St. John's College

St. John’s Reading List: A Great Books Curriculum

St. John’s College is best known for its reading list and the Great Books curriculum that was adopted in 1937. While the list of books has evolved over the last century, the tradition of all students reading foundational texts of Western civilization remains. The reading list at St. John’s includes classic works in philosophy, literature, political science, psychology, history, religion, economics, math, chemistry, physics, biology, astronomy, music, language, and more. Learn more about classes at St. John’s and the subjects students study .

The reading list presented on this page may not accurately reflect the current reading list due to recent changes, works that are read only on one campus, works that are read in part, and works that are read by some students as junior and senior elective classes.

Agamemnon , Libation Bearers , Eumenides , Prometheus Bound

“On the Equilibrium of Planes,” “On Floating Bodies”

Aristophanes

Poetics , Physics , Metaphysics , Nicomachean Ethics , On Generation and Corruption , Politics , Parts of Animals , Generation of Animals

Amedeo Avogadro

“Essay on a Manner of Determining the Relative Masses of the Elementary Molecules of Bodies”

Claude Berthollet

“Excerpt from Essai de Statique Chimique”

Joseph Black

“Extracts from Lectures on the Elements of Chemistry”

Stanislao Cannizzaro

“Letter to Professor S. De Luca”

John Dalton

“Extracts from A New System of Chemical Philosophy”

Hans Driesch

“The Science and Philosophy of the Organism”

Hippolytus , Bacchae

Daniel Fahrenheit

“The Fahrenheit Scale”

Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac

“On the Expansion of Gases by Heat,” “Memoir on the Combination of Gaseous Substances with Each Other”

William Harvey

On The Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals

Iliad , Odyssey

Antoine Lavoisier

Elements of Chemistry

On the Nature of Things

Edme Mariotte

Dmitri mendeleev.

“The Periodic Law of the Chemical Elements”

Blaise Pascal

Treatise on the Equilibrium of Liquids

Meno , Gorgias , Republic , Apology , Crito , Phaedo , Symposium , Parmenides , Theaetetus , Sophist , Timaeus , Phaedrus

“Lycurgus,” “Solon”

J.L. Proust

“Excerpt from Sur Les Oxidations Metalliques”

Poems 1 and 31

Oedipus Rex , Oedipus at Colonus , Antigone, Philoctetes , Ajax

Hans Spemann

“The Organizer-Effect in Embryonic Development” (Nobel Lecture 1935), “Embryonic Development and Induction”

J.J. Thomson

“Extracts from System of Chemistry”

The History of the Peloponnesian War

Rudolf Virchow

“Cellular Pathology Lectures”

Virginia Woolf

On Not Knowing Greek

Hebrew Bible

New testament, dante alighieri.

Divine Comedy

Thomas Aquinas

Summa Theologiae

De Anima , On Interpretation , Prior Analytics , Categories

Confessions

Johann Sebastian Bach

St. Matthew Passion , Inventions

Francis Bacon

Novum Organum

“The Disappointment”

Anne Bradstreet

Geoffrey chaucer.

Canterbury Tales

Nicolaus Copernicus

On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Missa Papae Marcelli

Michel de Montaigne

René descartes.

Geometry , Discourse on Method

Princess Elisabeth

The Correspondence Between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes

Discourses, Manual

Joseph Haydn

Johannes kepler.

Astronomia Nova

Early History of Rome

Niccolò Machiavelli

The Prince , Discourses

Guide for the Perplexed

Andrew Marvell

Claudio monteverdi.

L’Orfeo

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Albert murray.

Stomping the Blues

Generation of Conic Sections

The Enneads

“Caesar,” “Cato the Younger,” “Antony,” “Brutus”

Franz Schubert

William shakespeare.

Richard II , Henry IV , The Tempest , As You Like It , Hamlet , Othello , Macbeth , King Lear , and Sonnets

Igor Stravinsky

Symphony of Psalms

Ludwig van Beethoven

Third Symphony

François Viète

Introduction to the Analytical Art

Lady Mary Wroth

“A Crown of Sonnets Dedicated to Love”

United States Historical Documents

Articles of Confederation, Declaration of Independence, Constitution of the United States of America

André-Marie Ampère

Jane austen.

Pride and Prejudice , Emma

Daniel Bernoulli

“On the Vibrating String”

Miguel de Cervantes

Don Quixote

Charles-Augustin de Coulomb

“Excerpts from Coulomb’s Mémoires sur l’électricité et le magnétisme”

Madame de La Fayette

Princess of Clèves

Jean de La Fontaine

François de la rochefoucauld, richard dedekind.

Essays on the Theory of Numbers

Meditations , Rules for the Direction of the Mind

George Eliot

Middlemarch

Leonhard Euler

“Remarks on the Preceding Papers by Mr. Bernoulli”

Michael Faraday

“Experimental Researches in Electricity”

Benjamin Franklin

“Excerpt from several letters to Peter Collinson on the nature of electricity”

Galileo Galilei

Two New Sciences

William Gilbert

“De Magnete”

Hamilton, Jay, and Madison

The Federalist

Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Scarlet Letter

Thomas Hobbes

Treatise of Human Nature

Christiaan Huygens

Treatise on Light , On the Movement of Bodies by Impact

Immanuel Kant

Critique of Pure Reason , Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Monadology , Discourse on Metaphysics , Essay on Dynamics, Philosophical Essays, Principles of Nature and Grace

Second Treatise of Government

James Clerk Maxwell

“On Faraday’s Lines of Force,” “On Physical Lines of Force,” “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field”

John Milton

Paradise Lost

Le Misanthrope

Don Giovanni

The Marriage of Figaro

Isaac Newton

Principia Mathematica

Jean-Antoine Nollet

“Observations on Several New Electrical Phenomena”

Hans Christian Ørsted

“Experiments concerning the efficacy of electric conflict on the magnetic needle”

Pensées

Jean Racine

Phèdre

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Social Contract , The Origin of Inequality

Wealth of Nations

Baruch Spinoza

Theologico-Political Treatise , Ethics

Jonathan Swift

Gulliver’s Travels

Brook Taylor

“On the motion of the stretched string”

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Alessandro Volta

“On the Electricity excited by the mere contact of conducting substances of different kinds”

William Wordsworth

The Two-Part Prelude of 1799

Richard Wagner

Tristan and Isolde

Thomas Young

“On the Nature of Light and Colors”

Hannah Arendt

The Human Condition

Samuel Beckett

Waiting for Godot

The Bhagavad Gita

Albert camus.

The Stranger

Madame de Sévigne

Fyodor dostoevsky, marcel duchamp, ralph ellison.

Invisible Man

Alcestis ; Medea ; Hecuba ; The Trojan Women

Richard Feynman

Gustave flaubert.

Madame Bovary

Michel Foucault

Discipline and Punish ; Security, Territory, and Population

Gabriel García Márquez

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Edward Gibbon

History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

G. H. Hardy

A Course of Pure Mathematics

Georg Hegel

Philosophy of Nature , Elements of Philosophy of Right

Martin Heidegger

What is Metaphysics?

Alfred Hitchcock

Selected movies

Henry James

The Portrait of a Lady

James Joyce

Soren kierkegaard.

Dao De Jing

Halldór Laxness

Independent People

Emmanuel Levinas

Totality and Infinity

Konrad Lorenz

Studies in Animal and Human Behavior

Jorge Luis Borges

Édouard manet, herman melville, arthur miller.

Death of a Salesman

Toni Morrison

Friedrich nietzsche.

Gay Science

Flannery O’Connor

Thomas piketty, marcel proust.

Swann’s Way , Remembrance of Things Past

Ranier Maria Rilke

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge

The Rise and Decline of the Roman Republic

Bertrand russell.

An Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy

Measure for Measure

Oswald Spengler

The Decline of the West

Eudora Welty

Short stories

Tennesee Williams

A Streetcar Named Desire

The Works of Zhuangzi

Finnegans Wake

Kate Chopin

The Awakening

Zora Neale Hurston

Their Eyes Were Watching God

V.S. Naipaul

A House for Mr. Biswas

William Gaddis

The Recognitions

Neuroscience

United states supreme court decisions, james baldwin.

Stranger in the Village, The Fire Next Time

Charles Baudelaire

Les Fleurs du Mal

George Beadle & Edward Tatum

Elizabeth bishop.

“On the Spectrum of Hydrogen”

Theodor Boveri

Gwendolyn brooks.

Sonnets from Children of the Poor

Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness

Charles Darwin

Origin of Species

Clinton Davisson

Simone de beauvoir.

The Second Sex

Louis de Broglie

“Matter Waves”

Alexis de Tocqueville

Democracy in America

Emily Dickinson

Brothers Karamazov

Frederick Douglass

Selected speeches

W. E. B. Du Bois

The Souls of Black Folk

Albert Einstein

“Relativity,” “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies,” “On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light,” “The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity,” “Does the Inertia of a Body Depend upon its Energy Content?”

T. S. Eliot

“On the Absolute Quantity of Electricity Associated with the Particles or Atoms of Matter”

William Faulkner

Go Down, Moses

Un Coeur Simple

Sigmund Freud

Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis , Mourning and Melancholia , Beyond the Pleasure Principle

The Federalist Papers

“Mendelian Proportions in a Mixed Population”

Phenomenology of Mind

Basic Writings , The Word of Nietzsche: God is Dead , Introduction to Metaphysics

Werner Karl Heisenberg

“Critique of the Physical Concepts of the Particle Picture”

Edmund Husserl

The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology

François Jacob & Jacques Monod

Søren kierkegaard.

Philosophical Fragments , Fear and Trembling

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

“Zoological Philosophy”

Abraham Lincoln

Nikolai lobachevsky.

Theory of Parallels

Capital , The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 , The German Ideology

Benito Cereno

Gregor Mendel

“Experiments with Plant Hybridization”

Hermann Minkowski

“Space and Time”

Robert Andrews Millikan

“The Electron”

Thomas Morgan

Evolution and Genetics , “The Chromosomes and Mendel’s Two Laws,” “The Linkage Groups and the Chromosomes,” “Sex-Linked Inheritance,” “Crossing-Over”

Song of Solomon

Beyond Good and Evil

Good Country People, Revelation, The Displaced Person

Sylvia Plath

“The Quantum Hypothesis”

Arthur Rimbaud

Ernest rutherford.

“The Scattering of α & β Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom”

Erwin Schrödinger

“Four Lectures of Wave Mechanics—First Lecture”

Wallace Stevens

Joel sussman, walter sutton, j. j. thomson.

“Cathode Rays”

Leo Tolstoy

War and Peace

Paul Valéry

Johann wolfgang von goethe, booker t. washington.

“Atlanta Exposition Address,” “Our New Citizen,” “Democracy and Education”

Mrs. Dalloway , To the Lighthouse, A Room of One’s Own

James Watson & Francis Crick

William butler yeats.

The Human Condition , The Origins of Totalitarianism

Madame de Sévigné

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Remembrance of Things Past

The Decline of the West

School's out

A critical take on education and schooling

The 50 great books on education

Professor of Education, University of Derby

View all partners

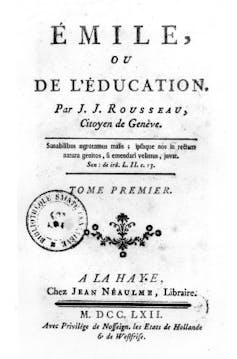

I have often argued that I would not let any teacher into a school unless – as a minimum – they had read, carefully and well, the three great books on education: Plato’s Republic, Rousseau’s Émile and Dewey’s Democracy and Education. There would be no instrumental purpose in this, but the struggle to understand these books and the thinking involved in understanding them would change teachers and ultimately teaching.

These are the three great books because each is sociologically whole. They each present a description and arguments for an education for a particular and better society. You do not have to agree with these authors. Plato’s tripartite education for a just society ruled over by philosopher kings; Rousseau’s education through nature to establish the social contract and Dewey’s relevant, problem-solving democratic education for a democratic society can all be criticised. That is not the point. The point is to understand these great works. They constitute the intellectual background to any informed discussion of education.

What of more modern works? I used to recommend the “blistering indictment” of the flight from traditional liberal education that is Melanie Phillips’s All Must Have Prizes, to be read alongside Tom Bentley’s Learning Beyond the Classroom: Education for a Changing World, which is a defence of a wider view of learning for the “learning age”. These two books defined the debate in the 1990s between traditional education by authoritative teachers and its rejection in favour of a new learning in partnership with students.

Much time and money is spent on teacher training and continuing professional development and much of it is wasted. A cheaper and better way of giving student teachers and in-service teachers an understanding of education would be to get them to read the 50 great works on education.

The books I have identified, with the help of members of the Institute of Ideas’ Education Forum, teachers and colleagues at several universities, constitute an attempt at an education “canon”.

What are “out” of my list are textbooks and guides to classroom practice. What are also “out” are novels and plays. But there are some great literary works that should be read by every teacher: Charles Dicken’s Hard Times – for Gradgrind’s now much-needed celebration of facts; D. H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow – for Ursula Brangwen’s struggle against her early child-centred idealism in the reality of St Philips School; and Alan Bennett’s The History Boys – for Hector’s role as the subversive teacher committed to knowledge.

I hope I have produced a list of books, displayed here in alphabetical order, that are held to be important by today’s teachers. I make no apology for including the book I wrote with Kathryn Ecclestone, The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education because it is an influential critical work that has produced considerable controversy. If you disagree with this, or any other of my choices, please add your alternative “canonical” books on education.

Michael W. Apple – Official Knowledge: Democratic Education in a Conservative Age (1993)

Hannah Arendt – Between Past and Future (1961), for the essay “The Crisis in Education” (1958)

Matthew Arnold – Culture and Anarchy (1867-9)

Robin Barrow – Giving Teaching Back to the Teachers (1984)

Tom Bentley – Learning Beyond The Classroom: Education for a Changing World (1998)

Allan Bloom – The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students (1987)

Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron – Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture (1977)

Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis – Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life (1976)

Jerome Bruner – The Process of Education (1960)

John Dewey – Democracy and Education (1916)

Margaret Donaldson – Children’s Minds (1978)

JWB Douglas – The Home and the School (1964)

Kathryn Ecclestone and Dennis Hayes – The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education (2008)

Harold Entwistle – Antonio Gramsci: Conservative Schooling for Radical Politics (1979).

Paulo Freire – Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968/1970)

Frank Furedi – Wasted: Why Education Isn’t Educating (2009)

Helene Guldberg – Reclaiming Childhood (2009)

ED Hirsch Jnr. – The Schools We Need And Why We Don’t Have Them (1999)

Paul H Hirst – Knowledge and the Curriculum (1974) For the essay which appears as Chapter 3 ‘Liberal Education and the Nature of Knowledge’ (1965)

John Holt – How Children Fail (1964)

Eric Hoyle – The Role of the Teacher (1969)

James Davison Hunter – The Death of Character: Moral Education in an Age without Good or Evil (2000)

Ivan Illich – Deschooling Society (1971)

Nell Keddie (Ed.) – Tinker, Taylor: The Myth of Cultural Deprivation (1973)

John Locke – Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1692)

John Stuart Mill – Autobiography (1873)

Sybil Marshall – An Experiment in Education (1963)

Alexander Sutherland Neil – Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing (1960)

John Henry Newman – The Idea of a University (1873)

Michael Oakeshott – The Voice of Liberal Learning (1989) In particular for the essay “Education: The Engagement and Its Frustration” (1972)

Anthony O’ Hear – Education, Society and Human Nature: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (1981)

Richard Stanley Peters – Ethics and Education (1966)

Melanie Phillips – All Must Have Prizes (1996)

Plato – The Republic (366BC?)

Plato – Protagoras (390BC?) and Meno (387BC?)

Neil Postman – The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1995)

Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner – Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1969)

Herbert Read – Education Through Art (1943)

Carl Rogers – Freedom to Learn: A View of What Education Might Become (1969)

Jean-Jacques Rousseau – Émile or “on education” (1762)

Bertrand Russell – On Education (1926)

Israel Scheffler – The Language of Education (1960)

Brian Simon – Does Education Matter? (1985) Particularly for the paper “Why No Pedagogy in England?” (1981)

JW Tibble (Ed.) – The Study of Education (1966)

Lev Vygotsky – Thought and Language (1934/1962)

Alfred North Whitehead – The Aims of Education and other essays (1929)

Paul E. Willis – Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs (1977)

Alison Wolf – Does Education Matter? Myths about Education and Economic Growth (2002)

Michael FD Young (Ed) – Knowledge and Control: New Directions for the Sociology of Education (1971)

Michael FD Young – Bringing Knowledge Back In: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education (2007)

- Teacher training

- Continuing professional development

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Program Development Officer - Business Processes

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

THE GREAT BOOKS ACADEMY & HOMESCHOOL PROGRAM

Great Books Method

“Never before has there been such a great opportunity for parents seeking the best education for their children.” – Norris Archer Harrington

In recent years there has been an increased interest in the great books approach to education. Nowhere is this approach more realized than at schools such as St. John’s College and Thomas Aquinas College. As four year, great books programs, both of these schools focus exclusively on the original texts of the greatest writings in the history of the Western world. After reading these works, students and tutors engage in Socratic discussion groups so as to bring out the rich meaning to be found there.

Undoubtedly, there are many parents who desire for their children the traditional and classical education afforded by a great books approach who yet find themselves asking, “Just what is the Socratic Method, why should we use it, how does it work?” It is illustrative that by asking these very questions in order to understand the method, one actually initiates the method itself. To answer requires a brief discussion of Socrates, the Greek philosopher from whom the method takes its name. It is interesting to note that in any listing of great books, Socrates is never one of the authors listed. This is because Socrates never wrote a book. All of the written dialogues of Socrates we have today were written by his student, Plato.

Thus, the Socratic Method is a conversation, a discussion, wherein two or more people assist one another in finding the answers to difficult questions. Why did Socrates proceed in this manner? Despite his many claims of ignorance Socrates understood better than those with whom he spoke that it was not enough simply to “learn” facts, to memorize lessons, or to parrot lectures. To know truly, to seek wisdom, one must work toward understanding. If the question “what” leads us to see what we do and do not know, then the question “why” leads us to understand our world in a more full and fundamental manner. If a student tells you that the square on the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the squares on the two remaining sides taken together, he would, or course, be correct. But if you ask this student “why” this is so, would he be able to give you that answer? If he cannot, then he has memorized an “answer” that, while possessing certain utility, does not of itself provide understanding of causes. But if he gives any one of a number of reasoned explanations why the right triangle has the property described, then he demonstrates not only his understanding of causes, but also the ability to communicate that understanding to others.

Further, his understanding is greater to the degree that his account is the one that comes closest to the cause itself. The discussion method facilitates the student’s quest for understanding by requiring him to answer questions on his own, to ponder the validity of what others have said or written, and (not the least of which) to give reasoned support of his own opinion to the other students in the group. While the discussion method is a powerful tool, it is by no means the only activity by which people learn. There are three distinct activities by which learning takes place.

The first type of learning activity is to memorize material, and while memory skills are essential to learning, what one memorizes, one can also forget. The second activity is the development of intellectual skills such as adding, reading, and writing. The second method draws on the foundation of the first. For example, since one learns to read by reading, there are certain rules of phonics which are memorized that assist in the process.

Man does not forget that which he understands, and when a man understands both the world he lives in and his true place in it, he is empowered with the ability to choose rightly for his own betterment and the betterment of those around him. Additionally, it is important to note that the activity of increasing understanding is not limited to the material world. The phrase “faith seeking understanding” acknowledges that even those things we know by the grace of religious faith are not contrary to reason, even if they happen to be above reason. Articles of faith are known by grace and divine revelation, yet one can increase understanding of much that is held by faith. This is possible because faith and reason are complementary, they go hand in hand. Even Jesus employed discussion to force his disciples to articulate what they held by faith when he asked, “But whom do you say that I am?” Through parables and returning question for question, Jesus engaged the minds, the reason, of those with whom he spoke.

It is a fact of human nature that a man often thinks he knows something until he is forced to articulate it. In other words, an indistinct “knowledge” of something – which is really little more than a feeling – reveals its true nature in the process of being brought into the light of discussion. The beauty of the process is that in finding the limit of our knowledge we not only discover where our ignorance ends, but also where our true knowledge begins.

Group of Great Books Program Students

It has been said here that homeschooling is ideal for the foundational learning activities of intellectual skill development. On the other hand, homeschooling parents will immediately encounter problems if they seek to have their children engage in serious discussion with other children reading the same works and learning at the same level. Even a large family with many children schooling at home cannot have everyone reading and discussing The Iliad or Democracy in America (to name only two) at the same time or at the same level of comprehension. The Socratic discussion requires the challenge of one’s peers in order to push the student to excel at his greatest intellectual capacity. How then are homeschooling parents to provide such an opportunity for their children? The answer is found in the rapidly increasing opportunities for “distance learning” made possible by the Internet.

Available courses

Blended Shared Inquiry Training

- Instructor: Michael Elsey

- Instructor: Teri Laliberte

- Instructor: Josh Sniegowski

Building Internal Capacity

- Teacher: Denise Ahlquist

Close Reading

Junior Great Books Sampler

Great Books Plus

- Teacher: Pay Pal

- Teacher: Ellen Teacher11

- Teacher: Sushant Wankhede

Great Books. Great Conversation.

- About Overview

- Mission & Philosophy of Education Statement

- Biblical Foundation Statement

- Ethics Statement

- The History of Gutenberg College

- Faculty & Staff

- Board of Governors

- National Advisory Board

- School Profile

- Academics Overview

- Degree Program & Classes

- Academic Catalog

- Academic Calendar

- Reading List

- Study Abroad

- Student Life Overview

- Residence Program

- Living in Eugene, Oregon

- Spiritual Life

- Career Development Liberal Arts: Education for All Walks of Life

- Tuition & Aid Overview

- Tuition & Fees

- Financial Aid

- Admissions Overview

- Applicant Profile

- College Counseling

- How to Apply

- Continue Your Application

- Learn Overview

- The Gutenberg Podcast

- News & Events Overview

- Latest News

- Events Calendar

- 2024 Education Conference: The Independent Mind

- Great Books Symposium

- Preview Days

- Young Philosophers

- Get Involved Overview

Why a Great Books Education is the Most Practical!

Gutenberg College is a great books college. The curriculum is designed to develop good learning skills in students; they read and then discuss in small groups the writings produced by the greatest minds of Western culture as they grappled with the most fundamental questions facing human beings of all ages. When I tell people about Gutenberg College, one of the most common responses is: “It’s a good idea, but not practical.” The thinking seems to be that if one had unlimited time and money, a great books education would be very good to pursue; but in the real world, food has to be put on the table, and a great books education will not do that. I am convinced, however, that a great books education is not only practical, but, in our day and age, the most practical education available.

Modern society has adopted the historically recent perspective that the purpose of education is training for the workplace. In this view, college should provide students with skills and knowledge that will prepare them to procure reasonably high-paying, satisfying employment for the rest of their lives. The common wisdom says that the best way to achieve this goal is: first, as an undergraduate, select a promising occupation and major in the appropriate field of study; and second, after graduating, enter directly into the work force or attend a graduate or professional school for more specialized training. The logic seems to be that the sooner one concludes one’s education and begins work in one’s field, the less will be the cost of education and the better the prospects for advancement into secure, high-paying positions. While this was once a reasonable strategy, it is not suited to the economic environment currently developing.

The world is changing at a bewildering pace. Anyone who owns a computer and tries to keep up with the developments in hardware, software, and the accompanying incompatibilities is all too aware of the speed of change. This rapid change, especially technological change, has extremely important implications for the job market.

In the past, it was possible to look at the nation’s work force, determine which of the existing occupations was most desirable in terms of pay and working conditions, and pick one to prepare for. But the rapid rate of change is clouding the crystal ball. How do we know that a high paying job today will be high paying tomorrow?

A photographer told me about a talented and highly skilled artisan who touched up photographs. He was the best in our region of the country, and people knew it; because the demand for his skill was so great, he was unable to keep up with the work. A few years ago, however, this artisan suddenly closed his shop; he did not have enough work to stay in business. Due to developments in computer hardware and software, anyone with just a little training can now achieve results previously attainable by only a few highly skilled artisans. Technology had rendered this artisan’s skills obsolete. And this is not an isolated case; technology is antiquating many skills.

One could try to avoid this fate by finding an occupation unlikely to be automated, but automation is not the only cause of job elimination. Historically, mid-management positions in large corporations provided good incomes and considerable job security. However, AT&T’s recent layoffs have drawn attention to the growing trend in American companies to eliminate mid-level managers as the companies restructure to compete better in the world market. As a result, a glut of unemployed executives are having great difficulty finding employment in their field of expertise. Most of them never dreamed they would be standing in unemployment lines.

Medicine might be a more promising field. There will always be sick people to treat, and doctors have a reputation for high pay. However, recent news reports have called into question the future of this occupation. There is an excess of doctors in the United States right now, largely due to the number of foreign medical students who decide to remain in this country after they complete their training. And physicians’ incomes recently declined for the first time in decades, a change attributed to the proliferation of HMOs and managed health care providers–a trend expected to continue. To further complicate the picture, in the near future a national health care plan may rise from the ashes of President Clinton’s ill-fated one. What effect such a program would have on physicians’ incomes and working conditions is impossible to predict with certainty, but doctors ought not expect raises under such a plan. In light of such an uncertain future, should a student invest the time and money medical training requires? This is a tough question, but similar uncertainties lie in the future of many professions.

One could forego the traditionally desirable occupations and choose a field certain to grow and develop. Clearly the high demand for programmers, electrical engineers, and computer programmers appears to hold great promise for job security in the foreseeable future, even if one must work for several different employers over the years. However, no one in this field will be able to take his job for granted. Due to the rapid rate of technological change in the computer industry, people in this field need to be constantly learning and updating their skills to keep up with the new technology. In areas of state-of-the-art development, some companies do not want software writers or engineers over thirty-five years old because their training is out-of-date and they are too set in their ways to approach problems with fresh thinking. These companies prefer to replace older employees with recent graduates. Thus the longevity of one’s career in this fast changing field could be relatively short.

No matter what occupation one chooses, the future is full of question marks. Although this economic dislocation is in its early stages, statistics already indicate a high degree of instability in the job market. According to the United States government, the average American switches careers three times in his or her life, works for ten employers, and stays in each job only 3.6 years. ( Note 1 )

Such unpredictability calls for a different strategy in preparing for the job market. Rather than spending one’s undergraduate years receiving specialized training, one ought to learn more general, transferable skills which will provide the flexibility to adjust to whatever changes may occur. A well-educated worker should be able to communicate clearly with co-workers, both verbally and in writing, read with understanding, perform basic mathematical calculations, conduct himself responsibly and ethically, and work well with others. These skills would make a person well-suited to most work environments and capable of learning quickly and easily the requisite skills for a new career, should the need arise. Thus a hard-headed realism, with long- term economic security as the goal, would seem to dictate an undergraduate educational strategy of focusing on sound general learning skills–just what a great books education provides.

Therefore, a great books education makes good sense in terms of dollars spent and dollars gained when calculated over a lifetime, and, therefore, good training for the workplace. This is fortuitous, however, because a great books education is not designed with this as the primary goal. It is designed to achieve the even more practical goal historically assigned to education: to teach students how to live wisely. I say this is practical because that which helps one achieve what needs to be done is practical. Living wisely is the most important thing a person can do in his lifetime. Therefore, education with this focus is quintessentially practical.

Wise living means to live as one ought; in other words, to strive to achieve good goals by moral means. This statement immediately evokes an array of fundamental questions: Why are we here? What is valuable or worthwhile? What are the principles of right and wrong? Is there a God? Who is He? What is my relationship to Him? Without having seriously wrestled with these issues, one will be condemned to a life without direction or purpose. Without clearly defined and worthwhile goals, success and fulfillment are impossible. Therefore, one’s answers to these questions have very important implications for how one chooses to earn a living.

Is such a goal realistic or attainable by education? It is difficult to teach a person how to live wisely. In a sense, such a skill can not be taught; it can only be learned. The student must be challenged to think through these fundamental questions for himself; he must be an extremely active participant in his own education. We all derive our wisdom from careful reflection on our experience, and this reflection can be made more profound by considering the reflections of others who have had similar experiences. That is to say, we can benefit from the wisdom others have attained.

A great books education creates an educational environment conducive to the learning of wisdom. Classes are small, personal, and largely discussion based. The small class size and the discussion format encourage each student to be actively involved in consideration of important issues, and they allow the course of the discussion to be tailored to the concerns of the students. The writings of the most influential thinkers of our cultural tradition are studied, which provides many thought-provoking insights into the fundamental questions. As students work to understand these writings, they develop important learning skills–reading with understanding, thinking clearly, and writing cogently–which equip them to become life-long learners.

A great books education is not for everyone. In order to benefit from such an education, a student has to be highly motivated, mature enough to realize the importance of such a focus, and self-disciplined. Whatever reasons one might have for not pursuing a great books education, it can not be because it is not practical!

Note 1: Sue Brower, “When You Want-or Have-to Make a Career Shift.” Cosmopolitan, v. 199, no. 2 (Aug 1985), p. 229.( Back to text )

Continue the discussion:

About the author: david crabtree.

Related Posts

Taking Off and Putting On

A Meditation on Trees

Interpreting the Parable of the Prodigal Son

Truth Is Faith’s Greatest Ally

2023 Gutenberg College Commencement Address

Thomas Aquinas College is unique among American colleges and universities, offering a faithfully Catholic education comprised entirely of the Great Books and classroom discussions.

- Our Campuses

- Mission and History

- College Guide Reviews

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- News & Press

- Events Calendar

- News Archive

- College E-Letter

- The Aquinas Review

Truth, and nothing less, sets men free; and because truth is both natural and supernatural, the College’s curriculum aims at both natural and divine wisdom.

- The Great Books

- The Discussion Method

- Program Objectives

- Teaching Faculty

- Lecture & Concert Series

- St. Bernardine Library (CA)

- Dolben Library (NE)

The intellectual tradition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church infuse the whole life of Thomas Aquinas College, illuminating the curriculum and the community alike.

- New England

- Prayer Requests

- Faith in Action Blog

- California Chapel

- New England Chapel

Do you enjoy grappling with complex questions? Are you willing to engage in discussions about difficult concepts, with the truth as your ultimate goal?

- Apply to the College

- High School Summer Program

- Visit & Connect

- Send Me Information

- Tuition & Fees

- How to Apply for Financial Aid

- Financial Aid Calculator

There is always something to do at TAC — something worthwhile, something fulfilling, and something geared toward ever-greater spiritual and intellectual growth.

- Beyond the Classroom

- Beaches, Mountains & More

- Online Payments

- Student Forms & Documents

- Parent Gateway

Nothing speaks more to the versatility of the College’s academic program than the good that our alumni are doing throughout the Church and the world.

- Career Services

- Alumni Association

- Alumni Portal

- Arts & Media

- Law & Public Policy

- Priesthood / Religious Life

A mudslide that has shut down both lanes on Highway 150 between the College’s California campus and Santa Paula. Although the California Department of Transportation has begun preparations for clearing the roadway, officials do not expect to finish the work before sometime this summer. Therefore, if you will be traveling to campus from points south, please be sure to give yourself enough time to navigate the detour route, which will take you along Highways 126, 101, and 33. Directions to campus

Why the Great Books?

By Marcus R. Berquist

One of the most obvious features of a school is its curriculum, and within its curriculum, the list of books read. Thus, when a school has a “great books” curriculum, it is almost inevitable that it should be characterized as that kind of school. In studying the nature and purpose of the school, one begins with this assumption, and tries to understand everything within its light. Accordingly, since Thomas Aquinas College has such a curriculum, it is frequently likened to other schools which make use of the same books, and its educational program is assumed to be essentially the same.

The Great Books vs. Textbooks

Such an assumption is reasonable, for not only is this reading a true point of resemblance, but it is also based upon principles which are to a considerable extent held in common. In the first place, it is commonly held that the great books are intrinsically better than the multitude of textbooks which have replaced them in the curricula of colleges everywhere. These latter, indeed, have been introduced to make the former more accessible and to proportion them somehow to less able minds. They are the outgrowth of necessities imposed by universal education, and suffer from the dilution of content which inevitably characterizes such education. This is why a school which aims at the best will necessarily concentrate upon a study of the great books, and seek students with the ability and the dedication to learn from them.

Another reason why the great books are preferred to textbooks is that the latter, almost without exception, are “secondary sources” — that is, they are two steps removed from reality. They are, as it were, thoughts about thoughts. The great books, by contrast, are much closer to common experience in its fullness; they raise questions and pursue inquiries which arise directly from a wonder about things themselves. On this account, they are of the greatest importance to beginners, for they begin where thought itself must begin if it is to bear any fruit.

A third reason for the study of the Great Books is that students are thereby allowed and encouraged to become directly familiar with the greatest minds. They are not limited to what passes through the minds of their instructors and the authors of textbooks, which can hardly be more than diminished and perhaps distorted views of what exists more fully and more powerfully in the great books themselves. And when educators themselves have been educated in such a way, and for many generations, the original light can scarcely be seen. But with a study of the great books, students have a much better chance to encounter wisdom and to become wise themselves.

The Great Books: A Great Defense

Lastly, the careful study of the great books, especially at the beginning of one’s education, is the best defense against the unreflective historicism that so burdens the modern mind. By “historicism” here we mean the insistence that every human work must be studied within its historical context, as a “moment” in some historical process. The consequence of this historicism is that every work is in fact read, if at all, in bits and pieces, and within a framework peculiarly modern, imposed by contemporary assumptions which may be no more than fashions. This framework itself, because customary, is seldom noticed, and never examined. But when one has had independent access to the great books, this historicism becomes conspicuous, and is no longer assumed as a matter of course. One begins to read the books as they were written and consider issues on their own merits.

The Same Means, But Different Ends

Reasons such as these are common ground for most schools with great books programs. However, it is possible to overestimate these resemblances, and to be impressed by the likenesses which, though true and significant, are quite secondary. One may be misled by the maxim, plausible enough in itself, that what is held in common is what is most important. In the present case, the application of this maxim would be seriously mistaken, for it would confuse a community of means with a community of ends. It would be like asserting that the common network of roads we all make use of is more important than the various destinations we reach along those roads. Or like assuming that since we are all using the same roads, we are all going to the same place. For the books will be read, not just to be read, but for some further purpose, and it makes no small difference — rather it makes all the difference — what this purpose is. Distracted by obvious but secondary points of resemblance, one may not discern significant differences in ends.

When one finds a Catholic school with a great books curriculum, one is inclined to suppose that Catholic belief is incidental to its educational program, and that (at most) it modifies but does not determine that program. This inclination is encouraged by Catholic educators themselves, who have by and large reduced Catholicism in their schools to some indefinable and insignificant “presence.” Catholicism, it seems, makes a difference, but not an educational difference. In this view, the end of a great books education, and perhaps of liberal education generally, would transcend such a difference. Yet since differences of this sort concern the greatest and most important truths, one might well wonder what this common end could be. If it does not arise from a common conviction concerning the highest matters, it must concern something inferior, perhaps trivial.

Radical Disagreements

A similar difficulty arises about the great books themselves. By what standard are they judged great? Is it that they contain a true doctrine about the highest matters? Perhaps some of them do, but taken as a group they disagree radically among themselves about these very matters, not only in regard to the truth about them but also in regard to the right method of pursuing that truth. They even disagree about what is worth studying and whether there are actually any “highest matters.” If the end of liberal education is a kind of wisdom, however imperfectly achieved, most of these books must be judged failures.

Thus, when viewed as defining a certain kind of education, the great books cannot be regarded as teachers, nor their students as disciples. By their immense variety and mutual opposition they exclude discipleship. Of course it is possible that discipleship to a particular master may come out of such a curriculum — one might, for example, become a Cartesian through reading Descartes. But discipleship cannot be the intent of such a curriculum, nor can a school define itself by discipleship while still defining its educational program by the great books. Thus, for example, no school which defines its education program in this way could honestly describe itself as Catholic, since to be a Catholic is to be a disciple of a very particular kind.

The Catholic Intellectual Tradition

The intellectual tradition of the Catholic Church contains a clear and detailed account of what education should be. Perhaps more than any other tradition, it insists that there are great books, but it goes much further than this. It explains why certain books are great, and it distinguishes among them as regards their excellence and their authority. But it does not regard the understanding of great books as an end in itself. Rather, it orders the study of all such books to an understanding of the truth about reality — a reality of which it speaks with confidence, from the word of God which it receives in faith.

Marcus R. Berquist was a founder of Thomas Aquinas College. He served on the teaching faculty for 40 years until his death in 2010.

© 2024 Thomas Aquinas College Board of Governors. All rights reserved.

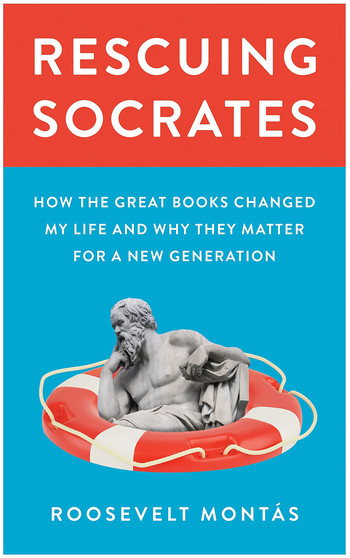

Why the Great Books Still Matter

In Rescuing Socrates , American-studies professor Roosevelt Montás ’95CC, ’04GSAS makes the case for the kind of liberal education embodied in Columbia’s Core Curriculum.

Lots of people need our help — why rescue Socrates?

The title actually works on three levels. It signals a real moment when I found a volume of Plato’s dialogues in a garbage pile in New York and it changed my life. It alludes to the attempt to free Socrates from jail before he was executed for corrupting the youth of Athens (he refused the help). And it highlights my main topic: revitalizing the centrality of liberal education within the undergraduate curriculum. The book follows these strands, part intellectual memoir, part personal reading of four transformative thinkers — Socrates, Augustine, Freud, and Gandhi — and part polemic.

You say undergraduates often arrive at college “longing for meaning.” Can Socrates rescue them ?

His message that “the unexamined life is not worth living” is even more relevant today. Socrates struggled philosophically with the ascendant values of his time — materialism, ambition, and raw political struggle — and proposed a different way of valuing what matters in a human life. Students are often profoundly moved, sometimes even profoundly reoriented, by encountering his uncompromising, full-throttled embrace of the life of the mind.

In some of the most evocative passages in the book, you share your own story. Why?

Describing the ideals of a liberal education and the value of wrestling with texts that have had an outsized impact on the world can sound kind of lofty, unreachable, even sappy. I hoped to make that impact concrete to readers by showing them how it actually played out in my life. At twelve, I moved to New York from a remote village in the Dominican Republic, not knowing English. I attended under-resourced public schools in Queens and then experienced the culture shock of attending Columbia as a first-generation college student. Ultimately, I joined the faculty. Every life is different, but I want people to understand the kind of awakening, empowering, unfolding, and flourishing that this kind of education brought me. Students, and especially those that come from marginalized communities, are often told their education should serve a practical end, that liberal education is an elitist privilege. I argue that it is, in fact, the most powerful tool we have to subvert the hierarchies of social privilege that keep those who are down down.

As director of the Center for the Core Curriculum for ten years, did you have to respond to a lot of people who objected to the very idea of great books?

Yes. A lot of that criticism often focuses on how the great-books tradition has excluded certain groups, including and most especially women, and how it can be used to support and legitimate other forms of exclusion. That’s all real. Acknowledging and dealing with that is part of the learning. Yet these books still matter. We have to be able to disentangle their role in the cultural and institutional evolution of our world from the violations of norms of justice sometimes encoded in them.

It’s not just great books that changed your life but also great teachers.

Yes. Liberal education is something that happens between people, not between books and people or institutions and people. It requires a small, curated artisanal practice in which a student’s individuality is recognized and cultivated for what it is. And so it may produce in you something entirely different than it produces in me. It might make me a brilliant politician; it may make you a recluse and a monk. It takes the individuality of the student as its centerpiece, and that takes another individuality to see it. I had many great teachers.

We live in a particularly fractious time. Can a liberal education help us find common ground?

Absolutely. Reading these books creates a tool of communication and communion across generations, cultures, races, and other lines of diversity. All of our points of difference can come together with a shared vocabulary and meet around shared human questions, bringing in different life experiences and cultural frameworks of interpretation. This discursive connective tissue — a shared way of speaking, debating, and relating — is just extraordinarily valuable, especially in a diverse democracy. It can leave us with a sense of the complexity of the human experience, a sense that there’s always another side to every question and another way of seeing the world.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2022 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "The Examined Life."

More From Books

6 New Books to Add to Your Summer Reading List

All by Columbia alumni authors

Review: Long Island

By Colm Tóibín

Review: The Stone Home

By Crystal Hana Kim ’09CC, ’14SOA

Stay Connected.

Sign up for our newsletter.

General Data Protection Regulation

Columbia University Privacy Notice

Mortimer Adler: Champion of Great Books Education

- Video: Global Warming Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit ...

- Article: Global Warming Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit ...

- Entry: Global Warming Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit ...

Even now, decades after his death, eighth-graders everywhere get to read the Odyssey , thanks to the efforts of a man born to Jewish immigrants in the heart of New York City. Philosopher and educator Mortimer Adler is largely responsible for what we call Great Books education. Adler wanted more for America’s youth than he had received from his Ivy League professors, so he worked to bring the American education system back into the Western tradition.

Adler was born into a world with diminishing respect for that tradition. Writings from Homer to Augustine were taught only to the elite, and usually in excerpts. Charles Eliot, Harvard University’s president at the time, had purged most of the core curriculum at his institution, an act that put the hammer to Greek and Latin studies. Eliot tried to remedy the situation by publishing “Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf of Books,” a compilation of influential works of literature and philosophy, but Adler didn’t think this adequately accounted for the classical tradition. Adler’s professor at Colombia, John Dewey, spent much of his life fighting the liberal arts education model, favoring vocational training for students. The two did not get along.

As Adler saw it, the benefit to his Ivy League education was revealed to him in a single English class. John Erskine, an English professor who became the first president of the Juilliard School, introduced Adler to the Socratic seminar. In Erskine’s class, students would read a book every week and discuss their findings in the classroom. Erskine would speak as little as possible, only asking questions to guide students to new topics. Adler went on to popularize this method, an effort now considered one of his greatest accomplishments.

After graduating from Colombia, Adler began his crusade against the ideas made popular by Dewey and his associates. He disdained the idea of training students for a single job and scolded those who discouraged the goal of self-improvement. In the preface to his book “Aristotle for Everybody,” Adler wrote, “When I say ‘everybody,’ I mean everybody except professional philosophers; in other words, everybody of ordinary experience and intelligence unspoiled by the sophistication and specialization of academic thought.” He wrote for everyone, of any age and class, simply because he believed it was right for them to be educated.

When he wasn’t writing books, Adler was finding other ways to get his message across. He ran night schools for labor unions, made appearances on television and radio programs, and developed The Great Books of the Western World series for Encyclopedia Britannica. The more people who knew the themes of the great books, the more people there would be who could rejoice in and contribute to what Adler called “the Great Conversation.”

In his studies of literature and philosophy, Adler found common topics of discussion. The ideas of Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, and other ancient philosophers overlapped, which proved to Adler that some topics are prevalent throughout time and across cultures. Adler assembled a guide to these ideas in a volume he called “A Syntopicon.” Education in great books meant following the themes in the “Syntopicon” and ultimately joining in the Great Conversation about them. By doing so, a larger number of people than ever before could engage with these ideas. Broadening participation in such philosophical discussion was one of Alder’s main goals.

Many of Adler’s critics wondered what the point was in continuing the Great Conversation. As they saw it, a common person could add little to the findings of Aristotle, and Aristotle, in turn, had little to say that addressed present problems. In Adler’s mind, however, Aristotle’s insights were of permanent value, and common people could and should engage with them, learn from them, and even try to put them into practice. The Great Conversation that Adler reignited a century ago is now a tool that anyone can use to craft a common intellectual heritage.

The study of integrated humanities through a chronological framework that melds history, philosophy, and literature together owes to the work of Mortimer Adler. This practice has extended from higher education to primary and secondary schools across the country. Americans would do well to reflect on and revisit these philosophical inquiries. In doing so, they may yet contribute, in their own small way, to the Great Conversation.

Erik Ellis is a Research Fellow at the Center for Thomas More at the University of Dallas and works in the faculty of philosophy at the University of the Andes in Santiago, Chile. This overview of Mortimer Adler is based on his interview with Scott Bertram on the Hillsdale College Classical Education Podcast .

Related Articles

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What’s So Great About Great-Books Courses?

By Louis Menand

Roosevelt Montás was born in a rural village in the Dominican Republic and immigrated to the United States when he was eleven years old. He attended public schools in Queens, where he took classes in English as a second language, then entered Columbia College through a government program for low-income students. After getting his B.A., he was admitted to Columbia’s Ph.D. program in English and Comparative Literature when a dean got the department to reconsider his application, which had been rejected. He received a Ph.D. in 2004 and has been teaching at Columbia ever since, now as a senior lecturer, a renewable but untenured appointment. He is forty-eight.

Arnold Weinstein is eighty-one. Although he was an indifferent student in high school, he was admitted to Princeton, spent his junior year in Paris, an experience that fired an interest in literature, and received a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1968. He was hired by Brown, was tenured in 1973, and is today the Richard and Edna Salomon Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature. These two men started on very different life paths and ended up writing the same book.

They are even being published by the same university press, Princeton. Montás’s is called “ Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation ”; Weinstein’s is “ The Lives of Literature: Reading, Teaching, Knowing .” The genre, a common one for academics writing non-scholarly books, is a combination of memoir (some family history, career anecdotes), criticism (readings of selected texts to illustrate convictions of the author’s), and polemic against trends the author disapproves of. The polemic can sometimes take the form of “It’s all gone to hell.” Montás’s and Weinstein’s books fall into the “It’s all gone to hell” category.

Both men teach what are called—unfortunately but inescapably—“great books” courses. Since Weinstein works at a college that has no requirements outside the major, his courses are departmental offerings, but the syllabi seem to be composed largely of books by well-known Western writers, from Sophocles to Toni Morrison. At Columbia, undergraduates must complete two years of non-departmental great-books courses: Masterpieces of Western Literature and Philosophy, for first-year students, and Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West, for sophomores. These courses, among others, known as “the Core,” originated around the time of the First World War and have been required since 1947. Montás not only teaches in the Core; he served for ten years as the director of the Center for the Core Curriculum.

Although Montás and Weinstein are highly successful academics at two leading universities, where they are, no doubt, popular teachers, they feel alienated from and, to some extent, disrespected by the higher-education system. As they see it, they are doing God’s work. Their humanities colleagues are careerists who have lost sight of what education is about, and their institutions are in service to Mammon and Big Tech.

It will probably not improve their spirits to point out that professors have been making the same complaints ever since the American research university came into being, in the late nineteenth century. “Rescuing Socrates” and “The Lives of Literature” can be placed on a long shelf that contains books such as Hiram Corson’s “The Aims of Literary Study” (1894), Irving Babbitt’s “Literature and the American College” (1908), Robert Maynard Hutchins’s “ The Higher Learning in America ” (1936), Allan Bloom’s “ The Closing of the American Mind ” (1987), William Deresiewicz’s “ Excellent Sheep ” (2014), and dozens of other impassioned and sometimes eloquent works explaining that higher education has lost its soul. It’s a song that never ends.

So, although Montás and Weinstein seem to think that things went wrong recently, things (from the point of view they represent) were wrong from the start. The conflict these professors are experiencing between their educational ideals and the priorities of their institutions is baked into the system.

That conflict is essentially a dispute over the purpose of college. How did the great books get caught up in it? In the old college system, the entire curriculum was prescribed, and there were lists of books that every student was supposed to study—a canon. The canon was the curriculum. In the modern university, students elect their courses and choose their majors. That is the system the great books were designed for use in. The great books are outside the regular curriculum.

The idea of the great books emerged at the same time as the modern university. It was promoted by works like Noah Porter’s “Books and Reading: Or What Books Shall I Read and How Shall I Read Them?” (1877) and projects like Charles William Eliot’s fifty-volume Harvard Classics (1909-10). (Porter was president of Yale; Eliot was president of Harvard.) British counterparts included Sir John Lubbock’s “One Hundred Best Books” (1895) and Frederic Farrar’s “Great Books” (1898). None of these was intended for students or scholars. They were for adults who wanted to know what to read for edification and enlightenment, or who wanted to acquire some cultural capital.

The idea made its way into universities after 1900 as part of a backlash against the research model, led by proponents of what was called “liberal culture.” These were professors, mainly in the humanities, who deplored the university’s new emphasis on science, specialization, and expertise. For the key to the concept of the great books is that you do not need any special training to read them.

In a great-books course of the kind that Montás and Weinstein teach, undergraduates read primary texts, then meet in a classroom to share their responses with their peers. Discussion is led by an instructor, but the instructor’s job is not to give the students a more informed understanding of the texts, or to train them in methods of interpretation, which is what would happen in a typical literature- or philosophy-department course. The instructor’s job is to help the students relate the texts to their own lives. For people like Montás and Weinstein, it is also to personify what a life shaped by reading books like these can be. “The teacher models the still living power of the book,” as Weinstein puts it.

You can see the problem. Universities like Brown and Columbia make big investments in training scholars and researchers in their doctoral programs, and then, after they are credentialled and hired as professors, supporting their work with office and laboratory space, libraries, computers and related technology, research budgets, conference and travel funds, sabbaticals, and so on. Why should an English professor who got his degree with a dissertation on the American Transcendentalists (as Montás did), and who doesn’t read Italian or know anything about medieval Christianity, teach Dante (in a week!), when you have a whole department of Italian-literature scholars on your faculty? What qualifies a man like Arnold Weinstein, who has spent his entire adult life in the literature departments of Ivy League universities, to guide eighteen-year-olds in ruminations on the state of their souls and the nature of the good life?

It’s not an accident or a misfortune that great-books pedagogy is an antibody in the “knowledge factory” of the research university, in other words. It was intended as an antibody. The disciplinary structure of the modern university came first; the great-books courses came after. As Montás says, “The practice of liberal education, especially in the context of a research university, is pointedly countercultural.”

Montás is using the term “liberal education” mistakenly. Virtually every course at an élite school like Columbia, from poetry to physics, is part of a liberal education. “Liberal” just means free and disinterested. It means that inquiry is pursued without fear or favor, regardless of the outcome and whatever the field of study. Universities exist to protect that freedom. But Montás is right about the countercultural part. Great-books courses tend to be taught against the grain of academic disciplinary paradigms.

This has obvious educational value. Many students who take a great-books-type course enjoy encountering famous texts and seeing that the questions they raise are often relevant to their other coursework. And some students experience a kind of intellectual awakening, which can be inspiring and even transformational. For students who are motivated—and motivation is half of learning—these courses really work. They are happy to read Dante in translation and without a scholarly apparatus, because they want to get a sense of what Dante is all about, and they know that if they don’t get it in college they are unlikely to get it anywhere else.

Undergraduate teachers, whatever their training, can play a role as a transitional parent figure, someone students can talk to who is not privy to their personal or social lives, someone who will let them have the keys to the car no questions asked. And students profit from learning how universities operate and arguing about what college is for. It opens up the experience for them, gives the system some transparency and the students some agency.

So why the tsuris? At this point, great-books-type courses—that is, courses where the focus is on primary texts and student relatability rather than on scholarly literature and disciplinary training—are part of the higher-education landscape. Few colleges require them, but many colleges happily offer them. The quarrel between generalist and specialist—or, as it is sometimes framed down in the trenches, between dilettante and pedant—is more than a hundred years old and it would seem that this is not a quarrel that one side has to win. Montás and Weinstein, however, think that the conflict is existential, and that the future of the academic humanities is at stake. Are they right?

Between 2012 and 2019, the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded annually in English fell by twenty-six per cent, in philosophy and religious studies by twenty-five per cent, and in foreign languages and literature by twenty-four per cent. In English, according to the Association of Departments of English, which tracked the numbers through 2016, research universities, like Brown and Columbia, took the biggest hits. More than half reported a drop in degrees of forty per cent or more in just four years.

The trend is national. Some departments have maintained market share, of course, and creative-writing classes seem to be popular everywhere. But, in general, undergraduates have largely stopped taking humanities courses. Only eight per cent of students entering Harvard College this fall report that they intend to major in the arts and humanities, a division that has twenty-one undergraduate programs.

The decline in student interest affects doctoral programs as well, and this fact is crucial, because doctoral programs are the reproductive organs of the entire system. Fewer graduate students are admitted, because the job market for humanities Ph.D.s is contracting. More important, no one is sure how to teach the students who do get in. If courses in the traditional subfields of literary studies (medieval poetry, early-modern drama, the eighteenth-century novel, and so on) are not attracting undergraduates, shouldn’t new Ph.D.s be trained differently? If so, given that faculties are mostly trained in the traditional subfields themselves, who is going to do it?

And, even if you could completely redesign doctoral education, it takes at least six years to get a Ph.D. in the humanities (the median time is more than nine years) and another six years, minimum, to get tenure. An academic discipline is a big ship to turn around, especially when it is taking on water.

Montás and Weinstein don’t cite these figures. They don’t cite any figures, actually, because even if business were booming it would make no difference to them. But this is the real-world context in which they are publishing their books. This is the moment they have chosen to inform readers that academic humanists are not doing their job. “Liberal education is impaired and imperiled,” Montás reports. “Too often professional practitioners of liberal education—professors and college administrators—have corrupted their activity by subordinating the fundamental goals of education to specialized academic pursuits that only have meaning within their own institutional and career aspirations.” “Corrupted” is a pretty strong word.

What humanists should be teaching, Montás and Weinstein believe, is self-knowledge. To “know thyself” is the proper goal. Art and literature, as Weinstein puts it, “are intended for personal use, not in the self-help sense but as mirrors, as entryways into who we ourselves are or might be.” Montás says, “A teacher in the humanities can give students no greater gift than the revelation of the self as a primary object of lifelong investigation.” You don’t need research to learn this. Research is irrelevant. You just need some great books and a charismatic instructor.

For the advocates of liberal culture a century ago, the false god of literature departments was philology. Today, the false god is “theory.” Montás complains that contemporary theory—he calls it “postmodernism”—subverts the college’s educational mission by calling into question terms like “truth” and “virtue.” A postmodernist, in his definition, is a person who believes that there is no capital-T truth, that “true” is just the compliment those with power pay to their own beliefs. “This unmooring of human reason from the possibility of ultimate truth in effect undermines all of Western metaphysics,” he tells us, “including ethics.” (He blames this all on Friedrich Nietzsche, whom he calls “Satan’s most acute theologian,” which is an amazing thing to say. Nietzsche wanted to free people to embrace life, not to send them to Hell. He didn’t believe in Hell. Or theology.)

Weinstein’s criticism of theory is somewhat less apocalyptic. For him, theory represents a desperate and wrongheaded attempt—he calls it “the humanities’ ‘last stand’ ”—to introduce rigor and objectivity into literary studies. He doesn’t think rigor and objectivity have a place in an undergraduate literature course. “You won’t find very much of them in my classroom,” he assures us. “In my crazier moments I think that rigor may be akin to rigor mortis.”

But questioning the meaning of accepted values has been a major theme in Western thought since Socrates, and “truth” and “virtue” were never exempt. Postmodernism is not a license to shoplift. People who see “truth” and “virtue” as functions of power relations tend to be hyperethical, because they see power disparities everywhere. Postmodernists do not run more red lights than evangelicals do.

And if, as these authors insist, education is about self-knowledge and the nature of the good, what are those things supposed to look like? How do we know them when we get there? What does it mean to be human? What exactly is the good life?

Oh, they can’t say. The whole business is ineffable. We should know better than to expect answers. That’s quant-thinking. “The value of the thing,” Montás explains, about liberal education, “cannot be extracted and delivered apart from the experience of the thing.” Literature’s bottom line, Weinstein says, is that it has no bottom line. It all sounds a lot like “Trust us. We can’t explain it, but we know what we’re doing.”

In the creation of the modern university, science was the big winner. The big loser was not literature. It was religion. The university is a secular institution, and scientific research—more broadly, the production of new knowledge—is what it was designed for. All the academic disciplines were organized with this end in view. Philology prevailed in literature departments because philology was scientific. It represented a research agenda that could produce replicable results. Weinstein is not wrong to think that critical theory has played the same role. It does aim to add rigor to literary analysis.

For Montás and Weinstein, though, science is the enemy of ethical insight and self-knowledge. Science instrumentalizes, it quantifies, it reduces life to elements that are, well, effable. Weinstein can see that students might think that science courses are useful for a successful career, but he thinks that “success” is just another false idol. He writes, “One has read a great deal about ‘quants’ being gobbled up by investment firms, hired on the strength of their mathematical prowess, hence likely to add to bottom lines. What actually does a bottom line mean? Is anyone asking about judgment? Does any university or graduate school transcript even whisper anything about judgment? Values? Priorities? Ethics?”

Weinstein won’t even call what students learn in science courses “knowledge.” He calls it “information,” which he thinks has nothing to do with how one ought to live. “Life is more than reason or data,” he tells us, “and literature schools us in a different set of affairs, the affairs of heart and soul that have little truck with information as such.”

For Montás, the trouble with science is that it answers the important questions—Who am I? How shall I live?—in “purely materialistic terms.” He blames this on a writer who died in 1650, René Descartes. “Today, the heirs to Descartes’s project are perhaps most visible in Silicon Valley,” Montás says, “but the ethic that informs his approach is pervasive in the broader culture, including the culture of the university.”

What did Descartes write that set us on the road to Facebook? He wrote that scientific knowledge can lead to medical discoveries that improve health and prolong life. Montás calls this proposition “Faustian.” He says that it implies that there is “no higher value than the subsistence and satisfaction of the self,” and that this is what college students are being taught today.

Humanists cannot win a war against science. They should not be fighting a war against science. They should be defending their role in the knowledge business, not standing aloof in the name of unspecified and unspecifiable higher things. They need to connect with disciplines outside the humanities, to get out of their silos.

Art and literature have cognitive value. They are records of the ways human beings have made sense of experience. They tell us something about the world. But they are not privileged records. A class in social psychology can be as revelatory and inspiring as a class on the novel. The idea that students develop a greater capacity for empathy by reading books in literature classes about people who never existed than they can by taking classes in fields that study actual human behavior does not make a lot of sense.

Knowledge is a tool, not a state of being. Universities are in this world, and education is about empowering people to deal with things as they are. Students at places like Brown and Columbia want to make the world a better place, and they can see, as Descartes saw, that science can provide tools to do this. If some of those students make a lot of money, who cares?

Isn’t it a little arrogant for humanists like the authors of these books to presume that economics professors and life-science professors and computer-science professors don’t care about their students’ personal development? The humanities do not have a monopoly on moral insight. Reading Weinstein and Montás, you might conclude that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth. Take my word for it, we are not. We are not better or worse than anyone else. I have read and taught hundreds of books, including most of the books in the Columbia Core. I teach a great-books course now. I like my job, and I think I understand many things that are important to me much better than I did when I was seventeen. But I don’t think I’m a better person. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

- How we became infected by chain e-mail .

- Twelve classic movies to watch with your kids.

- The secret lives of fungi .

- The photographer who claimed to capture the ghost of Abraham Lincoln .

- Why are Americans still uncomfortable with atheism ?

- The enduring romance of the night train .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .