Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sustainable customer retention through social media marketing activities using hybrid SEM-neural network approach

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft

Affiliation UCSI Graduate Business School, UCSI University, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Faculty of Entrepreneurship and Business, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Pengkalan Chepa, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

Affiliation UKM-Graduate School of Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

- Qing Yang,

- Naeem Hayat,

- Abdullah Al Mamun,

- Zafir Khan Mohamed Makhbul,

- Noor Raihani Zainol

- Published: March 4, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899

- Reader Comments

Social media has changed the marketing phenomenon, as firms use social media to inform, impress, and retain the existing consumers. Social media marketing empowers business firms to generate perceived brand equity activities and build the notion among consumers to continue using the firms’ products and services. The current exploratory study aimed to examine the effects of social media marketing activities on brand equity (brand awareness and brand image) and repurchase intention of high-tech products among Chinese consumers. The study used a cross-sectional design, and the final analysis was performed on 477 valid responses that were collected through an online survey. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) and artificial neural network (ANN) analysis were performed. The obtained results revealed positive and significant effects of trendiness, interaction, and word of mouth on brand awareness. Customisation, trendiness, interaction, and word of mouth were found to positively affect brand image. Brand awareness and brand image were found to affect repurchase intention. The results of multilayer ANN analysis suggested trendiness as the most notable factor in developing brand awareness and brand image. Brand awareness was found to be an influential factor that nurtures repurchase intention. The study’s results confirmed the relevance of social media marketing activities in predicting brand equity and brand loyalty by repurchase intention. Marketing professionals need to concentrate on entertainment and customisation aspects of social media marketing that can help to achieve brand awareness and image. The limitations of study and future research opportunities are presented at the end of this article.

Citation: Yang Q, Hayat N, Al Mamun A, Makhbul ZKM, Zainol NR (2022) Sustainable customer retention through social media marketing activities using hybrid SEM-neural network approach. PLoS ONE 17(3): e0264899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899

Editor: Qihong Liu, University of Oklahama Norman Campus: The University of Oklahoma, UNITED STATES

Received: September 12, 2021; Accepted: February 19, 2022; Published: March 4, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Yang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

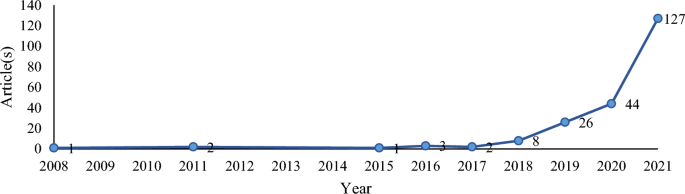

By definition, social media encompass online applications, platforms, and media promoting interaction, collaboration, and content sharing among users [ 1 ]. The associated marketing component renders it highly convenient to spread information due to its synergy-inducing scale [ 2 ], thus highlighting social media as a practical choice for such purpose. In fact, effective information dissemination is a crucial factor in ensuring the success of social media marketing [ 3 ]. In 2018, Chinese social media users increased by 100 million [ 4 ], while the beginning of 2020 recorded an increment for global social media users amounting to 3.8 billion. Simultaneously, recent data has shown that more than 1 billion people in China employ social media, as reflected by its social media popularising rate of 74% [ 5 ]. In line with this, the Global Web Index has reported that a user typically makes use of social media for up to two hours and 42 minutes per day [ 6 ]. Therefore, the last decade has underlined social media marketing as an essential marketing tool, emerging as a mainstream research aspect [ 7 ].

In general, social media offer consumers a new platform for understanding a product and interacting with people anywhere globally to share product-related experiences [ 8 , 9 ]. This population is typically embedded with different awareness orientations before making a purchase decision, which can be divided into brand awareness and value awareness [ 10 ]. To compare: consumers having the brand awareness orientation perceive the brand as a symbol of credibility and prestige, whereas those with value awareness usually check and compare the prices and quality of different brands through social media to ensure a best-value purchase [ 11 ]. To this end, many companies employ social media in carrying out low-cost and high-efficiency marketing activities for consumers [ 7 , 12 ]. Social media is a marketing tool wielded for four primary purposes: market research and feedback; brand promotion and reputation management; customer service and customer relationship management; and business network [ 13 , 14 ]. Despite its active incorporation in companies to increase visibility and gain more customers, social media-focused customer loyalty-building and strengthening remain a less-explored area [ 13 , 15 ]. Therefore, understanding how social media activities affect customer loyalty is essential for enhanced marketing strategies.

The current study discussed the impact of social media-based marketing on brand loyalty through brand equity. Entrepreneurial and large business firms actively engage with social media-based marketing activities to inform and build attractiveness for their prospective and current consumers [ 16 ]. Furthermore, the study distinctively highlighted the impact of social media-based marking activities on consumer-level brand equity and brand loyalty in terms of repurchase intention.

The purpose of this article is to systematically and comprehensively examine the impact yielded by social media marketing activities (SMMA) towards the creation of consumer brand awareness and brand image. Accordingly, the research goal denotes filling the gaps identified in previous efforts, which include: (1) evaluating the effect of the components of SMMA (i.e., entertainment, customisation, trends, interaction, and word of mouth) on brand awareness and image; and (2) exploring the impact of SMMA on Chinese consumer repurchase intention through brand awareness and brand image of high-tech products.

2. Literature review

2.1 theoretical foundation.

Russel and Mehrabian initially conceived the pioneering Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model in early 1974, which underlines the following operating principle: environmental stimuli (S) lead to emotional responses (O), thereby promoting behavioral responses (R). Subsequently, countless retail scholarships have utilised the SOR model to illustrate its importance in retailing [ 17 , 18 ]. The model is currently widely implemented in consumer behavior studies [ 19 – 22 ]. Based on previous studies, SMMA plays a vital role in influencing customer level of brand awareness and brand image. Accordingly, the SOR model offers a structured method for evaluating the impact of perceived SMMA on brand equity and repurchase intention [ 11 , 23 – 25 ].

The SOR model is selected as the research model for the current study for three specific reasons. First, previous studies have comprehensively implemented the SOR framework to study human-computer interaction leading to consumer buying behavior [ 26 – 28 ]. Secondly, the SOR theory provides the direction of investigations undertaken in the hotel management, food delivery, and other services industries [ 29 – 32 ]. Finally, a scant amount of literature is available pertaining to consumer behavior in China despite the model’s extensive implementation across different countries in assessing the particular topic.

2.1.1. SMMA recognised as an environmental stimulus.

Previous research efforts have detailed the role played by SMMA to aid in creating value, enhancing brand awareness, and building customer relationships [ 23 – 25 ]. Furthermore, some studies have particularly emphasised its use as a marketing stimulus towards enhancing the customer shopping experience and influencing purchase behavior. For example, Zhang and Benyoucef’s [ 22 ] research has supported SMMA as an environmental stimulus in the SOR model. In contrast, social media is thought to play an important role when companies build relationships with their customers via marketing activities [ 24 ]. Similarly, Kim and Ko [ 33 ] have differentiated its characteristics into five categories, namely: entertainment, interaction, fashion, customisation, and WOM, which are then applied to luxury brands. Subsequently, previous works led to this research defining SMMA components as entertainment, interactivity, popularity, customisation, and perceived risk accordingly.

Entertainment is the result of fun and entertainment in using social media [ 34 ]. Thus, the entertainment component of social media is deemed essential, whereby it enriches positive emotions and generates behaviours that involve purchase intentions [ 14 ]. Interaction is the exchange of opinions and ideas occurring between social media and consumers. A stronger interaction on social media allows consumers a deeper understanding of brand content and empowers better brand comprehension of user ideas and preferences, thereby contributing to the brand’s social media platform itself [ 24 ]. Concurrently, consumers can also exchange realised social media platform experiences [ 14 ], whereas social media user-generated content (UGC) has emerged as an alternative brand-customer interaction [ 24 , 35 ]. Trendiness is crucial and otherwise defined using the term ‘trends,’ which details the provision of the latest information pertaining to any products or services [ 25 ]. Tangentially, Valaei and Nikhashemi’s [ 36 ] research has underlined brand style and price as particularly notable factors determining Generation Y consumers’ willingness to buy fashion items. Therefore, the trends and styles positioned by brands can attract more consumers of the younger age range due to their likings for new trends and trendy brands [ 37 ]. Customisation is defined as the degree to which a brand provides specific services to meet the unique tastes and needs exhibited by consumers [ 38 ]. During the consumption process, most customers still want to obtain specific services. Therefore, the current research describes survey personalisation as customer perception of social media in providing customised services and meeting their preferences. Accordingly, brands can provide private and customised experiences tailored to each customer based on personalised portals and offline shops to improve further their brand image and brand loyalty [ 39 ]. Besides, personalisation will accurately help customers locate the products they require, thus indirectly promoting the purchases [ 40 ]. Word of mouth (WOM) is the most natural and common phenomenon encountered in consumer behavior [ 22 ]. It can denote a series of communication activities carried out by a company or product, which is usually regarded as non-commercial and private [ 41 ]. Similarly, WOM is also a source of information in the purchase decision process in which consumers will consider product performance, changes before and after purchase, and consequences of the purchase decision [ 42 , 43 ]. The more familiar and trustworthy the WOM information sources are, the more significant their impact on purchasing decisions [ 44 ]. WOM is more effective than alternative SMMA channels in influencing consumer decision-making [ 45 ].

2.1.2. Brand equity recognised as customer emotional response.

In general, brand equity is defined as intangible assets related to brand names and brand symbols due to the possible effect of brand preference on the brand value as perceived by brand consumers [ 46 ]. Keller [ 47 ] has classified it into brand awareness and brand image, thereby describing brand equity as a social and cultural phenomenon. Meanwhile, brand image is firmly embedded in consumer minds and denotes the associated symbolic meaning, which the brand pursues [ 48 ]. By definition, brand image denotes the impression held by a brand in consumer memory, thus categorised into deep, general, and vague impressions accordingly [ 47 ]. The brand image helps understand and accept the brand’s meaning through consumer perception [ 49 ], which is a collective result of various marketing activities and consumer experience [ 50 ]. In contrast, brand awareness refers to consumers’ ability to recognise or remember a brand [ 50 ], which aids them in searching for products to be purchased faster [ 51 ]. This element typically includes four levels, namely: brand recognition, brand recall, top of the mind brand, and dominant brand [ 52 ].

2.1.3. Repurchase intention recognised as consumer response.

Consumer response makes up the final part of the SOR model [ 28 ], which can be divided into two situations: response and avoidance. Here, the response behavior depicts customer willingness to purchase a product and positive WOM, whereas the avoidance behavior denotes opposite or negative WOM and unwilling purchase [ 20 ]. These responses underpin the current work’s investigation on Repurchase intention, which is otherwise characterised as consumer repurchase intention. Achieving customer loyalty is typically known as the most significant objective of marketing activities as the element is attributed to satisfied customers and consistent sales [ 33 ]. Therefore, repurchase intention is the key to fostering the relationship between customers and brands, whereby some studies have pinpointed increased loyalty and its correlated effect on reduced marketing costs and increased sales [ 53 ]. A brand owner may find it highly necessary to adjust its marketing strategy to retain valuable consumers and increase repurchase intention [ 25 ].

2.2 Repurchase intention

Repurchase intention generally refers to customer judgement of a specific brand product [ 54 ]. Alternatively, brand loyalty describes customer recognition of a particular brand, chosen among many brands as bolstered by the willingness to buy and repurchase products or services [ 55 ]. Therefore, brand loyalty is perceived as the repurchase intention, thus directly reflecting consumer thoughts when choosing to repurchase a particular brand [ 54 ]. Furthermore, brand loyalty is commonly expressed as the consumer tendency to purchase or repurchase brand-related products [ 56 , 57 ]. However, the level of attractiveness shown by their alternatives may affect the relationship between recovery satisfaction and repurchase intentions [ 58 ]. Here, elements influencing consumer repurchase intentions vary, including the lenient return policy and perceived fairness of return experience on top of the common return issues [ 59 ]. Besides, loyal brand users have low price sensitivity to associated brand products, which are also introduced to their friends. Therefore, these positive sharing behaviours allow many potential customers to the brand, increasing initial and second purchase intention [ 60 ].

2.3. Social media marketing activities and brand awareness

2.3.1 entertainment and brand awareness..

Entertainment generally refers to the fun aspect embedded in brand marketing content, which has been underlined by Kim and Ko [ 33 ] and Seo and Park [ 24 ] as an integral part of SMMA. Today, brand products are no longer tethered to traditional displays; instead, they are integrated with entertainment components to establish a stronger emotional connection with consumers [ 61 ]. Furthermore, it has been pinpointed as a factor that directly affects consumer attitudes towards brands [ 62 ], whereby Bilgin [ 63 ] has specifically detailed its significant effect on brand awareness and brand image. Accordingly, improving brand awareness is among the well-known corporate SMMA [ 33 , 64 ]. For example, Seo and Park [ 24 ] have pointed out that such activities performed by aviation and hotel businesses positively impact brand awareness and brand image. As such, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1a: Entertainment positively affects brand awareness among Chinese consumers .

H1b: Entertainment positively affects brand image among Chinese consumers .

2.3.2 Customization and brand equity.

Consumers typically believe that personalised brand recommendations align with their product preferences, and their more personalised needs to a higher degree [ 65 ]. In social media, customisation refers to the target audience of a message. Zhu and Chen [ 66 ] have thus identified the two types of publishing, depending on the level of message customisation: custom message and broadcast [ 56 ]. Here, customised information targets specific people or a small number of audiences (e.g., Facebook posts), whereas a broadcast generally contains messages directed at anyone interested in the content material (e.g., Twitter tweets). Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: Customisation positively affects brand awareness among Chinese consumers .

H2b: Customisation positively affects brand image among Chinese consumers .

2.3.3 Trendiness and brand equity.

Technology empowers firms to cultivate trends and enrich customer satisfaction and experience [ 67 ]. Trends are known for their significant impact on customer brand equity, especially in the context of young consumers [ 68 ]. Trendiness depicts the firms’ ability to foster and spread pertinent information that empowers their brand equity [ 8 ]. The adoption of social media to attract consumers has increased among SMEs [ 16 ]. In the luxury goods industry, fashion trends denote an essential element in SMMA and positively impact brand equity [ 60 ]. Kim and Lee [ 67 ] claimed that social media-based trendiness spurs brand awareness and brand image among the prospective consumers. Similarly, social media trends offer extensive awareness among users and help develop the brand image. Therefore, the following hypotheses are developed:

H3a: Trendiness positively affects brand awareness among Chinese consumers .

H3b: Trendiness positively affects brand image among Chinese consumers .

2.3.4 Interaction and brand equity.

Interaction mainly describes the dynamic communication between enterprises and consumers [ 35 ], and social media empowers both to interact facilitatively. Social media-based interaction simplifies the brand communication to the brand consumers and nurtures consumers’ brand experience and satisfaction [ 69 ]. Consumers and brands communicate and interact using various social media platforms [ 23 ]. Such platforms can be utilised to build consumer brand awareness and establish the right brand image concurrently [ 64 ]. Wang et al. [ 59 ] documented that social media-based interaction influences brand awareness and brand image building among young fashion retail consumers. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H4a: Interaction positively affects brand awareness among Chinese consumers .

H4b: Interaction positively affects brand image among Chinese consumers .

2.3.5 Word of mouth and brand equity.

In general, word of mouth refers to consumer perception regarding the degree to which other customers recommend and share the latter’s social media experiences [ 13 ]. Consumers like to share their positive or negative experiences on social media [ 67 ]. An industry survey has revealed that a whopping 91% of respondents would consider online reviews, ratings, etc., prior to any product purchases from e-commerce sites. In contrast, nearly 46% agree that such reviews influence their purchasing decisions [ 70 ]. Consumers’ comments on social media facilitate prospective consumers’ awareness and help build the brand image that later influences purchase intention [ 44 ]. Chahal, Wirtz, and Verma [ 71 ] claimed that online brand reputation directly affects perceived brand equity among consumers. Kim and Lee [ 67 ] suggested the positive influence of word of mouth on the levels of brand awareness and brand image among young Bangladeshi consumers. As such, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a: Word of mouth positively affects brand awareness among Chinese consumers .

H5b: Word of mouth positively affects brand image among Chinese consumers .

2.4 Brand equity and repurchase intention

Theoretically, brand equity is a subjective assessment of consumer brand preferences [ 10 ], whereby a brand rated as unique and appropriate by consumers indicates a high level of brand equity perceived for it [ 32 ]. Accordingly, a positive brand attitude can positively influence the customers’ repurchase intentions [ 55 ]. Zhang et al. [ 21 ] have postulated the positive link between brand equity and customer loyalty. In particular, brand equity based on brand awareness and brand image positively influence repurchase intention. For instance, brand awareness and brand image promote brand purchase and repurchase [ 10 ]. Thus, the following hypotheses are generated:

H6a: Brand awareness positively affects repurchase intention among Chinese consumers .

H6b: Brand image positively affects repurchase intention among Chinese consumers .

2.5 Mediating effect of brand equity

The impact of SMMA on brand equity has been confirmed in multiple previous studies in which the latter is considered the reason or motivation for purchasing certain brands. Therefore, higher brand equity can be correlated with higher robustness for consumer preference and willingness to buy any products [ 72 , 73 ]. Alternatively, brand awareness also affects consumer attitudes towards brands, further stimulating their brand choice [ 64 ]. In this matter, Keller [ 47 ] believes that regardless of the attributes being related to specific brand products or not, they vigorously promote the formation of brand associations, which will, in turn, directly affect consumer purchase or repurchase intentions. Therefore, brand loyalty is considered a necessary factor for ensuring repeat purchases [ 72 , 74 , 75 ]. Hence, the following hypothesis is generated:

Hypothesis (HM): Brand awareness and brand image mediate the relationship between entertainment , customisation , trendiness , interaction , and word of mouth on the repurchase intention among Chinese consumers .

3. Research methodology

3.1 research design.

The current study aimed to measure the impact of SMMA on brand awareness and brand image, thereby leading to the repurchase of high-tech products from a brand among Chinese consumers. The hypotheses and associations are thus designed and tested according to Fig 1 . The explanatory research design was implemented to depict the relationship between tested variables and determine its cause and impact [ 76 ]. Concurrently, quantitative methods were incorporated to study the relationship between variables, whereby the cross-sectional survey method was utilised for data collection purposes. Gathered from the target population, this allowed an exploration of the phenomenon being studied in work.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.g001

3.2 Sample selection and data collection method

The current study targeted the general population living in China who use social media platforms, namely WeChat, Tencent QQ, Sina Weibo, Youku Tudou, and Douyin, which are used by firms to promote their products. Therefore, the target population of this study included a total of 999.95 million social media users in China [ 77 ]. The sample size calculation was performed using G-Power 3.1 software. With power of 0.95, effect size of 0.15, and a total of seven predictors, the required sample size for the current study was 168 [ 78 ]. Moreover, the minimum sample of 200 is suggested for PLS-SEM [ 79 ]. The study aimed to employ the second-generation statistical analysis technique of structural equation modelling; therefore, the study collected data from more than 400 respondents. As the study was conducted during the COVID-19 lockdown, online survey was opted to protect the respondents and surveyors from COVID-19. The survey was conducted online ( http://www.wjx.cn/ ) from May 2020 to June 2020.

Local ethics committees (Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Malaysia) ruled that no formal ethics approval was required in this particular case based on the following reasons: (1) this study did not collect any medical information; (2) there was no known risk involved; (3) this study did not intend to publish any personal information; (4) this study did not collect data from underaged respondents. Moreover, this study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all survey respondents. The respondents were required to read and provide their agreement to the following ethical statement posted at the start of the survey before they were allowed to proceed to answering the survey questions: “ There is no compensation for responding nor is there any known risk . In order to ensure that all information will remain confidential , please do not include your name . Participation is strictly voluntary and you may refuse to participate at any time ”. No data was collected from anyone under 18 years old.

3.3 Survey instrument

The questionnaire consisted of two parts, namely Parts A and B. First, Part A included question items about the population profile, gender, age, monthly income, and education level. Meanwhile, Part B comprised question items about SMMA, brand equity, and consumer loyalty. In total, 34 measurement items were employed to estimate SMMA, brand awareness, brand image, and repurchase intention. The measurements were subsequently evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). A list of the question items and sources for implemented scales is detailed in Table 1 accordingly.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t001

3.4 Preliminary data preparation and multivariate normality

The outlier analysis with the Mahalanobis distance (D2) measure was conducted to estimate multivariate outliers [ 79 ]. Multiple regression analysis engaged all input variables on the outcome construct and saved the Mahalanobis distance for all cases. Cases with D2 of more than 26.125 were declared outliers; as a result, 35 cases were dropped. The subsequent analysis was performed with only 477 valid cases. Peng and Lai [ 84 ] have cautioned against making general statements about the partial least squares (PLS) estimation model capability as the action may violate the typical multivariate assumption despite the model not requiring a multivariate normal data distribution. Therefore, this study employed the Smart-PLS online tool to test the multivariate normality. The calculations carried out revealed p-values less than 0.5 for the multivariate skewness and kurtosis for Mardias’ coefficient. These outcomes successfully confirmed the non-normality of the data.

3.5 Common Method Bias (CMB)

As suggested by Podsakoff, Mackenize, and Podsakoff [ 85 ], CMB was evaluated based on the results of Harman single factor analysis, which served as a diagnostic tool in this study. The obtained results suggested that a single factor accounted for 35.19%, which was less than the prescribed limit of 50%. In other words, CMB was not a critical issue for the current study [ 85 ]. Moreover, Kock [ 86 ] recommended performing a full collinearity test to gauge the CMB issue. A common variable formed, and all the variables regressed on the common variable as an outcome variable. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for entertainment (1.685), customisation (2.063), Interaction (3.451), trendiness (2.948), word of mouth (2.202), brand awareness (3.433), brand image (2.277), and repurchase intention (2.781) did not exceed 5. This reaffirmed that CMB was not a severe issue for the current study [ 86 ]. The correlations matrix of the latent variables also showed that CMB was not an issue, as all correlations did not exceed 0.900 [ 85 ].

3.6 Data analysis method

Partial Least Squares—Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) is driven by maximising the interpretation variance of related latent structures [ 79 ]. It was implemented in this study to explore the impact of SMMA on Chinese consumer repurchase intentions in the presence of non-normality issues. Artificial neural network (ANN) analysis is a non-compensatory analytical technique with deep learning algorithms based on three layers: input, output, and hidden layers. The hidden layer connects the input neurons with the output neurons [ 87 ], acting as the block-box similar to the human brain [ 88 ]. The data are divided into three parts for training, testing, and holding out part of the sample. The study utilized the Root Mean Square Errors (RMSE) value of trained and tested data to identify the predictive accuracy [ 89 , 90 ].

4. Data analysis

4.1 demographic characteristics of respondents.

As presented in Table 2 , the majority of the respondents in this study were female (59.7%), while the remaining 40.3% were men. The respondents were grouped into the following age groups: (1) 18–26 years (46.3%); (2) 27–34 years (22.8%); (3) 35–42 years (13.8%); (4) 43 years and above (16.9%). Furthermore, 34.5% of the total respondents recorded monthly income of less than 3,000 yuan, followed by those with monthly income of between 3,001 and 6,000 yuan (30.6%), monthly income of between 6,001 and 9,000 yuan (15.3%), and lastly, monthly income of more than 9,000 yuan (19.4%). Among 477 respondents, only 16.4% consisted of high school students. The majority of the respondents (63.3%) were undergraduates, followed by graduate students (20.5%). In terms of the usage of electronic gadgets, the majority of the respondents (43.1%) used zero to two types, followed by those who used three to five types (33.9%). About 22.8% of the total respondents reported using more than six types. It should be noted that this study was not limited to any specific product brand or category, but rather a general assessment of high-tech products collectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t002

4.2 Reliability and validity

Reliability refers to the consistency shown by the measurement items according to the results obtained via the measurement tools implemented, thereby objectively reflecting the reasonable degree of the measured characteristics. In contrast, validity denotes their effectiveness by measuring whether the comprehensive evaluation system can accurately reflect the evaluation purposes and requirements. Thus, it echoes the measurement of feature accuracy in measuring by using the measuring tool.

Table 3 details the descriptive statistics, validly, and reliability criteria employed to evaluate the items used in the study. However, in reliability analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha (CA) coefficient size was assessed in measuring the questionnaire reliability. In general, a coefficient larger than 0.9 indicates excellent reliability, while a coefficient above 0.8 is good. Meanwhile, values between 0.5 and 0.9 reflect a reasonable outcome, whereas coefficients lower than 0.5 render the outcomes non-trustworthy. Accordingly, CA values shown in Table 3 reveal that all variables generated values greater than 0.8, indicating the latent constructs’ reliabilities.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t003

Moreover, Dillon Goldstein rho (DG rho) values more than 0.80 as seen for all variables, further confirming the measurement item reliability. We also utilized the composite reliability (CR), and the CR score for all the study constructs are well above 0.85, showing satisfactory reliabilities. Table 3 depicts the acceptable convergent validity attained by the constructs due to values higher than 0.50. According to the recommendation, convergent validity was obtained if the average variance extracted (AVE) value is higher than 0.50. Finally, testing for multicollinearity issues was performed by assessing the variance inflation factors (VIF). The VIF value of each factor is less than 5, suggesting that no major collinearity problem was present. From the reliability and validity testing undertaken, the Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each factor were relatively good, indicating relatively good data validity.

4.3 Discriminant validity

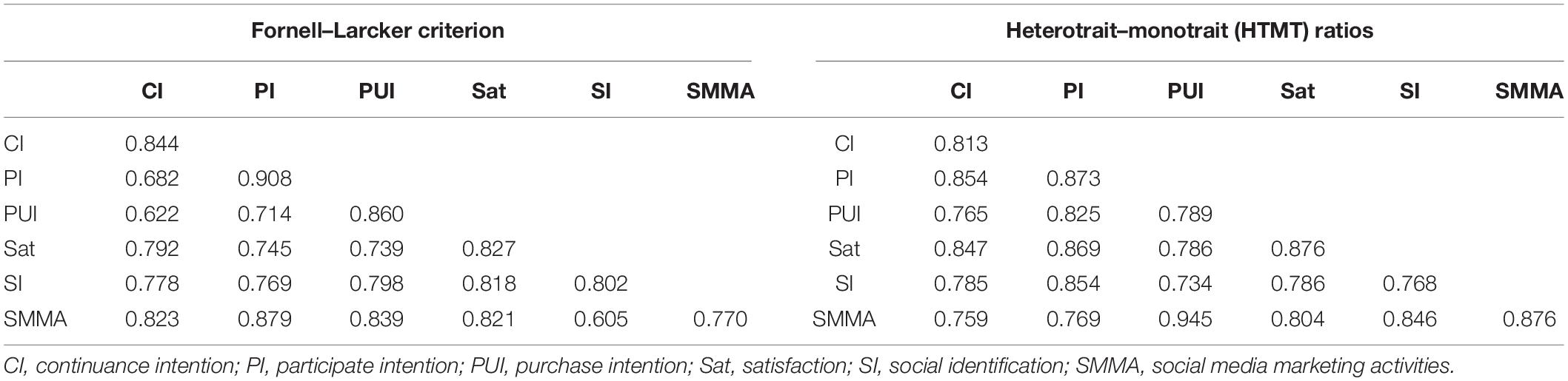

For the current study, Fornell-Larcker criterion, heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, as well as loadings and cross-loadings were used for the evaluation of discriminant validity. As for the estimation of Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of AVE of the construct must be greater than the corresponding correlation coefficient in order to establish discriminant validity. The obtained results in Table 4 showed that the study’s constructs showed suitable discriminant validity. Following that, the HTMT ratio served as a tool to estimate discriminant validity [ 91 ]. As shown in Table 4 , all HTMT ratios did not exceed the threshold value of 0.900, which showed that the study’s latent construct achieved suitable discriminant validity [ 79 ]. This study further verified discriminant validity via a comparison between the loadings and cross-loadings of the tested constructs. Generally, loading is the contribution of an item to the latent variable to which it belongs [ 79 ], whereas cross-loading is the contribution of an item to other latent variables. The loading of an item that exceeds its cross-loadings indicates that the item contributes more to the latent variable to which it belongs. For the current study, discriminative validity was deemed good. Table 5 shows all loadings and cross-loadings generated, whereby almost all loadings in the current study exceeded 0.7. Besides that, the loadings of all items on their respective corresponding latent variables exceeded their cross-loadings, substantiating the goodness of the questionnaire design and data validity.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t005

4.4 Path analysis

Table 6 presents the results of path analysis. The recorded path coefficient for the influence of entertainment on brand awareness ( β = 0.042, p = 0.114) indicated the insignificant but positive influence of entertainment on brand awareness. Thus, H1a was not supported. Meanwhile, the path coefficient for the influence of customisation on brand awareness ( β = -0.033, p = 0.163) revealed that it did not affect brand awareness. Thus, H2a was not statistically supported. Similarly, the path coefficient for the influence of trendiness on brand awareness ( β = 0.390, p = <0.001) displayed its significant effect on brand awareness; thus, offering support to accept H3a. In contrast, the path coefficient for the influence of interactions on brand awareness ( β = 0.188, p < 0.001) indicated its significant and positive influence on brand awareness, which supported H4a. As for the influence of word of mouth on brand awareness, the recorded path coefficient ( β = 0.109, p < 0.001) denoted its significant influence on brand awareness. Thus, H5a was supported.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t006

Meanwhile, the recorded path coefficient for the influence of entertainment on brand image ( β = -0.014, p = 0.379) indicated its non-effect on brand image, rendering the rejection of H1b. Similarly, the recorded path coefficient for the influence of customisation on brand image ( β = 0.093, p = 021) revealed its influence on brand image. Thus, H2b was accepted. In contrast, the recorded path coefficient for the influence of trendiness on brand image ( β = 0.312, p < 0.001) showed its significant and positive influence on brand image. Thus, H3b was accepted. Likewise, the recorded path coefficient for the influence of interaction on brand image ( β = 0.389, p < 0.001) revealed its significant and positive impact, rendering the acceptance of H4b. Additionally, the recorded path coefficient for the influence of word of mouth on brand image ( β = 0.179, p < 0.001) revealed its significant and positive influence. Thus, H5b was supported.

In this study, both H6a and H6b were also accepted. The recorded path coefficients for the effects of brand awareness ( β = 0.544, p < 0.001) and brand image ( β = 0.255, p < 0.001) on repurchase intention indicated their respective significant and positive effects.

4.5 Mediation effects

As shown in Table 7 , this study employed indirect effect coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values to measure the mediation effects of brand equity in terms of brand awareness and brand image on SMMAs (in terms of entertainment, customisation, trendiness, interaction, and word of mouth) and repurchase intention. The obtained results revealed that brand awareness ( β = 0.023, CI min = -0.011, CI max = 0.059, p > 0.05) insignificantly mediated the relationship between entertainment and repurchase intention. Similarly, brand awareness was found to insignificantly mediate the relationship between customisation and repurchase intention ( β = -0.018, CI min = -0.048, CI max = 0.013, p > 0.05). On the other hand, brand awareness mediated the effects of trendiness ( β = 0.212, CI min = 0.159, CI max = 0.267, p < 0.001), interaction ( β = 0.212, CI min = 0.157, CI max = 0.266, p < 0.001), and word of mouth ( β = 0.059, CI min = 0.023, CI max = 0.101, p < 0.001) on repurchase intention.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t007

The obtained results of the analysis further revealed that brand image ( β = -0.004, CI min = -0.022, CI max = 0.016, p > 0.05) insignificantly mediated the relationship between entertainment and repurchase intention. Besides that, brand image was found to mediate the effects of customisation ( β = 0.024, CI min = 0.005, CI max = 0.047, p < 0.05), trendiness ( β = 0.080, CI min = 0.045, CI max = 0.120, p < 0.001), interaction ( β = 0.048, CI min = 0.017, CI max = 0.085, p < 0.01), and word of mouth ( β = 0.046, CI min = 0.021, CI max = 0.077, p < 0.01) on repurchase intention.

4.6. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) analysis

Three ANN models were employed in this study to evaluate the data. Model A consisted of five input constructs for brand awareness. Model B had five exogenous variables, and brand image served as the outcome variable. Lastly, Model C had brand awareness and image as input for repurchase intention. Table 8 depicts the results of ANN analysis. Overall, Model A, Model B, and Model C demonstrated high prediction accuracy, as both RMSE training and RMSE scores for testing were rather similar [ 90 ]. Apart from that, the results showed that all ANN models had good data fitting. The goodness of fit for Model A was 59%, while Model B recorded 62%. Model C recorded the highest goodness of fit at 68%.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t008

Sensitivity analysis was performed on all three ANN models to evaluate the contribution of each exogenous predictor for the endogenous constructs [ 89 ]. The results in Table 9 for Model A confirmed trendiness, word of mouth, and interaction as the most influential three factors that affect brand awareness. As for Model B, trendiness, interaction, and word of mouth were identified as three critical factors that meaningfully instigate brand image. For repurchase intention, brand awareness was the most significant factor, followed by brand image for high-tech products among Chinese consumers.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t009

The PLS-SEM results were compared with the outcomes of these ANN models. The results are tabulated in Table 10 . The comparison depicts that the ranking of factors varies for Model A and Model B. However, the ranking of factors appeared the same for Model C.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.t010

5. Discussion

This study provided evidence about the impact of SMMA on the repurchase intention held by Chinese high-tech consumers. The assessment was carried out on the five dimensions of SMMA (i.e., entertainment, customisation, trends, interaction, and WOM), two dimensions of brand equity (i.e., brand awareness and brand image), and one dimension of brand loyalty (i.e., repurchase intention). The research conclusively revealed the positive impact by entertainment and WOM on brand awareness in carrying out social media activities. This aligns with the outcomes of Seo and Park’s [ 24 ] study, which has indicated that social media marketing activities harness brand equity, creating brand awareness. Meanwhile, trendiness, interaction, and WOM positively impacted brand image, paralleling the results by Yadav and Rehman [ 25 ]. Therefore, WOM was explicitly associated with a significantly positive impact on brand awareness and image. Similarly, the work verified the hypothesis that brand awareness and brand image significantly impact customer loyalty. Thus, the current research fully supported and confirmed the SOR model.

Furthermore, the mediation effect obtained in this study depicted a satisfactory mediating effect between brand awareness and the factors of entertainment, WOM, and repurchase intention. Therefore, brand equity could be attributed as responsible for the relationship between the three factors. Besides, it yielded a sufficient mediating effect between trendiness, interaction, WOM, and repurchase intention, its weight for the relationship between brand image and all four factors. In contrast, brand image and brand awareness generated no mediating effect between customisation and repurchase intention.

5.1. Theoretical and practical implications

Social media marketing activities nurture and change consumer behaviour, which predictively influence their purchase and repurchase intention. The current study offered theoretical and practical implications. Most previous studies investigated the direct effects of social media marketing activities on purchase intention, but the current study successfully advanced the current literature by examining the mediating role of brand awareness and brand image in relation to repurchase intention of the brand offerings. The study’s findings would undoubtedly add value to the growing literature on social media marketing, brand equity, and repurchase intention. The current study utilised the SOR framework to justify the effects of social media marketing activities on brand awareness and brand image in relation to repurchase intention. Social media marketing activities have become powerful marketing strategies to meet consumers’ expectations and inclination to repurchase firms’ brand offerings. These marketing strategies are relevant to attract new consumers and significantly empower firms to manage customer relationships in order to retain the existing consumers.

The current study also offered three practical implications. Firstly, the study’s findings address firms’ management needs of developing and improving entertainment and customisation attributes in their social media marketing that can advance their efforts to harness brand equity, nurturing repurchase intention among technology product consumers [ 16 ]. Secondly, the current study emphasised repurchase intention as the function of customer loyalty. Social media marketing activities can significantly harness consumer-level of brand equity through brand awareness and brand image. All types of firms need to consider investing and building brand equity with the help of social media marketing activities. Currently, firms only concentrate on trendiness and the need to build social media marketing activities through entertainment, Interaction, customisation, and word of mouth. Lastly, the results of the current study confirmed the effects of social media marketing activities on brand awareness and brand image in relation to repurchase intention. Firms need to concentrate on building brand awareness and brand image with social media marketing activities. Consumers’ inclination to repurchase would develop with the right social media marketing activities, and marketers must harness brand-level equities to promote repurchase intention.

6. Limitation

However, this study has several limitations requiring further attention. For example, the components included in the current research model did not exhaustively list the explanatory variables possibly affecting SMMA. Moreover, the current research mainly focused on high-tech Chinese consumers, limiting the outcome generalisability across the market. Therefore, future works should look into designing research embedded with more variables to explore different social media’s effects on brand equity and brand loyalty across different brand-consumer segments. Besides, using the SOR-based model in this study might limit the research results. Thus, future researchers recommend confirming, replicating, or expanding the outcomes by integrating additional model constructs or using it across dissimilar cultural or geographic environments. This would deepen the scholarly understanding of customers’ repurchase intentions with more depth.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264899.s001

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 12. Xiao, Y., Wang, L., & Wang, P. (2019). Research on the influence of content features of short video marketing on consumer purchase intentions. Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology and Social Science (MMETSS 2019) . https://doi.org/10.2991/mmetss-19.2019.82

- 76. Saunders M., Lewis P., & Thornhill A. (2016). Research Methods for Business. Pearson Education Limited. Harlow, United Kingdom.

- 77. Statista (2021), Number of social network users in China from 2017 to 2020 with a forecast until 2026 , Available from: accessed from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/277586/number-of-social-network-users-in-china/

- 89. Hayat N.; Al-Mamun A.; Nasir N., A.; Nawi N., B., C. (2021), Predicting accuracy comparison between structural equation modelling and neural network approach: A case of intention to adopt conservative agriculture. In Alarneeni et al. (Eds.): Importance of new technologies and entrepreneurship in the business context: The context of economic diversity in developing countries: The impact of new technologies and entrepreneurship on business development. Springer Nature International Publishing, pp. 1958–1971. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69221-6_141

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Role of social media marketing activities in influencing customer intentions: a perspective of a new emerging era.

- 1 School of Economics and Management, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China

- 2 Department of Management Sciences and Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China

- 3 Faisalabad Business School, National Textile University, Faisalabad, Pakistan

The aim of this study is to explore social media marketing activities (SMMAs) and their impact on consumer intentions (continuance, participate, and purchase). This study also analyzes the mediating roles of social identification and satisfaction. The participants in this study were experienced users of two social media platforms Facebook and Instagram in Pakistan. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from respondents. We used an online community to invite Facebook and Instagram users to complete the questionnaire in the designated online questionnaire system. Data were collected from 353 respondents, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the data. Results show that SMMAs have a significant impact on the intentions of users. Furthermore, social identification mediates the relationship between social media activities and satisfaction, and satisfaction mediates the relationship between social media activities and the intentions of users. This will help marketers how to attract customers to develop their intentions. This is the first novel study that used SMMAs to address the user intentions with the role of social identification and satisfaction in the context of Pakistan.

Introduction

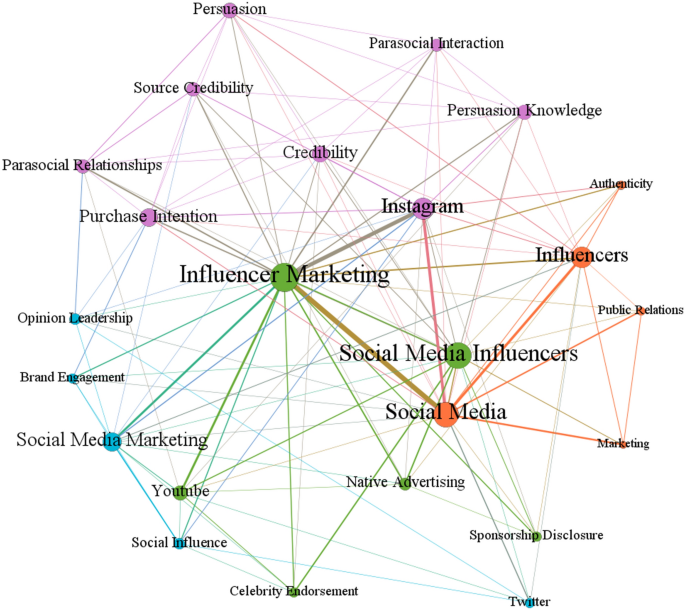

There has been tremendous growth in the use of social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook over the past decade ( Chen and Qasim, 2021 ). People are using these platforms to communicate with one another, and popular brands use them to market their products. Social activities have been brought from the real world to the virtual world courtesy of social networking sites. Messages are sent in real time which now enable people to interact and share information. As a result, companies consider social media platforms as vital tools for succeeding in the online marketplace ( Ebrahim, 2020 ). The use of social media to commercially promote processes or events to attract potential consumers online is referred to as social media marketing (SMM). With the immense rise in community websites, a lot of organizations have started to find the best ways to utilize these sites in creating strong relationships and communications with users to enable friendly and close relationships to create online brand communities ( Ibrahim and Aljarah, 2018 ).

Social media marketing efficiently fosters communications between customers and marketers, besides enabling activities that enhance brand awareness ( Hafez, 2021 ). For that reason, SMM remains to be considered as a new marketing strategy, but how it impacts intentions is limited. But, to date, a lot of research on SMM is focused on consumer’s behavior, creative strategies, content analysis and the benefits of user-generated content, and their relevance to creating virtual brand communities ( Ibrahim, 2021 ).

New channels of communication have been created, and there have been tremendous changes in how people interact because of the internet developing various applications and tools over time ( Tarsakoo and Charoensukmongkol, 2020 ). Companies now appreciate that sharing brand information and consumer’s experience is a new avenue for brand marketing due to the widespread use of smartphones and the internet, with most people now relying on social media brands. Therefore, developing online communities has become very efficient. Social groups create a sense of continuity for their members without meeting physically ( Yadav and Rahman, 2017 ). A community that acquires products from a certain brand is referred to as a virtual brand community. Customers are not just interested in buying goods and services but also in creating worthwhile experiences and strong relationships with other customers and professionals. So, when customers are part of online communities, there is a cohesion that grows among the customers, which impacts the market. Therefore, it is up to the companies to identify methods or factors that will encourage customers to take part in these communities ( Ismail et al., 2018 ).

The online community’s nature is like that of actual communities when it comes to creating shared experiences, enabling social support, and attending to the members’ need to identify themselves, regardless of the similarities and variances existing between real-world communities and online communities ( Seo and Park, 2018 ). Regarding manifestations and technology, online communities are distinct from real-life communities since the former primarily use computers to facilitate their operation. A certain brand product or service is used to set up a brand community. Brand communities refer to certain communities founded based on interactions that are not limited by geographical restrictions between brand consumers ( Chen and Lin, 2019 ). Since consumers’ social relationships create brand communities, these communities have customs, traditions, rituals, and community awareness. The group members learn from each other and share knowledge about a product, hence appreciating each other’s actions and ideas. So, once a consumer joins a particular brand community, automatically, the brand becomes a conduit and common language linking the community members together because of sharing brand experiences ( Arora and Sanni, 2019 ).

Based on the perspective of brand owners, most research has focused on how social communities can benefit brands. However, there are also some discussions regarding the benefits that come from brand community members according to the members themselves to analyze how social community impacts its members ( Shareef et al., 2019 ). Consumer’s behavior is influenced by value so, when a consumer is constantly receiving value, it leads to consumer’s loyalty toward that brand. According to Alalwan et al. (2017) , a valuable service provider will create loyalty to a company and enhance brand awareness. Consumer value is essentially used in evaluating social networking sites. With better and easier options to create websites coming around, most consumers are attracted to a social community to know about a company and its goods. Furthermore, operators can learn consumer’s behavior through maintaining social interactions with customers. However, the social community should have great value. It should be beneficial to the potential customers by providing them with information relevant to the brand in question. Furthermore, customers should be able to interact with one another, thus creating a sense of belonging. From that, it is evident that a brand social community’s satisfaction affects community retention and selection.

Literature Review

Social media marketing activities.

Most businesses use online marketing strategies such as blogger endorsements, advertising on social media sites, and managing content generated by users to build brand awareness among consumers ( Wang and Kim, 2017 ). Social media is made up of internet-associated applications anchored on technological and ideological Web 2.0 principles, which enables the production and sharing of the content generated by users. Due to its interactive characteristics that enable knowledge sharing, collaborative, and participatory activities available to a larger community than in media formats such as radio, TV, and print, social media is considered the most vital communication channel for spreading brand information. Social media comprises blogs, internet forums, consumer’s review sites, social networking websites (Twitter, Blogger, LinkedIn, and Facebook), and Wikis ( Arrigo, 2018 ).

Social media facilitates content sharing, collaborations, and interactions. These social media platforms and applications exist in various forms such as social bookmarking, rating, video, pictures, podcasts, wikis, microblogging, social blogs, and weblogs. Social networkers, governmental organizations, and business firms are using social media to communicate, with its use increasing tremendously ( Cheung et al., 2021 ). Governmental organizations and business firms use social media for marketing and advertising. Integrated marketing activities can be performed with less cost and effort due to the seamless interactions and communication among consumer partners, events, media, digital services, and retailers via social media ( Tafesse and Wien, 2018 ).

According to Liu et al. (2021) , marketing campaigns for luxury brands consist of main factors such as customization, reputation, trendiness, interaction, and entertainment which significantly impact customers’ purchase intentions and brand equity. Activities that involve community marketing accrue from interactions between events and the mental states of individuals, whereas products are external factors for users ( Parsons and Lepkowska-White, 2018 ). But even though regardless of people experience similar service activities, there is a likelihood of having different ideas and feelings about an event; hence, outcomes for users and consumers are distinct. In future marketing, competition will focus more on brand marketing activities; hence, the marketing activities ought to offer sensory stimulation and themes that give customers a great experience. Now brands must provide quality features but also focus on enabling an impressive customer’s experience ( Beig and Khan, 2018 ).

Social Identification

A lot of studies about brand communities involve social identification, appreciating the fact that a member of a grand community is part and parcel of that community. Social identity demystifies how a person enhances self-affirmation and self-esteem using comparison, identity, and categorization ( Chen and Lin, 2019 ). There is no clear definition of the brand community or the brand owner, strengthening interactions between the community and its members or creating a rapport between the brand and community members. As a result, members of a community are separated into groups based on their educational attainment, occupation, and living environment. Members of social networks categorize each other into various groups or similar groups according to their classification in social networks ( Salem and Salem, 2021 ).

Brand identification and identification of brand communities emanate from a similar process. Users can interact freely, hence creating similar ideologies about the community, alongside strengthening bonds among members, hence enabling them to identify with that community. The brand community identity can also be considered as a convergence of values between the principles of the social community and the values of the users ( Wibowo et al., 2021 ).

According to Lee et al. (2021) , members of a brand social community share their ideas by taking part in community activities to help create solutions. When customers join a brand community, they happily take part in activities or discussions and are ready to help each other. So, it is evident that social community participation is impacting community identity positively. Community involvement entails a person sharing professional understanding or knowledge with other members to enhance personal growth and create a sense of belonging ( Gupta and Syed, 2021 ). According to Haobin Ye et al. (2021) , it is high time community identity be incorporated in virtual communities since it is a crucial factor that affects the operations of virtual communities. Also, community identity assists in facilitating positive interactions among members of the community, encouraging them to actively take part in community activities ( Assimakopoulos et al., 2017 ). This literature review suggests that social communities need members to work together. Individuals who can identify organizational visions and goals become dedicated to that virtual company.

Satisfaction

Customer’s satisfaction involves comparing expected and after-service satisfaction with the standards emanating from accumulated previous experiences. According to implementation confirmation theory, satisfaction is a consumer’s expected satisfaction with how the services have lived up to those expectations. Customers usually determine the level of satisfaction by comparing the satisfaction previously experienced and the current one ( Pang, 2021 ).

According to recent studies, community satisfaction impacts consumer’s loyalty and community participation. A study community’s level of satisfaction is determined by how its members rate it ( Jarman et al., 2021 ). Based on previous interactions, the community may be evaluated. When the members are satisfied with their communities, it is manifested through joyful emotions, which affect the behavior of community members. In short, satisfaction creates active participation and community loyalty ( Shujaat et al., 2021 ).

Types of Intentions

A lot of studies about information and marketing systems have used continuance intention in measuring if a customer continues to use a certain product or service. The willingness of customers to continue using a good or service determines if service providers will be successful or not. According to Zollo et al. (2020) , an efficient information marketing system should persuade users to use it, besides retaining previous users to guarantee continued use.

Operators of social networks must identify the reason propelling continued use of social network sites, alongside attracting more users. Nevertheless, previous studies on information systems in the last two decades have mainly concentrated on behavior–cognition approaches, for instance, the technology acceptance model (TAM), theory of planned behavior (TPB), and theory of reasoned action (TRA) with their variants ( Tarsakoo and Charoensukmongkol, 2020 ; Jamil et al., 2021b ). According to Ismail et al. (2018) , perceived use and satisfaction positively impact a user’s continuance intention. The continued community members’ participation has two intentions. Continuance intention is the first one. It defines the community member’s intent to keep on using the community ( Beig and Khan, 2018 ; Dunnan et al., 2020 ). Then, recommendation intention, also known as mouth marketing, describes every informal communication that takes place among community members regarding the virtual brand community. Previous studies about members of a virtual community mostly entailed the continuous utilization of information systems ( Seo and Park, 2018 ; Sarfraz et al., 2021 ). Unlike previous studies, this study focuses on factors that support the continued participation of community members. So, besides determining how usage purpose affects continuance intention, the study also investigated the factors that influence users’ willingness to take part in community activities ( Gul et al., 2021 ).

Nevertheless, it is hard to determine and monitor whether a certain action occurred (recommendation or purchase) during empirical investigations. Consumers will seek relevant information associated with their external environment and experiences when purchasing goods ( Shareef et al., 2019 ). Once they have collected significant information, they will evaluate it, and draw comparisons from which customer’s behavior is determined. Since purchase intention refers to a customer’s affinity toward a particular product, it is a metric of a customer’s behavioral intention. According to Liu et al. (2021) , the probability of a customer buying a particular product is known as an intention to buy. So, when the probability is high, it simply means that the willingness to purchase is high. Past studies consider purchase intention as a factor that can predict consumer’s behavior alongside the subjective possibility of consumer’s purchases. According to Chen and Qasim (2021) , from a marketing viewpoint, if a company wants to retain its community besides achieving community targets while establishing successful marketing via the community, at least three objectives are needed. They include membership continuance intention, which entails members living up to their promises in the community and also the willingness to belong to the community ( Yadav and Rahman, 2018 ; Naseem et al., 2020 ). On the other side, community recommendation intention entails the willingness of members to recommend or refer community members to other people who are not members ( Jamil et al., 2021a ; Mohsin et al., 2021 ). The next consideration is the community participation intention of a member, which involves their willingness to participate in the activities of the brand community. Unlike past literature about using information systems, this study demystified how SMMAs influence purchase intention and participation intention ( Alalwan et al., 2017 ).

Development of Hypotheses

People with similar interests can get a virtual platform to discuss and share ideas courtesy of social media. Sustained communication of social media allows users to create a community. Long-lasting sharing of growth and information fosters the development of strong social relationships. The information posted on social media platforms by an individual positively correlates with the followers the user has. Regarding the discussion above, we proposed the following hypothesis:

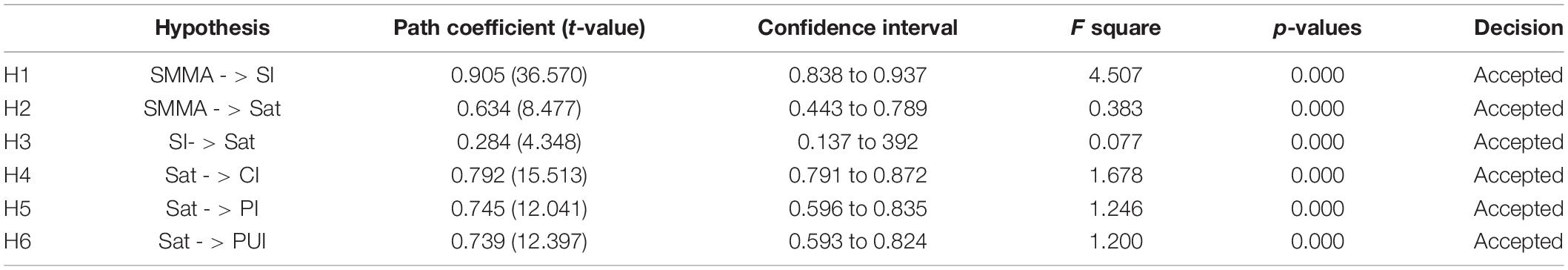

H1: Social media marketing activities (SMMAs) have a significant impact on social identification.

The study of Farivar and Richardson (2021) on users’ continuance intention confirmed that it is influenced by satisfaction after service. Social media studies are also of the thought that satisfaction significantly affects continuance intention. So, a consumer will measure the satisfaction of service after using it. Mahendra (2021) claims that satisfaction influences repurchase behavior. Repurchase intention emanates from a customer’s satisfaction with a good or service. People who have similar interests may interact and cooperate in a virtual world via social media platforms. A community on social media may be formed by regularly connecting with people and exchanging information with them. Members benefit from long-term information and growth exchanges that enable them to create strong social relationships. A lot of studies have pointed out that repurchase intention and customer’s satisfaction are positively and highly related. Besides, marketing studies noted that satisfactory experience after using a product would impact the intention of future repurchase. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H2: SMMAs have a significant impact on satisfaction.

The study by Suman et al. (2021) on American consumer’s behavior suggested that members taking part in community activities (meetups, discussion, and browsing) influence their brand-associated behavior. According to Di Minin et al. (2021) , the brand identity of a consumer has a positive impact on satisfaction. Consumers capitalize on online communities to share their experiences and thoughts about a grand regularly and easily ( Sirola et al., 2021 ). These experiences make up the customer to brand experiences and establish a sense of belonging, trust, and group identity. In a nutshell, this study suggests that identity will enable members to recognize their community, hence confirming that members have similar experiences and feelings with a particular brand and feel united in the group ( Shujaat et al., 2021 ). Strong group identity means that members are integrated closely into the brand communities and highly regard the community. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Social identification has a significant impact on satisfaction.

Brand communities are beneficial in the sense that they enable sharing of marketing information, managing a community, and exploring demands ( Dutot, 2020 ). These activities are likely to enhance consumer’s rights and increase customer’s satisfaction ( Sahibzada et al., 2020 ). A customer who makes an online transaction will be highly satisfied with a website that provides a great experience ( Koçak et al., 2021 ). Enhancing customer’s satisfaction, encouraging customer intentions, creating community loyalty, and fostering communication and interactions between community users are crucial to lasting community platform management ( Pang, 2021 ). Hence, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H4: Satisfaction has a significant impact on continuance intention.

H5: Satisfaction has a significant impact on participate intention.

H6: Satisfaction has a significant impact on purchase intention.

Thaler (1985) proposed transaction utility theory, in which consumers’ willingness to spend money is influenced by their perceptions of value. Researchers such as Dodds (1991) claimed that buyers only become ready to purchase after they have established a sense of value for a product. According to Petrick et al. (2001) , a product’s quality is dependent on the customer’s satisfaction. Several studies have shown that enjoyment, perceived value, and behavioral intention are all linked together. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H7: Social identification mediates the relationship between SMMA and satisfaction.

When it comes to information systems, Bhattacherjee et al. (2008) discovered that people’s continual intention is derived from their satisfaction with the system after they have used it. Studies on employee’s satisfaction in the workplace have shown that it has a substantial influence on CI. The amount of satisfaction that users have with the system that they have previously used is the most important factor in determining their CI, according to research on information system utilization intention.

In other words, the customer’s contentment with the product leads to the establishment of a desire to buy the thing again, as mentioned by Assimakopoulos et al. (2017) . Numerous studies show a strong link between customer’s satisfaction and their propensity to return for another transaction. According to a lot of marketing studies, customers who have a pleasant experience with a product are more likely to repurchase it. Hence, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H8: Satisfaction mediates the relationship between social identification and continuance intention.

H9: Satisfaction mediates the relationship between social identification and participate intention.

H10: Satisfaction mediates the relationship between social identification and purchase intention.

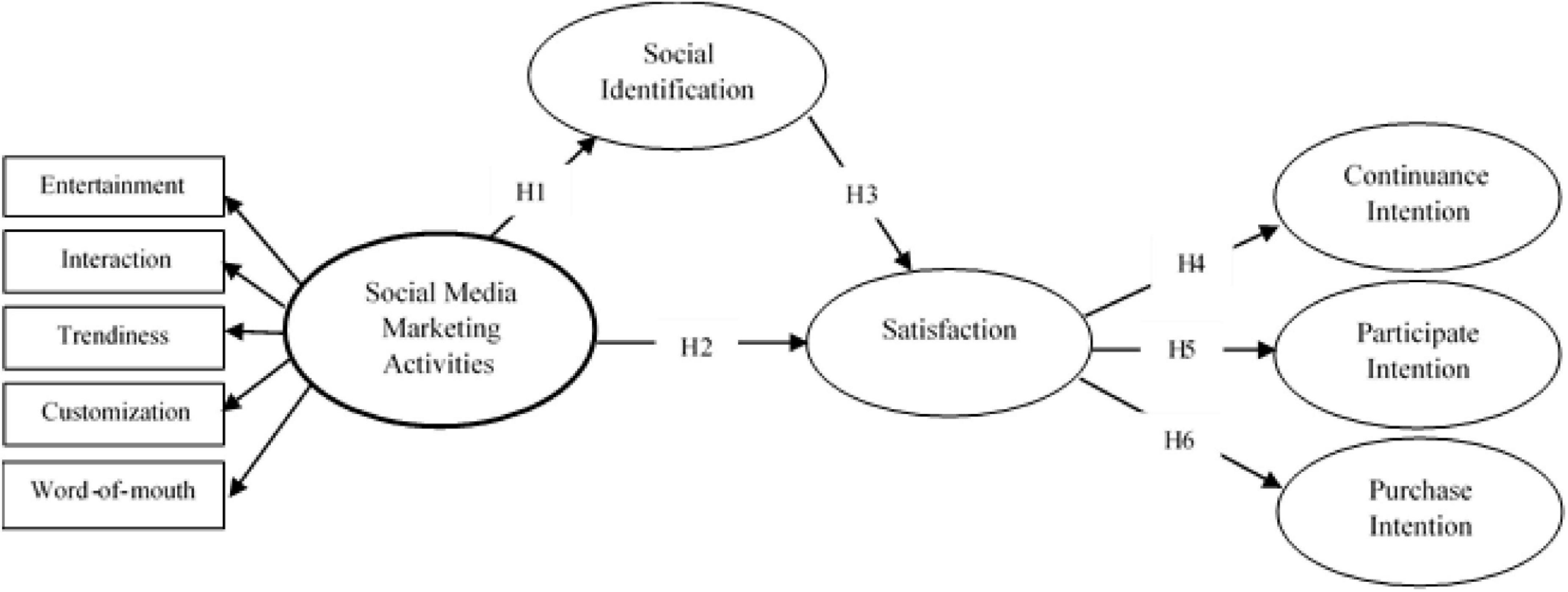

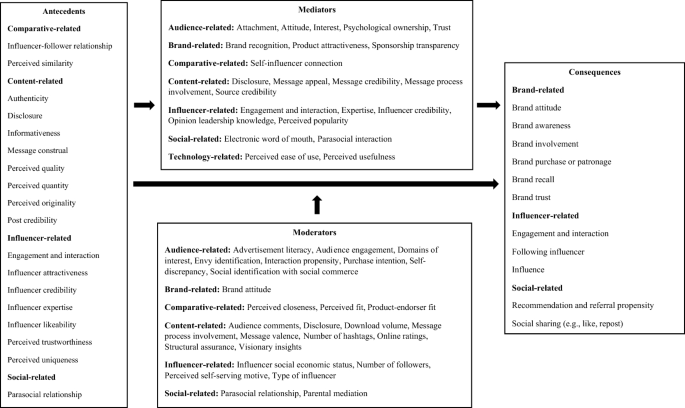

Figure 1 shows the research framework of this study.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

Conceptual Framework

Research methodology.

This study designed a questionnaire according to the hypotheses stated above. The participants in this study were experienced users of two social media platforms Facebook and Instagram in Pakistan. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from respondents. A pilot study with 40 participants was carried out. Since providing recommendations, revisions were made to the final questionnaire to make it more understandable for the study’s respondents. To ensure the content validity of the measures, three academic experts of marketing analyzed and make improvements in the items of constructs. The experts searched for spelling errors and grammatical errors and ensured that the items were correct. The experts have proposed minor text revisions to social identification and satisfaction items and advised that the original number of items is to be maintained. This study used an online community to invite Facebook and Instagram users to complete the questionnaire in the designated online questionnaire system. Online questionnaires have the following advantages ( Tan and Teo, 2000 ): (1) sampling is not restricted to a single geological location, (2) lower cost, and (3) faster questionnaire responses. A total of 353 questionnaires were returned from respondents. There were 353 appropriate replies considered for the final analysis.

The study used items established from prior research to confirm the reliability and validity of the measures. All items are evaluated through 5-point Likert-type scales where “1” (strongly disagree), “3” (neutral), and “5” (strongly agree).

Dependent Variable

To get a response about three dimensions of intention (continuance, participate, and purchase), we used eight items adopted from prior studies;

1. Continuance intention is measured by three items from the study of Bhattacherjee et al. (2008) , and the sample item is, “I intend to continue buying social media rather than discontinue its use.”

2. Participate intention is evaluated by three items from the work of Debatin et al. (2009) , and the sample item is, “my intentions are to continue participating in the social media activities.”

3. Purchase intention was determined by two items adapted from the work of Pavlou et al. (2007) , and the sample item is, “I intend to buy using social media in the near future.”

Independent Variable

To analyze the five dimensions of SMMAs, we used eleven items adopted from a prior study of Kim and Ko (2012) .

1. Entertainment is determined by two items and the sample item is, “using social media for shopping is fun.”

2. Interaction is evaluated by three items, and the sample item is, “conversation or opinion exchange with others is possible through brand pages on social media.”

3. Trendiness is measured by two items, and the sample item is, “contents shown in social media is the newest information.”

4. Customization is measured by two items, and the sample item is, “brand’s pages on social media offers customized information search.”

5. Word of mouth is measured by two items, and the sample item is, “I would like to pass along information on the brand, product, or services from social media to my friends.”

Mediating Variables

We used two mediating variables in this study,

1. Social identification was measured with five items adopted from the prior study of Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) , and the sample item is, “I see myself as a part of the social media community.”

2. Satisfaction was evaluated with six items adopted from the study of Chen et al. (2015) , and the sample item is, “overall, I am happy to purchase my desired product from social media.”

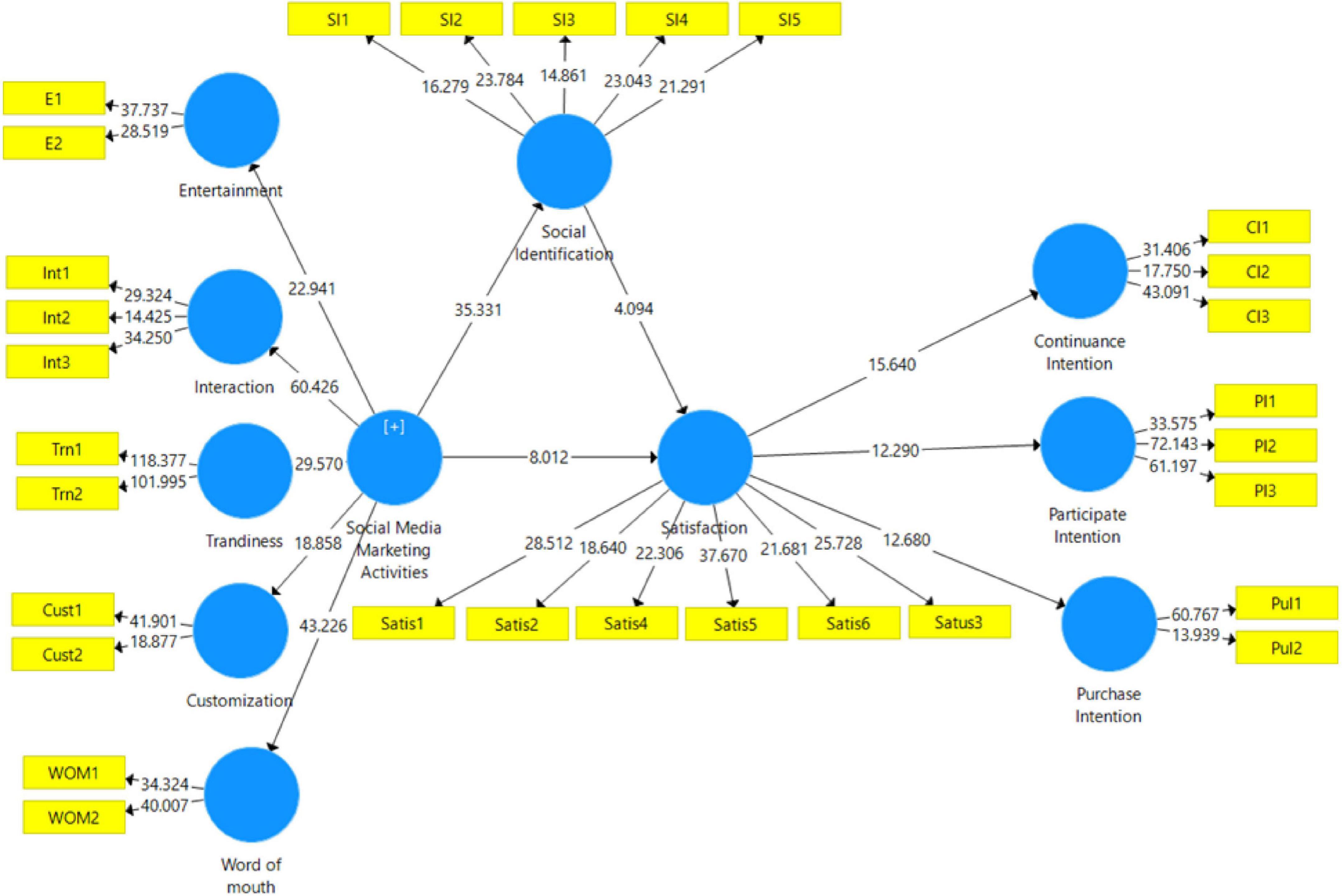

This research employs a partial least square (PLS) modeling technique, instead of other covariance-based approaches such as LISREL and AMOS. The reason behind why we pick PLS-SEM is that it is most suitable for confirmatory and also exploratory research ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). Structural equation modeling (SEM) has two approaches, namely covariance-based and PLS-SEM ( Hair et al., 2014 ). PLS is primarily used to validate hypotheses, whereas SEM is most advantageous in hypothesis expansion ( Podsakoff et al., 2012 ). A PLS-SEM-based methodology would be done in two phases, first weighing and then measurement ( Sarstedt et al., 2014 ). PLS-SEM is ideal for a multiple-order, multivariable model. To do small data analysis is equally useful in PLS-SEM ( Hair et al., 2014 ). PLS-SEM allows it easy to calculate all parameter calculations ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). The present analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 3.9.

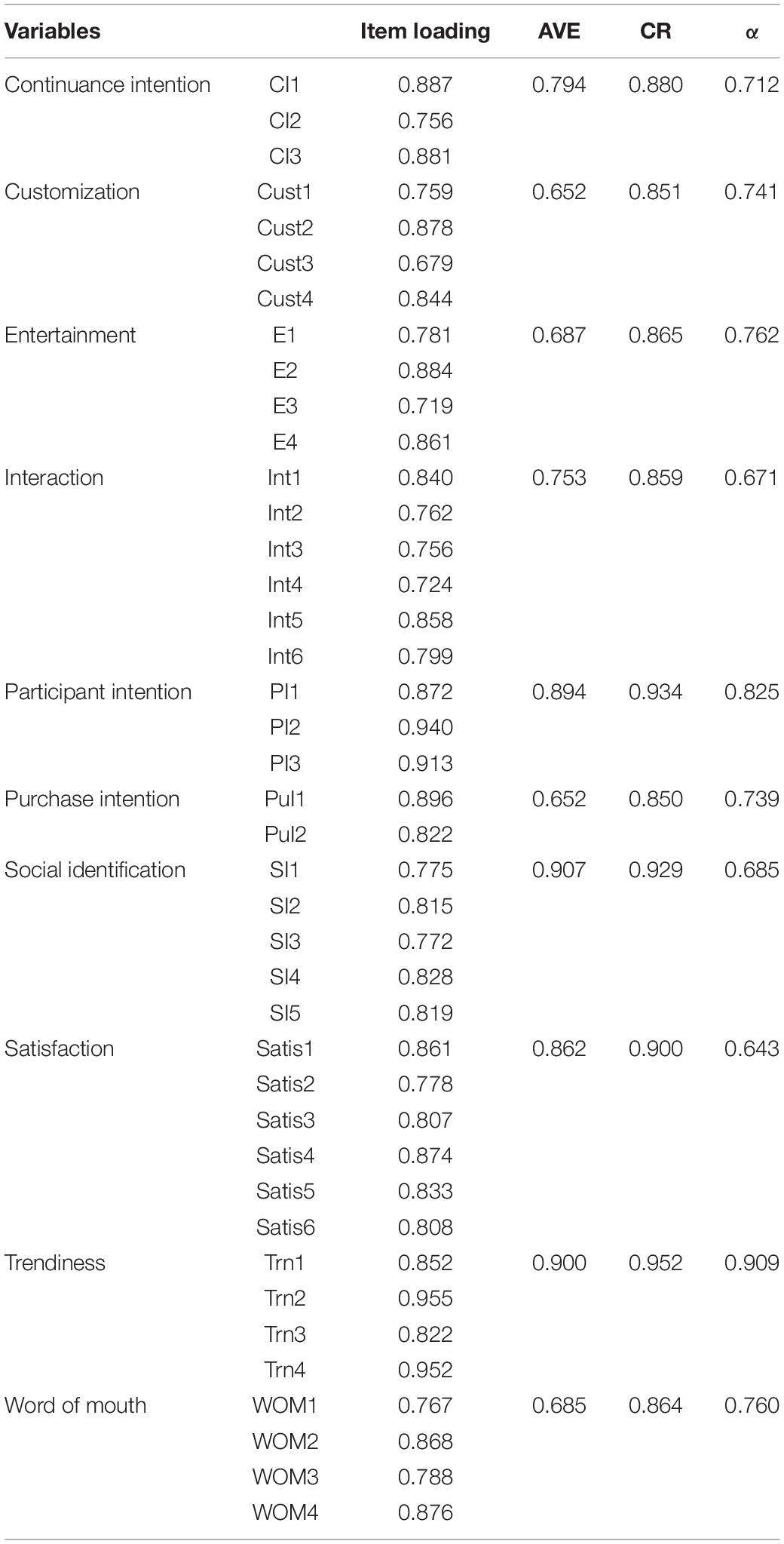

Model Measurement

Table 1 shows this study model based on 31 items of the seven variables. The reliability of this study model is measured with Cronbach’s alpha ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). As shown in Table 1 , all items’ reliability is robust, Cronbach’s alpha (α) is greater than 0.7. Moreover, composite reliability (CR) fluctuates from.80 to.854, which surpassed the prescribed limit of 0.70, affirming that all loadings used for this research have shown up to satisfactory indicator reliability. Ultimately, all item’s loadings are over the 0.6 cutoff, which meets the threshold ( Henseler et al., 2015 ).

Table 1. Inner model evaluation.

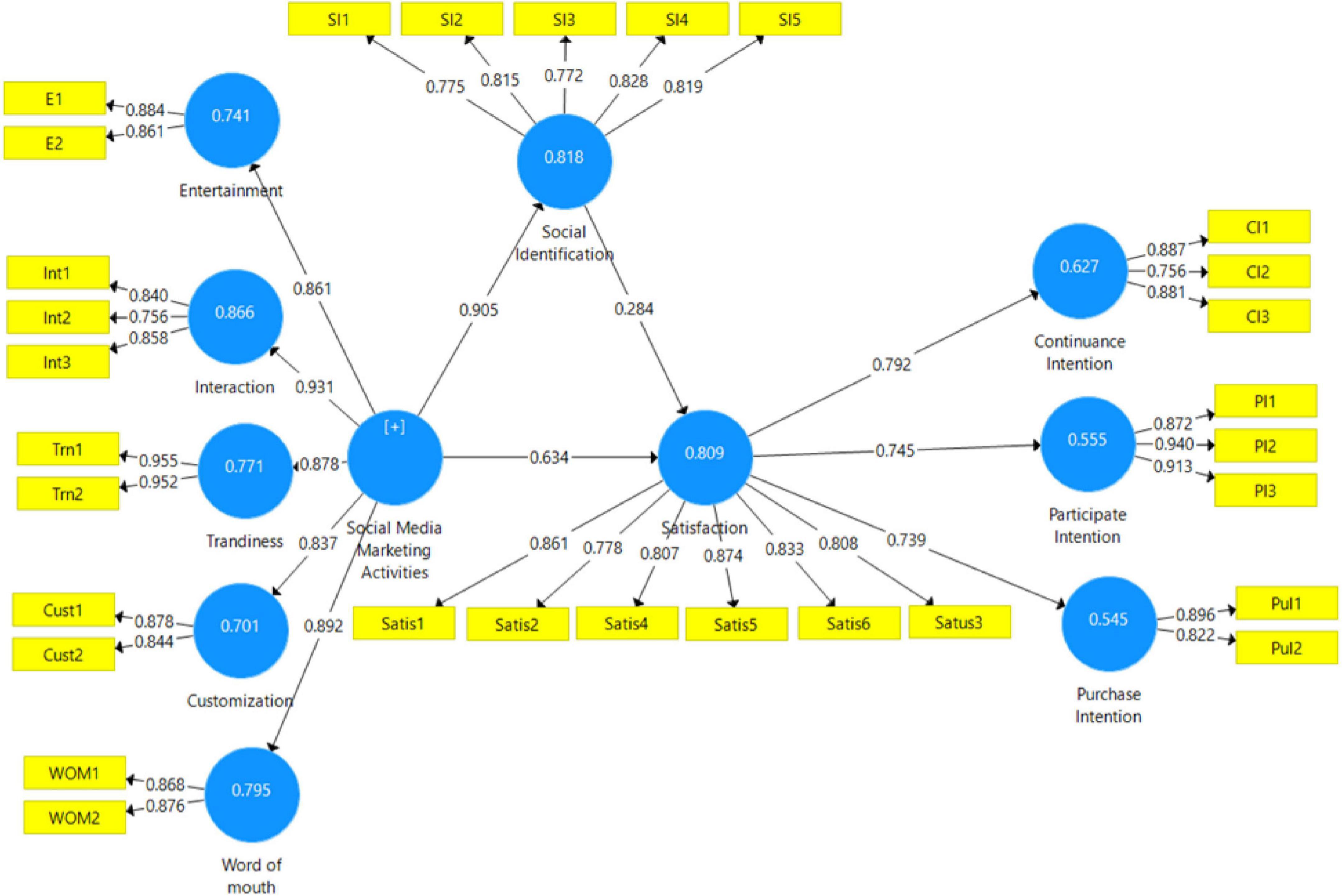

The Cronbach’s alpha value for all constructs must be greater than 0.70 is acceptable ( Hair et al., 2014 ). All the values of α are greater than 0.7 as shown in Table 1 and Figure 2 .

Figure 2. Measurement model.

Convergent validity is measured by CR and AVE, and scale reliability for each item ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). The scholar says that CR and AVE should be greater than 0.7 and 0.5, respectively. By utilizing CR and average variance extracted scores, convergent validity was estimated ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ). As elaborated in Table 3 , the average variance extracted scores of all the indicators are greater than 0.50 and CR is higher than.70 which is elaborating an acceptable threshold of convergent validity and internal consistency. It is stated that a value of CR, that is, not less than 0.70, is acceptable and evaluated as a good indicator of internal consistency ( Sarstedt et al., 2014 ). Moreover, average variance extracted scores of more than 0.50 demonstrate an acceptable convergent validity, as this implies that a specific construct with greater than 50% variations is clarified by the required indicators.

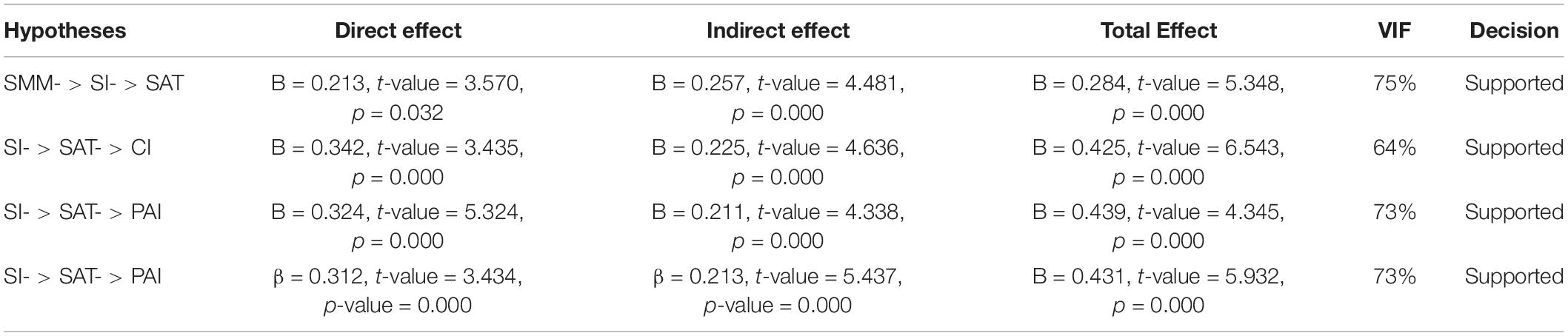

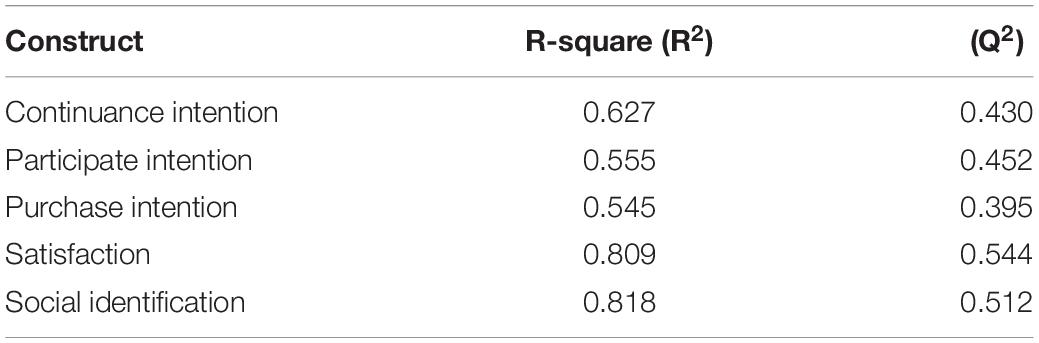

Table 2. A mediation analysis.

Table 3. Discriminant validity.

This study determines the discriminant validity through two techniques named Fornell–Larcker criterion and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). In line with Fornell and Larcker (1981) , the upper right-side diagonal values should be greater than the correlation with other variables, which is the square root of AVE, which indicates the discriminant validity of the model. Table 3 states that discriminant validity was developed top value of variable correlation with itself is highest. The HTMT ratios must be less than 0.85, although values in the range of 0.90 to 0.95 are appropriate ( Hair Joe et al., 2016 ). Table 3 displays that all HTMT ratios are less than 0.90, which reinforces the statement that discriminant validity was supported in this study’s classification.

To determine the problem of multicollinearity in the model, VIF was calculated for this purpose. The experts said that if the value of VIF is greater than 5, there is no collinearity issue in findings ( Hair et al., 2014 ). The results indicate that the inner value of VIF for all indicators must fall in the range of 1.421 to 1.893. Furthermore, these study findings show no issue of collinearity with data, and the study has stable results.