ends your argument. Asserting and attempting to prove each aspect of your argument’s structure should comprise the majority of your paper. Ask yourself what your argument assumes and what must be proven in order to validate your claims. Then go step-by-step, paragraph-by-paragraph, addressing each facet of your position. Most important part!

Finally, pay attention to readability . Just because this is a research paper does not mean that it has to be boring. Use examples and allow your opinion to show through word choice and tone. Proofread before you turn in the paper. Your audience is generally the academic community and specifically me, as a representative of that community. Ok, They want this to be easy to read, to contain examples I find, and they want it to be grammatically correct. I can visit the tutoring center if I get stuck, or I can email the OWL Email Tutors short questions if I have any more problems.

4 Understanding the Assignment

Understanding the assignment.

There are four kinds of analysis you need to do in order to fully understand an assignment: determining the purpose of the assignment , understanding how to answer an assignment’s questions , recognizing implied questions in the assignment , and recognizing the disciplinary expectations of the assignment .

Always make sure you fully understand an assignment before you start writing!

Determining the Purpose

The wording of an assignment should suggest its purpose. Any of the following might be expected of you in a college writing assignment:

- Summarizing information

- Analyzing ideas and concepts

- Taking a position and defending it

- Combining ideas from several sources and creating your own original argument.

Understanding How to Answer the Assignment

College writing assignments will ask you to answer a how or why question – questions that can’t be answered with just facts. For example, the question “ What are the names of the presidents of the US in the last twenty years?” needs only a list of facts to be answered. The question “ Who was the best president of the last twenty years and why?” requires you to take a position and support that position with evidence.

Sometimes, a list of prompts may appear with an assignment. Remember, your instructor will not expect you to answer all of the questions listed. They are simply offering you some ideas so that you can think of your own questions to ask.

Recognizing Implied Questions

A prompt may not include a clear ‘how’ or ‘why’ question, though one is always implied by the language of the prompt. For example:

“Discuss the effects of the No Child Left Behind Act on special education programs” is asking you to write how the act has affected special education programs.

“Consider the recent rise of autism diagnoses” is asking you to write why the diagnoses of autism are on the rise.

Recognizing Disciplinary Expectations

Depending on the discipline in which you are writing, different features and formats of your writing may be expected. Always look closely at key terms and vocabulary in the writing assignment, and be sure to note what type of evidence and citations style your instructor expects.

FYW: College Writing Basics Copyright © by . All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

College Writing

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you figure out what your college instructors expect when they give you a writing assignment. It will tell you how and why to move beyond the five-paragraph essays you learned to write in high school and start writing essays that are more analytical and more flexible.

What is a five-paragraph essay?

High school students are often taught to write essays using some variation of the five-paragraph model. A five-paragraph essay is hourglass-shaped: it begins with something general, narrows down in the middle to discuss specifics, and then branches out to more general comments at the end. In a classic five-paragraph essay, the first paragraph starts with a general statement and ends with a thesis statement containing three “points”; each body paragraph discusses one of those “points” in turn; and the final paragraph sums up what the student has written.

Why do high schools teach the five-paragraph model?

The five-paragraph model is a good way to learn how to write an academic essay. It’s a simplified version of academic writing that requires you to state an idea and support it with evidence. Setting a limit of five paragraphs narrows your options and forces you to master the basics of organization. Furthermore—and for many high school teachers, this is the crucial issue—many mandatory end-of-grade writing tests and college admissions exams like the SAT II writing test reward writers who follow the five-paragraph essay format.

Writing a five-paragraph essay is like riding a bicycle with training wheels; it’s a device that helps you learn. That doesn’t mean you should use it forever. Once you can write well without it, you can cast it off and never look back.

Why don’t five-paragraph essays work well for college writing?

The way college instructors teach is probably different from what you experienced in high school, and so is what they expect from you.

While high school courses tend to focus on the who, what, when, and where of the things you study—”just the facts”—college courses ask you to think about the how and the why. You can do very well in high school by studying hard and memorizing a lot of facts. Although college instructors still expect you to know the facts, they really care about how you analyze and interpret those facts and why you think those facts matter. Once you know what college instructors are looking for, you can see some of the reasons why five-paragraph essays don’t work so well for college writing:

- Five-paragraph essays often do a poor job of setting up a framework, or context, that helps the reader understand what the author is trying to say. Students learn in high school that their introduction should begin with something general. College instructors call these “dawn of time” introductions. For example, a student asked to discuss the causes of the Hundred Years War might begin, “Since the dawn of time, humankind has been plagued by war.” In a college course, the student would fare better with a more concrete sentence directly related to what he or she is going to say in the rest of the paper—for example, a sentence such as “In the early 14th century, a civil war broke out in Flanders that would soon threaten Western Europe’s balance of power.” If you are accustomed to writing vague opening lines and need them to get started, go ahead and write them, but delete them before you turn in the final draft. For more on this subject, see our handout on introductions .

- Five-paragraph essays often lack an argument. Because college courses focus on analyzing and interpreting rather than on memorizing, college instructors expect writers not only to know the facts but also to make an argument about the facts. The best five-paragraph essays may do this. However, the typical five-paragraph essay has a “listing” thesis, for example, “I will show how the Romans lost their empire in Britain and Gaul by examining military technology, religion, and politics,” rather than an argumentative one, for example, “The Romans lost their empire in Britain and Gaul because their opponents’ military technology caught up with their own at the same time as religious upheaval and political conflict were weakening the sense of common purpose on the home front.” For more on this subject, see our handout on argument .

- Five-paragraph essays are often repetitive. Writers who follow the five-paragraph model tend to repeat sentences or phrases from the introduction in topic sentences for paragraphs, rather than writing topic sentences that tie their three “points” together into a coherent argument. Repetitive writing doesn’t help to move an argument along, and it’s no fun to read.

- Five-paragraph essays often lack “flow.” Five-paragraph essays often don’t make smooth transitions from one thought to the next. The “listing” thesis statement encourages writers to treat each paragraph and its main idea as a separate entity, rather than to draw connections between paragraphs and ideas in order to develop an argument.

- Five-paragraph essays often have weak conclusions that merely summarize what’s gone before and don’t say anything new or interesting. In our handout on conclusions , we call these “that’s my story and I’m sticking to it” conclusions: they do nothing to engage readers and make them glad they read the essay. Most of us can remember an introduction and three body paragraphs without a repetitive summary at the end to help us out.

- Five-paragraph essays don’t have any counterpart in the real world. Read your favorite newspaper or magazine; look through the readings your professors assign you; listen to political speeches or sermons. Can you find anything that looks or sounds like a five-paragraph essay? One of the important skills that college can teach you, above and beyond the subject matter of any particular course, is how to communicate persuasively in any situation that comes your way. The five-paragraph essay is too rigid and simplified to fit most real-world situations.

- Perhaps most important of all: in a five-paragraph essay, form controls content, when it should be the other way around. Students begin with a plan for organization, and they force their ideas to fit it. Along the way, their perfectly good ideas get mangled or lost.

How do I break out of writing five-paragraph essays?

Let’s take an example based on our handout on thesis statements . Suppose you’re taking a course on contemporary communication, and the professor asks you to write a paper on this topic:

Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.

Thanks to your familiarity with the five paragraph essay structure and with the themes of your course, you are able to quickly write an introductory paragraph:

Social media allows the sharing of information through online networks among social connections. Everyone uses social media in our modern world for a variety of purposes: to learn about the news, keep up with friends, and even network for jobs. Social media cannot help but affect public awareness. In this essay, I will discuss the impact of social media on public awareness of political campaigns, public health initiatives, and current events.

Now you have something on paper. But you realize that this introduction sticks too close to the five-paragraph essay structure. The introduction starts too broadly by taking a step back and defining social media in general terms. Then it moves on to restate the prompt without quite addressing it: while it’s reasserted that there is an impact, the impact is not actually discussed. And the final sentence, instead of presenting an argument, only lists topics in sequence. You are prepared to write a paragraph on political campaigns, a paragraph on public health initiatives, and a paragraph on current events, but you aren’t sure what your point will be.

So you start again. Instead of trying to come up with something to say about each of three points, you brainstorm until you come up with a main argument, or thesis, about the impact of social media on public awareness. You think about how easy it is to share information on social media, as well as about how difficult it can be to discern more from less reliable information. As you brainstorm the effects of social media on public awareness in connection to political campaigns specifically, you realize you have enough to say about this topic without discussing two additional topics. You draft your thesis statement:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

Next you think about your argument’s parts and how they fit together. You read the Writing Center’s handout on organization . You decide that you’ll begin by addressing the counterargument that misinformation on social media has led to a less informed public. Addressing the counterargument point-by-point helps you articulate your evidence. You find it ends up taking more than one paragraph to discuss the strategies people use to compare and evaluate information as well as the evidence that people end up more informed as a result.

You notice that you now have four body paragraphs. You might have had three or two or seven; what’s important is that you allowed your argument to determine how many paragraphs would be needed and how they should fit together. Furthermore, your body paragraphs don’t each discuss separate topics, like “political campaigns” and “public health.” Instead they support different points in your argument. This is also a good moment to return to your introduction and revise it to focus more narrowly on introducing the argument presented in the body paragraphs in your paper.

Finally, after sketching your outline and writing your paper, you turn to writing a conclusion. From the Writing Center handout on conclusions , you learn that a “that’s my story and I’m sticking to it” conclusion doesn’t move your ideas forward. Applying the strategies you find in the handout, you may decide that you can use your conclusion to explain why the paper you’ve just written really matters.

Is it ever OK to write a five-paragraph essay?

Yes. Have you ever found yourself in a situation where somebody expects you to make sense of a large body of information on the spot and write a well-organized, persuasive essay—in fifty minutes or less? Sounds like an essay exam situation, right? When time is short and the pressure is on, falling back on the good old five-paragraph essay can save you time and give you confidence. A five-paragraph essay might also work as the framework for a short speech. Try not to fall into the trap, however, of creating a “listing” thesis statement when your instructor expects an argument; when planning your body paragraphs, think about three components of an argument, rather than three “points” to discuss. On the other hand, most professors recognize the constraints of writing blue-book essays, and a “listing” thesis is probably better than no thesis at all.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Blue, Tina. 2001. “AP English Blather.” Essay, I Say (blog), January 26, 2001. http://essayisay.homestead.com/blather.html .

Blue, Tina. 2001. “A Partial Defense of the Five-Paragraph Theme as a Model for Student Writing.” Essay, I Say (blog), January 13, 2001. http://essayisay.homestead.com/fiveparagraphs.html .

Denecker, Christine. 2013. “Transitioning Writers across the Composition Threshold: What We Can Learn from Dual Enrollment Partnerships.” Composition Studies 41 (1): 27-50.

Fanetti, Susan et al. 2010. “Closing the Gap between High School Writing Instruction and College Writing Expectations.” The English Journal 99 (4): 77-83.

Hillocks, George. 2002. The Testing Trap: How State Assessments Control Learning . New York and London: Teachers College Press.

Hjortshoj, Keith. 2009. The Transition to College Writing , 2nd ed. New York: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Shen, Andrea. 2000. “Study Looks at Role of Writing in Learning.” Harvard Gazette (blog). October 26, 2000. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2000/10/study-looks-at-role-of-writing-in-learning/ .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Search form

How to write the best college assignments.

By Lois Weldon

When it comes to writing assignments, it is difficult to find a conceptualized guide with clear and simple tips that are easy to follow. That’s exactly what this guide will provide: few simple tips on how to write great assignments, right when you need them. Some of these points will probably be familiar to you, but there is no harm in being reminded of the most important things before you start writing the assignments, which are usually determining on your credits.

The most important aspects: Outline and Introduction

Preparation is the key to success, especially when it comes to academic assignments. It is recommended to always write an outline before you start writing the actual assignment. The outline should include the main points of discussion, which will keep you focused throughout the work and will make your key points clearly defined. Outlining the assignment will save you a lot of time because it will organize your thoughts and make your literature searches much easier. The outline will also help you to create different sections and divide up the word count between them, which will make the assignment more organized.

The introduction is the next important part you should focus on. This is the part that defines the quality of your assignment in the eyes of the reader. The introduction must include a brief background on the main points of discussion, the purpose of developing such work and clear indications on how the assignment is being organized. Keep this part brief, within one or two paragraphs.

This is an example of including the above mentioned points into the introduction of an assignment that elaborates the topic of obesity reaching proportions:

Background : The twenty first century is characterized by many public health challenges, among which obesity takes a major part. The increasing prevalence of obesity is creating an alarming situation in both developed and developing regions of the world.

Structure and aim : This assignment will elaborate and discuss the specific pattern of obesity epidemic development, as well as its epidemiology. Debt, trade and globalization will also be analyzed as factors that led to escalation of the problem. Moreover, the assignment will discuss the governmental interventions that make efforts to address this issue.

Practical tips on assignment writing

Here are some practical tips that will keep your work focused and effective:

– Critical thinking – Academic writing has to be characterized by critical thinking, not only to provide the work with the needed level, but also because it takes part in the final mark.

– Continuity of ideas – When you get to the middle of assignment, things can get confusing. You have to make sure that the ideas are flowing continuously within and between paragraphs, so the reader will be enabled to follow the argument easily. Dividing the work in different paragraphs is very important for this purpose.

– Usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ – According to the academic writing standards, the assignments should be written in an impersonal language, which means that the usage of ‘you’ and ‘I’ should be avoided. The only acceptable way of building your arguments is by using opinions and evidence from authoritative sources.

– Referencing – this part of the assignment is extremely important and it takes a big part in the final mark. Make sure to use either Vancouver or Harvard referencing systems, and use the same system in the bibliography and while citing work of other sources within the text.

– Usage of examples – A clear understanding on your assignment’s topic should be provided by comparing different sources and identifying their strengths and weaknesses in an objective manner. This is the part where you should show how the knowledge can be applied into practice.

– Numbering and bullets – Instead of using numbering and bullets, the academic writing style prefers the usage of paragraphs.

– Including figures and tables – The figures and tables are an effective way of conveying information to the reader in a clear manner, without disturbing the word count. Each figure and table should have clear headings and you should make sure to mention their sources in the bibliography.

– Word count – the word count of your assignment mustn’t be far above or far below the required word count. The outline will provide you with help in this aspect, so make sure to plan the work in order to keep it within the boundaries.

The importance of an effective conclusion

The conclusion of your assignment is your ultimate chance to provide powerful arguments that will impress the reader. The conclusion in academic writing is usually expressed through three main parts:

– Stating the context and aim of the assignment

– Summarizing the main points briefly

– Providing final comments with consideration of the future (discussing clear examples of things that can be done in order to improve the situation concerning your topic of discussion).

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:11.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;}

Lois Weldon is writer at Uk.bestdissertation.com . Lives happily at London with her husband and lovely daughter. Adores writing tips for students. Passionate about Star Wars and yoga.

7 comments on “How To Write The Best College Assignments”

Extremely useful tip for students wanting to score well on their assignments. I concur with the writer that writing an outline before ACTUALLY starting to write assignments is extremely important. I have observed students who start off quite well but they tend to lose focus in between which causes them to lose marks. So an outline helps them to maintain the theme focused.

Hello Great information…. write assignments

Well elabrated

Thanks for the information. This site has amazing articles. Looking forward to continuing on this site.

This article is certainly going to help student . Well written.

Really good, thanks

Practical tips on assignment writing, the’re fantastic. Thank you!

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1-College Writing

Common Types of Writing Assignments

While much of the writing you did in high school may have been for an English or literature class, in college, writing is a common form of expression and scholarship in many fields and thus in many courses.

You may have to write essays, reflections, discussion board posts, or research papers in your history, biology, psychology, art history, or computer science classes.

Writing assignments in college vary in length, purpose, and the relationship between the writer (you) and the topic. Sometimes you may be asked to gather information and write a report on your findings . Sometimes you may be asked to compare opinions expressed by experts. You might be asked to answer a question or state your position and defend it with evidence . Some assignments require a mixture of several of these tasks.

When a writing assignment is mentioned in the syllabus of a course, make sure you understand the assignment long before you begin to do it. The university’s Writing Center recommends that you note the vocabulary used in assignment descriptions and make sure you understand what actions certain words suggest or require. You should also talk to peers in your class to compare understandings and expectations.

The university’s Writing Center consultants will help you with questions about an assignment and how to ask your instructor for more information if necessary. They will help you strengthen your writing, give you feedback on your ideas, and offer suggestions for organizing your content. They can tell you if you are appropriately using sources.

The Writing Center is not only for students who have questions or are puzzled about assignments. It offers support to experienced writers, too. Faculty and graduate students routinely schedule sessions with Writing Center consultants.

Strong, experienced writers enjoy conversation about their writing decisions and find it helpful to have an outside reader for their work.

Conferences with a writing consultant can be face-to-face or online.

If you are uneasy about talking with your instructor, make an appointment at the Writing Center: https://cstw.osu.edu/writing-center

Common characteristics of writing in college:

- Based on evidence

- Is written for a very or moderately knowledgeable audience rather than general public

- Style is formal, objective, often technical

- Uses conventional formatting

- Documents evidence using a professional citation style

(From: Lunsford & Ruszkiewicz, p. 367)

An Introduction to Choosing & Using Sources Copyright © 2015 by Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.1 What’s Different about College Writing?

Learning objectives.

- Define “academic writing.”

- Identify key differences between writing in college and writing in high school or on the job.

- Identify different types of papers that are commonly assigned.

- Describe what instructors expect from student writing.

Academic writing refers to writing produced in a college environment. Often this is writing that responds to other writing—to the ideas or controversies that you’ll read about. While this definition sounds simple, academic writing may be very different from other types of writing you have done in the past. Often college students begin to understand what academic writing really means only after they receive negative feedback on their work. To become a strong writer in college, you need to achieve a clear sense of two things:

- The academic environment

- The kinds of writing you’ll be doing in that environment

Differences between High School and College Writing

Students who struggle with writing in college often conclude that their high school teachers were too easy or that their college instructors are too hard. In most cases, neither explanation is fully accurate or fair. A student having difficulty with college writing usually just hasn’t yet made the transition from high school writing to college writing. That shouldn’t be surprising, for many beginning college students do not even know that there is a transition to be made.

In high school, most students think of writing as the subject of English classes. Few teachers in other courses give much feedback on student writing; many do not even assign writing. This says more about high school than about the quality of teachers or about writing itself. High school teachers typically teach five courses a day and often more than 150 students. Those students often have a very wide range of backgrounds and skill levels.

Thus many high school English instructors focus on specific, limited goals. For example, they may teach the “five paragraph essay” as the right way to organize a paper because they want to give every student some idea of an essay’s basic structure. They may give assignments on stories and poems because their own college background involved literature and literary analysis. In classes other than English, many high school teachers must focus on an established body of information and may judge students using tests that measure only how much of this information they acquire. Often writing itself is not directly addressed in such classes.

This does not mean that students don’t learn a great deal in high school, but it’s easy to see why some students think that writing is important only in English classes. Many students also believe an academic essay must be five paragraphs long or that “school writing” is usually literary analysis.

Think about how college differs from high school. In many colleges, the instructors teach fewer classes and have fewer students. In addition, while college students have highly diverse backgrounds, the skills of college students are less variable than in an average high school class. In addition, college instructors are specialists in the fields they teach, as you recall from Chapter 7 “Interacting with Instructors and Classes” . College instructors may design their courses in unique ways, and they may teach about specialized subjects. For all of these reasons, college instructors are much more likely than high school teachers to

- assign writing,

- respond in detail to student writing,

- ask questions that cannot be dealt with easily in a fixed form like a five-paragraph essay.

Your transition to college writing could be even more dramatic. The kind of writing you have done in the past may not translate at all into the kind of writing required in college. For example, you may at first struggle with having to write about very different kinds of topics, using different approaches. You may have learned only one kind of writing genre (a kind of approach or organization) and now find you need to master other types of writing as well.

What Kinds of Papers Are Commonly Assigned in College Classes?

Think about the topic “gender roles”—referring to expectations about differences in how men and women act. You might study gender roles in an anthropology class, a film class, or a psychology class. The topic itself may overlap from one class to another, but you would not write about this subject in the same way in these different classes. For example, in an anthropology class, you might be asked to describe how men and women of a particular culture divide important duties. In a film class, you may be asked to analyze how a scene portrays gender roles enacted by the film’s characters. In a psychology course, you might be asked to summarize the results of an experiment involving gender roles or compare and contrast the findings of two related research projects.

It would be simplistic to say that there are three, or four, or ten, or any number of types of academic writing that have unique characteristics, shapes, and styles. Every assignment in every course is unique in some ways, so don’t think of writing as a fixed form you need to learn. On the other hand, there are certain writing approaches that do involve different kinds of writing. An approach is the way you go about meeting the writing goals for the assignment. The approach is usually signaled by the words instructors use in their assignments.

When you first get a writing assignment, pay attention first to keywords for how to approach the writing. These will also suggest how you may structure and develop your paper. Look for terms like these in the assignment:

- Summarize. To restate in your own words the main point or points of another’s work.

- Define. To describe, explore, or characterize a keyword, idea, or phenomenon.

- Classify. To group individual items by their shared characteristics, separate from other groups of items.

- Compare/contrast. To explore significant likenesses and differences between two or more subjects.

- Analyze. To break something, a phenomenon, or an idea into its parts and explain how those parts fit or work together.

- Argue. To state a claim and support it with reasons and evidence.

- Synthesize. To pull together varied pieces or ideas from two or more sources.

Note how this list is similar to the words used in examination questions that involve writing. (See Table 6.1 “Words to Watch for in Essay Questions” in Chapter 6 “Preparing for and Taking Tests” , Section 6.4 “The Secrets of the Q and A’s” .) This overlap is not a coincidence—essay exams are an abbreviated form of academic writing such as a class paper.

Sometimes the keywords listed don’t actually appear in the written assignment, but they are usually implied by the questions given in the assignment. “What,” “why,” and “how” are common question words that require a certain kind of response. Look back at the keywords listed and think about which approaches relate to “what,” “why,” and “how” questions.

- “What” questions usually prompt the writing of summaries, definitions, classifications, and sometimes compare-and-contrast essays. For example, “ What does Jones see as the main elements of Huey Long’s populist appeal?” or “ What happened when you heated the chemical solution?”

- “Why” and “how” questions typically prompt analysis, argument, and synthesis essays. For example, “ Why did Huey Long’s brand of populism gain force so quickly?” or “ Why did the solution respond the way it did to heat?”

Successful academic writing starts with recognizing what the instructor is requesting, or what you are required to do. So pay close attention to the assignment. Sometimes the essential information about an assignment is conveyed through class discussions, however, so be sure to listen for the keywords that will help you understand what the instructor expects. If you feel the assignment does not give you a sense of direction, seek clarification. Ask questions that will lead to helpful answers. For example, here’s a short and very vague assignment:

Discuss the perspectives on religion of Rousseau, Bentham, and Marx. Papers should be four to five pages in length.

Faced with an assignment like this, you could ask about the scope (or focus) of the assignment:

- Which of the assigned readings should I concentrate on?

- Should I read other works by these authors that haven’t been assigned in class?

- Should I do research to see what scholars think about the way these philosophers view religion?

- Do you want me to pay equal attention to each of the three philosophers?

You can also ask about the approach the instructor would like you to take. You can use the keywords the instructor may not have used in the assignment:

- Should I just summarize the positions of these three thinkers, or should I compare and contrast their views?

- Do you want me to argue a specific point about the way these philosophers approach religion?

- Would it be OK if I classified the ways these philosophers think about religion?

Never just complain about a vague assignment. It is fine to ask questions like these. Such questions will likely engage your instructor in a productive discussion with you.

Key Takeaways

- Writing is crucial to college success because it is the single most important means of evaluation.

- Writing in college is not limited to the kinds of assignments commonly required in high school English classes.

- Writers in college must pay close attention to the terms of an assignment.

- If an assignment is not clear, seek clarification from the instructor.

Checkpoint Exercises

What kind(s) of writing have you practiced most in your recent past?

____________________________________________________________________

Name two things that make academic writing in college different from writing in high school.

Explain how the word “what” asks for a different kind of paper than the word “why.”

College Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: In College, Everything’s an Argument- A Guide for Decoding College Writing Assignments

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 57093

Let’s restate this complex “literacy task” you’ll be asked repeatedly to do in your writing assignments. Typically, you’ll be required to write an “essay” based upon your analysis of some reading(s). In this essay you’ll need to present an argument where you make a claim (i.e. present a “thesis”) and support that claim with good reasons that have adequate and appropriate evidence to back them up. The dynamic of this argumentative task often confuses first year writers, so let’s examine it more closely.

Academic Writing Is an Argument

To start, let’s focus on argument. What does it mean to present an “argument” in college writing? Rather than a shouting match between two disagreeing sides, argument instead means a carefully arranged and supported presentation of a viewpoint. Its purpose is not so much to win the argument as to earn your audience’s consideration (and even approval) of your perspective. It resembles a conversation between two people who may not hold the same opinions, but they both desire a better understanding of the subject matter under discussion. My favorite analogy, however, to describe the nature of this argumentative stance in college writing is the courtroom. In this scenario, you are like a lawyer making a case at trial that the defendant is not guilty, and your readers are like the jury who will decide if the defendant is guilty or not guilty. This jury (your readers) won’t just take your word that he’s innocent; instead, you must convince them by presenting evidence that proves he is not guilty. Stating your opinion is not enough—you have to back it up too. I like this courtroom analogy for capturing two importance things about academic argument: 1) the value of an organized presentation of your “case,” and 2) the crucial element of strong evidence.

Academic Writing Is an Analysis

We now turn our attention to the actual writing assignment and that confusing word “analyze.” Your first job when you get a writing assignment is to figure out what the professor expects. This assignment may be explicit in its expectations, but often built into the wording of the most defined writing assignments are implicit expectations that you might not recognize. First, we can say that unless your professor specifically asks you to summarize, you won’t write a summary. Let me say that again: don’t write a summary unless directly asked to. But what, then, does the professor want? We have already picked out a few of these expectations: You can count on the instructor expecting you to read closely, research adequately, and write an argument where you will demonstrate your ability to apply and use important concepts you have been studying. But the writing task also implies that your essay will be the result of an analysis. At times, the writing assignment may even explicitly say to write an analysis, but often this element of the task remains unstated.

So what does it mean to analyze? One way to think of an analysis is that it asks you to seek How and Why questions much more than What questions. An analysis involves doing three things:

1. Engage in an open inquiry where the answer is not known at first (and where you leave yourself open to multiple suggestions)

2. Identify meaningful parts of the subject

3. Examine these separate parts and determine how they relate to each other

An analysis breaks a subject apart to study it closely, and from this inspection, ideas for writing emerge. When writing assignments call on you to analyze, they require you to identify the parts of the subject (parts of an ad, parts of a short story, parts of Hamlet’s character), and then show how these parts fit or don’t fit together to create some larger effect or meaning. Your interpretation of how these parts fit together constitutes your claim or thesis, and the task of your essay is then to present an argument defending your interpretation as a valid or plausible one to make. My biggest bit of advice about analysis is not to do it all in your head. Analysis works best when you put all the cards on the table, so to speak. Identify and isolate the parts of your analysis, and record important features and characteristics of each one. As patterns emerge, you sort and connect these parts in meaningful ways. For me, I have always had to do this recording and thinking on scratch pieces of paper. Just as critical reading forms a crucial element of the literacy task of a college writing assignment, so too does this analysis process. It’s built in.

Three Common Types of College Writing Assignments

We have been decoding the expectations of the academic writing task so far, and I want to turn now to examine the types of assignments you might receive. From my experience, you are likely to get three kinds of writing assignments based upon the instructor’s degree of direction for the assignment. We’ll take a brief look at each kind of academic writing task.

The Closed Writing Assignment

• Is Creon a character to admire or condemn?

• Does your advertisement employ techniques of propaganda, and if so what kind?

• Was the South justified in seceding from the Union?

• In your opinion, do you believe Hamlet was truly mad?

These kinds of writing assignments present you with two counter claims and ask you to determine from your own analysis the more valid claim. They resemble yes-no questions. These topics define the claim for you, so the major task of the writing assignment then is working out the support for the claim. They resemble a math problem in which the teacher has given you the answer and now wants you to “show your work” in arriving at that answer.

Be careful with these writing assignments, however, because often these topics don’t have a simple yes/no, either/or answer (despite the nature of the essay question). A close analysis of the subject matter often reveals nuances and ambiguities within the question that your eventual claim should reflect. Perhaps a claim such as, “In my opinion, Hamlet was mad” might work, but I urge you to avoid such a simplistic thesis. This thesis would be better: “I believe Hamlet’s unhinged mind borders on insanity but doesn’t quite reach it.”

The Semi-Open Writing Assignment

• Discuss the role of law in Antigone.

• Explain the relationship between character and fate in Hamlet.

• Compare and contrast the use of setting in two short stories.

• Show how the Fugitive Slave Act influenced the Abolitionist Movement.

Although these topics chart out a subject matter for you to write upon, they don’t offer up claims you can easily use in your paper. It would be a misstep to offer up claims such as, “Law plays a role in Antigone” or “In Hamlet we can see a relationship between character and fate.” Such statements express the obvious and what the topic takes for granted. The question, for example, is not whether law plays a role in Antigone, but rather what sort of role law plays. What is the nature of this role? What influences does it have on the characters or actions or theme? This kind of writing assignment resembles a kind of archeological dig. The teacher cordons off an area, hands you a shovel, and says dig here and see what you find.

Be sure to avoid summary and mere explanation in this kind of assignment. Despite using key words in the assignment such as “explain,” “illustrate,” analyze,” “discuss,” or “show how,” these topics still ask you to make an argument. Implicit in the topic is the expectation that you will analyze the reading and arrive at some insights into patterns and relationships about the subject. Your eventual paper, then, needs to present what you found from this analysis—the treasure you found from your digging. Determining your own claim represents the biggest challenge for this type of writing assignment.

The Open Writing Assignment

• Analyze the role of a character in Dante’s The Inferno.

• What does it mean to be an “American” in the 21st Century?

• Analyze the influence of slavery upon one cause of the Civil War.

• Compare and contrast two themes within Pride and Prejudice.

These kinds of writing assignments require you to decide both your writing topic and you claim (or thesis). Which character in the Inferno will I pick to analyze? What two themes in Pride and Prejudice will I choose to write about? Many students struggle with these types of assignments because they have to understand their subject matter well before they can intelligently choose a topic. For instance, you need a good familiarity with the characters in The Inferno before you can pick one. You have to have a solid understanding defining elements of American identity as well as 21st century culture before you can begin to connect them. This kind of writing assignment resembles riding a bike without the training wheels on. It says, “You decide what to write about.” The biggest decision, then, becomes selecting your topic and limiting it to a manageable size.

Picking and Limiting a Writing Topic

Let’s talk about both of these challenges: picking a topic and limiting it. Remember how I said these kinds of essay topics expect you to choose what to write about from a solid understanding of your subject? As you read and review your subject matter, look for things that interest you. Look for gaps, puzzling items, things that confuse you, or connections you see. Something in this pile of rocks should stand out as a jewel: as being “do-able” and interesting. (You’ll write best when you write from both your head and your heart.) Whatever topic you choose, state it as a clear and interesting question. You may or may not state this essay question explicitly in the introduction of your paper (I actually recommend that you do), but it will provide direction for your paper and a focus for your claim since that claim will be your answer to this essay question. For example, if with the Dante topic you decided to write on Virgil, your essay question might be: “What is the role of Virgil toward the character of Dante in The Inferno?” The thesis statement, then, might be this: “Virgil’s predominant role as Dante’s guide through hell is as the voice of reason.” Crafting a solid essay question is well worth your time because it charts the territory of your essay and helps you declare a focused thesis statement.

Many students struggle with defining the right size for their writing project. They chart out an essay question that it would take a book to deal with adequately. You’ll know you have that kind of topic if you have already written over the required page length but only touched one quarter of the topics you planned to discuss. In this case, carve out one of those topics and make your whole paper about it. For instance, with our Dante example, perhaps you planned to discuss four places where Virgil’s role as the voice of reason is evident. Instead of discussing all four, focus your essay on just one place. So your revised thesis statement might be: “Close inspection of Cantos I and II reveal that Virgil serves predominantly as the voice of reason for Dante on his journey through hell.” A writing teacher I had in college said it this way: A well tended garden is better than a large one full of weeds. That means to limit your topic to a size you can handle and support well.

Three Characteristics of Academic Writing

I want to wrap up this section by sharing in broad terms what the expectations are behind an academic writing assignment. Chris Thaiss and Terry Zawacki conducted research at George Mason University where they asked professors from their university what they thought academic writing was and its standards. They came up with three characteristics:

1. Clear evidence in writing that the writer(s) have been persistent, open-minded, and disciplined in study. (5)

2. The dominance of reason over emotions or sensual perception. (5)

3. An imagined reader who is coolly rational, reading for information, and intending to formulate a reasoned response. (7)

Your professor wants to see these three things in your writing when they give you a writing assignment. They want to see in your writing the results of your efforts at the various literacy tasks we have been discussing: critical reading, research, and analysis. Beyond merely stating opinions, they also want to see an argument toward an intelligent audience where you provide good reasons to support your interpretations.

Module 4: Writing in College

Writing assignments, learning objectives.

- Describe common types and expectations of writing tasks given in a college class

Figure 1 . All college classes require some form of writing. Investing some time in refining your writing skills so that you are a more confident, skilled, and efficient writer will pay dividends in the long run.

What to Do With Writing Assignments

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Others are more open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward completing the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—they will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

Writing in college is usually a response to class materials—an assigned reading, a discussion in class, an experiment in a lab. Generally speaking, these writing tasks can be divided into three broad categories: summary assignments, defined-topic assignments, and undefined-topic assignments.

Link to Learning

Empire State College offers an Assignment Calculator to help you plan ahead for your writing assignment. Just plug in the date you plan to get started and the date it is due, and the calculator will help break it down into manageable chunks.

Summary Assignments

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

- reflects your accurate understanding of a source’s thesis or purpose

- differentiates between major and minor ideas in a source

- demonstrates your ability to identify key phrases to quote

- shows your ability to effectively paraphrase most of the source’s ideas

- captures the tone, style, and distinguishing features of a source

- does not reflect your personal opinion about the source

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary. A summary is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

Writing Effective Summaries

Start with a clear identification of the work.

This automatically lets your readers know your intentions and that you’re covering the work of another author.

- In the featured article “Five Kinds of Learning,” the author, Holland Oates, justifies his opinion on the hot topic of learning styles — and adds a few himself.

Summarize the Piece as a Whole

Omit nothing important and strive for overall coherence through appropriate transitions. Write using “summarizing language.” Your reader needs to be reminded that this is not your own work. Use phrases like the article claims, the author suggests, etc.

- Present the material in a neutral fashion. Your opinions, ideas, and interpretations should be left in your brain — don’t put them into your summary. Be conscious of choosing your words. Only include what was in the original work.

- Be concise. This is a summary — it should be much shorter than the original piece. If you’re working on an article, give yourself a target length of 1/4 the original article.

Conclude with a Final Statement

This is not a statement of your own point of view, however; it should reflect the significance of the book or article from the author’s standpoint.

- Without rewriting the article, summarize what the author wanted to get across. Be careful not to evaluate in the conclusion or insert any of your own assumptions or opinions.

Understanding the Assignment and Getting Started

Figure 2 . Many writing assignments will have a specific prompt that sends you first to your textbook, and then to outside resources to gather information.

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt —will explain the purpose of the assignment and the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.).

Also, don’t forget to check the rubric, if there is one, to understand how your writing will be assessed. After analyzing the prompt and the rubric, you should have a better sense of what kind of writing you are expected to produce.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment! In a situation like that, consider the following tips:

- Focus on the verbs . Look for verbs like compare, explain, justify, reflect , or the all-purpose analyze . You’re not just producing a paper as an artifact; you’re conveying, in written communication, some intellectual work you have done. So the question is, what kind of thinking are you supposed to do to deepen your learning?

- Put the assignment in context . Many professors think in terms of assignment sequences. For example, a social science professor may ask you to write about a controversial issue three times: first, arguing for one side of the debate; second, arguing for another; and finally, from a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective, incorporating text produced in the first two assignments. A sequence like that is designed to help you think through a complex issue. If the assignment isn’t part of a sequence, think about where it falls in the span of the course (early, midterm, or toward the end), and how it relates to readings and other assignments. For example, if you see that a paper comes at the end of a three-week unit on the role of the Internet in organizational behavior, then your professor likely wants you to synthesize that material.

- Try a free-write . A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free”; it actually sounds kind of coerced, right? The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writer’s block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is…,” and—booyah!—you’re off and running.

- Ask for clarification . Even the most carefully crafted assignments may need some verbal clarification, especially if you’re new to a course or field. Professors generally love questions, so don’t be afraid to ask. Try to convey to your instructor that you want to learn and you’re ready to work, and not just looking for advice on how to get an A.

Defined-Topic Assignments

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter. (Discuss the use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God , for example.)

Remember, even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus your discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Undefined-Topic Assignments

Another writing assignment you’ll potentially encounter is one in which the topic may be only broadly identified (“water conservation” in an ecology course, for instance, or “the Dust Bowl” in a U.S. History course), or even completely open (“compose an argumentative research essay on a subject of your choice”).

Figure 3 . For open-ended assignments, it’s best to pick something that interests you personally.

Where defined-topic essays demonstrate your knowledge of the content , undefined-topic assignments are used to demonstrate your skills— your ability to perform academic research, to synthesize ideas, and to apply the various stages of the writing process.

The first hurdle with this type of task is to find a focus that interests you. Don’t just pick something you feel will be “easy to write about” or that you think you already know a lot about —those almost always turn out to be false assumptions. Instead, you’ll get the most value out of, and find it easier to work on, a topic that intrigues you personally or a topic about which you have a genuine curiosity.

The same getting-started ideas described for defined-topic assignments will help with these kinds of projects, too. You can also try talking with your instructor or a writing tutor (at your college’s writing center) to help brainstorm ideas and make sure you’re on track.

Getting Started in the Writing Process

Writing is not a linear process, so writing your essay, researching, rewriting, and adjusting are all part of the process. Below are some tips to keep in mind as you approach and manage your assignment.

Figure 4 . Writing is a recursive process that begins with examining the topic and prewriting.

Write down topic ideas. If you have been assigned a particular topic or focus, it still might be possible to narrow it down or personalize it to your own interests.

If you have been given an open-ended essay assignment, the topic should be something that allows you to enjoy working with the writing process. Select a topic that you’ll want to think about, read about, and write about for several weeks, without getting bored.

Figure 5 . Just getting started is sometimes the most difficult part of writing. Freewriting and planning to write multiple drafts can help you dive in.

If you’re writing about a subject you’re not an expert on and want to make sure you are presenting the topic or information realistically, look up the information or seek out an expert to ask questions.

- Note: Be cautious about information you retrieve online, especially if you are writing a research paper or an article that relies on factual information. A quick Google search may turn up unreliable, misleading sources. Be sure you consider the credibility of the sources you consult (we’ll talk more about that later in the course). And keep in mind that published books and works found in scholarly journals have to undergo a thorough vetting process before they reach publication and are therefore safer to use as sources.

- Check out a library. Yes, believe it or not, there is still information to be found in a library that hasn’t made its way to the Web. For an even greater breadth of resources, try a college or university library. Even better, research librarians can often be consulted in person, by phone, or even by email. And they love helping students. Don’t be afraid to reach out with questions!

Write a Rough Draft

It doesn’t matter how many spelling errors or weak adjectives you have in it. Your draft can be very rough! Jot down those random uncategorized thoughts. Write down anything you think of that you want included in your writing and worry about organizing and polishing everything later.

If You’re Having Trouble, Try F reewriting

Set a timer and write continuously until that time is up. Don’t worry about what you write, just keeping moving your pencil on the page or typing something (anything!) into the computer.

- Outcome: Writing in College. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike