- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The emergence of ballet in the courts of Europe

Ballet as an adjunct to opera.

- The establishment of the ballet d’action

- The age of Gardel

- Ballet as an aspect of Romanticism

- The Imperial Russian Ballet

- The era of the Ballets Russes

- Russian ballet in the Soviet era

- The growth of national ballet companies in Europe and North America

- The East-West divide

- The institutional environment

- Ballet and the public

- Choreographers

- Ballet in the cultural milieu

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Community College of Rhode Island - World Languages and Cultures - The History of Ballet

- The Kennedy Center - Ballet Basics

- PressBooks - Storytelling - The History of Ballet

- ballet - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- ballet - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

ballet , theatrical dance in which a formal academic dance technique—the danse d’école—is combined with other artistic elements such as music , costume, and stage scenery. The academic technique itself is also known as ballet. This article surveys the history of ballet.

History through 1945

Ballet traces its origins to the Italian Renaissance , when it was developed as a court entertainment. During the 15th and 16th centuries the dance technique became formalized. The epicentre of the art moved to France following the marriage of the Italian-born aristocrat Catherine de Médicis to Henry II of France. A court musician and choreographer named Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx devised Ballet comique de la reine (1581; “The Queen’s Comic Ballet”), which inaugurated a long tradition of court ballets in France that reached its peak under Louis XIV in the mid-17th century.

As a court entertainment, the works were performed by courtiers; a few professional dancers were occasionally participants, but they were usually cast in grotesque or comic roles. The subjects of these works, in which dance formed only a part alongside declamation and song, ranged widely; some were comic and others had a more serious, even political, intent. Louis XIII and his son Louis XIV frequently performed in them; the younger Louis was in time regarded as the epitome of the noble style of dancing as it developed at the French court.

Eventually, developments at the French court pushed the arts aside, and the court ballet disappeared. But Louis XIV had established two academies where ballet was launched into another phase of its development: the Académie Royale de Danse (1661) and the Académie Royale de Musique (1669). The Académie Royale de Danse was formed to preserve the classical school of the noble dance. It was to last until the 1780s. By then its purpose essentially had been abrogated by the music academy, the predecessor of the dance school of the Paris Opéra .

The Académie Royale de Musique was to become incalculably significant in the development of ballet. The academy was created to present opera, which was then understood to include a dance element; indeed, for fully a century ballet was a virtually obligatory component of the various forms of French opera. From the beginning, the dancers of the Opéra (as the Académie was commonly known) were professional, coming under the authority of the ballet master. A succession of distinguished ballet masters (notably Pierre Beauchamp , Louis Pécour, and Gaétan Vestris ) ensured the prestige of French ballet, and the quality of the Opéra’s dancers became renowned throughout Europe.

The growing appeal of ballet to an increasingly broad public in Paris was reflected in the success of opéra-ballets , of which the most celebrated were André Campra ’s L’Europe galante (1697; “Gallant Europe”) and Jean-Philippe Rameau ’s Les Indes galantes (1735; “The Gallant Indies”). These works combined singing , dancing, and orchestral music into numbers that were unified by a loose theme.

In the early years the most accomplished dancers were male, and it was not until 1681 that the first principal female dancer, Mlle La Fontaine , appeared. Gradually she and her successors became nearly as well-known and respected as male dancers such as Michel Blondy and Jean Balon . From the 1720s, however, with the appearance of Marie Sallé and Marie-Anne Camargo , the women began to vie with the men in technique and artistry. The retirement of Sallé and Camargo in turn coincided with the debut of one of the most celebrated dancers of all time, Gaétan Vestris , who became regarded in his prime as the epitome of the French noble style; he played an important part in establishing ballet as an independent theatrical form.

Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre

2900 Liberty Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15201-1500

(412) 281-0360 [email protected]

A Brief History of Ballet

Scroll through a brief ballet history from its where ballet originated in the 15th-century Italian renaissance courts to what ballet dance looks like in the 21st century.

Origin of Ballet

Ballet originated in the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century. Noblemen and women were treated to lavish events, especially wedding celebrations, where dancing and music created an elaborate spectacle. Dancing masters taught the steps to the nobility, and the court participated in the performances. In the 16th century, Catherine de Medici — an Italian noblewoman, wife of King Henry II of France and a great patron of the arts — began to fund ballet in the French court. Her elaborate festivals encouraged the growth of ballet de cour, a program that included dance, decor, costume, song, music and poetry. A century later, King Louis XIV helped to popularize and standardize the art form. A passionate dancer, he performed many roles himself, including that of the Sun King in Ballet de la nuit . His love of ballet fostered its elevation from a past time for amateurs to an endeavor requiring professional training.

By 1661, a dance academy had opened in Paris, and in 1681 ballet moved from the courts to the stage. The French opera Le Triomphe de l’Amour incorporated ballet elements, creating a long-standing opera-ballet tradition in France. By the mid-1700s French ballet master Jean Georges Noverre rebelled against the artifice of opera-ballet, believing that ballet could stand on its own as an art form. His notions — that ballet should contain expressive, dramatic movement that should reveal the relationships between characters — introduced the ballet d’action , a dramatic style of ballet that conveys a narrative. Noverre’s work is considered the precursor to the narrative ballets of the 19th century.

The 19th Century

Early classical ballets such as Giselle and La Sylphide were created during the Romantic Movement in the first half of the 19th century. This movement influenced art, music and ballet. It was concerned with the supernatural world of spirits and magic and often showed women as passive and fragile. These themes are reflected in the ballets of the time and are called romantic ballets. This is also the period of time when dancing on the tips of the toes, known as pointe work , became the norm for the ballerina. The romantic tutu, a calf-length, full skirt made of tulle, was introduced.

The popularity of ballet soared in Russia, and, during the latter half of the 19th century, Russian choreographers and composers took it to new heights. Marius Petipa’s The Nutcracker , The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake , by Petipa and Lev Ivanov, represent classical ballet in its grandest form. The main purpose was to display classical technique — pointe work, high extensions, precision of movement and turn-out (the outward rotation of the legs from the hip)—to the fullest. Complicated sequences that show off demanding steps, leaps and turns were choreographed into the story. The classical tutu, much shorter and stiffer than the romantic tutu, was introduced at this time to reveal a ballerina’s legs and the difficulty of her movements and footwork.

Ballet Today

In the early part of the 20th century, Russian choreographers Sergei Diaghilev and Michel Fokine began to experiment with movement and costume, moving beyond the confines of classical ballet form and story. Diaghilev collaborated with composer Igor Stravinsky on the ballet The Rite of Spring , a work so different —with its dissonant music, its story of human sacrifice and its unfamiliar movements — that it caused the audience to riot. Choreographer and New York City Ballet founder George Balanchine, a Russian who emigrated to America, would change ballet even further. He introduced what is now known as neo-classical ballet, an expansion on the classical form. He also is considered by many to be the greatest innovator of the contemporary “plotless” ballet. With no definite story line, its purpose is to use movement to express the music and to illuminate human emotion and endeavor. Today, ballet is multi-faceted. Classical forms, traditional stories and contemporary choreographic innovations intertwine to produce the character of modern ballet.

What’s Next?

Choreographers continue to create diverse styles of ballets, and ballet companies are giving dance audiences a wide range of experiences in the theater. What do you think will be the next phase for ballet?

Learn More!

- Listen to an NPR interview with author Jennifer Homans about Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet , a book published in 2010.

- Read more about types of ballet or ballet vocabulary

- Or, check out the following at your local library or bookstore, or at Amazon.com:

Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet, by Jennifer Homans, 2010

Ballet: An Illustrated History , by Clement Crist and Mary Clark, 1992

Ballet and Modern Dance: A Concise History , by Jack Anderson, 1993

Ballet in Western Culture: A History of its Origins and Evolution, by Carol Lee, 1992

Experience ballet for yourself with classes for all ages , including adult beginning ballet classes. Or, introduce your little ones to ballet with Dance the Story at Home !

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Tracing Ballet's Cultural History Over 400 Years

Jenifer Ringer performs as the Sugarplum Fairy during a 2010 performance of "The Nutcracker" at Lincoln Center in New York. Paul Kolnik/AP Photo hide caption

Jenifer Ringer performs as the Sugarplum Fairy during a 2010 performance of "The Nutcracker" at Lincoln Center in New York.

This interview was originally broadcast on December 13, 2010 . Apollo's Angels is now available in paperback.

It is ballet season, which means many companies are performing The Nutcracker for the holidays and preparing their big shows for the winter months. Everywhere you turn these days, you can see toe shoes — but there is a deep and fascinating history to the art form that few people know.

In her new book Apollo's Angels , historian Jennifer Homans — a former professional ballet dancer herself — traces ballet's evolution over the past 400 years, and examines how changes in ballet parallel changing ideas about class structure, gender, costume, the ideal body and what the body can physically do. The book chronicles ballet's transition from the aristocratic courtier world in Europe through its place as a professional discipline in the Imperial Court of Russia, and finally as a technique performed on stages throughout the world.

Apollo's Angels

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Ballet's origins, Homans explains, grew out of the Renaissance court cultures of Italy and France. Dancers would perform at the royal courts — and then invite the audience members to participate.

"It was a dance that was done by courtiers and kings and princes at court in social situations," she says. "It was not a theatrical art set off from social life."

The first ballet dancers did not wear tutus or dance in satin shoes, but they did formalize the footwork patterns — known as first, second, third, fourth and fifth position — that are still used today.

"Louis XIV realized that if his art form was going to be disseminated throughout his realm and even to other European countries, he would have to find a way to write it down," Homans explains. "So he asked [choreographer] Pierre Beauchamp to write some these positions. The positions themselves are the grammars of ballet, they're the ABC's, the classical building blocks of ballet."

In ballet's early days, men were expected to perform the more extravagant and intricate footwork. It wasn't until years later, during the French Revolution, that female dancers became stars.

"During the French Revolution, the aristocratic male dancer was really discredited," she says. "The hatred and bitter animosity toward the aristocracy had direct consequences for ballet. Why should you have this aristocratic art? If you're going to take down the aristocracy, why not take down ballet, too?"

By the 1830s, men were actually reviled onstage, she says.

"They're thought to be a disgrace," she says. "Female dancers take the ideals that existed in the aristocratic art form and turned them into a feminine and spiritual ideal of which they are the masters. Then you get this image of the ballerina on toe, in these more romantic-era ballets of sylphs and unrequited love and the romantic themes that carried ballet into the 19th century."

Apollo's Angels was recently named one of the top five nonfiction books of the year by the New York Times Sunday Book Review . Jennifer Homans performed with the Chicago Lyrica Opera Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet and Pacific Northwest Ballet during her career as a professional ballet dancer. She is currently the dance critic for The New Republic, and teaches the history of dance at New York University, where she is a distinguished scholar-in-residence.

Jennifer Homans has danced with the Pacific Northwest Ballet and the Chicago Lyric Opera House. She has a Ph.D. in modern European history from New York University. Random House hide caption

Jennifer Homans has danced with the Pacific Northwest Ballet and the Chicago Lyric Opera House. She has a Ph.D. in modern European history from New York University.

Interview Highlights

On Apollo's relationship to dance

"From the earliest moments of ballet, the idea was to create some kind of Apollonian image — an ideal sort of body. Even the technique allowed you to modify your, perhaps, imperfect proportions. If you're too tall, maybe you would lower your arms a bit — maybe so you don't appear so high up."

On the fear of being dropped

"I never was thinking that, because within the flow of the movement, you have complete confidence in the partner that you're working with, and so those kinds of considerations are not to the fore. Now, if you're working with somebody you don't quite trust or there's a lift that's particularly difficult, then I think there can be a certain tension. And that's something you want to try to get rid of in a performance. One of the great ballerinas once told me, 'When you start to have a dialogue in your head while you're performing, that's when you know it's gone wrong.' In a way, you want to get rid of those words and enter a different way of existing for the time that you're onstage."

Related NPR Stories

Dmitri shostakovich: a dangerous ballet.

On the transition from dance as an aristocratic pastime to a professional discipline

"You start to have a more difficult technique that even the most diligent aristocrats can't keep up with by the end of the 17th century. And then dancers are becoming professionals, and that's when you have more and more separation between the aristocrats who are watching the dance and the people who are performing it. And the dancers at that point are much more exclusively drawn from the lower orders of society. They are learning, in a way, to become aristocrats. On stage, they appear as noblemen, even if in society they're emphatically not."

On dancing en pointe

"It's really the point in which popular traditions feed into a high operatic, high balletic art. Marie Taglioni is the ballerina we most associate with en pointe work. She was working in Vienna at the opera house, but a lot of Italian troupes were passing through. These troupes often did tricks, and one of the tricks they'd do was to climb up on their toes and parade around. This kind of trick was then incorporated into classical ballet. It was given an elevated form, so instead of stomping around, it became an image of the ethereal, a wispy sylph or somebody who can leave the ground or fly into the air."

Learn Ballet History

Ballet is a relatively young art form, with the earliest recorded mention of ballet dating back to the 15th century, or about 400 years ago. This article delves into ballet history and how it developed.

The origins of the term ‘ballet’ are uncertain, with some sources suggesting it derives from the Latin word ‘balle’ (meaning dancing) and others suggesting it comes from the French ‘balleto.’ However, it is clear that ballet originated in a specific place. In the following article, we will explore the history of the development and popularization of this elegant art form.

Origin – 16th century ballet history

It is known that ballet originated during the Renaissance in Italy. The first mention of the word “ballet” is attributed to the court dance teacher Domenico da Piacenza. It was he who first proposed to combine several dances into one, perform them with a solemn finale and call them ballet.

The progenitor of classical dance is those forms of dance that were performed by hired dance masters for the nobles and princes at their celebrations. It was at such events that the original choreographic forms, the splendor of the spectacle, and the elements of drama in dance performances were born. Who would have thought that the usual entertainment of sovereigns would over time turn into art that millions of people around the world enjoy today?

However, as a genre of art, the ballet took shape a little later. As we said earlier, ballet originated in Italy, but the first ballet production of The Queen’s Comedy Ballet was presented not in Italy, but in France in 1581 . It was staged at the court of Catherine Medici of Italy, wife of the French King Charles VIII.

It was she who brought fashion for curious court ballets to France. The production was directed by the famous Italian choreographer and violinist Baltazarini di Beljoyozo from Italy. Since then, the ballet has moved to a professional stage where it occupied a certain place in opera and dramatic productions .

Mid 17th – 18th centuries

During this period of ballet history, this classical dance form continued to evolve about a century later, with the coronation of Louis XIV in France on June 7, 1654. Louis XIV was not only a fan of ballet, but also participated in productions himself, performing in the “Cassandra Ballet” at the age of 12 in 1651.

He earned the nickname “Sun King” for his role as the Rising Sun in “The Royal Ballet of the Night”. In 1661, Louis XIV established the Royal Academy of Dance to preserve dance traditions, with 13 of the best dance masters appointed to the Academy. Pierre Boschant , a royal dance teacher, was appointed director and later defined the five main positions of classical dance.

Louis XIV made the ballet stand out during his reign as a separate form of performance, different from balls. It was then that the division of dancers into amateurs and professionals appeared.

Ballet history fact!

Before 1681 only men danced in ballet. The first ballerina was the legendary dancer La Fontaine.

Then costumes and music were more important during performances than the dance technics. Girls danced in high heels wearing heavy dresses and masks. The costume of a man, although it was a little lighter (hence the greater grace and ease of movement), was still far from the clothes in which you could dance easily and freely.

The first to free the dancers from the shackles of these inconvenient costumes was a real reformer in the world of ballet art – the French ballet master Jean Georges Nover . He banned masks and gave the actors the opportunity to wear light suits that did not stiffen movement. Each innovation made dance more meaningful, and dance technique – more complicated.

Towards the end of the 17th century, court ballet achieved some success: it was fully funded by the authorities, which used it to exalt their own greatness. Gradually, the ballet completely separated from the opera and turned into an independent art .

One of the successful followers of Noverre became Jean Doberval, who in 1789 staged the ballet “Futile Precaution” . A simple story about the unhappy love of a young peasant and a village girl was presented on stage. The absence of stories about the adventures of the gods, majestic masks and corsets made the production natural, and the dance free.

Romanticism – late 18th – early 19th centuries

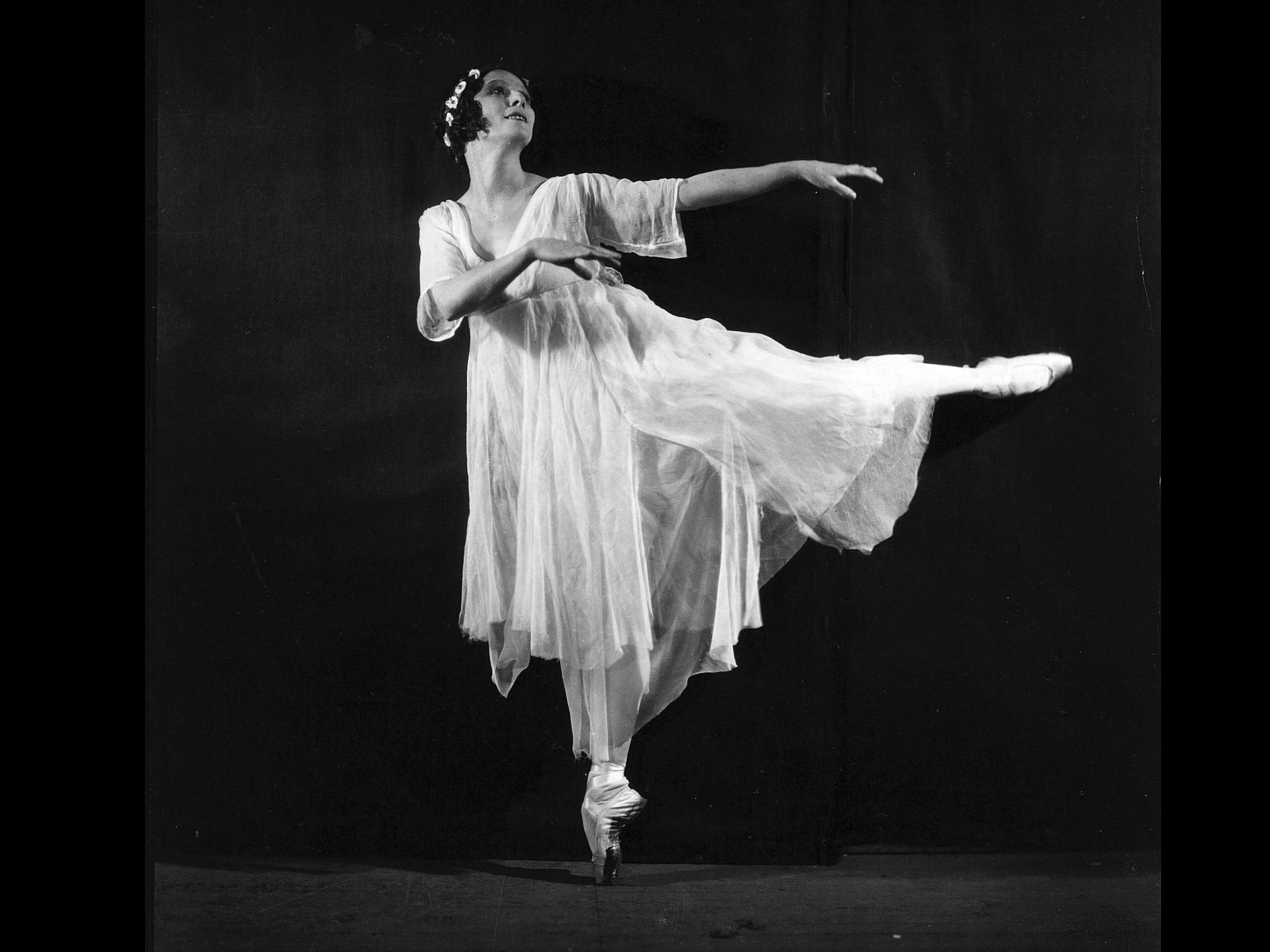

The strongest influence on ballet history was the direction of romanticism, which erupted in the late 18th century. In a romantic ballet, the female dancer first began to wear pointe shoes. Maria Taglioni was the first to do so, completely changing the previous ideas about ballet. In the ballet “Sylphide” she represented a fragile creature from the other world. The success was overwhelming.

Romanticism brought into the ballet the image of an incorporeal spirit – a ballerina who hardly touches the earth. In the same period, the roles of dancers are changing. Men turned into moving statues, which existed only to support the ballerina. Then the rising stars of female ballet completely and successfully overshadowed men.

By the way, this situation was slightly corrected by the rise of the Nijinsky star from the Russian Ballet in the early 20th century. By this time, traditional for us ballet costumes, choreography, stage sets, props had already developed, in a word, everything had become almost what it is now. Eventually, it was a Russian ballet that started the revolution in ballet art.

Over time, the peak of the popularity of romantic ballet had already passed, and Paris, as the center of classical dance, began to fade away.

Russian ballet and its influence on world classical dance

The popularity of classical dance in Europe had an impact on ballet in Russia.

The first ballet school in Russia was opened in 1738 (now the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet). At the same time, Peter I made dancing the main part of court etiquette, so the court youth was obliged to learn dancing. Thus, for example, the dance became a compulsory lesson in the Schlyakhet Cadet Corps in St. Petersburg. Since then, cadets have started to participate in ballet dances.

The dance instructor in the corps was Jean-Baptiste Lande. He understood that the nobility would not devote their lives to the art of dance. Therefore, in September 1737, Lande filed a petition in which he justified the need for a new special school where girls and boys of simple origin would be trained in choreography. Soon, such permission was given. From that moment on the training and development of dancers, for whom the ballet was a real profession, began.

At the beginning of the 19th-century Russian ballet art reached creative maturity thanks to the work of French ballet master Charles-Frederic-Louis Didlot. Didlot strengthens the role of the corps de ballet, the connection between dance and pantomime, asserts the priority of female dance. Russian dancers have brought expressiveness and sublimity to the dance.

The music of the legendary composer P. Tchaikovsky was the impetus for a new stage in the ballet history of Russia. Swan Lake, staged to Tchaikovsky’s music in 1877, gave rise to the fact that music for ballet began to be taken seriously. It was in the composer’s work that the romantic ballet became established. Tchaikovsky paid special attention to music, transforming it from an accompanying element into a powerful instrument that helps the dance to subtly capture and reveal emotions and feelings. Before that, music was considered just an accompaniment to dance.

Andrew Bossi Long CC 2.0via Wikimedia Commons

20th century

The beginning of the 20th century is characterized by an innovative search, the desire to overcome stereotypes and conventions of the academic ballet of the 19th century. One of the main innovators of this period in Russia is Sergey Diaghilev. In 1908, the annual performances of Russian ballet dancers in Paris began, organized by Diaghilev. The names of dancers from Russia became known throughout the world. But the first in this row is the name of the incomparable Anna Pavlova. Also, under his leadership in 1911, the ballet company was first organized. You can find out more about some of ballet types & styles in our related articles.

In 1929 Diaghilev died. Over time, his troupe broke up. One of its members – George Balanchine – was developing ballet in the USA and founded the New York City Ballé company. He became one of the most influential choreographers of the 20th century . In his dances, Balanchine strove for classical completeness of form, for impeccable purity of style. In many of his works, there is virtually no plot of any kind. The choreographer himself believed that the plot in the ballet is absolutely irrelevant, the main thing being the music and the movement itself. Today Balanchine’s ballets are performed in all countries of the world. He had a decisive influence on the development of twentieth-century choreography, not breaking with tradition, but boldly renewing it.

Another protege of Diaghilev, Serge Lifar , led the Paris Opera Ballet Company and for a long time was the most influential figure in French ballet.

The second half of the 20th century

In the 1950s, the dramatic ballet was in crisis. Strengthening the entertainment and pomp of performances, choreographers made futile attempts to preserve the ballet genre. Until the end of the 1950s, there was a breakthrough.

Choreographers and dancers of a new generation revived the forgotten genres – one-act ballet, ballet symphony, choreographic miniature. And since the 1970s, ballet troupes have emerged that were independent of opera and ballet theaters. Their number is constantly growing, among them, there are studios of free dance and modern dance. But today the academic ballet and the school of classical dance are still relevant.

Who were the 8 main figures who influenced the history of ballet?

Catherine Medici; Louis XIV; Jean Georges Nover; Jean Doberval; Jean-Baptiste Lande; P. Tchaikovsky; Sergey Diaghilev; George Balanchine.

What is the history of ballet?

16th century – the origin of ballet, the first ballet production. Mid 17th century – the rise of ballet dancers into amateurs and professionals. The end of 17th century – ballet is favourite form of art and accesses funding. 18th century – abandoning lavish costumes, the dance becomes freer and more professional. The start of Russian ballet. 18th - early 19th centuries – the era of romanticism in ballet, the female dancer first began to wear pointe shoes. 1877 – to the music of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake ballet was staged. 20th century - Sergei Diaghilev's ballets are becoming popular throughout the world. 1950s - the dramatic ballet was in crisis. 1970s - the rebirth of ballet as we know it today begin.

What monarch reigned during the rise of professionalism in ballet history?

Professionalism in ballet emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries. During this time, several monarchs reigned in various countries where ballet was popular, including: King Louis XIV of France, who was the patron of the Paris Opera Ballet and played a significant role in the development of ballet as a professional art form. Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, who was a patron of the Royal Ballet and supported the development of classical ballet in England. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, who was a patron of the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg and played a significant role in the development of Russian ballet. King Ludwig II of Bavaria, who was a patron of the Munich Opera Ballet and supported the development of ballet in Germany.

Related articles:

The “Arabian” Dance in The Nutcracker

Ballet foot exercises

Ballerina Feet: Ballet & Foot Health

The 9 Greatest Choreographers of the 20th century

Best dance bags

Types of ballet

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Professional Dancer, Dance coach. Favorite dance style – Pole Dance. Favorite Move – Sword Simakhina. A graduate of Saint Marys. Former Chief Editor and Owner of DanceBibles.com

- Majorette Dance: Moves, Dancing Styles and 200+ year History

- Popping: Dance with Precision. 3 beginner techniques.

- K-Pop Dance: Korea's Dancing Sensations

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The history of ballet begins around 1500 in Italy. Terms like “ballet” and “ball” stem from the Italian word “ballare,” which means “to dance.”

Ballet originated in the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century. Noblemen and women were treated to lavish events, especially wedding celebrations, where dancing and music created an elaborate spectacle. Dancing masters taught the steps to the nobility, and the court participated in the performances. In the 16th century, Catherine de Medici — an Italian noblewoman, wife of King Henry II of France and a great patron of the arts — began to fund ballet in the French court. Her elaborate festivals encouraged the growth of ballet de cour, a program that included dance, decor, costume, song, music and poetry.

At first, the dancers wore masks, layers upon layers of brocaded costuming, pantaloons, large headdresses, and ornaments. Such restrictive clothing was sumptuous to look at but difficult to move in. Dance steps were composed of small hops, slides, curtsies, promenades, and gentle turns. Dancing shoes had small heels and resembled formal dress shoes rather than any contemporary ballet shoe we might recognize today.

The official terminology and vocabulary of ballet was gradually codified in French over the next 100 years, and during the reign of Louis XIV, the king himself performed many of the popular dances of the time. Professional dancers were hired to perform at court functions after King Louis and fellow noblemen had stopped dancing.

A whole family of instruments evolved during this time as well. The court dances grew in size, opulence, and grandeur to the point where performances were presented on elevated platforms so that a greater audience could watch the increasingly pyrotechnic and elaborate spectacles.

A century later, King Louis XIV helped to popularize and standardize the art form. A passionate dancer, he performed many roles himself, including that of the Sun King in Ballet de la nuit . His love of ballet fostered its elevation from a past time for amateurs to an endeavor requiring professional training.

By 1661, a dance academy had opened in Paris, and in 1681 ballet moved from the courts to the stage. The French opera Le Triomphe de l’Amour incorporated ballet elements, creating a long-standing opera-ballet tradition in France. By the mid-1700s French ballet master Jean Georges Noverre rebelled against the artifice of opera-ballet, believing that ballet could stand on its own as an art form. His notions — that ballet should contain expressive, dramatic movement that should reveal the relationships between characters — introduced the ballet d’action , a dramatic style of ballet that conveys a narrative. Noverre’s work is considered the precursor to the narrative ballets of the 19th century.

From Italian roots, ballets in France and Russia developed their own stylistic character. By 1850 Russia had become a leading creative center of the dance world, and as ballet continued to evolve, certain new looks and theatrical illusions caught on and became quite fashionable. Dancing en pointe (on toe) became popular during the early part of the nineteenth century, with women often performing in white, bell-like skirts that ended at the calf. Pointe dancing was reserved for women only, and this exclusive taste for female dancers and characters inspired a certain type of recognizable Romantic heroine – a sylph-like fairy whose pristine goodness and purity inevitably triumphs over evil or injustice.

In the early twentieth century, the Russian theatre producer Serge Diaghilev brought together some of that country’s most talented dancers, choreographers, composers, singers, and designers to form a group called the Ballet Russes. The Ballet Russes toured Europe and America, presenting a wide variety of ballets. Here in America, ballet grew in popularity during the 1930’s when several of Diaghilev’s dancers left his company to work with and settle in the U.S. Of these, George Balanchine is one of the best known artists who firmly established ballet in America by founding the New York City Ballet. Another key figure was Adolph Bolm, the first director of San Francisco Ballet School.

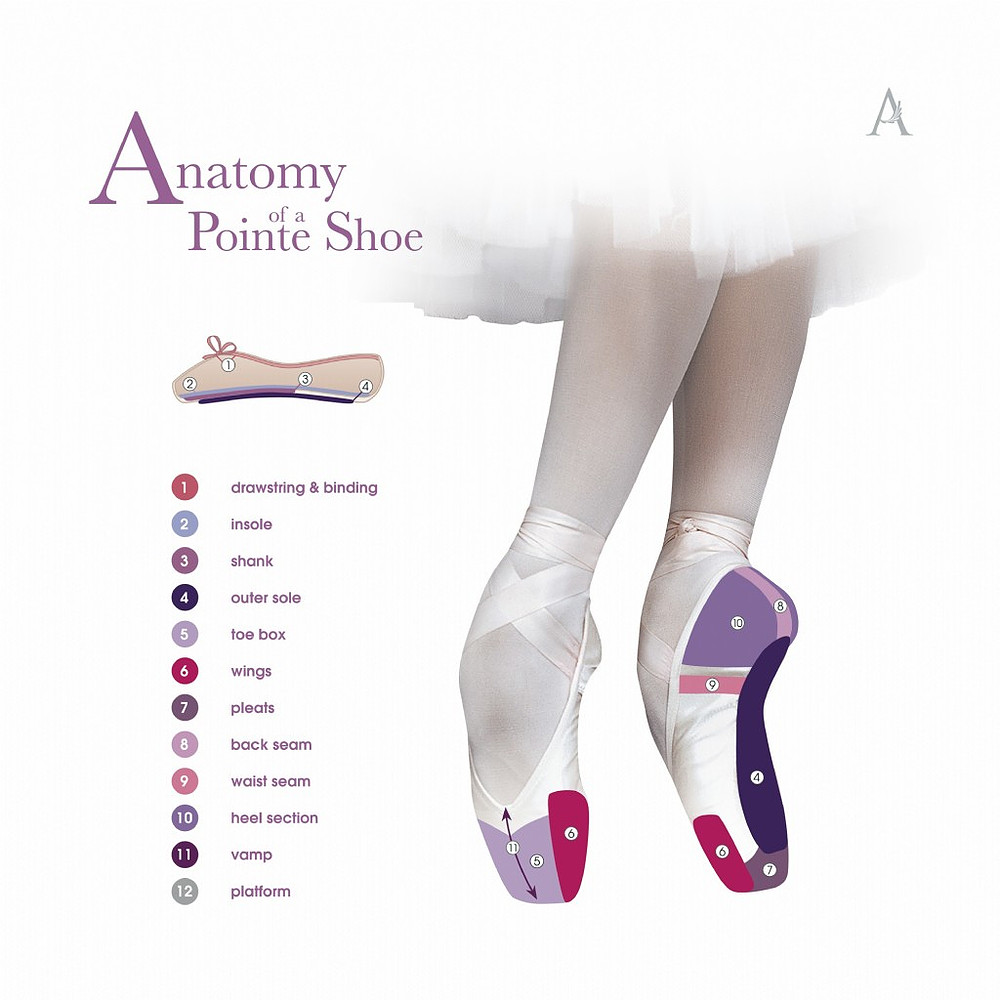

Pointe Shoes

The Pointe Shoe is synonymous with ballet and ballerina’s around the world. While we might take them for granted as having always been a part of the long history of Ballet, the pointe shoe has gone through a very long and interesting history itself. It might surprise you to learn that the art of Ballet was established 200 years before the pointe shoe was developed and dancers rose up onto the tips of their toes to dance.

The Royal Academy of Dance, Académie Royale de Danse, was the first dance institution to be founded in the western world. It was established in France in 1661 as a Theatre, Dance and Opera institution by the French king, Louis XIV. Twenty years after it was founded, the first official Ballet productions went to stage.

This academy placed Ballet within the creative arts and distinguished it as it’s own form of dance and performance. While Ballet had been practiced in Europe prior to this time, it’s official birth place in France cemented French as the international language of Ballet. Ballet classes around the world are still directed and run in French.

The first Ballet shoes worn by the dancers of the Royal Academy of Dance were heeled slippers. These shoes were quite difficult to wear and prohibited any jumps and a lot of technical movements. The heeled slipper did not stay around for very long. No one knows exactly when the heel was dropped and ballerinas wore non-heeled shoes, but the abandonment of the heel meant that the dancers could do far more than ever before. It is rumored that Marie Camargo of the Paris Opera Ballet may have been the first dancer to take the heels from the slippers.

The new flat bottomed slippers spread quickly throughout the Ballet community as dancers were liberated by the abandonment of the heel. The new flat bottomed slippers worn during the 18th century are much like the demi-pointe rehearsal and learning shoes worn by young ballerina’s in classes today. They were secured to the feet with ribbons around the ankle and were pleated under the toes for a better fit. The new slippers allowed for a full extension and enabled the dancer to use the whole foot.

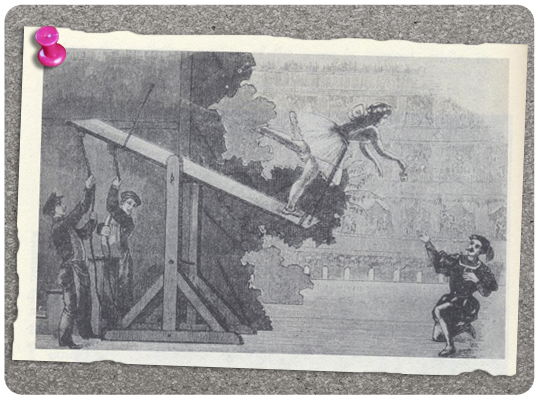

The first dancers to rise up onto their toes did so with an invention by Charles Didelot in 1795. His “flying machine” lifted dancers upward, allowing them to stand on their toes before leaving the ground. This lightness and ethereal quality was so well received by audiences and, as a result, choreographers began to look for ways to incorporate more pointe work into their pieces.

As dance progressed into the 19th century, the emphasis on technical skill increased, as did the desire to dance en pointe without the aid of wires. Marie Taglioni is often credited as being the first to dance on pointe but like many things in the early history of Ballet, no one knows for sure.

In 1832, when Marie Taglioni first danced the entire La Sylphide en pointe, her shoes were nothing more than modified satin slippers; the soles were made of leather and the sides and toes were darned to help the shoes hold their shapes. Because the shoes of this period offered no support, dancers would pad their toes for comfort and rely on the strength of their feet and ankles for support.

The next substantially different form of pointe shoe appeared in Italy in the late 18th century with a modified toe area which was the beginning stages of what we now call the toe box. Dancers like Pierina Legnani wore shoes with a sturdy, flat platform at the front end of the shoe, rather than the more sharply pointed toe of earlier models.

The Italian school could now push technique to the limit in order to achieve dazzling virtuosic feats. These more sturdy toe areas were a Ballerina’s secret weapon, a closely guarded trade secret, for turning multiple pirouettes: spotting.

These shoes went on to included a box—made of layers of fabric—for containing the toes, and a stiffer, stronger sole. They were constructed without nails and the soles were only stiffened at the toes, making them nearly silent. As the Pointe Shoe developed, so did Ballet itself. As the shoes allowed dancers to do more and more, the dancers started to want more from their shoes.

The birth of the modern pointe shoe is often attributed to the early 20th-century Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, who was one of the most famous and influential dancers of her time. Pavlova had particularly high, arched insteps, which left her vulnerable to injury when dancing en pointe. She also had slender, tapered feet, which resulted in excessive pressure on her big toes. To compensate for this, she inserted toughened leather soles into her shoes for extra support and flattened and hardened the toe area to form a box.

The soft slippers used by these ballerinas were far different from the “blocked” toe shoes that eventually appeared in their earliest form in the 1880s. (Previously, dancers also spent far less time on pointe than ballerinas do today.)

Ballet dancers in the early part of this century also wore shoes that would seem unmanageably soft today. Tamara Karsavina was said to dance in toe shoes of Swiss goatskin, while the ballerina Pierozi reportedly wore only Moroccan leather. It was fundamental to the development of Ballet technique that the pointe shoes be stiffened and stronger to support longer balances and challenging pirouettes.

Today most toe shoes are fashioned of layers of satin stiffened with glue, with a narrow sole often made of leather.

Depending on the Ballet dancers experience and skill, a pair of Pointe shoes can last between 2 to 12 hours of dancing. If a dancer is attending a one hour pointe shoe class per week; her pointe shoes will last about three months. For a professional dancer, her shoes will last far less time. A Professional Ballerina can go through 100 and 120 pointe shoes in a single dancing year. Some pointe shoes will only last a single performance in a heavy duty role where the shoes are worked hard. Ballet Companies will often employ professional pointe shoe makers and fitters to work within the company producing and buying over 8,000 shoes during the dance year.

Even different ballet role demands different strengths and flexibility in their shoes. “For the technically and physically demanding role of the Black Swan in “Swan Lake,” a strong shoe with a lot of support is required, whereas the role of the sylph in “La Sylphide” has more jumps and less pirouettes, so a light, gentle shoe is needed.”

The pointe shoe has remained very much unchanged for the last 200 years. Recent developments and changes have begun to appear now within companies that produce Ballet wear such as Nike in conjunction with Bloch Dance wear have designed these shoes called Arc Angel by Guercy Eugene. These shoes have come from a need to protect and advance the support of Ballerina’s very important asset – their feet!

Storytelling Copyright © 2021 by Pamela Bond is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Ballet — Ballet: The Art and Science of Dance

Ballet: The Art and Science of Dance

- Categories: Ballet Dance

About this sample

Words: 723 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 723 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical evolution of ballet, technical aspects and training, the impact of ballet on participants and audiences.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 600 words

1 pages / 518 words

1 pages / 413 words

2 pages / 1000 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Ballet

Ballet and traditional Zulu Indlamu dance come from vastly different origins but both are traced back to the 17th century and started from royalty. When colonisation occurred in South Africa, ballet was brought. Even though [...]

In 1913 The Rite of Spring caused a riot, it was a performance no one had ever seen before. It all began where Stravinsky created a piece of music in 1910 called the Firebird for Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes. Nikolai Roerich [...]

Every dance season has a fresh start, with that come new opportunities to set new goals, push yourself, but most importantly to be inspired by others. Recently I moved studios, and have been pushed places I never knew I could [...]

Mikhail Baryshnikov was born in Latvia in 1948. Baryshnikov was a very talented and respected ballet dancer of the Soviet Union during the late 20th century, Baryshnikov was a beloved by many in the USSR. Unfortunately, he could [...]

The soul of an artist is the passion for the art. Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky and screenplay by Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz and John McLaughlin, had opened the world of professional ballet to the silver screen. Modern [...]

A political movement is a group of people organized for the purpose of attaining a political goal or a change in society. Throughout history, political movements have driven changes in governmental policies, ruling parties, and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

History and Development of Ballet Research Paper

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Ballet appeared as a distinctive form of dance in Italy sometimes before the sixteenth century. It initially involved movements, music and special effects that were integrated together. The first dance that was performed in France was organized by Balthasar de Beaujoyeux, a violinist and it was known as The Comic Queen Ballet (Lee, 40).

This became the production of the dance, the court ballet ( ballet de cour ), and an earlier and initial version of the current / modern ballet. This production influenced a sixteenth century entertainment known as masque in an English court that was characterized by dance interludes (Lee, 91). In 1588 Orchesographie became the first piece on ballet dancing.

The major ballet dance development occurred in the 17 th century in France. During the initial stages of this development at around 1610, the divertissements scenes came into being and resulted into the grand ballet . In 1661 and 1669 the Royal Ballet Academy and the Royal Music Academy respectively were founded by Louis XIV (Lee, 66).

The Royal Music Academy later transformed into the Paris Opera to later become the foremost National Ballet School in 1672 ( Lee, 71). The performances were mainly carried out by male dancers in which the female roles were played by boys in masks and wigs (Lee, 53).

The first ballet of a kind that incorporated trained female was the 1681 Triumph of Love that involved music by Lully. During this period until 1708, ballet continued to be a court display and involved drama or opera. This was followed by the first public performance commissioning of ballet (Lee, 58).

Afterwards, ballet was infused with new ideas which saw it develop as a distinct art. However, the court ballet maintained its historic conventions. It is during these times that they saw the beginning of the choreographic notes and the legendary themes.

A ballet school based in Italy brought in great influence that resulted in more elevated movements while the horizontal movements became less. The five classic positions of a dancer’s feet were developed by Beauchamps (Lee, 75). These positions form the strength of the dancer’s movement and stance.

There was a shift from earlier cumbersome costumes to newly designed ones that allowed for greater and unrestricted movement. Some of them include slippers, short tight skirt as well as heelless shoes. This style became popular from the second century courtesy of Duncan Isadora.

It was not until 18 th century when d’action principles were brought about in the letters on ballets and dancing by ballet master (Lee, 110). His intentions were to shape ballet in such a way that it tells story with music, dance and décor as aiding tools. He wanted more of a dance, facial and body expressions.

To emphasize on naturalism, Noverre abolished the use of mask at around 1773. This was followed by other major innovations by several artists as well as technical innovation within the field of dance movement due to the continued alteration of the ballet attire (Lee, 111).

This was followed by a romantic period which formally began in 1832 after the production of La Sylphide (Lee, 135). This ushered in a new epoch that was characterized by brilliant choreography that stressed on beauty and proficiency of the prima ballerina. Ballet dance adopted filmy and calf-length costumes.

The new ballet involved the conflicts of flesh and spirit, reality and illusion. Legendary themes were put an end to and their place taken by fairy tales and love stories. During this period, a dancing style commonly referred as sur les pointes became favored by many and by the end of this century, there was the emergence of tutu, a short and buoyant skirt that ensured the legs were free. Costume sets and the choreography stopped being interesting and the imaginative feel required in ballet had been lost (Lee, 151).

The modern ballet period followed. This has seen major development in countries such as Russia, Britain and the USA. The Russian ballet has greatly developed with figures such as Sergei Diaghilev being hailed for their contribution. Russian dancing has for some time now been to its highest level and boasts several top ballet companies (Lee, 301).

The British ballet has not been left behind and the period between 1918 and present day has witnessed several transformations (Lee, 278). In 1930, Ballet Club was founded while the now famous Royal Ballet was established a year later. Through Royal Ballet’s efforts, the world is slowly giving male dancers an added colorful showcase (Lee, 278).

In the USA, the American Ballet company was founded in 1934 which was followed by a first major school that helped to develop the talents of several famous American dancers (Lee, 312). Several companies have since then been created and via formal training and movement, choreographers from US have come up with new style of ballet that depends less on literary plot but more on electronic and modern rock music. The costuming and décor has been greatly simplified.

Works Cited

Lee, Carol Ballet in Western Culture: A History of Its Origins and Evolution. London: Rutledge, 2002.

- What Is Dance: Definition and Genres

- Dance Analysis: Social and Cultural Context

- “Degas at the Opéra” Art Exhibition

- Dance and Architecture in "Ballet Pas de Deux" Exhibition

- “The Dance Class” Painting by Edgar Degas

- Capoeira Dance History and Popularity

- Alvin Ailey - an Activist and American Choreographer

- Similarities between Ballet and Hip Hop

- Hip Hop Dancing: The Remarkable Black Beat

- Modern Dance by Jiri Kylian

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 6). History and Development of Ballet. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-and-development-of-ballet/

"History and Development of Ballet." IvyPanda , 6 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/history-and-development-of-ballet/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'History and Development of Ballet'. 6 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "History and Development of Ballet." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-and-development-of-ballet/.

1. IvyPanda . "History and Development of Ballet." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-and-development-of-ballet/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "History and Development of Ballet." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-and-development-of-ballet/.

The History and Evolution of Ballet

Mairead Kennedy

Prof. Ishiguro

Dance as Cultural Knowledge

12 December 2020

Ballet is a style of dance that is so commonly practiced today, however most people are unaware of its origins and its development overtime. In particular, the racial aspects of this dance are rarely discussed, despite how important they really are. Ballet started off as a dance that was extremely exclusive, and went through a lot to become more inclusive. The word ballet originated from the Italian word ballare, which translates to the verb dance in the english language. This is to show that the first ballet dance must have come from Italy. Despite the origin of the word, this dance style has been carried out to take over in many countries. Specifically in France, ballet became popular through the royal court under the rule of both King Henry II and Louis XIV. It was regarded as a dance made for highly respected individuals. Although there was a time when ballet was not allowed in the French court, it still found a way to disperse throughout the world with the help of education and the prominence of dance academies. Now that ballet has a place in various cultures, the difference in the bodies of people who perform this style of dance has made an impact on what the dance itself looks like. Ballet eventually made its way into Harlem, a neighborhood in New York City. This is an area that is recognized as a center for African American culture. Because of the origins of this dance and the meanings behind it, the concept of African Americans taking part seemed quite contradictory. Ballet was tied to ideas of superiority and the distinguishing of aristocracy from other social classes. During the time when the Dance Theatre of Harlem was opening, classical ballet, amongst many other activities, was not at all racially integrated. Ballet was known for exclusivity, which was something that black community in the United States was fighting against. However, the meaning behind this new dance company was to create a space for all people to have the opportunity to take part in the practice of ballet.

When King Henry II married Catherine de Medici, who was from Italy, she introduced ballet to the royal court in France. She was very fond of the dance, so she funded the court performances herself. At this point in time, ballet was not known across the world. This was still a dance that was only practiced by people who had money or were born into royalty. Eventually, the dance became more popular and was performed on stage, rather than just in the royal court. This was a step in the right direction for opening up opportunities for dancers. These stage performances made it much easier for the dance to gain popularity because it was more accessible to the common people. The more that people were exposed to ballet, the more likely it was to be brought to a new area in the world. Later on, when Louis XIV had control over the royal court, it was said that he was a part of bringing the dance into French culture. He was a performer himself, and actually longed to become a professional dancer of this style. It is even explained that “ballet as we know it today began at the precise moment when the Sun King arose, stepped down from his throne, and danced” (Shook 11). This gives some insight into just how important ballet was during this time period. Unfortunately, when Louis XIV was too old to continue his practice, ballet was then banned from the royal court. From this point on, it was up to the dance academies in Europe to pass along the dance style to the rest of the world. Ballet made its way to the United States long after these performances took place in the royal courts of France. This would be where the dance was changed into a more modern style, through the various inputs of different cultures.

The basic movements of ballet have been mostly stable throughout its evolution, yet there are aspects that have changed drastically over the years. It is important to understand that, “Classical ballet, like everything else in the human condition, evolves, and, as it evolves, mutates” (Shook 10). There was no chance that this dance form would stay stagnant in every respect, considering the extent to which is migrated around the globe. An important aspect to analyze would be the costume that the dancers wear during performance. Pointe shoes are now recognized as a part of ballet that distinguished it from all other dance styles. However, it is shocking to find that these shoes were not always worn during performances. Interestingly enough, early on in the development of the dance, ballerinas would actually wear heeled shoes when they performed. Overtime, it became really important for a dancer to show an emphasis of elevation and extension of their legs. This eventually led to the innovation of ballet shoes. At first, “Italian shoemakers developed reinforced pointe shoes with stiff boxes made from newspaper, flour paste and pasteboard” ( Guiheen 2020). This explains that the development of pointe shoes started off as just an idea that was attempted in a simple way. The innovation took a long time to make its way to the pointe shoes that are worn today. It was not until long after that the shoes became a necessary part of the dance itself. This goes to show that the dance was constantly changing to become what it is today. Whether it is in the costume of the dance or the opportunities that the dance presents, it is clear that ballet evolved for a long time with the help of the influence from countries across the world.

Another aspect that continued to change was the movement of the dancers’ bodies. At first, this style was only ever performed by white aristocrats in the royal court. It is easy to imply that these dancers all had similar body shapes and similar ways of moving. Dancers of the same race will tend to have similar anatomy. This is where the concept of the importance of integration of different races and cultures into ballet comes into play. For example, “an arabesque , while remaining just what it is, will look one way on a Russian body, different on an oriental body, or on the black bodies of the dancers of Dance Theatre of Harlem” (Shook 10). The meaning behind this quote is that all dancers will look different depending on the way that their body is shaped, and this tends to correlate with race and cultural origins. The important part to understand is that this should not determine whether or not a dancer is good at a certain dance. It may look different, but skill cannot be determined by the physical makeup of a body. Nowadays, this is likely an idea that most people do not regularly think about. This is because dance is now much more open to allowing all types of people to contribute their practice. However, it is important to realize that discrimination was extremely common in the world of dance, and this was not long ago. The 1900s in the United States was a place that experienced a large amount of racial division. There was “little opportunity for dancers of color to study and flourish in classical ballet”, because this was a dance style that was not open to them at the time (Djassi DaCosta Johnson). It is necessary to realize that without the input of African American dancers into the world of ballet, the dance would not be the same as it is to this day. Although the movements might appear differently when done by different groups of people, it is still ballet, and that is what now makes the dance so beautiful. For this reason, it can be understood that race should not determine whether or not one can be a skilled ballet dancer, or dancer of any style.

There were moments throughout the history of America that altered how society viewed dancers based off of the color of their skin. When looking at dance during the time of Civil Rights Movements, it is clear that there was discrimination specifically against black dancers. When the Dance Theatre of Harlem was founded in 1969 by Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook, it became a place for all people to experience ballet, despite what they looked like or where they came from. The opening of the theatre was supposedly influenced by the death of Martin Luther King Jr.. During this time, Harlem was filled with violence and civil unrest due to the racism and social divide in the area. This area was not a safe place to be living, especially as a young person being surrounded by violence. Therefore, the Dance Theatre of Harlem was the perfect respite for all people to join and practice dance safely. In regards to Arthur Mitchell, it is noted that, “At the height of the civil rights movement, in a graceful moment of artistic resistance, he created a haven for dancers of all colors who craved training, performance experience and an opportunity to excel in the classical ballet world” (DaCosta Johnson 2020). The importance of this can be understood through just how beneficial it was to the community of Harlem, along with all colored dancers across the country. The development of the theatre was a brilliant idea that opened up a way to break down the segregation of race in the dance world.

Ballet was originally created as a dance to be done by the wealthy and respected people of the royal courts in Italy and France. As the dance was brought around the world, it picked up influences from a variety of cultures. In France, the dance was developed to become more popular outside of the royal courts. In Italy, pointe shoes were created which are now a large part of what makes ballet so unique. As ballet was practiced, there was more and more exposure that led to the dance being practiced across the entire world. Along the way, input from different cultures changed certain aspects of the dance. These influences led to changes in the way that the dancers dressed and moved. Movements became more about skill and less about similarity, as the bodies of the dancers were different in all parts of the world. It was understood that ballet was much more versatile than it was first set out to be. With the creation of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, classical ballet was able to be performed by all people. Opening up a place for all people, specifically black Americans in Harlem, to practice ballet was likely the most important development in ballet when discussing the equality of dancers. This was a huge step forward into ensuring that the color of one’s skin should not hinder opportunities in the dance world.

Works Cited

Djassi DaCosta Johnson, Djassi. “Our History.” Dance Theatre of Harlem , 2020, www.dancetheatreofharlem.org/our-history/.

Guiheen, Julia. The History of Pointe Shoes: The Landmark Moments That Made Ballet’s Signature Shoe What It Is Today . 11 Aug. 2020, www.pointemagazine.com/history-of-pointe-shoes-2646384074.html.

Shook, Karel. Elements of Classical Ballet Technique: As Practiced in the School of the Dance Theatre of Harlem . Dance Books, 1978.

Written by Mairead Kennedy

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- 1000- words essay #2

- 1000-words essay #1 : A letter to future self

- 1000-words essay #3

- 1000-words essay #4

- Final Project Paper

- Share your music + doodle

- Uncategorized

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Portrait of a Woman, Said to be Madame Charles Simon Favart (Marie Justine Benoîte Duronceray, 1727–1772)

François Hubert Drouais

The Ballet from "Robert le Diable"

Edgar Degas

Louis Gueymard (1822–1880) as Robert le Diable

Gustave Courbet

Bacchante with lowered eyes

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Marcantonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) Crowned by Apollo

Andrea Sacchi

Head of Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830–1914)

Edouard Manet

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2004

Opera, whose name comes from the Italian word for a work, realizes the Baroque ambition of integrating all the arts. Music and drama are the fundamental ingredients, as are the arts of staging and costume design; opera is therefore a visual as well as an audible art. Throughout its history, opera has reflected trends current in the several arts of which it is composed. Developments in architecture and painting have manifested themselves on the operatic stage in the design of sets and costumes for specific performances, and opera has also affected the visual arts beyond the stage in such domains as the design and decoration of opera houses and the portraiture of singers and composers. A feature unique to opera, however, is the power of music, particularly that written for the several registers of the human singing voice, which is arguably the artistic means best suited to the expression of emotion and the portrayal of character.

From the Court to the Public Theater In its origins, opera, like every other type of spectacle, expressed noble prerogatives and was staged in courtly settings. In seventeenth-century Italy, the birthplace of the form, lavish entertainments featuring fireworks and sensational effects as well as instrumental music, singing, dances, and speeches were staged to celebrate princely weddings or to welcome regal guests. Although not operas in the modern sense, these integrated entertainments fostered collaboration among the arts and prompted the theoretical justifications upon which true opera—and ballet , whose early development runs parallel—was built. The Florentine Camerata, a group of composers and dramatists active in Florence around 1600, set out to revive the great traditions of the classical Greek stage , in which music and drama reinforced each other. Toward this end, they developed recitative, a type of sung speech featuring the solo voice and an unadorned vocal line expressive of the text. Early operas, largely based on mythological themes and peopled with noble characters, promoted aristocratic ideals.

Although music and drama were the essential features of opera, visual effects often dominated the court productions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the designers of sets and theatrical machinery sometimes received greater acclaim than the composers who wrote the music. The audiences for court performances were part of the spectacle, since the convention of darkening the theater did not yet exist. Magnificently garbed and seated in orderly ranks, the spectators followed the action of the opera, which might last several hours, in a printed libretto, literally “a little book” produced for the occasion. Today the word libretto denotes the text of the opera, the drama that is set to music, but in the days of court opera, librettos were attractively illustrated and therefore involved the talents of draftsmen and engravers , who were also engaged to commemorate the festivities.

Although the spectacular emphasis of court performances continued as opera evolved, musical considerations guided its evolution. It was early noticed that music could express mood, define character, and enliven dramatic situations, sometimes more eloquently than verbal expression alone. Arias for solo voice might express a sentiment both musically and verbally; ensembles, choruses, and orchestral interludes likewise produced effective color. Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), who used recitative as well as lyrical solos, madrigals, and instrumental color in operas on a variety of classical themes, is considered the first genius of operatic composition, and his “favola in musica” Orfeo (1607) is often seen as the first true opera. Although Monteverdi spent the early part of his career writing for the dukes of Mantua, his last works were intended for the public opera houses of Venice, the first of which opened in 1637. The public became and still remains the primary audience for the opera, although court productions continued to be devised wherever courts existed.

Opera in the Age of Enlightenment By the end of the eighteenth century, opera was an international phenomenon, and both comic and serious genres flourished in France, England, and the Habsburg empire as well as in Italy, although Italian remained the standard language of the libretto. Decorative objects of the period suggest the popularity of opera outside a court context ( 17.190.1867 ). Painters, such as François Boucher and Antoine Watteau , continued to devise set designs, but focus shifted to the quality of the music, which rose very high. Under composers such as Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) and Georg Frideric Handel (1685–1759), the orchestra expanded to include woodwind instruments, horns, and drums in addition to the original strings . The castrato soprano voice was frequently given the hero’s part, and castrati were among the greatest stars of the period. The magnificently ornamented music written for such virtuoso singers thrilled audiences but also diminished the dramatic element of opera and provoked calls for reform. These were answered by Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714–1787), whose Orfeo ed Euridice of 1762 recasts the time-honored operatic story of the artist whose song can thwart death itself.

The reinvigoration of opera at the end of the eighteenth century was assured by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), whose music for voices and orchestra is alive with dramatic purpose. In The Marriage of Figaro (1786), for example, exquisite melodies describe and enrich the personalities of the clever servant Figaro, his vivacious fiancée Susanna, the lovelorn Countess, the philandering Count, and the eager teenager Cherubino. The extremely effective libretto for this opera, written by Lorenzo Da Ponte (1749–1838), was based on a contemporary French play by Beaumarchais. Don Giovanni (1787), another collaboration between Mozart and Da Ponte, presents the last days of an unrepentant seducer and culminates in two unforgettable scenes in which the statue of a man whom he has murdered accepts an invitation to dinner and arrives to escort him to hell. Mozart’s last opera, a German comedy called The Magic Flute (1791), takes place in fantastic settings that still inspire experiments in set and costume design; two recent productions at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, for instance, were devised by the artists Marc Chagall and David Hockney.

The Flourishing of Opera in the Nineteenth Century In the nineteenth century, conditions were ripe for broadening the audience for opera and for changes in the form itself. Bourgeois taste displaced court concerns in the selection of dramatic subjects, while composers, singers, and theater impresarios vied for popular success. In France and Italy, broad cultural movements like Romanticism , Orientalism , and Realism manifested themselves in opera as in the visual arts, while the rise of nationalism produced vigorous new operatic traditions in Germany and Russia.

The Romantic movement of the early nineteenth century launched a burst of interest in the irrational, the otherworldly, the exotic, and the historical, all subjects admirably suited to operatic portrayal. For instance, Gaetano Donizetti’s (1797–1848) Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), based on a novel by Sir Walter Scott, includes such themes as ancestral enmity, star-crossed love, and the tragic death of the heroine—which, in this case, is preceded by a vocally demanding expression of madness. Similar concerns were paramount in the contemporary French opera, whose leading composer was the German-born Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791–1864). His Robert le Diable (1831), like the several other successful works that he created for the Paris Opéra, was staged with lavish effects, spectacular sets, choreographed dances, and huge onstage ensembles, that is, with all the hallmarks of French grand opera ( 29.100.552 ). The devil himself is a primary character in another example of the genre, Faust (1859), written by Charles Gounod (1818–1893). Because nineteenth-century operas were often based on earlier stage plays or literary works, Romantic subject matter prevailed in opera long after writers and painters had turned to other concerns. Georges Bizet (1838–1875), for example, based his Carmen (1875) on an early nineteenth-century novella by Prosper Mérimée and, like its source, the opera is full of the Spanish flavor that so appealed to French nineteenth-century audiences. The passion, violence, and impropriety so prominently featured in opera ran contrary to the ideals of contemporary bourgeois society, and artists’ portrayals of spectators, particularly women, watching from the privacy of their boxes suggest the constraints placed upon them as well as the attraction of opera’s cathartic subject matter.

High tragedy dominates the operas composed by Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901), whose feeling for drama helped him produce wonderfully expressive music for chorus, ensembles, solo voices, and the orchestra. His first public success came with Nabucco (1842), in which a stirring chorus expresses the longing of captives for their homeland. The plots of Verdi’s operas involve moral conflict and powerful emotions: Rigoletto (1851) presents a court jester whose desire for revenge inadvertently leads to his own daughter’s death; Aida (1871) tells the story of an Ethiopian princess in love with an Egyptian general who represents her country’s enemy; Otello (1887), adapted from Shakespeare , concerns the hero’s fatal jealousy, which results in his undoing and the murder of his wife. Verdi’s operas are full of memorable scenarios, and the exotic settings invite set designers to explore the whole history of art. On stage, the triumphal parade in Aida can evoke the grandeur of pharaonic Egypt , and the arrival of the ambassadors in Otello may resemble a Venetian painting brought to life.

Verdi’s contemporary Richard Wagner (1813–1883) took a completely different approach to opera. His ideal was the Gesamtkunstwerk , or total work of art, in which drama, staging, and music would forge a powerful unity. Wagner realized these aims by controlling every aspect of his works, writing his own librettos and supervising set design as well as composing the music. In many ways, Wagner magnified the opera beyond any proportions it had attained before. He scored his works for a large orchestra, requiring herculean voices to complement it, and he raised in his dramas such profound themes as redemption through love and the rapport between humanity and the divine. His largest project, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1853–74), is a sweeping drama in four parts, each one longer than a standard Italian opera. The story of the Ring , based on Germanic mythology, presents many opportunities for visual spectacle, among them the Rhine Maidens swimming under water, the Valkyries riding in on winged horses, Siegfried’s combat with the dragon Fafner, Brünhilde asleep in the midst of magic flames, and the fall of Valhalla itself. Frustrated with the physical limitations of contemporary theaters, Wagner found the means to build a new house to his own specifications at Bayreuth in Bavaria, and here he departed from established convention by darkening the auditorium during performances and covering the orchestra pit so as to focus all attention on the stage.

The culmination of Wagner’s career in Germany coincided with the building of a new opera house in Paris, designed by Charles Garnier and opened in 1875. The prominent position of the Opéra within the new system of boulevards devised by Baron Haussmann during the Second Empire demonstrates the social importance of opera at the time, while the lavish ornament of the building makes it seem at once a temple and a palace. Among the artists involved in decorating the Opéra were Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, who designed bronze figures carrying candelabra for the grand staircase, and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux , who contributed an animated marble group for the facade ( 11.10 ).

By the late nineteenth century, opera was viewed as the ultimate art form, suitable for portraying the grandest aspirations not only of heroic men and women but also of peoples and nations. The celebrated Russian opera Boris Godunov (1874), written by Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881), dramatizes a stormy period in Russian history and gives special emphasis to the chorus of common people that crowd around the glittering world of the czar. Although Catherine the Great promoted Italian opera and even wrote some of her own librettos, Russian opera was largely an invention of the nineteenth century, a sign of social ferment as well as rising nationalism. The vigorous Russian literature of the period furnished rich material for such operas as Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s (1840–1893) Eugene Onegin (1879), based (like Boris Godunov ) on a work by Aleksandr Pushkin. Sergei Prokofiev’s (1891–1953) War and Peace and The Gambler were based on works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, respectively.

Although the great operatic composers devoted much of their attention to subjects tragic, awesome, or macabre, they also produced comic operas that are still staged and loved. Mozart’s operas contain much that is humorous, both musically and visually. Verdi scored a colossal failure with an early comic opera but ended his career with Falstaff (1893), based on the antics of the jolly Shakespearean knight. The comic operas of Gioacchino Rossini (1792–1868), such as The Barber of Seville (1816), are rife with tunes that brilliantly express fast-paced intrigue in hilarious situations. Even Wagner composed one masterpiece, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868), with a happy ending and a number of comic features. The setting is sixteenth-century Nuremberg, and the action revolves around a group of craftsmen-singers, foremost among them the shoemaker-poet Hans Sachs. The discussion of art that runs throughout the opera applies specifically to music but may also be extended to other genres; the artist Albrecht Dürer , presumably alive among the characters, is mentioned in the opera.