Being Latina and the struggle of the dualities of two worlds

Reflections on why our identities can help create a better world for all of us.

A few days ago, I attended a Zoom presentation organized by ASUN entitled “What does it mean to be Latinx?” Every time I witness the complexity of identities in the Latinx community in the United States, I am amazed. Amazed that we are always perceived as a homogenous group, when in reality, we couldn’t come from more different backgrounds, and we couldn’t have more different and complex identities. Also, the challenges we face are as different as each of our stories. So, in the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, please indulge me in letting me tell you my story.

There is a well-known character in Mexican history that invokes both love and condemnation from most Mexicans. Her name was Malintzin but history knows her as La Malinche . Her story is similar to that of U.S.A.’s Pocahontas ; the beautiful indigenous woman who abandons her tribe to help the white man. (The legends omit how she became the property of such White men, but that’s another story).

La Malinche was a Nahúatl woman who was given to Hernán Cortés as a slave. Due to her upperclass education, she spoke two languages, an ability that made her very useful to Hernán Cortés in communicating with the indigenous people as he went about conquering Mexico. On one hand, she was intelligent and, clearly, resilient. But on the other hand, she helped Cortés begin the Spanish colonization of the Nuevo Mundo. This duality is what gives her such a complex identity. And this duality is one that follows me.

When I was in high school, several of my classmates would sometimes call me Malinchista . As you can imagine, that was NOT a compliment. By definition, a Malinchista is “a person who denies her own cultural heritage by preferring foreign cultural expressions” (I’m not making it up; look it up).

In my early teens, I discovered American football. While switching channels on the television, I stumbled across a game being played in several feet of snow. I had never seen this! The game was being played in Minnesota. That year, the Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl, and I became a die-hard fan of Roger Staubach and “America’s Team.” This marked the initiation of my love for all things American. I learned about Formula 1, Sports Illustrated and Tiger Beat. Yes, Tiger Beat introduced me to the American darlings of my generation. My bedroom walls were covered with pictures of American teen idols I had never seen before in my life (in the 1970s, Mexican TV programming didn’t broadcast many American TV shows; I only remember Dallas and The Partridge Family , which of course, I loved).

I also loved English-language songs. I used to spend my money buying cancioneros , books similar in format and quality to comic books, for people who were learning to play the guitar. The cancioneros had the lyrics of the songs along with the music notes. I literally used these cancioneros to practice my English. I would translate each word of the songs, and then I would play the records over and over until I memorized the lyrics and could actually follow the singer pronouncing the words. Do you know how hard it is to sing at full speed: “Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall?”

By the time I was in college, I had already spent time in the city of Dallas (and yes, I made the pilgrimage to Irving, Texas and the Cowboys’ stadium) – and perfected my English. I started studying English when I entered first grade. By middle school, my parents were paying a private tutor. In Mexico, English was accepted as the lingua franca needed to succeed in the world, and my parents were going to make sure I learned it. (My dad had taught himself English, and he shared my enthusiasm for English language magazines, although not for the Dallas Cowboys.) Learning a second language allowed me to learn about, navigate and integrate into a different culture. And, unlike La Malinche , I did this of my own volition.

When I made the decision to come to the United States to study, my father told me, “If you ever decide this is not for you or things don’t work out, come back home.” But I was not turning back. In my mind, America was the best place in the whole world (my small world, at least). I had spent a semester in an exchange program at the University of Oklahoma, and I knew back then I belonged in the United States. One of the things that caught my attention early on was the fact that people could wear their pajamas to class (I know you’ve seen it), and nobody blinked an eye. One could wear her hair in blue spikes or wear slippers to the grocery store, and no one would say a thing. To me, that was amazing! People didn’t bother you, judge you or care what you wore. I felt America was the place where not only public services worked, but where you could be yourself and you could be free to be whomever you wanted to be. There was a sense of freedom that was refreshing.

However, for a long time I felt like I didn’t belong here, and I didn’t belong in Mexico, either. Navigating two worlds was not precisely difficult but sometimes unsettling . You spend your time “live switching” from English to Spanish to Spanglish and back again. You mix Cholula with Five Guys hamburgers. You watch American soccer but listen to the Mexican commentators (otherwise it’s like listening to golf announcers). And you truly think Mexican soccer fans are like the old Oakland Raiders fans, only worse. Women in Mexico are as rabid fans as many men, but, at least back in my day (I feel ancient now), you didn’t see many women go to the stadiums. As a woman, I never felt safe. I only went to a match if my male friends went with me. This is one of the most striking differences between the U.S. and Mexico: American soccer fans are so mild-mannered in comparison!

Another striking difference I noticed when I first came to the U.S. was that I was not getting cat calls out when I was out walking in the streets. In Mexico, everywhere I went (since I was a preteen, for goodness’ sake), I would be subjected to cat calls and whistles – and the harassment only got worse the older I got. My experience as a woman was of always being on high alert. But when I came to the U.S., I felt respected. I could exist without being harassed continually. Women here seemed to have a voice and the same opportunities as men to grow and pursue their dreams. I felt free to pursue a career and to not be expected to only dream of marrying and having children. Although, over the years, I’ve come to realize there still is much room for improvement.

Back in the 1500s La Malinche did what she could to survive (did I say historians think she died before she was 30?). History asked her to do a task she didn’t want, and she did her best. I am sure she considered her options and bought time, respect and the right to live in the best way she could. She used her skills to earn a place in history, and although her role continues to be debated, I cannot blame her. Did I turn my back on my country? Or did I look for a better life? My circle of Latina friends in the U.S. is full of intelligent, professional women who left their countries and built a better life – a different life – here in the United States. They all miss their families, and they all support their biological families in many ways. What they can do from here, however, is more than they could have done had they stayed in their countries of origin.

Being Latina in America is both an honor and a challenge. We struggle with the dualities of our worlds. We struggle with the adjectives that define us. We are a complex mix of races, traditions and experiences. We care for our people, and we work tirelessly to do what must be done to help each other. The complexity of our identities can help us create a better world for all of us, a world where our differences are not viewed as a threat but as an asset. A world where we all thrive. ¡Sí, se puede!

By: Claudia Ortega-Lukas Graphic Designer & Communications Professional

bodymind Aiyana Graham

University Undergraduate Researcher and NURA awardee learns through and creates art highlighting the marginalized

Active Assailant Training Helps Community Member

The Active Assailant Training from the University Police Department – Northern Command helped prepare this individual to stay safe

Libraries IDEA Committee to celebrate PRIDE through student art

Libraries IDEA Committee to celebrate “What does PRIDE mean to you” through student art contest

Finding and catching endangered frogs in Panama

A University team of women scientists traveled to El Valle de Antón for ongoing research on a pathogen killing different amphibian populations

Editor's Picks

Remembering the Holocaust

Earth Month events focus on increasing campus sustainably, gardening, thrifting and more

Anthropology doctoral candidate places second in regional Three-Minute Thesis Competition

A look at careers of substance and impact

Nevada Today

A glimpse into Korea comes to the University campus

Korea Wave/The Korean Film and Food Festival to be held on May 2

Sci-On! Film Festival returns to Fleischmann Planetarium May 1 – 4

The festival will feature a NASA space film, introductions from directors, receptions, refreshments and live music

Put the person first: M.D. student encourages others to pursue a career that aligns with their values

Spencer Joseph Horsley Trivitt, class of 2024, shares the importance of following one’s internal compass

Catalyzing carbon and plastic recycling

Energy Solutions Forum speaker Karen Goldberg spoke about the methods her lab is pursuing to recycle carbon and plastic

Creating quantum sensors - chemistry meets physics

Chemistry professor and colleagues awarded NSF grant to build quantum device

University of Nevada, Reno Extension appoints new state leader for Nevada 4-H

Lindsay Chichester to foster growth of the youth development group

The 2024 Cashman Good Government Award awarded to the University of Nevada, Reno Collegiate Academy program

Recognition of the program highlights its success in Nevada high schools.

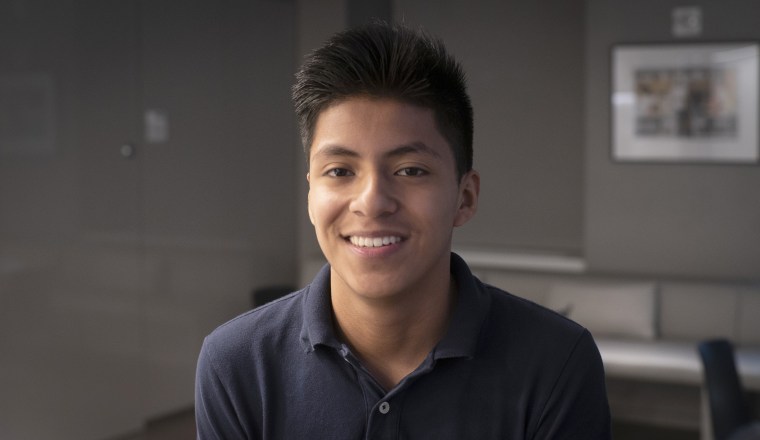

Faces of the Pack: Michael Esquejo

Counselor Education and Supervision doctoral student selected for emerging scholar program

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How the Chicano Movement Championed Mexican-American Identity and Fought for Change

By: Karen Juanita Carrillo

Updated: July 25, 2023 | Original: September 18, 2020

In the 1960s, a radicalized Mexican-American movement began pushing for a new identification. The Chicano Movement, aka El Movimiento , advocated social and political empowerment through a chicanismo or cultural nationalism.

As the activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales declared in a 1967 poem , “La raza! / Méjicano! / Español! / Latino! / Chicano! / Or whatever I call myself, / I look the same.”

Leading up to the 1960s, Mexican-Americans had endured decades of discrimination in the U.S. West and Southwest. After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo put an end to the Mexican-American War in 1848, Mexicans who chose to remain on territory ceded to the United States were promised citizenship and “ the right to their property, language and culture .”

But in most cases, Mexicans in America—those who later immigrated and those who lived in regions where the U.S. border shifted over—found themselves living as second-class citizens. Land grants promised after the Mexican-American War were denied by the U.S. government, impoverishing many land-grant descendants in the area.

Not White, But ‘Chicano’

Throughout the early 20th century, many Mexican-Americans attempted to assimilate and even filed legal cases to push for their community to be recognized as a class of white Americans, so they could gain civil rights. But by the late 1960s, those in the Chicano Movement abandoned efforts to blend in and actively embraced their full heritage.

By adopting “Chicano” or “Xicano,” activists took on a name that had long been a racial slur—and wore it with pride. And instead of only recognizing their Spanish or European background, Chicanos now also celebrated their Indigenous and African roots.

Leaders in the movement pushed for change in multiple parts of American society, from labor rights to education reform to land reclamation. As University of Minnesota Chicano & Latino Studies professor Jimmy C. Patino Jr. says, the Chicano Movement became known as “a movement of movements.” “There were lots of different issues,” he says, “and the farmworker issue probably was the beginning.”

Chávez Leads Fight for Farmworkers’ Rights

César Chávez and Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which later became United Farm Workers (UFW) in California to fight for improved social and economic conditions. Chavez, who was born into a Mexican-American migrant farmworker family, had experienced the grueling conditions of the farmworker first-hand.

In September 1965, Chávez lent his voice to a strike for grape workers , organized by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a predominantly Filipino labor organization. With the help of Chávez’s advocacy and Huerta’s tough negotiating skills, as well as the persistent hard work of Filipino-American organizer, Larry Itliong , the union won several victories for workers when growers signed contracts with the union.

“We are men and women who have suffered and endured much and not only because of our abject poverty but because we have been kept poor,” Chávez wrote in his 1969 “Letter from Delano.” “The color of our skins, the languages of our cultural and native origins, the lack of formal education, the exclusion from the democratic process, the numbers of our slain in recent wars—all these burdens generation after generation have sought to demoralize us, we are not agricultural implements or rented slaves, we are men.”

Tijerina and the Push for Land Reclamation

Next to labor, the land itself held important economic and spiritual significance among Chicanos, according to Patino. And civil rights activist Reies López Tijerina led the push to reclaim land confiscated by anglo settlers in violation of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Tijerina, who grew up in Texas working in the fields as young as age 4, founded La Alianza Federal de Mercedes (the Federal Land Grant Alliance) in 1953 and became known as “King Tiger” and “the Malcolm X of the Chicano Movement.” His group held protests and even staged an armed raid on a small town in New Mexico, trying to reconquer properties for the Chicano community.

While efforts to repatriate land got caught up in the courts, Patino says, “it had this big effect in terms of mobilizing young people to understand the ways the U.S. took land from Mexico—and from Mexican landowners in particular—and how this kind of empire-building was how Mexicans became part of the U.S.”

Student Movement Embraces ‘Aztlán’

Meanwhile, a parallel effort, led by poet and activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, organized Mexican-American students across the country. In a March 1969 gathering, some 1,500 attended the National Youth and Liberation Conference in Denver, Colorado. At the conference, the students looked to their indigenous ancestors of the Aztec Empire and identified a land called “Aztlán.”

In Aztec folklore, Aztlán was believed to have extended across northern Mexico and possibly farther north into what is now the U.S. southwest. The students embraced the concept of Aztlán as a spiritual homeland and drafted El Plan Espiritual De Aztlán as their manifesto for mass mobilization and organization.

Ultimately, the Chicano Movement won many reforms: The creation of bilingual and bicultural programs in the southwest, improved conditions for migrant workers, the hiring of Chicano teachers, and more Mexican-Americans serving as elected officials.

“A key term in Chicano Movement activism was self-determination,” says Patino, “the idea that Chicanos were a nation within a nation that had the right to self-determine their own future and really their own decisions in their own neighborhood, in their own barrios.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Becoming Mexican American Essay

In the book Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, George J. Sanchez, associate professor of American studies, ethnicity and history at the University of Southern California, studies the historical formation of the Mexican American identity, specifically in the first half of the 20 th century.

The city of Los Angeles during that time period in history was the hub of an intense and multifaceted cultural interplay between the indigenous American culture – rooted as it has been since its inception in the experience of the immigrant – and the influx of Mexican people that comprised the city’s most significant immigrant population at the time.

In choosing to focus on the years between 1900 and 1950 in Los Angeles, Professor George J. Sanchez specifically highlights a number of significant aspects that formed the Mexican American identity: war, repatriation, popular culture and Americanization programs.

The formal deportation and repatriation campaigns that took place during the Great Depression in the 1930s forced thousands of Mexicans back to the country of their birth; those who managed to stay in Los Angeles lobbied for civil and labor rights as Mexican Americans through unions and the policies associated with Roosevelt’s New Deal programs (Sanchez 12).

Professor George J. Sanchez’s broader argument on how identity is created offers a view of identity for Mexican immigrants during this time period as an amalgamation or third way between life as a Mexican and life as an American.

In George J. Sanchez’s words, “as Mexican immigrants acclimated themselves to life north of the border, they did not remain Mexicans simply living in the United States, they became Mexican Americans. They assumed a new ethnic identity, a cultural orientation which accepted the possibilities of a future in their new land” (Sanchez 12).

The purpose of this essay is to answer the question, is the Mexican American entertainer Pedro J. Gonzalez Mexican or American? This essay begins with George J. Sanchez’s supposition and builds upon it, as it employs certain events from Pedro J. Gonzalez’s life, specifically, his emigration to the United States, his deportation and his citizenship in 1985, to argue that Pedro J. Gonzalez was ultimately an American.

The essay reaches this conclusion on account of two key choices that Pedro J. Gonzalez made: the first, his choice to return to the United States following his deportation, and the second, his choice to become an American citizen in 1985 (Waldo and Sullivan 3).

This essay also argues that Mexican immigrants such as Pedro J. Gonzalez employed popular culture, particularly the corrido – the Mexican folk song – to serve as a bridge between the two cultures, and in turn the corrido came to underpin many elements of the new Mexican American identity as it formed.

Pedro J. Gonzalez was born in Chihuahua, Mexico in 1895; during his teenage years Gonzalez became a freedom fighter with other Pancho Villa supporters during the Mexican Revolution from 1910 through 1920 (Waldo and Sullivan 3).

A woman saved Pedro J. Gonzalez from a firing squad in 1919; three months later they were married and moved to Los Angeles in 1923, where he found employment as a longshoreman (Waldo and Sullivan 3). Pedro J. Gonzalez embarked on a radio career in Los Angeles as a Spanish-language radio personality in 1932, hosting his own two hour morning show on the Burbank based radio station KELW (Waldo and Sullivan 3).

The primary audience for Pedro J. Gonzalez’s radio show was the Mexican laborer getting ready for work in the morning; Pedro J. González was also the front man for a band called Los Madrugadores (Waldo and Sullivan 3). This radio show soon operated as a news resource for the burgeoning population of Mexicans in Los Angeles – a number of whom were illiterate in both languages – and Pedro J. Gonzalez deployed th

Open conflicts soon developed between Pedro J. Gonzalez and the Los Angeles municipal power base, specifically District Attorney Buron Fitts (Waldo and Sullivan 3). In 1934, Fitts arrested Pedro J. González on sexual assault charges; the court sentenced him to fifty years, six of which he served in the San Quentin prison (Waldo and Sullivan 3).

Pedro J. González regained his freedom in 1940, whereupon he was deported to Mexico; he spent the next thirty years in Tijuana as a radio personality (Waldo and Sullivan 3). Despite the deportation, tantamount to exile, Pedro J. González chose to return to Los Angeles in 1971; he applied for and received his American citizenship in 1985 (Waldo and Sullivan 3).

Choice here is the operative word when deciding what constitutes identity. Gonzalez chose willingly to return to the United States despite his fractious relationship with the authorities in Los Angeles and the hardship he faced, particularly the time he served in the San Quentin prison, an indication that he personally identified as an American, otherwise he would have stayed in Mexico.

Pedro J. Gonzalez employed the corrido, a form of folk music popular among the Mexican working classes, as a kind of political forum. In Professor George J. Sanchez’s words, “the corrido was an exceptionally flexible musical genre which encouraged adapting composition to new situations and surroundings.

Melodies…were standardized or based on traditional patterns, while text was expected to be continually improvised…corrido musicians were expected to decipher the new surroundings in which Mexican immigrants found themselves while living in Los Angeles. Its relation to the working-class Mexican immigrant audience in Los Angeles was therefore critical to its continued popularity” (Sanchez 178).

Pedro J. Gonzalez was one of the core innovators of the corrido genre, and employed the genre regularly throughout his career to communicate the distinct experience of the Mexican immigrant (Sanchez 177). According to Sanchez, Pedro J. Gonzalez “remembered composing corridos with seven other soldiers fighting with Pancho Villa in secluded mountain hideouts during lulls between battles” (Sanchez 177).

The corrido formed a cultural bridge between the Mexico that Pedro J. Gonzalez’s audience had left behind and the new identities and lives they were constructing in Los Angeles. In essence the folk songs made sense of the new surroundings for the Mexican immigrants, while maintaining a vibrant connection with the home culture.

In the book Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, Professor George J. Sanchez examines an important period of Mexican American history, the first half of the 20 th century, localized in Los Angeles, as well as an important cultural and political figure from that time, Pedro J. Gonzalez.

Despite the difficulties Pedro J. Gonzalez faced at the hands of corrupt city officials, which led to a six year jail stint at San Quentin, Gonzalez’s actions – returning to the United States and applying for and receiving his citizenship in 1985 – demonstrated that he himself identified as an American.

Works Cited

Martin, Waldo E. Jr. and Patricia Sullivan. “Pedro J. González.” Civil Rights in the United States . New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2000. Print.

Sanchez, George J. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 16). Becoming Mexican American. https://ivypanda.com/essays/becoming-mexican-american/

"Becoming Mexican American." IvyPanda , 16 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/becoming-mexican-american/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Becoming Mexican American'. 16 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Becoming Mexican American." October 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/becoming-mexican-american/.

1. IvyPanda . "Becoming Mexican American." October 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/becoming-mexican-american/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Becoming Mexican American." October 16, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/becoming-mexican-american/.

- The Chicano Movement

- Chicano Movement: Historical Development and Importance

- The Chicano Movement (1965-1970)

- Chicano Figures in Modern American History

- The Art of Frida Kahlo and Chicano Art

- Chicano Struggles and Leaders in the 20-21st Centuries

- Chicano Discrimination in Higher Education

- The Analysis of “Titled My Bloody Life: The Making of a Latin King” by Reymundo Sanchez

- Emilia Sanchez: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Lalo Guerrero: the Father of Chicano Music

- Essay About Immigration Causes and Effects

- Illegal Immigration: Views of Policy Makers, Media and General Public

- White Australian Policy

- The Impact of Immigration on the Economy of the USA

- Addressing the Issue of Illegal Migration

Chapman University Digital Commons

- < Previous

Home > Institutes and Centers > Center for Undergraduate Excellence > Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters > 559

Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters

The subjective variation among mexican american identity: a comparative analisis between the autobiographical works of richard rodriguez and reyna grande.

Victor Leon , Chapman University Follow

Document Type

Publication date.

Fall 11-30-2022

Faculty Advisor(s)

Dr. Laura Loustau

The population of people who identify as Mexican American has steadily grown parallel to the increase of Mexican immigration to the United States. Ever since the creation of the racial-social group known as Mexican Americans and their subsequent growth, a vast amount and variety of scholarship has been written on what it means to identify as Mexican American. This essay aims to focus on how childhood experiences and development directly impact one's subjective view of Mexican American identity. Understanding Mexican American identity as a clash of two different cultures, Mexican culture and conventional American culture, this essay will perform an analysis and comparison between the autobiographical works of two Mexican American authors, Richard Rodriguez’s Hunger of Memory (1982) and Reyna Grande’s The Distance Between Us (2012), using a specified array of theories that help define the blending of two different cultures, such as acculturation and transculturation. There will be a specified focus on two aspects of childhood development, education and personal family experiences. The objective of this essay is to demonstrate that Mexican American identity should not be viewed as a singular phenomenon or a type of “common struggle”, but as a subjective personal belief that creates unique points of view of what it means to be Mexican American. One example of this phenomenon that this essay will cover is the differences in political and social opinions among the Mexican American community. A comparison of these two authors will demonstrate how their personal views of Mexican American identity caused them to develop contrasting political and social opinions.

Presented at the Fall 2022 Student Scholar Symposium at Chapman University.

Recommended Citation

Leon, Victor, "The Subjective Variation Among Mexican American Identity: A Comparative Analisis Between the Autobiographical Works of Richard Rodriguez and Reyna Grande" (2022). Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters . 559. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts/559

Since December 14, 2022

Included in

Latina/o Studies Commons , Race and Ethnicity Commons

- Collections

- Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- Submit Research

- Rights and Terms of Use

- Leatherby Libraries

- Chapman University

ISSN 2572-1496

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

What are you looking for?

David A. Romero grew up with his working-class Mexican American parents and three siblings in Diamond Bar, California. (Photo/Gus Ruelas)

One Mexican American’s Identity Struggle: Confronting Race and Belonging

Thoughts on speaking Spanish and passing as white all come out in a starkly honest Q&A with spoken word artist and USC alum David A. Romero.

David A. Romero ’07 held stereotypes as a kid. He admits it.

Today, the spoken word artist shares them honestly in his work. Like the time he sparked a huge fight by condemning his dad’s hairy arms. Or his misguided belief that only “stupid people spoke Spanish,” which led him to study French instead. His recently published poetry collection with FlowerSong Press, My Name Is Romero , picks apart these views, bringing them into the open.

Romero, who studied philosophy and film at USC, is a passionate activist and speaker on issues of immigration and economic justice. His three poetry anthologies explore Latinx culture, identity and colonialism. In an era of cancel culture, Romero lays bare the conflicting feelings he had growing up as a Mexican American in Diamond Bar, California. He spoke with USC Trojan Family writer Gustavo Solis about how he hopes his poetry’s honesty will inspire others to reflect on their unconscious biases and change the way we approach race and identity.

Tell me about this idea of identity and belonging. Why do you think it’s so much of a focus for everyone?

It’s what gives life purpose, it’s what gives you joy — knowing that you are part of a family or group, or you have a cause larger than yourself. Some ideal that you hold to that gives you purpose.

I think we all strive for a sense of belonging. I think belonging is what gives our life meaning and purpose. And identity very often is that entryway or the thing that obstructs us — the gate — to a sense of belonging. One identity will include us in something or exclude us from something else.

Your poems I love most are the personal ones, particularly of you growing up and forming your identity. You really put yourself out there. I specifically remember you talking about learning French instead of Spanish when you were a kid. Tell me a little bit about that.

The eldest of my two sisters, who I was closest to early on, she had made a choice at a certain point to learn French. She made this decision — I guess she took an interest in French culture — and she was always a huge influence on me.

I think at that time, I had this perception, and it’s a line in the poem: “Spanish was the back side of a Latin coin never to turn up.” It was this very cowardly way of looking at the world, that French was a more useful language or a language that more people would accept or be interested in.

Tell me more about your view of Spanish when you were a kid. I ask because immigrants from a certain era were told not use it at all because they’d get unwanted attention. They didn’t pass it on to their children because of that.

To say it outright, we were conditioned to think that stupid people spoke Spanish because that was the prejudice growing up in an upper-middle-class neighborhood. We were taught even as Mexican ourselves to look at other Mexicans as inferior. And it is very often a multigenerational Mexican American outlook to want to integrate and assimilate as much as possible. So, the idea is to abandon Spanish quickly.

You mentioned your sister having darker skin than you. I noticed a couple of times you referenced yourself as “the white, blue-eyed Mexican.” How did that influence your sense of identity, and how did you deal with this idea of “I don’t look Mexican”?

For me, much of my life has been lived as a white person — in the way that people interact with me because I can’t speak Spanish, because of the way that I look. It really gave me insight into the way white people think. But finally, I got to a point where I started to break away from that — I did not want to be that.

When I talk about that, I often get pushback from white people. They normalize their centrality within the world, within the universe. There’s a certain way of looking at the world — a mind frame of “There’s me and us, and then everyone else.” And you’re either closer to that or on some gradient other than that.

Even among the most well-meaning, it’s like an unconscious reflex, and I still find it within myself. … I still have a lot of knee-jerk responses to certain things that are deeply conditioned.

Give me an example of a knee-jerk reaction you’ve had.

One big thing is even with Spanish itself. If I’m entering into a context where I am not prepared for Spanish to be the norm in this environment, that this is what should be spoken and it catches me off guard, there is this reflex of “Oh, that’s other.” It has all of these different connotations.

So, it would be like walking into a taco shop where everyone is speaking Spanish. For a second, you think this is something else, this is exotic, this is not normal.

In your poem “gorilla arms,” you reflect on a childhood experience of criticizing your dad for having big, hairy arms. did that really happen.

Yeah, it really did happen. I really do remember saying that to him. And I remember that being part of it, this connection that I had made in my mind as a child between animals and race. That is another form of racism, of course, is dehumanization.

When I said that, I think it was because I said it with such disdain. I really meant that there was something about having these hairy arms, about having these gorilla arms that made him less than. That I thought I was better than him and there was something disgusting about having these hairy arms.

I remember knowing that what I had said had meant something really bad. It wasn’t a racial epithet, but it was racially motivated. I remember just running out. And a lot of it was just the conflict, too, and being yelled at back.

Did you have any reservations about writing that, sharing that with the world? I ask because we live in an age where people get “canceled” for saying stuff like that.

Absolutely. A lot of it is that I can’t help it. I do have a tendency to put my foot in my mouth, to say too much. I think that is my kind of nature to a certain degree.

But sometimes we do need to question ourselves. A lot of important work does get done by projecting things onto others or describing the wrongdoings of others. I was raised Roman Catholic, and even though I identify as an atheist now, a lot of that sticks with me — what I have done and what I have failed to do, that Catholic guilt, the need to examine oneself and hold oneself responsible.

If you see the faults of racism in others, chances are they also exist somewhere in yourself. Of course, that is not the case with everyone — but it is the case with certain people more than others.

But I definitely knew that it was there in myself, and I brought up that defensive thing that a lot of Caucasians have when you talk about racism. I found that by saying that I’ve had some of these same problems, it made them free to open up and we can talk about it.

But more, it’s within our own communities, it’s upon our own people that we have these things deeply embedded, even if we are in activist circles. We still carry these same beliefs that were indoctrinated into us over centuries of colonization and class systems.

If we can talk about these things, then we can start to deconstruct them, then end them.

Editor’s note: This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Related Articles

L.a. times book prize winners named in ceremony at bovard auditorium, music and culture at the los angeles memorial coliseum, 2 usc faculty members named 2024 guggenheim fellows.

- Campus News

- Campus Events

- Devotionals and Forums

- Readers’ Forum

- Education Week

- Breaking News

- Police Beat

- Video of the Day

- Current Issue

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- The Daily Universe Magazine, December 2022

- The Daily Universe, November 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, October 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2022 (Black 14)

- The Daily Universe Magazine, March 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, February 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, January 2022

- December 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, November 2021

- The Daily Universe, October 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2021

- Hope for Lahaina: Witnesses of the Maui Wildfires

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial

- The Black 14: Healing Hearts and Feeding Souls

- Camino de Santiago

- A Poor Wayfaring Man

- Palmyra: 200 years after Moroni’s visits

- The Next Normal

- Called to Serve In A Pandemic

- The World Meets Our Campus

- Defining Moments of BYU Sports

- If Any of You Lack Wisdom

- Uncategorized

Mexican and American: The challenges of belonging to two cultures

Fourteen years ago, Maria del Rosario Jasso from Coahuila, Mexico, realized her dream of moving to the United States with her husband and son. The couple had three more children after moving to the states and had to face an unexpected challenge: teaching their children Spanish and Mexican culture while residing in the United States.

Mexicans are the largest group of immigrants in the United States. Mexican immigrants to the U.S. added up to 11.4 million in 2008 (30.1 percent of the immigrants in the country), which meant about 10 percent of the Mexicans in the world, according to migrationpolicy.org.

“The main definition of American is if you were born in the United States, but now people can have dual citizenship and vote in both countries,” said Jacob Rugh, a professor of sociology at BYU who specializes in Latin American studies.

In Utah, 87.1 percent of children with immigrant parents were U.S. citizens in 2009, according to data from the Urban Institute.

The children of these immigrants can have dual citizenship and belong to two cultures. They were born in the United States, can vote in elections, and go to school where they learn American history and geography; but their heritage and ethnicity is still Mexican. They are part of a group called Mexican Americans. These children might face some challenges in living and integrating in both cultures.

“I know from some studies that people are judged by both the receiving country culture and also the home country culture, and people expect them to assimilate into both cultures,” Rugh said.

The movie “Selena” (1997), directed by Gregory Nava, portrays the story of a Mexican American singer who reached fame and success in in the United States and Latin America. It depicts some of the challenges Mexican Americans face including that Mexicans expect them to speak Spanish perfectly and know all about Mexico, while Americans expect them to speak English just as well and know all about the United States. In the movie, being a Mexican American is described as “exhausting.”

Because some immigrant parents do not speak English, their children have to take care of phone calls, people who come to the door and other tasks requiring an english speaker.

“Many children have to take a parent role, and they may sometimes know more information than their parents,” Rugh said.

Jasso said her two younger sons who still live with her find some aspects of being Mexican easy, but others increasingly hard.

“They don’t want to wear Mexican clothes and listen to Mexican songs, but they love tacos and other Mexican dishes,” she said.

David Jasso, Maria Jasso’s youngest son who is nine, said most of his friends are Americans but he feels comfortable speaking both languages. He also said he considers himself to be American because he was born here, albeit a different kind of American because of his strong connection with the Mexican culture.

The Jasso family has visited Mexico recently, but the children do not view the country in a positive light.

“There were too many dogs on the street,” said Brandon Jasso, who is 11 and attends Franklin Elementary School in Provo.

Not many Mexican Americans have the same opportunity to visit the country their parents are from, making them unaware of cultural aspects such as expressions and songs.

“Many of the Mexican Americans don’t have connections with Mexico except for the language and food, so when I make cultural jokes, they don’t understand,” said Alejandra Bradford, a Mexican from Guanajuato, Mexico, who moved to the United States to go to BYU, married an American and will have Mexican-American children.

Bradford said she and her husband will work hard to help their children love Mexico and be part of its culture.

“Me and my husband love Mexico, and we will visit it a lot so my children will feel more connected with it,” she said.

Brandon and David Jasso plan to live in the United States all their lives; that would help them avoid a problem Mexican Americans face if they go back to Mexico.

“I have read about some families who had to go back to Mexico because of the economic recession, and the Mexican American children didn’t really have an identity in Mexico,” Rugh said. “We can’t follow up to what is happening to them now, but I bet it is different going to Mexico because in here they can do karate and get trophies and in there the school system is different, so it presents challenges in a global society.”

Whether in Mexico or the United States, Mexican Americans continue to face challenges. The future will show how well the Mexican culture will blend with the American one.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

April is earth month: professionals reflect on nature’s transformative power, ‘the american diet is dangerous’: what to eat instead, according to joel fuhrman, an inside look at former byu professor, artist.

Young Latinos: Born in the U.S.A., carving their own identity

This report is part of #NBCGenerationLatino , focusing on young Hispanics and their contributions during Hispanic Heritage Month.

Jason Mero, 18, headed off to Brown University this fall proudly staking claim to his Latinx heritage, ever mindful that the sacrifices his immigrant parents made opened the doors of the Ivy League to him.

Born in Queens, New York, to parents who emigrated from Ecuador 30 years ago, Mero would ruminate with his family growing up about the challenges facing an American with Hispanic roots: how to deal with a more hostile environment against Latinos, and how to assert his U.S. citizenship, his birthright, while staying connected to his community.

"My family growing up wanted me to stick with my Hispanic roots, but also did not want me to show those roots to the world outside," Mero told NBC News. "They knew that being Hispanic-American isn't necessarily looked (upon) with a smile ... in this country. So they were doing that for my safety and to protect me. But even so, these conversations have shown me that I'm still proud of being Hispanic, even though it's being frowned upon by other people."

One million Hispanic-Americans will turn 18 this year and every year for at least the next two decades, said Mark Hugo López, director of global migration and demography research at the Pew Research Center. That stream of adolescent Latinos coming of age in the U.S. started a few years ago and is now gushing.

“This won’t be a passing wave," Lopez said, "but instead an ongoing process over the next 20 years as the young Latino population enters adulthood."

Although percentage-wise Asian Americans are the nation’s fastest-growing minority group, the Latino population will add more people each year to the U.S. than any other group for the next few decades, and their median age is younger than Asian Americans, according to Pew Research Center.

Most of these young Latinos have one thing in common — they were born in the United States.

Nine out of ten Latinos under 18 are U.S. born.

For those under 35, it's about eight in ten, according to new figures from Pew Research Center .

Over half of Latinos under 18 and roughly two-thirds of Latino millennials are second-generation Americans — born in the U.S. to least one immigrant parent.

“These young Latinos are U.S. born, going through U.S. schools,” Lopez said, “yet they grew up in Latino households, exposed to the culture of their parents’ home country — that is the distinguishing point. They have all the markers of being American, yet they are the children of immigrants.”

Navigating their parents' immigrant culture while being born and raised in the U.S. has shaped their views on identity and what it means to be an American — factors that are, in turn, shaping the nation’s adult workforce and electorate.

Juggling language, color, culture

Like other population waves throughout the country’s history, these young bicultural Americans are coming of age enmeshed in their Latino and American worlds and trying to carve out a place for themselves in both of them and between.

Berenize García, 16, of New York City, said her father, a Mexican immigrant, has pressured her to be “more American,” while her mother told her it’s disrespectful not to retain and speak Spanish to their Mexican relatives.

“That makes me feel confused, because how can I be Mexican when I’m pressured to be more American? How can I be American when I’m pressured to be more Mexican?” she said.

Her confusion is captured in a scene from the 1997 movie "Selena," in which actor Edward James Olmos, playing a father, tells his children how difficult it is to be Mexican-American and the nonacceptance that comes from both Mexico and the United States: "We have to be twice as perfect as everybody else."

These experiences with language and culture have imprinted themselves on García and have affected how she sees her future.

“I’m trying to, hopefully, one day become a doctor, and in that way empower my patients who have that language barrier, because my mom, who goes to the doctor constantly, can’t really express her pain because she doesn’t speak English,” García said. "Her pain is brushed off.”

While this younger generation of Latinos is more conversant in English than their immigrant parents’ generation, three-in-four young Hispanics say they use Spanish as well, according to Pew.

Toggling between two languages — and that it’s hard to be truly bilingual — is perhaps one of the most common threads growing up for these young Latinos.

“We’re stripped in a lot of cases of our Spanish tongue and our Spanish heritage and told it’s really important that you only speak English and you know how to speak English well because otherwise, you’re going to face hardship, which is in a lot of ways true because of the prejudice that this country holds,” said Alma Flores-Perez, 21, born and raised in Austin, Texas.

“But at the same time, I’ve really come to see the importance of speaking Spanish or at least trying to claim that as our own and not be ashamed when you do speak Spanish, but also not being ashamed if you weren’t taught it, because that wasn’t necessarily your choice,” Flores-Perez said. She thinks her bicultural upbringing is one of the reasons she’s majoring in linguistics at Stanford.

Even more of an impact than language, for many young Latinos, is how their skin color influences how they’re perceived, not only by other Americans but by other Hispanic Americans.

Flores-Perez, who is light-skinned, has been questioned when she identifies herself as Chicana.

"I’ve been called whitewashed,” said Flores-Perez, who said it hurt to not be considered Latina enough because of her light complexion. But she’s come to understand it’s not something she can control.

“I think I can do my best to project that identity and to make clear who I am and explain when people ask,” she said.

Christopher Robert, 18, of Brooklyn, whose mother is Dominican and father is Puerto Rican, said, “There are a lot of people in my family who have a dark skin tone, but still, like, insist that they’re part of a white Latino population."

Robert, who describes himself as Afro-Latino, added, “I choose to acknowledge it and accept it as part of who I am.”

Leyanis Díaz, 25, is an Afro-Latina blogger and entrepreneur based in Miami who was born in Cuba and came to the United States with her family when she was 3.

"I had people tell me they didn’t even know that there were black people in Cuba, which made me really feel ...,” she said pausing. “It gave me self-esteem issues, for the most part.”

That didn't stop her from entering, and winning, the Miss Black Florida USA pageant last year. “In all honesty, the way I’ve combated these stereotypes is by continuing to educate not only my friends, but the people that I encounter —educating them about Cuba, where I come from, teaching them more about my culture,” Díaz said.

Many young Latinos see themselves as in-between skin colors and races.

Jeanette Garzón Terreros, 18, a freshman at Columbia, said that when she's filled out certain forms, she has left blank the questions on race or ethnicity.

“I don’t identify as white, I don’t identify as black, I don’t identify as any of the things, and they don’t put an ‘other,’” she said. Garzón Terreros said she saw a picture of the part of Mexico that her parents are from, and the people looked part indigenous, part Spanish. “It’s like the mix between the two races.”

Experiences shape their outlook

Beyond issues of language and color, living amid their immigrant parents and their extended network has influenced how young Latinos see issues in the U.S. and beyond.

Some recounted, amid smiles, growing up as Latinos while not necessarily embracing their families' traditions. "I don't dance; salsa, nothing," said Christopher Robert. "I don't know how to cook Dominican food or anything."

More seriously, they spoke of the pressure their parents felt to help relatives in their home countries, despite not having much more money themselves.

They also spoke of having to explain their identity not just in their U.S. neighborhoods, but in their parents' home countries, to family members who questioned their accents or status based on their U.S. experience.

Here at home, U.S.-born young Latinos also grow up with the reality that depending on their family or friends' immigration status, they could one day be taken by immigration enforcement officers, held in detention for long periods and possibly deported.

With community if not familial ties to immigrants — including legal residents without documents and people with deportation deferrals — detentions and deportations or the fear of them are part of young Latinos' daily lives.

Flores-Perez said she was "really rocked" when President Donald Trump brought up trying to rescind the DACA program, Deferred Action for Child Arrivals, which allowed undocumented young people brought to the U.S. as children to remain in the country.

Latino A Chicano renaissance? A new Mexican-American generation embraces the term

Her best friend, from Honduras, was a DACA student. "I was terrified, and she was terrified because she’s been here since she was 2 years old. This country is all she knows,” said Flores-Perez.

A survey of millennials released in January found that 49 percent of millennial Latinos worried a lot that a family member or close friend could be deported, compared to 25 percent of Asian Americans and 21 percent of African-Americans. White millennials' experience was the polar opposite to Latinos: Fifty percent said they did not know anyone at risk of being deported.

Young adults under 35 are already the most diverse generation in U.S. history, according to Stella Rouse , a University of Maryland political scientist. The diversity has found its way into politics and policy making and is likely to give a distinct shape to how the country addresses major issues.

In her new book, “The Politics of Millennials" — written with Ashley D. Ross, an assistant professor at Texas A&M University — Rouse argues that millennials' diversity, combined with growing up amid the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the Great Recession and the debate over immigration, “simply guides a lot of attitudes and policy preferences.” This includes their views on the economy, the role of government in providing opportunities and how to deal with a lack of access to health insurance.

Rouse sees the influence of diversity and upbringing in young Latinos’ attitudes toward climate change, for example.

The share of Latino millennials who believe climate change is occurring is about 49 percentage points higher than white millennials and 20 percentage points higher than African-Americans.

Young Latinos may be disproportionately affected by climate change considering where they live, how many of them or their families are employed in the agricultural industry and that they have relatives in other countries that have experienced climate-related issues, Rouse said.

Challenges and opportunities

As with every generation, a young person’s trajectory is eventually tied not only to their prosperity but to the country’s economic success. When looking at the nation’s Latino youth, there are challenges and there are opportunities, according to Pew Research’s López.

On the one hand, a record number of young Latinos, 3.6 million in 2016, are attending college, and their share is growing, according to Pew. Additionally, 67 percent of Latinos ages 25 and older had earned a high school degree.

Yet they lag behind other groups in pursing higher education. Just 17.2 percent of Hispanic adults have a bachelor's degree and 5 percent an advanced degree, compared to 38.1 percent and 14.3 percent of non-Hispanic whites, according to the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities.

One of the biggest issues is college costs, complicated by the fact that Latino families, which generally started the Great Recession with less net worth than other ethnic groups, lost 66 percent of their household wealth during this period.

“I’m at Northeastern right now — I’m only here because there was a good financial aid package, and even so it was extremely expensive," said Robert, the Brooklyn teen . “Before I made my decision, I sat down with my mom and asked her, ‘Are you sure you want to do this?’”

Despite financial odds, young Latinos are profoundly optimistic. More than three-in-four Hispanics ages 18-35 say most people who want to get ahead will be able to make it if they work hard.

Marco Garcia is Berenize's twin brother. He described their immigrant parents' hard work. “My dad works six days a week from 10 to 10,” Marco said. “My mom works as a housemaid, scrubbing floors, cleaning bathrooms and what not.”

When they were younger, Marco was embarrassed by his parents’ broken English when they came to school functions. Now he and his sister, students at Uncommon Charter High School in Brooklyn, see it as a point of pride that they're children of immigrants — as well as high achieving students.

“I feel very optimistic about the future,” Berenize said. “Our parents already did the majority of the work. All we’ve got to do is just finish it.”

FOLLOW NBC LATINO ON FACEBOOK , TWITTER AND INSTAGRAM .

- Palabra Final

- South America

- Central America

- Entrepreneurialism

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Immigration

- Social Justice

- Crowdfunding

Guest Voz: “You’re not really Mexican” – a personal essay about my cultural identity crisis

Latina Lista

In guest voz , znew headline.

By Sophia Campos VoiceBox Media

All my life I’ve lived between two worlds.

As a Mexican-American, it’s easy to be confused as to which world you think you should identify with more; I feel undoubtedly Mexican-American when I make tamales or listen to mariachis, but that feeling fades away when I speak broken Spanish.

Spanish might not seem like an important characteristic for all Mexican-Americans, but not knowing it in central Texas— an area where Spanish is spoken all over the region by Mexican-Americans —can surely make you feel like a foreigner.

Although I sometimes feel confused as to which world I belong to, there’s no question I’m first and foremost an American; I’m the product of my Mexican grandparents’ American Dream, I’ve never been to Mexico (besides Cancun, where there are probably more American tourists than Mexicans) and I can’t say certain words in Spanish without revealing my obvious American accent.

Growing up, I always lived in predominantly Caucasian neighborhoods in states that have very low Hispanic populations, thus the majority of my friends throughout my life have been Caucasian. I never really understood that I was any different than my Caucasian friends because we really weren’t. We lived in the same neighborhood, went to the same school, and our parents had similar jobs. We shopped at the same stores, joined the same clubs, and so on.

Even though we had similarities, I knew I was different because I looked different, ate different foods and my parents spoke Spanish to each other. I started realizing I also belonged to another world when my friends and I started hitting puberty, and they would complain about Mexicans whistling at them.

I’d ask, “Mexicans?” and they would say yes, it had to have been Mexicans because it happened at the construction site down the block. When I would respond defensively to their claims—because even at a young age I took offense to and recognized these stereotypes—they would reply with “well, you’re not really Mexican…you know what I mean!”

As a young girl, I wouldn’t argue further when I heard remarks like that, but I’ve always wondered: what did my friends mean? Did they mean that since my dad had a white-collar job, and since I spoke English without an accent like they did, that I must not have been of Mexican descent? What made them assume that all Hispanics were Mexican? Where did these warped stereotypes come from?

It’s not uncommon to find myself in these awkward situations; more recently I found myself the only Mexican-American among a group of Caucasian adults, who, as a result of my presence, were having a very restrained conversation about their “changing” neighborhoods, and their desire to move away because “the demographics” were shifting—which, I inferred, meant more Hispanics were moving in and they wanted to get out.

I feel an inherent responsibility to correct people when they categorize all Hispanics as Mexicans or when I hear an incorrect stereotype because I’m both offended and desperate to try and educate people about this topic. What puzzles me, though, is that although I feel alienated and oftentimes hurt when people make these remarks, I know that the people making them are also just like me. I have more in common with them than Mexicans.

What I’ve learned from living between these two worlds is that how you identify with someone isn’t necessarily based on race or ethnicity, it’s socio-economic class.

Sure, people of the same culture share traditions and practices, but what makes someone truly identify with someone else is sharing a similar lifestyle. A poor Caucasian kid will have more in common with a poor Mexican kid than with a rich Caucasian kid, no matter the cultural similarities or differences between them.

However, not many people look for similarities in people across cultures since our American history includes exclusion of so many groups, including Hispanics.

One of the most recent examples is Trump suggesting that Mexicans are “rapists” and “drug dealers.” Instances like this is no wonder that there might be a cultural divide between Mexican-Americans and Caucasians, and even confusion that Mexican-Americans are indeed just as American as everyone else.

Even though I sometimes face confusion about my cultural identity, I know that, after all, America is a melting pot. This debate within myself is the product of being fed the incessant mantra that we are truly a multicultural and diverse nation, and I’m sure Mexican-Americans aren’t the only ones in this country who experience this self-reflection.

I believe that this multiculturalism is what America has tried to achieve all along, and I believe that we are supposed to be a melting pot. This realization has made it easier for me to identify myself as Mexican-American; I know I can exist happily between these two worlds, accepting the American part of me as well as the fundamental Mexican part of me.

Sophia Campos is a 21-year-old student at Texas State University.

Share this:

Related posts

April 26, 2024

April 25, 2024, april 24, 2024.

- Google plus

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Race and Ethnicity — American Identity

Essays on American Identity

Hook examples for identity essays, anecdotal hook.

Standing at the crossroads of cultures and heritage, I realized that my identity is a mosaic, a tapestry woven from the threads of my diverse experiences. Join me in exploring the intricate journey of self-discovery.

Question Hook

What defines us as individuals? Is it our cultural background, our values, or our personal beliefs? The exploration of identity leads us down a path of introspection and understanding.

Quotation Hook

"To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment." These words from Ralph Waldo Emerson resonate as a testament to the importance of authentic identity.

Cultural Identity Hook

Our cultural roots run deep, shaping our language, traditions, and worldview. Dive into the rich tapestry of cultural identity and how it influences our sense of self.

Identity and Belonging Hook

Human beings have an innate desire to belong. Explore the intricate relationship between identity and the sense of belonging, and how it impacts our social and emotional well-being.

Identity in a Digital Age Hook

In an era of social media and digital personas, our sense of identity takes on new dimensions. Analyze how technology and online interactions shape our self-perception.

Identity and Self-Acceptance Hook

Coming to terms with our true selves can be a challenging journey. Explore the importance of self-acceptance and how it leads to a more authentic and fulfilling life.

American Identity in Mericans

Creating an american identity essay, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

American Identity in Sandra Cisneros Mericans

The way an american identity is created, characteristics that shaped an american identity, an overview of the evolution of the american identity, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Questioning The Identity: The Meaning of Being an American

What does it mean to be an american citizen, the rising of american identity, what america means to me, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The American Identity and The Role of The Foreigner in American Nation and Other Nations

An analysis of native american identity as a result of colonialism in sherman alexie's novel the absolutely true diary of a part-time indian, a discussion on latin americans developing their american identity, the view of frederick douglass on american identity, what it means to live in america, what it means to be an american today, the impact of class in social identity, representation of the american family in the works of roth and miller, my cultural identity: who i am, understanding the concept of the american dream, freedom as the root of what it means to be an american, what america means to you: education, rights, and equality, tocqueville on the toxicity of american ideals, american dream as an integral part of american ideals, the evolution of native american identity in joy harjo's poetry, establishment of american ideals during american revolution, the great gatsby: what it means to be an american in a negative connotation, italian-american identity in stallone's rocky, exploring america’s identity subjugation in "americanah", representation of toxic american masculinity in slaughterhouse-five by kurt vonnegut.

National identity can be defined as an overarching system of collective characteristics and values in a nation, American identity has been based historically upon: “race, ethnicity, religion, culture and ideology”.

Relevant topics

- Social Justice

- Effects of Social Media

- Discourse Community

- Sex, Gender and Sexuality

- Social Media

- Cultural Appropriation

- Sociological Imagination

- Media Analysis

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Majority of Latinos Say Skin Color Impacts Opportunity in America and Shapes Daily Life

- 4. Measuring the racial identity of Latinos

Table of Contents

- 1. Half of U.S Latinos experienced some form of discrimination during the first year of the pandemic

- 2. For many Latinos, skin color shapes their daily life and affects opportunity in America

- 3. Latinos divided on whether race gets too much or too little attention in the U.S. today

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

- Appendix: Additional tables

How we measured racial identity among Hispanics

The survey used the following four questions to assess the racial identity of Latinos:

What is your race or origin?

- Black or African American

- Asian or Asian American

- Two or more races

- Some other race or origin

How would most people describe you, if, for example, they walked past you on the street? Would they say you are …

- Hispanic or Latino

- Native American or Indigenous (the native peoples of the Americas such as Mayan, Quechua or Taino)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

- Mixed race or multiracial

In your own words, if you could describe your race or origin in any way you wanted, how would you describe yourself?

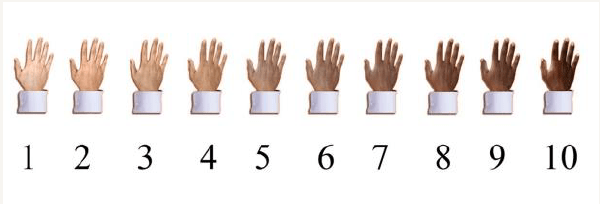

Which of these most closely matches your own skin color, even if none of them is exactly right? (If this question makes you uncomfortable, you may skip it.)

The most widely employed method to measure racial and ethnic identity is from the U.S. Census Bureau. It is a two-part question, first asking about Hispanic identity and then asking about racial identity and is the standard method used to measure racial and ethnic identity in decennial censuses and in surveys conducted by the bureau. It is also the standard often used by polling organizations, marketers, local governments and many others.

Alternative measures can capture other dimensions of racial and ethnic identity not necessarily captured by the Census Bureau’s format. For example, one’s skin color can shape opportunities and can be at the heart of discrimination experiences no matter what race one identifies with. In addition, how others see you, such as when passing each other on the street, can shape one’s life experiences. And sometimes directly asking one to describe their racial identity can reveal a personal view of identity unencumbered by the framing of survey questions.

Pew Research Center’s 2021 National Survey of Latinos explored four approaches to measuring racial identity – the Census Bureau’s two-question method; an assessment of how respondents believe others see them when passing them on the street (street race); an open-ended question asking respondents to describe their race and origin in their own words; and self-assessed skin color. Responses across all these measures do not necessarily align – a respondent may indicate their race is White in the Census Bureau’s method but also indicate their street race is Latino (and not White). These differences in responses reflect the nuances of racial identity, contextual factors and the experiences associated with them. This chapter explores these four alternative measures and the responses of Latino adults.

The Census Bureau’s standard method for measuring race and ethnicity

In current Census Bureau data collections like the 2020 decennial census and surveys like the American Community Survey, racial and ethnic identity is asked about in a two-part question . First, respondents are asked if they are Hispanic or Latino and then in a second question are asked their race. Currently, the Hispanic category is described in census forms and surveys as an ethnic origin and not a race with respondents given explicit instructions indicating so.

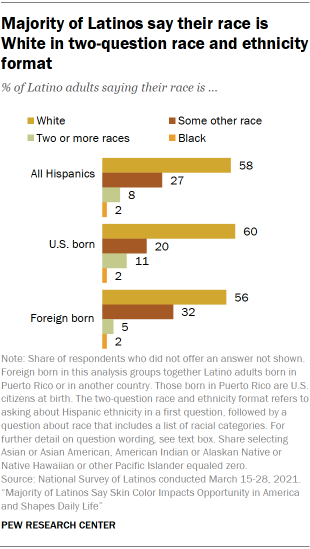

The Pew Research Center survey replicated the Census Bureau’s format, asking about race separately from Hispanic ethnicity. Asked about their race in this way, more than half of Hispanics in the survey identified their race as White (58%), with the next largest share selecting the “some other race” category (27%), 8% selecting two or more races, and 2% selecting Black or African American. Foreign-born Hispanics were more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to select the “some other race” category, while U.S.-born Hispanics were more likely than foreign-born Hispanics to select multiple races. For both groups, though, more than half say their race is White.

These findings echo those of earlier Pew Research Center surveys of Hispanic adults, as well as Census Bureau findings from the 2010 decennial census and other surveys. Yet, the findings from this survey by the Center, conducted in March 2021, differ from those revealed by the Census Bureau from the 2020 decennial census . The wording of the 2020 Census race question differed markedly from the Center’s question and from previous decennial censuses surveys, which could account for why results varied greatly. In the 2020 census, for the first time respondents were prompted to write in origins or ethnicities for all racial groups; this was not offered to the Center’s survey respondents. According to the bureau , about four-in-ten Hispanics (42%) marked their race as “some other race” in the 2020 census without marking any other response, the single largest set of responses among the nation’s 62.1 million Hispanics—an analysis of the 2010 decennial census results showed that most responses coded as “some other race” were write-ins of Hispanic ancestries or ethnicities. This was followed by one-third (33%) who selected two or more racial groups, and 20% that selected White as their race. A separate Pew Research Center survey from 2020 found Hispanic adults were more likely than White or Black adults to say the 2020 decennial census two-part race and ethnicity questions do not reflect their identity well: 23% of Hispanic adults say census race and ethnicity questions reflect how they see their race and origin either “not too well” (17%) or “not at all well” (5%). This compares with 15% of White adults and 16% of Black adults who said the same.

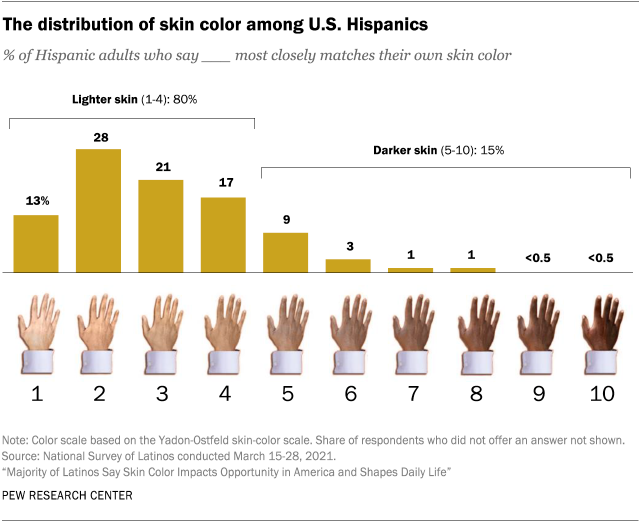

Latinos’ skin color reflects the diversity within the group

For Latinos and non-Latinos alike, skin color is an important dimension of identity that can affect their daily lives. To measure this dimension of race, the survey asked Latino respondents to identify the skin color that best resembled their own using a version of the Yadon-Ostfeld scale. Respondents were shown 10 skin colors that ranged from fair to dark (see graphic below for images used). Eight-in-ten Latinos selected one of the four lightest skin colors, with the second-lightest ranking most common (28%), followed by the third (21%) and fourth lightest colors (17%). By contrast, only 3% of Latino respondents in total selected one of the four darkest skin colors.

For purposes of the analysis in this report, Hispanics are grouped into two categories. The “lighter skin” color group consisted of those who chose the four lightest skin colors (80%), while the “darker skin” color group included those who chose the six darker skin colors (15%). (Another 5% of respondents did not indicate their skin color.) While there were enough Hispanics who chose each of the lightest four skin colors to analyze separately, there were no significant differences in the opinions or experiences of discrimination among them due to their skin color. (The number of Hispanics who chose the five darkest skin tones was too small to analyze each separately.)

Among Latinos, those who rated their skin as lighter were more likely to be older than 50 (35%) than those who rated their skin as darker (23%). Latinos with lighter skin were also more likely to be women (52%) than Latinos with darker skin (42%).

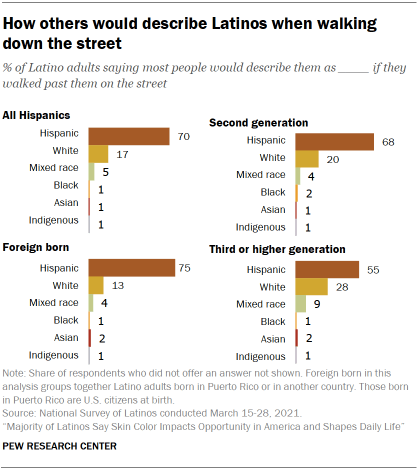

Most Latinos say others would describe them as Latino when walking past them on the street

Similar to skin color, the way others perceive Latinos when interacting with them is another manner in how racial identity can be shaped. In the survey, respondents were asked how most people would describe them if they walked past them on the street.

Seven-in-ten Hispanic adults said that most people would describe them as Hispanic when walking past them on the street, with the foreign born the most likely to say this (75%) compared with those of the second generation (68%) or third or higher generation (55%).

Fewer than two-in-ten Latinos (17%) say others would view them as White when walking past them, with those born in the U.S. being more likely to say this (28% of at least third-generation Latinos and 20% of second-generation Latinos) than Latino immigrants (13%).

A smaller share (12%) say others view them as belonging to another racial group such as Asian, Black or Indigenous.

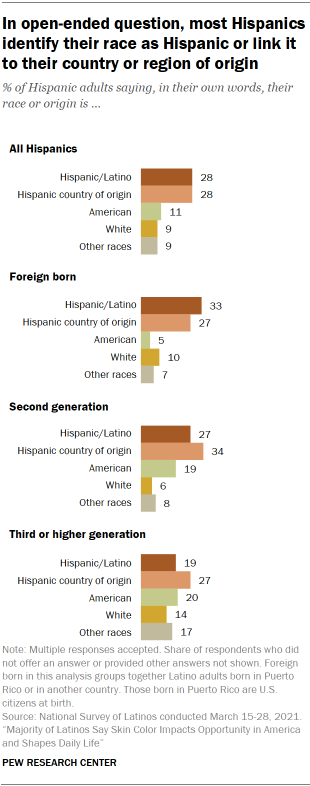

Asked to describe their race or origin, most Latinos say they are Hispanic or Latino or give their country of origin

As a fourth measure of racial identity, the survey asked Latinos how they would describe their race or origin in their own words. The most common responses for Latinos regarding their race in this open-end format were the pan-ethnic terms Hispanic, Latino or Latinx (28%) or responses that linked their racial origin to the country or region of their ancestors (28%). A smaller share also chose to identify their race or origin as American, either as a single answer or in combination with another response (11%), 9% identified their race as White, and 9% mentioned another racial group such as Asian, Black or Indigenous.

There were some differences in the way Hispanics identified their race depending on their immigrant roots. Fully one-third of the foreign born (33%) used the pan-ethnic terms Hispanic, Latino or Latinx to identify their race, while 23% of the U.S. born did so. Among the U.S. born, those with at least one immigrant parent – second generation Hispanics – were also more likely than those without any immigrant parents – third or higher generation – to use the pan-ethnic terms to describe their race (27% vs. 19% respectively).

Conversely, those born in the U.S., regardless of the place of birth of their parents, were more likely to describe their race or origin as American or having been born in the U.S. (19% of the U.S. born vs. 5% of the foreign born).

Those in the third or higher generation were more likely than those from the second generation to describe their race as White (14% vs. 6%). In addition, third or higher generation Hispanics were more likely than Hispanic immigrants or those with at least one immigrant parent to mention another racial group such as Black or Asian in their response (17% compared with 7% of foreign born and 8% of second generation).

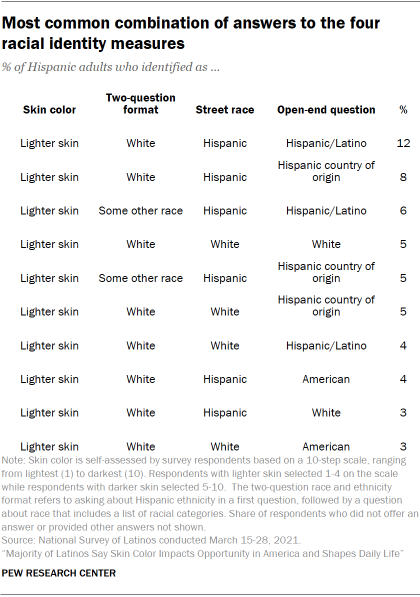

How the four racial identity measures correlate with each other

There is some overlap in the responses to the four racial identity questions, particularly when looking at just two of the four measures. For example, nearly all respondents who say most people see them as White when passing them on the street (95%) chose one of the four lightest skin colors (1-4). By comparison, 79% of those who say they would be viewed as Latino by passersby selected one of the four lightest skin colors and 69% who say they would be perceived as belonging to another racial group did the same.

Similarly, 94% of those who said their race was White in the open-ended question chose one of the four lightest skin colors. About eight-in-ten (83%) of those who say they are Hispanic in the open-ended question or included a Hispanic country of origin or region (80%) also chose one of the four lightest skin colors. Meanwhile, 74% Hispanics who mentioned another racial group like Black or Asian selected one of the lighter skin colors.