A changing nation: the effects of globalisation on China

Finding opportunity in change.

China is rapidly becoming the new champion of economic cooperation, trade and globalisation. As others retreat from the forefront, Chinese businesses are looking to expand and grow into all corners of the world.

China and globalisation are no strangers. The process has been happening for a long time, and it is essential that any business looking to break into China combines a global strategy combined with a market specific approach.

As the global economy shifts its focus towards China, new opportunities for businesses to enter the Chinese market are emerging. In other words, the impact of globalisation on China’s economic growth is already being felt. China is rapidly becoming the new champion of economic cooperation, trade and globalisation. As others retreat from the forefront, Chinese businesses are looking to expand and grow into all corners of the world.

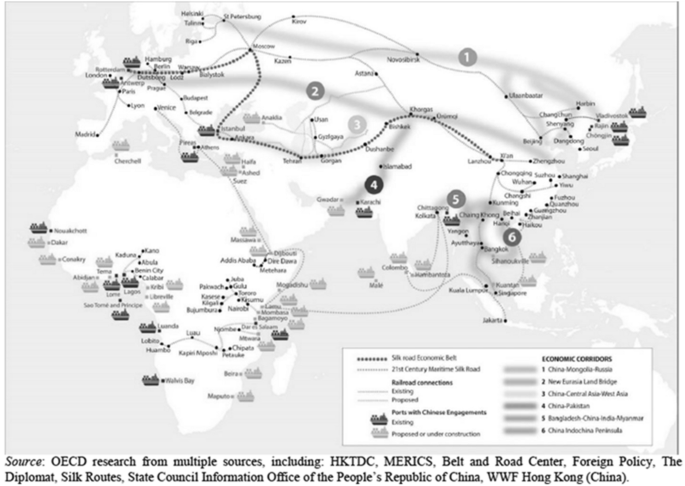

A Chinese globalisation case study worth following is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), devised by China’s premier Xi Jinping, which focuses on connecting the vast array of countries that sit within the region. It’s one of the reasons for the growth of globalisation in China, and this Chinese led trade network enables large, medium and small enterprises to realise their potential and trade more simply and expansively around Asia.

While businesses are eager to take to the world stage and reap the benefits of globalisation in China, they remain cautious of outsiders. Ensuring you are culturally sensitive will offset some of this reticence and businesses of any size must appreciate that Chinese business culture does not follow western norms.

Businesses that wish to be successful in China need to not only consider the business culture , but also how regulations and political policies are shaped by that culture.

The shift towards protectionist attitudes that we have seen in some key markets are examples of western politics negatively affecting the global ambitions of Chinese businesses. It is actually in spite of this that the outlook is still positive and demonstrates the resilience of Chinese businesses. (Another good globalisation case study for China is Huawei, which shows this resilience and continues to expand its global market share).

Businesses that wish to be successful in China need to not only consider the business culture, but also how regulations and political policies are shaped by that culture. Building trust is key, as is working with local partners who understand the local landscape. It is imperative in Chinese business to show you are trying to work towards a mutually beneficial outcome.

Many influencers are starting to question whether if in China globalisation is causing business culture to separate from tradition – and if so, the impact this would have on established business practice. When considering the Chinese way of thinking, illustrated by the value of “people-oriented” methods, some may argue that business is detaching itself from people. However, the current issue businesses must confront, in the face of deglobalisation, is how to maintain a balance when dealing with global development on one hand, and a global populous that is becoming increasingly sceptical of international business. The prosperity of a country and the businesses within it can, in itself, be seen as people-oriented, but only if Chinese society believes the spoils of globalisation are shared.

Protectionism may bring short term benefits but the global economy would suffer if the flow of capital and business were less dynamic. One should not react by shutting out outsiders. As the ideas of reciprocity and benevolence indicate, cooperation is a better way to succeed. As businesses large and small continue to look abroad for growth, it has become more important than ever to realise the power of diversity.

So, with all these considerations in mind, how has globalisation affected China? The answer might be that while globalisation has boosted expansion and interaction within political, economic and cultural terms, it has also brought friction and conflict – which foreign businesses can help to assuage through understanding working practices in China.

Crucially, businesses must keep in mind that China is seeing a divergence between its generations. The young are more aware of the outside world and often more tolerant of different people and values. On the other hand, the older generations in China do not have much experience of the rest of the world, but they appreciate people who try to become more informed and understand Chinese culture. At the same time, as the younger Chinese look outwards, so does the Government, and it is this shift in perceptions that presents the greatest opportunity for businesses to work in partnership with the Chinese. To become a global business player, one needs to be a global thinker first.

With this in mind, the Chinese way of conducting business is likely to become even more relevant, particularly as the previous instigators of global cooperation opt to retreat from the forefront of an increasingly connected world. Thus, while it is still not clear what direction China and globalisation are taking in respect of each other, and it remains unclear what shape plans such as the BRI will take, we are in a position where understanding the Chinese way of doing business is crucial not only for being successful in China, but also the wider world.

Finding Opportunity in Change homepage

Related insights

RSM Global Blog Finding opportunity in change

Manufacturing Finding opportunity in change

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Finding opportunity in change Environmental, Social and Governance

Financial services Finding opportunity in change Environmental, Social and Governance

Automotive ESG and sustainability services Finding opportunity in change

The Impact Of Globalization In China Essay Example

| 📌Category: | , , |

| 📌Words: | 729 |

| 📌Pages: | 3 |

| 📌Published: | 03 June 2021 |

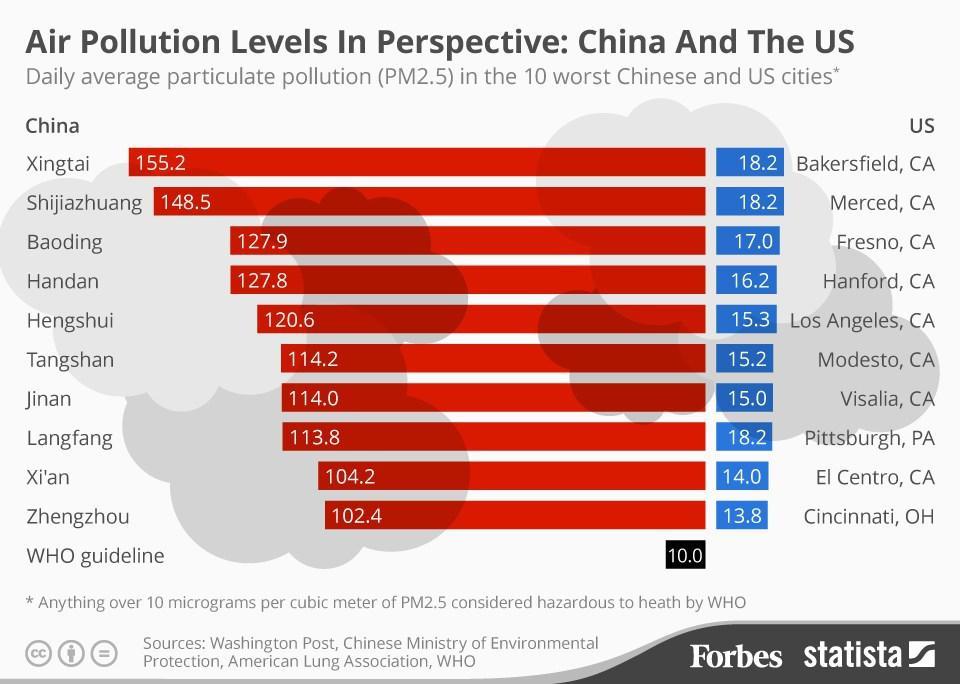

Kofi Annan once said, “It has been said that arguing against globalization is like arguing against the laws of gravity.” China’s air pollution has been negatively affected by globalization. Globalization is a process where many economies around the world can come together and become more connected. In a globalized economy, one country typically buys certain goods from other countries. Unfortunately, this has positive consequences along with negative consequences. China is an example of a country that has been negatively affected by globalization.

In addition, China has a variety of widespread environmental issues; One of these issues is coal. China buys its coal mainly from Indonesia, Australia, and Russia. Consequently, coal has caused lethal air pollution in China. For instance, China consumes 2.5 billion tons of coal a year. One major city named Chongqing, in China has been affected by the coal in China. Chongqing is a major consumer of coal. Accordingly, globalization has caused these people in ChongQuing to breathe polluted air. Analytics from this city have said that this contaminated air can affect the growth of the next generation in that area. In total, Chongqing has 9 coal-based plants. These plants are some of China’s largest coal plants. Coal is mostly carbon. When this is burned, it reacts with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide. Then it is released into the air; the carbon dioxide heats the air in an unhealthy way. Globalization has allowed China to produce and consume all of this coal. As a result, 1.6 million people die per year in China. A study concluded that industrial coal-burning leads to 86,500 deaths at coal power plants in China. Data has said that coal is the leading cause of air pollution in China. China is also the leading consumer of coal in the world. Their consumption has been doubled since 1998. Coal isn’t the only product of globalization that affects China’s air pollution. However, Coal is the product that affects it the most in their largest cities.

Furthermore, Oil is another product that China gets due to globalization; Oil has affected their air pollution in a negative way. China buys its oil from Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iraq, Angola, and Brazil. With this in mind, China consumes 12,791,553 barrels of oil as in 2016. They also produce 5.45 million BPD. Daqing has the largest oil field in China. In fact, they have an estimated 16,000 barrels of oil there. Daqing’s air mass index hit 999 on January 6th, 2020. All things considered, this is a very unhealthy Air mass index. On Average, oil production emits 10.3 grams of pollution. Oil has caused the city of Danqing to live a very unsafe lifestyle. In 2003, China was the 6th biggest producer of oil in the world and the 2nd largest consumer of oil in the world. Due to globalization, China is able to create this large amount of oil, and they are able to consume this large amount of oil. Air pollution can be made during any of the stages of making oil. Since China makes this much imagine how much pollution they create in a year.

Moreover, Natural gas is another product from Globalization that has affected China. On this subject, they normally buy their natural gas from Russia. Beijing is the second-largest natural gas consumer in the world. In fact, in October 2020 Bejing consumed 173.54 billion cubic meters of natural gas. On Sunday, April 11th Bejing’s air quality wasn’t so good. Subsequently, natural gas mostly caused this. China is ranked number eight in the world as the leading natural gas producer. They only import 31% of their typical natural gas consumption. Major Cities in China such as Bejing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong have been affected the most by air pollution. In most power plants natural gas produces 50-60% less carbon dioxide than regular oil or coal plants. However, the combustion of natural gas releases methane and reduces air quality. Trade from globalization on natural gas from Russia has led China to this state. Air pollution has caused an estimated 49,000 deaths in Beijing and Shangai alone since January 1. 2020. If China doesn’t take action on their trading from Globalization, it could ruin their air quality permanently.

In conclusion, Air pollution has left a negative impact on China due to globalization. Some imports from Globalization to China such as coal, oil, and natural gas have had an effect on China. Air pollution causes diseases such as cancer. Overall about 30.8 million people in China have died from air pollution. These big cities such as Chongquing, Daqing, and Bejing have been a major target from Air pollution. Globalization can strengthen a country, but it can also destroy one. “Globalization is incredibly efficient but also so far incredibly unjust”.

Related Samples

- American Revolution Essay Example

- An Analysis of The Communist Manifesto

- Essay Sample about Europe and World War I

- Essay Sample: Blowback as a Part of US Foreign Policy

- Essay Sample on Edo Castle 17th - 21th Century

- American Politics and the Superiority of Specific Political Orientations

- Socialism vs. Capitalism Essay Sample

- Why Canadians Need A National Pharmacare Program

- Franklin D. Roosevelt and World War II Essay Example

- Essay Sample on Scottish Independence After Brexit

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

Unsupported Browser Detected. It seems the web browser you're using doesn't support some of the features of this site. For the best experience, we recommend using a modern browser that supports the features of this website. We recommend Google Chrome , Mozilla Firefox , or Microsoft Edge

- Arts and Culture

- Asia Society Museum

- Our Galleries

- Chinese Language Learning

- Asia Society Policy Institute

- Center on U.S.–China Relations

- Asia 21 Next Generation Fellows

- Asia Society Magazine

- Asian Diaspora Project

- Video Gallery

- Northern California

- Philippines

- Southern California

- Switzerland

- Washington, D.C.

- About Asia Society

- Interns and Volunteers

China Is Globalization's Greatest Success Story. Can the Good Times Last?

This photo taken on April 17, 2018 shows a worker checking steel pipes at a factory in Zouping in China's eastern Shandong province. (AFP/Getty Images)

On May 10, Ian Bremmer will discuss his new book with Asia Society Policy Institute President Kevin Rudd at Asia Society in New York. The event will be available via live webcast at 8:30 a.m. New York time. Learn more

During Donald Trump 's successful campaign for the U.S. presidency in 2016, he regularly disparaged "globalists" who, he argued, had robbed the United States of its national wealth and sovereignty. Though Trump's victory is often seen as a sui generis event, one only possible in a celebrity-saturated culture like America's, his attacks on globalization are hardly unique worldwide: Britain's exit from the European Union and rising authoritarianism in once-stalwart democracies like Turkey, the Philippines, and Hungary have each derived, to a certain degree, from anger about globalization and economic elitism.

One country which has so far resisted this trend is China, which should probably come as little surprise — arguably no major economy in the world has benefited more from globalization. But Ian Bremmer , one of America's most trenchant geopolitical analysts, says that the rest of the world cannot afford to rely on Beijing to sustain the global economy forever. In this excerpt from his new book Us Vs. Them: The Failures of Globalism , Bremmer explains why China's remarkable success story may soon encounter serious roadblocks.

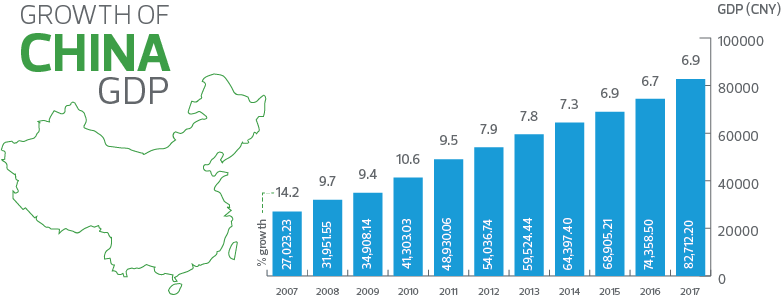

Here is globalization’s greatest success story.

China’s rise can be measured in many ways, but the most impressive number is the 700 million people that state-led reform has lifted from poverty over the past four decades. In 1986, China’s per capita GDP was $282. In 2016, it climbed above $8,100. The country’s middle class represented 4 percent of the population in 2002 and 31 percent in 2013. For the future, the Communist Party leadership says it can educate enough people, create enough jobs, stoke enough growth, and provide enough health care to boost 50 million more from the lowest income brackets by 2020. Despite predictions from many people over many years that a crash of China’s economy is long overdue, the world’s biggest emerging market and its aspirations remain aloft.

Yet, for a variety of reasons — all of them inevitable — the country’s growth rates continue to slow, and its gains are under pressure. The 2008–2010 financial crisis in the West made clear to China’s leaders that they must move more urgently to relieve the country’s dependence for growth on the willingness of U.S. and European consumers to buy China’s cheaply made manufactured goods. To lock in long-term economic stability, China needs to build and bolster its own middle class, one that can afford to buy much more of those factory-made consumer products. Success has pushed Chinese wages higher. But as pay rises, China loses the advantage that brought so many foreign companies to the country in the first place. Even Chinese companies have begun to move production to poorer countries, particularly in Southeast Asia, where labor is cheaper. Higher wages can’t help you if you don’t have a job.

Further, the problem of inequality has been growing for years. Even as hundreds of millions have climbed the ladder, the wealth gap has grown larger between the low-income population still trapped in the countryside, the new middle class, and the now superrich. The Gini coefficient has risen dramatically (from 0.27 in 1984 to 0.42 in 2010), but even that large jump probably doesn’t capture the true scale of the problem. Statistical fraud at different levels of government undermines confidence in numbers we know are politically sensitive. We can be sure that the coastal regions of China are far richer than the interior and that, even by the standards of other developing countries, the gap between urban and rural wealth is large and growing.

Then there is the poisoned air and water, the bitter product of decades of surging economic growth. The statistics have become sadly familiar. China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection has reported that two-thirds of China’s groundwater and one-third of its surface water are unfit for human contact of any kind. Toxins and garbage ensure that almost half the country’s rivers fall into this category. Estimates are that air pollution kills more than one million Chinese people per year.

In addition, the country’s social safety net remains a massive work in progress as China’s population gets old faster than anywhere else in the world, leaving fewer and fewer workers to produce the wealth needed to pay for care for the elderly. In 1980, the median age, the point that divides a population into two numerically equal halves, was 22.1 years in China and 30.1 years in the United States. A UN study has estimated that, by 2050, the median age will be 40.6 in the United States and 46.3 in China. In the 1990s, China introduced a program called the Minimum Livelihood Guarantee Scheme, or Dibao, to provide small amounts of money to the poorest people. More recent projects designed to boost incomes for people living in the countryside have reached hundreds of millions of people but with payouts too small to meet the most basic needs, particularly of the elderly. Automation will help China avoid a sharp fall in productivity as its population ages, but it will be years before we know what that means for China’s social safety net and the government’s ability to finance it.

China has important advantages, particularly over other developing countries. First, its system of higher education is improving quickly and in ways that may help make the transition to a world of sharply expanded automation and artificial intelligence. According to annual rankings published by U.S. News & World Report in 2017, China is now home to four of the world’s top 10 engineering schools. (The United States also has four.) Each year, China now graduates four times as many students as the United States (1.3 million vs. 300,000) in the subjects of math, science, engineering, and technology.

In addition, while India is uniquely diverse, the dominance of the majority Han Chinese population, which represents more than 90 percent of China’s total population, creates social homogeneity in the country’s most prosperous and influential cities and provinces. The lack of any viable leadership alternative to the Chinese Communist Party reinforces stability. It’s also fortunate that China’s senior leaders understand many of the country’s challenges very well — and that the party’s long-term survival depends on meeting them. No government has been more effective since 1980 in advancing reforms that expand prosperity. A serious effort is being made to tackle corruption, pollution, lack of access to education and decent medical care, wealth inequality, product (particularly food) safety, and the need for a stronger safety net.

Though the Chinese leadership has said plenty about the positive impact that the large-scale introduction into the workplace of automation and artificial intelligence will have on China’s economy, it has said and done little to address the enormous economic, social, and (perhaps) political turmoil it’s bound to create. Remember that the World Bank has estimated that automation and innovations in machine learning threaten 77 percent of all existing jobs in China. That’s a major disruption in the lives of hundreds of millions of people, particularly in the country’s most crowded cities. As Chris Bryant and Elaine He wrote in January 2017, “It took 50 years for the world to install the first million industrial robots. The next million will take only eight, according to Macquarie. Importantly, much of the recent growth happened outside the U.S., in particular in China, which has an aging population and where wages have risen.” China, they note, is installing a much bigger absolute number of industrial robots than any other country on earth.

It’s all the more remarkable, then, that China’s political leaders say they’re determined to embrace the tech revolution with both arms and as quickly as possible, with little public discussion of, or preparation for, massive job losses that can’t be avoided. Instead, the government has focused almost exclusively on building China’s competitive edge in robot manufacturing. In China’s carefully controlled political system, there are no civil society organizations warning of this oncoming wave.

Xi Jinping’s government will push hard to improve education for high-tech jobs, since China faces major shortages of high-skilled tech workers in semiconductors, robotics, and artificial intelligence. But there are also shortages of qualified teachers and open university slots, leaving huge numbers of workers with a fast-narrowing set of work options.

Failure to protect rising middle classes from crime, corruption, and contaminated food, air, and water, along with failure to care for the unemployed, sick, and elderly, creates a profoundly dangerous situation for China. But it is the extreme disruption of the workforce and massive loss of jobs that could push tens or hundreds of millions back toward poverty that might prove an entirely new kind of threat to the country’s stability and its future.

China has some obvious advantages. It’s the one government that, at least for now, can afford to spend huge amounts of money to create unnecessary jobs to avoid political unrest. China’s historic successes suggest this might be the one country that can find a way to adjust, and the aging of its population could be a plus as the country needs fewer jobs in coming years than rival India. We all better hope so, because, month by month, the entire global economy is becoming more dependent on China’s continued stability and growth.

Excerpted from Us vs. Them: The Failure of Globalism by Ian Bremmer, in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Ian Bremmer, 2018.

China’s Rise, World Order, and the Implications for International Business

- Research Article

- Published: 03 March 2021

- Volume 61 , pages 1–26, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Robert Grosse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2239-5555 1 ,

- Jonas Gamso 1 &

- Roy C. Nelson 1

48k Accesses

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

It is increasingly clear that China’s economic and political power rivals that of the US. This is potentially a serious problem for multinational companies, since China’s rise could lead to more US–China trade conflict and disruption of supply chains, threatening new and ongoing foreign direct investment, and drawing other countries into the jostling for power. However, we argue that globalization is not necessarily endangered by China’s emergence as a comparable power to the US. The US and China both have vested interests in maintaining the open economic order, and these two countries are each providing the global public goods that incentivize economic openness among other countries of the world. In this paper, we develop a theory corresponding to this argument and provide evidence that globalization has not declined even as the global distribution of power has shifted. While global integration is likely to persist, disruptive skirmishes between the US and China will occur with some regularity. Therefore, we suggest that international company strategies today should focus more on risk management related to policy shifts stemming from China’s rise and less on achieving least-cost global supply chains. We present a risk management framework for this purpose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Moving up the Global Value Chain: The Case of Chinese IT Service Firms

Living with Complexities and Uncertainties

Introduction

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Scholars and commentators increasingly see China as a global superpower (Anngang 2012; Cao and Paltiel 2015 ; Fish 2017 ) and China’s rise is widely understood to be ushering in a new global power distribution (Maher 2016 ; Shifrinson 2018 ; Tunsjø 2018 ; Zeng and Breslin 2016 ; Xuetong 2019 ). Footnote 1 China has the world’s second largest economy, trailing only the United States (International Monetary Fund 2020 ). It was the world’s leading exporter and second largest importer in 2018, the last year for which data were available (World Bank 2020a ), and its foreign aid provision and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) have also grown over the last decade (Dreher et al. 2018 ; Kolstad and Wiig 2012 ; Wang and Zhao 2017 ). Accompanying China’s economic rise has been an escalating assertiveness geopolitically (Liao 2018 ) that reflects China’s growing hard power (Robertson and Sin 2017 ; Tayloe 2017 ) and soft power capabilities (Shambaugh 2015 ).

In short, there is now a strong case to be made that the world has entered an era in which the US and China are approximately equally powerful. This is a marked contrast from the post-World War II era, during which the US dominated in the realms of economy, security, and technology (Ikenberry 2005 ). China’s emergence as a comparable power to the US raises concerns, since “realist” international relations theory suggests that such a trend will lead to a collapse of globalization as countries reject economic openness in favor of economic nationalism (Mearsheimer 2019 ). In contrast, we argue that China’s rise does not have to result in reduced international economic integration, and so we present a first research proposition to explore this issue:

Proposition 1:

China’s rise will not promote de-globalization, though it will lead to jostling for power between the US and China .

There has been a rise of political nationalism in the latter half of the 2010s (Snyder 2019 ). This has been accompanied by some degree of economic protectionism (Fajgelbaum et al. 2020 ), raising alarms among business leaders (Edgecliffe-Johnson and Waldmeir 2018 ). Much has also been made of the ongoing US–China trade war and hostility by US leadership toward the international institutions tasked with supporting economic globalization (Brown and Irwin 2019 ). However, these concerns may be overblown, as world tariff levels remain low by historical standards (Russ 2019 ), international trade and investment remain at or near their peaks, and the incoming Biden Administration may be more supportive economic globalization.

In fact, there are significant reasons to suspect that China’s rise will not usher in an era of protectionism and deglobalization. In the analysis that follows, we theorize that a world order in which China and the United States constitute a “G-2” can be conducive to the continuation of global economic integration. Maintaining a relatively open world economy is in the national interests of both of these countries. For that reason, both have committed themselves to international and regional economic agreements to help sustain that outcome. As long as both the US and China see the maintenance of the globalized world as being in their interest, each will adhere to the norms supporting globalization and help those norms to endure. In this sense, as we will explain further below, they will act as “ dual hegemons.” As we demonstrate in our analysis, the evidence supports this expectation, such that economic globalization has persisted even as China has become a superpower on (or near) par with the United States.

Even so, China’s rise and the changing global power dynamics that are accompanying it carry significant risks for international business. The new order brings changes to the nature of globalization: Skirmishes between China and the US may disrupt supply chains, threaten new and existing FDI, and include the establishment of new trade barriers. While we do not expect these changes and conflicts to cause a decline in net global integration, we argue that multinational firms need to evaluate and manage the risks that will occur as a result of changes in the nature of globalization.

Just dealing with China has been a risk for foreign businesses, because of the Chinese government’s protectionist tendencies. For example, China requires foreign auto manufacturers to have local partners with at least 50% ownership, as with Volkswagen and GM in their joint ventures with Shanghai Automotive. The government has also shown its disapproval of moving information across borders, as in the case of Amazon Web Services being essentially shut out of the market, and Google and Facebook being severely restricted and banned, respectively. And these policies predate the China–US trade war, which further threatens US-based businesses in China as well as Chinese business going overseas, particularly to the United States. The trade war has resulted in tariffs being imposed on a wide range of products, from steel and aluminum imports into the US to agricultural products exported from the US to China.

While the recent US–China trade tensions are likely to die down, the emerging world order is sure to create more frequent risks for companies engaging in international business, making risk management a priority going forward. A risk management strategy can be sketched broadly by looking at the methods available to MNEs for this purpose. Companies can explore the establishment of production and distribution facilities located outside of the two main protagonist countries. For example, electronics could be assembled in Vietnam or in Thailand rather than only in China; and Mexico or Colombia could be used for additional assembly of electronics, autos, and textiles. Companies also can diversify their business activities such as sales and input purchases into additional countries, again to reduce the dependence on the two main protagonists. A wide range of steps could be taken to mitigate the risks, from the use of insurance contracts for insurable risks to partnering with local companies in the US and China to reduce the liability of foreignness. So, we present a second research proposition:

Proposition 2:

MNEs need to develop risk management strategies to deal with the US-China competition that will occasionally produce trade barriers and other policy interventions .

The remainder of our analysis proceeds as follows. In Sect. 2 , we discuss China’s rise and demonstrate that US and China are approximately equally powerful hegemons. Next, in Sect. 3 , we introduce our theory, which posits that global economic integration will persist through an era in which China and the United States are each global superpowers, drawing on theories of international relations. In Sect. 4 , we present the evidence so far, which suggests that little shift in global economic engagement can be attributed to China’s rise. In Sect. 5 , we discuss in more detail the implications for multinational enterprise (MNE) strategies and we lay out a framework for managing this geopolitical risk. Finally, we note challenges to long-term stability in a world with two global superpowers.

2 Changing Power Dynamics in the Twenty-First Century

China’s rise is, perhaps, the single most important economic and political phenomenon in the twenty-first century. It has implications for global security (Toje 2018 ), for international development (Gallagher and Porzecanski 2010 ; Lin 2018 ), for global governance (Beeson and Li 2016 ; Economy 2018 ), and for human rights (Gamso 2019 ), among other things. While China’s status in international trade is especially noteworthy, it is also growing by other measures of international power. China’s growing clout in international production and financial markets are evident in terms of its global leadership in overall manufacturing, in the offshore assembly of electronics and textiles, and its growing financial leadership through owning the world’s four largest banks. China is also growing in global leadership through development of new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and its Belt and Road initiative (Soong 2018 ). The Belt and Road scope is pictured in Fig. 1 .

One (land) belt and one (ocean) road initiative. Source: OECD 2018 , p. 11

In terms of total market size, China is nearly as large as the US and much larger than any other country, whether measured in current dollars or in purchasing power parity dollars. In 2019, US GDP was $US 21.4 trillion, while Chinese GDP was $US 14.1 trillion in nominal terms and in purchasing power parity terms, Chinese GDP was $US 27 billion. In terms of company competitiveness, China had 119 Fortune Global 500 companies and the US had 121 in 2019. In terms of innovation, measured as R&D spending in the country, the US led the world by far with spending of $US 581 billion in 2018, while China was second with $US 293 billion, and both countries were far ahead of the third leader, which was Japan at $US 193 billion. Footnote 2 Table 1 presents a comparison of China and the US in terms of some key economic/business indicators.

China has also modernized the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in order to counter potential invasion (Montgomery 2014 ), while asserting its dominance over the South China Sea (Morton 2016 ; Thayer 2011 ; Turcsányi 2018 ). Likewise, China has become a major producer of science and technology, owing to public investment in the sciences such as the 2006 Medium to Long Term Program of Science and Technology (MLP) and Made in China 2025 initiative (Cao et al. 2006 ; McBride and Chatzky 2019 ; Xie et al. 2014 ). Taken together, this expansion of Chinese power suggests the emergence of a new world order, in which there is a roughly equal distribution of power between the United States and China.

While the US and China are rivals on some political issues (Scobell 2018 ), they do not necessarily have different visions for the global economy, as both operate open economic policy regimes, even with some significant differences in structure (for example, China has many more state-owned companies than the handful in the US). Moreover, there is an economic symbiosis, in which each country offers features that are helpful to the other. China offers low-cost manufacturing capabilities that complement US design of manufactured goods and a market for selling them. The US offers manufactured goods that are not made in China to the Chinese market, plus ones assembled in China but developed in the US, as well as primary products such as agricultural and mining goods, and also a wide range of services. And of course, the US offers China the world’s largest market for selling Chinese goods and services.

3 Global Stability in a Two-Hegemon World

The modern era of globalization coincided with the era of US hegemony, and US support for the global economic order was crucial for its success and its persistence. Despite occasional protectionist policies, the US offered global public goods that compelled other countries to trade and invest with the US and with one another (Kindleberger 1973 ). These public goods included the provision of global security, which reduced transaction costs for traders around the world, a large import market to absorb goods produced abroad, and lending facilities that helped to promote development and financial stability in developing countries, so long as those countries remained open to international trade and investment.

There were challengers to US dominance in the years after WWII, with the Soviet Union being especially noteworthy, but they were not ultimately able to match US power or to credibly challenge the open economic order that US leadership established after WWII. While the Soviet Union never presented a viable economic threat to US dominance of the capitalist global economy, its nuclear capabilities allowed the Soviet Union to present a military threat to the US that led to a bipolar balance of power in the years after WWII. The result was the Cold War, with tensions, hostilities, and sometimes outright minor skirmishes. But the overwhelming threat of “Mutually Assured Destruction” (MAD) if either side were to strike first deterred each country from engaging in more aggressive behavior, which prevented more major conflict from occurring (Brennan 1971 ; Schelling 1966 ).

As we have shown, China now, even more than the Soviet Union, is a viable challenger to US dominance, not just militarily, but economically as well. We argue, however, that just as the bipolar balance of power between the US and the Soviet Union led to a relatively stable outcome, albeit with significant tension and minor skirmishes, a similar outcome will prevail now between the US and China. These days it is not the threat of mutually assured destruction that prevents more aggressive behavior on both sides, but, as others have noted, the threat of “mutually assured recession” if either side were to engage in actions that could result in an outright trade war, or even worse, the destruction of the liberal economic order. For this reason, we expect both the US and China to provide support for globalization, even as they vie for global power.

3.1 A Theory of Dual Hegemonic Stability

According to the international relations theory of hegemonic stability in the tradition of Kindleberger ( 1973 ), the hegemon is understood to provide public goods that, in turn, encourage and facilitate economic openness among weaker countries. These public goods include an import market for producers around the world, lending facilities for countries in crisis, and international security, which reduces transaction costs for traders and investors. Kindleberger argued that public goods provision will become difficult where two or more states are bargaining with comparable leverage, due to collective action problems (Olson 1965 ). Thus, by his estimation, economic globalization will collapse as unipolarity wanes, much as it did in the early twentieth century.

However, scholars have noted that multiple states can provide public goods, should they see the benefits of doing so (Lake 1993 ; Snidal 1985 ). Within this context, it is perfectly plausible that China and the US can act as ‘dual hegemons’. We argue that to promote their own national interests, each will provide public goods that facilitate free trade, such as support for the multilateral trade regime, lending to countries in crisis, and providing large import markets. That said, in order for two states to provide public goods that advance the same outcome—that being an open global economic order—it is necessary that they both have a common perspective on how the global order should look and act. In other words, they must both support the international ‘regime’.

Krasner defined regimes as “principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actor expectations converge in a given area of international relations” (Krasner 1983a , p. 2). As a Realist, Krasner argued that states pursuing their own self-interests could create and use regimes to help attain objectives that they perceived to be in their national interest, such as continued economic openness. For example, as the hegemon, the US persuaded other countries to become contracting parties to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) free trade regime, which required that they adhere to the GATT’s principles of reciprocity and non-discrimination in trade, encouraged them to use the GATT’s dispute settlement process to resolve contracts in a multilateral way, and commited them to regular ‘rounds’ or multi-year negotiations to reduce barriers to trade. This clearly served US national interests because it made US trade relations with other contracting parties to the GATT more stable, predictable, and open. Once the regime was established, however, it would exert an influence of its own on the behavior of countries that joined the regime, making it easier for them to comply with the rules of the open global economy for a time at least, even after the hegemon’s power declined (Krasner 1983b ).

Keohane used a modified version Realist rational actor model to explain why countries would continue to support the free trade regime even in the absence of US hegemony. He argued that as the relative power of the US diminished, countries that were part of the regime would continue to adhere to its rules, norms, and operating procedures, and it would continue to constrain their behavior, in part because it served the national interests of these governments to continue to belong to the regime (Keohane 1984 ). While Keohane agreed with the Realist view that countries would pursue their own national interests, he argued that this did not prevent them from cooperating in adhering to the trade regime, or even changing the rules in a cooperative way, if needed, to create a modified regime. Regimes could help reduce uncertainty about other governments’ actions, thereby creating an environment more conducive to cooperation. If countries had at least some idea about how their trading partners would behave, then it would be easier for them to perceive that cooperating with each other to maintain an open global economy could be more beneficial to their long-term, overall national interests than responding to every trade dispute with retaliation.

Building on these concepts, we argue the United States and China are today acting as dual hegemons . Both have benefited from economic globalization and now, to advance their own national interests, both are committed to the principles of free trade and open foreign investment, despite some deviations from those principles on both sides (e.g., Steinberg and Josling 2003 ; Wu 2017 ).

China began opening its economy to imports and FDI in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. China reaped the benefits of the free trade regime as it prospered in the 1980s and 1990s. For this reason, it sought officially to become a permanent and full-fledged member of the regime, a goal it fulfilled when it became a full member of WTO in 2001. In that step the country cemented its commitment to an open trade regime, while domestically the economy continued to open further to domestic private-sector businesses and foreign investors (Garnaut et al. 2018 ).

As China adopted the norms of the open international order founded by the US, it became a beneficiary of that system. Within this context, China should see benefits in bolstering the norms of the system under which it has flourished. Therefore, it would not be in China's interest to implement policies that could threaten the open economic order. Likewise, the US should similarly continue to support the system that it established and has led, since it has benefitted the US itself as well as the other members of the system. Therefore, neither China nor the United States should take actions that could threaten this situation, for example by causing a destructive trade war with each other. Of course, the trade war started by the Trump Administration has led to Chinese retaliation—but despite the verbal and political positioning, US-Chinese trade had not declined dramatically prior to COVID 19. Footnote 3

By the same token, both countries should take efforts to provide the sorts of public goods that promote the open economic order. This dual willingness and ability to provide the public good of supporting the global open economic system has been demonstrated by both the US and China. The US took on this role after World War II and has not renounced this position despite ups and downs of populism at various times along the way, especially after 9/11 and during the Trump Administration. China has continued to increase its openness over the years after 1978, and has demonstrated a willingness to support other countries in trade, finance and FDI through the Belt and Road Initiative, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the BRICS Bank (now called the New Development Bank), and the Contingency Reserve Agreement.

The challenge to this system comes when one or both countries no longer see benefits to supporting it. The WTO can prevent protectionist backsliding by securing commitments to its rules and by providing a forum for governments to settle trade disputes. However, if one or both of the hegemonic powers renounce their obligations or take actions that significantly weaken the WTO, then there are few formal safeguards to prevent economic disputes from escalating into intensive protectionism. Worryingly, the Trump Administration has taken efforts to undermine the WTO and the multilateral trade regime more generally (Petersmann 2019 ; Skonieczny 2019), leading many scholars and analysts to declare the Post-WWII world order as dying or dead (Kagan 2017 ; Mearsheimer 2019 ; Walt 2016 ).

In practice, however, it is not clear that ‘Trumpism’ has undermined the global trading system. For example, his argument that “NAFTA is the worst trade deal ever” (e.g., Gandel 2016 ; The Economist 2017 ) led to its replacement by a renegotiated treaty (USMCA) in 2019 with very similar conditions, adding a higher local content requirement for automobile assembly and some additional labor protections. Likewise, Trump’s harsh criticism and rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017 has been replaced by his effort to negotiate a bilateral trade agreement with Japan and the continuation of existing bilateral treaties with other countries involved (e.g., Peru, Chile, and Australia). Additionally, in 2020 Gallup polls showed US people favor trade more than ever, suggesting that trade openness will persist going forward, Footnote 4 and the incoming Biden Administration is likely to show less overt hostility to the WTO or to existing US agreements.

At the same time China is opening up its financial services sector. New rules announced in January of 2020 allow foreign banks full ownership of their operations in China, and remove the limit on the size of their activities (Xinhuanet 2020 ). In March of that year, both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley were permitted to take majority ownership of their securities businesses in China (Yang 2020 ). China also has begun opening up the automobile market to foreign firms. In 2018 the Chinese government announced that electric vehicle production could be 100% foreign owned, and that by 2022 passenger vehicle production will be fully open to foreign ownership (Shirouzu and Jourdan 2018 ). In short, despite frictions between the two countries, openness to trade and investment have not declined in recent years. Footnote 5

Even if the US or China were to step back in their commitments to the WTO, there are hundreds of regional trade agreements (RTAs) that can fill the void in the multilateral trade regime left by a potentially weakened WTO (Murphy and McLarney 2018 ). RTAs began emerging in large numbers in the mid-1990s, as it became clear that successful WTO negotiations would be rare in the coming decades (Crawford and Laird 2001 ). These RTAs reduce tariffs between members, but also often provide many additional features that build upon existing WTO rules, such as robust intellectual property rights rules, dispute resolution mechanisms for trading partners, and investor protections (Hofmann et al. 2019 ). This patchwork of agreements covers even more countries than the WTO, and these agreements reinforce and even enhance WTO-level commitments. In doing so, they provide an extra guardrail against sharp protectionist backslides from the US, China, or other powerful states.

The US and Chinese economies are both reliant on economic globalization, with exports constituting approximately 12% of US GDP and 20% of China’s GDP in 2018. Moreover, these countries are highly dependent on one another, with the US being China’s largest import market and China being the US’s third largest import market (World Bank 2020a ). As noted previously, just as the fear of “mutually assured destruction” (MAD) provided a deterrent to war between the US and the USSR during the bipolar cold war era, the fear of “mutually assured recession” today should prevent either the US or China from taking actions that threaten the open economic order.

For these reasons, we expect that economic globalization will not suffer the sort of downturn predicted by realist international relations scholars and other observers. Instead, commitments to international organizations and agreements, as well as the threat of economic harm, should lead the US and China to support the open economic order for the foreseeable future.

3.2 Changes to Globalization in an Era of Dual Hegemons

This is not, however, to say that the character of the open economic order cannot be altered. As noted above, the US and China waged a costly trade skirmish in 2019 and the US has recently focused on restricting the access of Chinese technology firms to the US market (Pham 2020 ). It seems likely that isolated disputes such as these will occur with some frequency in the future, as the US and China each seek to limit the other’s influence. The likely result will be selective decoupling, as China finds itself partially or entirely excluded from certain sectors in the US, and vice versa. This has important implications for US companies, which might be inclined to seek Chinese investment or to build supply chains through China. While these companies will surely still seek Chinese engagement, the likelihood that disputes will flair up periodically suggests that a more diversified strategy will be necessary, even if it increases costs.

It is also likely that China and the US will each take efforts to build strategic alliances with other countries, such as through the formation of trade and investment agreements. For example, the US has offered Mexico and Canada preferential access to its market through USMCA, while China has offered countries such as Japan, Thailand, and Australia preferential access to its market through RCEP. As noted above, these agreements promote economic integration, going beyond what is agreed upon through WTO, but they also can foster trade diversion (Dai et al. 2014 ). Trade agreements are typically exempt from most favored nation (MFN) rules in the WTO, and so the proliferation of agreements with China or the US will affect trade patterns in ways that distort existing trade relationships. For example, a country like Thailand may trade more with China than with the US, even in areas where the US actually has a comparative advantage to China, simply because Thailand gains preferential access to the Chinese market through RCEP.

An additional concern about trade agreements is that they may be constructed in ways that prevent partners from forming subsequent agreements with certain countries. For example, USMCA has a clause that prevents member countries from forming trade agreements with “non-market” economies, which implicitly refers to China (Scissors 2019 ). This clause, or others like it, could be used by the US in future agreements to prevent their partners from forming trade agreements with China, and China could include similar provisions in its subsequent trade agreements to prevent partners from forming trade agreements with the US. This will not have the effect of ending trade between any of the countries involved, but it will likely lead to further trade diversion as countries such as Canada and Mexico are unable to establish agreements with China to lower trade barriers. This has important implications for supply chains, as MNEs must seek suppliers with an eye to trade diverting effects of future trade and investment agreements.

4 Economic Globalization in an Era of Dual Hegemons

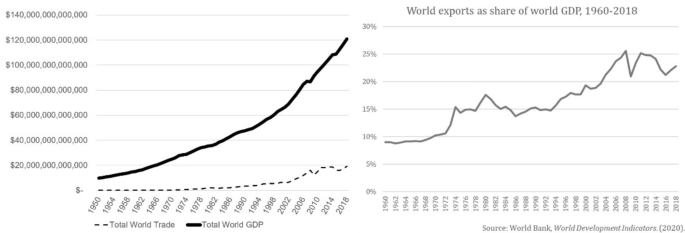

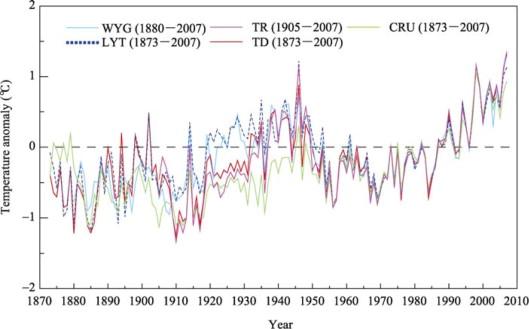

As discussed above, international relations theorists in the realist tradition predicted that a decline in global integration would accompany China’s rise and earlier work shows data appearing to support this prediction (Witt 2019 ). However, we show below that, despite the massive economic opening in China and increasing competition with the US for global economic leadership, economic globalization has remained quite stable. Consider Fig. 2 , which shows the trends in world trade since before China first opened its market, in 1978.

World exports and world GDP, 1960–2018

The figure shows that the growth of global trade has plateaued in the 2010s, but that it has not declined and that it remains at or near its peak. This is true whether we look at trade as a share of GDP, as Witt ( 2019 ) does, or if we simply look at trade volume independent of GDP. We believe that the latter measure is preferable, insomuch as trade growth may be obscured by faster growth in global GDP, as occurred in the 2014–2016 period. In any case, the figure clarifies that global trade has not declined, suggesting that deglobalization has not been occurring. Footnote 6

The major drop-offs in world trade growth since the early years of the Great Depression in the 1930s have been during World War II, and then, as shown in Fig. 2 , during the early 1980s emerging market debt crisis, as well as the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis, a global economic slowdown in 2016, and most recently during the Coronavirus crisis of 2020 (not shown). These events each had short-term impacts on globalization, but they did not lead to a sustained reduction in global trade (Coronavirus notwithstanding).

The 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis illustrates this point and, in the process, offers support for our dual hegemonic stability theory framework. Caused by a malfunction of the US financial system, in which banks and investors overexposed themselves to the real estate loan market and related derivatives, this crisis spread worldwide and caused a recession in many countries. Globalization did indeed decline for that brief period during the crisis. However, this decline proved short-lived, as the US government implemented policies to bolster the global financial system, while China began lending more money to countries around the world. Consistent with dual hegemonic stability, the two global leaders each provided global public goods that prevented what might otherwise have been a dramatic decline in globalization, akin to the one that occurred in the Great Depression.

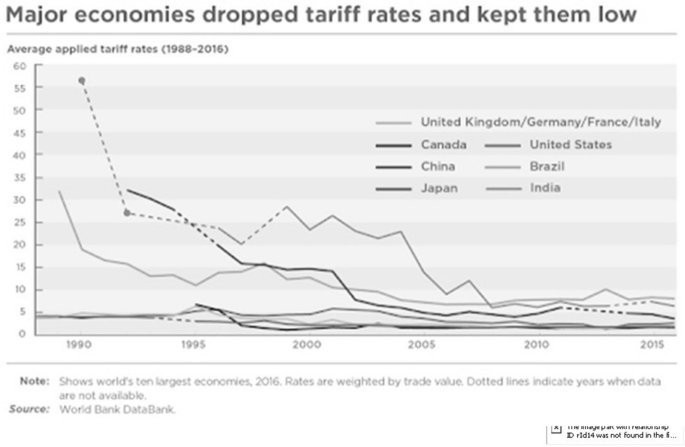

The trend in trade regulation over time is similarly at odds with the deglobalization narrative. Looking at average tariffs of major trading countries, it is evident in Fig. 3 that tariff barriers have continued to fall, from an already low level, since China joined the WTO in 2001.

Tariff rates in major trading countries

Non-tariff barriers to international trade, such as import quotas and subsidization of domestic firms to fend off imports, as well as subsidization of exports, have also remained low during the twenty-first century.

While tariffs have decreased steadily overall, there have been exceptions. The US continues to impose restrictions on steel and auto imports, as has frequently been done since Lyndon Johnson imposed steel import quotas in 1969. Ronald Reagan imposed restrictive policies in 1981 (on autos) and 1984 (on steel). Subsequent US Presidents, from George W. Bush (in 2002) to Barack Obama (in 2015) have restricted steel imports with tariffs or quotas, often as a result of claims that foreign governments were unfairly subsidizing their steel exports. These examples suggest that the Trump Administration’s protectionism is not out of line with US policy in the past, contrary to suggestions that the Administration is leading a decline of the global economic order (Walt 2016 ). Of course, the Trump Administration has implemented its share of protectionism, such as the recent ban on Huawei from selling its telecom equipment in the United States, based on a claim that Huawei was supplying or could supply information about users of the telecom system to the Chinese military (Swanson 2020 ).

For its part, China also restricts auto imports with high tariffs and subsidies for domestic producers (including subsidiaries of foreign automakers). China also keeps foreign firms out of what they consider sensitive industries such as telecommunications, and they limit foreign financial services firms to a tiny market share in China. China restricts imports of several agricultural products, such as wheat and rice—just as the United States has done for decades. In short, while both countries have exceptions to a free trade policy, over half of the products imported into both countries enter without restrictions, with an overall average tariff of 1.6% in the US and 3.4% in China in 2019 (United States Trade Representative 2020 ; World Bank 2020a ).

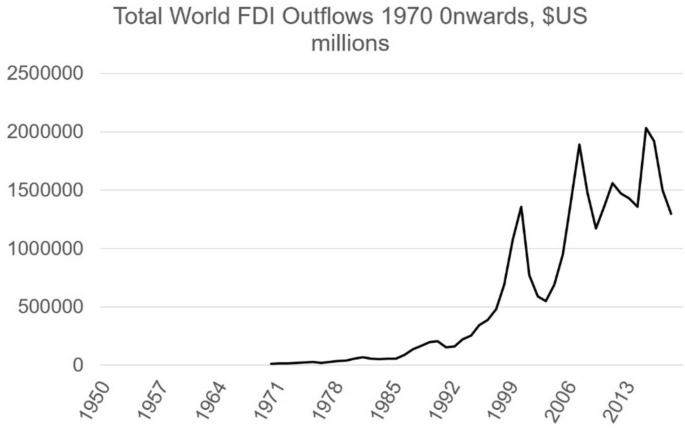

Considering other measures of economic openness, FDI is often seen as an indicator of countries’ willingness to allow foreign business to operate locally. The growth of FDI after World War II has been more rapid than growth of GDP for most of the period. As shown in Fig. 4 , the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2009 was accompanied by a major downturn in FDI, and since then the growth of this investment has been volatile, though still positive overall. The key point with respect to globalization is that FDI has remained at or near its peak in the years since China emerged as a global power on-or-near par with the US.

Global and regional FDI inflows, 1970–2018

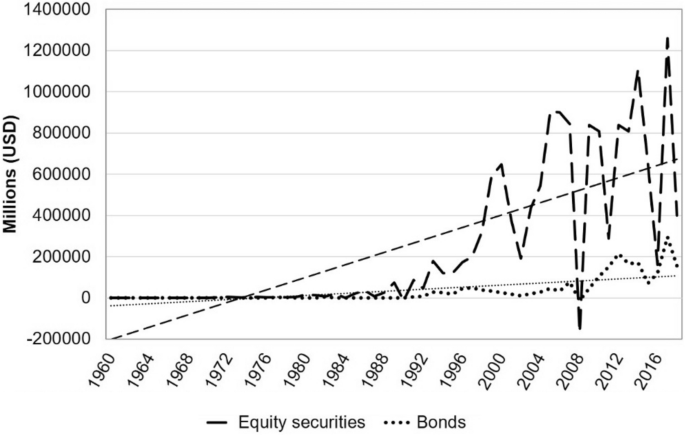

Likewise, global financial flows such as international portfolio investment and foreign exchange transactions have trended upward, albeit with considerable volatility and with a decline during the Global Financial Crisis. Foreign exchange transactions, mainly in London and New York, exceeded $6 trillion per day in 2019 compared with $1.2 trillion in 2001 (Bank for International Settlements 2019 ). Global portfolio investment grew at an average rate of 44% per year during the 2010s, but it has been very volatile, as shown in Fig. 5 . It is clear that globalization has not declined by these financial measures.

Source: World Bank 2020b

Cross-border portfolio investment, 1960–2018.

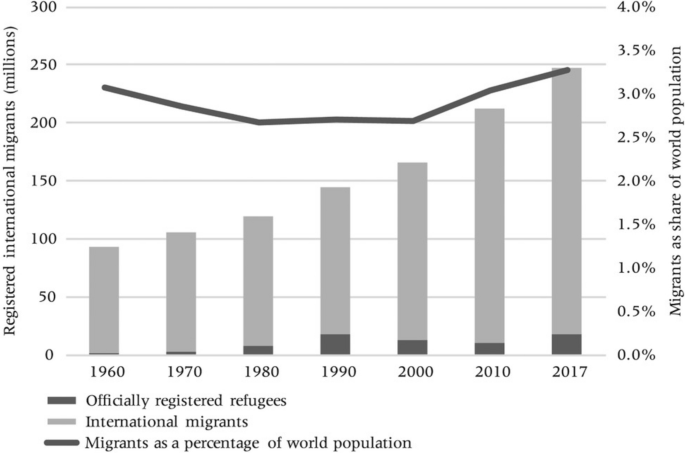

International immigration flows are another measure of economic openness, involving people as the factor that crosses borders. People and capital are generally viewed as the two mobile factors of production, while land is not. And final products and services also may or may not be mobile, as measured by trade flows. It is clear in Fig. 6 that global migration flows have not decreased during the 2010s, but rather they show an increasing rate since the turn of the century.

Source: de Haas et al. 2019 , p. 888. Authors' calculations based on the Global Migrant Origin Database (World Bank) (1960–1980 data) and UN Population Division Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2017 Revision (1990–2017 data)

International migration flows, 1960–2017.

The evidence presented in this section contests the deglobalization narrative, showing instead that the global flows of products, money, and people have increased in the twenty-first century and remain near their peaks, and supporting our Proposition 1 .

5 Dual Hegemonic Stability and International Business in the Twenty-First Century

While much of the discussion above has focused on macro indicators of international openness and government policies, it all relates to business, mostly to international business. Our principal measure of openness is the amount of trade and investment taking place, and of course it is companies that are carrying out those exports, imports and investments. International bank lending and foreign exchange are mainly carried out by multinational banks, operating principally in London and New York. Footnote 7 Likewise, some international movement of people occurs within multinational firms. These indicators all show positive growth trends in the twenty-first Century, even after the Global Financial Crisis.

From a business perspective, dual hegemonic stability means that countries will maintain an open market environment of the sort that has been demonstrated to attract FDI and also international trade (Ahlquist 2006; Büthe and Milner 2008; Gamso and Grosse 2020 ). In this context, global companies will continue to engage in trade and investment around the world and do not need to dramatically reorient themselves in response to, or in anticipation of, a wave of tariff hikes or other non-tariff barriers. Supply chains can continue to function and may even deepen as China’s Belt and Road projects bring more countries into the globalized economy. Companies around the world can also expect both China and the US to remain largely open to global business, with positive implications for those firms that are interested in expanding into these markets. Of course, globalization creates losers as well as winners, and our analysis suggests that import-competing companies will not see their fortunes improve in a world of dual hegemonic stability.

That said, US–China skirmishing to build greater economic and political power will produce some policy changes that do constrain firms. Economic issues such as ‘unfair’ trade restrictions on both sides can lead to higher-cost exports if new tariffs are imposed on specific products, even though tariff barriers overall are quite low in both countries. Specific restrictions, as the US has imposed on auto and steel imports from several countries on and off over the past six decades, do raise significant barriers in those sectors. Likewise, China’s refusal to allow foreign telecom companies to provide various services in China, and precluding trans-border transfer of information from China, severely restrict leading US companies in that sector. Chinese government subsidization of state-owned companies in many sectors enables them to compete overseas with an advantage that is difficult to measure and restrain, although it is possible to deal with this challenge through the WTO.

Multinational firms interested in operating in China will continue to have to deal with the restrictions there in sectors such as automobiles, financial services, telecommunications, electric power and operation of any business that requires cross-border transmission of customer information. Constraints there have hobbled the businesses of Google, Facebook, and Amazon Web Services. Auto companies since the 1980s have faced the requirement to operate only with a joint venture partner that owns at least 50% of the company in China. This last point suggests that a strategy for other kinds of firms may be to use a joint venture partner to avoid potential limitations that the government might impose (Zhu and Sardana 2020 ). And from the opposite perspective, at least for Chinese SOEs, their performance has been better when they have foreign investors involved, such as SAIC with GM and Volkswagen and foreign listings that attract portfolio investors (Zhu et al. 2019 ).

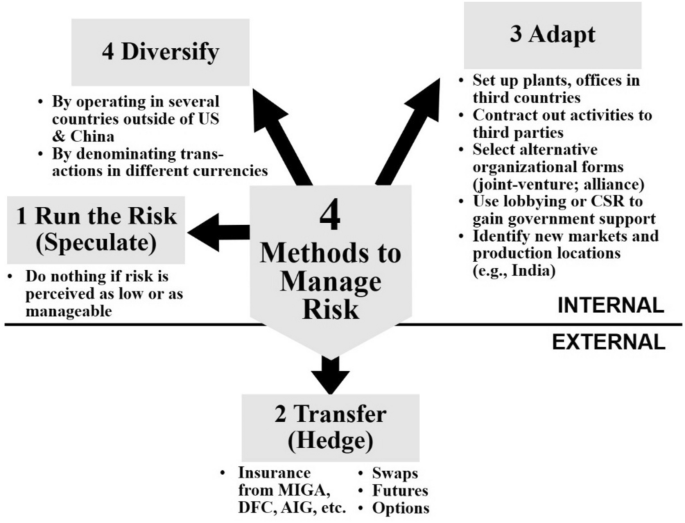

To deal more comprehensively with these risks, we suggest a geopolitical risk management framework within which companies can design strategies to reduce the potential negative impacts of US–China government decisions. The framework is depicted in Fig. 7 .

Geopolitical risk management framework

The framework points out four categories of responses to geopolitical risks. First is to simply run the risk when it is perceived to be low or manageable. This strategy will be useful for companies that are not exposed to business activity in the US or China, or for companies that operate only domestically in the US or China. For example, European firms that operate hotels, restaurants, local professional services, and other businesses that are highly local can likely avoid the risk. The more local or regional the business and the supply chain, the more likely that the avoidance strategy can serve well.

Another aspect of this avoidance strategy to deal with US–China conflict suggests that companies should look to avoid putting their business in one of the risky countries, if that risk indeed is very significant for the particular firm or industry (e.g., US defense contractors staying away from Chinese operations, and Chinese companies such as Huawei, TikTok and other Internet companies that could transfer US information to the Chinese military staying away from the US). Many times this is not possible, but when the US-based or Chinese firm can operate in other countries, this can help reduce their bilateral risk.

A second category of response to geopolitical risk is to transfer it to a third party. Insurance is the most common mechanism to accomplish this goal. A political risk insurance policy for a US company from the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) can insure its business in an emerging market against political violence including terrorism, currency inconvertibility and government interference in the firm’s business activities, including expropriation. Similar policies are available from the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) in the World Bank group for companies from any member country operating in an emerging market. Private sector insurance policies against political risk are available from companies such as AIG and Zurich Insurance. This category of response could serve the interests of companies that require significant capital investment in facilities in the host country, such as manufacturing companies, hotels, mining companies, and agricultural companies.

Additional means of transferring geopolitical risks to third parties include measures for guaranteeing delivery of a product that may be a part of a company’s supply chain. For example, if oil is needed for the company’s business, (deliverable) futures contracts exist that guarantee a price and the delivery of a specified quantity of oil at a particular future date (e.g., for 1000 barrels per contract at the New York Mercantile Exchange). Similar contracts exist for some other commodities and at some other exchanges as well. Options contracts and swaps for commodities provide additional sources of protection against the risk of breakdowns in a supply chain.

A third strategy dimension is to adapt the company’s business to deal with the risk. This strategy includes setting up plants or offices or other facilities in countries other than China or the US to avoid the direct threat of government intervention. Footnote 8 A company such as Apple can contract out with other companies to provide components for their iPhones and even assembly of those phones, as Apple has done for many years. If key suppliers are in the US or China, then Apple can look to providers in third countries. For any company, if China is the location of production facilities, then adaptation could involve moving to another emerging market in Asia, from Vietnam and Thailand to India.

Chinese firms interested in operating in the US are likely to find more constraints in the way that Huawei and ZTE have experienced in telecommunications equipment and TikTok is experiencing in online video sharing. National security concerns easily could be extended to other sectors, from agricultural products to pharmaceuticals. A Chinese company in many industries would be best served by adapting its business via operating with a US partner, and maybe even operating through a subsidiary in another country such as the UK or maybe Dubai/UAE or the Cayman Islands. Populist pressures as well as national security concerns will likely make it more difficult for a range of Chinese companies to enter the US in the future.

Adapting the company’s business financially may also be beneficial, for example, by taking on local debt in the country where local assets are exposed to risk. Just balancing accounts payable and receivable for a western company in China or a Chinese company in the US could limit the exposure of assets to some extent. Broadly speaking, building up local liabilities where local assets are at risk will help to protect the company.

Many additional possibilities exist to adapt the company’s business activities so that geopolitical risk can be reduced. For both US-based and Chinese companies, finding a joint venture partner in the other country may reduce the risk of negative government policy changes toward that company (Johns and Wellhausen 2016 ), as might working with an intergovernmental organization such as the World Bank (Gamso and Nelson 2019 ). For European or emerging market-based companies, finding production locations outside of the US and China can reduce the risk, as can looking to additional markets in other countries such as the EU, India, and other large economies. Aiming directly at the government of China or the US to curry favor, through corporate social responsibility programs (Darendeli and Hill 2016 ) or just lobbying (Keillor et al. 2005 ) can also be useful tools.

The fourth and final category of responses is to diversify the company’s business outside of the US and China. This diversification of business activities does not reduce the risk to a particular facility or supply source in the US or China, but it does enable the firm to have alternative(s) in the event of adverse policy moves by either of those governments. So, as with any diversification strategy, moving some activities outside of the two protagonist countries will enable a company to reduce the overall impact of adverse policies on its total business worldwide. An MNE also could aim to denominate more of its business in currencies other than dollars or renminbi, to avoid possible harmful exchange rate changes in response to policies in either the US or China.

This current reality suggests that companies should look to diversify their markets and supply chain activities. Already, a significant amount of reshuffling of offshore production in textiles and electronics has seen assembly activities move from China to other countries in Asia such as Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as India (Hufford and Tita 2019 ). China’s large market remains very attractive to many multinationals, but India’s market has grown faster in several recent years and provides possible diversification opportunities. And on the other side of the Pacific, the US has recently used policies to dissuade companies from dealing with China, so that a strategy of focusing more on Europe, Japan, and non-China emerging markets makes sense as well for multinationals, even though a significant decoupling of the US and Chinese economies seems unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Each of these strategies implies a move to greater emphasis on risk management and less focus on lean supply chains that has dominated in recent years. In fact, multinational firms would be well-served by implementing a range of risk-management tools, as suggested by our Proposition 2 and shown in Fig. 7 and Table 2 in the “ Appendix ”.

An open global economy does not mean that companies should naive the risks associated with international business in the context of a changing world order. More short-term trade or investment barriers could be implemented, as the US and China use these policies to compete with one another in various areas of international business and international relations. The bilateral jockeying for position in the international system between China and the US will be a feature that firms will need to contend with for the foreseeable future. Additionally, trade and investment diversion stemming from new bilateral and regional economic agreements must be factored into firms’ assessments as they identify suppliers and consider investments.

6 Long-Term Dual Hegemonic Stability

There are challenges to the long-term persistence of dual hegemonic stability. These include political tensions between the United States and China, the rise of political nationalism around the world, and the COVID 19 pandemic. The first challenge is the emerging tension between the US and Chinese governments. Tensions over China’s economic policies generated a serious trade dispute between the two countries, which has been partially resolved with the 2020 Phase One trade agreement (Setser 2020 ). These economic tensions are likely to reemerge and other disputes will surely arise as well. If tensions become sufficiently intense, there is a possibility that the countries will engage in a Cold War-type standoff, perhaps leading other countries to trade intensively with one party or the other. As discussed above, we do not see this as a likely outcome, given the membership of China and the US in the WTO, as well as the enormous economic benefits that both countries obtain from allowing the open economic system to operate. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning, as this outcome is seen as likely by some analysts (e.g., Khong 2019 ).

The second challenge is the rise of political nationalism around the world. In the latter half of the 2010s, nationalist governments came to power in the United States, Brazil, countries of Western Europe, the Philippines, Turkey, and elsewhere (Snyder 2019 ). China’s government may also be described as nationalistic (Economy 2014 ), even though it sometimes shows support for global governance (Kastner et al. 2020 ). Despite some new tariffs, this political nationalism has not led to widespread protectionism, but it has been accompanied by efforts (some successful) to undermine organizations like the WTO (Brown and Irwin 2019 ). If political nationalism leads to more sustained economic nationalism, particularly from the United States and China, which are the world’s two largest traders, then it may lead to a deterioration of hegemonic stability. This is not currently in the interest of either state, but interests may change in the future.

Military conflict, such as a possible skirmish in the South China Sea, is also conceivable. Any attack by a Chinese ship or plane on a US ship operating in international waters that the Chinese claim as their own could lead to escalation of some sort. Ramped-up military attacks are not likely, but economic sanctions certainly are. This would push each hegemon to raise more economic barriers on the other, and hurt MNE interests. While this is far from a Pearl Harbor or a frontal attack on the other hegemon, still such skirmishes are likely, and their policy implications are something that companies should plan for.

COVID 19 may exacerbate the first two challenges. The virus appears to be worsening relations between the United States and China, at least in the short term (Buckley and Myers 2020 ). Likewise, there are some indications that COVID 19 is encouraging countries to turn inward, in an effort to increase self-sufficiency (Irwin 2020 ). However, it is too soon to say how exactly the 2020 pandemic will affect global commerce in the coming years and decades, and there are reasons to suspect that its long-term impacts on globalization will not be severe (O’Neill 2020 ). Nevertheless, this unprecedented challenge must be acknowledged.

These possibilities notwithstanding, the most likely scenario for world order in the twenty-first century is ongoing economic globalization, led by two states that have persistently supported and benefited from this status quo. Continuing to support globalization is in the best interests of both of these states, and so we expect them each to continue providing global public goods that incentivize global trade and investment. Therefore, contrary to the increasingly common journalistic narrative, globalization should persist for the foreseeable future. Even with a continuation of globalization, companies need to be prepared to deal with bilateral frictions between the US and China, so the four-pronged risk management strategy described above can help them to manage future shocks.

It should be noted that there are dissenting opinions to this emerging conventional wisdom, as some analysts are skeptical of US decline (e.g., Brooks and Wohlforth 2016a , b ), others are skeptical of China’s rise (e.g., Lynch 2019 ), and still others propose that a multipolar world order has emerged (e.g., Mearsheimer 2019 ).

While one could debate the appropriateness of R&D spending as a measure of innovation, the US-China dual leadership also is evidenced by patents and trademarks granted, and by other measures collected by the World Intellectual Property Organization ( 2019 ). While no measure of innovation is complete, the various indicators all point toward US-China leadership.

US-China trade was valued at $578 billion, with a US deficit of $347 billion, in the last year of the Obama administration (2016). US-China trade was valued at $558 billion, with a US deficit of $345 billion, in 2019.

“More Americans than Gallup has seen in a quarter century view foreign trade positively, with 79% calling it "an opportunity for economic growth through increased U.S. exports" (Saad 2020 ).

This is not to deny the real trade barriers that have been imposed on US-China trade by President Trump since 2017, and the retaliation by China’s government. These restrictions, mainly tariffs, have had some impact on that trade, though it continues fairly similar in volume and value to previous years, with some exceptions.

Of course, this does not take into account the impacts of COVID 19 on global trade.

It would be logical to expect Hong Kong, or even Shanghai, to join London and New York as the chief global financial centers. For several reasons, mainly to do with political risk of the Chinese government in Hong Kong, this last center has not (yet) developed on the level of the London or New York.

If the company is changing an existing activity, such as moving production out of China, or contracting production to a third party, then this is adaptation. If the company adds new operations outside of China or the US to deal with this geopolitical risk, then this would be diversification, as discussed in the next category.

Bank for International Settlements (2019). Triennial Central Bank Survey. https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx19_fx.pdf . Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Beeson, M., & Li, F. (2016). China’s place in regional and global governance: A new world comes into view. Global Policy, 7 (4), 491–499.

Google Scholar

Brennan, D. G. (1971). Strategic alternatives: I. New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/1971/05/24/archives/strategic-alternatives-i.html . Accessed 1 Dec 2020.

Brooks, S. G., & Wohlforth, W. C. (2016a). The rise and fall of the great powers in the twenty-first Century: China’s rise and the fate of America’s global position. International Security, 40 (3), 7–53.

Brooks, S. G., & Wohlforth, W. C. (2016b). The once and future superpower: Why China won’t overtake the United States. Foreign Affairs, 95 (3), 91–104.